1. Introduction

Early diagnosis and treatment is crucial for the outcome of penile cancer [

1]. Penile cancer metastasizes mainly through the lymphatic system and several authors demonstrate that patients’ survival is determined by the inguinal lymph node status at the time of diagnosis [

2,

3]. The European Association of Urology (EAU) guidelines on penile cancer recommend a radical inguinal lymph node dissection in all patients with clinically positive lymph nodes (cN1/cN2) [

4]. Moreover, the EAU guidelines suggest offering a prophylactic pelvic lymph node dissection to patients with three or more positive inguinal nodes or extra nodal extension of cancer [

4]. As regards the timing of the procedure, the EAU guidelines suggest performing surgical inguinal and pelvic nodal extirpation within three months of diagnosis [

4], thereby highlighting the importance of an early lymphadenectomy to improve the patient’s outcome. In a retrospective study Kroon et al. compared the clinical outcome of early versus delayed excision of lymph node metastases in patients with penile cancer [

3]. By means of multivariate analysis, they demonstrated that early resection of occult inguinal metastases was an independent prognostic factor for disease specific survival [

3]. Based on a cohort study of 22 patients, Johnson et al. reported that early therapeutic dissection of lymph nodes was associated with an increased 3 and 5-years survival rate as compared with patients who underwent late dissections [

5]. The EAU guidelines highlight that a delay in nodal management of more than three to six months may reduce the disease-free survival [

4]. However, the strength of the EAU recommendation for a complete inguinal and pelvic nodal dissection within three months of diagnosis is weak and the level of evidence is 3 [

4]. The aim of this article is to review all available data on the impact of timing of inguinal and pelvic prophylactic lymph node dissection on the outcome in patients with penile cancer.

1.1. Research Questions

We put forth the following research query: What is the optimal timing of prophylactic inguinal and/or pelvic lymph node dissection after penile cancer diagnosis for the patients’ disease-specific survival rate?

To answer this query, we performed a systematic review of available studies that have been performed to evaluate the impact of prophylactic inguinal and/or pelvic lymph node dissection on patients’ survival rate.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Strategy

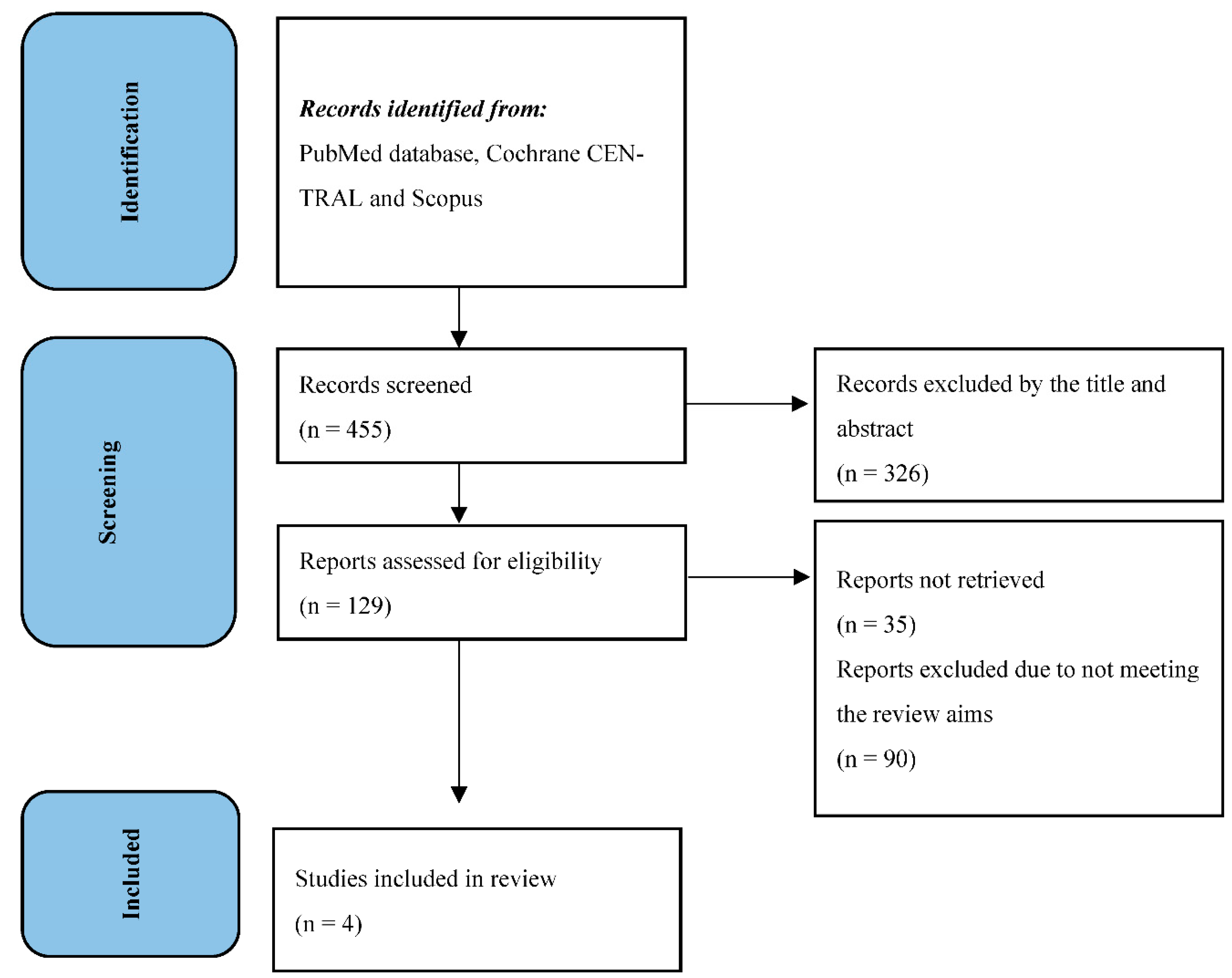

From December 2022 to February 2023, two independent reviewers (T.C. and M.C.) performed the research in PubMed database, Cochrane CENTRAL and Scopus. Any disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by consulting a supervisor (A.P.). All references cited in relevant articles were also reviewed and analyzed. The search strategy used was [((“Penile Neoplasms”[MeSH]) OR (penile cancer)) OR (penile carcinoma)) AND (lymph node excision [MeSH]) OR (lymph node dissection)) OR (lymphadenectomy)) OR (pelvic lymph node dissection)) OR (pelvic lymphadenectomy)) AND (survival)]. As filters, we used: clinical trial, humans, English language, and adult. Titles and abstracts were used to screen for initial study inclusion. Full-text review was used where abstracts were insufficient to determine if the study met inclusion or exclusion criteria. Two authors (T.C. and M.C.) independently performed all data analysis, including evaluation of the study characteristics, risk of bias and outcome measures, with independent verification performed by the supervisor. The study has been performed in line with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [

6]. All selected trials were used for the systematic review (

Figure 1).

3. Research Evidence

3.1. Indication for inguinal lymph node dissection

The lymphatic metastases from penile cancer follows the anatomical drainage route from the primary tumor to inguinal lymph nodes and, then to the ipsilateral pelvic lymph nodes. The lymphatic spreading to retroperitoneal nodes (para-aortic, para-caval) is classified as systemic metastatic disease. The overall survival rate is largely dependent on the extent of inguinal lymph node disease, with a 5-year survival rate for patients with a single involved inguinal node of approximately 80%, as compared with 0–12% if deeper pelvic lymph nodes are involved [

7]. In this sense, an early lymph node dissection seems to be related to a better outcome. As of today, inguinal lymph node dissection is recommended for patients with the following characteristics [

4,

7]:

- palpable lymph nodes (cN1-cN2)

- pT2 or higher penile cancer stage, even if in case of non-palpable lymph nodes

- presence of lymphovascular invasion

- poorly differentiated histology

Imaging is of limited value when palpable lymph nodes are found on clinical examination. Radiological evaluation with CT scan or MRI is only indicated to detect distant metastasis. However, CT scan or MRI findings do not alter the patients’ management [

7]. In everyday clinical practice patients undergo antibiotic treatment if there is suspicion that enlarged lymph nodes may be due to an infection, even if this practice is not supported by guidelines recommendations. In select cases, fine needle aspiration cytology is an option to clarify the reason for enlarged lymph nodes, having a sensitivity of 93%, and specificity of 91% in predicting metastatic disease [

8]. However, the role of fine needle aspiration cytology is decreasing in recent years due to the risk of overlooking micro-metastasis [

7]. Patients with fixed or bulky nodal disease diagnosed on clinical exam (cN3) indicates extensive lymphatic metastatic disease with a poor prognosis. In such cases a total body CT scan is required to look for distant metastasis and consider the need for chemotherapy [

9]. The role of inguinal lymph nodes dissection is extremely important in the management of penile cancer patients and the indications for the procedure should be respected and followed duly, as reported by Ren et al. [

10].

3.1.1. Timing of inguinal lymph node dissection

Even if the indications for the lymph node dissection are clear and well described in international guidelines [

4,

9], there is no consensus on the timing of the dissection. In cN0 patients (non-palpable lymph nodes), an early inguinal lymph nodes dissection is associated with a better survival rate than delayed dissection (within six weeks of primary surgical treatment vs. surgery following identification of positive nodes during surveillance) [

3,

4,

5]. In case of pN1-N2 patients the evidence is not clear. Some authors report a better outcome after early inguinal lymph node dissection (within 3 months from penile cancer diagnosis) [

11], while other authors consider a time interval of less than 6 months from primary surgery as critical for the survival rate [

12]. Available evidence about the timing of inguinal lymph node dissection does not support clear recommendation of a specific time interval from diagnosis to lymph node dissection. International guidelines highlight that a delay in nodal management of more than three to six months may affect patients’ survival [

3,

4,

5]. Recently, Ma et al. demonstrated in a retrospective, single-center study that among high-risk patients, 3.5 months is a safe oncological interval before surgical management of inguinal lymph nodes [

13]. They also concluded that cN0 penile cancer patients at high risk of inguinal lymphatic metastasis (pT1G3 and all higher stage tumors) benefit from simultaneous resection of the primary tumor and inguinal lymph nodes or a prophylactic inguinal lymphadenectomy within 3 months after diagnosis [

13]. We therefore consider three months as a safe oncological window to ensure optimal survival rate.

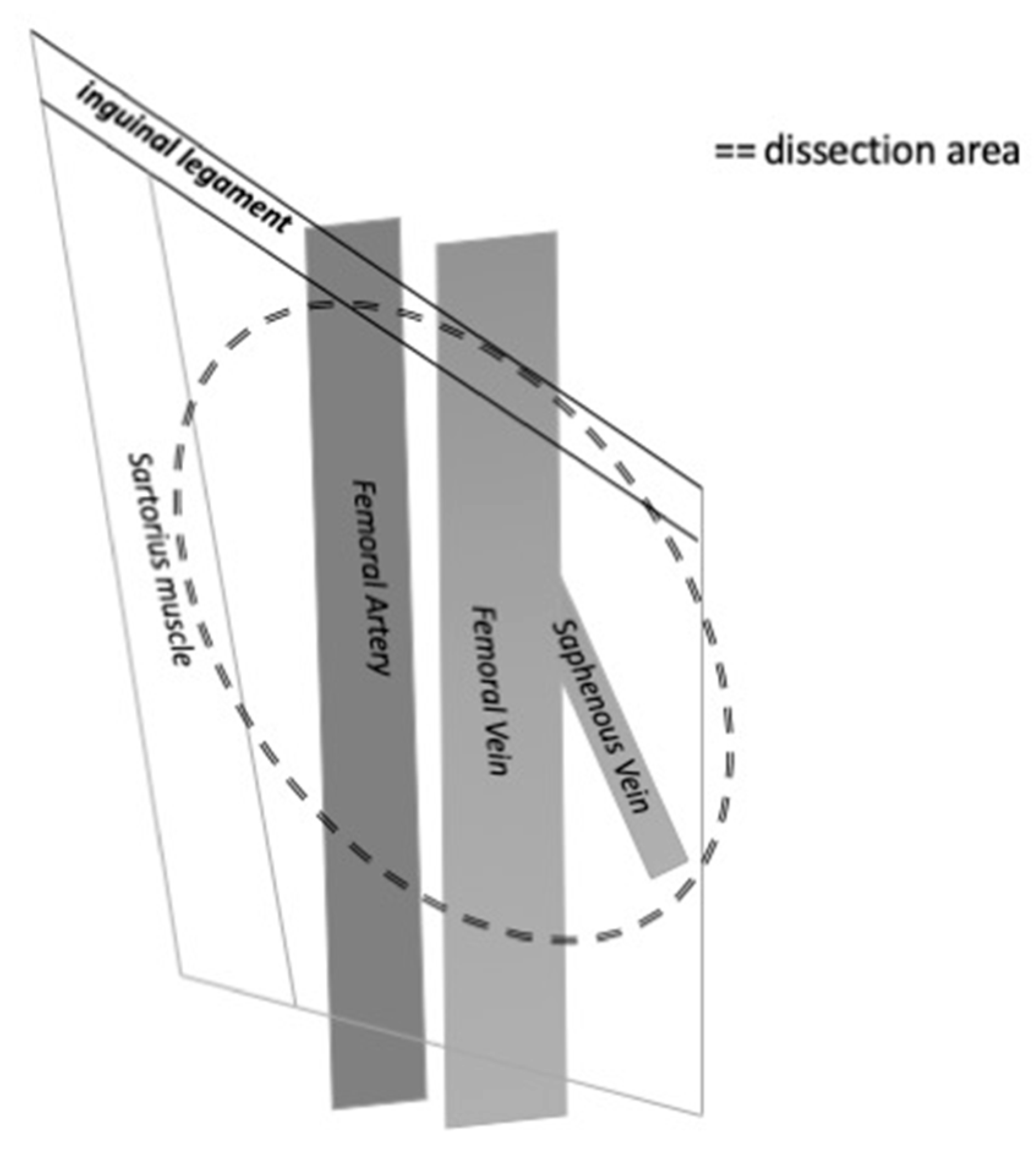

3.1.2. Anatomical considerations of inguinal lymph node dissection

The inguinal nodes are located close to the saphenous vein and femoral vessels within the femoral triangle, demarcated by the inguinal ligament superiorly, the adductor longus muscle medially and the sartorius muscle laterally [

7]. The extension of the lymph node dissection should be balanced with the risk of complications due to the dissection. Several modifications of the dissection technique have been reported to minimize morbidity and complications. It is mandatory to include the central and the superior zone of lymphatic tissue in the dissection. A modified inguinal lymph node dissection includes a smaller skin incision, preservation of the saphenous vein, conservation of the region superior to the fossa ovalis and lateral to the femoral artery and maintaining the sartorius muscle in situ [

14]. This procedure has been associated with a decreasing rate of major complications [

15], while maintaining the rate of diagnostic accuracy and survival rate. On the other hand, a superficial lymph node dissection has been purposed with interesting results. This procedure is performed via a 6–8 cm incision parallel and inferior to the inguinal crease, and involves dissection of flaps deep to Scarpa’s fascia. The fascia lata is kept intact, while all nodal tissue superficial to it is removed. Compared to the modified inguinal lymph node dissection, the boundaries of the superficial dissection are extended medially and laterally to include the midpoint of the adductor longus muscle and the lateral boundary of the midpoint of the sartorius muscle. The long saphenous vein is preserved [

16].

Figure 2.

The figure shows the anatomical limits of inguinal lymph nodes dissection on the right side.

Figure 2.

The figure shows the anatomical limits of inguinal lymph nodes dissection on the right side.

3.2. Indications for pelvic lymph node dissection

According to the EAU guidelines, prophylactic pelvic lymph node dissection should be offered to all patients with three or more positive inguinal nodes or with extra nodal extension of cancer in inguinal nodes [

4]. The accuracy of CT-scan or PET/CT scan to detect metastases in pelvic lymph nodes is low, just as for detecting metastases in inguinal lymph nodes. Sadeghi reported in a systematic review and metanalysis that 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging has relatively low sensitivity for detection of inguinal lymph node involvement in penile cancer patients and does not recommend this examination for routine use [

17]. On the other hand, they suggested performing 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging in patients with palpable inguinal lymph nodes due to its higher sensitivity in this subgroup of patients [

17]. However, the presence of palpable inguinal lymph nodes is an indication for inguinal lymph node dissection. Recently, a systematic review and metanalysis by Lee et al. showed that 18F-FDG PET/CT had a good diagnostic performance for detection of metastatic lymph nodes, refreshing the role of this imaging modality in the diagnostic work-up of patients with penile cancer [

18]. The role of 18F-FDG PET/CT in diagnostic pathway is justified by enhanced anatomical information as compared to the cross-sectional assessment of CT scans. Lymph nodes of normal size that harbor malignant deposits can be detected by FDG PET/CT due to increased metabolism, but not by CT alone [

19]. However, in everyday clinical practice the positive pelvic lymph nodes at PET/CT or CT should not be considered an indication for pelvic lymph node dissection unless there is histopathologically confirmed homolateral inguinal metastasis.

3.2.1. Timing of pelvic lymph node dissection

International guidelines suggest performing surgical inguinal and pelvic nodal management within three months of diagnosis [

4]. This recommendation is based on the association between the presence of lymph node metastases and patients’ survival rate. The recommendation is controversial as it is given even though there is poor evidence that pelvic lymph node dissection improves survival compared to adjuvant radiotherapy or surveillance only. Recently, great attention has been given to percutaneous biopsy of enlarged pelvic lymph nodes. The NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology on Penile Cancer suggest performing a percutaneous lymph node biopsy, if technically feasible, and to decide on pelvic lymph node dissection on the basis of biopsy results [

20]. However, if pelvic lymph node metastases are suspected on imaging or biopsy we believe pelvic lymph node dissection should be performed as early as possible in order to avoid further spread of penile cancer cells.

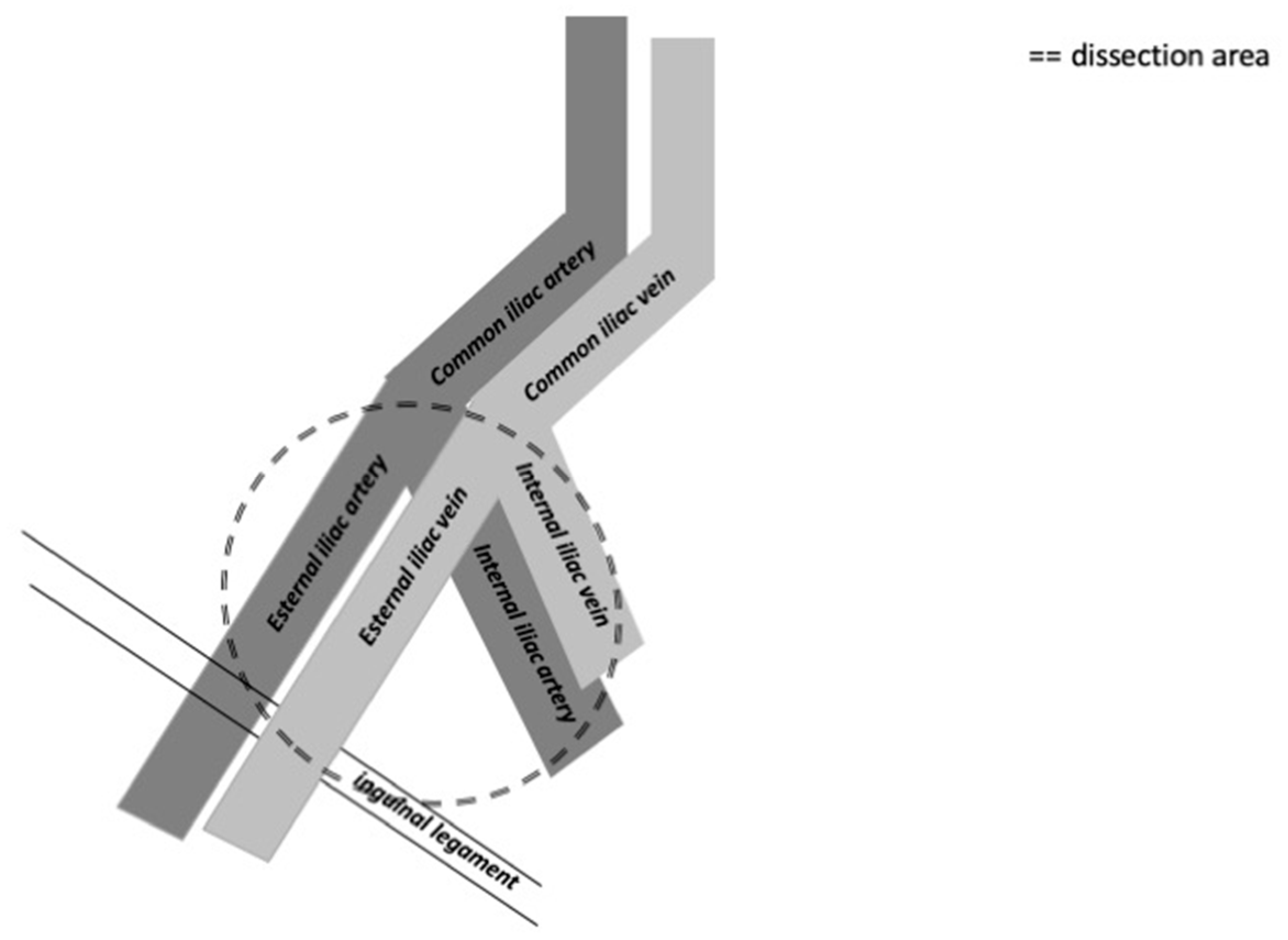

3.2.2. Anatomical considerations of pelvic lymph node dissection

The distribution of the most common positive lymph nodes is external iliac, obturator, common iliac, internal iliac and presacral zones, according to Yao et el. [

21]. Crossover metastasis from one inguinal region to the contralateral pelvic region is very rare [

21]. The external iliac zone is more often involved than the obturator and common iliac zones [

22]. The template used for cystectomy is applicable also for penile cancer and typically includes the distal common iliac, the external iliac, the obturator and the internal iliac lymph nodes bilaterally [

23]. The anatomical limits are the common iliac bifurcation cranially and the inguinal ligament caudally. Laterally the boundary is the genitofemoral nerve and medially it is the bladder wall.

Figure 3.

The figure shows the anatomical limits of pelvic lymph nodes dissection on the right side.

Figure 3.

The figure shows the anatomical limits of pelvic lymph nodes dissection on the right side.

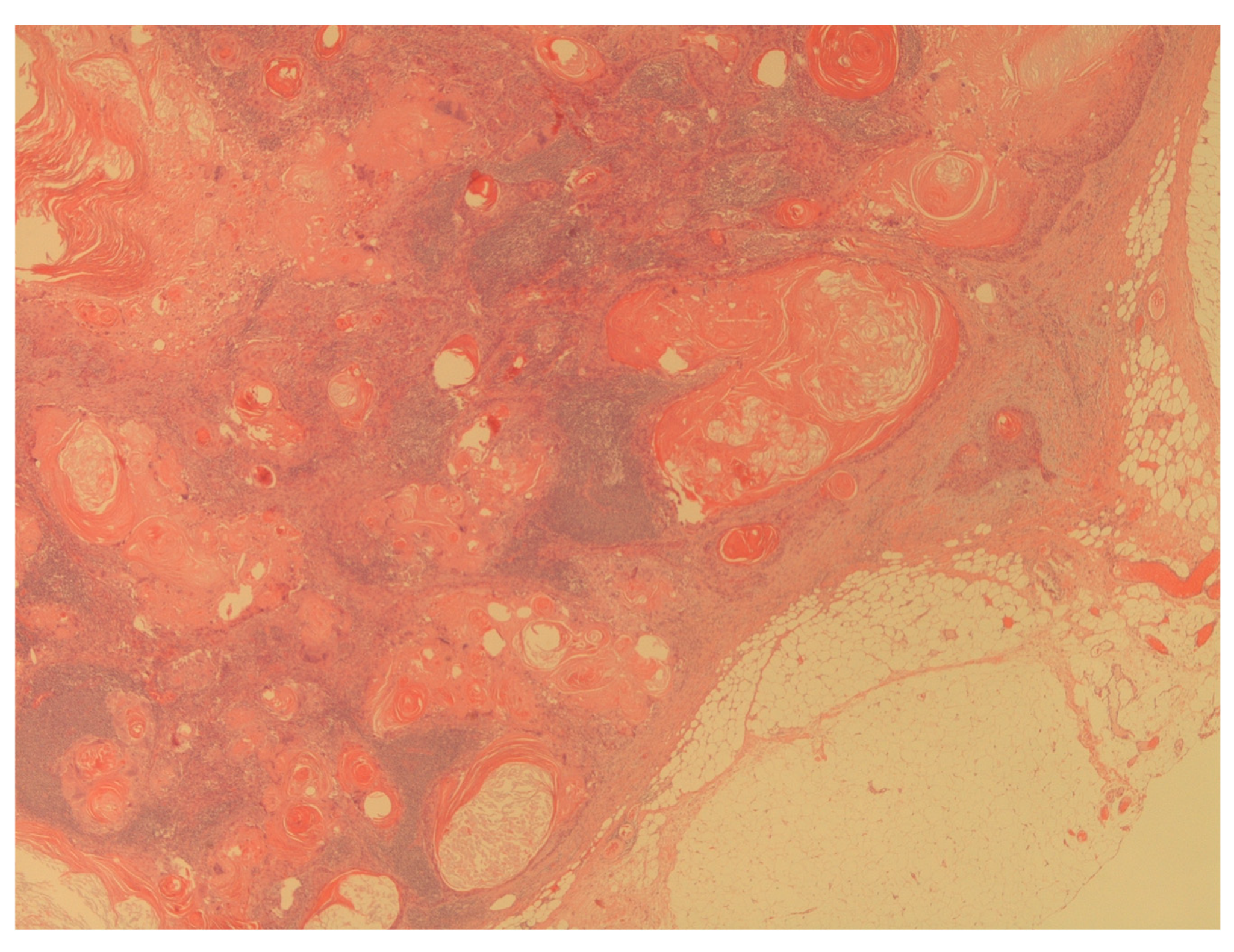

3.3. Pathological considerations on lymph node analysis

Histologic grade and tumor stage are important prognostic factors in patients affected by penile cancer. Ficarra et al. demonstrated that histological grade can be considered a predictive prognostic factor in patients with lymph nodes metastasis, too [

24]. In this sense, the correct assessment of histologic grade is essential in the management planning of patients with penile cancer. Moreover, as stated before, the EAU guidelines recommended to perform a prophylactic pelvic lymph node dissection to all patients with three or more positive inguinal nodes or with extra nodal extension of cancer in inguinal nodes [

4]. The following parameters of pathological analysis should be considered in the planning of patients’ management:

- -

presence of penile cancer lymph nodes metastasis

- -

number of lymph nodes involved

- -

presence of extra nodal extension of cancer in lymph nodes

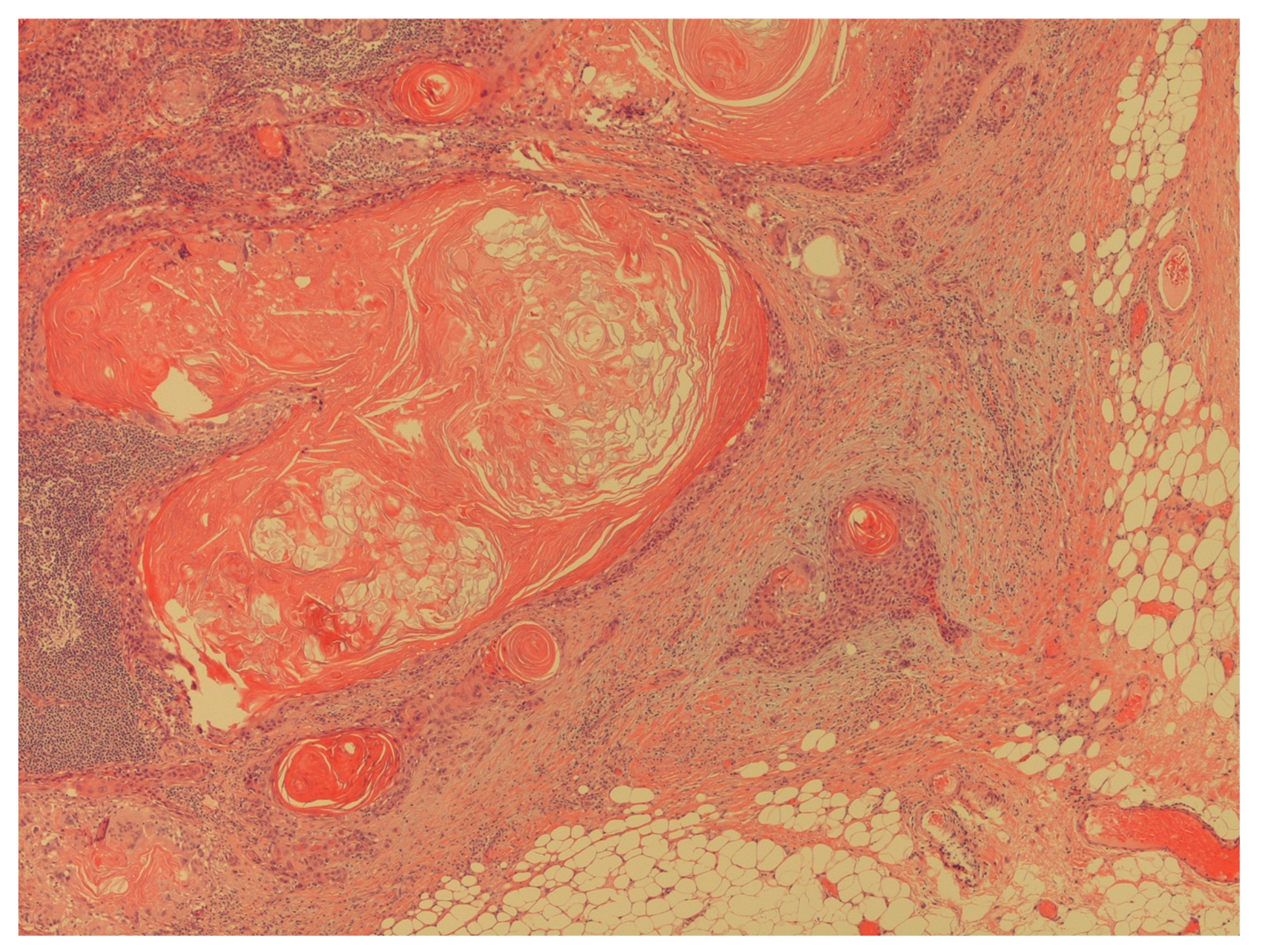

Figure 4.

The figure shows a massive lymph node metastasis from squamous cell carcinoma (H&E; 20X).

Figure 4.

The figure shows a massive lymph node metastasis from squamous cell carcinoma (H&E; 20X).

Figure 5.

The figure shows an extracapsular neoplastic extension by foci of squamous cell carcinoma (H&E; 40X).

Figure 5.

The figure shows an extracapsular neoplastic extension by foci of squamous cell carcinoma (H&E; 40X).

3.4. Systematic review findings on timing of lymph node dissection

In order to demonstrate the impact of the timing of the lymph node dissection on survival rate in patients with penile cancer, we included 4 papers (

Table 1). The lack of randomized clinical trials is the reason for not performing a regular systematic review. All included studies argue for an early lymph node dissection in order to improve patients’ survival [

3,

5,

11,

12]. As regards the exact timing of dissection, Kroon et al. identified a cut-off at 6 months as the best interval for the resection of lymph nodes [

3]. On the other hand, Chipollini et al. recommended 3 months as the upper time limit for performing inguinal lymph node dissection [

11] while Gulia et al. suggest performing inguinal lymph node dissection within 2 months of diagnosis [

12]. No studies address the best timing for pelvic lymph nodes dissection. On the basis of these studies, and despite the lack of randomized and controlled trial, we recommend that lymph node dissection should be performed as soon as possible after diagnosis, with 3 months as a realistic upper cut-off time.

4. Limitations, future perspectives and conclusions

Penile cancer is an aggressive disease that requires early management. The survival rate depends on an early surgical approach in order to avoid cancer spread into regional lymph nodes and to distant metastases [

4]. Metastatic involvement of inguinal lymph nodes is the most important prognostic indicator in penile cancer and understanding the optimal time and extension of prophylactic lymph node dissection is therefore essential. There are also other gray zones related to lymph node dissection in penile cancer. Recently, Suarez-Ibarrola et al. suggested that despite the rarely found crossover metastasis from inguinal to pelvic lymph nodes, bilateral pelvic lymph node dissection should be performed even if the ideal candidate is yet to be determined [

25]. Finally, a special attention on the impact of lymph nodes dissection on patients’ quality of life should be considered [

26].

The lack of deep knowledge about the role of lymph node dissection in penile cancer is due also to clinical heterogeneity among published clinical studies. There is no generally accepted indication for the lymph node dissections; different lymph node dissection templates are being used, there are low number of included patients in published series and the interference of neo/adjuvant treatments varies. No clinically relevant predictive tools are available for assessing the risk of inguinal or pelvic lymph nodes metastases. The indications for performing lymph node dissection is based on retrospective studies and recommendations on timing are based on expert opinion, resulting in weak grades of recommendations by international guidelines. No molecular data are available for use in everyday clinical practice to guide the extent of surgery or adjuvant treatment. Genetic analysis of the primary tumor and metastatic cells in lymph nodes might give us molecular parameters to assess the risk of metastatic spread and survival rate.

In conclusion, all patients with penile cancer should be offered lymph nodes dissection as soon as possible to avoid spread of cancer cells and improve survival. Three months is regarded the upper limit for the time interval between diagnosis and lymph node dissection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.C.; methodology, T.C. and M.C.; software, T.C..; formal analysis, T.C., M.C.; data curation, T.C. and M.C.; writing—original draft preparation, T.C., and TEBJ; writing—review and editing, A.P. and TEBJ; supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Salvioni, R.; Necchi, A.; Piva, L.; Colecchia, M.; Nicolai, N. Penile cancer. Urol Oncol 2009, 27, 677–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Z.; Wu, T.; Wang, S.; Wu C, Pan L, Jiang X, Guan Z, Wang Y, Jiao D, Yan F, Zhang K, Tang Q, Ma J. Prophylactic inguinal lymphadenectomy for high-risk cN0 penile cancer: The optimal surgical timing. Front Oncol 2023, 13:1069284. PMID: 36895485; PMCID: PMC9989449. [CrossRef]

- Kroon, B.K.; Horenblas, S.; Lont, A.P.; Tanis, P.J.; Gallee, M.P.; Nieweg, O.E. ; Patients with penile carcinoma benefit from immediate resection of clinically occult lymph node metastases. J Urol 2005, 173, 816–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

-

https://d56bochluxqnz.cloudfront.net/documents/full-guideline/EAU-ASCO-Guidelines-on-Penile-Cancer-2023_2023-03-08-131333_piyo.pdf.

- Johnson, D.E.; Lo, R.K. Management of regional lymph nodes in penile carcinoma. Five-year results following therapeutic groin dissections. Urology 1984, 24, 308-11. [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Group, P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 2009, 151:264-9, W64. -9.

- The, J.; Duncan, C.; Qu, L.; Guerra, G.; Narasimhan, V.; Pham, T.; Lawrentschuk, N. Inguinal lymph node dissection for penile cancer: a contemporary review. Transl Androl Urol 2020, 9, 3210–3218, PMID: 33457292; PMCID: PMC7807325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saisorn, I.; Lawrentschuk, N.; Leewansangtong, S.; Bolton, D.M. Fine-needle aspiration cytology predicts inguinal lymph node metastasis without antibiotic pretreatment in penile carcinoma. BJU Int 2006, 97, 1225–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, P.E.; Spiess, P.E.; Agarwal, N.; Biagioli, M.C.; Eisenberger, M.A.; Greenberg, R.E.; Herr, H.W.; Inman, B.A.; Kuban, D.A.; Kuzel, T.M.; Lele, S.M.; Michalski, J.; Pagliaro, L.; Pal, S.K.; Patterson, A.; Plimack, E.R.; Pohar, K.S.; Porter, M.P.; Richie, J.P.; Sexton, W.J.; Shipley, W.U.; Small, E.J.; Trump, D.L.; Wile, G.; Wilson, T.G.; Dwyer, M.; Ho, M.; National Comprehensive Cancer, Network. . Penile cancer: Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2013, 11, 594–615, PMID: 23667209; PMCID: PMC4042432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Shao, Y.; Bao, Y.; Li, X. Prediction of survival in patients with penile cancer after lymph node dissection. Asian J Surg 2022, 45, 1700–1702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chipollini, J.; Tang, D.H.; Gilbert, S.M.; Poch, M.A.; Pow-Sang, J.M.; Sexton, W.J.; Spiess, P.E. Delay to Inguinal Lymph Node Dissection Greater than 3 Months Predicts Poorer Recurrence-Free Survival for Patients with Penile Cancer. J Urol 2017, 198, 1346–1352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulia, A.K.; Mandhani, A.; Muruganandham, K.; Kapoor, R.; Ansari, M.S.; Srivastava, A. Impact of delay in inguinal lymph node dissection in patients with carcinoma of penis. Indian J Cancer 2009, 46, 214–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, S.; Zhao, J.; Liu, Z.; Wu, T.; Wang, S.; Wu, C.; Pan, L.; Jiang, X.; Guan, Z.; Wang, Y.; Jiao, D.; Yan, F.; Zhang, K.; Tang, Q.; Ma, J. Prophylactic inguinal lymphadenectomy for high-risk cN0 penile cancer: The optimal surgical timing. Front Oncol 2023, 13:1069284. PMID: 36895485; PMCID: PMC9989449. [CrossRef]

- Catalona, W.J. Modified inguinal lymphadenectomy for carcinoma of the penis with preservation of saphenous veins: technique and preliminary results. J Urol 1988, 140, 306–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spiess, P.E.; Hernandez, M.S.; Pettaway, C.A. Contemporary inguinal lymph node dissection: minimizing complications. World J Urol 2009, 27, 205–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bevan-Thomas, R.; Slaton, J.W.; Pettaway, C.A. Contemporary morbidity from lymphadenectomy for penile squamous cell carcinoma: the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Experience. J Urol 2002, 167, 1638–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, R.; Gholami, H.; Zakavi, S.R.; Kakhki, V.R.; Horenblas, S. Accuracy of 18F-FDG PET/CT for diagnosing inguinal lymph node involvement in penile squamous cell carcinoma: systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Clin Nucl Med 2012, 37, 436–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.W.; Kim, S.J. Diagnostic Performance of 18F-FDG PET/CT for Lymph Node Staging in Penile Cancer. Clin Nucl Med 2022, 47, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakobsen, J.K.; Frahm Nielsen, T.; Ipsen, P.; Albrecht-Beste, E.; Cardoso Costa, J.; Alslev, L.; Predbjørn Krarup, K.; Grønkaer Toft, B.; Høyer, S.; Bouchelouche, K.; Bjerggaard Jensen, J. DaPeCa-7: comparative assessment of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/computed tomography (CT) and conventional diagnostic CT in diagnosis of lymph node metastases, distant metastases and incidental findings in patients with invasive penile cancer. BJU Int 2021, 127, 254–262, Epub 2020 Sep 7. PMID: 33448605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

-

https://www2.tri-kobe.org/nccn/guideline/urological/english/penile.pdf.

- Yao, K.; Chen, Y.; Ye, Y.; Wu, Z.; Chen, D., Han, H.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Qin, Z.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.; Zhou, F. Lymph Node Mapping in Patients with Penile Cancer Undergoing Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection. J Urol 2021, 205: 145.

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, S.L.; Ye, D.W.; Yao, X.D.; Dai, B.; Zhang, H.L.; Shen, Y.J.; Zhu, Y.P.; Shi, G.H.; Ma, C.G. Prospectively packaged ilioinguinal lymphadenectomy for penile cancer: the disseminative pattern of lymph node metastasis. J Urol 2009, 181: 2103.

- Perera, M.; McGrath, S.; Sengupta, S.; Crozier, J.; Bolton, D.; Lawrentschuk, N. Pelvic lymph node dissection during radical cystectomy for muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Nat Rev Urol 2018, 15:686–92. [CrossRef]

- Ficarra, V.; Martignoni, G.; Maffei, N.; Cerruto, M. A.; Novara, G.; Cavalleri, S.; Artibani, W. . Predictive pathological factors of lymph nodes involvement in the squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. International Urology and Nephrology 2002, 34, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- uarez-Ibarrola, R.; Basulto-Martinez, M.; Sigle, A.; Abufaraj, M.; Gratzke, C.; Miernik, A. Is There an Oncological Benefit of Performing Bilateral Pelvic Lymph Node Dissection in Patients with Penile Cancer and Inguinal Lymph Node Metastasis? J Clin Med. 2021, 10, 754. Published online 2021 Feb 13. [CrossRef]

- Cai, T.; Verze, P.; Bjerklund Johansen, T.E. The Quality of Life Definition: Where Are We Going? Uro 2021, 1, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).