1. Introduction

Health literacy, as put by the [

1] and by [

2], has had many meanings throughout time with different emphasis and varying levels of specificity. In this article, we approach the field of health literacy connected to public health, aiming to identify key trends in the literature and assess the development of academic research in the area. We have opted to implement bibliometric analysis for this study to show how the field has advanced through time, how authors have networked, and emerging trends.

We have chosen to pair health literacy with terms related to public health as a way to focus our analysis on the social impact of health literacy, looking at articles that articulate health literacy with its societal impacts. This was done through filters applied in the queries to limit the scope of the corpus obtained.

However, it is important to note that health literacy is a broad concept with different meanings, as put by [

2]. It refer to different ways that an individual deals with their health and health information, with functional health literacy, interactive health literacy and critical health literacy all measuring different aspects of the concept [

3,

4,

5]. The functional health literacy dealing with basic understanding of information, interactive health literacy measuring the capacity to extract information and interpret different forms of communication and critical health literacy referring to the capacity to critically analyze health information and to use it to obtain greter agency over one’s life.

This scenario exacerbated the importance of providing proper guidance and information to the population to solve public health problems. However, the relationship between health literacy and public health is relevant outside of a health crisis and the infodemic scenario. Health literacy focuses on the capacity of individuals to access and understand health information and services [

2], which makes it possible for them to make appropriate decisions regarding their health [

6]. The importance of health literacy, however, is broader than the individual level, as low health literacy is associated with higher mortality [

7], increased hospitalizations [

8], lower vaccination rates [

9], which results in higher health care costs[

10], and lower productivity [

2].

Despite being usually thought of as something beneficial, it is important to point out potential negative aspects of health literacy. There is often an over-emphasis of the individual, be it their own capacity to self-manage, without considering social networks and different sources of structural social support [

11]. This higher emphasis on the individual can also lead to problems given that overconfidence in self-management capabilities can lead to individuals not seeking professional medical attention when needed [

12]. High health literacy can also have unintended consequences such as a higher critical health literacy leading to vaccination hesitancy [

13].

We have applied bibliometric analysis technique, through the use of the Bibliometrix package on R [

14,

15] to determine relevant authors, journals and topics inside the corpus of articles that we have selected. These aspects are capable to delineate the effects of the pandemic and its consequences on the literature.

We have also used machine learning in order to selection to identify the most important keywords to predict the paper’s number of citations per year. This approach was also implemented by [

16] in the Interbank Financial Networks literature and provides relevant insight on the best practices to those aiming to publish in the area.

Through this article, we hope to shed light on the state-of-the-art scientific research on health literacy and its association with public health as well as showing most relevant themes and keywords on the area and stimulate further research.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

We obtained the data used in this article from the Scopus and Web of Science and Pubmed databases. We employ as queries "health literacy" along with terms relating to public health with the results restricted to academic articles in English. We opted for this query to select articles that focused on the broader impact of health literacy and its positive effects on society.

We can observe the specific queries used in each database below:

Scopus: TITLE-ABS-KEY ALL=("Health Literacy" AND ("Public Health" OR "Health Care Policy" OR "Health Services" OR "Health Care Quality" OR "Health Policy" OR "Health Promotion" OR "Public Health Service")) AND ( EXCLUDE ( PUBYEAR,2023) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( DOCTYPE,"ar" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( SRCTYPE,"j" ) ) AND ( LIMIT-TO ( LANGUAGE,"English" ))

Web of Science: ALL=("Health Literacy" AND ("Public Health" OR "Health Care Policy" OR "Health Services" OR "Health Care Quality" OR "Health Policy" OR "Health Promotion" OR "Public Health Service")) and 2023 (Exclude – Publication Years) and Article (Document Types) and English (Languages) and Article (Document Types)

Pubmed: Search: ("Health Literacy" AND ("Public Health" OR "Health Care Policy" OR "Health Services" OR "Health Care Quality" OR "Health Policy" OR "Health Promotion" OR "Public Health Service")) Filters: Abstract, English, from 1992 - 2022

These queries yielded a total of 9925 articles, once the duplicates were removed. The Scopus database resulted in 5505 articles, and the Web of Science resulted in 5150 articles and the Pubmed resulted in 7102.

2.2. Methodology

2.2.1. Citation likelihood

We also applied a white-box linear regression estimated with OLS, similar to the one employed by [

16], using the output of Random Forest Algorithm applied to dummy variables representing the the presence of keywords in order to predict the average citations per year:

Where ’i’ refers to the paper’s ID, ’’ is the average citations per year of the paper ’i’, ’’ refers to the age of the paper,’’ is a dummy variable representing whether paper ’i’ was written by a single author ’’ is the number of authors in the paper ’i’, and ’’ are dummy variables that represent whether each of the top 20 keywords for predicting average citations per year, as estimated by the Random Forest model, are present in paper ’i’. We use robust error clustering at the paper level and show a version with fixed effects for the age of the paper. This way, we can make our model robust for unobserved aspects regarding individual differences amidst the papers that could impact the dependent variable, and we can also show the model taking the age variable into account and controlling for it.

2.2.2. Bibliometric

This study applies bibliometric analysis to the data gathered from Scopus and Web of Science regarding the literature on health literacy. In order to evaluate the state-of-the-art on the theme, we have employed the Bibliometrix 4.1.2 package on the statistical programming language R.

The bibliometric approach allows for a reproducible, systematic, and transparent study [

14,

15]. More specifically, we have used the functions of the Bibliometrix package to explore the peculiarities of the vast corpus in question. This package allows the charting of descriptive data regarding the scientific production on the chosen topic and other bibliometric methods such as Lotka’s Law.

Lotka’s Law refers to a mathematical model capable of measuring the productivity of authors, assessing the contribution of different researchers to the progress of science, and evaluating the distribution of scientific production [

17].

According to [

17], the number of authors who make ’n’ contributions in a specific field of scientific knowledge is approximately

of those who make only one. Lotka’s Law can be formally represented as follows [

17]:

where ’y’ is the frequency of authors who have published ’x’ amount of articles, ’n’ represents the degree of inequality in the distribution of productivity, and "const" represents a constant value that remains the same as x and y vary, being the total amount of articles observed.

We apply this formula to quantify the distribution of scientific production in a specific field. Our main aim in applying Lotka’s Law is to determine how many researchers are highly productive in the health literacy area and how many have published a low number of articles in this specific area.

3. Results

The term health literacy gained popularity in the decade of 1990 [

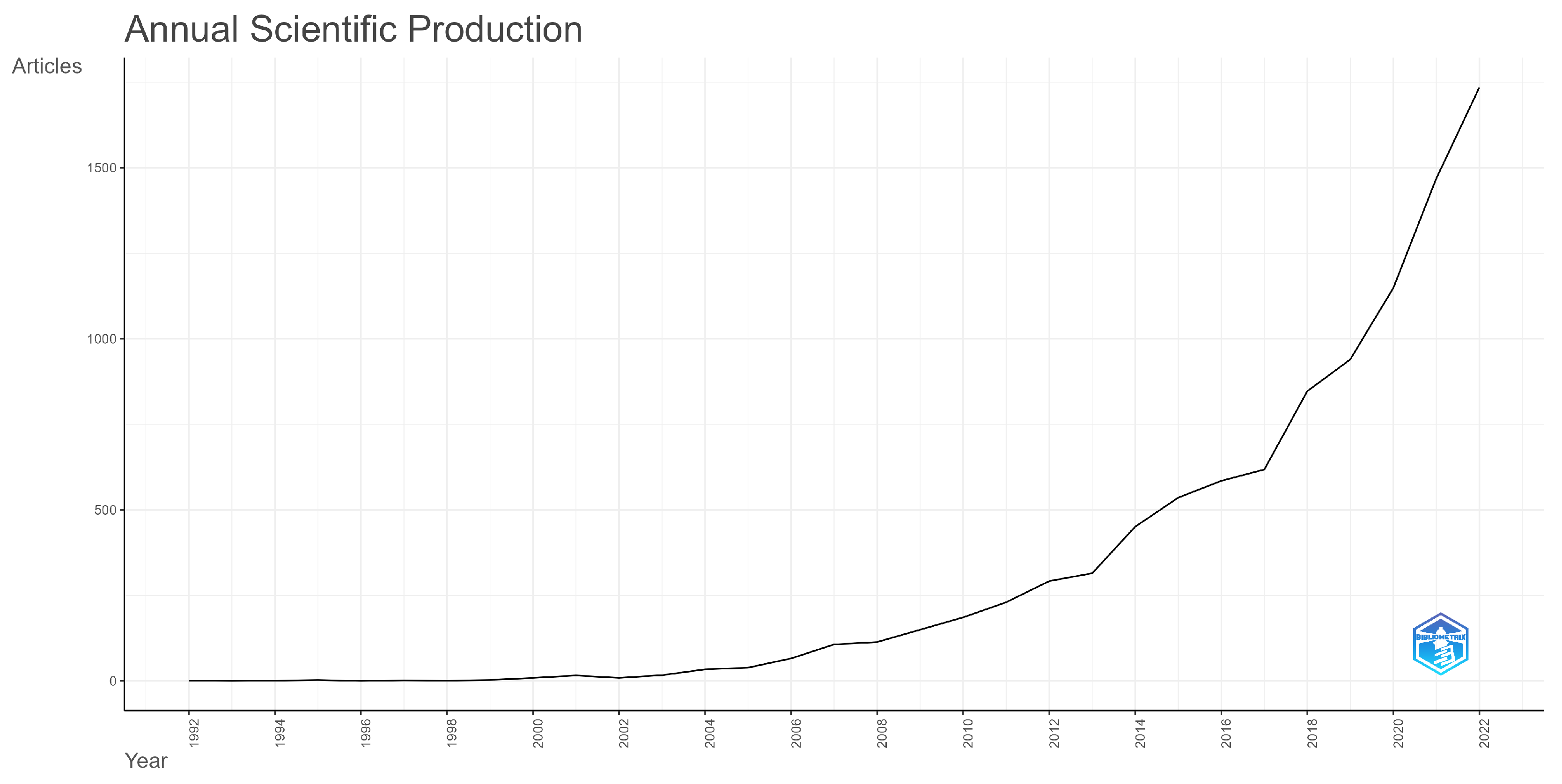

18] and has been more researched as time went on. This can also be observed in the case of health literacy being studied with a focus on public health, as can be seen in

Figure 1.

Figure 1 shows how the research on health literacy and public health has been expanding. This growth has been more pronounced in recent years. The mean amount of articles published from 2000 to 2010 being 67.91 and from 2011 to 2022 that mean grows to 773.92. In 2022 alone 1735 articles have been published on the theme.

3.1. Citation likelihood

For our Random Forest Model, we began by dividing the papers in two sets, a testing set with 20 % of papers and a training set with the remaining 80%. We have applied the model selection procedure to the training set to determine the optimal parameters that maximize the Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE),a metric known for its sensitivity to large errors and ability to provide a direct interpretation in the context of the original scale of the data [

19,

20]. With the optimal parameters we have estimated the model on the testing set.

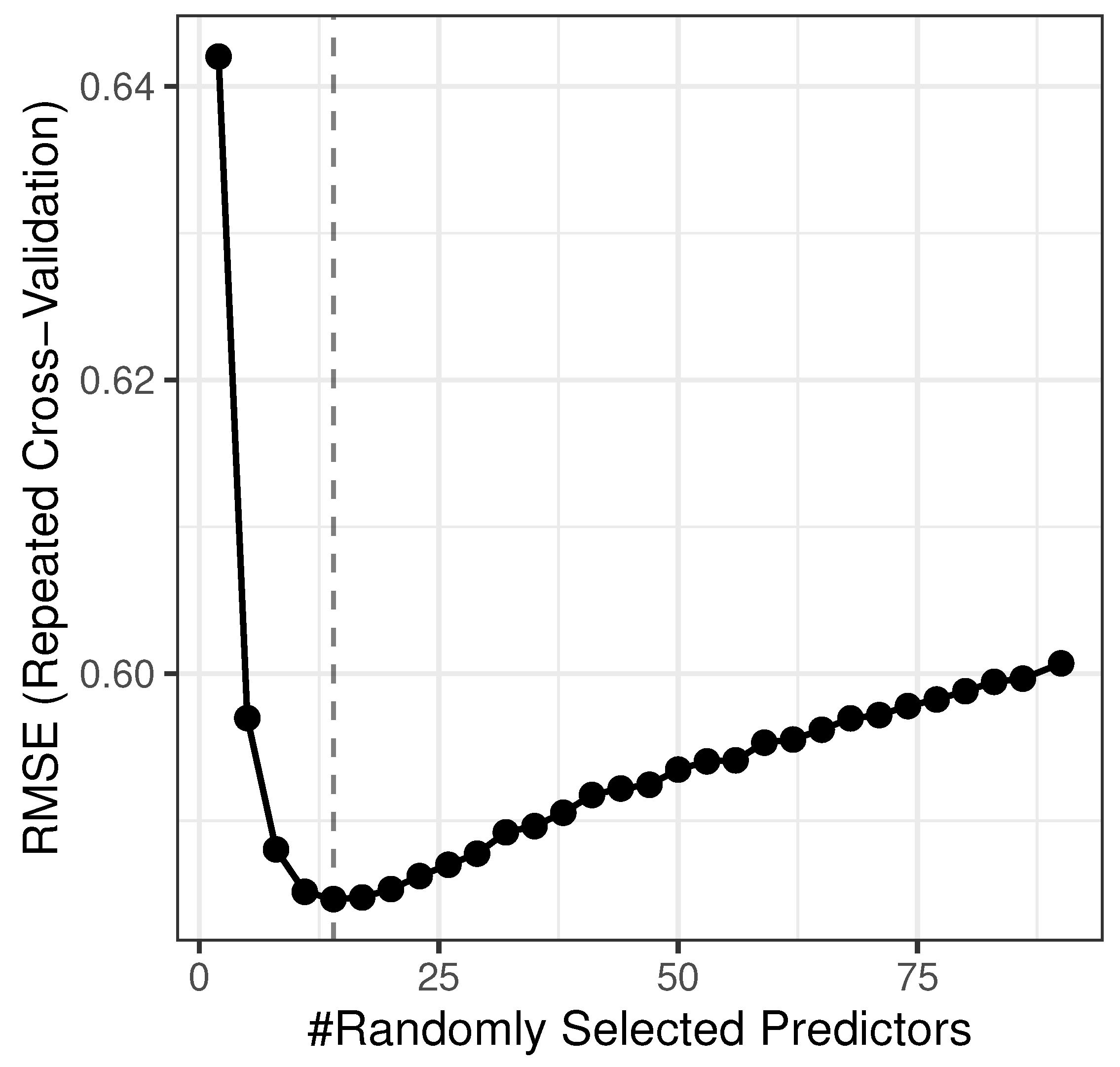

For the first step of selecting the parameters, we have, similarly to [

16], defined the amount of trees as 500 and then we have tested the resulting RMSE for each mtry, as can be seen on

Figure 2, which exhibits the results of a repeated k-fold cross-validation procedure. The mtry selected was 4, as it was the value that minimized the RMSE.

The trained model was then used to identify the most important keywords to predict high or low number of average citations per year. The top 20 keywords were then selected as the

variable for the estimation of the model of Eq.

1. The resulting coefficients are presented in

Table 1, with both the model presenting

as an independent variable, on the first column, and the model using fixed effects to control for the age of the paper being estimated, on the second column.

On

Table 1 first coefficient, on the first column, shows that the age of the paper is relevant to its average citations per year, as can be expected given that established papers will be cited and through its citations will be read by more people and also due to the fact that seminal authors will be widely cited in the literature.

Regarding the effect of the amount of authors on the citations, unlike the results found by [

16] on the Interbank Financial Networks literature, whether the paper is single authored is not a significant predictor of citations. However, the amount of authors has a positive effect, which indicates that collaboration amidst authors tends to yield positive results in the area of health literacy.

Now regarding the keywords being analyzed, eight of them show a positive and significant coefficient, with three of those having the p-value above 0.05. Those keywords are: Article, Cross sectional study, Questionnaire, Male, Behavior (with a p-value > 0.01), Covid 19, Public health (with a p-value > 0.05) and Mental health (with a p-value > 0.05).

It is note worthy that the Covid 19 keyword has shown the highest coefficient in both models, despite being a relatively recent phenomena. This makes sense due to the fact that the Covid-19 pandemic and the public health crisis subsequent to it was an event closely related to health literacy as the lack of information and guidelines was a big problem, especially in the first moments of the crisis. Many people were overwhelmed by both accurate and inaccurate information, which were difficult to distinguish apart, especially given the unfamiliarity of the situation [

21,

22,

23,

24].

Other keywords with a positive coefficient that can give insight on the literature is the ’Questionnaire’ and the ’Cross sectional study’ which indicates that this literature cites empirical studies more frequently. Especially due to the fact that health literacy is often measured using questionnaires, such as the Health Literacy Questionnaire [

25], the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire [

26,

27] and the Mental Health Literacy Scale [

28].

Four keywords show a significant and negative coefficient. Those keywords are: ’Human’, ’Health knowledge attitudes practice’, ’Female’ and ’Surveys and questionnaires’.

It is interesting to note that articles with the ’Male’ keywords had more citations than those with the ’Female’ keyword, indicating a possible bias in the scientific community. Another noteworthy aspect here is the positive coefficient for the ’Questionnaire’ and negative coefficient for the ’Surveys and questionnaires’ keyword, which could indicate that the first keyword is more relevant due to it being more rigorous on the instrument being used, despite the fact that many surveys use questionnaires in them.

Regarding the model itself, due to the nature of citation, there are aspects many of which can’t be easily captured or quantified in a model, such as whether the authors are established authors on the literature, or even the quality of the article itself. This nature of the data being predicted explains the relatively low of the model.

3.2. Sources

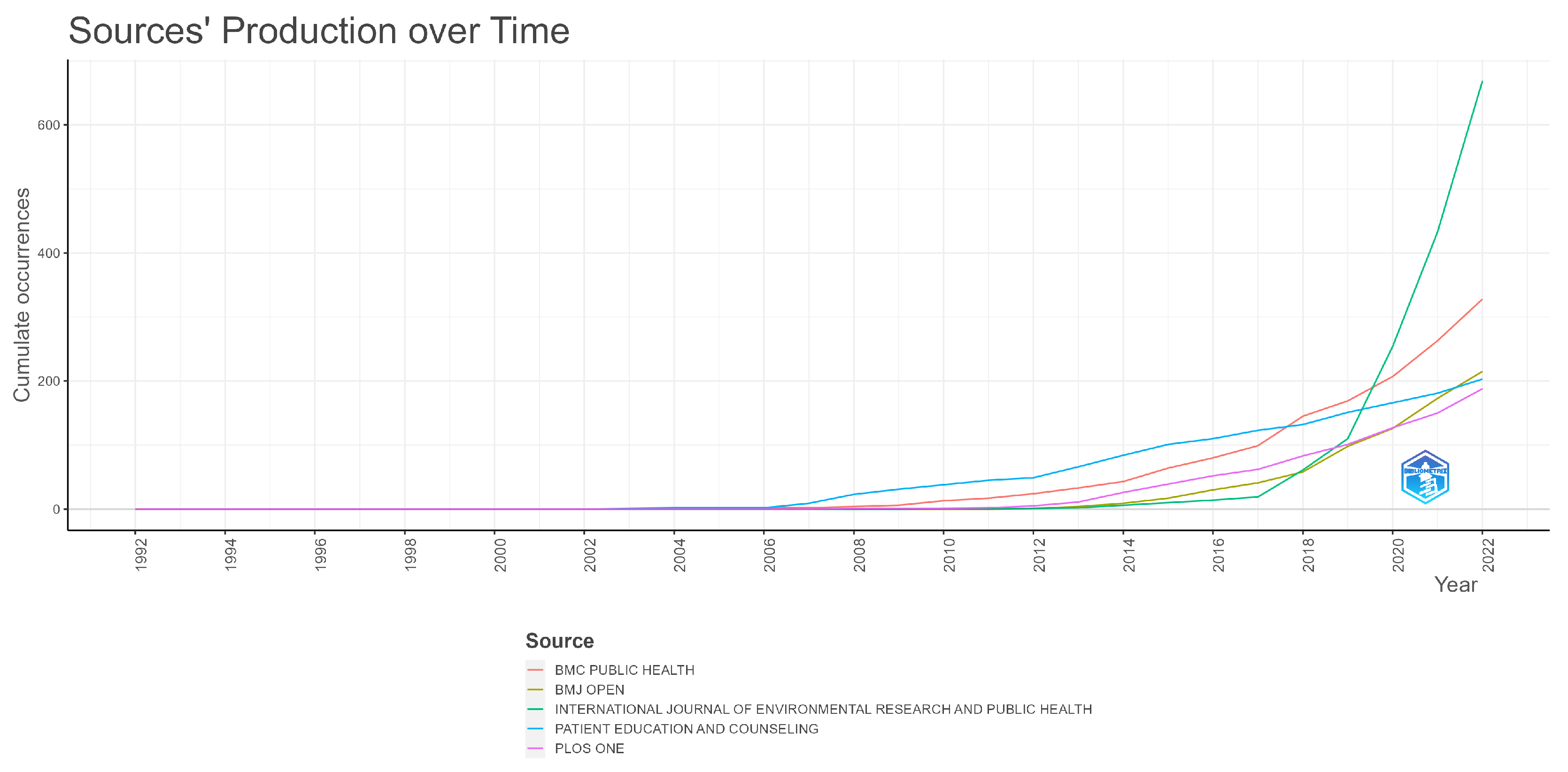

This expansion of research on the topic also co-occurs with a significant change in the dynamics of prominent journals. In

Figure 3, the sudden growth of the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health is clear from 2017 onward, reaching more than 500 articles published and being the most relevant source in the area by 2022. The Patient Education and Counseling was the most important source from 2006 to 2017 being surpassed by the BMC Public Health from 2018 to 2019, which was then surpassed by the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health in 2020. The International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health presented over 600 articles published in the topic by 2022. We can also see the recent growth in the case of BMJ Open, which surpassed both Plos One and the Patient Education and Counseling 2022. By 2022 the most important sources were, in descending order, the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, BMC Public Health, BMJ Open, Patient Education and Counseling and Plos One, with all of them, except for Plos One, having more than 200 articles on the theme.

3.3. Authors

We have used the functions of bibliometrix [

14,

15] to identify the most prolific and most cited authors in the field. We have also examined the distribution of the production of these authors throughout time.

For this section, author disambiguation was done manually as a way to prevent erroneous representation of authors with similar initials and surnames.

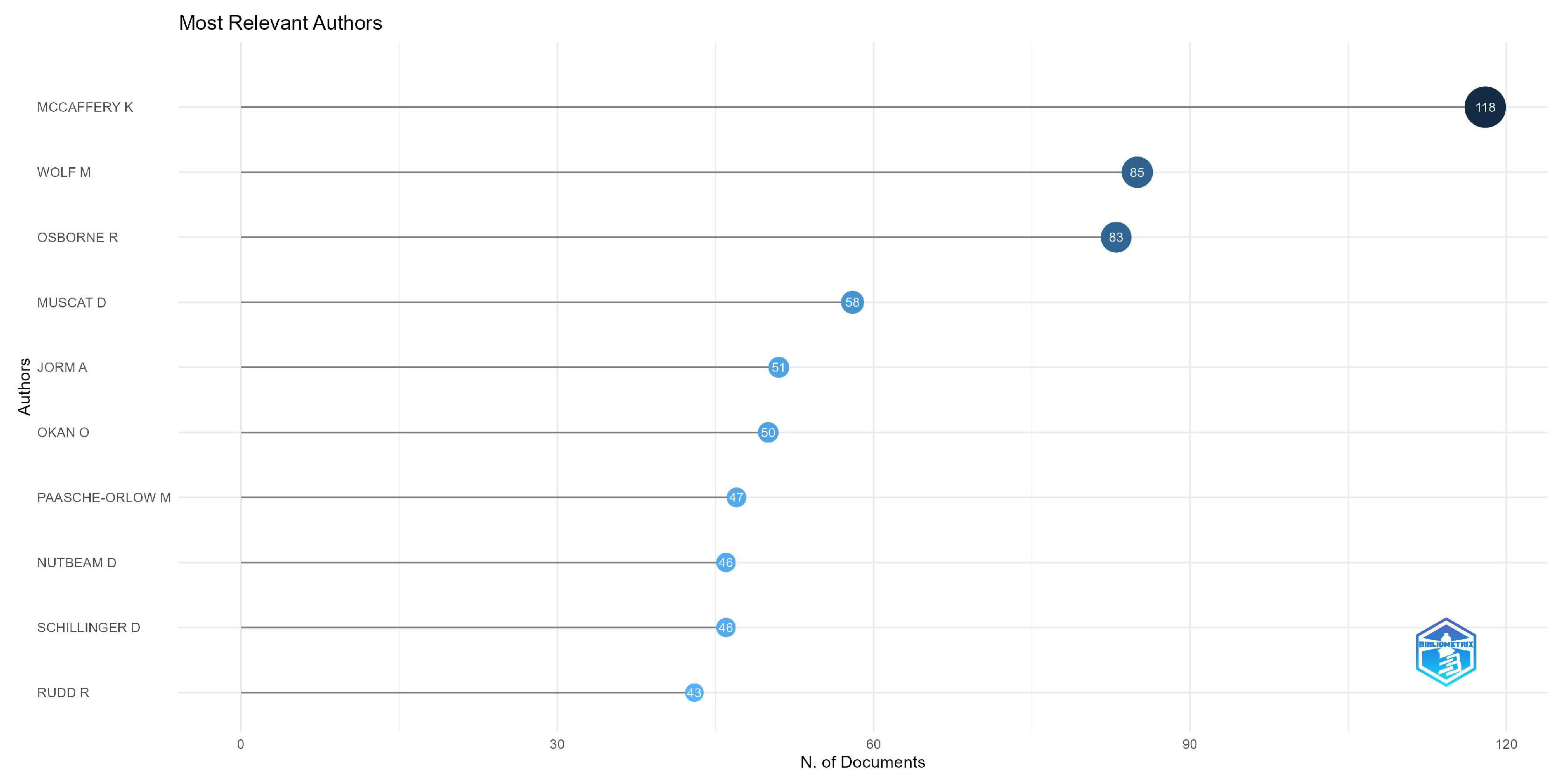

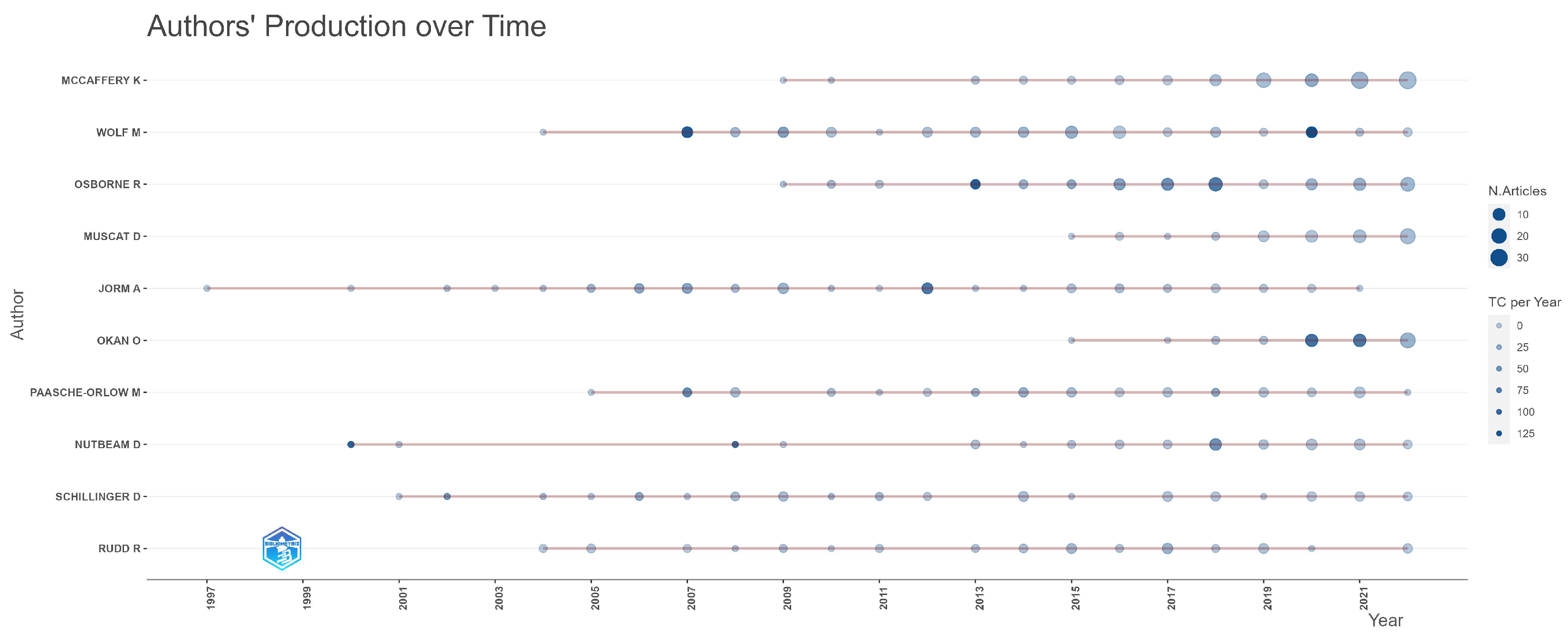

Regarding the authors researching the topic,

Figure 4 shows the most prolific authors. Here we can see the authors with the highest amount of publications in our corpus. All of those authors range from 118 to 39 articles.

The highest five are Kirsten McCaffery, Michael Wolf, Richard Osborne, Danielle Muscat, Anthony Jorm. Kirsten McCaffery is a prolific author discussing themes such as over diagnosis and patient empowerment [

29,

30,

31,

32,

33]. Michael Wolf is a researcher that focuses on health literacy and its impact in treatment adherence and decision making [

34,

35,

36,

37]. Richard Osborne is a researcher known for the development of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) [

25] and is active on several other empirical articles on health literacy [

38,

39,

40,

41]. Danielle Muscat is a researcher focused on health literacy and socially disadvantaged populations [

42,

43,

44]. Anthony Jorm is one of the precursors of the research on mental health literacy [

45,

46], discussing problems like stigma [

47] and being a reference on the development of instruments measuring mental health literacy such as the Mental Health Literacy Scale[

28].

In

Figure 5, we can see how the production of the most prolific authors has been distributed over time. From this figure, it is possible to see that all the authors were still active in 2022. The authors that have been publishing in this field the longest are Anthony Jorm, which started his publications on the theme by 1997, Don Nutbeam, which had his first publication on the area by 2000 and Dean Schillinger who published in 2001.

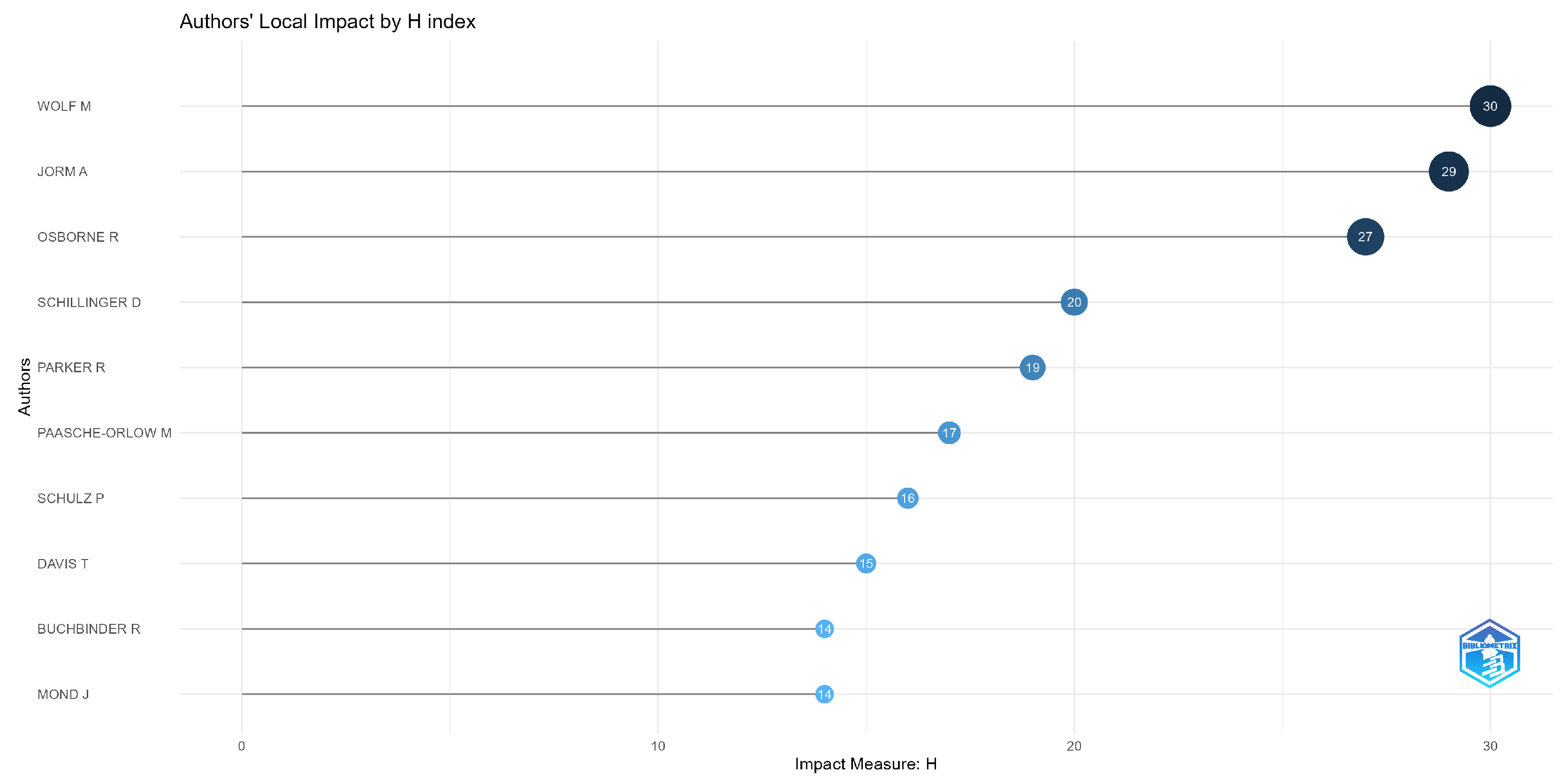

Another essential aspect we exhibit in

Figure 6 is the authors with the highest impact, as measured by their H index. Comparing

Figure 5 with

Figure 6 we can see that the authors with the highest h-index are also the ones that have started publishing on the theme for the longest time. The fact that Anthony Jorm, Dean Schillinger, Michael Wolf and Richard Osborne were the four authors with a higher h-index and were also the ones that have been producing articles on the theme for a longer amount of time, as shown in

Figure 5, indicate this correlation as a possible explanation.

A large portion of the authors in

Figure 6 and

Figure 4 are responsible for helping the development of health literacy assessment methodologies. Richard Osborne has took part in developing Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) to assess patient-reported outcomes related to health literacy [

48]. Michael Wolf has worked on the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) [

49,

50]. Orkan Okan focused on the adaptation of the European Health Literacy Survey (HLS-EU) to children [

51,

52,

53]. Anthony Jorm has focused on different tools to evaluate mental health literacy and dementia [

45,

54,

55].

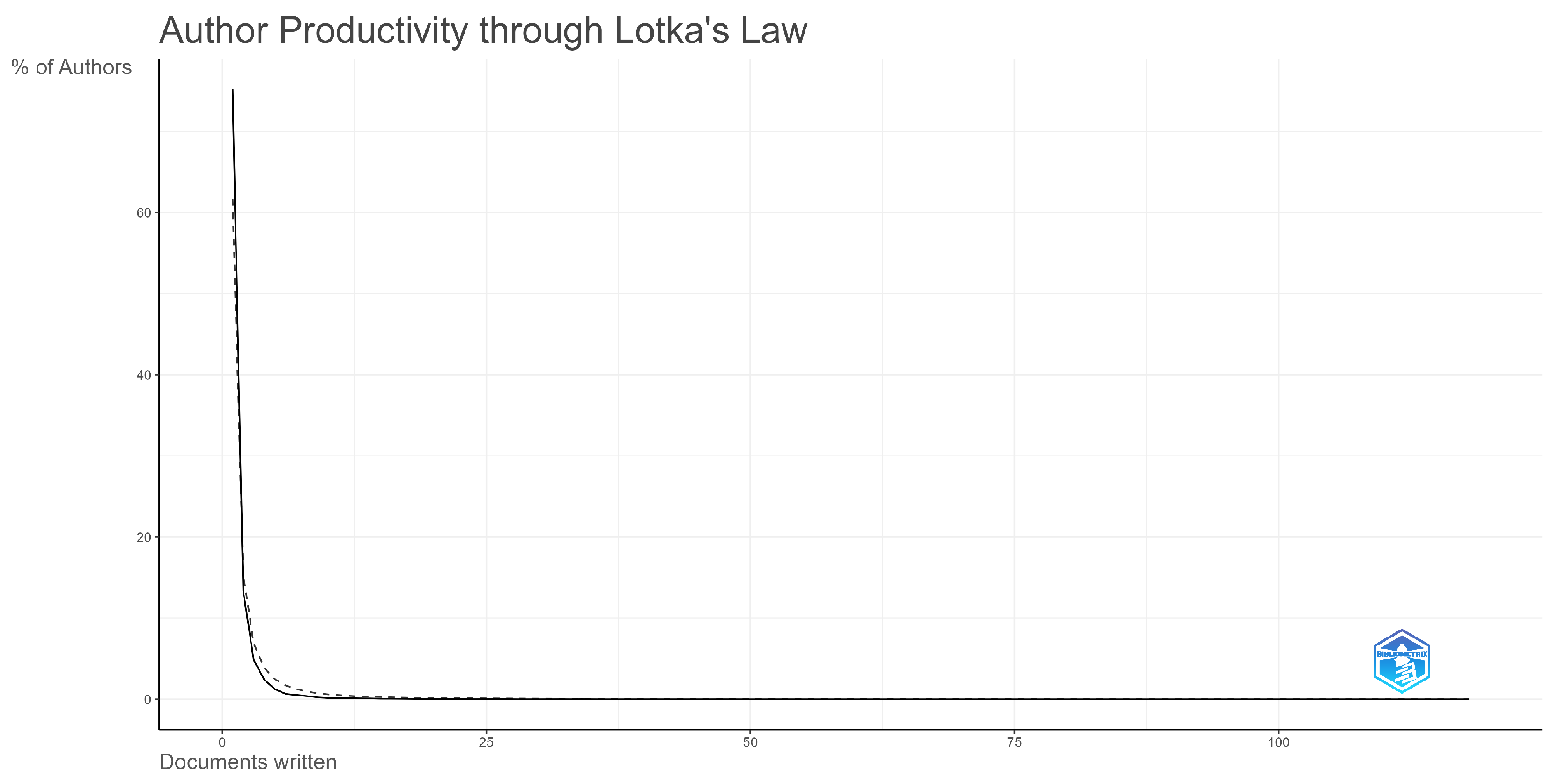

We have applied Lotka’s Law to evaluate how the amount of publications on health literacy is divided among authors. The graph illustrating the curve of Lotka’s Law can be seen in

Figure 7. The results show that 75.2 % of authors have published just one article on the theme, 13.4 % have published two articles 11.4 % have published three or more articles. This shows the few prolific authors on the theme of health literacy, with a majority of authors having few contributions.

3.4. Region

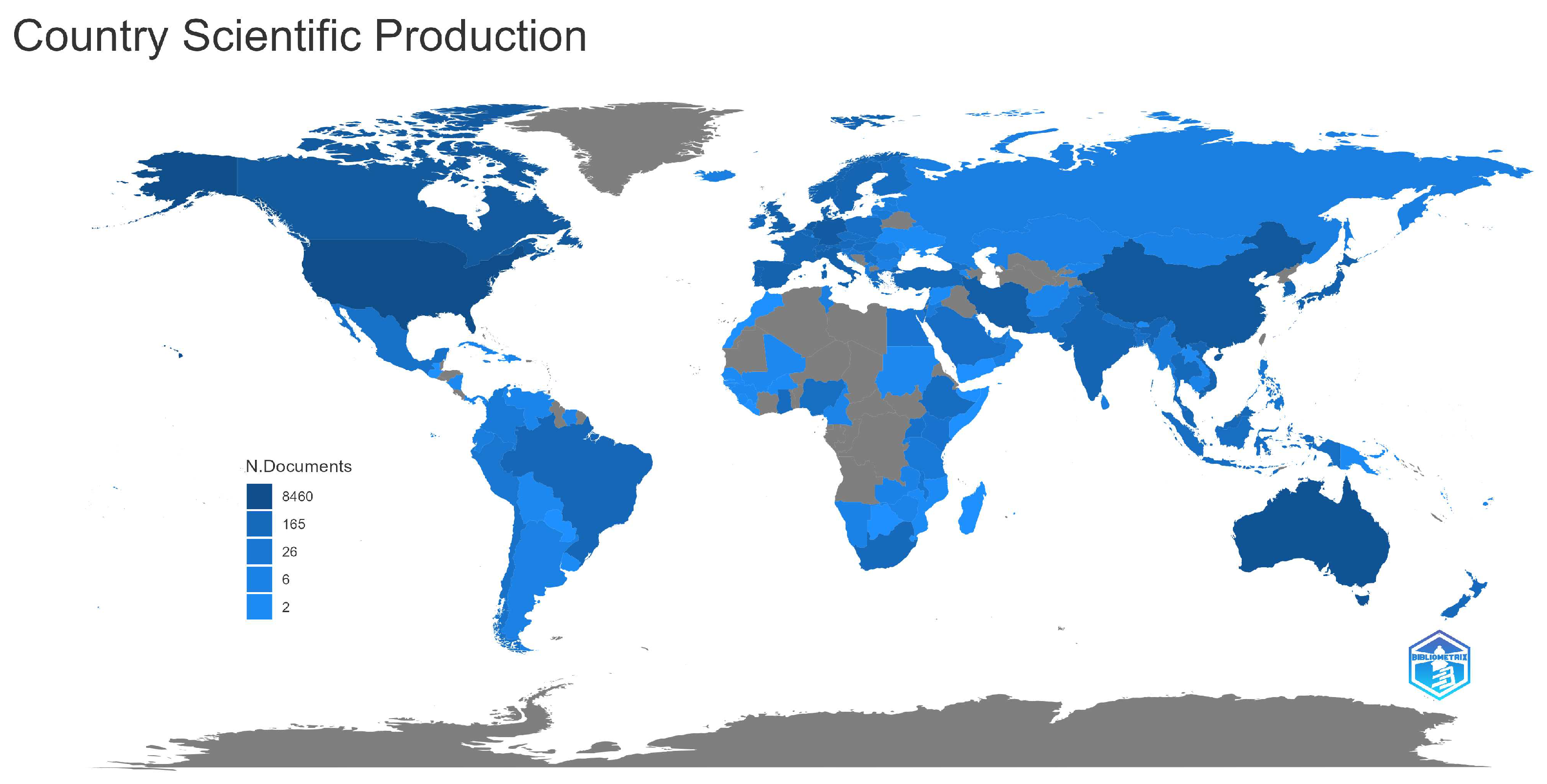

Another important aspect of the literature is the countries where the topic is being researched. Here we have mapped the countries of the corresponding author of each paper. It’s important to note that our corpus consists only of English articles, which reduces the amount of articles on countries where English is not the native language.

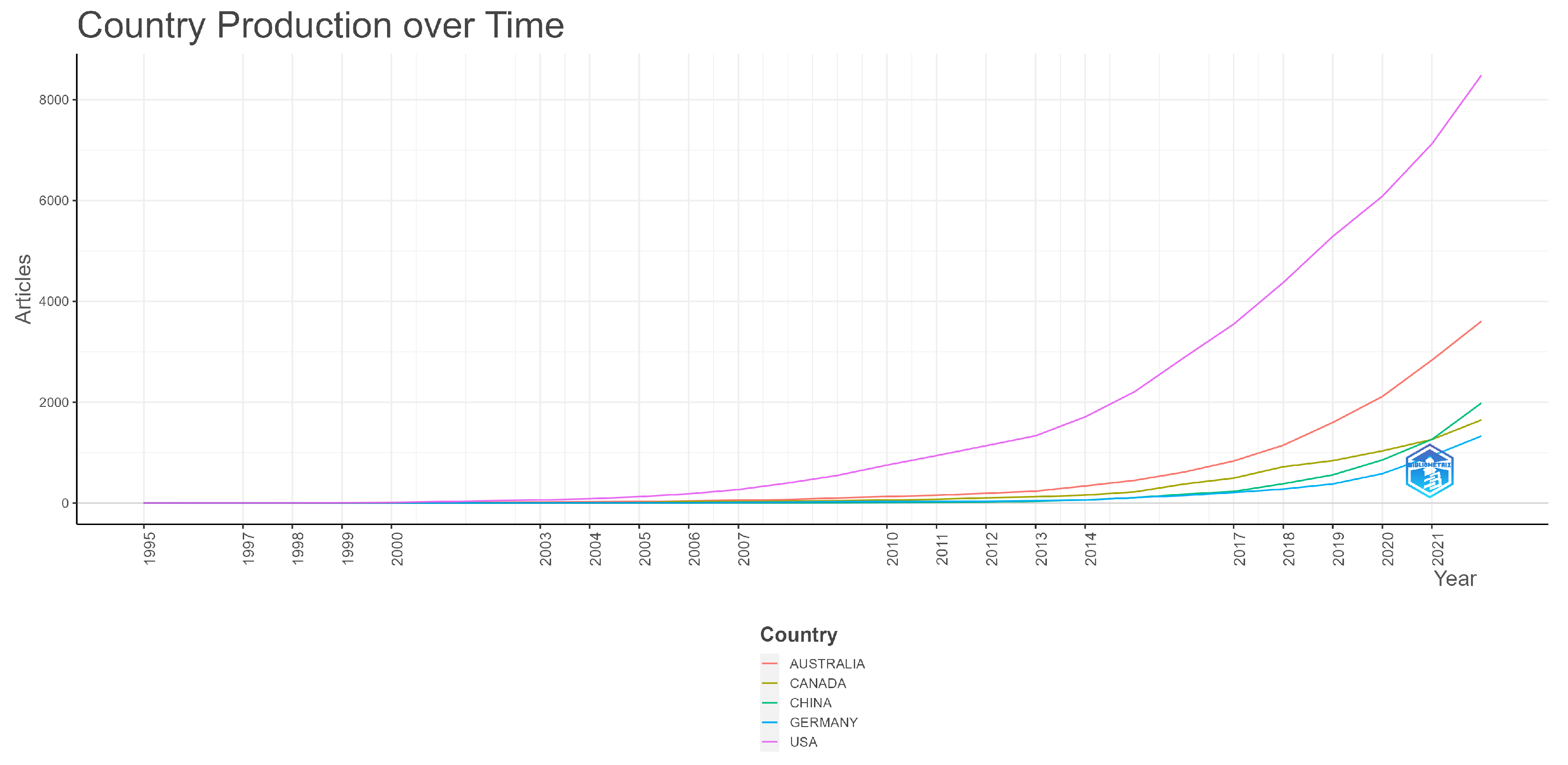

Figure 8 shows a map where each country with articles is shaded blue, the intensity of the color represents the amount of articles published by corresponding authors in that country. The countries with the most articles are the USA, China and Australia. In Europe the countries with most publications are the United Kingdom and Germany, in South America Brazil has the most articles, in Africa the most prolific country is South Africa.

On

Figure 9 the five countries with the highest amount of publications, the USA, Australia, China, Canada and Germany, are shown with the amount of articles by year. The USA is an outlier with more than 8400 articles published by 2022. Australia shows over 3500 articles by 2022, while China, Germany and the United Kingdom have under 1900. This shows how the production of scientific articles on theme is concentrated in a few specific prolific countries. Another aspect that can be seen is the recent growth of China, which became the third country with most articles in 2021.

3.5. Topics

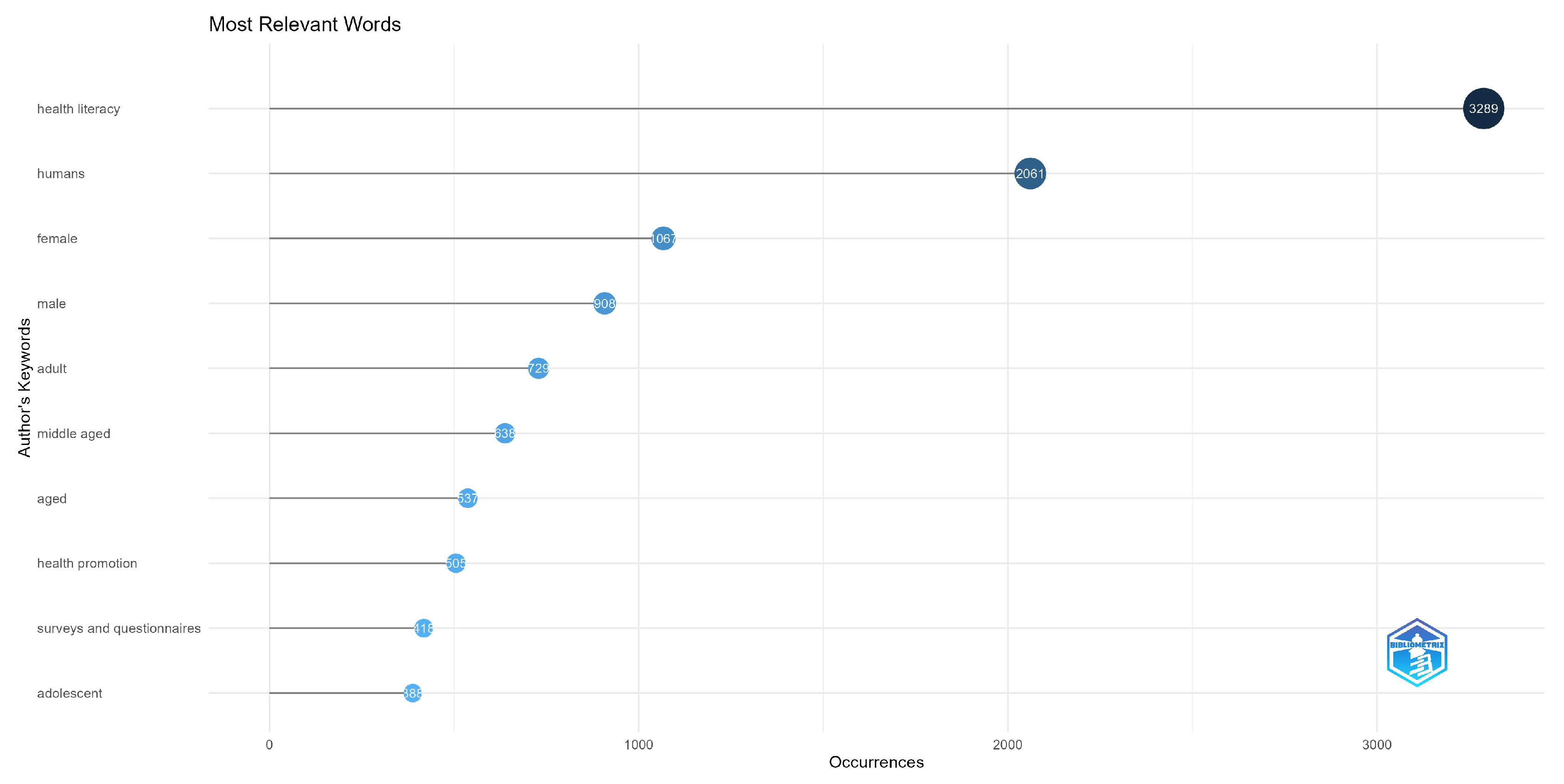

In order to evaluate the topics being studied by the authors, we have opted to analyze the author’s keywords. We present the most frequent keywords in

Figure 10. Here we can see mostly terms related to the groups being studied, such as Male or Female and Adult, Adolescent, Middle Aged and Aged. We can also see Surveys and Questionnaires, as those are the most common health literacy measuring tools.

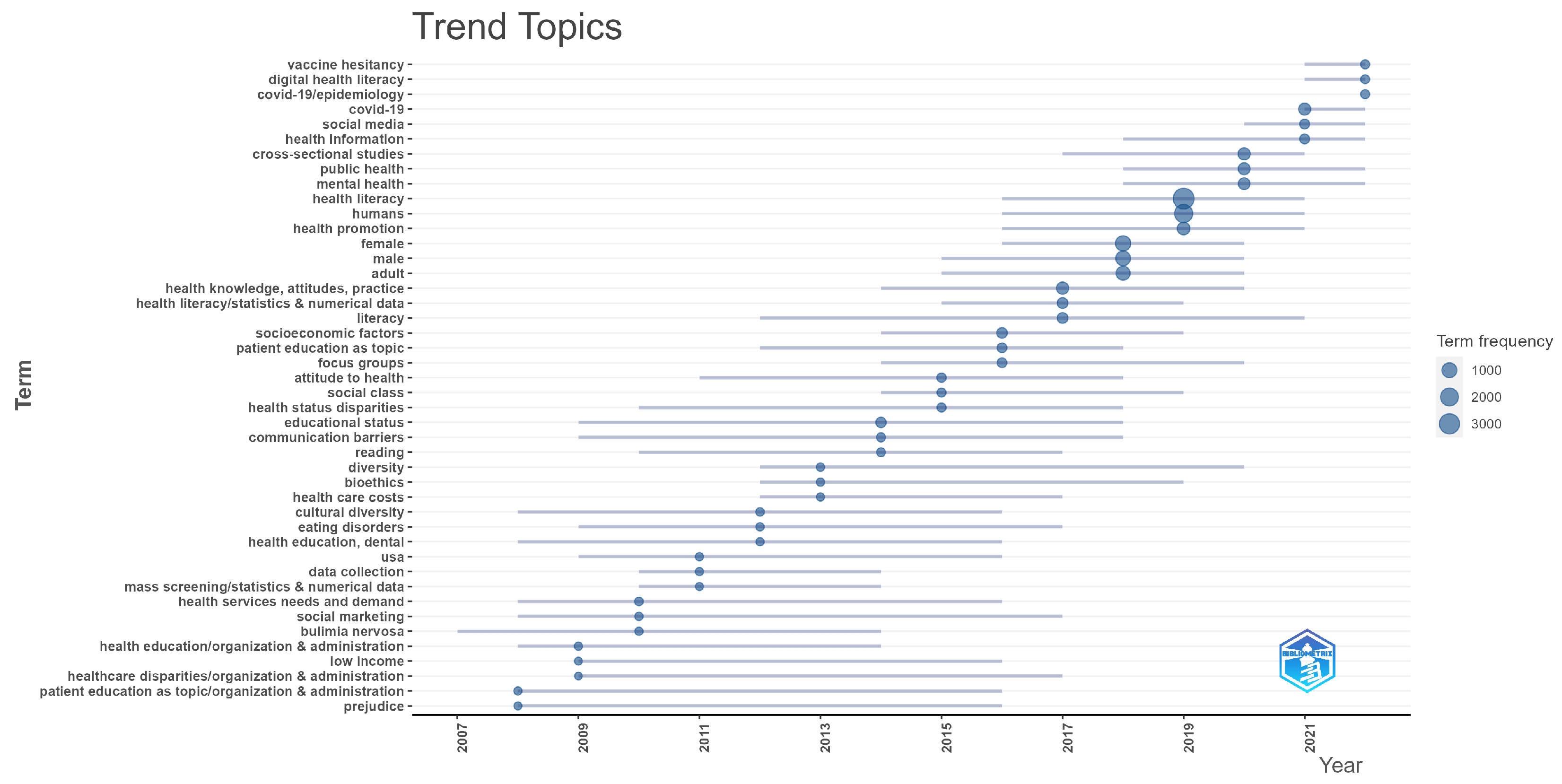

Figure 11, shows the time frame that each topic has been primarily addressed. Here it is possible to visualize recent topics such as Covid-19, Vaccine Hesitancy, Social Media, Digital Health Literacy and Mental Health Literacy arising. It is also possible to notice how some of the topics have started receiving less attention, such as those regarding organization and administration of health facilities.

Covid-19 and vaccination hesitancy are topics that have gained attention lately due to the pandemic and infodemic situation that increased vaccination hesitancy around the world[

56]. Another topic that relates to the pandemic and co-occurring infodemic are the ones of social media [

23,

57] and mental health [

58,

59,

60].

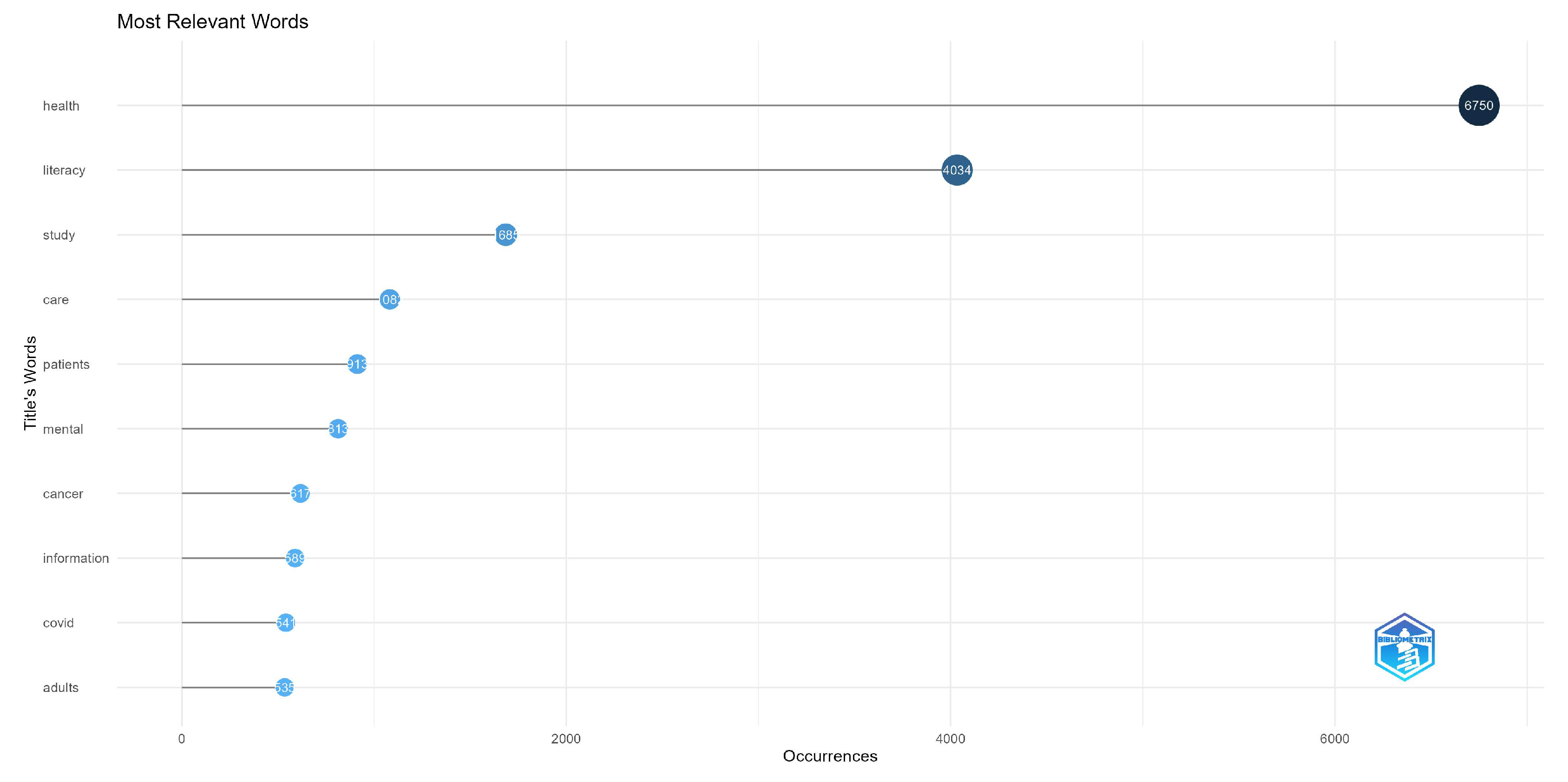

We have also opted to visualize the most frequent words used in the articles’ titles, analyzing them isolated from other adjacent terms (as unigrams). This is another way to look into most studied topic that might not have been indexed as keywords.

Figure 12 shows us some specific terms that indicate aspects being studied by health literacy researchers. Covid and Mental show here as well as on

Figure 11, indicating that while being more recent topics of study, they already show on a substantial amount of articles. Cancer also shows as a theme being present in many article titles, which goes in line to research showing that health literacy is important in order to promote cancer screening [

61] and adequate patient decision making and treatment comprehension, which can lead to better outcomes [

62].

4. Discussion

This research used the bibliometric analysis methods present in bibliometrix to look at the emerging trends and patterns in the scientific production regarding health literacy. Our analysis sets itself apart due to its use of the Random Forest technique to estimate the impact of keywords on average citations per year and the focus on public health.

Other studies using bibliometric methods have been made on health literacy but with different focuses such as the academic production on the theme of health education and health literacy [

63]. Or with regional emphasis, focusing on the studies done on the theme in Europe [

64] that also find a predominance of the USA on the theme by 2008 and decides to focus on the specificity of Europe. There is also the systematic review of the health literacy measurement instruments coupled with bibliometric techniques by [

65].

We have identified that health literacy as a field has grown with exceptional intensity in the last few years. The themes of COVID-19, mental health and social media are relevant to this expansion. Another evident aspect was the prominence of the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health in the latest years, similarly to what was found in the case of the field of health literacy and health education [

63].

These recent changes in the field, coupled with the fact that all of the most prolific authors are still active, show that this is a growing theme that is expanding and changing focus as time progresses. We have also found that, when looking at the authors with the highest H index, a number of those authors that have developed or adapted tools and methodologies for evaluating health literacy, which then were incorporated in other researches.

Using the Random Forest Model we have estimated, through the use of OLS regression exhibited in Eq.

1, we have shown that, as expected, the age of the article is relevant for its average citation per year. That the amount of authors is also relevant for that, with a positive relation to the citations. Another aspect that we have shown is that ’Covid-19’ has a significant impact in citations despite being a recent topic of study. We have also found a positive coefficient for the ’Male’ keyword and a negative one for the ’Female’ keyword, that indicates a possible bias in the literature. We have also found a positive coefficient for the ’Questionnaire’ and the ’Cross sectional study’ keywords, that indicates an interest in empirical studies.

The model we have used, however, does not take into account other important aspects. Our findings presented in

Figure 6 show that the authors involved in the creation and adaption of health literacy evaluation tools receive more citations. This serves to point that there are other qualitative variables that account for the citations per year that are not possible of being modelled.

Further studies can be made using different corpora, tailoring them for each corpus to encapsulate different dimensions of health literacy, be it the type of health literacy, such as functional, interactive or critical [

3,

4,

5], or specific themes, such as mental health literacy or digital health literacy [

28,

66]. Our research also indicated a possible gender bias in the literature, future research focusing on the gender divide in the literature is warranted in order to properly understand this issue.

5. Conclusions

The field of health literacy and public health has grown in the number of publications in the last two decades, with the bulk of its growth happening since 2015. However, we have also shown a change in the most studied topics. This is an ongoing change, and it remains to be seen how this field of study will grow with time if the new emerging themes and authors will become the most cited ones.

For the time being, the themes related to Covid-19 remain highly researched topics. We have also found a gender discrepancy in citation likelihood, with the keyword ’Female’ having a negative coefficient and the keyword ’Male’ having a positive one, which indicates a possible bias in the literature. Empirical studies with the keywords ’Questionnaire’ or ’Cross Sectional Studies’ have also shown a positive coefficient for annual citation.

We have also found a recent change in the most relevant journals on the theme, with the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health surging in the amount of articles published from 2018 onward, being in 2022 the most prolific journal in the literature. We have also seen a growth in production from China in the last decade, being the third most productive country, behind the USA and Australia. These changes, coupled with the new themes rising indicates that the literature is evolving, incorporating new topics with the entrance of new authors, reflecting the growth and diversification of the field.

This article provided a state of the art of the field of the intersection between health literacy and public health, and introduces a predictive model spotlighting the most pertinent keywords. This reflects the themes considered relevant by the literature and also offers potential guidelines for authors in the field. However, like all fields, how the observed dynamics and the immense impact of the Covid-19 pandemic will persist throughout time remains to be seen.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.M.T. and M.B.F.; methodology, B.M.T.; software, M.B.F.; validation, R.S.C. and T.C.S.; formal analysis, B.M.T. and T.C.S.; investigation, M.B.F.; data curation, M.B.F. and T.C.S.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.F.; writing—review and editing, B.M.T., M.B.F. and R.S.C.; visualization, M.B.F.; supervision, B.M.T.; project administration, B.M.T.; funding acquisition, B.M.T.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Financial support for this research was provided by Fundação de Apoio à Pesquisa do Distrito Federal (FAP-DF). All the authors acknowledge FAP-DF for their financial support through the Project "Um diagnóstico da Educação em Saúde no Distrito Federal" (Process No. 33435.154.29827.20102022).

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are publicly available on Scopus and Web of Science and can be made available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. What is Health Literacy, 2022. Accessed on March 18, 2023.

- Berkman, N.D.; Sheridan, S.L.; Donahue, K.E.; Halpern, D.J.; Viera, A.; Crotty, K.; Holland, A.; Brasure, M.; Lohr, K.N.; Harden, E.; Tant, E.; Wallace, I.; Viswanathan, M. Health literacy interventions and outcomes: an updated systematic review. Evidence report/technology assessment 2011, p. 1 – 941. Cited by: 454.

- Chinn, D. Critical health literacy: A review and critical analysis. Social science & medicine 2011, 73, 60–67. [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam, D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Social science & medicine 2008, 67, 2072–2078. [Google Scholar]

- Nutbeam, D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health promotion international 2000, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindig, D.A.; Panzer, A.M.; Nielsen-Bohlman, L. ; others. Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion 2004.

- Bostock, S.; Steptoe, A. Association between low functional health literacy and mortality in older adults: longitudinal cohort study. Bmj 2012, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, S.E.; Sadikova, E.; Jack, B.W.; Paasche-Orlow, M.K. Health literacy and 30-day postdischarge hospital utilization. Journal of health communication 2012, 17, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlands, G. Health literacy: Ways to maximise the impact and effectiveness of vaccination information. Human vaccines & immunotherapeutics 2014, 10, 2130–2135. [Google Scholar]

- Sarto, F.; Cuccurullo, C.; Aria, M. Exploring healthcare governance literature: systematic review and paths for future research. In Exploring healthcare governance literature: systematic review and paths for future research; 2014; pp. 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards, M.; Wood, F.; Davies, M.; Edwards, A. ‘Distributed health literacy’: longitudinal qualitative analysis of the roles of health literacy mediators and social networks of people living with a long-term health condition. Health Expectations 2015, 18, 1180–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diviani, N.; Schulz, P.J. What should laypersons know about cancer? Towards an operational definition of cancer literacy. Patient education and counseling 2011, 85, 487–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aharon, A.A.; Nehama, H.; Rishpon, S.; Baron-Epel, O. Parents with high levels of communicative and critical health literacy are less likely to vaccinate their children. Patient education and counseling 2017, 100, 768–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M.; Cuccurullo, C. bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of informetrics 2017, 11, 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuccurullo, C.; Aria, M.; Sarto, F. Foundations and trends in performance management. A twenty-five years bibliometric analysis in business and public administration domains. Scientometrics 2016, 108, 595–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabak, B.M.; Silva, T.C.; Fiche, M.E.; Braz, T. Citation likelihood analysis of the interbank financial networks literature: A machine learning and bibliometric approach. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications 2021, 562, 125363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotka, A.J. The frequency distribution of scientific productivity. Journal of the Washington academy of sciences 1926, 16, 317–323. [Google Scholar]

- Association, A.M.; others. Ad Hoc Committee on Health Literacy for the Council on Scientific Affairs. Health literacy: Report of the council on scientific affairs. Journal of the American Medical Association 1999, 281, 552–557. [Google Scholar]

- Chai, T.; Draxler, R.R. Root mean square error (RMSE) or mean absolute error (MAE). Geoscientific model development discussions 2014, 7, 1525–1534. [Google Scholar]

- Hyndman, R.J.; Koehler, A.B. Another look at measures of forecast accuracy. International journal of forecasting 2006, 22, 679–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO, W.H.O. Understanding the infodemic and misinformation in the fight against COVID-19. Pan Am Health Organ 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zarocostas, J. How to fight an infodemic. The lancet 2020, 395, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.C.; Huy, L.D.; Lin, C.Y.; Lai, C.F.; Nguyen, N.T.H.; Hoang, N.Y.; Nguyen, T.T.P.; Dang, L.T.; Truong, N.L.T.; Phan, T.N.; Duong, T.V. Association of Digital Health Literacy with Future Anxiety as Meditated by Information Satisfaction and Fear of COVID-19: A Pathway Analysis among Taiwanese Students. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 15617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, M.; Quattrociocchi, W.; Galeazzi, A.; Valensise, C.M.; Brugnoli, E.; Schmidt, A.L.; Zola, P.; Zollo, F.; Scala, A. The COVID-19 social media infodemic. Scientific reports 2020, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osborne, R.H.; Batterham, R.W.; Elsworth, G.R.; Hawkins, M.; Buchbinder, R. The grounded psychometric development and initial validation of the Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ). BMC public health 2013, 13, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelikan, J.M.; Röthlin, F.; Ganahl, K.; Boltzmann, L. Measuring comprehensive health literacy in general populations: validation of instrument, indices and scales of the HLS-EU study. Proceedings of the 6th Annual Health Literacy Research Conference, 2014, pp. 4–6.

- Pelikan, J.M.; Ganahl, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Sørensen, K. Measuring health literacy in Europe: introducing the European health literacy survey questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q). In International handbook of health literacy; Policy Press, 2019; pp. 115–138.

- O’Connor, M.; Casey, L. The Mental Health Literacy Scale (MHLS): A new scale-based measure of mental health literacy. Psychiatry research 2015, 229, 511–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.K.; Dixon, A.; Trevena, L.; Nutbeam, D.; McCaffery, K.J. Exploring patient involvement in healthcare decision making across different education and functional health literacy groups. Social science & medicine 2009, 69, 1805–1812. [Google Scholar]

- Entwistle, V.A.; Carter, S.M.; Cribb, A.; McCaffery, K. Supporting patient autonomy: the importance of clinician-patient relationships. Journal of general internal medicine 2010, 25, 741–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCaffery, K.J.; Holmes-Rovner, M.; Smith, S.K.; Rovner, D.; Nutbeam, D.; Clayman, M.L.; Kelly-Blake, K.; Wolf, M.S.; Sheridan, S.L. Addressing health literacy in patient decision aids. BMC medical informatics and decision making 2013, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, T.C.; Legare, F.; Simmons, M.B.; McNamara, K.; McCaffery, K.; Trevena, L.J.; Hudson, B.; Glasziou, P.P.; Del Mar, C.B. Shared decision making: what do clinicians need to know and why should they bother? Medical Journal of Australia 2014, 201, 35–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCaffery, K.J.; Ayre, J.; Dodd, R.; Pickles, K.; Copp, T.; Muscat, D.M.; Nickel, B.; Cvejic, E.; Zhang, M.; Mac, O. others. Disparities in public understanding, attitudes, and intentions during the Covid-19 pandemic: The role of health literacy. Information Services & Use 2023, pp. 1–13.

- Paasche-Orlow, M.K.; Wolf, M.S. The causal pathways linking health literacy to health outcomes. American journal of health behavior 2007, 31, S19–S26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.W.; Wolf, M.S.; Feinglass, J.; Thompson, J.A.; Gazmararian, J.A.; Huang, J. Health literacy and mortality among elderly persons. Archives of internal medicine 2007, 167, 1503–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, M.S.; Gazmararian, J.A.; Baker, D.W. Health literacy and functional health status among older adults. Archives of internal medicine 2005, 165, 1946–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.C.; Wolf, M.S.; Bass III, P.F.; Thompson, J.A.; Tilson, H.H.; Neuberger, M.; Parker, R.M. Literacy and misunderstanding prescription drug labels. Annals of internal medicine 2006, 145, 887–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batterham, R.W.; Hawkins, M.; Collins, P.; Buchbinder, R.; Osborne, R.H. Health literacy: applying current concepts to improve health services and reduce health inequalities. Public health 2016, 132, 3–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, J.E.; Buchbinder, R.; Osborne, R.H. Conceptualising health literacy from the patient perspective. Patient education and counseling 2010, 79, 36–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sørensen, K.; Van den Broucke, S.; Pelikan, J.M.; Fullam, J.; Doyle, G.; Slonska, Z.; Kondilis, B.; Stoffels, V.; Osborne, R.H.; Brand, H. Measuring health literacy in populations: illuminating the design and development process of the European Health Literacy Survey Questionnaire (HLS-EU-Q). BMC public health 2013, 13, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batterham, R.W.; Buchbinder, R.; Beauchamp, A.; Dodson, S.; Elsworth, G.R.; Osborne, R.H. The OPtimising HEalth LIterAcy (Ophelia) process: study protocol for using health literacy profiling and community engagement to create and implement health reform. BMC public health 2014, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, R.W.; Smith, J.; Engel, J.; Muscat, D.M.; Smith, S.K.; Mancini, J.; Perestelo-Pérez, L.; Elwyn, G.; O’malley, A.J.; Leyenaar, J.K.; others. A systematic review and meta-analysis of patient decision aids for socially disadvantaged populations: update from the International Patient Decision Aid Standards (IDPAS). Medical Decision Making 2021, 41, 870–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muscat, D.M.; Ayre, J.; Mac, O.; Batcup, C.; Cvejic, E.; Pickles, K.; Dolan, H.; Bonner, C.; Mouwad, D.; Zachariah, D.; others. Psychological, social and financial impacts of COVID-19 on culturally and linguistically diverse communities in Sydney, Australia. BMJ open 2022, 12, e058323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nutbeam, D.; Muscat, D.M. Health promotion glossary 2021. Health Promotion International 2021, 36, 1578–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorm, A.F.; Korten, A.E.; Jacomb, P.A.; Christensen, H.; Rodgers, B.; Pollitt, P. “Mental health literacy”: a survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Medical journal of Australia 1997, 166, 182–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F. Mental health literacy: Public knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry 2000, 177, 396–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, L.J.; Griffiths, K.M.; Jorm, A.F.; Christensen, H. Stigma about depression and its impact on help-seeking intentions. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 2006, 40, 51–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, M.; Gill, S.D.; Batterham, R.; Elsworth, G.R.; Osborne, R.H. The Health Literacy Questionnaire (HLQ) at the patient-clinician interface: a qualitative study of what patients and clinicians mean by their HLQ scores. BMC health services research 2017, 17, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, T.C.; Wolf, M.S.; Arnold, C.L.; Byrd, R.S.; Long, S.W.; Springer, T.; Kennen, E.; Bocchini, J.A. Development and validation of the Rapid Estimate of Adolescent Literacy in Medicine (REALM-Teen): a tool to screen adolescents for below-grade reading in health care settings. Pediatrics 2006, 118, e1707–e1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arozullah, A.M.; Yarnold, P.R.; Bennett, C.L.; Soltysik, R.C.; Wolf, M.S.; Ferreira, R.M.; Lee, S.Y.D.; Costello, S.; Shakir, A.; Denwood, C. others. Development and validation of a short-form, rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine. Medical care 2007, pp. 1026–1033.

- Bollweg, T.M.; Okan, O.; Pinheiro, P.; Bauer, U. Development of a health literacy measurement tool for primary school children in Germany: Torsten Michael Bollweg. The European Journal of Public Health 2016, 26, ckw165–069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollweg, T.M.; Okan, O.; Bröder, J.; Bauer, U.; Pinheiro, P. Adapting the HLS-EU questionnaire for children aged 9 to 10: Exploring factorial validity. European Journal of Public Health 2018, 28, cky213–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broeder, J.; Okan, O.; Bauer, U.; Pinheiro, P. Health literacy in children–towards a child-centered conceptual understandingJanine Broeder. European Journal of Public Health 2017, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A. A short form of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): development and cross-validation. Psychological medicine 1994, 24, 145–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jorm, A.F. The Informant Questionnaire on cognitive decline in the elderly (IQCODE): a review. International psychogeriatrics 2004, 16, 275–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruiz, J.B.; Bell, R.A. Predictors of intention to vaccinate against COVID-19: Results of a nationwide survey. Vaccine 2021, 39, 1080–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, Z.; Liu, W.; Yang, L.; Sun, N.; Lu, Y.; Chen, H. Group Differences: The Relationship between Social Media Use and Depression during the Outbreak of COVID-19 in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 13941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Yépez, P.J.; Muñoz-Pino, C.O.; Ayala-Laurel, V.; Contreras-Carmona, P.J.; Inga-Berrospi, F.; Vera-Ponce, V.J.; Failoc-Rojas, V.E.; Pereira-Victorio, C.J.; Valladares-Garrido, M.J. Factors Associated with Anxiety, Depression, and Stress in Peruvian University Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 14591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griggs, S.; Horvat Davey, C.; Howard, Q.; Pignatiello, G.; Duwadi, D. Socioeconomic Deprivation, Sleep Duration, and Mental Health during the First Year of the COVID-19 Pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 14367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loezar-Hernández, M.; Briones-Vozmediano, E.; Ronda-Pérez, E.; Otero-García, L. Juggling during Lockdown: Balancing Telework and Family Life in Pandemic Times and Its Perceived Consequences for the Health and Wellbeing of Working Women. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2023, 20, 4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koirala, R.; Gurung, N.; Dhakal, S.; Karki, S. Role of cancer literacy in cancer screening behaviour among adults of Kaski district, Nepal. Plos one 2021, 16, e0254565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holden, C.E.; Wheelwright, S.; Harle, A.; Wagland, R. The role of health literacy in cancer care: a mixed studies systematic review. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0259815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selva-Pareja, L.; Ramos-Pla, A.; Mercadé-Melé, P.; Espart, A. Evolution of scientific production on health literacy and health education—a bibliometric analysis. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2022, 19, 4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kondilis, B.K.; Kiriaze, I.J.; Athanasoulia, A.P.; Falagas, M.E. Mapping health literacy research in the European Union: a bibliometric analysis. PloS one 2008, 3, e2519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavousi, M.; Mohammadi, S.; Sadighi, J.; Zarei, F.; Kermani, R.M.; Rostami, R.; Montazeri, A. Measuring health literacy: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis of instruments from 1993 to 2021. PloS one 2022, 17, e0271524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norman, C.D.; Skinner, H.A. eHEALS: the eHealth literacy scale. Journal of medical Internet research 2006, 8, e507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).