Submitted:

08 September 2023

Posted:

11 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Group and Equipment

2.2. Research Process

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Łukaszewicz, A.; Szafran, K.; Jóźwik, J. CAx Techniques Used in UAV Design Process. In Proceedings of the 7th IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for AeroSpace, MetroAeroSpace 2020; pp. 95–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vasić, Z.; Maksimović, S.; Georgijević, D. Applied Integrated Design in Composite UAV Development. Appl. Composite Mater. 2018, 25(2), 221–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šančić, T.; Brčić, M.; Kotarski, D.; Łukaszewicz, A. Experimental Characterization of Composite-Printed Materials for the Production of Multirotor UAV Airframe Parts. Materials 2023, 16, 5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carneiro, P.M.C.; Gamboa, P. Structural Analysis of Wing Ribs Obtained by Additive Manufacturing. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2019, 25(4), 708–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohsan, S.A.H.; Khan, M.A.; Noor, F.; Ullah, I.; Alsharif, M.H. Towards the Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): A Comprehensive Review. Drones 2022, 6, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartley, R.J.a.L.; Henderson, I.L.; Jackson, C.L. BVLOS Unmanned Aircraft Operations in Forest Environments. Drones 2022, 6, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marian, V. G. The Use of Drones in Mining Operations. Mining Revue. 2022, 28(3), 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Aguilera, D.; Rodriguez-Gonzalvez, P. Drones—An Open Access Journal. Drones 2017, 1, 1. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/drones1010001 (accessed July 31 2023).

- Ewane, E.B.; Mohan, M.; Bajaj, S.; Galgamuwa, G.A.P.; Watt, M.S.; Arachchige, P.P.; Hudak, A.T.; Richardson, G.; Ajithkumar, N.; Srinivasan, S.; et al. Climate-Change-Driven Droughts and Tree Mortality: Assessing the Potential of UAV-Derived Early Warning Metrics. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazzo, C.O.G.; Kamali, B.; Hütt, C.; Bareth, G.; Gaiser, T. A Review of Estimation Methods for Aboveground Biomass in Grasslands Using UAV. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 639 Available from:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieloszyk, J.; Tarnowski, A.; Kowalik, M.; Perz, R.; Rzadkowski, W. Preliminary Design of 3D Printed Fittings for UAV. Aircraft Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 2019, 91(5), 756–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darowska, M.; Kutwa, K. Biała Księga Rynku Bezzałogowych Statków Powietrznych: U-SPACE – RYNEK – WIZJA ROZWOJU; Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny: Warsaw, 2019; ISBN 978-83-61284-74-1. [Google Scholar]

- Nishith Desai Associates. The Global Drone Revolution: Aerial Transport, Agritech, Commerce & Allied Opportunities; Nishith Desai Associates: Mumbai, India, 2021; pp. 4–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.-H.J.; Deng, C.; Low, K.H. Parametric Study of Structured UTM Separation Recommendations with Physics-Based Monte Carlo Distribution for Collision Risk Model. Drones 2023, 7, 345 Available from:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deskiewicz, A.; Perz, R. Agricultural Aircraft Wing Slat Tolerance for Bird Strike. Aircraft Eng. Aerosp. Technol. 2017, 89, 590–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jastrzębski, D.; Perz, R. Rib Kinematics Analysis in Oblique and Lateral Impact Tests. Acta Bioeng. Biomech. 2020, 22 (1), pp 1-9. [CrossRef]

- Góra, K.; Smyczyński, P.; Kujawiński, M.; Granosik, G. Machine Learning in Creating Energy Consumption Model for UAV. Energies 2022, 15(18), 6810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szafran, K.; Łukaszewicz, A. Flight Safety - Some Aspects of the Impact of the Human Factor in the Process of Landing on the Basis of a Subjective Analysis. In Proceedings of the 7th IEEE International Workshop on Metrology for AeroSpace, MetroAeroSpace 2020; pp. 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weldon, W. T.; Hupy, J.; Lercel, D.; Gould, K. The Use of Aviation Safety Practices in UAS Operations: A Review. Collegiate Aviation Rev. Int. 2021, 39 (1), Available from: https://ojs.library.okstate.edu/osu/index.php/CARI/article/view/8214/7544 (accessed July 31, 2023).

- Fan, B.; Li, Y.; Zhang, R.; Fu, Q. Review on the Technological Development and Application of UAV Systems. Chin. J. Electron. 2020, 29 (2). [CrossRef]

- Özyörük, H. E. The Effects of Human Factors on Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) Operator Performance. Hava Ulaştırma Fakültesi Havacılık Seminerleri / Faculty of Air Transportation Aviation Seminars, August 13, 2020. Available from: https://flt.thk.edu.tr/storage/public/documents/tiny/48/THE-EFFECTS-OF-HUMAN-FACTORS-ON-UNMANNED-AERIAL-VEHICLE-UAV-OPERATOR-P.._.pdf. (accessed July 31, 2023).

- Lin, Z.; Castano, L.; Mortimer, E.; Xu, H. Fast 3D Collision Avoidance Algorithm for Fixed Wing UAS. J. Intell. Robot. Syst. 2020, 97, 577–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balestrieri, E.; Daponte, P.; De Vito, L.; Picariello, F.; Tudosa, I. Sensors and Measurements for UAV Safety: An Overview. Sensors 2021, 21(24), 8253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, W.; Li, X.; Hu, J.; Song, X.; Dong, X.; Kong, D. . & Ren, C. A Rear Anti-Collision Decision-Making Methodology Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning for Autonomous Commercial Vehicles. IEEE Sensors J. 2022, 22(16), 16370–16380. [Google Scholar]

- Marzec, D.; Fellner, R. Influence of Human Factor on the Safety Flights of Unmanned Aircraft. Aircraft. Soc. Educ. 2018, 29, 397–411. [Google Scholar]

- Modell, J. G.; Mountz, J. M. Drinking and flying--the problem of alcohol use by pilots. N. Engl. J. Med. 1990, 323(7), 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, K. W.; Gildea, K. M. A Review of Research Related to Unmanned Aircraft System Visual Observers; Report, No. DOT/FAA/AM-14/9; Civil Aerospace Medical Institute, Federal Aviation Administration: Oklahoma City, OK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.W.; Sun, C.; Li, N. Distance and Visual Angle of Line-of-Sight of a Small Drone. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 5501 Available from:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chappelle, W. L.; McDonald, K. D.; Prince, L.; Goodman, T.; Ray-Sannerud, B. N.; Thompson, W. Symptoms of Psychological Distress and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in United States Air Force "Drone" Operators. Mil. Med. 2014, 179 (8 Suppl), 63–70. Available from: https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00501 (accessed July 31 2023).

- Ažaltovič, V.; Škvareková, I.; Pecho, P.; Kandera, B. Measurement Methodology of Hypoglycemia and Alcohol Effect on UAV Piloting Accuracy. In Proceedings of the 2020 New Trends in Aviation Development (NTAD), Starý Smokovec, Slovakia; 2020; pp. 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novák, A.; Mrazova, M. Research of Physiological Factors Affecting Pilot Performance in Flight Simulation Training Device. Commun. Sci. Lett. Univ. Zilina 2015, 17, 103–107 Available from:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Škvareková, I.; Ažaltovič, V.; Pecho, P.; Bielik, M.; Kandera, B. The Impact of Somatic Stressors on Pilot. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Air Transport – INAIR 2019 Global Trends in Aviation, Location of Conference, Country; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Bąk, J.; Bąk – Gajda, D. Psychologiczne Aspekty Kierowania Pojazdem Pod Wpływem Alkoholu. Autobusy 2010, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Vrábel, J.; Sarkan, B.; Vashisth, A. Change of Driver's Reaction Time Depending on the Amount of Alcohol Consumed by the Driver - The Case Study. Arch. Automot. Eng. – Archiwum Motoryzacji 2020, 87, 47–56 Available from:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniyam, M.; Kim, S.; Min, S.; Lee, H.; Hong, S.; Park, S.J. Study of Effects of Blood Alcohol Consumption (BAC) Level on Drivers Physiological Behavior and Driving Performance Under Simulated Environment. Int. J. Eng. Technol. 2018, 7, 86 Available from:. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Hess, D. J.; Heldeweg, M. A. Safety and Privacy Regulations for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: A Multiple Comparative Analysis. Technol. Soc. 2022, 71, 102079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yershov, V. Regulations of the Drones Flows in Ukraine. In Modern Movement of Science: Abstracts of the 10th International Scientific and Practical Internet Conference WayScience, April 2-3, 2020; Flight Academy of NAU: Dnipro, 2020; Vol. 1, p 811. Available from: http://dspace.puet.edu.ua/bitstream/123456789/8831/1/1_%D0%B7%D0%B1%D1%96%D1%80%D0%BD%D0%B8%D0%BA%20%D0%BA%D0%B2%D1%96%D1%82%D0%B5%D0%BD%D1%8C%202020.pdf#page=435 (accessed on July 31 2023).

- Dissanayake, M.; Kulasekara, R. Drone Technology in Sri Lanka: Urgency for an Effective Legal Framework. In Proceedings of the 12th International Research Conference, General Sir John Kotelawala Defence University: Sri Lanka, 2019; pp 740. Available from: http://ir.kdu.ac.lk/bitstream/handle/345/2076/law003.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y (accessed on July 31 2023).

- European Commission. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/947 of 24 May 2019 on the rules and procedures for the operation of unmanned aircraft (Text with EEA relevance); Official Journal L 152: European Commission, 2019; pp 45–71. Available from: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg_impl/2019/947/oj (accessed June 13, 2023).

- Mavic 2 Pro/Zoom User Manual v1.4, access on https://dl.djicdn.com/downloads/Mavic_2/Mavic+2+Pro+Zoom+User+Manual+V1.4.pdf.

- Global Road Safety Partnership. Drink Driving: A Road Safety Manual for Decision-Makers and Practitioners, 2nd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2007. [Google Scholar]

| No. | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Take-off weight | 907 g |

| 2. | Dimensions (unfolded) | 322×242×84 mm |

| 3. | Dimensions (folded) | 214×91×84 mm |

| 4. | Maximum speed | 72 km/h |

| 5. | Maximum altitude | 6000 m n.p.m. |

| 6. | Maximum flight time | 31 min |

| 7. | Range | 8 km |

| 8. | Climbing speed | 5 m/s |

| 9. | Descent speed | 3 m/s |

| 10. | Collision avoidance system | Omnidirectional sensors, positioned at the top, bottom, front, rear and sides of the drone. |

| No. | Parameter | Group | Series 1 | Series 2 | Series 3 | Series 4 | Series 5 | Series 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

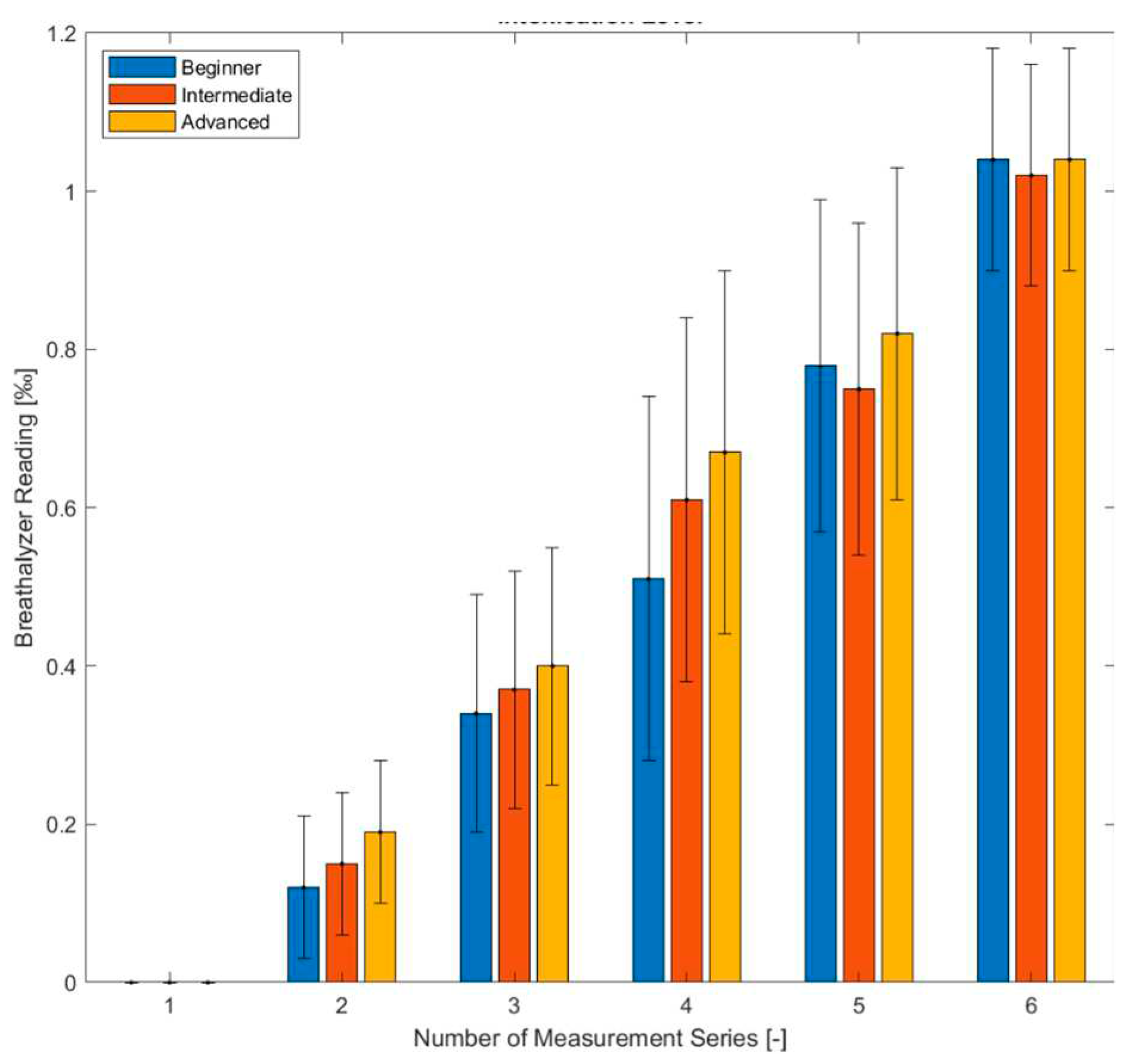

| 1. | Alcohol concentration of participants[‰] | B | 0,00 | 0,12 | 0,34 | 0,51 | 0,78 | 1,04 |

| I | 0,00 | 0,15 | 0,37 | 0,61 | 0,75 | 1,02 | ||

| A | 0,00 | 0,19 | 0,40 | 0,67 | 0,82 | 1,04 | ||

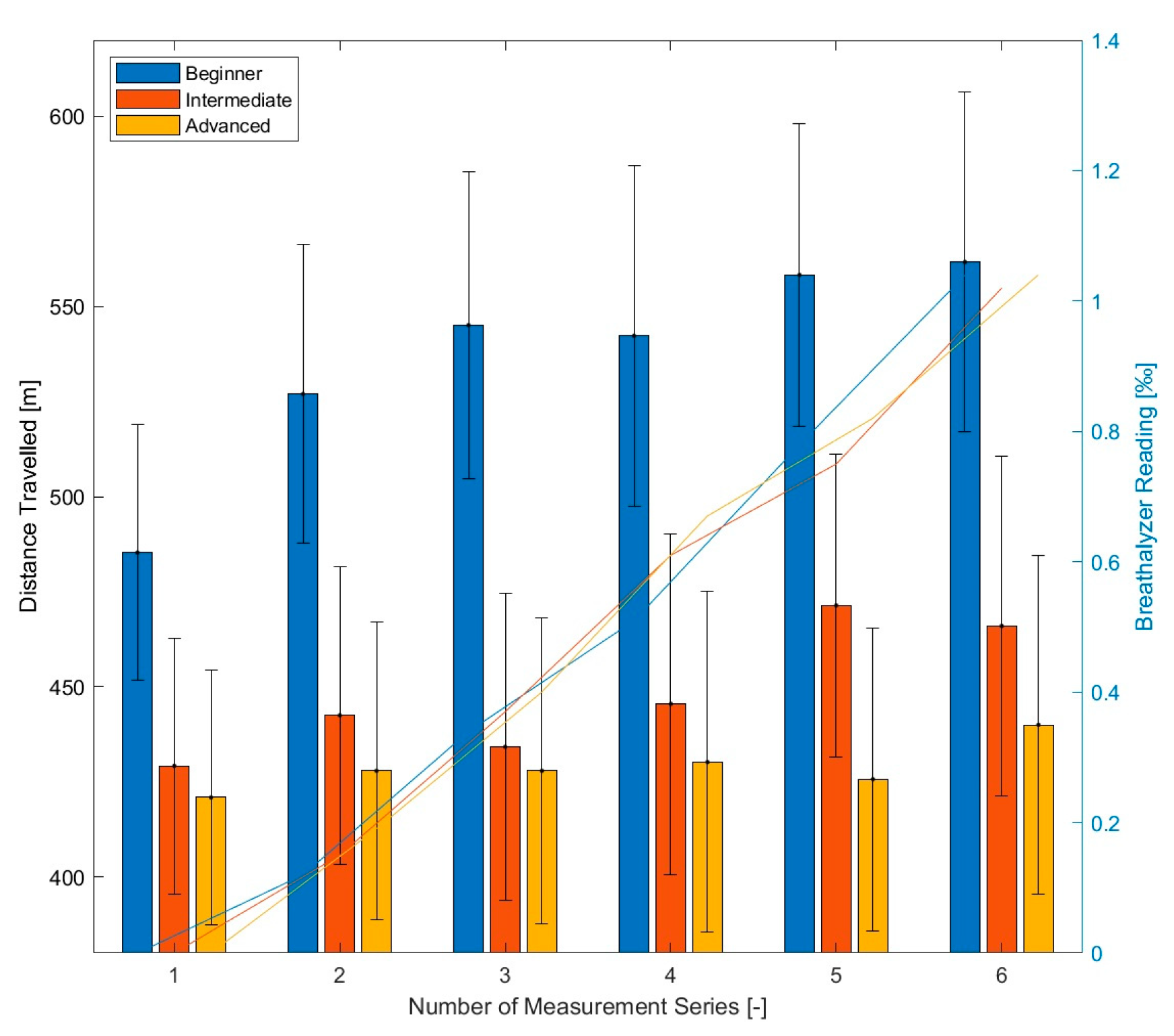

| 2. | Distance travelled [m] | B | 485,3 | 527,0 | 545,1 | 542,3 | 558,3 | 561,7 |

| I | 429,2 | 442,5 | 434,2 | 445,5 | 471,4 | 466,0 | ||

| A | 420,9 | 427,9 | 427,9 | 430,2 | 425,7 | 440,0 | ||

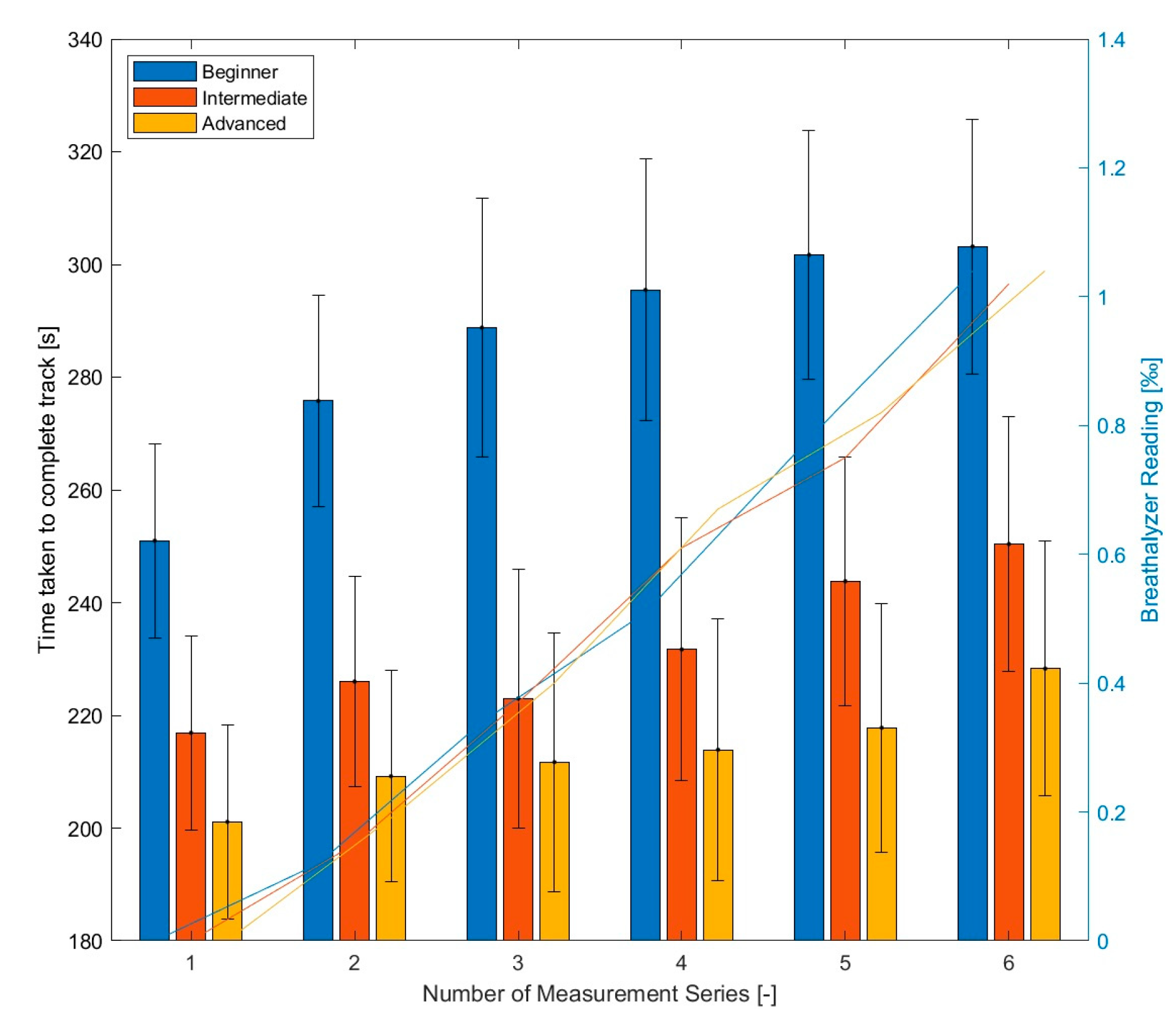

| 3. | Time taken to complete track [s] | B | 251,0 | 275,8 | 288,8 | 295,5 | 301,7 | 303,2 |

| I | 216,9 | 226,0 | 223,0 | 231,7 | 243,8 | 250,4 | ||

| A | 201,1 | 209,2 | 211,7 | 213,9 | 217,8 | 228,3 | ||

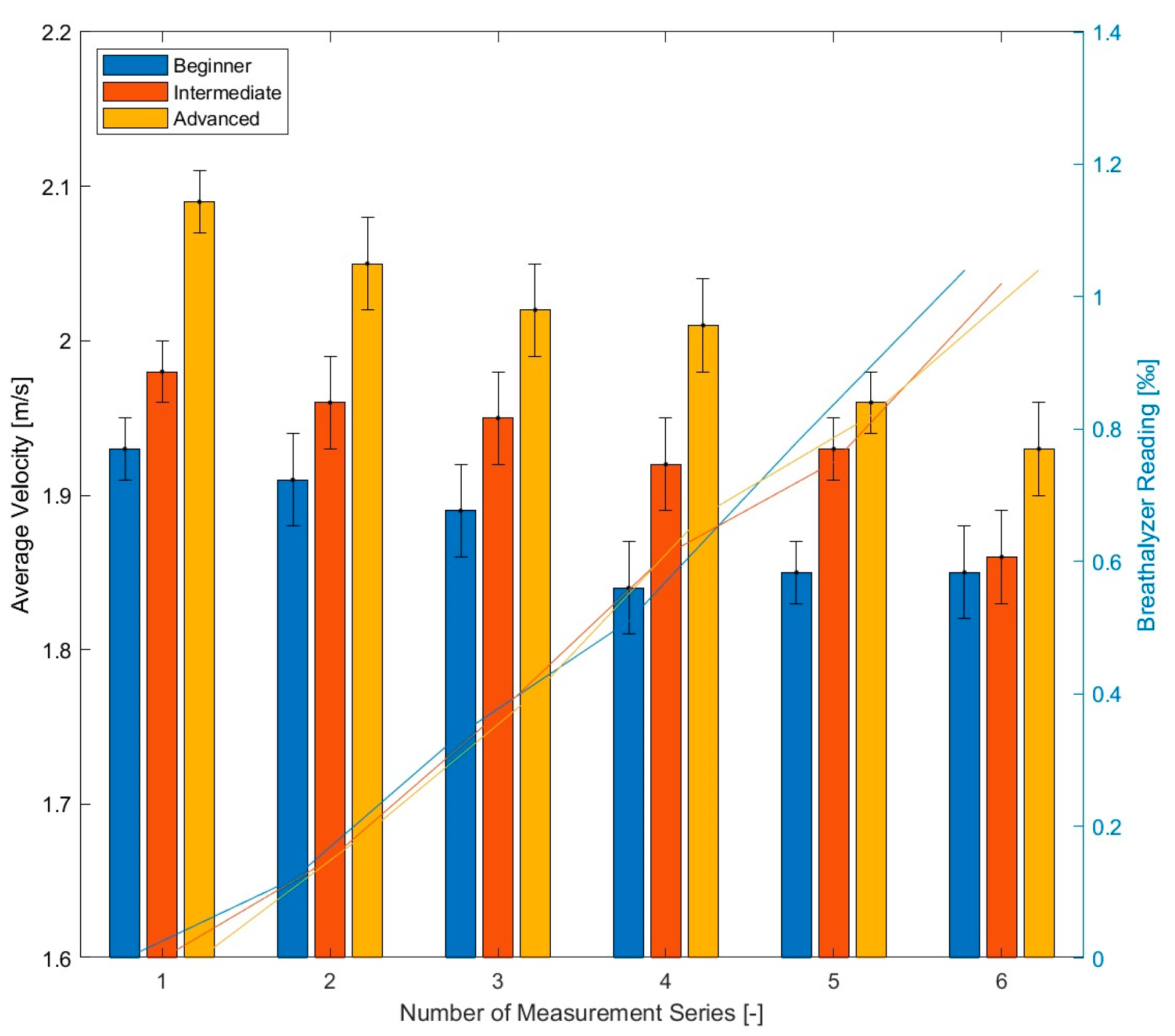

| 4. | Average velocity [m/s] | B | 1,93 | 1,91 | 1,89 | 1,84 | 1,85 | 1,85 |

| I | 1,98 | 1,96 | 1,95 | 1,92 | 1,93 | 1,86 | ||

| A | 2,09 | 2,05 | 2,02 | 2,01 | 1,96 | 1,93 | ||

| 5. | Number of committed mistakes | B | 2 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 15 |

| I | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 | ||

| A | 0 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 10 |

| No. | Parameter | Group | Series 2 | Series 3 | Series 4 | Series 5 | Series 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

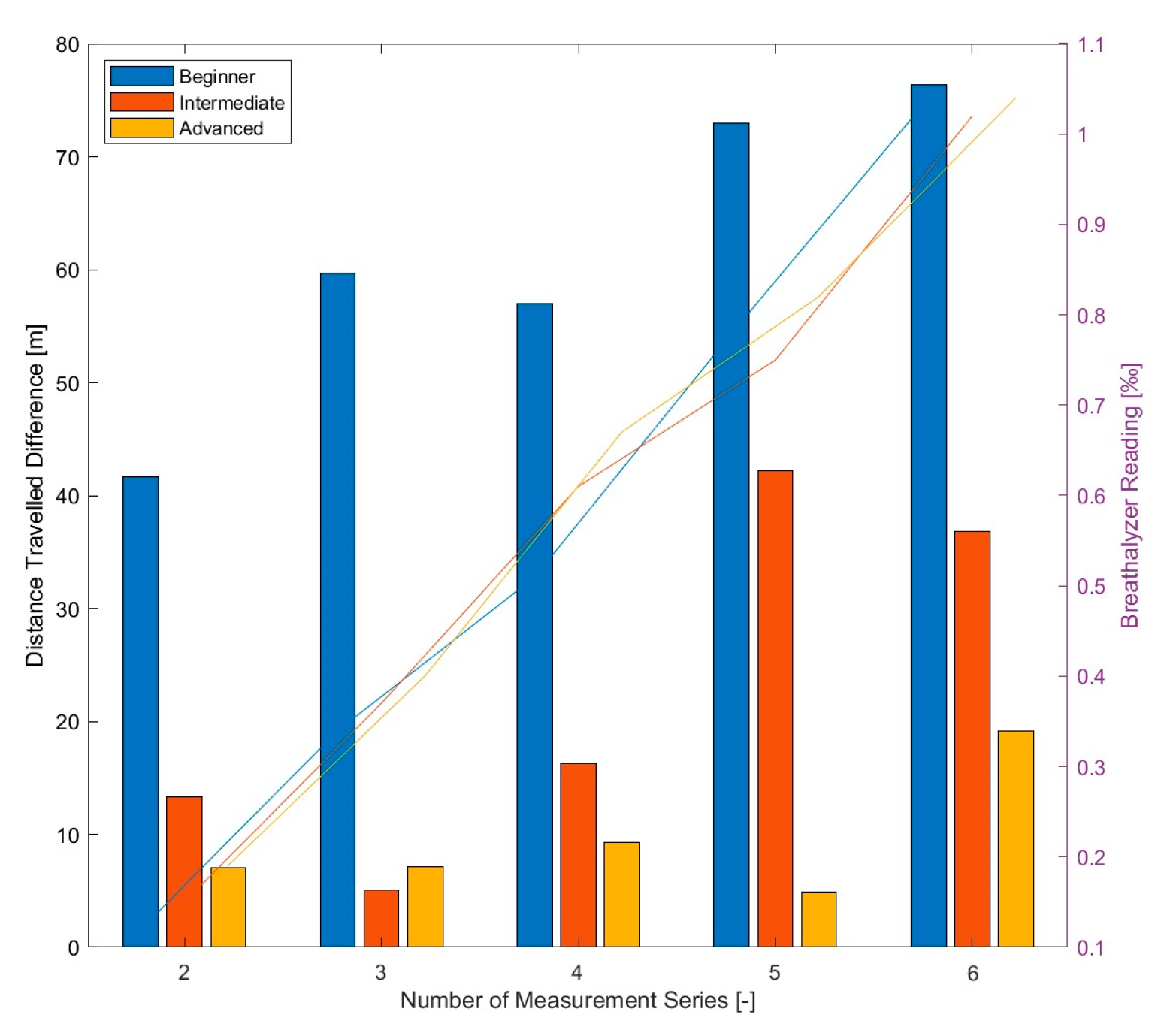

| 1. | Differences in distance travelled [m] |

B | 41,66 | 59,73 | 56,96 | 72,95 | 76,39 |

| I | 13,31 | 5,07 | 16,31 | 42,19 | 36,78 | ||

| A | 7,05 | 7,09 | 9,31 | 4,86 | 19,16 | ||

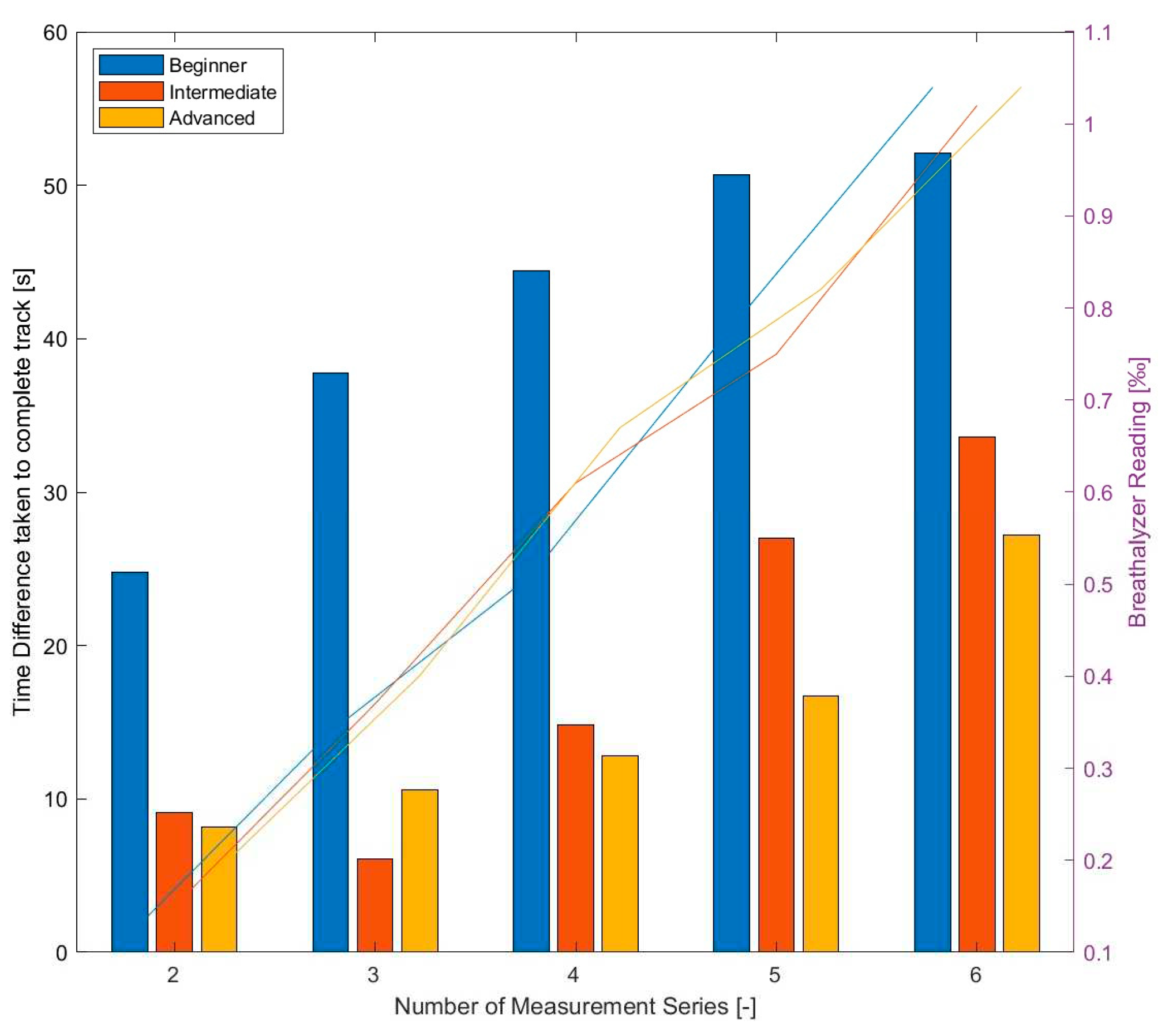

| 2. | Differences in time taken to complete track [s] |

B | 24,8 | 37,8 | 44,4 | 50,7 | 52,1 |

| I | 9,1 | 6,1 | 14,8 | 27,0 | 33,6 | ||

| A | 8,2 | 10,6 | 12,8 | 16,7 | 27,2 | ||

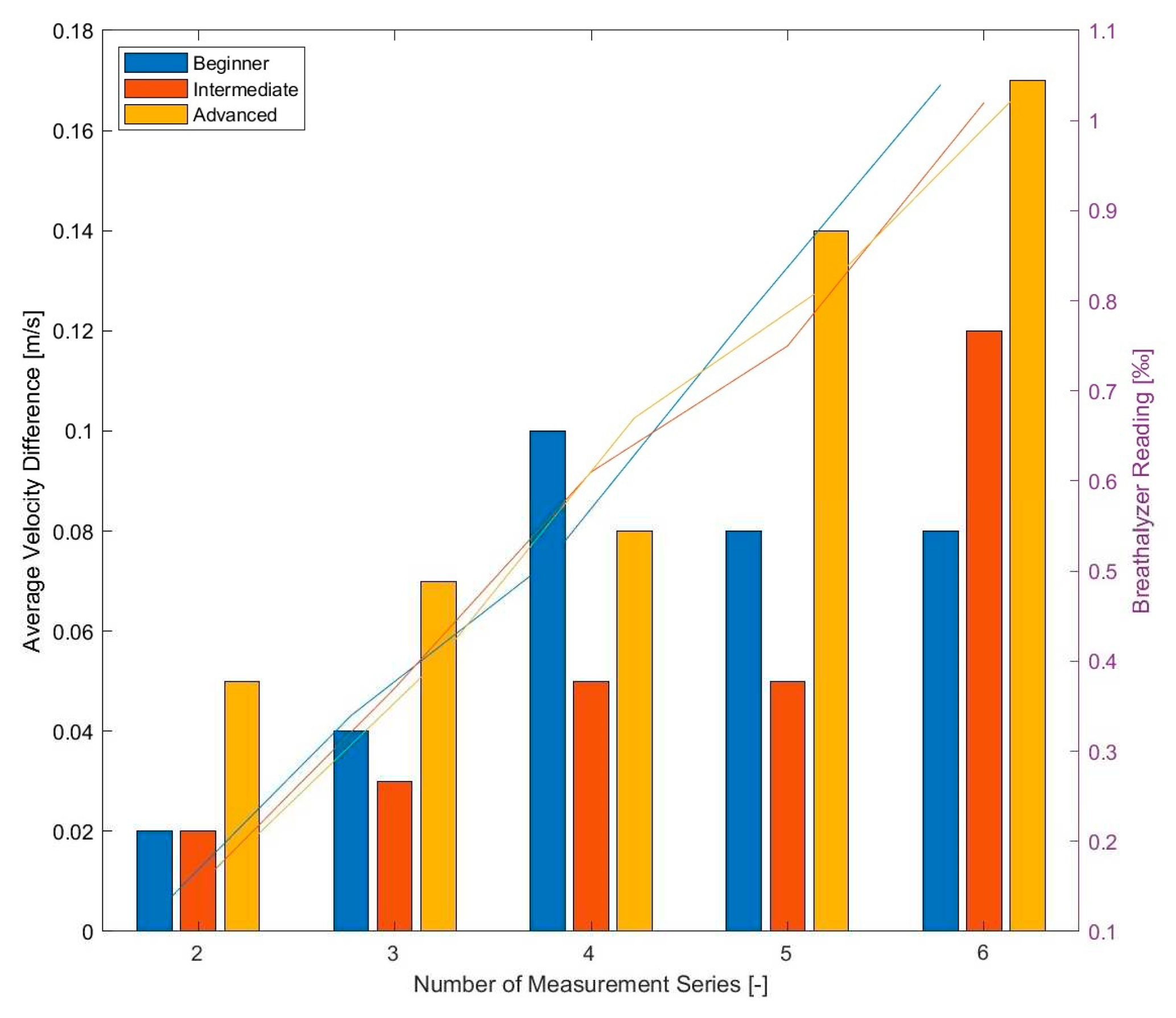

| 3. | Differences in average velocity [m/s] |

B | -0,02 | -0,04 | -0,10 | -0,08 | -0,08 |

| I | -0,02 | -0,03 | -0,05 | -0,05 | -0,12 | ||

| A | -0,05 | -0,07 | -0,08 | -0,14 | -0,17 | ||

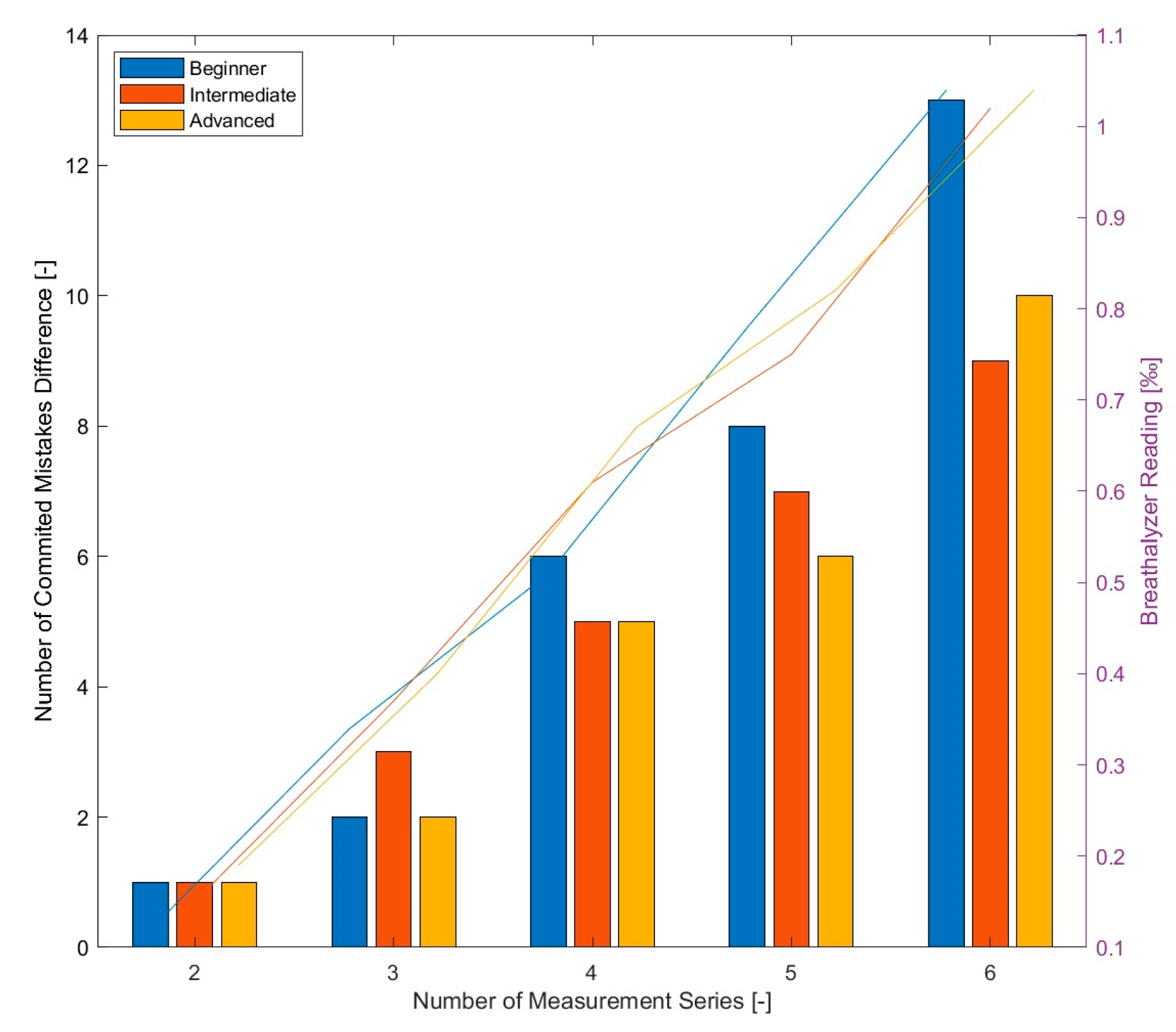

| 4. | Differences in number of committed mistakes | B | 1 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 13 |

| I | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | ||

| A | 1 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 10 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).