1. Introduction

In the 21st century, grandparenthood is a significant phenomenon in the fields of demography of ageing, social gerontology and sociology and it is mainly explored in the context of social aspects of ageing. It is poised to become one of the most significant demographic phenomena and social issues in contemporary South Africa [

1,

2]. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) have caused major social and economic devastation in South Africa, especially among children who have become orphaned by the disease. The premature death of parents due to HIV/AIDS leaves orphans without support, parental love, guidance, and resources, and this can be further followed by cycles of poverty, malnutrition, stigma, exploitation, and psychological trauma [

3,

4]. In many African societies and communities such as in South Africa, the obligation for the care and welfare of orphans is placed on the closely-connected members of the family, notably with the core expectation of these being the grandparents. The number of grandparents assuming the parental role of raising their grandchildren is becoming alarmingly high and has been showing a worldwide surge over the past 20 years [

3,

4]. Caregiving from grandparents ranges from primary care to co-care when living in an intergenerational home. In the absence of a parent, a group of grandparents, known as custodial grandparents, provide all of the child’s care in a household; such situations are prevalent in South Africa and commonly referred to as skip-generation households [

2]. The extended families that once characterised the black social structure have changed as a result of modernization and urbanisation in both developed and developing nations, and family structures and functions have changed over time [

5,

6]. In a typical family, older members who had been a part of the extended family were replaced by a different form of family.

In addition, Fernandes et al. [

7] reported the growing trend of grandparents parenting their grandchildren in the 1990s, which has also caught the attention of the press and policymakers in the United States of America. Previous studies have reported that 13.4% of the almost 7.1 million grandparents-grandchild households in the United States of America are custodial grand-families [

8]. According to Meyer and Kandic [

9], there has been an estimated 7% rise in custodial grandparenting in the United States since 2009. Since 1990, custodial grandparenting has increased in various low- and middle-income countries [

4], including those in Africa [

10] and Asia [

11]. According to Buchanan and Rotkirch [

12], and Nadorff and Patrick [

13], approximately 1% of all children in the United Kingdom and nearly 4.8 million children in the United States are raised by grandparents, while a study conducted by Hall et al. [

14] reported that about 4 million children were being raised by grandparents in South Africa. The justification for such a situation is differently accountable within each context and for different geographical locations. According to Buchanan and Rotkirch [

15],the main reasons why children in the United Kingdom end up living with their grandparents were owing to an increase in desertion, death of parents, parents’ incarceration, rising drug abuse, and an increase in divorce rates [

16]. In South Africa and other countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the death of parents from HIV/AIDS has left many children in this situation to be raised by their grandparents [

17]. Similarly, in Swaziland (formerly Eswatini), a majority of the rural children are forced to be under grandparental care as a result of poverty and HIV/AIDS [

18].

South Africa has been experiencing changing family structures, and the phenomenon has been evident before the time of apartheid and continues during the current democratic dispensation. However, one of the noticeable changes in the family structure over the years is the transition from nuclear and extended families to skip-generation family structures [

1,

2]. The transition in the family structure has been attributed to issues such as labour migration, non-marital child-bearing, poverty, gender inequality, death of parents, and neglect among others [

19,

20]. HIV/AIDS has also played a significant role in changing the family structure, leaving children with family members, and grandparents in particular [

21,

22]. With these transitions, non-parent caregivers have taken the responsibility of becoming informal caregivers to people living with disease or disability, and orphaned children [

21,

23]. Likewise, it has been noted that grandparents have been increasingly taking responsibility for the primary care of orphans in the absence of biological parents in South Africa, resulting in what is known as grand-families [

19]. From 1996 to 2011, grandparent headship of households has increased from 11.9% to 12.3%, showing an increased in the importance of grandparents’ contributions in South African households [

19,

24]. Besides, in 2017, almost 2.7 million children were living with grandparent caregivers in the absence of their biological parents [

1,

25], with more female grandparents caring for orphans compared to male grandparents. Thus, grandmothers have become the new mothers with transforming roles, signifying the existence and reality of grand-families in South Africa. Caregiving among grandparents is a moral and cultural obligation in African societies. Benefits of caregiving among grandparents have not gone unnoticed as they receive much satisfaction from parenting [

26], and younger grandparents in the age cohort less than 40 years and who enter early into grandparenthood, to a certain extent, have reported greater satisfaction as caregivers to their grandchildren [

27].

However, the impact of grandparenting has yet to be significantly recognised and documented in South Africa. Caregiving from grandparents usually produces numerous benefits, such as having a close-knit relationships with the children they are caring for. However, grandparents still face many difficulties, which include the role of caregiving, which is demanding, insufficient or no formal caregiving training, and exposure to burdens in the form of physical, mental, social, and economic hardship [

1,

27]. Furthermore, grandparent caregivers often present with health challenges such as poorer emotional well-being and declining psychological health as a result of stressors arising from caregiving to grandchildren [

6,

19]. A study conducted by Kidman and Thurman [

21] among 726 caregivers of orphans in the Eastern Cape province revealed that 23% of caregivers reported to have experienced chronic illness for three months or longer in the previous year. Also, another study conducted in Mankweng in Polokwane among twelve grandparent caregivers of orphans revealed that grandparent caregivers reported having hypertension, diabetes, and bodily aches owing to old age; one grandparent indicated that her poor health was as a result of stress caused by her granddaughter [

6,

26]. The deterioration of the health of grandparent caregivers owing to stress are usually triggered by being unable to cope with the physical demands of raising small children and financial constraints. Moreover, in a qualitative study conducted in Vhembe district in Limpopo province, grandparents were found to have reported experiencing anxiety, emotional stress, depression, bodily pain, hypertension and high blood pressure when providing caregiving to their grandchildren [

1,

6].

South Africa remains a complex mix of different races, cultural identities, languages, ethnic bonds and social classes, as the country continues to have racial segregation. This racial segregation may perhaps have directly or indirectly created social concerns such as rape [

28], children/adolescents being pregnant [

29], HIV and AIDS [

30], tuberculosis (TB) [

28], obesity [

31], domestic violence [

29], a high crime rate [

29], unemployment [

32], a high incidence of divorce [

33], addiction to alcohol [

30] and dependency on drugs/ substance use [

34]. There is a dearth of studies on ageism conducted in South Africa, despite it being pervasive, and affecting people of all age cohorts, from childhood onwards, with serious and far-reaching consequences for individuals’ well-being, health and human rights [

35,

36]. Ageism is typified by the stereotypes (how one thinks about grandparents as a parental caregiver), prejudice (how one feel about grandparents raising their grandchildren) and discrimination (how one act towards grandparents giving parental care) has a great impact on perceptions of other persons based on their age. Owing to the little attention ageism has attracted, issues associated with grandparenting and positive contributions by grandparents acting as caregivers to their grandchildren are not documented [

37,

38,

39]. Adopting a better view of seeing the core importance of grandparents playing the role of caregiver, despite having challenges as a result of care giving, does not truly reflect the resilience of being a grandparent taking up the challenges of parenting their grandchildren in the absence of their biological parents.

The General Household Survey (GHS) showed that about 9% of children were paternal orphans, 3.1% of children (aged 0–17 years old) were maternal orphans, and 2.4% of children were double orphans [

27,

40]. Also, Statistics South Africa reported that the proportion of orphaned children in KwaZulu-Natal province was 18.7% and one of the highest in South Africa [

27]. Consequently, orphans have to rely on their aging and often impoverished grandparents, who are not physically, emotionally, and financially ready for the new responsibility. This leaves grandparents with several challenges that they have to face, despite their incapacity to do so, which often has detrimental effects on their health outcomes [

41,

42]. This informs the underlying motivation for this study, as the range of health problems associated with grandparents carrying out caregiving has not been addressed. They are often the neglected portion of the population owing to stigmatization resulting from their children who died as a result of AIDS and being in the aging population with critical needs [

18,

27]. Few studies have been conducted in South Africa to examine health outcomes associated with grandparents acting as caregivers to orphaned children [

19,

36].

One neglected area of research is the determinants of health outcomes of grandparents caring for double orphans in South Africa. The purpose of this study is to examine the determinants associated with grandparents who are parenting as caregivers, and the health challenges they are exposed to as caregivers to grandchildren who are double orphans. Findings from this study will be relevant to Social Gerontologists, Demographers of Ageing, and Sociologists, and also to other health care practitioners (medical practitioners, community health workers, social workers and public health experts) and policy makers, as they will acquire knowledge through an in-depth understanding of this phenomenon from the study outcome, which will be of interest within the South African context.

4. Discussion

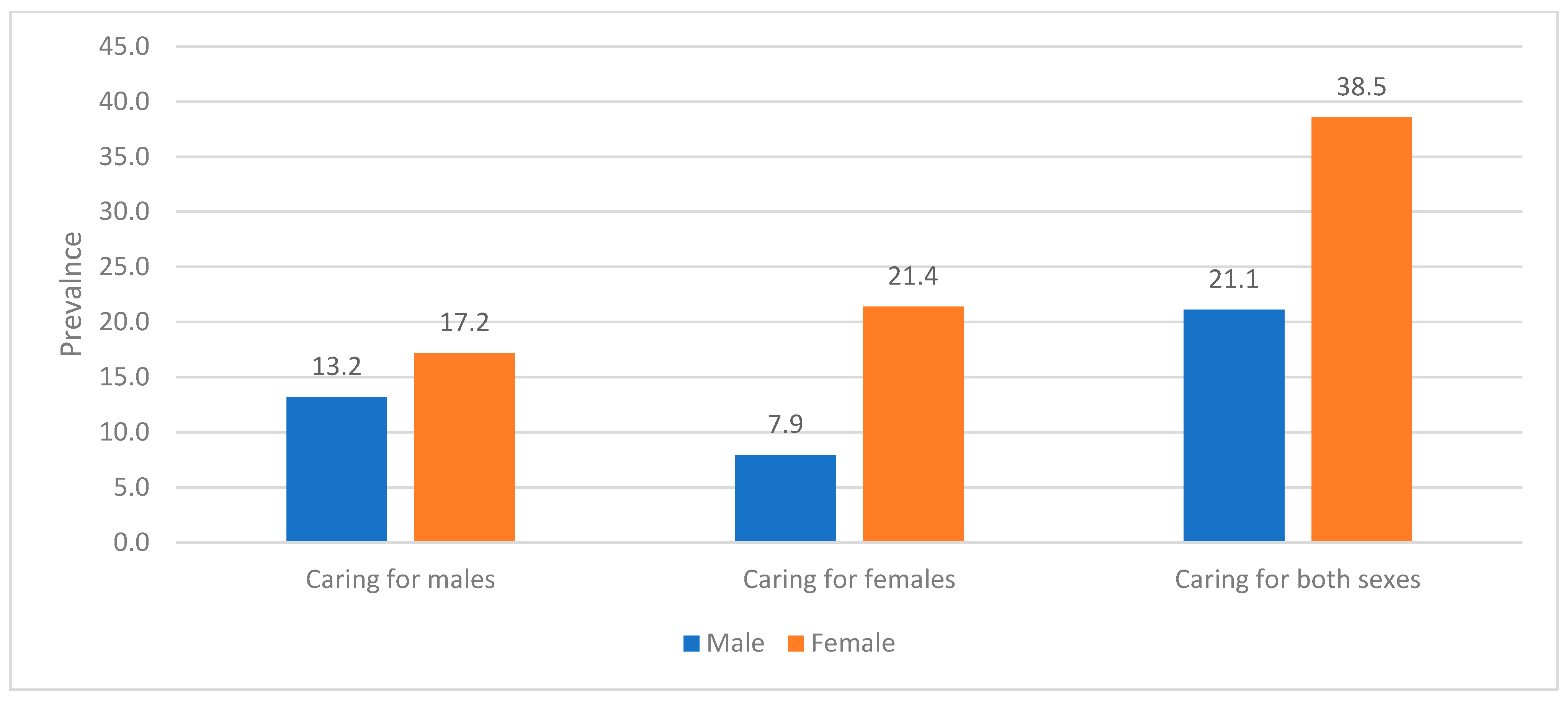

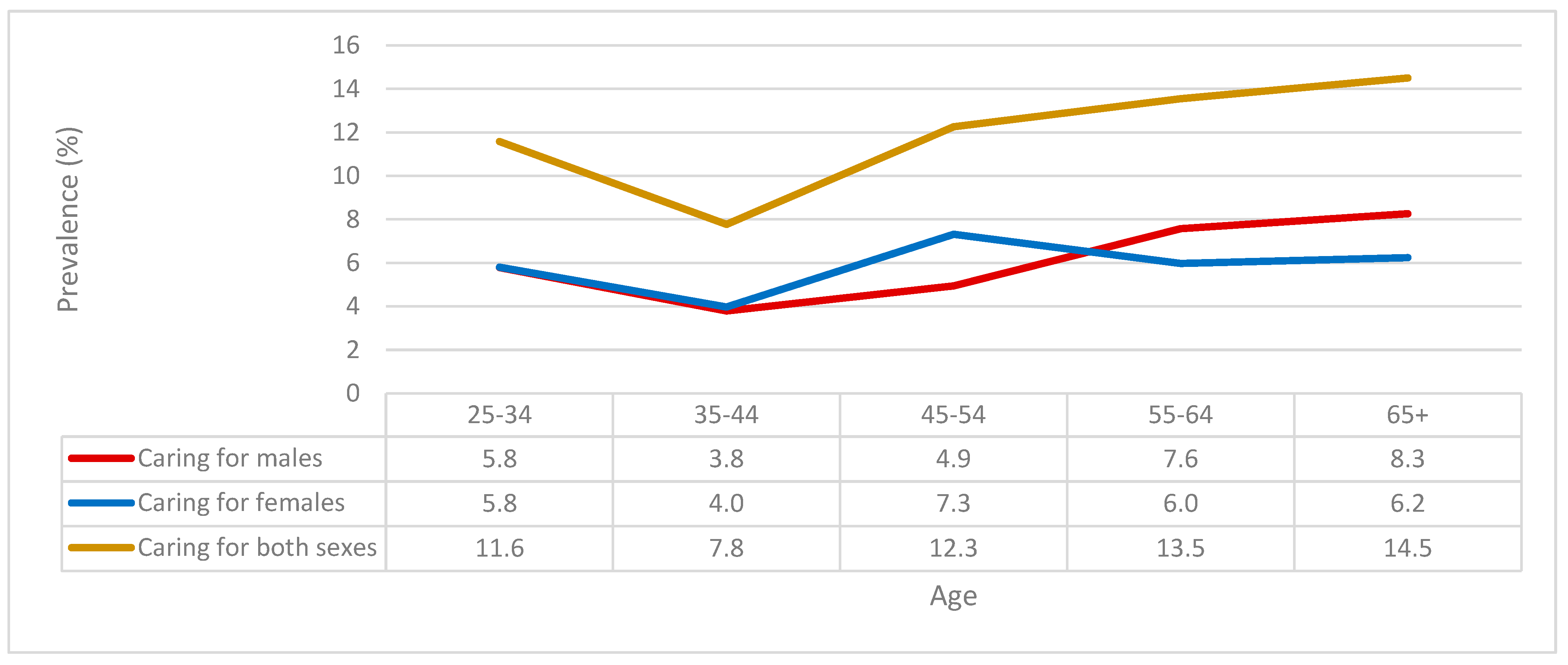

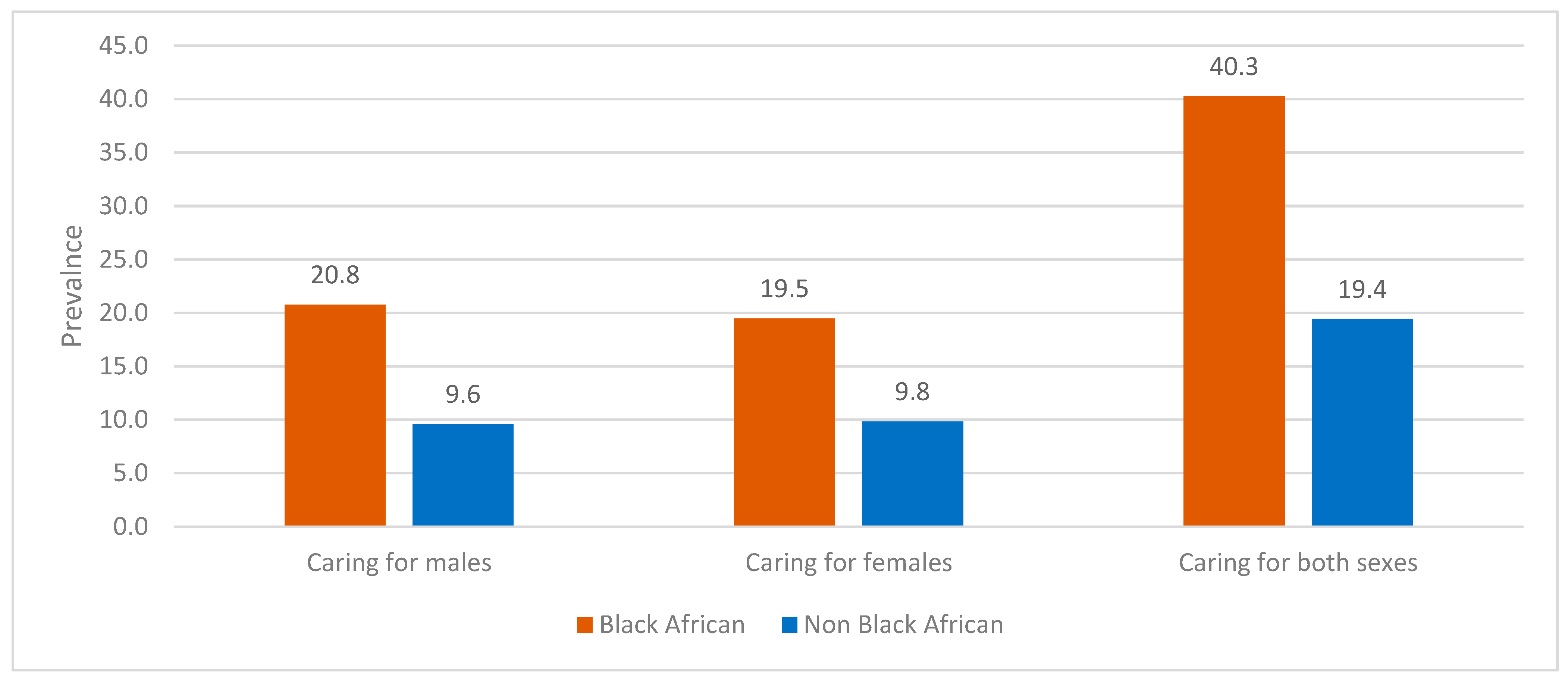

The results of the 2017 wave 5 of the NIDS are presented in this study, from nationally representative data, carried out to keep track of the well-being of South Africans [

49]. This study indicated that grandparents in the age cohorts of 55 – 64 years and 65

+ years experienced a higher prevalence of health challenges than those in the age groups of 25 – 34 years and 35 – 44 years. Further, grandparent caregivers of female double orphans reported the highest prevalence of health challenges, compared to grandparent caregivers of male, and both female and male double orphans. Also, the prevalence of health challenges remained highest among Black African grandparent caregivers of male, female, and both sexes double orphans. The observed prevalence of health issues among grandparents who are caring for their grandchildren after their parents pass away from HIV/AIDS is an indication that South Africa has not made much progress towards the SDG 1, SDG 2, and SDG 3 targets [

48,

54]. In a high-income country, family support is often passed down through the generations, especially from parents to children, and this significant kind of help includes looking out for the ages that follow. Grandparents continue to be an essential source of child care for many working parents, even though the number of children they manage has decreased as formal child care has increased.

Meanwhile, the proportion of grandparents who raise their grandchildren with them has grown over time [

18,

20]. Some grandparents step in to raise their grandchildren when the parents cannot do so owing to illness, drug addiction, or being in prison [

38,

54]. Also, other grandparents share custody of their grandchildren in response to their adult child’s financial need, separation and divorce, or employment commitments, as well as the death of one or both parents due to health condition such as HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis etc. [

55,

56,

57,

58]. Grandparents caring for grandchildren provide a critical provision and a fruitful platform for their grandchildren. The benefits of using grandparents to care for or raise grandchildren are both public and private, much like those of other forms of caregiving. Using grandparents to raise or care for grandchildren, particularly after the death of parents, preserves public resources and avoids discussions about public duty. However, as the importance of grandchild care has grown, concerns have surfaced that the benefits, as mentioned earlier, may jeopardise the well-being of grandparents [

38,

58], and the influence of caring for double orphaned grandchildren on grandparents’ health is a major focus of concern in this study.

Therefore, this study found that cohorts of grandparents of increasing age as caregivers to double orphans suffered many health challenges, as they are solely responsible for the well-being of their grandchildren [

59,

60]. We also found significant differences as age increased when looking at health challenges experienced by grandparents as caregivers to double orphans. This finding is consistent with another study conducted by Spinelli et al. [

61], a study, which found grandparents derived satisfaction as caregivers to their grandchildren despite experiencing other social problems. Grandparents play an important role in family life and is culturally acceptable to have grandparents as caregivers across sub-Saharan African nations such as in Nigeria [

62], Ethiopia [

63], Malawi [

55] and Mozambique [

54]. Furthermore, our findings support the assumptions that when parents are unable or unwilling to care for their children, grandparents are the first option. To reduce the effects of children growing up without parents, grandparenthood should be encouraged and supported to take on caregiving duties and parental roles to their grandchildren [

61]. Also, findings from this study can be generalized to a bigger population as a result of the sample scope included in this study [

59]. Additionally, in-depth research is required to identify the difficulties and issues that are being faced by grandparents as caregivers, especially in this era of non-communicable diseases, and communicable diseases such as tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS [

19,

42], considering the high prevalence of young parents out of work with children [

61,

62] Thus, several studies have documented positive responses from studies that have worked on grandparents as caregivers to their grandchildren despite other challenges they faced during the process of caregiving. As such, it would be very important to create and develop strategic strength-based interventions to tackle all the challenges plaguing grandparents as caregivers [

54,

59].

Attempts should be made to assist and allow grandparents to raise their grandchildren in cases when both parents have died, rather than trying to dissuade them from taking on the role of guardian and proxy parent [

19,

54]. To address some of the health challenges faced by grandparents, resources, such as social, financial, and health, that will reduce pressure and fatigue related to grandparents’ contribution to parental role to their grand kids, should be provided for them [

19,

42]. By strongly encouraging healthy intergenerational ties, this will reduce abuse and desertion of elderly people like grandparents [

60,

65]. Furthermore, our results showed that health conditions experienced by grandparents when providing caregiving to double orphans include joint pain/arthritis, backache, body ache, fever and headache. Other health concerns such as chest pain, swelling of ankles and a cough were mentioned by grandparents in this study. Caregiver burnout can occur in grandparents in a state of physical, emotional and mental exhaustion. Stressed grandparent caregivers may experience fatigue, anxiety and depression when providing parental care to their double orphaned grandchildren [

65]. After all, being a grandparent serving as a caregiver is highly demanding, making it difficult for the carer to tend to their own needs first. Also, studies have shown that providing care can have a severe impact on one’s physical and mental health, negative emotional effects, and poor treatment of orphaned grandchildren they are caring for as grandparent caregivers [

66]. Also, other studies have mentioned that grandparents as primary caregivers stated depression, anxiety, changes in appetite (such as eating too much or too little), hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and chronic fatigue as health conditions they were suffering from as a result of attending to the needs of their orphaned grandchildren. These aforementioned health conditions may be caused or aggravated by the demands and necessities of caregiving to double orphans by grandparents [

67]. In addition, there is a critical need to conduct research that will look at an extensive review of health conditions and the health risk for harmful medical issues that may arise among grandparents providing care for double orphans in South Africa.

Furthermore, demographic (age, education), economic (regular salary, pension), and health-related factors (perceived health status, health consultation) in the unadjusted and adjusted models of the multivariate analysis of this study have been shown to influence health conditions of grandparents as caregivers to their double orphaned grandchildren, and this assertion is in tandem with the findings of other studies [

7,

38]. In this context, this study found that among grandparents as caregivers, those aged 55

+ years caring for male double orphans had more odds of experiencing health conditions compared to those aged 25–34 years, and this result is supported by several studies [

38,

66]. This may be due to the fact that with increasing age of older persons, their bones tend to shrink in size and density, weakening them and making them more susceptible to fracture. Generally, in older persons, their muscles tend to lose strength, endurance and flexibility, which can affect their coordination, stability and balance. Also, at the genetic level, ageing results from the impact of the accumulation of a wide variety of molecular and cellular damage over time [

60,

66]. Stress and exhaustion from caregiving can lead to a gradual decrease in physical and mental capacity, a growing risk of disease, and ultimately death [

68].

Thus, given that they are only somewhat connected to an individual’s age, these changes are neither linear nor consistent. Despite biological changes, ageing can frequently be attributed to other major life events like retirement, moving to a more suitable home, and the death of “significant others,” and South Africa, like many countries globally, is experiencing a significant demographic shift with the rapid growth of its ageing population [

1,

69]. Also, studies have shown that grandparents with primary education had higher odds of experiencing health challenges as they are less likely to have adequate and appropriate knowledge on how to prevent and manage these health conditions resulting from caregiving to their grandchildren, compared to their counterparts with no education [

11,

70]. The finding is consistent with past research that has found that grandparents with lower educational attainment may have poorer health than those with greater educational attainment [

39,

71]. This pattern is attributed to the large health inequalities brought about by education. However, these study findings revealed that grandparents with higher education in the adjusted model had higher odds of health challenges experienced as a result of being the primary caregiver to their grandchildren. This study finding is not inconsistent with previous studies, as a few other studies have mentioned that educated grandparents experience health challenges owing to self-neglect. Recent studies have evidently stated that self-neglect is linked with adverse outcomes concerned with older adults’ physical [

4] and psychological well-being [

6], illness [

38,

39], death [

68] and healthcare utilization [

72,

73].

Results from our study show that grandparents with economic factors such as no regular salary or pension were related with increased chances for health challenges experienced. This supports earlier studies, which posited that people with a lower socioeconomic status tend to be more prone to health issues that comes from pressure and strenuous activities [

1,

5]. The reason grandparents with no regular salary or pension are plagued with health conditions when acting as the primary caregiver to their grandchildren may be associated with ‘fear of the unknown’ in trying to keep up with increased responsibilities associated with earning more. Studies have shown that many fears of grandparents who are caregivers to their grandchildren without a regular salary or pension can be traced to a negative experience that has been traumatic when proper care is not given to their double orphaned grandchildren [

7,

35]. A few studies have also believed that phobias can stem from a learned history, and many older adults are susceptible to being anxious about the unknown and may lead to developing a fear of the unknown [

23]. Moreover, this study found significant differences in the influence of health-related factors such as perceived health status and health consultation among grandparents in this study. For instance, literature has shown that, over the years, poor perceived health status has been associated with increased odds of experiencing health challenges [

19,

22]. In agreement with these earlier findings, this study found that grandparents with poor perceived health status were associated with higher odds of experiencing health challenges as primary caregivers to their grandchildren. In agreement with these earlier findings, this study found that perceived health status is associated with healthcare service utilization and illness in developing countries [

74,

75]. Yet, little is known about the factors associated with perceived health status among grandparents who are primary caregivers to their double orphaned grandchildren [

41,

55].

Furthermore, grandparents who never had a health consultation are more likely to experience health conditions. Studies have claimed that knowledge or information gained through interactions with individuals whose presence extends beyond the scope of a single medical visit may alter choices over time and affect behaviours [

57,

76]. According to a different research, using alternate information sources may affect how well people communicate during consultations with healthcare providers [

32,

36]. For instance, in this era of internet and social media platforms, rich sources of information and expert knowledge can be made available to grandparents through internet platforms if they have the facilities to access internet files. Other studies have acknowledged a range of other external persons that can motivate positive and healthy communication with their ‘significant others’ during healthcare consultations [

4,

11]. For example, a patient’s family, a doctor’s social and health network, and the media (radio, newspapers, and television) play an important role in grandparents’ clinic sessions. Thus, grandparents’ consultation on their health conditions is very important in influencing the improvement of their personal health with shared decision-making.

4.1. Further Discussion: Insights from changing demography of grandparenthood in South Africa

Demographic changes affect the time that individuals spend in different family roles, and one type of family relationship affected by early fertility is grandparenthood. Historically and in modern-day societies, three-generation families are more common now than earlier, because children and grandchildren have higher chances of survival, and more people live long enough to see their grandchildren grow (Margolis, 2016). However, family formation patterns have also changed, as fertility declines, leading to increased childlessness; also, the postponement of marriage and childbearing affect the proportion of the population that ever-become grandparents and the age at which grandparenthood begins for either younger or older age cohorts (See Appendices 1‒8) (Statistics South Africa, 2021). Thus, in contemporary South Africa, many families continue to undergo family transition and changes in family formation, with a range of challenges. A majority of South African families are being confronted with dual challenges of poverty and unemployment, making economic provision much more difficult in rural households. Since 1994, HIV/AIDS and TB, and more recently the Covid-19 pandemic (Hosegood, 2009; Artz et al., 2016), have placed families under significant strain, with the loss of caregivers and economic providers, as families in South Africa are characterized by significant resilience.

However, being a grandparent relates to a life-course, and is clearly defined by status which determines and affects other stages in the life course, as being a grandparent is linked to retirement. Yet, the transition to grandparenthood is associated with a change in status, roles, and identities which vary greatly in different contexts. However, the concepts of grandparenthood and ageing are related, as a result of the normative age at childbearing may be linked to the timing of grandparenthood and the social definition of ageing but may diverge from social expectations. Therefore, unlike ageing, grandparenting occurs “within a wider and more flexible age range” (Statistics South Africa, 2018). According to Statistics South Africa (2021), more than 207 children were married, comprised of 188 brides and 19 grooms, and these marriages were officially documented. Of the child marriages, 37 were registered as civil marriages and 19 were customary marriages (Statistics South Africa, 2021).

In South Africa, younger adult grandparents aged 30 – 39 years (297 females and 40 males) have been documented in Statistics South Africa (2018). Many marriages conducted in the customs and traditions in the rural communities were not documented with the Department of Home Affairs, leading to under-reporting of cases of early child marriages in South Africa. Thus, several factors have been associated with the emergence of younger grandparents in South Africa such as increased child marriage (UNICEF, 2022), teenage pregnancies, Ukuthwala cultural practices, income generated from lobola negotiations, lack of accountability of community leaders towards child kidnapping, and religious beliefs. These factors have been shown to contribute to the demographic changes of the emergence of early grandparenthood in South Africa (Statistics South Africa, 2018). Regarding child marriage, Eastern and Southern Africa are among the regions with the highest prevalence of child marriage globally. At present, nearly one third (32%) of the region’s young females were married before age 18 (Mwambene, 2018). Concerning teenage pregnancies, Statistics South Africa (2020) reported almost 34,000 teenage pregnancies, with 660 of those being girls under the age of 13 (Payne et al., 2020; Jonas, 2021). In South Africa, some of these teenage pregnancies have been linked to rape cases and arranged marriages (Statistics South Africa, 2020).

Also, the prevalence of teenage pregnancies is high and is associated with rape and indecent sexual relationship among teens. Most of these teens do not have knowledge of the use of contraception or have access to sexual and reproductive health clinics. These barriers have led to an increased number of teenage mothers and fathers having children, resulting in their own children following the same path of being a teenage parent, and making their parents become young adult grandparents (Statistics South Africa, 2020; Jonas, 2021). Also, Ukuthwala cultural practices have been reported to contribute to early grandparenthood, as it is a cultural form of abduction that involves kidnapping a girl or a young woman by a man and his friends or peers with the intention of compelling the woman’s family to endorse marriage negotiations (Mwambene et al., 2021). Also, it was once an acceptable way for two young people in love to get married when their families opposed the match (and so was actually a form of elopement) (Matshidze et al., 2017; Mwambene et al., 2021). Over time, Ukuthwala has been abused, however, “to victimize isolated rural women and enrich male relatives”, as older men are taking advantage of the cultural practices by marrying these children and sexually abusing them (Kheswa et al., 2014; Matshidze et al., 2017). This type of cultural practice is common among the Xhosa and Zulu people from the Eastern Cape, Limpopo, and KwaZulu-Natal provinces (Rice, 2014).

Similarly, Lobola payment is a cultural practice in South Africa where a bride price is paid to the bride’s family for her hand in marriage. This customs are sometimes abused and excused to erode human dignity and reinforce corrupt tendencies. This demeaning behaviour often handicaps the social welfare of a society and Lobola payment appears to be one of the most exploited praxes. Studies have shown that the identity of Lobola has shifted from a token of appreciation to a commercial activity, where the female family from a poor rural household generates income from the Lobola negotiations without their female relative consenting to marriage activities (Diala et al., 2021; Sennott et al., 2021). Religious leaders’ frown upon children born outside wedlock, and pregnant teenagers are forced to enter into marriage, as illegitimacy is regarded as sin-related, with the stigma justified as a reprimand from God. This form of coercive behaviour has aided early child marriages with pregnancies, without addressing the roots of early sexual orientation among teenagers.

In South Africa, the rights of illegitimate children are protected and recognised by the Children’s Act of 2005. This law has abolished legal differences involving legitimate and illegitimate children, who are now treated equally in terms of inheritance rights (Nabugoomu et al., 2020; Mkwananzi et al., 2022). Few studies have linked this intergenerational transition of demography of grandparenthood. Demographic transitions of family formation are linked with composition and transition of various family types. However, daughters of teenage mothers have been shown to be more likely to become teenage mothers at younger ages, linking teenage fertility to family birth history (Margolis, 2016). According to the theory of socialization, children born to teenage mothers have a higher chance of being teenage mothers, resulting in inter-generational transmission of early childbearing, owing to factors such as reduced parenting, marital instability, and an environment of poor socio-economic conditions (Sooryamoorthy et al., 2016; Makiwane et al., 2017). In South Africa, fertility behaviour of teen mothers, such as their age at first birth, have been observed to influence the age at first birth of their daughters, as family disorganization traits can be transmitted to their daughters by teen mothers (Chenga et al., 2014).

4.2. Strengths and limitations of the study

This study has several major strengths and limitations. First, to the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the first cross-sectional survey and nationally representative data that investigated the sociology of ageing and demography of ageing among grandparents who are caregivers to their double orphaned grandchildren. Second, the data analysis was basically conducted to determine the prevalence of grandparents who are caregivers to double orphans as in South Africa and associations based on the likelihood of the explanatory factors, and not provide a measure of causality; however, insight can be gained from using the 2017 National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) wave 5 datasets from South Africa to improve the study’s generalizability to other settings or populations. Third, to the best of the author’s knowledge, this is the first time that binary logistic regression models was aimed at elucidating the explanatory factors of the likelihood of the health outcomes of grandparents caring for double orphans in South Africa. There were some limitations, however, that need to be highlighted. First, owing to the nature of the study, we cannot draw causal inferences from the findings. This study also suggests the use of ethnographic methods that may unravel other possibilities that may influence the health outcomes of grandparents caring for their double orphaned grandchildren.

4.3. Implications for Social Gerontology and Demography of Ageing Research and Practice

The finding is consistent with previous studies that have found that grandparents with lower educational attainment may have poorer health than those with greater educational attainment. In most cases, grandparents have taken over the full responsibility of bringing up grandchildren as a result of unemployment, drug or alcohol abuse, or death. In South Africa, the aforementioned concern is exacerbated by changes in family structure owing to the severe impact of HIV/AIDS-related deaths, especially among young adult parents, leaving behind many orphaned children. This has brought about a change of roles for many grandparents, who have felt morally and culturally obliged to take care of their grandchildren, despite not being prepared for this parenting role. This study’s findings showed that there is a positive association between grandparents’ health outcomes and the role of caregiving to grandchildren, which agrees with several studies [

4,

10]. The growing number of grandparents as caregivers increases demands on the public health system and on medical and social services, due to adverse health conditions, contributing to disability, diminish quality of life, and increased health- and long-term-care costs. Therefore, to address this social issues, insights from this study will be valuable to social and healthcare practitioners, who play a vital role in offering services to grandparents as caregivers to their grandchildren who are doubly orphaned. There is a need for collaboration between various stakeholders and community health workers to empower and harness grandparents’ resilience to continue caring for their doubly orphaned grandchildren. Social gerontologists and demographers of aging recognize the significance of collaboration and team work, therefore through their research and practices will go a long way to provide platforms for developing appropriate and adequate health interventions that will create welfare resources that will cater to the needs of grandparents taking the role of caregivers. Furthermore, policymakers, academics and relevant role players will gain an in-depth understanding of this phenomenon from the South African context.