1. Introduction

Atherosclerosis is considered to be a dynamic, progressive disease consisting of a combination of endothelial dysfunction and inflammatory arterial wall disorder. Regarding cerebrovascular disease, carotid atherosclerotic disease is a complex condition that can be a precursor to stroke, leading to irreversible neurological deficits or death. Stroke, a pathology of the elderly, is the second leading cause of death worldwide according to the latest statistics and may appear in the case of moderate and severe carotid atherosclerosis, usually symptomatic, due to unstable plaques [

1,

2,

3]. Severe stenosis caused by atherosclerosis of the carotid artery is responsible for more than 15% of strokes and transient ischemic attacks (TIAs), and this stenosis occurs at the level of the common and internal carotid arteries [

4,

5].

The clinical studies have demonstrated that most patients with high-grade stenosis remain asymptomatic, while a significant number of patients with minor stenosis progress to symptomatic disease. Therefore, there are factors other than the degree of stenosis that might determine the activity of a carotid lesion. Histopathological analysis of fragments removed by vascular surgery showed a close correlation between plaque morphology and neurological symptoms (transient ischemic attack, minor stroke, and major stroke), depending on the severity and the nature of existing injuries. Patients with “vulnerable plaques” (with surface ulceration, intraplaque hemorrhage, thinner fibrous cap, and rich neovascularization) are prime candidates for stroke by a high risk of embolization and thrombosis [

6]. These vulnerable carotid plaques are characterized by a chronic inflammatory process that develops in the endothelial layer of the arterial wall, involving the influx of the monocytes from the blood, activation and migration of macrophages, development of lipid deposits, smooth muscle proliferation and the appearance of neovascularization [

7,

8].

There is a cause-effect correlation between arterial wall inflammation and neovascularization of the plaque. The inflammatory stimulus leads to the release of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) by smooth muscle cells, with consequent activation of neoangiogenesis within the atherosclerotic plaque. These immature vessels are highly permeable due to reduced gap junctions and thus serve as a port of entry for other inflammatory cells, lipids, and even red blood cells that contribute to plaque growth. At the same time, macrophages secrete metalloproteinases such as MMP-9 and other collagenases that destroy connective fibrous tissue, thereby stimulating neovascular growth - changes that lead to a vulnerable atherosclerotic plaque [

9].

A morphological and immunohistochemistry analysis of the atherosclerotic plaques identified two types of macrophages in the same plaque – M1 pro-inflammatory macrophages with a glycolytic metabolism, which are dominant in the symptomatic tissues and specific for unstable plaques and M2 anti-inflammatory macrophages with an oxidative metabolism which are dominant in the asymptomatic tissues and specific for more stable plaques. The activity of the macrophages influences the progression and regression of the atherosclerotic plaque, each subtype, M1 and M2, having different effector functions. The M1 subtype predominantly expresses iNOS2, whereas the M2 shows more Arg1 positivity. The predominance of one of these subtypes is directly influenced by the immune system cells, especially by the cytokines and growth factors [

10,

11,

12,

13].

Immunohistochemistry studies of atherosclerosis identified the presence of neovascularization in the atherosclerotic plaque and indicated that neoangiogenesis plays a role in the progression and complications of plaques [

14,

15,

16,

17]. Inflammation and macrophage subtypes have been shown to play an essential role in angiogenesis. Plaques with many neoformation vessels are more unstable and prone to rupture, leading to atherothrombotic complications such as intraplaque hemorrhage [

12,

18,

19,

20].

The latest studies identified interactions between the immune cells and vascular smooth muscle cells of the arterial wall, which play a critical role in the initiation, progression, and stabilization of atherosclerotic lesions. Numerous vascular smooth muscle cells around the atherosclerotic lesion provide plaque stability and prevent fibrous cap rupture. The loss of these smooth muscle cells through senescence or apoptosis results in increased macrophage content and necrotic core volume, decreased matrix content, and significant fibrous cap thinning [

21,

22].

The grade of carotid artery stenosis is considered by guidelines the most important criteria in disease classification and determining the indication for endarterectomy. However, recent evidence suggests that the characteristics of atherosclerotic plaque may have a more direct influence on the occurrence of stroke than stenosis alone [

23,

24].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Tissue Fragments

The carotid plaque specimens whose morphological characteristics are processed in this study were obtained by endarterectomy from 119 patients diagnosed with symptomatic carotid artery (CA) stenosis, hospitalized between 2020 and 2022 January at the Vascular Surgery Clinic - County Emergency Clinical Hospital and the Cardiovascular Surgery Clinic - Cardiovascular Disease and Transplant Emergency Institute of Târgu Mureș (Romania). Plaque fragments obtained from the site of maximum stenosis were immediately fixed in 10% buffered formaldehyde, decalcified in ethylene-diamine-tetra-acetic acid (EDTA) solution pH 7, embedded in paraffin, processed by standard histological methods, and evaluated by histopathological examination (

Figure 1).

Based on the results of a previous study [

25], 75 cases with an active perilesional inflammatory infiltrate were selected for further immunohistochemical studies to characterize the monocyte-macrophage component of this mononuclear infiltrate.

Of the 75 re-examined sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), 67 tissue samples were of sufficient quantity and quality for immunohistochemical examination and digital morphometry. The main morphological changes leading to plaque instability were recorded: new vessel formation (angiogenesis), the pattern of calcification (type, position, and extent), presence and structure of the lipid core (lipid-rich large necrotic core or hyaline-rich core), atherothrombosis, intraplaque hemorrhage, fibrous cap damage (with or without parietal thrombus fragments), each scored as present or absent [

25]. We also immunohistochemically characterized the infiltrating macrophages and their subtypes and the density of neovascularization.

2.2. Immunohistochemistry for Macrophage Density, Subtyping, and Detection of Vessel Density in the Atherosclerotic Plaque

Anti-CD68 mouse monoclonal antibody, clone IC70A (Agilent, Dako Santa Clara, CA, USA) was used to identify the macrophage population, followed by iNOS2 positive M1 (clone RBT, BioSB) and Arg-1 M2 (clone EP261, BioSB) subtype specification according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

In parallel with the macrophage study, plaque neovascularization was also assessed using an anti-CD31 antibody (clone 1A10, BioSB) combined with an anti-SMA antibody (clone BSB-15, BioSB). EnVision FLEX/HRP (Agilent, Dako Santa Clara, CA, USA) secondary antibody in combination with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine chromogen (DAB) substrate visualized the reaction product as a brown color. Cell nuclei were counterstained with hematoxylin. As a negative control, normal serum was substituted for the primary antibody. All three immunomarkers we interpreted against positive internal controls for these reactions. Positive controls for CD68 and CD31 reactions were immunolabelled foam cells of the lipid core, endothelial cells of the intima, and endothelium of the vasa vasorum. SMA expression at the level of immature vessels was reported in the immunolabeling of smooth muscle cells of the media.

2.3. Assessment of Intraplaque Neoangiogenesis

The presence or absence of intraplaque neoangiogenesis was initially assessed on H&E-stained sections. Plaques were considered to be revascularised in the presence of small to large, thin-walled, neoformed vessels with dilated or collapsed lumen without or poor smooth muscle cells (

Figure 2a,b). These vessels covered by CD31-positive endothelium often coexist with CD31-positive endothelial cell buds (vascular precursors) (

Figure 2c).

2.4. Semi-Quantitative Scoring of the CD68+ Mononuclear Inflammatory Infiltrate

Based on the density of CD68-labelled macrophages around the plaque, they were classified as low-grade (score 1) or high-grade (score 2-3). Score 1 was considered a reduced CD68+ infiltrate, representing less than 5% of the cellular population around the lipid core examined with ob.4 (

Figure 3a). Score 2 was characterized by immunolabelled cells between 5-10% of the total peri-lesional cell pool (

Figure 3b). If the number of positive cells exceeded 10%, the case was classified as score 3 (

Figure 3c). To accurately characterize the abundance of macrophages, we quantified immunolabeling by determining the positive surface area using a digital morphometry method.

2.5. Digital Image Analysis Method to Measure Quantitative Individual Plaque Characteristics (CD68, Arg1, iNOS2, CD31)

A total of 242 microphotographs were obtained from representative regions containing the most cells or vascular elements detected by immunolabelling (hot-spot method) at 10× magnification using the AxioLab5 microscope connected to the Zeiss AxioCam 8 digital camera (

Figure 4).

Quantitative analysis of all carotid plaque images was performed using Image J software (Image J 2 for macOS, version 2.3.0, NIH, National Institute of Health, Bethesda, Maryland, USA). Images were imported into the ImageJ software. The percentage of CD68, iNOS2, Arg1, and CD31 positive cells was calculated relative to the total area of the imaged area (positive relative area). For the Arg1/iNOS2 composition, we defined a cut-off value of 1 and classified our cases into Arg1 dominant and iNOS2 dominant cases (

Figure 5).

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Categorical and transformed continuous variables were assessed for absolute and relative distribution frequencies. Analysis of 2x2 or 3x2 contingency tables was performed using Fisher’s exact test and Pearson 2 test. Non-linear logistic regression models were used to predict ulceration and atherothrombosis. In all tests, P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Data were processed using Microsoft Excel 2016 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and GraphPad Prism 10.0 (GraphPad Software LLC., San Diego, CA, USA).

3. Results

3.1. Study Group Characteristics

A total of 67 cases (47 men and 20 women) with a mean age of 65 years were included. All patients had severe carotid stenosis (>70%). Bilateral carotid involvement was diagnosed in 23 (34.3%) patients; 60 (89.5%) had hypertension at the time of admission, 55 (82.1%) also had coronary artery disease, 11 (16.4%) had associated peripheral arterial disease, and in 16 of them were involved of two or three arterial beds (carotid, coronary, limb). Sixteen patients had diabetes (type II, 23.9%), and all but one had some form of dyslipidemia (total cholesterol >200 mg/dL, serum triglycerides >150 mg/dL). 14 cases had neutrophilia (PMNs > 7.0x 10

9/L), 3 lymphocytosis (LYMPHs > 3.5x 10

9/L) and 9 monocytosis (MONOs > 900x 10

9/L) (

Table 1).

3.2. Histological Signs of the Complicated Plaque

Most specimens had a large lipid core (82%), while 59% showed ulceration, 54% intraplaque hemorrhage, and 19% atherothrombosis. Microcalcifications were present in 53%, while macrocalcifications in 25% of the samples (

Table 1).

3.3. Correlation of the CD68+ Infiltrate grade with Signs of Plaque Complication

Macrophage density in the non-core lesion area was scored as previously described and expressed as weak (score 1) or strong (score 2, 3) infiltrate. In a 2x2 contingency analysis, these categories did not show significantly different distributions for ulceration, thrombosis, and neovascularization. However, CD68+ scores 2/3 were significantly more associated with intraplaque hemorrhage than score 1 (p = 0.003), with 24 cases (60%) in the first group and only six patients (23%) in the second group (

Table 2).

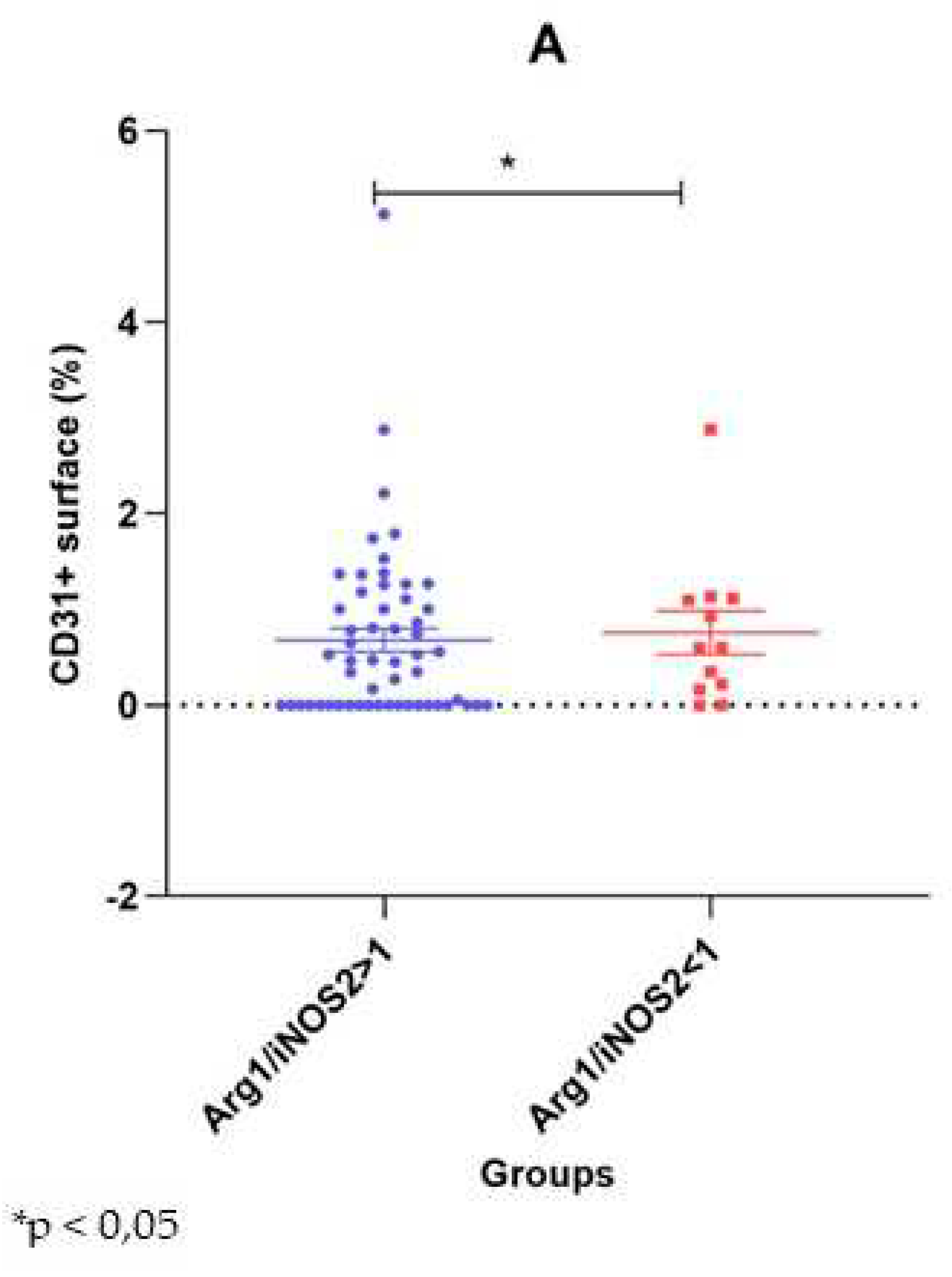

3.4. Comparison of the Arg1 Dominant vs. the iNOS2 Dominant Groups

We used digital morphometry to assess CD68+ macrophages as the main elements of the cellular infiltrate. We also quantified the Arg1+ and iNOS2+ surface area within the “inflammatory hotspot” to determine the dominance of the M2 or M1 subtype. We defined a cut-off value one and divided our cases into Arg1-dominant (n=55) and iNOS2-dominant (n=12) cases. The two groups showed a significant difference in the occurrence of atherothrombosis (p = 0.046), with the iNOS2+ dominant specimens presenting this complication more frequently (41.7% vs. 14.5%). None of the other plaque characteristics showed a significantly different distribution between the groups. The CD68+ surface was almost the same in both groups (1.38%- Arg-1 dominant vs. 1.33%- iNOS2 dominant). The absolute numbers of neutrophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and the neutrophil/lymphocyte ratio were comparable between the groups (

Table 3).

3.5. Correlation of Neovascularization with Other Histological Signs of Plaque Instability

Perilesional inflammation was associated with plaque neovascularization in only 41 cases. In these cases, neovascularization, observed as the presence of newly formed intraplaque microvessels, was associated with a significantly higher CD31+ surface area than in 26 samples without this phenomenon (1.07 ± 0.14% vs. 0.05 ± 0.05%, p<0.001). Ulceration (n=40) and hemorrhage-positive plaques (n=30) had slightly, but not significantly, higher values of CD31+ surface area than their negative counterparts (0.72 ± 0.16% vs. 0.61 ± 0.11%, p = 0.607 and 0.69 ± 0.20% vs. 0.66 ± 0.11%, p=0.324). In contrast, in the 13 plaques with atherothrombosis, the CD31 positive area was significantly higher than in the plaques without atherothrombosis (1.02 ± 0.20 vs. 0.61 ± 0.12, p = 0.020) (

Figure 6).

4. Discussion

In this large-cohort study of endarterectomy specimens obtained from patients with symptomatic stenosis, we have provided a detailed oversight of the inflammatory composite elements that make up the ulcerated hemorrhagic and potentially unstable micro-environment within what are essentially heterogeneous atherosclerotic plaques. With these findings, we can further define the relationship between active macrophage infiltration, the neoangiogenic processes, and potential thrombotic capacity within the developing intimal core.

The co-expression of immature irregular and leaky intimal microvessels has previously been linked to the development of ‘soft’ inflammatory and foam cell-loaded plaques susceptible to rupture [

7,

8]. This is often associated with significant inflammatory infiltrate concomitant with extracellular matrix breakdown and thinning of the protective fibrous cap. Here, we have characterized the expression of CD68-positive macrophages within the intimal cores of studied plaques, showing that higher macrophage presence was associated with more evidence of plaque hemorrhage, and more specifically, in these inflammatory ‘hotspots,’ where there was evidence of atherothrombosis, M1 macrophages (designated by staining with anti-iNOS-2), were the predominant phenotype [

10,

13].

These results suggest the importance of monitoring plaque inflammatory activity and possibly chronic systemic inflammation in at-risk patients. Several studies have indicated that blocking macrophage activity in vivo could help stabilize and slow down the growth of arterial plaques. For example, Tang et al. used nanoparticles to direct simvastatin to infiltrate regions in ApoE4 mice, successfully blocking macrophage proliferation and slowing plaque growth [

26]. Li et al. summarized the importance of M1 macrophages as instigators of plaque progression, suggesting the possibility of their use as a clinical biomarker [

27].

In general, angiogenesis seen within growing plaques indicates instability and likely hemorrhage. Evidence has shown that endothelial cells of neointimal vessels can originate following activation and trans-migration of vasa vasorum of the adventitia. Hence, strong pro-inflammatory signaling from macrophage-rich microenvironments could be the switch that instigates this [

28]. In this study, microvessels from the intima showed heterogeneous size, shape, and patency, some bearing stabilizing smooth muscle cells. The frequency was correlated with atherothrombotic regions.

One limitation of this study was that we did not characterize the currently active microvessels using antibodies such as CD105. Further studies should aim to examine in more detail the relationship between actively growing immature vessels, macrophage phenotype, and local secretion of matrix destabilizing proteins. Future targeting of arterial ‘hotspots’ encouraging fibrous proliferation might be one therapeutic mechanism to stabilize potentially thrombotic intimal zones [

29], while macrophage M1-radiolabelled tracers could support enhanced imaging to identify vulnerable regions at risk of thrombosis [

30].

5. Conclusions

In this study, we focused on the carotid atherosclerotic plaques with an active perilesional inflammatory infiltrate and correlation with their histological and immunochemistry signs specific for unstable plaques: ulceration, thrombosis, intraplaque hemorrhage, lipid core, calcification, and neovascularization.

Our results release the following aspects about inflammatory atherosclerotic plaques of patients with severe carotid stenosis: (1) Most of the plaques had a large lipid core, while ulceration, intraplaque hemorrhage, microcalcifications were present in more than 50% of the cases, (2) massive infiltrate with macrophage in the non-core lesion area was associated with intraplaque hemorrhage, (3) M2 subtype of macrophage was the dominant one in our specimens and this was associated with atherothrombosis, (4) absolute neutrophil, lymphocyte, monocyte counts and neutrophil/lymphocyte ratios were comparable between M1 and M2 dominant groups, (5) plaque neovascularization identified with CD31+ high areas were correlated with atherothrombosis.

Based on our results, we hypothesize that even if we have carotid plaques that create high-grade artery stenosis, their complications, specific to the unstable plaques, may appear and lead to neurological disorders like transient ischemic attack or stroke. Further, multidisciplinary studies are needed to prevent the development of complications from carotid atherosclerotic inflammatory plaques.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.H., I.A.B. and E.E.N.; data curation, I.A.B., A.V.M., H.S.,A.M. and E.H.; methodology, E.H., I.A.B., K.B., G.B.M. and E.E.N.; investigation, I.A.B., A.V.M., E.H. H.S., A.M. and G.B.M.; statistical analysis, E.E.N.; writing—original draft preparation, E.H., I.A.B., E.E.N. and M.S.; supervision, M.S.; writing—review and editing, E.H., K.B., E.E.N., and M.S.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the Ethics Committee of the George Emil Palade University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Science and Technology, Targu Mures (no. 906/2020) and by the Institutional Review Board of the County Emergency Clinical Hospital, Targu Mures (no. 29496/2019) and the Cardiovascular Disease and Transplantation Emergency Institute, Targu Mures (no. 1680/2020). Written informed consent was obtained from each patient included in this study.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from each patient involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the vascular and cardiovascular surgeons of the Vascular Surgery Clinic - County Emergency Clinical Hospital and the Cardiovascular Surgery Clinic - Cardiovascular Disease and Transplantation Emergency Institute of Targu Mureș (Romania) for their help in patient recruitment. The authors thank Genoveva Rigmanyi (Center for Advanced Medical and Pharmaceutical Research, George Emil Palade University of Medicine, Pharmacy, Science, and Technology of Targu Mures) for expert technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Devi, M.K.; Kuruvilla, S.; Balakrishnan, K.R. Expression of Inflammatory Markers CD68 and SMA in Endarterectomy Speci.

- mens. Austin J Clin Pathol. 2018; 5(2): 1057.

- Katan, M.; Luft, A. Global burden of stroke. Seminars in Neurology 2018, 38(02), 208–211.

- Messas, E.; Goudot, G.; Halliday, A.; Sitruk, J.; Mirault, T.; Khider, L.; Saldmann, F.; Mazzolai, L.; Aboyans, V. Management of carotid stenosis for primary and secondary prevention of stroke: State-of-the-art 2020: A critical review. European Heart Journal Supplements 2020, 22(Supplement_M). [CrossRef]

- Tsao, C. W.; Aday, A. W.; Almarzooq, Z. I.; Alonso, A.; Beaton, A. Z.; Bittencourt, M. S.; Boehme, A. K.; Buxton, A. E.; Carson, A. P.; Commodore-Mensah, Y.; Elkind, M. S. V.; Evenson, K. R.; Eze-Nliam, C.; Ferguson, J. F.; Generoso, G.; Ho, J. E.; Kalani, R.; Khan, S. S.; Kissela, B. M.; et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2022 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022, 145(8). [CrossRef]

- Finn, C., Giambrone, A. E., Gialdini, G., Delgado, D., Baradaran, H., Kamel, H., & Gupta, A. (2017). The Association between Carotid Artery Atherosclerosis and Silent Brain Infarction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of stroke and cerebrovascular diseases: the official journal of National Stroke Association, 26(7), 1594–1601. [CrossRef]

- Saba, L.; Agarwal, N.; Cau, R.; Gerosa, C.; Sanfilippo, R.; Porcu, M.; Montisci, R.; Cerrone, G.; Qi, Y.; Balestrieri, A.; Lucatelli, P.; Politi, C.; Faa, G.; Suri, J. S. Review of imaging biomarkers for the vulnerable carotid plaque. JVS-Vascular Science 2021, 2, 149–158. [CrossRef]

- Geiger, M. A.; Flumignan, R. L.; Sobreira, M. L.; Avelar, W. M.; Fingerhut, C.; Stein, S.; Guillaumon, A. T. Carotid plaque composition and the importance of non-invasive in imaging stroke prevention. Frontiers in Cardiovascular Medicine 2022, 9. [CrossRef]

- Withana, N. P.; Saito, T.; Ma, X.; Garland, M.; Liu, C.; Kosuge, H.; Amsallem, M.; Verdoes, M.; Ofori, L. O.; Fischbein, M.; Arakawa, M.; Cheng, Z.; McConnell, M. V.; Bogyo, M. Dual-modality activity-based probes as molecular imaging agents for vascular inflammation. Journal of Nuclear Medicine 2016, 57(10), 1583–1590. [CrossRef]

- Varetto, G.; Gibello, L.; Castagno, C.; Quaglino, S.; Ripepi, M.; Benintende, E.; Gattuso, A.; Garneri, P.; Zan, S.; Capaldi, G.; Bertoldo, U.; Rispoli, P. Use of contrast-enhanced ultrasound in carotid atherosclerotic disease: Limits and Perspectives. BioMed Research International 2015, 2015, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Dolfi, B.; Gallerand, A.; Haschemi, A.; Guinamard, R. R.; Ivanov, S. Macrophage metabolic regulation in atherosclerotic plaque. Atherosclerosis 2021, 334, 1–8. [CrossRef]

- Forteza, M. J.; Ketelhuth, D. F. J. Metabolism in atherosclerotic plaques: Immunoregulatory mechanisms in the arterial wall. Clinical Science 2022, 136(6), 435–454. [CrossRef]

- Moroni, F.; Ammirati, E.; Norata, G. D.; Magnoni, M.; Camici, P. G. The role of monocytes and macrophages in human atherosclerosis, plaque neoangiogenesis, and atherothrombosis. Mediators of Inflammation 2019, 2019, 1–11. [CrossRef]

- de Gaetano, M.; Crean, D.; Barry, M.; Belton, O. M1- and M2-type macrophage responses are predictive of Adverse Outcomes in human atherosclerosis. Frontiers in Immunology 2016, 7. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, P. R.; Purushothaman, K.-R.; Sirol, M.; Levy, A. P.; Fuster, V. Neovascularization in human atherosclerosis. Circulation 2006, 113(18), 2245–2252. [CrossRef]

- Geiringer, E. Intimal vascularisation and atherosclerosis. The Journal of Pathology and Bacteriology 1951, 63(2), 201–211.

- Sueishi, K.; Yonemitsu, Y.; Nakagawa, K.; Kaneda, Y.; Kumamoto, M.; Nakashima, Y. Atherosclerosis and angiogenesis: Its pathophysiological significance in humans as well as in an animal model induced by the gene transfer of Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1997, 811(1 Atheroscleros), 311–324.

- Camaré, C.; Pucelle, M.; Nègre-Salvayre, A.; Salvayre, R. Angiogenesis in the atherosclerotic plaque. Redox Biology 2017, 12, 18–34. [CrossRef]

- Virmani, R.; Kolodgie, F. D.; Burke, A. P.; Finn, A. V.; Gold, H. K.; Tulenko, T. N.; Wrenn, S. P.; Narula, J. Atherosclerotic plaque progression and vulnerability to rupture: angiogenesis as a source of intraplaque hemorrhage. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2005, 25(10), 2054–2061.

- Kolodgie, F. D.; Gold, H. K.; Burke, A. P.; Fowler, D. R.; Kruth, H. S.; Weber, D. K.; Farb, A.; Guerrero, L. J.; Hayase, M.; Kutys, R.; Narula, J.; Finn, A. V.; Virmani, R. Intraplaque hemorrhage and progression of coronary atheroma. New England Journal of Medicine 2003, 349(24), 2316–2325. [CrossRef]

- Li, A. C.; Glass, C. K. The macrophage foam cell as a target for therapeutic intervention. Nature Medicine 2002, 8(11), 1235–1242. [CrossRef]

- Ramel, D.; Gayral, S.; Sarthou, M.-K.; Augé, N.; Nègre-Salvayre, A.; Laffargue, M. Immune and smooth muscle cells interactions in atherosclerosis: How to target a breaking bad dialogue? Frontiers in Pharmacology 2019, 10.

- Doran, A. C.; Meller, N.; McNamara, C. A. Role of smooth muscle cells in the initiation and early progression of atherosclerosis. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2008, 28(5), 812–819. [CrossRef]

- Naylor, R.; Rantner, B.; Ancetti, S.; de Borst, G.J.; De Carlo, M.; Halliday, A.; et al. Editor’s Choice – European Society for Vascular Surgery (ESVS) 2023 clinical practice guidelines on the management of atherosclerotic carotid and vertebral artery disease. European Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 2023, 65(1), 7–111. [CrossRef]

- Saba, L.; Saam, T.; Jäger, H. R.; Yuan, C.; Hatsukami, T. S.; Saloner, D.; Wasserman, B. A.; Bonati, L. H.; Wintermark, M. Imaging biomarkers of vulnerable carotid plaques for stroke risk prediction and their potential clinical implications. The Lancet Neurology 2019, 18(6), 559–572. [CrossRef]

- Balmos, I. A.; Horváth, E.; Brinzaniuc, K.; Muresan, A. V.; Olah, P.; Molnár, G. B.; Nagy, E. E. Inflammation, microcalcification, and increased expression of osteopontin are histological hallmarks of plaque vulnerability in patients with advanced carotid artery stenosis. Biomedicines 2023, 11(3), 881. [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Lobatto, M. E.; Hassing, L.; van der Staay, S.; van Rijs, S. M.; Calcagno, C. et al. Inhibiting macrophage proliferation suppresses atherosclerotic plaque inflammation. Science advances 2015, 1(3), e1400223. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Cao, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, C.; Lin, H.; Tang, Y.; Yao, P. Macrophage Subsets and Death Are Responsible for Atherosclerotic Plaque Formation. Frontiers in immunology 2022, 13, 843712. [CrossRef]

- Slevin, M.; Krupinski, J.; Badimon, L. Controlling the angiogenic switch in developing atherosclerotic plaques: possible targets for therapeutic intervention. Journal of angiogenesis research 2009, 1, 4. [CrossRef]

- Sedding, D. G.; Boyle, E. C.; Demandt, J. A. F.; Sluimer, J. C.; Dutzmann, J.; Haverich, A.; Bauersachs, J. Vasa Vasorum Angiogenesis: Key Player in the Initiation and Progression of Atherosclerosis and Potential Target for the Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease. Frontiers in immunology 2018, 9, 706. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.; Otaki, Y.; Doris, M.; Slipczuk, L.; Arnson, Y.; Rubeaux, M.; Dey, D.; Slomka, P.; Berman, D. S.; Tamarappoo, B. Molecular Imaging of Vulnerable Coronary Plaque: A Pathophysiologic Perspective. Journal of nuclear medicine: official publication, Society of Nuclear Medicine 2017, 58(3), 359–364. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Representative atherosclerotic plaque fragments obtained by endarterectomy from a patient with unstable carotid plaques, processed and fully examined, characterized by complex morphology and composition (H&E stain, original magnification).

Figure 1.

Representative atherosclerotic plaque fragments obtained by endarterectomy from a patient with unstable carotid plaques, processed and fully examined, characterized by complex morphology and composition (H&E stain, original magnification).

Figure 2.

(a) SMA-immunostained carotid artery wall fragment affected by atherothrombosis at the level of the plaque with a proliferation of newly formed vessels ranging from microvessels (with reduced/collapsed lumen) to dilated branching vessels with irregular lumen (circled). (b) These immature and dysmorphic vessels lack SMA-positive smooth muscle cells (blue arrows) or show discontinuity of SMA-positive immunolabelled coverage (red arrows). (Immunolabel was reported to be positive for endogenous control on media and myofibroblasts within the plaque, visualized by 3,3’-diaminobenzidine chromogen, 10x magnification). (c) Revascularized plaque with small to large, thin-walled, neovascularized vessels covered by CD31-positive endothelium (blue arrows). Immature vascular elements in the form of endothelial cell buds (red arrows) can also be observed (CD31 immunohistochemistry in combination with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine chromogen, original magnification x 4).

Figure 2.

(a) SMA-immunostained carotid artery wall fragment affected by atherothrombosis at the level of the plaque with a proliferation of newly formed vessels ranging from microvessels (with reduced/collapsed lumen) to dilated branching vessels with irregular lumen (circled). (b) These immature and dysmorphic vessels lack SMA-positive smooth muscle cells (blue arrows) or show discontinuity of SMA-positive immunolabelled coverage (red arrows). (Immunolabel was reported to be positive for endogenous control on media and myofibroblasts within the plaque, visualized by 3,3’-diaminobenzidine chromogen, 10x magnification). (c) Revascularized plaque with small to large, thin-walled, neovascularized vessels covered by CD31-positive endothelium (blue arrows). Immature vascular elements in the form of endothelial cell buds (red arrows) can also be observed (CD31 immunohistochemistry in combination with 3,3’-diaminobenzidine chromogen, original magnification x 4).

Figure 3.

Scoring of the density of CD68 labeled monocytes/macrophages around the plaque. (a) Score 1: few positive CD68 cells representing less than 5% of the cell population around the lipid core (marked with a red star). (b) Score 2: immunolabelled cells between 5-10% of the total perilesional cell pool. Score 3: number of positive cells greater than 10%. (c) CD68/3,3’-diaminobenzidine chromogen immunohistochemistry, original magnification ×4.

Figure 3.

Scoring of the density of CD68 labeled monocytes/macrophages around the plaque. (a) Score 1: few positive CD68 cells representing less than 5% of the cell population around the lipid core (marked with a red star). (b) Score 2: immunolabelled cells between 5-10% of the total perilesional cell pool. Score 3: number of positive cells greater than 10%. (c) CD68/3,3’-diaminobenzidine chromogen immunohistochemistry, original magnification ×4.

Figure 4.

(a) Hotspot method: Choice and annotation of the most representative regions containing the most immunolabelled elements (original magnification x2). (b) CD68 positive mononuclear cell density in the area selected for digital image analysis (CD68/3,3’-diaminobenzidine chromogen combination, original magnification x 10).

Figure 4.

(a) Hotspot method: Choice and annotation of the most representative regions containing the most immunolabelled elements (original magnification x2). (b) CD68 positive mononuclear cell density in the area selected for digital image analysis (CD68/3,3’-diaminobenzidine chromogen combination, original magnification x 10).

Figure 5.

Detection of pro-inflammatory (M1) and anti-inflammatory (M2) monocyte/macrophage subsets in histological regions corresponding to highly reactive cell pools. Arg1+ (a) versus iNOS2+ (b) cells within the “inflammatory hotspot.” Visualization by immunohistochemistry (3,3’-diaminobenzidine chromogen, original magnification x 4).

Figure 5.

Detection of pro-inflammatory (M1) and anti-inflammatory (M2) monocyte/macrophage subsets in histological regions corresponding to highly reactive cell pools. Arg1+ (a) versus iNOS2+ (b) cells within the “inflammatory hotspot.” Visualization by immunohistochemistry (3,3’-diaminobenzidine chromogen, original magnification x 4).

Figure 6.

Dot-plot representation of the intraplaque CD31+ surface area by the Arg1 and iNOS2 dominant groups. Values are represented as percentages, mean ± SE. *p < 0,05.

Figure 6.

Dot-plot representation of the intraplaque CD31+ surface area by the Arg1 and iNOS2 dominant groups. Values are represented as percentages, mean ± SE. *p < 0,05.

Table 1.

Demographic factors, atherosclerotic plaque characteristics, immunohistochemistry parameters, complete blood count parameters.

Table 1.

Demographic factors, atherosclerotic plaque characteristics, immunohistochemistry parameters, complete blood count parameters.

| Demographic factors |

|

| Age (years) |

65.4 ± 1.1 |

| Gender (male/female) |

47 (70.1)/ 20 (29.9) |

| Plaque characteristics |

|

| Ulceration (yes/no) |

40 (59.7) / 27 (40.3) |

| Atherothrombosis (yes/no) |

13 (19.4) / 54 (80.6) |

| Intraplaque hemorrhage (yes/no) |

30 (54.5) / 37 (45.5) |

| Lipid core (yes/no) |

55 (82.1) / 12 (17.9) |

| Microcalcification (yes/no) |

36 (53.7) / 31 (46.3) |

| Superficial/deep calcification (yes/no) |

25 (37.3) / 42 (62.7) |

| Macrocalcification (yes/no) |

17 (25.3) / 50 (74.7) |

| Neovascularization (yes/no) |

41 (61.2) / 26 (38.8) |

| Immunohistochemistry parameters |

Positive surface area |

| CD68+ surface (%) |

1.37 ± 0.14 |

| iNOS2 + surface (%) |

0.48 ± 0.08 |

| Arg1 + surface (%) |

1.79 ± 0.20 |

| CD31 + surface (%) |

0.69 ± 0.10 |

| Complete blood count parameters |

|

| Neutrophils (109/L) |

5.89 ± 0.28 |

| Lymphocytes (109/L) |

2.11 ± 0.09 |

| Neutrophil/Lymphocyte ratio |

3.38 ± 0.67 |

| Monocytes (109/L) |

0.76 ± 0.08 |

Table 2.

Correlation of the CD68+ infiltrate grade with plaque complication.

Table 2.

Correlation of the CD68+ infiltrate grade with plaque complication.

| |

CD68+ Infiltrate Density |

|

| |

Score 1 |

Score 2-3 |

p Value |

| Ulceration (yes/no) |

14/12 |

26/14 |

0.318 |

| Atherothrombosis (yes/no) |

5/21 |

8/32 |

1 |

| Intraplaque hemorrhage(yes/no) |

6/20 |

24/16 |

0.003 |

| Neovascularization (yes/no) |

18/9 |

23/17 |

0.609 |

Table 3.

Correlation of Arg1+ and iNOS2+ with demographic factors, plaque complications, and complete blood count characteristics.

Table 3.

Correlation of Arg1+ and iNOS2+ with demographic factors, plaque complications, and complete blood count characteristics.

| Groups |

Arg1/iNOS2≥1

(n=55) |

Arg1/iNOS2<1

(n=12) |

p Value |

| Demographic factors |

|

|

|

| Age (years) |

65.5 ± 1.2 |

64.8 ± 1.9 |

|

| Gender (male/female) |

36 (65.5) / 19 (34.5) |

11 (91.6) / 1 (8.4) |

0.090 |

| Plaque characteristics |

|

|

|

| Ulceration (yes/no) |

33 (60) / 22 (40) |

7 (58.3)/ 5 (41.7) |

0.990 |

| Atherothrombosis (yes/no) |

8 (14.5) / 47 (85.5) |

5 (41.7) / 7 (58.3) |

0.046 |

| Intraplaque hemorrhage (yes/no) |

23 (41.8) / 32 (58.2) |

7 (58.3) / 5 (41.7) |

0.348 |

| Lipid core (yes/no) |

45 (81.8) / 10 (18.2) |

10 (83.3) / 2 (16.6) |

1.000 |

| Microcalcification (yes/no) |

29 (52.7) / 26 (47.3) |

7 (58.3) / 5 (41.7) |

0.760 |

| Superficial/deep calcification(yes/no) |

19 (34.5) / 36 (65.5) |

6 (50) / 6 (50) |

0.345 |

| Macrocalcification (yes/no) |

13 (23.6) / 42 (76.4) |

4 (33.3) / 8 (66.6) |

0.482 |

| Neovascularization (yes/no) |

31 (56.3) / 24 (43.7) |

10 (83.3) / 2 (16.6) |

0.108 |

| CD68 + area (%) |

1.38 ± 0.16 |

1.33 ± 0.35 |

0.740 |

| CD31 + area (%) |

0.68 ± 0.12 |

0.75 ± 0.23 |

0.502 |

Complete blood count

parameters

|

|

|

|

| Neutrophils (109/L) |

5.72 ± 0.29 |

6.65 ± 0.78 |

0.226 |

| Lymphocytes (109/L) |

2.08 ± 0.09 |

2.24 ± 0.23 |

0.491 |

| Neutrophil/Lymphocyte ratio |

3.27 ± 0.36 |

3.38 ± 0.67 |

0.692 |

| Monocytes (109/L) |

0.64 ± 0.03 |

0.76 ± 0.08 |

0.245 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).