1. Introduction

The advancement of automation systems and the integration of IoT technology are ushering in a transformative era for maritime operations [

1]. This paradigm shift has given rise to innovative ship operations, including smart ships, remote operating vessels, and digital twin ships [

2,

3]. Recognizing the potential of these technological strides, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) has actively engaged in discussions around the safe operation of Maritime Autonomous Surface Ships (MASS). These vessels are defined as capable of navigating surface waters with minimal or no human intervention and are categorized into four stages based on their degree of automation [

4].

The increasing recognition of MASS underscores the need to address critical challenges surrounding data sharing, communication [

5], and interoperability between ships and onshore operations [

6]. Efficient data management, real-time monitoring, and informed decision-making are paramount for enhancing safety, operational efficiency, and performance in autonomous maritime environments [

7].

To this end, a robust and versatile IoT-based cloud data platform that can interact with ship automation systems already in place on ships and develop new services is essential. This paper presents a novel cloud-based horizontal data platform structure specifically tailored to support multiple services in the maritime field, utilizing IoT data collected from ships. The horizontal data platform enables multiple ships and services to operate organically on a single unified platform [

8]. By leveraging a common ship data collection infrastructure, new services can be effortlessly integrated by adjusting relevant architectural elements within the horizontal slice.

Ships traverse the globe, and the companies overseeing these vessels are distributed worldwide. This extensive geographical distribution poses challenges in maintaining consistent service quality through a single cloud infrastructure. To address these challenges, this paper introduces a platform comprising multiple Fog Clouds and a single global Cloud Center. The innovative data collection and sharing infrastructure of this platform enable the Edge Server, responsible for collecting and managing ship data, to interact with the Fog Cloud in the region with the most optimal latency. Data gathered from the Fog Cloud is efficiently transferred and managed within the Cloud Center, providing a standardized data structure and interface that simplifies the development of new services. The overarching goal of this platform is to empower IoT systems aboard ships navigating the globe, allowing seamless data sharing, utilization for various services, and effective collaboration with onshore services. This approach is vital for unlocking the multifaceted adaptability required for the realization of MASS.

Fog computing paradigms have gained significant popularity as effective ways to maximize the efficient utilization of resources offered by IoT devices. These paradigms not only extend the quality of service to the immediate vicinity of the user but also enable rapid processing within the dynamic IoT-cloud ecosystems [

9]. Numerous studies in the maritime sector, including ships, are actively exploring the efficient collection of data through fog computing and optimizing functions through offloading [

10,

11].

This paper focuses on the design and implementation of a platform tailored for efficient distribution and utilization of services. The stakeholders for this endeavor include service developers involved in MASS initiatives, operational monitoring for sizable ships with worldwide routes, and shipping enterprises entrusted with ship management functions. Chapter 3 outlines the platform structure, which consists of four tiers, encompassing multiple Multi-Region Fog Clouds spanning the globe. This chapter defines the scope of services and their intended users for each tier. Furthermore, it highlights the potential for impactful technological advancements in the maritime sector, offering solutions such as ship collision avoidance, route optimization based on weather data, and the construction of a digital twin-based OTS (Operator Training System) environment within this platform structure.

Chapter 4 proposes an architecture for the implementation of the aforementioned platform using AWS, a prominent public cloud provider. It includes tests designed to measure Round-Trip Time (RTT) and Packet Loss Rate (PLR) across different regions, aiming to assess the extent and unique characteristics of network benefits achievable within the same region.

2. Related Work

Over the past decade, substantial research has been undertaken under the topics of "e-navigation" and "MASS," focusing on automating ship operation and management. These researches mainly use IoT technology in maritime field, leading to significant advancements in Ship Operation Technology (OT) by merging it with Information Technology (IT). This fusion has given rise to the development of numerous automated systems with the explicit goal of minimizing the need for extensive human intervention.

One area of ongoing research focuses on collision avoidance measures for safe navigation [

12]. This research is instrumental in preparing for the autonomous ship era, seeking to minimize human involvement in navigation processes. Additionally, studies are actively exploring ways to enhance existing functions or create novel services through the sharing and effective management of data, facilitated by communication between ships or ship-to-onshore interactions [

6].

Furthermore, notable recent efforts have been dedicated to laying the groundwork for MASS. This involves the seamless integration of the ship's automation system with onshore solutions, achieved through a cloud-based platform. This platform serves as a critical bridge, enabling efficient data exchange and collaborative interactions between ships and onshore entities, contributing to the realization of autonomous ship capabilities [

10,

11].

2.1. Ship Automation System

The ship's automation system plays a crucial role in aiding users in making informed decisions by collecting and conveying operational data, while also integrating control components to ensure the ship adheres to these decisions.

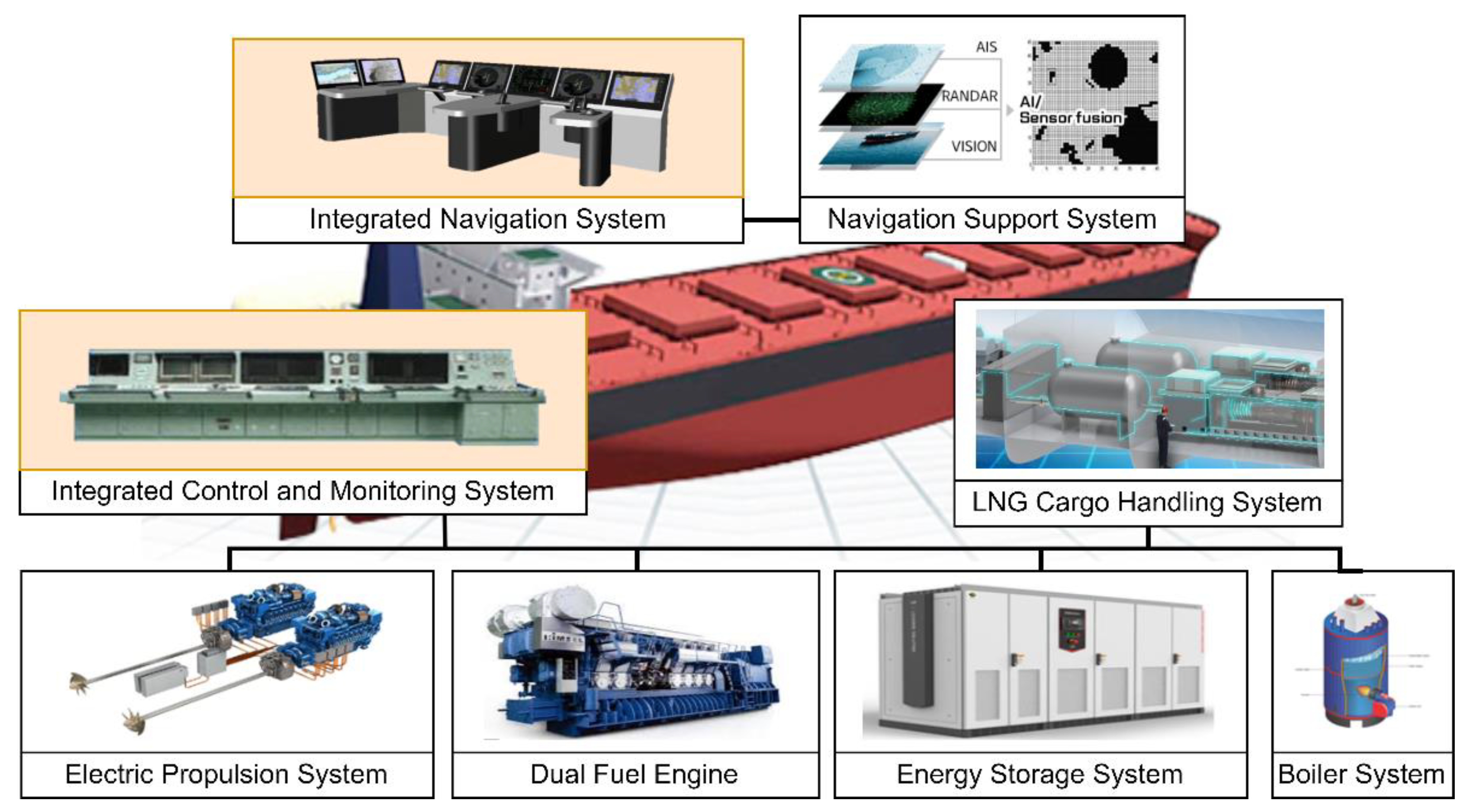

Figure 1 illustrates a comprehensive configuration consisting of two essential systems: The Integrated Navigation System (INS) for ship navigation and the Integrated Control and Monitoring System overseeing control of onboard facilities. Within the INS, critical unit systems like the Electronic Chart Display Information System (ECDIS), RADAR, Track Control System (TCS), Bridge Alarm Monitoring System (BAMS), and Autopilot work harmoniously, playing vital roles in planning and executing the ship's route. The INS follows the IEC61924-2 standard, precisely defining its modular structure and performance criteria, ensuring the monitoring of connected sensor availability, effectiveness, and integrity [

13].

While traditional INS systems mainly support human decision-making by visualizing data, ongoing research aims to minimize human intervention and empower the system to navigate autonomously by perceiving its surroundings. Studies focus on developing stable algorithms, guidance, and control mechanisms for collision avoidance, with the goal of significantly enhancing the system's capability to effectively avert potential collisions [

14,

15].

The ship is equipped with an Integrated Control and Monitoring System (ICMS), serving as a distributed control system responsible for

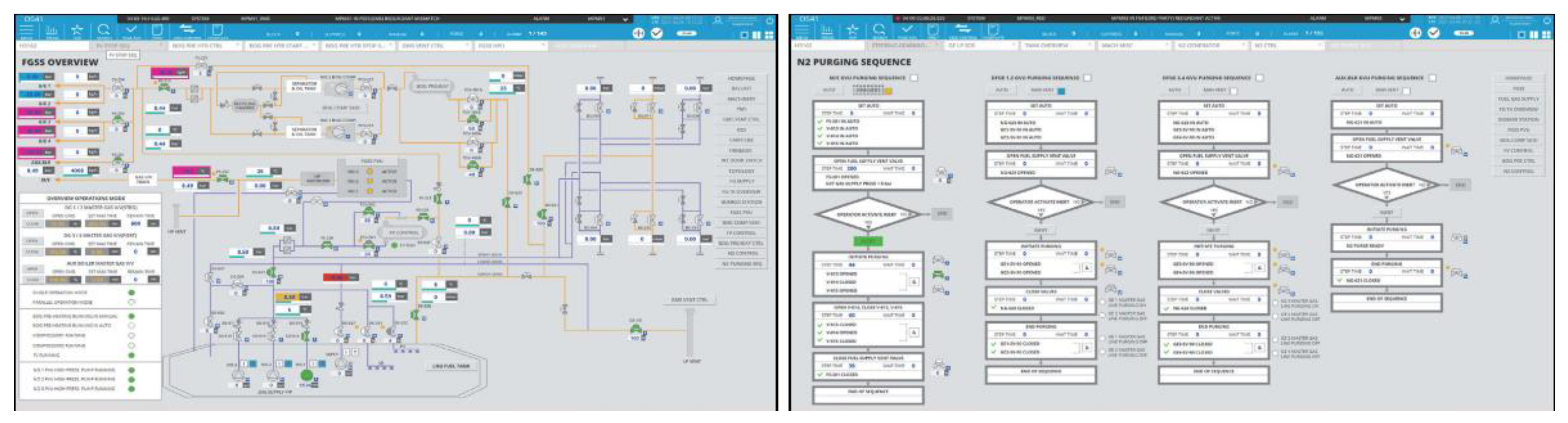

Figure 2 provides an illustrative example, depicting a process diagram screen displaying the Fuel Gas Supply System, which is under the control of the ICMS. This Human Machine Interface (HMI) allows operators to monitor the status and conditions of the control elements via the screen, and it facilitates automated sequencing for efficient control of these elements. The rising demand for eco-friendly ships, such as LNG carriers, electric propulsion vessels, and Dual Fuel Engine ships, has introduced greater complexity and diversity of control factors within the ICMS. To address these advancements, dedicated research efforts are concentrated on creating an environment that supports the swift and secure development of sophisticated ships and control technologies, leveraging digital twin technology [

16]. Furthermore, ongoing studies aim to integrate and optimize systems through virtual simulation environments [

17]. However, to transform these research activities into tangible outcomes and effectively implement them on actual ships, the existence of a real-time data platform seamlessly connecting and managing ship data is imperative.

2.2. Generation and Propagation of Ship Navigation Data

The ship's navigation-related sensor data is generated following the IEC61162-1 standard [

18] in the case of serial communication and the IEC61162-450 standard [

19] for Ethernet communication, which has been expanded to handle various types of data. Automatic Identification System (AIS) extracts the data generated by these protocols and disseminates messages containing the location and voyage information of the ship to surrounding vessels over the Very High Frequency (VHF) frequency. The transmission period is shorter for faster vessels, ensuring neighboring ships can promptly and safely detect them.

The AIS data encompasses different categories based on message types [

20]. Among these, the message types directly related to navigation status are 1, 2, and 3, allowing ships to gain insight into the current navigation status and the locations of surrounding vessels through the distribution of these messages. Additionally, AIS transmits the data it sends and receives to the INS network using a standard protocol based on IEC61161-1, enabling navigation equipment to comprehend the surrounding context and display relevant data to users.

Numerous ongoing studies are actively striving to enhance the operational and management performance of ships through the effective utilization of AIS data. In [

21], researchers integrated AIS data to cluster ship trajectories, suggesting its potential use in collision avoidance by predicting ship paths. In [

22], a preprocessing technique was proposed to manage and analyze the substantial quantities of AIS data collected. This technique aimed to enhance data management performance and route monitoring capabilities. Recognizing the limitations imposed by the limited transmission distance of AIS data through VHF due to Earth's curvature, research is underway to harness satellites for collecting and utilizing a broader spectrum of AIS data, as demonstrated in [

23]. This study successfully tracked ships through coastal images and AIS data obtained from satellites, effectively detecting unauthorized ship access.

While AIS data provides substantial navigational information, it is confined to data pertinent to the current ship state due to bandwidth restrictions. As the deployment of Low Earth Orbit(LEO) satellites expands the communication connectivity of ships and the phased realization of MASS necessitates more advanced automation, a broader array of data delivery methods is imperative. This need arises to address the evolving requirements of maritime systems and unlock the potential benefits of advanced autonomous ship capabilities.

2.3. Ship Data Collection and Service

In conjunction with AIS data, a multitude of sensors embedded in engine systems, including the engines themselves, generate real-time data based on the ship's operational status. Diverse research endeavors are actively contributing to the creation of a comprehensive platform capable of gathering such ship-related data and facilitating the expansion of data sharing and functionalities between ships and onshore systems.

In [

24], the research centers on applying IoT technologies to unmanned ships, exploring intelligent recognition, sensor fusion, and communication. This work culminates in the proposal of an E-Navigation framework aimed at connecting ships with onshore systems. In [

6], a Machine-Type Communication Framework is presented to enable efficient communication between peripheral ships and cloud systems, utilizing short-range and broadband connections. It aims to enhance MASS capabilities, promote interoperability, and facilitate seamless data exchange and collaboration in the maritime domain.

As the integration of IoT technology in ships advances, research has also delved into new services and service management. In addition to the earlier discussion on collision avoidance, there's a significant focus on creating optimal routes using weather forecast data to enhance operational performance in a safe and cost-effective manner [

25]. In addition, there has been research aimed at creating an Operator Training Simulator (OTS) environment. This simulation setup closely replicates the ship's operating conditions on onshore [

26]. The primary purpose of the OTS environment is to train both the crew and the ship's system to collaborate effectively, eliminating the need to physically visit the site during the development stage of ship operation technology, which is becoming increasingly intricate. An investigation in [

27] revealed that education through remote OTS environments contributes to enhanced navigation skills, especially as we move towards an era of training remote operators to handle actual MASS.

The expansion of technology and services in the maritime industry has led to a growing number of software applications that need to be managed. This increase in software complexity has posed challenges in management. In [

28], a study was conducted to address this issue by efficiently allocating Software Quality Assurance (SQA) resources in ship operating environments. The focus was on predicting defects in newly developed software based on models trained using historical software defect data. As software becomes increasingly vital for ship operations, the importance and reliance on S/W quality management techniques have grown. This has created an essential research area dedicated to maintaining service quality within the unique context of the maritime environment.

The integration of IoT technology into ship automation and maintenance has yielded significant research outcomes in vertical domains, such as ships and service units. However, in preparation for the era of MASS, these technological advancements must be further accelerated. This requires research into a cloud-based horizontal platform capable of rapid service development and deployment. In [

29], the research discussed the intricacies of cloud-based marine IoT solutions and proposed a solution to address this complexity using Fog Computing. Cloud platforms provide scalability, flexibility, security, and availability, which makes them well-suited for creating expansive IoT environments [

30].

In [

31], prominent cloud-based IoT platforms like AWS IoT, Azure IoT, Watson IoT, PTC ThingWorx, and Google IoT are identified. The study affirms that these public clouds provide essential functionalities for constructing extensive IoT environments. Among them, AWS IoT is the most widely used public cloud, boasting numerous references and ongoing research in designing and implementing structures tailored to specific applications and purposes [

32,

33].

3. Design of Multi-Service Data Platform

To prepare for the upcoming era of MASS, the need for a versatile platform that can accommodate the distinct requirements of each service, while considering the unique movement characteristics of ships, becomes paramount. In this section, we introduce a cloud-based multi-service data platform that encompasses a multi-region Fog Cloud, and elucidate the operational framework that enables the seamless functioning of diverse services, all built upon this unified platform. By leveraging this innovative approach, various services can be efficiently operated, capitalizing on the platform's adaptability and scalability, thus paving the way for the realization of autonomous ship systems.

3.1. Cloud Data Platform

3.1.1. Structure composed of multi-region fog cloud

Within cloud-based IoT services, the Fog Cloud emerges as a critical component, efficiently harnessing the resources of IoT devices while simultaneously enhancing service quality in close proximity to users [

9]. The maritime sector's increasing deployment of hundreds to thousands of sensors and actuators for automated ship navigation and engine control underscores the growing reliance on IoT technology [

1]. The adoption of Fog Cloud in the maritime domain offers a promising solution, particularly as the number of ships equipped with numerous control elements continues to rise.

The proposed platform introduces a pivotal role for the Fog Cloud, facilitating seamless data exchange and real-time functional operations between connected ships and onshore facilities or other ships. This cohesive integration effectively establishes a dynamic network, empowering ships to communicate and collaborate effortlessly, even in real-time scenarios.

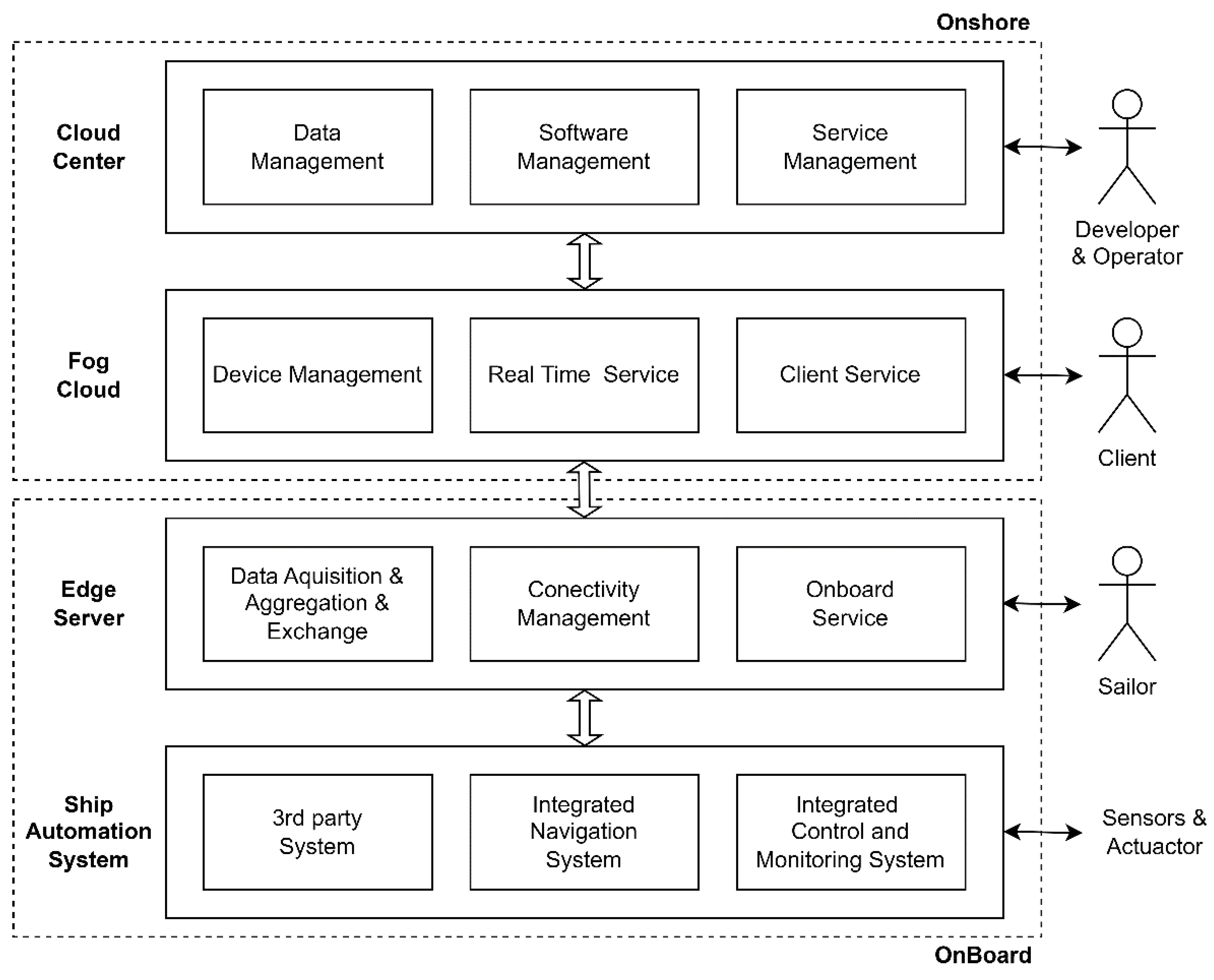

Figure 3 illustrates the platform topology built around the Multi-Region Fog Cloud. This setup comprises a cloud center primarily dedicated to data management and service development, along with a fog cloud optimized for service execution. This configuration facilitates the creation and implementation of diverse services tailored to the maritime environment. Given the worldwide movement of ships, establishing a seamless connection to a Fog Cloud that adapts based on their current location is of paramount importance. The Fog Cloud is meticulously designed to accommodate ship connections, initiating a secure Edge Secure Channel using pre-registered global device provisioning details for encrypted and protected communication with the vessels.

Clients seeking to build services based on data from ships within the same region, such as ports and logistics entities, can seamlessly develop these services through the Fog Cloud. Conversely, when a specific ship is designated for a particular service, such as in the case of a shipping company, the service can be constructed using cached data sourced from the Cloud Center. During this process, the Cloud Center's data is restricted to services that tolerate relatively higher latencies, as it is collected from data processed through the Fog Cloud at the ship's present location.

Clients can conveniently access the Fog Cloud's Web Service via the Public Internet network, enabling them to utilize the services built in this manner. The Cloud Center plays a vital role in managing data collected from the Fog Cloud and oversees the distribution and operation of software and services on the ship's Edge Server and Fog Cloud in each respective region. This functionality enables service developers to deploy and enhance new services efficiently by analyzing and utilizing the data available in the Cloud Center.

3.1.2. Functional structure of onboard and onshore

Figure 4 conceptually illustrates the representative functions and interaction relationships for each tier of the platform. The Edge Server plays a crucial role in collecting data from the ship's automation system, conducting Extract, Transform, Loading (ETL) processing, and providing services to sailors. Additionally, it manages connectivity to ensure consistent service quality as the ship moves around the world. Achieving this connectivity management entails establishing a unified entry point to the cloud, facilitating the identification of the nearest fog cloud, and entrusting the Edge Server with the task of sustaining the connection to the located fog cloud. Fog Cloud is distributed with services that require high real-time responsiveness. In instances where services involve collision avoidance for autonomous operations or engine system control for ship safety, interaction with the ship's Edge Server while operating on the Fog Cloud is necessary to avoid potential delay issues.

The Cloud Center is connected to Fog Cloud in each region through the Virtual Cloud Network, serving as a repository for data collected from the Edge Server or generated during service operations. By pre-caching the data required to serve clients in the region, Fog Cloud delivers high-quality services directly from the Cloud Center. Service developers and operators must carefully consider which components of the services they build will operate and interact with the Edge Server, Fog Cloud, or Cloud Center.

3.2. Ship-to-Ship Navigation Data Exchange For Collision Avoidance

3.2.1. Navigation Data Exchange by Platform

Ships rely on AIS, a legal equipment, to receive diverse data from nearby vessels and disseminate their own data to the surrounding area. When a ship is operational, its navigation status information is included in position report messages and broadcasted to nearby ships or coastal base stations [

20]. The transmission of such data occurs in shorter cycles when the ship's speed increases. However, these navigation data have limited usability as they can only provide the current location and operational status.

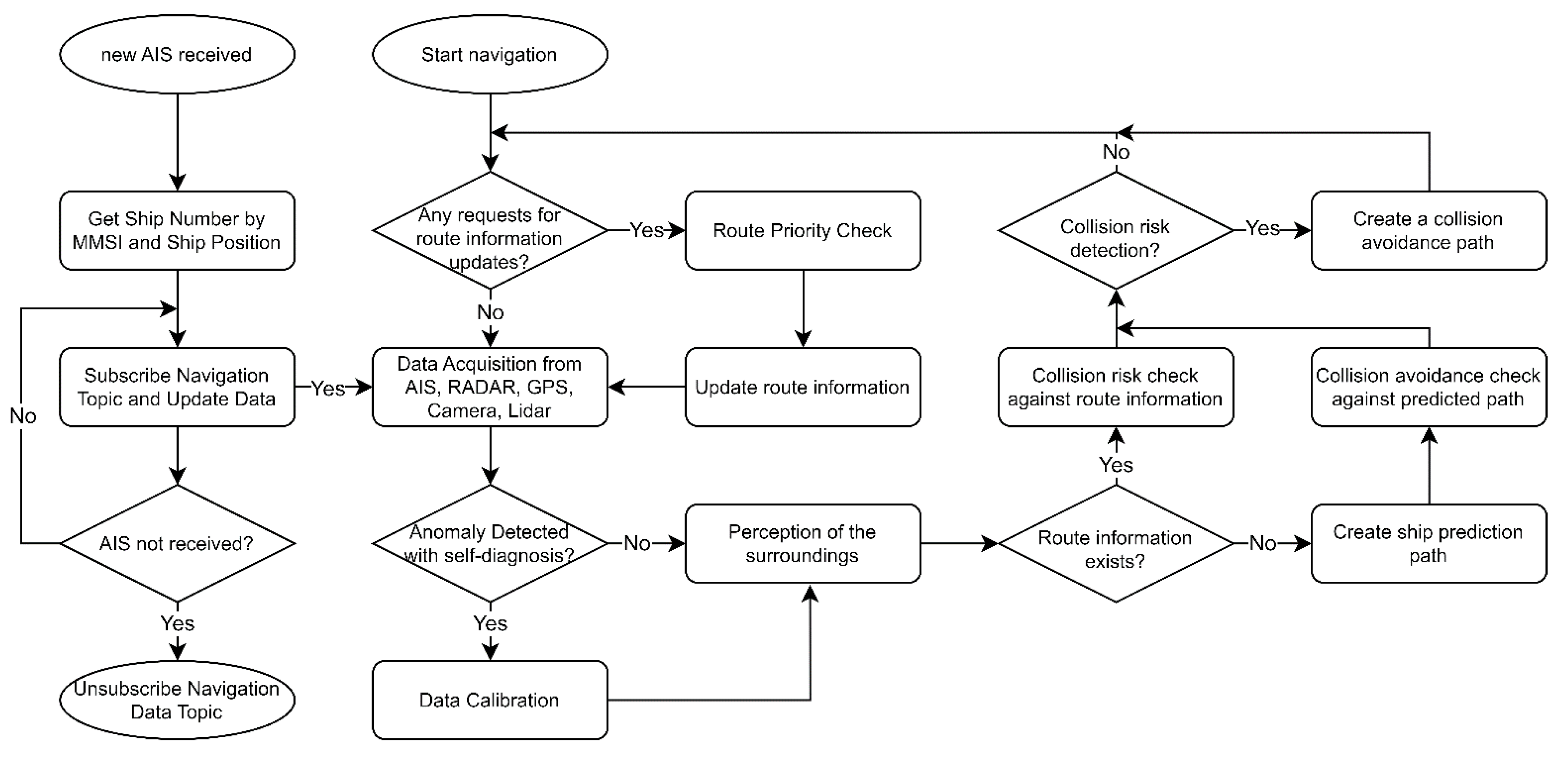

To address these limitations, this paper proposes a novel method that utilizes AIS information to enhance ship operations and promote stability. The approach involves sharing not only the ship's planned route but also relevant information about surrounding ships through a comprehensive platform. By doing so, ships can improve their operational efficiency and achieve a more stable navigational experience.

In the context of AIS messages, the uniqueness of the MMSI (Maritime Mobile Service Identity) number cannot always be guaranteed since it is directly entered by users into the equipment. To address this, when a ship receives an AIS message, it can request a ship_number, which serves as a unique ID for subscription, from the Fog Cloud's service using its MMSI and location information.

During the authentication process with the Fog Cloud, the ship's Edge Server obtains and receives the ship's unique ID, i.e., the ship_number. This ship_number is essential for seamless data exchange and communication among ships. To enable data sharing, the Edge Server extracts specific data, as outlined in

Table 1, from the Ship Automation System and publishes it to the Fog Cloud by Message Queuing Telemetry Transport (MQTT) during the ship's operation. This allows nearby ships to subscribe to and access the data using the ship_number as a unique identifier.

Through the sharing of AIS information, peripheral ships can compare and calibrate the AIS data received via VHF with the AIS data received through the platform. VHF typically has a limited recognition distance of approximately 50 miles (92 km) due to the curvature of the Earth's surface. However, by leveraging the platform to share AIS information, ships can effectively expand the recognition distance of the surrounding ships. Additionally, to efficiently manage and update the current route data, MQTT's retain function is utilized. This function ensures that new ships subscribing to the platform can receive the latest and most up-to-date route data when they join the network.

3.2.2. Utilization of Navigation Data

In the context of MASS, the traditional practice of operating only routes planned by the captain using ECDIS will evolve into a more diverse approach. As the realization of autonomous ships progresses, various routes will be operated in combination, offering new possibilities for navigation and operation. For instance, an automatic collision avoidance system, independent of the captain, can analyze the surrounding situation and generate a safe route to avoid potential collisions. Onshore facilities can also contribute by creating operating routes that consider economic efficiency, weather conditions, and overall traffic, which can then be applied to ships.

The exchange of navigation data through the platform will form the foundation for developing various functions required for the successful implementation of MASS.

Figure 5 illustrates the flowchart depicting how ships can receive data from surrounding vessels through the platform and utilize it for collision avoidance, primarily based on AIS data received via VHF. The ship's Edge Server subscribes to the data topics of the surrounding ships using the ship_number obtained from the platform, alongside the MMSI and location information from AIS. After analyzing the received data in conjunction with data from onboard sensors such as RADAR, Camera, and LIDAR, the ship can make real-time adjustments to its current route or create a new route, which is then applied to the TCS.

As MASS are still in the research stage, the Route Priority Check, performed before applying the route to the TCS, should be flexibly configurable, allowing for adaptability and customization based on specific operational requirements and conditions.

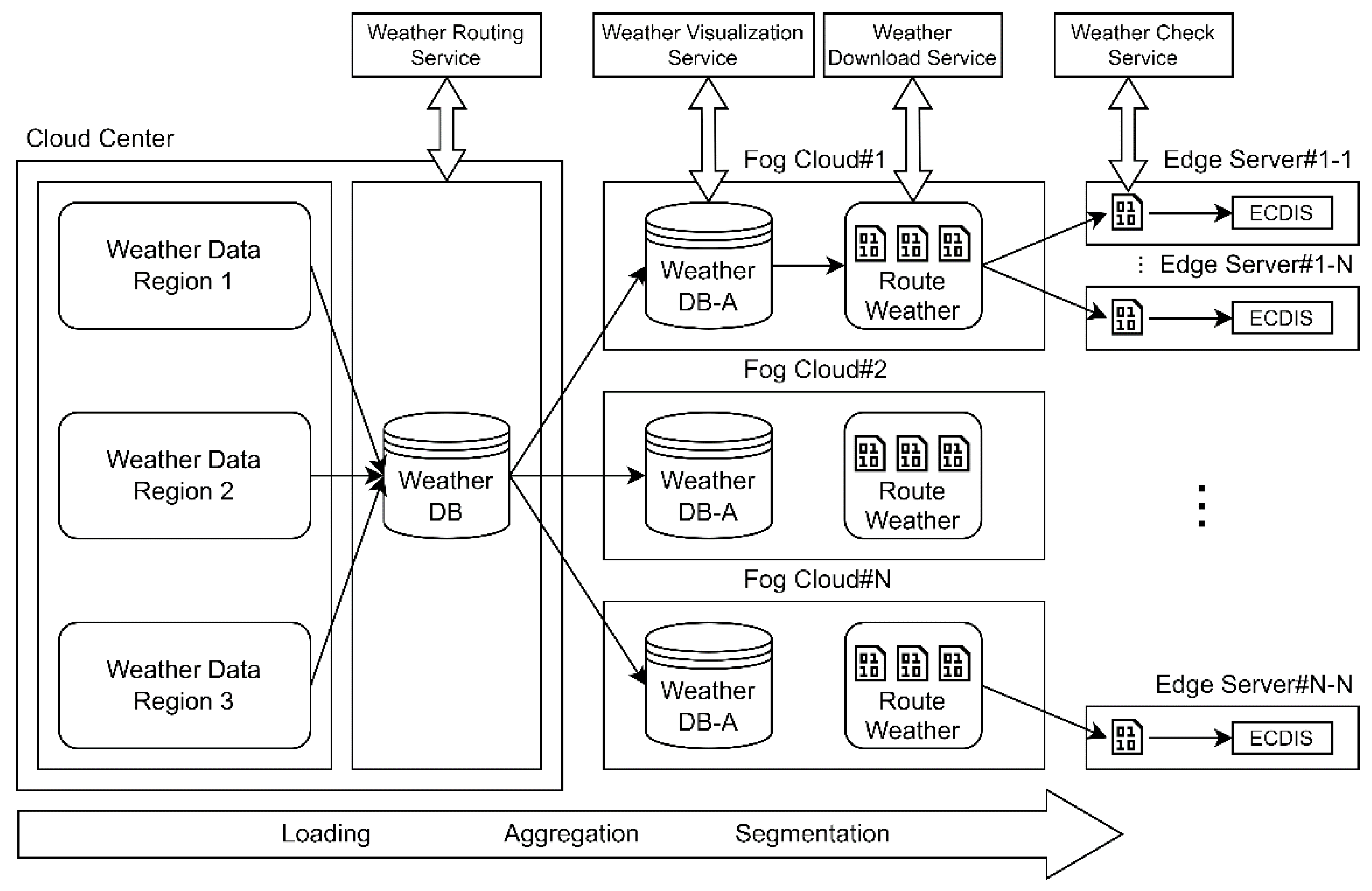

3.3. Platform Loading and Ship Distribution Structure of Weather Data

In order to operate ships safely and economically, meteorological data plays a crucial role [

25]. In this section, we will design a system that supplies weather data from the Cloud Center to the ship's Edge Server, which can be utilized by various service groups. The Cloud Center receives weather data from a dedicated weather server and provides optimized routes for economic operation. To facilitate this service for providing route plans based on weather data, four main functions are offered:

Weather Routing Service: Ship or onshore clients can request the Cloud Center, through Fog Cloud, for the most optimal route between their planned departure and destination. Leveraging its precise weather data, the Cloud Center generates an optimal route in response to the request.

Weather Visualization Service: Onshore clients can monitor operational conditions on the map, assessing operational efficiency using weather data. This allows them to correct existing operating routes or create new ones, which can then be delivered to ships.

Weather Download Service: Ships periodically download relevant weather data from the Fog Cloud for their designated routes. Given the nature of ship movement, there might be areas where communication is not possible. Hence, whenever communication is available, ships must ensure they have the latest weather data related to their operating routes.

Weather Check Service: The ship checks for differences between the weather forecast it received when obtaining the optimal route and the currently downloaded weather forecast. If significant changes are detected, the user is notified, and the ship can request the optimal route again through Fog Cloud.

Figure 6 illustrates the data flow within the platform and the service locations for these four weather-related services. The Cloud Center collects global weather data, aggregates it by region, and stores it in the database. To avoid overhead, precise weather data is synchronized to the Fog Cloud after aggregation. Each Fog Cloud segments weather data according to the in-flight route information managed by the respective Edge Server and downloads the relevant data to each Edge.

The Edge Server utilizes the downloaded weather data to display the current weather conditions for the route in operation. It also monitors changes in weather data received through the Weather Routing Service, alerting the user if any significant alterations are detected. In such cases, the route can be updated through Fog Cloud.

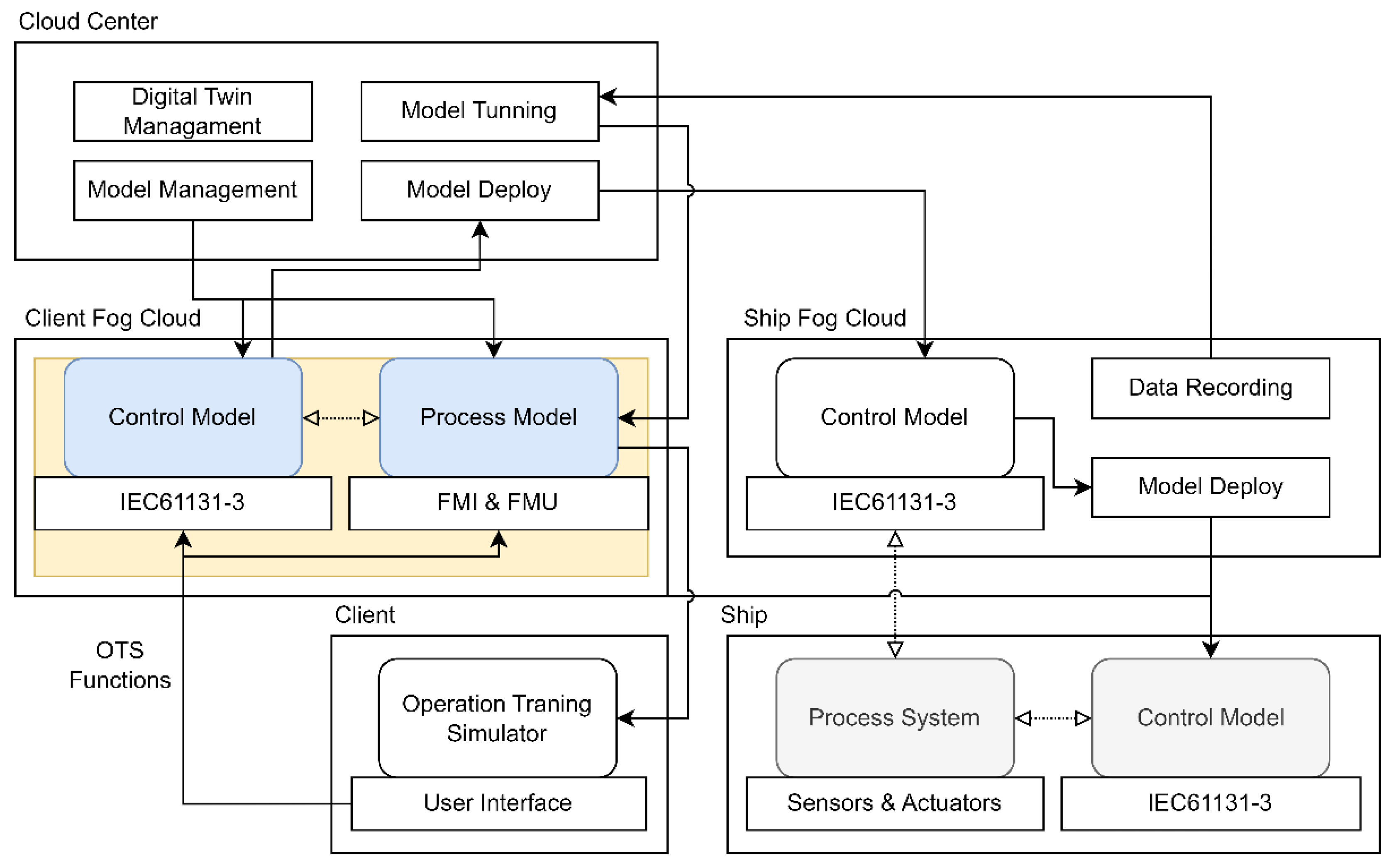

3.4. Digital Twin based OTS environment

This chapter introduces an approach to establish a digital twin environment for MASS. This is achieved through the development and deployment of ship process models and control models via the proposed platform. The resulting digital twin environment serves a dual purpose: predicting the present and future conditions of the ship and creating an Operator Training Simulator (OTS) environment where seafarers can undergo training in a real-world context.

Figure 7 provides a visual representation of this concept, depicting a configuration diagram wherein a client situated in a geographical region distinct from the actual ship constructs an OTS environment based on the digital twin concept using the platform. The process begins with the Client accessing the Fog Cloud at its location, enabling the formulation of a comprehensive process model delineating the ship's operations, alongside a control model to manage it.

The Fog Cloud, responsible for developing the process model, features a master clock orchestrating the synchronized execution of various ship systems. This facilitates the seamless operation of numerous components such as pumps, valves, and generators, emulating the ship's operational reality. Moreover, the Fog Cloud offers a standardized environment for the development of the process model, ensuring its scalability and adaptability through Functional Mockup Unit(FMU) & Functional Mockup Interface(FMI) [

34].

In parallel, the control model is designed within a standard IEC61131-3[

35] environment, tailored to real ship operations. This control model is subsequently distributed either to the ship's Fog Cloud or directly to an operational vessel. Since these models adhere to standardized parameters, it's possible to access and apply similar models for comparable ships through the Cloud Center or upload tailor-made models as required.

Following the development and testing of the process and control models by the Client Fog Cloud, the refined models are distributed to the ship's Fog Cloud for concurrent testing with the actual ship. The control model, now present in the Ship Fog Cloud, is tested alongside the live ship's process systems. The resulting data aids in fine-tuning the virtual process model, bringing it into closer alignment with the real-world model.

Upon successful calibration, the models are deployed to the actual ship, granting the crew the ability to operate the ship through the distributed control model. Furthermore, the control model can be shared with the Client Fog Cloud and integrated with a tuned process model to replicate a digital twin environment akin to the actual ship.

The OTS environment for sailor training is constructed similarly to the User Interface of the control model on the physical ship. Through this interface, seafarers can receive training that closely simulates ship operations by linking with the control model of the digital twin environment established on the Client Fog Cloud.

Educational needs are also addressed, encompassing functionalities that can emulate specific ship states or accelerate scenarios beyond real-time operations, depending on the instructional objectives [

26]. The process and control models built on the Client Fog Cloud are seamlessly integrated into these OTS functions, enabling effective educational simulations.

The Cloud Center serves as a hub for insights, drawing on data collected from actual ships via the Ship Fog Cloud. The Center leverages this data to simulate the process model created on the Client Fog Cloud, facilitating an analysis of current ship conditions and predictive scenarios based on the digital twin concept.

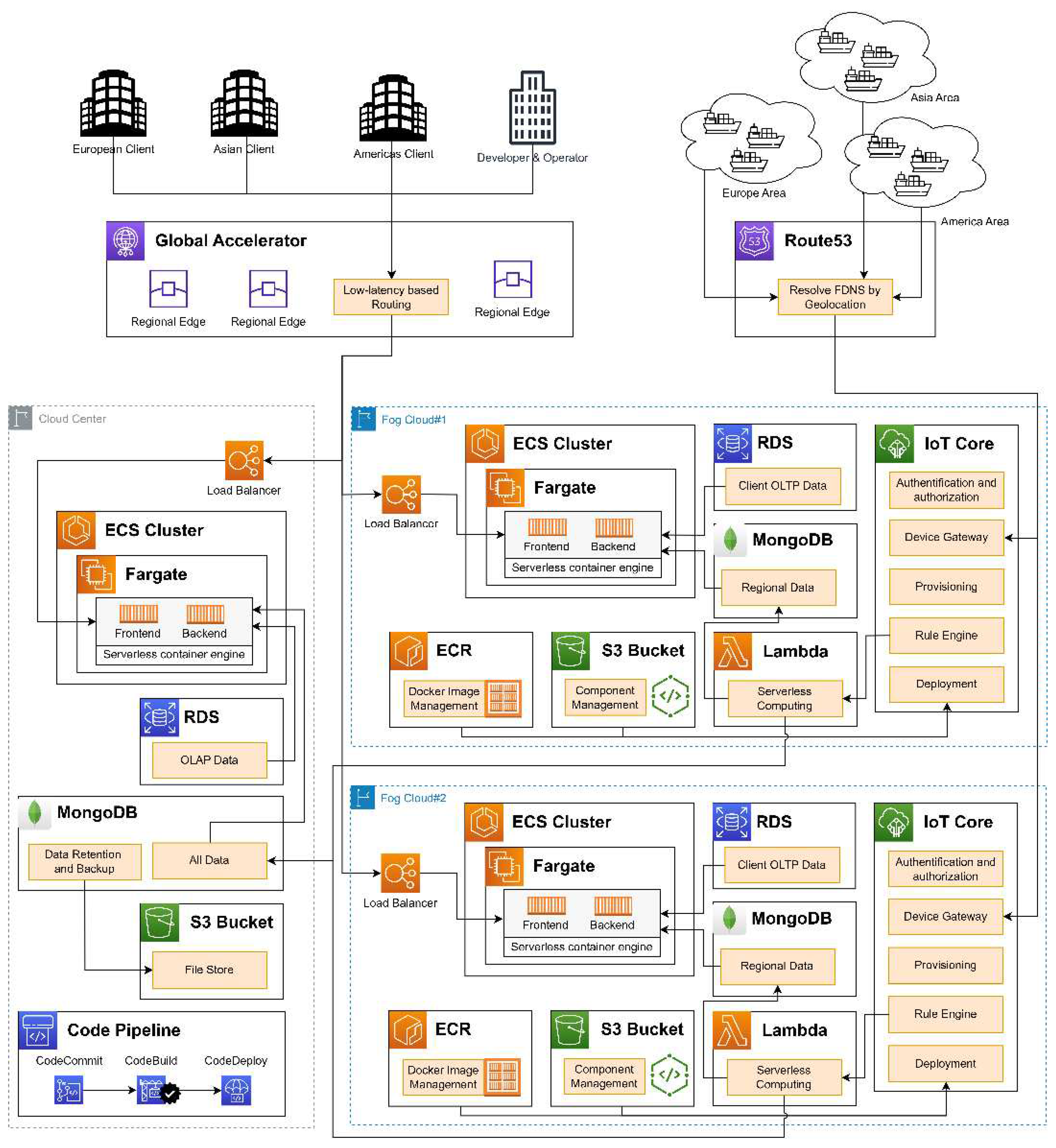

4. Implementation and Test

This chapter unveils the outcomes derived from the development of a multi-region fog cloud platform architecture using AWS, specifically tailored for the ship multi-service concept introduced in Chapter 3. Furthermore, comprehensive network communication assessments are undertaken across global regions. These evaluations aim to gauge the advantages intrinsic to the proposed architecture in scenarios where data sources, exemplified by ships, exhibit worldwide mobility attributes, and customer bases are geographically dispersed.

4.1. Implementation with AWS Cloud Architecture

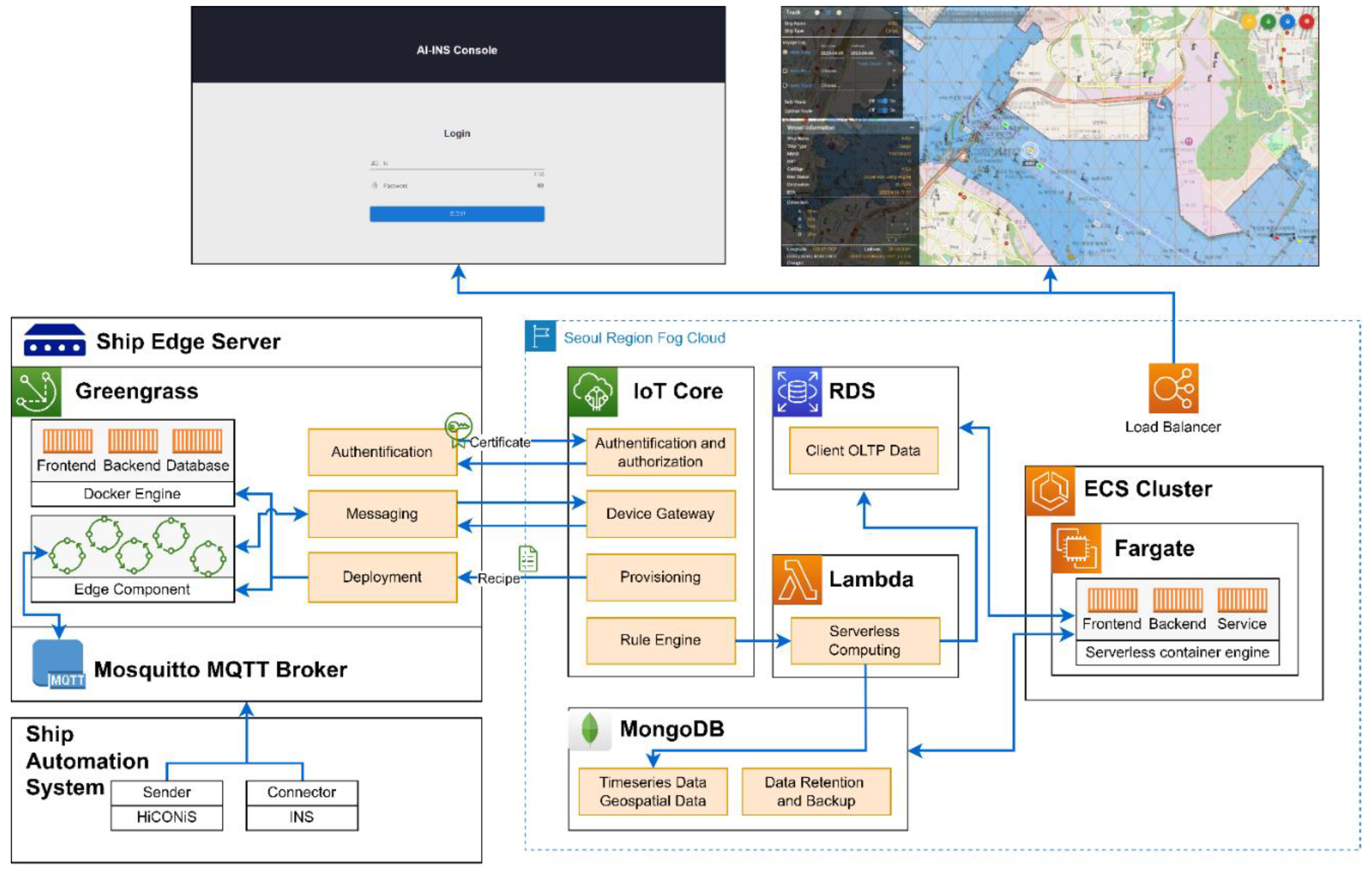

Figure 8 depicts a multi-region cloud architecture diagram established within the AWS cloud infrastructure. The strategic placement of the Cloud Center is advised in the region where the platform operator is active and engaged in service development. Fog Cloud distribution and construction offer benefits when strategically positioned in regions of concentrated ship activity or areas predominantly serviced by shipping companies and logistics ports.

Embedded within this construct is the AWS Global Accelerator [

34], a networking service that orchestrates an efficient network, allowing patrons to connect with minimal latency when the Fog Cloud sprawls across regions such as Europe, the Americas, and Asia. This orchestration empowers users to promptly access Regional Data generated by the Fog Cloud within their own domain, enabling them to generate or validate OLTP system-related data arising from user analysis or specific requests.

Given the worldwide mobility of ships, their integration with the Fog Cloud necessitates connection to the nearest regional instance, expertly guided by Geo-location. AWS Route53 [

35] serves as the common entry point, intelligently directing routing toward the nearest Fog Cloud to achieve optimal latency levels. By means of this routing mechanism, the ship's Edge server effectively links with the Global Device Provisioned Fog Cloud, ushering in services encompassing data monitoring, route planning based on weather conditions, and seamless software updates.

In an intricate dance of data, information harvested from ships finds residence in both the Fog Cloud for localized service provisions and the Cloud Center for comprehensive data analysis and monitoring. This strategic storage approach ensures that the Fog Cloud primarily retains short-term data, importing and servicing data from Cloud Center only when necessitated. This dynamic data management ensures an efficient utilization of resources.

Cloud Center functions as a hub for platform developers and operators, primarily focused on service development and software maintenance. For services demanding substantial resources or data-centric operations, the Cloud Center serves as the nexus. Consequently, even the database of the OLAP system revolves around and is managed within the Cloud Center.

Developers can seamlessly utilize the DevOps environment integrated into Cloud Center. This empowers them to manage source code configurations, develop software with builds, and efficiently deploy it to the testing environment following DevOps procedures. Upon successful testing, software distribution and management occur within the deployment environment of each Fog Cloud, encompassing both the ship's Edge Server and the container service environment of the Fog Cloud.

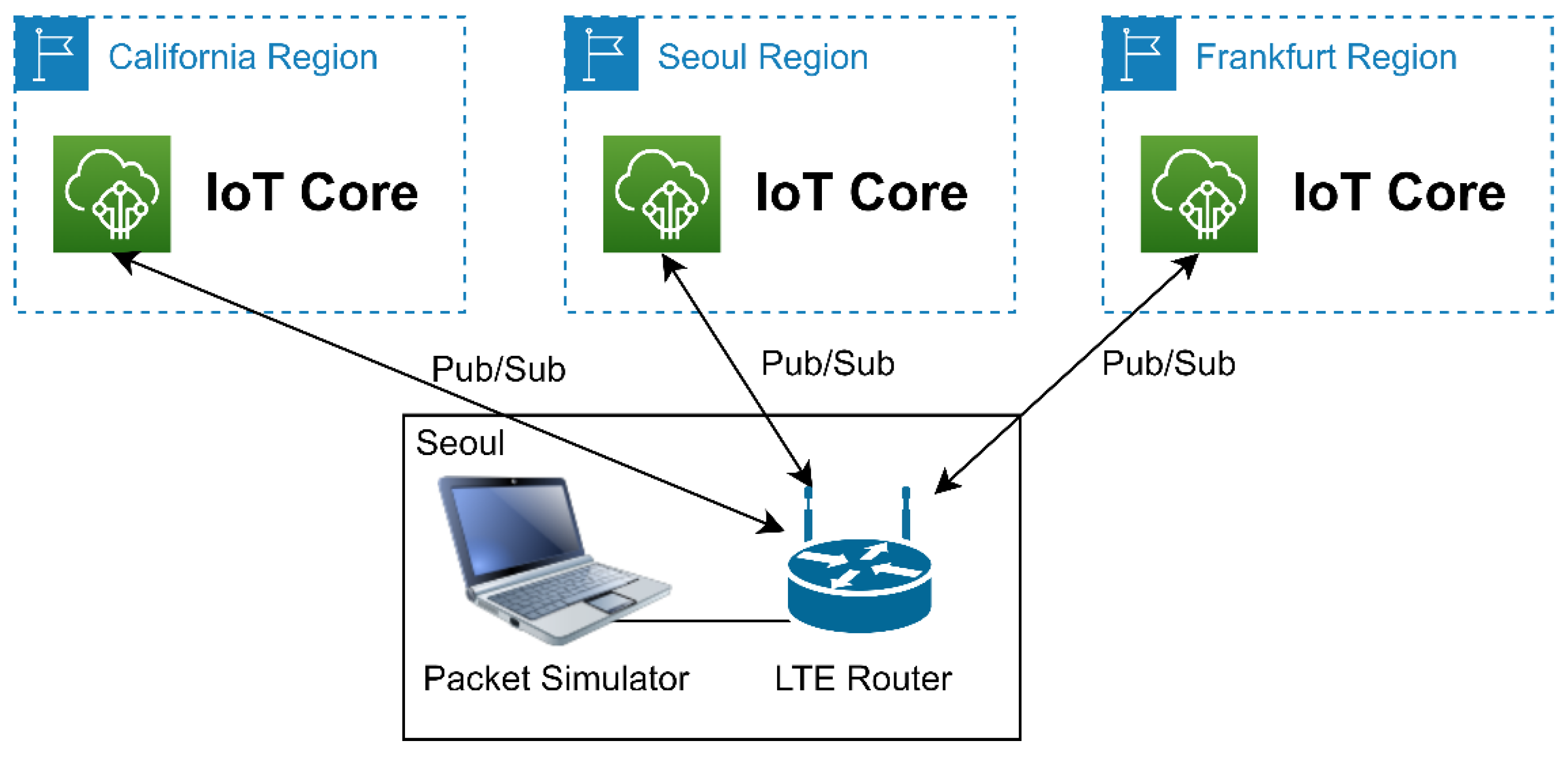

4.2. Network Latency and Packet Loss Rate Test

The objective behind expanding the platform through the implementation of a multi-region Fog Cloud is to enhance connectivity with ships traversing the globe, thereby facilitating the development of diverse services. In this chapter, we conducted tests to assess the potential improvement in network performance achievable through the utilization of a multi-region Fog Cloud. Specifically, we examined RTT-based Latency and Packet Loss Rate (PLR) by configuring tests in both the same region and different regions. The test setup is depicted in

Figure 9. Considering the laptop as a representative vessel located in the Seoul region, we conducted the test by engaging in the publication and subscription of messages to the IoT Core, which functions as an MQTT Broker. This testing process was carried out across three distinct regions: Seoul, California, and Frankfurt.

Latency was gauged using the RTT between the transmission and reception of published and received packets. As the maximum message size supported by IoT Core is 128 KBytes, the measurements were taken up to 120 KBytes, incrementing the payload by 20 Kbytes from the initial 20 KBytes. The publish/subscribe actions were executed with Quality of Service (QoS) set to 0, and this testing was performed 100 times for each payload size.

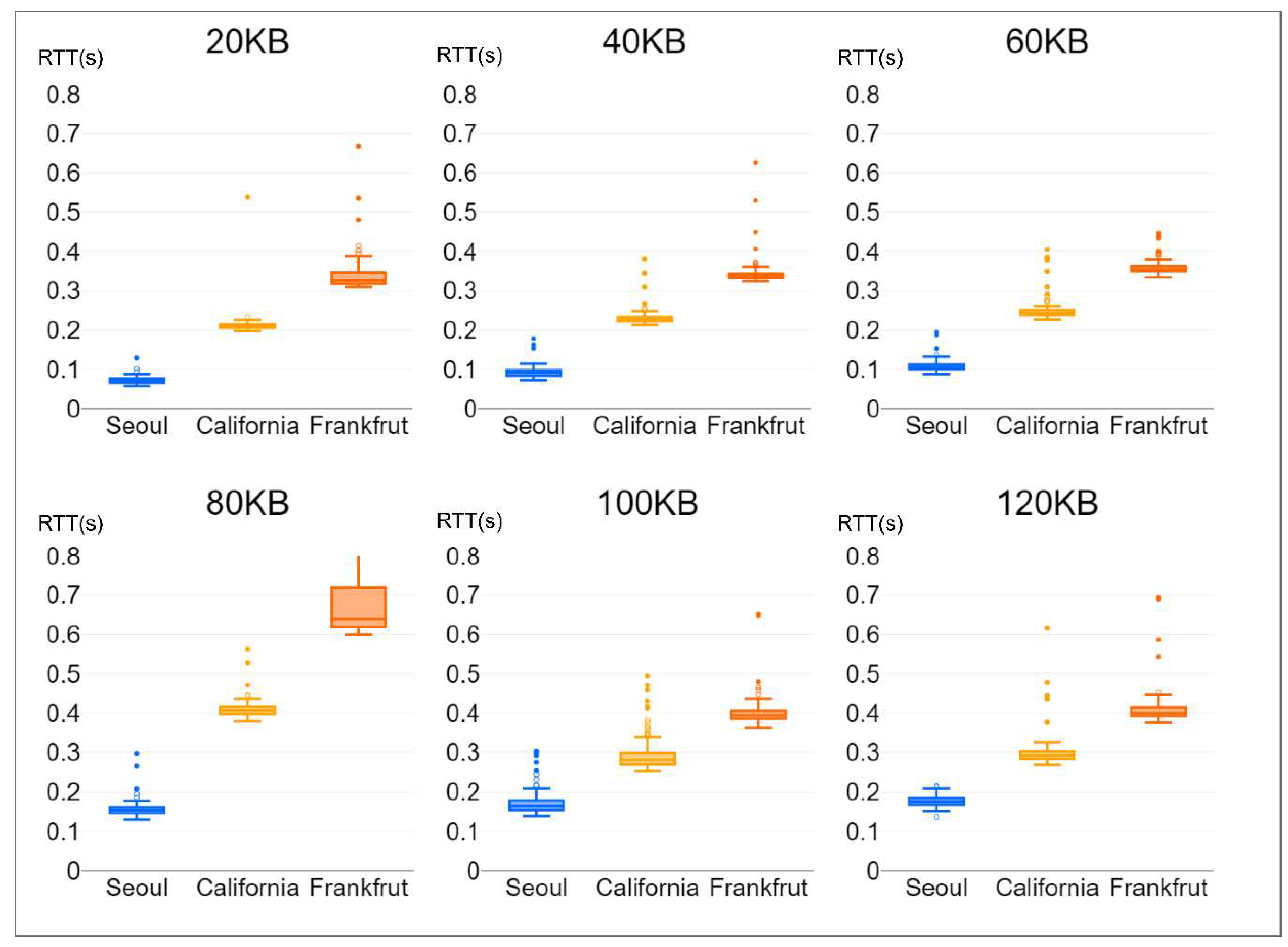

Figure 10 graphically presents the outcomes of these tests in the form of a box plot.

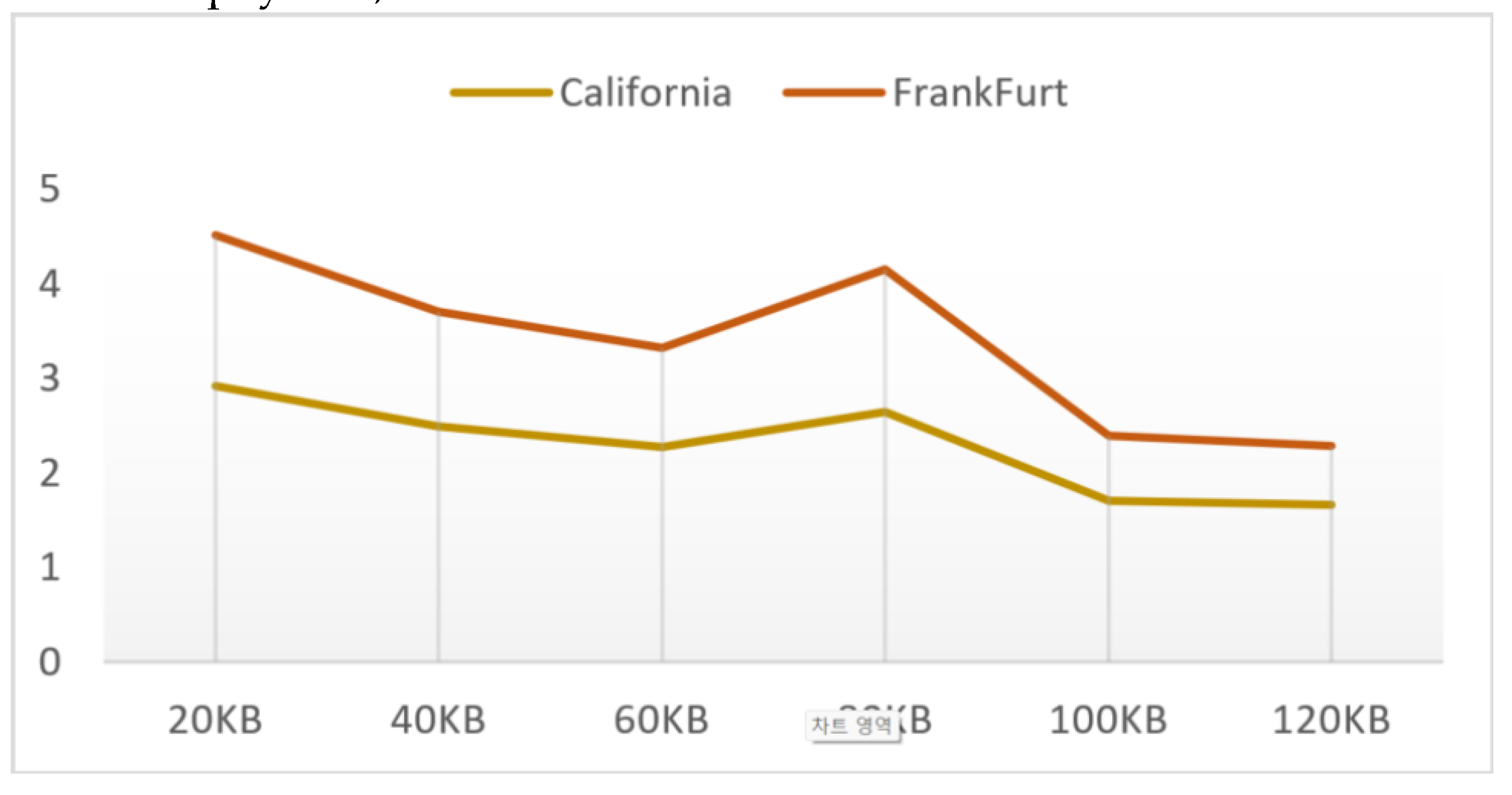

Considering that the testing took place in Seoul, the RTT exhibited the following patterns across the three Fog Cloud regions: the lowest median RTT was observed in the Seoul Region, ranging from 0.072 to 0.175 seconds. The California Region followed with the highest median RTT, spanning 0.21 to 0.292 seconds, and the Frankfurt Region exhibited the highest with a range of 0.326 to 0.400 seconds. When comparing the RTT with that of the Seoul region based on different payload sizes, as depicted in

Figure 11, it becomes evident that smaller payloads exhibit a more pronounced variance in RTT across regions. For a 20 KB payload, the RTT difference across regions ranged from 2 to 5 times, and for a 120 KB payload, the difference was around 2 times.

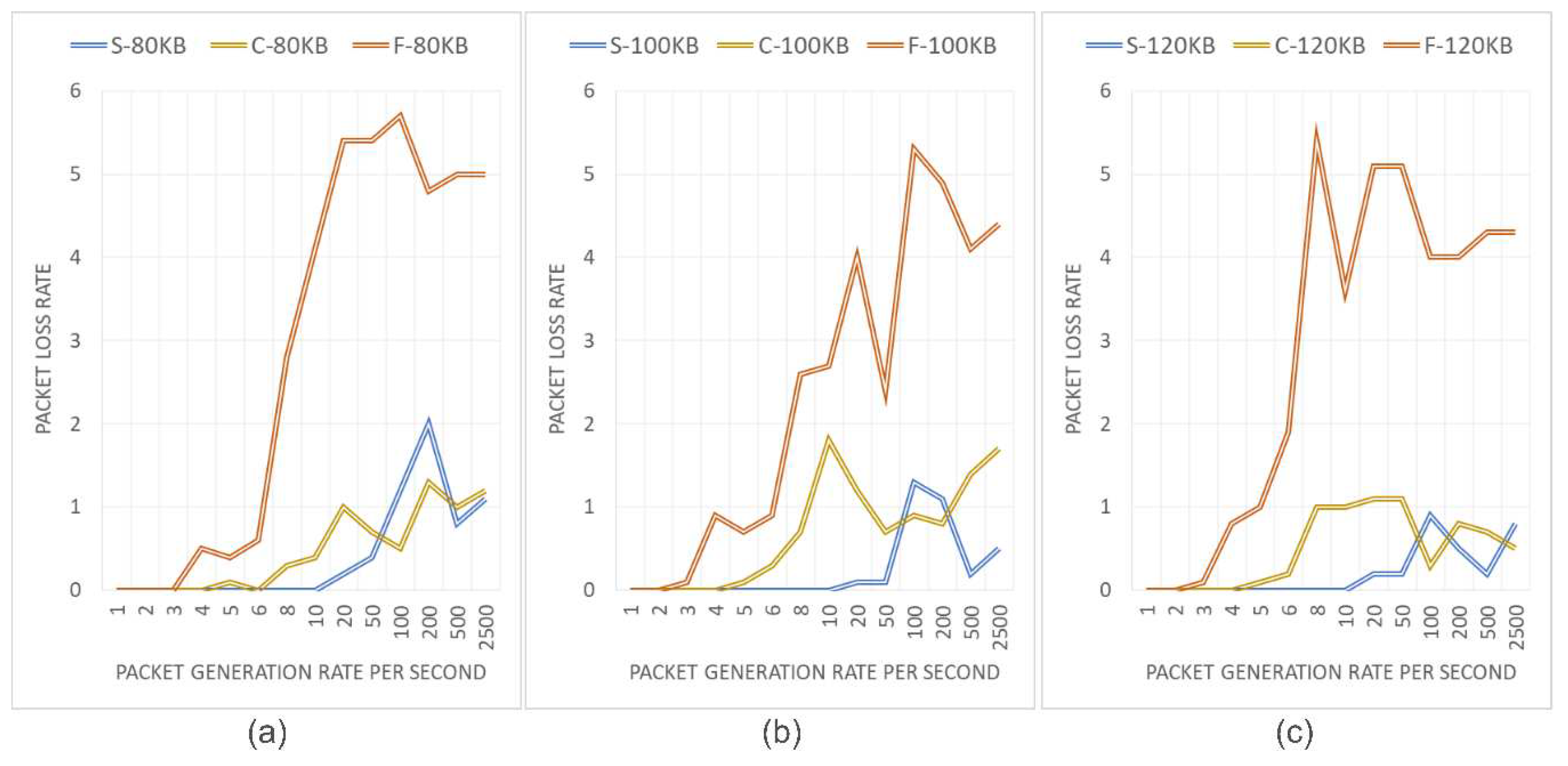

Packet Loss Rate (PLR) was evaluated as the packet generation rate (PGR) increased for each payload size. The assessment was conducted utilizing QoS0 settings. After establishing a connection, 100 packets were published based on the designated PGR, and PLR was subsequently determined by the count of received packets during subscription. This procedure was repeated 10 times per payload and region.

Interestingly, across all regions and various PGRs, when the payload remained at 60KB or below, the PLR consistently measured at 0. However, PLR started to manifest when the payload exceeded 80KB. The outcomes are visually depicted in

Figure 12. Notably, Frankfurt, which exhibited the highest network latency, initiated the generation of PLR at a PGR of 3Hz, while California exhibited this occurrence at 5Hz. In comparison, in the Seoul region, the PLR was observed from a PGR of 20Hz.

The trends observed in

Figure 12 reveal that PLR did not experience continuous escalation in tandem with the augmentation of PGR. Instead, it reached a point of convergence at a certain level. Upon closer examination of the sequence of lost packets, it was noted that the majority of losses transpired within the messages published before the 20th.

The test results have confirmed that for services necessitating a response time within the realm of several hundred milliseconds, optimal quality can only be sustained when the service operates within a cloud located in the same region. Furthermore, it has been observed that there is a potential for packet loss when reconnecting with IoT Core in the cloud, particularly when the payload surpasses 60KB and the Packet Generation Rate (PGR) is considered. Hence, for services that are particularly susceptible to packet loss, it is advisable to structure these services within the same region to mitigate the risk of packet loss. Alternatively, if there are no traffic restrictions, utilizing QoS1 can also be a suitable approach to ensure data integrity.

As the maritime industry incorporates more high-precision control components like LNG gas systems, electric propulsion, and generators, the demand for cloud-based services facilitating interaction with these elements is set to rise, especially with the progressive advancement of autonomous ships. Constructing a multi-region Fog Cloud-based platform presents a solution to ensure ships maintain the necessary connectivity for these services, even as they traverse the globe. The insights gleaned from the aforementioned tests will serve as valuable information to be taken into account when designing services within these platforms, considering potential constraints and optimizing performance.

4.3. Implementation of Ship Operation Monitoring Service

The proposed platform infrastructure in this paper opens the door to the development and distribution of a multitude of services. The Edge Server takes charge of distributing and executing binary files using the AWS Greengrass function, while also enabling operations via containerization using Docker images. Within the Fog Cloud or Center Cloud, services can be formulated to operate based on conditions like data input/output or specific timing, employing Severless Computing. Moreover, these services can be deployed as Docker images to function within container engine environments.

Figure 13 depicts a configuration diagram illustrating the implementation of a platform within the established cloud infrastructure and the creation of a ship operation monitoring web service utilizing containers. The design of this platform facilitates the remote linkage of data and control functions through MQTT-based messaging, involving the Ship Automation System and Edge Server. This framework enables the development and dissemination of new functionalities. The platform's architecture divides each service software into discrete operational units, including docker images, serverless computing code, and binaries, ensuring executable deployment. This structure allows services to be tested and operated within the context of the Micro Service Architecture approach. The presently constructed ship operation monitoring system furnishes users in distant locations with the ability to monitor the real-time current location and voyage status of ships to which they hold access privileges.

5. Conclusions

The maritime sector has established an environment where the integration of IT-combined automation systems like INS and ICMS allows comprehensive control and monitoring of numerous elements. Nevertheless, advancements in technologies like eco-friendly ships, electric propulsion vessels, and dual fuel engines are ushering in greater complexity in control elements, accompanied by an escalating number of objects and functions requiring management. This evolution is accentuated by the gradual progression toward autonomous ships, necessitating a sophisticated cloud-based platform that can navigate the intricacies of control elements and functions, expanding control beyond ships to encompass onshore operations.

In response, this paper introduces a platform structure centered on the Multi-Region Fog Cloud, strategically crafted to cater to the surging intricacy of control elements and the dynamic nature of ships' global navigation. This framework ensures consistent connectivity quality for ships by enabling them to access the nearest Fog Cloud based on their geographical position. The Fog Cloud facilitates Global Device Provisioning, fostering secure, certificate-based channels for data exchange between the ship's Edge Server and the platform, thereby optimizing resource usage. Additionally, to heighten service responsiveness within the same region, data is efficiently sourced from local storage, with essential information cached within the Cloud Center.

Furthermore, the paper outlines the implementation methodology for representative ship services within the proposed platform structure. Firstly, leveraging AIS data from neighboring vessels empowers collision avoidance by offering AIS data from nearby ships to the target vessel, including planned routes absent from the AIS dataset. Secondly, the paper harnesses the meteorological data distribution structure across Cloud Center, Fog Cloud, and Edge Server to provide route optimization grounded in meteorological data, adapting to evolving weather predictions. Lastly, a dependable digital twin environment is forged by developing process and control models within the Fog Cloud of the user and ship's region. This model's verification through connection to actual ships forms the basis for constructing Operator Training System (OTS) environments mirroring the ship's system interface.

The implementation of the proposed platform structure and the assessment of Multi-Region Cloud network advantages were facilitated through AWS Cloud. The design encompassed a comprehensive architecture implemented on AWS Cloud, featuring IoT Core in regions such as Seoul, California, and Frankfurt for measuring RTT-based latency and PLR. The results indicate that RTT differences vary based on payload size, with Seoul consistently achieving the lowest values at 0.072 to 0.175 seconds. Packet loss predominantly emerged at the outset of the connection, manifesting around 10 to 20 Hz within the same region and 3 to 5 Hz in other regions.

Lastly, the practical verification of function development and distribution performance on the platform was demonstrated through the creation of a ship operation monitoring web service. Functions were innovatively developed and disseminated via binary, serverless computing code, and docker images, effectively showcasing ship-collected data through the Edge Server on the web interface.

This study successfully designs and validates a Multi-Region Fog Cloud-based platform for multi-service ships, substantiated by rigorous testing and practical implementation. Future research endeavors aim to establish precise performance metrics by materializing the proposed services within the platform and assessing their efficacy on real-world ships.

Acknowledgements

This research is a part of ‘AI-based heavy cargo ship logistics platform demonstration project’ hosted by the Ulsan ICT Promotion Agency, supported by the National IT Industry Promotion Agency and the Ministry of Science and ICT (Project number: S1510-22-1001).

References

- S. Aslam, M. P. Michaelides and H. Herodotou, "Internet of Ships: A Survey on Architectures, Emerging Applications, and Challenges," in IEEE Internet of Things Journal, vol. 7, no. 10, pp. 9714-9727, Oct. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Krzysztof Wróbel, Mateusz Gil, Jakub Montewka.: Identifying research directions of a remotely-controlled merchant ship by revisiting her system-theoretic safety control structure, Safety Science,vol.129 (2020).

- F. Mauro, A.A. Kana.: Digital twin for ship life-cycle: A critical systematic review, Ocean Engineering 269

(2023).

- IMO (2018) Working group report in 100th session of IMO Maritime Safety Committee for the regulatory

scoping exercise for the use of maritime autonomous surface ships (MASS). Maritime Safety Committee

100th session, MSC 100/ WP.8.

- Fahad S. Alqurashi; Abderrahmen Trichili; Nasir Saeed; Boon S. Ooi; Mohamed-Slim Alouini.: Maritime

Communications: A Survey on Enabling Technologies, Opportunities, and Challenges, IEEE Internet of

Things Journal 10 (2023).

- Jingjing Zhang, Michael M. Wang, and Xiaohu You.: Maritime Autonomous Surface Shipping from a

Machine-Type Communication Perspective, IEEE Communications Magazine (2023).

- Michele Martelli, Antonio Virdis, Alberto Gotta, Pietro Cassarà, Maria Di Summa.: An Outlook on the

Future Marine Traffic Management System for Autonomous Ships, IEEE Access 9 (2021).

- Ganchev, I.; Ji, Z.; O’Droma, M. Horizontal IoT Platform EMULSION. Electronics 2023, 12, 1864. [CrossRef]

- Alli, A. A. , & Alam, M. M. (2020). The fog cloud of things: A survey on concepts, architecture, standards, tools, and applications. Internet of Things, 9, 100177.

- Yang, J. , Wen, J., Wang, Y., Jiang, B., Wang, H., & Song, H. (2019). Fog-based marine environmental information monitoring toward ocean of things. IEEE Internet of Things Journal, 7(5), 4238-4247.

- Cui, K. , Lin, B., Sun, W., & Sun, W. (2019). Learning-based task offloading for marine fog-cloud computing networks of USV cluster. Electronics, 8(11), 1287.

- Chenguang Liu, Xiumin Chu, Wenxiang Wu, Songlong Li, Zhibo He, Mao Zheng, Haiming Zhou, Zhixiong

Li, Human–machine cooperation research for navigation of maritime autonomous surface ships: A review

and consideration, Ocean Engineering, Volume 246, 2022, 110555, ISSN 0029-8018. [CrossRef]

- IEC Standard.: IEC61924-2 Maritime navigation and radiocommunication equipment and systems -

Integrated navigation systems (INS) (2021).

- Melih Akdağ, Petter Solnør, Tor Arne Johansen.: Collaborative collision avoidance for Maritime

Autonomous Surface Ships: A review, Ocean Engineering 250 (2022).

- Rasmus E. Nielsen, Dimitrios Papageorgiou, Lazaros Nalpantidis, Bugge T. Jensen, Mogens Blanke.:

Machine learning enhancement of manoeuvring prediction for ship Digital Twin using full-scale

recordings, Ocean Engineering 257 (2022).

- Nuwan Sri Madusanka, Yijie Fan, Shaolong Yang, Xianbo Xiang.: Digital Twin in the Maritime Domain: A

Review and Emerging Trends, Journal of Marine Science and Engineering (2023).

- CIMAC Guideline From CIMAC WG20 System Integration.: Virtual System Integration & Simulation - A

Performance-oriented Approach for Guiding System Simulation in the Field of Hybrid Marine

Applications (2023).

- IEC Standard.: IEC61162-1 Maritime navigation and radiocommunication equipment and systems - Digital

interfaces - Part 1: Single talker and multiple listeners (2016).

- IEC Standard.: IEC61162-450 Maritime navigation and radiocommunication equipment and systems -

Digital interfaces - Part 450: Multiple talkers and multiple listeners - Ethernet interconnection (2016).

- Svanberg, M., Santén, V., Hörteborn, A., Holm, H., & Finnsgård, C. (2019). AIS in maritime research. Marine

Policy, 106, 103520.

- M. Urakami, N. Wakabayashi and T. Watanabe, "A Study on Location Information Screening Method for

Ship Application Using AIS Recorded Data," 2018 International Conference on Broadband

Communications for Next Generation Networks and Multimedia Applications (CoBCom), Graz, Austria,

2018, pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- C. Wang, M. Zhu, O. Osen, H. Zhang and G. Li, "AIS data-based probabilistic ship route prediction," 2023

IEEE 6th Information Technology,Networking,Electronic and Automation Control Conference (ITNEC),

Chongqing, China, 2023, pp. 167-172. [CrossRef]

- Kurekin, A. A., Loveday, B. R., Clements, O., Quartly, G. D., Miller, P. I., Wiafe, G., & Adu Agyekum, K.

(2019). Operational monitoring of illegal fishing in Ghana through exploitation of satellite earth observation

and AIS data. Remote Sensing, 11(3), 293.

- Jia Wang, Yang Xiao, Tieshan Li, C. L. Philip Chen.: A Survey of Technologies for Un- manned Merchant

Ships, IEEE Access 8 (2020).

- Zis, T. P., Psaraftis, H. N., & Ding, L. (2020). Ship weather routing: A taxonomy and survey. Ocean

Engineering, 213, 107697.

- Hwang, T., & Youn, I. H. (2022). Difficulty Evaluation of Navigation Scenarios for the Development of Ship

Remote Operators Training Simulator. Sustainability, 14(18), 11517.

- Hwang, H., Hwang, T., & Youn, I. H. (2022). Effect of Onboard Training for Improvement of Navigation

Skill under the Simulated Navigation Environment for Maritime Autonomous Surface Ship Operation

Training. Applied Sciences, 12(18), 9300.

- Kang J, Ryu D, Baik J.: Predicting just-in-time software defects to reduce post-release quality costs in the

maritime industry. Softw: Pract Exper. 2020;1–24. [CrossRef]

- Cankar, M. , & Stanovnik, S. (2018, December). Maritime IoT solutions in fog and cloud. In 2018 IEEE/ACM International Conference on Utility and Cloud Computing Companion (UCC Companion) (pp. 284-289). IEEE.

- Gallagher, D. , & Lennon, R. G. (2022, October). Architecting Multi-Cloud Applications for High Availability using DevOps. In 2022 IEEE International Conference on e-Business Engineering (ICEBE) (pp. 112-118). IEEE.

- Barros, T. G. , Neto, E. F. D. S., Neto, J. A. D. S., De Souza, A. G., Aquino, V. B., & Teixeira, E. S. (2022). The Anatomy of IoT Platforms—A Systematic Multivocal Mapping Study. IEEE Access, 10, 72758-72772.

- Kodali, R. K. , & Sabu, A. C. (2022, January). Aqua monitoring system using aws. In 2022 International Conference on Computer Communication and Informatics (ICCCI) (pp. 1-5). IEEE.

- Battula, S. , Kumar, M. N. V. S. S., Panda, S. K., Rao, U. M., Laveti, G., & Mouli, B. (2020, October). Online ocean monitoring using edge IoT. In Global Oceans 2020: Singapore–US Gulf Coast (pp. 1-7). IEEE.

- Functional Mockup Interface Standard. https://fmi-standard.org/.

- IEC Standard.: IEC 61131-3:2013 Programmable controllers - Part 3: Programming languages (2013).

- Amazon AWS. 2023. AWS Global Accelerator. https://aws.amazon.com/globalaccelerator/.

- Amazon AWS. 2023. AWS Global Accelerator. https://aws.amazon.com/route53/.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).