Submitted:

05 September 2023

Posted:

06 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

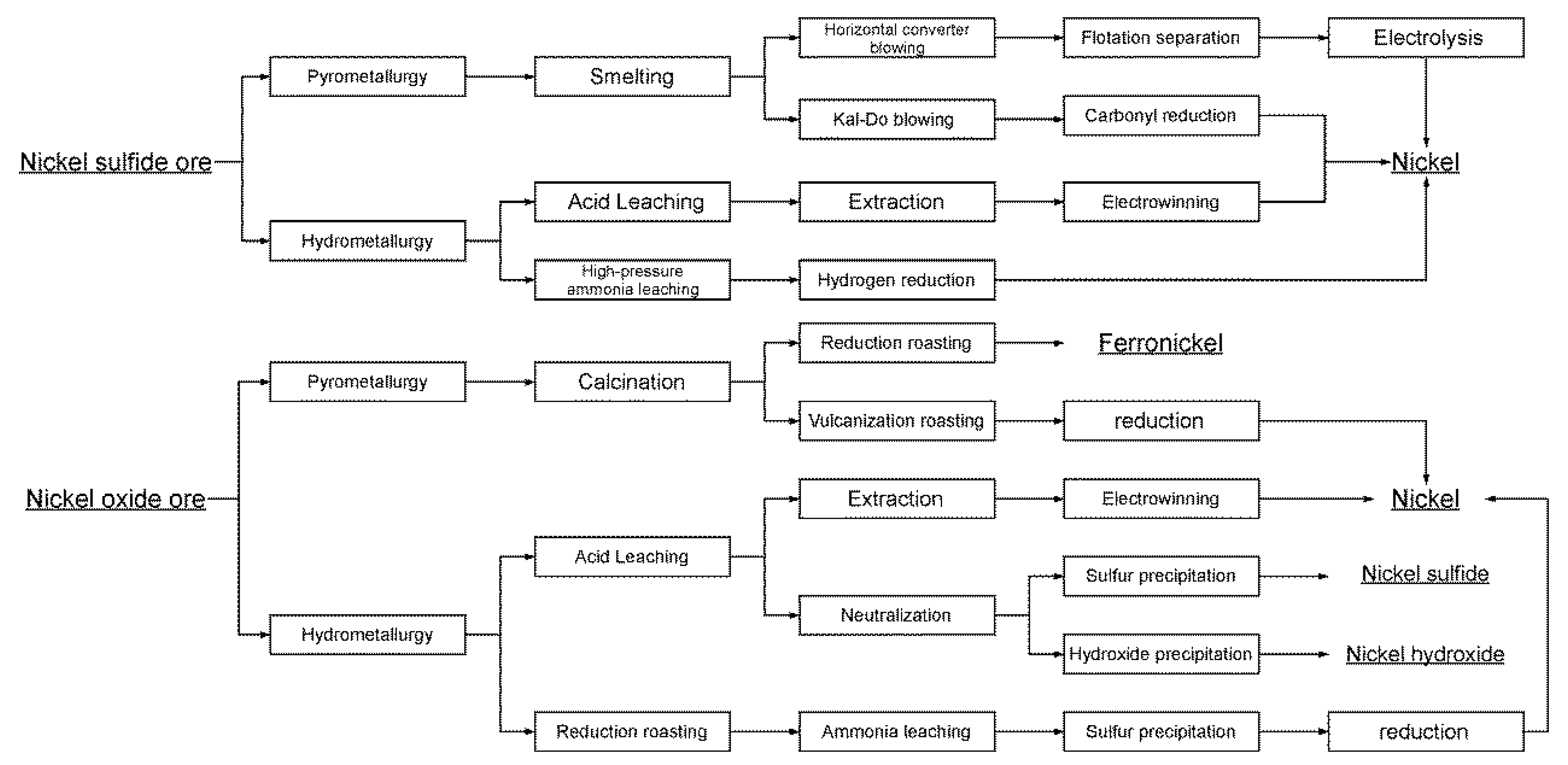

2. Nickel production process

2.1. Distribution of nickel ore

2.2. The primary production process of nickel

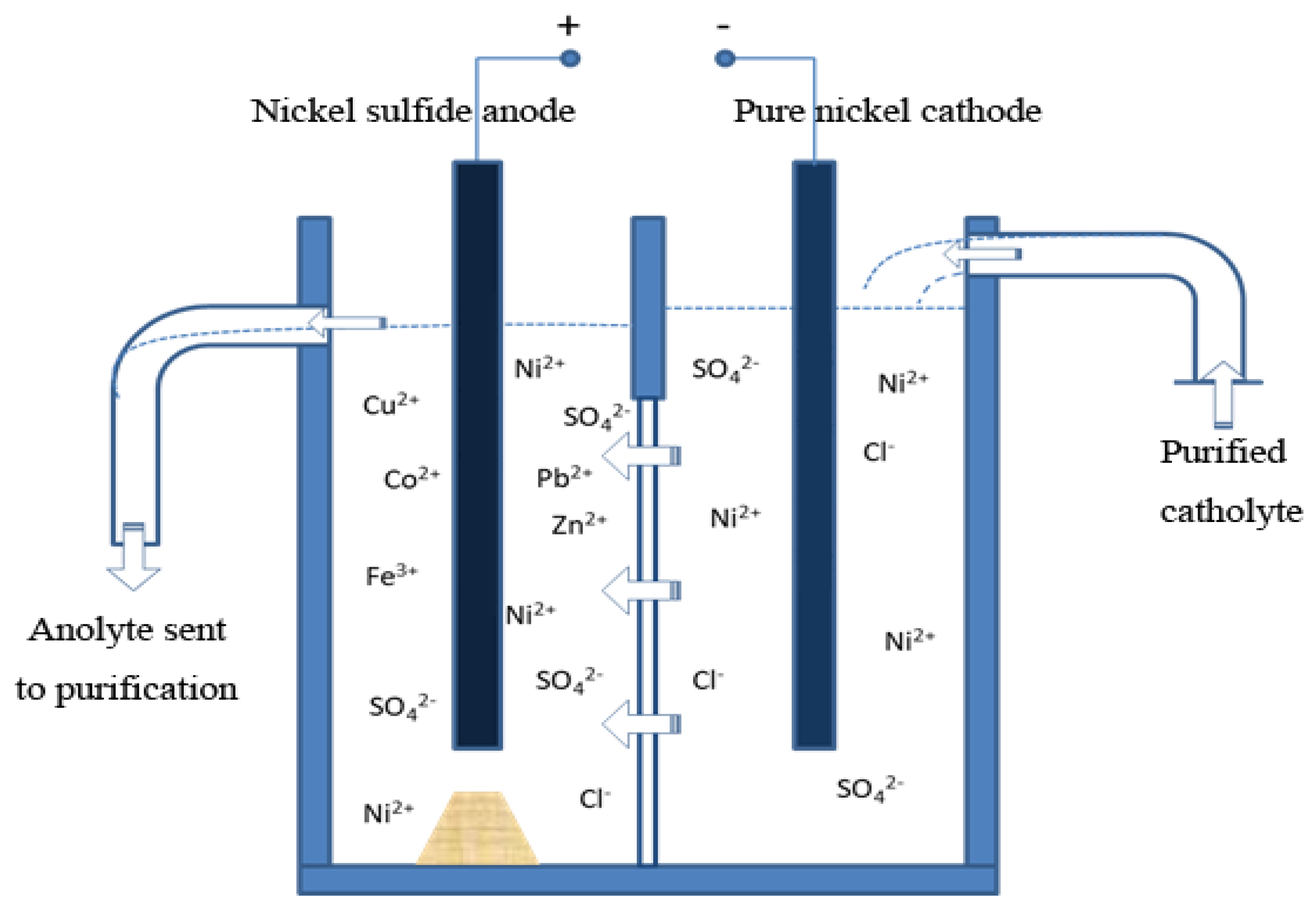

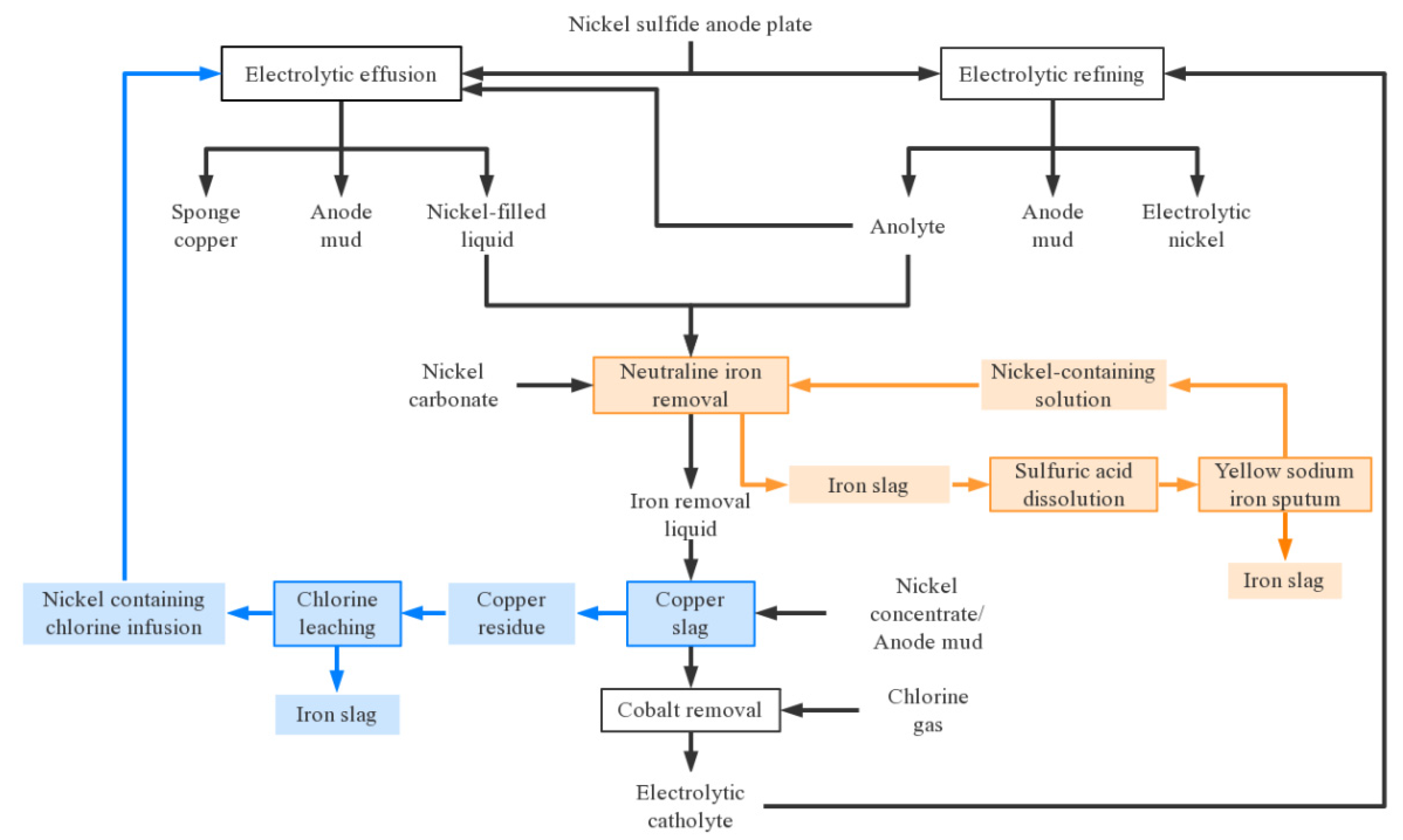

2.3. Electrolytic refining process of nickel sulfide

3. The removal of copper from nickel electrolysis anolyte

3.1. Potential-based separation method

3.2. Chemical precipitation method

3.3. Solvent extraction

3.4. Ion-exchange method

4. Extraction of nickel using iminodiacetic acid chelating resin

4.1. Synthesis method

4.2. Adsorption mechanism

4.3. The practical application of IDA chelating resin in nickel extraction

5. Perspective

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

References

- Sutherland WF. The Story of Nickel. Scientific American. 1919;121(20):480-1.

- Morinaga M. Nickel Alloys: A Quantum Approach to Alloy Design; 2019.

- COLE, Mining LJA. NICKEL: THE 2015 OUTLOOK. 2014.

- Loto, Silicon CAJ. Electroless Nickel Plating – A Review. 2016;8(2):177-86.

- Li MA, Bai YN, Hong Quan PU, Jie HE, Bassig BA, Dai M, et al. A Retrospective Cohort Mortality Study in Jinchang, the Largest Nickel Production Enterprise in China. 2014;000(7):567-71. [CrossRef]

- Yang AM, Hui SU, Wei RX, Bin HX, Bai YN, Hong Quan PU, et al. Prevalence of Metabolic Syndrome in Chinese Nickel-exposed Workers. 2014;000(6):475-7. [CrossRef]

- Bao-Zhong MA, Yang WJ, Qian LI, Wang CY, Wang HJNM. Mineral Phase Analysis and Treatment Technological Selection of Magnesium-rich Nickel Oxide Ore. 2016.

- metals WY-gJwn. Development status and sustainable development strategy of nickel resources in China and its key technologies. 2018.

- Yang XS, Guo YS, Chen BY, Cui YL, Guo XJAGS. The distribution and the exploration, development and utilization situation of the lateritic nickel ore resources in the world. 2013;34:193-201.

- Lu C LX, Zou X, Cheng H, Xu Q. Current situation and utilization technology of nickel ore in China. Chinese Journal of Nature. Chinese Journal of Nature. 2015;37(04):269-77.

- Huang CL, Vause J, Ma HW, Li Y, Yu CPJJoCP. Substance flow analysis for nickel in mainland China in 2009. 2014;84(dec.1):450-8. [CrossRef]

- Zhou HP, Yun-Qiang LI, Lei MF, Jing XU, Wang PC, Weng CJJM, et al. New Beneficiation Technique for Certain Refractory Fine Copper-Nickel Sulfide Ore. 2015.

- Wang H, Ye Z, Hao F, Yuan HJMM. Experimental Study on a Low-grade Copper-nickel Sulfide Ore. 2015.

- Dutton MD, Vasiluk L, Ford F, Perco MB, Taylor SR, Lopez K, et al. Towards an exposure narrative for metals and arsenic in historically contaminated Ni refinery soils: Relationships between speciation, bioavailability, and bioaccessibility. 2019;686(OCT.10):805-18. [CrossRef]

- Illis A. Nickel metallurgy. 2008.

- Liu T, Zhou EJJoBIoT. Thermodynamics of Standard Solubility Product. 1996.

- Ruijuan S. Study on the process of copper removal by nickel electrolysis purification: Lanzhou University of Technology; 2012.

- Zeng Zhenou ZY, Wu Hongru. Research on the Electrodeposition Method for Purifying and Removing Copper from Jinchuan Nickel Electrolytic Anode Liquid Hunan Metallurgy. 1994;000 (4):11-4.

- Zeng Zhenou ZY, Wu Hongru. Study on direct electrolytic purification of copper removal in nickel electrolysis anode liquid Journal of South China University of Technology (Natural Science Edition). 1994;000(5):32.

- M. Lira-Cantu AMS, A. brustenga, et al. Electrochemical deposition of black nickel solar absorber coatings on stainless steel AISI316L for thermal solar cells. Solar Energy Materials and Solar Cells. 2005;87(1-4):685-94.

- Ruijuan S. Study on the process of copper removal by nickel electrolysis purification 2012.

- Zhai Xiujing LB. Research on sulfur-containing active nickel. Nonferrous Mining and Metallurgy. 1998;14(4):31-3.

- Shu Yude YX. Preparation of active anode slime for removing copper from nickel electrolyte. Nonferrous Metals: Smelting Section. 1996;(5):24-6.

- Gu Guobang WX, Cheng Fei, et al. Application of ultrafine particles in chemical separation-research on the characteristics of activated nickel sulfide. Journal of South China University of Technology: Natural Science Edition. 1996;(8):96-100.

- Zeng Dewen LZ, Xu Shengming, et al. Experimental study on the removal of copper from nickel electrolysis anolyte with nickel thiosulfate. Hunan Nonferrous Metals. 1996;(4):49-52.

- Ailiang C. A new process and basic research of copper removal and purification by nickel sulfide electrolysis anode liquid. Changsha: Central South University; 2006.

- Dai K LY, Hu H, Cheng Z, Liu S, Chen Q. Removal of copper from nickel anode electrolyte by AMPY-1. Nonferrous Metals (Extractive Metallurgy). 2015;(10):10-3.

- Ivanov IM NA, Gindin LM. Solvent extraction removal of cobalt and other impurity elements from nickel electrolytes. Hydrometallurgy. 1979;4(4):377-87.

- Fischer C WH, Bagreev VV. On the tri-n-octylammonium chloro complexes of Cu (II), Zn (II) and Co (II) in benzene solution. Polyhedron. 1983; 2(11):1141-6.

- Sarangi K PP, Padhan E. Separation of iron (III), copper (II) and zinc (II) from a mixed sulphate/chloride solution using TBP, LIX 84I and Cyanex 923. Separation and Purification Technology. 2007;55(1):44-9.

- Wu F LJ. Study on separation of Cu2+ from nickel sulphaate solution with extraction M5640. Journal of Wuyi University (Natural Science Edition). 2004;18(1):25-7.

- Chen A SP, Zhao Z, Chen X, Zhang Y. Coper removal from Nickel anode electrolyte by ion exchange. Minning and Metallurgical Engineering. 2005;25(6:51-4.

- Ma J HB. The application of ion exchange resins in hydrometallurgy. Ion Exchange and Adsorption. 1993;9(3):250-60.

- Xiang W LZ. New progress of synthesis and application study of specific ion exchange. Technology and Development of Chemical Industry. 2003;32(2):16-22.

- Lou F DB, Bi Y, Xie J. Adsorption of metalcation by chelating resin. Technology of Water Treatment. 2011;37(01):23-7.

- Xu Y YY, Li H. Study on chelatingresins-Syntheses and Adsorption properties of thiourea type resin. Wuhan University.45(2):23-7.

- Zhuang H ZZ, Jin W, Gou L. Preparation and adsorption properties of crosslinked polyaminated chitosan chelating resin. Ion Exchange and Adsorption. 2001;17(6):507-14.

- Kong L WZ, Zhang X, Yang Y. Syntheses and application of specific ion exchanger. Inner Mongolia Petrochemical Industry. 2006;(2):19-21.

- Kuz’min VI KmD. Sorption of nickel and copper from leach pulps of low-grade sulfide ores using Purolite S930 chelating resin. Hydrometallurgy. 2014;141:76-81.

- Noureddine C LA, Mubarak MS. Sorption properties of the iminodiacetate ion exchange resin, amberlite IRC-718, toward divalent metal ions. Journal of Applied Polymer Science. 2008;107(2):1316-9.

- Mendes FD MA. Selective sorption of nickel and cobalt from sulphate solutions using chelating resins. International Journal of Mineral Processing. 2004;74(1-4):359-71.

- Dinu MV DE. Heavy metals adsorption on some iminodiacetate chelating resins as a function of the adsorption parameters. Reactive and Functional Polymers. 2008;68(9):1346-54.

- Silva RMP MJ, Rodrigues JRC, Lagoa RJL. A comparative study of alginate beads and an ion-exchange resin for the removal of heavy metals from a metal plating effluent. Journal of Environmental Science and Health Part A. 2008;43(11):1311-7.

- Agrawal A SK. Separation and recovery of lead from a mixture of some heavy metals using Amberlite IRC 718 chelating resin. Journal of hazardous materials. 2006;133(1-3):299-303.

- Valverde JL dLA, Carmona M. Equilibrium data of the exchange of Cu2+, Cd2+ and Zn2+ ions for H+ on the cationic exchanger Lewatit TP-207. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology. 2004;79(12):1371-5.

- Jachuła J KD, Hubicki Z. Removal of Cd (II) and Pb (II) complexes with glycolic acid from aqueous solutions on different ion exchangers. Canadian Journal of Chemistry. 2010;88(6):540-7.

- Johnson BE SP, Chuang CY, Otosaka S. Collection of lanthanides and actinides from natural waters with conventional and nanoporous sorbents. Environmental ence & Technology. 2012;46(20):11251-8. https://doi.org/10.1021/es204192r. [CrossRef]

- Zainol Z NM. Comparative study of chelating ion exchange resins for the recovery of nickel and cobalt from laterite leach tailings. Hydrometallurgy. 2009;96(4):283-7.

- Mendes FD MA. Selective nickel and cobalt uptake from pressure sulfuric acid leach solutions using column resin sorption. international journal of mineral processing. 2005;77(1):53-63.

- Korngold E BN, Aronov L, Titelman S. Influence of complexing agents on the removal of metals from water by a cation exchanger. Desalination. 2001; 133(1):83-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0011-9164(01)00085-6. [CrossRef]

- Yebra-Biurrun MC C-MN. Flow injection flame atomic absorption determination of Cu, Mn and Zn partitioning in seawater by on-line room temperature sonolysis and minicolumn chelating resin methodology. Talanta. 2010;83(2):425-30.

- Nicolai M RC, Tousset N, Nicolai Y. Trace metals analysis in estuarine and seawater by ICP-MS using online preconcentration and matrixe limination with chelating resin. Talanta. 1999;50(2):433-44.

| Element | Nickel 1# (mol/L) | Nickel 0# (mol/L) |

|---|---|---|

| Ni | 1.19 | 1.19 |

| Cu | <4.72×10-5 | <4.72×10-6 |

| Fe | <7.14×10-5 | <5.36×10-6 |

| Co | <1.70×10-4 | <1.70×10-5 |

| Zn | <5.35×10-6 | <1.53×10-6 |

| Pb | <3.00×10-4 | <7.00×10-5 |

| Na+ | <1.96 | <1.96 |

| Cl- | >1.41 | >1.41 |

| H3BO3 | <9.7×10-2 | <9.7×10-2 |

| Electrode | Electrode process | φϴ/V |

|---|---|---|

| Cd | Cd2+ | Cd2++2e= Cd | -0.403 |

| Co | Co2+ | Co2++2e= Co | -0.28 |

| Cu | Cu2+ | Cu2++2e= Cu | 0.342 |

| Fe | Fe2+ | Fe2++2e= Fe | -0.447 |

| Fe | Fe3+ | Fe3++3e= Fe | -0.037 |

| Mn | Mn2+ | Mn2++2e= Mn | -1.185 |

| Ni | Ni2+ | Ni2++2e= Ni | -0.257 |

| Pb | Pb2+ | Pb2++2e= Pb | -0.126 |

| Zn | Zn2+ | Zn2++2e= Zn | -0.7618 |

| Cation | Ksp(S2-) | Ksp(OH-) |

|---|---|---|

| Cd2+ | 8.0×-27 | 2.8×10-14 |

| Co2+ | 4.0×-21 | 1.6×10-15 |

| Cu2+ | 6.0×-36 | 1.3×10-20 |

| Fe2+ | 6.0×-18 | 8.0×10-16 |

| Fe3+ | - | 3.0×10-39 |

| Mn2+ | 3.0×10-13 | 1.9×10-13 |

| Ni2+ | 2.0×10-26 | 2.0×10-15 |

| Pb2+ | 3×10-28 | 1.2×10-15 |

| Zn2+ | 1.6×10-24 | 3.0×10-17 |

| Chelating resins | Functional groups | Selectivity order |

|---|---|---|

| Aminocarboxylic acid | —NC(H2COOH)2 | Fe3+>Ni2+>Cu2+>Zn2+ |

| Iminodiacetic acid | —N(CH2COOH)2 | Cu2+≫ Ni2+>Zn2+>Fe2+ |

| Phosphoric acid | —PO(OH)2 | U4+>Fe3+≥UO22+>Cu2+ |

| Polyamide | —CH2CH2NH— | Hg2+>Cu2+>Zn2+>Ni2+ |

| Dithiocarboxylic acid | —CSSH | Ag+>Cu2+>Zn2+>Mn2+ |

| Thiourea | —NC(NH2)S | Ag+>Au3+=Pd2+>Hg2+ |

| Resin type | Selectivity | pH | Max capacity/mmol·g-1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amberlite IRC-748 | Cu2+>Ni2+>Co2+ | 5.0 | 1.060 |

| 4.0 | 1.252 | ||

| 1.0 | 2.000 | ||

| Amberlite IRC-718 | Fe2+>Cu2+>Zn2+>Ni2+ | 5.0 | 2.250 |

| 4.0 | 0.95 | ||

| Lewatit TP-207 | Cu2+>Zn2+>Cd2+ | 5.0 | 0.87 |

| 4.0 | 1.38 | ||

| Chelex-100 | Cu2+>Zn2+>Cd2+ | 6.0 | 0.021 |

| 5.6 | 2.15 | ||

| Purolite S-930 | Cr3+>Cu2+>Ni2+>Zn2+>Co2+>Cd2+>Fe2+>Mn2+ | 4.0 | 0.89 |

| Lonac SR-5 | 1.0 | 1.25 | |

| Diaion CR-10 | 5.0 | 2.809 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).