1. Introduction

The Internet has revolutionized human life by facilitating information exchange across different devices. This has been possible by allowing them to be connected, forming a new network, known as the ‘Internet of Things’ of IoT. Literally, ‘

everything’ that is internet-enabled is getting connected to this network to produce smart and better solutions for the end users. The IoT is formed by connecting different types of devices to the Internet and permitting these gadgets to connect. In recent days, IoT has been widely used for commercial and emerging technology use cases, including connected homes, hospitals, aerospace, communications, and other digitized spaces. Even though the international IoT market is projected to be approximately

$14.4 trillion by 2022, this idea is still new to many consumer groups. IoT involves multiple and hybrid technologies such as wireless communication, embedded systems, machine learning, and real-time analytics. As a technology, IoT foresees a future where digital and physical mediums are linked using proper data communication to facilitate various applications and use cases in the real world. [

4,

5].

Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) or Medical Internet of Things (MIoT) is a connected system combining software applications with medical devices, which connect to different healthcare IT systems. To optimise healthcare delivery and create a reliable healthcare service provisioning environment, IoMT links patients, healthcare service providers, and medical devices in a secure way. IoMT has emerged as a dependable technology to assist medical personnel in managing patient information and delivering secure digitised healthcare services. The healthcare IoT market has been anticipated to jump from 32.47 billion USD in 2015 to 163.24 billion USD by the year 2020, at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 38.1% from 2015 to 2020[

6]. Moreover, IoT offers numerous applications and use cases in the medical sector, that can help patients, families, and doctors. In terms of connectivity and connected networks in the healthcare area, approximately 20 billion devices are likely to be in use over the next few years. [

1,

2,

6].

To capture all the information of the patients or to provide smart solutions, medical devices these days need to incorporate chips or the latest technological solutions. Remote health management, managing various diseases and conditions, fitness programs, patient monitoring at home, enduring disease conditions, and elderly patient care and monitoring are imperative use cases. Advancement in medical devices, mainly in home-use cases in diagnosing and imaging sector, plays a crucial role and is one of the vital technology components in the market. Because of the growing demands and technological facilitation, medical device companies need to provide more unique features by incorporating technology. At present, healthcare trends and requirements encompass devices featuring sensors, controllers, wireless capabilities, enhanced firmware, and remote monitoring. A connected healthcare solution offers a quick and reliable flow of information to the healthcare personnel, offering easy access and providing features to the medical workers so that they can analyze and determine the data of the patients and suggest accordingly. Hence, the patient gets a better-quality home care facility by keeping in touch with the doctors. Connected healthcare systems can also assist in identifying the stages of common diseases, for example, hypertension, asthma, and others. The requirements prompt the device manufacturers to incorporate modern technology and get them on the market much quicker [

1]. Therefore, health monitoring or medical IoT devices vary from cardiac monitoring to electronic wristbands, smart beds, medical devices, and others. The primary aim is to lower manual work and to generate opportunities for higher precision, efficiency, and profits by continuously incorporating IoT features in healthcare devices [

7]. Moreover, this system is much safer and easier to use for patients, and it permits clinicians to work on the data that the devices generate and provide much better information on patients’ well-being [

2].

Subsequently, the flexibility of gathering different sets of data and incorporating medical devices with the Medical Internet of Things allows detailed viewpoints for the clinicians to work on and to provide feedback, which helps improve patients’ lifestyles, including the home-based data attainment process [

8]. IoMT has enabled the benefit of accessing diverse datasets, enabling continuous and long-term monitoring of patients' lifestyle-related diseases. This capability has evolved to analyze and extract more substantial evidence. For instance, in sectors like dementia, where understanding the properties and changes of various stimuli over time is crucial, IoMT offers the analysis of factors such as ambient settings, intricate diagnostics, and therapeutic possibilities. However, various risks may result due to the conciliation of devices, data infringements, and privacy or policy breaches. Moreover, due to the upgrade on the device and software configurations or the changes in the system- how the data is analyzed, it might get difficult and may pose further risks [

9].

Over the last five years, IoMT applications have garnered considerable focus. Sensors and medical devices have continued to advance significantly, incorporating noteworthy features. Consequently, a multitude of solutions can now be provided for addressing diverse critical conditions. The research work in this field involves developing prototypes, working on new platforms for medical data processing and visualization, and developing new architecture, interoperability, security, and so on. As there are plenty of sensors and devices available on the market, a scenario in an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) has been considered. Moreover, policies and guidelines have been designed for installing IoT technology on healthcare devices. Hence, an extensive understanding of the contemporary deployments and technology in the healthcare field is quite fruitful for future research and further advancement of medical IoT devices. Therefore, the research puts emphasis on the recent technology of the IoT in the healthcare sector, IoT platforms for managing and processing medical data, and various use cases of the IoT devices applied in the medical sector.

3. Internet of Medical Things (IoMT)

The Internet of Medical Things (IoMT) involves the utilization of numerous sensors and various medical devices to gather patient data, which is subsequently evaluated to offer appropriate treatments and recommendations to the individual. To primarily select the suitable sensors for this review, an Intensive Care Unit (ICU) scenario has been considered. The most used sensors and the devices in any ICU in general, have been chosen and the details are provided below:

3.1. IoMT Sensors Monitoring Circuits

The Internet of Medical Things is a subset of the Internet of Things that offers enormous potential for the healthcare sector. This sector's products and services advance healthcare, ease the burden on doctors and nurses, and enable patients to get care outside of hospitals or at home. The IoMT application's framework makes it easier to combine the benefits of cloud computing and IoT technology with the medical industry. Additionally, it defines the methods for transmitting patient information from multiple sensors and medical devices to a particular medical service-providing network. The configuration of various IoT medical systems or network components that are logically coupled in a medical context is the topology of an IoMT. MIoT uses a variety of sensors, including sphygmomanometers (blood pressure monitors), thermometers, endoscopy monitors, pulse oximeters, EEG, ECG, EMG, and so on, to read patient conditions at any given time (data) [

14].

Here are a few examples of MIoT-enabled sensors, along with their circuit diagrams, that will boost the connected medical field:

3.1.1. Glucometer

The device captures the glucose information in the blood of humans. A drop of blood from the human body is positioned on a one-time test strip, which is read by the glucometer and determines the glucose level in the blood. The following figure demonstrates the glucose level monitoring circuits [

15].

Subsequently, diabetes is a health condition where the body's blood sugar or glucose levels remain elevated for a longer period. It is considered one of the most widespread illnesses. Type I diabetes, type 2 diabetes, and gestational diabetes are the three main forms of diabetes that are typically present. Three tests—the random plasma glucose test, the fasting plasma glucose test, and the oral glucose tolerance test—can be used to identify the disease and its many kinds. However, "fingerpicking," followed by the measurement of blood glucose levels, is the diagnostic technique that is most frequently used to identify diabetes. Numerous wearable devices for blood glucose screening that are non-invasive, cozy, practical, and secure have been created using recent progressions in IoT technology [

17,

18,

19,

20]. For real-time blood glucose level monitoring, an m-IoT-based non-invasive glucometer has been proposed [

21]. In this case, an IPv6 connection was applied to connect the wearable sensors with the healthcare providers.

3.1.2. Temperature Sensor

This sensor allows the patients or users to determine the body temperature, and it is one of the most important sensors as a lot of diseases change their characteristics, which can be determined by monitoring the temperature. Also, some disease conditions can be checked by evaluating the body temperature. Then the doctor or physician can determine the treatment based on the conditions.

Figure 3 contains the temperature sensor circuit diagram [

15].

An essential component of many diagnostic procedures, human body temperature serves as a sign of the preservation of homeostasis. Additionally, certain conditions, including trauma, sepsis, and others can have a change in physical temperature as an alert. By maintaining a record of the patient's temperature fluctuations over time, physicians can infer the individual's health status across various disorders. Operating a temperature thermometer that is either fastened to the mouth, ear, or rectum is the traditional method of taking temperature readings. The problem with these treatments is that they leave patients with little comfort and a significant risk of infection. Nevertheless, various solutions to this challenge have been proposed, taking into account the ongoing advancements in IoT-based technologies. An ear-mounted, 3D-printed wearable device that utilizes an infrared sensor to monitor the core physical temperature of the tympanic membrane was proposed in [

23]. A wireless sensor module and an information-processing unit were built into the device. Here, the surroundings and other physical activity have no impact on the temperature that is being monitored.

3.1.3. Blood Pressure Sensor

The blood pressure sensor captures the numbers for two different states systolic and diastolic blood pressure. It allows the doctor to monitor the cardiac conditions of the patients [

15,

24].

Figure 4 illustrates the blood pressure sensor circuit.

The pressure sensor used in this circuit is primarily intended to measure blood pressure and utilizes a ceramic chip and nylon plastic for high linearity, little noise, and low exterior stress. Moreover, it applies the internal standard method and temperature compensation method to increase precision, steadiness, and repeatability [

25]. The evaluation of blood pressure (BP) is a compulsory step in any diagnostic process. The most usual method of taking blood pressure calls for a minimum of one person to record the data. However, the method BP was previously monitored has changed as an outcome of the combination of IoT and other sensing technology. For instance, in [

26], a wearable cuffless gadget that can gauge both systolic and diastolic pressure was suggested. The information that was captured can be stored on the cloud. Additionally, the effectiveness of this gadget was evaluated by 60 people, and its accuracy was assured.

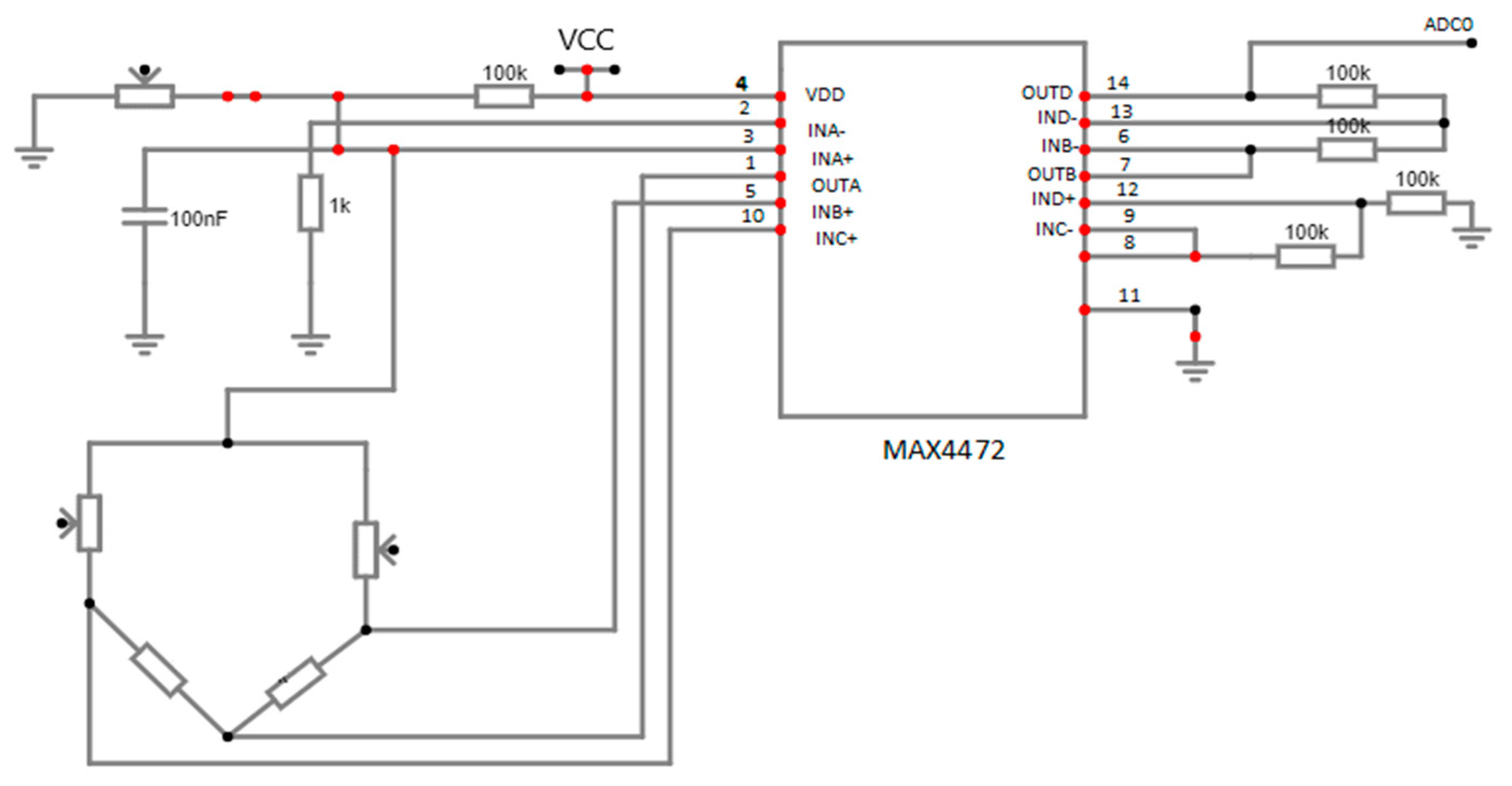

3.1.4. Airflow Monitoring Sensor

This sensor allows monitoring of the breathing rate of the patient who requires respiratory support, which helps the physician to determine the disease type and conditions, and therefore medicines can be prescribed accordingly.

Figure 5 shows the oxygen saturation circuit diagram [

15].

An important parameter in healthcare analysis is pulse oximetry, which is a non-invasive way of contemplating oxygen saturation. Real-time monitoring is offered by the non-invasive technique, which also eliminates the drawbacks of the traditional method. The incorporation of IoT-based technologies has improved pulse oximetry, which has substantial applications in the healthcare sector. A non-invasive tissue oximeter, which assesses the blood oxygen saturation level, heart rate, and pulse characteristics, was proposed in [

26,

28]. Additionally, by utilizing different connection technologies like Zigbee or Wi-Fi, the captured data might be sent to the server. A decision for medical intervention was made after considering the recorded data. An alarm strategy, which notifies patients when the oxygen saturation attains a disparaging level, was observed in another study [

28].

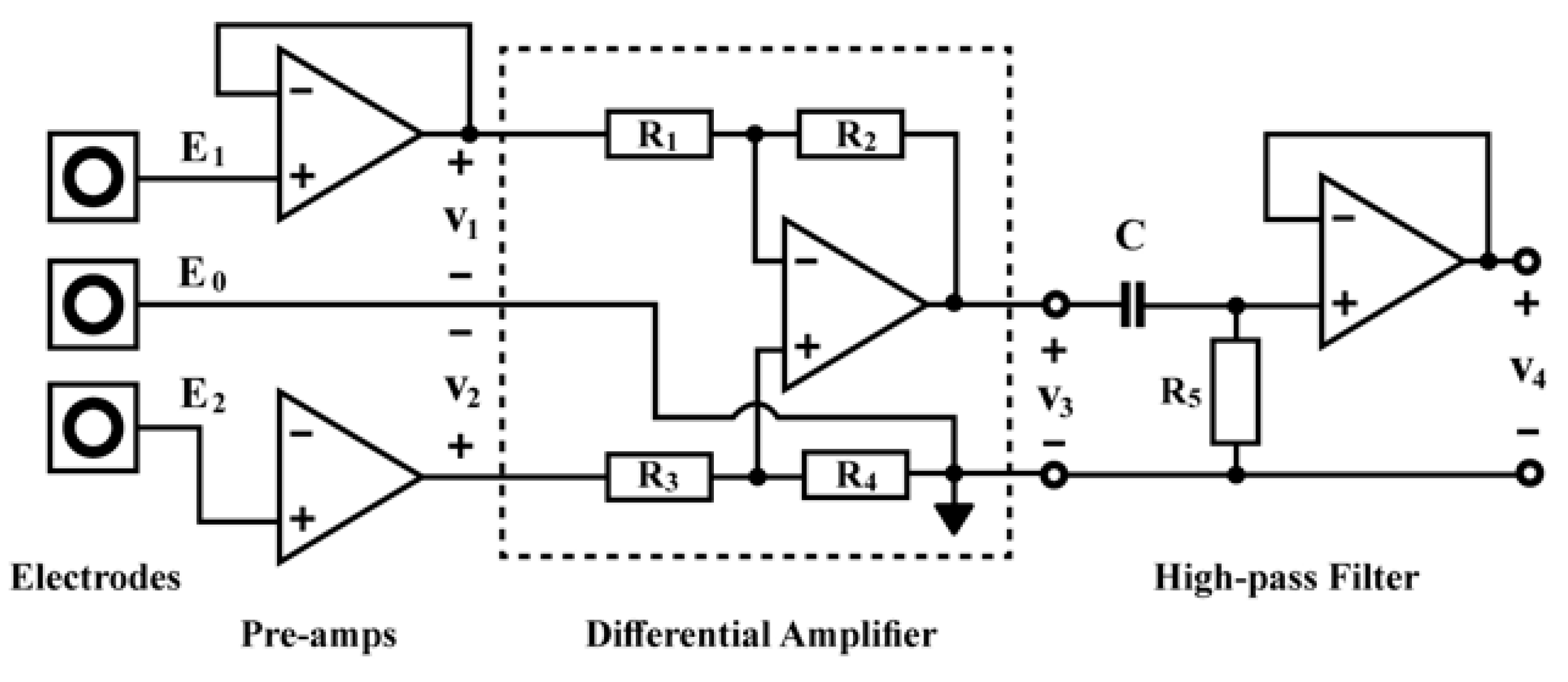

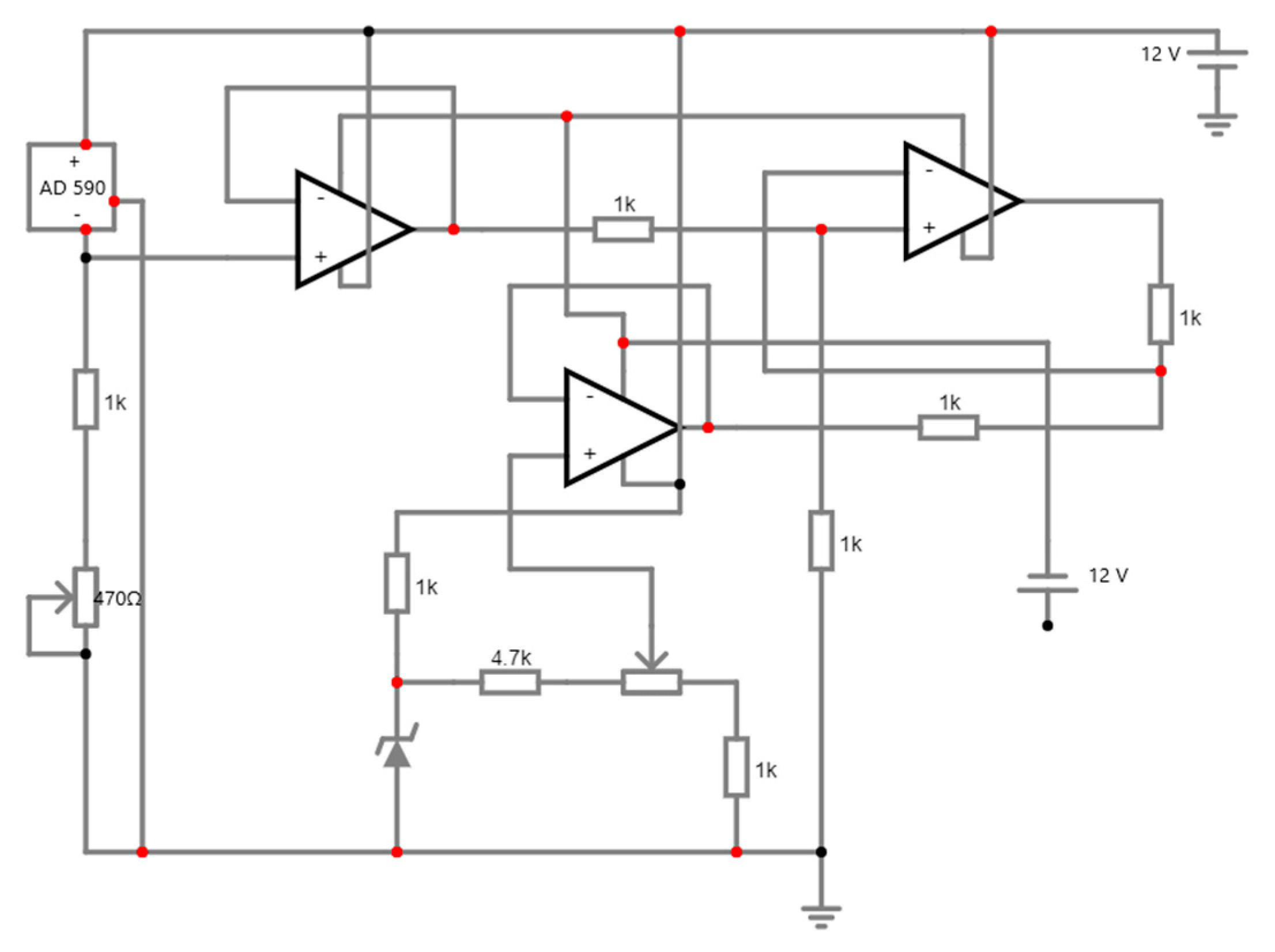

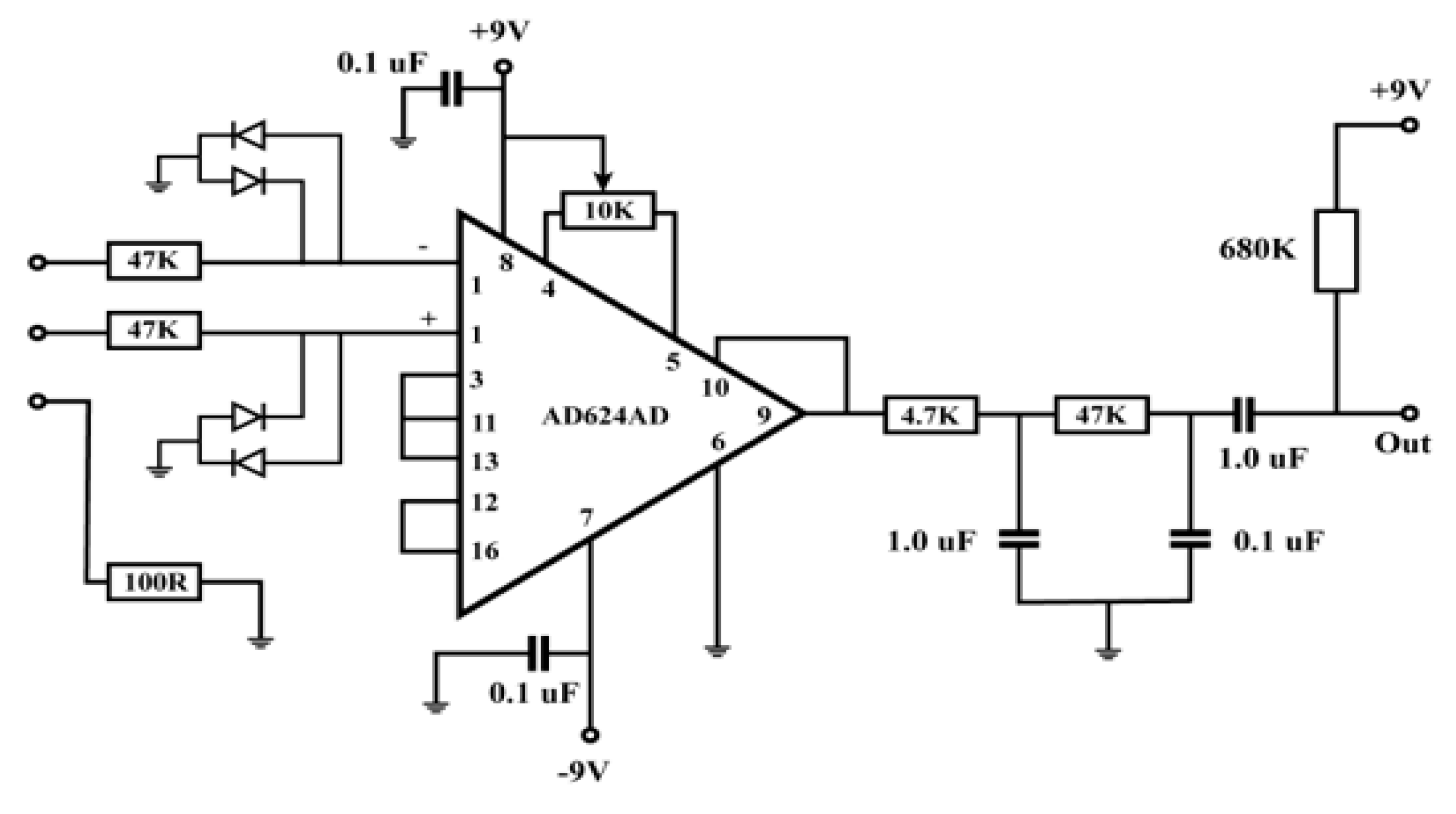

3.1.5. ECG Monitoring Sensor

The electrocardiogram (ECG/EKG) sensor is a diagnostic apparatus, that is frequently utilized to determine the electrical and muscular functionalities of the cardiac system. ECG/EKG is one of the most important medical check-ups, and it assists in assessing numerous cardiac tests, for instance, Myocardial Ischemia and Infarction, heart failure, Arrhythmia, and so on[

15].

From the figure, the amplifier receives inputs from the electrodes, which are generally connected to the body. As the signals are quite small and the amplifier can be prone to different noises, the cables connecting the electrodes to the circuit input must be carefully managed [

29]. Also, an electrocardiogram (ECG) depicts the electrical activity of the heart because of the atria and ventricles' depolarization and repolarization. An ECG serves as a tool for diagnosing various cardiac disorders and offers information on the fundamental rhythms of the heart muscles. Arrhythmia, prolonged QT interval, myocardial ischemia, etc. are a few of these problems. Through ECG monitoring, IoT technology has initiated potential utility in the primary identification of heart issues. IoT has been used to monitor ECG in numerous studies in the past [

24,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. A wireless information assemblage system and a receiving processor are the two components of the IoT-based ECG monitoring system proposed in the study reported in [

24,

35]. A search automation system has been applied to quickly find cardiac irregularities. A compact, low-power ECG monitoring system that was unified with a t-shirt was proposed in [

36]. It accumulated high-quality ECG data by applying a biopotential chip. After that, Bluetooth was used to send the recorded data to the end consumers. A mobile app could be used to visualize the recorded ECG data. A minimum of 5.2 mW of power might be needed to run the suggested system. After merging it with big data analytics to administrate increased data storage capacity, real-time screening in an IoT system may be achievable.

3.1.6. EMG Monitoring Sensor

An Electromyography (EMG) sensor is used to determine the electrical activity of muscles while inactive and at the time of contraction. EMG signals have been used in different clinical and biomedical fields. It is primarily used to diagnose neuromuscular diseases, lower back soreness, kinesiology, and motor control disorders. EMG signals are also used to manoeuvre prosthetic devices, for example, prosthetic hands, arms, lower limbs, and others [

15].

Figure 7.

Circuit diagram of EMG sensor monitoring [

37].

Figure 7.

Circuit diagram of EMG sensor monitoring [

37].

In the figure, two 9V power supplies have been connected, including the electrodes attached to the muscles measuring the voltages E1 and E2 entering the preamps around three inches apart from the top and lower end of the biceps and the reference electrode on top of the elbow. The output is then attached to the oscilloscope to check the results. While the capacitor impedes the DC voltage, the fourth op-amp operates as the high-pass filter in between the differential amplifier and the oscilloscope probe. The output can then be observed and assessed[

37].

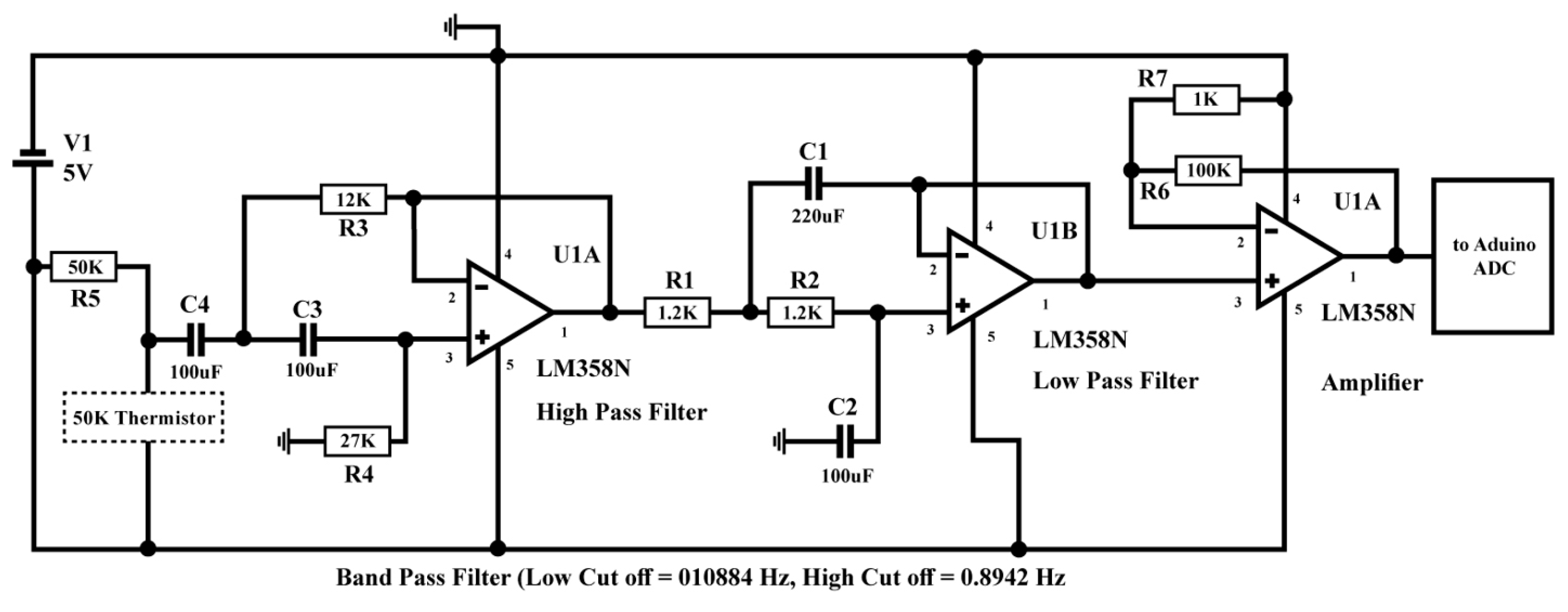

3.1.7. Breath Rate Monitoring Sensor

Persistent asthma compromises the air passages and leads to breathing issues. Asthma can cause the air passages to taper because of airway edema. This results from numerous medical conditions, such as wheezing, coughing, chest pain, and shortness of breath. An asthma attack can be triggered at any time, and the only thing that can save the patient at that point is an inhaler or nebulizer. As a result, real-time observation of this situation may be necessary. In recent years, many IoT-based systems for monitoring asthma have been developed [

38,

39,

40]. A discrete sensor was utilized to observe respiratory rate as part of a discrete IoT solution for asthma sufferers that was prescribed in [

41]. Caretakers have access to the health information saved on a cloud server for monitoring and diagnostic purposes. An LM35 temperature sensor is utilized by Raji to detect the breathing rate in his proposed respiratory monitoring and alert system [

42]. The air that was inhaled and exhaled was measured to achieve this. The health center received the respiration data, which was then shown on a web server there. Once a threshold value was obtained, the proposed system also sounded an alarm and immediately informed the patient.

Figure 8.

Circuit diagram of breath rate monitoring sensor [

43].

Figure 8.

Circuit diagram of breath rate monitoring sensor [

43].

The breathing rate monitoring circuit contains a 50K negative temperature coefficient thermistor attached to the nebulizer mask. Thermistor resistance lessens during the breath-out time because of hot air and vice-versa during the breath-in time. A change in the resistance value is then identified as an AC signal, which is passed through a bandpass filter so that the DC and high-frequency noise are removed [

43].

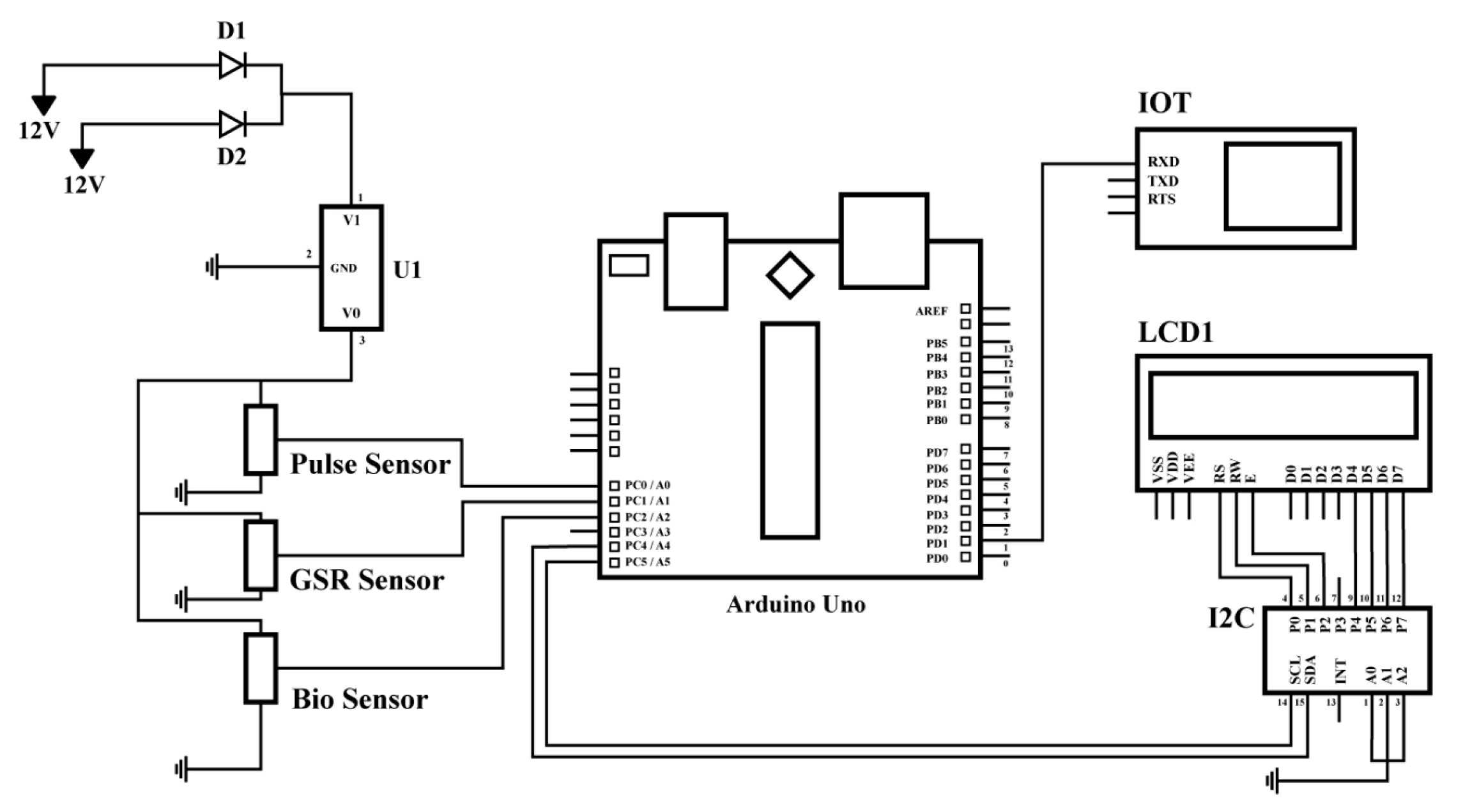

3.1.8. Mood Monitoring Sensor

Mood tracking is operated to conserve a healthy psychological state and gives important information about a person's emotional state. Additionally, it helps medical experts treat a variety of mental illnesses like depression, stress, bipolar disorder, and more. Human interpretation of their mental state is improved by individual monitoring of their psychological state. According to [

44], a CNN network is used to analyze and classify an individual's mood into six different categories: joyfulness, thrilledness, sadness, calmness, distress, and anger. An interactive technology called "Meezaj" was used in a related study [

45] to measure real-time mood. The software also demonstrated the magnitude of happiness in decision-making and helped policymakers discover the critical elements that define an individual’s joyfulness. With the incorporation of a cutting-edge machine learning structure, anxiety may now be interpreted beforehand using heart rate. The system can also talk to the patient about their stress level [

46].

Figure 9.

Circuit diagram of mood monitoring sensor [

47].

Figure 9.

Circuit diagram of mood monitoring sensor [

47].

From the figure, the GSR (Galvanic Skin Response) sensor identifies the variations in skin temperature, the abnormal cardiac rate is distinguished by the pulse sensor; and the nano biosensors monitor the blood pressure, serotine, and other relevant parameters. The data from all these components is accumulated using Arduino, which is then passed onto the IoT cloud for analysis and storage As the data can be found in real-time, nurses or any medical personnel can get a warning if depression is observed [

47].

3.2. IoMT Device Applications

3.2.1. MySignals

MySignal is a tenet for creating healthcare gadgets and eHealth software that is used to create new medical devices by adding sensors or even creating eHealth web apps. Over 20 biometric parameters, incorporating blood pressure, oxygen levels in the blood, muscle electromyography signals, glucose levels, galvanic skin response, lung capacity, snore waves, patient position, airflow, and body scale parameters, can be measured using MySignals (weight, bone mass, body fat, muscle mass, body water, visceral fat, Basal Metabolic Rate, snore, and Body Mass Index). MySignals is the most all-inclusive eHealth platform on the market thanks to its extensive sensing portfolio [

14]. Moreover, once a suitable sensor has been chosen to assess the data, it then conveys the information to the MySignals Web Server Mode [

48].

3.2.2. QardioCore

QardioCore is an ECG monitor intended to deliver continuous, high-quality healthcare information. Wearers can use these gadgets as part of their routine at work, the gym, or when out and about. According to the statistics, people can more effectively monitor medical issues, including excessive cholesterol and blood pressure. Without requiring actual visits, it also transmits data to medical facilities that keep tabs on ailments including diabetes, heart problems, and weight gain[

49]. Moreover, QardioCore ECG monitoring is a prescription-based device with Bluetooth and IoT capability, that only functions using prescriptions. Once the report has been received, it is then assessed by medical personnel and advised thereby [

50].

3.2.3. Zanthion

Zanithonis is a healthcare alert device held by a patient as a piece of jewelry or clothing. It fuels a network of linked sensors that track the wearer's well-being and health. An alarm is issued to relatives or friends who can assist if a patient falls out of bed or is immobile for an extended period [

49]. Also, inclusive of cardiac rate monitoring facilities, real-time GPS for millisecond response, and if the body temperature is not in range, mainly in the flu season [

51].

3.2.4. UP By Jawbone

A unique physical fitness tracer is available from Jawbone. Instead of merely totaling calories and steps, it may be utilized to keep track of all healthcare aspects, including weight, sleep patterns, activity levels, and food. This information can then be employed to assist the user in making well-informed and precise health decisions. Even outside of the actual medical institution, some patient advocacy organizations are using it to help people who are struggling with their weight and general health [

49].

3.2.5. NHS Test Beds

NHS test beds are intelligent, networked beds used in the UK's NHS system that track data and monitor patients. They save money and time by coalescing wearable monitors with other data sensor sources, making it possible for older patients and people with chronic illnesses to track their advancements and problems further effectively, and efficiently [

49].

3.2.6. Swallowable Sensors

A swallowable sensor allows patients to stay away from colonoscopies by ingesting a sensor the size of a cod liver oil tablet. Instead of more intrusive surgeries, this sensor can diagnose issues related to illnesses including irritable bowel syndrome and colon cancer [

49]. Recently, Hou et al. 2023 analyzed and calculated that for the radiation dose, swallowable dosimeters are five times more precise compared to the standard methods of dosage selection [

52].

3.2.7. Propeller’s Breezhaler Device

Propeller’s Breezhaler Device is a networked sensor that facilitates the administration of COPD or asthma. Every time the pump is used, the sensor, which is fastened to the top of the device, collects data. With the use of a mobile app, the user may do everything from gathering information on triggers to allow family members and doctors to control use. It is claimed to increase the number of days without symptoms and decrease the number of asthma attacks [

49].

3.2.8. Non-invasive Sensors, Microchips, and Other Miniaturized Electronics

In 2014, Google announced a collaboration with Novartis to create an intelligent and interconnected contact lens. This lens was designed to contain 'non-invasive sensors, microchips, and other miniaturized electronics.' Individuals requiring glasses for reading could employ this lens to track medical conditions such as diabetes, and it also aimed to address vision issues and restore the eye's inherent autofocus capability [

49]. Moreover, Flexible Miniaturized Sensors (FMS) for physiological monitoring are quite noteworthy due to their various applications in gathering health-related information and assessing and managing the well-being of patients [

53].

3.2.9. UroSense

For patients undergoing catheterization, UroSense is a catheter with a transmitter that tracks urine flows and basal body temperature. The early detection of infection symptoms can lead to better treatment and prevention strategies thanks to the careful monitoring of these two factors. To help manage the illnesses, the gadget also suggests conditions like diabetes or prostate cancer and relays this information to medical healthcare service providers [

49].

3.2.10. AwarePoint

Systems such as AwarePoint deploy MIoT sensors to meticulously monitor every aspect of the caregiving and caretaking process. In what they refer to as "location-as-a-service," this offers location tracing for patients and healthcare equipment. The system's goals include enhancing employee and patient happiness, streamlining asset management, and improving patient flow [

49].

3.2.11. Smart Thermometer

The Kinsa smart thermometer serves three main functions: diagnosing patient sickness, providing analysis for finer care, and mapping human illness through gathering information. Many American homes already have versions of Smart Ear and Sesame Street [

49].

3.2.12. ScreenCloud

ScreenCloud is already in use by healthcare service-providing institutions and medical professionals, with applications that go far beyond conventional digital signs. Consider the group that uses digital signs and video art to enhance patient welfare in hospitals, with impacts such as reduced tension and anxiety in patient waiting areas that can be seen [

49].

3.2.13. Medication Dispensing Service

Patients who might have trouble managing their medications on their own are the main focus of the Medication Dispensing Service and other intelligent pill-dispensing gadgets. MDS dispensers alert patients when it's time to refill their medications by pre-filling with the necessary dosage on a certain day. The information can be traced and given to the patient's healthcare service provider if a medication is missed [

49].

3.2.14. Medication Supervision

In the medical sector, medication adherence is an extensive issue. Patients' unpleasant health consequences may become more severe if their pharmaceutical regimen is not followed. Elderly persons are more likely to have medication non-adherence because, as they grow older, they capture critical diseases like dementia and comprehensible loss. Therefore, it is challenging for them to strictly adhere to the healthcare service provider's orders. The use of IoT to track patient medication compliance has been the subject of substantial research in the past [

46,

54,

55,

56,

57]. A discrete medical box that can remind people to take their prescriptions was created [

58]. Each of the three salvers in the box holds medication for three different dosages (morning, afternoon, and evening). The system also takes several crucial health measurements (blood sugar level, blood oxygen level, temperature, ECG, and so on). The cloud server is then delivered with all the recorded information. The two end users were able to communicate thanks to a smartphone app. Healthcare service providers and patients can use the cellular app to access the recorded data.

3.2.15. Wheelchair Management

For people with deficient mobility, a wheelchair is an essential component of everyday life. It offers both psychological and somatic assistance. The use of a wheelchair is, however, constrained when the condition is brought on by brain damage. This results in current research focusing on coupling these wheelchairs with the navigation and tracking system. IoT-based technologies are currently representing possible outcomes for reaching this objective [

59,

60,

61,

62,

63]. A real-time obstacle avoidance system and an IoT-based steering system have been presented in [

64]. By applying image-processing algorithms to real-time films, the steering system can recognize obstructions. Wheelchair management has become easier and more participatory for patients, thanks to the use of mobile computers. A smart wheelchair was created by fusing multiple sensors, mobile technology, and cloud computing [

65]. A mobile app that is part of the system enables patients to communicate with their wheelchairs and caregivers. The software also makes it possible for caretakers to keep an eye on the wheelchair remotely.

3.2.16. Rehabilitation System

A patient with a disability can regain functional abilities with the help of physical medicine and rehabilitation. Recognizing the issue and assisting patients in returning to regular life constitute rehabilitation. IoT is used in rehabilitation in a variety of ways, including the treatment of physical limitations including cancer, sports injuries, and stroke. [

66,

67,

68,

69]. Using a multimodal sensor that traces the patient's gait pattern and assesses motion parameters, a discrete walker reformation system has been proposed [

70]. The smart walker recorded several motion matrices such as orientation angle, elevation, force, and so forth while a patient used it. The doctors gauged this information and originated diagnostic findings utilizing a cellular phone app. Additionally, a robotic hand, a discrete wearable wristband, and a machine-learning algorithm were combined to create a stroke rehabilitation device [

71]. A low-power IoT-based textile electrode that monitors pre-processes and transmits the biopotential signal was used in creating the armband.

3.2.17. Apple Watch

To assist patients with severe depressive illness, Takeda is evaluating the use of Apple Watch software (MDD). In addition to allowing the tracking of moods outside of medical sessions, the app will look for symptoms[

49].

3.2.18. Other Notable Applications

The utilization of IoT is varied and not just restricted to certain purposes. The number of IoT applications is rapidly increasing along with the speedy development of technology. Few research fields that previously did not precisely encapsulate the integration of IoT gadgets are now efficiently utilizing this technology. This could involve the treatment of cancer, distant surgery, the identification of hemoglobin, aberrant cellular growth, etc. A brand-new IoT-based structure for cancer treatment was put forward in [

72], and it included chemotherapy and radiotherapy as well as different stages of cancer treatment. The doctors provided online consultations through a mobile app. The healthcare professional may consult the patient's lab test results that were kept on a cloud server to determine the best timing and amount to provide medication. Lung cancer detection utilizing various cutting-edge machine learning algorithms and an IoT-based system is another possible use [

73,

74,

75]. Additionally, a recent study made the case for employing an IoT-based system to identify skin lesions [

76]. The next-generation surgical training framework was created by Cecil et al. using IoT [

77]. The tool created a teaching environment through virtual reality and offered a platform for surgeons from various locations to communicate with one another. A collaborative human-robot system that can successfully carry out minimally invasive surgery has been proposed [

78]. The amount of hemoglobin in the blood can be checked with portable equipment [

79]. To measure hemoglobin, the gadget used photoplethysmography (PPG) sensors, a light-emitting diode (LED), and photodiodes. By contrasting the outcomes with the results of the recognized colorimetric test, the effectiveness of the gadget was further demonstrated.

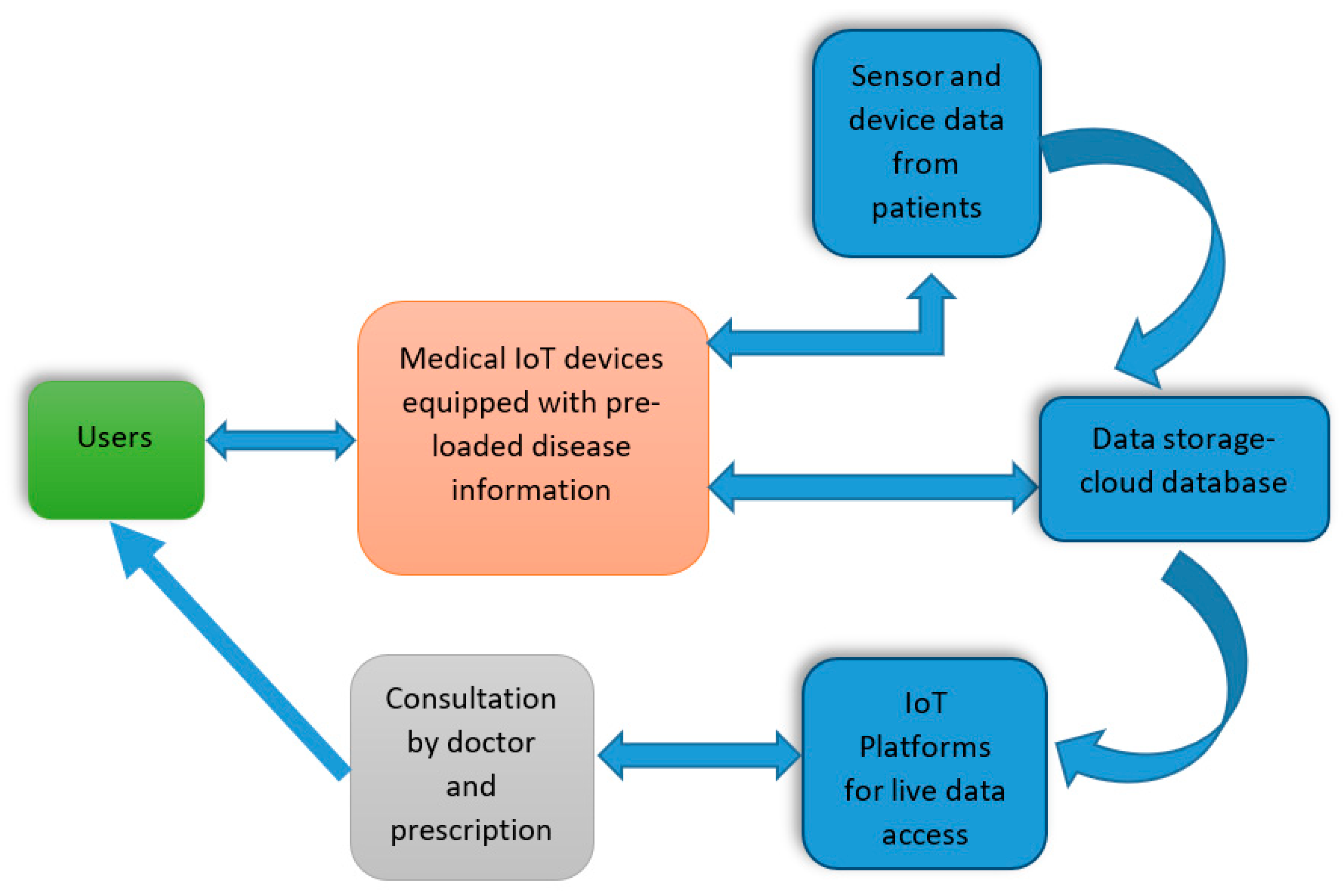

3.3. How do IoMT and its Data Storage work

In the medical field, IoMT has several usages including remote medical observation, physical fitness curriculums, identifying immedicable diseases, providing elderly care, and monitoring. IoMT has the potential to significantly improve patient experience. Hence, different healthcare gadgets, sensors, diagnostic and imaging devices are now considered as smart devices with the core section being IoT. IoT-related medical devices are anticipated to be cheaper, to provide a much higher quality of life along with an easier and flexible user experience. In the case of healthcare providers, IoT can determine the time required for the supplies and also help to minimize device downtime using remote delivery [

80]. Therefore, in general, IoT IoT-based medical devices will capture patient data from different sensors, match it with the existing symptoms or the data inserted to validate the diseases, and then store it in the Cloud or other different databases. The doctor can then look at and authorize medicines or further testing as required. The following diagram demonstrates a simplified way of the working procedures of medical IoT [

15]:

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram of data storage in IOT system [

15].

Figure 10.

Schematic diagram of data storage in IOT system [

15].

Users: The user will enter their details, which will be stored in the system along with their disease symptoms.

IoT Devices: The medical IoT devices will capture and match the patients’ data with the pre-loaded disease symptoms and process them further to analyze the details of the disease and suitable cure for the patients. However, if the disease symptoms and details are not found in the system, then the system contacts the doctor, and the doctor will discuss the details with the patient (user), diagnose the disease, and perform tests. Once the doctor has more information on the disease, the results and related data are then uploaded to the system. Information about patients and their diseases is stored in the Cloud and database system. When the output matches with the disease information, the system produces the required prescription, consisting of general medicines for the defined disease.

Sensors: To conduct diverse tests for disease diagnosis on patients, various types of sensors can be integrated into medical IoT devices. For instance, include sensors like glucometers, temperature sensors, ECG/EMG sensors, and more.

Data Storage- Cloud Database: As the central IoT device will store all patient information in the cloud-based database system, it can perform future analysis for others. The database will store patients’ details, disease symptoms, and diagnosis results, information regarding the tests that were performed along with the reports and results, prescription and medicines, consultation details of doctors and physicians, sensor, and device information of the location of login and device monitoring on cloud.

IoT Platforms: From the cloud, doctors and medical personnel can easily access the detailed information of the patient as well as live data coming directly from various sensors and gadgets.

Consultation and Prescription: Based on the input provided by the patient and the detailed diagnosis of the disease, the IoT device will try to match suitable prescription information in the pre-loaded prescription file, including proper medication, and then notify back to the user. Moreover, users can also check the details and query if there is anything that needs clarification.

Subsequently, medical IoT devices can also be connected using wireless re-programmable devices and sensors, which consist of healthcare software applications or Apps installed on cellular devices. A MIoT system is considered as a healthcare system that includes observing and assessing medical devices. These devices can track patients’ health remotely and back to the database. The back-end system then inspects the received data and provides warning signals to the doctors. Hence, the doctor can assess the warnings and prepare for any emergencies if needed. In more general terms, the data extracted by monitoring devices (such as smart watches, cell phones, etc.) seem to be quite complex and are usually compared against the medical data of the patients. Therefore, this structure can be utilized in household care units, clinics, and other places. The IoMT structure portrays a complex ecosystem that consists of different elements and arrangements such as healthcare gadgets, smart devices, hubs, gateways, Cloud services, databases, big data, clinical information systems, etc. However, similar to any new technology, MIoT also faces various challenges for instance, interoperability, functionalities, device constrictions, and security [

9]. Advanced medications and processes using MIoT would certainly elevate the quality of life for patients.

In recent times, physicians have increasingly depended on intelligent medical devices as their primary approach to disease detection. These medical devices, from a bigger standpoint, have minimized the workload of the medical service providers by observing the patient’s physical condition and proceeding with pragmatic steps if there are any significant changes in the patient’s data [

15,

80,

81].

Subsequently, technological innovation in fitness devices have also attracted a vast number of customers seeking heart rate monitoring, temperature reading and calorie consumption and burned rate, etc. Since the devices enabling these features are very user-friendly, it is expected that the market demand will increase globally in the coming years. In terms of products, the global market is divided into three categories - therapeutic gadgets, diagnostic and observing devices, and injury prevention and reformation devices. Within this group, the diagnostic and observational device is deemed to have a dominant position in the global market. This is due to its attributes such as convenient retrieval of fitness information, accurate measurement of health data (such as diabetes, blood pressure, etc.), and the availability of these devices across a wide range of prices, all of which contribute to the segment's leadership. Also, as people become more aware of their fitness the diagnostic and observing device section is therefore expected to manipulate the market. An IoT-oriented medical system is a key to the substantial growth of ‘connected’ medical systems. Features such as tracking, tracing, and monitoring the patients are pivotal for the connected healthcare system. However, reliance on IoT in the health care system is on the rise due to the modern world’s demand for enhanced quality of medication and care while simultaneously reducing the cost. In fact, for general queries, IoT, in fact, eliminates the need for a doctor as the system can monitor the patient data using different sensors and a cloud-based complex system to evaluate the accumulated information and transfer the results wirelessly to the healthcare professionals for further investigation if required [

81].

Capturing the health data of the patients is very important irrespective of whether the data is generated from electrocardiograms (ECG/EKG), fatal monitors, blood sugar levels, or temperature monitors. This data would necessitate examinations by medical professionals, opening up possibilities for discreet electronic devices to generate more crucial data and decrease the requirement for continuous doctor-patient interactions. A recent application of IoMT involves the installation of smart beds in hospitals, allowing nurses to monitor patients who may experience difficulty in getting up and tracking the bed when it is in use. These beds are also able to axiomatically regulate the proper force and support the patient without any physical involvement [

81]. Given the current inclination towards a connected healthcare system and extensive utilization of healthcare technology, the concept of developing a ‘Smart Hospital’ is estimated to materialized by 2020 [

82]. Therefore, companies interested in healthcare technology gravitated to invest largely in IoT.

At present, many electronic devices offer some sort of connectivity, ranging from biosensors to X-ray machines with Wi-Fi or Bluetooth capability. Another prime example of the IoT-based system is the Chic Fridge by Weka designed for vaccines. Its primary objective is to address vaccine management concerns, for example, keeping the vaccines in indorsed temperature, consistency of electricity supply, and inventory mismanagement. The Weka Fridge provides remote monitoring to ensure vaccines remain at the proper temperature and a self-operating log system can confirm the updated information on the stored vaccines. Upon the physician’s request, the smart fridge can offer the vial without disrupting other medicines. In addition to the simplified process of obtaining the vaccines, this fridge also allows physicians to access the data to be processed and to develop a better vaccine plan [

7].

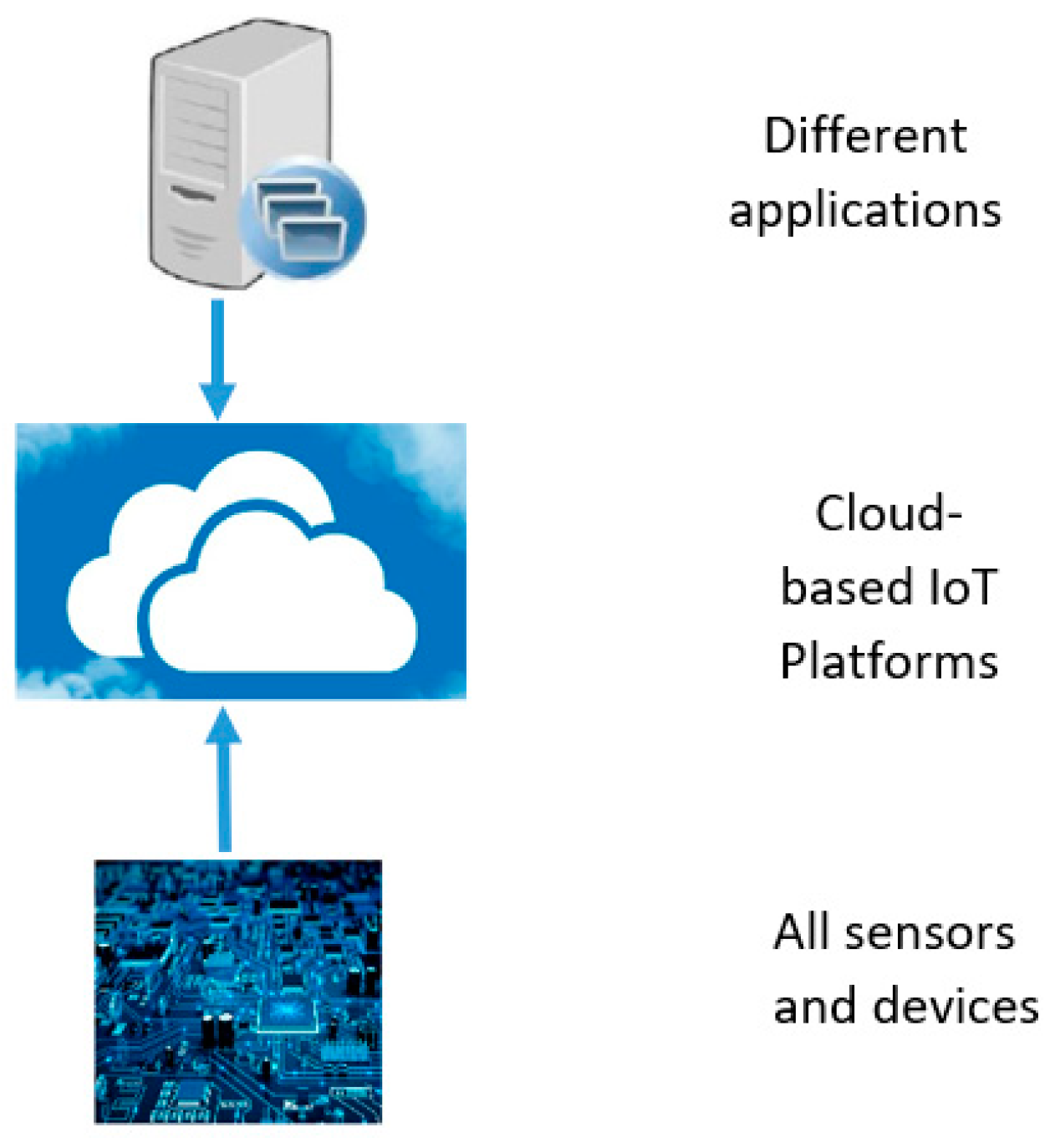

3.4. IoT Platforms

An IoT platform contains multi-layer technology enabling provisioning, managing, and automating the connected devices in the IoT space. It generally connects hardware to the cloud via different connectivity options, enterprise-level security mechanisms, and extensive data processing capability. For developers, an IoT platform offers a set of established alternatives, which facilitates the integration of applications for connected devices, scalability, and compatibility [

83]. The following block diagram demonstrates how the IoT platform interacts with the hardware and the applications.

In

Figure 11, IoT functions as ‘middleware’, connecting hardware with various applications. Hardware can include sensors, devices, mobility, tags, beacons, health and fitness devices, consumer electronics, automotive, embedded hardware, and so on. Applications could consist of data storage and analytics, consumer applications, industrial applications, business applications, healthcare, and more [

83].

There are various IoT platforms available for different applications and one of the noteworthy IoT platforms in medical service is the Kinect HoloLens Assisted Rehabilitation Experience (KHARE). Microsoft Enterprise Services, in collaboration with the National Institute for Insurance Against Accidents at Work (INAIL), emulates the efferent neuron therapy capabilities. Using KHARE, physicians can access real-time data feeds, enabling them to assess and develop medications for patients from their physical locations. Integrating with Microsoft’s Azure IoT Suite, this platform allows healthcare professionals to access the information from half an hour therapy session. This tenet is undergoing a clinical investigation, which was supposed to be completed in January 2020. Moreover, IoT information analysis programs for instance, Kaa (KaaIoT Technologies), MindSphere (Siemens), and Azure (Microsoft) permit information to be organized and accumulated from the respective IoT gadgets to conclude a significant result [

7].

The hospitals in Singapore are also establishing digital platforms for the patients who have been discharged from the hospitals. These platforms enable patient care and access to different healthcare providers aiming to reduce cost and time spent on hospital visits and follow-up. Due to the challenges in the healthcare system, related to costs, gaining access to health records has developed health services remarkably with more features and solutions. Hence, ‘smart’ healthcare systems provide upgraded services to the patients offering more options to the medical teams and also alleviating the business of healthcare systems [

82].

As a result, several health insurance companies are exploring digital platforms, which include wearable devices and sensors, focusing on wellbeing and acute disease management. Also, by offering incentives and rewards, the patients can be motivated to adopt healthy lifestyles consequently, lowering the expenses of supporting medical service personnel and medical service insurers. This digital transformation in the healthcare system is going to draw the attention of ‘health tourism’, incorporating advanced features, for instance, telemedicine for pre- and post-treatment check-ups, digital record management, and technological development in healthcare such as precision medicine, limited surgery, and digital laboratory analysis. Shortly, countries with significantly massive investments in the IoT space will assume a major role in the medical tourism market. Furthermore, the processing and management of digital medical records are operated by digital transformation. Healthcare Information Systems (HIS) are slowly shifting from conventional paper-based records to Electronic Medical Reports (EMRs), serving as a pivotal advantage and catalyst for the digital transformation. This offers a seven-step process which is suggested by the Healthcare Information Management Systems Society (HIMSS) for hospitals to transform into ‘paperless hospitals’ [

82].

Therefore, it can be understood from the analysis that the IoT platforms can comprise diverse information about the patients where the medical doctors can retrieve the detailed history of the patients along with the latest updates and offer appropriate suggestions. Furthermore, users can also instantly contact medical personnel for emergencies or queries, which results in time and money savings. To understand how medical IoT devices work, a case study on COVID-19 has been considered.

3.5. Case Study of COVID-19 Assistance using IoMT

The applications of medical IoT devices in the health sector allow medical centers and staff to operate more efficiently. Internet of Things (IoT) devices utilized widely across various applications in recent years, including discrete urban areas, factories, households, automation, and medical [

84]. Sensors are used in these devices to collect data about the physical environment. The world's healthcare system is currently facing significant strain due to the COVID-19 outbreak.

A slew of additional forecasts was triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Internet of Things is anticipated to perform a vital position in the emerging new normal scenario. This article presents analyses, and suggests IoT-inspired applications in many industries amid the pandemic, along with challenges and potential beyond the crisis [

85].

Numerous wearable lightweight IoT devices [

86], p. 1 are accessible which have the potential to mitigate infectious diseases like COVID-19 and ameliorate medical solutions. Monitoring a limited number of symptoms becomes easier with the utilization of IoT devices. After identifying viral symptoms, the gadget can alert both the user and the nearest health agency. This can improve the effectiveness of medical intervention, enabling the identification, scrutinization, and rescue of individuals in deprecatory conditions (e.g., cases where the patient is unable to reach the medical professionals at the appropriate time due to symptoms). Furthermore, this can be transferred to other departments to find a rapid remedy and ensure the safety of the public. Monitoring patients from a considerable distance with the utilization of technologies such as 4/5G and the cloud is considerably easier, especially for people who find it challenging to contact or access medical institutions.

Another advantage of IoT gadgets in the medical sector is their ability to reduce human errors that are more common than machine or AI faults. Considering that humans are imperfect, IoT can provide more accurate diagnosis and patient reporting.

The Internet of Things (IoT) technology plays a vital part in identifying the virus through fever tests, considering some of the virus's symptoms, as well as in restricting its spread by enforcing social distancing. Moreover, it helps in the supervision of remote health observation, pollution and air quality management, occupancy control, and smart parking. Fever screening eliminates the need for human interaction and allows for the identification of several targets. Sensors and cameras provide color temperature scales and images. The first line of protection against the virus is the pre-screening of personnel, disaster evacuees, or patients [

87]. While viral detection is not ensured, it can be used to assess whether the person has virus symptoms. Subsequent inspections are then conducted for a definitive conclusion.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus causes COVID-19, which affects the respiratory system. In [

88], researchers suggest a wearable strain sensor capable of detecting the rate of breathing of the user and the volume of the user’s respiratory system. By using the Internet of Medical Things (IoMT), these sensors continuously track and monitor patients' breathing conditions, providing constant updates to the involved clinicians regarding the patient's respiratory condition. This not only saves time but also allows the concerned healthcare service providers to make suitable suggestions remotely. The authors of [

87,

89] focus on a wearable IoT-based stress detection device. This offers a suitable option for individuals experiencing worry, anxiety, and isolation because of the epidemic.

During the COVID-19 epidemic, contact tracing has been proven to be an effective way to secure personal information while keeping people well. Wearable light IoT devices, such as the Triax Proximity Trace, employ contact tracking to remove social distance by alerting users when they are not maintaining proper distances [

90]. Enterprise departments can deploy wearable gadgets that enforce safety requirements without requiring cellular phones or downloads. Tags are transmitted via Bluetooth technology, which eliminates the urge to trace a user's location. Filtered keys that alter every 15 minutes are also employed to secure users' privacy. The Alberta government has released a COVID-19 contact tracing application. The software verifies positive instances and alerts Canadians who have been affected [

91].

Amidst the pandemic, medical personnel affiliated with ambulance services contend with the highest level of stress and discomfort. Integrating IoT-assisted technology in ambulances provides time-saving solutions by allowing specialists to guide employees on important procedures for managing patients during emergencies [

92]. IoT-based Emergency Medical Services (EMS) are considered excellent methods for saving lives in life-threatening circumstances. The authors of [

93] suggest a structure that delivers real-time information on the number of accessible beds, all forms of blood levels, blood type availability, and doctor accessibility. During such enormous incidents with several victims, the ambulance can provide real-time data.

A system based on the IoT-based system has been developed to identify coronavirus-infected individuals in the early stage. To diagnose suspected cases of COVID-19, faster region CNN with ResNet101 (FRCR) was used. The FRCR has a remarkable 98 percent accuracy rate [

94]. For automated testing of COVID-19 from chest CT images, an attention-based deep 3D multiple instance learning (AD3D-MIL) method was developed [

95]. The Bernoulli distribution of labels was used by AD3D-MIL for efficient learning.

The extensive array of network devices within the IoT detects and notifies about different types of illnesses, contributing to the establishment of a discreet network for overseeing the medical service provisioning system. Patient data is gathered autonomously, which can be highly advantageous in decision-making processes.

Using the generative adversarial network, an auxiliary classifier model was created to generate synthetic chest X-ray images (GAN). This model was developed using the name CovidGAN [

96]. CovidGAN effectively distinguished COVID-19 from other viral pneumonia using CovidGAN. CovidGAN was tested using 192 chest X-ray pictures. However, CovidGAN does not do cross-validation. Using ultrasound, X-ray, and CT scans, deep learning models were employed to detect COVID-19 suspicious cases [

97]. VGG19 was used to create an automated categorization method. A pre-processing approach was utilized to mitigate sample bias and improve image quality. Data fusion strategies, on the other hand, can improve classification accuracy. For the categorization of COVID-19 suspicious instances, Additionally, a CNN-based transfer learning architecture was presented [

98].

In this suggested system, eight pre-trained CNN models were used: ResNet18, Inceptionv3, SqueezeNet, MobileNetv2, ResNet101, CheXNet, DenseNet201, and VGG19. This framework underwent evaluation with 423 COVID-19 pictures, 1485 viral pneumonia images, and 1579 normal chest X-ray images. To identify COVID-19 infection from other diseases, a 3D convolution neural network (3DCNN) was created [

99].

DCNN employed an online attention refinement and a dual-sampling approach. This network was utilized to isolate the infection locations and remove the uneven distribution of pneumonia-infected regions. DCNN’s performance was assessed using 2796 CT scan pictures from 2057 patients. However, the precision of the affected area is still lacking [

99]. To categorize coronavirus-infected people using chest X-rays, a deep learning-based chest radio classification (DL-CRC) system was proposed [

98,

99]., DL-CRC employed a generative adversarial network and data augmentation to generate simulated coronavirus-infected X-ray images. Four distinct chest X-ray datasets were used to evaluate DL-CRC.

Medical IoT devices have played a significant role in the battle against the COVID-19 outbreak. Deep learning models based on IoT have alleviated the workload of healthcare personnel and doctors. However, IoT-based deep learning models, which overlook protective measures against adversarial anxiety, remain still susceptible to adversarial assaults [

99,

100].

The Internet of Things (IoT) employs a multitude of networked gadgets to establish a discrete network for the appropriate medical service management. It monitors and alerts for any type of ailment to ensure patient safety. The patient's information and data are digitally recorded without the need for any human assistance. This data is also beneficial for taking suitable decisions [

93,

101,

102,

103,

104].

To fight this pandemic effectively, rapid diagnosis of individuals with COVID-19 is of utmost importance. IoT devices play a vital role in remotely retrieving information from COVID-19 patients for this purpose. This data is transmitted to medical personnel for COVID-19 diagnosis [

105]. These gadgets not only alleviate the burden on healthcare staff, but they also spot unexpected patterns in sensor data [

98,

106]. By using IoT-enabled devices, healthcare personnel deliver better treatment for coronavirus-infected patients at a faster pace. There a need arises for the development of an automated categorization system using the data provided by IoT gadgets. In recent times, a significant number of academics engaged deep learning models to serve a variety of healthcare applications [

8,

14,

24,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

49,

96,

107,

108,

109].

About the recent achievements in utilizing deep learning models for automated coronavirus detection, an ensemble deep learning framework based on IoT has been developed. The suggested ensemble model aims to assist radiologists and medical personnel in classifying suspected patients as COVID-19 (+), pneumonia, TB, or healthy. A combination of InceptionResNetV2, ResNet152V2, VGG16, and DenseNet201 contributes to the creation of a deep ensemble model [

110]. The medical sensors can capture the chest X-ray modalities and use an ensemble deep transfer-learning model, storing them on a cloud server to identify the illness. For the experimentation, a chest X-ray dataset with four classifications (COVID-19 (+), pneumonia, TB, or healthy) was employed.

As per the comparative study, the suggested model is expected to assist radiologists in effectively and swiftly identifying patients with COVID-19 suspicions. AD3D-MIL was trained and evaluated on 460 CT images. Furthermore, by using CT scans, a multitask multiline deep learning system (M3 Lung-sys) was developed to detect coronavirus-infected people [

111,

112,

113].

Table 3 below outlines the COVID-19 assistance using MIoT devices, software, services, models, and networks including features, pros, and cons:

4. Discussion and Challenges

The applications of medical IoT devices in the health sector offer medical centers and staff the ability to function more efficiently, while patients also get better options for treatments. Through this technology, patients can receive all the necessary care they need at home without visiting the doctors every time.

However, the medical IoT also faces several difficulties. For instance, certain devices have been hacked. To keep track of the total number of associated devices and the vast amount of personal data these devices could accumulate a substantial risk for cyber security. The FDA in 2017 took an exceptional decision to re-collect 450,000 pacemakers as these devices were found to be at risk of cyber-attack. Johnson & Johnson also issued a warning to their customers regarding a security malfunction in one of the insulin pumps. An investigation conducted by Synopsys found that only 51% of device manufacturers and 44% of healthcare companies adhere to FDA guidelines to lessen the security risks in medical equipment on medical equipment. In July 2015, the FDA issued a warning underlining the threat of cyber-attack on the infusion pumps. Subsequently, in 2016 FDA released device ‘guidance’ concerning post-market management of cyber-attacks for medical equipment. FDA mentioned that all medical equipment carries an undeniable risk of being attacked, but when the advantages to patients prevail over the risks then such equipment is permitted for marketing. Even though the rise in wireless technology and software in medical equipment has the probability of cyber-attacks these traits also offer advanced health care opportunities for patients, ultimately reducing waiting times [

1].

Therefore, MIoT devices are profoundly changing the nature of healthcare, for example impacting treatment, monitoring, and overall lifestyle improvement. Worldwide nations are encountering difficulties in enhancing healthcare services. However, the latest advancements in the field of sensor, internet, cloud, big data, and others offer substantial healthcare options but these connected IoT devices are at risk of security contravenes. Statistics show that device manufacturers often overlook many security protocols during development [

1].

Moreover, unauthorized access to these IoT devices can also lead to potential harm to patient’s information, health, and safety. Hence, authentication and encryption could help solve these issues. The ability of healthcare companies to effectively gather and represent the data properly will certainly affect the future of MIoT. It should be noted that IoT will not reinstate healthcare organizations, but it helps in collecting all necessary information for the medical personnel to properly diagnose and treat patients. So that it can minimize the problems and incompetence in the healthcare sector [

2].

Table 4 summarizes the details about the IoMT devices including their features, pros, and cons.

Even though there are numerous of challenges in using MIoT, different use cases provide effective solutions for the patients and doctors. The quality of life is also improving through the applications of MIoT. With the availability of 5G technologies, medical applications will further enhance and will become more efficient in providing remote prescriptions or even surgeries. Moreover, all microchips are becoming even smaller, and with the application of nanotechnology, medical devices using IoT platforms are also being miniaturized. For instance, smartwatches using 5G technology will be able to provide more control for the patients and doctors, including features like prescription updates, capturing, and sending photos, etc. Precisely, Atrial Fibrillation (AF) is one of the most common cardiac arrhythmias and a primary source of deaths worldwide. Many people are living with AF unknowingly. When atrial fibrillation is detected and addressed, treatment is possible for two out of every three instances of strokes. Hence, there is a potential opportunity to work in this sector, where real-time tracking solutions for AF can be further developed to avert the leading cause of death [

1]. Furthermore, 5G technologies, with their higher data rates and lower latency, will be more effective in providing faster solutions as required. Additionally, the inclusion of VR with 5G will certainly help medical teams and patients in arranging virtual meetings and consultations, as well as monitoring and managing the entire proceedings seamlessly. Even 10 years ago, this technique was impossible but with the latest advancements in technology and wireless applications, it is no longer farfetched.

Subsequently, the treatment of more complex diseases such as Parkinson's disease, kidney failure, intestine complications, stones in the gall bladder, arms, ankles, feet, and others could be easily observed and prescribed by the doctors immediately. This would enable patients with critical concerns and urgent needs to contact medical personnel without any further delay. Hence, the fields of telehealth and telemedicine are expected to grow to fulfill the demands of both patients and healthcare service providers.

Moreover, Artificial Intelligence could play an imperative role in the applications of IoMT. For example, continuous tracking and management of drugs could be managed by AI and it could also provide regular updates on patients’ conditions. Additionally, smart hospital beds and even basic queries could be implemented through IoMT devices. Deeper analysis can be made with the assistance of AI as it can make decisions based on previous records and patients’ medical histories, eventually suggesting alternatives to medical personnel. This would save more time and generate smart when needed.

4.1. Views

The paper conveys the message that the recent improvements have demonstrated IoT technology as an integral component of day-to-day operations, ensuring that its users remain on the proper and quick processing track. Particularly, Within the medical industry, IoT can make everyone's life simpler by processing and controlling the complete system. In this system, medical equipment is interconnected, along with access to an online database. Doctors can verify the changes frequently, saving the data. Meanwhile, patients can also update their ailments regularly.

Any IoMT project must include R&D and expanding it could be the initial approach toward project success. The medical industry can reduce risks, optimize costs, and treat patients more efficiently by utilizing a variety of IoMT applications. R&D teams oversee both the technical and medical components of an IoMT solution. They determined the application's usefulness and its potential for integration into the medical field. Additionally, R&D teams may explore potential opportunities in the future. The study's findings, prototypes, and more precise guidance regarding the IoMT product should be the final output. Before it becomes a product, the R&D team can study the concept to help shape it into a useful tool that addresses medical problems. The target audience of this paper is the research and development department of the medical industry. IoMT becomes a wonderful complement to current R&D procedures as the medical industry integrates it into its operations. R&D and MIoT can collaborate to increase value in the following ways:

Improved ROI for R&D: Compared to traditional methodologies, numerous industries utilizing IoT have claimed faster ROI on projects. Therefore, R&D experts in the medical and healthcare industry can now concentrate on real-time process data with previously unattainable accuracy levels due to incorporating data that covers everything. Additionally, it removes much of the uncertainty from projects by allowing them to concentrate on development towards current demand.

Innovative Products: IoMT holds the potential to offer fresh tools for R&D within the medical sector. This can be illustrated through the application of digital twins. Utilizing sophisticated data analytics, actual variables are employed to simulate a 3D representation of a new or improved product, enabling predictions related to wear, output, quality concerns, and lifespan. This lowers the number of prototype iterations, hence lowering the cost and speeding up the time to market. Engineers and technicians can thus refine the product before prototyping. The basic capabilities of IoMT technology serve to inform and invigorate the R&D process for the medical industry. This is achieved by the analysis of highly precise data and the incorporation of new process enhancements into existing product lines.

New Services: IoMT applications can provide different innovative services that are time adjacent. Medical industry R&D can collaborate with IoMT to develop new medical services providing ideas and applications for the medical industry.

Sustainability: Many industries are striving to enhance their production methods to make them more sustainable. While this is true for most industries, it is particularly important for sectors like the food and medical industries, where issues such as waste, spoilage, and shelf life are important concerns. To identify and tackle the core causes within the medical industry’s service provision and operations, employing IoMT is appropriate. This allows them to establish R&D initiatives that will increase sustainability in the medical industry.

Cost Reductions: Cost is undeniably a factor that every industry addresses. R&D teams can focus on profit generation and improved service provision in the medical industry due to the ability to use real-time production data, customer feedback, and lifecycle tracking. These automated digital technologies help to produce a more agile R&D effort when combined with the strength of sophisticated analytics, machine learning, and AI within an MIoT platform. It is proved that R&D, incorporating IoMT into their toolkit, is responsible for the enhancement of current processes and the introduction of new ones optimized using MIoT data.

Hence, MIoT programs in the clinical area possess limitless possibilities and vast gaps that can be narrowed by transforming them into game changers in the upcoming years. By integrating with IoMT, R&D in the medical sector can improve the functionality and adequacy of service provision in the healthcare industry. As a result, the target audience of this paper is primarily related to the R&D of the medical industry.

4.2. Future Aspects

The tech companies in the healthcare sector are striving to reduce the cost of treatment, make healthcare more accessible, and ensure the availability and protection of data. The following digital ingenuities have reformed healthcare and will continue to bring about even more changes shortly [

82].

Telemedicine: This process has been considered by many as a better approach to managing acute diseases compared to regular office visits. It offers patients convenience and freedom, thereby making healthcare services beyond a specific location or office. Also, patients residing in rural areas can access the data using electronic devices. Furthermore, it saves time and money, while also enabling quick interaction with the doctors without the need for physical presence in the hospitals.

Wearables and Digital Sensors Biotelemetry: Diagnostic procedures have been integrated into smartphones and other wearables using advanced sensors through digitalized healthcare. This allows users to monitor their heart rate, blood glucose levels, blood pressure pulse, and oxygenated blood saturation levels. The most prevalent type of wearable technology includes fitness-tracking bands and smartwatches. Fitness bands such as Fitbit, monitor exercise levels by measuring the user's step count, number of stairs climbed, and how many calories have been burned. Similarly, smart watches, for instance, the Apple Watch, Samsung watch, etc. also nowadays have a similar capability and can offer near-accurate measurements.

Furthermore, patient information is captured by Biotelemetry using digital sensors, enabling the patient to observe the vital signs, for instance, changes in the cardiac rate within a specific time frame during the day. The health professional can assess this data to make decisions and to take necessary pre-emptive actions. The findings can also produce a pool of big data, which holds significant value for scientific and research purposes.

Virtual Rehabilitation: In the year of 2016, the National University of Singapore initiated an IoT-oriented reformation for patients who had experienced cardiac arrest. This rehabilitation encompassed employing wearable sensors to observe patients’ daily activities and documenting the results, while physicians guided them via smartphones or tablets. Providing regular therapy without requiring patients to commute to the hospital or the rehabilitation center, would save both time and money. It also reduces the cost of hospitals regarding sending healthcare professionals to the patient’s home.

Intelligent Fabric: This technology revolutionizes workplace design through the application of artificial intelligence (AI) and virtual reality (VR). Installations can be completed much faster using intelligent fabric, which enables self-attachment, while AI automates auto-configuration of virtual structure and, as a result, the design of technology amenities.

Subsequently, the COVID-19 pandemic has triggered discussions about the future of IoT in healthcare and its potential to securely connect healthcare professionals and patients beyond the expanding healthcare IoT market. To continue treating these patients without increasing their risk of infection through care facilities, hospitals, and clinics were compelled to swiftly adopt telehealth. Additionally, hospitals are under constant pressure to find methods to save expenses. Wearable technology can reduce the resources required at the healthcare facilities, allowing some patients to receive treatment, and monitoring from their home.

The advent of 5G networks, which offer connectivity that is 100 times faster than conventional 4G networks, is another technology shaping the future of IoT in healthcare. IoT devices depend on connectivity for data transfer and communication between the patient and the healthcare professional. Due to the swifter cellular data, IoT devices can efficiently exchange significantly larger volumes of data at an accelerated rate. With these advancements, new healthcare IoT applications include tools for aiding patients in adhering to their medication routine at home; sleep monitoring tools capable of tracking heart rate, oxygen levels, and movements for high-risk patients; remote temperature monitoring tools; and continuous glucose monitoring sensors that connect to mobile devices and alert patients and clinicians about changing blood sugar levels.

The increase in IoT adoption can be connected to both recent advancements and the continuous impact of the pandemic. These factors serve as incentives for individuals to welcome the technology, even if they had reservations in previous times.

With the increased utilization of cloud services and AI, IoT devices are evolving into smarter tools that carry tasks beyond the basic transmission of data from patients to healthcare professionals. Smart glucose monitoring systems and smart insulin pens are two examples of IoT devices that leverage cloud services for data analysis. These technologies not only record glucose levels over time but also upload the information to a cloud service or mobile app for thorough analysis. The insulin pump can then administer the correct dosage of insulin to the patient based on the findings of the analysis. Another illustration is the employment of sophisticated nanny cameras to monitor geriatric patients. These smart cameras can detect deviations from routines, such as instances where an elderly person uses the restroom but does not return within a short period. The camera can detect falls and notify caretakers or emergency personnel accordingly.

The utilization of bots or virtual agents for patient communication is another IoT application that may gain popularity in the coming times. Seniors can access a personal virtual assistant to receive medication reminders, answer questions about their health or pain levels, and respond with data collected from their devices, such as glucose levels, fall detection, or oxygen levels. This integration entails combining sensor data collected by various IoT devices and sensors and using voice-enabled speakers.

In addition to wearables and patient-specific interactions, IoT will be integrated into healthcare facilities for inventory management and equipment tracking. The scale of the sensors and developments in wireless technology have resulted in ongoing advancements in this technology, also known as real-time location systems. Hospitals will gain a better understanding of potential equipment shortages and individuals who may encounter the equipment by tracking the movement of equipment and general usage. This is crucial for preventing the spread of infections, as demonstrated by the COVID-19 pandemic, which made hospitals monitor staff members and equipment that had contact with afflicted patients.

5. Conclusions

IoT sensors and devices, with their recent advancements, have established themselves as an essential part of daily activities. They ensure that IoT holds its role in directing users on the right and fast processing track. Within the realm of diverse IoMT sensors and devices, a general ICU scenario has been considered. and most common sensors and devices have been undertaken for this systematic review.

Particularly, in the medical field, IoT can make everyone’s life significantly easier by processing and managing the entire system where the medical devices will be connected along with access to an online database. Moreover, doctors can regularly check updates, and store data, and patients can update their conditions regularly. These updates can be visualized, managed, and monitored using various IoT-based platforms suitable for medical applications, such as KHARE, Kaa, MindSphere, and so on. The doctor can access prescription histories and retrieve records of any patients using these platforms.

Moreover, IoT-connected wearables, contact lenses, blood labs, tracking systems and others are currently changing the outcomes. With the inclusion of 5G technology and AI, these medical IoT devices will become more effective, offering features like interactive communication between patients and doctors, remote surgery, VR-assisted check-ups, and so on. Even though the devices are advancing and becoming more robust, employing IoT technology, especially by equipping sensors for medical devices enables assessment, communication, and data storage and access data from any cloud-based directory. In short, IoT applications in the medical arena have limitless opportunities. But it has a substantial gap as well. Narrowing this gap, could be a game changer event in upcoming years.