Submitted:

01 September 2023

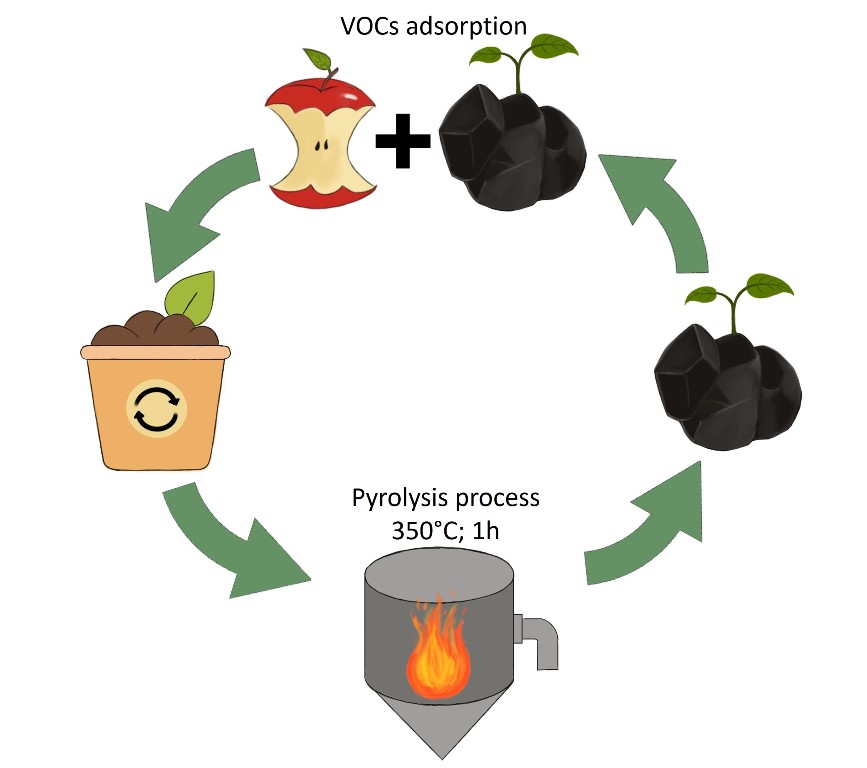

Posted:

04 September 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

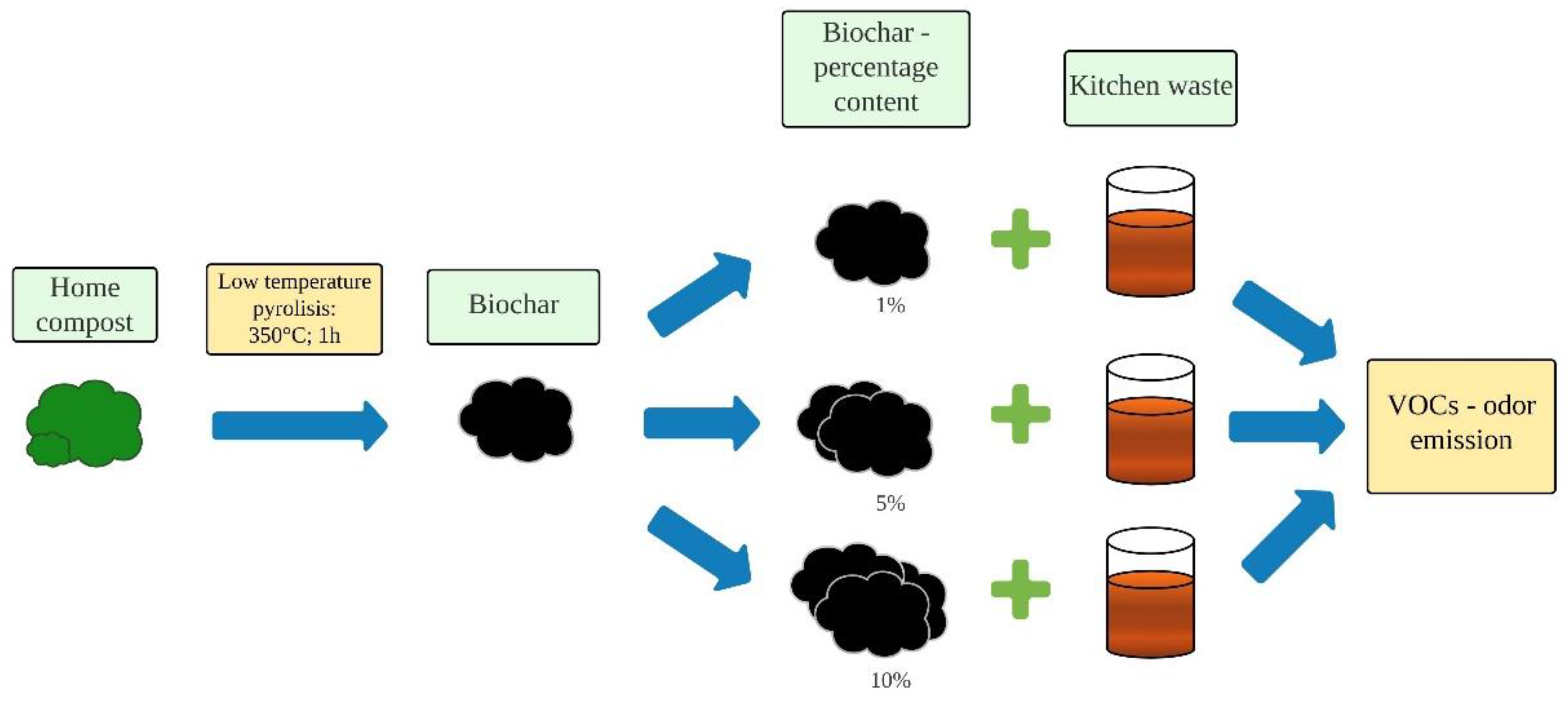

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

- vegetable and fruit waste, 65% by weight,

- pasta, rice and bread waste, 20% by weight,

- meat and dairy waste, 15% by weight.

2.2. Experimental Procedure

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Materials Analysis

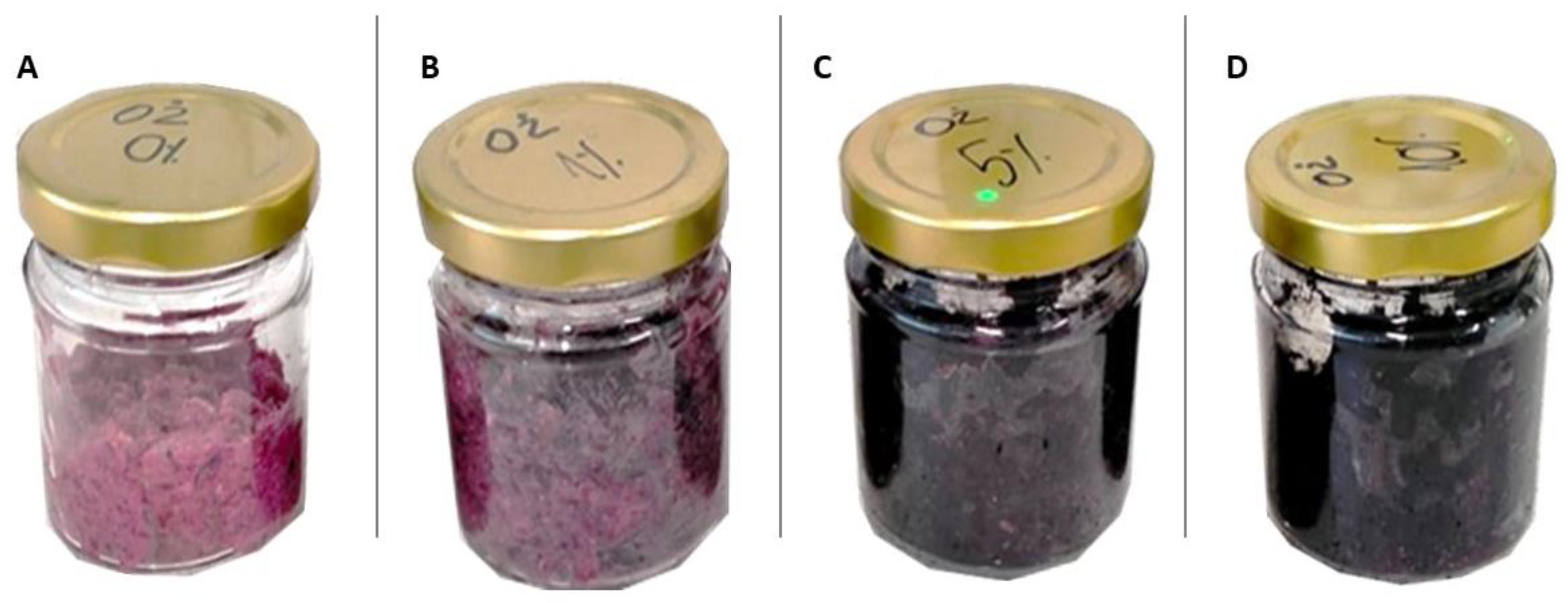

2.3.2. Sample Preparation for VOC Analysis

2.3.3. VOC Analysis - GC-MS, SPME Arrow Extraction

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

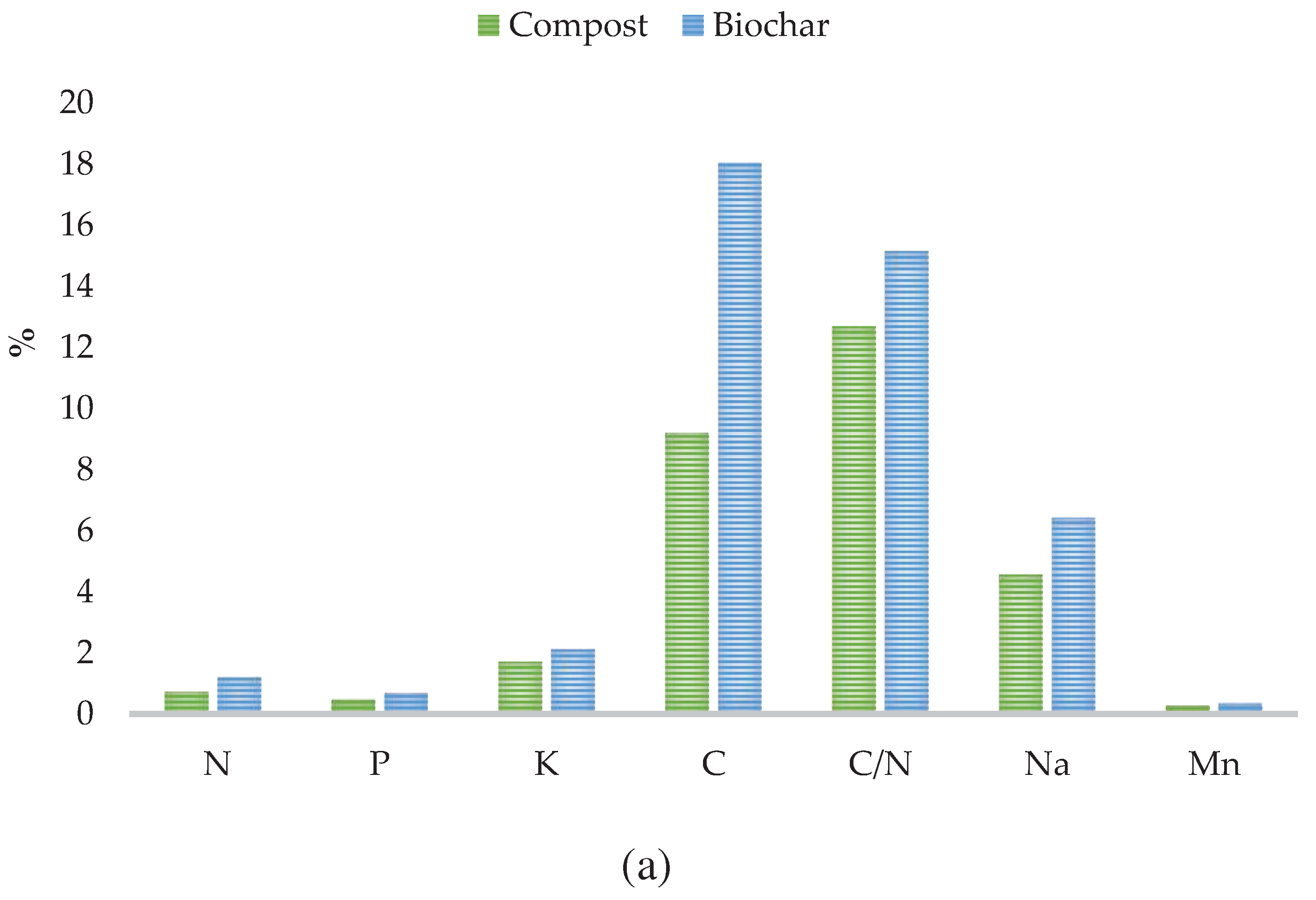

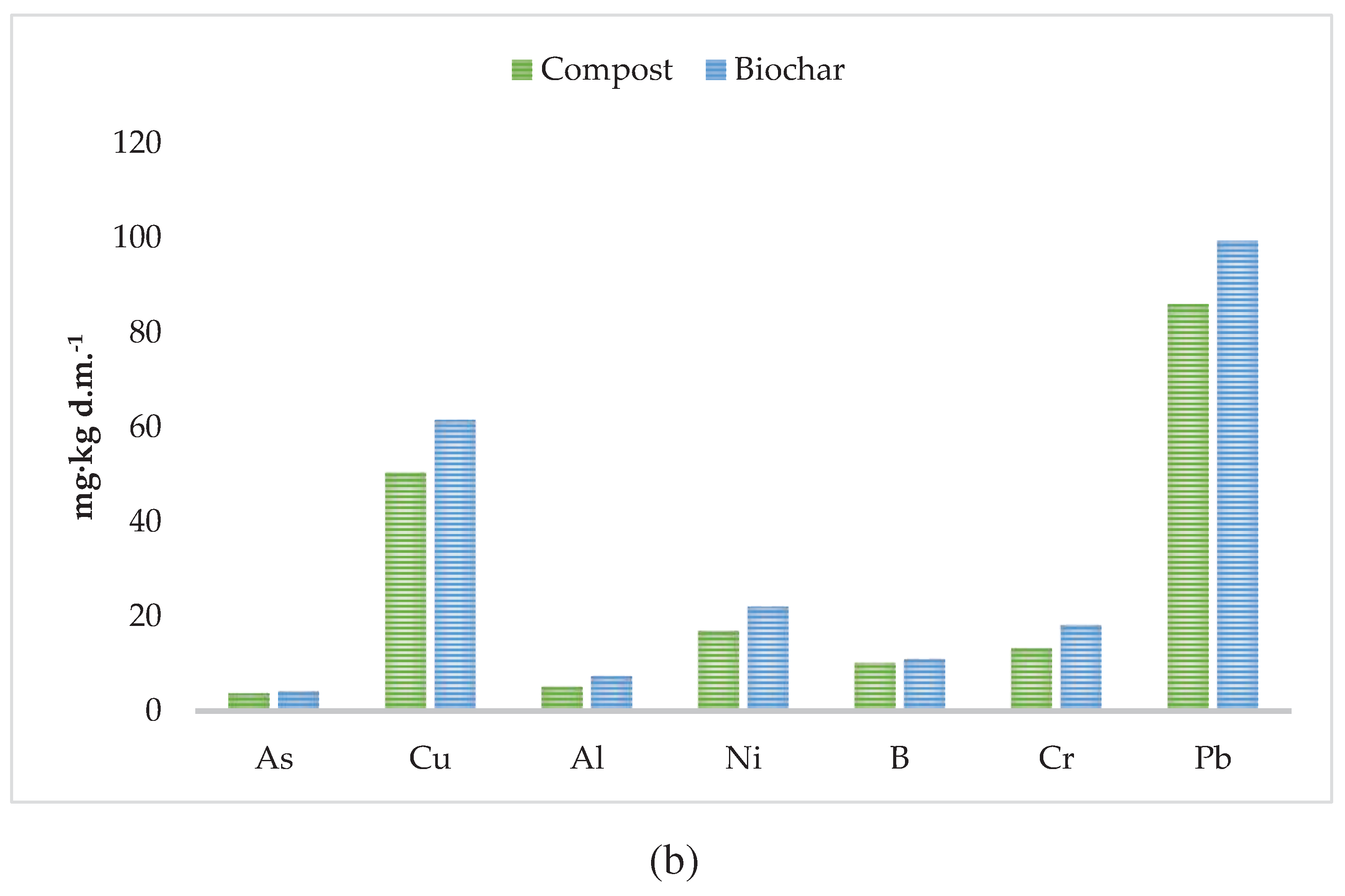

3.1. Properties of Compost, Biochar and Kitchen Waste

| Substrate | CEC, cmol(+)‧kg-1 | N-NH4, mg‧kg-1 d.m. | N-NO3, mg‧kg-1 d.m. | LOI, % d.m. | pH, - | Moisture, % | EC, mS‧cm-1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compost | 143.28 | 125.85 | 1322.03 | 34 | 7.09 | 1.71 | 2.88 |

| Biochar | 123.92 | 55.99 | 16.03 | 19 | 6.92 | 40.20 | n.d. |

| Kitchen waste | Day 1 | 4.92 | 80.05 | 2.05 | |||

| Day 7 | 3.87 | 79.95 | 1.91 | ||||

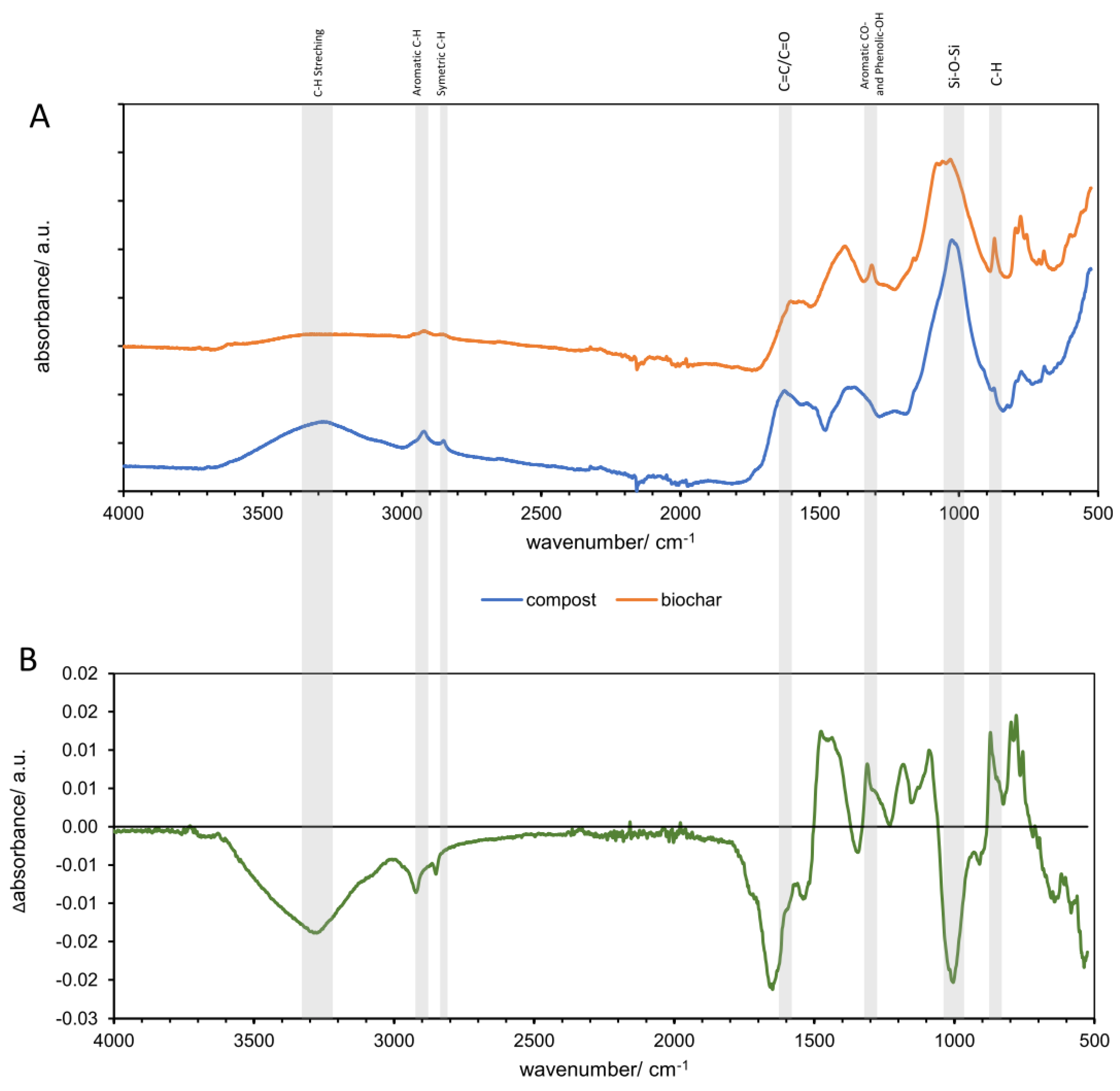

3.1.1. Infrared Spectroscopy Analysis of Compost and Biochar

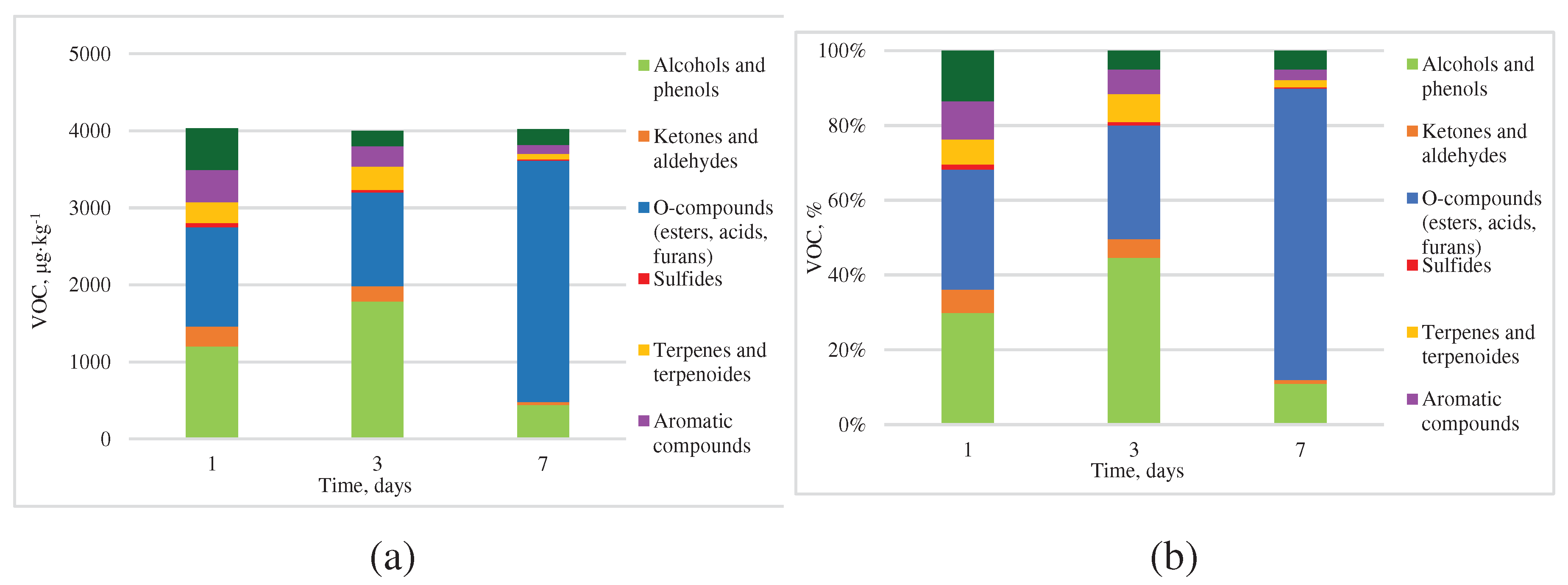

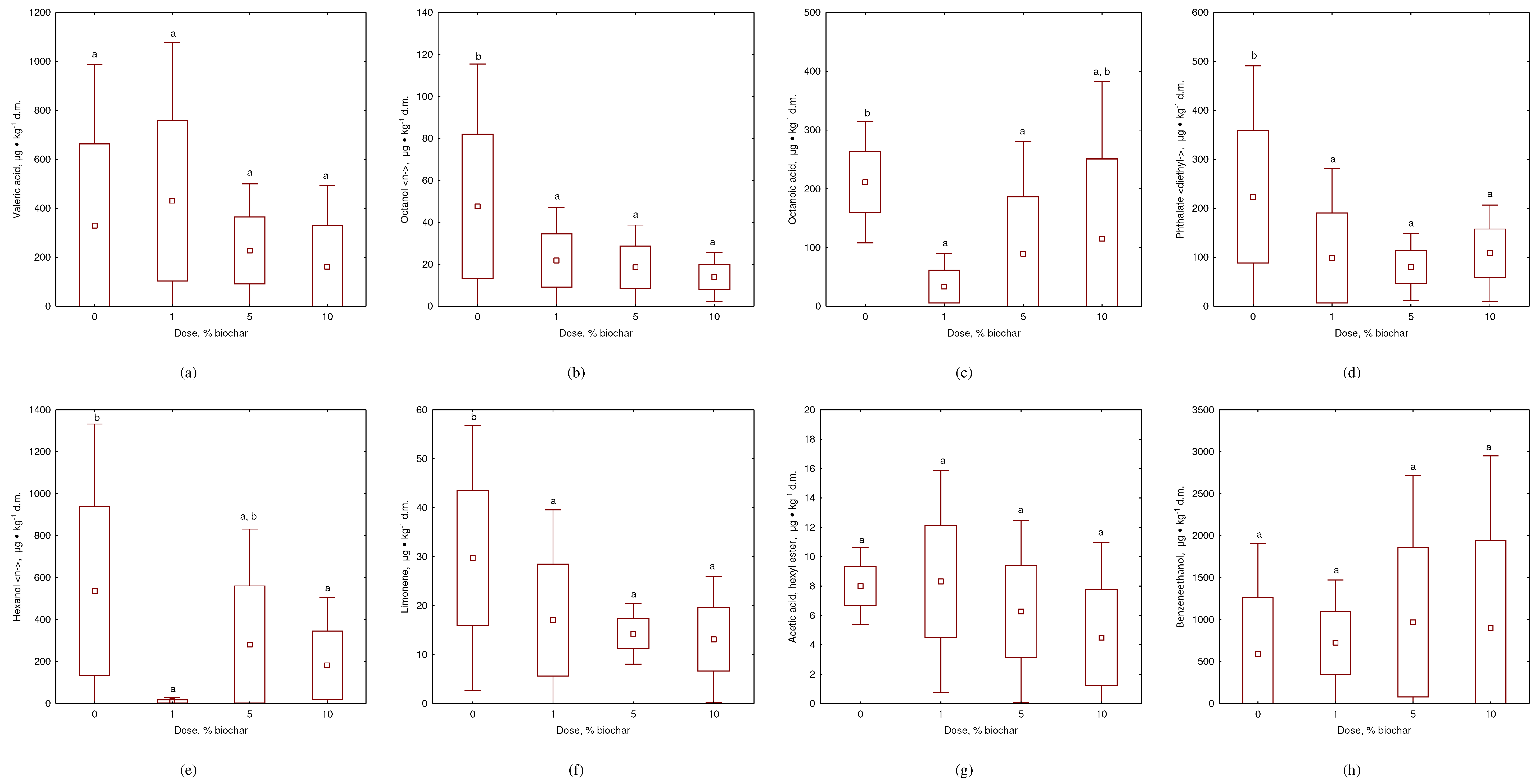

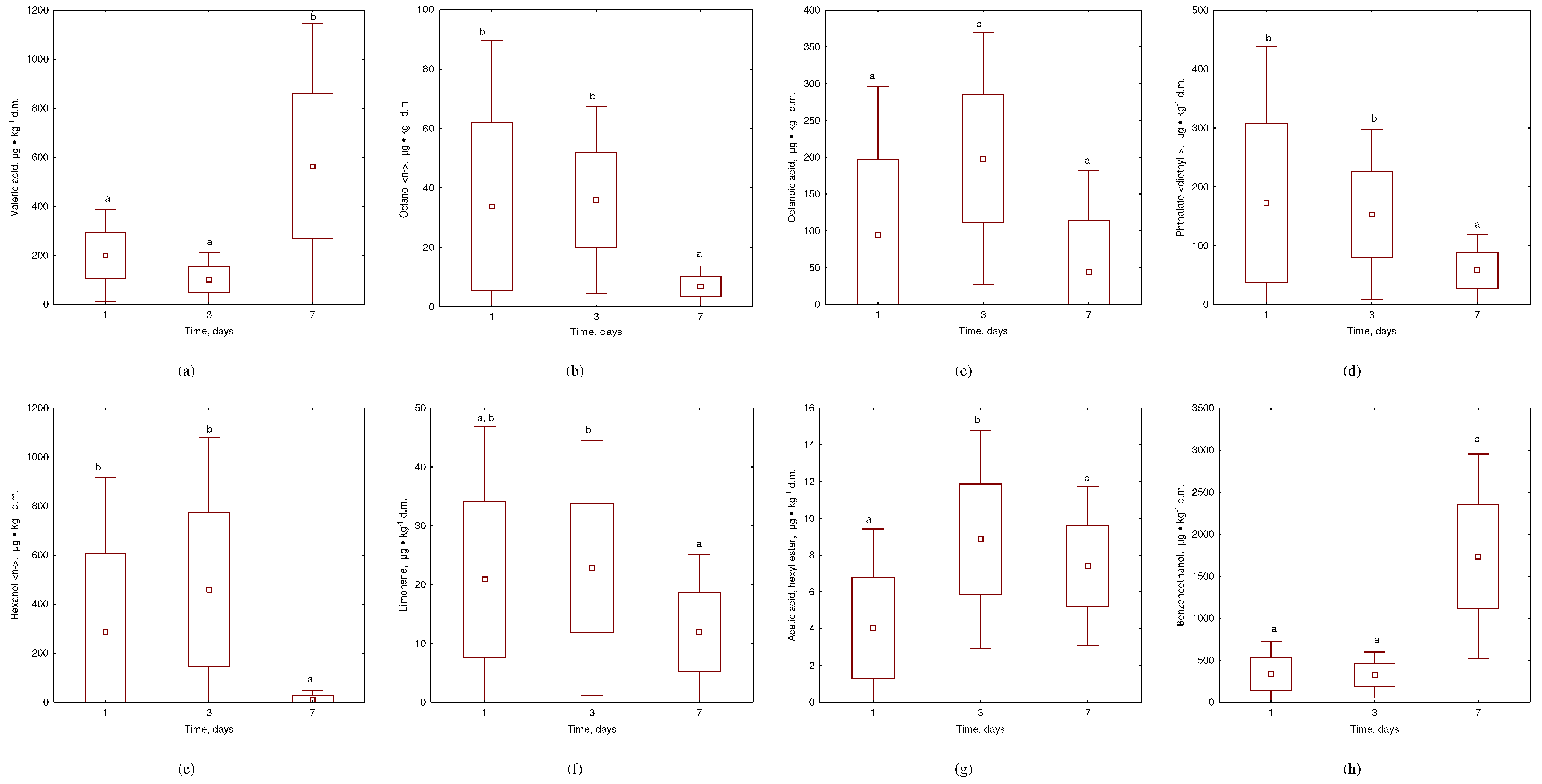

3.2. VOCs Emissions during Kitchen Waste Incubation at 20°C

4. Conclusions

- Addition of Composts' biochar to kitchen waste demonstrated significant VOC removal, with over 70% reduction in VOC emissions when 5-10% biochar was added.

- The most effective reduction was observed for unpleasant odors such as hexa-nol <-n> acetic acid, hexyl ester, and diethyl-phthalate, while no effect was ob-served for pleasant odors such as octanol <n->, limonene, octanoic acid, and benzeneethanol.

- The high mineral fraction content of Composts' biochar suggests that VOC gaseous sorption was controlled more by noncarbonized organic matter con-tent than physical adsorption.

- 25% of detected VOC compounds play a role in plant, microorganism, and human metabolism, what suggests that Composts' biochar has a positive im-pact on overall metabolism and accelerates biodegradation.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| No. | Biochar dose, % | 0 | 1 | 5 | 10 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day of the store | 1 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 3 | 7 | |

| 1 | Butyric acid | 157.2 | 146.9 | 194.9 | |||||||||

| 2 | unknown | 48.3 | 13.9 | 158.7 | 386.4 | 16.5 | 75.1 | 493.6 | 156.8 | 168.9 | 708.7 | 446.7 | 248.7 |

| 3 | Valeric acid | 172.8 | 51.1 | 765.3 | 296.1 | 145.3 | 853.3 | 243.6 | 91.9 | 349.6 | 86.1 | 116.3 | 283.7 |

| 4 | 3-Hexen-1-ol, (3Z)- | 32.1 | 15.1 | 366.8 | 21.9 | 9.1 | 536.4 | 36.8 | 7.0 | 96.7 | 0.0 | 7.2 | 0.0 |

| 5 | 2-Hexen-1-ol, (E)- | 18.3 | 793.9 | 5.7 | |||||||||

| 6 | Hexanol <n-> | 799.7 | 805.9 | 5.3 | 220.4 | 993.1 | 21.2 | 194.0 | 637.7 | 38.8 | 138.4 | 383.7 | 37.2 |

| 7 | unknown acid | 18.0 | 46.5 | 75.5 | 25.3 | 51.3 | 49.6 | 41.7 | 69.7 | 19.4 | |||

| 8 | unknown | 299.9 | 18.5 | 10.0 | |||||||||

| 9 | n-Butyl ethe | 16.5 | 4.1 | 1.9 | |||||||||

| 10 | Methyl allyl disulfide | 7.5 | 6.0 | 0.8 | |||||||||

| 11 | Hexanoic acid, methyl ester | 28.4 | 40.3 | 15.5 | |||||||||

| 12 | Disulfide <methyl-, propyl-> | 3.1 | 3.6 | 0.9 | |||||||||

| 13 | Pinene <alpha-> | 9.2 | 4.1 | 1.9 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 1.1 | 3.9 | 2.4 | 2.9 | 5.9 | 4.5 | 5.5 |

| 14 | 2-Propanol, 1-butoxy- | 4.3 | 2.7 | 0.8 | |||||||||

| 15 | Benzaldehyde | 50.5 | 36.0 | 1.4 | 30.5 | 32.4 | 3.2 | 77.6 | 42.7 | 8.1 | 88.3 | 87.6 | 17.3 |

| 16 | 2-Hepten-1-ol, (2E)- | 25.6 | 21.9 | 14.1 | |||||||||

| 17 | Heptanol <n-> | 38.7 | 27.5 | 23.9 | 7.9 | 28.1 | 4.9 | 6.8 | 17.3 | 10.9 | 4.0 | 10.7 | 7.0 |

| 18 | Hexanoic acid | 310.0 | 342.5 | 337.7 | |||||||||

| 19 | Furan <2-pentyl-> | 31.1 | 44.0 | 18.3 | 16.7 | 77.7 | 109.3 | 9.9 | 89.5 | 41.3 | 9.5 | 62.0 | 28.7 |

| 20 | Hept-5-en-2-ol <6-methyl-> | 11.7 | 0.0 | 3.6 | 17.2 | 6.4 | 0.0 | 8.8 | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 6.0 | 0.0 |

| 21 | 3-Octanol | 65.4 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 8.4 | 7.8 | 7.4 | 10.0 | 0.0 | 12.9 | 0.0 | 2.8 | 10.0 |

| 22 | Octanal <n-> | 41.6 | 33.3 | 11.6 | |||||||||

| 23 | Carene <delta-3-> | 21.2 | 10.9 | 4.0 | 6.4 | 4.8 | 2.1 | 7.7 | 6.8 | 3.3 | 8.9 | 8.4 | 5.2 |

| 24 | Acetic acid, hexyl ester | 7.2 | 8.8 | 8.0 | 4.8 | 13.1 | 7.1 | 2.3 | 8.3 | 8.3 | 5.6 | 5.3 | 6.3 |

| 25 | Limonene | 41.9 | 33.6 | 13.7 | 16.1 | 28.8 | 6.1 | 14.4 | 16.7 | 11.7 | 11.2 | 12.0 | 16.1 |

| 26 | Hexanol <2-ethyl-> | 45.9 | 11.2 | 5.6 | 16.5 | 13.6 | 1.6 | 16.9 | 6.7 | 8.0 | 21.3 | 7.3 | 17.1 |

| 27 | Benzenemethanol | 30.7 | 29.6 | 5.7 | 32.9 | 32.0 | 9.3 | 62.4 | 34.7 | 12.1 | 110.4 | 52.1 | 46.3 |

| 28 | Benzeneacetaldehyde | 34.1 | 22.1 | 5.7 | 126.5 | 81.7 | 4.5 | 28.4 | 32.3 | 2.1 | 19.8 | 16.1 | 3.9 |

| 29 | 2-Octenal, (2E)- | 20.9 | 23.2 | 4.0 | 7.1 | 36.7 | 1.6 | 10.4 | 30.7 | 3.7 | 6.4 | 27.5 | 7.7 |

| 30 | 2-Octen-1-ol, (2E)- | 44.0 | 16.1 | 2.5 | |||||||||

| 31 | Octanol <n-> | 78.8 | 60.5 | 3.6 | 24.0 | 33.7 | 7.7 | 19.5 | 29.5 | 6.9 | 12.8 | 20.1 | 9.1 |

| 32 | Heptanoic acid | 16.1 | 13.7 | 8.3 | 22.8 | 25.5 | 27.5 | 21.3 | 38.4 | 3.0 | 16.5 | 25.3 | 9.6 |

| 33 | Disulfide <allyl-> | 26.3 | 17.3 | 6.8 | 17.7 | 16.0 | 13.2 | ||||||

| 34 | Linalool | 30.5 | 36.5 | 19.6 | 34.1 | 61.7 | 20.8 | ||||||

| 35 | Nonanal <n-> | 22.5 | 28.1 | 5.3 | |||||||||

| 36 | Disulfide <dipropyl-> | 17.7 | 10.1 | 5.3 | 11.7 | 10.7 | 4.3 | 18.8 | 15.5 | 10.1 | 17.3 | 11.6 | 11.3 |

| 37 | Benzeneethanol | 109.3 | 190.0 | 1482.9 | 565.3 | 422.4 | 1189.9 | 407.6 | 404.0 | 2093.3 | 251.5 | 282.3 | 2170.7 |

| 38 | unknown | 70.7 | 40.9 | 2.0 | |||||||||

| 39 | Octanoic acid, methyl ester | 13.3 | 30.1 | 11.5 | 14.4 | 28.4 | 12.0 | 14.7 | 27.3 | 10.3 | 11.5 | 21.6 | 7.7 |

| 40 | Camphor | 6.5 | 1.9 | 1.0 | |||||||||

| 41 | Octanoic acid | 262.4 | 211.7 | 160.1 | |||||||||

| 42 | Decanal <n-> | 19.2 | 21.3 | 0.8 | |||||||||

| 43 | Benzothiazole | 10.1 | 5.7 | 2.0 | |||||||||

| 44 | Nonanoic acid | 23.7 | 16.1 | 5.9 | 7.7 | 15.3 | 4.7 | 8.4 | 14.5 | 0.8 | 7.2 | 10.7 | 1.2 |

| 45 | Undecan-2-one | 66.3 | 38.3 | 13.1 | 22.4 | 25.9 | 3.2 | 17.9 | 22.9 | 10.7 | 24.4 | 15.9 | 18.0 |

| 46 | Decanoic acid, methyl ester | 19.6 | 21.2 | 11.1 | 17.3 | 21.1 | 13.6 | 23.2 | 198.5 | 4.0 | 25.1 | 30.5 | 11.2 |

| 47 | unknown | 34.7 | 16.4 | 13.0 | |||||||||

| 48 | Triacetin | 45.1 | 35.7 | 2.4 | |||||||||

| 49 | n-Decanoic acid | 36.8 | 36.4 | 48.5 | |||||||||

| 50 | Butanoic acid, octyl ester | 49.9 | 27.5 | 7.3 | |||||||||

| 51 | Copaene <alpha-> | 67.9 | 100.7 | 16.4 | 19.2 | 61.6 | 4.1 | 23.1 | 70.4 | 7.6 | 20.4 | 62.4 | 13.9 |

| 52 | Longipinene<beta-> | 79.1 | 99.5 | 14.8 | 17.2 | 67.5 | 5.6 | 21.1 | 68.0 | 10.3 | 17.2 | 65.3 | 16.3 |

| 53 | IS | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 54 | gamma.-Elemene | 54.3 | 85.9 | 13.2 | 11.3 | 40.9 | 3.5 | 17.2 | 43.7 | 6.1 | 15.7 | 43.6 | 13.9 |

| 55 | Himachalene <alpha-> | 17.5 | 22.0 | 5.2 | 2.4 | 12.0 | 1.2 | 2.3 | 9.6 | 2.0 | 4.3 | 10.0 | 3.9 |

| 56 | trans-Geranylacetone | 22.8 | 11.2 | 1.3 | 6.4 | 5.6 | 0.0 | 4.8 | 6.8 | 1.4 | 5.1 | 0.0 | 3.1 |

| 57 | Dodecanol | 20.4 | 0.0 | 0.8 | |||||||||

| 58 | Phthalate <diethyl-> | 376.8 | 207.3 | 87.7 | 69.3 | 201.9 | 25.1 | 108.9 | 92.0 | 39.5 | 134.0 | 111.1 | 80.4 |

| 59 | Lactate <ethyl-> | 933.3 | 199.6 | 192.8 | 53.1 | 58.3 | 33.6 | 1248.8 | 121.6 | 343.7 | |||

| 60 | Benzene <ethyl-> | 30.4 | 26.7 | 0.1 | 1042.8 | 190.4 | 281.9 | 52.8 | 88.1 | 34.4 | |||

| 61 | Isoamyl acetate | 35.1 | 40.7 | 82.4 | 36.9 | 30.4 | 230.0 | 46.7 | 61.9 | 106.6 | |||

| 62 | o-Xylene | 14.8 | 11.7 | 3.9 | 22.8 | 25.2 | 15.5 | 28.3 | 38.1 | 16.9 | |||

| 63 | Heptan-2-ol | 33.2 | 17.2 | 7.5 | 46.3 | 18.7 | 35.5 | 27.5 | 40.5 | 40.0 | |||

| 64 | Hexanoate <methyl-> | 21.9 | 54.8 | 18.9 | 22.7 | 41.1 | 12.9 | 19.9 | 38.7 | 14.5 | |||

| 65 | 1-Octen-3-ol | 168.0 | 164.8 | 23.7 | 153.3 | 113.6 | 60.0 | 57.5 | 131.1 | 64.8 | |||

| 66 | Caproic acid | 144.4 | 299.5 | 533.7 | 145.5 | 401.5 | 132.9 | 170.8 | 316.4 | 46.1 | |||

| 67 | Thiophen-3-one <dihydro-, 2-methyl-> | 18.0 | 2.6 | 268.2 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | |||

| 68 | Pseudocumene | 3.3 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 8.9 | 7.3 | 5.5 | 12.5 | 11.7 | 8.5 | |||

| 69 | Cymene <para-> | 3.6 | 5.9 | 2.6 | 4.7 | 6.4 | 3.2 | 4.8 | 6.5 | 5.4 | |||

| 70 | Cresol <ortho-> | 9.3 | 6.0 | 6.0 | 12.1 | 17.6 | 9.2 | 17.0 | 16.0 | 12.0 | |||

| 71 | Cresol<meta-> | 9.3 | 11.1 | 25.2 | 14.9 | 14.3 | 5.7 | 15.3 | 9.9 | 8.5 | |||

| 72 | Disulfide <allyl-> | 17.3 | 14.7 | 0.0 | 18.4 | 14.9 | 14.8 | ||||||

| 73 | Caprylonitrile | 0.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 3.3 | 0.0 | 4.9 | |||

| 74 | Guaiacol | 6.0 | 2.2 | 1.7 | 11.5 | 8.4 | 2.9 | 10.9 | 10.8 | 8.8 | |||

| 75 | 2-Nonanone | 4.9 | 3.0 | 1.2 | 6.8 | 0.0 | 4.0 | 27.6 | 4.0 | 10.3 | |||

| 76 | Caprylic acid | 180.3 | 220.7 | 202.0 | 142.5 | 228.3 | 46.4 | 74.8 | 174.0 | 4.1 | |||

| 77 | Benzeneacetic acid, methyl ester | 7.5 | 7.8 | 4.8 | 4.1 | 10.8 | 11.2 | 5.4 | 0.0 | ||||

| 78 | Naphthalene | 32.7 | 23.1 | 8.2 | 65.1 | 54.1 | 33.5 | 87.6 | 76.4 | 50.0 | |||

| 79 | Octanoic acid, ethyl ester | 22.8 | 69.7 | 12.4 | 41.1 | 217.7 | 13.2 | 53.1 | 292.5 | 0.0 | |||

| 80 | Tridecane <n-> | 6.1 | 5.6 | 2.3 | 14.4 | 16.0 | 9.2 | ||||||

| 81 | Napthalene,<1-Methyl -> Naphthalene, 1-methyl- | 12.5 | 9.5 | 3.2 | 29.5 | 25.6 | 12.1 | 44.5 | 35.6 | 23.9 | |||

| 82 | 2-Nonanol, 2-methylpropionate | 11.3 | 6.3 | 2.9 | 10.9 | 4.3 | 4.9 | 14.8 | 7.9 | 5.3 | |||

| 83 | Capric acid | 29.9 | 42.4 | 46.4 | 28.5 | 51.5 | 19.6 | 20.8 | 43.9 | 18.3 | |||

| 84 | Decanoic acid, ethyl ester | 11.5 | 49.7 | 6.9 | 23.1 | 27.1 | 10.1 | 52.3 | 303.5 | 7.2 | |||

| 85 | Pentadecane | 4.1 | 0.0 | 1.3 | 5.5 | 3.6 | 4.1 | 8.0 | 8.0 | 6.8 | |||

| 86 | Farnesene <(E,E)-, alpha-> | 138.1 | 0.0 | 1.4 | 28.7 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 4.9 | 40.8 | 7.4 | |||

| 87 | Tetradecane <n-> | 5.6 | 4.8 | 2.1 | 9.3 | 10.1 | 6.5 | 16.0 | 16.1 | 11.1 | |||

References

- Zheng, G.; Liu, J.; Shao, Z.; Chen, T. Emission Characteristics and Health Risk Assessment of VOCs from a Food Waste Anaerobic Digestion Plant: A Case Study of Suzhou, China. Environmental Pollution 2020, 257, 113546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Tan, L.; Wang, Q.; Li, Q.; Wei, X.; Liu, F.; Li, Y.; Zheng, X. Exploration of Bacterial Communities in Products after Composting Rural Wastes with Different Components: Core Microbiome and Potential Pathogenicity. Environ Technol Innov 2022, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, F.; Li, P.; Li, L.; Qiu, Z.; Han, Y.; Yang, K. Dispersion, Olfactory Effect, and Health Risks of VOCs and Odors in a Rural Domestic Waste Transfer Station. Environ Res 2022, 209, 112879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chung, W.J.; Chang, S.W.; Chaudhary, D.K.; Shin, J. Du; Kim, H.; Karmegam, N.; Govarthanan, M.; Chandrasekaran, M.; Ravindran, B. Effect of Biochar Amendment on Compost Quality, Gaseous Emissions and Pathogen Reduction during in-Vessel Composting of Chicken Manure. Chemosphere 2021, 283, 131129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, K.; Wang, C.; Xue, S.; Li, W.; Liu, J.; Li, L. The Identification, Health Risks and Olfactory Effects Assessment of VOCs Released from the Wastewater Storage Tank in a Pesticide Plant. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2019, 184, 109665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Gao, X.; Qin, J.; Guo, Q.; Zhou, H.; Jin, W. Microporous Polyimide VOC-Rejective Membrane for the Separation of Nitrogen/VOC Mixture. J Hazard Mater 2021, 402, 123817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, S.; Cui, L.; Bi, F.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, N.; Wang, Y.; Liu, F.; He, C.; Zhang, X. Recent Advancement and Future Challenges of Photothermal Catalysis for VOCs Elimination: From Catalyst Design to Applications. Green Energy & Environment 2023, 8, 654–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelodun, A.A. Influence of Operation Conditions on the Performance of Non-Thermal Plasma Technology for VOC Pollution Control. Journal of Industrial and Engineering Chemistry 2020, 92, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vikrant, K.; Kim, K.H.; Peng, W.; Ge, S.; Sik Ok, Y. Adsorption Performance of Standard Biochar Materials against Volatile Organic Compounds in Air: A Case Study Using Benzene and Methyl Ethyl Ketone. Chemical Engineering Journal 2020, 387, 123943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Chen, C.; Yang, R.; Yu, Y.; Albilali, R.; He, C. Remarkable Promotion Effect of Lauric Acid on Mn-MIL-100 for Non-Thermal Plasma-Catalytic Decomposition of Toluene. Appl Surf Sci 2020, 503, 144290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barquilha, C.E.R.; Braga, M.C.B. Adsorption of Organic and Inorganic Pollutants onto Biochars: Challenges, Operating Conditions, and Mechanisms. Bioresour Technol Rep 2021, 15, 100728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, B.; Zheng, Y.; Hu, X.; Creamer, A.E.; Annable, M.D.; Li, Y. Biochar for Volatile Organic Compound (VOC) Removal: Sorption Performance and Governing Mechanisms. Bioresour Technol 2017, 245, 606–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, E.; Zheng, G.; Shao, Z.; Yang, J.; Chen, T. Emission Characteristics and Health Risk Assessment of Volatile Organic Compounds Produced during Municipal Solid Waste Composting. Waste Management 2018, 79, 188–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duan, Y.; Awasthi, S.K.; Liu, T.; Zhang, Z.; Awasthi, M.K. Response of Bamboo Biochar Amendment on Volatile Fatty Acids Accumulation Reduction and Humification during Chicken Manure Composting. Bioresour Technol 2019, 291, 121845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Monedero, M.A.; Sánchez-García, M.; Alburquerque, J.A.; Cayuela, M.L. Biochar Reduces Volatile Organic Compounds Generated during Chicken Manure Composting. Bioresour Technol 2019, 288, 121584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, O.; Lee, S.R.; Cho, S.; Ro, K.S.; Spiehs, M.; Woodbury, B.; Silva, P.J.; Han, D.W.; Choi, H.; Kim, K.Y.; et al. Efficacy of Different Biochars in Removing Odorous Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs) Emitted from Swine Manure. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2018, 6, 14239–14247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awasthi, M.K.; Awasthi, S.K.; Wang, Q.; Wang, Z.; Lahori, A.H.; Ren, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, M.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, Z. Influence of Biochar on Volatile Fatty Acids Accumulation and Microbial Community Succession during Biosolids Composting. Bioresour Technol 2018, 251, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czekała, W.; Malińska, K.; Cáceres, R.; Janczak, D.; Dach, J.; Lewicki, A. Co-Composting of Poultry Manure Mixtures Amended with Biochar – The Effect of Biochar on Temperature and C-CO2 Emission. Bioresour Technol 2016, 200, 921–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Miao, X.; Xiang, W.; Zhang, J.; Cao, C.; Wang, H.; Hu, X.; Gao, B. Ball Milling Biochar with Ammonia Hydroxide or Hydrogen Peroxide Enhances Its Adsorption of Phenyl Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs). J Hazard Mater 2021, 403, 123540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antunes, E.; Vuppaladadiyam, A.K.; Kumar, R.; Vuppaladadiyam, V.S.S.; Sarmah, A.; Anwarul Islam, M.; Dada, T. A Circular Economy Approach for Phosphorus Removal Using Algae Biochar. Cleaner and Circular Bioeconomy 2022, 1, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolognesi, S.; Bernardi, G.; Callegari, A.; Dondi, D.; Capodaglio, A.G. Biochar Production from Sewage Sludge and Microalgae Mixtures: Properties, Sustainability and Possible Role in Circular Economy. Biomass Convers Biorefin 2021, 11, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Jung, J.; Chen, D.; Leong, K.; Song, S.; Li, F.; Mohan, B.C.; Yao, Z.; Prabhakar, A.K.; Lin, X.H.; et al. Biochar Industry to Circular Economy. Science of The Total Environment 2021, 757, 143820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danish, A.; Ali Mosaberpanah, M.; Usama Salim, M.; Ahmad, N.; Ahmad, F.; Ahmad, A. Reusing Biochar as a Filler or Cement Replacement Material in Cementitious Composites: A Review. Constr Build Mater 2021, 300, 124295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Luo, D.; Zhang, X.; Huang, R.; Cao, Y.; Liu, G.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H. Biochar-Based Slow-Release of Fertilizers for Sustainable Agriculture: A Mini Review. Environmental Science and Ecotechnology 2022, 10, 100167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lateef, A.; Nazir, R.; Jamil, N.; Alam, S.; Shah, R.; Khan, M.N.; Saleem, M.; Rehman, S. ur Synthesis and Characterization of Environmental Friendly Corncob Biochar Based Nano-Composite – A Potential Slow Release Nano-Fertilizer for Sustainable Agriculture. Environ Nanotechnol Monit Manag 2019, 11, 100212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, M.; Liu, L.; Ling, Q.; Cai, Y.; Yu, S.; Wang, S.; Fu, D.; Hu, B.; Wang, X. Biochar for the Removal of Contaminants from Soil and Water: A Review. Biochar 2022, 4, 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Dahal, R.K.; Acharya, B.; Farooque, A. Biochar: A Sustainable Solution for Solid Waste Management in Agro-Processing Industries. https://doi.org/10.1080/17597269.2018.1468978, 2018; 12, 237–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PHARES, C.A.; AKABA, S. Co-Application of Compost or Inorganic NPK Fertilizer with Biochar Influences Soil Quality, Grain Yield and Net Income of Rice. J Integr Agric 2022, 21, 3600–3610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konaka, T.; Tadano, S.; Takahashi, T.; Suharsono, S.; Mazereku, C.; Tsujimoto, H.; Masunaga, T.; Yamamoto, S.; Akashi, K. A Diverse Range of Physicochemically-Distinct Biochars Made from a Combination of Different Feedstock Tissues and Pyrolysis Temperatures from a Biodiesel Plant Jatropha Curcas: A Comparative Study. Ind Crops Prod 2021, 159, 113060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medyńska-Juraszek, A.; Bednik, M.; Chohura, P. Assessing the Influence of Compost and Biochar Amendments on the Mobility and Uptake of Heavy Metals by Green Leafy Vegetables. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addai, P.; Mensah, A.K.; Sekyi-Annan, E.; Adjei, E.O. Biochar, Compost and/or NPK Fertilizer Affect the Uptake of Potentially Toxic Elements and Promote the Yield of Lettuce Grown in an Abandoned Gold Mine Tailing. Journal of Trace Elements and Minerals 2023, 4, 100066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Białowiec, A.; Micuda, M.; Szumny, A.; Łyczko, J.; Koziel, J.A. The Proof-of-the-Concept of Application of Pelletization for Mitigation of Volatile Organic Compounds Emissions from Carbonized Refuse-Derived Fuel. Materials 2019, Vol. 12, Page 1692 2019, 12, 1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mujtaba, G.; Hayat, R.; Hussain, Q.; Ahmed, M. Physio-Chemical Characterization of Biochar, Compost and Co-Composted Biochar Derived from Green Waste. Sustainability 2021, Vol. 13, Page 4628 2021, 13, 4628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, A.C.; Rocha, P.; Antelo, J.; Valderrama, P.; López, R.; Geraldo, D.; Proença, M.F.; Pinheiro, J.P.; Fiol, S.; Bento, F. Comparison of a Variety of Physico-Chemical Techniques in the Chronological Characterization of a Compost from Municipal Wastes. Process Safety and Environmental Protection 2022, 164, 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Rueda, M.; Comino, F.; Aranda, V.; José Ayora-Cañada, M.; Domínguez-Vidal, A. Understanding the Compositional Changes of Organic Matter in Torrefied Olive Mill Pomace Compost Using Infrared Spectroscopy and Chemometrics. Spectrochim Acta A Mol Biomol Spectrosc 2023, 293, 122450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maulini-Duran, C.; Puyuelo, B.; Artola, A.; Font, X.; Sánchez, A.; Gea, T. VOC Emissions from the Composting of the Organic Fraction of Municipal Solid Waste Using Standard and Advanced Aeration Strategies. Journal of Chemical Technology & Biotechnology 2014, 89, 579–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yue, D.; Liu, J.; Lu, P.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J.; Nie, Y. Release of Non-Methane Organic Compounds during Simulated Landfilling of Aerobically Pretreated Municipal Solid Waste. J Environ Manage 2012, 101, 54–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-García, M.; Alburquerque, J.A.; Sánchez-Monedero, M.A.; Roig, A.; Cayuela, M.L. Biochar Accelerates Organic Matter Degradation and Enhances N Mineralisation during Composting of Poultry Manure without a Relevant Impact on Gas Emissions. Bioresour Technol 2015, 192, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierucci, P.; Porazzi, E.; Martinez, M.P.; Adani, F.; Carati, C.; Rubino, F.M.; Colombi, A.; Calcaterra, E.; Benfenati, E. Volatile Organic Compounds Produced during the Aerobic Biological Processing of Municipal Solid Waste in a Pilot Plant. Chemosphere 2005, 59, 423–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statheropoulos, M.; Agapiou, A.; Pallis, G. A Study of Volatile Organic Compounds Evolved in Urban Waste Disposal Bins. Atmos Environ 2005, 39, 4639–4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaglia, B.; Orzi, V.; Artola, A.; Font, X.; Davoli, E.; Sanchez, A.; Adani, F. Odours and Volatile Organic Compounds Emitted from Municipal Solid Waste at Different Stage of Decomposition and Relationship with Biological Stability. Bioresour Technol 2011, 102, 4638–4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdeniz, N.; Koziel, J.A.; Ahn, H.K.; Glanville, T.D.; Crawford, B.P.; Raman, D.R. Laboratory Scale Evaluation of Volatile Organic Compound Emissions as Indication of Swine Carcass Degradation inside Biosecure Composting Units. Bioresour Technol 2010, 101, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Świechowski, K.; Matyjewicz, B.; Telega, P.; Białowiec, A. The Influence of Low-Temperature Food Waste Biochars on Anaerobic Digestion of Food Waste. Materials 2022, Vol. 15, Page 945 2022, 15, 945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turan, N.G.; Akdemir, A.; Ergun, O.N. Emission of Volatile Organic Compounds during Composting of Poultry Litter. Water Air Soil Pollut 2007, 184, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Lan, Y.; Xu, E.G.; Meng, J.; Chen, W. Biochar as a Novel Niche for Culturing Microbial Communities in Composting. Waste Management 2016, 54, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maulini-Duran, C.; Artola, A.; Font, X.; Sánchez, A. Gaseous Emissions in Municipal Wastes Composting: Effect of the Bulking Agent. Bioresour Technol 2014, 172, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staley, B.F.; Xu, F.; Cowie, S.J.; Barlaz, M.A.; Hater, G.R. Release of Trace Organic Compounds during the Decomposition of Municipal Solid Waste Components. Environ Sci Technol 2006, 40, 5984–5991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaglia, B.; Orzi, V.; Artola, A.; Font, X.; Davoli, E.; Sanchez, A.; Adani, F. Odours and Volatile Organic Compounds Emitted from Municipal Solid Waste at Different Stage of Decomposition and Relationship with Biological Stability. Bioresour Technol 2011, 102, 4638–4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorado, A.D.; Husni, S.; Pascual, G.; Puigdellivol, C.; Gabriel, D. Inventory and Treatment of Compost Maturation Emissions in a Municipal Solid Waste Treatment Facility. Waste Management 2014, 34, 344–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Xue, F.; Sun, Q.; Yue, R.; Lin, D. Adsorption of Volatile Organic Compounds by Metal-Organic Frameworks MOF-177. J Environ Chem Eng 2013, 1, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agapiou, A.; Vamvakari, J.P.; Andrianopoulos, A.; Pappa, A. Volatile Emissions during Storing of Green Food Waste under Different Aeration Conditions. Environmental Science and Pollution Research 2016, 23, 8890–8901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Gao, B.; Creamer, A.E.; Cao, C.; Li, Y. Adsorption of VOCs onto Engineered Carbon Materials: A Review. J Hazard Mater 2017, 338, 102–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).