1. Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the third most prevalent gynecologic cancer, following uterine and cervical cancers [

1]. It develops in the cells of the ovaries or other cells of the fallopian tube and peritoneum. Ovarian cancers are classified as epithelial or non-epithelial, with epithelial being more common. Within this classification, numerous histological ovarian cancer subtypes differ in pathophysiology and clinical characteristics [

2]. Notably, ovarian cancer is recognised to have the worst mortality rate and the poorest prognosis compared to other female cancers. Despite being less common than breast cancer, ovarian cancer is fatal three times as often, with estimates that by the year 2040, its mortality rate will significantly increase [

1]. This increase is attributed to the asymptomatic development of tumours, the delayed manifestation of symptoms, and inadequate screening programmes that lead to its diagnosis only in the late stages of the disease [

1,

2]. Despite modern advances in cancer diagnosis technology, detection of invasive ovarian cancer is quite low and challenging, using a combination approach of transvaginal ultrasound and serum cancer antigen-125 (CA-125) test. Moreover, current treatment strategies for ovarian cancer are complicated and have led to only modest improvement in clinical outcomes, particularly in patients with advanced stages of the disease [

3]. Studies in pathophysiology, progression, prognosis, and ovarian cancer therapy have been conducted, with particular interest in the implication of metabolic oxidase enzymes in ovarian cancer.

The cytochrome P450 (CYP) superfamily of enzymes comprises 57 human isotypes belonging to the group of self-oxidising monooxygenases. They are categorised into different families where the CYP1, CYP2, and CYP3 enzyme families are mainly involved in the metabolism of drugs, with the CYP4 family playing a minor role [

4]. These particular families are responsible for detoxifying and inactivating various therapeutic drugs, and most importantly the activation of prodrugs into cytotoxic metabolites. The CYP4 to CYP51 enzyme families are mainly involved in the metabolism of endogenous molecules like vitamins, fatty acids, and steroid hormones [

5]. On the other hand, CYPs can transform chemical compounds such as nitrosamines into reactive metabolites, triggering organ damage and/or tumorigenesis. Moreover, CYP enzymes are susceptible to inhibition and/or induction by a variety of chemicals, which may affect the drug therapeutic responses [

4,

5]. Importantly, the inter-individual variations between CYP isoforms in gene expression and/or their enzymatic activity are mainly due to differences in genetic alleles or polymorphisms. These variations mainly underlie the susceptibility to many diseases like cancer and differences in drug pharmacokinetic profiles [

5,

6]. Although the majority of CYPs are primarily detected in the liver, a few CYP isoforms of certain families are found in extrahepatic tissues. The expression of these extrahepatic enzymes is identified as dysregulated in many organs, possibly contributing to tumorigenesis [

7]. Notably, CYP1B1, CYP2W1, CYP2J2, and more recently CYP4Z1 have been determined to have cancer-specific expression [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Capitalising on CYP catalytic activity, these cancer-specific CYP enzymes offer novel opportunities for developing selective targeted therapies for cancers expressing these CYP enzymes.

The role of CYPs in the tumorigenesis process is of great interest as the expression of certain CYP isoforms was determined to be altered and possibly associated with the development of ovarian cancer. To the best of our knowledge, no single review article has documented the intratumoural expression of CYPs and their implications in ovarian cancer. Therefore, the current review focuses on the updated findings of individual CYP expression in ovarian cancer, together with the effects of their gene polymorphisms on the metabolism of chemotherapeutic agents and patient prognosis.

2. CYPS in Ovarian Cancers

2.1. CYP1A1

The induction of CYP1A1 expression is transcriptionally regulated by activation of cytosolic aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) upon its binding to different ligands. Limited studies have investigated the CYP1A1 mRNA and protein expression in ovarian cancer cell lines and clinical specimens. Significant levels of CYP1A1 mRNA and protein were detected in ovarian cancer cell lines A2780 and SKOV-3 relative to high expression in breast cancer cell lines [

15]. Similar results were obtained with four other ovarian cancer cell lines demonstrating significant overexpression of CYP1A1 mRNA and protein compared to normal ovary cell lines [

16].

In clinical specimens and according to The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), data from 373 patient samples of ovarian cancer associated with CYP1A1 revealed that the mean mRNA expression of CYP1A1 was 0.1 FPKM with a median expression of 0.04 FPKM [

17]. Moreover, CYP1A1 protein was moderately expressed in all cases examined (12 patient samples of ovarian cancer), where the expression was confined to the cytoplasm of cells. Based on the aforementioned data, CYP1A1 was not recognised as a prognostic biomarker for ovarian cancer [

18]. Similarly, moderate-to-high strong cytoplasmic expression of CYP1A1 was identified in all patient cases of ovarian cancer compared with ovarian benign epithelia and healthy normal tissues [

16]. In contrast, low expression of CYP1A1 was only detected in 20% of ovarian cancer patient samples and comparable to expression in normal ovary samples [

19]. These contradictory results may be due to the use of different types of antibodies mistaking CYP1A1 for a novel CYP1A1-like enzyme variant called CYP1A1v. This enzymatically active variant was highly expressed in ovarian cancer cell lines and predominantly localised to the cytoplasm and nucleolus [

16].

2.2. CYP 1B1

CYP1B1 is an extrahepatic enzyme belonging to the CYP1 family and shares about 40% homology with other members CYP1A1 and CYP1A2. Similar to CYP1A enzymes, induction of CYP1B1 expression is mainly regulated via the activation of AhR receptors by different ligands like dioxins and polycyclic hydrocarbons [

4]. In ovarian cancer cell lines, high expression of CYP1B1 mRNA and protein was detected in A2780, SKOV-3, OVCA 420, OVCA 429, OVCA 432, and OVCA 433 [

15,

16]. Based on data from The Human Protein Atlas, among 180 samples of normal ovaries, the average CYP1B1 mRNA expression was 5.6 nTPM with a median expression of 2.6 nTPM, while CYP1B1 protein expression was low [

18]. These results are consistent with previous studies reporting the absence or low expression of CYP1B1 in normal ovary tissues [

19,

20]. Importantly, among 373 patient samples of ovarian cancers, TCGA showed that the average CYP1B1 mRNA expression was 4.6 FPKM with a median expression of 2.86 FPKM, while moderate-to-high CYP1B1 protein expression was detected [

17,

18]. Consistently, McFadyen et al. investigated the CYP1B1 expression in 172 patient samples of primary and metastatic ovarian cancers. An elevated CYP1B1 expression was determined in 92% of samples and frequently localised to the cytoplasm of cells with no obvious heterogeneity [

19]. Similarly, a significantly higher level of CYP1B1 expression was seen in almost 90% and 70% of primary and metastatic ovarian cancers, respectively [

20]. Importantly, neither CYP1B1 mRNA expression nor protein expression proved to be biomarkers of prognosis [

17,

19].

2.3. CYP2A6 and CYP2B6

Since CYP2A6 plays a major role in nicotine metabolism, it is implicated in tobacco-related diseases like lung cancer. Additionally, it is one of the numerous CYPs that is primarily engaged in the metabolism of many drugs like coumarin, halothane and tamoxifen. This enzyme is a liver-specific enzyme but displays extrahepatic expression in some organs [

4]. According to TCGA, data showed low CYP2A2 mRNA expression and absence of protein expression in samples of normal ovaries and ovarian cancer. For the CYP2B6 enzyme, expression of mRNA and protein was detected in neither normal ovary tissues nor ovarian cancers [

17,

18]. These data contrast with earlier studies reporting significant expression of CYP2A/2B enzymes in ovarian cancer tissues compared to normal ovary tissues [

19]. One possible explanation for these conflicting results is that the antibody used for the detection of CYP2A6 cross-reacts with CYP2A6 and CYP2B6 enzymes as both enzymes have nearly identical COOH-terminal amino acid sequences.

2.4. CYP2C8

The CYP2C subfamily comprises four members of closely homologous enzyme genes CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C18 and CYP2C19. These enzymes are mainly expressed in the human liver. The trifurcated, large active site of CYP2C8 resembles that of CYP3A4 and is different from other CYP2C family members, allowing it to handle substrates of various sizes and shapes [

21]. CYP2C8 is transcriptionally regulated by several factors and diverse nuclear receptors activating necessary elements within the gene's 59-flanking promoter region. These factors and/or receptors include but are not limited to constitutive androstane receptor (CAR), glucocorticoid receptor (GR), pregnane X receptor (PXR), hepatic nuclear factor-4a (HNF4a) and vitamin D receptor (VDR) [

22]. CYP2C8 is well recognised as participating in the metabolic biotransformation of endogenous compounds like over 100 different drugs, including but not limited to anticancers. CYP2C8 has been identified in many extrahepatic tissues including the heart, kidney, salivary ducts, tonsils, adrenal cortical cells and small and large intestines [

21]. Although low levels of CYP2C8 mRNA were found in normal ovaries, no evidence of protein expression was elaborated. However, CYP2C8 mRNA and protein were detected in primary ovarian cancer, and albite protein expression was weak [

17,

18]. These findings are consistent with other studies demonstrating CYP2C8 expression in most of the ovarian cancer samples examined [

19,

23].

2.5. CYP2C9

CYP2C9 is an epoxygenase enzyme metabolising several endogenous compounds like arachidonic acid and xenobiotics like anticancers. It is the second most abundant CYP expressed in liver cells after CYP3A4 [

4,

24]. About 15% to 20% of all drugs passing phase I metabolism are metabolised by CYP2C9. Furthermore, CYP2C9 expression was shown to be induced by rifampicin treatment [

4]. CYP2C9 expression was identified in numerous organs, where it was expressed differently in non-neoplastic and malignant human tissues. However, expression of CYP2C9 mRNA and protein was not detected in either normal ovaries or ovarian cancer [

8,

17,

25].

2.6. CYP2J2

CYP2J2 is an arachidonic acid epoxygenase enzyme that is regulated by activation of microRNA let-7b, protein-1 (AP-1), and the AP-1-like element. It is mainly involved in the metabolism of arachidonic acid generating four isomers of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) [

26]. Several lines of evidence highlighted the potential role of CYP2J2 and its mediated products in the cancer pathogenesis of many human tumours [

27]. In normal ovaries, the expression of CYP2J2 mRNA and protein expression was not identified [

17,

18]. However, high expression of CYP2J2 mRNA was found in a large patient cohort of primary and malignant ovarian cancers, compared to normal and benign tumours of the ovary [

17,

25]. Evidence of CYP2J2 protein expression was only available from one study reporting non-significant protein expression in ovarian cancers compared to normal ovaries [

17].

2.7. CYP2S1

CYP2S1 is an orphan CYP enzyme displaying many characteristics typical of enzymes of the CYP1 family. It shares dioxin-inducibility catalysed by AhR, suggesting a potential role in both exogenous and endogenous compound metabolism. It is primarily involved in the formation and metabolism of lipids such as prostaglandins and retinoids [

28]. Although studies on the expression of CYP2S1 are limited, available data revealed that comparable CYP2S1 expression patterns were determined at both mRNA and protein levels in normal ovaries [

19,

28]. These results are consistent with data from The Human Protein Atlas showing a similar fashion of expression of CYP2S1 mRNA and protein in normal ovaries [

18]. Moreover, CYP2S1 was more highly expressed in ovarian cancers than in healthy normal ovaries. Significant CYP2S1 expression was identified in metastatic ovarian tumours compared to primary ovarian cancers and healthy normal ovaries [

19,

28]. The implications of this finding remain to be determined.

2.8. CYP2U1

CYP2U1 is a hydroxylase enzyme implicated in the metabolism of fatty acids like arachidonic acid and N-arachidonoylserine. The up-regulation of CYP2U1 is induced by glutamate through phosphorylation of cAMP-response element binding (CREB) proteins and binding of these phosphorylated proteins with the CYP2U1 promoter in the nucleus [

29]. Investigations of the expression of CYP2U1 mRNA and protein revealed that low expression of CYP2U1 mRNA and protein was found in normal ovaries [

17,

19,

30]. However, moderate expression of CYP2U1 mRNA and protein was identified in ovarian cancers. Concurrently, a significant differential in the expression of the CYP2U1 enzyme was found, where the expression was high in primary and metastatic ovarian cancers compared to normal ovaries [

19].

2.9. CYP3A4

CYP3A4 is the most abundant CYP found in adult human liver, making up about 30% of the overall CYP protein level. It is also found in high concentrations in the colon, small bowel and pancreas [

4,

18]. CYP3A4 plays an essential role in the activation and detoxification of a wide range of xenobiotics and endogenous compounds. It is involved in the activation of several procarcinogens like aflatoxins, polycyclic hydrocarbon dihydrodiols, and heterocyclic amines. Importantly, CYP3A4 is also involved in the metabolism of 60% of pharmaceutical drugs, together with chemotherapy used for ovarian cancer treatment, such as docetaxel and paclitaxel [

4,

31]. Furthermore, CYP3A4 was shown to convert testosterone and oestrogen to several metabolites, where they play a major role in the aetiology of ovarian and breast cancers [

32]. Studies of cancers have found differential CYP3A4 expression in breast, oesophageal, colorectal and Ewing's sarcoma tumours compared to matched normal tissues [

17,

18]. Available data on the expression of CYP3A4 mRNA and protein in normal and cancerous ovarian tissues are contradictory. CYP3A4 mRNA was found at basal levels in normal ovaries, whereas CYP3A4 protein was not detected. Similarly, extremely low levels of CYP3A4 mRNA were identified in primary ovarian cancer samples, while no CYP3A4 protein was expressed. These findings were consistent with DeLoia et al.’s study reporting rare and extremely low CYP3A4 mRNA expression in ovarian cancer [

23]. In contrast, high and more frequent CYP3A4 protein expression was found in both normal ovaries and primary ovarian cancer, although differential expression was not significant [

19].

2.10. CYP3A5

CYP3A5 is a mono-oxygenase enzyme whose expression was found in hepatic and extrahepatic organ tissues. This enzyme is involved in the production of steroids and lipids and the metabolism of many drugs such as anticancers. Although the CYP3A5 enzyme’s substrate specificity is similar to CYP3A4, CYP3A5 is considered less crucial for drug elimination due to its substantially lower levels of expression than CYP3A4 in adult livers [

33]. Compelling data on the expression of CYP3A5 mRNA and protein in normal and cancerous ovary tissues are available. Data from The Human Protein Atlas showed that healthy normal ovary tissues express basal levels of CYP3A5 mRNA [

18]. Consistently, CYP3A5 protein was found to be less frequently expressed in normal ovaries. In contrast, significant expression of CYP3A5 was determined in primary and metastatic ovarian cancers relative to low expression in normal ovaries. However, this significant expression did not prove to be a prognostic marker for ovarian cancers [

17,

19,

23].

2.11. CYP3A7

CYP3A7 is a foetal hepatic enzyme that shares about 93% homology with CYP3A4. During embryonic development, CYP3A7 is mainly involved in estriol biosynthesis, all-trans retinoic acid clearance and xenobiotic metabolism [

34]. While CYP3A7 is mainly expressed in the foetal liver, it is also available in some adult livers, albeit at low levels compared to CYP3A4. It is also found in foetus extrahepatic tissues such as intestine, placenta, endometrial, prostate, adrenal gland and lungs [

35]. However, quantitative data on CYP3A7 expression in adults’ hepatic and extrahepatic tissues, particularly normal ovaries, are limited. CYP3A7 mRNA expression was less frequently found in normal ovaries [

18]. Meantime, a similar pattern of expression was found in a large cohort of ovarian cancers [

17]. Evidence on CYP3A7 protein expression came from one study demonstrating that CYP3A7 protein was significantly expressed in both primary and metastatic ovarian cancers compared to low levels of expression in normal ovaries [

19]. This finding contradicts CYP3A7 mRNA expression data on ovarian cancers. One explanation for this finding may arise from the specificity of the antibody used to detect CYP3A7 protein expression as CYP3A4-to-CYP3A7 cross-reactivity may occur.

2.12. CYP3A43

CYP3A43 is a hydroxylase enzyme that is the least abundant and characterised member of the CYP3 family. Its amino acid sequence shares about 76%, 76%, and 72% homology with CYP3A4, CYP3A5, and CYP3A7, respectively [

36]. To date, only dexamethasone and rifampicin have been found to induce the expression of CYP3A43. Moreover, recent data indicated the potential role of CYP3A43 in metabolising endogenous and xenobiotic compounds like other CYP3 members, albeit to a lesser extent. CYP3A43 was found to participate in the biotransformation of endogenous testosterone and some drugs including alprazolam and olanzapine. CYP3A43 is primarily expressed in the prostate but is also present at relatively low levels in the hepatic tissues compared to other CYP3 members [

37]. Available data on CYP3A43 expression patterns in normal and cancerous ovary tissues are controversial. Data from The Human Protein Atlas showed that neither CYP3A43 mRNA nor CYP3A43 protein were detected in normal ovaries [

17]. Moreover, TCGA data on ovarian cancers demonstrated that CYP3A43 mRNA was identified at extremely low levels, while the protein was not detected at all [

17]. On the other hand, CYP3A43 protein was found more frequently expressed in primary and metastatic ovarian cancers. Significant differences in the intensity of CYP3A43 protein expression between samples of primary ovarian cancer and normal ovary samples were particularly explored [

19].

2.13. CYP4B1

CYP4B1 is an omega-hydroxylase orphan enzyme and is the only known member of the CYP4B family. CYP4B1 expression was found to be induced by androgens and down-regulated by soy isoflavones [

38,

39]. This pattern of expression was regulated by multiple nuclear receptors like nuclear factor-kappa light chain enhancer of activated B cells (NF-kB), activator protein 1, hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1), retinoid X receptor (RXR) and lastly AhR [

5]. Additionally, CYP4B1 expression is predominantly found in human lungs and other human organs, albeit at extremely low levels [

5,

40]. In the carcinogenesis process, CYP4B1 played an important role through neovascularisation and procarcinogen activation. Recent data showed that CYP4B1 gene expression was identified in cancers of the lung, liver, bladder, prostate, breast and ovaries [

5,

40]. In ovarian cancers, patients with recurrent serous ovarian cancer were found to have higher CYP4B1 mRNA than patients with cured ovarian cancer. In contrast, only 8.3% of patients with ovarian cancers displayed medium CYP4B1 protein expression [

17,

41]. In normal ovaries, low levels of CYP4B1 mRNA were found while no protein expression was seen [

18].

2.14. CYP4Z1

CYP4Z1 is an orphan enzyme with fatty acid hydroxylase or epoxygenase catalytic activities. Induction of CYP4Z1 mRNA is conditionally regulated by progesterone and glucocorticoids and blocked by the steroid receptor inhibitor mifepristone [

42]. CYP4Z1 possesses both hydroxylase and epoxygenase catalytic activities, particularly converting mid-chain fatty acids (lauric and myristic acids) to monohydroxylated derivatives and arachidonic acid to 20-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid (20-HETE) or 14,15-epoxyeicosatrienoic acid (14,15-EET), respectively [

43,

44]. CYP4Z1 mRNA expression is preferentially found in mammary glands, but smaller levels are detected in the heart, liver, brain, kidney, prostate, testes, lungs and ovaries [

10,

45]. Clinical investigations into the CYP4Z1 protein expression profile in cancers reveal an attractive trend: a significant difference in CYP4Z1 protein expression between many cancers and their corresponding normal tissues, such as breast, lung, prostate, bladder, colon, cervix and, recently, ovaries. Importantly, CYP4Z1 expression was found to be associated with high-grade and late stages of the disease and proved to be a poor prognostic marker for these cancers [

8,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14,

19,

46]. Interestingly, CYP4Z1 expression was found to stimulate the generation of CYP4Z1 autoantibodies in the sera of patients with cancers of the breast, lung, colon, prostate and ovaries. However, no significant difference in the levels of CYP4Z1 autoantibodies generated in the sera of these cancer patients was found compared to normal controls [

47,

48]. A possible explanation for this finding is that the sample size in these studies is not large enough to demonstrate such differences.

2.15. CYP26A1

CYP26A1 is one of the highly conserved members of the CYP26 family along with CYP26B1 and CYP26C1. CYP26A1 works by metabolising and eliminating all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA), a bioactive molecule of retinol or vitamin A, implicated in the regulation of cellular differentiation, migration, proliferation, and death [

49]. CYP26A1 overexpression was found to trigger cell survival and antiapoptotic pathways by downregulation of tumour suppressor genes and induction of oncogenes [

49,

50]. The main function of CYP26A1 seems to be in the biotransformation of retinoic acid (RA) to its primary metabolite 4-OH-RA, along with other minor metabolites. Moreover, CYP26A1 is also involved in the metabolism of exogenous compounds like tazarotenic acid [

50,

51]. CYP26A1 mRNA was predominantly found in the human liver, with smaller amounts found in other organs including the lungs, kidneys, testes and skin. In normal ovaries, CYP26A1 mRNA was not detected [

18], although low CYP26A1 protein expression was exhibited in less than 10% of samples examined [

19]. Importantly, comparable levels of CYP26A1 mRNA were found in ovarian cancers [

17]. Consistently, significant high CYP26A1 protein expression was displayed in primary ovarian cancers along with intense expression in metastatic ones [

19].

2.16. CYP51A1

CYP51A1 is a 14α-demethylase enzyme that plays an important role in the biosynthesis of cholesterol. It is a highly conserved enzyme possessing about 95% amino acid sequence identity among mammals [

52]. CYP51A1 catalyses selectively lanosterol and 24,25-dihydrolanosterol via alpha-demethylation, forming other sterols necessary for cholesterol biosynthesis. CYP51A1 mRNA is widely distributed throughout the human body tissues, although the highest levels were present in testes [

53]. Limited data are available on the expression of CYP51A1 mRNA and protein in normal and cancerous ovary tissues. Data showed that comparable levels of CYP51A1 mRNA were found in normal ovaries, while no protein expression was detected [

54]. A similar pattern of expression for CYP51A1 mRNA was also displayed in ovarian cancers, though low protein expression was detected in less than 10% of ovarian cancer samples examined [

17]. In contrast, CYP51A1 protein was significantly expressed in almost half of the patients with primary ovarian cancer, compared to weak expression exhibited in almost 10% of normal ovary samples. Moreover, CYP51A1 protein expression was displayed in almost 20% of metastatic ovarian cancer samples [

19].

3. Impact of CYP Polymorphism on Risk and Prognosis of Ovarian Cancer

In light of the importance of CYPs in the biotransformation of precarcinogens, limited studies have been conducted to identify genetic variants of each CYP that may predispose to ovarian cancer. Several studies examined the association between the genotype status of the most common CYP1A1 polymorphisms (Ile462Val, MspI, M4 and Thr461Asn) and with risk of ovarian cancer development [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59]. The risk of developing ovarian cancer increased among patients with genetic variants of CYP1A1 Ile462Val, MspI and M4 [

55,

56,

57,

58,

59]. No association of ovarian cancer risk was found with CYP1A1*4 (Thr461Asn) alleles [

59]. Moreover, a positive association of CYP1A2 genetic variants with ovarian cancer risk was detected in patients who were tobacco smokers or coffee drinkers. No relevant associations of CYP1A2 genetic variants with ovarian cancer risk were found in non-smokers or non-coffee drinkers [

60,

61]. Regarding CYP1B1, all studies except for Zhang's study found that polymorphisms in the CYP1B1 gene were not significantly associated with ovarian cancer susceptibility [

62,

63,

64,

65]. Here, the genetic variant of CYP1B1 rs1056836 showed a significant association with ovarian cancer susceptibility among Asians and Caucasians, while no association was detected among African Americans [

65].

Additionally, reports showed that the CYP3A4 rs2740574 variant is inversely associated with ovarian cancer morbidity [

66,

67]. These data contrast with earlier studies indicating an absence of CYP3A4 rs2740574 variant association with ovarian cancer risk [

68,

69]. Other CYP3A4 genetic variants had no impact on ovarian cancer susceptibility [

69]. Similarly, the difference in CYP17 genetic polymorphism of T→C between ovarian cancer cases and controls was not significant; therefore, this genetic variant did not affect ovarian cancer risk [

70]. However, a recent study demonstrated that the genetic variant of CYP17A1 (rs743572) showed a significant association with ovarian cancer risk [

71]. Regarding CYP19, the risk of ovarian cancer increased among carriers of one or both genetic variants of CYP19013 A or CYP19027 G [

72]. Moreover, women carriers with CYP19 gene polymorphisms of (TTTA) 11 and (TTTA) 12 were at a twofold and fourfold increased risk of developing ovarian cancer, respectively [

73]. Recently, the rs10046 (CYP19A1) variant was associated with an increased risk of developing ovarian cancer [

71]. Considering the apparent limitations on the number of investigations and sample size, studies on the polymorphisms of CYP2D6, CYP2C8, CYP2E1 and CYP3A5 genes demonstrated a lack of genotypes associations with ovarian cancer susceptibility [

69,

74,

75,

76,

77]. In summary, no significant conclusions can be drawn from these observational studies. This is largely because of the limited number of studies recruiting small numbers of cases and controls, with improper confounding factor control and a lack of information regarding CYP gene interactions with some other genes and/or external environmental factors.

4. Impact of CYP Polymorphism on Chemotherapeutic Agent Metabolism in Ovarian Cancer

The pharmacological response of chemotherapeutic drugs in patients with ovarian cancer is greatly influenced by CYP genetic polymorphisms. They trigger changes in drug response varying from adverse drug reactions to the absence of clinical efficacy. Many anticancer drugs such as cyclophosphamide, docetaxel, paclitaxel, 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin, and cisplatin are metabolised by CYP1B1 [

78]. However, genetic polymorphisms of CYP1B1 had no association with patient outcomes, chemotherapy toxicity and chemotherapy resistance in ovarian cancers [

31,

79]. Regarding CYP3A4 polymorphisms, compared with patients carrying AA, the risk of disease progression and chemotherapy resistance of platinum-based drugs was elevated in patients carrying CYP3A4 rs2740574 with at least one G allele [

80]. Moreover, CYP3A4 rs2740574 was associated with worse overall survival in patients with ovarian cancer treated with platinum and taxane drugs [

81]. Additionally, the mechanism of paclitaxel metabolism was altered by the CYP3A4 rs2740574 activity in vivo, but not the overall paclitaxel clearance [

82]. In contrast, the CYP3A4*16 genetic allele did not affect paclitaxel pharmacokinetics and metabolism [

83]. Despite strong structural similarity (85% homology) between CYP3A4 and CYP3A5, CYP3A5 polymorphisms had no association with overall survival, patient outcomes or chemotherapy toxicity in ovarian cancer patients treated with platinum and taxane drugs [

31,

69,

80].

In large cohorts of patients with ovarian cancer treated with carboplatin and either paclitaxel or docetaxel, CYP2C8 gene polymorphisms had no impact on patient outcome and chemotherapy-induced toxicity [

31]. Similarly, Gagno et al. found no relation between CYP2C8 polymorphisms with overall survival, progression of disease and platinum sensitivity in ovarian cancer patients treated with platinum regimens [

80]. Other studies highlighted the importance of CYP2C8 polymorphisms, particularly the CYP2C8*3 genotype in the pharmacokinetics of paclitaxel. Ovarian cancer patients carrying the CYP2C8*3 genotype had a decreased clearance rate of unbound paclitaxel compared to wild-type patients [

82,

84]. Regarding CYP2C9 polymorphisms, this particular genotype of CYP2C9 rs1057910 was associated with a reduced response rate, worse progression of disease and lower overall survival rate in ovarian cancer patients treated with platinum drugs [

80]. Additionally, CYP genetic polymorphisms are also strongly correlated with chemotherapy-induced adverse haematological effects in patients with ovarian cancer. Patients carrying CYP3A5∗3/∗1 genotypes had a significant association with carboplatin/paclitaxel-induced neutropenia and leukopenia compared to patient controls [

85,

86]. Consistently, the CYP2C8-HapC genetic variant was shown to significantly induce neutropenia and leukopenia in ovarian cancer patients treated with carboplatin/paclitaxel regimens [

85]. Moreover, CYP2C8*3 polymorphism was found to induce myelosuppression and motor neuropathy in ovarian cancer patients treated with a paclitaxel regimen [

82]. Consequently, this may describe the dissatisfactory therapeutic outcome in certain patients with ovarian cancer. CYP polymorphisms in chemotherapy metabolism in ovarian cancer seem to play a relevant role; however, the current evidence from the above small number of studies remains slightly conflicting and limited.

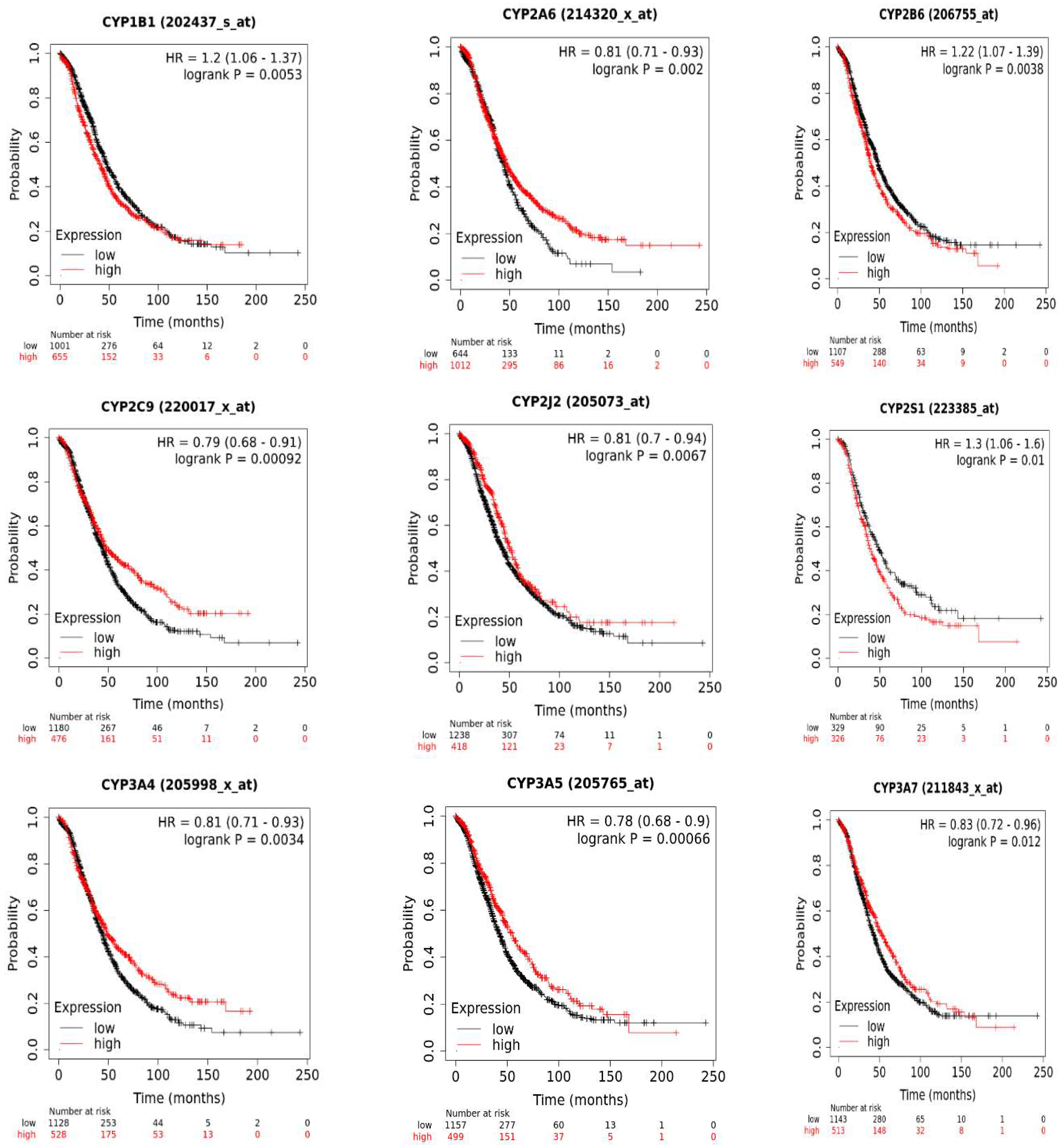

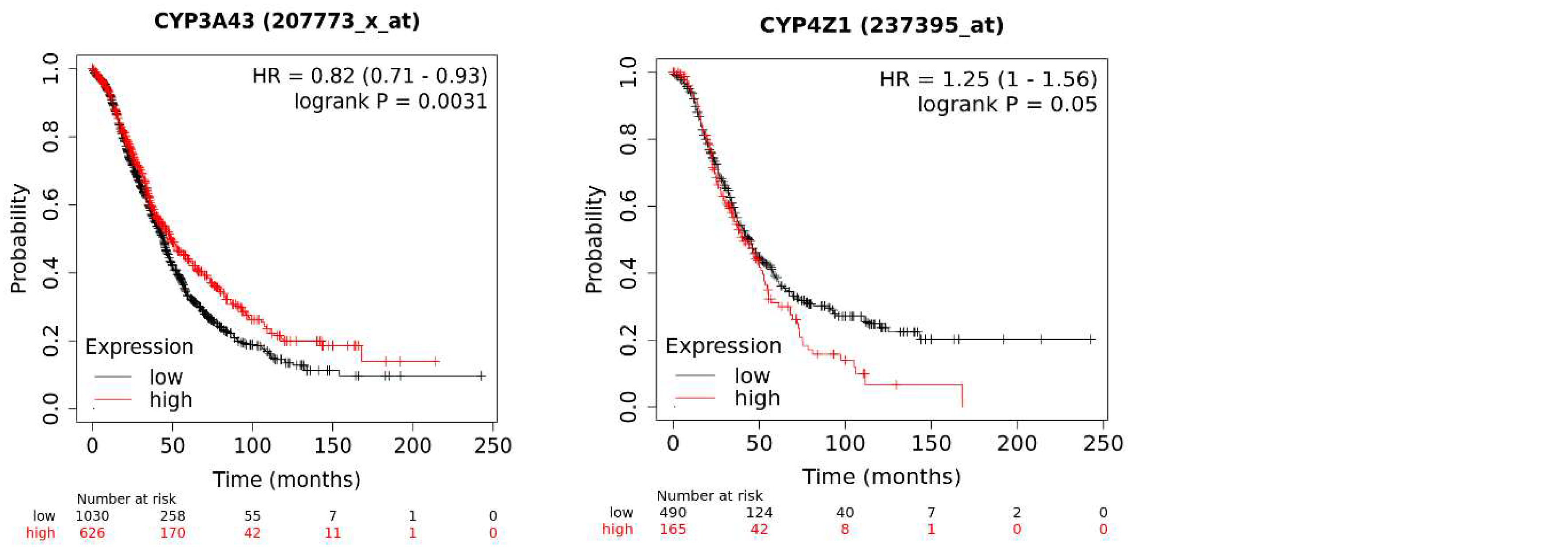

5. Implications of CYP Isoform Expression for Patient Survival

The KM plotter database analysis of CYP genes implicated in tumorigenesis and chemotherapy metabolism in ovarian cancer revealed an association of several isoforms with patient overall survival: here, the mRNA expression of 17 CYP genes, with 11 genes exhibiting significant expression and six not exhibiting significant expression in terms of patient survival. High mRNA expression of CYP1B1, CYP2B6, CYP2S1, and CYP4Z1 was significantly associated with poor patient overall survival. In contrast, high mRNA expression of CYP2A6, CYP2C9, CYP2J2, CYP3A4, CYP3A5, CYP3A7, and CYP3A43 connoted good prognosis for ovarian cancer patients. Other CYP isoforms showed no significant association. Higher expression of CYP3 enzymes has been shown to have protective effects against many cancers by suppressing cancer progression and metastasis [

87,

88]. Moreover, lower expression of CYP3 enzymes, particularly CYP3A4, may influence the survival of ovarian cancer patients because of ineffective metabolism or activation of standard drugs cyclophosphamide and doxorubicin used for the treatment of ovarian cancers [

89].

Figure 1.

The effect of CYP mRNA expression on ovarian cancer survival using the Kaplan-Meier analysis. The p-value was considered significant if p≤0.05.

Figure 1.

The effect of CYP mRNA expression on ovarian cancer survival using the Kaplan-Meier analysis. The p-value was considered significant if p≤0.05.

6. Future Perspectives

Despite major developments in treatment options over the last decade, selective ovarian cancer treatment with limited adverse effects is still a significant challenge. Therefore, individual expression of CYPs in ovarian cancers may represent potential therapeutic targets for the development of specific diagnostic biomarkers and selective tumour-directed therapies. Such an opportunity can be employed by a variety of therapeutic approaches such as CYP-based prodrug activation, CYPs targeted immunotherapy, and CYP inhibitors. The CYP-based prodrug activation approach has significant potential for providing substantial therapeutic advantages while resolving the issues related to toxicity that limit the administration of many of the current anticancer drugs. Examples of such strategies include CPA, tegafur and tamoxifen. However, administration of these agents is accompanied by side effects because the bioactivation of these prodrugs is not tumour selective [

90]. Although exciting research in this field has been reported, many prodrug approaches targeting selective tumour expression of specific CYPs have not yet resulted in drugs being approved for clinical use.

Among CYPs expressed in ovarian cancer, only a few overexpressed enzymes have the potential for drug development to treat ovarian cancer. Several CYP1B1 cancer treatment strategies are being developed, such as prodrug activation, inhibitors and immunotherapy. Some of the anticancer prodrugs being examined for CYP1B1 activation include aryl oximes, resveratrol, and phortress [

90]. Moreover, CYP1B1 inhibitors like piceatannol are aimed to promote efficacy and modulate the cytotoxicity of some types of chemotherapeutic agents [

91]. Additionally, the CYP1B1 vaccine ZYC300 is an immunotherapy strategy that aims to kill cancer cells expressing CYP1B1 by inducing T-cell activity [

90]. All of these CYP1B1-based cancer therapies open and warrant new options for the treatment of ovarian cancer.

Of importance is the overexpression of orphan enzyme CYP4Z1 in ovarian cancer [

14,

19]. Its distinct expression pattern in ovarian cancer makes it an attractive candidate for CYP4Z1-directed therapies. Given the vast expertise with various human CYPs as prodrug activators, the discovery of suitable candidate CYP4Z1-activated prodrugs is plausible. Once these prodrugs are available, such compounds can be examined in xenograft models of ovarian cancer or other positive-CYP4Z1 cancers as high levels of CYP4Z1 are abundant in the target tissue and a gene delivery system is not needed. Nevertheless, one major challenge to the discovery of such prodrugs is limited data about the CYP4Z1 catalytic properties. Calculating how a prodrug could be activated by a fatty acid hydroxylase enzyme with only the four substrates identified so far is difficult. Thus, more research is required to either broaden the range of CYP4Z1 substrates or to better understand the reaction types executed by CYP4Z1. Another strategy for ovarian cancer treatment is to inhibit CYP4Z1 activity. In contrast to CYP19 (aromatase) [

92], CYP4Z1's functional role in the transformation of normal cells to cancer cells is uncertain particularly in ovarian cells. Thus, for now, the development of CYP4Z1-activated prodrugs appears to be a more feasible strategy as abundant levels of CYP4Z1 expression are available in cancer cells for successful activation of prodrugs, even though its functional role is unknown. Since all subtypes of ovarian cancer do express CYP4Z1, CYP4Z1-activated prodrugs should in principle be effective against all subtypes of ovarian cancer and ovarian cancer-derived metastases that have also been proven to express CYP4Z1 [

14,

19]. Importantly, another therapeutic option for the treatment of ovarian cancer came from the recent breakthrough in the detection of generated CYP4Z1 autoantibodies on the surface of ovarian cancer cells [

47]. This may open novel avenues for the development of successful immunotherapies for this cancer.

Although not specific to ovarian cancer, CYP2S1 expression is significantly higher in ovarian cancer-derived metastases than in primary tumours and healthy tissues [

19]. Such a pattern of CYP2S1 expression in metastatic sites makes it a suitable candidate for the development of CYP2S1-directed antimetastatic therapies. However, determining endogenous ligands, and therefore deorphanising this enzyme, appears to be essential in understanding its function in ovarian tumorigenesis.

CYP expression in ovarian cancer can be explored not only because of their overexpression in cancer cells but also due to the unique microenvironment whereby cancers occur even when a CYP exists but is not definitely overexpressed. One of the primary characteristics of the tumour microenvironment that CYP-targeted treatment currently takes advantage of for patient benefit is hypoxia [

93]. The discovery of AQ4N (Banoxantrone), a rationally designed prodrug, has emerged from knowledge of the bioreductive ability of CYPs in solid tumours influenced by hypoxic stress. This prodrug is bioactivated under hypoxic conditions to potent topoisomerase II inhibitor (AQ4) mainly by CYP3A4, CYP1B1, CYP1A1, CYP2S1, CYP2B6 and CYP2W1 [

94]. As ovarian cancer patients with expression of such enzymes have a high risk of mortality and metastasis, this strategy offers a real opportunity for the development of CYP-activated bioreductive prodrugs to be used as adjuvant therapy along with standard treatment.

Finally, gaining a thorough understanding of CYP expression and functions is critical for optimising existing ovarian cancer therapies and directing the current and new initiatives for developing novel drugs with enhanced therapeutic potential and fewer adverse effects for patient advantage.

7. Methods

7.1. Survival Prognosis Analysis of CYP Isoforms

To assess the prognostic value of CYP isoforms on ovarian cancer patients' survival, the Kaplan-Meier Plotter web-based tool was used [

95]. It is a publicly accessible online database via KM plotter:

http://kmplot.com/analysis/index.php?p=service&cancer=liver_rnaseq and data on gene expression were obtained from individuals participating in TCGA, Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) and European Genome-phenome Archive (EGA). Such a database can assess the clinical impacts of 54,000 genes on survival in 21 different cancer types. The program generates Kaplan-Meier survival plots to investigate the impact of certain gene expression rates on the prognosis of ovarian cancer patients. Here, the median of CYP isoform expression was used to distinguish all patients into two distinct categories: high expression and low expression.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

The authors are very thankful to the Deanship of Scientific Research at Mutah University for supporting this project (743/2023).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

| AhR |

Aryl hydrocarbon receptor |

| CAR |

Constitutive androstane receptor |

| CREB |

CAMP-response element binding |

| CYP |

Cytochrome P450 |

| EGA |

European Genome-phenome Archive |

| GEO |

Gene Expression Omnibus |

| GR |

Glucocorticoid receptor |

| PXR |

Pregnane X receptor |

| RA |

Retinoic acid |

| RXR |

Retinoid X receptor |

| TCGA |

The Cancer Genome Atlas |

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matulonis, U.A.; Sood, A.K.; Fallowfield, L.; Howitt, B.E.; Sehouli, J.; Karlan, B.Y. Ovarian cancer. Nature Reviews Disease Primers 2016, 2, 16061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carter, J.S.; Downs, L.S., Jr. Ovarian Cancer Tests and Treatment. Female Patient (Parsippany) 2011, 36, 30–35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sneha, S.; Baker, S.C.; Green, A.; Storr, S.; Aiyappa, R.; Martin, S.; Pors, K. Intratumoural Cytochrome P450 Expression in Breast Cancer: Impact on Standard of Care Treatment and New Efforts to Develop Tumour-Selective Therapies. Biomedicines 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.; Alshagga, M.; Ong, C.E.; Chieng, J.Y.; Pan, Y. Cytochrome P450 4B1 (CYP4B1) as a target in cancer treatment. Human & experimental toxicology 2020, 39, 785–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, R.D.; Njar, V.C.O. Targeting cytochrome P450 enzymes: a new approach in anti-cancer drug development. Bioorganic & medicinal chemistry 2007, 15, 5047–5060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, B.; Yan, D.; Yan, H.; Yuan, J. Cytochrome P450: Implications for human breast cancer. Oncol Lett 2021, 22, 548–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saraireh, Y.M.; Alshammari, F.; Youssef, A.M.M.; Al-Sarayreh, S.; Almuhaisen, G.H.; Alnawaiseh, N.; Al Shuneigat, J.M.; Alrawashdeh, H.M. Profiling of CYP4Z1 and CYP1B1 expression in bladder cancers. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 5581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshammari, F.O.F.O.; Al-Saraireh, Y.M.; Youssef, A.M.M.; Al-Sarayra, Y.M.; Alrawashdeh, H.M. Cytochrome P450 1B1 Overexpression in Cervical Cancers: Cross-sectional Study. Interact J Med Res 2021, 10, e31150–e31150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saraireh, Y.M.; Alboaisa, N.S.; Alrawashdeh, H.M.; Hamdan, O.; Al-Sarayreh, S.; Al-Shuneigat, J.M.; Nofal, M.N. Screening of cytochrome 4Z1 expression in human non-neoplastic, pre-neoplastic and neoplastic tissues. Ecancermedicalscience 2020, 14, 1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Saraireh, Y.M.; Alshammari, F.; Youssef, A.M.M.; Al-Sarayra, Y.M.; Al-Saraireh, R.A.; Al-Muhaisen, G.H.; Al-Mahdy, Y.S.; Al-Kharabsheh, A.M.; Abufraijeh, S.M.; Alrawashdeh, H.M. Cytochrome 4Z1 Expression Is Correlated with Poor Prognosis in Patients with Cervical Cancer. Current oncology (Toronto, Ont.) 2021, 28, 3573–3584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Saraireh, Y.M.; Alshammari, F.; Youssef, A.M.M.; Al-Sarayreh, S.; Almuhaisen, G.H.; Alnawaiseh, N.; Al-Shuneigat, J.M.; Alrawashdeh, H.M. Cytochrome 4Z1 Expression is Associated with Poor Prognosis in Colon Cancer Patients. OncoTargets and therapy 2021, 14, 5249–5260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Saraireh, Y.M.; Alshammari, F.; Youssef, A.M.M.; Al-Tarawneh, F.; Al-Sarayreh, S.; Almuhaisen, G.H.; Satari, A.O.; Al-Shuneigat, J.; Alrawashdeh, H.M. Cytochrome 4Z1 Expression is Associated with Unfavorable Survival in Triple-Negative Breast Cancers. Breast cancer (Dove Medical Press) 2021, 13, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Saraireh, Y.M.; Alshammari, F.; Satari, A.O.; Al-Mahdy, Y.S.; Almuhaisen, G.H.; Abu-Azzam, O.H.; Uwais, A.N.; Abufraijeh, S.M.; Al-Kharabsheh, A.M.; Al-Dalain, S.M.; et al. Cytochrome 4Z1 Expression Connotes Unfavorable Prognosis in Ovarian Cancers. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania) 2022, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piotrowska, H.; Kucinska, M.; Murias, M. Expression of CYP1A1, CYP1B1 and MnSOD in a panel of human cancer cell lines. Molecular and cellular biochemistry 2013, 383, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Y.K.; Lau, K.M.; Mobley, J.; Jiang, Z.; Ho, S.M. Overexpression of cytochrome P450 1A1 and its novel spliced variant in ovarian cancer cells: alternative subcellular enzyme compartmentation may contribute to carcinogenesis. Cancer research 2005, 65, 3726–3734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, D.; Berchuck, A.; Birrer, M.; Chien, J.; Cramer, D.W.; Dao, F.; Dhir, R.; DiSaia, P.; Gabra, H.; Glenn, P.; et al. Integrated genomic analyses of ovarian carcinoma. Nature 2011, 474, 609–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhlen, M.; Zhang, C.; Lee, S.; Sjöstedt, E.; Fagerberg, L.; Bidkhori, G.; Benfeitas, R.; Arif, M.; Liu, Z.; Edfors, F.; et al. A pathology atlas of the human cancer transcriptome. Science (New York, N.Y.) 2017, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Downie, D.; McFadyen, M.C.; Rooney, P.H.; Cruickshank, M.E.; Parkin, D.E.; Miller, I.D.; Telfer, C.; Melvin, W.T.; Murray, G.I. Profiling cytochrome P450 expression in ovarian cancer: identification of prognostic markers. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2005, 11, 7369–7375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadyen, M.C.; Cruickshank, M.E.; Miller, I.D.; McLeod, H.L.; Melvin, W.T.; Haites, N.E.; Parkin, D.; Murray, G.I. Cytochrome P450 CYP1B1 over-expression in primary and metastatic ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer 2001, 85, 242–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, J.T.; Filppula, A.M.; Niemi, M.; Neuvonen, P.J. Role of Cytochrome P450 2C8 in Drug Metabolism and Interactions. Pharmacol Rev 2016, 68, 168–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilante, C.L.; Niemi, M.; Gong, L.; Altman, R.B.; Klein, T.E. PharmGKB summary: very important pharmacogene information for cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily C, polypeptide 8. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics 2013, 23, 721–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeLoia, J.A.; Zamboni, W.C.; Jones, J.M.; Strychor, S.; Kelley, J.L.; Gallion, H.H. Expression and activity of taxane-metabolizing enzymes in ovarian tumors. Gynecologic oncology 2008, 108, 355–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evangelista, E.A.; Cho, C.W.; Aliwarga, T.; Totah, R.A. Expression and Function of Eicosanoid-Producing Cytochrome P450 Enzymes in Solid Tumors. Frontiers in pharmacology 2020, 11, 828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freedman, R.S.; Wang, E.; Voiculescu, S.; Patenia, R.; Bassett, R.L., Jr.; Deavers, M.; Marincola, F.M.; Yang, P.; Newman, R.A. Comparative analysis of peritoneum and tumor eicosanoids and pathways in advanced ovarian cancer. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2007, 13, 5736–5744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.; Ju, W.; Hao, H.; Wang, G.; Li, P. Cytochrome P450 2J2: distribution, function, regulation, genetic polymorphisms and clinical significance. Drug Metabolism Reviews 2013, 45, 311–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, J.G.; Chen, C.L.; Card, J.W.; Yang, S.; Chen, J.X.; Fu, X.N.; Ning, Y.G.; Xiao, X.; Zeldin, D.C.; Wang, D.W. Cytochrome P450 2J2 promotes the neoplastic phenotype of carcinoma cells and is up-regulated in human tumors. Cancer research 2005, 65, 4707–4715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saarikoski, S.T.; Wikman, H.A.; Smith, G.; Wolff, C.H.; Husgafvel-Pursiainen, K. Localization of cytochrome P450 CYP2S1 expression in human tissues by in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry. The journal of histochemistry and cytochemistry : official journal of the Histochemistry Society 2005, 53, 549–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuban, W.; Daniel, W.A. Cytochrome P450 expression and regulation in the brain. Drug Metabolism Reviews 2021, 53, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, S.S.; Helvig, C.; Taimi, M.; Ramshaw, H.A.; Collop, A.H.; Amad, M.; White, J.A.; Petkovich, M.; Jones, G.; Korczak, B. CYP2U1, a novel human thymus- and brain-specific cytochrome P450, catalyzes omega- and (omega-1)-hydroxylation of fatty acids. The Journal of biological chemistry 2004, 279, 6305–6314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, S.; Paul, J.; King, C.R.; Gifford, G.; McLeod, H.L.; Brown, R. Pharmacogenetic assessment of toxicity and outcome after platinum plus taxane chemotherapy in ovarian cancer: the Scottish Randomised Trial in Ovarian Cancer. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2007, 25, 4528–4535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kandel, S.E.; Han, L.W.; Mao, Q.; Lampe, J.N. Digging Deeper into CYP3A Testosterone Metabolism: Kinetic, Regioselectivity, and Stereoselectivity Differences between CYP3A4/5 and CYP3A7. Drug Metab Dispos 2017, 45, 1266–1275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lolodi, O.; Wang, Y.M.; Wright, W.C.; Chen, T. Differential Regulation of CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 and its Implication in Drug Discovery. Current drug metabolism 2017, 18, 1095–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevrioukova, I.F. Structural Basis for the Diminished Ligand Binding and Catalytic Ability of Human Fetal-Specific CYP3A7. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Lampe, J.N. Neonatal cytochrome P450 CYP3A7: A comprehensive review of its role in development, disease, and xenobiotic metabolism. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics 2019, 673, 108078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westlind, A.; Malmebo, S.; Johansson, I.; Otter, C.; Andersson, T.B.; Ingelman-Sundberg, M.; Oscarson, M. Cloning and tissue distribution of a novel human cytochrome p450 of the CYP3A subfamily, CYP3A43. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2001, 281, 1349–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Machalz, D.; Liu, S.; Wolf, C.A.; Wolber, G.; Parr, M.K.; Bureik, M. Metabolism of the antipsychotic drug olanzapine by CYP3A43. Xenobiotica; the fate of foreign compounds in biological systems 2022, 52, 413–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imaoka, S.; Yoneda, Y.; Sugimoto, T.; Hiroi, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Nakatani, T.; Funae, Y. CYP4B1 is a possible risk factor for bladder cancer in humans. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2000, 277, 776–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satih, S.; Chalabi, N.; Rabiau, N.; Bosviel, R.; Fontana, L.; Bignon, Y.-J.; Bernard-Gallon, D.J. Gene expression profiling of breast cancer cell lines in response to soy isoflavones using a pangenomic microarray approach. OMICS 2010, 14, 231–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Jia, Y.; Shi, C.; Kong, D.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wei, A.; Wang, D. CYP4B1 is a prognostic biomarker and potential therapeutic target in lung adenocarcinoma. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0247020–e0247020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barlin, J.N.; Jelinic, P.; Olvera, N.; Bogomolniy, F.; Bisogna, M.; Dao, F.; Barakat, R.R.; Chi, D.S.; Levine, D.A. Validated gene targets associated with curatively treated advanced serous ovarian carcinoma. Gynecologic oncology 2013, 128, 512–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savas, U.; Hsu, M.H.; Griffin, K.J.; Bell, D.R.; Johnson, E.F. Conditional regulation of the human CYP4X1 and CYP4Z1 genes. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics 2005, 436, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zollner, A.; Dragan, C.A.; Pistorius, D.; Muller, R.; Bode, H.B.; Peters, F.T.; Maurer, H.H.; Bureik, M. Human CYP4Z1 catalyzes the in-chain hydroxylation of lauric acid and myristic acid. Biol Chem 2009, 390, 313–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, M.G.; Ray, S.; Amorosi, C.J.; Sitko, K.A.; Kowalski, J.P.; Paco, L.; Nath, A.; Gallis, B.; Totah, R.A.; Dunham, M.J.; et al. Expression and Functional Characterization of Breast Cancer-Associated Cytochrome P450 4Z1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Drug Metab Dispos 2017, 45, 1364–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rieger, M.A.; Ebner, R.; Bell, D.R.; Kiessling, A.; Rohayem, J.; Schmitz, M.; Temme, A.; Rieber, E.P.; Weigle, B. Identification of a novel mammary-restricted cytochrome P450, CYP4Z1, with overexpression in breast carcinoma. Cancer research 2004, 64, 2357–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tradonsky, A.; Rubin, T.; Beck, R.; Ring, B.; Seitz, R.; Mair, S. A search for reliable molecular markers of prognosis in prostate cancer: a study of 240 cases. American journal of clinical pathology 2012, 137, 918–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khayeka-Wandabwa, C.; Ma, X.; Jia, Y.; Bureik, M. Monitoring of autoantibodies against CYP4Z1 in patients with colon, ovarian, or prostate cancer. Immunobiology 2022, 227, 152174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nunna, V.; Jalal, N.; Bureik, M. Anti-CYP4Z1 autoantibodies detected in breast cancer patients. Cell Mol Immunol 2017, 14, 572–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osanai, M.; Sawada, N.; Lee, G.H. Oncogenic and cell survival properties of the retinoic acid metabolizing enzyme, CYP26A1. Oncogene 2010, 29, 1135–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevison, F.; Jing, J.; Tripathy, S.; Isoherranen, N. Chapter Eleven - Role of Retinoic Acid-Metabolizing Cytochrome P450s, CYP26, in Inflammation and Cancer. In Advances in Pharmacology, Hardwick, J.P., Ed.; Academic Press: 2015; Volume 74, pp. 373–412.

- Foti, R.S.; Isoherranen, N.; Zelter, A.; Dickmann, L.J.; Buttrick, B.R.; Diaz, P.; Douguet, D. Identification of Tazarotenic Acid as the First Xenobiotic Substrate of Human Retinoic Acid Hydroxylase CYP26A1 and CYP26B1. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 2016, 357, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaluzhskiy, L.; Ershov, P.; Yablokov, E.; Shkel, T.; Grabovec, I.; Mezentsev, Y.; Gnedenko, O.; Usanov, S.; Shabunya, P.; Fatykhava, S.; et al. Human Lanosterol 14-Alpha Demethylase (CYP51A1) Is a Putative Target for Natural Flavonoid Luteolin 7,3'-Disulfate. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hargrove, T.Y.; Friggeri, L.; Wawrzak, Z.; Sivakumaran, S.; Yazlovitskaya, E.M.; Hiebert, S.W.; Guengerich, F.P.; Waterman, M.R.; Lepesheva, G.I. Human sterol 14α-demethylase as a target for anticancer chemotherapy: towards structure-aided drug design1. Journal of Lipid Research 2016, 57, 1552–1563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Board, P.D.Q.C.G.E. Genetics of Breast and Gynecologic Cancers (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. In PDQ Cancer Information Summaries; National Cancer Institute (US): Bethesda (MD), 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Aktas, D.; Guney, I.; Alikasifoglu, M.; Yüce, K.; Tuncbilek, E.; Ayhan, A. CYP1A1 gene polymorphism and risk of epithelial ovarian neoplasm. Gynecologic oncology 2002, 86, 124–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heubner, M.; Wimberger, P.; Riemann, K.; Kasimir-Bauer, S.; Otterbach, F.; Kimmig, R.; Siffert, W. The CYP1A1 Ile462Val polymorphism and platinum resistance of epithelial ovarian neoplasms. Oncology research 2010, 18, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, M.T.; McDuffie, K.; Kolonel, L.N.; Terada, K.; Donlon, T.A.; Wilkens, L.R.; Guo, C.; Le Marchand, L. Case-control study of ovarian cancer and polymorphisms in genes involved in catecholestrogen formation and metabolism. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 2001, 10, 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Seremak-Mrozikiewicz, A.; Drews, K.; Semczuk, A.; Jakowicki, J.A.; Mrozikiewicz, P.M. CYP1A1 alleles in female genital cancers in the Polish population. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology 2005, 118, 246–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sergentanis, T.N.; Economopoulos, K.P.; Choussein, S.; Vlahos, N.F. Cytochrome P450 1A1 (CYP1A1) gene polymorphisms and ovarian cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Molecular biology reports 2012, 39, 9921–9930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, M.T.; McDuffie, K.; Kolonel, L.N.; Terada, K.; Donlon, T.A.; Wilkens, L.R.; Guo, C.; Le Marchand, L. Case-control study of ovarian cancer and polymorphisms in genes involved in catecholestrogen formation and metabolism. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 2001, 10, 209–216. [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, M.T.; Tung, K.-H.; McDuffie, K.; Wilkens, L.R.; Donlon, T.A. Association of caffeine intake and CYP1A2 genotype with ovarian cancer. Nutrition and cancer 2003, 46, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sellers, T.A.; Schildkraut, J.M.; Pankratz, V.S.; Vierkant, R.A.; Fredericksen, Z.S.; Olson, J.E.; Cunningham, J.; Taylor, W.; Liebow, M.; McPherson, C.; et al. Estrogen bioactivation, genetic polymorphisms, and ovarian cancer. Cancer epidemiology, biomarkers & prevention : a publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology 2005, 14, 2536–2543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delort, L.; Chalabi, N.; Satih, S.; Rabiau, N.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Bignon, Y.J.; Bernard-Gallon, D.J. Association between genetic polymorphisms and ovarian cancer risk. Anticancer research 2008, 28, 3079–3081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Gajjar, K.; Owens, G.; Sperrin, M.; Martin-Hirsch, P.L.; Martin, F.L. Cytochrome P1B1 (CYP1B1) polymorphisms and ovarian cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Toxicology 2012, 302, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Feng, L.; Lou, M.; Deng, X.; Liu, C.; Li, L. The ovarian carcinoma risk with the polymorphisms of CYP1B1 come from the positive selection. Am J Transl Res 2021, 13, 4322–4341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pearce, C.L.; Near, A.M.; Van Den Berg, D.J.; Ramus, S.J.; Gentry-Maharaj, A.; Menon, U.; Gayther, S.A.; Anderson, A.R.; Edlund, C.K.; Wu, A.H.; et al. Validating genetic risk associations for ovarian cancer through the international Ovarian Cancer Association Consortium. British Journal of Cancer 2009, 100, 412–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assis, J.; Pereira, D.; Gomes, M.; Marques, D.; Marques, I.; Nogueira, A.; Catarino, R.; Medeiros, R. Influence of CYP3A4 genotypes in the outcome of serous ovarian cancer patients treated with first-line chemotherapy: implication of a CYP3A4 activity profile. Int J Clin Exp Med 2013, 6, 552–561. [Google Scholar]

- Spurdle, A.B.; Goodwin, B.; Hodgson, E.; Hopper, J.L.; Chen, X.; Purdie, D.M.; McCredie, M.R.; Giles, G.G.; Chenevix-Trench, G.; Liddle, C. The CYP3A4*1B polymorphism has no functional significance and is not associated with risk of breast or ovarian cancer. Pharmacogenetics 2002, 12, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FISZER-MALISZEWSKA, Ł.; ŁACZMAŃSKI, Ł.; DOLIŃSKA, A.; JAGAS, M.; KOŁODZIEJSKA, E.; JANKOWSKA, M.; KUŚNIERCZYK, P. Polymorphisms of <em>ABCB1, CYP3A4</em> and <em>CYP3A5</em> Genes in Ovarian Cancer and Treatment Response in Poles. Anticancer research 2018, 38, 1455–1459. [Google Scholar]

- Spurdle, A.B.; Chen, X.; Abbazadegan, M.; Martin, N.; Khoo, S.K.; Hurst, T.; Ward, B.; Webb, P.M.; Chenevix-Trench, G. CYP17 promotor polymorphism and ovarian cancer risk. Int J Cancer 2000, 86, 436–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gowtham Kumar, G.; Paul, S.F.D.; Molia, C.; Manickavasagam, M.; Ramya, R.; Usha Rani, G.; Ganesan, N.; Andrea Mary, F. The association between CYP17A1, CYP19A1, and HSD17B1 gene polymorphisms of estrogen synthesis pathway and ovarian cancer predisposition. Meta Gene 2022, 31, 100985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotsopoulos, J.; Vitonis, A.F.; Terry, K.L.; De Vivo, I.; Cramer, D.W.; Hankinson, S.E.; Tworoger, S.S. Coffee intake, variants in genes involved in caffeine metabolism, and the risk of epithelial ovarian cancer. Cancer causes & control : CCC 2009, 20, 335–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyob, A.N.; Al-Badran, A.I.; Abood, R.A. Association of TTTA polymorphism in CYP19 gene with endometrial and ovarian cancers risk in Basrah. Gene Reports 2019, 16, 100453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, E.J.; Thomas, N.A.; Palmer, K.; Dawson, E.; Englefield, P.; Campbell, I.G. Refinement of an ovarian cancer tumour suppressor gene locus on chromosome arm 22q and mutation analysis of CYP2D6, SREBP2 and NAGA. International Journal of Cancer 2000, 87, 798–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarhanis, P.; Redman, C.; Perrett, C.; Brannigan, K.; Clayton, R.N.; Hand, P.; Musgrove, C.; Suarez, V.; Jones, P.; Fryer, A.A.; et al. Epithelial ovarian cancer: influence of polymorphism at the glutathione S-transferase GSTM1 and GSTT1 loci on p53 expression. British Journal of Cancer 1996, 74, 1757–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peethambaram, P.; Fridley, B.L.; Vierkant, R.A.; Larson, M.C.; Kalli, K.R.; Elliott, E.A.; Oberg, A.L.; White, K.L.; Rider, D.N.; Keeney, G.L.; et al. Polymorphisms in ABCB1 and ERCC2 associated with ovarian cancer outcome. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet 2011, 2, 185–195. [Google Scholar]

- Khrunin, A.V.; Ivanova, F.G.; Moiseev, A.A.; Gorbunova, V.A.; Limborskaia, S.A. [CYP2E1 gene polymorphism and ovarian cancer risk in the Yakut population]. Genetika 2011, 47, 1686–1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadyen, M.C.; McLeod, H.L.; Jackson, F.C.; Melvin, W.T.; Doehmer, J.; Murray, G.I. Cytochrome P450 CYP1B1 protein expression: a novel mechanism of anticancer drug resistance. Biochemical pharmacology 2001, 62, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Feng, L.; Lou, M.; Deng, X.; Liu, C.; Li, L. The ovarian carcinoma risk with the polymorphisms of CYP1B1 come from the positive selection. Am J Transl Res 2021, 13, 4322–4341. [Google Scholar]

- Gagno, S.; Bartoletti, M.; Romualdi, C.; Poletto, E.; Scalone, S.; Sorio, R.; Zanchetta, M.; De Mattia, E.; Roncato, R.; Cecchin, E.; et al. Pharmacogenetic score predicts overall survival, progression-free survival and platinum sensitivity in ovarian cancer. Pharmacogenomics 2020, 21, 995–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assis, J.; Pereira, D.; Gomes, M.; Marques, D.; Marques, I.; Nogueira, A.; Catarino, R.; Medeiros, R. Influence of CYP3A4 genotypes in the outcome of serous ovarian cancer patients treated with first-line chemotherapy: implication of a CYP3A4 activity profile. Int J Clin Exp Med 2013, 6, 552–561. [Google Scholar]

- Gréen, H.; Söderkvist, P.; Rosenberg, P.; Mirghani, R.A.; Rymark, P.; Lundqvist, E.A.; Peterson, C. Pharmacogenetic studies of Paclitaxel in the treatment of ovarian cancer. Basic & clinical pharmacology & toxicology 2009, 104, 130–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, M.; Fujiki, Y.; Kyo, S.; Kanaya, T.; Nakamura, M.; Maida, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Inoue, M.; Yokoi, T. Pharmacokinetics of paclitaxel in ovarian cancer patients and genetic polymorphisms of CYP2C8, CYP3A4, and MDR1. Journal of clinical pharmacology 2005, 45, 674–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergmann, T.K.; Brasch-Andersen, C.; Gréen, H.; Mirza, M.; Pedersen, R.S.; Nielsen, F.; Skougaard, K.; Wihl, J.; Keldsen, N.; Damkier, P.; et al. Impact of CYP2C8*3 on paclitaxel clearance: a population pharmacokinetic and pharmacogenomic study in 93 patients with ovarian cancer. The Pharmacogenomics Journal 2011, 11, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gréen, H.; Khan, M.S.; Jakobsen-Falk, I.; Åvall-Lundqvist, E.; Peterson, C. Impact of CYP3A5*3 and CYP2C8-HapC on paclitaxel/carboplatin-induced myelosuppression in patients with ovarian cancer. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences 2011, 100, 4205–4209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Lv, Q.L.; Guo, Y.; Cheng, L.; Wu, N.Y.; Qin, C.Z.; Zhou, H.H. Genetic variation of CYP3A5 influences paclitaxel/carboplatin-induced toxicity in Chinese epithelial ovarian cancer patients. Journal of clinical pharmacology 2016, 56, 349–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klyushova, L.S.; Perepechaeva, M.L.; Grishanova, A.Y. The Role of CYP3A in Health and Disease. Biomedicines 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, T.; Wang, X.; Zhu, G.; Han, C.; Su, H.; Liao, X.; Yang, C.; Qin, W.; Huang, K.; Peng, T. The prognostic value of differentially expressed CYP3A subfamily members for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer management and research 2018, 10, 1713–1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFadyen, M.C.E.; Melvin, W.T.; Murray, G.I. Cytochrome P450 enzymes: Novel options for cancer therapeutics. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics 2004, 3, 363–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanev, S.; Stoyanova, T. Manipulating cytochrome P450 enzymes: new perspectives for cancer treatment. Biomedical Reviews 2018, 28, 120–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikstacka, R.; Dutkiewicz, Z. New perspectives of CYP1B1 inhibitors in the light of molecular studies. Processes 2021, 9, 817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capper, C.P.; Rae, J.M.; Auchus, R.J. The metabolism, analysis, and targeting of steroid hormones in breast and prostate cancer. Hormones and cancer 2016, 7, 149–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, W.R.; Hay, M.P. Targeting hypoxia in cancer therapy. Nature reviews. Cancer 2011, 11, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albertella, M.R.; Loadman, P.M.; Jones, P.H.; Phillips, R.M.; Rampling, R.; Burnet, N.; Alcock, C.; Anthoney, A.; Vjaters, E.; Dunk, C.R. Hypoxia-selective targeting by the bioreductive prodrug AQ4N in patients with solid tumors: results of a phase I study. Clinical Cancer Research 2008, 14, 1096–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lánczky, A.; Győrffy, B. Web-Based Survival Analysis Tool Tailored for Medical Research (KMplot): Development and Implementation. Journal of medical Internet research 2021, 23, e27633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).