1. Introduction

The solar cell industry not only falls within the realm of renewable energy but also stands as a globally competitive “green energy” sector. Patents serve as a pivotal cornerstone in driving the advancement of this industry [

1,

2]. Within the context of business operations, intellectual property rights play a crucial role in fostering entrepreneurship and act as a vital mechanism for preserving corporate R&D achievements while facilitating sustainable corporate growth [

3]. Patents, from a defensive standpoint, protect creators’ intellectual property rights from potential infringement by others. On the market front, the exclusive patent rights held by each manufacturer throughout the supply chain establish barriers to entry, thereby constraining competitive pressures. It’s important to note that while the active pursuit of “defensive patents,” the utilization of patents to create robust barriers against market entry, and the formation of complex “patent thickets” for countering rivals and seeking compensation through infringement litigation can be viable strategies, they also have the potential to hinder industrial progress and societal advancement [

4]. Regarding innovation, patent licensing or the pursuit of complementary patents offers patent holders avenues for financial gains [

5]. Taiwan’s photovoltaic industry boasts well-established upstream, midstream, and downstream industrial chains. In this context, the aggregation of patents from diverse manufacturers within the supply chain becomes particularly crucial in fostering collective market value derived from patents.

The establishment of a patent pool primarily addresses the challenge posed by blocking patents [

6]. Blocking patents emerge due to the continuous generation of new innovations that enhance the original patented technology during research and development (R&D) and innovation processes. Without new patents to cover these enhancements, the progression of innovation could be hindered, leading to these new patents being relegated to a secondary status known as subservient patents [

6]. The concept of pre-emptive patenting involves filing a patent application with the primary intention of obstructing the grant of other patents, ultimately resulting in the creation of blocking patents [

7]. Upon the commercialization of a new patent, it often finds itself infringing on the original patent, leading to a situation where the original patent effectively obstructs the implementation of the subservient patent. As a result, effectively deploying the new patent in the market becomes challenging [

3]. This phenomenon of patent safeguarding is considered an inevitable and common aspect of business operations.

Various approaches for reviewing previous research can be identified as follows:

Legal Protection Concept: Ho [

4] delves into the concept of horizontal competition among members of patent alliances, potentially leading to anticompetitive effects. His work primarily investigates legal disputes arising from patent alliances. Guellec, Martinez, & Zuniga [

7] contribute by introducing a methodology to identify pre-emptive patent applications, focusing on the practice of pre-emptive patenting. This involves strategically designing patents to create blocking patents that hinder others from filing patents.

Patent Layout Concept: Within the context of patent layout, Crescenzi, Dyèvre & Neffke [

8] emphasize that engagement of foreign technology leaders in technical alliances and collaborations with less developed local companies could hinder the generation of new patents. Di et al. [

9] employ network analysis to reveal a distinct “core-periphery” pattern in the global innovation network. Their findings present a quadrilateral structure with vertices represented by “US, Japan, Europe, and China,” providing a visualized map of the global patent layout and its evolutionary trajectory.

Patent Portfolio Management Concept: Conegundes De Jesus & Salerno [

10] contribute by elucidating the evolution and trends in patent portfolio management, presenting a conceptual framework for the same. Hoskisson and Yiu [

5], along with Sun and Xu [

11], delve into research on complementary patents, proposing that integrating such patents can enhance technological advancement within an enterprise’s research and development (R&D) process. Applying complementary technology to allied enterprises can further amplify benefits. Sun and Xu’s [

11] methodology calculates the average complementarity between a given patent and all patents within the same company, facilitating the identification of desired complementary enterprises. Granstrand [

12] underscores the necessity of employing diverse complementary intellectual property rights for distinct innovative components, suggesting six patent strategy models that hold instructive value for this study.

Drawing on an in-depth analysis of relevant literature, the central theme revolves around the legal protection of patents, reinforced by patent deployment and the synergy of patent complementarity. A research gap is identified in the limited exploration of methodologies for aggregating patents from supply chain manufacturers to collectively cultivate patent market value. This gap is particularly pronounced within small and medium-sized enterprises grappling with resource constraints in their enterprise supply chains. For these entities, unlocking their patent portfolios could potentially yield significant benefits, enhancing patent utilization and bolstering operational performance. Hence, the core of this research centers on formulating a comprehensive business strategy framework that spans a range of patent projects. The aim is to enable each enterprise along the supply chain to leverage its patent reserves and thus generate patent market value.

The primary focus of this research lies in devising a business strategy framework that facilitates Project-based licensing within patent consortia. The overarching goal is to collaboratively and sustainably enhance the market value of patents. To achieve this, the study delves into an analysis of solar cell patents, coupled with the integration of patents held by supply chain manufacturers. The research employs the WIPS Global Patent database as its dataset, analyzing both abstracts and complete patent texts from the solar cell industry to identify projects with the highest patent density. Subsequently, through focus group discussions, the feasibility of implementing a business strategy involving supply chain enterprise patent alliances is explored. Finally, the research recommends adopting a business strategy framework for project-based patent consortium authorization, tailored particularly for projects exhibiting the highest patent frequency. It is important to note that the solar cell manufacturing industry within the scope of this study encompasses manufacturers of solar silicon wafers, batteries, and modules [

13]. The proposed business strategy framework takes the form of a conceptual construct with defined business objectives, readily translatable into market-driven profits.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Expectancy theory

Applying the expectancy theory to the domain of patents involves evaluating the anticipated value inherent in patents. Hsueh & Jheng [

14] categorize this patent value into two distinct dimensions: patent litigation value and patent commercialization value. The patent litigation value reflects the expectation that patents hold value by enabling legal actions against potential infringers and deterring patent infringements. On the other hand, patent commercialization value signifies the potential for patents to be commercialized and applied in practical contexts [

14]. Realizing these dual aspects of patent value requires thorough analysis, strategic arrangement, and skillful deployment of patents. Considering market demand, a patent licensing resource that reduces R&D costs and enhances research efforts is viewed as a catalyst for innovation, particularly sought after by small and medium-sized enterprises, startups, and innovators.

Aligned with the expectations linked to patent value, the development of a patent strategy by an enterprise underscores the importance of strategic decision-making. Robinson, Jr. and Pearce [

15] further elaborate that strategic decision-making encompasses six dimensions: strategic matters necessitate top-management decisions, strategic matters entail significant allocation of firm resources, strategic matters have a lasting impact on the firm’s future prosperity, strategic matters have a forward-looking orientation, strategic matters often have multifunctional or multi-business implications, and strategic matters require an assessment of the firm’s external environment. A strategic management framework becomes essential in fulfilling the company’s goals of extracting commercial value from patents.

2.2. Patent pool

The Patent Pool model serves as a strategic approach within patent operations, designed to efficiently secure authorization and reduce manufacturing costs in response to the complex nature of industrial technology. Often, the production of a single product requires the incorporation of various existing patents [

6]. Patent pooling can be succinctly described as an arrangement among parties holding intellectual property from different projects, either directly or through the authorization of a third party [

16]. A critical implication of patent pooling is that patent holders collectively relinquish their exclusive rights associated with patents to consolidate their patents under a single entity [

17]. This concept is further emphasized by Andewelt [

17], who suggests that patent pooling involves the aggregation of patents.

Regarding aggregation, patent holders can assign or authorize their patent rights to an independent legal entity or come together as members within a patent pool. Subsequently, the independent legal entity or the pool members collectively authorize the accumulated patent portfolio to authorized parties as a unified package. When a patent pool consists of complementary patents, the entities within the pool do not engage in competitive rivalry, thus avoiding the risk of participating in joint anti-competitive behavior [

6,

16].

The Antitrust Guidelines for the Licensing of Intellectual Property [

16], jointly published by the Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission in 1995, elaborate on circumstances within patent alliances that promote competition. These circumstances include:

Integrating complementary patents

Resolving patent blocking situations (clearly defined blocking positions)

Reducing transaction costs

Mitigating the need for expensive patent infringement litigation

Facilitating technology utilization

In a subsequent update in 2017, the DOJ and FTC’s antitrust guidance on IP licensing further emphasizes that IP licensing allows firms to combine complementary factors of production, often leading to pro-competitive outcomes. As stated, “the Agencies recognize that intellectual property licensing allows firms to combine complementary factors of production and is generally competitive” [

18]. Patent pools have garnered increasing attention in recent times.

2.3. Strategy of Project-Based Authorization

Within the realm of strategic patent deployment, a significant approach is encapsulated in strategic patents, representing a pivotal avenue for strategic utilization [

12]. The concept of project-based licensing draws inspiration from the domain of complementary patents, as outlined by Sun and Xu [

11]. This involves harnessing a patent alliance database formed through complementary patents, followed by tailoring project-specific authorization to enterprises or individuals seeking to incorporate authorized patents within their product or service research and development endeavors. From a performance attribute perspective, patents encompass four key attributes: energy, hardware cost, time, and space [

1]. Therefore, when devising strategies for project-based licensing, the allocation of licenses over time, commonly referred to as a year-by-year licensing method, can be a pertinent consideration for the “time” attribute.

When contemplating the adoption of the patent joint venture model to meet the needs of small and medium-sized enterprises, an essential consideration lies in the expansion of demand and concurrently opening avenues on the supply side. Incentivizing small and medium-sized enterprises and innovators to invest in pioneering R&D, mitigate R&D costs, and overcome barriers to accessing pre-existing patents in the research and development continuum can be effectively achieved through the utilization of R&D project-based licensing methods. This strategy, known as Project-based licensing, entails employing a patent licensing approach that centers on individual projects as the unit of calculation. This is tailored to the requisites of enterprises or individual innovators embarking on novel product or service research and development initiatives.

3. Methodology

3.1. Literature Analysis

This phase involved an exploration of patent alliances within the Solar Cell Industry, along with relevant literature. Additionally, a preliminary business strategy framework for patent alliance operations was formulated to serve as the foundation for subsequent focus group discussions.

3.2. Focus Group Methodology

The focus group method encompassed two distinct meetings. Considering the solar photovoltaic industry primarily comprises the “solar cell manufacturing industry,” which also encompasses sectors like “other electric equipment and supplies manufacturing,” “engineering services and related technical consulting,” and “electric power supply” [

13]. This industry is categorized into upstream, midstream, and downstream segments. The upstream segment includes silicon materials and wafers from a single company, while the midstream involves 17 companies manufacturing solar cells and 18 companies producing solar photovoltaic modules. The downstream segment consists of 58 companies engaged in producing inverters and components, along with 245 companies focusing on system engineering. Recognizing the interconnectedness of the solar cell manufacturing and photovoltaic industries, a total of 14 managerial-level representatives from these segments were invited to partake in discussions (outlined in

Table 1). The focal point of these discussions was the business strategy framework proposed in this research, with a specific focus on assessing its feasibility. The procedural approach adhered to the methodology outlined by Bates [

19].

3.3. Patent Analysis

The primary objective of conducting an analysis of patent abstracts and full texts within the solar energy industry is to establish the groundwork for the development of a business strategy framework, building upon the findings from the literature analysis phase. During the patent analysis stage, the process adheres to the structure of the International Patent Classification (IPC). The IPC organizes patents into a hierarchical framework consisting of five levels: Section, Class, Subclass, Main Group, and Group. Specifically, the IPC Sections categorize patent documents into eight distinct parts: A (Human necessities), B (Performing operations; transporting), C (Chemistry, metallurgy), D (Textiles; paper), E (Fixed constructions), F (Mechanical engineering; lighting; heating; weapons; blasting), G (Physics), and H (Electricity) [

20].

Hence, regarding the selection of the target database and the chosen analysis indicators, this study opted for the WIPS GLOBAL SmartCloud database as the retrieval platform. It employed Comparative Analysis, classification code analysis, and Activity index analysis. The retrieval approach involved gathering full-text patents that fall within the vertical industries of the solar cell sector’s upstream, midstream, and downstream. The retrieval timeframe spanned a decade, from February 23, 2013, to February 23, 2023. Full-text patents were acquired for subsequent analysis. Ultimately, a detailed investigation was undertaken on patents related to Solar cells within the midstream of the solar energy industry.

4. Results & Discussion

4.1. Results

4.1.1. Overall Patent Landscape in the Solar Cell Industry

Utilizing the product classification names corresponding to the vertical segments of the solar cell industry—upstream, midstream, and downstream—as search criteria, patent counts for each specific product or service were extracted and consolidated in

Table 1. Notably, the Solar PV system, Silicon materials, Silicon wafer materials, and Solar PV power converter product categories emerged with the highest patent counts among the analyzed segments.

Table 2.

Number of Patents in the Solar Energy Industry in the Past 10 Years.

Table 2.

Number of Patents in the Solar Energy Industry in the Past 10 Years.

| Retrieve Keywords Silicon materials, Silicon wafer materials, Solar cell, Solar cell module, Thin film solar cell module, Dye-sensitized solar cell, Concentrating solar cell module, Solar PV system, Solar PV power, converter, Solar PV access/supplier |

|---|

| |

|

Number of patents |

| |

Upstream |

Silicon materials |

31,212,755 |

| |

|

Silicon wafer materials |

31,382,887 |

| |

Midstream |

Solar cell |

10,438,088 |

| |

|

Solar cell module |

20,007,918 |

| |

|

Thin film solar cell module |

27,580,647 |

| |

|

Dye-sensitized solar cell |

10,438,359 |

| |

|

Concentrating solar cell module |

25,084,359 |

| |

Downstream |

Solar PV system |

31,508,226 |

| |

|

Solar PV power converter |

31,349,698 |

| |

|

Solar PV access/supplier |

2,075,363 |

| Retrieval Period |

20130223~20230223 |

|

| Retrieval Database |

WIPS Global database |

|

| Retrieval Country |

US, EP, PCT, CN, JP, KR,CA, AU, DE, GB, FR,IT, TW |

4.1.2. Analysis of Solar Cell Patents

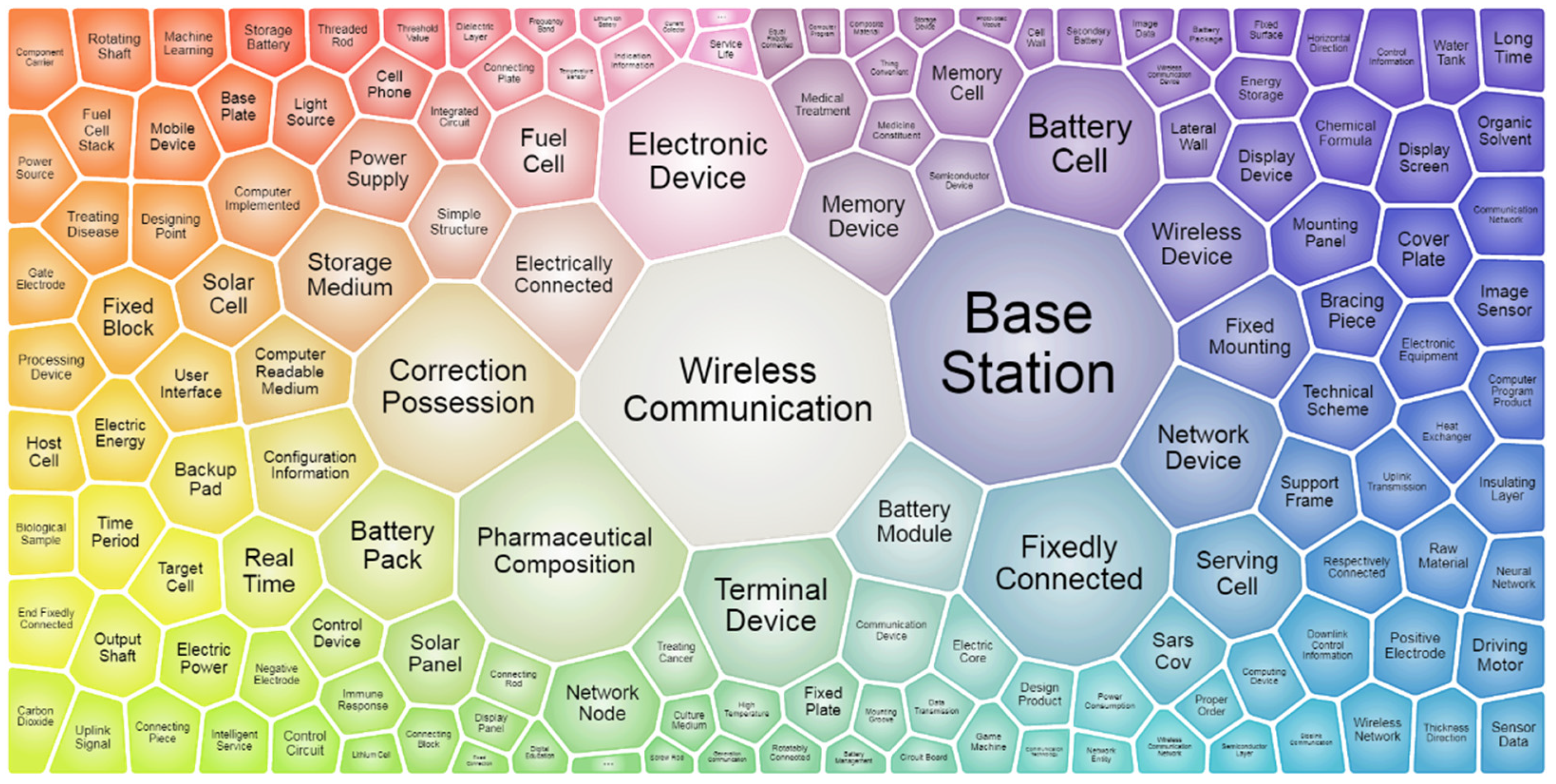

A dataset comprising solar cell patents from the past 10 years was compiled, resulting in a total of 221,078,300 patents (see

Table 1). Upon scrutinizing the abstracts of these solar cell patents, it was revealed that the two categories with the most substantial global patent counts are “Wireless Communication” and “Base Station.” The comprehensive distribution of patents is graphically depicted in

Figure 1 as presented below.

Upon a thorough examination of the intricate solar cell patents, it is evident that the foremost fifteen solar cell patent projects, amassing a considerable total of 5,579 patents, collectively encompass a comprehensive tally of 3,297 patent documents. This detailed information is succinctly presented in

Table 3 below.

- A.

Analysis of Classification Codes

Further delving into the realm of solar cell patents through the lens of classification codes unveils a comprehensive picture of the quantity and proportional distribution of patents within each classification. The breakdown is delineated as follows:

A (Human necessities): 17,485 (18%)

B (Performing operations, Transporting): 10,746 (11%)

C (Chemistry, Metallurgy): 15,961 (16%)

D (Textiles, Paper): 436 (0%)

E (Fixed Constructions): 1,954 (2%)

F (Mechanical engineering, Lighting, Heating, Weapons, Blasting): 3,736 (4%)

G (Physics): 19,922 (20%)

H (Electricity): 29,088 (29%)

The comprehensive statistical overview of the top 15 countries boasting the highest solar cell patent counts is meticulously detailed in

Table 4 below.

- B.

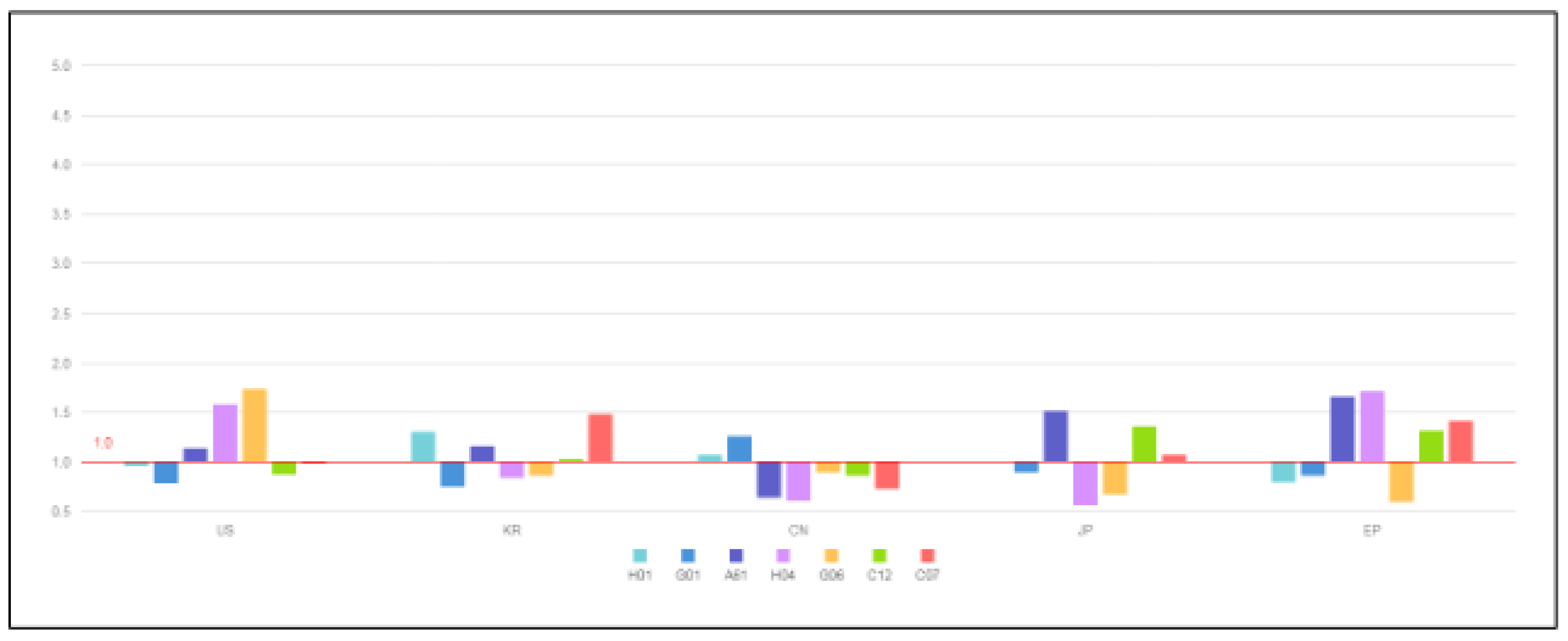

Analysis of Activity Index (by Country)

The Activity Index (AI) discussed here pertains to the proportional concentration of patents held by applicants (countries) within specific technological domains. AI is determined by dividing the Number of specific applicants (countries) in a given technology field by the total number of patents within that same technology field. In essence, AI can be expressed as the Total number of patents held by a particular applicant (country) divided by the overall Total number of patents. Hence, AI signifies a relative ratio and doesn’t directly indicate patent quantity.

AI values greater than 1 denote a higher relative concentration of patents owned by the applicant (country) in the specific technological realm. Conversely, AI values less than 1 suggest a lower relative concentration. As exemplified in

Figure 2 below, using the United States as a case study, technological categories such as A61 (Human necessities), H04 (Electricity), and G06 (Physics) exhibit AI values greater than 1. Japan, on the other hand, demonstrates significant AI concentration in the A61 category.

Please refer to

Figure 2 for a visual representation of AI values greater than 1 in specific technological categories across different countries. The explanation accompanying the figure offers insights into the calculation and interpretation of AI values.

Please find the distribution of Activity Index values greater than 1 for solar cell patents in specific fields among major countries presented in

Table 5 and

Table 6 below. This table showcases the patent strengths of various countries within the solar cell industry, highlighting their expertise in specific fields as outlined:

Refer to

Table 5 for a comprehensive breakdown of Activity Index values greater than 1 for solar cell patents in specific fields among major countries.

4.2. Discussion

4.2.1. Feasibility of Establishing a Patent Alliance Information Platform

The outcomes of the patent analysis underscore the significance of focusing on the top fifteen solar cell patent projects, which exhibit substantial patent volume and indicative research and development demand within the supply chain. Consequently, opting to target these patents, characterized by considerable market economic scale, for the patent alliance information platform increases the likelihood of achieving successful outcomes. Classification code analysis indicates that patents are predominantly distributed across three categories: H (Electricity) with 29,088 (29%), G (Physics) with 19,922 (20%), and A (Human Necessities) with 17,485 (18%). Similarly, the activity index (country) analysis underscores distinct patent advantages among different countries within the solar cell industry. Thus, the establishment of specialized patent alliance information platforms for each country or region, tailored to their unique supply chain requirements, emerges as a strategic proposition. By adhering to the principle of territoriality in patent application and scope, patent rights holders can choose to participate in local or national patent pools as high-value contributors. This approach enhances the contribution of patents to industries and society, amplifies individual patent capital gains through authorization, and activates intellectual creations, consistent with Conegundes De Jesus & Salerno’s [

10] perspectives on patent portfolio management frameworks.

4.2.2. Enhancing Patent Commercialization Value through Project-based Authorization

The commercial framework of the patent alliance information platform, underpinned by a project-based authorization approach, rests on the collective generation of market value. This approach, in alignment with Bridoux, Coeurderoy, & Durand’s [

22] concept of “cooperative and nonhierarchical collaboration,” holds the potential for comprehensive benefits. Insights from focus groups further emphasize that small and medium-sized enterprises, despite harboring strong innovation and research targets, often grapple with financial constraints and resource inadequacy. Additionally, the hindrance imposed by pre-existing restrictive patents curbs their commitment to research and development, impeding innovation outputs and inhibiting societal and industrial advancement. In response, adopting a project-based authorization model for research and development, tailored to specific projects, caters to market needs. This perspective echoes Hsueh & Jheng’s [

14] discourse on patents carrying commercialization and application value. Thus, the implementation of a project-based approach to patent research and development authorization, customized for individual research endeavors, aligns with market demands and can be operationalized efficiently. This view aligns with the operating efficiency advocated by focus group experts. Such an organization could potentially be managed by academic institutions or industry associations, akin to a Federation of Industry.

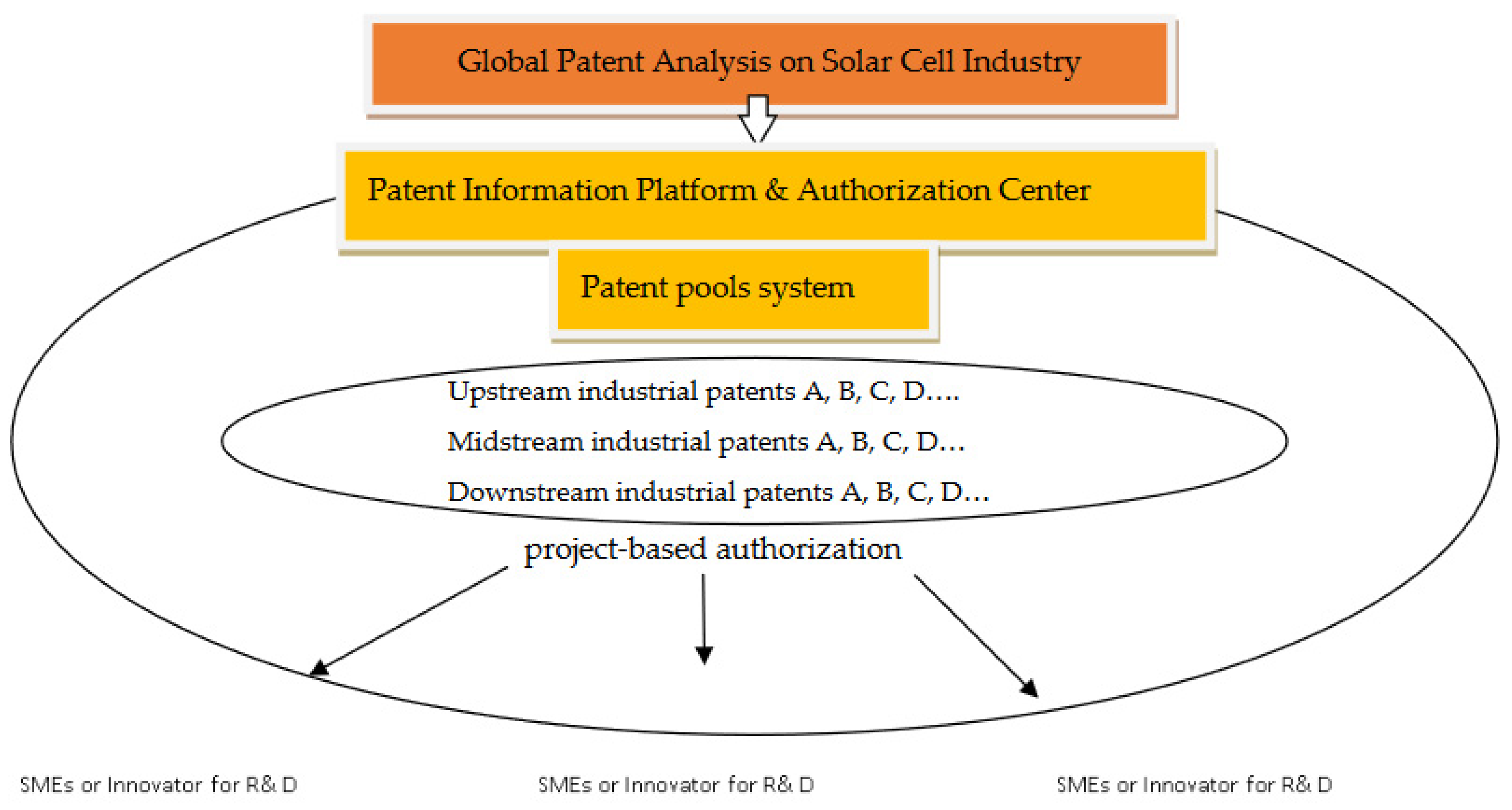

4.2.3. Sustainable Technological Development through the Project-based Authorization Business Strategy Framework

The synthesis of the proposed business strategy framework integrates patent analysis, patent pool systems, and project-based operational mechanisms through patent information platforms and authorization systems. Patent authorizations are adaptable to two fundamental formats based on recipient needs: individual authorizations for single patents and package-based authorizations tailored to the developmental requisites of research projects. This business strategy framework encapsulates the concepts of patent commercialization value as elucidated by Hsueh and Jheng [

14], alongside the effects of patent portfolio management highlighted by Hoskisson and Yiu [

5] and the principle of complementary patents presented by Sun and Xu [

11], as well as strategic entrepreneurship by Xin et al. [

24]. Translating the framework into operational mechanisms, the patent supply chain of product series encompassing Solar PV systems, Silicon materials, Silicon wafer materials, and Solar PV power converters can be effectively integrated, as depicted in

Figure 3 below.

5. Conclusion

This study is grounded in expectancy theory and aims to enhance the commercial value of patents for solar cell enterprises and their counterparts within the supply chain. The primary goal is to establish a comprehensive business strategy framework for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and aspiring innovators operating in the market. The study is driven by the context of limited resources and funding for innovative research and development, with the aim of effectively addressing these challenges. To achieve this, the study conducted an in-depth analysis of the solar cell industry, examining patents across its upstream, midstream, and downstream sectors. Additionally, a thorough patent analysis was conducted to gain insights into the current state of patent development within the solar cell industry.

The subsequent focus of the study was the creation of a patent pooling information platform in compliance with US antitrust regulations. By identifying the top 15 patent projects with significant market economic scale, these patents were chosen to be integrated into the patent alliance information platform. Leveraging a project-based authorization approach, these selected patents serve as the centerpiece of the patent pooling information platform, maximizing the market value derived from patents. The outcomes of the study cater to the needs and expectations of SMEs and enthusiastic innovators aiming to optimize their R&D expenditures. The resulting business strategy framework is designed to support R&D processes for SMEs within the supply chain and for individual innovators, offering streamlined access to comprehensive project packages and detailed piece-by-piece authorization mechanisms. This approach encourages innovation by building upon the achievements of predecessors in research and development, potentially facilitating successful innovations and underscoring the practicality of the research findings.

In terms of real-world application, the study’s findings lay the groundwork for establishing and operating patent information platforms and authorization centers across diverse industries. Through the incorporation of a patent pool system and the implementation of a project-based authorization mechanism, a commercially viable business model can be actualized, contributing to substantial commercial applicability. However, it’s important to acknowledge certain limitations of the study. The research does not delve into the specifics of negotiation with patentees to ensure equitable authorization within the operational context of the proposed framework. Similarly, the practical operational mechanics of the information platform are not explored in detail. Furthermore, the study does not explore how the benefits derived from reduced transaction costs within the patent pooling are reinvested into the broader community. Researchers with interest in these areas could potentially pursue further research to address these gaps.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.-M. Lee, J. S. Chen and C.-C. Chang; methodology, S.-M. Lee, J. S. Chen and C.-C. Chang; software, C. C. Chang; validation, S.-M. Lee, J. S. Chen and C.-C. Chang; formal analysis, S.-M. Lee, and C.-C. Chang; data curation, S.-M. Lee, J. S. Chen and C.-C. Chang; writing—original draft preparation, S.-M. Lee, and C.-C. Chang X.X.; writing—review and editing, J. S. Chen and C.-C. Chang.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Lunghwa University of Science and Technology for providing WIPS Global patent database.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chang, C. C. An IPA-embedded model for evaluating creativity curricula. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int 2014, 51, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, C. G., & Chang, C. C. Building professional competencies indices in the Solar Energy Industry for the engineering education curriculum. Int. J. Photoenergy 2014, 2014, 963291. [CrossRef]

- Dost, M., Badir, Y. F., Ali, Z., & Tariq, A. The impact of intellectual capital on innovation generation and adoption. J. Intellect Cap. 2016, 17, 675–695.

- Ho, J. A. W. Antitrust law issues on the patent pool. Fair Trade Quarterly 2003, 11, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Hoskisson, R. E. & Yiu, D. The dynamics of knowledge regimes: technology, culture and competitiveness in the USA and Japan. Asia Pacific J. Manag. 2003, 20, 283–286.

- Kuo, C. T. Patent pool and concerted action in Taiwan. Property and Economic Law Journal 2006, 7, 181–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guellec, D., Martinez, C., & Zuniga, P. Pre-emptive patenting: securing market exclusion and freedom of operation. Econ. Innov. New Technol. 2012, 21, 1–29. [CrossRef]

- Crescenzi, R., Dyèvreb, A., & Neffke, F. Innovation catalysts: How multinationals reshape the global geography of innovation. Economic Geography 2022, 98, 199–227. [CrossRef]

- Di, Y., Zhou, Y., Zhang, L., Indraprahasta, G. S., & Cao, J. Spatial pattern and evolution of global innovation network from 2000 to 2019: Global patent dataset perspective. Complexity 2022, 5912696. [CrossRef]

- Conegundes De Jesus, C. K., & Salerno, M. S. Patent portfolio management: literature review and a proposed model. Expert Opin Ther Pat 2018, 28, 505–516. [CrossRef]

- Sun, L., & Xu, W. Enterprise complementarity based on patent information. Enterprise complementarity based on patent information. Wirel Commun Mob Comput 2022, Article ID 5797285, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Granstrand, O. The economics and management of intellectual property: Towards intellectual capitalism. Cheltenham, 1999, UK: Edward Elgar.

- IDBMEA. 2023-2025 professional talent demand estimation survey of Solar Optoelectronics industry. 2022, chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://ws.ndc.gov.tw/001/administrator/18/relfile/6037/9319/370d52a6-745f-4712-9734-dd82ccb91634.

- Hsueh, C. C. & Jheng, Y. T., To explore the relationship among patent expected value, patent application motivation and patent portfolio: Based on the expectancy theory. Technological Management 2017, 22, 29–56.

- Robinson, Jr. R. B., & Pearce II, J. A. Formulation, implementation, and control of competitive strategy (Ninth Edi.). 2005, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc.

- DJFTC. Antitrust guidelines for the licensing of intellectual property. U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission. 2006. https://www.justice.gov/sites/default/files/atr/legacy/2006/04/27/0558.

- Andewelt, R. B. Analysis of patent pools under the Antitrust Laws’. Antitrust Law J. 1984, 53, 611. [Google Scholar]

- DJFTC. Antitrust guidelines for the licensing of intellectual property. U.S. Department of Justice and the Federal Trade Commission. 2017. https://www.ftc.gov/system/files/documents/public_statements/1049793/ip_guidelines_2017.

- Bates, B. R. Public culture and public understanding of genetics: a focus group study. Public Underst Sci 2005, 14, 47–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 20. IPO. IPC international patent classification query. Intellectual Property Office, Ministry of Economic Affairs, R.O.C. 2023a. https://topic.tipo.gov.tw/patents-tw/sp-ipcq-level-101.html.

- IPO. Patents. Intellectual Property Office, Ministry of Economic Affairs, Taiwan. 2023b. https://www.tipo.gov.tw/en/mp-2.

- Bridoux, F., Coeurderoy, R., & Durand, R. Heterogeneous motives and the collective creation of value. Acad Manage Rev 2011, 36. [CrossRef]

- Synergytek Consultancy, WIPS. Global Patent database, 2022.

- Xin, B., Zhang, W. T., Zhang, W., Lou, C. X., & Shee, H. K. Strategic Entrepreneurship and Sustainable Supply Chain Innovation from the Perspective of Collaborative Advantage. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12879. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).