1. Introduction

First introduced by Long and Matthews in 1995, minimally invasive spine surgery (MIS) nowadays is becoming more and more popular [

1]. C-arm free navigated MIS techniques offer a variety of advantages, such as, minimal soft tissue and muscle detachment, smaller incisions, reducing pain and infection rates, high precision, and reduced hospitalization [

2]. However, a learning curve is expected to be reached in order to obtain an optimal result [

3]. Radiation hazard is also an uprising phenomenon related to fluoroscopy-dependent techniques [

4]. Often, prolonged exposure to radiation after years of work can lead to perilous consequences such as malignancy [

5].

C-arm free navigated techniques can offer zero level radiation exposure to the operation room staff by performing an O-arm scan. Furthermore, implant misplacement can lead to vessel injury, neurological deterioration, secondary pain, and high revision rates [

6]. High-precision fixation is obtained using navigation systems that provide a 3D live image reconstruction during operation [

7]. Our study aims to feature the available techniques of MIS and demonstrate postoperative examples for each category.

2. Occiput-cervical spine

2.1. Anterior application

2.1.1. OPLL resection

With the anaesthetised patient on the Jackson frame, and the neck in adequate extension, Initially a classic Smith-Robinson approach is performed to the appropriate cervical levels. After the Caspar pin retractor is placed and distraction acheived, a special adaptor is used for the placement of the reference frame on the retractor, following an O-arm scan, which offers 3D reconstructed images (

Figure 1A). The accuracy can be confirmed by checking at least 3 different anatomical surfaces. In any doubt, a second scan is strongly recommended. During the next surgical step, discectomies are performed at the superior and inferior disc segments. A navigated high-speed burr is used for bone spur resection in anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) or anterior cervical corpectomy and fusion (ACCF). It starts medially to the uncovertebral joints bilaterally in width and to the posterior cortex in-depth. As the anterior approach during decompression is more demanding than posterior due to the anatomical structures, a navigated pin pointer enables us to confirm the location when needed. The posterior wall of vertebral body can be easily removed by Kerrison rongeurs or floating technique. As inadequate decompression can lead to poor postoperative results, the cage position and the level of decompression can be confirmed by a new O-arm scan.

2.2. Posterior application

2.2.1. Posterior Fossa Decompression for Chiari Malformation

The surgical technique starts with an approximate skin incision of 7 cm from the greater occipital protuberance down to C2 spinous process, followed by subperiosteal detachment of dorsal cervical muscles from linea alba, spinous process and C2 lamina to avoid excessive bleeding. The most convenient point used for reference frame attachment for O-arm scanning is C2 spinous process. Next, by use of a high-speed burr the C1 posterior arch is resected. In some cases, when severe tonsillar herniation exists, we advise for C2 lamina resection. Excellent knowledge of anatomy is needed to avoid vertebral artery injury. Preoperatively, anatomical variations should also be considered. Thirdly, navigation assisted craniotomy is performed. Usually, 3cm peripheric to foramen magnum is considered adequate. The merit of navigation is the ability to verify the exact bone width and location of the foramen ma witgnum to avoid intraoperative complications. During the last step, duroplasty following ultrasonic monitor verification is performed. In case of inadequate decompression, we recommend extension of bone resection or duroplasty by use of artificial dura.

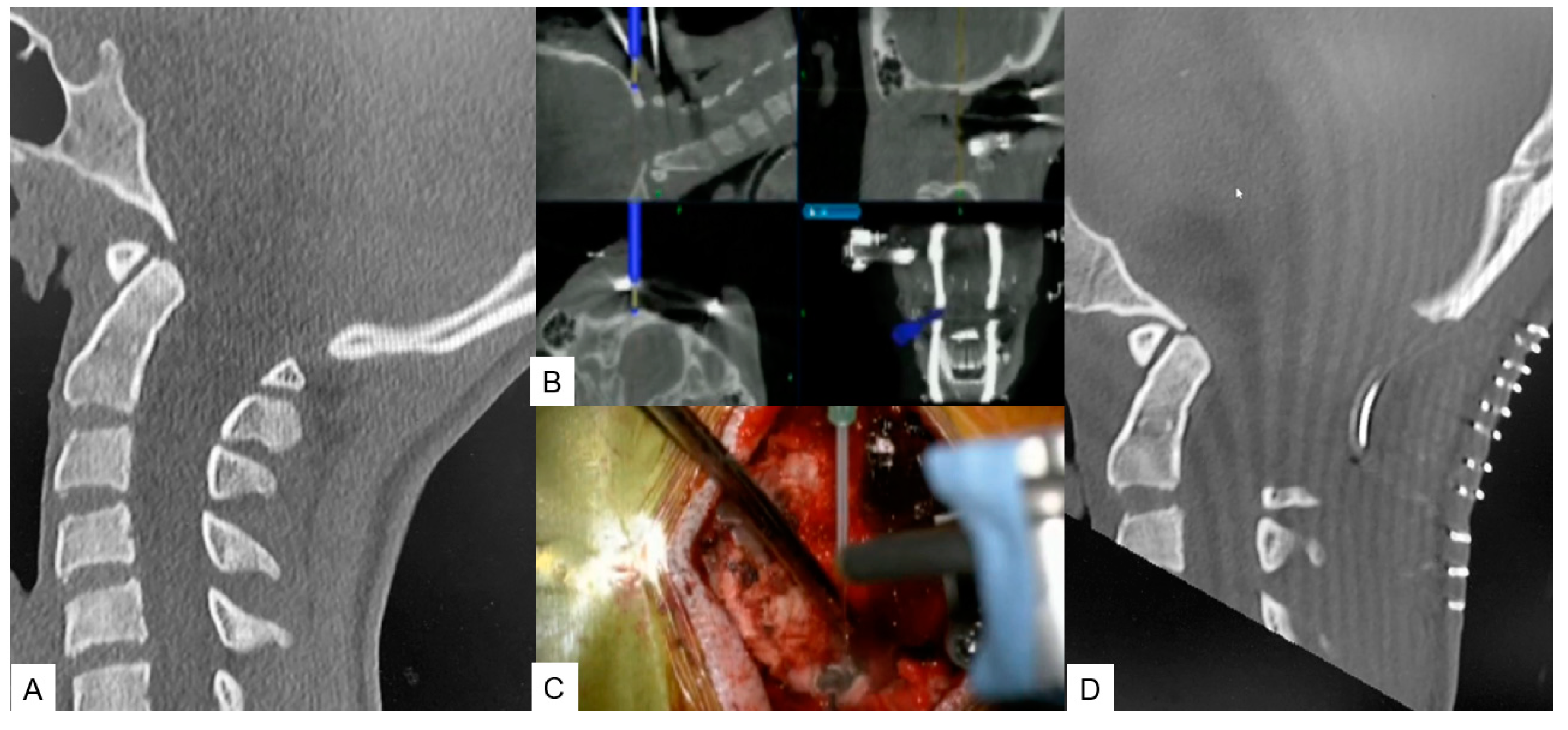

2.2.2. Modified Goel technique

Stabilization of C1-C2 level can prove to be challenging due to lower fusion rates compared to the other cervical levels, as the motion in this particular segment is significantly higher. For this approach we propose C1 LMS with C2 pedicle screw insertion. A careful posterior approach as described in Midpoint technique should be made to avoid vessel injury. After that the ideal entry point should be marked with a high speed burr without applying strong downward forces at C2 vertebra. Finally, the trajectory is made by using a navigated pedicle probe with appropriate tapping.

Figure 3.

Case 3, 5 years old male, Down syndrome, Anterior atlantoaxial subluxation, Modified Goel technique. A: Preoperative lateral cervical radiogram, B, C: Intraoperative navigation image of C2 pedicle screw insertion, D, E: Intraoperative navigation image of C1 lateral mass screw insertion, F: Intraoperative image, F: Postoperative lateral cervical radiogram.

Figure 3.

Case 3, 5 years old male, Down syndrome, Anterior atlantoaxial subluxation, Modified Goel technique. A: Preoperative lateral cervical radiogram, B, C: Intraoperative navigation image of C2 pedicle screw insertion, D, E: Intraoperative navigation image of C1 lateral mass screw insertion, F: Intraoperative image, F: Postoperative lateral cervical radiogram.

2.2.3. Midpoint technique for C1 lateral mass screw (LMS) placement

A careful and precise posterior surgical exposure is required for this technique. Following which, retraction of the posterior atlantoaxial venous plexus inferiorly is necessary by using a Penfield retractor to separate the posterior arch from the inferior aspect. Firstly, the entry point for this screw is 8mm anterior from the posterior arch and caudal aspect (Midpoint). A navigated high-speed burr with a 2mm tip is used for precision and safety. Secondly, by using a navigated pedicle probe, penetration down to the anterior aspect of the cortex of C1 anterior arch must be made. At the end, bicortical placement of C1 LMS is performed.

Figure 4.

Case 4, 68 years old male, Anterior atlantoaxial subluxation, Modified Goel fixation. A: Preoperative cervical lateral radiogram, B: Preoperative midsagittal T2 weighted MR imaging, C: Intraoperative navigated high-speed burr, D: Intraoperative lateral mass screwing, E: Various C1 lateral mass entry points in lateral, F: Insertion point of mid-point technique (red circle), G: Postoperative cervical lateral radiogram.

Figure 4.

Case 4, 68 years old male, Anterior atlantoaxial subluxation, Modified Goel fixation. A: Preoperative cervical lateral radiogram, B: Preoperative midsagittal T2 weighted MR imaging, C: Intraoperative navigated high-speed burr, D: Intraoperative lateral mass screwing, E: Various C1 lateral mass entry points in lateral, F: Insertion point of mid-point technique (red circle), G: Postoperative cervical lateral radiogram.

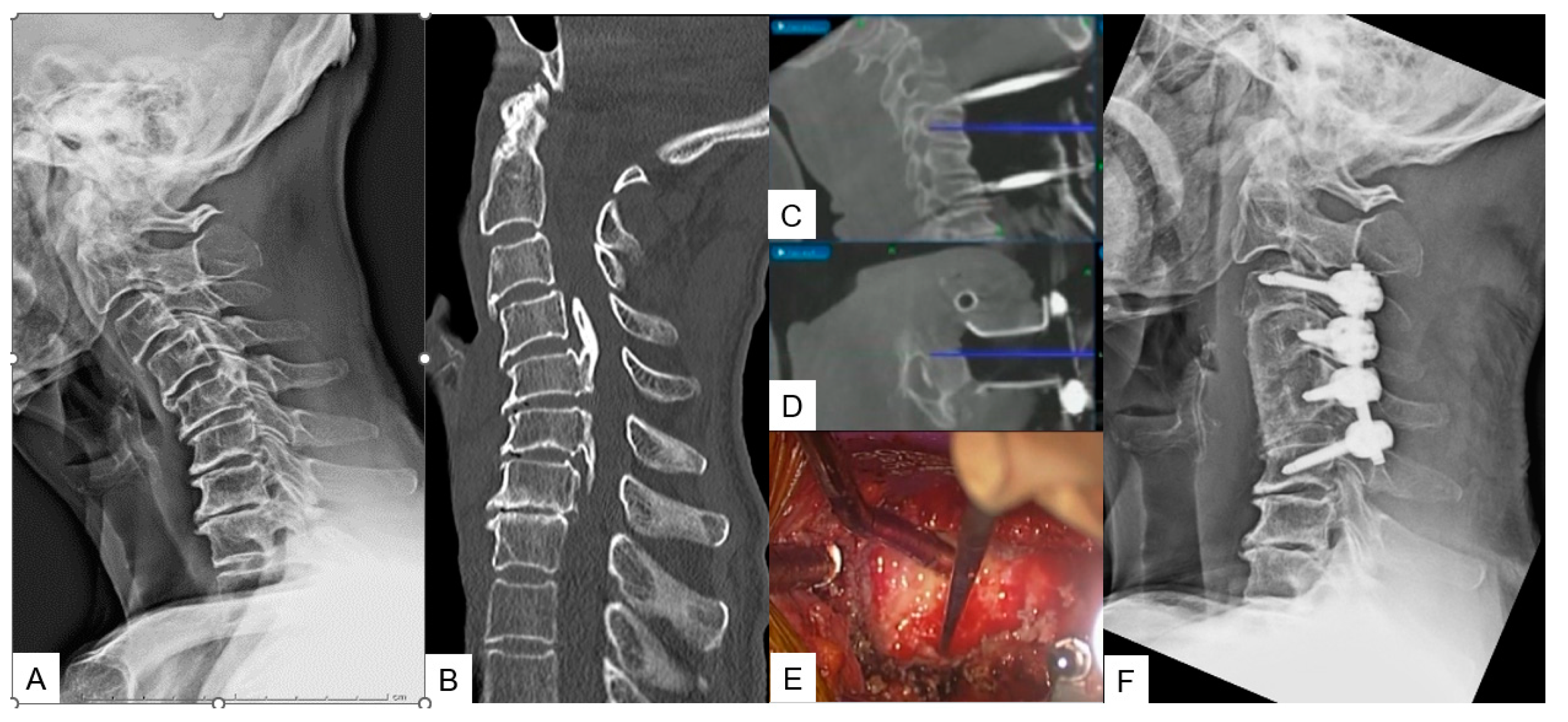

2.2.4. Minimally Invasive Cervical Pedicle Screw Fixation (MICEPS)

During this technique, the patient’s positioning is very important. Thus, it is recommended that prone position with a carbon Mayfield cranial support on a Jackson frame which provides additional stability. Initially a small incision at the prominent C7 spinous process for reference frame attachment is advised, followed by an O-arm scan. Preoperatively CT scan verification for pedicle anatomy should be performed and studied. Ideally, bilateral 4cm skin incisions after navigation verification are enough for C3-C6 fixation. At the end, a new O-arm scan should be performed for verification of anatomical pedicle screw placement. During open posterior cervical screw fixation, complications such as high infection rates, postoperative pain or kyphotic deformity are frequent met. Thus, with this lateral minimal technique it is feasible to reduce this rate due to minimal surgical exposure.

A: Preoperative cervical lateral radiogram, B: Intraoperative image, C: Intraoperative sagittal navigation image, D: Intraoperative axial navigation image, E: Postoperative cervical lateral radiogram.

Figure 5.

Case 5, 62 years old female, Brest cancer, C4 metastasis, C2-6 posterior fusion.

Figure 5.

Case 5, 62 years old female, Brest cancer, C4 metastasis, C2-6 posterior fusion.

3. Thoracic spine

3.1. Anterior application

3.1.1. Anterior correction for Lenke type 5

A lateral right decubitus position is appropriate for this approach. A left oblique skin incision of approximate 20 cm is made along 10th or 11th rib. After superficial dissection through abdominal fat, external oblique, internal oblique, and transverse abdominal muscles are split by the mentioned order. Then a circumferential dissection of the diaphragm is necessary for further exposure. The use of hand-held retractor minimizes the risk of ureter and vascular injury. Usually, the reference frame’s position which is attached to the spinous process must be divided equally between the two surgical edges to maximize accuracy. During the next step, careful screw insertion must be made using navigation for positional accuracy and length safety starting from the furthest fused segment. After the entry point is decided and made using a navigated high-speed bur or an awl, a navigated probe is inserted down to the opposite cortex. For correct measurement of screw’s length, the opposite cortex must be penetrated. Two of the screws should be placed with a 20-degree-angle to provide extra stability for correction maneuvers. Before correction maneuvers are performed, discectomies must be performed, to facilitate further release and to achieve adequate fusion. Most of the desired correction can be obtained during the first step by placing the anterior rod and rotating it 90 degrees to create lordosis. Following which, the only way to achieve further correction is by in situ benders. At the end of correction an x-ray verification should always be made.

Figure 6.

Case 6, 15 years old female, Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis LT11-L3enke Type 5C, T12-L3 anterior fusion. Preoperative 46 degrees of Cobb angle (T12-L3) became 1 degree. A: Preoperative posteroanterior spine radiogram, B Preoperative lateral spine radiogram, C: Intraoperative image, D: Intraoperative axial navigation image, E: Intraoperative coronal navigation image, F: Postoperative posteroanterior spine radiogram, G: Postoperative lateral spine radiogram.

Figure 6.

Case 6, 15 years old female, Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis LT11-L3enke Type 5C, T12-L3 anterior fusion. Preoperative 46 degrees of Cobb angle (T12-L3) became 1 degree. A: Preoperative posteroanterior spine radiogram, B Preoperative lateral spine radiogram, C: Intraoperative image, D: Intraoperative axial navigation image, E: Intraoperative coronal navigation image, F: Postoperative posteroanterior spine radiogram, G: Postoperative lateral spine radiogram.

3.2. Posterior application

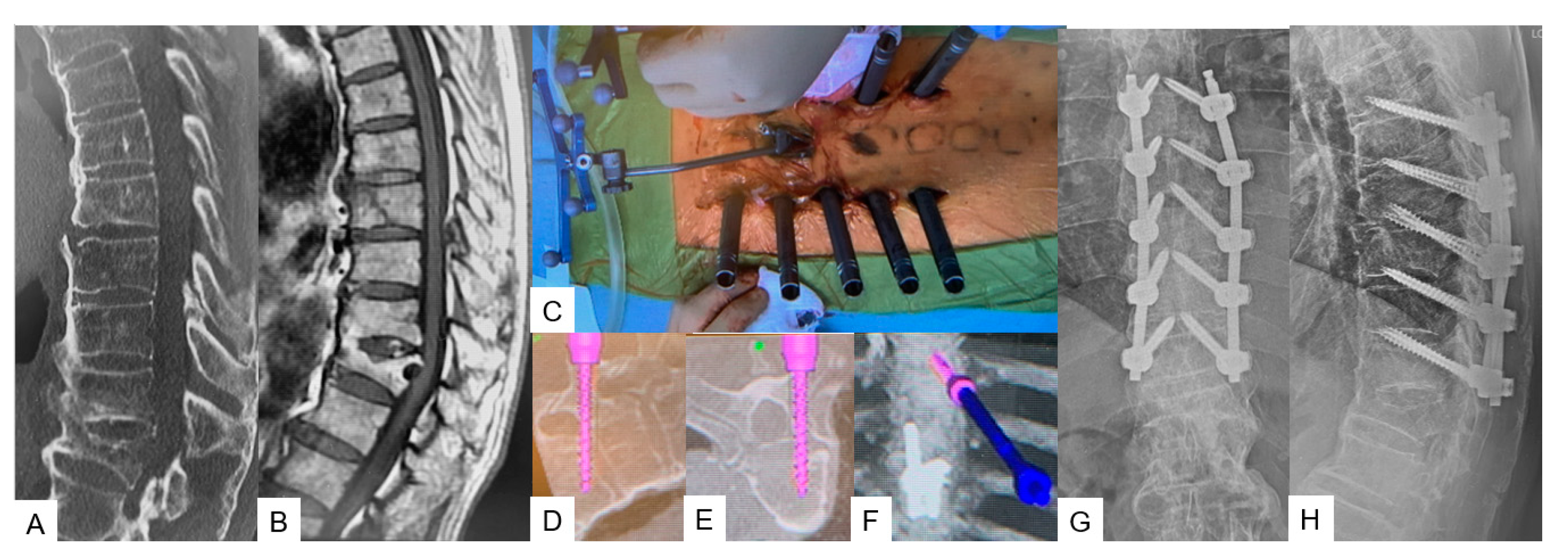

3.2.1. Transdiscal screw for DISH (diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis) fracture

The patient can be positioned in prone or lateral decubitus position either, though sometimes prone position can widen the fracture window especially in DISH cases. A 1.5cm incision in the middle line above the most cranial fused spinous process level is recommended for reference frame placement, followed by an O-arm scan. After marking the appropriate pedicle entry point, the probe for the transdiscal screw trajectory should be aimed through pedicle to the upper endplate and the anterior 1/3 of the inferior endplate of the upper vertebra without reaching the anterior vertebral body wall. The desired angulation should be no more than 25-30 degrees, otherwise the rod can not be held firmly well in the tulip. Postoperatively, X-rays should always be taken for screw placement and alignment verification.

Figure 8.

Case 8, 85 years old male, T8 fracture of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) patient. A: Preoperative sagittal reconstruction CT, B Preoperative sagittal T1 weighted MR imaging, C: Intraoperative image, D: Intraoperative sagittal navigation image, E: Intraoperative axial navigation image, F: Intraoperative 3D navigation image, G: Postoperative anteroposterior radiogram, H: Postoperative lateral radiogram.

Figure 8.

Case 8, 85 years old male, T8 fracture of diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) patient. A: Preoperative sagittal reconstruction CT, B Preoperative sagittal T1 weighted MR imaging, C: Intraoperative image, D: Intraoperative sagittal navigation image, E: Intraoperative axial navigation image, F: Intraoperative 3D navigation image, G: Postoperative anteroposterior radiogram, H: Postoperative lateral radiogram.

4. Discussion

The purpose of each surgical procedure, depending on the case, is to achieve solid bone fusion, adequate decompression and restoration of spinal alignment. Regarding anterior cervical decompression, for ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL), inadequate decompression can lead to poor clinical outcomes and future neurologic deterioration [

8] By using the c-arm free technique the surgeon is always able to verify the amount of decompression and the anatomical area [

9]. Also, complications such as CSF leakage which are frequently met can be reduced. Thus, the merit of this technique is based on the fact that the decompression is far more precise as the surgeon is able receive live feedback during the surgery for the location and the amount of decompression [

9]. Recent studies suggest that anterior decompression has excellent long-term outcomes for more than 10 years [

10]. Onari et al in a retrospective study of 30 patients, reported that in 26 of them, OPLL progression was observed after surgery but due to adequate decompression, there was no clinical deterioration [

11].

Likewise, a successful posterior fossa decompression for Chiari malformation type 1 (CM1) is mainly dependent on the amount of bone resection, which sometimes differs from surgeon to surgeon. Anatomical variations such as hypoplasia of basioccipital bone, fused segments, and platybasia can coexist [

12,

13,

14]. While operating under these conditions, a limited craniotomy may result in insufficient decompression but a large one may lead to the descendance of cerebellum through the decompressed area. Consequently, with the c-arm free technique the surgeon can approach carefully and achieve accurate decompression [

15]. In a retrospective study made by Limonadi et al, the average surgical time was 249 minutes [

16], though, with a navigation system, the surgical time can be decreased [

15].

For atlantoaxial anterior subluxation achieving stability and bony fusion with minimal soft tissue detachment is of the utmost importance as the patient can be mobilized immediately following surgery without a collar bracing [

17]. Although our C-arm free technique for this condition is also openly approached, the advantage of this method is that the surgical exposure is minimal as the lateral mass is not necessarily directly exposed [

18]. Usually, the venous plexus is exposed and retracted caudally and that action results in blood loss. Guo et al reported that the average blood loss during C1-C2 fixation was 219.1 ± 195.6 mL [

19] while with our technique we reported that the average blood loss was 100 mL [

18]. Additionally, the merit of this technique resides in precise entry points, screw placement and nominal postoperative pain. Another C-arm free technique for posterior cervical fixation is the minimally invasive cervical pedicle screw fixation (MICEPS). Usually during the pedicle screw placement, the danger lies in a vertebral artery injury [

20]. Thus, with this technique we can safely approach through the pedicle as there is a live feedback regarding the trajectory. Ishikawa et al in a retrospective study, reported that the pedicle breach rate with O-arm navigation was 2.8% [

21]. Less compared with Yukawa’s et al study who reported that from 620 C-arm placed pedicle screws 3,9% demonstrated pedicle breach and 9,2% screw exposure [

22].

Thoracic deformity correction for Lenke 5 scoliosis in pediatric patients can prove to be challenging. Scoliosis is a three-dimensional deformity and adequate correction usually requires bone fusion of mobile segments. Especially, in young patients, the preservation of mobile segments equals to less back pain and decreased rates of degeneration [

23]. Wang et al in a retrospective study with an 8 year follow up reported that both posterior and anterior fixation can achieve sufficient correction, but the group of anterior correction had significantly less fused segments 5.1 ± 0.6 comparing to the posterior who had 7.0 ± 1.3 [

24]. Moreover, Hirase et al reported that posterior fixation has higher rates of proximal junctional kyphosis than anterior [

25]. Another important issue in thoracic spine surgery is severe osteoporotic patients with unstable fracture patterns. Transdiscal screw fixation can significantly increase the pull-out screw force resulting in more stable fixation. The latest studies reported that bicortical screws can be 1.6-1.8 times stronger than pedicle screw insertion [

26]. Moreover, sometimes the posterior fixation alone cannot be sufficient, especially in high-energy burst fractures with kyphotic deformity of the thoracic spine where anterior column support is mandatory [

27].

Finally, ionizing radiation can gradually lead to indirect DNA lesions and cellular irregularity [

28]. Even though during MIS techniques the surgeon can reduce the soft tissue detachment and decrease the complication rates it does not change the fact that many of them are c-arm dependent. By using the c-arm free techniques the medical stuff is able to perform high precision surgery but reduce the radiation hazard to minimum [

18].

5. Conclusion

The minimally invasive C-arm-free technique provides the benefit of precision with zero radiation exposure. In expert hands, it can significantly reduce surgical time and blood loss. In the near future, O-arm navigated spine surgery will prove to be a golden tool for surgeons who perform a large number of operations annually.

Data Availability Statement:.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.T.; writing – original draft, K.Z. writing – review I.C. and N.S..; methodology, S.A.; data curation, Y.F., T.T. and TM. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Okayama Rosai Hospital (protocol code 3XX, 29th Aug 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients to publish this paper.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by the Okayama Spine Group and Japanese MIST society.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Mobbs RJ, Phan K. History of Retractor Technologies for Percutaneous Pedicle Screw Fixation Systems. Orthop Surg. 2016, 8, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Otomo N, Funao H, Yamanouchi K, Isogai N, Ishii K. Computed Tomography-Based Navigation System in Current Spine Surgery: A Narrative Review. Medicina (Kaunas). 2022, 58, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif S, Afsar A. Learning Curve and Minimally Invasive Spine Surgery. World Neurosurg. 2018, 119, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simony A, Hansen EJ, Christensen SB, Carreon LY, Andersen MO. Incidence of cancer in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis patients treated 25 years previously. Eur Spine J. 2016, 25, 3366–3370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cristante AF, Barbieri F, da Silva AAR, Dellamano JC. Radiation Exposure During Spine Surgery Using C-Arm Fluoroscopy. Acta Ortop Bras. 2019, 27, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willson MC, Ross JS. Postoperative spine complications. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2014, 24, 305–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croci DM, Nguyen S, Streitmatter SW, Sherrod BA, Hardy J, Cole KL, Gamblin AS, Bisson EF, Mazur MD, Dailey AT. O-Arm Accuracy and Radiation Exposure in Adult Deformity Surgery. World Neurosurg. 2023, 171, e440–e446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardoso MJ, Koski TR, Ganju A, Liu JC. Approach-related complications after decompression for cervical ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Neurosurg Focus. 2011, 30, E12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka M, Suthar H, Fujiwara Y, Oda Y, Uotani K, Arataki S, Yamauchi T, Misawa H, Intraoperative O-arm navigation guided anterior cervical surgery; A technical note and case series. Interdiscip Neurosurg 2021, 26, 101288. [CrossRef]

- Matsuoka T, Yamaura I, Kurosa Y, Nakai O, Shindo S, Shinomiya K: Long-term results of the anterior floating method for cervical myelopathy caused by ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine 2001, 26, 241–248. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Onari K, Akiyama N, Kondo S, Toguchi A, Mihara H, Tsuchiya T: Long-term follow-up results of anterior interbody fusion applied for cervical myelopathy due to ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine 2001, 26, 488–493. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karagöz F, Izgi N, Kapíjcíjoğlu Sencer S. Morphometric measurements of the cranium in patients with Chiari type I malformation and comparison with the normal population. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2002, 144, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menezes, AH. Primary craniovertebral anomalies and the hindbrain herniation syndrome (Chiari I): data base analysis. Pediatr Neurosurg. 1995, 23, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hiremath SB, Fitsiori A, Boto J, Torres C, Zakhari N, Dietemann JL, Meling TR, Vargas MI. The Perplexity Surrounding Chiari Malformations - Are We Any Wiser Now? Am J Neuroradiol. 2020, ;41, 1975-1981.

- Tanaka M, Sharma S, Fujiwara Y, Arataki S, Omori T, Kanamaru A, Kodama Y, Saad H, Yamauchi T. Accurate Posterior Fossa Decompression Technique for Chiari Malformation Type I and a Syringomyelia With Navigation: A Technical Note. Int J Spine Surg. 2023, 17, 8483. [Google Scholar]

- Limonadi FM, Selden NR. Dura-splitting decompression of the craniocervical junction: reduced operative time, hospital stay, and cost with equivalent early outcome. J Neurosurg. 2004, 101, 184–188. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess LC, Wainwright TW. What Is the Evidence for Early Mobilisation in Elective Spine Surgery? A Narrative Review. Healthcare (Basel). 2019, 7, 92. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka M, Sonawane S, Fujiwara Y, Uotani K, Arataki S, Yamauchi T, Ye Y, Misawa H. C-arm Free O-arm Navigated Posterior Atlantoaxial Fixation in Down Syndrome: A Technical Note. Acta Med Okayama. 2022, 76, 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, J.; Lu, W.; Ji, X.; Ren, X.; Tang, X.; Zhao, Z.; Hu, H.; Song, T.; Du, Y.; Li, J.; et al. Surgical treatment of atlantoaxial subluxation by intraoperative skull traction and C1-C2 fixation. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2020, 21, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder GD, Hsu WK. Vertebral artery injuries in cervical spine surgery. Surg Neurol Int. 2013, 4 (Suppl 5), S362–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishikawa Y, Kanemura T, Yoshida G, Matsumoto A, Ito Z, Tauchi R, Muramoto A, Ohno S, Nishimura Y. Intraoperative, full-rotation, three-dimensional image (O-arm)-based navigation system for cervical pedicle screw insertion. J Neurosurg Spine. 2011, 15, 472–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yukawa Y, Kato F, Ito K, Horie Y, Hida T, Nakashima H, Machino M. Placement and complications of cervical pedicle screws in 144 cervical trauma patients using pedicle axis view techniques by fluoroscope. Eur Spine J. 2009, 18, 1293–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketenci IE, Yanik HS, Ulusoy A, Demiroz S, Erdem S. Lowest Instrumented Vertebrae Selection for Posterior Fusion of Lenke 5C Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis: Can We Stop the Fusion One Level Proximal to Lower-end Vertebra? Indian J Orthop. 2018, 52, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang ZW, Shen YQ, Wu Y, Li J, Liu Z, Xu JK, Chen QX, Chen WS, Chen LW, Zhang N, Li FC. Anterior Selective Lumbar Fusion Saving More Distal Fusion Segments Compared with Posterior Approach in the Treatment of Adolescent Idiopathic Scoliosis with Lenke Type 5: A Cohort Study with More Than 8-Year Follow-up. Orthop Surg. 2021 , 13, :2327-2334.

- Hirase T, Ling JF, Haghshenas V, Thirumavalavan J, Dong D, Hanson DS, Marco RAW. Anterior versus posterior spinal fusion for Lenke type 5 adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Spine Deform. 2022, 10, 267–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka M, Fujiwara Y, Uotani K, Kamath V, Yamauchi T, Ikuma H. Percutaneous transdiscal pedicle screw fixation for osteoporotic vertebral fracture: A technical note. Interdiscip Neurosurg. 2021, 26, 00903. [Google Scholar]

- Lall RR, Smith ZA, Wong AP, Miller D, Fessler RG. Minimally invasive thoracic corpectomy: surgical strategies for malignancy, trauma, and complex spinal pathologies. Minim Invasive Surg. 2012, 2012, 213791. [Google Scholar]

- Vozenin-Brotons MC. Tissue toxicity induced by ionizing radiation to the normal intestine: understanding the pathophysiological mechanisms to improve the medical management. World J Gastroenterol. 2007, 13, :3031–3032.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).