1. Introduction

Emulsified surimi products are widely accepted by consumers because they can offer a wide choice of textures and flavors, and high nutritional value and cost performance [

1,

2,

3]. Most emulsified surimi products are added with phosphorus, such as sodium tripolyphosphate, sodium pyrophosphate, and sodium hexametaphosphate, to increase the solubility of salt soluble proteins, dissociate actomyosin, and then improve gel properties [

4,

5], which determines the quality and shelf life of the products. However, overtaking phosphorus can cause tooth, bone, and other diseases [

6]. So some people are increasingly paying attention to reduced-phosphate foods.

Using potassium bicarbonate to replace phosphorus in aquatic and meat products has been reported by some studies [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Xie et al. [

7] found that using potassium bicarbonate to partially replace sodium tripolyphosphate can improve the processing properties and gel properties of silver carp batter. Li et al. [

8] used potassium bicarbonate, trehalose, and chitosan to keep the properties stability of tilapia fillets stored at -18 °C, they found that using a suitable concentration of potassium bicarbonate, trehalose, and chitosan can increase its water retention capacity and quality. Jaico, Prabhakar, Adhikari, Singh, & Mohan [

9] reported that adding potassium bicarbonate causes meatloaf to produce a pinkish-red colour, and significant tenderizing and juiciness effects, leading to its’ eating quality, textural and sensorial attributes were improved. Mohan et al. [

10] showed that the addition of potassium bicarbonate can enhance the processing and texture properties of processed ground beef. Lee et al. [

11] reported that potassium bicarbonate is a healthier phosphorus substitute, which can improve the quality of marinating chicken meat. Our previous studies reported that using potassium bicarbonate to partially/total replace sodium tripolyphosphate causes the cooking yield, hardiness, springiness, chewiness, storage modulus, β-sheet and β-turns structures content of silver carp batter to significantly increase, which also improves the gel and rheology characteristics [

7]. However, the effect of water holding capacity, gel properties, microbe and TBARS from cooked reduced-phosphate silver carp surimi batters during cold storage were not studied. Therefore, based on the above, this study’s aim was to analyse the effect of potassium bicarbonate on water stability, whiteness, texture properties, TBARS, total volatile basic nitrogen and total plate count of cooked reduced-phosphate silver carp surimi batter stored at 4 °C for 7days.

2. Results and Discussion

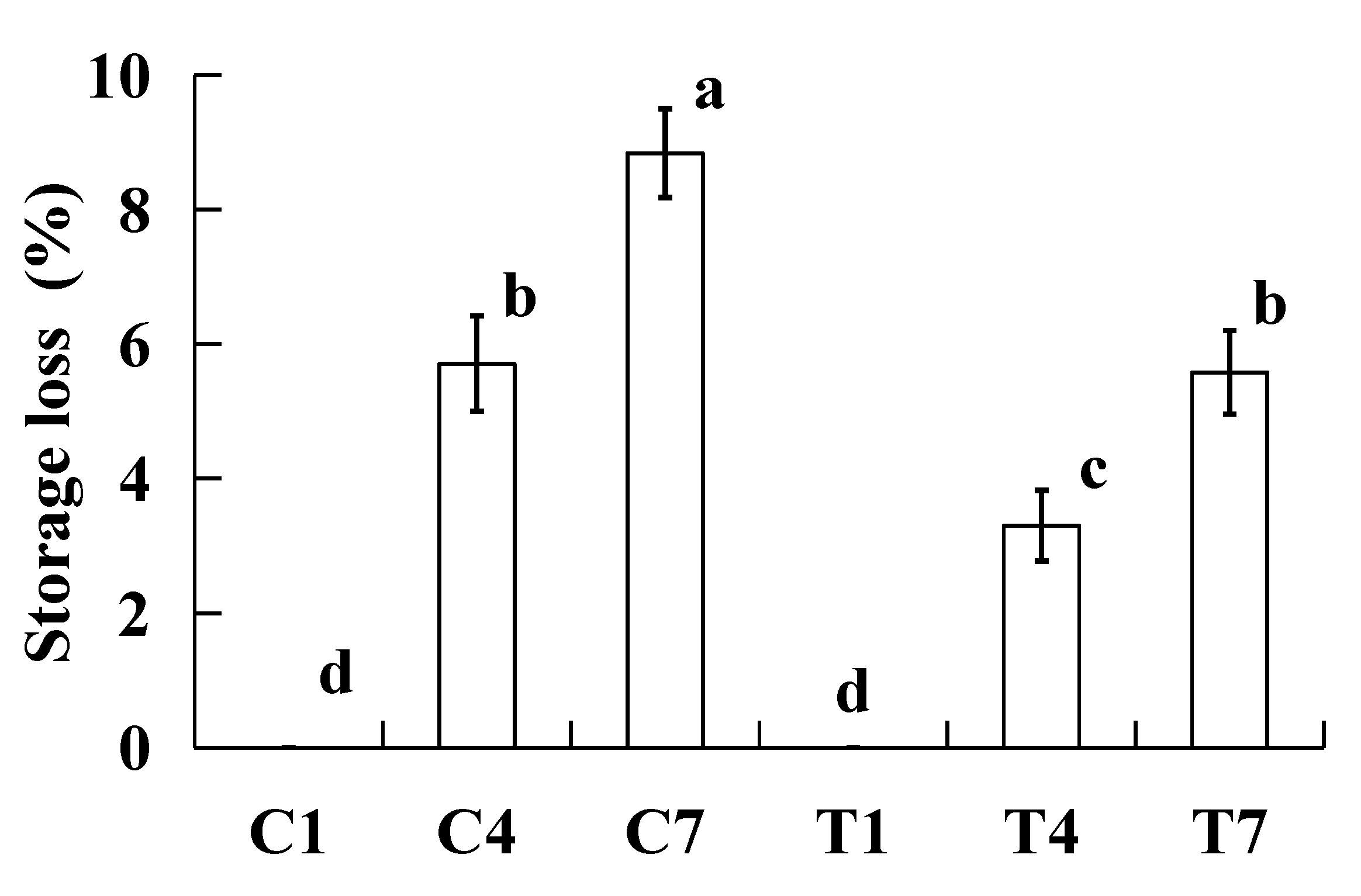

2.1. Storage loss

Storage loss can reflect the stability of water and fat in the cooked surimi products during storage, and affect product quality. The effect of storage loss of the cooked silver carp surimi batters were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage is presented in

Figure 1. All the storage losses of cooked silver carp surimi batters significantly increased (

P < 0.05) with increasing the storage times. The reason is that the protein and fat of cooked silver carp surimi batters were oxidized, leading to the gel network structure being destroyed during the cold storage, and the water retention capacity was decreased [

12]. In addition, the growth and propagation of microorganisms during cold storage can damage the gel structure and increase the loss of water and oil [

13]. At the same storage time, the storage loss of cooked silver carp surimi batters without potassium bicarbonate significantly increased (

P < 0.05) compared to that of with potassium bicarbonate. The samples of C4 and T7 had the same storage loss. Some researchers reported that potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate can increase the pH of a water solution, whereas the buffering capacity of potassium bicarbonate was better than sodium tripolyphosphate [

14], as a result, the sample with potassium bicarbonate had good water- and fat- holding capacity, and lower storage loss [

10]. Our previous study found that the processing characteristics of silver carp surimi batter were improved when using potassium bicarbonate to replace sodium tripolyphosphate [

7]. Hence, the addition of potassium bicarbonate increased the stability of water in the cooked silver carp surimi batters during cold storage.

2.2. Low-field NMR

Low-field is a rapid nondestructive method of determining moisture and fluidity in muscle and aquatic products [

15,

16]. The changes in T2 relaxation of the cooked silver carp surimi batters were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage as shown in

Table 1. All the samples showed three peaks, named T

2b (bond water, 0-10 ms), T

21 (immobilized water, 10-100 ms), and T

22 (free water, 100-1000 ms), respectively [

17]. Therein, T

2b represents the water tightly associated with protein and macro-molecular constituents [

18]. T

21 represents the intra-myofibrillar water and water within the protein structure [

19]. T

22 represents the extra-myofibrillar water, it is easy to flow during processing and storage [

20]. Compared with the samples without potassium bicarbonate, the initial relaxation times of T

2b, T

21, and T

22 in the samples with potassium bicarbonate were shorter (

P < 0.05) at the same cold storage times, and that means that the water in the samples with potassium bicarbonate was a closer connection. As is known to all, the T

2 could reflect the fluidity of water laterally, a longer T

2 means a higher fluidity [

19]. Meanwhile, the peak ratios of P

2b and P

22 in the samples with potassium bicarbonate were decreased (

P < 0.05), and the P

21 was increased (

P < 0.05) at the same cold storage time compared with the samples without potassium bicarbonate. The other, with increasing the cold storage times, the initial relaxation times of T

21 and T

22 in all samples increased significantly (

P < 0.05), accompanied by the peak ratio of P

22 increased (

P < 0.05), and the P

21 decreased (

P < 0.05). The results mean that adding potassium bicarbonate could lower the fluidity of water in the cooked silver carp surimi batters during cold storage.

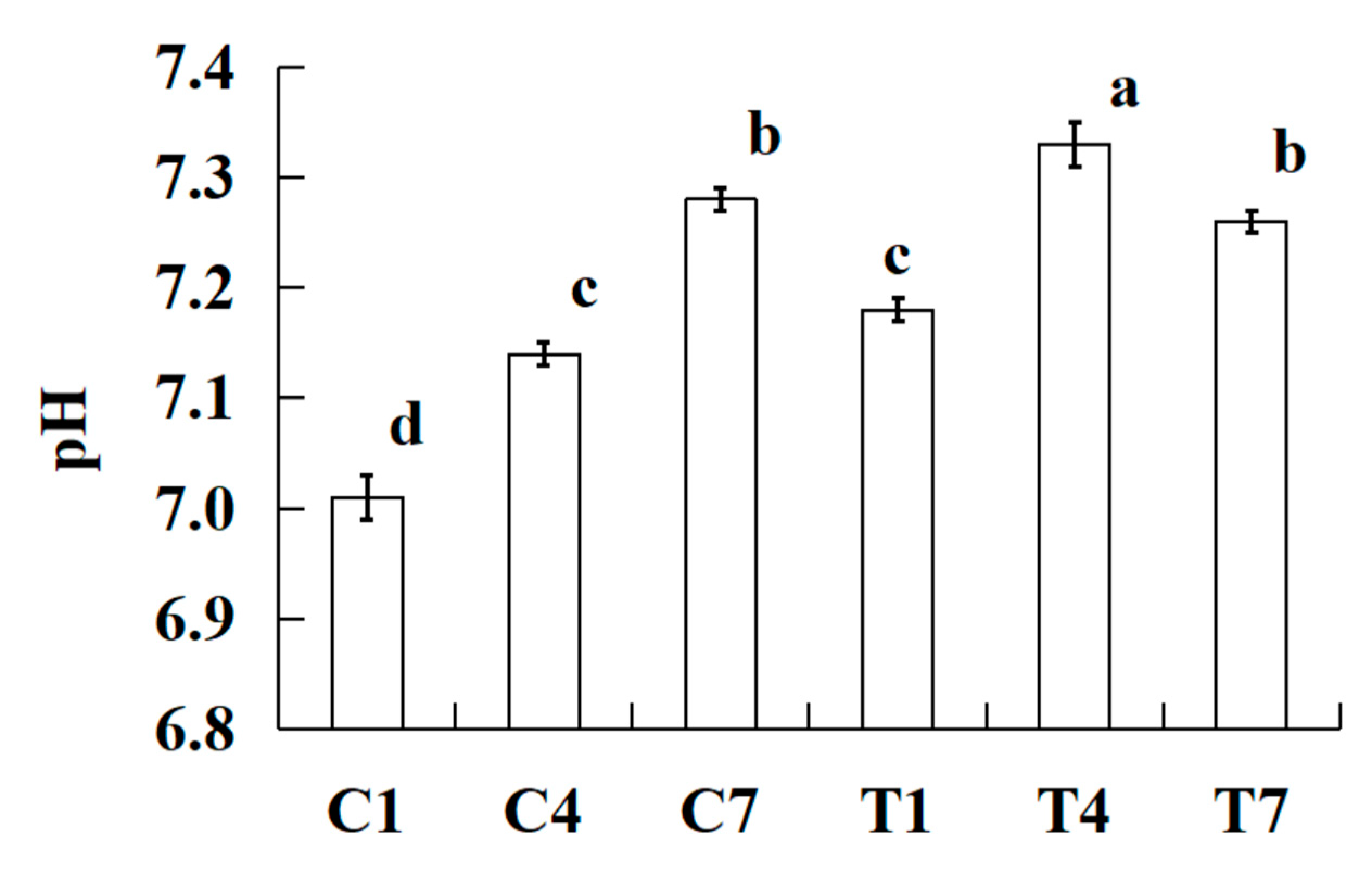

2.3. pH

The changes in pH of the cooked silver carp surimi batters were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage as shown in

Figure 2. The pH of all cooked silver carp surimi batters were increased significantly (

P < 0.05) with the increase of cold storage time, except the sample of T7. It is possible that microbial growth and reproduction utilize the proteins in cooked silver carp surimi batters to generate alkaline nitrogen-containing compounds during cold storage, such as amines and trimethylamine, resulting in an increase in pH value [

21,

22,

23]. In addition, previous studies found that lipid oxidation and protein oxidation could produce an alkaline substance, which improves the pH of pork batters during cold storage [

24,

25]. Especially, due to the sample with potassium bicarbonate had a higher pH than that of the sample without potassium bicarbonate, after 4 days of cold storage, there is a certain degree of decrease in pH due to bacterial metabolism utilizing organic small molecules for fermentation and acid production [

26].

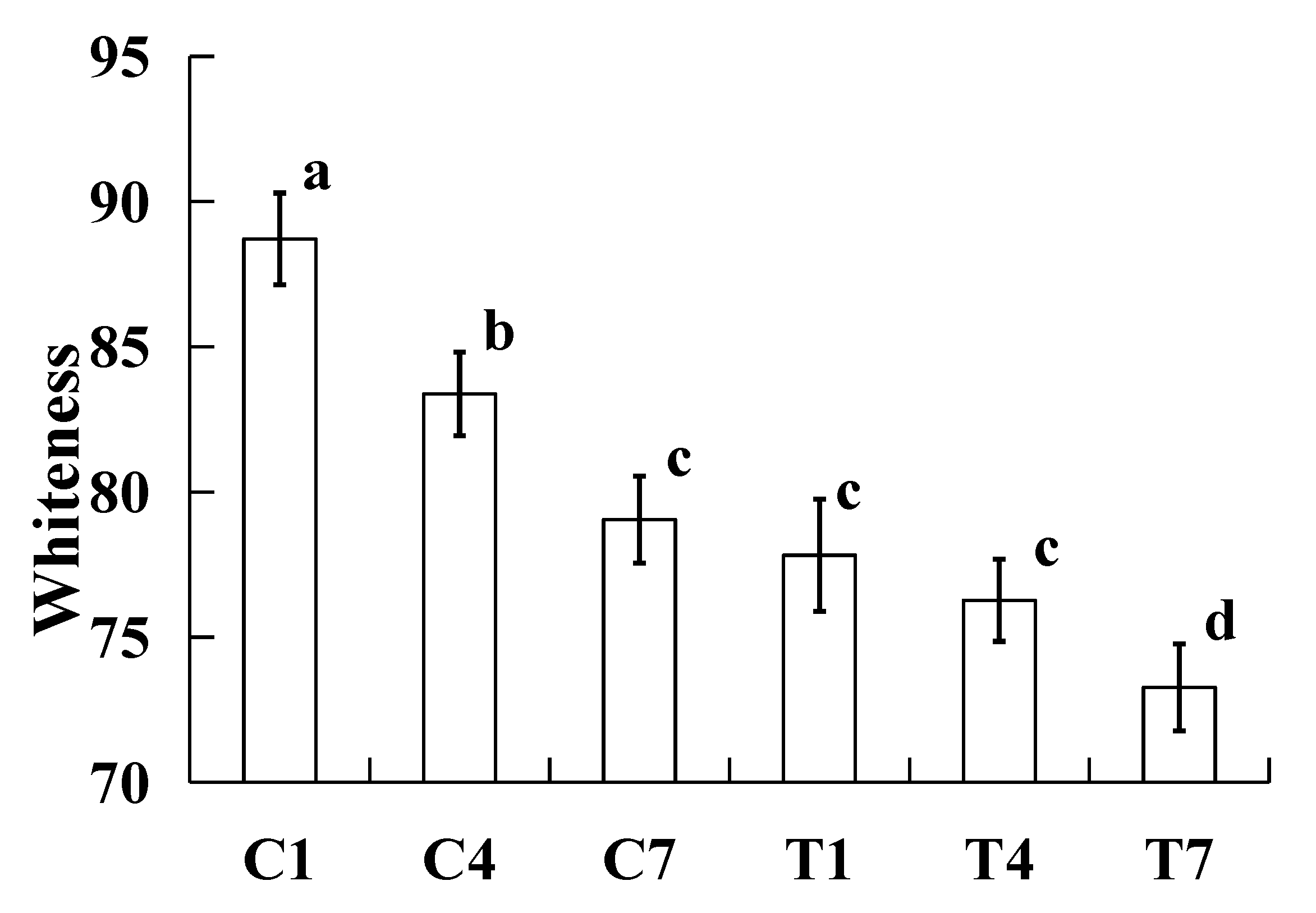

2.4. Whiteness

The effect of the whiteness of the samples were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage as shown in

Figure 3. All the whiteness values of cooked silver carp surimi batters significantly increased (

P < 0.05) with the increase of storage time, except the T1 and T4. The changes in whiteness were caused by light resection [

27]. More moisture on the surface of cooked samples caused the increase in whiteness. In this study, the water was lost during cold storage (

Figure 1), thus, the whiteness was lowered with increasing storage time. In addition, the sample with potassium bicarbonate has a darker colour [

7], the changes in whiteness between the 1st and 4th days were not significantly different (

P > 0.05), and the results indicated that the colour of the sample with potassium bicarbonate was more stable than that of the sample without potassium bicarbonate.

2.5. Texture properties

The effect of texture properties of the samples were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage as shown in

Table 2. All the hardness values of cooked samples increased significantly with the increase of cold storage time (

P < 0.05), this is because the moisture content of cooked silver carp surimi batters were decreased (

Figure 1), which led to the hardness value increased [

28]. Meanwhile, the springiness values between the 1st and 4th days were not significantly different (

P > 0.05), and then significantly decreased (

P < 0.05) at the 7th days; the cohesiveness values significantly decreased (

P < 0.05) with the increase of cold storage time. The result was caused by the increase in fat oxidation, microbial, pH and water loss [

29]. In addition, the chewiness of samples with/without potassium bicarbonate was not significantly different (

P > 0.05) with the increase of cold storage time, the main reason is that the hardness values increased significantly with the increase of cold storage time. At the same cold storage time, the texture properties of the sample with potassium bicarbonate were better than that of the sample without potassium bicarbonate, which indicated that the texture properties of the samples with potassium bicarbonate were more stable.

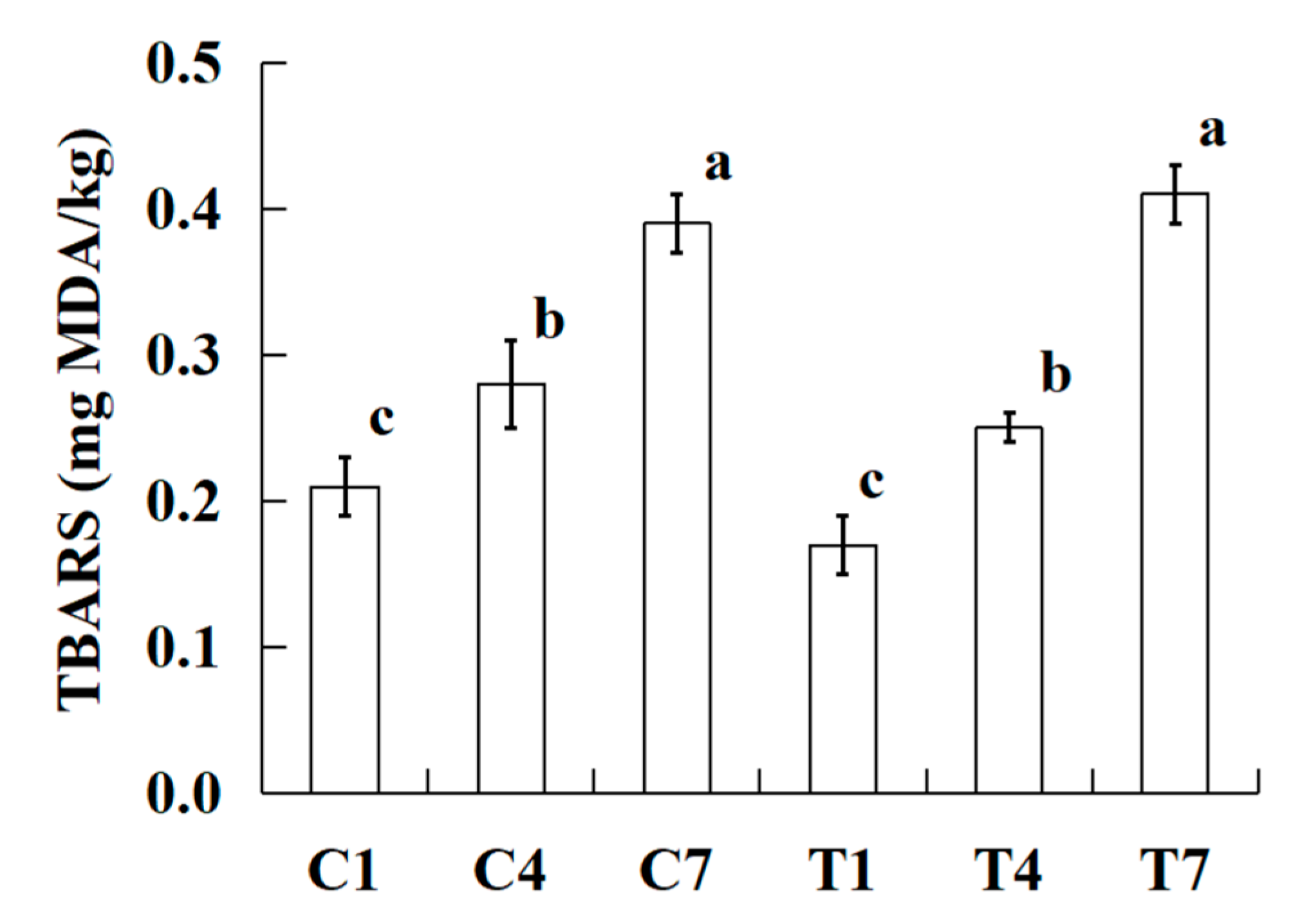

2.6. TBARS

The TBARS values of the samples were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage as shown in

Figure 4. At the same cold storage time, all the TBARS values of cooked silver carp surimi batters were not significantly different (

P > 0.05). Meanwhile, all the TBARS values significantly increased (

P < 0.05) with the increase in cold storage time. It is well known that TBARS value is a widely used indicator for lipid oxidation in aquatic products and processed aquatic products. There is a strong correlation between TBARS value and the degree of fat oxidation in products. The higher the TBARS value, the higher the degree of fat oxidation, the more severe the rancidity, and the more small molecule substances (aldehydes, ketones, acids, etc.) produced [

30,

31]. The result indicated that more fat oxidation were produced during cold storage, more water was washed out to form free water (

Figure 1 and

Table 1), and then free water was in favour of the formation of free radical in the cooked silver carp surimi batter during cold storage, and increased the TBARS value [

32].

2.7. Total volatile basic nitrogen

Total volatile basic nitrogen can analyse the spoilage and deterioration of aquatic products, it reflects the accumulation of volatile ammonia in aquatic product proteins due to decomposing proteins and non-protein substances [

33]. The lower its content, the higher the freshness of aquatic products. The total volatile basic nitrogen values of the samples were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage as shown in

Table 3. All the total volatile basic nitrogen values of cooked silver carp surimi batters were not significantly different (

P > 0.05) at the same cold storage time. Meanwhile, all values increased significantly (

P < 0.05) with increasing cold storage time. It is possible that microorganisms grow rapidly at this stage, causing the total volatile basic nitrogen value to increase rapidly [

34]. Guan et al. [

35] found that the total volatile basic nitrogen of hairtail fish balls were significantly increased when they were stored at 4 °C from 1 to 15 days. Thus, the use of potassium bicarbonate instead of sodium tripolyphosphate has no significant effect on the total volatile basic nitrogen values of cooked silver carp surimi batters.

2.8. Total plate count

The total plate count of the samples were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage as shown in

Table 3. The total plate count of cooked silver carp surimi batters were not significantly different (

P > 0.05) at the same cold storage time. Meanwhile, all the total plate count significantly increased (

P < 0.05) with increasing cold storage times. The reason is possible that all the samples had a similar storage loss (

Figure 1) and pH (

Figure 2), the higher apparent moisture of samples increased the A

w, and the result promoted the growth and reproduction of microorganisms[

36,

37]. Solo-de-Zaldívar, Tovar, Borderías, and Herranz [

38] reported that the total viable bacterial count of the restructured fish muscle products were gradually increasing during chilled storage from 0 to 35 days. The result showed that high pH and total volatile basic nitrogen values were beneficial for the growth of microorganisms during storage.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Materials and silver carp surimi batters prepared

According to the method of our previous study [

7], fresh silver carp and pork back-fact were purchased from a farmer’s market in Shangqiu city (China). Referring to the way of An et al. [

39], the silver carp surimi was prepared. Potassium bicarbonate, sodium tripolyphosphate and sodium chloride (analytically pure) were purchased by Tianjin Boddi Chemical Co., Ltd., (Tianjin, China). The white pepper, garlic powder and sugar were purchased from a local market (Shangqiu, China). All other reagents were analytical pure.

The formulas of raw silver carp surimi batters were as follows: silver carp surimi 100 g, pork back-fact 20 g, ice water 20 g, white pepper 1 g, garlic powder 1.5 g, sugar 3.5 g, sodium chloride 1.5 g, therein, C contained sodium tripolyphosphate 0.4 g; T contained potassium bicarbonate 0.3 g, sodium tripolyphosphate 0.1 g. According to our previous study [

7], the batter was produced, and vacuum packed and stored at 4 °C.

3.2. Cold storage

All the cooked cooked silver carp surimi batters were stored at 4 °C for 7 days. Therein, the samples of C were cold stored at the 1st, 4th and 7th days named as C1, C4 and C7; the samples of T were cold stored at the 1st, 4th and 7th days named as T1, T4 and T7, respectively.

3.3. Determination of storage loss

Storage loss of cooked silver carp surimi batter was determined at 1st, 4th and 7th days, respectively. The sample with casing was weighed (original sample). Then, remove the moisture and reweighed (reweighed sample). The calculation formula of storage loss was shown as follows:

3.4. Low-field NMR measurement

According to the method of our previous study [

7], the low-field NMR was measured and analysed.

3.5. pH measurement

20 g cooked silver carp surimi batter and 80 mL distilled water were homogenized at 15000 rpm, for 10 s on the 1st, 4th and 7th days, respectively. Then pH was determined using a pH meter.

3.6. Whiteness measurement

Colour of cooked silver carp surimi batter core was determined by a colorimeter (Minolta, Japan) on the 1st, 4th and 7th days. Five repetitions were applied to each experimental group. The calculation formula of whiteness was shown as follows:

3.7. Texture properties measurement

According to the method of our previous study [

7], the texture properties was measured and analysed. Five repetitions were applied to each experimental group.

3.8. TBARS measurement

TBARS of cooked silver carp surimi batter was determined by referring to the method of Ulu [

40]. Five repetitions was applied to each experimental group.

3.9. Total volatile basic nitrogen measurement

According to the method of AOAC (2011), the total volatile basic nitrogen of samples was measured.

3.10. Total plate count measurement

According to the method of AOAC (2011), the total plate count of samples was measured.

3.11. Statistical analysis

In each replication, the batters of storage at different times were prepared and 160 cooked silver carp surimi batters (potassium bicarbonate content and sodium tripolyphosphate content) were used. The data were analysed by the one-way ANOVA program and GLM procedure (SPSS v.20.0). Significant differences between means were identified using the LSD procedure, and considered significant at P < 0.05.

4. Conclusion

At the same cold storage time, the use of potassium bicarbonate instead of sodium tripolyphosphate has a significant effect on the storage loss, initial relaxation time, peak ratio, pH, whiteness, hardness, springiness, and cohesiveness of cooked silver carp surimi batters, but has no significant effect on the chewiness, TBARS, total volatile basic nitrogen value and total plate count of cooked silver carp surimi batters. Therein, the storage loss, T2b, T21, and T22, P22 of the sample with potassium bicarbonate have lower values than those of the sample without potassium bicarbonate, and have higher values of pH, and texture properties. With increasing cold storage time, the storage loss, T2b, T21, and T22, P22, pH, hardness, TBARS, total volatile basic nitrogen value and total plate count significantly increased, and the whiteness, springiness, and cohesiveness decreased significantly. From the above, the cold storage performances of cooked silver carp surimi batter with potassium bicarbonate could be improved.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Open Project of Shangqiu Medical College (KFKT23013).

References

- Tong, Y. Q. , Wang, Y. D., Chen, M., Zhong, Q., Zhuang, Y., Su, H. C., & Yang, H. (2023). Effect of high-content ultrasonically emulsified lard on the physicochemical properties of surimi gels from silver carp enhanced by microbial transglutaminase. International Journal Of Food Science and Technology, 58, 2974-2984.

- Yu, J.; Xiao, H.; Xue, Y.; Xue, C. Effects of soybean phospholipids, ovalbumin, and starch sodium octenyl succinate on the mechanical, microstructural, and flavor properties of emulsified surimi gels. LWT 2022, 161, 113260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, H.J.; Rezaei, M.; Shabanpour, B.; Tabarsa, M. Effects of sulfated polysaccharides from green alga Ulva intestinalis on physicochemical properties and microstructure of silver carp surimi. Food Hydrocoll. 2018, 74, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lautrou, M.; Narcy, A.; Dourmad, J.-Y.; Pomar, C.; Schmidely, P.; Montminy, M.-P.L. Dietary Phosphorus and Calcium Utilization in Growing Pigs: Requirements and Improvements. Front. Veter- Sci. 2021, 8, 734365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, R.E.; Bohrer, B.M.; Mejia, S.M.V. Phosphate alternatives for meat processing and challenges for the industry: A critical review. Food Res. Int. 2023, 166, 112624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krithika, M.; Balakrishnan, U.; Amboiram, P.; Shaik, M.S.J.; Chandrasekaran, A.; Ninan, B. Early calcium and phosphorus supplementation in VLBW infants to reduce metabolic bone disease of prematurity: a quality improvement initiative. BMJ Open Qual. 2022, 11, e001841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, C.; Shi, B.-B.; Liu, G.-H.; Li, S.-H.; Kang, Z.-L. Using Potassium Bicarbonate to Improve the Water-Holding Capacity, Gel and Rheology Characteristics of Reduced-Phosphate Silver Carp Batters. Molecules 2023, 28, 5608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Luo, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Guan, Z.Q.; Ling, C.M. Effects of different phosphorus-free water-retaining agents on the quality of frozen tilapia fillets. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 10, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaico, T.; Prabhakar, H.; Adhikari, K.; Singh, R.K.; Mohan, A. Influence of Bicarbonates and Salt on the Physicochemical and Sensory Properties of Meatloaf. J. Food Qual. 2022, 2022, 4788425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, A.; Jaico, T.; Kerr, W.; Singh, R. Functional properties of bicarbonates on physicochemical attributes of ground beef. Lwt 2016, 70, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, N.; Sharma, V.; Brown, N.; Mohan, A. Functional properties of bicarbonates and lactic acid on chicken breast retail display properties and cooked meat quality. Poult. Sci. 2015, 94, 302–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Liu, C.; Cai, L.; Yang, J.; Zhou, J.; Jiang, H.; Shi, Y.; Gu, Z. Effect of High Hydrostatic Pressure Processing on Biochemical Characteristics, Bacterial Counts, and Color of the Red Claw Crayfish Cherax quadricarinatus. J. Shellfish. Res. 2021, 40, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, M.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Yu, D.; Wang, H. Potential nano bacteriostatic agents to be used in meat-based foods processing and storage: A critical review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 131, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varo, M.A.; Martin-Gomez, J.; Serratosa, M.P.; Merida, J. Effect of potassium metabisulphite and potassium bicarbonate on color, phenolic compounds, vitamin C and antioxidant activity of blueberry wine. Lwt 2022, 163, 113585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micklander, E.; Peshlov, B.; Purslow, P.P.; Engelsen, S.B. NMR-cooking: monitoring the changes in meat during cooking by low-field 1H-NMR. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2002, 13, 341–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Lin, Z.; Cheng, S.; El-Aty, A.M.A.; Tan, M. Effect of water-retention agents on Scomberomorus niphonius surimi after repeated freeze–thaw cycles: low-field NMR and MRI studies. Int. J. Food Eng. 2023, 19, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Zhu, M.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, S.; He, H.; Kang, Z.; Ma, H.; Xu, B. Physicochemical and structural changes in myofibrillar proteins from porcine longissimus dorsi subjected to microwave combined with air convection thawing treatment. Food Chem. 2020, 343, 128412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Lin, R.; Cheng, S.; Tan, M. Water dynamics changes and protein denaturation in surf clam evaluated by two-dimensional LF-NMR T1-T2 relaxation technique during heating process. Food Chem. 2020, 320, 126622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.-P.; Kang, Z.-L.; Sukmanov, V.; Ma, H.-J. Effects of soy protein isolate on gel properties and water holding capacity of low-salt pork myofibrillar protein under high pressure processing. Meat Sci. 2021, 176, 108471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.-L.; Xie, J.-J.; Li, Y.-P.; Song, W.-J.; Ma, H.-J. Effects of pre-emulsified safflower oil with magnetic field modified soy 11S globulin on the gel, rheological, and sensory properties of reduced-animal fat pork batter. Meat Sci. 2023, 198, 109087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, A.; Paudel, N.; Poudel, R. Effect of pomegranate peel extract on the storage stability of ground buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) meat. LWT 2021, 154, 112690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaijan, M.; Benjakul, S.; Visessanguan, W.; Faustman, C. Changes of pigments and color in sardine (Sardinella gibbosa) and mackerel (Rastrelliger kanagurta) muscle during iced storage. Food Chem. 2005, 93, 607–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Capillas, C.; Moral, A. Residual effect of CO2 on hake (Merluccius merluccius L.) stored in modified and controlled atmospheres. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2001, 212, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Sukmanov, V.; Kang, Z.; Ma, H. Effect of soy protein isolate on the techno-functional properties and protein conformation of low-sodium pork meat batters treated by high pressure. J. Food Process. Eng. 2019, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, R.; Jebin, N.; Saha, R.; Sarma, D. Antioxidant and antimicrobial effects of kordoi ( Averrhoa carambola ) fruit juice and bamboo ( Bambusa polymorpha ) shoot extract in pork nuggets. Food Chem. 2016, 190, 41–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsani, A.; Hashemi, M.; Afshari, A.; Aminzare, M.; Raeisi, M.; Zeinali, T. Effect of different types of active biodegradable films containing lactoperoxidase system or sage essential oil on the shelf life of fish burger during refrigerated storage. LWT 2019, 117, 108633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Z.-L.; Zou, Y.-F.; Xu, X.-L.; Zhu, C.-Z.; Wang, P.; Zhou, G.-H. Effect of Various Amounts of Pork and Chicken Meat on the Sensory and Physicochemical Properties of Chinese-style Meatball (Kung-wan). Food Sci. Technol. Res. 2013, 19, 963–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W. W., Qin, Y. Y., Ruan, Z. (2021) Effects of high hydrostatic pressure on color, texture, microstructure, and proteins of the tilapia (Orechromis niloticus) surimi gels. Journal of Texture Studies, 52, 177–186.

- Monteiro, M.L.G.; Mársico, E.T.; Rosenthal, A.; A Conte-Junior, C. Synergistic effect of ultraviolet radiation and high hydrostatic pressure on texture, color, and oxidative stability of refrigerated tilapia fillets. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 4474–4481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Shi, H.; Xiong, Q.; Wu, R.; Hu, Y.; Liu, R. A novel strategy for inhibiting AGEs in fried fish cakes: Grape seed extract surimi slurry coating. Food Control. 2023, 154, 109948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachekrepapol, U.; Thangrattana, M.; Kitikangsadan, A. Impact of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus ostreatus) on chemical, physical, microbiological and sensory characteristics of fish burger prepared from salmon and striped catfish filleting by-product. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 30, 100598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivas-Cañedo, A.; Martínez-Onandi, N.; Gaya, P.; Nuñez, M.; Picon, A. Effect of high-pressure processing and chemical composition on lipid oxidation, aminopeptidase activity and free amino acids of Serrano dry-cured ham. Meat Sci. 2020, 172, 108349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özogul, F.; Polat, A.; Özogul, Y. The effects of modified atmosphere packaging and vacuum packaging on chemical, sensory and microbiological changes of sardines (Sardina pilchardus). Food Chem. 2004, 85, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, W.; Chi, Y.; Zhang, S. The use of a tea polyphenol dip to extend the shelf life of silver carp (Hypophthalmicthys molitrix) during storage in ice. Food Chem. 2008, 108, 148–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, W. , Ren, X., Li, Y., & Mao, L. (2019). The beneficial effects of grape seed, sage and oregano extracts on the quality and volatile flavor component of hairtail fish balls during cold storage at 4 °C. LWT - Food Science and Technology, 101, 25-31.

- Ye, T.; Chen, X.; Chen, Z.; Liu, R.; Wang, Y.; Lin, L.; Lu, J. Quality characteristics of shucked crab meat ( Eriocheir sinensis ) processed by high pressure during superchilled storage. J. Food Biochem. 2021, 45, e13708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sae-Leaw, T.; Buamard, N.; Vate, N.K.; Benjakul, S. Effect of Squid Melanin-Free Ink and Pre-Emulsification on Properties and Stability of Surimi Gel Fortified with Seabass Oil during Refrigerated Storage. J. Aquat. Food Prod. Technol. 2018, 27, 919–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solo-De-Zaldívar, B.; Tovar, C.; Borderías, A.; Herranz, B. Pasteurization and chilled storage of restructured fish muscle products based on glucomannan gelation. Food Hydrocoll. 2015, 43, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.; You, J.; Xiong, S.; Yin, T. Short-term frozen storage enhances cross-linking that was induced by transglutaminase in surimi gels from silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix). Food Chem. 2018, 257, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulu, H. Evaluation of three 2-thiobarbituric acid methods for the measurement of lipid oxidation in various meats and meat products. Meat Sci. 2004, 67, 683–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Effect on storage loss (%) of the cooked silver carp surimi batters were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage. C1, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 1st day; C4, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 4th day; C7, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 7th day; T1, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 1st day; T4, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 4th day; T7, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 7th day. Each value represents the mean ± SD, n = 4. a-d Different parameter superscripts in the figure indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Effect on storage loss (%) of the cooked silver carp surimi batters were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage. C1, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 1st day; C4, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 4th day; C7, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 7th day; T1, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 1st day; T4, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 4th day; T7, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 7th day. Each value represents the mean ± SD, n = 4. a-d Different parameter superscripts in the figure indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Effect on pH of the cooked silver carp surimi batters were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage. C1, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 1st day; C4, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 4th day; C7, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 7th day; T1, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 1st day; T4, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 4th day; T7, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 7th day. Each value represents the mean ± SD, n = 4. a-d Different parameter superscripts in the figure indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Effect on pH of the cooked silver carp surimi batters were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage. C1, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 1st day; C4, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 4th day; C7, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 7th day; T1, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 1st day; T4, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 4th day; T7, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 7th day. Each value represents the mean ± SD, n = 4. a-d Different parameter superscripts in the figure indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Effect on the whiteness of the cooked silver carp surimi batters were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage. C1, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 1st day; C4, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 4th day; C7, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 7th day; T1, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 1st day; T4, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 4th day; T7, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 7th day. Each value represents the mean ± SD, n = 4. a-d Different parameter superscripts in the figure indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Effect on the whiteness of the cooked silver carp surimi batters were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage. C1, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 1st day; C4, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 4th day; C7, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 7th day; T1, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 1st day; T4, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 4th day; T7, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 7th day. Each value represents the mean ± SD, n = 4. a-d Different parameter superscripts in the figure indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effect on the TBARS (mg MDA/kg) of the cooked silver carp surimi batters were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage. C1, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 1st day; C4, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 4th day; C7, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 7th day; T1, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 1st day; T4, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 4th day; T7, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 7th day. Each value represents the mean ± SD, n = 4. a-c Different parameter superscripts in the figure indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Effect on the TBARS (mg MDA/kg) of the cooked silver carp surimi batters were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage. C1, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 1st day; C4, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 4th day; C7, 0.4 g potassium bicarbonate and stored at the 7th day; T1, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 1st day; T4, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 4th day; T7, 0.3 g potassium bicarbonate, 0.1 g sodium tripolyphosphate, and stored at the 7th day. Each value represents the mean ± SD, n = 4. a-c Different parameter superscripts in the figure indicate significant differences (P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Effect on initial relaxation time (ms) and peak ratio (%) of the cooked silver carp surimi batters were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage.

Table 1.

Effect on initial relaxation time (ms) and peak ratio (%) of the cooked silver carp surimi batters were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage.

| Sample |

Initial relaxation time (ms) |

Peak ratio (%) |

| T2b

|

T21

|

T22

|

P2b

|

P21

|

P22

|

| C1 |

2.32±0.10a

|

46.56±1.26c

|

465.42±12.56c

|

1.38±0.17a

|

90.26±0.87b

|

8.58±0.46d

|

| C4 |

2.41±0.09a

|

57.48±1.18b

|

498.23±11.27b

|

1.42±0.22a

|

86.75±0.76c

|

11.15±0.39c

|

| C7 |

2.47±0.12a

|

68.15±1.30a

|

536.70±12.04a

|

1.50±0.26a

|

81.58±0.93d

|

17.49±0.33a

|

| T1 |

1.92±0.12b

|

35.51±1.27d

|

336.27±12.33e

|

0.96±0.15b

|

93.32±0.91a

|

6.37±0.35e

|

| T4 |

2.07±0.11b

|

47.22±1.31c

|

387.81±11.48d

|

1.04±0.20b

|

90.47±0.83b

|

8.50±0.39d

|

| T7 |

2.11±0.13b

|

55.36±1.23b

|

448.87±12.19c

|

0.99±0.19b

|

85.44±0.95c

|

13.67±0.44b

|

Table 2.

Effect on the texture of the cooked silver carp surimi batters were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage.

Table 2.

Effect on the texture of the cooked silver carp surimi batters were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage.

| Sample |

Hardness (N) |

Springiness |

Cohesiveness |

Chewiness (N.mm) |

| C1 |

47.37±1.27d

|

0.853±0.011c

|

0.613±0.011c

|

24.71±1.27b

|

| C4 |

51.33±1.35c

|

0.827±0.009c

|

0.595±0.007d

|

25.24±1.04b

|

| C7 |

57.25±1.16b

|

0.771±0.012d

|

0.557±0.009e

|

24.58±1.16b

|

| T1 |

53.91±1.13c

|

0.911±0.012a

|

0.670±0.009a

|

31.10±1.21a

|

| T4 |

56.02±1.27b

|

0.880±0.015a

|

0.642±0.010b

|

31.63±1.37a

|

| T7 |

59.87±1.21a

|

0.844±0.010b

|

0.615±0.012c

|

30.92±1.16a

|

Table 3.

Effect on Total volatile basic nitrogen. (mg/100 g) and total plate count (CFU/g) of the cooked silver carp surimi batters were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage.

Table 3.

Effect on Total volatile basic nitrogen. (mg/100 g) and total plate count (CFU/g) of the cooked silver carp surimi batters were made with various amounts of potassium bicarbonate and sodium tripolyphosphate during cold storage.

| Sample |

Total volatile basic nitrogen

(mg/100 g) |

Total plate count (CFU/g) |

| C1 |

3.34±0.32c

|

3.23×10 |

| C4 |

8.50±0.39b

|

6.26×102

|

| C7 |

17.31±0.52a

|

5.31×104

|

| T1 |

3.63±0.44c

|

4.60×10 |

| T4 |

9.30±0.38b

|

5.52×102

|

| T7 |

16.68±0.71a

|

4.63×104

|

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).