Submitted:

30 August 2023

Posted:

31 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

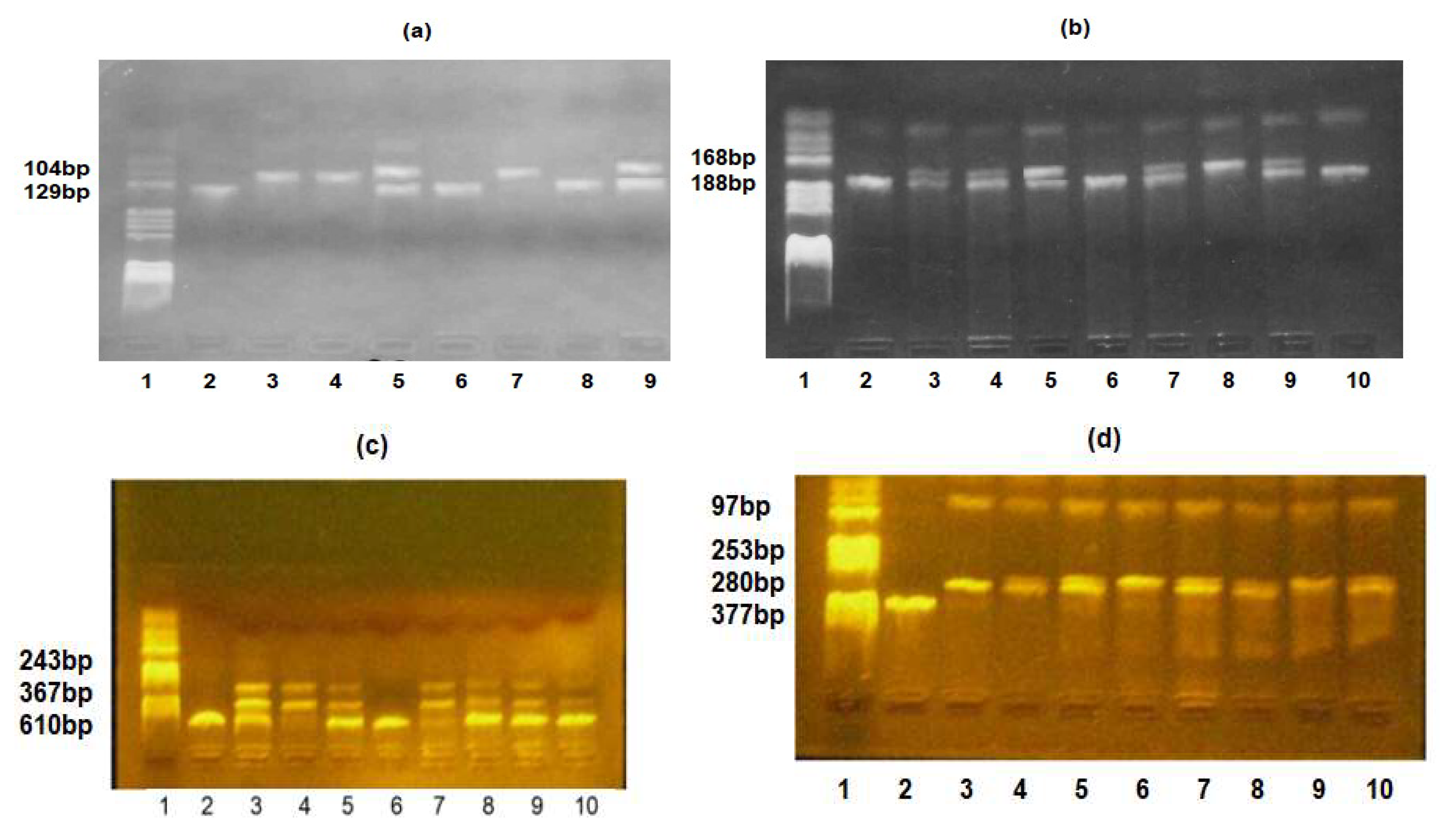

2.1. TLR2-Arg753Gln (rs 5743708), TLR4-Asp299Gly (rs 4986790), IL6-174 G/C (rs 1800795), and IL10-1082G/A (rs 1800896)

2.2. DNA Extraction

2.3. Genotyping Analysis

2.4. PCR Reaction

2.5. RFLP Analysis

2.6. The Studied Groups

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Comparisons of Demographic, Anthropometric, and Clinical Characteristics Between the Two Groups

3.2. Associations of Studied SNPs' Allele Frequencies with Odds of EOS in Premature Neonates

3.3. Association between Studied SNPs' Genotype Frequencies and Odds of EOS in Premature Neonates

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Singh M, Alsaleem M, Gray CP. Neonatal sepsis. StatPearls [Internet]: StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Levy O. Innate immunity of the newborn: basic mechanisms and clinical correlates. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2007;7(5):379-90. [CrossRef]

- Weiss SL, Peters MJ, Alhazzani W, Agus MSD, Flori HR, Inwald DP, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign International Guidelines for the Management of Septic Shock and Sepsis-Associated Organ Dysfunction in Children. Pediatric critical care medicine : a journal of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies. 2020;21(2):e52-e106.

- Emr BM, Alcamo AM, Carcillo JA, Aneja RK, Mollen KP. Pediatric Sepsis Update: How Are Children Different? Surgical infections. 2018;19(2):176-83.

- Iramain R, Ortiz J, Jara A, Bogado N, Morinigo R, Cardozo L, et al. Fluid Resuscitation and Inotropic Support in Patients With Septic Shock Treated in Pediatric Emergency Department: An Open-Label Trial. Cureus. 2022;14(10):e30029. [CrossRef]

- Weiss SL, Balamuth F. Fluid Resuscitation in Children-Better to Be "Normal" or "Balanced"? Pediatric critical care medicine : a journal of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the World Federation of Pediatric Intensive and Critical Care Societies. 2022;23(3):222-4.

- Kumagai Y, Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pathogen recognition by innate receptors. Journal of Infection and Chemotherapy. 2008;14(2):86-92. [CrossRef]

- Wynn JL, Wong HR. Pathophysiology of neonatal sepsis. Fetal and Neonatal Physiology. 2017:1536. [CrossRef]

- Benitz WE, Gould JB, Druzin ML. Risk factors for early-onset group B streptococcal sepsis: estimation of odds ratios by critical literature review. Pediatrics. 1999;103(6):e77-e. [CrossRef]

- Yancey MK, Duff P, Kubilis P, Clark P, Frentzen BH. Risk factors for neonatal sepsis. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1996;87(2):188-94. [CrossRef]

- Stoll BJ, Hansen N, Fanaroff AA, Wright LL, Carlo WA, Ehrenkranz RA, et al. Late-onset sepsis in very low birth weight neonates: the experience of the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics. 2002;110(2):285-91. [CrossRef]

- Anderson DC, Rothlein R, Marlin SD, Krater SS, Smith CW. Impaired transendothelial migration by neonatal neutrophils: abnormalities of Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18)-dependent adherence reactions. 1990.

- Sriskandan S, Altmann D. The immunology of sepsis. The Journal of Pathology: A Journal of the Pathological Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 2008;214(2):211-23.

- Xiao W, Mindrinos MN, Seok J, Cuschieri J, Cuenca AG, Gao H, et al. A genomic storm in critically injured humans. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2011;208(13):2581-90. [CrossRef]

- Hensler E, Petros H, Gray CC, Chung C-S, Ayala A, Fallon EA. The Neonatal Innate Immune Response to Sepsis: Checkpoint Proteins as Novel Mediators of This Response and as Possible Therapeutic/Diagnostic Levers. Frontiers in immunology. 2022;13:940930. [CrossRef]

- Hensler E, Petros H, Gray CC, Chung CS, Ayala A, Fallon EA. The Neonatal Innate Immune Response to Sepsis: Checkpoint Proteins as Novel Mediators of This Response and as Possible Therapeutic/Diagnostic Levers. Frontiers in immunology. 2022;13:940930. [CrossRef]

- Kawai T, Akira S. The roles of TLRs, RLRs and NLRs in pathogen recognition. Int Immunol. 2009;21(4):317-37. [CrossRef]

- Pace E, Yanowitz T, editors. Infections in the NICU: Neonatal sepsis. Seminars in pediatric surgery; 2022: Elsevier.

- Zhang J, Zhou J, Xu B, Chen C, Shi W. Different expressions of TLRs and related factors in peripheral blood of preterm infants. International journal of clinical and experimental medicine. 2015;8(3):4108.

- Sadeghi K, Berger A, Langgartner M, Prusa A-R, Hayde M, Herkner K, et al. Immaturity of infection control in preterm and term newborns is associated with impaired toll-like receptor signaling. The Journal of infectious diseases. 2007;195(2):296-302. [CrossRef]

- Kagan JC, Medzhitov R. Phosphoinositide-mediated adaptor recruitment controls Toll-like receptor signaling. Cell. 2006;125(5):943-55. [CrossRef]

- Angus DC, Burgner D, Wunderink R, Mira J-P, Gerlach H, Wiedermann CJ, et al. The PIRO concept: P is for predisposition. BioMed Central; 2003. [CrossRef]

- Bochud P-Y, Chien JW, Marr KA, Leisenring WM, Upton A, Janer M, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 polymorphisms and aspergillosis in stem-cell transplantation. New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;359(17):1766-77.

- Faber J, Meyer CU, Gemmer C, Russo A, Finn A, Murdoch C, et al. Human toll-like receptor 4 mutations are associated with susceptibility to invasive meningococcal disease in infancy. The Pediatric infectious disease journal. 2006;25(1):80-1. [CrossRef]

- Mockenhaupt FP, Cramer JP, Hamann L, Stegemann MS, Eckert J, Oh N-R, et al. Toll-like receptor (TLR) polymorphisms in African children: common TLR-4 variants predispose to severe malaria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103(1):177-82. [CrossRef]

- Schröder NW, Schumann RR. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of Toll-like receptors and susceptibility to infectious disease. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2005;5(3):156-64.

- Hu L, Tao H, Tao X, Tang X, Xu C. TLR2 Arg753Gln gene polymorphism associated with tuberculosis susceptibility: an updated meta-analysis. BioMed research international. 2019;2019. [CrossRef]

- Xiong Y, Song C, Snyder GA, Sundberg EJ, Medvedev AE. R753Q polymorphism inhibits Toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 tyrosine phosphorylation, dimerization with TLR6, and recruitment of myeloid differentiation primary response protein 88. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287(45):38327-37. [CrossRef]

- Gao JW, Zhang AQ, Wang X, Li ZY, Yang JH, Zeng L, et al. Association between the TLR2 Arg753Gln polymorphism and the risk of sepsis: a meta-analysis. Critical care (London, England). 2015;19:416. [CrossRef]

- Karananou P, Tramma D, Katafigiotis S, Alataki A, Lambropoulos A, Papadopoulou-Alataki E. The Role of TLR4 Asp299Gly and TLR4 Thr399Ile Polymorphisms in the Pathogenesis of Urinary Tract Infections: First Evaluation in Infants and Children of Greek Origin. J Immunol Res. 2019;2019:6503832. [CrossRef]

- Balistreri CR, Colonna-Romano G, Lio D, Candore G, Caruso C. TLR4 polymorphisms and ageing: implications for the pathophysiology of age-related diseases. Journal of clinical immunology. 2009;29:406-15. [CrossRef]

- Chen R, Gu N, Gao Y, Cen W. TLR4 Asp299Gly (rs4986790) polymorphism and coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis. PeerJ. 2015;3:e1412. [CrossRef]

- Chatzi M, Papanikolaou J, Makris D, Papathanasiou I, Tsezou A, Karvouniaris M, et al. Toll-like receptor 2, 4 and 9 polymorphisms and their association with ICU-acquired infections in Central Greece. Journal of Critical Care. 2018;47:1-8. [CrossRef]

- Palmiere C, Augsburger M. Markers for sepsis diagnosis in the forensic setting: state of the art. Croatian Medical Journal. 2014;55(2):103. [CrossRef]

- Hu P, Chen Y, Pang J, Chen X. Association between IL-6 polymorphisms and sepsis. Innate immunity. 2019;25(8):465-72. [CrossRef]

- Gao J-w, Zhang A-q, Pan W, Yue C-l, Zeng L, Gu W, et al. Association between IL-6-174G/C polymorphism and the risk of sepsis and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(3):e0118843.

- Michalek J, Svetlikova P, Fedora M, Klimovic M, Klapacova L, Bartosova D, et al. Interleukin-6 gene variants and the risk of sepsis development in children. Human immunology. 2007;68(9):756-60. [CrossRef]

- Mosser DM, Zhang X. Interleukin-10: new perspectives on an old cytokine. Immunological reviews. 2008;226(1):205-18. [CrossRef]

- Rea IM, Gibson DS, McGilligan V, McNerlan SE, Alexander HD, Ross OA. Age and age-related diseases: role of inflammation triggers and cytokines. Frontiers in immunology. 2018:586. [CrossRef]

- Eskdale J, Kube D, Tesch H, Gallagher G. Mapping of the human IL10 gene and further characterization of the 5’flanking sequence. Immunogenetics. 1997;46:120-8. [CrossRef]

- Kang X, Kim HJ, Ramirez M, Salameh S, Ma X. The septic shock-associated IL-10 -1082 A > G polymorphism mediates allele-specific transcription via poly(ADP-Ribose) polymerase 1 in macrophages engulfing apoptotic cells. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md : 1950). 2010;184(7):3718-24. [CrossRef]

- Lee YH, Kim JH, Song GG. Meta-analysis of associations between interleukin-10 polymorphisms and susceptibility to pre-eclampsia. European journal of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive biology. 2014;182:202-7. [CrossRef]

- Ouyang L, Lv Y-D, Hou C, Wu G-B, He Z-H. Quantitative analysis of the association between interleukin-10 1082A/G polymorphism and susceptibility to sepsis. Molecular biology reports. 2013;40:4327-32. [CrossRef]

- Shu Q, Fang X, Chen Q, Stuber F. IL-10 polymorphism is associated with increased incidence of severe sepsis. Chinese medical journal. 2003;116(11):1756-9.

- Mela A, Rdzanek E, Poniatowski Ł A, Jaroszyński J, Furtak-Niczyporuk M, Gałązka-Sobotka M, et al. Economic Costs of Cardiovascular Diseases in Poland Estimates for 2015-2017 Years. Frontiers in pharmacology. 2020;11:1231.

- Mela A, Poniatowski Ł A, Drop B, Furtak-Niczyporuk M, Jaroszyński J, Wrona W, et al. Overview and Analysis of the Cost of Drug Programs in Poland: Public Payer Expenditures and Coverage of Cancer and Non-Neoplastic Diseases Related Drug Therapies from 2015-2018 Years. Frontiers in pharmacology. 2020;11:1123.

- Ben Dhifallah I, Lachheb J, Houman H, Hamzaoui K. Toll-like-receptor gene polymorphisms in a Tunisian population with Behçet's disease. Clinical and experimental rheumatology. 2009;27(2 Suppl 53):S58-62.

- Aker S, Bantis C, Reis P, Kuhr N, Schwandt C, Grabensee B, et al. Influence of interleukin-6 G-174C gene polymorphism on coronary artery disease, cardiovascular complications and mortality in dialysis patients. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation : official publication of the European Dialysis and Transplant Association - European Renal Association. 2009;24(9):2847-51.

- Cordeiro CA, Moreira PR, Andrade MS, Dutra WO, Campos WR, Oréfice F, et al. Interleukin-10 gene polymorphism (-1082G/A) is associated with toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science. 2008;49(5):1979-82. [CrossRef]

- R Core Team A, Team RC. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2012. 2022.

- Roth GA, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, et al. Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet. 2018;392(10159):1736-88. [CrossRef]

- Baizat IM, Zaharie CG, Hasmasanu M, Matyas M, Procopciuc LM. Is it possible to use the Toll-like receptors as biomarkers for neonatal sepsis? Review of the recent literature. Romanian Journal of Pediatrics. 2022;71(3).

- Nachtigall I, Tamarkin A, Tafelski S, Weimann A, Rothbart A, Heim S, et al. Polymorphisms of the toll-like receptor 2 and 4 genes are associated with faster progression and a more severe course of sepsis in critically ill patients. Journal of international medical research. 2014;42(1):93-110. [CrossRef]

- Behairy MY, Abdelrahman AA, Toraih EA, Ibrahim EE-DA, Azab MM, Sayed AA, et al. Investigation of TLR2 and TLR4 Polymorphisms and Sepsis Susceptibility: Computational and Experimental Approaches. International journal of molecular sciences. 2022;23(18):10982. [CrossRef]

- Sljivancanin Jakovljevic T, Martic J, Jacimovic J, Nikolic N, Milasin J, Mitrović TL. Association between innate immunity gene polymorphisms and neonatal sepsis development: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Pediatrics. 2022;18(10):654-70.

- Krakowska A, Cedzyński M, Wosiak A, Swiechowski R, Krygier A, Tkaczyk M, et al. Toll-like receptor (TLR2, TLR4) polymorphisms and their influence on the incidence of urinary tract infections in children with and without urinary tract malformation. Central European Journal of Immunology. 2022;47(1). [CrossRef]

- Karananou P, Tramma D, Katafigiotis S, Alataki A, Lambropoulos A, Papadopoulou-Alataki E. The role of TLR4 Asp299Gly and TLR4 Thr399Ile polymorphisms in the pathogenesis of urinary tract infections: first evaluation in infants and children of Greek origin. Journal of Immunology Research. 2019;2019. [CrossRef]

- Van Snick, J. Interleukin-6: an overview. Annual review of immunology. 1990;8(1):253-78.

- Fishman D, Faulds G, Jeffery R, Mohamed-Ali V, Yudkin JS, Humphries S, et al. The effect of novel polymorphisms in the interleukin-6 (IL-6) gene on IL-6 transcription and plasma IL-6 levels, and an association with systemic-onset juvenile chronic arthritis. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1998;102(7):1369-76. [CrossRef]

- Vivas MC, Villamarín-Guerrero HF, Sanchez CA. Interleukin-10 (IL-10) 1082 promoter Polymorphisms and plasma IL-10 levels in patients with bacterial sepsis. Romanian Journal of Internal Medicine. 2021;59(1):50-7. [CrossRef]

- Moore, C. Jacobson, S. genpwr: Power Calculations under Genetic Model Misspecification. R package version. 2021;1(4).

| Genetic Variation | Primers’ Sequences |

|---|---|

| TLR2-Arg753Gln | FW: 5′-CAT TCC CCA GCG CTT CTG CAA GCT CC-3′ |

| RV: 5′-GGA ACC TAG GAC TTT ATC GCA GCT C-3′ | |

| TLR4-Asp299Gly | FW: 5′-GAT TAG CAT ACT TAG ACT ACT ACC TCC ATG-3′ |

| RV: 5′-GAT CAA CTT CTG AAA AAG CAT TCC CAC-3′ | |

| IL6-174G/C | FW: 5′-CAG AAG AAC TCA GAT GAC TGG-3′ |

| RV: 5′-GCT GGG CTC CTG GAG GGG-3′ | |

| IL10-1082G/A | FW: 5′-CCA AGA CAA CAC TAC TAA GGC TCC TTT-3′ |

| RV: 5′-GCT TCT TAT ATG CTA GTC AGG TA-3′ |

| Postnatal Variables | Preterm Neonates without EOS (n1 = 10) | Preterm Neonates with EOS (n2 = 26) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | 0.836 a | ||

| Female | 5 (50.0) | 14 (53.8) | |

| Male | 5 (50.0) | 12 (46.2) | |

| Gestational age, w | 0.00002 b | ||

| Min.–max. | 29–34 | 25–34 | |

| Mean (SD) | 32.6 (1.1) | 29.4 (2.8) | |

| Delivery way, n (%) | 1.000 a | ||

| Vaginal | 7 (70.0) | 19 (73.1) | |

| Cesarean | 3 (30.0) | 7(26.9) | |

| Birth weight, g | 0.00031 b | ||

| Min.–max. | 1490–2600 | 650–2470 | |

| Mean (SD) | 1984.0 (376.9) | 1342.1 (446.5) | |

| Neonate length (cm) | 0.0005 b | ||

| Min.–max. | 37–47 | 26–48 | |

| Mean (SD) | 43.3 (2.9) | 37.4 (6.4) | |

| Head circumference (cm) | 0.0004 b | ||

| Min.–max. | 27–34 | 20–32 | |

| Mean (SD) | 30.2 (1.8) | 26.5 (2.7) | |

| Apgar 1 min | |||

| Median (IQR) | 9 [7, 9] | 6 [4, 7] | 0.00009 d |

| Apgar 5 min | |||

| Median (IQR) | 9 [8, 9] | 8 [7, 8] | 0.00004 d |

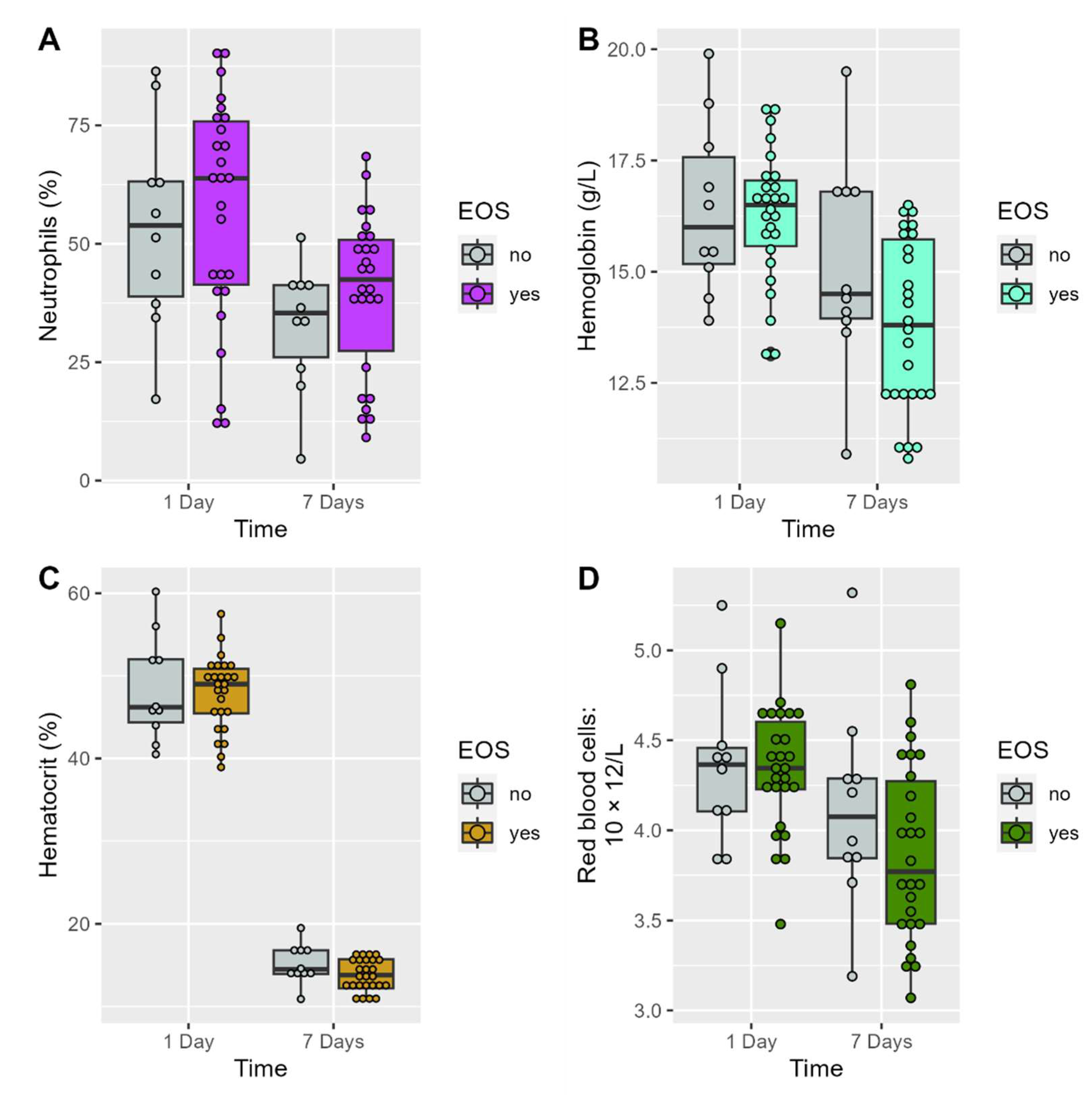

| Variables | Groups | On First Day | At 7 Days | p-Value Time Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBC (mm3), mean (SD) |

Non-EOS | 12,785 [10,140, 15,292.5] |

10,455 [8742.5, 11,475.0] |

0.1309 |

| EOS | 11,985 [8145, 16,090] |

12,285 [9026.3, 16,942.5] |

0.5009 | |

| p-value between groups | 0.6894 | 0.2411 | ||

| Neutrophils (%), mean (SD) | Non-EOS | 53.6 (21.6) | 32.7 (13.4) | 0.0354 * |

| EOS | 56.8 (23.8) | 39.6 (16.9) | 0.0126 * | |

| p-value between groups | 0.7068 | 0.2588 | ||

| Platelets (mm3), mean (SD) |

Non-EOS | 280.2 [46.2) | 366.5 (70.9) | 0.0031 * |

| EOS | 236.5 (78.2) | 345.6 (155.8) | 0.0004 * | |

| p-value between groups | 0.1077 | 0.5855 | ||

| Red blood cells: 10 × 12/L, mean (SD) |

Non-EOS | 4.4 (0.4) | 4.1 (0.6) | 0.0524 |

| EOS | 4.3 (0.3) | 3.9 (0.5) | 0.00007 * | |

| p-value between groups | 0.8422 | 0.1834 | ||

| Hemoglobin (g/L), | Non-EOS | 16.4 (1.9) | 15.1 (2.4) | 0.0227 * |

| mean (SD) | EOS | 16.3 (1.5) | 13.8 (1.9) | 0.000001 * |

| p-value between groups | 0.7927 | 0.08615 | ||

| Hematocrit (%), mean (SD) |

Non-EOS | 48.4 (6.4) | 44.9 (7.4) | 0.0488 * |

| EOS | 47.9 (4.5) | 41.3 (5.7) | 0.000002 * | |

| p-value between groups | 0.828 | 0.1261 | ||

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL), median (IQR) | Non-EOS | 0.30 [0.09, 0.4] | 0.09 [0.08, 0.11] | 0.0580 |

| EOS | 0.80 [0.3, 1.2] | 0.14 [0.06, 0.38] | 0.0435 * | |

| p-value between groups | 0.0099 | 0.1417 |

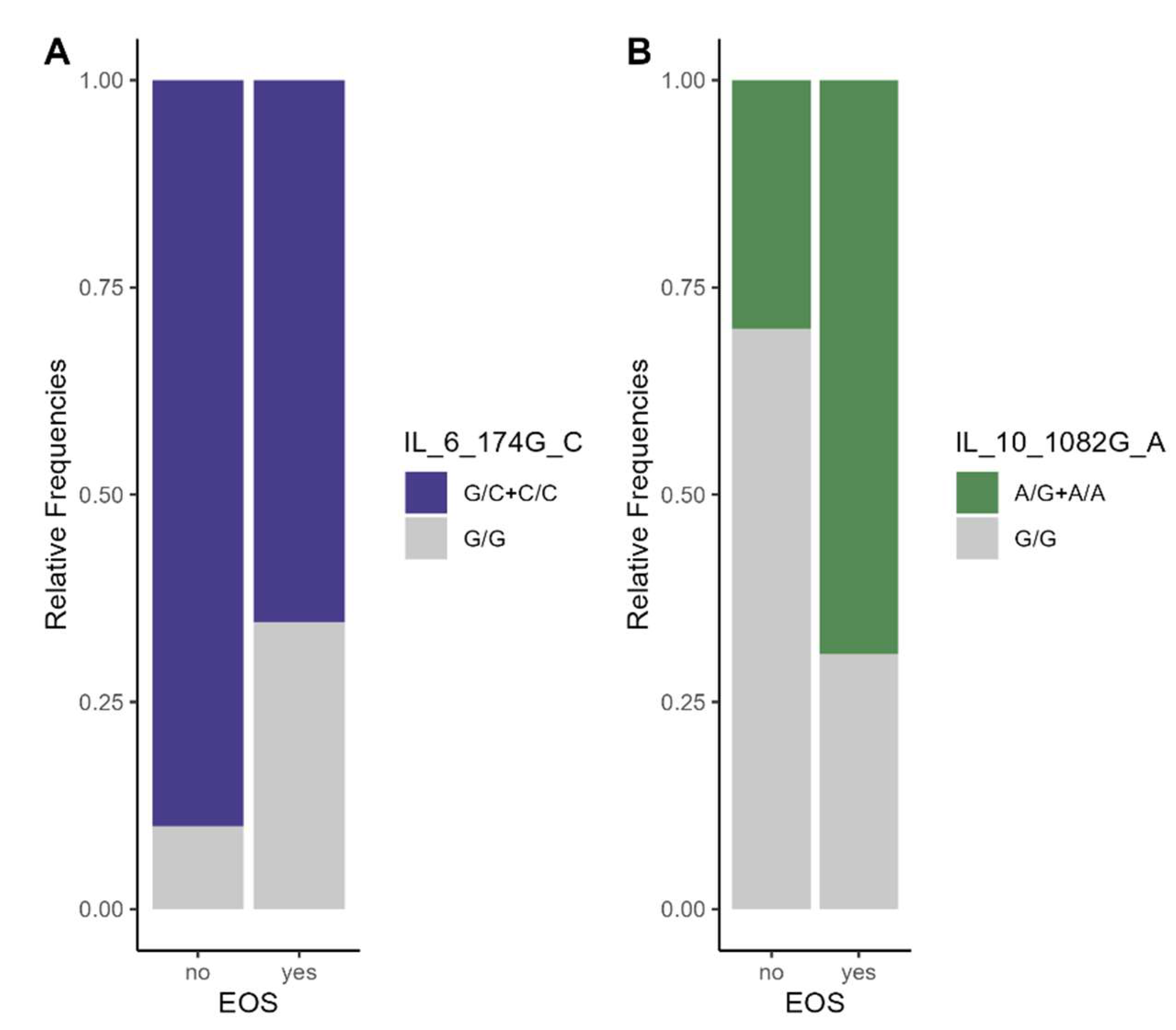

| SNPs | Position | Locus | MA | fEOS | fnon EOS | HWE p-Value a | OR (95% CI) |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLR4-Asp299Gly | 9q32-q33 | 299 | Gly | 0.1538 | 0.2000 | 0.3065 | 0.72 [0.19, 3.12] |

0.6379 |

| TLR2- Arg753Gln | 4q32 | 753 | Gln | 0.3269 | 0.2500 | 0.4799 | 1.46 [0.46, 5.11] |

0.5257 |

| IL6-174G/C | 7p21 | −174 | C | 0.3269 | 0.5000 | 0.1998 | 0.49 [0.17, 1.43] |

0.1742 |

| IL10-1082G/A | 1q31-q32 | 1082 | A | 0.5000 | 0.2500 | 0.0464 | 2.91 [0.96, 10.28] |

0.0550 |

| SNP | Model of Inheritance | Genotype | Non-EOS Group n (%) |

EOS Group n (%) |

OR (95% CI) | p-Value a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TLR4 Asp299Gly |

Co-dominant | Asp/Asp | 7 (70.0) | 20 (76.9) | 1 [Reference] | 0.9138 |

| Asp/Gly | 2 (20.0) | 4 (15.4) | 0.70 [0.10, 4.69] | |||

| Gly/Gly | 1 (10.0) | 2 (7.7) | 0.70 [0.05, 8.97] | |||

| Dominant | Asp/Asp | 7 (70.0) | 20 (76.9) | 1 [Reference] | 0.6712 | |

| Asp/Gly + Gly/Gly | 3 (30.0) | 6 (23.1) | 0.70 [0.14, 3.58] | |||

| Recessive | Asp/Asp − Asp/Gly | 9 (90.0) | 24 (92.3) | 1 [Reference] | 0.8254 | |

| Gly/Gly | 1 (10.0) | 2 (7.7) | 0.75 [0.06, 9.32] | |||

| Log-additive | - | - | - | 0.80 [0.26, 2.45] | 0.6955 | |

| TLR2 Arg753Gln |

Co-dominant | Arg/Arg | 6 (60.0) | 13 (50.0) | 1 [Reference] | 0.8430 |

| Arg/Gln | 3 (30.0) | 9 (34.6) | 1.38 [0.27, 7.04] | |||

| Gln/Gln | 1 (10.0) | 4 (15.4) | 1.85 [0.17, 20.26] | |||

| Dominant | Arg/Arg | 6 (60.0) | 13 (50.0) | 1 [Reference] | 0.5892 | |

| Arg/Gln + Gln/Gln | 4 (40.0) | 13 (50.0) | 1.50 [0.34, 6.59] | |||

| Recessive | Arg/Arg + Arg/Gln | 9 (90.0) | 22 (84.6) | 1 [Reference] | 0.6668 | |

| Gln/Gln | 1 (10.0) | 4 (15.4) | 1.64 [0.16, 16.73] | |||

| Log-additive | - | - | - | 1.37 [ 0.47, 3.98] | 0.5591 | |

|

IL6 174G/C |

Co-dominant | G/G | 1 (10.0) | 9 (34.6) | 1 [Reference] | 0.0896 |

| G/C | 8 (80.0) | 17(66.4) | 0.24 [0.03, 2.20] | |||

| C/C | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | ND | |||

| Dominant | G/G | 1 (10.0) | 9 (34.6) | 1 [Reference] | 0.1140 | |

| G/C + C/C | 9 (90.0) | 17 (65.4) | 0.21 [0.02, 1.93] | |||

| Recessive | G/G + G/C | 9 (90.0) | 26 (100.0) | 1 [Reference] | 0.2778 | |

| C/C | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | ND | |||

| Log-additive | - | - | - | 0.16 [0.02, 1.36] | 0.0896 | |

|

IL10 1082G/A |

Co-dominant | G/G | 7 (70.0) | 8 (30.8) | 1 [Reference] | 0.0779 |

| A/G | 1 (10.0) | 10(38.5) | 8.75 [0.88, 86.57] | |||

| A/A | 2 (20.0) | 8 (30.8) | 3.50 [0.55, 22.30] | |||

| Dominant | G/G | 7 (70.0) | 8 (30.8) | 1 [Reference] | 0.0322 * | |

| A/G + A/A | 3 (30.0) | 18 (69.2) | 5.25 [1.07, 25.70] | |||

| Recessive | G/G + A/G | 8 (80.0) | 18 (69.2) | 1 [Reference] | 0.5091 | |

| A/A | 2 (20.0) | 8 (30.8) | 1.78 [ 0.31, 10.32] | |||

| Log-additive | - | - | - | 2.27 [0.82, 6.30] | 0.0925 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).