Submitted:

30 August 2023

Posted:

31 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Problem Statement and Contributions

4. Material and Methods

4.1. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN):

- Convolution layer: In the CNN architecture, this is the most basic and crucial element. The primary goal of it is to identify and extract local feature sets from an input image, . Let the image database is divided into training () and testing databases , where {. The training samples are represented as , where n denotes the training image database size. For each given input image, the resulting output image is where signifies the class number. Convolutional layer consists of a kernel filter that going through each pixel of the input image as . The local feature set is obtained based on the following equation:where denotes the output feature map for that particular layer, are the trainable parameters for layer, is the activation function.

4.1.1. Pre-trained CNN models

- Inception-V3: The two essential components of Inception-V3 are feature extraction and classification. It is trained using the ImageNet database. Using inception units, Inception-framework V3’s can increase a network’s depth and width while also reducing its computing load.

- Inception-ResNet-V2: The development of Inception-V3, Inception-ResNet-V2 is likewise trained using the ImageNet database. It combines the ResNet module and inception. The other connections enable bypass in the model, which strengthens the network. The computational prowess of the inception units and the optimization leverage provided by the residual connections are combined in Inception-ResNet-V2.

- DenseNet-201: The ImageNet database is also used to train DenseNet-201. It is built on an advanced connectivity scheme that continuously integrates all of the output properties in a feed-forward manner. Further, it strengthens feature propagation, decreases the number of input and functional parameters, and mitigates the vanishing-gradient problem.

4.1.2. Datasets

- It consists of 200 RGB images, divided in between 160 benign and 40 melanoma image samples. Database is maintained by by the Hospital Pedro Hispano, Matsinhos through a clinical observation using dermoscope. The real physicians response is also provided, i.e. normal, melanoma or typical nevus.

- ISIC-MSK: The other database incorporated here, is the International Skin Imaging Collaboration (ISIC). It includes 225 RGB dermoscopic image samples obtained from different well-reputed international cancer institutes captures by various modalities.

- ISIC-UDA: is another dataset publicly accessible for characterization and study of skin cancer (total images: 2750, training images: 2200 testing samples: 550). It contains three cancer types: melanoma, keratosis and benign; but, since keratosis is a fairly common benign skin indication, the images can be divided into two classes: malignant and benign.

4.2. Proposed framework

4.2.1. Transfer Learning

4.2.2. Feature fusion

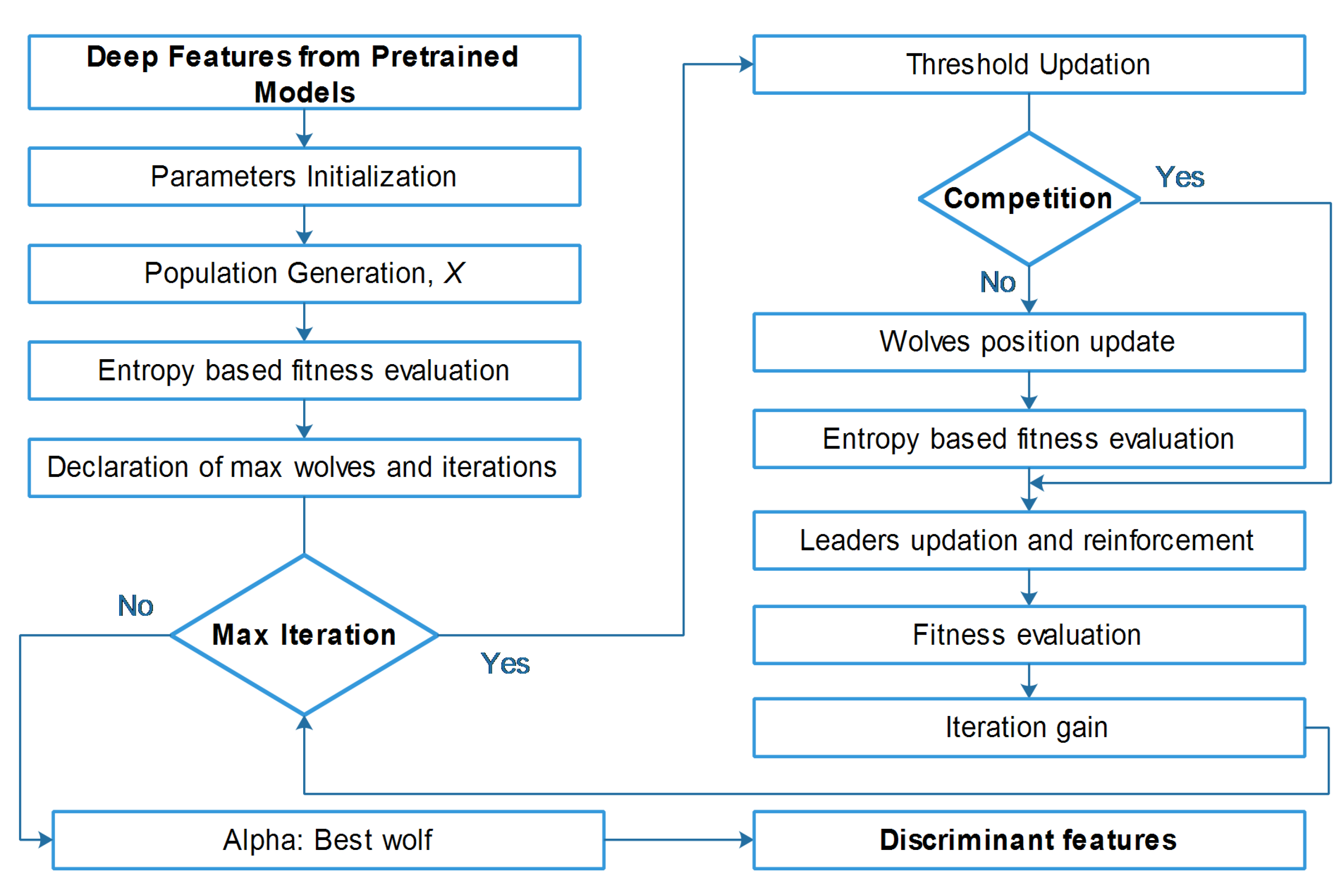

4.2.3. Entropy-Controlled grey wolf optimization

5. Results and Analysis

6. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amazon, E. Instances [WWW Document](2015). URL http://aws. amazon. com/ec2/instance-types (Accessed 06 July 2015).

- Ajmal, M.; Khan, M.A.; Akram, T.; Alqahtani, A.; Alhaisoni, M.; Armghan, A.; Althubiti, S.A.; Alenezi, F. BF2SkNet: Best deep learning features fusion-assisted framework for multiclass skin lesion classification. Neural Computing and Applications 2022, pp. 1–17.

- Akram, T.; Lodhi, H.M.J.; Naqvi, S.R.; Naeem, S.; Alhaisoni, M.; Ali, M.; Haider, S.A.; Qadri, N.N. A multilevel features selection framework for skin lesion classification. Human-centric Computing and Information Sciences 2020, 10, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimkhani, C.; Green, A.C.; Nijsten, T.; Weinstock, M.A.; Dellavalle, R.P.; Naghavi, M.; Fitzmaurice, C. The global burden of melanoma: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. British Journal of Dermatology 2017, 177, 134–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foundation, S.C. The Skin Cancer Foundation, 2018. Skin Cancer Information. [WWW Document]. (2018). URL https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/ (accessed 2.17.20).

- Rebecca L. Siegel, Kimberly D. Miller, H.E.F.A.J. Cancer statistics, 2022. A Cancer journal for clinicians 2022, pp. 7–33.

- Cokkinides, V.; Albano, J.; Samuels, A.; Ward, M.; Thum, J. American cancer society: Cancer facts and figures. Atlanta: American Cancer Society, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Society, A.C. Key Statistics for Melanoma Skin Cancer. [WWW Document]. (2022). URL https://www.cancer.org/cancer/melanoma-skin-cancer/about/key-statistics.html/ (accessed 10.17.22).

- Australia), A.G.C. Melanoma of the skin. [WWW Document]. (2022). URL https://www.canceraustralia.gov.au/cancer-types/melanoma/statistics/ (accessed 10.18.22).

- of Health, A.I. ; Welfare. Skin Cancer. [WWW Document]. (2022). URL https://www.aihw.gov.au/ (accessed 10.18.22).

- Marks, R. Epidemiology of melanoma. clinical and experimental dermatology 2000, 25, 459–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rigel, D. S., F. R.J.K.A.W..P.D. ABCDE—an evolving concept in the early detection of melanoma. Archives of dermatology 2005, 141, 1032–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naqvi, S.R.; Akram, T.; Haider, S.A.; Kamran, M. Artificial neural networks based dynamic priority arbitration for asynchronous flow control. Neural Computing and Applications 2018, 29, 627–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haider, S.A.; Naqvi, S.R.; Akram, T.; Kamran, M.; Qadri, N.N. Modeling electrical properties for various geometries of antidots on a superconducting film. Applied Nanoscience 2017, 7, 933–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Tschandl, C. Rosendahl, B.A.G.A.A.B.R.B.e.a. Expert-level diagnosis of nonpigmented skin cancer by combined convolutional neural networks. JAMA Dermatol 2019, 155, 58–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attique Khan, M.; Sharif, M.; Akram, T.; Kadry, S.; Hsu, C.H. A two-stream deep neural network-based intelligent system for complex skin cancer types classification. International Journal of Intelligent Systems 2022, 37, 10621–10649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M. A. Khan, T. Akram, M.S.T.S.K.J.I.L. Construction of saliency map and hybrid set of features for efficient segmentation and classification of skin lesion. Microsc. Res. Tech 2019, 82, 741–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F. Afza, M.A. Khan, M.S.A.R. Microscopic skin laceration segmentation and classification: a framework of statistical normal distribution and optimal feature selection. Microsc. Res. Tech 2019, 82, 1471–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- M.A. Khan, M.Y. Javed, M.S.T.S.A.R. Multi-model deep neu- ral network based features extraction and optimal selection approach for skin lesion classification. In 2019 international conference on computer and information sciences (ICCIS) 2019, pp. 1–7.

- N. Zhang, Y.-.X. Cai, Y.Y.W.Y.T.T.X.L.W.B.B. Skin cancer diagnosis based on optimized convolutional neural network. Artif. Intell. Med. 2020, 102, 101756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, I.; Younus, M.; Walayat, K.; Kakar, M.U.; Ma, J. Automated multi-class classification of skin lesions through deep convolutional neural network with dermoscopic images. Computerized medical imaging and graphics 2021, 88, 101843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harangi, B.; Baran, A.; Hajdu, A. Assisted deep learning framework for multi-class skin lesion classification considering a binary classification support. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2020, 62, 102041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, D.d.A.; Ivo, R.F.; Satapathy, S.C.; Wang, S.; Hemanth, J.; Reboucas Filho, P.P. A new approach for classification skin lesion based on transfer learning, deep learning, and IoT system. Pattern Recognition Letters 2020, 136, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, L.; Feng, D.D.; Fulham, M.; Kim, J. Multi-label classification of multi-modality skin lesion via hyper-connected convolutional neural network. Pattern Recognition 2020, 107, 107502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessert, N.; Sentker, T.; Madesta, F.; Schmitz, R.; Kniep, H.; Baltruschat, I.; Werner, R.; Schlaefer, A. Skin lesion classification using CNNs with patch-based attention and diagnosis-guided loss weighting. IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering 2019, 67, 495–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Z.; Liu, Z.; Zhu, P.; Xue, Y. A GAN-based image synthesis method for skin lesion classification. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2020, 195, 105568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Masni, M.A.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, T.S. Multiple skin lesions diagnostics via integrated deep convolutional networks for segmentation and classification. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine 2020, 190, 105351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessert, N.; Nielsen, M.; Shaikh, M.; Werner, R.; Schlaefer, A. Skin lesion classification using ensembles of multi-resolution EfficientNets with meta data. MethodsX 2020, 7, 100864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, Q.; Cui, H.; Sun, C.; Meng, Z.; Su, R. Cascade knowledge diffusion network for skin lesion diagnosis and segmentation. Applied Soft Computing 2021, 99, 106881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Dey, D.; Munshi, S.; Gorai, S. Extraction of features from cross correlation in space and frequency domains for classification of skin lesions. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2019, 53, 101581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebouças Filho, P.P.; Peixoto, S.A.; da Nóbrega, R.V.M.; Hemanth, D.J.; Medeiros, A.G.; Sangaiah, A.K.; de Albuquerque, V.H.C. Automatic histologically-closer classification of skin lesions. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics 2018, 68, 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serte, S.; Demirel, H. Gabor wavelet-based deep learning for skin lesion classification. Computers in biology and medicine 2019, 113, 103423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moradi, N.; Mahdavi-Amiri, N. Kernel sparse representation based model for skin lesions segmentation and classification. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine 2019, 182, 105038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hameed, N.; Shabut, A.M.; Ghosh, M.K.; Hossain, M.A. Multi-class multi-level classification algorithm for skin lesions classification using machine learning techniques. Expert Systems with Applications 2020, 141, 112961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahbod, A.; Schaefer, G.; Wang, C.; Dorffner, G.; Ecker, R.; Ellinger, I. Transfer learning using a multi-scale and multi-network ensemble for skin lesion classification. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine 2020, 193, 105475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Pang, N.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H. Unlabeled skin lesion classification by self-supervised topology clustering network. Biomedical Signal Processing and Control 2021, 66, 102428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S.; Dey, D.; Munshi, S. Integration of morphological preprocessing and fractal based feature extraction with recursive feature elimination for skin lesion types classification. Computer methods and programs in biomedicine 2019, 178, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Mou, L.; Zhu, X.X.; Mandal, M. Automatic skin lesion classification based on mid-level feature learning. Computerized Medical Imaging and Graphics 2020, 84, 101765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamga, G.A.F.; Bitjoka, L.; Akram, T.; Mbom, A.M.; Naqvi, S.R.; Bouroubi, Y. Advancements in satellite image classification : methodologies, techniques, approaches and applications. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2021, 42, 7662–7722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirjalili, S.; Mirjalili, S.M.; Lewis, A. Grey wolf optimizer. Advances in engineering software 2014, 69, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faris, H.; Aljarah, I.; Al-Betar, M.A.; Mirjalili, S. Grey wolf optimizer: a review of recent variants and applications. Neural computing and applications 2018, 30, 413–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, R.B.; Papa, J.P.; Pereira, A.S.; Tavares, J.M.R. Computational methods for pigmented skin lesion classification in images: review and future trends. Neural Computing and Applications 2018, 29, 613–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ref. | Year | Performance Parameters | Dataset | Remarks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [21] | 2021 | PRC=94.0% AUC=96.4% | ISIC-17,19 | The proposed model has multiple layers and filter sizes; but a fewer number of filters and parameters to classify the skin lesion images. |

| [31] | 2018 | SEN=89.9% SPC=92.1% F1-S=90% Ppv=91.3% | ISIC-17 | An automatic approach to classify melanoma, with the advantage of transforming the structural co-occurence matrix (SCM) in an adaptive feature extractor; that helps the classification process to depend only on the input image as a parameter. |

| [25] | 2019 | SEN=73.3% SPC=96.3% F1-S=85% | HAM | Research has two contributions: first, efficient application of high-resolution image dataset with pre-trained state of the art architecture for classification; Second, high variation faced in the real image database. |

| [26] | 2020 | SEN=83.2% ACC=95.2% SPC=96.6% | ISIC-18 | GAN-based data segmentation approach. The original generator’s style, control and input noise structures are altered by the model. The classifier is generated by a pretrained DCNN using transfer learning method. |

| [23] | 2020 | PRC=92.6%ACC=92.5% F1-S=92% | PH2 | This work presents skin caner lesion classification using transfer learning and CNN (as resource extractors). The method combines twelve CNN models with several different classifiers on PH2 and ISBI-ISIC dataset. |

| [22] | 2020 | SEN=73.7% ACC=92.5% AUC=91.2% Ppv=74.1% | ISIC-17 | Framework divides dermoscopic images with seven classes two possible classes: positive/negative. The DCNN is trained regarding this binary problem. The parameters regarding classification are later used to adjust for the multi-class categorization. |

| [29] | 2021 | SEN=70.0% ACC=88.1% SPC=92.5% AUC=90.5% Ppv=73.8% | ISIC-17 | In propsed framework which is a series of coarse-level segmentation, categorization, and fine-level segmentation networks. The two feature mixing modules are outlined to accommodate the diffused feature set from starting segmentation; and to integrate the related knowledge learned to help fine-level segmentation. |

| [32] | 2019 | SEN=17.0% ACC=79.0% SPC=95.0% AUC=70.0% | ISIC-17 | Seven separate directional sub-bands are created from gabor wavelet-based DCNN.from input images. Later, the output sub-band and input images are passed to eight parallel CNNs. To categorise the skin cancer lesion, the addition rule is used. |

| [33] | 2019 | SEN=96.6% ACC=94.8% SPC=93.3% | ISIC-16 | Kernel sparse representation based method is proposed. A linear classifier and a kernel-based meta-data are both jointly adopted by the discriminative kernel sparse coding technique. |

| [34] | 2020 | SEN=87.2% ACC=92.8% ACC=87.2% | ISIC | A multi-class multi-level classification method focuses on "divide and conquer" is presented. The algorithm is tuned using traditional NN tools and advanced deep learning methodologies. |

| [24] | 2020 | PRC=75.9%SEN=68.2% SPC=84.6% | 7 Point Checklist | The method uses a hyper-connected CNN by adding the visual properties of dermoscopy and clinical skin cancer images, and introducing a deep HcCNN with multi-scale attention block. |

| [27] | 2020 | SEN=75.7%ACC=81.6% SPC=80.6% | ISIC-17 | The framework integrates a skin lesion boundary segment and a multiple skin lesions classification stage. Then a CNN such as inception-v3 is employed. |

| [28] | 2020 | SEN=71.0% AUC=96.0% | ISIC-19 | The Method classifies the skin lesions with the help of statistics of multi-resolution EfficientNets with meta-data; using EfficientNets, SENet, and ResNet WSI. |

| [35] | 2020 | PRC=91.3%ACC=96.3% AUC=98.1% | ISIC-18 | The authors investigated the image size effect in classifying the skin lesion images using pre-trained CNNs. The performance EfficientNetB0 &B1, and SetReNetXt50 has been examined. |

| [36] | 2021 | ACC=80.0% | ISIC-18 | The research uses a Self-supervised Topology Clustering Network (STCN) by transformation invariant model network with modularity clustering algorithm. |

| [37] | 2019 | SEN=91.7% ACC=95.2% SPC=97.9% | ISIC 2016 | A recursive feature rejection based layered structured multi-class image categorization is used. Before the classification, features such as the shape and size, border non uniformity, color and texture of the skin lesion region are extracted. |

| [38] | 2020 | AUC=92.1% | ISIC-17 | The authors proposed a lesion classification method centered on mid-level features. Images are segmented first to identify the regions of interest, then the pre-trained DenseNet and ResNet are employed to extract the feature set. |

| Dataset | Total Images | Training/Validation set | Testing set |

|---|---|---|---|

| PH | 200 | 160 | 40 |

| ISIC MSK-2 | 287 | 201 | 86 |

| ISIC UDA-1 | 387 | 271 | 116 |

| Classifier (selected) | Base parameters |

|---|---|

| Linear SVM | Kernel function: Linear Multi-class method: One-vs-One |

| Effecient L-SVM | Kernel function: Linear Multi-class method: One-vs-One |

| Cubic SVM | Kernel function: Cubic Multi-class method: One-vs-One |

| Fine KNN | Number of neighbours:1 Distance metric: Euclidean Weight: equal, |

| Medium KNN | Number of neighbours: 10 Distance metric: Euclidean Weight: equal |

| Weighted KNN | Number of neighbours: 10 Distance metric: Euclidean Weight: Squared inverse |

| Ensemble-BT | Ensemble method: AdaBoost Learner type: Decision tree Max. split: 20 Number of learners: 30 |

| Ensemble S-KNN | Ensemble method: Subspace Learner type: nearest neighbor Number of learners: 30 |

| Ensemble RUSB | Ensemble method: RUBoost Learner type: decision tree Number of learners: 30 Max. split: 20 |

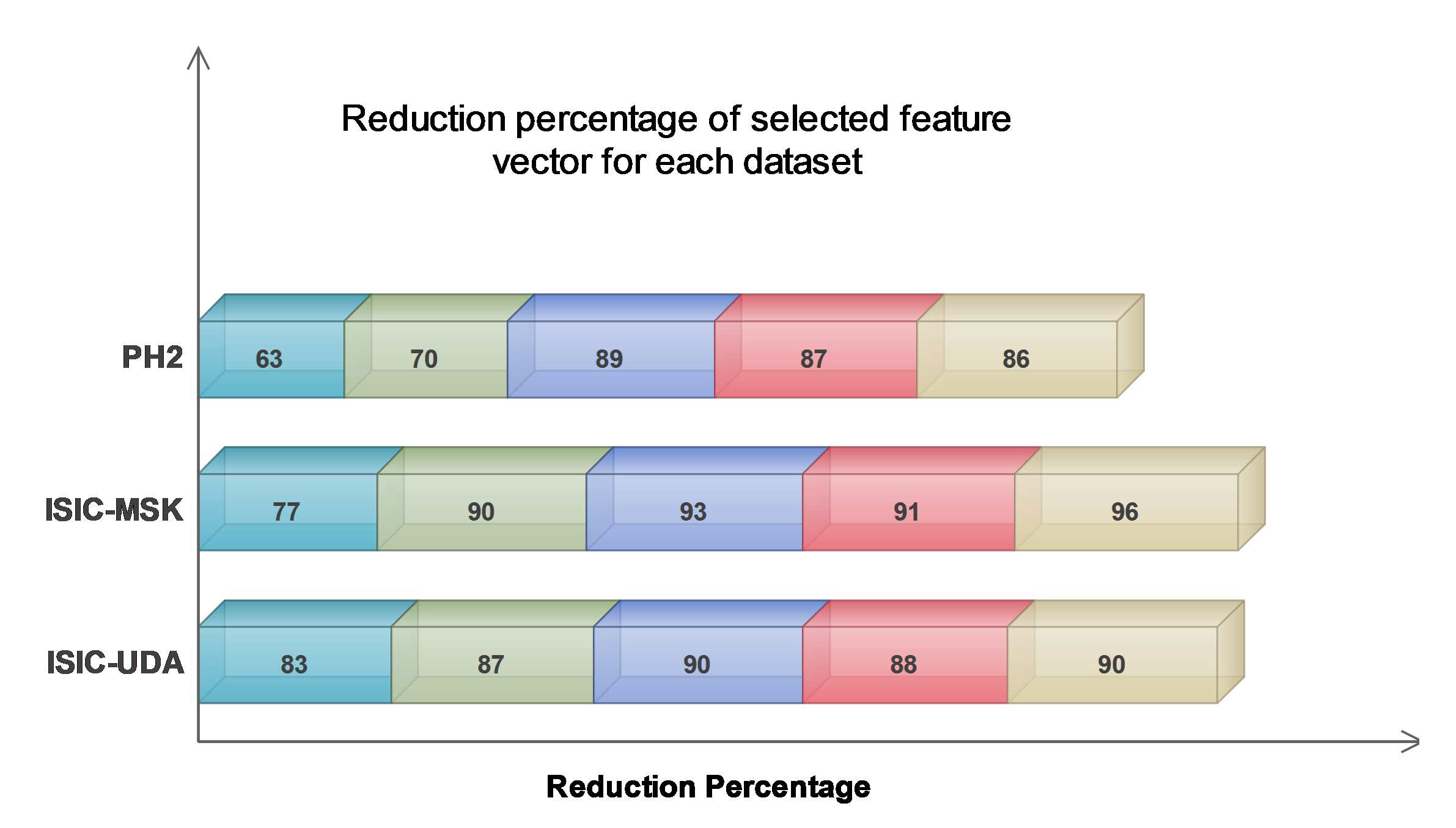

| Vector Fusion | Input Dimension | Output Dimension | Reduction Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PH | |||

| FV2 - FV3 | 140 × 2562 | 140 × 948 | 63 |

| FV3 - FV4 | 140 × 2946 | 140 × 884 | 70 |

| FV2 - FV4 | 140 × 3456 | 140 × 380 | 89 |

| FV2 - FV3 - FV4 | 140 × 4482 | 140 × 583 | 87 |

| FV1 - FV2 - FV3 - FV4 | 140 × 4484 | 140 × 628 | 88 |

| ISIC - MSK | |||

| FV2 - FV3 | 201 × 2562 | 201 × 589 | 77 |

| FV3 - FV4 | 201 × 2946 | 201 × 295 | 90 |

| FV2 - FV4 | 201 × 3456 | 201 × 242 | 93 |

| FV2 - FV3 - FV4 | 201 × 4482 | 201 × 403 | 91 |

| FV1 - FV2 - FV3 - FV4 | 201 × 4484 | 201 × 179 | 96 |

| ISIC - UDA | |||

| FV2 - FV3 | 271 × 2562 | 271 × 436 | 83 |

| FV3 - FV4 | 271 × 2946 | 271 × 383 | 87 |

| FV2 - FV4 | 271 × 3456 | 271 × 346 | 90 |

| FV2 - FV3 - FV4 | 271 × 4482 | 271 × 538 | 88 |

| FV1 - FV2 - FV3 - FV4 | 271 × 4484 | 271 × 448 | 90 |

| Classifier | Dataset | Performance Measures | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | Accuracy (%) | Sensitivity | Specificity | FNR | FPR | F1 Score | |

| Linear SVM | 88.13 | 0.833 | 0.941 | 0.167 | 0.058 | 0.888 | |||

| 85.11 | 0.801 | 0.916 | 0.198 | 0.083 | 0.861 | ||||

| 83.71 | 0.795 | 0.885 | 0.203 | 0.115 | 0.845 | ||||

| Q-SVM | 87.21 | 0.843 | 0.907 | 0.156 | 0.092 | 0.877 | |||

| 97.12 | 0.952 | 0.992 | 0.048 | 0.009 | 0.971 | ||||

| 96.54 | 0.951 | 0.979 | 0.048 | 0.021 | 0.965 | ||||

| Cubic SVM | 88.52 | 0.923 | 0.853 | 0.076 | 0.146 | 0.879 | |||

| 88.27 | 0.905 | 0.866 | 0.094 | 0.133 | 0.882 | ||||

| 87.14 | 0.893 | 0.849 | 0.106 | 0.154 | 0.866 | ||||

| Fine KNN | 98.89 | 0.98 | 0.989 | 0.019 | 0.012 | 0.985 | |||

| 99.01 | 0.985 | 0.994 | 0.014 | 0.005 | 0.994 | ||||

| 97.71 | 0.974 | 0.984 | 0.029 | 0.015 | 0.977 | ||||

| Medium KNN | 94.34 | 0.931 | 0.949 | 0.068 | 0.051 | 0.941 | |||

| 93.18 | 0.921 | 0.938 | 0.078 | 0.061 | 0.930 | ||||

| 90.55 | 0.885 | 0.926 | 0.114 | 0.073 | 0.907 | ||||

| Weighted KNN | 87.15 | 0.862 | 0.876 | 0.137 | 0.124 | 0.871 | |||

| 81.39 | 0.803 | 0.816 | 0.196 | 0.183 | 0.811 | ||||

| 79.64 | 0.792 | 0.798 | 0.207 | 0.202 | 0.796 | ||||

| Ensemble- BT | 73.89 | 0.728 | 0.742 | 0.271 | 0.257 | 0.738 | |||

| 75.24 | 0.745 | 0.755 | 0.254 | 0.244 | 0.752 | ||||

| 77.38 | 0.777 | 0.772 | 0.222 | 0.227 | 0.773 | ||||

| Ensemble S-KNN | 97.58 | 0.978 | 0.979 | 0.029 | 0.025 | 0.975 | |||

| 95.46 | 0.959 | 0.954 | 0.04 | 0.049 | 0.095 | ||||

| 99.09 | 0.986 | 0.994 | 0.013 | 0.006 | 0.993 | ||||

| Ensemble RUSB | 95.76 | 0.952 | 0.961 | 0.047 | 0.038 | 0.957 | |||

| 94.89 | 0.945 | 0.951 | 0.054 | 0.048 | 0.948 | ||||

| 93.57 | 0.932 | 0.939 | 0.069 | 0.063 | 0.935 | ||||

| Vector Fusion | OA (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feature Fusion Approach | Proposed Feature Selection Approach | |||||

| Q-SVM | Fine KNN | ES-KNN | Q-SVM | Fine KNN | ES-KNN | |

| PH | ||||||

| FV2 - FV3 | 84.31 | 74.27 | 74.13 | 86.23 | 88.21 | 81.37 |

| FV3 - FV4 | 79.23 | 78.34 | 81.20 | 88.76 | 86.33 | 88.90 |

| FV2 - FV4 | 81.23 | 81.29 | 79.45 | 84.01 | 88.69 | 87.54 |

| FV2 - FV3 - FV4 | 83.71 | 79.36 | 84.56 | 86.66 | 92.27 | 87.43 |

| FV1 - FV2 - FV3 - FV4 | 83.21 | 85.22 | 87.69 | 87.21 | 98.89 | 97.58 |

| ISIC - MSK | ||||||

| FV2 - FV3 | 74.63 | 82.27 | 78.27 | 79.21 | 81.89 | 87.23 |

| FV3 - FV4 | 76.38 | 83.27 | 81.17 | 83.34 | 81.44 | 89.28 |

| FV2 - FV4 | 76.31 | 79.28 | 76.84 | 81.23 | 87.38 | 84.38 |

| FV2 - FV3 - FV4 | 79.48 | 80.14 | 79.28 | 84.27 | 88.27 | 90.29 |

| FV1 - FV2 - FV3 - FV4 | 81.29 | 81.23 | 83.73 | 97.12 | 99.01 | 95.46 |

| ISIC - UDA | ||||||

| FV2 - FV3 | 77.94 | 79.54 | 81.24 | 85.23 | 85.27 | 87.07 |

| FV3 - FV4 | 76.28 | 81.88 | 82.13 | 84.36 | 88.34 | 89.69 |

| FV2 - FV4 | 81.56 | 83.29 | 84.63 | 88.28 | 91.26 | 84.26 |

| FV2 - FV3 - FV4 | 83.16 | 81.83 | 87.76 | 89.31 | 94.18 | 94.61 |

| FV1 - FV2 - FV3 - FV4 | 89.74 | 86.47 | 87.90 | 96.54 | 97.71 | 99.09 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).