Submitted:

28 August 2023

Posted:

30 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples and preparation

2.2. FTIR analysis

2.3. Thermal analysis

2.4. Kinetic analysis

3. Results and Discussion

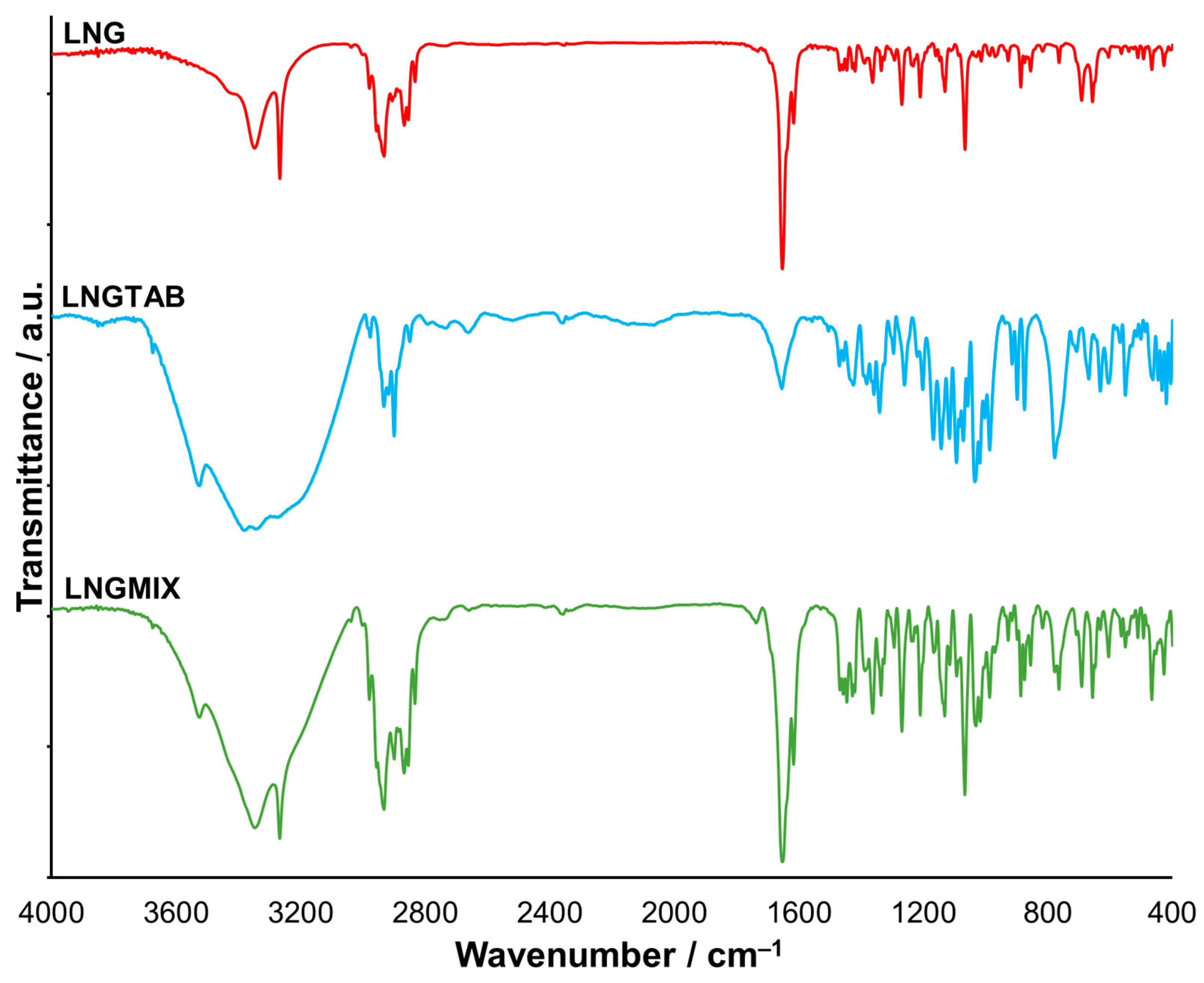

3.1. FTIR analysis

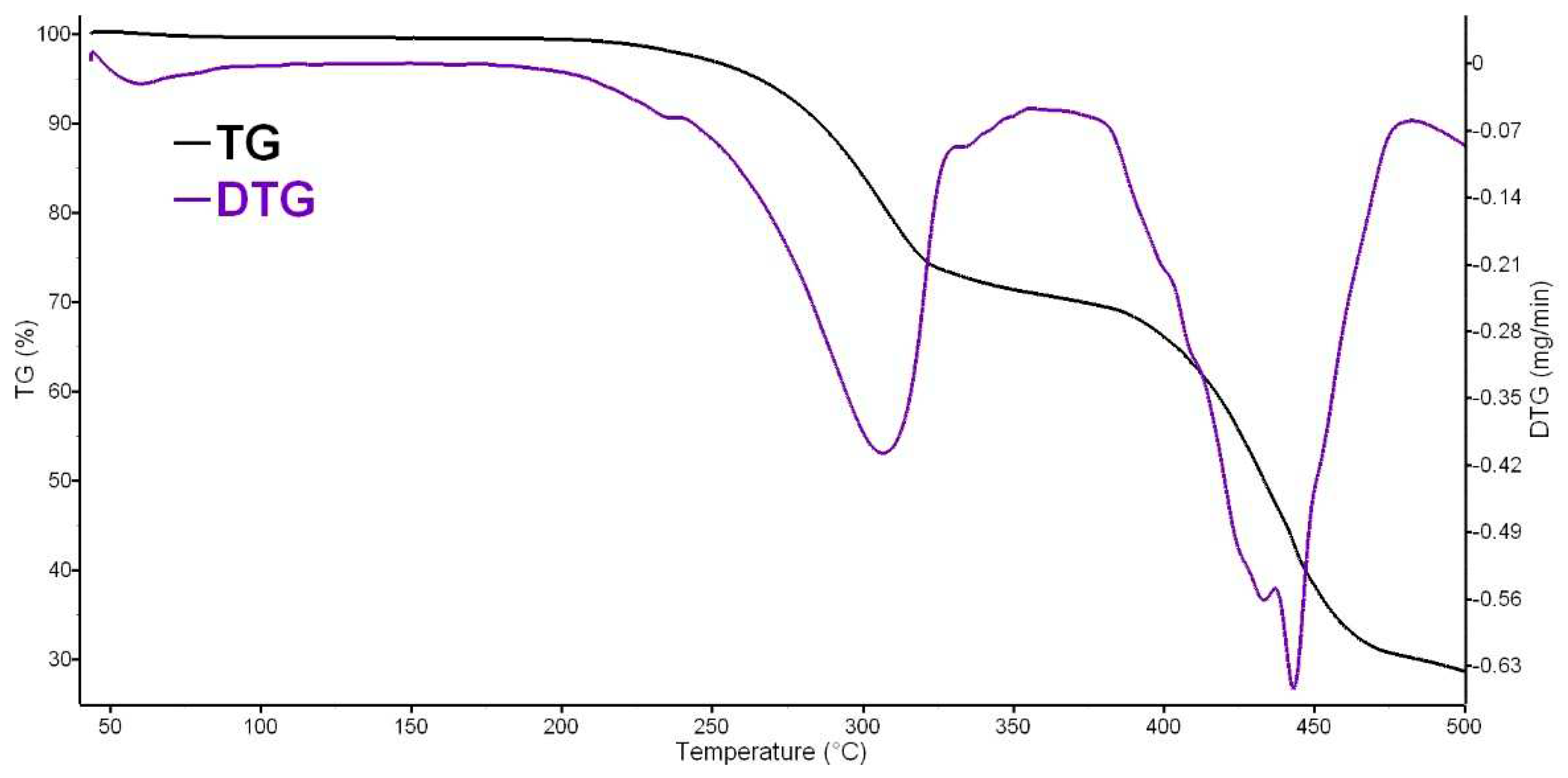

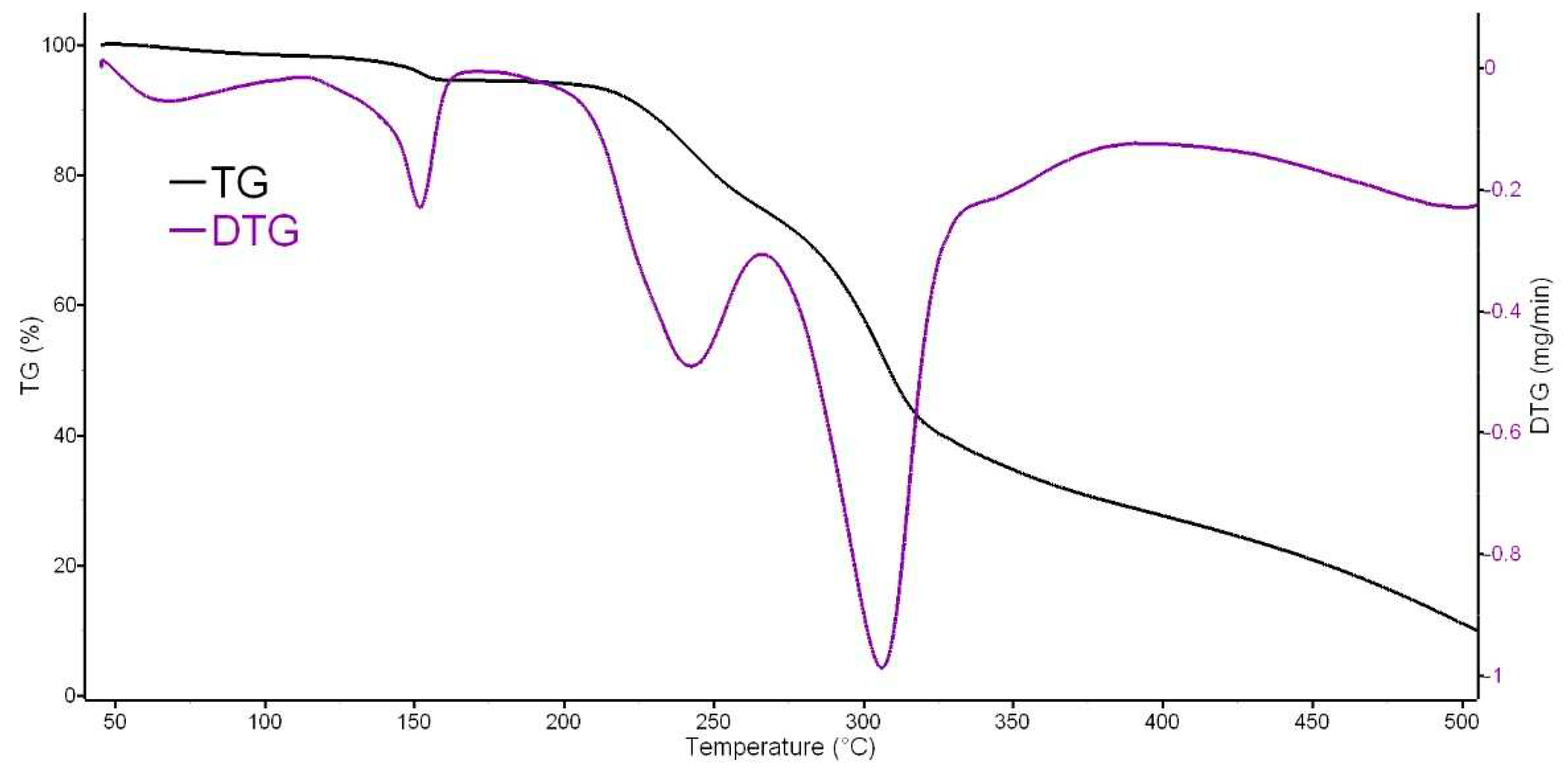

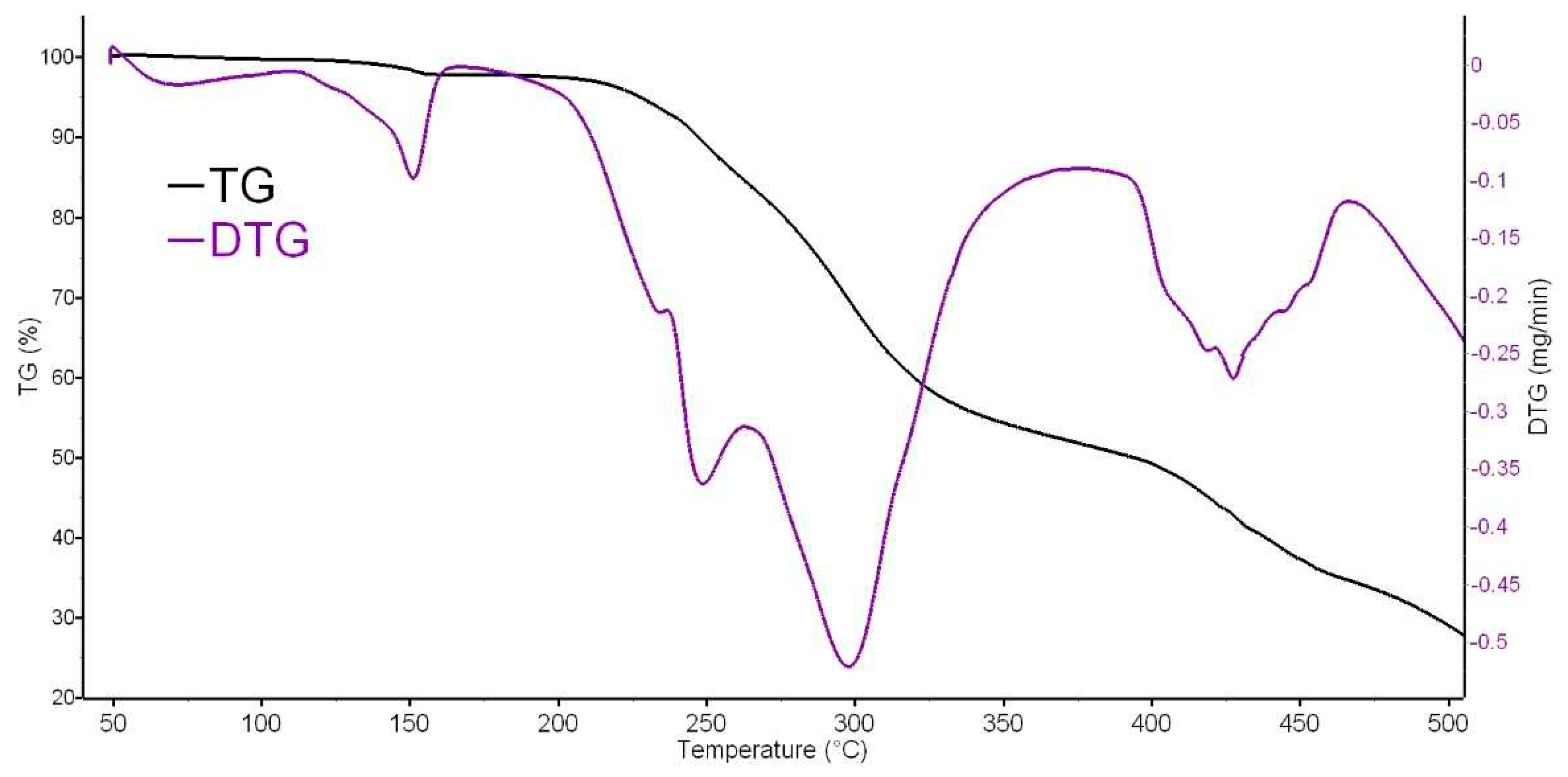

3.2. Thermal analysis

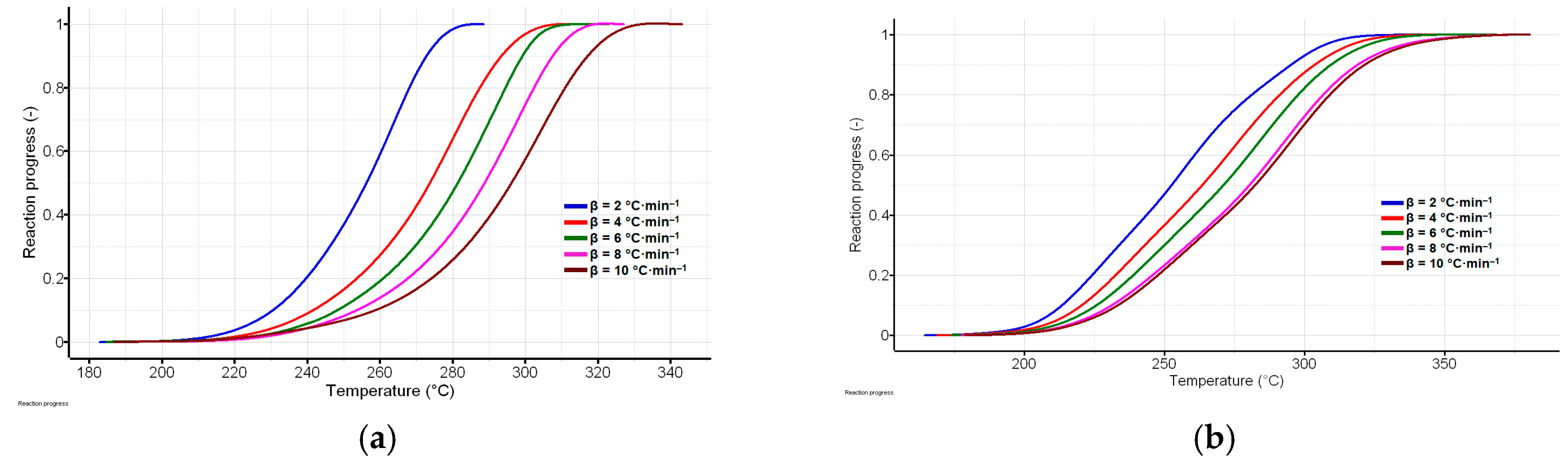

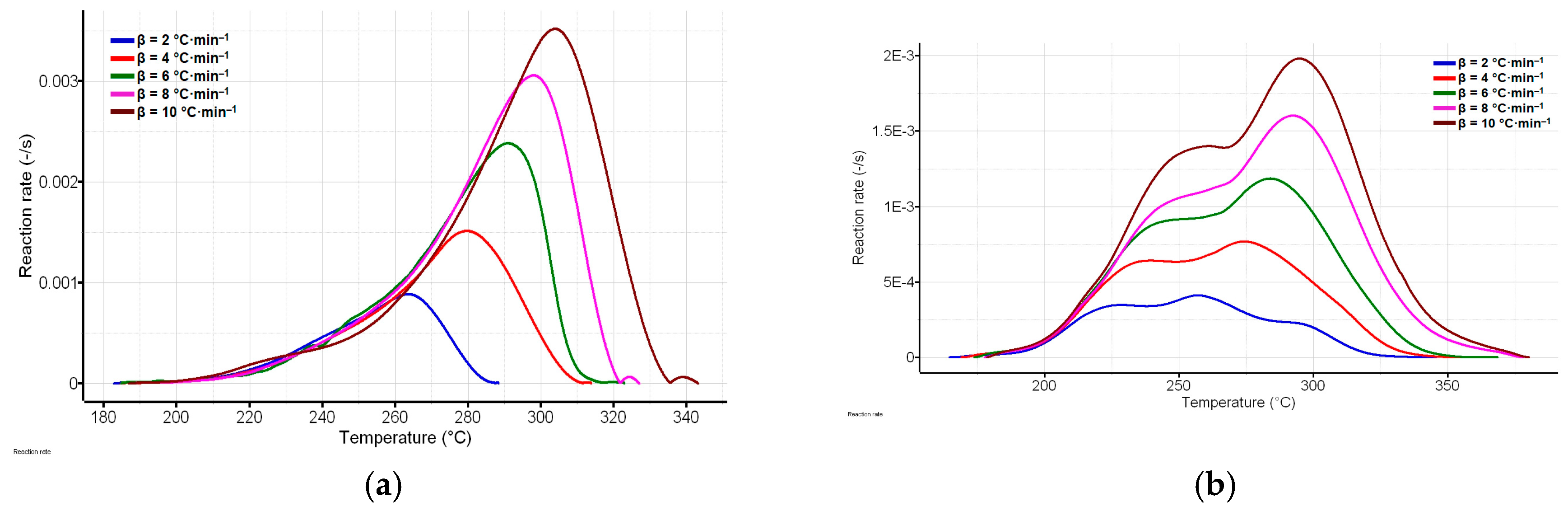

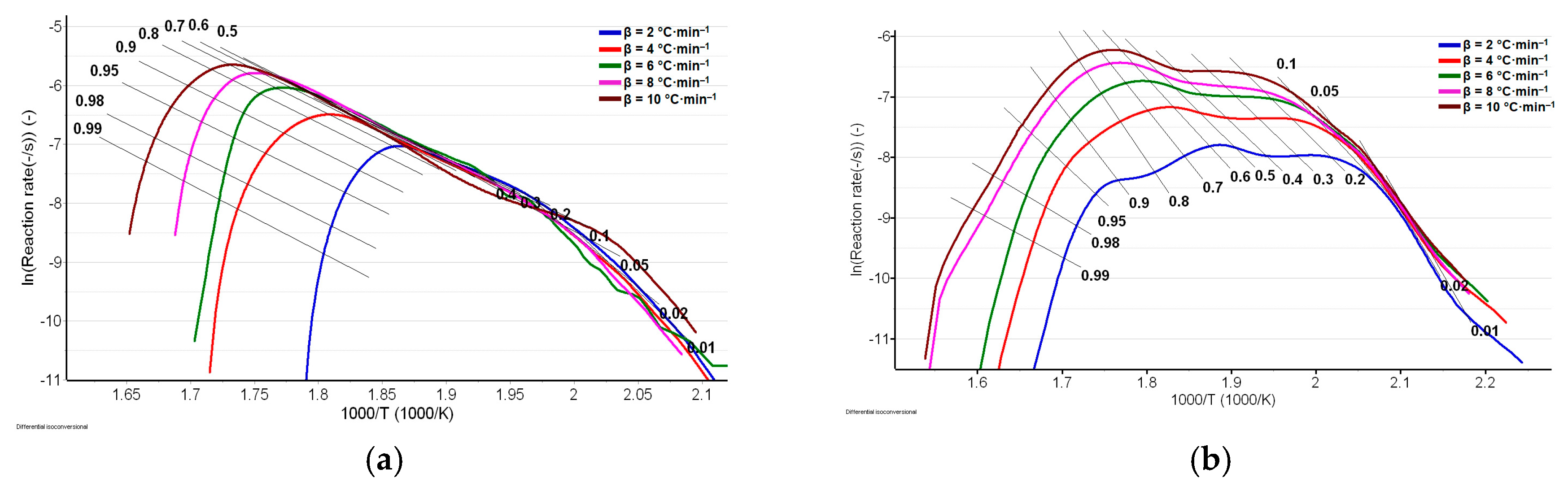

3.3. Kinetic Investigations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodante, F.; Catalani, G.; Vecchio, S. Kinetic analysis of single or multi-step decomposition processes. Limits introduced by statistical analysis. In Proceedings of the Journal of Thermal Analysis and Calorimetry; 2002; Vol. 68, pp. 689–713. [CrossRef]

- Vecchio, S.; Rodante, F.; Tomassetti, M. Thermal stability of disodium and calcium phosphomycin and the effects of the excipients evaluated by thermal analysis. In Proceedings of the Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis; Elsevier, 2001; Vol. 24, pp. 1111–1123. [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.K.; Szilagyi, I.M.; Pielichowska, K.; Raftopoulos, K.N.; Šimon, P.; Melnikov, A.P.; Ivanov, D.A. Good laboratory practice in thermal analysis and calorimetry. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2023, 148, 2211–2231. [CrossRef]

- Wan, Y.; He, H.; Li, F.; Zhang, P.; Gao, X.; Wang, Y.; Gan, Z.; Li, Y. Thermal stability, thermodynamics and kinetic study of (R)-(–)-phenylephrine hydrochloride in nitrogen and air environments. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2023, 148, 2483–2499. [CrossRef]

- Akash, M.S.H.; Rehman, K. Drug Stability and Chemical Kinetics. Drug Stab. Chem. Kinet. 2020, 1–284. [CrossRef]

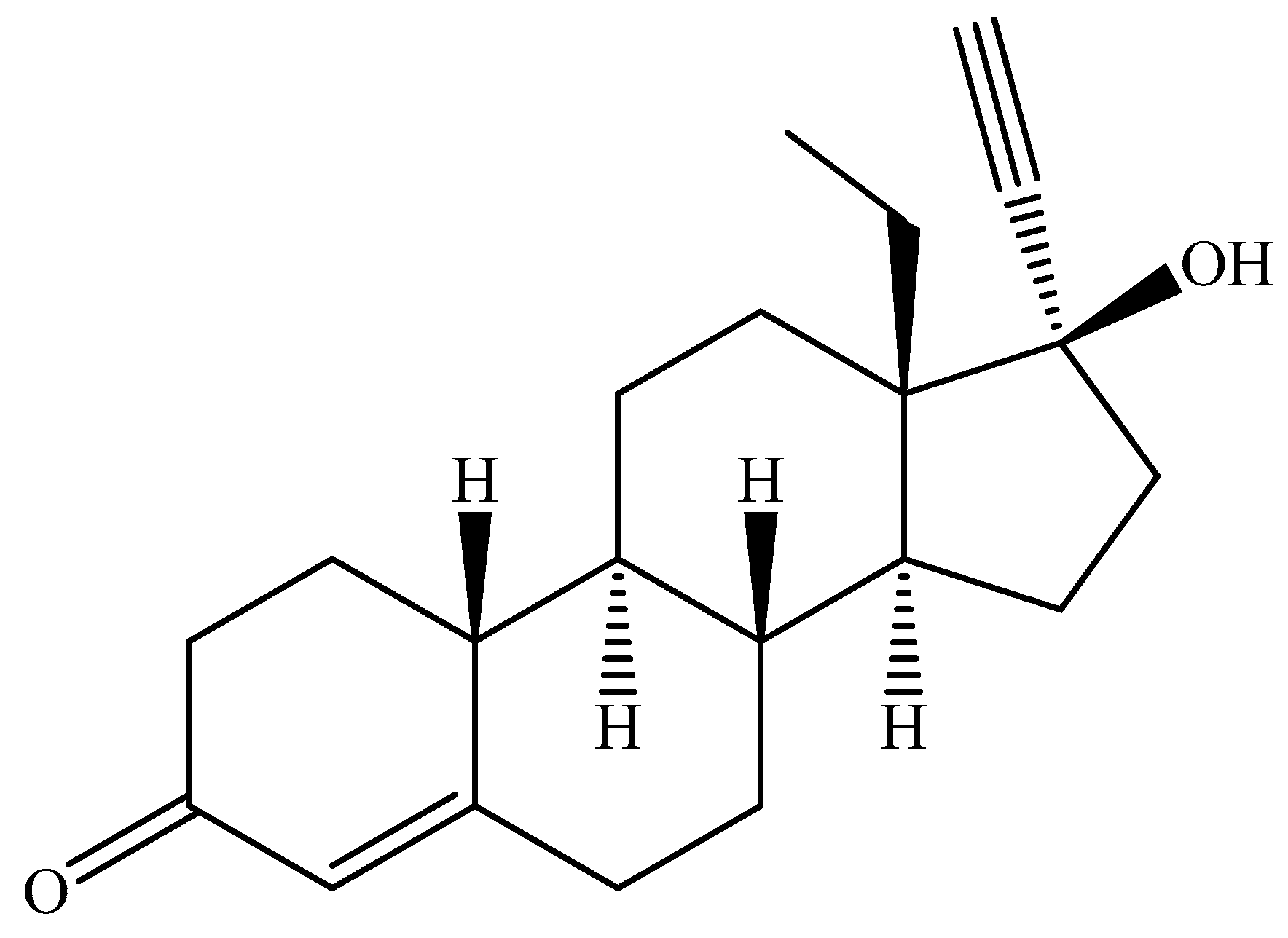

- Vrettakos, C.; Bajaj, T. Levonorgestrel. In; Treasure Island (FL), 2023.

- Lee, S.C.; Norman, W. V. Emergency contraception subsidy in Canada: a comparative policy analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2022, 22, 1110. [CrossRef]

- Dinehart, E.; Lathi, R.B.; Aghajanova, L. Levonorgestrel IUD: is there a long-lasting effect on return to fertility? J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2020, 37, 45–52. [CrossRef]

- Basaraba, C.N.; Westhoff, C.L.; Pike, M.C.; Nandakumar, R.; Cremers, S. Estimating systemic exposure to levonorgestrel from an oral contraceptive. Contraception 2017, 95, 398–404. [CrossRef]

- Fotherby, K. Pharmacokinetics of gestagens: Some problems. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1990, 163, 323–328. [CrossRef]

- Saadatkhah, N.; Carillo Garcia, A.; Ackermann, S.; Leclerc, P.; Latifi, M.; Samih, S.; Patience, G.S.; Chaouki, J. Experimental methods in chemical engineering: Thermogravimetric analysis—TGA. Can. J. Chem. Eng. 2020, 98, 34–43. [CrossRef]

- Topuz, F.; Kilic, M.E.; Durgun, E.; Szekely, G. Fast-dissolving antibacterial nanofibers of cyclodextrin/antibiotic inclusion complexes for oral drug delivery. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 585, 184–194. [CrossRef]

- Pires, F.Q.; Pinho, L.A.; Freire, D.O.; Silva, I.C.R.; Sa-Barreto, L.L.; Cardozo-Filho, L.; Gratieri, T.; Gelfuso, G.M.; Cunha-Filho, M. Thermal analysis used to guide the production of thymol and Lippia origanoides essential oil inclusion complexes with cyclodextrin. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2019, 137, 543–553. [CrossRef]

- Szente, L.; Puskás, I.; Sohajda, T.; Varga, E.; Vass, P.; Nagy, Z.K.; Farkas, A.; Várnai, B.; Béni, S.; Hazai, E. Sulfobutylether-beta-cyclodextrin-enabled antiviral remdesivir: Characterization of electrospun- and lyophilized formulations. Carbohydr. Polym. 2021, 264, 118011. [CrossRef]

- Rout, S.R.; Kenguva, G.; Giri, L.; Kar, A.; Dandela, R. Binary to ternary drug-drug molecular adducts of the antihypertensive drug ketanserin (KTS) with advanced physicochemical properties. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 4640–4643. [CrossRef]

- Gunnam, A.; Nangia, A.K. Solubility improvement of curcumin with amino acids. CrystEngComm 2021, 23, 3398–3410. [CrossRef]

- Nugrahani, I.; Jessica, M.A. Amino acids as the potential co-former for co-crystal development: A review. Molecules 2021, 26. [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S.; Chrissafis, K.; Di Lorenzo, M.L.; Koga, N.; Pijolat, M.; Roduit, B.; Sbirrazzuoli, N.; Suñol, J.J. ICTAC Kinetics Committee recommendations for collecting experimental thermal analysis data for kinetic computations. Thermochim. Acta 2014, 590, 1–23. [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S.; Burnham, A.K.; Criado, J.M.; Pérez-Maqueda, L.A.; Popescu, C.; Sbirrazzuoli, N. ICTAC Kinetics Committee recommendations for performing kinetic computations on thermal analysis data. Thermochim. Acta 2011, 520, 1–19. [CrossRef]

- Koga, N.; Vyazovkin, S.; Burnham, A.K.; Favergeon, L.; Muravyev, N. V.; Pérez-Maqueda, L.A.; Saggese, C.; Sánchez-Jiménez, P.E. ICTAC Kinetics Committee recommendations for analysis of thermal decomposition kinetics. Thermochim. Acta 2023, 719, 179384. [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S.; Achilias, D.; Fernandez-Francos, X.; Galukhin, A.; Sbirrazzuoli, N. ICTAC Kinetics Committee recommendations for analysis of thermal polymerization kinetics. Thermochim. Acta 2022, 714, 179243. [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S.; Burnham, A.K.; Favergeon, L.; Koga, N.; Moukhina, E.; Pérez-Maqueda, L.A.; Sbirrazzuoli, N. ICTAC Kinetics Committee recommendations for analysis of multi-step kinetics. Thermochim. Acta 2020, 689, 178597. [CrossRef]

- Flynn, J.H.; Wall, L.A. A quick, direct method for the determination of activation energy from thermogravimetric data. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Lett. 1966, 4, 323–328. [CrossRef]

- Starink, M.J. The determination of activation energy from linear heating rate experiments: A comparison of the accuracy of isoconversion methods. Thermochim. Acta 2003, 404, 163–176. [CrossRef]

- Friedman, H.L. New methods for evaluating kinetic parameters from thermal analysis data. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Lett. 1969, 7, 41–46. [CrossRef]

- Silverstein, R.M.; Webster, F.X.; Kiemle, D.J. Spectrometric Identification of Organic Compounds. Spectrom. Identif. Org. Compd. 6th ed. 2004.

- Stuart, B.H. Infrared spectroscopy: fundamentals and applications; John Wiley & Sons, 2004; ISBN 0470011130. [CrossRef]

- Norgestrel on Pubchem Available online: https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/compound/Norgestrel (accessed on Aug 22, 2023).

- Baul, B.; Ledeţi, A.; Cîrcioban, D.; Ridichie, A.; Vlase, T.; Vlase, G.; Peter, F.; Ledeţi, I. Thermal Stability and Kinetics of Degradation of Moxonidine as Pure Ingredient vs. Pharmaceutical Formulation. Processes 2023, 11, 1738. [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S.; Wight, C.A. Kinetics in Solids. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 1997, 48, 125–149. [CrossRef]

- Vyazovkin, S. V.; Lesnikovich, A.I. An approach to the solution of the inverse kinetic problem in the case of complex processes. Part 1. Methods employing a series of thermoanalytical curves. Thermochim. Acta 1990, 165, 273–280. [CrossRef]

| Sample | Decomposition step | Ti (°C) |

Tf (°C) |

Tmax DTG (°C) |

Tpeak DSC (°C) |

Δm (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNG | I | 192 | 355 | 306 | 243 | 28.3 |

| II | 355 | 483 | 433; 443 | 41.04 | ||

| LNGTAB | I | 50 | 115 | 68 | 1.8 | |

| II | 115 | 165 | 151 | 3.72 | ||

| III | 165 | 267 | 242 | 19.9 | ||

| IV | 267 | 384 | 306 | 45.4 | ||

| LNGMIX | I | 51 | 110 | 71 | 0.48 | |

| II | 110 | 178 | 151 | 1.88 | ||

| III | 178 | 263 | 233; 248 | 13.34 | ||

| IV | 263 | 380 | 297 | 32.61 | ||

| V | 380 | 466 | 418; 427 | 17.17 | ||

|

Lactose monohydrate |

I | 100 | 171 | 146 | 4.99 | |

| II | 218 | 264 | 236 | 8.7 | ||

| III | 264 | 391 | 306 | 60.6 |

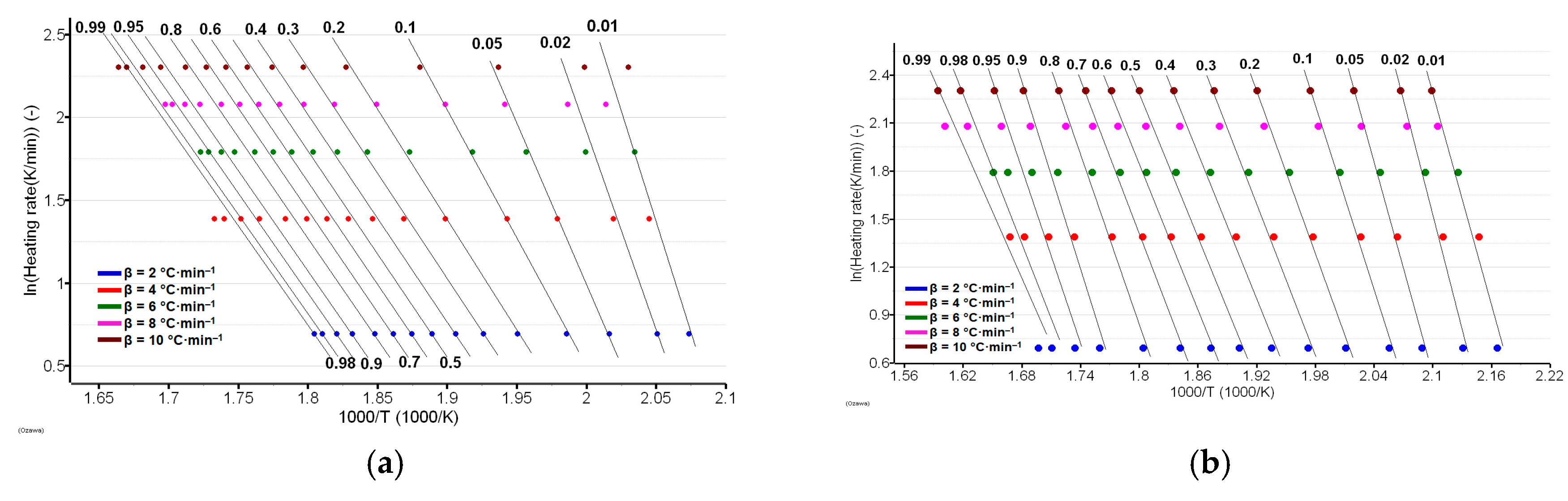

| β (°C·min–1) |

DTG temperature interval for “process 1” (°C) for kinetic analysis of samples | |

|---|---|---|

| LNG | LNGMIX | |

| 2 | 182–288 | 164–345 |

| 4 | 184–313 | 169–356 |

| 6 | 184–322 | 173–368 |

| 8 | 187–327 | 177–378 |

| 10 | 192–355 | 178–380 |

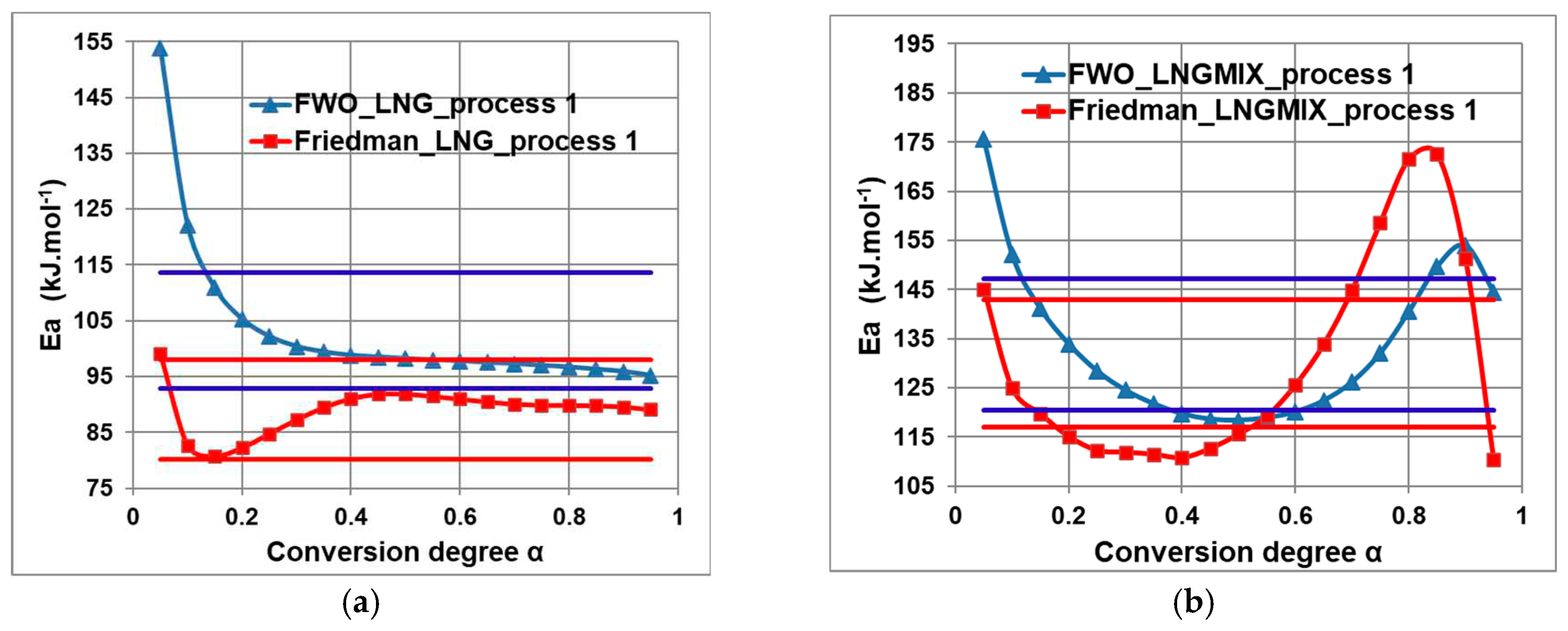

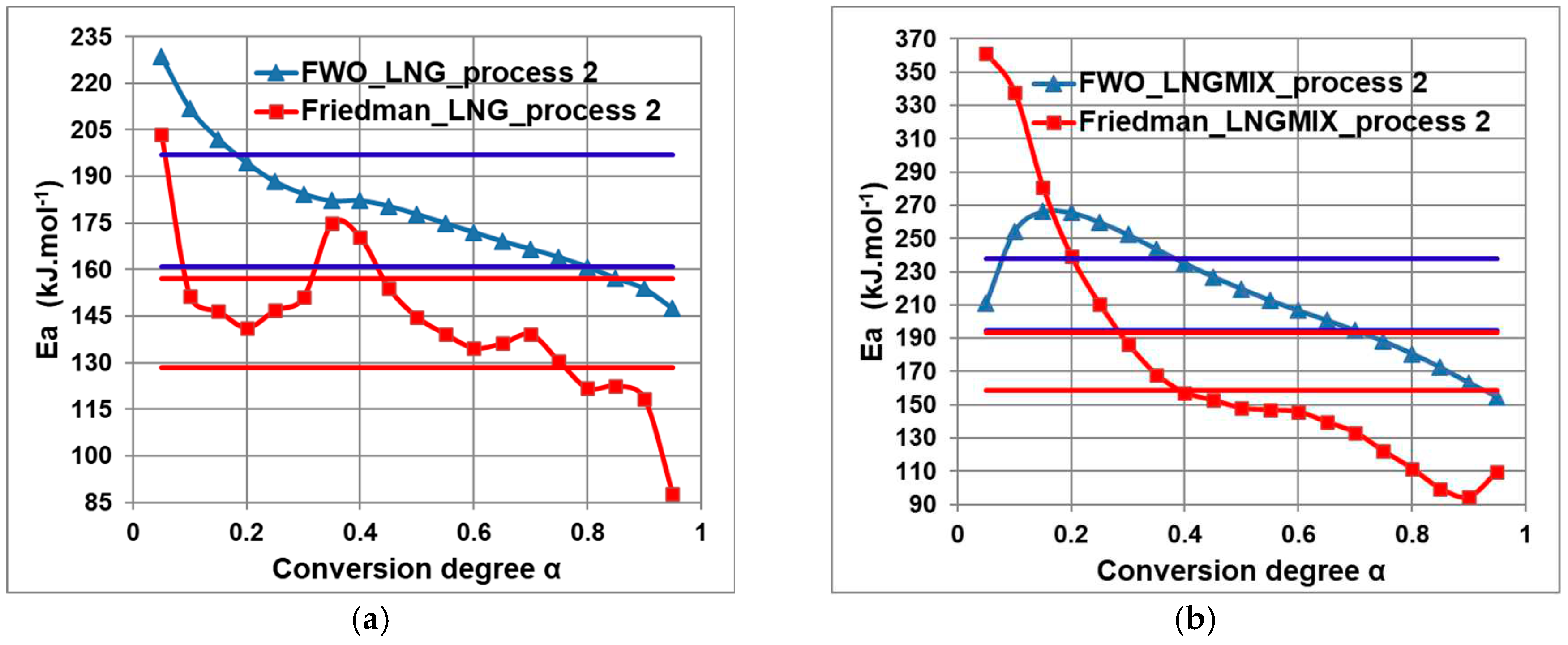

| α | Variation of Ea (kJ·mol–1) vs. α for process 1 for | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LNG | LNGMIX | |||

| FR | FWO | FR | FWO | |

| 0.05 | 99.1 | 153.8 | 145.1 | 175.6 |

| 0.1 | 82.7 | 122.1 | 124.9 | 152.1 |

| 0.15 | 80.8 | 110.9 | 119.7 | 141.1 |

| 0.2 | 82.3 | 105.3 | 115.1 | 133.9 |

| 0.25 | 84.8 | 102.2 | 112.3 | 128.4 |

| 0.3 | 87.3 | 100.4 | 111.9 | 124.5 |

| 0.35 | 89.5 | 99.4 | 111.5 | 121.7 |

| 0.4 | 91.1 | 98.8 | 110.8 | 119.7 |

| 0.45 | 91.9 | 98.5 | 112.7 | 118.6 |

| 0.5 | 91.9 | 98.2 | 115.6 | 118.4 |

| 0.55 | 91.5 | 98.0 | 119.3 | 118.9 |

| 0.6 | 91.0 | 97.8 | 125.6 | 120.1 |

| 0.65 | 90.5 | 97.5 | 133.9 | 122.4 |

| 0.7 | 90.1 | 97.3 | 144.9 | 126.2 |

| 0.75 | 89.9 | 97.0 | 158.7 | 132.1 |

| 0.8 | 89.9 | 96.7 | 171.5 | 140.5 |

| 0.85 | 89.8 | 96.3 | 172.6 | 149.7 |

| 0.9 | 89.6 | 95.9 | 151.4 | 154.0 |

| 0.95 | 89.1 | 95.2 | 110.3 | 144.5 |

| Ēa / kJ·mol–1 | 89.1±1.0 | 103.2±3.2 | 129.9±4.8 | 133.8±3.6 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).