Submitted:

28 August 2023

Posted:

30 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

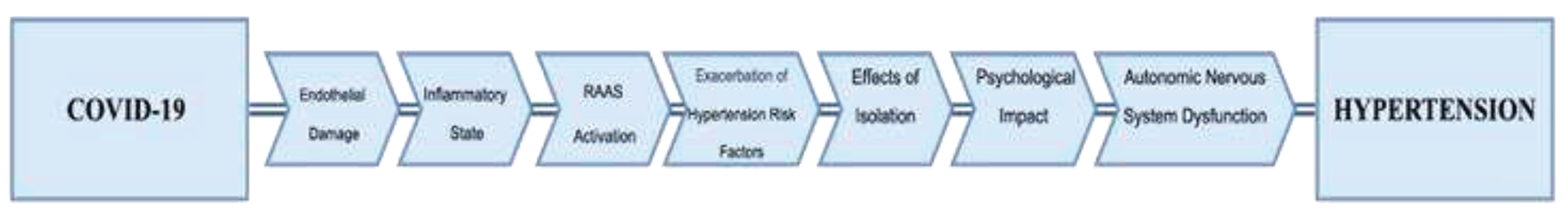

1.1. COVID-19 Cardiovascular Outcome

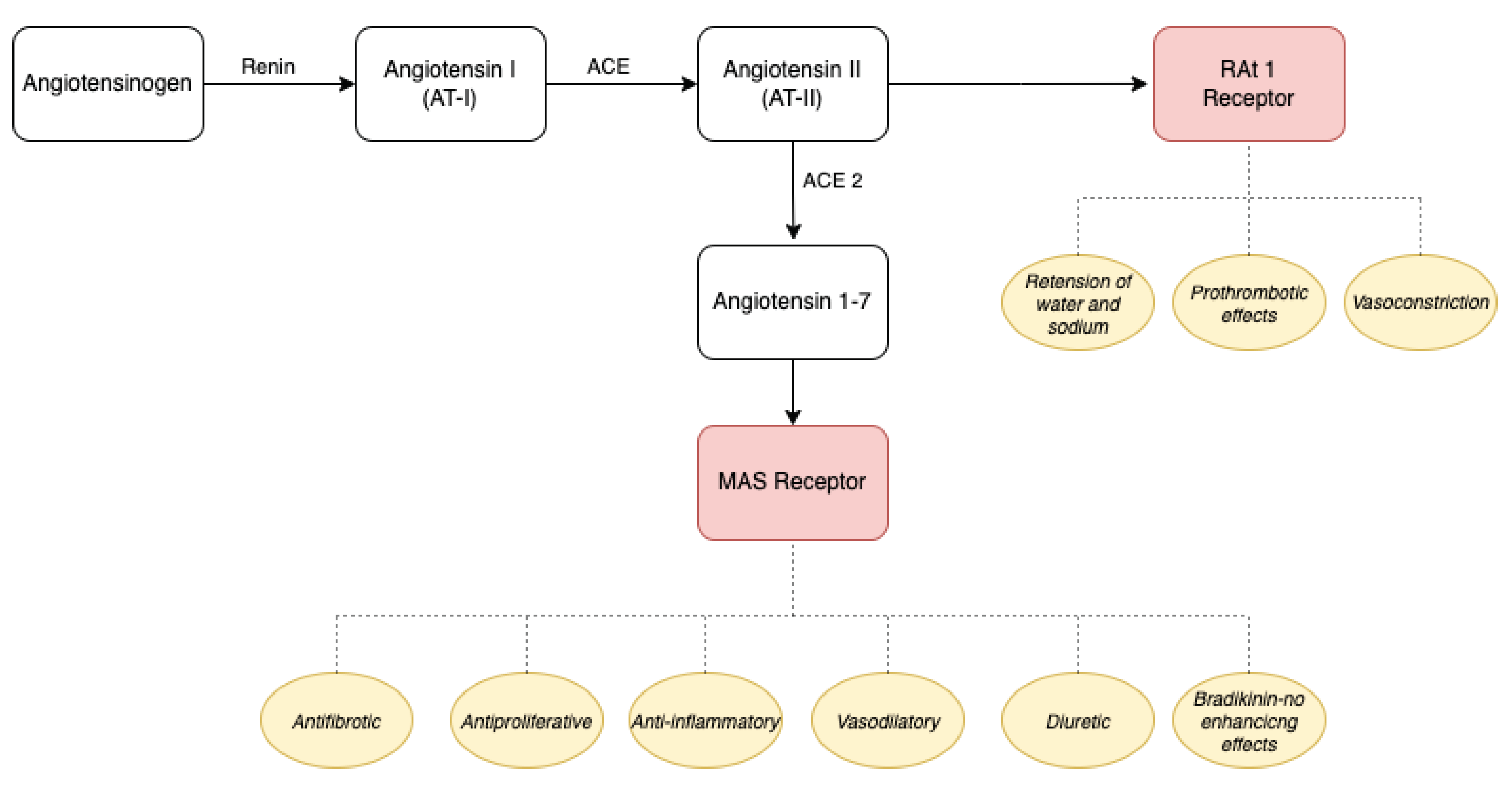

1.2. Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System

1.3. ACE-2 and COVID-19

1.4. Other Factors Contributing to the Hypertension Development

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

4.1. Research Supporting BP Increase as a Complication of Long COVID

4.2. Studies Suggesting a Transient Increase in BP Following an Acute COVID-19 Infection

4.3. Studies in Which No Changes in BP Values Were Observed after COVID-19

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davis, H.E.; McCorkell, L.; Vogel, J.M. Long COVID: Major findings, mechanisms and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2023, 21, 133–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Living with Covid19. 2020. Available online: https://evidence.nihr.ac.uk/themedreview/living-with-covid19/ (accessed on April 2023).

- Venkatesan, P. NICE guideline on long COVID. Lancet Respir. Med. 2021, 9, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Post COVID-19 Condition (Long COVID). Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition (accessed on April 2023).

- Munblit, D.; O'Hara, M.E.; Akrami, A.; Perego, E.; Olliaro, P.; Needham, D.M. Long COVID: Aiming for a consensus. Lancet Respir. Med. 2022, 10, 632–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parhizgar, P.; Yazdankhah, N.; Rzepka, A.M.; Chung, K.Y.C.; Ali, I.; Lai Fat Fur, R.; Russell, V.; Cheung, A.M. Beyond Acute COVID-19: A Review of Long-term Cardiovascular Outcomes. Can. J. Cardiol. 2023, 39, 726–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otifi, H.M.; Adiga, B.K. Endothelial Dysfunction in Covid-19 Infection. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 363, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alcocer-Díaz-Barreiro, L.; Cossio-Aranda, J.; Verdejo-Paris, J.; Odin-de-Los-Ríos, M.; Galván-Oseguera, H.; Álvarez-López, H.; Alcocer-Gamba, M.A. COVID-19 and the renin, angiotensin, aldosterone system. A complex relationship. Arch. Cardiol. Mex. 2020, 90, 19–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ferrario, C.M.; Chappell, M.C.; Tallant, E.A.; Brosnihan, K.B.; Diz, D.I. Counterregulatory actions of angiotensin-(1-7). Hypertension 1997, 30, 535–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roks, A.J.; van Geel, P.P.; Pinto, Y.M.; Buikema, H.; Henning, R.H.; de Zeeuw, D.; van Gilst, W.H. Angiotensin-(1-7) is a modulator of the human renin-angiotensin system. Hypertension 1999, 34, 296–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, K.; Ohishi, M.; Katsuya, T.; Ito, N.; Ikushima, M.; Kaibe, M.; Tatara, Y.; Shiota, A.; Sugano, S.; Takeda, S.; Rakugi, H.; Ogihara, T. Deletion of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 accelerates pressure overload-induced cardiac dysfunction by increasing local angiotensin II. Hypertension 2006, 47, 718–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vickers C, Hales P, Kaushik V, Dick L, Gavin J, Tang J, Godbout K, Parsons T, Baronas E, Hsieh F, Acton S, Patane M, Nichols A, Tummino P. Hydrolysis of biological peptides by human angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase. J Biol Chem. 2000, 277, 14838–14843. [Google Scholar]

- Gurley, S.B.; Allred, A.; Le, T.H.; Griffiths, R.; Mao, L.; Philip, N.; Haystead, T.A.; Donoghue, M.; Breitbart, R.E.; Acton, S.L.; Rockman, H.A.; Coffman, T.M. Altered blood pressure responses and normal cardiac phenotype in ACE2-null mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2006, 116, 2218–2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, R.A.S.; Sampaio, W.O.; Alzamora, A.C.; Motta-Santos, D.; Alenina, N.; Bader, M.; Campagnole-Santos, M.J. The ACE2/Angiotensin-(1-7)/MAS Axis of the Renin-Angiotensin System: Focus on Angiotensin-(1-7). Physiol Rev. 2018, 98, 505–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shenoy, V.; Gjymishka, A.; Jarajapu, Y.P.; Qi, Y.; Afzal, A.; Rigatto, K.; Ferreira, A.J.; Fraga-Silva, R.A.; Kearns, P.; Douglas, J.Y.; et al. Diminazene attenuates pulmonary hypertension and improves angiogenic progenitor cell functions in experimental models. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 187, 648–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, A.J.; Shenoy, V.; Yamazato, Y.; Sriramula, S.; Francis, J.; Yuan, L.; Castellano, R.K.; Ostrov, D.A.; Oh, S.P.; Katovich, M.J.; Raizada, M.K. Evidence for angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 as a therapeutic target for the prevention of pulmonary hypertension. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2009, 179, 1048–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Xia, H.; Santos, R.A.; et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: A new target for neurogenic hypertension. Exp. Physiol. 2010, 95, 601–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grimes, J.M.; Grimes, K.V. p38 MAPK inhibition: A promising therapeutic approach for COVID-19. J. Mol. Cell Cardiol. 2020, 144, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomasoni, D.; Italia, L.; Adamo, M.; et al. COVID-19 and heart failure: From infection to inflammation and angiotensin II stimulation. Searching for evidence from a new disease. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 2020, 22, 957–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oudit, G.Y.; Pfeffer, M.A. Plasma angiotensin-converting enzyme 2: Novel biomarker in heart failure with implications for COVID-19. Eur. Heart J. 2020, 41, 1818–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Moore, M.; Vasilieva, N.; Sui, J.; Wong, S.; Berne, M.; et al. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature 2003, 426, 450–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrapp, D.; Wang, N.; Corbett, K.; Goldsmith, J.; Hsieh, C.; Abiona, O.; et al. Cryo-EM structure of the 2019-nCoV spike in the prefusion conformation. Science 2020, 367, 1260–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, W.; Gui, M.; Wang, X.; Xiang, Y. Cryo-EM structure of the SARS coronavirus spike glycoprotein in complex with its host cell receptor ACE2. PLoS Pathog. 2018, 14, 1007236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Li, W.; Farzan, M.; Harrison, S. Structure of SARS coronavirus spike receptor-binding domain complexed with receptor. Science 2005, 309, 1864–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, W.; Yang, X.; Yang, D. Role of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) in COVID-19. Crit Care 2020, 24, 422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, H.; Look, D.; Tan, P.; Shi, L.; Hickey, M.; Gakhar, L.; et al. Ectodomain shedding of angiotensin converting enzyme 2 in human airway epithelia. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2009, 297, 84–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heurich, A.; Hofmann-Winkler, H.; Gierer, S.; Liepold, T.; Jahn, O.; Pöhlmann, S. TMPRSS2 and ADAM17 cleave ACE2 differentially and only proteolysis by TMPRSS2 augments entry driven by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike protein. J. Virol. 2014, 88, 1293–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F. Structure, function, and evolution of coronavirus spike proteins. Annu. Rev. Virol. 2016, 3, 237–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Y.; Chien, S.; Chen, I.; Lai, C.; Tsay, Y.; Chang, S.; Chang, M. Surface vimentin is critical for the cell entry of SARS-CoV. J. Biomed. Sci. 2016, 23, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, Y.; Tanaka, N.; Tanaka, Y.; Inoue, S.; Morita, K.; Zhuang, M.; et al. Clathrin-dependent entry of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus into target cells expressing ACE2 with the cytoplasmic tail deleted. J. Virol. 2007, 81, 8722–8729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, K.V.; et al. Coronavirus receptor specificity. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1993, 342, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Glowacka, I.; Bertram, S.; Herzog, P.; Pfefferle, S.; Steffen, I.; Muench, M.O.; Simmons, G.; Hofmann, H.; Kuri, T.; Weber, F.; Eichler, J.; Drosten, C.; Pöhlmann, S. Differential downregulation of ACE2 by the spike proteins of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus and human coronavirus NL63. J Virol. 2010, 84, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nappi, F.; Avtaar Singh, S.S. Endothelial Dysfunction in SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gathiram, P.; Mackraj, I.; Moodley, J. The Renin-Angiotensin System, Hypertension, and SARS-CoV-2 Infection: A Review. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2021, 23, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lip, S.; Mccallum, L.; Delles, C.; McClure, J.D.; Guzik, T.; Berry, C.; Touyz, R.; Padmanabhan, S. Rationale and Design for the LOnger-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 INfection on blood Vessels And blood pRessure (LOCHINVAR): An observational phenotyping study. Open Heart. 2022, 002057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forman, J.P.; Stampfer, M.J.; Curhan, G.C. Diet and lifestyle risk factors associated with incident hypertension in women. JAMA 2009, 302, 401–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonne-Holm, S.; Sørensen, T.I.; Jensen, G.; Schnohr, P. Independent effects of weight change and attained body weight on prevalence of arterial hypertension in obese and non-obese men. BMJ 1989, 299, 767–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raman, B.; Cassar, M.P.; Tunnicliffe, E.M.; Filippini, N.; Griffanti, L.; Alfaro-Almagro, F.; Okell, T.; Sheerin, F.; Xie, C.; Mahmod, M.; et al. Medium-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on multiple vital organs, exercise capacity, cognition, quality of life and mental health, post-hospital discharge. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 31, 100683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shouman, K.; Vanichkachorn, G.; Cheshire, W.P. Autonomic dysfunction following COVID-19 infection: An early experience. Clin Auton Res 2021, 31, 385–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lo, Y.L.; Leong, H.N.; Hsu, L.Y.; Tan, T.T.; Kurup, A.; Fook-Chong, S.; Tan, B.H. Autonomic dysfunction in recovered severe acute respiratory syndrome patients. Can. J. Neurol. Sci. 2005, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Y.; Yuan, D.; Chen, D.G.; Ng, R.H.; Wang, K.; Choi, J.; Li, S.; Hong, S.; Zhang, R.; Xie, J.; et al. Multiple early factors anticipate post-acute COVID-19 sequelae. Cell 2022, 185, 881–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, S.J.; Feigen, C.M.; Vazquez, J.P.; Kobets, A.J.; Altschul, D.J. Neurological Sequelae of COVID-19. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2022, 21, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Yao, S.; Sun, G.; Yu, S.; Sun, Z.; Zheng, L.; Xu, C.; Li, J.; Sun, Y. Total and abdominal obesity among rural Chinese women and the association with hypertension. Nutrition 2012, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanaka, M.; Itoh, H. Hypertension as a Metabolic Disorder and the Novel Role of the Gut. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 2019, 21, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, R.C. Autonomic dysfunction in SARS-COV-2 infection acute and long-term implications COVID-19 editor's page series. J. Thromb. Thombolysis. 2021, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodman, B.P.; Khoury, J.A.; Blair, J.E.; Grill, M.F. COVID-19 Dysautonomia. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 624968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dani, M.; Dirksen, A.; Taraborreli, P.; Torocastro, M.; Panagopoulos, D.; Sutton, R.; et al. Autonomic dysfunction in ‘long COVID’: Rationale, physiology and management strategies. Clin. Med. 2021, 21, 63–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.; Jolkkoken, J.; Zhao, C. Neurotropism of SARS-CoV-2 and its neuropathological alterations: Similarities with other coronaviruses. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 11, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, K.C.; Silva, C.C.; Trindade, S.d.S.; Santos, M.C.d.S.; Rocha, R.S.B.; Vasconcelos, P.F.d.C.; Quaresma, J.A.S.; Falcão, L.F.M. Reduction of Cardiac Autonomic Modulation and Increased Sympathetic Activity by Heart Rate Variability in Patients With Long COVID. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2022, 9, 862001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balcom, E.F.; Nath, A.; Power, C. Acute and chronic neurological disorders in COVID-19: Potential mechanisms of disease. Brain 2021, 144, 3576–3588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hultström, M.; von Seth, M.; Frithiof, R. Hyperreninemia and low total body water may contribute to acute kidney injury in COVID-19 patients in intensive care. J. Hypertens. 2020, 1613–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saeed, S.; Tadic, M.; Larsen, T.H.; Grassi, G.; Mancia, G. Coronavirus disease 2019 and cardiovascular complications: Focused clinical review. J. Hypertens. 2021, 1282–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Konukoglu, D.; Uzun, H. Endothelial dysfunction and hypertension. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2017, 956, 511–540. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rogier van der Velde, A.; Meijers, W.C.; de Boer, R.A. “Chapter 3.7.1 - Cardiovascular biomarkers: Translational aspects of hypertension, atherosclerosis, and heart failure in drug development,” in Principles of Translational Science in Medicine, 2nd Edn. ed. M. Wehling (Boston, MA: Academic Press), 2015, pp 167–183.

- Muhamad, S.-A.; Ugusman, A.; Kumar, J.; Skiba, D.; Hamid, A.A.; Aminuddin, A. COVID-19 and Hypertension: The What, the Why, and the How. Front. Physiol. 2021, 12, 665064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrosino, P.; Parrella, P.; Formisano, R.; Perrotta, G.; D'Anna, S.E.; Mosella, M.; Papa, A.; Maniscalco, M. Cardiopulmonary Exercise Performance and Endothelial Function in Convalescent COVID-19 Patients. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charfeddine, S.; Ibn Hadj Amor, H.; Jdidi, J.; Torjmen, S.; Kraiem, S.; Hammami, R.; Bahloul, A.; Kallel, N.; Moussa, N.; Touil, I.; et al. Long COVID 19 Syndrome: Is It Related to Microcirculation and Endothelial Dysfunction? Insights From TUN-EndCOV Study. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 2021, 8, 745758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Q.; Xu, M.; Li, J.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, Y.; Dong, W. Clinical sequelae of COVID-19 survivors in Wuhan, China: A single-centre longitudinal study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2021, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, Q.; Wang, F.; Yang, Y.; Hu, G.; Guo, S.; Zhang, Q.; Bryant, A.; Zhang, L.; Kurts, C.; Wei, L.; Yuan, X.; Li, J. Health Issues and Immunological Assessment Related to Wuhan's COVID-19 Survivors: A Multicenter Follow-Up Study. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021, 8, 617689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, Y.F.; Liu, T.; Yu, J.N.; Xu, X.R.; Zahid, K.R.; Wei, Y.C.; Wang, X.H.; Zhou, F.L. Half-year follow-up of patients recovering from severe COVID-19: Analysis of symptoms and their risk factors. J. Intern. Med. 2021, 290, 444–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boglione, L.; Meli, G.; Poletti, F.; Rostagno, R.; Moglia, R.; Cantone, M.; Esposito, M.; Scianguetta, C.; Domenicale, B.; Di Pasquale, F.; et al. Risk factors and incidence of long-COVID syndrome in hospitalized patients: Does remdesivir have a protective effect? QJM Int. J. Med. 2021, 14, 865–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- 63. Özcan S, İnce O, Güner A, Katkat F, Dönmez E, Tuğrul S, Şahin İ, Okuyan E, Kayıkçıoğlu M. Long-Term Clinical Consequences of Patients Hospitalized for COVID-19 Infection. Anatol. J. Cardiol. 2022, 305–315.

- Gameil, M.A.; Marzouk, R.E.; Elsebaie, A.H.; et al. Long-term clinical and biochemical residue after COVID-19 recovery. Egypt. Liver Journal 2021, 11, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Sluijs, K.M.; Bakker, E.A.; Schuijt, T.J.; Joseph, J.; Kavousi, M.; Geersing, G.J.; Rutten, F.H.; Hartman, Y.A.W.; Thijssen, D.H.J.; Eijsvogels, T.M.H. Long-term cardiovascular health status and physical functioning of nonhospitalized patients with COVID-19 compared with non-COVID-19 controls. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 2023, 324, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tanni, S.E.; Tonon, C.R.; Gatto, M.; Mota, G.A.F.; Okoshi, M.P. Post-COVID-19 syndrome: Cardiovascular manifestations. Int. J. Cardiol. 2022, 369, 80–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfadda, A.A.; Rafiullah, M.; Alkhowaiter, M.; Alotaibi, N.; Alzahrani, M.; Binkhamis, K.; Siddiqui, K.; Youssef, A.; Altalhi, H.; Almaghlouth, I.; et al. Clinical and biochemical characteristics of people experiencing post-coronavirus disease 2019-related symptoms: A prospective follow-up investigation. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 1067082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daugherty, S.E.; Guo, Y.; Heath, K.; Dasmariñas, M.C.; Jubilo, K.G.; Samranvedhya, J.; Lipsitch, M.; Cohen, K. Risk of clinical sequelae after the acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2021, 373, 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahmoud, Z.; East, L.; Gleva, M.; Woodard, P.K.; Lavine, K.; Verma, A.K. Cardiovascular symptom phenotypes of post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2. Int. J. Cardiol. 2022, 22, S0167–5273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stute, N.L.; Szeghy, R.E.; Stickford, J.L.; Province, V.P.; Augenreich, M.A.; Ratchford, S.M.; Stickford, A.S.L. Longitudinal observations of sympathetic neural activity and hemodynamics during 6 months recovery from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Physiol. Rep. 2022, 10, e15423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szeghy, R.E.; Province, V.M.; Stute, N.L.; Augenreich, M.A.; Koontz, L.K.; Stickford, J.L.; Stickford, A.S.L.; Ratchford, S.M. Carotid stiffness, intima-media thickness and aortic augmentation index among adults with SARS-CoV-2. Exp Physiol. 2022, 107, 694–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratchford, S.M.; Stickford, J.L.; Province, V.M.; Stute, N.; Augenreich, M.A.; Koontz, L.K.; Bobo, L.K.; Stickford, A.S.L. Vascular alterations among young adults with SARS-CoV-2. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021, 320, 404–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akpek, M. Does COVID-19 Cause Hypertension? Angiology 2022, 73, 682–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandadeva, D.; Skow, R.J.; Grotle, A.K.; Stephens, B.Y.; Young, B.E.; Fadel, P.J. Impact of COVID-19 on ambulatory blood pressure in young adults: A cross-sectional analysis investigating time since diagnosis. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2022, 133, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetyana, M.; Ternushchak Marianna, I.; Tovt-Korshynska Antonina, V. Varvarynets AMBULATORY BLOOD PRESSURE VARIABILITY IN YOUNG ADULTS WITH LONG-COVID SYNDROME, Wiadomości Lekarskie, VOLUME LXXV, ISSUE 10, OCTOBER 2022, 75, 2481–2485.

- Delalić, Đ.; Jug, J.; Prkačin, I. ARTERIAL HYPERTENSION FOLLOWING COVID-19: A RETROSPECTIVE STUDY OF PATIENTS IN A CENTRAL EUROPEAN TERTIARY CARE CENTER. Acta Clin. Croat. 2022, 61, 23–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Lorenzo, R.; Conte, C.; Lanzani, C.; Benedetti, F.; Roveri, L.; Mazza, M.G.; Brioni, E.; Giacalone, G.; Canti, V.; Sofia, V.; et al. Residual clinical damage after COVID-19: A retrospective and prospective observational cohort study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tisler, A.; Stirrup, O.; Pisarev, H.; Kalda, R.; Meister, T.; Suija, K.; Kolde, R.; Piirsoo, M.; Uusküla, A. Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 among hospitalized patients in Estonia: Nationwide matched cohort study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinmetz, A.; Gross, S.; Lehnert, K.; Lücker, P.; Friedrich, N.; Nauck, M.; Bahlmann, S.; Fielitz, J.; Dörr, M. Longitudinal Clinical Features of Post-COVID-19 Patients—Symptoms, Fatigue and Physical Function at 3- and 6-Month Follow-Up. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ogungbe, O.; Gilotra, N.A.; Davidson, P.M.; et al. ardiac postacute sequelae symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 in community-dwelling adults: Cross-sectional study. Open Heart 2022, 9, e002084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.G.; Dagliati, A.; Shakeri Hossein Abad, Z.; Xiong, X.; Bonzel, C.L.; Xia, Z.; Tan, B.W.Q.; Avillach, P.; Brat, G.A.; Hong, C.; et al. Consortium for Clinical Characterization of COVID-19 by EHR (4CE); Cai T, South AM, Kohane IS, Weber GM. International electronic health record-derived post-acute sequelae profiles of COVID-19 patients. NPJ Digit. Med. 2022, 5, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, K.; Ren, S.; Heath, K.; Dasmariñas, M.C.; Jubilo, K.G.; Guo, Y.; Lipsitch, M.; Daugherty, S.E. Risk of persistent and new clinical sequelae among adults aged 65 years and older during the post-acute phase of SARS-CoV-2 infection: Retrospective cohort study. BMJ 2022, 376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Aly, Z.; Bowe, B.; Xie, Y. Long COVID after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat. Med. 2022, 28, 1461–1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizrahi, B.; Sudry, T.; Flaks-Manov, N.; Yehezkelli, Y.; Kalkstein, N.; Akiva, P.; Ekka-Zohar, A.; Ben David, S.S.; Lerner, U.; Bivas-Benita, M.; Greenfeld, S. Long covid outcomes at one year after mild SARS-CoV-2 infection: Nationwide cohort study. BMJ. 2023, 380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernández-Ortega, M.Á.; Ponce-Rosas, E.R.; Muñiz-Salinas, D.A.; Rodríguez-Mendoza, O.; Nájera Chávez, P.; Sánchez-Pozos, V.; Dávila-Mendoza, R.; Barrell, A.E. Cognitive dysfunction, diabetes mellitus 2 and arterial hypertension: Sequelae up to one year of COVID-19. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2023, 52, 102553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennifer, K.; Shirley, S.B.D.; Avi, P.; Daniella, R.C.; Naama, S.S.; Anat, E.Z.; Miri, M.R. Post-acute sequelae of COVID-19 infection. Prev. Med. Rep. 2023, 31, 102097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vyas, P.; Joshi, D.; Sharma, V.; Parmar, M.; Vadodariya, J.; Patel, K.; Modi, G. Incidence and predictors of development of new onset hypertension post COVID-19 disease. Indian. Heart J. 2023, 0019-4832, 00103–00107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abumayyaleh, M.; Núñez Gil, I.J.; Viana-LLamas, M.C.; Raposeiras Roubin, S.; Romero, R.; Alfonso-Rodríguez, E.; Uribarri, A.; Feltes, G.; Becerra-Muñoz, V.M.; Santoro, F.; et al. HOPE COVID-19 investigators. Post-COVID-19 syndrome and diabetes mellitus: A propensity-matched analysis of the International HOPE-II COVID-19 Registry. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Hermosillo, G.J.A.; Galarza, E.J.; Fermín, O.V.; González, J.M.N.; Tostado, L.M.F.Á.; Lozano, M.A.E.; Rabasa, C.R.; Martínez Alvarado, M.D.R. Exaggerated blood pressure elevation in response to orthostatic challenge, a post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection (PASC) after hospitalization. Auton. Neurosci. 2023, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saloň, A.; Neshev, R.; Teraž, K.; Šimunič, B.; Peskar, M.; Marušič, U.; Pišot, S.; Šlosar, L.; Gasparini, M.; Pišot, R.; et al. A pilot study: Exploring the influence of COVID-19 on cardiovascular physiology and retinal microcirculation. Microvasc. Res. 2023, 150, 104588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nandadeva, D.; Skow, R.J.; Stephens, B.Y.; Grotle, A.-K.; Georgoudiou, S.; Barshikar, S.; Seo, Y.; Paul, J. Fadel American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2023, 6, 713–720. 6.

- Al-Aly, Z.; Xie, Y.; Bowe, B. High-dimensional characterization of post-acute sequelae of COVID-19. Nature 2021, 594, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shah, N.P.; Clare, R.M.; Chiswell, K.; Navar, A.M.; Shah, B.R.; Peterson, E.D. Trends of blood pressure control in the U.S. during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. Heart J. 2022, 247, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojciechowska, W.; Rajzer, M.; Weber, T.; Prejbisz, A.; Dobrowolski, P.; Ostrowska, A.; et al. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in treated patients with hypertension in the COVID-19 pandemic - the study of European society of hypertension (ESH ABPM COVID-19 study). Blood Press. 2023, 322161998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celermajer, D.S.; Sorensen, K.E.; Gooch, V.M.; Spiegelhalter, D.J.; Miller, O.I.; Sullivan, I.D.; Lloyd, J.K.; Deanfield, J.E. Non-invasive detection of endothelial dysfunction in children and adults at risk of atherosclerosis. Lancet 1992, 340, 1111–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joannides, R.; Haefeli, W.E.; Linder, L.; Richard, V.; Bakkali, E.H.; Thuillez, C.; Luscher, T.F. Nitric oxide is responsible for flow-dependent dilatation of human peripheral conduit arteries in vivo. Circulation 1995, 91, 1314–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, R.A.; Nishiyama, S.K.; Wray, D.W.; Richardson, R.S. Ultrasound assessment of flow-mediated dilation. Hypertension 2010, 55, 1075–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC). Worldwide trends in hypertension prevalence and progress in treatment and control from 1990 to 2019: A pooled analysis of 1201 population-representative studies with 104 million participants. Lancet. 2021, 398, 957–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaughan, A.S.; Coronado, F.; Casper, M.; Loustalot, F.; Wright, J.S. County-Level Trends in Hypertension-Related Cardiovascular Disease Mortality-United States, 2000 to 2019. J Am Heart Assoc. 2022, 11, e024785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polsce, W.P.T.N. Rules for the management of hypertension. Arterial Hypertension 2008, 12, 317–342. [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien, M.W.; Petterson, J.L.; Kimmerly, D.S. An open-source program to analyze spontaneous sympathetic neurohemodynamic transduction. J. Neurophysiol. 2021, 125, 972–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Leon, S.; Wegman-Ostrosky, T.; Perelman, C.; Sepulveda, R.; Rebolledo, P.A.; Cuapio, A.; Villapol, S. More than 50 long-term effects of COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2021, 11, 16144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study, (year) | City/country | Sample size | Disease severity | Mean/Median follow-up periods | Mean/median age (years)/male (%) | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xiong et al. (2020) [59] | Wuhan, China | 538 | General, severe and critical | Median (IQR): 97.0 (95.0–102.0) days |

Median (IQR): 52.0 (41.0–62.0 Male 46% | Newly diagnosed hypertension- 7 persons (1,3%) |

| Mei et al. (2021) [60] |

Wuhan, China | 3677 | Mild, severe and critical |

Median (IQR): 144 (135–157) days |

Median (IQR): 59.0 (47–68) Male 46% |

6 individuals developed hypertension |

| Shang et al., (2021) [61] | Wuhan, China | 796 | Severe, critical | 6 months |

Median (IQR): 62.0 (51.0–69.0) Male 51% |

3(0,4%) cases of newly diagnosed hypertension |

| Boglione et al., (2021) [62] | Italy | 449 | Hospitalized |

Median (IQR): 178.5 (165.5 – 211.5) days |

Median (IQR): 65.0 (56.0–75.5) Male 78% |

116 individuals reported hypertension on their first visit (25.8%), and it persisted in 61 (14%) individuals after 180 days from hospital discharge. |

| Sevgi Özcan et al. (2022) [63] | Turkey | 406 | Hospitalized | 3 and 6 months |

Age (years) WHO 3: 46.8 ± 13.3 WHO 4: 52.8 ± 13.1 WHO 5,6: 54.8 ± 11.8 Male n (%) WHO 3: 35 (42) WHO 4: 163 (56) WHO 5,6: 19 (60) |

Hypertension on 4 patients. Level risk risk: 1.229 0,784-2,019 |

| Mohammed Ali Gameil et al. (2021) [64] |

Egypt | 240 | From mild to moderate |

3-4 months: 58(48,3) 4-5 months: 37(30,8) 5-6 months: 15(12,5) > 6 months: 10(8.3) |

Mean age at 38.29 male 55.6% | Systolic blood pressure was significantly elevated (P=0.001) Control cases 120,63±8,49 vs research group 126,70±10,31 |

| Koen M vas der. Sluijs et al. (2022) [65] | Netherlands | 202 | mild | After 175 days [126-235] | Mean age at 59 and male 58% | There was no difference in blood pressure or pulse stiffness |

| Suzana E. Tanni et al. (2022) [66] |

Brazil | 100 | No data | After 99 days | Mean age at 46,3. Mostly female |

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure, heart rate and body weight were slightly but significantly increased compared to baseline. |

| Assim A. Alfadda et al. (2022) [67] | Saudi Arabia | 98 | Hospitalized | After 7,02 ± 1,6 months. | Mean age at 48.87 (±17.11) Male 51% (50) |

Higher mean blood pressure was found in the follow up 131.26 ± 15.3 |

| Sarah E. Daugherty et al. (2021) [68] | USA | 266586 | 8.2% hospitalized 1.1% admitted to the intensive care unit | median 87 days (45-124 days) |

Mean age (SD) 42.4 Małe 50,2 % |

Hypertensions ( risk ratio 1.81 (95% confidence interval from 1.10 to 2.96) |

| Zainab Mahmoud et al. (2022) [69] | USA, Washington | 100 | 23% of hospitalized patients and 5% OIT. | Median time 99 days. | Mean age at 46.3 Male 19% | There was a significant increase in median systolic (128 vs. 121.5 mmHg, p = 0.029) and median diastolic (83.5 vs. 76 mmHg, p < 0.001) blood pressure A total of 52 patients had an increase in systolic or diastolic blood pressure of 10 mmHg or more from baseline |

| Nina L. Stute et al. (2022) [70] | USA | 10 | Mild | Mean 41 ± 17, 108 ± 21 and 173 ± 16 days |

20,5 ± 1,2 years Małe 70% |

Resting and reactive BP, but not HR. Decrease during recovery. |

| Rachel E. Szeghy et al (2021) [71] | USA | 30 | Mild | Mean 3-4 weeks. |

Mean age 20 ± 1 years Małe 36,7 % |

Mean systolic and diastolic pressures were greater in the SARS-CoV-2 group compared with the control group. |

| Stephen M. Ratchford et al (2020) [72] | USA, North Carolina | 31 | Mild | 24 ± 6 days | Mean age 20,2 ± 1,1 Małe 29% |

Average systolic pressure: Control: 111,8 ± 13,4 vs SARS-CoV-2: 121,3 ± 12,3 |

| Mahmut Akpek et al. (2021) [73] | Turkey | 153 | 5% hospitalized Mild |

Mean 31.6 ± 5.0 days. |

Mean age 46.5 ± 12.7. Małe 34% |

New onset hypertension was observed in 18 patients at the end of 31.6 ± 5.0 days on average (P <.001). |

| Damsara Nandadewa et al. (2022) [74] | USA, Texas | 38 | Mild | Mean 11 ± 6 weeks |

Control: 23 ±3 yr COVID: 24,5 ±4yr Male 100% |

Taken together, these data suggest that the adverse effects of COVID-19 on BP in young adults are minimal and likely transient. |

| Ternushchak, Tetiana M. Et al (2022) [75] | Ukraine | 115 | mild,moderate | Mean 1.68 ± 1.2 months | Mean age 23.07 ± 1,54. | Patients with long-COVID syndrome have higher mean ABPM diurnal BP values especially at night, significant BP BP variability. |

| Djidji Delalic et al. (2022) [76] | Croatia, Zagreb | 199 | No data | Median 1 months | Mean age 57.3yr Male 46% |

32 (16,08%) of 199 patients studied had either newly verified (15) or worsened existing (17) hypertension. |

| Rebeka DeLorenzo et al. (2020) [77] | Italy, Milan | 185 | Mild, moderate, serve | Median time from hospital discharge 23 days | Mean age 57 male 66,5% |

40 (21,6%) patients had uncontrolled BP requiring therapeutic change. |

| Tisler A et al. (2022) [78] | Estonia | 3949 | 0 - 66,8 % Mild - 28,9 % Moderate - 3.8% Severe - 0,5 % |

Mean 294.9 | Mean age 65.4 Male 45,7% |

Risk of developing HT 2.85 |

| Steinmetz, A. (2023) [79] | Germany | 158 | mild | Median time from covid-19 infection 203 days |

Mean age 48.1 Male 21.4 % |

blood pressure (RR) was normal and decreased over time |

| Oluwabunmi Ogungbe et al.[80] | No data | 442 | mild, only 12% was hospitalized | Median time 12.4 (10.0–15.2) months. | Mean age 45.4 Male 29% |

20% of patients had newly diagnosed hypertension |

| Zhang HG et al (2022)[81] | Germany, France, Italy, Singapore, USA |

414,602 | hospitalized SARS-CoV-2 infection and not | Observation last 1 year | Mean age: no data Male 74% |

Increased risk of arterial hypertension after COVID-19 infection, and it was more significant among ambulatory patients |

| Cohen K et al (2022) [82] | USA | 2 895 943 |

In most cases- hospitalized | Median days78 (30-175) | Mean age 75,7: Male 42% |

HT was determined at a level of 4.43 (2.27 to 6.37) |

| Al-Aly Z et al (2022) [83] | USA | 5.017.43(cases:33 940) | mild, moderate, serve | Follow up-length: 6 months | Mean age: 64,9 Male:89,9% |

The hazard ratio for hypertension was estimated at 1.62. |

| Mizrahi B et al. (2023) [84] |

Israel | 1 913 234 (cases:320 857) | mild | Two time periods after infection Early (30-180 days) Late (180-360 days) |

Median age: 25 years old Male 49,4 % |

Patients with mild COVID-19 were at risk for a hypertension burden of 1.27, and that these effects were resolved within a year from diagnosis. |

| Fernández-Ortega MÁ et al. (2023) [85] |

Mexico | 71 | hospitalized | Two telephone interviews: First after 5 months of discharge, and second at 12 months. |

Age >18 years old Male 65,7% |

Arterial hypertension was one of the observed sequelae. |

| Jennifer K et al. (2022) [86] |

Israel | over 90,000 COVID-19 cases and matched comparison controls | no data | Follow up-length: 14 months | The patients were divided by age into those below and above 40 years old. | Didn’t find differences in the occurrence of hypertension in the control group and after recovering from COVID-19. |

| Pooja Vyas A et al. (2023) [87] |

India | 248 | Hospitalized | Follow up-length: 1 year | Age: 51,16 ± 12,71 Male: 68,1% |

32.3% of individuals experienced new-onset HT |

| Abumayyaleh M et al. (2023) [88] |

International | 8,719 | severe | Follow-up time (months (PCS)) diabeties 2.6 ± 4.6 nondiabeties 2.8 ± 4.9 |

Age: 72.6 +- 12.7 Male: 63.5 |

The incidence of newly diagnosed hypertension slightly lower in DM patients as compared to non-DM patients (0.5% vs. 1.6%; p = 0.18) |

| González-Hermosillo G JA et al. (2023) [89] | Mexico | 45 | hospitalized | 10.8 ±1.9 months from discharge | Age 49.7 ±9.6 Male 50% |

8 (34 %) had abnormal blood pressure response to orthostasis |

| Adam Saloň et al. (2023) [90] | Austria | 35 | hospitalized | Measurements were taken either on day 0 or on day 10 and the second measurement occurred 2 months after hospitalization. | Age 60 ± 10 Male 85% |

Significant changes in systolic blood pressure were observed, ranging from 142 mmHg (SD: 15) to 150 mmHg (SD: 19, p = 0.041). |

| Damsara Nandadeva et al. (2023) [91] | USA, Texas | 23 | no data | Median 15 months (3–30) |

Age group after COVID and control 48 ± 9 vs. 50 ± 13 yr; male 0% |

BPs were elevated in patients with PASC compared with controls |

| Ziyad Al-Aly et al (2021) [92] | USA | 5 808 018 | mild- non hospitalized | Median 126 (81–203) | Mean age 59.09 (15.92) Male 87.96% |

There was an excess burden of hypertension (15.18 (11.53–18.62)) |

| Nishant P. Shah et al (2022) [93] |

USA | 72 706 | no hospitalized | Pandemic months in 2020:April-June vs pre-pandemic January-March 2019 and 2020 |

Pre-COVID-19 vs during COVID-19 mean age 53.0 ± 10.7 years vs 53.3 ± 10.8 male 54% vs 49,4% |

Relative to the pre-pandemic period, during COVID-19 the proportion of participants with a mean monthly BP classified as uncontrolled or severely uncontrolled hypertension |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).