1. Introduction

Long bone growth occurs at specific locations known as growth plates, where chondrocytes undergo a well-regulated process of proliferation and differentiation to form cartilage, which is then replaced by bone via apoptosis of terminally differentiated hypertrophic chondrocytes, and invasion of blood vessels to provide bone cells for bone formation [

1,

2]. This endochondral bone growth process also occurs in the skull bones of the cranial base, upon which the brain sits. In contrast to long bones, the cartilagenous bones of the cranial base are bidirectional, with a central resting zone surrounded on both anterior and posterior sides by proliferating, prehypertrophic and hypertrophic zones [

3,

4]. Cranial base growth plates are known as synchondroses. The two primary synchondroses of the cranial base in mice derive from different embryonic origins. The spheno-occipital synchondrosis (SOS) is primarily of paraxial mesoderm origin while the intersphenoid synchondrosis (ISS) is of cranial neural crest origin [

3]. Abnormal development and premature fusion of cranial base synchondroses is associated with numerous genetic disorders leading to deficient anterior-posterior growth of the skull, associated skull shape defects, and malocclusion (teeth not fitting together appropriately).

Hypophosphatasia is a rare inherited disorder caused by inactivating mutations in the gene (Alpl) that encodes the enzyme tissue non-specific alkaline phosphatase (TNAP). One primary and well-established function of TNAP is to hydrolyze inorganic pyrophosphate (PP

i) into inorganic phosphate (P

i) [

5]. Because PP

i inhibits matrix mineralization while P

i serves as a substrate for hydroxyapatite formation, TNAP activity promotes bone mineralization [

6]. Both humans and mice that are affected by TNAP deficiency exhibit skeletal hypomineralization [

7,

8,

9]. The influence of TNAP on skeletal development is not limited to mineralization. Humans and mice affected by TNAP deficiency also exhibit abnormal growth plates [

8,

10].

We previously investigated skull phenotype changes in the global

Alpl-/- mouse model of hypophosphatasia to better understand mechanisms leading to craniosynostosis (premature fusion of calvarial/skull cap bones leading to high intracranial pressure) in a disorder of bone hypomineralization. We found evidence of skull bone hypomineralization, craniosynostosis and an abnormal skulls shape, which are also seen in infantile hypophosphatasia [

9,

11]. We also found evidence of abnormal development of cranial base synchondroses in these mice [

12]. TNAP is highly expressed in hypertrophic zone chondrocytes [

8] and we found expansion of the hypertrophic zone in global

Alpl -/- mice. Isolation of rib chondrocytes from

Alpl -/- mice revealed a cell autonomous influence of TNAP deficiency on chondrocytes [

13].

Overall, our analyses of global

Alpl -/- mice indicated that TNAP influenced skull bones of cranial neural crest more than those of paraxial mesoderm origin [

12,

13]. In addition, global

Alpl-/- mice are phenotypically normal at birth but rapidly decline in health, with most dying before or shortly after weaning. Therefore, here we investigated the impact of TNAP deletion specifically in tissues of cranial neural crest origin at early and later stages of postnatal development by crossing

P0-Cre promoter expressing mice for cranial neural crest expression [

14], with floxed

Alpl mice.

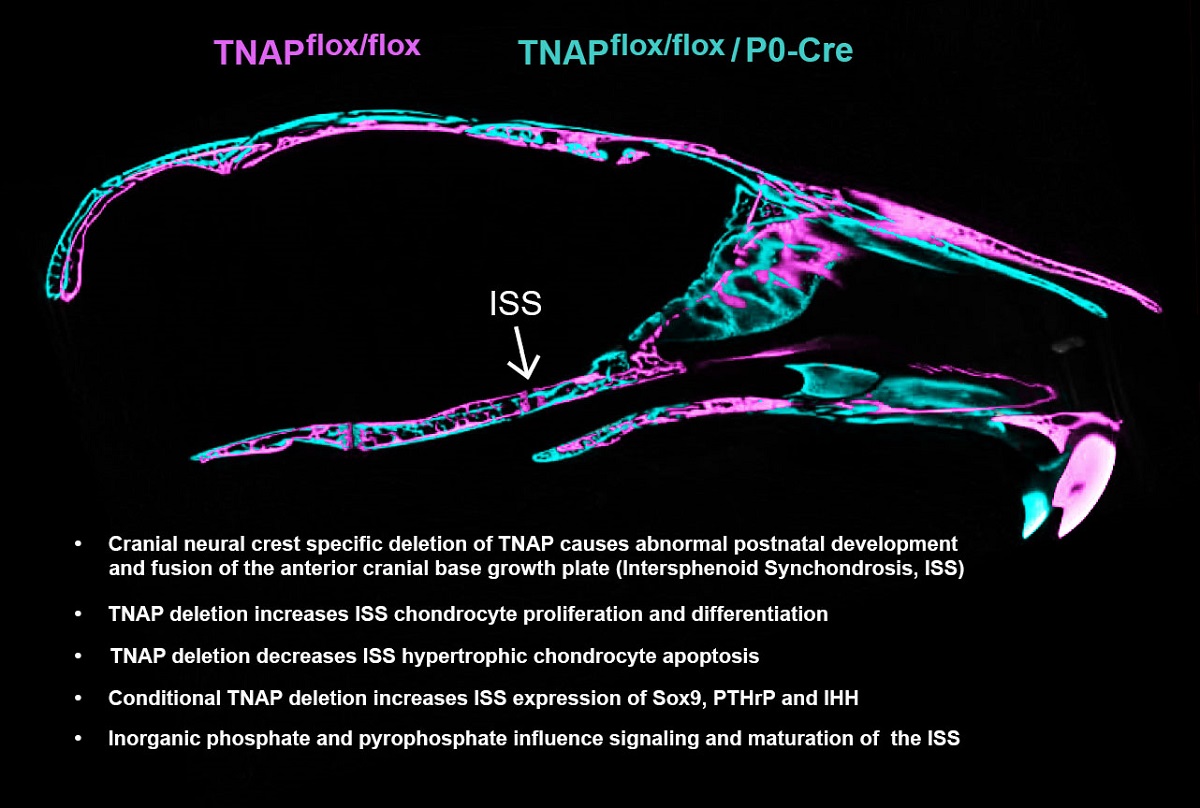

Results demonstrate that deletion of TNAP in cranial neural crest does not cause craniosynostosis, but does cause abnormal development of the anterior (neural crest origin) but not posterior (mesoderm origin) cranial base, and an abnormal skull shape. Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ mice exhibit abnormal chondrocyte proliferation, maturation and apoptosis, as well as aberrant Sox9, PTHrP and IHH signaling in the intersphenoid synchondrosis ISS, as compared to Alplfl/fl mice. Organ culture of wild type cranial base showed that Pi and PPi regulate PTHrP and IHH signaling as well as chondrocyte maturation. Because Pi and PPi levels are anticipated to be down and up respectively upon TNAP deletion, this latter data indicates that the chondrocyte changes in vivo may be mediated by locally increased PPi. Additionally, knockdown of TNAP by shRNA in the O9.1 neural crest cell line showed abnormalities in markers of differentiation and stemness, affirming a cell autonomous role for TNAP in neural crest cells.

3. Discussion

The original goal of this study was to determine if deletion of TNAP in cranial neural crest cells would cause coronal craniosynostosis in mice. This idea was based upon our prior findings which showed that skull bones of cranial neural crest origin (e.g., facial bones, frontal bones) appeared to be more affected than those of mesoderm origin (e.g., parietal bones, occipital bones) and that coronal craniosynostosis occurred in approximately 1/3 of global

Alpl-/- mice on mixed C57BL/6J-129/SvJ genetic background [

12]. This level of incidence of craniosynostosis is similar to that reported to occur in infants and children with hypophosphatasia [

11,

27,

28]. The coronal suture sits at a boundary between mesoderm derived parietal bones and neural crest derived frontal bones [

29]. Early studies indicated that the coronal suture is mesoderm derived [

30,

31] while a more recent study showed that while the midsuture and parietal bone edge of the suture are mesoderm derived, the frontal bone edge of the suture is of cranial neural crest origin [

32]. Therefore, coronal suture fusion could occur via a neural crest cell autonomous or non-cell autonomous effect upon deletion of TNAP in cranial neural crest cells via P0-Cre. Craniosynostosis was not found in any of the

Alplfl/fl;

P0-Cre+ mice by 35 days postnatal, a time at which calvaria growth is essentially complete [

33]. This data indicates that deletion of TNAP in paraxial mesoderm and/or deletion of TNAP in both cranial neural crest and paraxial mesoderm causes craniosynostosis in the

Alpl-/- mouse model of hypophosphatasia, and likely in individuals affected by hypophosphatasia.

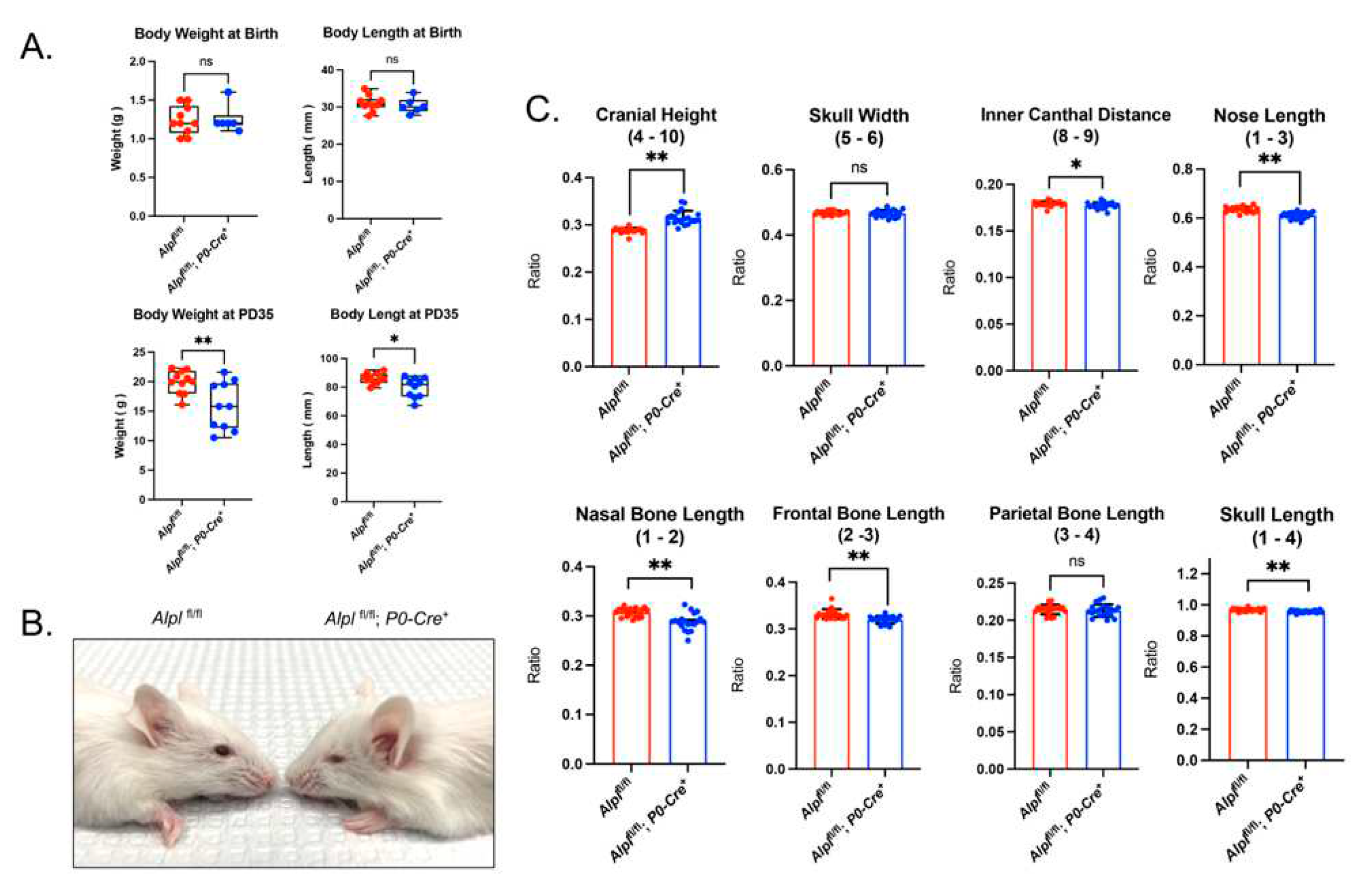

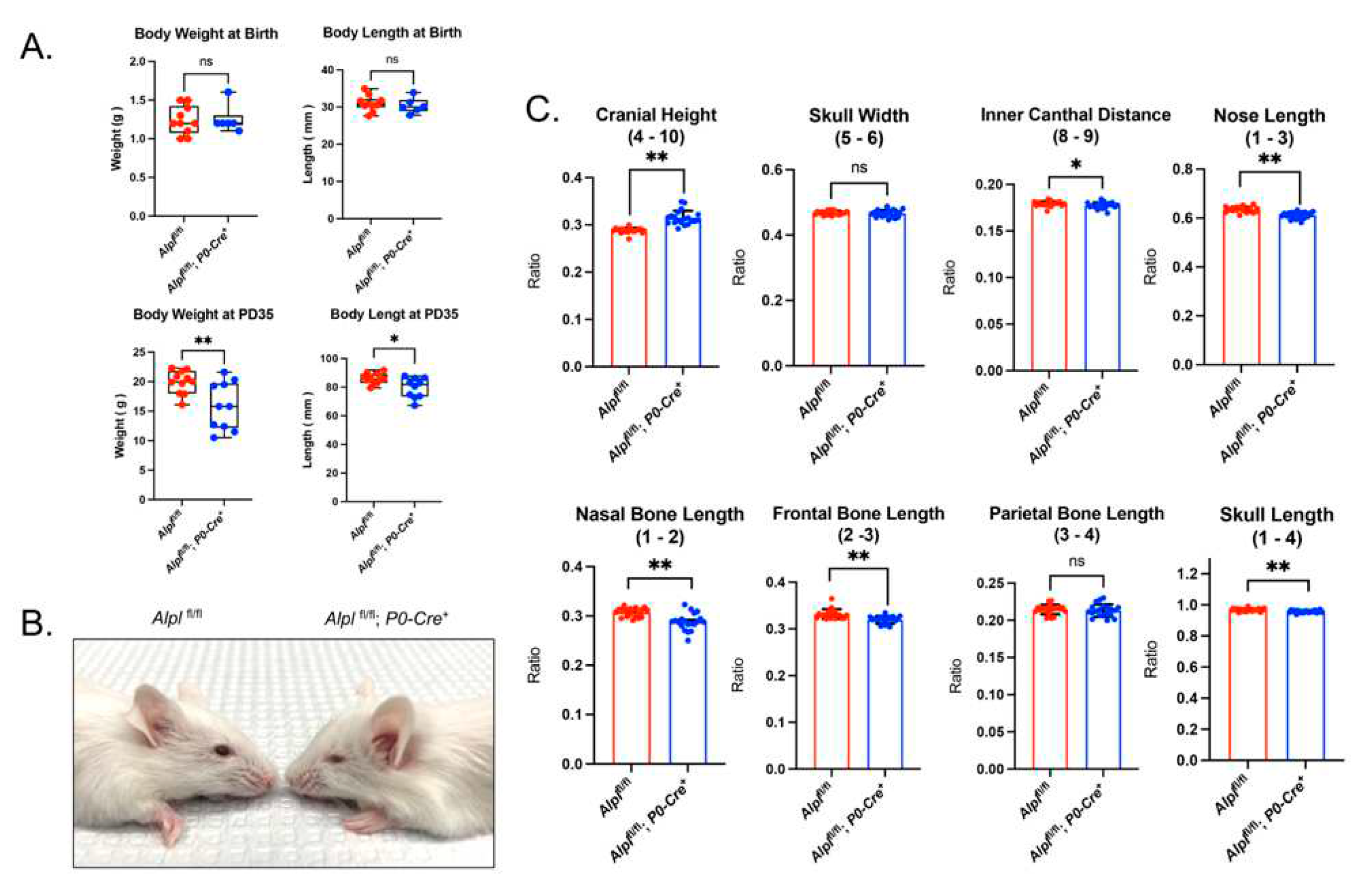

Despite lack of craniosynostosis, the

Alplfl/fl;

P0-Cre+ mice did exhibit an abnormal skull shape that was similar (increase in skull height; shorter anterior-posteriorly) and different (no increase in skull width) compared to the skull shape abnormalities seen in global

Alpl-/- mice. Both global and cranial neural crest specific ablation of TNAP caused decreased anterior cranial base bone lengths and cranial base fusions, which could account for the decrease in total anterior-posterior skull length and compensating increase in skull height. It is also possible that the abnormal skull shape in TNAP deficient mice occurs due to direct effects of TNAP on cranial bone growth. Nasal bones are shorter in both

Alplfl/fl;

P0-Cre+ and

Alpl-/- mice, and we previously reported diminished proliferation and a defect in cell cycle progression in TNAP deficient primary calvarial cells in culture [

34,

35]. TNAP is expressed in cranial bone rudiments several days prior to mineralization, but its function there is not yet established [

36,

37,

38]. Future studies involving a more comprehensive and longitudinal analysis of cranial osteoprogenitor proliferation and cranial bone growth in

Alplfl/fl;

P0-Cre+ and/or

Alpl-/- mice are needed to determine if cranial and/or facial bone growth differences impact the skull shape of TNAP deficient mice.

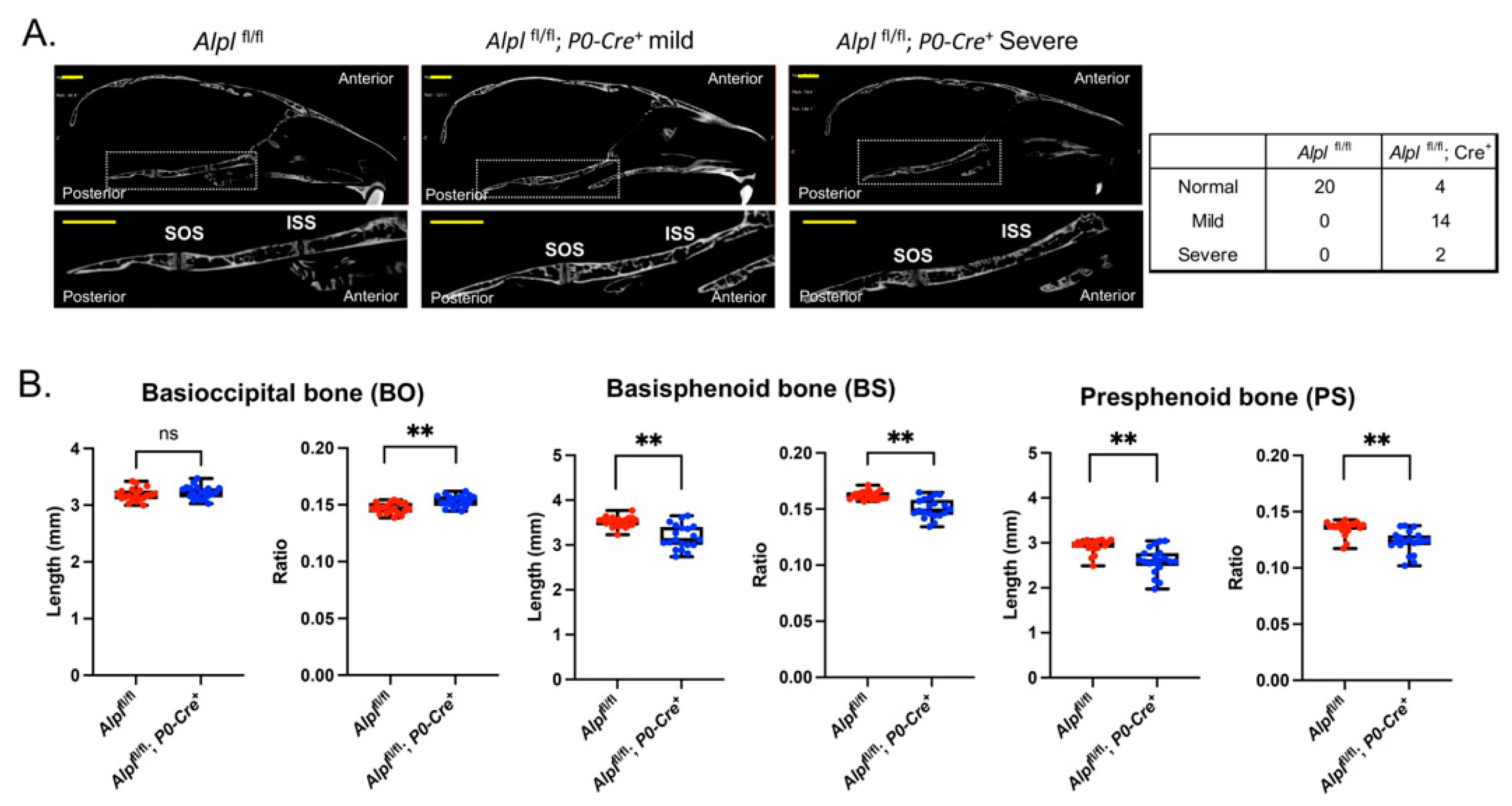

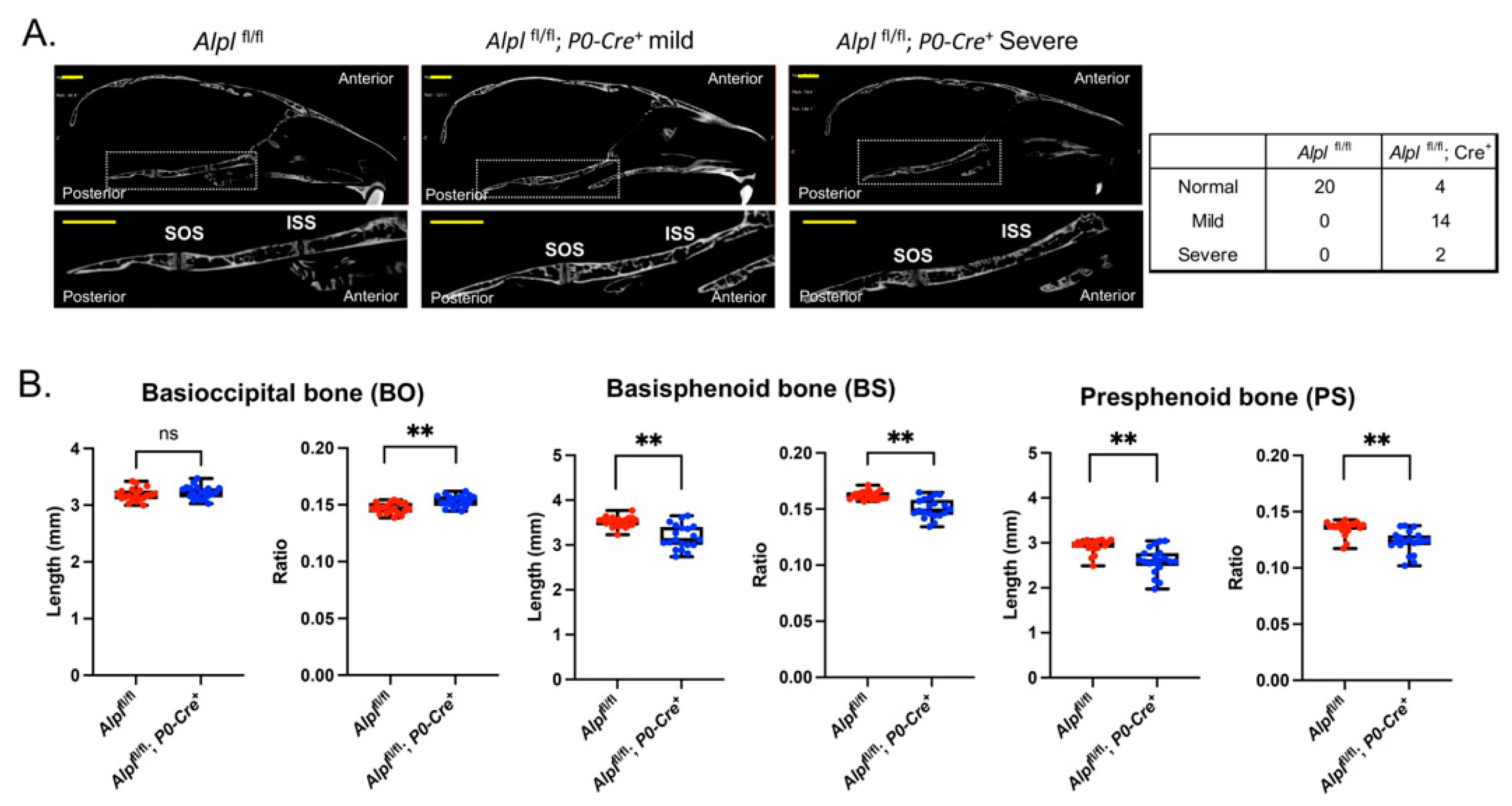

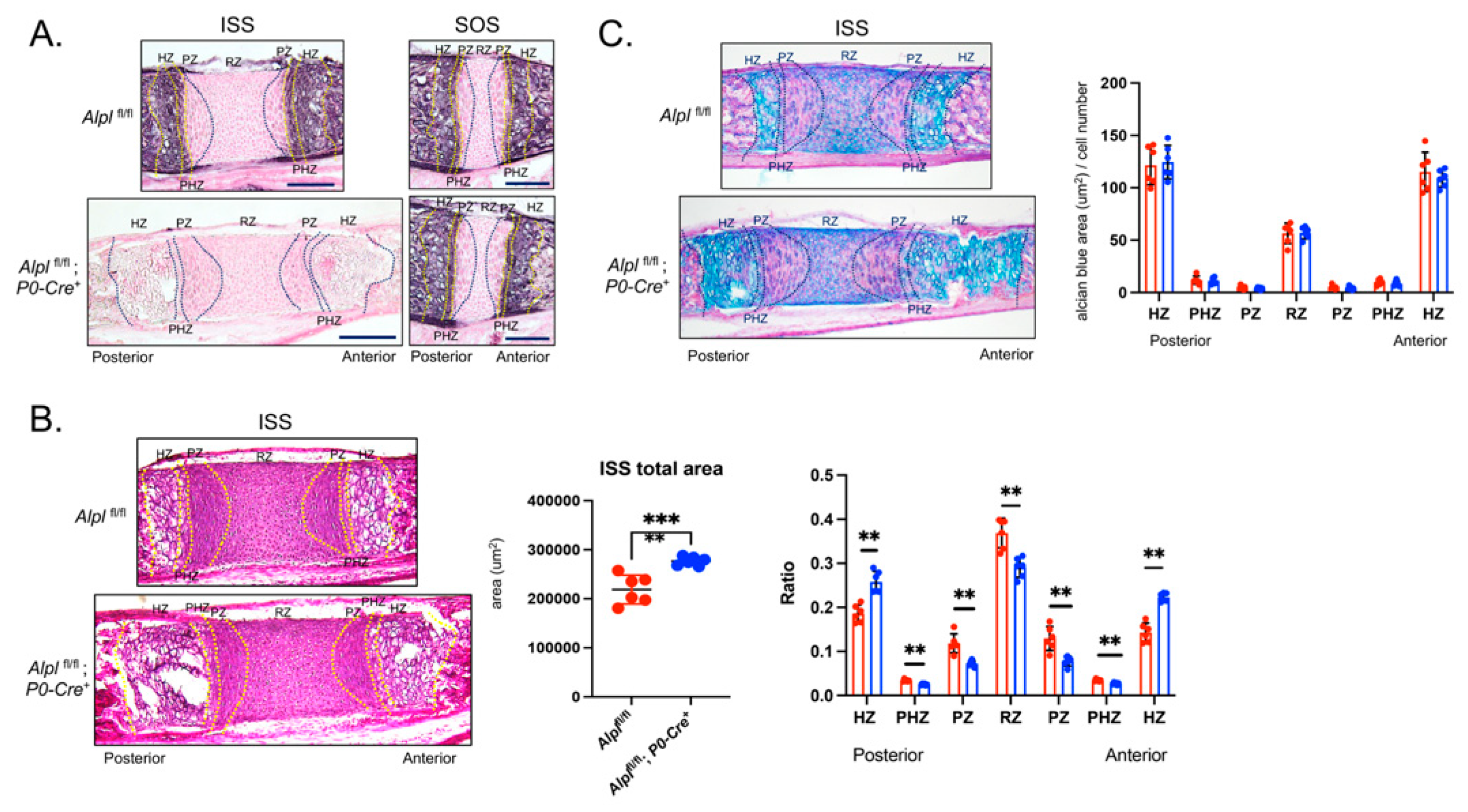

While we previously found dysregulated development of both the ISS and SOS in global

Alpl-/- mice [

13], in

Alplfl/fl;

P0-Cre+ mice only the ISS was abnormal (

Figure 3A) because TNAP was ablated in the ISS but not in the SOS of these mice. Presphenoid and basisphenoid bones surrounding the ISS were shorter, and premature fusion of the ISS was found 80% of

Alplfl/fl;

P0-Cre+ as compared to

Alplfl/fl mice at 35 days postnatal. Histomorphometry of H&E stained 5-day-old ISS sections revealed significantly increased hypertrophic zone widths in the

Alplfl/fl;

P0-Cre+ mice, similar to that seen in global

Alpl-/- mice [

13]. This finding indicates that TNAP deficiency in local growth plate prehypertrophic and hypertrophic chondrocytes likely causes chondrocyte maturation defects leading to cranial base defects, because TNAP is normally expressed in these cells.

Hypertrophic zone chondrocyte apoptosis was decreased in

Alplfl/fl;

P0-Cre+ mice, accounting for the expanded hypertrophic zone width, and similar to that seen in global

Alplfl/fl mice [

13], and in mouse models of hypophosphatemic rickets [

39]. Proliferation was increased in the resting and proliferation zones of

Alplfl/fl;

P0-Cre+ mice, yet these zones were not increased in size compared to control mice, which could be explained if the proliferating cells of

Alplfl/fl;

P0-Cre+ mice were also enhanced in differentiation. Staining for Col X was increased in the

Alplfl/fl;

P0-Cre+ as compared to

Alplfl/fl mice, indicating that premature differentiation was occurring in addition to increased proliferation. Sox9 expression was up in both resting and hypertrophic zones. Sox9 is a master transcriptional regulator of chondrocytes that promotes chondrocyte proliferation and inhibits maturation in resting and proliferating zones, while promoting maturation and hypertrophy in prehypertrophic zones, via differential expression of co-transcription factors Sox5, Sox6m Runx2 and Mef2c [

40,

41,

42]. Sox9 could therefore be mediating the ISS chondrocyte changes seen downstream of TNAP ablation in cranial neural crest cells. Col2 expression was not altered in

Alplfl/fl;

P0-Cre+ ISS (Supplemental

Figure S2).

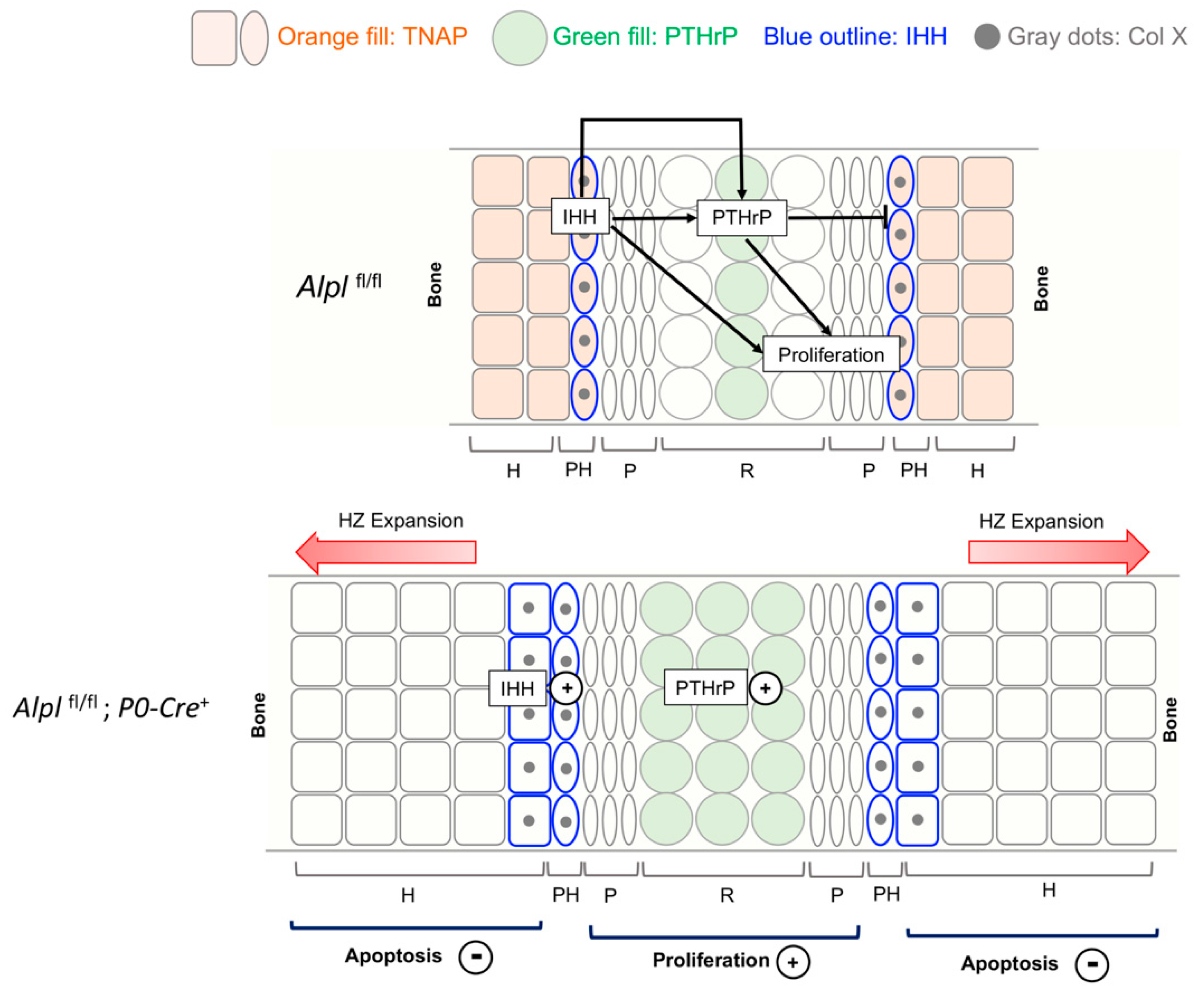

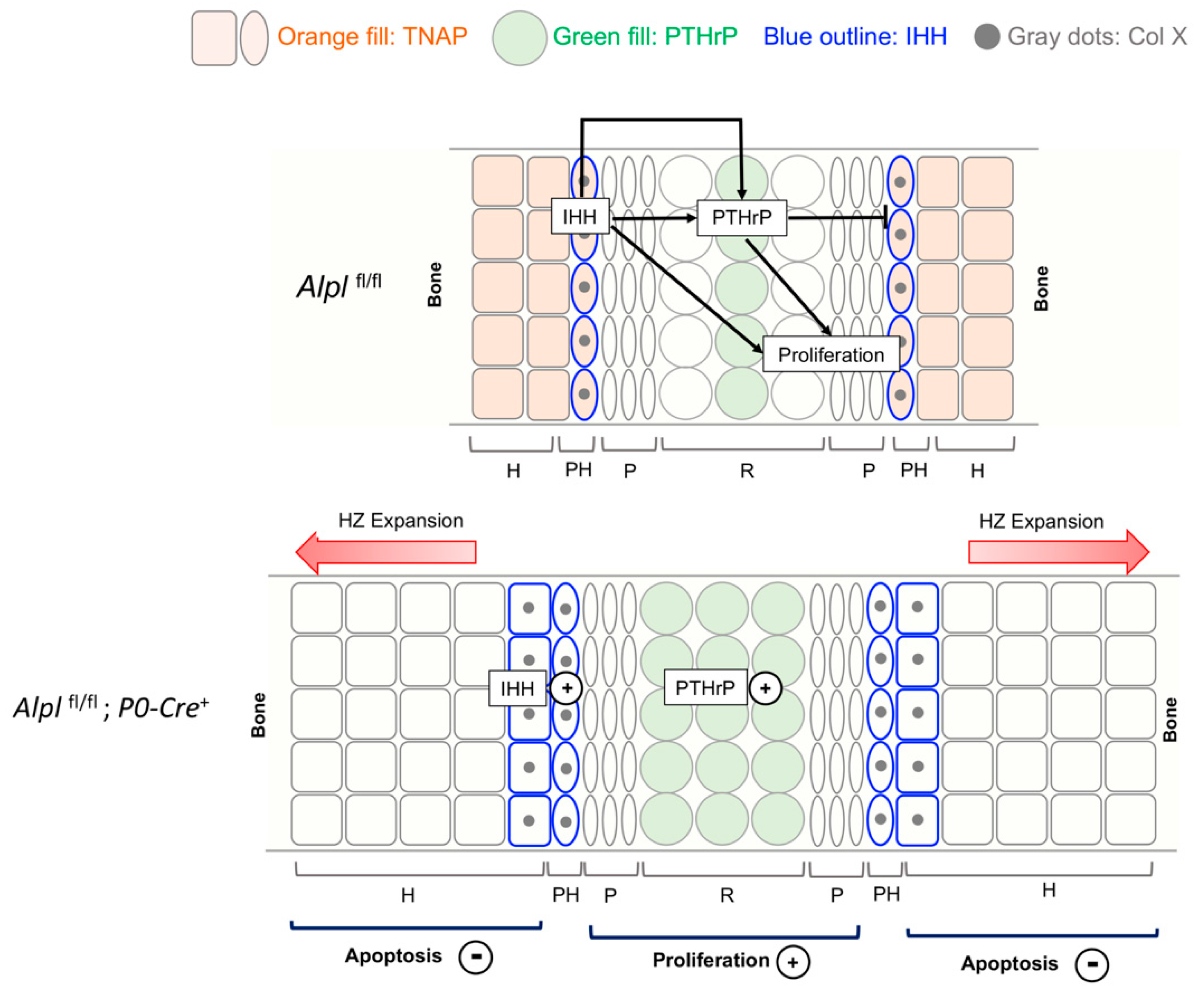

Indian Hedgehog (IHH) and Parathyroid Hormone Related Peptide (PTHrP) have long been known to play an essential role in chondrocyte proliferation and maturation in long bone growth growth plates [

15,

43,

44]. The IHH-PTHrP feedback loop is also considered essential for cranial base growth plates [

45,

46]. PTHrP is secreted from resting zone chondrocytes to promote proliferation and inhibit chondrocyte maturation, while also inhibiting the production of IHH. More distant cells in the prehypertrophic and hypertrophic zones express IHH, which in turn promotes proliferation and differentiation, while also stimulating PTHrP expression to impact resting zone chondrocytes. Because this signaling feedback loop is considered essential for regulation of growth plates and subsequent endochondral bone growth, we investigated expression of IHH and PTHrP in the ISS of

Alplfl/fl;

P0-Cre+ mice as compared to control mice. We found increased expression of IHH in prehypertrophic and hypertrophic zones, in addition to increased expression of PTHrP in hypertrophic and resting zones of

Alplfl/fl;

P0-Cre+ ISS. Because TNAP and IHH are normally expressed in prehypertrophic and hypertrophic zones, our data suggests that TNAP deficiency in these zones causes high IHH expression, in turn leading to ectopic expression of PTHrP in the hypertrophic zone plus increased PTHrP expression in the resting zone, where PTHrP is normally expressed.

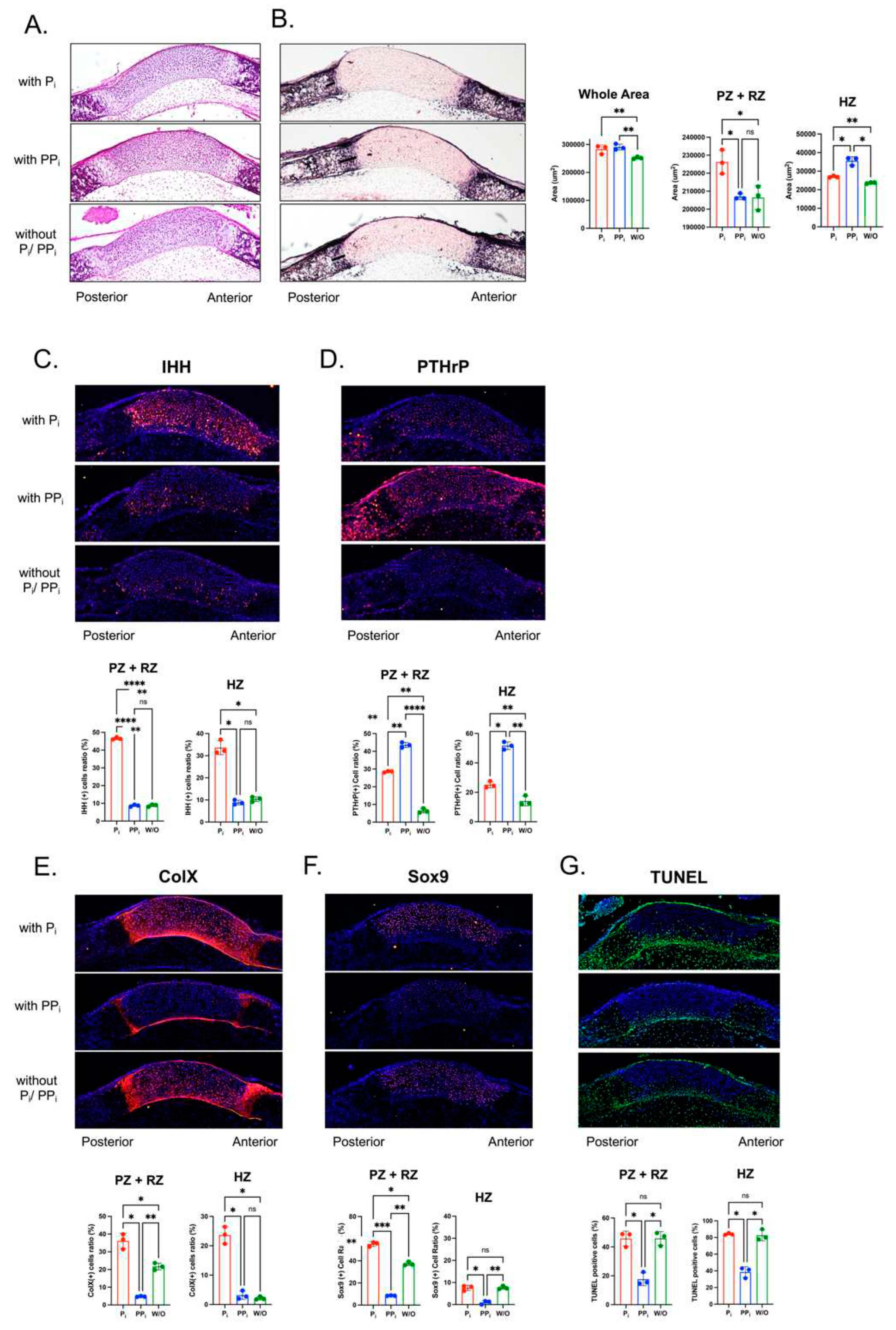

Apoptosis of hypertrophic zone chondrocytes was previously shown to be stimulated by inorganic phosphate (P

i) and inhibited by inorganic pyrophosphate (PP

i) [

20,

39]. In TNAP deficient cells, P

i levels should decrease while PP

i levels increase. To distinguish between P

i and PP

i effects on ISS hypertrophic zone chondrocyte apoptosis, we next isolated the ISS from wild type mice and cultured them for five days in media +/- P

i and PP

i. Treatment with P

i increased resting zone and proliferating zone widths, which is not entirely surprising considering that P

i is a known mitogen [

18]. We were surprised to find that culture with P

i increased ISS hypertrophic zone widths because, as stated above, P

i was previously shown to be essential for promoting hypertrophic chondrocyte apoptosis in mice. Treatment with PP

i increased the hypertrophic chondrocyte width and decreased apoptosis, demonstrating that high PP

i levels downstream of TNAP deficiency [

8,

47] potentially caused the increased ISS hypertrophic zone widths seen in the

Alplfl/fl;

P0-Cre+ mice.

We next examined expression of IHH and PTHrP upon treatment +/- Pi and PPi. We found that Pi but not PPi increased expression of IHH. Treatment with Pi also increased expression of PTHrp, but PPi did so to a much greater extent. Because Pi levels are anticipated to be low in TNAP deficient cells and tissues, this data again supports a hypothesis that high PPi levels mediate some of the abnormal ISS development seen in Alplfl/fl;P0-Cre+ as compared to control mice. We also found that Pi increased while PPi decreased Col X and Sox9 expression which is not consistent with the idea that decreased Pi or increased PPi downstream of TNAP deficiency in Alplfl/fl;P0-Cre+ ISS mediated the increase Col X and Sox9 expression found in vivo. The differences seen between organ culture and in vivo immunofluorescent expression of IHH, PTHrP, Col X and Sox9 could be explained by the absence of factors that may mediate downstream effects of Pi in organ culture that are present in vivo, and/or that we utilized newborn ISS for the organ culture studies.

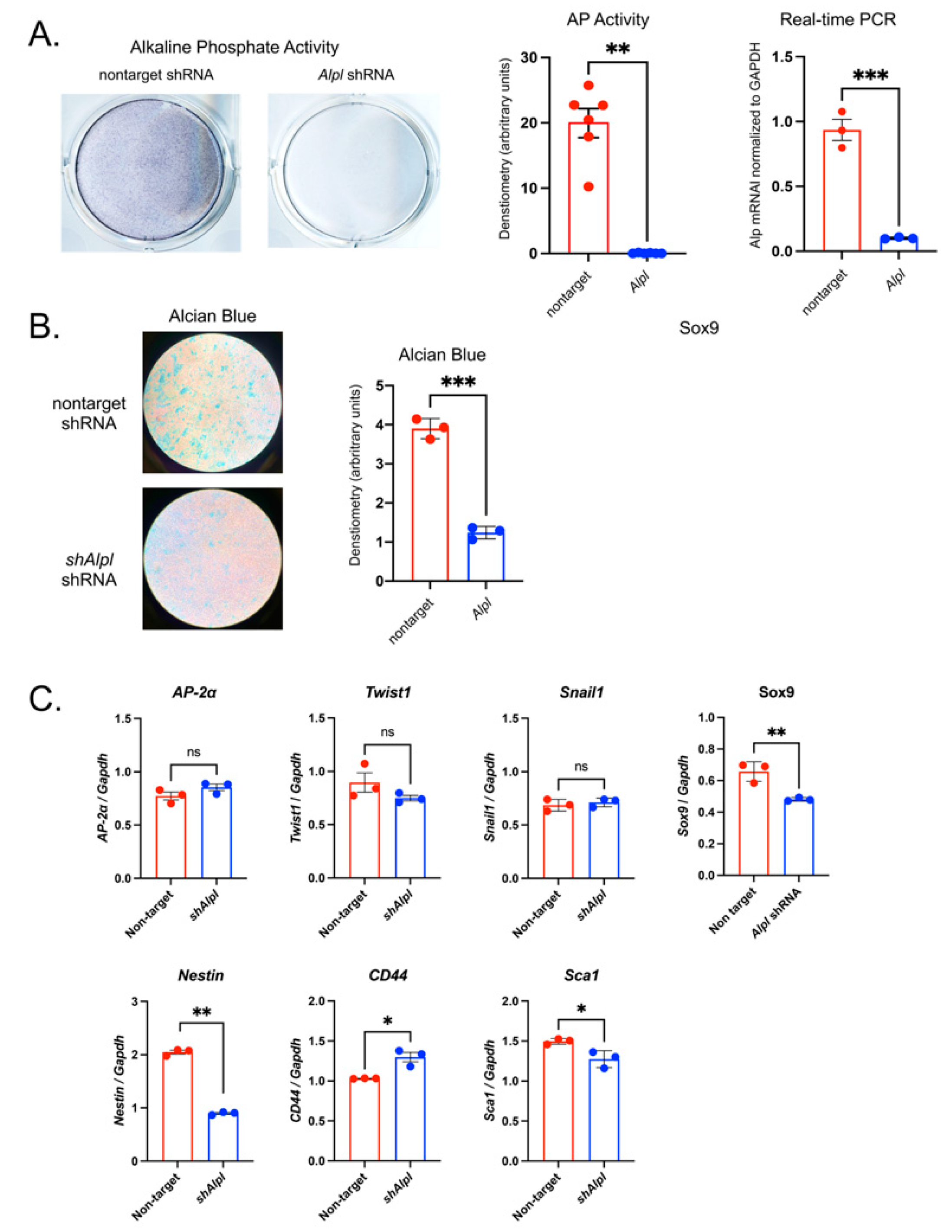

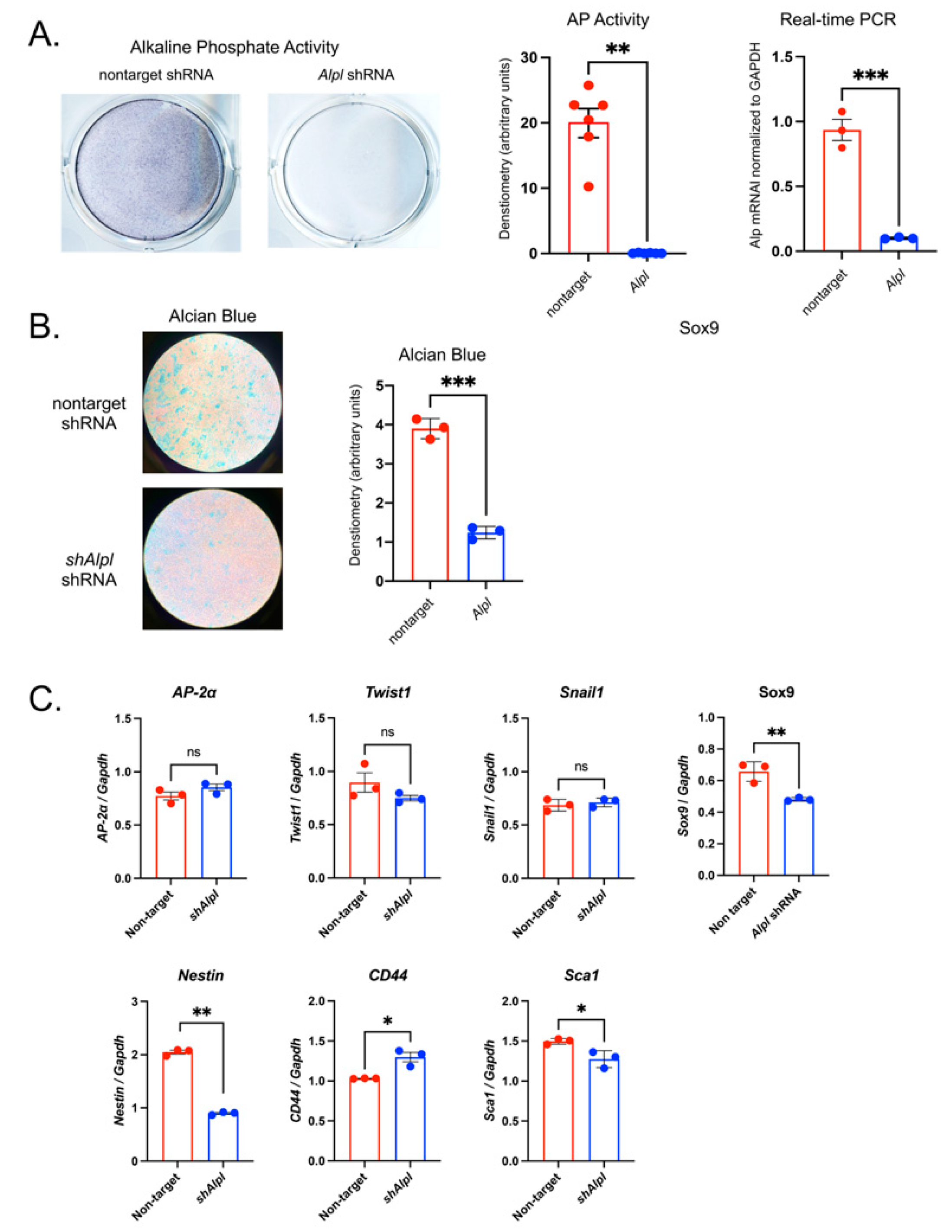

To establish effects of TNAP deficiency on earlier lineage neural crest cells, we transduced the O9.1 neural crest cell line with TNAP or control nontarget shRNA. The O9-1 cell line stably expresses stem cell markers and neural crest markers, and are capable of contributing to cranial neural crest fates [

26,

48]. We then assessed expression of stem cell and neural crest markers in these cells. Minimal differences were seen in known markers of neural crest between the cell genotypes, other than Sox9. Sox9 is known to be essential in early neural crest cells likely for maintaining pluripotency [

49] and later in establishing a chondrogenic lineage [

50], plus its previously discussed ability to control the proliferation and maturation of growth plate chondrocytes [

51]. Lower Sox9 expression in the O9.1 cells could be an artifact of in vitro experimentation or indicate that TNAP deficiency in pluripotent cranial neural crest cells has dual effects, one earlier in development that lowers the tendency for initial chondrocyte fate commitment and one later in development (studied here) for altering growth plate chondrocyte maturation. Suppression of TNAP by shRNA decreased expression of stem cell markers Nestin and Sca1 but increased expression of CD44. Future studies are needed to establish a role for TNAP in neural crest chondrocyte lineage specification.

Overall, our results validate that TNAP expression is required in cranial neural crest cells for normal anterior cranial base development, but not for craniosynostosis. TNAP deficiency in the intersphenoid synchondrosis (ISS) leads to aberrant Sox9 and IHH-PTHrP signaling; with increased proliferation, abnormal chondrocyte maturation and diminished apoptosis. Cranial base organ culture experiments appear to demonstrate that the apoptotic abnormalities are also mediated at least in part by increased levels of PPi that occur downstream of TNAP deficiency.

Figure 8.

Model depicting the major changes caused by conditional Alpl deletion in cranial base development. The intersphenoidal synchondrosis (ISS) is a cranial base growth plate that grows in an analogous fashion to long bone growth plates, but is bidirectional in anatomy and function. The IHH-PTHrP signaling loop is essential for control of chondrocyte proliferation and maturation. IHH is expressed primarily in prehypertrophic chondrocytes where PTHrP is low. IHH acts to promote chondrocyte proliferation and chondrocyte maturation, while also stimulating PTHrP expression. PTHrP acts on resting zone chondrocytes to maintain chondrocyte proliferation and inhibit differentiation/maturation. In control mice, TNAP is expressed in prehypertrophic zone and hypertrophic zone cells. Ablation of TNAP increases both IHH and PTHrP expression. Ablation of TNAP also increases proliferation, increases ColX expression and diminishes apoptosis leading to hypertrophic zone expansion. While not shown here, ablation of TNAP via cranial neural crest P0-Cre also increases expression of Sox9 in both resting and prehypertrophic chondrocytes. Sox9 is a master transcriptional regulator that promotes chondrocyte proliferation and inhibits maturation in resting and proliferating zones, while promoting maturation and hypertrophy in prehypertrophic zones, via differential expression of co-transcription factors. Because TNAP is co-expressed with Sox9 and with IHH in control mice, we hypothesize that TNAP ablation increases chondrocyte proliferation, increases ColX expression and diminishes apoptosis through increased Sox9 expression and/or increased IHH expression (IHH in turn would increase PTHrP expression). Increased levels of inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) may also contribute to the diminished apoptosis and hypertrophic zone expansion in TNAP deficient mice, as this effect was strongly seen in the ISS organ culture studies.

Figure 8.

Model depicting the major changes caused by conditional Alpl deletion in cranial base development. The intersphenoidal synchondrosis (ISS) is a cranial base growth plate that grows in an analogous fashion to long bone growth plates, but is bidirectional in anatomy and function. The IHH-PTHrP signaling loop is essential for control of chondrocyte proliferation and maturation. IHH is expressed primarily in prehypertrophic chondrocytes where PTHrP is low. IHH acts to promote chondrocyte proliferation and chondrocyte maturation, while also stimulating PTHrP expression. PTHrP acts on resting zone chondrocytes to maintain chondrocyte proliferation and inhibit differentiation/maturation. In control mice, TNAP is expressed in prehypertrophic zone and hypertrophic zone cells. Ablation of TNAP increases both IHH and PTHrP expression. Ablation of TNAP also increases proliferation, increases ColX expression and diminishes apoptosis leading to hypertrophic zone expansion. While not shown here, ablation of TNAP via cranial neural crest P0-Cre also increases expression of Sox9 in both resting and prehypertrophic chondrocytes. Sox9 is a master transcriptional regulator that promotes chondrocyte proliferation and inhibits maturation in resting and proliferating zones, while promoting maturation and hypertrophy in prehypertrophic zones, via differential expression of co-transcription factors. Because TNAP is co-expressed with Sox9 and with IHH in control mice, we hypothesize that TNAP ablation increases chondrocyte proliferation, increases ColX expression and diminishes apoptosis through increased Sox9 expression and/or increased IHH expression (IHH in turn would increase PTHrP expression). Increased levels of inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) may also contribute to the diminished apoptosis and hypertrophic zone expansion in TNAP deficient mice, as this effect was strongly seen in the ISS organ culture studies.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

Mice carrying Cre recombinase driven by the protein zero (P0) promoter (P0-Cre mouse, C57BL/6J-Tg(P0-Cre)94Imeg) were generously provided by Yuji Mishina (University of Michigan, School of Dentistry, Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Floxed Alpl (Alplfl/+) were generously provided by José Luis Millán (Sanford Children’s Health Research Center, Human Genetics Program, La Jolla, CA, USA). Alplfl/+ and P0-Cre mice were bred onto a 97% 129/SvJ (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME, USA) and 3% C57BL/6J (Charles River Laboratory, Wilmington, MA, USA) genetic background for a minimum of 7 generations prior to breeding for experimentation. P0-Cre transgenic mice were bred with Alplfl/+ mice to generate Alplfl/+; P0-Cre+ mice, which were then bred with Alplfl/fl mice to generate Alplfl/fl;P0-Cre, Alplfl/fl and Alplfl/+ mice. Litter-matched Alplfl/fl;P0-Cre+ (experimental mice) and Alplfl/fl (control mice) were used in this study. The genotyping of the mice was determined by the following specific primers using tail DNA. Primer A (5’-TTG CGA TGT GTG AAG ATG TCC-3’) and B (5’-GGC TTG CTG TCG CCA GTA AC-3’) were used to detect the flox allele (expected size: wild type band is 224 bp, floxed band is 258 bp). Primer C (5’-ATG GTG TTG CCG CGC CAT CTG CCA-3’) and D (5’- CTA ATC GCC ATC TTC CAG CAG GCG-3’) were used to detect the Cre-recombined allele (expected size: 298 bp). Animals were maintained and used in compliance with institutional animal care protocols of the University of Michigan’s University Committee on Use and Care of Animals, and in accordance with federal guidelines for and use and care of animals in research. Because all the transgenic animals remained healthy and viable, no animals were excluded from the study. The experimental unit for in vivo studies was one mouse. Sample sizes for postnatal day 5 analyses were n=6. Sample sizes for postnatal day 35 analyses were n=20. The larger sample size used in day 35 analyses was based upon prior data generated by our lab which indicated need for this large of a sample size to reach statistical conclusions regarding craniosynostosis and cranial base fusions, due to phenotype severity variability seen in Alpl-/- mice. Mouse genotype was blinded for analyses then re-identified for statistical comparisons. Primary endpoints were to confirm knockout of TNAP in cranial neural crest but not paraxial mesoderm derived skull tissues (eg: the ISS but not the SOS), incidence of craniosynostosis and incidence cranial base fusions. Secondary endpoints were analyses of cranial base zones, as well as chondrocyte signaling, proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis.

4.2. Nano Computed Tomography

Whole skulls of 35-day-old Alplfl/fl;P0-Cre+ and Alplfl/fl mice were collected, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, serially dehydrated and stored in 70% ethanol at 4℃ until scan. Whole skull specimens were scanned at 80 kV and 400 µA with a 0.381 mm aluminum filter in a Nanotom M scanner (Waygate Technologies LP, Pasadena, Texas). In total, 1500 projection images were acquired at a source-to-axis distance of 48 mm for a resolution of 12 µm/voxel. Three-dimensional reconstructed nano-CT images were analyzed using Dragonfly image analysis software (Version 2021.1.0.977; Object Research Systems, Inc, Montreal Canada). No significant difference between genders was found; therefore, genders were combined for analyses (n = 20 per Alplfl/fl;P0-Cre+ and Alplfl/fl mice).

4.3. Linear Skull and Cranial Base Measurements

Linear craniofacial measurements between landmarks were calculated using an electronic digital caliper (Automation and Metrology Inc., Mentor, OH, USA) on whole dissected skulls. Linear skull and cranial base measurements were performed using previously defined skull landmarks [

13,

52,

53] (Supplemental

Figure S1). Measurements were performed twice for each measurement with the average used as a given measurement per mouse. The measurements included standard craniofacial measurements used by the Craniofacial Mutant Mouse Resource of Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME USA), which are nasal bone length (landmark 1-2), nose length (landmark 1-3), inner canthal distance (landmark 8-9), skull width (landmark 5-6), skull length (landmark 1-7), frontal bone length (landmark 2-3), and parietal bone length (landmark 3-4). The Jackson Laboratory skull height measurement was substituted with a cranial height measurement taken between pari (landmark 4) and the inferior portion of the spheno-occipital synchondrosis (landmark 10), due to the elimination of the mandible in our study.

4.4. Histology and Histomorphometry

Whole skulls were dissected from Alplfl/fl;P0-Cre+ and Alplfl/fl mice at postnatal 0 and 5 days. The skulls were fixed in the 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for 24 hours. The specimens were cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in 0.01 mol/L PBS, embedded in an embedding medium (O. C. T. compound, Fisher Healthcare, USA), frozen on dry ice, and kept at -80℃ until sectioning. Serial sagittal sections were cut at thickness of 14 µm and processed for H&E (hematoxylin and eosin) staining, alcian blue staining, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining or immunofluorescence. Zone area, zone fraction and cell number in synchondrosis were analyzed using Image J software (version 1.50i).

For alcian blue staining, the specimens were brought to room temperature (RT), then fixed by 4% PFA for 15 min, washed in PBS 5 min × 3 times, treated with 3% acetic acid for 5 min then Alcian blue 8GX (Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min, then counterstained with nuclear fast red. For ALP activity staining, the specimens were brought to room temperature, then washed in acetone for 15 min, TBST (Tris-buffered saline pH 8.0, 1% Tween-20) for 60 min, then NTMT (0.1 M NaCl, 0.1 M Tris-HCl pH 9.5, 50 mM MgCl2, 0.1% Tween-20) for 60 min at 4℃, and stained with nitro-blue tetrazolium chloride (NBT) and bromo-4-chloro-3’-indolyphosphate p-toluidine (BCIP) at room temperature for 10 min, then counterstained with nuclear fast red.

4.5. Immunofluoresence

Primary antibodies and their corresponding antigen retrieval methods are shown in

Table 1. Sections were postfixed in 4% PFA for 10 minutes at room temperature. For immunostaining, sections were permeabilized with 0.3M glycine/0.25% Triton X/PBS for 60min, blocked with 5% skim milk/10% goat serum/ 0.05% Triton X/PBS for 60 minutes, and incubated with each antibody overnight at 4℃, and subsequently with goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody-conjugated Alexa Fluor 555 (1:400, Invitrogen) with 4’6-diamidino-2-phenylindoledihydrochloride (DAPI; ProLong Gold antifade reagent, Invitrogen) staining for the nucleus. Apoptotic cells were detected using TUNEL-based in situ cell death detection kit (Invitrogen) according to the product’s procedure. We performed the quantification of TUNEL by counting all TUNEL+ cells relative to the total area of the anterior and/or posterior hypertrophic zones of the ISS or SOS. Immunofluorescence negative controls were performed by replacing the primary antibody with PBS: these showed no specific immunoreaction (data not shown). Digital images were taken using a Nikon Eclipse E800 microscope with attached CCD camera. To create dual-color images, the images of the same field obtained with fluorochrome were merged using image-processing software (Affinity Photo).

4.6. O9.1 Cell Culture and Procedures

O9-1 cells (neural crest cell line) were cultured in basal media containing DMEM (Gibco), 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 0.1mM non-essential amino acids (Gibco), 2mM L-glutamine (Gibco), 55µM beta-mercaptoethanol (Gibco), 1mM sodium pyruvate (Gibco), 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Gibco) that had been conditioned by SNL feeder cells (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) overnight. The media was filtered (0.22-µm pore size) and supplemented with 25 ng/mL basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) and 1,000U/mL leukemia inhibitory factor (LIF; Millipore, Burlington, MA, USA).

O9-1 cells were expanded on a fibronectin (Sigma-Aldrich)-coated plate. O9-1 cells were seeded at 10,000-15,000 cells/cm2, followed by 3 days of culture to reach confluence for freezing or plating for experimentation. To induce chondrocyte differentiation, monolayer culture was initially cultured in early differentiation media (α-minimum essential medium (MEM), 10% FBS, 100U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, 0.1mM dexamethasone, 5mM NaPO4, 50 µg/mL ascorbic acid, and 100ng/mL BMP2 (R&D Systems) for 3 days. Then, cells were trypsinized and cultured in a micromass format in a chondrogenic medium (α-MEM, 5% FBS, 1% ITS; Sigma-Aldrich Burlington, MA, USA), 100U/mL penicillin, 100 µg/mL streptomycin, 10 ng/mL TGF-β3 (R&D Systems), 50 µg/mL ascorbic acid, 10 ng/mL BMP2, 0.1µM dexamethasone, and 1mM sodium pyruvate] for an additional 7 days.

Alkaline phosphatase enzyme activity was assayed using the colorimetric substrate, NBT/ BCIP (Sigma-Aldrich). For alcian blue staining, cells were washed with phosphate buffered saline, fixed with 10% formalin, then stained with a 1% alcian blue solution (1% alcian blue in 60% ethanol/40% acetic acid). After destaining in 60% ethanol/40% acetic acid, cells were photographed with microscope, and each well was scanned. Scanned wells (n=3 per genotype) were quantified by densitometry using Image J software.

4.7. RNA Analysis

For RNA analysis, RNA was isolated using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) following manufacturer protocols. mRNA levels were assayed by reverse transcription and real time PCR. Real time PCR was performed utilizing the murine Gapdh primer/probe set Mm99999915_g1, the murine Alpl primer/probe set Mm00475834_m1, the murine Sox9 primer/probe set Mm00448840_m1, the murine AP-2α primer/probe set Mm00495574_m1 , the murine Twist1 primer/probe set Mm00442036_m1, the murine Snail1 primer/probe set Mm00441533_m1 (neural crest cell markers), the murine Nestin primer/probe set Mm00450205_m1, the murine primer/probe set CD44 Mm01277163_m1, the murine Sca1 primer/probe set Mm00618853_m1 (Stem cell markers), and Taqman Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Waltham MA, USA). Real-time PCR was performed on a ViiA7 thermocycler (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) and quantified by comparison to standard curve. Results are presented as normalized to Gapdh mRNA levels.

4.8. Organ Culture and Procedures

Cranial baes structures were dissected at birth from mice and cultured in 12-well plates. Cultures were submerged in 1mL Dulbecco’s modified Eagle (-) medium (DMEM, Gibco, Billings, MT, USA), containing with 100 µg/mL Ascorbic acid, 2mg/ml insulin/transferrin/selenium (ITS, Sigma-Aldrich), 100 U/mL Penicillin G and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Gibco), and amphotericin B (Gibco). Experimental cultures were exposed to sodium Pi at 1 mM, or sodium PPi at 0.5mM, or without PPi/Pi. Medium was changed every two days.

4.9. Statistical Analyses

All quantified data are presented as means +/− standard deviations. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). The student’s t-test was applied for two-group comparisons and the ANOVA was used for multiple-group comparisons. Fishers exact test was used to analyze the incidence of ISS fusion in 35-day-old mice. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Figure 1.

Cranial neural crest cell-specific deletion of Alpl leads to skull shape defects. (A) Body weight and body length in newborns is not different between genotypes. Body weight and body length are decreased in Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ as compared to Alplfl/fl mice by postnatal day 35. (P35) (B) Representative 35 day-old mice are shown. Note midface hypoplasia evident in Alpl fl/fl; P0-Cre+ but not in Alplfl/fl mice. (C) Linear skull measurements normalized to a total skull length measurement to take into account differences in skull size between genotypes demonstrate craniofacial shape abnormalities in Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ mice at P35. As compared to Alplfl/fl mice, Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ mice exhibit significantly increased cranial height, with significantly diminished inner canthal distance, nose length, nasal bone length, frontal bone length, and skull length. Skull width and parietal bone length are not different between genotypes. Overall, the skull shape of Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ mice is proportionally shorter in anterior-posterior length, and taller in height than the skull shape of Alplfl/fl mice. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01 vs Alplfl/fl . Red = Alplfl/fl , Blue =Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+. n=20 per genotype.

Figure 1.

Cranial neural crest cell-specific deletion of Alpl leads to skull shape defects. (A) Body weight and body length in newborns is not different between genotypes. Body weight and body length are decreased in Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ as compared to Alplfl/fl mice by postnatal day 35. (P35) (B) Representative 35 day-old mice are shown. Note midface hypoplasia evident in Alpl fl/fl; P0-Cre+ but not in Alplfl/fl mice. (C) Linear skull measurements normalized to a total skull length measurement to take into account differences in skull size between genotypes demonstrate craniofacial shape abnormalities in Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ mice at P35. As compared to Alplfl/fl mice, Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ mice exhibit significantly increased cranial height, with significantly diminished inner canthal distance, nose length, nasal bone length, frontal bone length, and skull length. Skull width and parietal bone length are not different between genotypes. Overall, the skull shape of Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ mice is proportionally shorter in anterior-posterior length, and taller in height than the skull shape of Alplfl/fl mice. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01 vs Alplfl/fl . Red = Alplfl/fl , Blue =Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+. n=20 per genotype.

Figure 2.

Cranial neural crest cell-specific deletion of Alpl leads to cranial base defects. (A) Nano-CT sagittal slice images of representative 35 day-old Alplfl/fl and Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ skulls are shown. The dotted box and its magnified image show the cranial base. SOS = spheno-occipital synchondrosis; ISS = intersphenoid synchondrosis. Skulls of Alplfl/fl, P0-Cre+ mice showed partial to complete fusion of the ISS, which was not seen in any Alplfl/fl mice. The SOS appeared normal in all mice regardless of genotype. (B) Nano-CT based measurements of cranial base bone lengths, and the lengths as normalized by total skull length to account for skull size differences, between genotypes are shown. Non-normalized basisphenoid and presphenoid bone lengths are diminished in Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ mice as compared to Alplfl/fl mice. After normalization for total skull size, the basioccipital bone length is increased while basisphenoid and presphenoid bone lengths are decreased in Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ mice as compared to Alplfl/fl mice. Yellow scale bars = 200 µm. **p< 0.01 vs Alplfl/fl . Red = Alplfl/fl , Blue = Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+. n=20 per genotype.

Figure 2.

Cranial neural crest cell-specific deletion of Alpl leads to cranial base defects. (A) Nano-CT sagittal slice images of representative 35 day-old Alplfl/fl and Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ skulls are shown. The dotted box and its magnified image show the cranial base. SOS = spheno-occipital synchondrosis; ISS = intersphenoid synchondrosis. Skulls of Alplfl/fl, P0-Cre+ mice showed partial to complete fusion of the ISS, which was not seen in any Alplfl/fl mice. The SOS appeared normal in all mice regardless of genotype. (B) Nano-CT based measurements of cranial base bone lengths, and the lengths as normalized by total skull length to account for skull size differences, between genotypes are shown. Non-normalized basisphenoid and presphenoid bone lengths are diminished in Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ mice as compared to Alplfl/fl mice. After normalization for total skull size, the basioccipital bone length is increased while basisphenoid and presphenoid bone lengths are decreased in Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ mice as compared to Alplfl/fl mice. Yellow scale bars = 200 µm. **p< 0.01 vs Alplfl/fl . Red = Alplfl/fl , Blue = Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+. n=20 per genotype.

Figure 3.

Cranial neural crest cell-targeted Alpl ablation leads to hypertrophic zone expansion in the intersphenoidal synchondrosis at postnatal day 5. (A) Alkaline phosphatase staining of the intersphenoid synchondrosis (ISS) and spheno-occipital synchondrosis (SOS) demonstrates lack of TNAP enzyme activity in and around the ISS but not the SOS of Alplfl/flfl; P0-Cre+ mice, indicative of cranial neural crest derived specific TNAP ablation. (B) Alcian blue staining of the ISS of Alplfl/fl and Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ mice. More alcian blue staining is evident in ISS of Alplfl/flfl; P0-Cre+ compared to Alplfl/fl mice indicative of greater width of the hypertrophic zone, but not when normalized by cell number indicative of similar staining per cell. (C) Hematoxylin and Eosin staining showing the histology of the ISS with/without ablation of TNAP in cranial neural crest derived cells is shown. The total area of the ISS is greater in Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ as compared to Alplfl/fl mice. Hypertrophic zone widths are significantly greater in Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ as compared to Alplfl/fl mice, even after normalization to total ISS width (ratio). All other zones are significantly decreased after zone width normalization to total ISS width in Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ as compared to Alplfl/fl mice. N=6 per genotype. Black scale bars = 200 µm. **p< 0.01, ***p<.005 between genotypes . Red = Alplfl/fl , Blue = Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+. Zones were demarkated according to the following criteria. RZ: The nucleus is round. PZ: The nucleus is flat. PHZ: Adjacent to the PZ, and the cell shape is flattened and enlarged. HZ: The shape is greatly enlarged.

Figure 3.

Cranial neural crest cell-targeted Alpl ablation leads to hypertrophic zone expansion in the intersphenoidal synchondrosis at postnatal day 5. (A) Alkaline phosphatase staining of the intersphenoid synchondrosis (ISS) and spheno-occipital synchondrosis (SOS) demonstrates lack of TNAP enzyme activity in and around the ISS but not the SOS of Alplfl/flfl; P0-Cre+ mice, indicative of cranial neural crest derived specific TNAP ablation. (B) Alcian blue staining of the ISS of Alplfl/fl and Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ mice. More alcian blue staining is evident in ISS of Alplfl/flfl; P0-Cre+ compared to Alplfl/fl mice indicative of greater width of the hypertrophic zone, but not when normalized by cell number indicative of similar staining per cell. (C) Hematoxylin and Eosin staining showing the histology of the ISS with/without ablation of TNAP in cranial neural crest derived cells is shown. The total area of the ISS is greater in Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ as compared to Alplfl/fl mice. Hypertrophic zone widths are significantly greater in Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ as compared to Alplfl/fl mice, even after normalization to total ISS width (ratio). All other zones are significantly decreased after zone width normalization to total ISS width in Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+ as compared to Alplfl/fl mice. N=6 per genotype. Black scale bars = 200 µm. **p< 0.01, ***p<.005 between genotypes . Red = Alplfl/fl , Blue = Alplfl/fl; P0-Cre+. Zones were demarkated according to the following criteria. RZ: The nucleus is round. PZ: The nucleus is flat. PHZ: Adjacent to the PZ, and the cell shape is flattened and enlarged. HZ: The shape is greatly enlarged.

Figure 4.

Cranial neural crest cell-targeted Alpl ablation leads to increased proliferation, and diminished apoptosis in the ISS at postnatal day 5. (A) Cells were immunostained for Ki67 (red) as a marker of proliferating cells and costained with nuclear dapi stain (blue). Merged stains are shown. Ki67+ cells relative to the total number of cells per chondrocyte zone were quantified and . (B) Cells were immunostained with TUNEL (green) to detect apoptotic DNA breaks and costained with nuclear dapi stain (blue). Merged and TUNEL only stains are shown. TUNEL+ cells relative to the total area of the anterior and posterior hypertrophic zones (HZ) were quantified (HZ outlined in yellow, yellow arrows point to TUNEL+ cells). N=6 per genotype. **p<.01, ***p<.005 between genotypes. Red = Alplfl/fl , Blue = Alplfl/fl: P0-Cre+.

Figure 4.

Cranial neural crest cell-targeted Alpl ablation leads to increased proliferation, and diminished apoptosis in the ISS at postnatal day 5. (A) Cells were immunostained for Ki67 (red) as a marker of proliferating cells and costained with nuclear dapi stain (blue). Merged stains are shown. Ki67+ cells relative to the total number of cells per chondrocyte zone were quantified and . (B) Cells were immunostained with TUNEL (green) to detect apoptotic DNA breaks and costained with nuclear dapi stain (blue). Merged and TUNEL only stains are shown. TUNEL+ cells relative to the total area of the anterior and posterior hypertrophic zones (HZ) were quantified (HZ outlined in yellow, yellow arrows point to TUNEL+ cells). N=6 per genotype. **p<.01, ***p<.005 between genotypes. Red = Alplfl/fl , Blue = Alplfl/fl: P0-Cre+.

Figure 5.

Cranial neural crest cell-targeted Alpl deletion alters expression of PTHrP, IHH, Sox9 and ColX in the ISS at postnatal day 5. (A) Cells were immunostained for PTHrp (red) and costained with nuclear dapi stain (blue), then quantified by cell count as normalized to total cell number per chondrocyte zone. (B) Cells were immunostained for PTHrp (red) and costained with nuclear dapi stain (blue), then quantified by cell count as normalized to total cell number per chondrocyte zone. (C) Cells were immunostained for Sox9 (red) and costained with nuclear dapi stain (blue), then quantified by cell count as normalized to total cell number per chondrocyte zone. (D) Cells were immunostained for ColX (red) and costained with nuclear dapi stain (blue), then quantified by cell count as normalized to total cell number per chondrocyte zone. n=6 per genotype. Yellow scale bars = 200 µm. *p<.05, **p< 0.01 between genotypes . Red = Alplfl/fl, Blue = Alplfl/fl: P0-Cre+mice.

Figure 5.

Cranial neural crest cell-targeted Alpl deletion alters expression of PTHrP, IHH, Sox9 and ColX in the ISS at postnatal day 5. (A) Cells were immunostained for PTHrp (red) and costained with nuclear dapi stain (blue), then quantified by cell count as normalized to total cell number per chondrocyte zone. (B) Cells were immunostained for PTHrp (red) and costained with nuclear dapi stain (blue), then quantified by cell count as normalized to total cell number per chondrocyte zone. (C) Cells were immunostained for Sox9 (red) and costained with nuclear dapi stain (blue), then quantified by cell count as normalized to total cell number per chondrocyte zone. (D) Cells were immunostained for ColX (red) and costained with nuclear dapi stain (blue), then quantified by cell count as normalized to total cell number per chondrocyte zone. n=6 per genotype. Yellow scale bars = 200 µm. *p<.05, **p< 0.01 between genotypes . Red = Alplfl/fl, Blue = Alplfl/fl: P0-Cre+mice.

Figure 6.

Inorganic phosphate (Pi) and inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) differentially alter cranial base signaling and differentiation in culture. Cranial base was dissected from newborn wild type mice and cultured in Pi free media that was supplemented with/without Pi or PPi as indicated. Only the posterior HZ was measured because no bone mineralization was apparent on the anterior aspect of the ISS at birth. Moreover, the RZ and PZ could not be distinguished. Thus, we measured the zone of PZ+RZ and the posterior HZ. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and (B) alkaline phosphatase (AP) stains of cranial base sections after 5 days of culture with/without (Pi) or (PPi). Stains were quantified by counting immune-positive cells as divided by the total number of cells. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and (B) alkaline phosphatase (AP) stains of cranial base sections after 5 days of culture with/without (Pi) or (PPi). Quantification of growth plate zones demonstrates that culture with Pi or PPi increases overall width of the ISS, culture with Pi increases width of the resting (RZ) and proliferating zones (PZ), and culture with PPi increases width of the hypertrophic zone (HZ). There were no significant differences in AP (alkaline phosphatase) activity between treatment groups. (C) PPi and not PPi increases IHH signaling (red) in cultured ISS. (D) PPi and, to a lesser extent, Pi increase PTHrp signaling (red) in cultured ISS. (E) Pi increases while PPi decreases ColX expression (red) in cultured ISS. (F) Pi increases while PPi decreases Sox9 expression (red) in cultured ISS. treatment groups. (G) PPi decreases apoptosis as indicated by TUNEL staining (green) for DNA breaks. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p<.005, ****p<.001 between indicated treatment groups.

Figure 6.

Inorganic phosphate (Pi) and inorganic pyrophosphate (PPi) differentially alter cranial base signaling and differentiation in culture. Cranial base was dissected from newborn wild type mice and cultured in Pi free media that was supplemented with/without Pi or PPi as indicated. Only the posterior HZ was measured because no bone mineralization was apparent on the anterior aspect of the ISS at birth. Moreover, the RZ and PZ could not be distinguished. Thus, we measured the zone of PZ+RZ and the posterior HZ. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and (B) alkaline phosphatase (AP) stains of cranial base sections after 5 days of culture with/without (Pi) or (PPi). Stains were quantified by counting immune-positive cells as divided by the total number of cells. (A) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining and (B) alkaline phosphatase (AP) stains of cranial base sections after 5 days of culture with/without (Pi) or (PPi). Quantification of growth plate zones demonstrates that culture with Pi or PPi increases overall width of the ISS, culture with Pi increases width of the resting (RZ) and proliferating zones (PZ), and culture with PPi increases width of the hypertrophic zone (HZ). There were no significant differences in AP (alkaline phosphatase) activity between treatment groups. (C) PPi and not PPi increases IHH signaling (red) in cultured ISS. (D) PPi and, to a lesser extent, Pi increase PTHrp signaling (red) in cultured ISS. (E) Pi increases while PPi decreases ColX expression (red) in cultured ISS. (F) Pi increases while PPi decreases Sox9 expression (red) in cultured ISS. treatment groups. (G) PPi decreases apoptosis as indicated by TUNEL staining (green) for DNA breaks. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p<.005, ****p<.001 between indicated treatment groups.

Figure 7.

TNAP deficient O9-1 neural crest cells exhibit diminished proteoglycan accumulation plus aberrant expression of neural crest and stem cell markers. Cells were transduced with TNAP specific Alpl shRNA (shAlpl) or control nontarget shRNA. TNAP enzyme activity was visualized by incubation of cells with a colorimetric substate and quantified by densitometry. mRNA levels were quantified by real time PCR and are presented as normalized to GAPDH. (A) TNAP activity and TNAP mRNA levels are significantly reduced in shAlpl O9-1 cells as compared to the control cells. (B) Cells were cultured under chondrocyte differentiation conditions for 7 days, stained with Alcian blue then quantified by densitometry. Alcian blue staining for proteoglycan accumulation was significantly diminished in shAlpl O9-1 cells as compared to the control cells. (C) Expression of Sox9 was diminished in TNAP deficient as compared to control cells, while other markers of neural crest were not different between genotype. Expression of Nestin was decreased while expression of CD44 and Sca1 were increased in TNAP deficient as compared to control cells. Red = non-target O9-1 cells, Blue = shAlpl O9-1 cells. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01 between genotype.

Figure 7.

TNAP deficient O9-1 neural crest cells exhibit diminished proteoglycan accumulation plus aberrant expression of neural crest and stem cell markers. Cells were transduced with TNAP specific Alpl shRNA (shAlpl) or control nontarget shRNA. TNAP enzyme activity was visualized by incubation of cells with a colorimetric substate and quantified by densitometry. mRNA levels were quantified by real time PCR and are presented as normalized to GAPDH. (A) TNAP activity and TNAP mRNA levels are significantly reduced in shAlpl O9-1 cells as compared to the control cells. (B) Cells were cultured under chondrocyte differentiation conditions for 7 days, stained with Alcian blue then quantified by densitometry. Alcian blue staining for proteoglycan accumulation was significantly diminished in shAlpl O9-1 cells as compared to the control cells. (C) Expression of Sox9 was diminished in TNAP deficient as compared to control cells, while other markers of neural crest were not different between genotype. Expression of Nestin was decreased while expression of CD44 and Sca1 were increased in TNAP deficient as compared to control cells. Red = non-target O9-1 cells, Blue = shAlpl O9-1 cells. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01 between genotype.

Table 1.

Primary Antibodies.

Table 1.

Primary Antibodies.

| Antibody |

Company |

Cat. # |

Type |

Anti-retrieval |

Dilution |

| Ki67 |

Abcam |

ab16667 |

Rabbit

Monoclonal |

0.5% Trypsin

37℃ 20min |

200 |

| PTHrP |

Invitrogen

(Thermo Fisher Scientific) |

PA5-102455 |

Rabbit

Polyclonal |

No |

500 |

| IHH |

Abcam |

ab39634 |

Rabbit

Polyclonal |

No |

100 |

| Col 2 |

Abcam |

ab34712 |

Rabbit

Polyclonal |

pH6.0

5.5mM Citric Acid

90℃ 20min, RT 20min |

100 |

| Col X |

Cosmo Bio USA |

LSL-LB-0092 |

Rabbit

Polyclonal |

No |

100 |

| Sox9 |

Abcam |

ab185966 |

Rabbit

Monoclonal |

No |

500 |