1. Introduction

Endodontics encompass a wide range of approaches which aim at diagnosing, preventing, and treating pulpal and periapical diseases and endodontic infections [

1], including root canal treatment, one of the most performed dental procedures worldwide [

2,

3]. It involves filling the endodontic space with a sterile root filling material, gutta percha. However, since this filling material is bioinert, root canal treatments often result in the loss of the tooth's immune defense, vascularization, and regenerative potential.

To address this limitation, researchers began exploring regenerative endodontic procedures (REPs) as early as in the 1960s to restore pulpal vitality. This led to the emergence of "revascularization" procedures in the 2000s, which are based on the concept of using patient-derived bioactive materials in a context of cell-homing, within the cleaned endodontic space [

4,

5,

6]. REPs are clinical strategies that aim at recreating dental pulp tissue using strategies such as tissue engineering. REPs are based on the replacement of the inflamed dental pulp by a temporary dental pulp substitute based on hydrogels composed of biomacromolecules, potentially associated with cells, and called here endodontic substitutes. The context of the endodontic root is one of the highest challenges for REPs due to its size and anatomical complexity [

7]. Numerous clinical and physicochemical parameters, such as apex size and endodontic shape, were reported to influence the outcome of REPs and results vary greatly between patients [

8,

9,

10]. Recent research in the field of dental materials and endodontics had increasingly focused its attention in developing innovative bioactive materials that can improve molecules’ release and promote tissue repair and regeneration [

11,

12,

13]. Bioactivity, which can be defined as the biological activity of a device or drug, is mostly linked to the nature of the biomolecules and chemical compounds incorporated, that can be released in the surrounding tissue [

14]. Most of the endodontic substitutes that were studied for REP incorporated bioactive compounds such as antibiotics, peptides, or nanoparticles into their hydrogel, thus making them bioactive endodontic hydrogels [

13,

15,

16]

However, one of the major scientific and clinic lock for REP strategies is the lack of knowledge regarding the various parameters that could influence the release of bioactive compounds, especially because of the number of parameters that needs to be considered to predict and control such mechanisms [

17,

18]. This point is problematic because it will complicate the clinical validation and hinder the transition from bench to bedside. In this article, we reviewed most of the parameters that are or could be identified, individualized, and studied in a close future. The clear identification of these biophysical parameters will allow their mathematical modeling to generate in silico tools to predicts the bioactivity and its potential release.

This article proposes, first, to review and define what could be considered as bioactive endodontic hydrogels, and then identify and discuss some parameters already investigated in the literature that could influence this bioactivity. Finally, the last part emulates some challenges and perspectives regarding the future of this field of research.

2. Bioactive endodontic hydrogel

The bioactivity of a biomaterial refers to its ability to interact with biological systems such as living tissues. A variety of bioactive materials were already designed and proposed to improve interactions between cells and tissues, triggering processes such as cell adhesion, proliferation, differentiation, and promoting tissue regeneration [

19,

20]. Surface properties and chemical composition of these materials play a crucial role in facilitating biocellular interactions, allowing the materials to merge with the surrounding biological environment. Bioactive endodontic hydrogels could be considered as advanced and innovative materials for REP that were specifically designed to promote and enhance dental pulp regeneration.

Many endodontic hydrogels were already suggested for REP and reported in the literature, mostly in injectable forms [

21,

22,

23]. The main components of bioactive endodontic hydrogels include a matrix, one or more bioactive agents, and a cross-linking mechanism. A hydrogel matrix provides a three-dimensional scaffold that can mimic the natural extracellular matrix, offering support for cell adhesion and tissue ingrowth. Several polymers, such as chitosan, gelatin, or hyaluronic acid, were also commonly reported to allow the biological properties of the hydrogel matrix [

24,

25,

26]. The cross-linking mechanism is also a key parameter to consider and can be achieved through physical or chemical methods [

27,

28].

The use of bioactive endodontic hydrogels in root canal therapy offers several advantages over conventional inert materials. Firstly, bio-inspired hydrogels, such as fibrin-based hydrogels, where one of the endodontic hydrogels that was able to promote regenerative process characterized by the formation of a dentin-pulp-like complex [

29]. Secondly, the bioactive agents incorporated in the hydrogel are easily released to create a favorable microenvironment for tissue regeneration. Bioactive agents could be biomolecules such as growth factors, that stimulate tissue repair and regeneration. Growth factors, such as transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), were already reported to stimulate cell proliferation and differentiation, angiogenesis, and tissue regeneration of the dental pulp when incorporated in hydrogels [

30,

31,

32,

33]. Additionally, bioactive endodontic hydrogels may include antimicrobial agents, such as chlorhexidine or silver nanoparticles, to avoid bacterial infection and reduce the risk of treatment failure [

21,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]. Furthermore, bioactive endodontic hydrogels can be clinically administered using minimally invasive techniques, such as syringe injection, allowing for precise placement within the endodontic space. This minimizes the risk of per operative complications and promotes the preservation of the remaining tooth structure.

In conclusion, endodontic hydrogels, notably those based on bio-inspired molecules such as fibrin or chitosan, are promising candidates to improve the success of REPs. The most challenging point with these devices is to control the spatio-temporal bioactivity to create a specific microenvironment that ensures prolonged effects to enhance REPs chances of success. However, this controlled bioactivity is nowadays overlooked or simplified in the context of endodontic hydrogel, suggesting the need to deeply investigate this multifactorial problem.

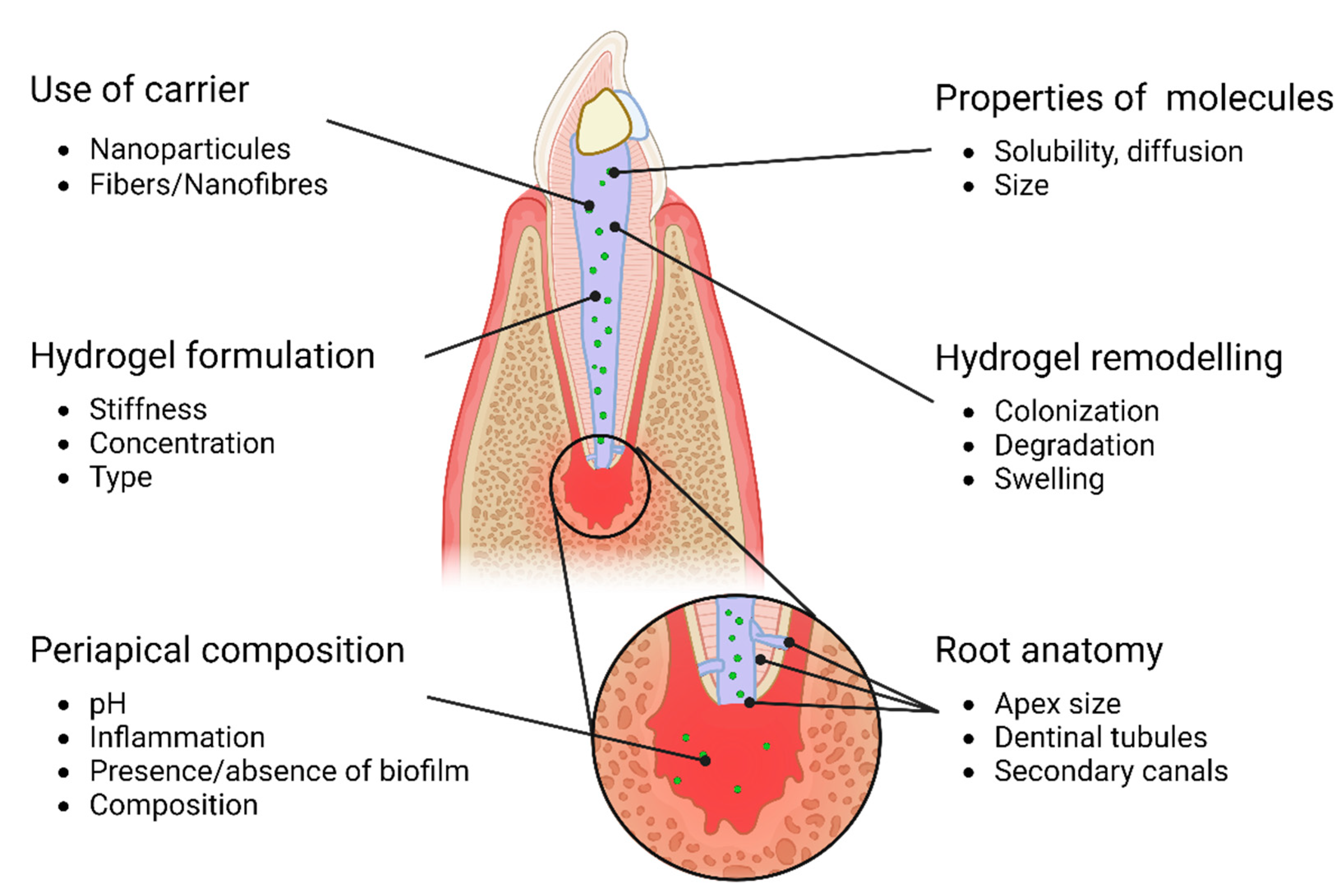

3. Bioactive endodontic hydrogel: a multifactorial problem (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

Overview of parameters that could influence bioactivity of endodontic hydrogels.

Figure 1.

Overview of parameters that could influence bioactivity of endodontic hydrogels.

3.1. Properties of hydrogels

The physical and chemical properties of any endodontic substitute used for REP should have controlled biochemical properties (release, swelling…) to achieve proper dental pulp regeneration. Several parameters such as porosity, mechanical strength, or biocompatibility of the hydrogel could strongly promote or reduce it [

40,

41]. Moreover, cell adhesion and proliferation were also reported to influence the release kinetics of various molecules, by contracting the hydrogel and synthesizing a new extracellular matrix that also affects cell-biomaterial relationship [

40,

42,

43,

44]. This is illustrated by the work of Jeon

et al. (2006) which reports that the lower the fibrin concentration, the greater the release of FGF2, a growth factor correlated with cell adhesion [

45]. Changes of the endodontic environment can be explained by numerous characteristics, such as the ability of the hydrogel to contract and modulate its shape, its degradation over the time, the efficiency of molecules entrapping and release, or swelling and volume variations in contact with fluids [

46,

47,

48,

49,

50]. In summary, many biological, physical and chemical properties can influence the hydrogel’s behavior and the bioavailability of supplemented bioactive compounds.

3.2. Properties of the biomolecular building block

Hydrogels are formed by the 3D organization of biomolecular building blocks, that will organize into fibers, in combination with biomolecules, entrapped between the fibers.

The added biomolecules play a major role during the release from the endodontic space to the peri-apical environment. Parameters of the released biomolecules such as size, shape, charge, and solubility in hydrophilic or hydrophobic media, play a critical role in their bioactivity and bioavailability, as they modify its ability to diffuse through, and interact with the hydrogel and the surrounding host tissue [

51,

52]. Current hydrogels developed for endodontic treatment include most of the time, molecules such as growth factors, antibiotics, and anti-inflammatory agents [

53,

54,

55,

56]. Several studies point out the importance of physicochemical studies focusing on detailing diffusion kinetics inside hydrogels and gels from a mathematic point of view [

40,

48,

57]. In summary, the physicochemical properties of the molecule in combination with a specific hydrogel will strongly affect reciprocal interactions and influence greatly the release kinetics and therefore the bioactivity of endodontic hydrogels.

3.3. Periapical composition (cells/medium/pH,inflamation)

The composition of the periapical host tissues can also influence the release of molecules from an endodontic material (hydrogel). Each molecule, according to its own physicochemical properties, will have varying affinities depending on the tissue, hydrogel, pH… [

48,

52]. Labille

et al. (2007) explored the way Brownian movement (the random movement of molecules in a solution) is modified in a gel/solution interface, and how the interface itself influences the gel’s behavior and porosity. Leddy

et al. (2004) described how hydrogels surface in contact with organic structures and liquids would swell and degrade at various rate according to the properties of both scaffold and environment [

17,

46,

47,

58]. The inflammatory response, in the periapical areas, was also reported to potentially influence the local pH and therefore the ionization state of reactive groups, thus modifying the solubility, and in turn, the release kinetics of molecules from the endodontic material [

59]. In summary, endodontic hydrogels are not isolated, and their interactions with surrounding host tissues and liquids will strongly influence their rheological, chemical, and bioactive properties.

3.4. Hydrogel degradation and remodeling

The degradation of the hydrogel also needs to be considered in the release kinetic of the bioactive molecules over time. For example, some hydrogels such as fibrin, GelMa or agarose have been used as an endodontic material for their ability to be degraded, inducing the gradual release of bioactive molecules over time [

47,

60,

61]. The degradation rate of the material can be adjusted, especially by modulating hydrogel concentration and cross-linking, to achieve the desired release profile. Other work, on different matrixes also used fine tuning of gelatin hydrogels to control degradation rate and thus, release [

53,

58,

62]. However, in the case of fibrin hydrogels, cell colonization will lead to matrix contraction, and although the fibrin matrix might be degraded, the production of a new matrix by cells leads, according to Leddy

et al. and Lepsky

et al., to a decrease of molecule release [

42,

46,

63].

3.5. Root anatomy and composition

The periapical diameter of the tooth is one of the main parameters to be considered as it could greatly vary in size, shape, and direction according to the patient and influence the release properties accordingly [

64,

65]. Physics and Fick’s law of diffusion supposes a linear impact of the contact surface and concentration gradient on diffusion rates and amounts. The apical diameter determines the contact surface between endodontic hydrogel and host periapical tissues. As a result, the increase of the apical diameter should lead to increase the diffusion of the hydrogel components in the host periapical tissues. Fick’s law was validated in previous studies of Abbott

et al. and Robert

et al. [

55,

66], but subtle variations in shape and direction of the endodontic space are still to be taken into consideration. Moreover, it is well known that bioactivity of endodontic hydrogel will not only rely on the periapical region, but also in the diffusion of molecules across the porous surface of dentine around the root [

67]. The other way round release of molecules from dentine trough the hydrogel is also a key point to considered. Indeed, dentin-derived growth factors were reported to be sufficient to promote the recruitment and differentiation of stem/stromal cells [

65,

68,

69]. As a result, the overall diffusion through the hydrogel is a sum of bi-directional mechanisms of release of hydrogel-derived molecules from the hydrogel to the dentin and of the release of dentin-derived biomolecules from the dentin to the hydrogel. The patient-specific shape of the endodontic space plays a crucial role in these mechanisms of release by varying the dentin-hydrogel contact surface. These points strongly complexify the modelling of hydrogels release and suggests the need to integrate these anatomic parameters to personalize the REP treatment.

3.6. Use of carriers

Carriers or vectors can be used to deliver the therapeutic molecules to the site of interest, in a controlled manner [

35,

38]. These carriers can be incorporated into the material structure or added separately as a coating or filler. Jeon

et al. (2006) encapsulated bFGF on polymeric nanoparticles to achieve a controlled and sustained release over weeks and to limit the burst effect frequently observed from fibrin hydrogels [

45]. Bekhouche

et al. (2020) loaded clindamycin on PLGA nanoparticles to achieve sustained release and maintain the antibacterial action within a fibrin hydrogel [

70]. By modifying the vector’s properties (ionic charge, hydrophilicity…), it is also possible to deeply modify the release kinetics from a material and to achieve a fine-tuned bioactivity. Vectors could be cell- or space-specific using surface targeting, or achieve on demand release in “smart” devices [

40,

71,

72].

4. Bioactive endodontic hydrogels: challenges and perspectives

4.1. Deep characterization of biochemical characteristics of the endodontic players

Bioactivity can be defined as the biological activity of a device or drug. Fibrin hydrogels are an example of potential endodontic hydrogels, that harbor several bioactivities [

60,

70,

73,

74,

75]. Hydrogel macromolecular properties such as stiffness, fiber and pore sizes, reactive groups were reported to impact the bioactivity [

56,

76]. One can easily imagine the immense amount of data and knowledge necessary to achieve the deep understanding of the bioactive properties of a hydrogel, especially in combination with active molecules such as growth factors or antibiotics. This use of antibiotic components remains however controversial due to potential bacterial resistances and lack of knowledge surrounding exact root canal delivery and apical diffusion to the periodontal host tissues, leads to such components being avoided in the most recent guidelines on regenerative procedures [

77]. Controlled delivery with a vector, such as a nanoparticle for example, adds a great number of parameters such as size, solubility, or shape, that complexify even further the release, and therefore the bioactivity of the loaded bioactive molecule. Although the physicochemical characteristics of biomolecules are often well documented in the literature, they need to be taken into consideration in the specific context of encapsulation in a hydrogel, as well as for the patient-specific morphology of the endodontic space to control the in situ and released bioactivities. Encapsulating an active molecule in a hydrogel makes the hydrogel a

de facto vector, and release of an active molecule in a specific kinetic, makes them not only scaffolds, but also galenic objects.

Galenic could be defined as the science of a medication’s shape and vector, that could be optimized according to the molecule vectorized, as well as the patient’s context and needs. In order to safely go from bench to bedside, hydrogels in endodontics must be explored as galenic objects, as well as scaffolds, and it would be interesting to add more galenistic researches and scale up investigations to explore the bioactivity of these devices.

4.2. Create and validate standardizable models

The study of the endodontic hydrogel bioactivity will require, in the future, simple, cheap and reproducible models to study all the previously listed parameters and improve knowledge. From a methodological point of view, the release of molecules from the apex was studied for decades with ‘

ex vivo’ models,

in vitro models such as pipettes hung in syringes, and

in vivo models such as roots implanted in mice backs [

18,

66,

67]. However, the 'ex vivo' model using human teeth is challenging due to the difficulty, or even impossibility, of obtaining human tissues. Moreover, it involves labor-intensive and time-consuming manual preparation of each endodontic space, and the interindividual variability in root and canal anatomy can lead to heterogeneous results and masks the effect of each parameter. To overcome these limitations, an alternative model was proposed using a pipette system hung in a syringe filled with agarose to simulate the apical environment and studying the release of Ca(OH)2. Although this new model eliminated the need for human tissues, it still required significant preparation time for each individual pipette [

66]. Finally, a root model implanted in a mouse was used to explore the release of radio-traced molecules and gain a deeper understanding of the systemic consequences of endodontic materials releasing molecules in the whole organism. This model is interesting but also presented several limits, as they are heavy experiments for the animals and come with a financial toll. This explains why most of the release kinetics of endodontic hydrogels are investigated with partial models, such as covering a hydrogel disk of PBS in a well or a becher. This approach provides a relatively large surface area, sometimes exceeding 1 cm², which is unrealistic for assessing apical release and can lead to an overestimation of potential clinical effects. This observation is supported by study results showing a maximum of 35% release after 24 hours from fibrin in an endodontic model, while Lepsky et al. (2021) reported up to 90% release at the same time point, with a partial model. This overestimates dramatically the potential bioactivity of any endodontic hydrogel [

61,

78,

79,

80]. To address this issue and achieve a more standardized approach for investigating apical release, a simple and efficient model can be suggested.

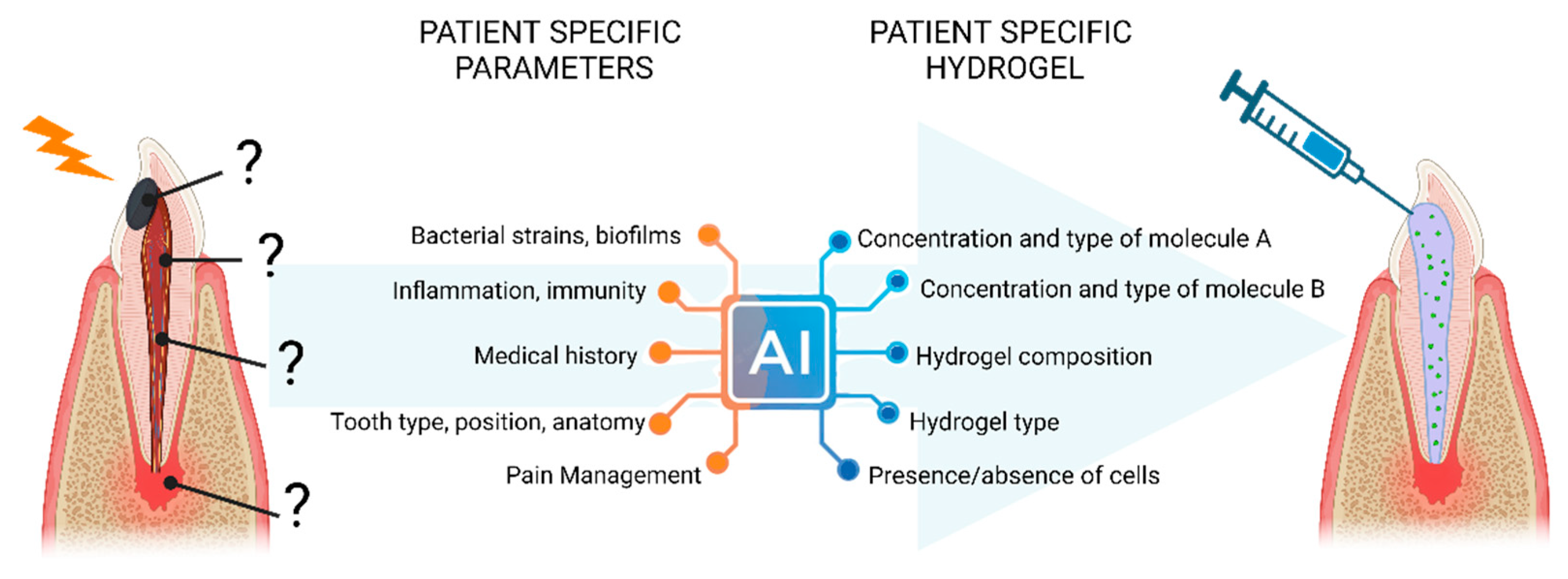

4.3. Emulate mathematical model for understanding and personalize endodontic hydrogels (Figure 2)

Figure 2.

Perspectives of personalized endodontic hydrogel using AI models to design the most adapted device according to patient specific parameters.

Figure 2.

Perspectives of personalized endodontic hydrogel using AI models to design the most adapted device according to patient specific parameters.

Descriptive mathematical models, also called fitting models, such as Peppas Krosmeyer or First Order Kinetic model are already used to investigate the release from an endodontic biomaterial [

61]. Dubey

et al used a model to fit and describe the release of antibiotics from a GelMa endodontic hydrogel and concluded on the gel’s release kinetic being a mix of Fickian diffusion and swelling-triggered diffusion in PBS [

61]. Peppas, as well as other curve fitting models are powerful tools for describing the diffusion from a hydrogel and contribute greatly to a better understanding of bioactive materials behavior [

61,

81,

82].

In the past decade, there has been a remarkable surge in the generation of experimental and clinical data in biology and dental medicine. However, due to the wide diversity of models used, it has become challenging to compare and extrapolate findings. The future advancements in Artificial Intelligence and 3D imaging of endodontic spaces hold the potential to address this issue by designing virtual models based on scientific databases, such as those produced by omics for high throughput screening and predicting pathological biomarkers [

83,

84]. Similarly, such approaches could be efficiently used to anticipate the bioactivity of these hydrogels based on galenic properties of endodontic hydrogels [

81,

82]. In the future, this would lead to an even more personalized medicine, tailored to each patient’s needs and biological parameters, such as age, inflammation, bacterial load and strains, root anatomy or medical history [

85].

5. Conclusions

Anticipating the bioactivity of a hydrogel in and around the periapical area is complex, mostly due to the numerous parameters that could influence the release of molecules. Understanding these properties can help guide the development of endodontic hydrogels that can effectively release therapeutic molecules and drive a more personalized bioactivity.

Further studies appear required to: 1) improve knowledge of the release of molecules and endodontic hydrogels, 2) create and validate standardizable model to investigate the parameters influencing the release, 3) emulate mathematical model that could predict hydrogels behavior in clinic.

Author Contributions

Leveque M: Design of the figures, Writing. Bekhouche M: Writing – review & edit. Aussel A: Writing – review & edit, Kadiatou S: Writing – review & edit. Farges J-C: Writing – review & edit. Richert R : Writing – review & edit. Ducret M: Conceptualization, Writing – review & edit.

Funding

This work was supported by the French National Association of Research (ANR JCJC ENDONANOBIOTIC (ANR-21-CE19-0001) and ANR JCJC TRIDENTOMIC (ANR-21 CE44-0015)), the Fondation de l’Avenir (AP-RM-21-030), the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) and the French Institute for Odontological Research (IFRO). ML is a recipient of a PhD grant from the French National Association of Research (ANR JCJC ENDONANOBIOTIC).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- American Association of Endodontists Root Canal Explained. Available online: https://www.aae.org/patients/root-canal-treatment/what-is-a-root-canal/root-canal-explained/ (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- American Association of Endodontists Guide to Clinical Endodontics.

- CRDIS Community Research and Developpement Information Services (2019) ‘ Increasing the Success Rate of Root Canal Treatement.

- Ostby, B.N. The Role of the Blood Clot in Endodontic Therapy. An Experimental Histologic Study. Acta Odontol Scand 1961, 19, 324–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwaya, S.; Ikawa, M.; Kubota, M. Revascularization of an Immature Permanent Tooth with Apical Periodontitis and Sinus Tract. Dental Traumatology 2001, 17, 185–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Yelick, P.C. Vital Pulp Therapy—Current Progress of Dental Pulp Regeneration and Revascularization. Int J Dent 2010, 2010, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raddall, G.; Mello, I.; Leung, B.M. Biomaterials and Scaffold Design Strategies for Regenerative Endodontic Therapy. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2019, 7, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Widbiller, M.; Knüttel, H.; Meschi, N.; Durán-Sindreu Terol, F. Effectiveness of Endodontic Tissue Engineering in Treatment of Apical Periodontitis: A Systematic Review. Int Endod J 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fouad, A.F.; Diogenes, A.R.; Torabinejad, M.; Hargreaves, K.M. Microbiome Changes during Regenerative Endodontic Treatment Using Different Methods of Disinfection. J Endod 2022, 48, 1273–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Lyu, P.; Bi, R.; Chen, X.; Yu, Y.; Li, Z.; Fan, Y. Neural Regeneration in Regenerative Endodontic Treatment: An Overview and Current Trends. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, 15492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvell, B.W.; Smith, A.J. Inert to Bioactive – A Multidimensional Spectrum. Dental Materials 2022, 38, 2–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferracane, J.L.; Sidhu, S.K.; Melo, M.A.S.; Yeo, I.-S.L.; Diogenes, A.; Darvell, B.W. Bioactive Dental Materials. JADA Foundational Science 2023, 2, 100022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveque, M.; Guittat, M.; Thivichon-Prince, B.; Reuzeau, A.; Eveillard, M.; Faure, M.; Farges, J.; Richert, R.; Bekhouche, M.; Ducret, M. Next Generation Antibacterial Strategies for Regenerative Endodontic Procedures: A Scoping Review. Int Endod J 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal-Fabbro, R.; Swanson, W.B.; Capalbo, L.C.; Sasaki, H.; Bottino, M.C. Next-Generation Biomaterials for Dental Pulp Tissue Immunomodulation. Dental Materials 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddiqui, Z.; Acevedo-Jake, A.M.; Griffith, A.; Kadincesme, N.; Dabek, K.; Hindi, D.; Kim, K.K.; Kobayashi, Y.; Shimizu, E.; Kumar, V. Cells and Material-Based Strategies for Regenerative Endodontics. Bioact Mater 2022, 14, 234–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, H.F.; Kobayashi, Y.; Kearney, M.; Shimizu, E. Epigenetic Therapeutics in Dental Pulp Treatment: Hopes, Challenges and Concerns for the Development of next-Generation Biomaterials. Bioact Mater 2023, 27, 574–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, W.; Gwon, Y.; Park, S.; Kim, H.; Kim, J. Therapeutic Strategies of Three-Dimensional Stem Cell Spheroids and Organoids for Tissue Repair and Regeneration. Bioact Mater 2023, 19, 50–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aubeux, D.; Valot-Salengro, A.; Gautier, G.; Malet, A.; Pérez, F. Transforaminal and Systemic Diffusion of an Active Agent from a Zinc Oxide Eugenol-Based Endodontic Sealer Containing Hydrocortisone—in an in Vivo Model. Clin Oral Investig 2020, 24, 4395–4402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamocki, K.; Nör, J.E.; Bottino, M.C.; Cicero Bottino, M. Dental Pulp Stem Cell Responses to Novel Antibiotic-Containing Scaffolds for Regenerative Endodontics HHS Public Access.

- Keane, T.J.; Horejs, C.-M.; Stevens, M.M. Scarring vs. Functional Healing: Matrix-Based Strategies to Regulate Tissue Repair. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2018, 129, 407–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Zhou, P.; Lu, H.; Guan, Y.; Ma, M.; Wang, J.; Shang, G.; Jiang, B. Potential Apply of Hydrogel-Carried Chlorhexidine and Metronidazole in Root Canal Disinfection. Dent Mater J 2021, 40, 2020–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Kuang, R.; Liu, H.; Sun, D.; Mao, T.; Jiang, K.; Yang, X.; Watanabe, N.; Mayo, K.H.; et al. Injectable Hydrogel-Loaded Nano-Hydroxyapatite That Improves Bone Regeneration and Alveolar Ridge Promotion. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2020, 116, 111158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tond, D. Fibrin Hydrogels: From Repair to Regeneration; 2021.

- Zang, S.; Mu, R.; Chen, F.; Wei, X.; Zhu, L.; Han, B.; Yu, H.; Bi, B.; Chen, B.; Wang, Q.; et al. Injectable Chitosan/β-Glycerophosphate Hydrogels with Sustained Release of BMP-7 and Ornidazole in Periodontal Wound Healing of Class III Furcation Defects. Materials Science and Engineering: C 2019, 99, 919–928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atila, D.; Chen, C.-Y.; Lin, C.-P.; Lee, Y.-L.; Hasirci, V.; Tezcaner, A.; Lin, F.-H. In Vitro Evaluation of Injectable Tideglusib-Loaded Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogels Incorporated with Rg1-Loaded Chitosan Microspheres for Vital Pulp Regeneration. Carbohydr Polym 2022, 278, 118976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, J.S.; Münchow, E.A.; Bordini, E.A.F.; Rodrigues, N.S.; Dubey, N.; Sasaki, H.; Fenno, J.C.; Schwendeman, S.; Bottino, M.C. Engineering of Injectable Antibiotic-Laden Fibrous Microparticles Gelatin Methacryloyl Hydrogel for Endodontic Infection Ablation. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruppuso, M.; Iorio, F.; Turco, G.; Marsich, E.; Porrelli, D. Hyaluronic Acid/Lactose-Modified Chitosan Electrospun Wound Dressings – Crosslinking and Stability Criticalities. Carbohydr Polym 2022, 288, 119375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwon, Y.-S.; Kim, H.-J.; Hwang, Y.-C.; Rosa, V.; Yu, M.-K.; Min, K.-S. Effects of Epigallocatechin Gallate, an Antibacterial Cross-Linking Agent, on Proliferation and Differentiation of Human Dental Pulp Cells Cultured in Collagen Scaffolds. J Endod 2017, 43, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galler, K.M. Clinical Procedures for Revitalization: Current Knowledge and Considerations. Int Endod J 2016, 49, 926–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, L.N.; Puppin-Rontani, R.M.; Pascon, F.M. Effect of Intracanal Medicaments and Irrigants on the Release of Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1 and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor from Cervical Root Dentin. J Endod 2020, 46, 1616–1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ozekp, M.; Ishii, T.; Hirano, Y.; Tabata, Y. Controlled Release of Hepatocyte Growth Factor from Gelatin Hydrogels Based on Hydrogel Degradation. J Drug Target 2001, 9, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakkiettiwong, N.; Hengtrakool, C.; Thammasitboon, K.; Kedjarune-Leggat, U. Effect of Novel Chitosan-Fluoroaluminosilicate Glass Ionomer Cement with Added Transforming Growth Factor Beta-1 on Pulp Cells. J Endod 2011, 37, 367–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellamy, C.; Shrestha, S.; Torneck, C.; Kishen, A. Effects of a Bioactive Scaffold Containing a Sustained Transforming Growth Factor-Β1–Releasing Nanoparticle System on the Migration and Differentiation of Stem Cells from the Apical Papilla. J Endod 2016, 42, 1385–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pajares-Chamorro, N.; Shook, J.; Hammer, N.D.; Chatzistavrou, X. Resurrection of Antibiotics That Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Resists by Silver-Doped Bioactive Glass-Ceramic Microparticles. Acta Biomater 2019, 96, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Algazlan, A.S.; Almuraikhi, N.; Muthurangan, M.; Balto, H.; Alsalleeh, F. Silver Nanoparticles Alone or in Combination with Calcium Hydroxide Modulate the Viability, Attachment, Migration, and Osteogenic Differentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 24, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Gazlan, A.S.; Auda, S.H.; Balto, H.; Alsalleeh, F. Antibiofilm Efficacy of Silver Nanoparticles Alone or Mixed with Calcium Hydroxide as Intracanal Medicaments: An Ex-Vivo Analysis. J Endod 2022, 48, 1294–1300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, L.-J.; Lin, T.-Y.; Yao, C.-H.; Kuo, P.-Y.; Matsusaki, M.; Harroun, S.G.; Huang, C.-C.; Lai, J.-Y. Dual-Functional Gelatin-Capped Silver Nanoparticles for Antibacterial and Antiangiogenic Treatment of Bacterial Keratitis. J Colloid Interface Sci 2019, 536, 112–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Comune, M.; Rai, A.; Palma, P.; TondaTuro, C.; Ferreira, L. Antimicrobial and Pro-Angiogenic Properties of Soluble and Nanoparticle-Immobilized LL37 Peptides. Biomater Sci 2021, 9, 8153–8159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arruda, M.E.F.; Neves, M.A.S.; Diogenes, A.; Mdala, I.; Guilherme, B.P.S.; Siqueira, J.F.; Rôças, I.N. Infection Control in Teeth with Apical Periodontitis Using a Triple Antibiotic Solution or Calcium Hydroxide with Chlorhexidine: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J Endod 2018, 44, 1474–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Unagolla, J.M.; Jayasuriya, A.C. Drug Transport Mechanisms and in Vitro Release Kinetics of Vancomycin Encapsulated Chitosan-Alginate Polyelectrolyte Microparticles as a Controlled Drug Delivery System. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2018, 114, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsley, C.S.; Sung, K.; White, C.; Abecunas, C.A.; Tawil, B.J.; Wu, B.M. Functionalizing Fibrin Hydrogels with Thermally Responsive Oligonucleotide Tethers for On-Demand Delivery. Bioengineering 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lepsky, V.R.; Natan, S.; Tchaicheeyan, O.; Kolel, A.; Zussman, M.; Zilberman, M.; Lesman, A. Fitc-dextran Release from Cell-embedded Fibrin Hydrogels. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodadadi Yazdi, M.; Taghizadeh, A.; Taghizadeh, M.; Stadler, F.J.; Farokhi, M.; Mottaghitalab, F.; Zarrintaj, P.; Ramsey, J.D.; Seidi, F.; Saeb, M.R.; et al. Agarose-Based Biomaterials for Advanced Drug Delivery. Journal of Controlled Release 2020, 326, 523–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, J.; Zhao, T.; Liu, M. Fluorescence Microscopic Visualization of Functionalized Hydrogels. NPG Asia Mater 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, O.; Kang, S.-W.; Lim, H.-W.; Hyung Chung, J.; Kim, B.-S. Long-Term and Zero-Order Release of Basic Fibroblast Growth Factor from Heparin-Conjugated Poly(l-Lactide-Co-Glycolide) Nanospheres and Fibrin Gel. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 1598–1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leddy, H.A.; Awad, H.A.; Guilak, F. Molecular Diffusion in Tissue-Engineered Cartilage Constructs: Effects of Scaffold Material, Time, and Culture Conditions. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 2004, 70, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labille, J.; Fatin-Rouge, N.; Buffle, J. Local and Average Diffusion of Nanosolutes in Agarose Gel: The Effect of the Gel/Solution Interface Structure. Langmuir 2007, 23, 2083–2090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianopoulos, T.; Poh, M.-Z.; Insin, N.; Bawendi, M.G.; Fukumura, D.; Munn, L.L.; Jain, R.K. Diffusion of Particles in the Extracellular Matrix: The Effect of Repulsive Electrostatic Interactions. Biophys J 2010, 99, 1342–1349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leonidakis, K.A.; Bhattacharya, P.; Patterson, J.; Vos, B.E.; Koenderink, G.H.; Vermant, J.; Lambrechts, D.; Roeffaers, M.; Van Oosterwyck, H. Fibrin Structural and Diffusional Analysis Suggests That Fibers Are Permeable to Solute Transport. Acta Biomater 2017, 47, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, A.C.; Barker, T.H. Fibrin-Based Biomaterials: Modulation of Macroscopic Properties through Rational Design at the Molecular Level. Acta Biomater 2014, 10, 1502–1514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, J.S.; Münchow, E.A.; Bordini, E.A.F.; Rodrigues, N.S.; Dubey, N.; Sasaki, H.; Fenno, J.C.; Schwendeman, S.; Bottino, M.C. Engineering of Injectable Antibiotic-Laden Fibrous Microparticles Gelatin Methacryloyl Hydrogel for Endodontic Infection Ablation. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultanova, Z.; Kaleli, G.; Kabay, G.; Mutlu, M. Controlled Release of a Hydrophilic Drug from Coaxially Electrospun Polycaprolactone Nanofibers. Int J Pharm 2016, 505, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozekp, M.; Ishii, T.; Hirano, Y.; Tabata, Y. Controlled Release of Hepatocyte Growth Factor from Gelatin Hydrogels Based on Hydrogel Degradation. J Drug Target 2001, 9, 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanassiadis, B.; Abbott, P.; Walsh, L. The Use of Calcium Hydroxide, Antibiotics and Biocides as Antimicrobial Medicaments in Endodontics. Aust Dent J 2007, 52, S64–S82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, P.V.; Heithersay, G.S.; Hume, W.R. Release and Diffusion through Human Tooth Roots in Vitro of Corticosteroid and Tetracycline Trace Molecules from LedermixR Paste. Dental Traumatology 1988, 4, 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyatt, A.J.T.; Rajan, M.S.; Burling, K.; Ellington, M.J.; Tassoni, A.; Martin, K.R. Release of Vancomycin and Gentamicin from a Contact Lens versus a Fibrin Coating Applied to a Contact Lens. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2012, 53, 1946–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shoga, J.S.; Graham, B.T.; Wang, L.; Price, C. Direct Quantification of Solute Diffusivity in Agarose and Articular Cartilage Using Correlation Spectroscopy. Ann Biomed Eng 2017, 45, 2461–2474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guagliano, G.; Volpini, C.; Sardelli, L.; Bloise, N.; Briatico-Vangosa, F.; Cornaglia, A.I.; Dotti, S.; Villa, R.; Visai, L.; Petrini, P. Hep3Gel: A Shape-Shifting Extracellular Matrix-Based, Three-Dimensional Liver Model Adaptable to Different Culture Systems. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2023, 9, 211–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rajamäki, K.; Nordström, T.; Nurmi, K.; Åkerman, K.E.O.; Kovanen, P.T.; Öörni, K.; Eklund, K.K. Extracellular Acidosis Is a Novel Danger Signal Alerting Innate Immunity via the NLRP3 Inflammasome. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2013, 288, 13410–13419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ducret, M.; Costantini, A.; Gobert, S.; Farges, J.C.; Bekhouche, M. Fibrin-Based Scaffolds for Dental Pulp Regeneration: From Biology to Nanotherapeutics. Eur Cell Mater 2021, 41, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubey, N.; Ribeiro, J.S.; Zhang, Z.; Xu, J.; Ferreira, J.A.; Qu, L.; Mei, L.; Fenno, J.C.; Schwendeman, A.; Schwendeman, S.P.; et al. Gelatin Methacryloyl Hydrogel as an Injectable Scaffold with Multi-Therapeutic Effects to Promote Antimicrobial Disinfection and Angiogenesis for Regenerative Endodontics. J Mater Chem B 2023, 11, 3823–3835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linsley, C.S.; Sung, K.; White, C.; Abecunas, C.A.; Tawil, B.J.; Wu, B.M. Functionalizing Fibrin Hydrogels with Thermally Responsive Oligonucleotide Tethers for On-Demand Delivery. Bioengineering 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boucard, E.; Vidal, L.; Coulon, F.; Mota, C.; Hascoët, J.Y.; Halary, F. The Degradation of Gelatin/Alginate/Fibrin Hydrogels Is Cell Type Dependent and Can Be Modulated by Targeting Fibrinolysis. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estefan, B.S.; El Batouty, K.M.; Nagy, M.M.; Diogenes, A. Influence of Age and Apical Diameter on the Success of Endodontic Regeneration Procedures. J Endod 2016, 42, 1620–1625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.J.; Duncan, H.F.; Diogenes, A.; Simon, S.; Cooper, P.R. Exploiting the Bioactive Properties of the Dentin-Pulp Complex in Regenerative Endodontics. J Endod 2016, 42, 47–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, G.; Liewher, F.; Buxton, T.; McPhersoni, J. Apical Diffusion of Calcium Hydroxide in an in Vitro Model. J Endod 2005, 31, 57–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbott, P. V. Systemic Release of Corticosteroids Following Intra-Dental Use. Int Endod J 1992, 25, 189–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galler, K.M.; Widbiller, M. Perspectives for Cell-Homing Approaches to Engineer Dental Pulp. J Endod 2017, 43, S40–S45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widbiller, M.; Driesen, R.B.; Eidt, A.; Lambrichts, I.; Hiller, K.-A.; Buchalla, W.; Schmalz, G.; Galler, K.M. Cell Homing for Pulp Tissue Engineering with Endogenous Dentin Matrix Proteins. J Endod 2018, 44, 956–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bekhouche, M.; Bolon, M.; Charriaud, F.; Lamrayah, M.; Da Costa, D.; Primard, C.; Costantini, A.; Pasdeloup, M.; Gobert, S.; Mallein-Gerin, F.; et al. Development of an Antibacterial Nanocomposite Hydrogel for Human Dental Pulp Engineering. J Mater Chem B 2020, 8, 8422–8432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watcharadulyarat, N.; Rattanatayarom, M.; Ruangsawasdi, N.; Patikarnmonthon, N. PEG–PLGA Nanoparticles for Encapsulating Ciprofloxacin. Sci Rep 2023, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Da Costa, D.; Exbrayat-Héritier, C.; Rambaud, B.; Megy, S.; Terreux, R.; Verrier, B.; Primard, C. Surface Charge Modulation of Rifampicin-Loaded PLA Nanoparticles to Improve Antibiotic Delivery in Staphylococcus Aureus Biofilms. J Nanobiotechnology 2021, 19, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, F.; Bonhome-Espinosa, A.B.; Chato-Astrain, J.; Sánchez-Porras, D.; García-García, Ó.D.; Carmona, R.; López-López, M.T.; Alaminos, M.; Carriel, V.; Rodriguez, I.A. Evaluation of Fibrin-Agarose Tissue-Like Hydrogels Biocompatibility for Tissue Engineering Applications. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 2020, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotitumnavee, J.; Parakaw, T.; Srisatjaluk, R.L.; Pruksaniyom, C.; Pisitpipattana, S.; Thanathipanont, C.; Amarasingh, T.; Tiankhum, N.; Chimchawee, N.; Ruangsawasdi, N. In Vitro Evaluation of Local Antibiotic Delivery via Fibrin Hydrogel. J Dent Sci 2019, 14, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tredwell, S.; Jackson, J.K.; Hamilton, D.; Lee, V.; Burt, H.M. Use of Fibrin Sealants for the Localized, Controlled Release of Cefazolin. Can J Surg 2006, 49, 347–352. [Google Scholar]

- Ducret, M.; Montembault, A.; Josse, J.; Pasdeloup, M.; Celle, A.; Benchrih, R.; Mallein-Gerin, F.; Alliot-Licht, B.; David, L.; Farges, J.-C. Design and Characterization of a Chitosan-Enriched Fibrin Hydrogel for Human Dental Pulp Regeneration. Dental Materials 2019, 35, 523–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galler, K.M.; Krastl, G.; Simon, S.; Van Gorp, G.; Meschi, N.; Vahedi, B.; Lambrechts, P. European Society of Endodontology Position Statement: Revitalization Procedures. Int Endod J 2016, 49, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksel, H.; Mahjour, F.; Bosaid, F.; Calamak, S.; Azim, A.A. Antimicrobial Activity and Biocompatibility of Antibiotic-Loaded Chitosan Hydrogels as a Potential Scaffold in Regenerative Endodontic Treatment. J Endod 2020, 46, 1867–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albuquerque, M.T.P.; Nagata, J.; Bottino, M.C. Antimicrobial Efficacy of Triple Antibiotic–Eluting Polymer Nanofibers against Multispecies Biofilm. J Endod 2017, 43, S51–S56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caballero-Flores, H.; Nabeshima, C.K.; Sarra, G.; Moreira, M.S.; Arana-Chavez, V.E.; Marques, M.M.; Machado, M.E. de L. Development and Characterization of a New Chitosan-Based Scaffold Associated with Gelatin, Microparticulate Dentin and Genipin for Endodontic Regeneration. Dental Materials 2021, 37, e414–e425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccavo, D. An Overview on the Mathematical Modeling of Hydrogels’ Behavior for Drug Delivery Systems. Int J Pharm 2019, 560, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigata, M.; Meinert, C.; Hutmacher, D.W.; Bock, N. Hydrogels as Drug Delivery Systems: A Review of Current Characterization and Evaluation Techniques. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richert, R.; Ducret, M.; Alliot-Licht, B.; Bekhouche, M.; Gobert, S.; Farges, J. A Critical Analysis of Research Methods and Experimental Models to Study Pulpitis. Int Endod J 2022, 55, 14–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zehnder, M.; Belibasakis, G.N. A Critical Analysis of Research Methods to Study Clinical Molecular Biomarkers in Endodontic Research. Int Endod J 2022, 55, 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batoni, E.; Bonatti, A.F.; De Maria, C.; Dalgarno, K.; Naseem, R.; Dianzani, U.; Gigliotti, C.L.; Boggio, E.; Vozzi, G. A Computational Model for the Release of Bioactive Molecules by the Hydrolytic Degradation of a Functionalized Polyester-Based Scaffold. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).