1. Introduction

Papain, a potent proteolytic enzyme, has attracted significant interest from both researchers and industries for its remarkable protein-cleaving abilities. Papain is sourced from the latex of the

Carica papaya, a tropical fruit-bearing plant native to Central and South America [

1]. Throughout ancient times, various parts of the papaya plant, including fruit, leaf, seed, bark, latex, have been utilized for their therapeutic applications [

2]. Latex is a complex mixture of chemical compounds exhibiting diverse chemical activities. These compounds are believed to play a collective role in the plant's defense system [

3]. Papaya latex contains a significant concentration of papain enzyme, which have the ability to break down proteins into smaller peptides and amino acids by hydrolyzing the peptide bonds that hold them together [

4]. Its proteolytic activity, substrate specificity, and stability under diverse conditions make it a versatile tool in fields ranging from food to pharmaceuticals and biotechnology [

5]. Papain's therapeutic potential is evident in the pharmaceutical sector, where it is utilized for its anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and wound-healing properties [

6].

Presently, significant efforts are being directed towards discovering natural products that can serve as effective supplements or potential alternatives to the currently used antithrombotic drugs [

7]. When blood vessels suffer an injury, platelets become activated upon encountering the exposed subcutaneous matrix. They then gather and aggregate at the site of the injury, effectively halting the bleeding process [

8]. Platelet aggregation occurs due to the rupture of atherosclerotic plaques or endothelial injury, which can result in acute thrombotic occlusive ischemic events when the blood supply to tissues is inadequate or gets disrupted due to the presence of a thrombus [

9]. Blood coagulation and platelet-mediated primary hemostasis play critical roles in protecting against bleeding [

10]. The coagulation system responds to endothelial rupture, leading to platelet plug formation [

11]. This triggers a coordinated response leading to the formation of a platelet plug, which initially occludes the vascular lesion. Anticoagulant mechanisms play a vital role in carefully controlling coagulation, prevailing over procoagulant forces in normal conditions [

12]. However, imbalances between the procoagulant and anticoagulant systems, whether due to genetic or acquired factors, can lead to bleeding or thrombotic disorders [

13].

Over the past years, significant research and development efforts have been dedicated to antithrombotic drugs, which can be categorized into three main groups: anticoagulation, antiplatelet aggregation, and fibrinolysis. These drug classes hold promising potential as therapeutic approaches for addressing arterial and venous thrombosis [

14,

15]. Clinical use of drugs includes heparin, warfarin, and their derivatives, primarily employed for inhibiting blood coagulation factors [

16,

17]. Additionally, numerous antiplatelet drugs like aspirin, clopidogrel, and abciximab are extensively used to reduce the risk of cardiovascular diseases [

18,

19]. Moreover, fibrinolytic agents, such as streptokinase, tissue plasminogen activator (t-PA), and reteplase, are utilized to promote the dissolution and removal of formed blood clots [

20,

21].

However, the presently used fibrinolytic enzymes and thrombolytic drugs in clinical settings have a number of adverse effects, including bleeding problems and hemorrhage. This has led many researchers to search for safer alternatives from natural sources for the treatment of thrombotic diseases due to their composition of multiple constituents, each with the potential to target multiple sites. These products can exhibit pleiotropic and synergistic effects, enhancing therapeutic efficacy. Furthermore, the constituents of natural products tend to have fewer side effects on the body system [

22]. In traditional medicine, various natural cysteine protease preparations have been employed to enhance platelet aggregation and address thrombosis-related diseases [

23]. Despite the potential therapeutic benefits of natural cysteine proteases for cardiovascular illnesses, there is a lack of significant human and animal trials to thoroughly investigate these effects [

24,

25]. Hence, the objective of this study is to investigate the fibrin(ogen)olytic, anticoagulant and antithrombotic characteristics of papain, a natural cysteine protease derived from unripe fruit through both

in vitro and

in vivo experimental procedures.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Reagents

Papain, fibrinogen (type I-S from bovine plasma), and thrombin (from bovine plasma) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). PT and aPTT combination test kits were obtained from Vetscan®VSpro (Abaxis Inc., Union City, CA, USA). All reagents utilized in this study were of the highest purity grade.

2.2.Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate-Polyacrylamide Gel Electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE)

Electrophoresis was performed following the Laemmli [

26] method, employing a 12% separating gel and a 4% stacking gel.Papain samples were added to a non-reducing sample buffer composed of 4% SDS, 125 mM Tris-HCl (pH 6.8), 20% glycerol, and 0.01% bromophenol blue, which was stored at -20°C until use. Papain was electrophoresed using the Tris-glycine running buffer at 100 V for 90 minutes. Molecular weight markers ranging from 10 to 200 kDa (Precision plus Protein TM Standards, Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) were run in parallel to determine molecular weight. Following electrophoresis, the gel was stained with 0.125% Coomassie Blue in 40% methanol and 10% acetic acid.

2.3.Proteolytic Activity Assay

Proteolytic activity was evaluated as described by Segers et al. with some slight modifications [

27].The reaction mixture contained 100 µL of papain, 150 µL of reaction sodium bicarbonate buffer (0.5% solution, pH 8.3) (Buffer A), and 250 µL of 2.5% azocasein (w/v) dissolved in Buffer A. After 30 minutes of operation at 37°C, the assays were terminated by adding 400 µL of 10% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid. The precipitated protein was removed by centrifuging the reaction mixture at 12000 rpm for 20 minutes. A UV/visible spectrophotometer (PowerWaveTMXS, BioTek Instruments, Inc., Winooski, VT, USA) was used to measure the absorbance at 440 nm after neutralizing the supernatant (500 µL) by adding 300 µL of sodium hydroxide (500 mM).

2.4.Effect of Temperature and pH on Protease Activity and Stability

An enzyme experiment was run at various temperatures (4–80°C) to establish the protease activity’s optimum temperature. The papain was preincubated at temperatures ranging from 4 to 80°C for 60 min to assess its thermal stability. The ideal pH was identified by doing tests at 4°C in buffers with varied pH values (pH 4, acetate buffer; pH 7, phosphate buffer; pH 10.0 and 11.0, glycine-NaOH buffer). The papain was maintained at 4°C for 30 min in several buffers with pH ranges from 4.0 to 11.0 to test for pH stability. As previously mentioned, residual proteolytic activity was calculated and represented as a percentage of the original activity, which was taken to be 100%.

2.5.Fibrin Plate Assay

The method for assessing fibrinolytic activity was conducted following Astrup and Mullertz's procedure, with slight adjustments made to accommodate the experimental conditions [

28]. Briefly, to create plasminogen-free plates, a solution was prepared by combining 5 mL of 0.6% w/v fibrinogen (Calbiochem, Darmstadt, Germany) with 1% agarose in 50-mM Tris-HCl buffer at (pH 7.8). To initiate the clotting process, 100 µL of thrombin (100 NIH U/mL, Sigma Aldrich) was added to the mixture. The prepared plates were allowed to stand at room temperature (25°C) for 30 minutes to facilitate the formation of a fibrin clot. Small dried filter paper disks with a diameter of 5 mm were placed on the fibrin layer and then incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. Following this, drops of either 20 μL papain at varying concentrations (0, 0.0125, 0.025, 0.05, or 0.1 U) or a positive control (plasmin at 1 mg/mL) were applied to the disks. Fibrin degradation was evident by the presence of clear, translucent zones surrounding the disks. The efficacy of this degradation was directly proportional to the diameter of these zones, indicating a stronger and more extensive fibrinolytic activity. The fibrinolysis area (in mm

2) was quantified by measuring the diameters of the fine rings formed around each sample using ImageJ software. By determining the mean diameter of the hydrolyzed clear zone, the extent of lysis induced by each sample was calculated.

2.6. Examination of Fibrinolytic Activity Using Fibrin Zymography

The zymography assay assessed fibrinolytic activity by utilizing fibrin as the substrate. For the preparation of the zymography gel, a solution containing 20 mM sodium phosphate buffer at pH 7.4 was utilized. This solution included dissolved fibrinogen at a concentration of 0.6 mg/mL and thrombin at a concentration of 0.01 unit/mL. The copolymerization process involved mixing these components with 12% polyacrylamide to create the appropriate gel for the experiment. To analyze papain, a non-reducing sample buffer was employed subsequently, the prepared papain samples were subjected to gel electrophoresis at 100 V and 4°C. After the electrophoresis process, the gel was subjected to washes for two times, each lasting for 30 minutes, in a 2.5% Triton X-100 solution to remove SDS. Following the treatment with 20 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 0.5 mM calcium chloride, and 200 mM sodium chloride at 37°C for 16 hours, the gel was subsequently stained with 0.125% Coomassie blue. The regions of fibrinolytic activity were visually evident as clear zones on the gel.

2.7. Fibrinogenolytic Activity

The fibrinogenolytic activity of papain was investigated following the protocol described by Matsubara

et al [

29]. In briefly, the experiment involved adding reaction buffer (pH 7.4, 200 mM sodium chloride, 0.5 mM calcium chloride, and 20 mM Tris) to 15 µL of bovine fibrinogen at a concentration of 20 mg/mL. The mixture was then incubated at 37°C for specific time periods and dosages. To analyze the digested products, a 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel was employed.

2.8. Blood Clot Lysis Assay

Venous blood samples were collected from healthy Mongolian dogs and dispensed into multiple pre-weighed, sterile microcentrifuge tubes, with each tube containing 500 μL of blood. The tubes were then incubated for 45 minutes at a temperature of 37°C. Upon the formation of blood clots, all the serum was carefully removed from each tube, and the tubes containing the clots were reweighed to determine their weight (clot weight = weight of tube with clot - weight of empty tube). Each microcentrifuge tube containing the blood clot was appropriately labeled, and varying concentrations of papain (ranging from 0 to 1 U/mL) were then introduced into the respective tubes. For the negative control, phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was added to each tube containing clots, while for the positive control, streptokinase (SK, 1000 U) was added to each tube with clots. All the tubes were subjected to a 24-hour incubation at 37°C, during which they were closely monitored for any signs of clot lysis. Following the incubation period, the fluids from each tube were collected. Subsequently, the tubes were reweighed to ascertain the weight difference after the breakdown of the blood clots. The proportion of clot lysis was calculated by comparing the weight of the tubes before and after the clot lysis process.

2.9. PT/aPTT Measurement

Prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) measurements were employed to investigate the impact of papain on blood coagulation. For the coagulation tests, blood samples were drawn from Mongolian dogs and mixed with a solution containing 3.2% sodium citrate (1:9, v/v) along with different papain concentrations. The mixture was allowed to incubate for 10 minutes at room temperature. The mixtures, following the 10-minute incubation, were evaluated using an aPTT and PT combination test kit (Vetscan®VSpro PT/aPTT combination test cartridge, Abaxis Inc., Union City, CA, USA).

2.10. Experimental Animals

Four-week-old male Sprague Dawley (SD, 150-160 g of body weight) rats that were obtained from Samtako Inc. (Osan, Korea)and housed in the lab of the Gyeongsang National University animal research facility. The rats were housed in standard cages under conventional conditions, which included a 12-hour light/dark cycle and ad libitum access to conventional chow meal (8% protein, 5% fat, 4.5% fiber, 8% carbohydrate, 0.7% calcium, 1.2% phosphorus, and 14% moisture) and water. The environmental conditions maintained an ambient temperature of 23 ± 2°C, with a relative humidity ranging from 35 to 60 percent. The animal study protocol used in this research was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Gyeongsang National University, with the protocol number GNU-200122-R0003.

2.11. κ-Carrageenan-Induced Rat-Tail Thrombosis Model

We first determined the toxic doses of papain in rats. In our pilot study, 2.5 to 10 U/kg of papain was not found to have an abnormal or toxic effect when administered to rats (data not shown). A total of 25 male SD (5-week-old) rats were randomly allocated into five groups (n=5 per group); group 1, vehicle-treated group (Control); group 2, 3, and 4, 2.5 U/kg, 5 U/kg, and 10 U/kg papain with κ-carrageenan, respectively; group 5, A dose of streptokinase 2000 U (mL/kg) with κ-carrageenan group (positive control). First, κ-carrageenan (1 mg/kg) was dissolved in saline and injected into the dorsal tail vein of the rat. Following the ligation of a site 12 cm from the tip of the rat tail, 1 mg/kg of κ-carrageenan was administered intravenously in order to measure thrombogenesis. After being ligated for 20 minutes, the ligation was removed. The experimental groups were given papain and streptokinase intravenously for 1 hour before receiving κ-carrageenan. The frequency of infarction and the length of the infarcted region at the tail tip were recorded 48 hours after κ-carrageenan injection.

2.12. Statistical Analysis

The results were obtained from a minimum of two or three independent experimental conditions and were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (S.D.). Statistical analysis was determined by t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnett’s post hoc test using SPSS version 13.0. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. Discussion

With the rapid advancements in science and technology, traditional medicine has emerged as an appealing subject for researchers. Particularly, there is a growing interest in conducting evidence-based research on natural products, not only to explore their traditional uses but also to potentially develop them into formal medications. Papain, derived and identified from

C. papaya, is categorized as a cysteine protease and recognized as a proteolytic enzyme, relying on the presence of a free sulfhydryl group for its enzymatic activity [

30]. Consequently, it has been employed as a conventional therapeutic approach for diverse medical conditions [

31]. The plant's medicinal properties can be attributed to its antioxidative nature, which offers cellular protection against oxidative stress-induced harm [

32]. Papain is an extensively utilized proteolytic enzyme, renowned for its contributions to meat tenderization and aiding digestion [

33]. Papain is also regarded as having significant pharmacological potential, with drug-like properties that might aid in the treatment of atherosclerosis and related illnesses. Its effectiveness lies in addressing monocyte-platelet aggregate (MPA)-regulated inflammation [

34]. Thrombotic disorders, marked by the development of blood clots, play a substantial role in causing illness and death on a global scale [

35]. Hence, the investigation of natural compounds possessing potential thrombolytic properties holds immense promise in the pursuit of alternative and efficient therapeutic approaches [

36]. In this study, we investigated the fibrin(ogen)lytic, anticoagulant, and antithrombotic activities of papain, a natural cysteine protease derived from papaya plant latex, using the κ-carrageenan-induced rat tail thrombosis model.

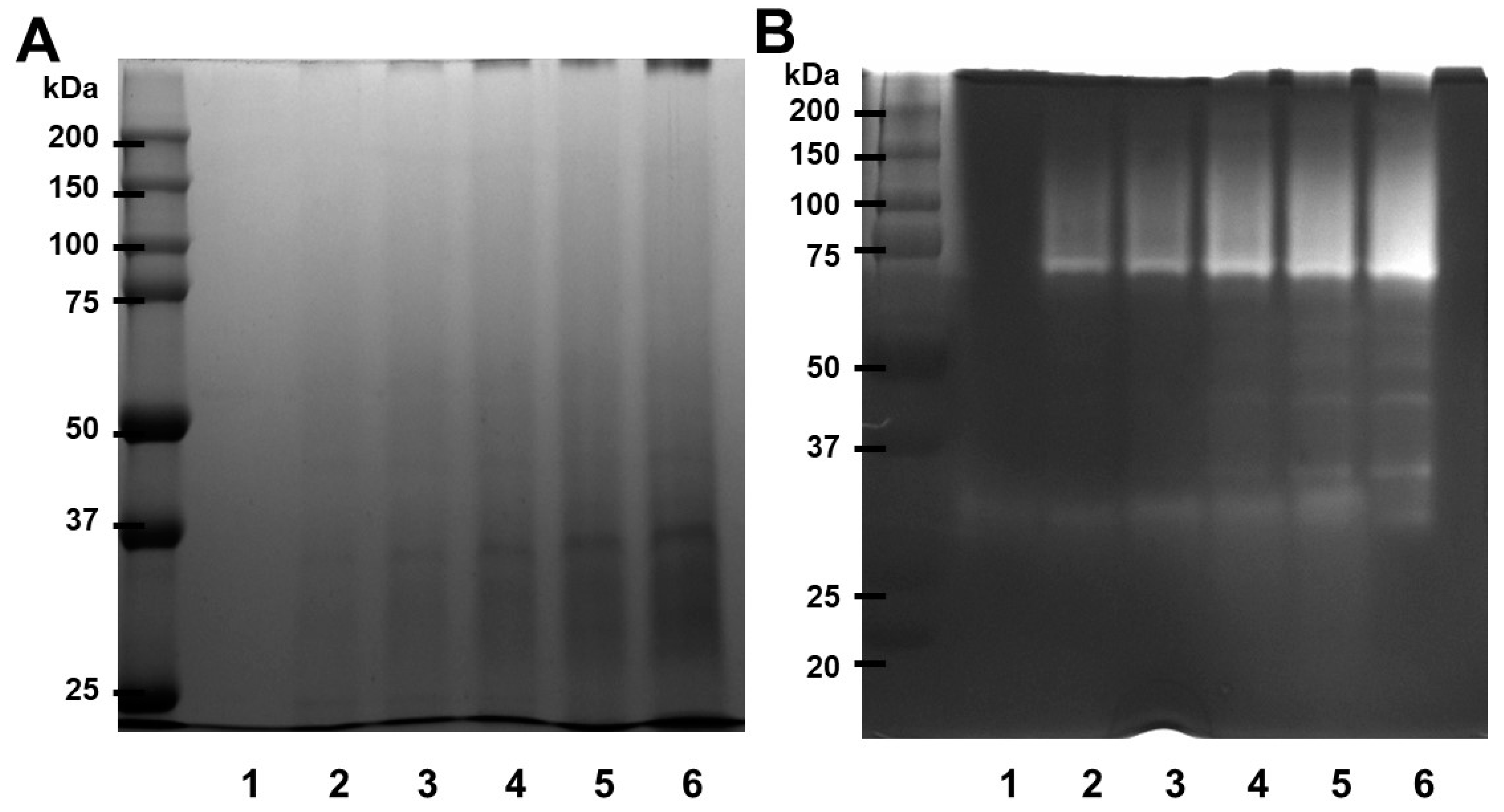

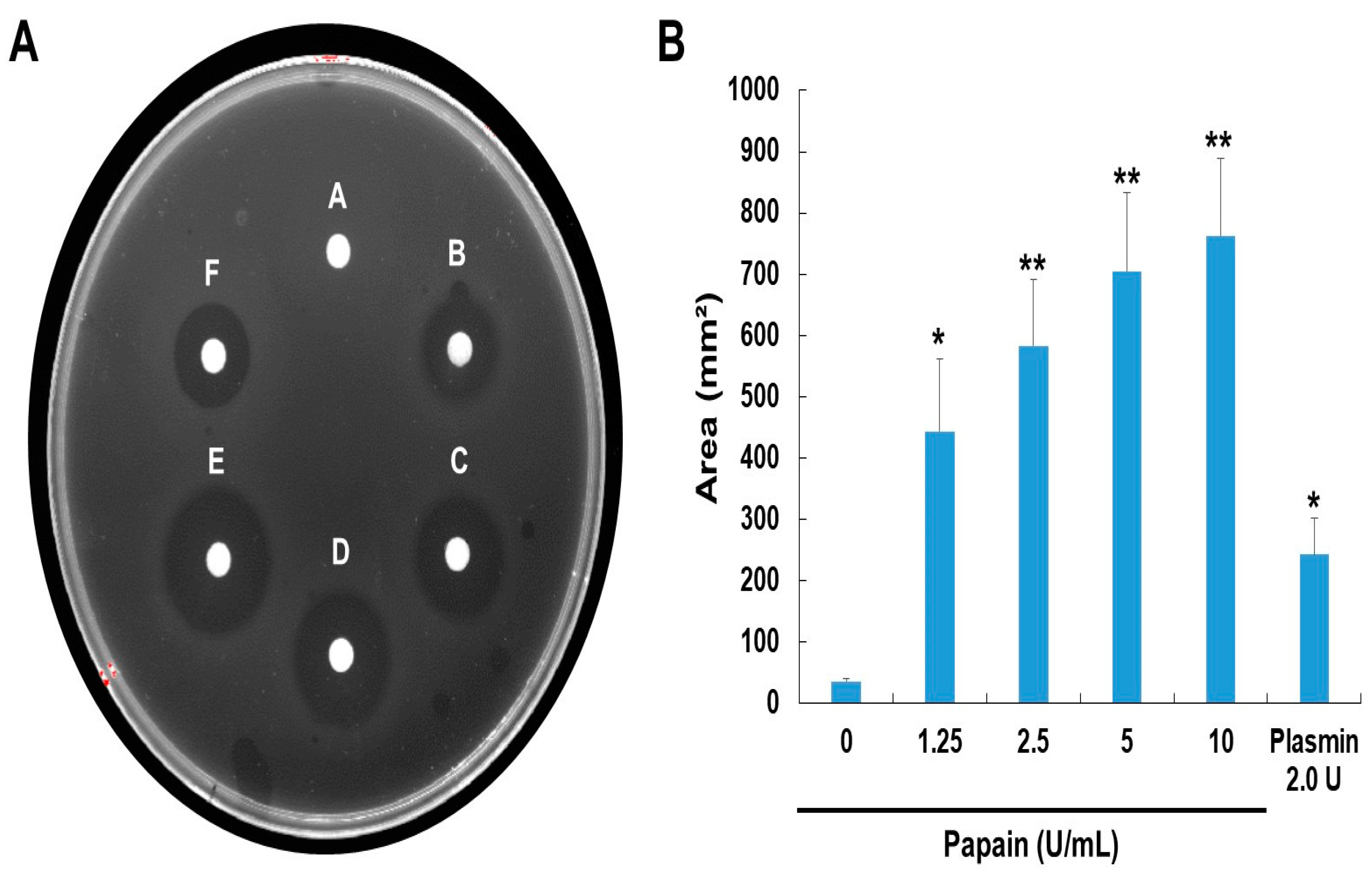

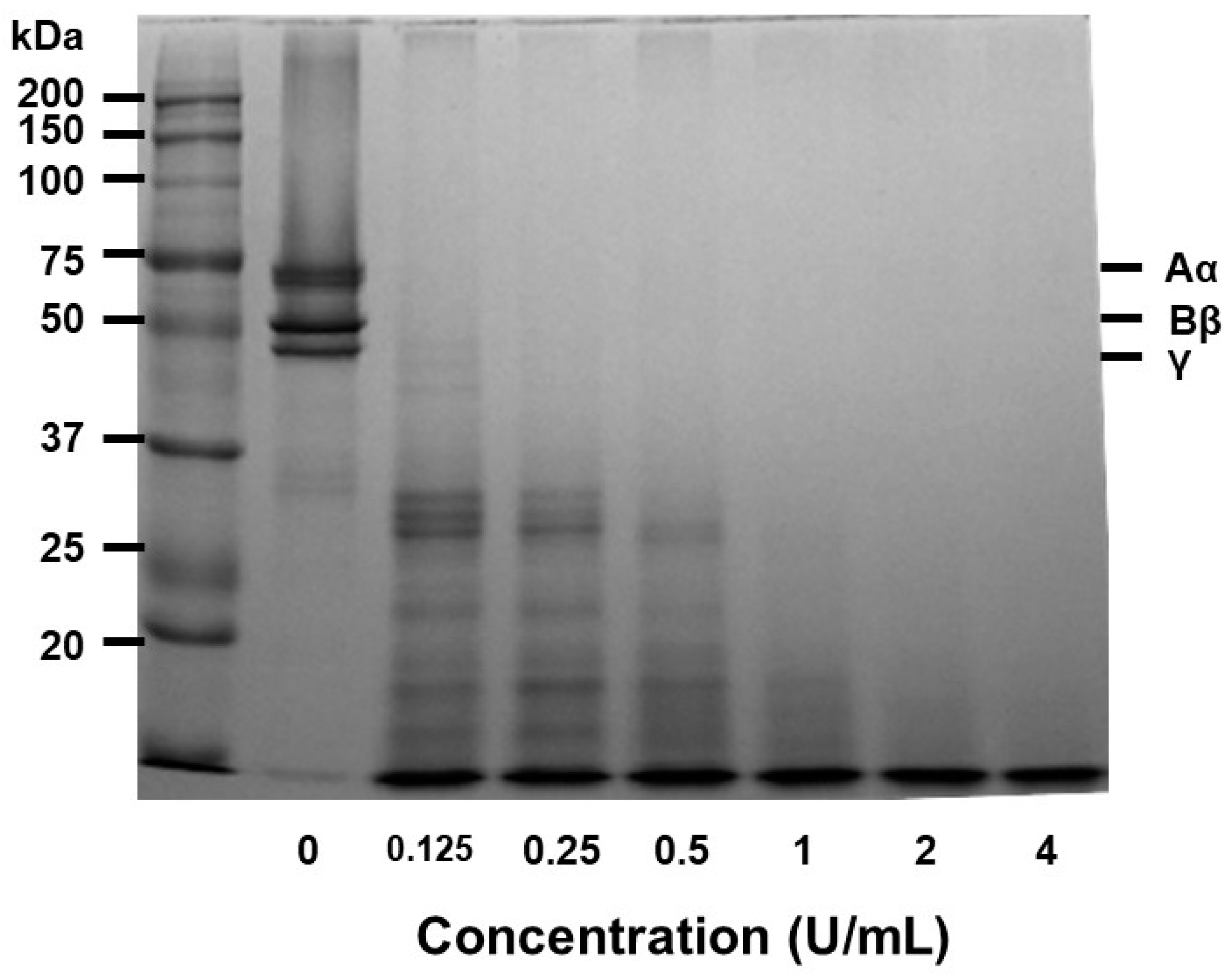

Our experimental findings demonstrated that the combination of SDS-PAGE and fibrin zymography yielded comprehensive insights into the structural stability and fibrinolytic potential of papain (

Figure 1). In comparison with our previously published research [

23] with ficin (24-50 kDa) and current study with papain (37-75 kDa), these are enzymes with fibrinolytic activity capable of degrading fibrin. They exhibit differences in molecular weight as detected under different conditions, indicating potential conformational changes or interactions. These findings not only enhance our understanding of papain's activity but also pave the way for its potential applications in medical and therapeutic contexts. The fibrin plate assay results also demonstrate papain's potential as a fibrinolytic agent, with clear zones rising in size as concentrations increase (

Figure 2). Papain showed a broader range of fibrinolytic activity (0 U/mL to 10 U/mL) compared to ficin (0 U/mL to 0.1 U/mL). Particularly at elevated concentrations, it appears to approximate the effectiveness displayed by plasmin (

Figure 3). This emphasizes papain’s effectiveness in fibrin degradation, which is crucial for clot removal and tissue remodeling. These findings are pertinent to medical contexts where fibrinolysis is crucial in conditions like wound healing, thrombosis, and heart disorders [

37]. Papain also exhibited a significant fibrinogenolytic property, with the Aα and Bβ subunits being susceptible to degradation, while the γ subunits were completely hydrolyzed with an increasing dose (

Figure 4).

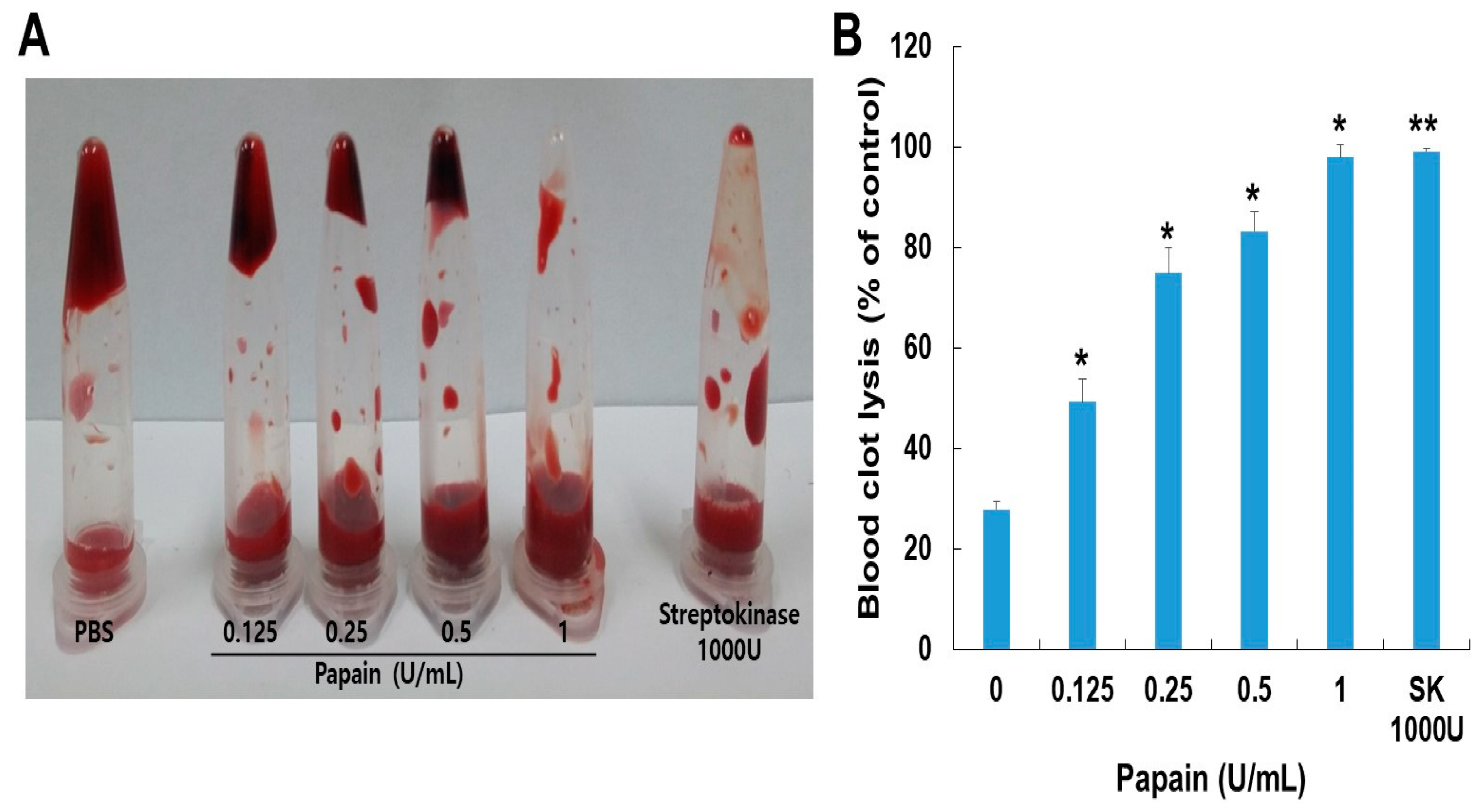

Fibrinolysis is a critical process involved in dissolving blood clots by cleaving fibrin, the main component of thrombi [

38]. Besides, papain demonstrated with the significant influence on blood clot lysis across the range of concentrations through

in vitro analysis. Incubating the whole blood clot with papain (0.0125–0.1 U) resulted in the dissolution of 99% of the clot, comparable to the effect achieved by streptokinase (1000 U/mL).The observed clot lysis potential in response to papain treatment, compared to streptokinase, suggests papain's potential as a thrombolytic agent (

Figure 5). aPTT and PT are coagulation parameters that offer valuable information about an individual's hemostatic condition [

39]. Natural cysteine protease has an impact on both the internal and external coagulation pathways [

36]. PT primarily reflects the extrinsic coagulation factors FII, V, VII, and X. The intrinsic coagulation system, comprising factors VIII, IX, XI, and XII, serves as a screening test for aPTT. Papain at a concentration of 8 U/mL exhibits anticoagulant properties, as evidenced by its ability to extend both the prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) (

Table 1). This suggests that papain exerts its anticoagulant effects by targeting both the exogenous and endogenous coagulation pathways while also inhibiting the conversion of fibrinogen into fibrin, thereby impeding the clotting process. Consequently, papain demonstrates anticoagulant properties by influencing endogenous anticoagulation mechanisms.

Fibrinolytic enzymes have been successfully isolated from a wide range of sources [

40]. Streptokinase, urokinase, pro-urokinase, reteplase, and alteplase, among other fibrinolytic enzymes and thrombolytic medicines presently utilized in clinical settings, have considerable undesirable physiological side effects. These include heightened bleeding risk, a short plasma half-life, restricted fibrin specificity, and the necessity for high therapeutic dosages [

41,

42]. As a consequence, the search for more inexpensive and safer fibrinolytic enzymes and thrombolytic medications derived from natural sources becomes a crucial issue. Numerous studies have revealed with the utilization of papain in traditional medicine [

37]. The results of the present study indicate that papain holds promise as a potential source of fibrinolytic and thrombolytic agents.

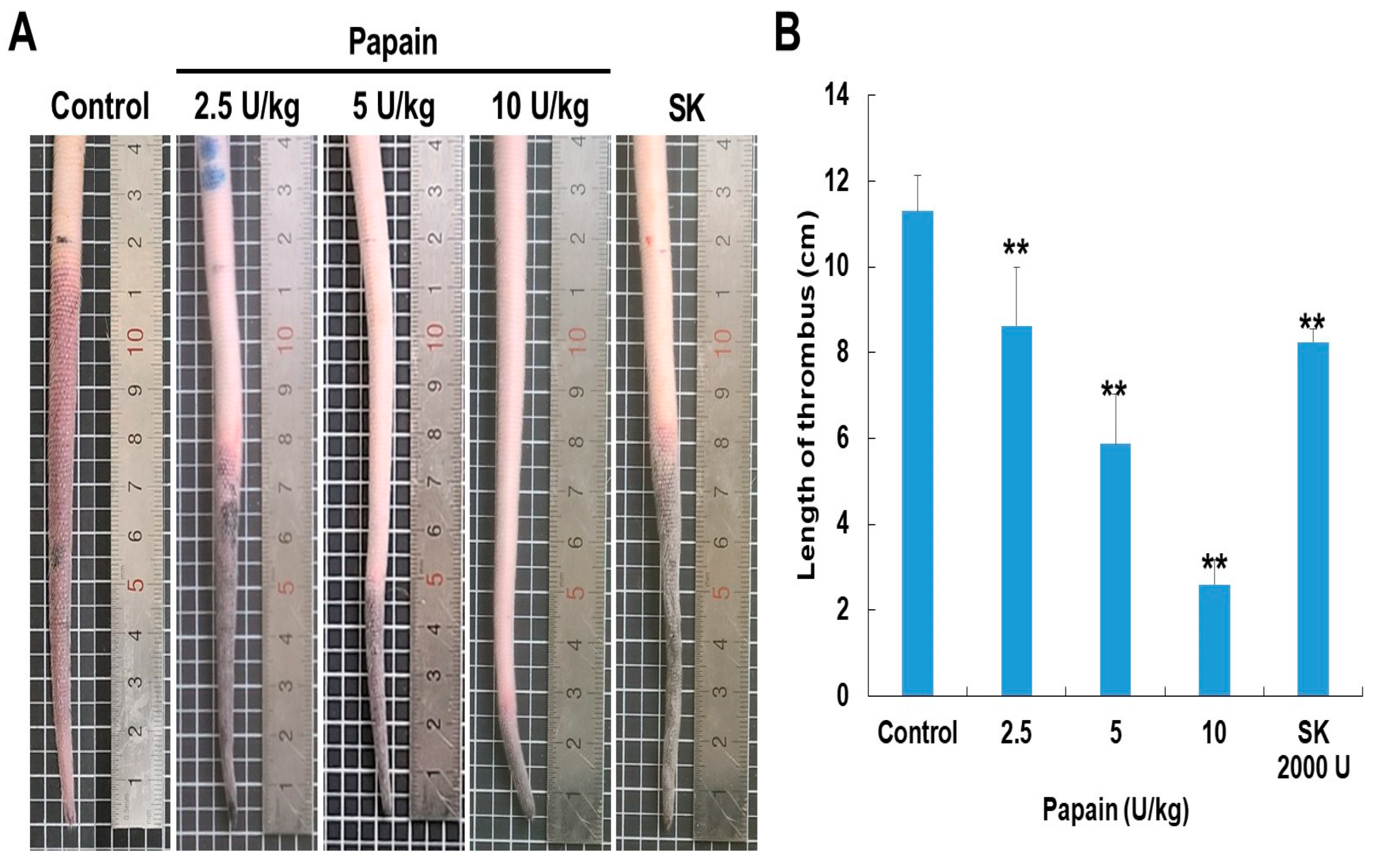

Upon intravenous administration, κ-carrageenan induces the production of histamine and serotonin by immune cells, leading to acute inflammation of blood vessels in various animal species [

43]. So, κ-carrageenan administration in the tail veins is strongly linked to thrombus development and inflammation. We therefore used the rat tail thrombus model induced by κ-carrageenan to evaluate the

in vivo antithrombotic activity of papain. Papain has a dose-dependent antithrombotic potential in rat tails, either delaying the development of thrombi or dissolving pre-existing ones (

Figure 6). In our previous study, we also investigated the effectiveness of ficin in both preventing thrombus formation and dissolving pre-formed thrombi. Our findings suggest that papain (10 U/kg, a mean thrombus length of 2.8±0.4 cm) exhibits superior thrombus-modulating properties compared to ficin (10 U/kg, a mean thrombus length of 8.8±0.3 cm), presenting it as a potential candidate for future therapeutic interventions targeting thrombotic disorders. Therefore, papain proves to be a highly effective antithrombotic agent, holding significant potential for further exploitation and development. This initial examination of the effects of papain on the coagulation and fibrinolysis systems carries broad implications across various indication. The research primarily identifies natural cysteine proteases that offer promise as possible sources for pharmacological therapies for various hemostatic disorders. There is increasing evidence that cysteine proteases are linked to the physiological processing of chemokines. One example is cathepsins, which were originally isolated from macrophages, and inflammatory cytokines increase cathepsin secretion from macrophages [

44]. Furthermore, recent

in vivo study of cathepsin demonstrate that this enzyme is involved in leukocyte infiltration, endothelial cell invasion, and neovascularization [

45]. Thus, natural cysteine protease may have a function in regulating cytokines and chemokines under inflammation, implying that papain could play a significant role in atherogenesis and thrombosis-related disorders.

In conclusion, we investigated papain, a natural cysteine protease, for its varied fibrin(ogen)lytic activities, anticoagulant, and antithrombotic effects using the κ-carrageenan-induced rat tail thrombosis model. The findings of the research provide valuable insights into the effects of papain on blood clotting and thrombosis formation. In addition, Papain's anticoagulant activity indicates its potential to reduce blood clot formation by inhibiting the coagulation cascade. These findings could lead the way for novel antithrombotic treatments, utilizing papain or its derivatives. Additional research is needed to explore papain's impact on cytokine and chemokine-linked inflammatory process to uncover its molecular mechanism of action.

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE profile and fibrinolytic activity of papain. (A) Papain was submitted to SDS electrophoresis under non-reducing conditions. The gels were treated with a 0.125% solution of Coomassie blue stain. (B) Different concentrations of papain were used for fibrin zymography. The presence of clear zones in the fibrin gel indicated the areas where proteolytic activity occurred. Lane 1 – 0, lane 2 – 0.125, lane 3 – 0.25, lane 4 – 0.5, land 5 – 1, lane 6 – 2 (U/mL).

Figure 1.

SDS-PAGE profile and fibrinolytic activity of papain. (A) Papain was submitted to SDS electrophoresis under non-reducing conditions. The gels were treated with a 0.125% solution of Coomassie blue stain. (B) Different concentrations of papain were used for fibrin zymography. The presence of clear zones in the fibrin gel indicated the areas where proteolytic activity occurred. Lane 1 – 0, lane 2 – 0.125, lane 3 – 0.25, lane 4 – 0.5, land 5 – 1, lane 6 – 2 (U/mL).

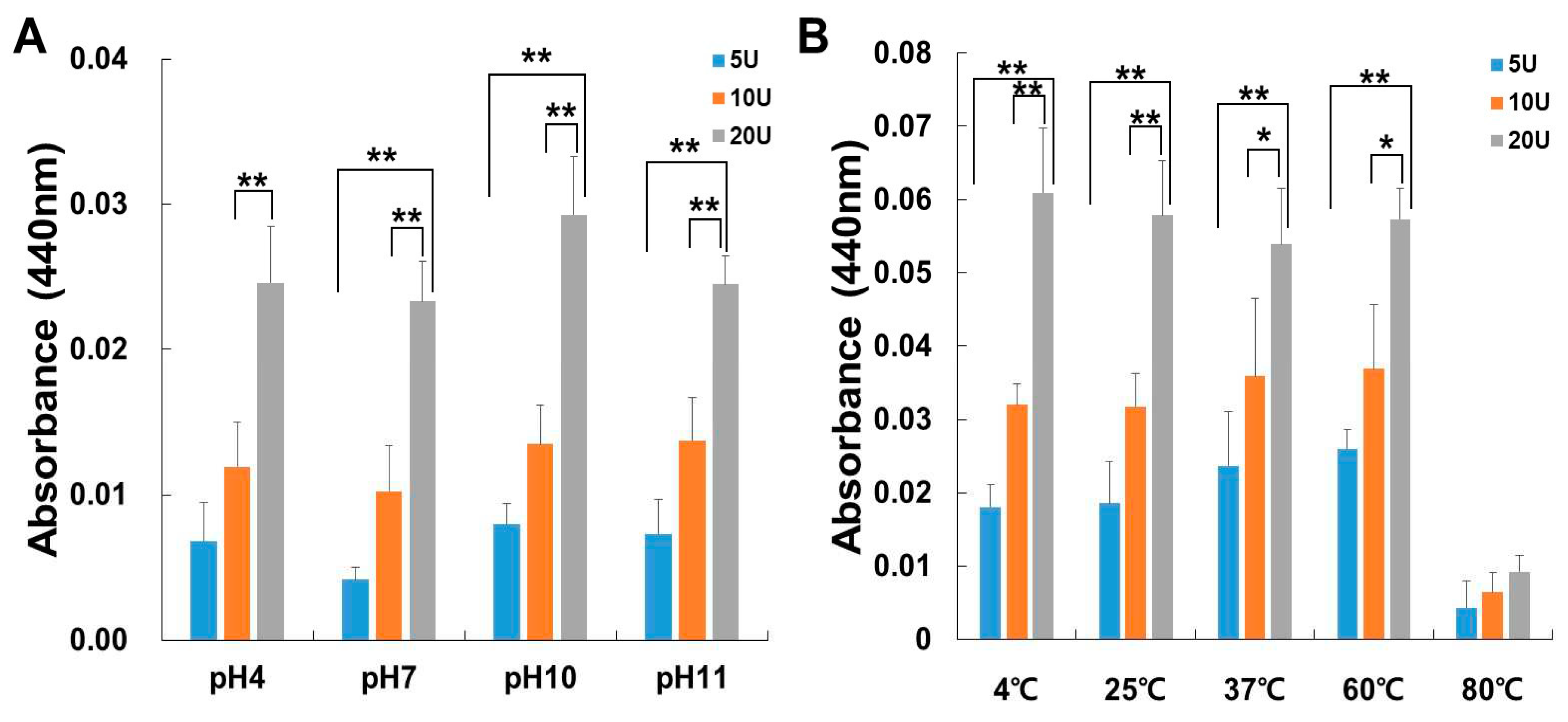

Figure 2.

The influence of pH (A) and temperature (B) on the enzyme activity of papain. The enzyme activity was assessed using azocasein assays, and the measurements were taken at 440 nm. (A) The papain activity was examined by incubating at 37°C for 30 minutes while varying the pH levels at 4, 7, 10, and 11. (B) Papain activity was evaluated following incubation over a temperature range spanning from 4°C to 80°C. The data shown are the mean ± SD (n=4) of three independent experiments. *p<0.05, and **p< 0.01 vs each group after ANOVA and Dunnett’s test.

Figure 2.

The influence of pH (A) and temperature (B) on the enzyme activity of papain. The enzyme activity was assessed using azocasein assays, and the measurements were taken at 440 nm. (A) The papain activity was examined by incubating at 37°C for 30 minutes while varying the pH levels at 4, 7, 10, and 11. (B) Papain activity was evaluated following incubation over a temperature range spanning from 4°C to 80°C. The data shown are the mean ± SD (n=4) of three independent experiments. *p<0.05, and **p< 0.01 vs each group after ANOVA and Dunnett’s test.

Figure 3.

Fibrinolytic activity of papain. (A) Fibrinolytic activity was assessed using a fibrin plate assay. The samples were applied to the disc on the plate and then incubated at 37°C overnight. (B) Fibrinolytic activity was quantified based on the size of clear zones. The data shown are the mean ± SD (n=4) of three independent experiments. *p<0.05, and **p<0.01 vs control group after ANOVA and Dunnett’s test.

Figure 3.

Fibrinolytic activity of papain. (A) Fibrinolytic activity was assessed using a fibrin plate assay. The samples were applied to the disc on the plate and then incubated at 37°C overnight. (B) Fibrinolytic activity was quantified based on the size of clear zones. The data shown are the mean ± SD (n=4) of three independent experiments. *p<0.05, and **p<0.01 vs control group after ANOVA and Dunnett’s test.

Figure 4.

The impact of papain on fibrinogen. Fibrinogenolytic activity was assessed using SDS-PAGE after incubating human fibrinogen with different concentrations of papain at 37°C for 30 minutes. The mixture samples were subjected to electrophoresis on a 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel and subsequently stained with Coomassie blue. Fibrinogen is composed of three polypeptide chains: Aα, Bβ, and γ.

Figure 4.

The impact of papain on fibrinogen. Fibrinogenolytic activity was assessed using SDS-PAGE after incubating human fibrinogen with different concentrations of papain at 37°C for 30 minutes. The mixture samples were subjected to electrophoresis on a 7.5% SDS-PAGE gel and subsequently stained with Coomassie blue. Fibrinogen is composed of three polypeptide chains: Aα, Bβ, and γ.

Figure 5.

(A) The impact of papain on in vitro thrombolysis. (B) Clot lysis was examined through different concentrations of papain alongside streptokinase for 24 hour. Streptokinase which served as the positive control. The data shown are the mean ± SD (n=4) of three independent experiments.*p<0.05, and **p< 0.01 vs control group after ANOVA and Dunnett’s test.

Figure 5.

(A) The impact of papain on in vitro thrombolysis. (B) Clot lysis was examined through different concentrations of papain alongside streptokinase for 24 hour. Streptokinase which served as the positive control. The data shown are the mean ± SD (n=4) of three independent experiments.*p<0.05, and **p< 0.01 vs control group after ANOVA and Dunnett’s test.

Figure 6.

Papain prevents κ-carrageenan-induced thrombosis in Sprague-Dawley rats. (A) Representative photographs taken 48 hours after carrageenan injection. In the control group (κ-carrageenan injected alone), the thrombus length measured 11.6±0.4 cm. The thrombus length in the papain-treated groups showed a reduction in a dose-dependent manner. (B) The bar diagram illustrated the inhibitory effects of papain and streptokinase on tail thrombus formation at 48 hours. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n=5) of three independent experiments. *p<0.05, and **p< 0.01 vs control group after ANOVA and Dunnett’s test.

Figure 6.

Papain prevents κ-carrageenan-induced thrombosis in Sprague-Dawley rats. (A) Representative photographs taken 48 hours after carrageenan injection. In the control group (κ-carrageenan injected alone), the thrombus length measured 11.6±0.4 cm. The thrombus length in the papain-treated groups showed a reduction in a dose-dependent manner. (B) The bar diagram illustrated the inhibitory effects of papain and streptokinase on tail thrombus formation at 48 hours. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD (n=5) of three independent experiments. *p<0.05, and **p< 0.01 vs control group after ANOVA and Dunnett’s test.

Table 1.

The anticoagulation test was estimated using mongrel dog blood. The PT and aPTT levels were measured through an anticoagulation test. Hence, dog blood samples were incubated with papain at specified concentrations for the evaluation. Fresh citrated dog blood was preincubated with various concentrations of papain for a duration of 10 minutes. The data shown are the mean ± SD (n=3) of three independent experiments. s=Seconds.

Table 1.

The anticoagulation test was estimated using mongrel dog blood. The PT and aPTT levels were measured through an anticoagulation test. Hence, dog blood samples were incubated with papain at specified concentrations for the evaluation. Fresh citrated dog blood was preincubated with various concentrations of papain for a duration of 10 minutes. The data shown are the mean ± SD (n=3) of three independent experiments. s=Seconds.

| Papain |

PT (s) |

aPTT (s) |

| Control |

17.5±1.8 |

93.9±4.1 |

| 4 U/mL |

18.2±1.6 |

100.4±5.8 |

| 8 U/mL |

35 < |

400 < |

| *Normal range |

14–19 |

75–105 |