Submitted:

26 August 2023

Posted:

29 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

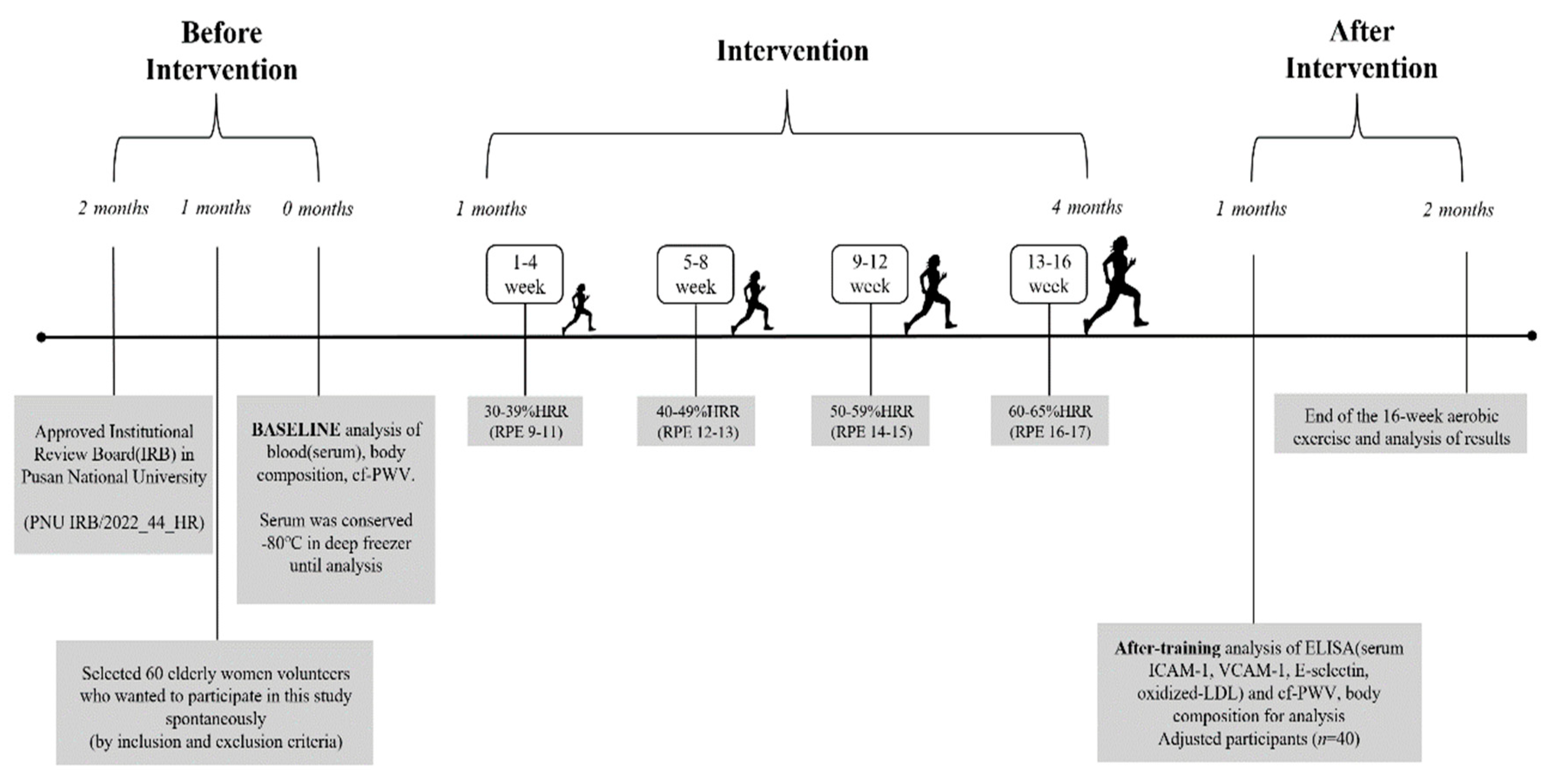

2. Materials and Methods

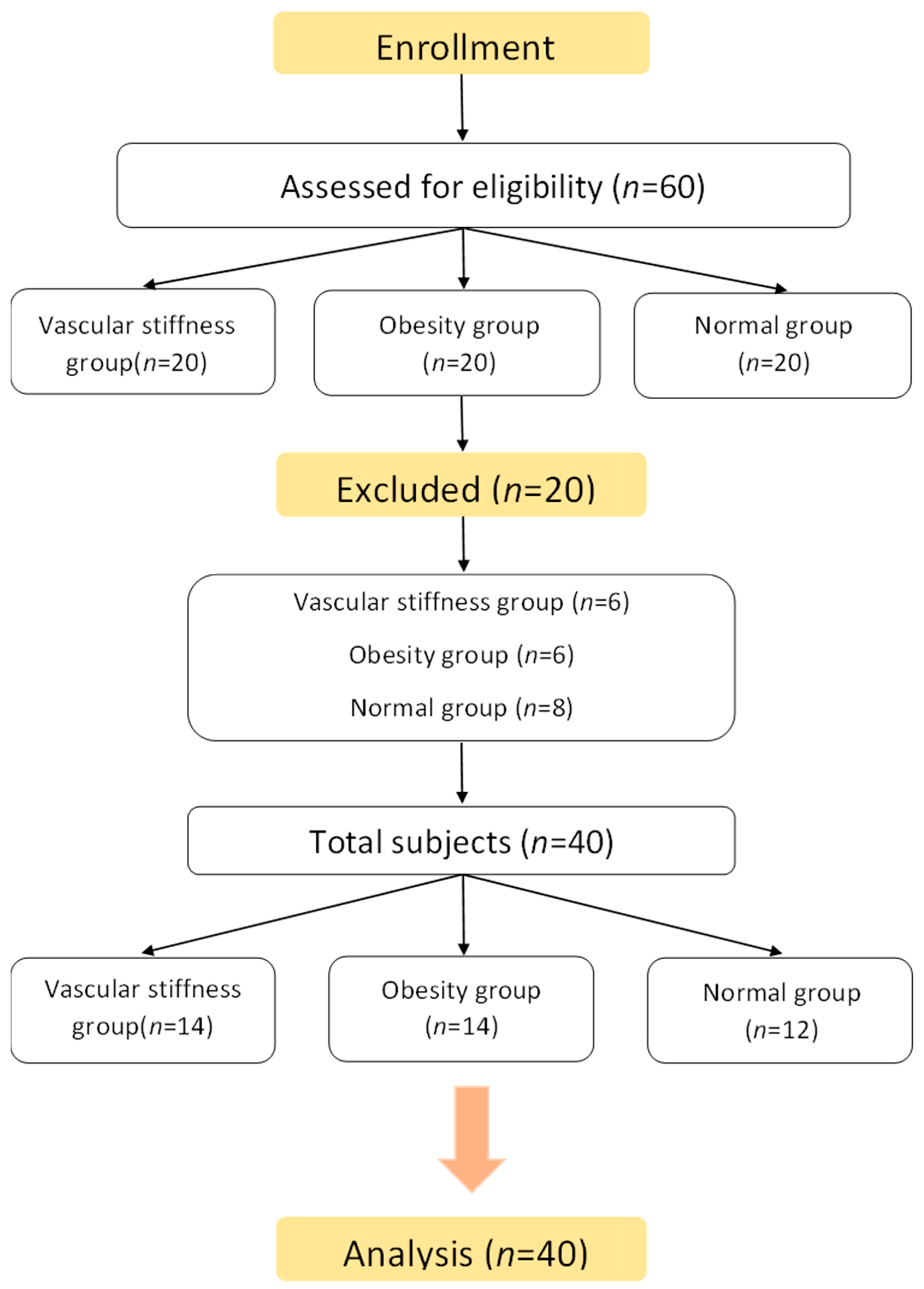

2.1. Participants

2.2. Aerobic Exercise Program

3. Data Collection

3.1. Body Composition

3.2. Blood Collection

3.3. Vascular Stiffness Analysis

3.4. Blood Analysis

3.5. Data Analysis

4. Results

4.1. Changes in cf-PWV

4.2. Changes in CAM

4.2.1. ICAM-1

4.2.2. VCAM-1

4.2.3. E-selectin

4.3. Changes in Oxidized-LDL

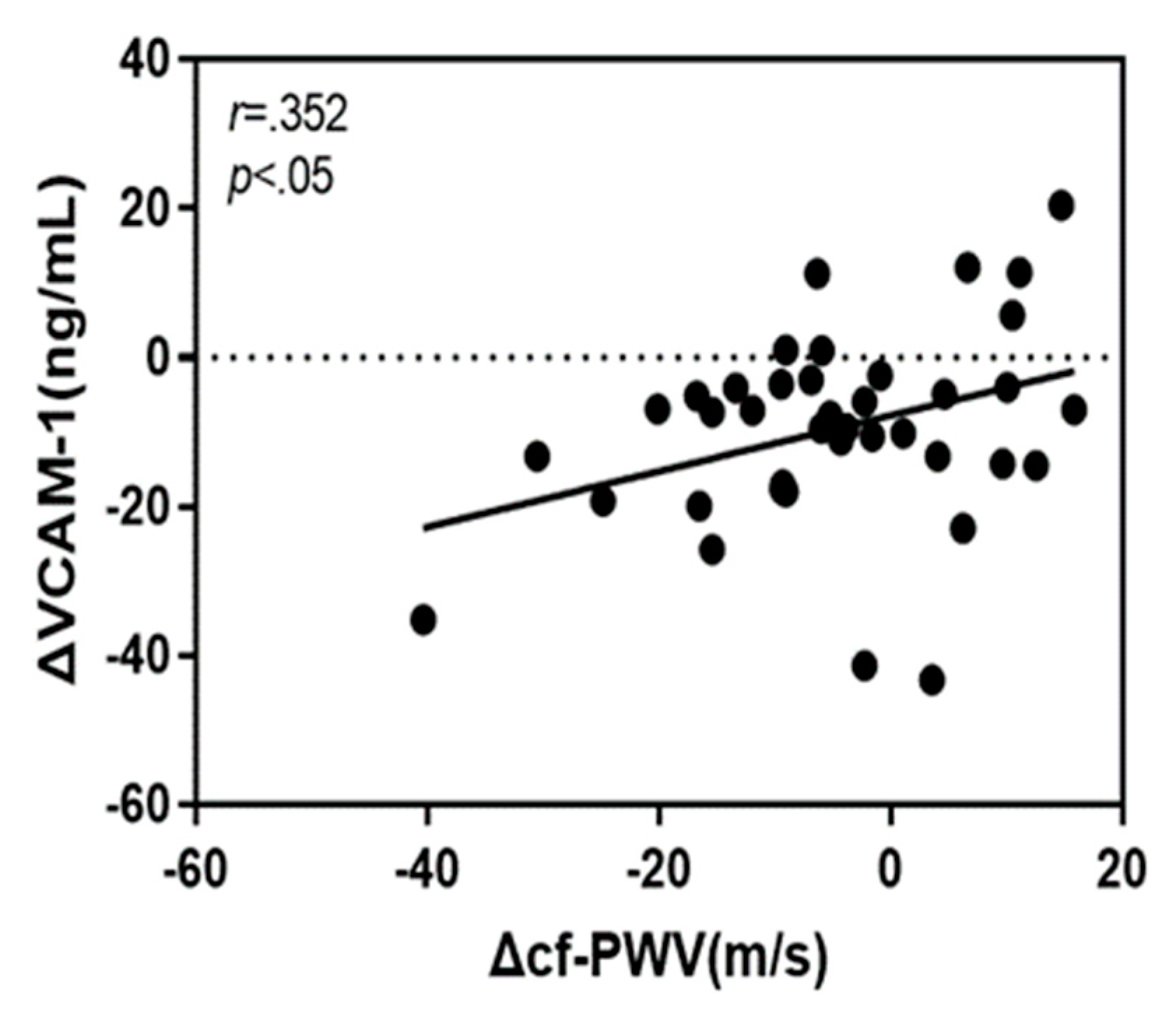

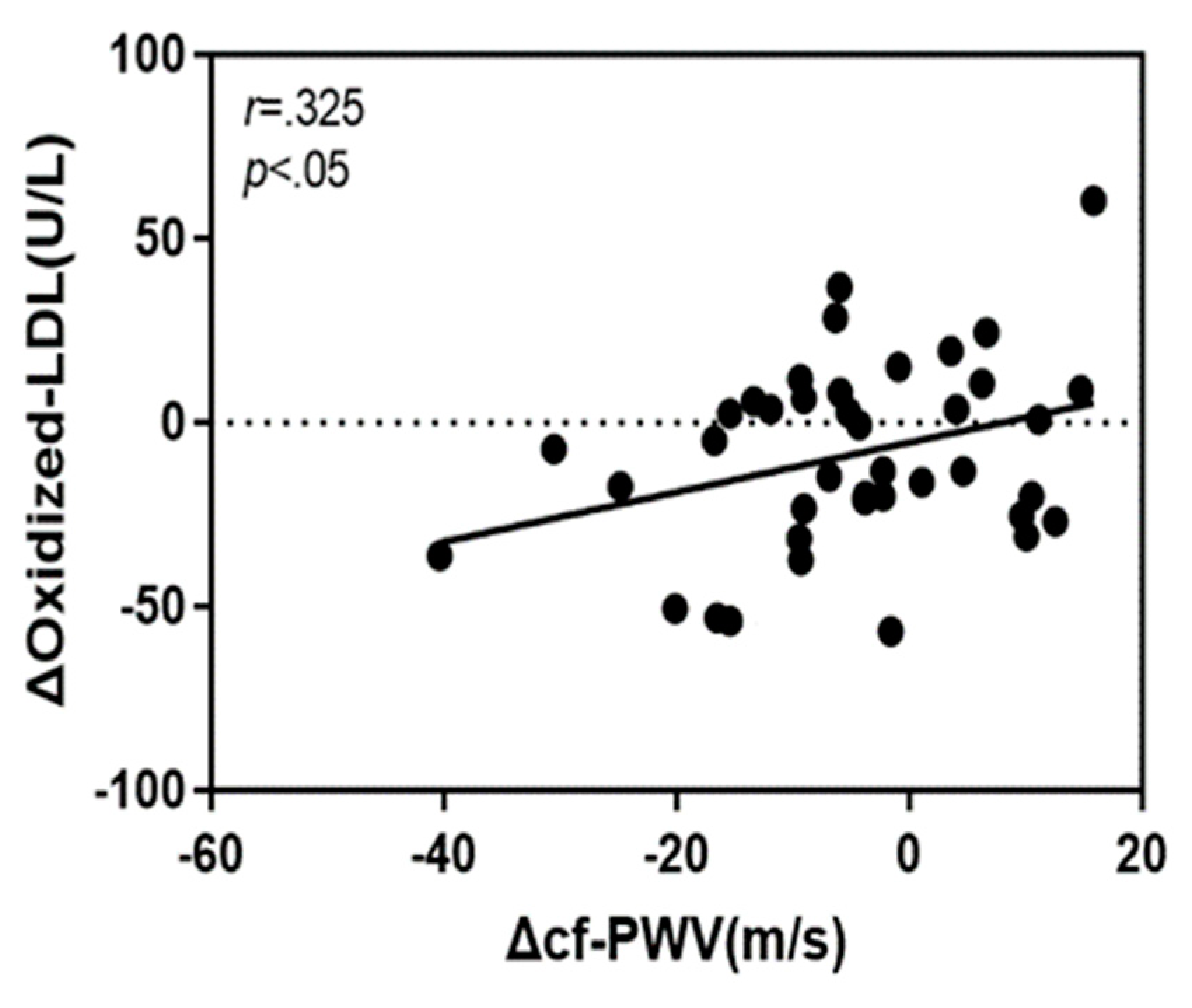

4.4. Correlation of the Rate of Change of cf-PWV with VCAM-1 and Oxidized-LDL

4.5. Analysis of the Effects of cf-PWV, VCAM-1 and Oxidized-LDL

5. Discussion

References

- Habas, K.; Shang, L. Alteration in intercellular adhesion molecule 1(ICAM-1) and vascular cell adhesion molecule 1(VCAM-1) in human endothelial cells. Tissue and Cell 2018, 54, 139–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, C.H.; Kuo, F.C.; Tang, W.H.; Lu, C.H.; Su, S.C.; Liu, J.S.; Hsieh, C.H.; Hung, Y.J.; Lin, F.H. Serum E-selectin concentration is associated with risk of metabolic syndrome in female. Plos One 2019, 14, e0222815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qui, S.; Cai, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, B.; Zugel, M.; Steinacker, J.M.; Sun, Z.; Schumann, U. Association between circulating cell adhesion molecules and risk of type 2 diabetes: A meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis 2019, 287, 147–154. [Google Scholar]

- Saud, A.; Ali, N.A.; Gali, F.; Hadi, N. The role of cytokines, adhesion molecules, and toll-like receptors in atherosclerosis progression: the effect of Atorvastatin. Journal of Medicine and Life 2022, 15, 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, E.M.; Pearce, S.W.; Xiao, Q. Foam cell formation: A new target for fighting atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. Vascular Pharmacology 2018, 112, 54–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Zhao, D.; Wang, M.; Zhao, F.; Han, X.; Qi, Y.; Liu, J. Association between circulating oxidized LDL and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Canadian Journal of Cardiology 2017, 33, 1624–1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Zhang, H.W.; Xu, R.X.; Guo, Y.L.; Zhu, C.G.; Wu, N.Q.; Gao, Y.; Li, J.J. Oxidized-LDL is a useful marker for predicting the very early coronary artery disease and cardiovascular outcomes. Personalized Medicine 2018, 15, 521–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honda, S.; Ikede, K.; Urata, R.; Yamazaki, E.; Emoto, N.; Matoba, S. Cellular senescence promotes endothelial activation through epigenetic alteration and consequently accelerates atherosclerosis. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koh, Y.; Park, J. Cell adhesion molecules and exercise. Journal of Inflammation Research 2018, 11, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.H.; Park, H.T.; Lim, S.T.; Park, J.K. Effects of a 12-week healthy-life exercise program on oxidized low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and carotid intima-media thickness in obese elderly women. Journal of Physical Therapy Science 2015, 27, 1435–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joint Committee for Guideline Revision. 2018 Chinese guidelines for prevention and treatment of hypertension-A report of the revision committee of Chinese guidelines for prevention and treatment of hypertension. Journal of Geriatric Cardiology 2019, 16, 182–241. [Google Scholar]

- Korean Society for the Study of Obesity (2020). Guideline for the Management of Obesity 2020.

- Ha, S.M.; Kim, D.Y.; Kim, J.H. Effects of Circuit Exercise on Functional Fitness, Estradiol, Serotonin, Depression and Cognitive Function in Elderly Women. Journal of Korean Physical Education Association for Girls and Women 2017, 31, 199–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American College of Sports Medicine (2018). ACSM`s guidelines for exercise testing and prescription. Lippincott Williams & Willkins.

- Wang, T.T.; Wang, X.M.; Zhang, X.L. Circulating vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM-1): relationship with carotid artery elasticity in patients with impaired glucose regulation (IRG). In Annales d`endocrinologies 2019, 80, 72–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Green, D.J.; Smith, K.J. Effects of exercise on vascular function, structure, and health in humans. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 2018, 8, a029819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossman, M.J.; Kaplon, R.E.; Hill, S.D.; McNamara, M.N.; Santos-Parker, J.R.; Pierce, G.L.; Seals, D.R.; Donato, A.J. Endothelial cell senescence with aging in healthy humans: prevention by habitual exercise and relation to vascular endothelial function. American Journal of Physiology-Heart and Circulatory Physiology 2017, 313, 890–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, D.J.; Hopman, M.T.; Padilla, J.; Laughlin, M.H.; Thijssen, D.H. Vascular adaptation to exercise in human: role of hemodynamic stimuli. Physiology Reviews 2017, 97, 495–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hijmans, J.G.; Bammert, T.D.; Stockelman, K.A.; Reiakvam, W.R.; Greiner, J.J.; DeSouza, C.A. High glucose-induced endothelial microparticles increase adhesion molecule expression on endothelial cells. Diabetology International 2019, 10, 143–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Lv, Y.; Su, Q.; You, Q.; Yu, L. The effect of aerobic exercise on pulse wave velocity in middle-aged and elderly people: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Frontier Cardiovascular Medicine 2022, 9, e960096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeMaster, E.; Huang, R.T.; Zhang, C.; Bohachkov, Y.; Coles, C.; Shentu, T.P.; Sheng, Y.; Fancher, I.S.; Ng, C.; Christoforidis, T.; Subbaiah, P.V.; Berdyshev, E.; Qain, Z.; Eddington, D.T.; Lee, J.; Cho, M.; Fang, Y.; Minshall, R.D.; Levitan, I. Proatherogenic flow increases endothelial stiffness via enhanced CD36-mediated uptake of oxidized low-density lipoproteins. Atherosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 2018, 38, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertani, F.; Di Francesco, D.; Corrado, M.D.; Talmon, M.; Fresu, L.G.; Boccafoschi, F. Paracrine shear stress dependent signaling from endothelial cells affects downstream endothelial function and inflammation. International Journal of Molecular Science 2021, 22, e13300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boeno, F.P.; Ramis, T.R.; Munhoz, S.V.; Farinha, J.B.; Moritz, C.E.; Leal-Menezes, R.; Ribeiro, J.L.; Christou, D.D.; Reischak-Oliveira, A. Effect of aerobic and resistance exercise training on inflammation, endothelial function and ambulatory blood pressure in middle-aged hypertensive patients. Journal of Hypertension 2020, 38, 2501–2509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Variables Group |

Age (yrs) |

Height (cm) |

Weight (kg) |

BMI (kg/m2) |

%BF (%) |

cf-PWV (m/s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VSG (n=14) |

78.64 ±4.55 |

152.39 ±4.71 |

51.48 ±6.70 |

22.13 ±2.12 |

29.26 ±5.56 |

14.77 ±1.94 |

| OG (n=14) |

76.50 ±4.82 |

150.14 ±4.22 |

61.97 ±7.43 |

27.40 ±2.35 |

39.04 ±4.78 |

10.89 ±0.98 |

| NG (n=12) |

78.75 ±5.79 |

147.83 ±6.70 |

48.55 ±7.06 |

22.14 ±2.03 |

30.08 ±6.34 |

9.94 ±1.31 |

| F | 13.331*** | 26.535*** | 13.107*** | 40.581*** | ||

| Scheffe | NS | NS | VSG, NG, <OG |

VSG, NG <OG |

VSG, NG <OG |

OG, NG <VSG |

| Variable | Group | Pre | Post | diff(%) | T | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cf-PWV (m/s) |

VSG (n=14) |

14.77 ±1.94 |

12.61 ±1.73 |

-14.62 | 3.712** | Group | 31.127*** |

| OG (n=14) |

10.89 ±0.98 |

10.88 ±1.30 |

-0.09 | 0.058 | Time | 9.422** | |

| NG (n=12) |

9.94 ±1.31 |

9.93 ±1.40 |

-0.10 | 0.052 | G×T | 9.319*** | |

| F | 40.581*** | 10.983*** | 7.730** | ||||

| Scheffe | OG, NG <VSG |

OG, NG <VSG |

NG<OG <VSG |

||||

| Variable | Group | Pre | Post | diff(%) | t | F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICAM-1 (ng/mL) |

VSG (n=14) |

10.57 ±2.89 |

9.48 ±2.45 |

-10.31 | 3.493** | Group | 0.804 |

| OG (n=14) |

9.92 ±3.69 |

9.62 ±2.75 |

-3.02 | 0.674 | Time | 13.462*** | |

| NG (n=12) |

11.84 ±4.55 |

10.75 ±3.33 |

-9.20 | 2.740* | G×T | 1.404 | |

| F | 0.873 | 0.760 | 2.898 | ||||

| Scheffe | NS | NS | NS | ||||

| VCAM-1 (ng/mL) |

VSG (n=14) |

33.15 ±6.65 |

26.94 ±4.84 |

-18.73 | 5.241*** | Group | 1.745 |

| OG (n=14) |

28.13 ±5.81 |

25.67 ±4.20 |

-8.75 | 2.144 | Time | 28.254*** | |

| NG (n=12) |

29.29 ±3.67 |

28.11 ±2.41 |

-4.03 | 1.659 | G×T | 6.006** | |

| F | 3.060 | 1.197 | 5.115* | ||||

| Scheffe | NS | NS | NG<OG <VSG |

||||

| E-selectin (ng/mL) |

VSG (n=14) |

4.74 ±1.37 |

3.71 ±1.50 |

-21.73 | 4.236*** | Group | 1.258 |

| OG (n=14) |

4.42 ±2.04 |

4.22 ±1.42 |

-4.52 | 0.816 | Time | 11.157** | |

| NG (n=12) |

3.57 ±1.30 |

3.39 ±1.28 |

-5.04 | 0.771 | G×T | 4.052* | |

| F | 1.766 | 1.143 | 5.389** | ||||

| Scheffe | NS | NS | OG<NG <VSG |

||||

| Variable | Group | Pre | Post | diff(%) | t | F | |

| Oxidized-LDL(U/L) | VSG(n=14) | 10.40±3.22 | 7.38±2.99 | -29.04 | 4.145** | Group | 0.235 |

| OG(n=14) | 8.69±3.33 | 8.67±2.87 | -0.23 | 0.027 | Time | 11.895*** | |

| NG(n=12) | 8.32±2.98 | 7.96±2.72 | -4.33 | 0.730 | G×T | 8.740*** | |

| F | 1.630 | 0.712 | 8.920*** | ||||

| Scheffe | NS | NS | OG, NG<VSG | ||||

| Dependent Variable |

B | SE | β | t | F | R2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | -7.723 | 2.110 | -3.660*** | |||

| VCAM-1 | 0.374 | 0.162 | 0.352 | 2.315* | 5.359* | 0.124 |

| Oxidized-LDL | 0.675 | 0.319 | 0.325 | 2.118* | 4.485* | 0.106 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).