1. Introduction

Widely increased availability of the mechanical circulatory/cardiac support systems (MCS), together with the deepening of the knowledge of critical care medical practitioners, have inevitably led to the discussion about further improvements of intensive care associated to MCS. Cardiogenic shock (CS) is one of the main indications for using MCS, both related to acute coronary syndromes, but also to myocarditis, end stage heart failure, postcardiotomy and other etiologies and is associated with significant hospital mortality [

1]. Approach to the treatment of this serious condition has by virtue of MCS undergone dramatical changes during the recent decades. Recent randomized controlled trial [

2] has shown very controversial effect of using VA ECMO in patients suffering cardiogenic from variety of reason, mainly acute myocardial infarction. Definitely, careful consideration and appropriate patient selection remain the mainstay of using this rescue option having in mind considerably deleterious effect of VA ECMO on primarily dysfunctional LV. Thus, another ways to improve the outcome of this desperate patients population are being explored. Mainly, the concept of left-ventricular unloading leads in this area, therefore pathophysiology and rising evidence is about to be discussed in this review.

2. Terminology

Implantation of VA ECMO is followed by a rapid restoration of tissue perfusion, this is obvious from the term mechanical circulatory support. Yet, the term mechanical cardiac support also exists, but it should not be used in the context of VA ECMO, as it provides no augmentation to the left ventricle (LV) function. Therefore, it is more appropriate to save this term for left or right ventricular assist devices (LVAD / RVAD), which are actually able to provide support to myocardial function.

3. Applied physiology

General approach for the implantation of VA ECMO under acute conditions is peripheral, bifemoral (

femoral vein and

artery are used) configuration. Venous cannula is inserted though the inferior vena cava directly to the right atrium, the blood is being drawn into the extracorporeal circuit, flows through the complex of oxygenator and centrifugal pump, to enter the return, arterial cannula, which expels the blood flowretrogradely through the arterial system into the abdominal and thoracic aorta and provides perfusion to tissues and organs [

3,

5].

VA ECMO Generated Circulation and Harlequin Syndrome

Blood-flow generated by VA ECMO is non-physiological. The blood stream is directed against the physiological flow (if any preserved) in the aorta. Thus, two extreme conditions can emerge. If the LV function is maintained to some extent, then there is a meeting (mixing) point of the physiological and ECMO blood stream somewhere in the aortic arch. Thus, if LV function is preserved enough to shift this mixing point distal from the origin of the

left common carotid artery (or

left subclavian artery), a condition called Harlequin syndrome may ensue. Harlequine, or north-south syndrome is reported in 8.8% of cases [

6]. Pathophysiologically, the main issue is, that the blood from the native output of LV may be poorly oxygenated due to concomitant pulmonary dysfunction. On the other hand, ECMO generated blood stream contains highly oxygenated blood. As a result of phenomenon, hypoxia of areas supplied by the branches originating from aortic arch and perfused by native left ventricle output may be observed. This is particularly dangerous considering a possibility of cerebral hypoxic damage [

3,

7]. Not less importantly, myocardium itself is compromised in this situation, as coronary arteries originate from the most proximal part of the aorta [

5]. Owing to these anatomical considerations, myocardium may still suffer of inadequate oxygen delivery. Based on explained hemodynamic principles, monitoring via arterial line for the sampling of blood gases should be placed in the artery of right upper extremity (typically

radial artery). Another possibility to detect hypoxic cerebral perfusion is the use of near-infrared-spectroscopy (NIRS) monitoring, attached to patient´s forehead [

7]. If pulmonary dysfunction is advanced and on the other hand, LV function better than expected, the appropriate solution seems to be adding another returning venous cannula into

internal jugular vein and thus upgrading to the V-AV ECMO to assure adequate oxygenation of the blood leaving the LV.

Left Ventricle Overload

In patients with peripheral VA ECMO, it is not possible to completely drain the blood entering the heart, thus residual basic circulation through the natural pathway still exists. This phenomenon may cause serious clinical issues in an another extreme hemodynamic situation, which will be emphasized in this review. In case of severe LV dysfunction without any effective stroke volume, impaired function of LV is furthermore deteriorated by the increase of afterload caused by the blood stream originating from the ECMO. As a consequence of this, typical hemodynamic pattern may [

4,

5] be seen:

- 1)

increased end-diastolic LV pressure;

- 2)

increased LV wall tension;

- 3)

elevation of pulmonary venous pressure;

- 4)

increased risk of LV thrombosis

In extremis, when the leaflets of aortic valve are not being opened, clinically presented as a non-pulsatile flow, the thrombosis of aortic valve and aortic root may occur. Described alterations in the physiology of the heart may lead to development of pulmonary edema (by increase of pulmonary venous pressure) and worsening of myocardial ischemia (due to the elevation of LV wall tension and end-diastolic pressure). These changes can be summarized in the terms of increased mechanical stress and strain.

Unloading of LV seems to be a reasonable solution to preserve the LV function by decreasing energy demand and possibly, achieve better outcomes. Several modalities were described (

Table 1.) for this purpose [

4,

5,

8]:

- 1)

pharmacological management (maintaining of the appropriate stroke volume by administration of inotropic agents i.e dobutamine, PDE III inhibitors, levosimendan);

- 2)

surgical (vent in the LV/left atrium/pulmonary artery);

- 3)

percutaneous devices (such as Intra-Aortic Baloon Pump - IABP and percutaneous axial flow devices like the Impella family by Abiomed).

Considering surgical approach sternotomy or thoracotomy is usually used to place venting cannula into the pulmonary vein, directly to LV, left atrium, or even pulmonary artery. Obvious disadvantage of these methods is the degree of invasiveness and high risk of bleeding complications.

Therefore, percutaneous methods with limited invasiveness have become most widely used. Nowadays, in 84% of cases LV unloading was provided by percutaneous devices and 16% of cases underwent surgical procedure in order to unload the overdistended LV [

8].

Impella Device – the New Hope for Effective LV Unloading

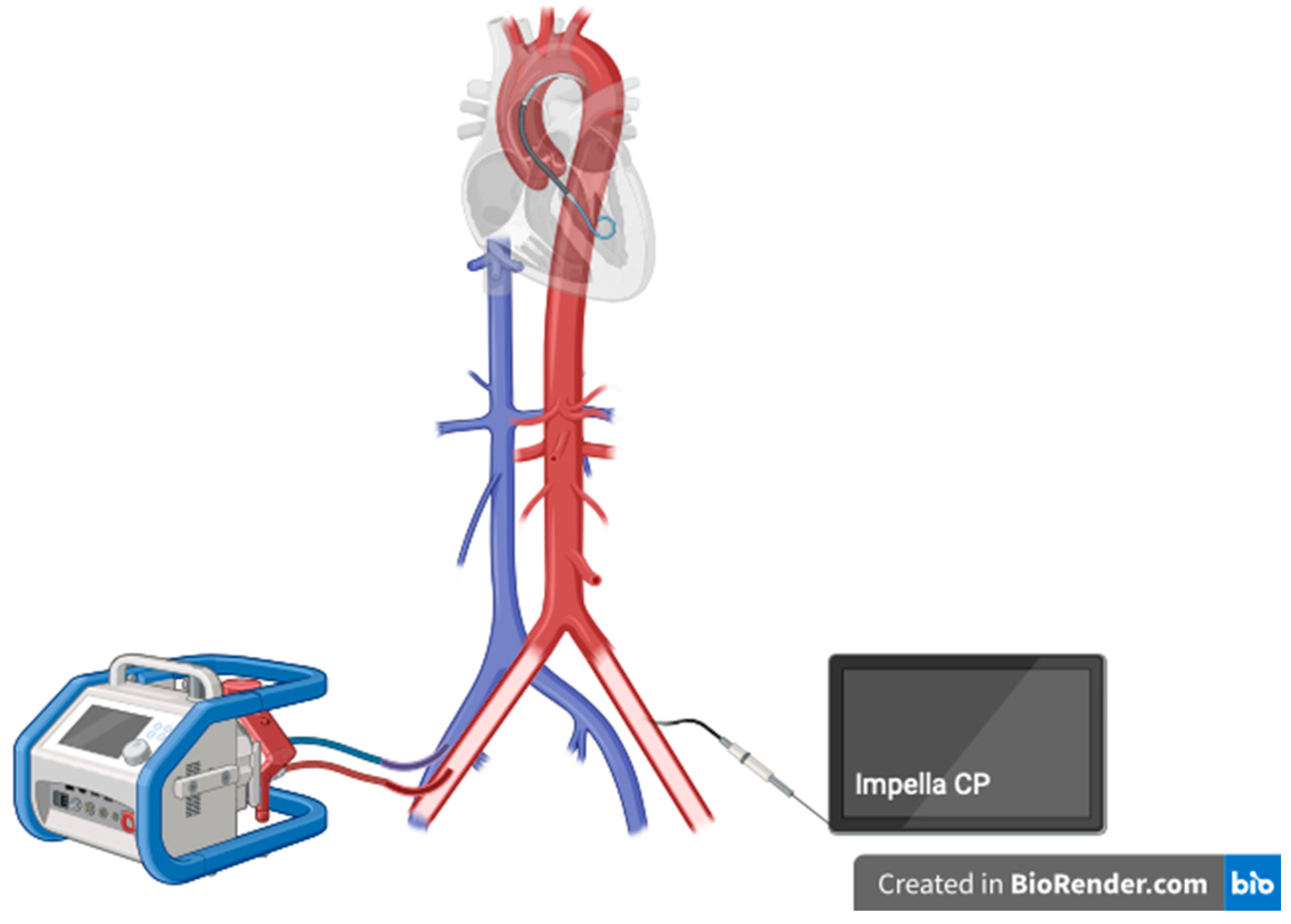

The Impella device is a catheter-based, small measured percutaneous axial flow LVAD, which is able to create a blood flow of up to 2.5 /3.5/ 5.5 L/min depending on particular type of the machine. Impella family currently contains Impella CP, 5.5 and RP (for the right heart support) [9, 10]. Impella CP is implanted via femoral artery, Impella 5.5 requires arteriotomy and a vascular graft.

History of Impella

The origin of the idea, how blood flow is created in Impella leads to the ancient Greece, where Archimedes’s screw was invented (approx. 200-300BC). American physician, Richard Wampler, a father of the reborn idea, developed a predecessor of the Impella in 1985. After years of improvements, in approx. 2000, finally Impella family of devices was revealed [

9].

Why to Unload?

LV overload after VA ECMO implantation puts myocardial recovery in danger. Unloading of the LV leads to the reduction of LV end-diastolic pressure, reduction of pressure in the left atrium and decrease of the LV thrombus formation risk. To conclude, better conditions for myocardial recovery, with comfortable filling pressures and better oxygen delivery/demand ratio is achieved [

11]. Currently, a growing evidence on possible lower mortality associated with the use of Impella device as a modality for the LV unloading in the ECMO patients evolves. The combination of VA ECMO and Impella is usually labeled es ECPELLA or ECMELLA, which is shown in

Scheme 1.

Drawbacks of using Impella are increased risk of bleeding complications, hemolysis and abdominal compartment syndrome [

11]. Notably, the use of ECPELLA brings higher risk of need for renal replacement therapy (RRT) in comparison with VA ECMO alone [

11]. Rational consequence of the ECPELLA configuration is the higher risk of Harlequin syndrome, whereas adding another venous cannula via

internal jugular vein (for return of oxygenated blood) and transformation to V-AV ECMO + Impella should be a solution to the issue [

12].

4. Current Evidence for Using ECPELLA

The pioneers of the new approach – Pappalardo

et al., published in 2017 as the first worldwide a retrospective observational study on 157 patients. The group with ECPELLA showed significantly lower (47% vs. 80%,

p<0.001) in-hospital mortality than patients with VA ECMO only [

13]. A meta-analysis performed by Silvestri

et al. in 2020 included 448 patients in total, showing results with the same trend, the lower mortality of the ECPELLA group (52.6% vs. 63.6%,

p<0.01) against the VA ECMO only [

14].

Recent meta-analysis published by Fiorelli and Panoulas in 2021, included 972 patients, which were divided into the ECPELLA and ECMO only groups. After excluding studies without homogenous comparator group, the combination of Impella with VA ECMO was still associated with lower mortality risk (RR: 0.85; 95% CI: 0.75, 0.97;

p= 0.01). On the other hand, haemolysis (RR: 1.70; 95% CI: 1.35, 2.15;

p < 0.00001) and RRT (RR: 1.86; 95% CI: 1.07, 3.21;

p = 0.03) occurred at a higher rate in the group of patients with ECPELLA. No significant difference was observed in terms of major bleeding complications between the groups RR: 1.37; 95% CI: 0.88, 2.13;

p = 0.16) and cerebrovascular accidents RR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.61, 1.38;

p = 0.66) [

14].

A huge retrospective study performed based on ELSO registry by Grandin

et al. in 2022 showed even wider image of LV unloading. The big data from ELSO registry contained 12,734 patients with VA ECMO (from years 2010-2019), of which 26.7% were upgraded with mechanical unloading device – IABP (in 82.9%) or Impella (in 17.1%). Patients which were finally treated with VA ECMO+IABP / ECPELLA were before VA ECMO cannulation in more serious condition than those, who did not require LV unloading. The LV unloaded patients required >2 vasopressors more frequently (41.7% vs 27.2%) and had respiratory (21.1% vs 15.9%), renal (24.6% vs 15.8%), or liver failure (4.4% vs 3.1%) (all

p< 0.001) before the VA ECMO implantation also more often. But, importantly, in these basically more severely ill patients, lower in-hospital mortality rate was observed (56.6% vs 59.3%,

p = 0.006), which remained lower in a multivariable modeling (adjusted OR [aOR]: 0.84; 95% CI: 0.77-0.92;

p<0.001). What was not significant in this retrospective analysis, is a mortality difference in ECPELLA vs. VA ECMO+IABP group (aOR: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.64-1.01; P = 0.06) [

15].

A large meta-analysis by Russo

et al. (2019) included 3997 patients, of which 42% underwent LV unloading on VA ECMO. The mortality in the group of patients with LV unloading was again significantly lower (54%) in comparison with the group of patients with VA ECMO only (65%). Surprisingly, in this research 91.7% of cases were unloaded with IABP vs 5.5% with Impella [

16]. Despite this, the mortality was lower.

A comprehensive insight was brought into the topic by Schrage

et. al. (2020). This multi-center international cohort study (686 patients), confirmed the other results. The mortality of ECPELLA group subjects was 58.3% (95% CI, 51.6%–64.1%) versus 65.7% (95% CI, 59.2%–71.2%) in ECMO only subjects. Additionally, the analysis of subgroups was performed to explore the role of right timing of LV unloading and initiation. The data showed, that early LV unloading was associated with significantly lower 30-day mortality (HR, 0.76 [95% CI, 0.60–0.97];

p=0.03), but delayed LV unloading (defined as Impella implantation >2hours after VA ECMO implantation) was not associated with better mortality outcome (HR, 0.77 [95% CI, 0.51–1.16];

P=0.22) [

17]. Another light has been brought into the discussion recently by the same team of Schrage et al. (2023). The data of 421 subjects with cardiogenic shock treated with VA-ECMO and active LV unloading at 18 centers were analysed. Early active unloading of LV was initiated in 73.6% of the patients. The results showed, that early unloading of the LV was associated with a lower 30-day mortality risk (HR: 0.64; 95% CI: 0.46-0.88). The same group of patients was characterized with higher chance for successful weaning from ventilation (OR: 2.17; 95% CI: 1.19-3.93) [

18]. Thus, the discussion about ideal timing of LV unloading initiation should be underlined.

5. Conclusion

The ECPELLA approach seems to be a promising strategy which may bring the improvement of CS mortality rates. The series of presented trials and meta-analyses clearly showed potential benefits of this strategy. However, the ongoing research has brought a series of new questions, as whether Impella itself is the only right unloading modality, or any other approach to unload LV would be beneficial in the same way? Furthermore, the discussion about the right timing of the LV unloading initiation was opened. On the other hand, ECPELLA requires additional arterial access and its association with increased rate of bleeding complications and hemolysis are also clearly based on the significant evidence.

Author Contributions

Jan Soltes was responsible for the review of current literature, writing of the draft and conceptualization. Daniel Rob, Petra Kavalkova, Jan Bruthans and Jan Belohlavek reviewed and edited the draft. Prof. Jan Belohlavek acted also as main supervisor of the process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- ECMO Registry of the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization (ELSO), Ann Arbor, Michigan, 2022.

- Ostadal P, Rokyta R, Karasek J, Kruger A, Vondrakova D, Janotka M, Naar J, Smalcova J, Hubatova M, Hromadka M, Volovar S, Seyfrydova M, Jarkovsky J, Svoboda M, Linhart A, Belohlavek J; ECMO-CS Investigators. Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in the Therapy of Cardiogenic Shock: Results of the ECMO-CS Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation. 2023 Feb 7;147(6):454-464. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Sibai, R., Bachir, R. & El Sayed, M. ECMO use and mortality in adult patients with cardiogenic shock: a retrospective observational study in U.S. hospitals. BMC Emerg Med 18, 20 (2018). [CrossRef]

- Atti V, Narayanan MA, Patel B, Balla S, Siddique A, Lundgren S, Velagapudi P. A Comprehensive Review of Mechanical Circulatory Support Devices. Heart Int. 2022 Mar 4;16(1):37-48. [CrossRef]

- Belohlavek J, Hunziker P, Donker DW. Left ventricular unloading and the role of ECpella. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2021 Mar 27;23(Suppl A):A27-A34. [CrossRef]

- Rupprecht L, Lunz D, Philipp A, Lubnow M, Schmid C. Pitfalls in percutaneous ECMO cannulation. Heart Lung Vessel. 2015;7(4):320-6.

- Hogue CW, Levine A, Hudson A, Lewis C. Clinical Applications of Near-infrared Spectroscopy Monitoring in Cardiovascular Surgery. Anesthesiology. 2021 ;134(5):784-791. 1 May. [CrossRef]

- Meani P, Gelsomino S, Natour E, Johnson DM, Rocca HB, Pappalardo F, Bidar E, Makhoul M, Raffa G, Heuts S, Lozekoot P, Kats S, Sluijpers N, Schreurs R, Delnoij T, Montalti A, Sels JW, van de Poll M, Roekaerts P, Poels T, Korver E, Babar Z, Maessen J, Lorusso R. Modalities and Effects of Left Ventricle Unloading on Extracorporeal Life support: a Review of the Current Literature. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017 May;19 Suppl 2:84-91. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Fares AA, Randhawa VK, Englesakis M, McDonald MA, Nagpal AD, Estep JD, Soltesz EG, Fan E. Optimal Strategy and Timing of Left Ventricular Venting During Veno-Arterial Extracorporeal Life Support for Adults in Cardiogenic Shock: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Circ Heart Fail. 2019 Nov;12(11):e006486. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Glazier JJ, Kaki A. The Impella Device: Historical Background, Clinical Applications and Future Directions. Int J Angiol. 2019 Jun;28(2):118-123. [CrossRef]

- Meani P, Lorusso R, Pappalardo F. ECPella: Concept, Physiology and Clinical Applications. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2022 Feb;36(2):557-566. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giunta M, Recchia EG, Capuano P, Toscano A, Attisani M, Rinaldi M, Brazzi L. Management of harlequin syndrome under ECPELLA support: A report of two cases and a proposed approach. Ann Card Anaesth. 2023 Jan-Mar;26(1):97-101. [CrossRef]

- Pappalardo F, Schulte C, Pieri M, Schrage B, Contri R, Soeffker G, Greco T, Lembo R, Müllerleile K, Colombo A, Sydow K, De Bonis M, Wagner F, Reichenspurner H, Blankenberg S, Zangrillo A, Westermann D. Concomitant implantation of Impella® on top of veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation may improve survival of patients with cardiogenic shock. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017 Mar;19(3):404-412. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiorelli F, Panoulas V. Impella as unloading strategy during VA-ECMO: systematic review and meta-analysis. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2021 Dec 22;22(4):1503-1511. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grandin EW, Nunez JI, Willar B, Kennedy K, Rycus P, Tonna JE, Kapur NK, Shaefi S, Garan AR. Mechanical Left Ventricular Unloading in Patients Undergoing Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2022 Apr 5;79(13):1239-1250. [CrossRef]

- Russo JJ, Aleksova N, Pitcher I, Couture E, Parlow S, Faraz M, Visintini S, Simard T, Di Santo P, Mathew R, So DY, Takeda K, Garan AR, Karmpaliotis D, Takayama H, Kirtane AJ, Hibbert B. Left Ventricular Unloading During Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in Patients With Cardiogenic Shock. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019 Feb 19;73(6):654-662. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schrage B, Becher PM, Bernhardt A, Bezerra H, Blankenberg S, Brunner S, Colson P, Cudemus Deseda G, Dabboura S, Eckner D, Eden M, Eitel I, Frank D, Frey N, Funamoto M, Goßling A, Graf T, Hagl C, Kirchhof P, Kupka D, Landmesser U, Lipinski J, Lopes M, Majunke N, Maniuc O, McGrath D, Möbius-Winkler S, Morrow DA, Mourad M, Noel C, Nordbeck P, Orban M, Pappalardo F, Patel SM, Pauschinger M, Pazzanese V, Reichenspurner H, Sandri M, Schulze PC, H G Schwinger R, Sinning JM, Aksoy A, Skurk C, Szczanowicz L, Thiele H, Tietz F, Varshney A, Wechsler L, Westermann D. Left Ventricular Unloading Is Associated With Lower Mortality in Patients With Cardiogenic Shock Treated With Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: Results From an International, Multicenter Cohort Study. Circulation. 2020 Dec;142(22):2095-2106. [CrossRef]

- Schrage B, Sundermeyer J, Blankenberg S, Colson P, Eckner D, Eden M, Eitel I, Frank D, Frey N, Graf T, Kirchhof P, Kupka D, Landmesser U, Linke A, Majunke N, Mangner N, Maniuc O, Mierke J, Möbius-Winkler S, Morrow DA, Mourad M, Nordbeck P, Orban M, Pappalardo F, Patel SM, Pauschinger M, Pazzanese V, Radakovic D, Schulze PC, Scherer C, Schwinger RHG, Skurk C, Thiele H, Varshney A, Wechsler L, Westermann D. Timing of Active Left Ventricular Unloading in Patients on Venoarterial Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Therapy. JACC Heart Fail. 2023 Mar;11(3):321-330. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Scheme 1.

ECPELLA configuration for LV unloading.

Scheme 1.

ECPELLA configuration for LV unloading.

Table 1.

Different modalities of LV unloading (based on Belohlavek et al. [

7] and Meani et al. [

10]; LA = left atrium, PA = pulmonary artery, LV = left ventricle).

Table 1.

Different modalities of LV unloading (based on Belohlavek et al. [

7] and Meani et al. [

10]; LA = left atrium, PA = pulmonary artery, LV = left ventricle).

| Location - Device |

Access |

Output (max) |

| LA - vent |

surgical |

undetermined |

| LA - vent |

percutaneous, transseptal |

undetermined |

| Atrial septostomy |

percutaneous |

undetermined |

| PA - vent |

percutaneous/surgical |

undetermined |

| LV - vent |

surgical |

undetermined |

| LV-Impella 2.5/CP |

percutaneous |

2.5 / 3.7 L/min |

| LV-Impella 5.0/5.5 |

surgical |

5.0 / 5.5 L/min |

| Aorta - IABP |

percutaneous |

|

| LA -TandemHeart |

percutaneous |

5L/min |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).