Submitted:

22 August 2023

Posted:

24 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

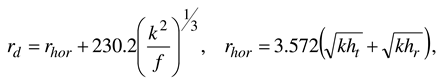

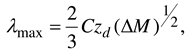

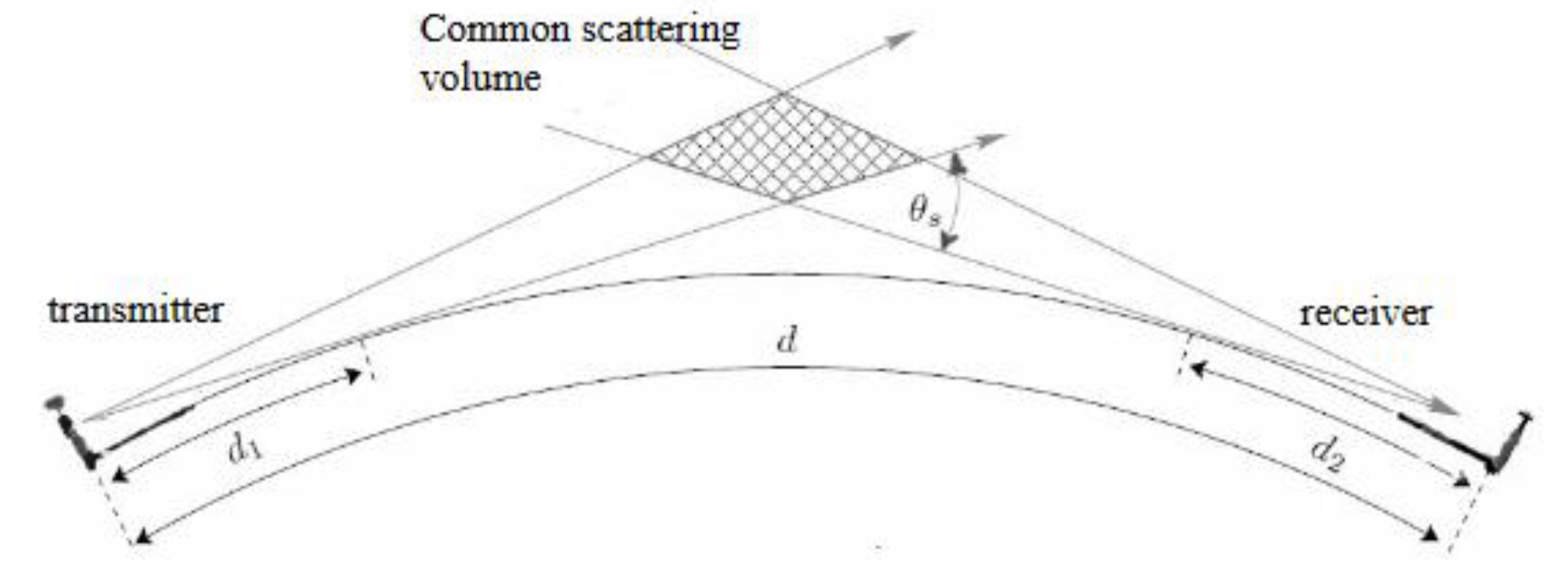

2. Theoretical background

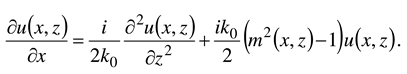

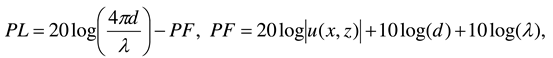

2.1. Description of the PE Method

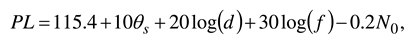

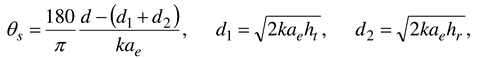

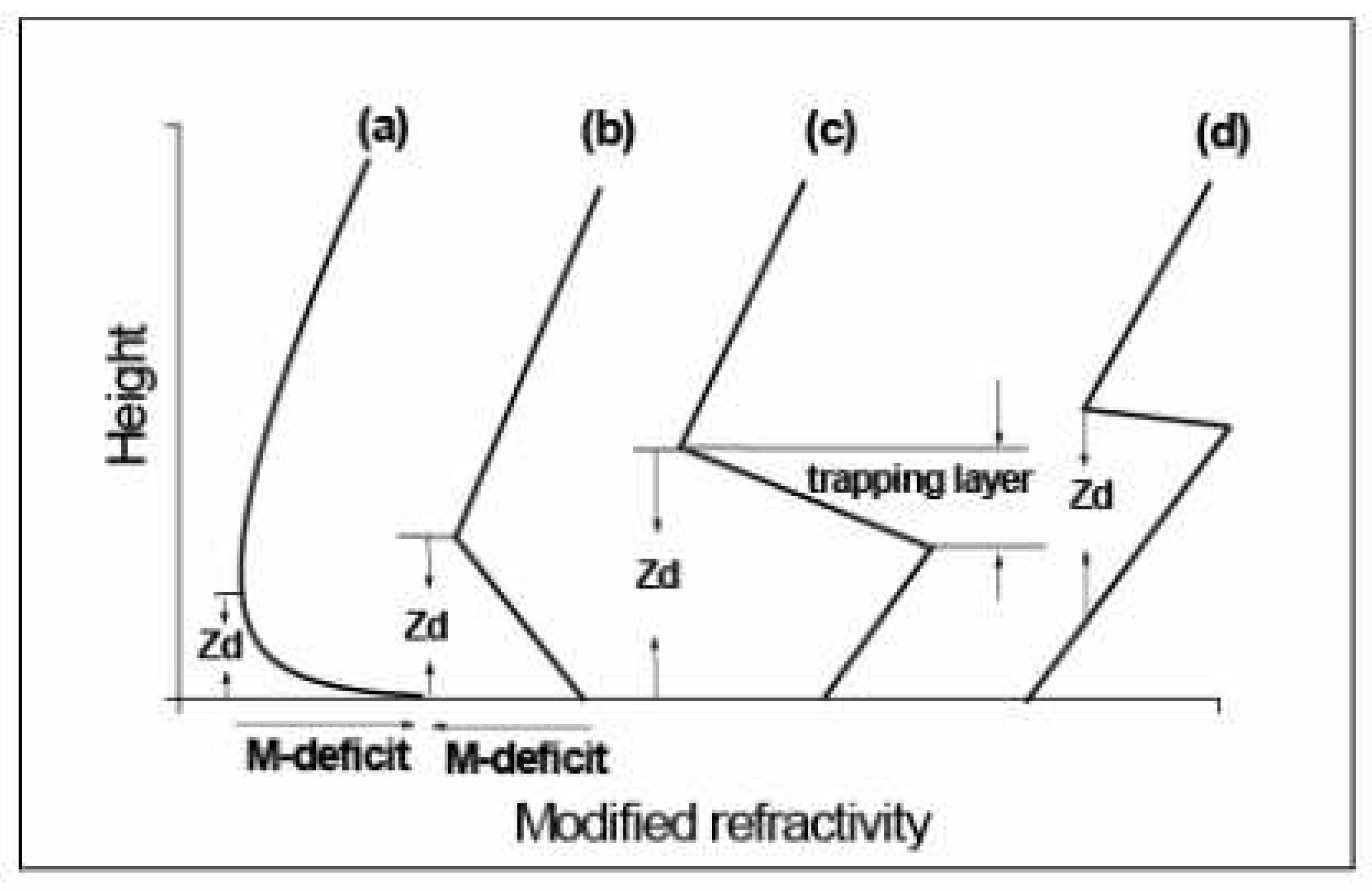

2.2. Troposcatter model

3. Results and discussion

4. Conclusion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- International Telecommunication Union. R-REC-M.2092-1: Technical characteristics for a VHF data exchange system in the VHF maritime mobile band; Electronic Publication: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022.

- Jiang, S. Networking in ocean: a survey. ACM Computing Surveys 2022, 54, 13:1-13:33.

- Wright, D.; Janzen, C.; Bochenek, R.; Austin, J.; Page, E. Marine Observing applications using AIS: Automatic Identification System. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6. [CrossRef]

- Emmens, T.; Amrit, C.; Abdi, A.; Ghosh, M. The promises and perils of Automatic Identification System data. Expert Sys. Appl. 2021, 178. [CrossRef]

- International Telecommunication Union. ITU-R M.2123: Long range detection of automatic identification system (AIS) messages under various tropospheric propagation conditions; ITU: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007.

- Dinc, E.; Akan, O. B. Beyond-line-of-sight communications with ducting layer. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2014, 52, 37–43. [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Cha, H.; Wei, M.; Tian. B. Estimation of surface-based duct parameters from automatic identification system using the Levy flight quantum-behaved particle swarm optimization algorithm. JEWA 2019, 33, 827-837. [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Cha, H.; Wei, M.; Tian, B.; Li, Y. A Study on the Propagation Characteristics of AIS Signals in the Evaporation Duct Environment. ACES Journal 2019, 34, 996-1001.

- Robinson, L.; Newe, T.; Burke, J.; Toal, D. A simulated and experimental analysis of evaporation duct effects on microwave communications in the Irish Sea. IEEE Trans. on AP 2022, 70, 4728–4737. [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Wang, S.; Yang, F.; Yang, K. Statistical analysis of hybrid atmospheric ducts over the Northern South China sea and their influence on over-the-horizon electromagnetic wave propagation. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 669. [CrossRef]

- Bastos, L.; Wietgrefe, H. A Geographical analysis of highly deployable troposcatter systems performance. In Proceeding of the 2013 IEEE Military Communications Conference, San Diego, CA, USA, 18-20 November 2013; pp. 661-667. [CrossRef]

- Propagation of Short Radio Waves, 2nd ed.; Kerr, D.E., Ed.; Peter Peregrinus: London, UK, 1987.

- Paulus, R.A. Practical application of an evaporation duct model. Radio Sci. 1985, 20, 887–896. [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Shi, Y.; Wang J.; Feng, F. Regional spatiotemporal statistical database of evaporation ducts over the South China Sea for future long-range radio application. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2022, 15, 6432-6444. [CrossRef]

- Yang, N.; Su, D.; Wang, T. Atmospheric ducts and their electromagnetic propagation characteristics in the Northwestern South China Sea. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3317. [CrossRef]

- Rautiainen, L.; Tyynelä, J.; Lensu, M.; Siiriä, S.; Vakkari, V.; O’Connor, E.; Hämäläinen, K.; Lonka, H.; Stenbäck, K.; Koistinen, J.; et al. Utö observatory for analysing atmospheric ducting events over Baltic coastal and marine waters. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2989. [CrossRef]

- von Engeln A.; Teixeira J., A ducting climatology derived from ECMWF global analysis fields. J Geophys. Res. 2004, 109. doi:10.1029/2003JD004380.

- Yang, C.; Wang, J. The investigation of cooperation diversity for communication exploiting evaporation ducts in the South China Sea. IEEE Trans. on AP 2022, 70, 8337-8347. [CrossRef]

- Zaidi, K.S.; Hina, S.; Jawad M.; Khan, A.N.; Khan, M.U.S.; Pervaiz, H.B.; Nawaz, R. Beyond the horizon, backhaul connectivity for offshore IoT devices. Energies 2021, 14, 6918. [CrossRef]

- Ma, J; Wang, J.; Yang, C. Long-range microwave links guided by evaporation ducts. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2022, 60, 68-72. [CrossRef]

- Sirkova, I. Anomalous tropospheric propagation: usage possibilities and limitations in radar and wireless communications systems. In: Proceedings of the 10th Jubilee International Conference of the Balkan Physical Union, Sofia, Bulgaria, 26-30 August, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Valčić, S.; Brčić, D. On detection of anomalous VHF propagation over the Adriatic Sea utilizing a software-defined Automatic Identification System receiver. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2023, 11, 1170. [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.-F.; Liu, C.-G.; Wu, Z.-P.; Zhang, L.-J.; Wang, H.-G.; Zhu, Q.-L.; Han, J.; Sun, M.-C. Comparative analysis of intelligent optimization algorithms for atmospheric duct inversion using Automatic Identification System signals", Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 3577. [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Wu, J.; Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Zhu, Q.; Zhang, C.; Zhao, H.; Zhang, S. A Classifying-inversion method of offshore atmospheric duct parameters using AIS data based on artificial intelligence. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3197. [CrossRef]

- Yeh, L. Simple methods for designing troposcatter circuits. IRE Trans. Commun. Syst. 1960, 8, 193-198. [CrossRef]

- Rice, P.L.; Longley, A.G.; Norton, K.A.; Barsis, A.P. Transmission Loss Predictions for Tropospheric Communication Circuits; Department of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards: Maryland, US, 1965.

- International Radio Consultative Committee. Recommendations and Reports of the CCIR: Propagation in non-ionized media; CCIR: Geneva, Switzerland, 1986.

- International Telecommunication Union. Recommendation ITU-R P.452-16: Prediction procedure for the evaluation of interference between stations on the surface of the Earth at frequencies above about 0.1 GHz; Electronic Publication: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015.

- International Telecommunication Union. Recommendation ITU-R P.617-2: Propagation prediction techniques and data required for the design of trans-horizon radio-relay systems; Electronic Publication: Geneva, Switzerland, 2012.

- International Telecommunication Union. Recommendation ITU-R P.2001-3: A general purpose wide-range terrestrial propagation model in the frequency range 30 MHz to 50 GHz; Electronic Publication: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Li, L.; Wu, Z.-S.; Lin, L.-K.; Zhang, R.; Zhao, Z.-W. Study on the prediction of troposcatter transmission loss. IEEE Trans. on AP 2016, 64, 1071-1079. [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Chen, X. Troposcatter transmission loss prediction based on particle swarm optimization. IET Microw. 2021, 15, 332-341. [CrossRef]

- Lee, I.-S.; Noh, J.-H.; Oh, S.-J. A Survey and analysis on a troposcatter propagation model based on ITU-R recommendations. ICT Express 2023, 9, 507-516. [CrossRef]

- Levy, M. Parabolic Equation Methods for Electromagnetic Wave Propagation; IEE: London, UK, 2000.

- Kuttler, J.R.; Dockery, G.D. Theoretical description of the parabolic approximation Fourier split-step method of representing electromagnetic propagation in the troposphere. Radio Sci. 1991, 26, 381–393. [CrossRef]

- Apaydin, G.; Sevgi, L. Radio Wave Propagation and Parabolic Equation Modeling; Wiley-IEEE Press: Hoboken, New Jersey, US, 2017.

- Sirkova, I. Brief review on PE method application to propagation channel modeling in sea environment. CEJE 2012, 2, 19-38. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Bai, L.; Wu, Z.; Guo, L. Applying the parabolic equation to tropospheric groundwave propagation: a review of recent achievements and significant milestones. IEEE Antennas Propag. Mag. 2016, 58, 31–44. [CrossRef]

- Apaydin, G.; Sevgi, L. The split-step-Fourier and finite-element based parabolic-equation propagation prediction tools: canonical tests, systematic comparisons, and calibration. IEEE Antennas Propag. Mag. 2010, 52, 66–79. [CrossRef]

- Barrios, A.E.; Anderson, K.; Lindem, G. Low altitude propagation effects - a validation study of the Advanced Propagation Model (APM) for mobile radio applications. IEEE Trans. on AP 2006, 54, 2869-2877. [CrossRef]

- Gunashekar, S.D.; Warrington, E.M.; Siddle D.R.; Valtr P. Signal strength variations at 2 GHz for three sea paths in the British Channel islands: detailed discussion and propagation modeling. Radio Sci. 2007, 42, doi:10.1029/2006RS003617.

- Heemskerk, E. RF propagation measurement and model validation during RF/IR synergy trial VAMPIRA. In: Proceedings of SPIE Remote Sensing: Optics in atmospheric propagation and adaptive systems VIII, Bruges, Belgium, 20-21 September 2005; pp. 598107.1-598107.12. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Alappattu, D.P.; Billingsley, S.; Blomquist, B.; Burkholder, R.J. et al. CASPER: coupled air-sea process and electromagnetic wave ducting research. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc. 2018, 99, 1449–1471. [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhou, H.; Li, Y.; Sun, Q.; Wu, Y.; Jin, S.; Quek, T.Q.S.; Xu, C. Wireless channel models for maritime communications. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 68070-68088. [CrossRef]

- Barrios, A. E. Considerations in the development of the advanced propagation model (APM) for U.S. navy applications. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Radar (IEEE Cat. No.03EX695), Adelaide, SA, Australia, 3-5 September 2003; pp. 77-82. [CrossRef]

- Sirkova, I. Duct occurrence and characteristics for Bulgarian Black sea shore derived from ECMWF data. J. Atmos. Sol-Terr. PHy. 2015, 135, 107-117. [CrossRef]

- Reed, H.R.; Russell, C.M. Ultra high frequency propagation; Boston Technical Publishers: Cambridge, US, 1966.

- Hitney, H.V. A practical tropospheric scatter model using the parabolic equation. IEEE Trans. on AP 1993, 41, 905-909. [CrossRef]

- Turton, J.D.; Bennetts, D.A.; Farmer, S.F.G. An introduction to radio ducting. Meterorolog. Mag. 1988, 117, 245-254.

- Rol, M.; Nijboer, R.; Yarovoy, A. Radio wave blind zone in a duct: an analytical approach. In Proceeding of the 24th International Microwave and Radar Conference (MIKON), Gdansk, Poland, 12-14 September, 2022; pp. 1-6. [CrossRef]

- D. Couillard, G. Dahman, M. GrandMaison, G. Poitau and F. Gagnon, Robust broadband maritime communications: theoretical and experimental validation. Radio Sci. 2018, 53, 749-760. [CrossRef]

- Sirkova, I. Automatic Identification System Signals propagation in troposphere ducting conditions. In Proceedings of the 10th IEEE International Black Sea Conference on Communications and Networking (BlackSeaCom), 6-9 June 2022, Sofia, Bulgaria; pp. 331-335. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).