1. Introduction

Mountains can be described as a socio-ecological systems (SES), a complex set of relations and connections involving not only natural aspects but also human communities with their culture and economic activities strictly related on the local environment conditions [

1]. Mountain SESs are relevant because they provide a wide range of valuable ecosystem services indispensable to life. They play a crucial role in freshwater supply, oxygen generation and carbon storage. They are also home to an extensive variety of flora and fauna species, many of which are specific to these areas and for this, they preserve biodiversity. These SESs also offer recreation and leisure opportunities and food specialities that characterize local and national cultural heritage. All those elements could be strategic resources for local actors in market competition; the peculiar environment and distinctive processing conditions make mountain foods special high-quality goods [

2], while mountain landscapes and nature are relevant in tourist attraction [

3]. In short, mountains have a pivotal role in ecological balance and have several resources profitable in production processes and services delivery.

In the case of European Union, these areas cover nearly 30% of its surface and are home to almost 17% of its population [

4], which has an important part of the socio-ecological system contributing to ensuring the precious rule of mountains. Forests regenerate air and play a key role in wood, chestnut, and honey value chains, as well as permanent grasslands and meadows preserve biodiversity and are pivotal for breeding activities relate to dairy and meat value chains. However, these resources need forms of maintenance to avoid their depletion by natural causes (e.g., fire, the spread of invasive alien vegetables and wildlife) or over-exploitation. Nevertheless, mountains are fragile areas affected mainly by two problems: depopulation and the climate change. On the one hand, the population decrease is a long-standing occurrence that is reducing the human presence in these areas affecting not only mountain agricultural productions but also the ecological balance of mountains [5; 6]. On the other hand, climate change is a quite recent event that is redefining temperature and rainfall regimes with consequences on vegetative cycles of plants – influencing for example agricultural productions – the health of livestock, wildlife, and pollinating insects. For this reason, climate change is also a push factor that increases the depopulation trend, accelerating the damage of the socio-ecological systems with significant consequences in the mountains but also in valleys and cities [7; 8].

In short, global warming is a driver of change and several research focuses on the way mountain communities try to face climate change or how they perceive the risk and natural hazards related to global warming that tends to worsen the conditions related to the dynamics of depopulation [9; 10]. These studies report which actions communities put into practice or which policies should be set both to face the effects and to contrast climate change. Understanding how local people perceive and react to the climate change vulnerability seems worthy to analyse for two reasons: 1) to increase the resilience of these communities and 2) to promote appropriate policies. In this sense, farmers' perceptions and expertise should be integrated into discussions to define land management and climate change adaptation in mountains. Yet, as observed [

11], with some exceptions, policies and research seem to not substantively embrace farmers' perceptions as contributing to adaptation discourse, generally because farmers are considered mainly passive and vulnerable actors rather than viably reacting to challenges. It appears that farmers’ agency capacities, as an effect of situated social relations [12; 13], are not taken into consideration in the adaptive policies. The gap between policymakers, researchers and local actors can affect the possibility to effectively face the climate change. They have different epistemic cultures and social values that need to be linked to deal climate change challenges.

In this paper we want to test the working hypothesis that mountain actors constantly face the SES’s climate change vulnerability and identify or practise suitable solutions in the specific situated condition within which they are embedded (in natural, cultural and market contexts) and constrained. The idea is that they act a localized agency capacity combining a large set of elements (values, expectations, natural settings, and resources, etc.) as some studies seem to suggest [10; 12; 14; 15]. At the same time, these actions may have limited effectiveness due to their perception/experience of climate change, as to say, their epistemology. They would need more extensive scientific knowledge and larger experiences of climate risks to forecast future conditions and identify new solutions that could involve academia and policymakers. In this sense, an epistemology dialogue between lays and experts could be effective to face climate change.

To test this hypothesis, here we investigate the climate change vulnerability by mountain actors focusing on the case of dairy value chain in the North of the Italian region of Molise, called “Alto Molise”, between of Central and Southern Apennines in Italy. Based on data collected in the first research step of project MOVING (“

MOuntain Valorisation through INterconnectedness and Green growth” is a Horizon 2020 project coordinated by the University of Cordoba, more detail here:

https://www.moving-h2020.eu/), we describe the perception/experience of climate change vulnerability according to local actors and resilience actions that local stakeholders related to the main local value chains can identify and enact. In this sense, we investigate their agency capacity, their “lay” epistemology and the way to influence and be influenced by experts’ knowledge.

Following, we report the research framework (paragraph 2) and methodology (paragraph 3, see also acknowledgments), then the description of the case study area (paragraph 4). The main outcomes are in two sections: the perception of climate change vulnerability (paragraph 5) and the actors’ reactions and proposed policies (paragraph 6). The conclusion reports a critical discussion on research outcomes.

2. Agency, epistemology, and climate uncertainties

As report Regubini [

16], agency is a familiar and widespread term in social science, but it recalls a variety of theoretical approaches and meanings. It is a polymorphic concept that could refer to individual’s capacity for decision-making, to define performativity of practices, or it is association with actors' self-reflexivity. Thus using agency as a conceptual category can be problematic and it needs to clarify the boundaries encompassing the concept . In our contribution we refer to a specific idea of agency that lies in the so called “material turn” that took place in social science to study the interaction between human societies and the material world.

Despite criticism on this perspective [

17], it overcomes the realism/constructionism diatribe understanding knowledge and materiality as mutually constituted and constantly reshaped. In this perspective, agency is not an individual attribute or the power of social actors, but a practice that emerges at the interconnections of distributed “enact capacity” of human and nonhuman entities embedded in a specific socio-ecological-technical configuration. In this sense, know-how and internalized dispositions of social actors can change according to the environment, the context normativity, and according to more suitable aims and goals of who is acting. In this sense, Bruno Latour [

18], and the Actor-Network Theory (ANT), considers critical capacities of the agency based on learning experiences and the possibility to innovate by starting from the objects of the environment.

In short, in this approach, agency – as to say, everyday actions, resistance or creativity in social change – is not the effect of the subject intentional actions or consequences of linked events. The agency is understood as a localized practice related to how individuals are embedded in an ongoing engagement in the world. In other words, agency takes place in contextual, dynamic, and temporal forms of activity where cognitive and material aspects cannot be separated. Moreover, the experience of the world is specific, and, in this sense, it defines subjects’ epistemologies and several actors, because of their specific world experiences and relations, have their epistemology. In fact, considering what suggest Pierre Bourdieu [

19], in any social field, actors play a specific role knowing the game rules, but they capital resources (social, economic, and cultural one) define their opportunity to move and act. In this sense, their agency is also affected by the way they can experiment and understand the world that depends on their positions and resources. For this, we should take in consideration what Castree, referring to the ANT, called “weak version” of this perspective, because the agency is:

«social and natural but not in equal measure, since it is the ‘social’ relations that are often disproportionately directive; that agents, while social, natural and relational, vary greatly in their powers to influence others; and that power, while dispersed, can be directed by some (namely, specific ‘social’ actors) more than others» [20, p. 135].

The theoretical framework here outline is adopted in our work as a set of “sensitizing concepts” [

21], giving a general reference and guidance in empirical research by merely suggesting directions to look. Sensitizing concepts draw attention to essential features of social interaction and provide guidelines for research in specific settings. In our case, the focus is on the main value chain in a specific mountain socio-ecological system considering climate change and resilience actions. As it was reported [

22], value chains are a useful point of analysis to inquire human-natural interactions because they mobilize resources and connect actants beyond territorial boundaries and economic sectors to generate socioeconomic and environmental values. Specifically, adopting the theoretical viewpoint here outline, research aims to contribute to understand resilience actions and initiative against climate uncertainties [23; 24; 25] considering different mountain stakeholders’ agency and epistemologies, specifically farmers and experts, and how to connect them for effective climate actions preserving mountain socio-ecological systems.

3. Method and database

To explore the perception and experiences of global warming by mountain local actors, we use data collected in the first step of MOVING project (see acknowledgments). In that stage, the focus was on evaluating the susceptibility and vulnerability of the socio-ecological system to specific drivers of change, like climate change, according to local stakeholders. Moreover, we investigated adaptive mechanisms for resilience enacted by them. The “susceptibility” estimates if an element (e.g., extreme events) can affect the SES, while the “vulnerability” indicates how large the SES can be affected by some drives of change (

Table 1). In our case, we aimed to identify which specific “reference variable” of the SES (the critical resource that influences and makes the local value chains possible) is recognised by local actors, which elements affect it and what kind of actions they enact to face drives of change. Then, to investigate these aspects, we adopted a participatory approach and collected information were compared and put in dialogue with experts and scientific knowledge on the same issue.

To accomplish research steps, two preliminary aspects needed to outline: the investigation area and the local value chain to consider. On previous studies and the expertise of the research team [

26] were identified a set of five contiguous Municipalities – Agnone, Capracotta, Carovilli, Pescolanciano and Vastogirardi (see paragraph 4) – in the mountain area of Alto Molise where prevail the agro-sylvo-pastoral land-use. In this zone, the dairy value chain is prominent and the Caciocavallo cheese is a pivotal element of the territorial identity and local economy. To identify and involve stakeholders in the participatory research approach, the Mayor of Agnone was a relevant gatekeeper allowing researchers to overcome local actors’ mistrust and increasing their interest in the research. A first set of 10 crucial stakeholders were identified considering some of their features (age, gender, expertise, etc.) that was enlarged up to 44 actors during the research activities (

Table 2).

As it noted [

27] the actors' involvement in the research stages has some advantages. First, it helps identify and assess aspects that are difficult to define in advance by researchers and considered relevant by subjects involved (e.g., the choice of the variables set to analyse). Second, it allows to grab the actors' viewpoint on the functioning of the socio-ecological systems, especially aspects relate to the sustainability and resilience dimensions. To take advantage to stakeholders’ engagement, we interviewed and invited them to validate research data and considerations emerged in the study through four actions:

Elaborating data collected in the research steps, we obtain a plausible stakeholder viewpoint on their perception and experience of climate change impacts on the local value chain. Comparing these data with scientific evidence and elaborations helped us to understand differences on lay and expert epistemologies in a specific context also useful to promote appropriate resilience policies.

4. The context of Alto Molise

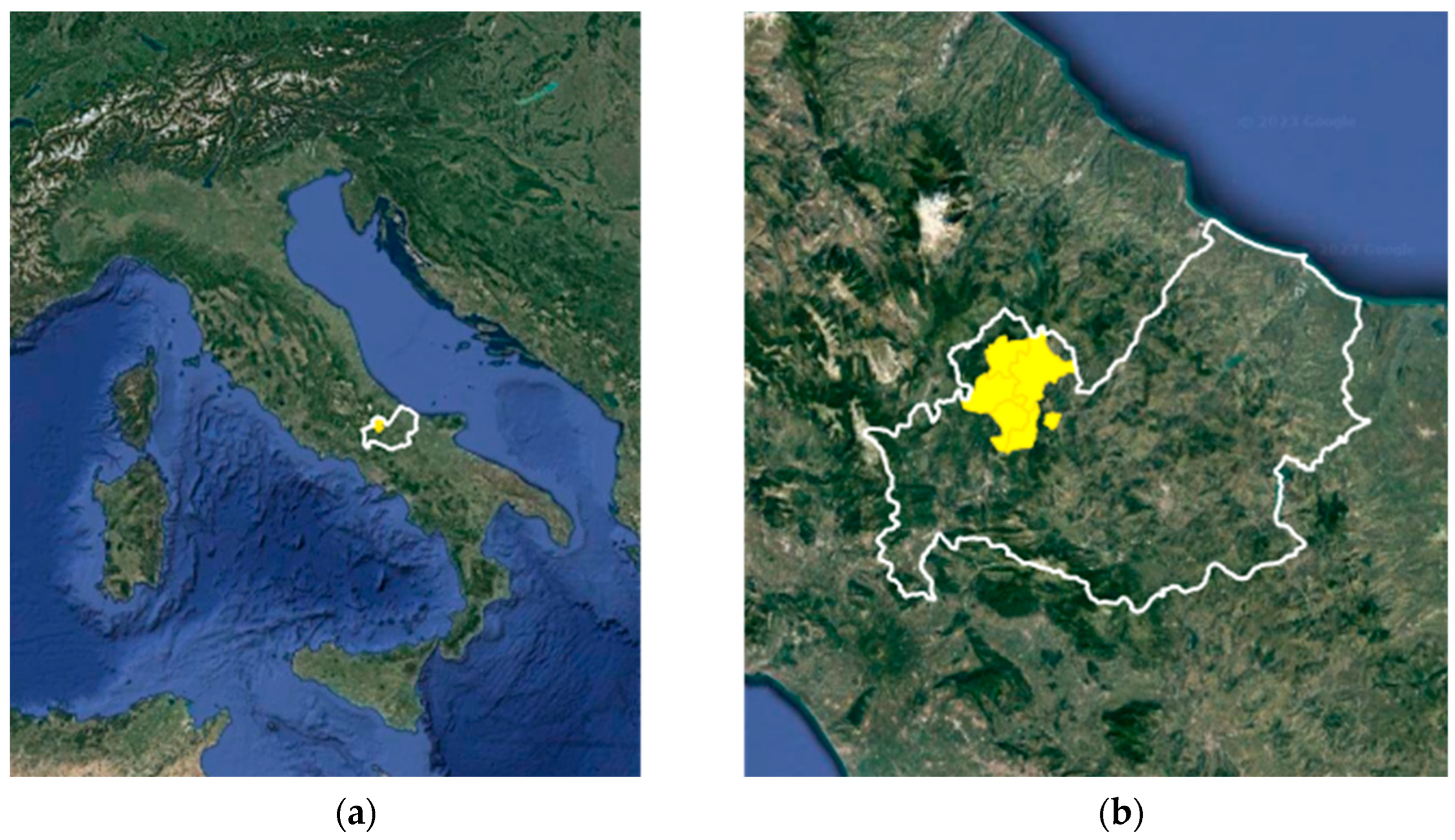

To specify the research outcome seems useful to describe the area where the research was carried out reporting the SES’ peculiarities and scientific information on the plausible effects of climate change to some relevant elements (e.g., droughts, average temperatures, etc.). As it was reported in the paragraph 3, the area of Alto Molise lies in a specific Southern zone of Central Apennines in Italy and our research investigates the context enclosed within the borders of 5 specific municipalities: Agnone, Capracotta, Carovilli, Pescolanciano and Vastogirardi (

Figure 1). These towns are geographically contiguous, with a similar mountain ecological setting and prevail the dairy value chain and collateral activities like tourism. The area neatly depicts the socio-ecological system of Alto Molise. Following the features of the area are reported.

4.1. Features of the socio-ecological system

The Southern zone of Central Apennines consists of a hilly-mountainous structure with a few valleys close to rivers and streams. Several natural areas are in the most extreme Southern zone of it, which extends over the Northern of the Molise region, the “Alto Molise”. Alto Molise has a rich biodiversity, and some tree species here located are considered rare, like the Apennines white fir woods. This remarkable ecological aspect is also confirmed by the fact that since 1977 here is located the solely UNESCO biodiversity reserve in the Central Apennines: the Collemeluccio-Montedimezzo reserve.

The context is characterized by extensive pastures and wooded areas involved in the mountain economy, such as livestock productions (cheese and meat) and forestry-related ones (wood, honey, and truffles). There is also a tradition of craftsmanship rooted on the local food, confectionary and metalworking tradition. A special mention deserves the Marinelli Pontifical Foundry, an ancient family factory of bells that run for the last 1000 years [

28].

In Alto-Molise dairy production in mountain pastures is a peculiar traditional activity developed in centuries and the Caciocavallo cheese (of stretched-curd cheese made of cow’s milk

), is a symbol of the area and one of the main food products. To perform the local dairy value chain several natural elements and human practices need to be involved: the land-use system (meadows and pastures and their peculiar vegetable species), cattle breeding activities (cattle species, breeding systems and practices) and the cheese production process (milk, microorganism, cheesemaking practices). Historically, even here, human communities' exploitation of local natural resources for the dairy value chain outlined a specific activity: the “transhumance” [29; 30]. Transhumance is an old pastoralism practice that in Alto Molise implied a seasonal movement of livestock, for example between higher pastures in summer and lower valleys in winter. Through this practice, the dairy products of the transhumant herds (milk, cheese, meat) circulated, creating a socioeconomic system with related services and more sustainable exploitation of nature. Transhumance and breeding activities promoted the management of forests and water basins essential for herds but with benefits for downstream activities (e.g., flood prevention) and ecosystem services (i.e., preventing forest degradation).

The socioeconomic changes in the last sixty year redefined the context of Alto Molise, transhumance is radically reduced but the dairy value chain continues to be a relevant part of the area's economic weft and local culture. In the municipality of Agnone two of the largest family cheese factories in the area have their headquarters: Di Nucci (since 1600, more information:

https://www.caseificiodinucci.it/) and Di Pasquo (since 1952, see here:

https://www.caseificiodipasquo.com/it/). However, as other mountain areas, this zone is characterized by depopulation and land abandonment that affect and change both the outline of the SES and the dairy value chain. According to the Italian Institute of Statistics (Istat), in the period January 2023 - January 2019, the depopulation of the five municipalities inquired is -6.4% compared to -4.6% of Molise, while the utilized agricultural area decreased in the last decade by more than 30%. These phenomena determine both a greater socio-economic and an environmental vulnerability in the area. The contraction of livestock activity is a problem for cheesemaking with local, high-quality milk and less management of the natural mountain environment.

4.2. Climate change in the area

As mentioned in the introduction, climate change worse the effect of depopulation, accelerating the damage to the socio-ecological system [7; 8]. Studies report that the consequence of global warming is pretty evident in the Alto Molise considering not only the change in air temperature and rainfall [

31] but also in the vegetation [

32]. In the area seems confirmed a process of thermophilization, to say that ongoing climate change gradually transforms mountain plant communities: more cold-adapted species decline, and the more warm-adapted species increase, which suggests a progressive decline of current mountain habitats and their biota.

Some data (

Table 4), elaborated by researcher of MOVING project (see acknowledgments), offer information on plausible future climate and environmental condition in the area in the case moderate climate intervention and policies (

Representative Concentration Pathways 4.5, RCP 4.5, by the

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, IPCC) and in the business-as-usual scenario (RCP 8.5 by the IPCC).

In

Table 4 is clear that the mean of seasonal temperature in the Alto Molise will tend to be higher compared with baseline data, and precipitation could dramatically increase in warm winter with consequences on vegetation and agricultural activities. In this climate scenario, extreme events will be relevant and unusual too.

This climate conditions could impact also on breeding activities and because change in meadows and pastures’ vegetable species, but also with the need to identify both cattle species adapted to the new climate regime and coherent forms of livestock breeding. To do so, farmers must clearly understand the risk of climate change to put in practice some actions to face the effect of global warming in their area.

5. Perception and experience of climate change

According to the theoretical and methodological perspective adopted, we highlight which initiatives are implemented or suggested facing climate change by different local actors. They perceive climate change differently because of their epistemology. In other words, the way how they experiment global warming is linked to their relation to the consequences of it, their knowledge, and interests. It this sense, farmers are aware of climate change as well as experts, but their perception and reactions depend on their viewpoints on it. Following we report similarities and differences emerge in stakeholders’ interviews on the climate change issue. Information reported refer particularly to two stakeholder groups, on the one hand researchers / experts / advisers, on the other farmers / cheesemakers. They seem more affected by consequences of climate change more than policymakers, policy authorities, that were involved specifically to evaluate adaptive mechanism to the global warming.

5.1. Natural resources and the effects of climate change

During the first research step, we detect which is considered the main natural resource (or reference variable) for the local dairy value chain by ten key actors. Despite stakeholders’ differences, they seem agree to identify the permanent grassland as the pivotal natural resource (

Table 5). However, actors directly involved in the breeding activities, like farmers and cheesemakers, report two elements: the permanent grassland and the hay.

If the permanent grassland is natural resource relevant for the breeding activity to obtain high-quality milk that features peculiarity to local cheeses, grazing in these areas tends to be costly and difficult to manage. In this sense, the cultivation of herbaceous hay varieties and their mowing to feed cattle seem a viable alternative to gazing in permanent grassland. Although their differences, these two resources (permanent grassland and hay) present high similarities in relation to the challenges provoked by the global warming. With some distinctions (

Table 6), stakeholders report as relevant problems for the reference variable are three, two of them directly related to climate change: temperature and precipitation. The other one depends on human presence; it refers to the depopulation. Others have a possible affect the main resource. Two are an outcome of a combination of natural and human aspects, like the soil physical degradation and the change in land-use and land-cover, while the last two are more linked to climate change (extreme events, pests and invasive species).

As it is clear on the

Table 6, stakeholders consider in different way some drivers of change because of their relations with the breeding activity and their knowledge. Despite interviewees agree to consider some elements particularly impactful to the main natural resources, based on their experiences and interests, farmers and cheesemakers report two other aspects that affect the natural resource compared with researchers or experts.

One is the extreme events, in particular the late spring frosts, the other is the soil physical degradation, specifically, they refer to rainfall erosion and landslides. Another difference is that farmers and cheesemakers concern as a possible element that affect the natural resource the spread of wildlife in the area with the reference to wild boars, because of the human depopulation, the reduction of its predator and competitors. It is also need to report that the spread of wild boars was promoted by a wicked repopulation policy with highly prolific allochthonous species. Wild boars compromised cultivated land and grassland quality by snuffling and digging the field, affecting the natural resource essential for dairy activity. They are also concerned about the possibility of fires becoming more frequent in the area in the future. Differences persist when we questioned an enlarged number of stakeholders (second research step, 20 subjects) to rate the drivers of change relevance to their impacts on the reference variable. Despite all stakeholders consider precipitation the main relevant drivers of change, and they agree to the relevance of others (e.g., temperature and demographic change), equally they rank them in a different way (

Table 7). It seems to confirm, on the one hand, that farmers and cheesemakers perceive the impact of the climate change considering its effects on the natural resource and its economic consequences on the value chain. Experts, on the other, report a more systemic view on effects of global warming in Alto Molise.

Respondents also identify interactions among drivers of change that affect the reference variable. Still, data seem to confirm that “lays” actors and experts, with their specific knowledge and epistemology, have different resources to interpret this systemic socio-ecological complexity.

Experts, for example, report how the shift in the rainfall regime has adverse effects on the physical state of the soil and influences the land-cover change. At the same time, the land-cover change can not only have a worsening effect on the state of the soil, but it could also favour the spread of pests and invasive species. In this sense, these actors identify the main problem in the climate change considering two parameters (temperature and precipitation), while farmers and cheesemakers consider effects of global warming with not clear correlation on them and the main major cause of it (temperature and precipitation change because of climate change).

This can explain why farmers and cheesemakers interviewed seem to link feedbacks of some drivers of change in an unclear way, despite they recognise how human activities in the area can reduce some negative aspects in the natural settings (

Table 8). Others interesting evidence emerge considering stakeholders opinion about climate future of the area and which actions they imagine adopting or are already adopted to face the effects of global warming in the zone.

5.2. Climate future and initiatives to face it

Considering four drivers that stakeholders report as particularly relevant (namely: temperature, precipitation, extreme events, and demographic change), in the second research step we ask if they observed a change in the last 20 years (

Table 9). In general, actors report a worsening of those drivers in the last 20 years. Moreover, their opinion on the future tends of them is quite pessimistic, and the negative effects on the reference variable would be relevant in the next 20 years. At the same time, stakeholders have an uncertain opinion on the future impact of the other drivers of change on the leading natural resource related to the local dairy value chain. Largely, they suppose climate will worsen, and grassland and hay will drastically suffer from that.

Again, farmers and experts have a different perception and opinion on how these stressors changed and how they will change in the future. Researchers and experts consider indicators of global warming, particularly temperature and precipitation, as slightly worsened over the last 20 years and believe that this trend may continue in the future. Moreover, they recognize that population significantly decreased but they are not able to define a clear trend because it is influenced by several variables, first rural policies, and the stubborn intention of people to invest and live in these places.

Farmers and cheesemakers appear with a high negative attitude on climate change and the demographic future of the area. At the same time, they are also more proactive than one might assume considering what is reported in

Table 9. Some solutions to face the effects of global warming in the area are proposed and in some cases are applied by them. During the interviews, farmers report some actions to put in place to reduce the effect of climate change but also to restrain depopulation. Some of them adopted cultivation and technological innovations as a solution to reduce particularly the risk of late frost. Some of them anticipate the mowing of lawns and using dryers to use the hay. Policy to promote the higher milk price and the exploitation of local natural resources (e.g., carbon credit for forests, tax reduction for breeding traditional practices) seem a solution to promote local development and reduce depopulation. Over time, farmers replaced local breeds of cattle (such as the “Podolica”) with more productive ones, generally bred in stables. Breeders adopted this solution for economic reasons: the relatively low milk price made breed outside the barn and using traditional local cattle breeds (less productive) unprofitable. Moreover, not adequate grazing services (e.g., drinking trough) and difficult to access or map municipal permanent grasslands, reduce the chance to use this resource. However, climate change impacts permanent grassland and hayfields, and some solutions can be applied in either case.

Table 10 reports possible solutions indicated by farmers. It seems evident that they are aware of innovations needed to face the effects of global warming. At the same time, farmers stress how policy must support resilience initiatives related to the reference variable and the community (and its economy), another essential part of the local socio-ecological system that supports the dairy value chain.

Experts and researchers express similar solutions compared to farmers, but they report two other aspects. On the one hand, experiment with reintroducing hardy cattle breeds or native cattle species for production diversification (milk and meat). On the other hand, monitor the state of permanent grassland, the presence of alien plant varieties and stimulate the practice of grazing on permanent grassland to manage the environmental quality. Political institutions should coordinate and support initiatives with the territory and local actors to implement these actions, the results of which will only be visible after a few years.

During the workshop (the third research step) were discussed the proposed solutions and emerged how most stakeholders (two-thirds of them) considered just a few of them as appropriate and easy options to implement. According to them, two solutions could promote resilience to climate change directly affecting the reference variable: experiment with new crop varieties and adopt technological innovation. While only improving services for grazing activities and communities can curb depopulation by promoting better living conditions and economic possibilities. Stakeholders do not have a clear opinion on the other possible solutions except expressing highly negative opinions in experiments to introduce new cattle breeds or reintroducing rustic and local ones. In the workshop seemed confirmed that all possible solutions proposed must consider the current market condition of the dairy value chain and the necessity of an adequate milk price for breeders. Whether the price of raw milk produced by rustic cattle breeds through grazing was appropriate to the higher costs of it and the low milk production of these cows, would farmers seem willing to consider this option. If not, stable breeding of specialized dairy breeds appears to be the most reasonable solution.

Even in the experts’ assessment (the fourth and last research step), experimenting diverse cow breeds appears a risky solution in the current market condition where the milk price is generally defined by cheesemakers considering few parameters (such as percentage of fat and protein, presence of somatic cells) that do not consider the possible high quality of raw, pasture-fed milk.

6. Discussion

Research data suggests that among stakeholders the ability to link local evidence of global warming with big picture of climate change presents some differences. Even resilience actions proposed or suggested are slightly diverse. The reason of divergence seems to lie at least in three explanations: 1) the way climate change affects them, 2) their position in the value chain, 3) their resource endowment (knowledge and financial). In short, results suggest that the working hypothesis according to stakeholders enact a specific agency capacity is influenced by their position in the socio-ecological system explain their perception of climate change. Moreover, we need to consider their position in the socioeconomic system, in the value chain, to understand solutions considered suitable and affordable. Our data indicate that their peculiar agency capacity is enacted and shaped by position in the socio-ecological and socioeconomic system. However, studies suggest that due to their position and resources, farmers may adopt inefficient solutions to deal with global warming, whose effects on production they do not fully grasp (e.g., they tend to consider intensive cattle breeding in cowsheds an adequate solution instead to adopt/adapt other breeding techniques and/or cattle breeds like Podolica or others).

Analysis on complex socio-ecological systems, like sub-Saharan and savannah areas, report how most of farmers noticed changes in climate and consequently adjusted their farming practices to adapt [33; 34]. In general, they vary planting dates, use of drought tolerant and early maturing varieties and tree planting. In this sense, these studies confirm farmers agency capacities, but some of them have limits in adapting due to lack both of information on suitable adaptation measures and credit. Farmers’ perception of climate risk is complex. According to studies [

35]

, farmers are aware of climate variability, but they tend to over-estimate risks of negative impacts and/or do not sufficiently understand the implications on their farms. They also fail to make use of good conditions when they occur (in some case they remain unresponsive to climate change policy). It seems also that farmers who observe decreasing crop production may not be distinguishing causes between rainfall change, decline of soil fertility or other conditions. For this, they are not able to adopt coherent solutions. As it was stressed [

36]

, local knowledge, place-based experience, values and perceptions of fairness (that vary across farmers) intersect with their identity enable or constrain adaptive action they are willing, or potentially able, to engage in. Works conclude that to ensure successful agriculture adaptation to climate change, to adopt resilience initiatives, we should design and promote planned adaptation measures that fit into the local context and educate farmers on climate change and appropriate adaptive and self-regulating measures.

Although research report relevant points stressing the epistemology distance between farmers and experts or policymakers, and the need to reduce knowledge and epistemology gap among them to face global warming, our work shows that farmer and experts are distant but their perceptions present similarities. Essentially, farmers are not passive or unaware actors, and their actions are driven by their resources and position in the field. In this sense, the here adopted conception of agency allows to explain differences and similarities as well as actors’ difficulties to implement adequate solutions. As it was stressed, conceptualizing “agency as practice” [18; 19] means focus not only on the single agent capacity but to the network of elements that allows to act. For this, farmers’ resilience to economic uncertainties and climate risks can be seen through a relational perspective [23;24] that involve not only human actants (farmers, cheesemakers, experts, policymakers, etc.) but also not-human ones (climate situation, cattle productivities, market conditions, laws, etc.). For this, ecological and social processes interact to undermine or strengthen actors’ resilience as well as relationalities enacted within a specific context. Assuming this theoretical viewpoint, it is possible to explore farmers’ diversity on climate resilience that is differently constructed in each context. As scholars showed, for example, in difficult socioeconomic contexts with traditional agriculture, farmers sustain resilience practices through local community interconnections and agroecological practices, while in modern ones (where local actors somewhat paradoxically place their territory), farmers rely more on institutional support, high access to information and new technologies [

37]

. In those situations, approach that focus on relations questioning the perception of climate change as a consequence of interactions and experiences and not as a self-perceived of isolated actors.

For these, participatory approaches may pave the way to context-specific actions to strengthen farming system resilience involving all relevant stakeholders (also considered as spokesperson of not human actants) in the field, starting point for developing a shared vision and action plan for climate resilience of farming systems [

38]

.

7. Conclusions

The work aimed to contribute to the scientific debate on climate resilience in mountain areas, particularly regarding agricultural activities. To this end, a theoretical perspective was adopted that considers the agency capacity of mountain area actors as a practice defined in the socio-ecological system. In this sense, the agency is the product of a heterogeneous collective, not an individual's quality. Therefore, although epistemic distances are quite clear among stakeholders, they share the field within which their actions and perception are structured. Farmers appeared competent and aware of the interactions in which they are immersed and of the spaces to define solutions to resist the adverse effects of climate change and depopulation (a further element to consider in the socio-ecological system and which climate change risks aggravating).

Consequently, participatory ways of defining policies and initiatives to face climate change should consider the socio-ecological (but also socio-economic) system and "lay" knowledge, which is as valid as those of experts. Experts, in fact, often are disengaged from specific social dynamics that make countering initiatives possible. The research does, however, have some weaknesses that require further investigation.

First, the stakeholders interviewed are mainly farmers and cheesemakers, while other stakeholders are less represented. This did not allow us to indicate the differences between mountain actors enough adequately. Second, we adopted a qualitative research methodology that does not allow us to quantify the differences between the social actors. It does not also help us to precisely delineate stakeholders' evaluations of the various aspects investigated. Third, the work focuses on a case study, and it does not allow for adequate verification of the relationship between the socio-territorial, economic, and climatic context with the perception of the effects of global warming of the various actors questioned. Considering these reasons, and limits, future studies could better investigate the validity of the working hypothesis in this work, and the usefulness of adopting a theoretical perspective taking in count the agency as a collective product of a localized heterogeneous set of actants.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.I. and I.S.; methodology, A.B., C.I., I.S.; validation, A.B., L.B., S.B., C.I., I.S.; formal analysis, I.S; investigation, A.B., L.B., C.I., I.S.; data curation, S.B., I.S.; writing—original draft preparation, I.S.; writing—review and editing, A.B., L.B., C.I., I.S; supervision, C.I.; project administration, C.I.; funding acquisition, C.I.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded under the MOVING project (Mountain Valorisation through interconnectedness and green growth -

www.moving-h2020.eu/) as part of the Horizon 2020 Programme (Grant Agreement No.: 862739). The views expressed in this article are solely those of the authors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgements

The methodology here adapted refers to “Guidelines Vulnerability Analysis - WP3” for MOVING project elaborate by Javier Moreno (UCO), Pablo González-Moreno (UCO), Guillermo Palacios (UCO), María del Mar Delgado (UCO), Sherman Farhad, Carmen Maestre (UCO) José Ángel Hurtado (UCO) and Teresa Pinto-Correia (UÉvora), Élia Pires-Marques (UÉvora), Nuno Ricardo Gracinhas Nunes Guiomar (UÉvora). Climate information reported in table 4 refers to data used in “D3.2: Land use system vulnerability matrixes and vulnerability maps for the 23 reference regions” for MOVING project elaborated by Pablo González-Moreno (UCO), Javier Moreno (UCO), Teresa Pinto-Correia (UÉvora), Élia Pires-Marques (UÉvora), Guillermo Palacios (UCO), Nuno Ricardo Gracinhas Nunes Guiomar (UÉvora), Sherman Farhad (UCO) and María del Mar Delgado (UCO).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Caniglia, B.S.; Mayer, B. Socio-ecological systems. In Handbook of environmental sociology; Caniglia, B.S., Jorgenson, A., Malin, S.A., Peek, L., Pellow, D.N., Huang, X., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 517–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, N.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. Mountain food products: A broad spectrum of market potential to be exploited. Trends in Food Science & Technology 2017, 67, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, N. Landscape and branding: The promotion and production of place; Routledge: London and New York, UK and US, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission Europe’s jewels: Mountains, islands and sparsely populated areas; Bruxelles, 2019.

- MacDonald, D.; Crabtree, J.R.; Wiesinger, G.; Dax, T.; Stamou, N.; Fleury, P.; Gutierrez Lazpita, J.; Gibon, A. Agricultural abandonment in mountain areas of Europe: Environmental consequences and policy response. Journal of Environmental Management 2000, 59, 47–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Abraín, A.; Jiménez, J.; Jiménez, I.; Ferrer, A.; Llaneza, L.; Ferrer, M.; Palomero, G.; Ballesteros, B.; Galán, P.; Oro, D. Ecological consequences of human depopulation of rural areas on wildlife: A unifying perspective. Biological Conservation 2020, 252, 108860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A. Mountains as vulnerable places: a global synthesis of changing mountain systems in the Anthropocene. GeoJournal 2021, 86, 585–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beniston, M. Climatic change in mountain regions: A review of possible impacts. Climatic Change 2003, 59, 5–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiderbauer, S.; Fontanella Pisa, P.; Delves, J. L.; Pedoth, L.; Rufat, S.; Erschbame, M.; Thaler, T.; Carnelli, F.; Granados-Chahin, S. Risk perception of climate change and natural hazards in global mountain regions: A critical review. Science of the Total Environment 2021, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingty, T. High mountain communities and climate change adaptation, traditional ecological knowledge, and institutions. Climate change 2017, 145, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soubrya, B; Sherrenb, K. ; Thornton, T.F. Are we taking farmers seriously? A review of the literature on farmer perceptions and climate change, 2007–2018. Journal of Rural Studies 2020, 74, 210–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, V. Re-figuring the problem of farmer agency in agri-food studies: A translation approach. Agriculture and Human Values 2006, 23, 51–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolinska, A.; d'Aquino, P. Farmers as agents in innovation systems. Empowering farmers for innovation through communities of practice. Agricultural Systems 2016, 142, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, R.; Luthe, T.; Pedoth, L.; Schneiderbauer, S.; Adler, C.; et al. Mountain resilience: a systematic literature review and paths to the future. Mountain Research and Development 2022, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Nishi, M.; Gasparatos, A. Community based responses for tackling environmental and socioeconomic change and impacts in mountain social-ecological systems. Ambio 2021, 51, 1123–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebughini, P. Agency. In Framing Social Theory. Reassembling the Lexicon of Contemporary Social Sciences, 1st ed.; Rebughini, P., Colombo, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2022; pp. 20–38. [Google Scholar]

- Pellizzoni, L. Catching up with things? Environmental sociology and the material turn in social theory. Environmental Sociology 2016, 2, 312–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latour, B. Reassembling the social: an introduction to Actor-Network-Theory; Oxford: Oxford University Press, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, P. Practical reason: on the theory of action; Stanford University Press: Stanford, US, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Castree, N. False Antitheses? Marxism, Nature and Actor-Networks. Antipode 2002, 34, 111–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blumer, H. What is wrong with social theory? American Sociological Review 1954, 18, 3–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moretti, M.; Belliggiano, A.; Grando, S.; Felici, F.; Scotti, I.; Ievoli, C.; Blackstock, K.; Delgado-Serrano, M.M.; Brunori, G. Characterizing value chains’ contribution to resilient and sustainable development in European mountain areas. Journal of Rural Studies 2023, 100, 103022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnhofer, I.; Lamine, C.; Strauss, A.; Navarrete, M. The resilience of family farms: Towards a relational approach. Journal of Rural Studies 2016, 44, 111e122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnhofer, I. Resilience and why it matters for farm management. European Review of Agricultural Economics 2014, 41, 461–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyss, R.; Luthe, T.; Pedoth, L.; Schneiderbauer, S.; Adler, C. et al. Mountain resilience: a systematic literature review and paths to the future; Mountain Research and Development. 2022, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ievoli, C.; Basile, R.; Belliggiano, A. The spatial patterns of dairy farming in Molise. European Countryside 2017, 9, 729–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paas, W.; Coopmans, I.; Severini, S.; Van Ittersum, M. K.; Meuwissen, M. P. M.; Reidsma, P. Participatory assessment of sustainability and resilience of three specialized farming systems. Ecology and Society 2021, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simone, C.; Barondini, M. E.; Calabrese, M. Firm and territory: in searching for a sustainable relation. Four cases study from Italian secular firms. International Journal of Environment and Health 2015, 7, 329–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindi, L. Transhumance is the new black: fragile rangelands. In Grazing communities. Pastoralism on the move and biocultural heritage frictions; Bindi, L., Ed.; Berghahn: New York – Oxford, US and UK, 2022; pp. 149–173. [Google Scholar]

- Bindi, L. “Bones” and pathways. Transhumant tracks, inner areas and cultural heritage. Il capitale culturale 2019, 19, 109–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izzo, M.; Aucelli, P.P.C.; Mazzarella, A. Recent changes in rainfall and air temperature at Agnone (Molise - Central Italy). Annals of Geophysics, 2004, 47, 1689–1698. [Google Scholar]

- Gottfried, M.; Pauli, H.; Futschik, A.; et al. Continent-wide response of mountain vegetation to climate change. Nature Climate Change, 2012, 2, 111–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambo, J.A. , Abdoulaye T. Smallholder farmers’ perceptions of and adaptations to climate change in the Nigerian savanna. Regional Environmental Change, 2013, 13, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coe, R. , Stern, R.D. Assessing and addressing climate-change risk in sub-Saharan rainfed agriculture: lessons learned. Experimental Agriculture, 2011, 47, 395–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malhi, G.S.; Kaur, M.; Kaushik, P. Impact of climate change on agriculture and its mitigation strategies: a review. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, C. , Wreford, A., Cradock-Henry, N. ‘As a farmer you’ve just got to learn to cope’: Understanding dairy farmers’ perceptions of climate change and adaptation decisions in the lower South Island of Aotearoa-New Zealand. Journal of Rural Studies 2023, 98, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Goff, U.; Sander, A.; Lagana, M.H.; Barjolle, D.; Phillips, S.; Six, J. Raising up to the climate challenge - Understanding and assessing farmers’ strategies to build their resilience. A comparative analysis between Ugandan and Swiss farmers. Journal of Rural Studies 2022, 89, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paas, W.; Coopmans, I.; Severini, S.; Van Ittersum, M. K.; Meuwissen, M.P.M.; Reidsma, P. Participatory assessment of sustainability and resilience of three specialized farming systems. Ecology and Society 2021, 26, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).