Submitted:

23 August 2023

Posted:

24 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients

2.2. Endoscopic equiments and accessories

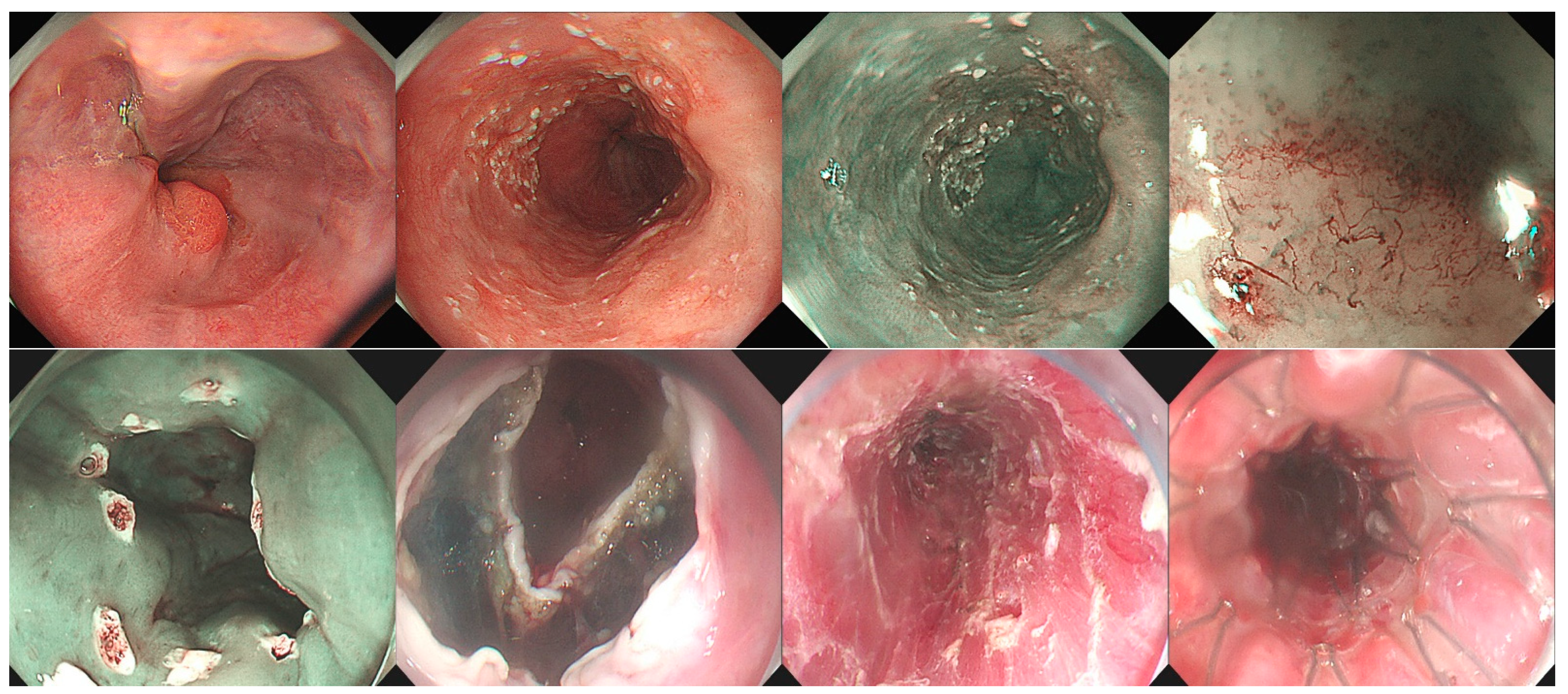

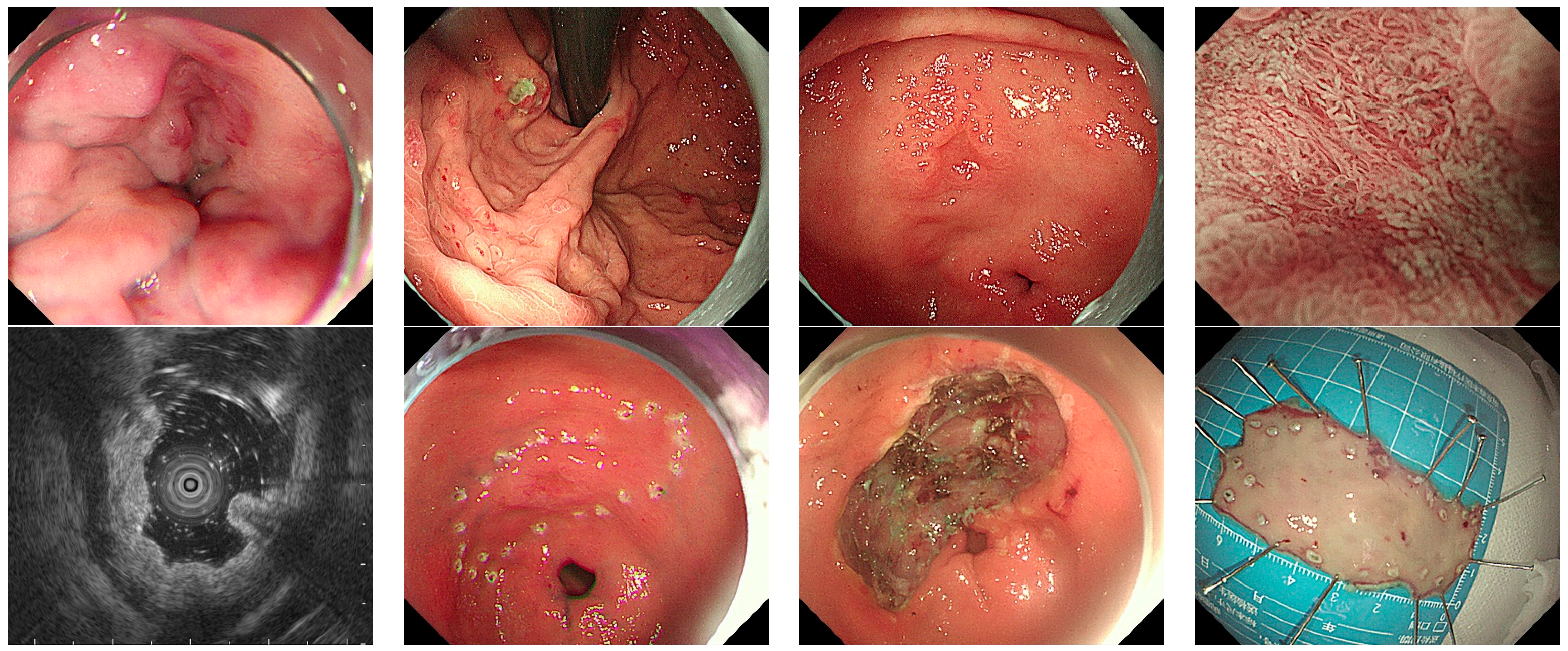

2.3. ESD procedure

2.4. Preoperative and postoperative management

2.5. Pathological assessment

2.6. Pathological assessment

3. Results

3.1. Basic clinical characteristics

3.2. Treatment outcomes

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, M.; Chen, S.; Hu, J.; Guo, Q.; Liu, R.; Zheng, H.; Jin, Z.; Yuan, Y.; Xi, Y.; Hua, B. Endoscopic Screening in Asian Countries Is Associated With Reduced Gastric Cancer Mortality: A Meta-analysis and Systematic Review. Gastroenterology. 2018, 155, 347–354.e9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Ding, L.; Qiu, X.; Meng, F. Updated evaluation of endoscopic submucosal dissection versus surgery for early gastric cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Surg. 2020, 73, 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bestetti, A.M.; de Moura, D.T.H.; Proença, I.M.; Junior, E.S.D.M.; Ribeiro, I.B.; Sasso, J.G.R.J.; Kum, A.S.T.; Sánchez-Luna, S.A.; Marques Bernardo, W.; de Moura, E.G.H. Endoscopic Resection Versus Surgery in the Treatment of Early Gastric Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Oncol. 2022, 12, 939244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Kang, N.; Huang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, R. Endoscopic resection versus esophagectomy for early esophageal cancer: a meta-analysis. Transl Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 2653–2662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Li, P.; Wen, W.; Jian, Y. Comparison of Long-Term Survival Between cT1N0 Stage Esophageal Cancer Patients Receiving Endoscopic Dissection and Esophagectomy: A Meta-Analysis. Front Surg. 2022, 9, 917689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.; Zhou, X.; Hu, M.; Pan, J. Endoscopic submucosal dissection versus endoscopic mucosal resection for patients with early gastric cancer: a meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019, 9, e025803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Yu, J.; Yao, N.; Li, X.; Yang, Y.; Wang, L.; Sun, M.; Guo, Y.; Wang, H.; Yan, S.; Li, B. Efficacy and Safety of Four Different Endoscopic Treatments for Early Esophageal Cancer: a Network Meta-analysis. J Gastrointest Surg. 2022, 26, 1097–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinese Society of Hepatology,Chinese Medical Association. [Chinese guidelines on the management of liver cirrhosis]. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2019, 27, 846–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, D.; Angelico, F.; Caldwell, S.H.; Violi, F. Bleeding and thrombosis in cirrhotic patients: what really matters? Dig Liver Dis. 2012, 44, 275–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choe, W.H.; Kim, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Kim, H.U.; Cho, D.H.; Lee, S.P.; Lee, T.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Sung, I.K.; Park, H.S.; Shim, C.S. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection of Early Gastric Cancer in Patients with Liver Cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2018, 63, 466–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.H.; Joo, M.K.; Yoo, A.Y.; Kim, S.M.; Kim, W.S.; Lee, B.J.; Park, J.J.; Chun, H.J.; Lee, S.W. Long-term outcome of the endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer: A comparison between patients with and without liver cirrhosis. Oncol Lett. 2022, 24, 404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yabuta, T.; Nishihara, A.; Hayashi, Y.; Yamada, T.; Takehara, T. Outcomes of ESD for patients with early gastric cancer and comorbid liver cirrhosis: a propensity score analysis. Surg Endosc. 2015, 29, 1560–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.L.; Liu, L.X.; Wu, J.C.; Gan, T.; Yang, J.L. Endoscopic submucosal tunnel dissection for early esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis: A propensity score analysis. World J Clin Cases. 2022, 10, 11325–11337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonnot, M.; Deprez, P.H.; Pioche, M.; Albuisson, E.; Wallenhorst, T.; Caillol, F.; Koch, S.; Coron, E.; Archambeaud, I.; Jacques, J.; Basile, P.; Caillo, L.; Degand, T.; Lepilliez, V.; Grandval, P.; Culetto, A.; Vanbiervliet, G.; Camus Duboc, M.; Gronier, O.; Leal, C.; Albouys, J.; Chevaux, J.B.; Barret, M.; Schaefer, M. Endoscopic resection of early esophageal tumors in patients with cirrhosis or portal hypertension: a multicenter observational study. Endoscopy. 2023 Jul 13. [CrossRef]

- Gong, J.; Zhou, B.Y.; Liang, C.B.; Zhou, H.J.; Wang, H.Y.; Tan, Y.Y.; Liu, D.L. Comparison between tunneling and standard endoscopic submucosal dissection for treatment of large esophageal superficial neoplasm. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2019, 82, 469–474. [Google Scholar]

- Esaki, M.; Ihara, E.; Gotoda, T. Endoscopic instruments and techniques in endoscopic submucosal dissection for early gastric cancer. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021, 15, 1009–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asrani, S.K.; Devarbhavi, H.; Eaton, J.; Kamath, P.S. Burden of liver diseases in the world. J Hepatol. 2019, 70, 151–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zullo, A.; Romiti, A.; Tomao, S.; Hassan, C.; Rinaldi, V.; Giustini, M.; Morini, S.; Taggi, F. Gastric cancer prevalence in patients with liver cirrhosis. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2003, 12, 179–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randi, G.; Altieri, A.; Gallus, S.; Franceschi, S.; Negri, E.; Talamini, R.; La Vecchia, C. History of cirrhosis and risk of digestive tract neoplasms. Ann Oncol. 2005, 16, 1551–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sorensen, H.T.; Friis, S.; Olsen, J.H.; Thulstrup, A.M.; Mellemkjaer, L.; Linet, M.; Trichopoulos, D.; Vilstrup, H.; Olsen, J. Risk of liver and other types of cancer in patients with cirrhosis: a nationwide cohort study in Denmark. Hepatology. 1998, 28, 921–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chandan, S.; Deliwala, S.; Khan, S.R.; Ramai, D.; Mohan, B.P.; Bilal, M.; Facciorusso, A.; Kassab, L.L.; Kamal, F.; Dhindsa, B.; Perisetti, A.; Adler, D.G. Advanced Endoscopic Resection Techniques in Cirrhosis-A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Outcomes. Dig Dis Sci. 2022, 67, 4813–4826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Repici, A.; Pagano, N.; Hassan, C.; Cavenati, S.; Rando, G.; Spaggiari, P.; Sharma, P.; Zullo, A. Endoscopic submucosal dissection of gastric neoplastic lesions in patients with liver cirrhosis: a systematic review. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2012, 21, 303–7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kwon, Y.L.; Kim, E.S.; Lee, K.I.; Kim, Y.J.; Park, C.W.; Kim, Y.J.; Seo, H.J.; Cho, K.B.; Park, K.S.; Jang, B.K.; Chung, W.J.; Hwang, J.S. Endoscopic treatments of gastric mucosal lesions are not riskier in patients with chronic renal failure or liver cirrhosis. Surg Endosc. 2011, 25, 1994–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zullo, A.; Hassan, C.; Bruzzese, V. Comment to “Bleeding and thrombosis in cirrhotic patients: what really matters? ”. Dig Liver Dis. 2012, 44, 1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawaguchi, C.; Takahashi, Y.; Hanesaka, Y.; Yoshioka, A. The in vitro analysis of the coagulation mechanism of activated factor VII using thrombelastogram. Thromb Haemost. 2002, 88, 768–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, Y.D.; Chai, N.L.; Yao, Y.; Gao, F.; Liu, B.; He, Z.D.; Bai, L.; Huang, X.; Gao, C.; Linghu, E.Q.; Li, L.Y. Endoscopic submucosal dissection for early cancers or precancerous lesions of the upper GI tract in cirrhotic patients with esophagogastric varices: 10-year experience from a large tertiary center in China. Gastrointest Endosc. 2023, 97, 1031–1044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawaguchi, M.; Jin, M.; Matsuhashi, T.; Ohba, R.; Hatakeyama, N.; Koizumi, S.; Onochi, K.; Yamada, Y.; Kanazawa, N.; Kimura, Y.; Tawaraya, S.; Watanabe, N.; Suzuki, Y.; Mashima, H.; Ohnishi, H. The feasibility of endoscopic submucosal dissection for superficial esophageal cancer in patients with cirrhosis (with video). Gastrointest Endosc. 2014, 79, 681–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovani, M.; Anderloni, A.; Carrara, S.; Loriga, A.; Ciscato, C.; Ferrara, E.C.; Repici, A. Circumferential endoscopic submucosal dissection of a squamous cell carcinoma in a cirrhotic patient with esophageal varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015, 82, 963–4, discussion 964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masui, Y.; Ohno, K.; Itai, R.; Kurokami, T.; Endo, S. Successful endoscopic submucosal dissection of early gastric cancer located on gastric varices after treatment with balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2021, 14, 1550–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.G.; Zhao, Y.B.; Yu, J.; Bai, J.Y.; Liu, E.; Tang, B.; Yang, S.M. Novel endoscopic treatment strategy for early esophageal cancer in cirrhotic patients with esophageal varices. Oncol Lett. 2019, 18, 2560–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Renteln, D.; Riecken, B.; Muehleisen, H.; Caca, K. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt and endoscopic submucosal dissection for treatment of early gastric cancer in a cirrhotic patient. Endoscopy. 2008, 40 Suppl 2, E32–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.L.; Chang, I.W.; Chen, C.C.; Chang, C.Y.; Mo, L.R.; Lin, J.T.; Wang, H.P.; Lee, C.T. A case series on the use of circumferential radiofrequency ablation for early esophageal squamous neoplasias in patients with esophageal varices. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017, 85, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Namikawa, T.; Iwabu, J.; Munekage, M.; Uemura, S.; Maeda, H.; Kitagawa, H.; Nakayama, T.; Fukuhara, H.; Inoue, K.; Al-Sheikh, M.; Jaiswal, N.; Kobayashi, M.; Hanazaki, K. Laparoscopic-endoscopic cooperative surgery for early gastric cancer with gastroesophageal varices. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2020, 13, 539–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Case No. |

Sex | Age (year-old) | Course of liver cirrhosis | Etiology of liver cirrhosis | Presence of GOV | History of GOV therapy | PLT (x10^9/L) | Hb (g/L) | INR | ALB (g/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | 68 | 1 year | HBV | Yes | No | 72 | 110 | 1.37 | 32.6 |

| 2 | Female | 70 | 5 years | cryptogenic | Yes | 2 times | 46 | 69 | 1.17 | 28.3 |

| 3 | Female | 59 | 1 week | HBV | No | No | 35 | 115 | 1.18 | 36.1 |

| 4 | Male | 52 | 5 years | cryptogenic | Yes | No | 96 | 113 | 1.43 | 27.5 |

| 5 | Male | 64 | 1 year | Alcoholic | Yes | 3 times | 56 | 111 | 1.45 | 32.3 |

| 6 | Female | 56 | 6 months | Budd-Chiari | No | No | 81 | 147 | 0.93 | 44.5 |

| 7 | Female | 64 | 0 | cryptogenic | No | No | 169 | 99 | 1.03 | 32.8 |

| 8 | Male | 43 | 8 months | HCV | No | No | 145 | 158 | 0.98 | 42.2 |

| Case No. |

Location | Size (cm) | Relationship with GOV | Perioperative PLT infusion | Perioperative plasma infusion | Operation time (min) | Pathology | En bloc resection | Intraoperative bleeding | Postoperative complication | Follow up (month) | Recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gastric body | 2x2 | Far from | No | No | 110 | HGIN | Yes | No | No | 45 | No |

| 2 | Gastric antrum | 4x2 | Far from | Yes | Yes | 105 | Tub1 m2 | Yes | Yes | No | 15 | No |

| 3 | Gastric antrum | 4.4x3.5 | NA | Yes | No | 70 | Tub2 m3 | Yes | Yes | No | 3 | No |

| 4 | Esophagus | 6x2 | On | No | Yes | 180 | ESCC sm2 | Yes | Yes | Chest pain Fever |

5 | No |

| 5 | Gastric antrum | 4.5x3.5 | Far from | No | Yes | 230 | Tub1/Tub 2, m3 | No | Yes | No | 15 | No |

| 6 | Gastric antrum | 3x3 | NA | NO | No | 70 | LGIN | Yes | No | No | 18 | No |

| 7 | Gastric body | 2x1.8 | NA | No | No | 45 | Adenoma | Yes | No | No | 15 | No |

| 8 | Gastric antrum | 2.6x2 | NA | No | No | 70 | HGIN | No | No | No | 16 | No |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).