Introduction

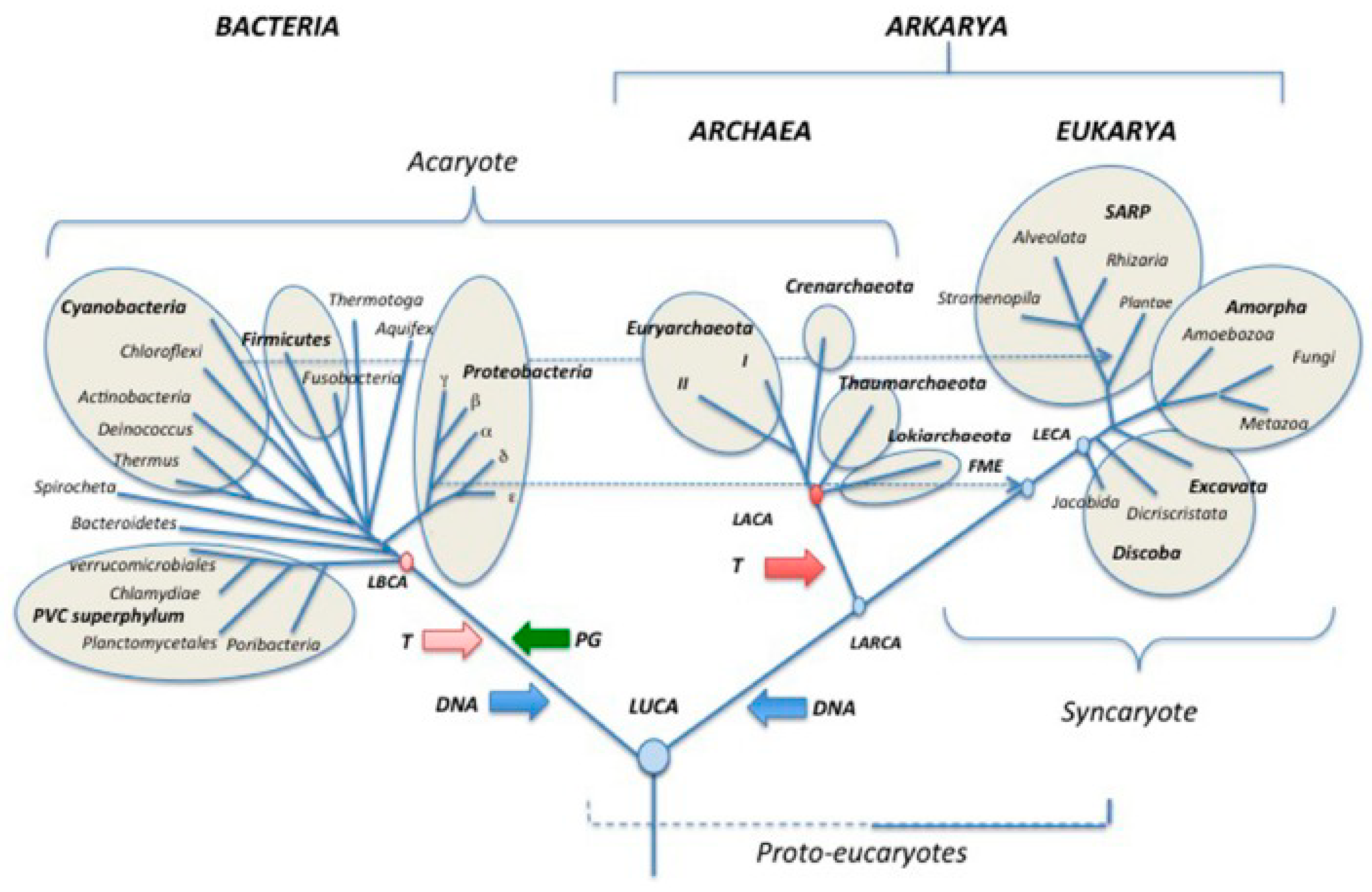

Cancer is a disease caused by the reactivated genome of the common AMF ancestor that has branched amoebozoans, metazoans, and fungi (

Figure 1), and its gene regulatory network aGRN. Both are conserved in the genome of humans and metazoans and can be reactivated by damaged dysregulated host cells. From molecular and cell biological viewpoints cancer follows ancient evolutionary rules and programs from a deep past, possibly more than 1000 Myas ago. Considering the logic and rationality of adaptionist evolution as well as the evolutionary selection and retention of traits, cancer is an anomaly, and ultimately an evolutionary disaster

. This work is an attempt to analyze, select and systematize details on precancerous and cancerous cell biology, from an evolutionary perspective.

In recent years, our understanding of cancer and its evolution has changed dramatically. Understanding cancer and cancer origin cannot be done without considering evolutionary history [

1]. It was the evolutionary life cycle biology that helped to clarify similarities and homologies between the germ and soma (G+S) life cycle evolved by the common AMF ancestor, its Urgermline, and the life cycle of cancer (

Table 1). In this context, the non-gametogenic (NG) germline of cancer appears as a germline of ancestral imprint [

2]. The transition to the ancestral G+S life cycle represents a fulminant genome change towards AMF genes, their dominance, and control by the aGRN. From a molecular perspective, cancer exploits the genes of an premetazoan gene network conserved in humans and metazoans [

3]. Cancer has a hybrid genome composed of ancient constitutive premetazoan genes and more recent human genes. Urgermline genes and developmental programs are not only involved in oncogenesis and tumorigenesis. They also regulate the asymmetric cell cycle and asymmetric cell division (ACD) in non-cancerous and cancerous cells, including stemness, and differentiation [

4].

Currently, efforts are underway to find the most common precancerous cell phenotype that triggers oncogenesis in all sporadic solid cancers, regardless of tissue and origin, as well as the basic principles that govern oncogenic transformation. Evidence shows that the premalignant cell arising from a dysfunctional ACD cell is a distinct cell phenotype that lacks stemness and differentiation capacity. It cannot give rise to either non-cancerous or cancerous stem cells. It survives and proliferates by defective symmetric cell cycling and defective symmetric cell division (DSCD). A distinction can be made between early proliferating and older, dormant DSCDs that remain quiescent in the niche for years or undergo slow cycling

1. Premetazoan ancestry

The non-gametogenic (NG) Urgermline evolved more than a thousand My ago. as an oxygen-sensitive hypoxic cell line. As ambient oxygen increases, the oxygen-sensitive Urgermline, which had a restricted DNA damage repair system (DDR), founded a somatic sister cell line resistant to O2 and an interactive germ and soma cell system (G+S) capable to preserve genome integrity. From this evolutionary time point, the two cell lines have distinct functions: The central function of the NG germline was to produce stem cells, whereas the primary function of the somatic cell line was to maintain genomic integrity under all living conditions, including hyperoxia of more than 6.0% O2. This division of labor was maintained by all G+S life cycles of protists and cancer.

Under normoxic conditions, both cell lines continue proliferation through asymmetric cell division (ACD). While one of the daughter cells (d1 cell) was the self-renewing cell, the other daughter cell (d2 cell) committed either to a differentiated stem cell or to a quiescent G1/G0 cell that did not express differentiatiion and stemness [

1,

2].

Under hyperoxia conditions, both cell lines switch from the ACD phenotype with non-identical daughter cells into an SCD phenotype with identical daughter cells. Phenotype switching by epigenetic modification is a form of oxygen-dependent plasticity introduced by the ancestors of AMF. Cells of the ACD phenotype that give rise to non-identical daughter cells can, under appropriate environmental conditions, convert to the SCD phenotype and vice versa. This hyperoxic transformation is not problematic for the oxygen-resistant somatic cell lineage but is quite problematic for all germlines of Urgermline imprint.

Hyperoxia with more as 6.0% O2 alters the germline genome and drives germline cells into defective symmetric cell cycling (DSCD), irreversible DNA replication defects, and defective cell division, with spindle defects, multinucleation, and premature cell division caused by immature nuclei [

1,

2,

3,

4]. The DNA defects can not be repaired by homologous recombination (HR). The DSCD cell is an HR-deficient germline cell (HRD cell) that loss function and can not differentiate stem cells. When hyperoxic living cells return to normoxia, somatic cells containing the undamaged genome transform into functional germ cells by soma-to-germ cell transition (SGT), forming eficient germline clones with stemness and ACD potential.

To repair the damaged DSCD genome, the AMF ancestor developed additional germline repair mechanisms by cell and nuclear fusion [

1,

4,

5,

6]. DSCD cells get fusionable, form multinucleated syncytia, and the individual syncytia nuclei fuse into a hyperpolyploid giant nucleus capable to excise defective DNA regions and reconstitute genome integrity. Such multinucleated genome repair structures (MGRSs) exist in protists and metazoan cancers better known as PGCCs [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

In protists, the DSCD repair system is a multi-step process with four distinct stages. Stage I is a DSCD proliferation phase as described above; if the cells find sufficient growth resources, they proliferate indefinitely as DSCD cells. Stage II is the phae as DSCD cells become fusible and fuse to form multinucleated MGRS syncytia. Stage III is a nuclear fusion phase; individual MGRS nuclei fuse to giant hyperpolyploid nuclei that can repair DNA damage and reconstruct the whole functional genome. Stage IV is a phase of genome alteration, cellularization and formation of spores (buds); they restart the G+S life cycle of AMF imprint and form germline stem cells (aGSCs).

DSCD cells have a long evolutionary history. They always arise when the descendants of the NG Urgermline are exposed to hyperoxia with more as 6.0% O2 content. The defective DSCD phenotype exhibits irreparable DNA defects and loss of the ACD function that drives self-renewal, stemness and differentiation. In protists such as Entamoeba it continuously proliferates in hyperoxic cultures but cannot revert to the normal ACD cell phenotype.

MGRS repair by cell and nuclear fusion are characteristic for protists and cancer and are absent in healthy humans and mammals. DSCD repair occurs in hyperpolyploid MGRS (precancerous PGCCs). In the precancerous development DSCD cells represent an ectopic cell phenotype in need of repair.

However, human DSCDs activate an inappropriate repair system from the ancestral treasury conserved in metazoan and human genome that remodels the DSCD genome and triggers carcinogenesis and tumorigenesis. The ancient GRN network trumps the human genome

2. DSCD cells in humans

DSCD-like phenotypes have also been discovered in humans and mammals. They are found in various tissues and are prime candidates for oncogenic transformation. Based on certain pluripotency markers, they are referred to as very small embryo-like cells (VSELs). VSEL cells have been suggested to be related to pluripotent stem cells (PSCs, ESCs) and to extragonadal germ cells (EGCs) that generate extragonadal germ cell tumors (EGCTs). Acording to Barati et al. (2021), VSEL cells could have a proximal epiblast origin. The scientists believe that “a group of pluripotent primordial germ cells (PGSs) seats in other tissues where they remain silent“

[7,8]. Such cells could be found in bone marrow, brain, pancreas, thymus and intestinal epithelium, and ovarian and testis surface epithelium in humans and rodents [

9,

10].

Alternatively, it has been proposed that VSELs are a type of migratory stem cells that are released from the bone marrow niche into the bloodstream under stress conditions [

11]. VSELs have also been isolated from human ESC cultures and are thought to be defective ACD phenotypes (irreparable DSCD cells) that arise under hyperoxic culture conditions and tissue hyperoxia of an O2 content greater than 6.0%. There are reasons to believe that VSEL, like DSCD, are damaged cell types on the way to oncogenesis. They all belong to a large DSCD family

DSCDs are the cell-of-origin of cancer. In humans and mammals, the DSCD family can be defined as disrupted tissue resident cognates of adult stem or progenitor cells. It is becoming increasingly clear that oncogenic transformation is a multistep process homologous to the DSCD repair process by MGRS. This multi-phase process has been partially identified by recent cancer research. Unfortunately, the partially discovered pieces of the puzzle could not lead to a satisfactory overview until evolutionary knowledge was available.. However, once it is clear how the Urgermline responded to stressors and irreparable DNA damage and what repair mechanisms were available to it, the parallelism between the oncogenic response and the DNA damage response (DDR) of the Urgermline becomes abundantly clear, as shown below.

3. The road to cancer

The preliminary stages of cancer development include the same steps known from DSCD genome repair in protists (Entamoeba).

3.1. The point of no return: ACD disruption and DSCD hyperproliferation

Tumor researchers have shown that asymmetric cell division and differentiation in Drosophila may act as a tumor suppressor mechanism,

while disruption of ACD drives cells to abnormal proliferation and genomic instability. Gomez-Lopez et al. described in 2014 that loss-of-function in key ACD regulators and loss of ACD capacity may be involved in oncogenesis [

12]. According to the researchers, ACD disruption leads to “

hyperproliferative phenotypes in situ that divide more symmetrically and generate

misspecified progeny that does not exit the cell cycle for differentiatiation and proliferate continuously". Loss of cell fate with increased proliferation and evasion of cell cycle control, which correlates with loss of polarity, spindle control, and mitotic errors, were considered early steps in cancer development.

In a 2018 work on normal cell response to replication stress (RSR) McGrail et al. found that extensive DNA damage usually leads to senescence and apoptosis, while defects in RSR lead to hyperproliferation that ultimately leads to early tumorigenesis. [

13] In their opinion, RSR defects in progenitor cells can improve cancer risk and place non-malignant cells in a

CSC-like state. [

14]. Accordingly, DNA damage, RSR defects, and hyperproliferation cause genomic instability and are key features of early cancer development.

3.2. Temporary DSCD quiescence

While DSCD cells that have passed the point of no return and can only proliferate symmetrically and hyperproliferatively, later VSEL/EGC phenotypes appear to arise as descendants of early DSCDs. Disrupted VSEL/EGC phenotypes are tissue-resident cells, most of which are dormant in tissues and niches. The dormant quiescent state is achieved by downregulation of growth factor Igf2 and upregulation of tumor suppressor gene H19, which promote or inhibit growth, respectively [

15]. VSELs/EGCs express not only pluripotency but also germline markers. They can also proliferate by SCDs, resulting in a fusible DSCD phenotype.

3.3. Cell and nuclear fusion; hyperpolyploidization

Cell fusion and MGRSs/PGCCs occur in both protists and cancer. In humans, the gnes of the ancient MGRS repair mechanism are exploited by precancerous DSCD cells as well as stress-damaged germline cells and CSCs. In irradiated or chemotherapeutic treated cell populations, genome reconstitution can also occur by tetraploidization without cell and nuclear fusion.

There is limited information on the oncogenic transformation and fusion ability of late VSELs/EGCs cells, but there is more information on the homologous and non-homologous fusion potential of cancer germline cells.

Homotypic cell fusions have been observed in glioblastoma cancer cells after irradiation, but more frequently in cultures, indicating that irradiation cannot destroy the ability of germline-like cells to transform into fusible phenotypes. [

16,

17,

18,

19]; Kaur et al. showed after irradiation that mononucleated radioresistant cells (RR cells) enter the G2/M phase [

16]. Similar to the DSCD cells of protists (Entamoeba), non-proliferative RR cells are highly motile, fuse homotypically and enter a process of DNA damage repair (DDR).

According to the researchers above, homotypic fusion is a reaction of cancer RR cells to overcome extrinsic stress. It is involved in the initiation of cancer and is essential for the formation of cancer stem cells [

20]. Homotypic cell fusion is inherited from the Urgermline and takes place in non-cancerous cell systems to repair irreversible DNA damage and recover genetic integrity. In protists, it helps to regain new germline clones as well as ACD, differentiation potential, and stemness [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

Heterotypic cell fusions have also been observed in the generation of secondary CSCs (tumor CSCs), which result from the fusion of stem and differentiated cells [

21,

22]. Wei et al. [

23] reported spontaneous heterotypic cell fusions in lung cancer and mice mCSCs, whose progeny exhibited reduced proliferation rate and stemness. Dittmar et al. [

24] also observed stem cell-like features in hybrid cells derived from experimentally fused epithelial breast cells and breast cancer cells.

3.4. Genome reprogramming by precancerous MGRS

As described above, the mechanism of homotypic fusion belongs to an ancient mechanism of regaining genomic integrity. It was evolved by the Urgermline and is inherited in all metazoans and cancer cell systems. However, while the MRGS of protists successfully reorganizes the pre-DSCD genome, pre-cancerous MRGS structures serve reprograming and genome remodeling.

There is little information about precancerous MGRSs. Most data refer to the induction of cancerous PGCCs after irradiation and chemotherapeutic stress, particularly in cancer recurrence and metastases. PGCCs commonly occur in advanced-stage tumors and are associated with poor prognosis.

According to recent work by Liu et al [

25], PGCCs, mostly occurring in hypoxic regions, acquire stemness qualities, which are even more profound in their progeny. In 2016, Niu et al [

26] had the right intuition when they hypothesized that the progeny of precancerous PGCCs acquire a new genome. According to the researchers, the giant cell could be the cell in which genomic changing occurs.

Recent evolutionary cancer genome theory reveals the deep homology between MGRS and PGCC structures [

1]. The non-mutational process of genome reprogramming that occurs in the hyperpolyploid nuclei of precancerous human MGRS cells or the tetraploid nuclei of PGCCs is deeply homologous to the ancient genome repair process evolved by the AMF ancestor discovered in protists. In protists, ancient MGRS, and their hyperpolyploid nuclei restore genome integrity and generate spores and buds that form new germline clones with ACD capability and stemness potential, whereas precancerous MGRS in humans induce reactivation of the ancient AMF gene network, genome hybridization, oncogenesis, and generation of CSCs. In contrast, PGCCs retain the repair potential of protist MGRSs. Therefore, it remains highly questionable whether PGCCs can be considered a "genomically modified embryo" as suggested by the aforementioned investigators [

25,

26].

4.0. Benign tumors

Benign tumors consist of mixed cell phenotypes of different DSCD origin interrupted on the way of oncogenic transformation by genes of tissular development. Genome changing and oncogenic transformation is still pending. Nonetheless, Valet and Narbonne [

27] consider benign tumor cells as dysfunctional non-cancerous cell types capable to complete oncogenic transformation and form malign tumors Benign tumors result by stem cell deregulation [

28,

29]. In early-stage benign tumors, moist cells seemed to be well differentiated and only rarely undifferentaited. This shows that the dysregulation occurred at different stages of stem cell development and under the influence of different stimuli (niche stimuli) and growth factors [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35].

4.1. Niche signaling

Stem cells in the niche are in a quiescent or proliferating SCD state until some of their progeny leave the niche, are not exposed to stress, and differentiate [

32,

36]. In essence, stem cells are “primed” for the ACD phenotype and differentiation. Niche signaling maintains the primed stem cells in either a state of quiescence or symmetric cell cycling with or without defective symmetric cell division. Normally, the niche environment maintains the undifferentiated, undamaged phenotype by preventing ACD differentiation. When Notch signals were blocked, all cells in the niche were rapidly stimulated to differentiate [

37,

38,

39]. According to Valet and Narbonne, two types of niche signals lead to stem cell deregulation and benign tumor formation:: (i)

early constitutive niche signals that lead to undifferentiated tumors, and (ii)

later defective homeostatic signals that lead to differentiated tumors.

4.2. How benign tumors turn malignant

According to Valet and Narbone [

27], benign tumors “acquires changes that disrupt homeostatic SC regulation by their differentiated progeny and prevent proper SC differentiation, respectively SC quiescence“. The authors thought, mutations altering terminal differentiation promote the formation of benign, or aberrantly differentiated tumors. Such mutations would increase SC proliferation, and accelerate their evolution towards cancer. Both reserchers consider transformation of a normal SC into a cancer SC (CSC) as a sequence of genetic and epigenetic changes leading to the acquisition of the multiple cancer hallmarks [

40]. In humans, it typically occurs over several years with multiple intermediate states, showing this progressive deregulation, could be called “pre-cancerous” SCs [

41]. Major proliferative drivers and be responsible for benign tumor formation.

The statement by Valet and Narbone advocating genetic and epigenetic origins of benign tumors is not consistent with the main thrust of the present work, which assumes that stem cell dysregulation and the formation of DSCDs with their ability to give rise to benign growth and tumors is a non-mutational process that does not occur under the effect of random mutations and other genetic events. Neither is it an expression of epigenetic performed cell plasticity. The DSCD phenotype, is no longer a “precancerous stem cell“, but a cell that has lost its ACD potential, stemness, and differentiation. It persists dormant for years in appropriate niches until further appropriate stimuli lead it to cancerous reprogramming via MGRSs. This development follows an archaic cell program founded by the AMF ancestor, hundreds of millions of years ago. That this ancient genome repair program is used by human and metazoan DSCD cells to restore their genome integrity, and paradoxically leads to genome alterations and rearrangements in the spirit of reactivating the ancestral G+S life cycle, is a freak of evolution that inevitably leads to cancer. Mutations are secondary and mostly occur in the somatic cancer cell lines because the aGRN network can not control the hybride genome of somatic cancer cell lines. We have learned, that DCSDs transformation can occur not only in DSCD niches but also in beningn tumors, that also contains non-cancerous DSCD-like cells.

5. Can early pluripotent PSCs experience the DSCD/ MGRS pathway?

There is little data to suggest the emergence of DSCDs or MRGS/PGCCs from PSCs. In contrast, scientists from Jinsong Liu’s research group [

42] assume that PGCCs may represent an important regulator in malignant histogenesis by “abrogating a suppressed pre-embryogenic program“. However, they acknowledge that the role of PGCCs in malignant tumor development and evolution remains largely misunderstood. Accordingly, “

PGCCs represent a stress-induced mechanism that leads to tolerance of massive genomic errors and the creation of a new biological system“ [

43,

44]. According to this view, PGCCs would have unified genomic consequences by “creating altered genome systems ready for cancer macroevolutionary selection, followed by activation of molecular pathways to facilitate subclonal expansion for microevolution“. There is “a

PGCC life cycle in the absence of an activated differentiation program“.

Jinsong Liu, the mentor of this research group, hypothesized that maturation of the blastocyst and its implantation disrupt the embryo’s “germ cell life cycle” and block differentiation of cancer stem cells. In his opinion, as humans age, certain structures formed in the unimplanted blastocyst by de-differentiation of senescent somatic cells and nuclear reprogramming would give rise to a "giant cell-like cycle" and a "neoplastic life code." These “blastomere-like giant cancer cells“ would be the PGCCs that awaken the endogenously-suppressed embryonic program to new life. [

45]

This histopathological interpretation contradicts molecular embryological findings and ignores the evolutionary history of oncogenesis. PGCCs are not a stress-induced mechanism that creates a new biological system, but an ancient genome reconstruction mechanism that repairs genomically damaged CSCs and cancer germline cells [

4,

5,

6]. These cells fuse to form a homotypic syncytium with a greatly hyperpolyploid nucleus that reconstruct genome integrity and form new NG cancer germline clones, which regain ACD and stemness potential and differentiate native CSCs.

The present paper examines whether - and if so, to what extent - the embryological literature confirms Jinsong Liu's assumption. However, no data could be found to support these assumptions. In contrast, not long ago, Ribeiro Reily Rocha et al. [

46] stated that our understanding of the molecular processes associated

with tissue degeneration, and premature aging that occur in patients with deficits in DNA damage repair and responses is “still nebulous“. There is much evidence to suggest that such abnormalities are related to stem cell defects, but the underlying mechanisms are unclear.

5.1. Naive and primed pluripotency

During early embryonic development, a distinction is made between naïve and primed pluripotency. The naïve

state of pluripotency is the pluripotency before the implantation of the blastocyst, and the

primed state of pluripotency is its state afterwards. In other words, the naïve state of pluripotency referred to by Liu [

45] is the pluripotency of the inner cell mass (ICM), while the primed state is the pluripotency of the epiblast. The genomic integrity of both ICM and epiblast is essential for embryonic and fetal development and is protected accordingly [

47].

Mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) derived from early 3.5-day-old ICM could be maintained in culture. They were able to maintain the state of naïve pluripotency but can also transition to primed pluripotency and differentiation into ESCs of lower potency [

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54]. It has been clear that blastocyst pluripotency gives rise to pluripotent ESCs, and after implantation, epiblast cells (EPI cells) develop into somatic cells and primordial germ cells (PGCs), the precursors of sperm and oocyte. Differentiation of somatic cells and PGCs has also been observed in cultures. This shows that the transition from totipotency to naïve pluripotency and further to primed pluripotency is guided and controlled by the epigenome and epigenomic reprogramming [

55]. So far, there is no evidence that under the influence of stressors, PSCs or ESCs can transition to an irreversible damaged DSCD state, fusible cells or MGRS /PGCC-like phenotypes.

As pointed out by Frosina some years ago [

47], the maintenance of genomic stability in PSCs and ESCs is essential, and “genetic alterations in these progenitor cells compromise the genomic stability and functionality of entire cell lineages“. In mice, mutation rates are lower in mESCs than in adult somatic cells due to robust molecular mechanisms and effective DNA damage repair (DDR) that counteract persistent DNA defects and loss of function.

5.2. Molecular mechanisms that prevent DNA damage

S-Phase extension

As stated by Choi et al. [

56], ESCs and their progenitors have unique cell cycle characteristics with a short G1 phase and a prolonged S phase. For example, mice mESCs have a cell division time of approximately 12 hours with an unusually short S phase of only 3 hours. In asynchronous cell cultures more cells spend a longer time in the S phase. The short G1 phase, the lack of a G1/S checkpoint and the prolonged S phase maintain the pluripotent state; PSCs exposed to stress do not persist in the G1 phase and enter the S- phase unimpeded [

57,

58,

59,

60,

61]. In contrast, the prolonged S phase enables error-free DNA DSB repair. Major HR proteins such as RAD51, RAD52, and RAD54 “facilitate efficient replication fork progression by preventing replication fork collapse and repairing DNA breaks during prolonged S phases“ [

62,

63]. In other words, cell cycle regulation mechanisms enable ESCs to tolerate DNA-damaging effects.

The prolonged S phase favors epigenetic regulation and maintenance of genome stability, which may contribute to the stabilization of the pluripotent state It is suggested that proteins that directly regulate DNA replication stabilize pluripotency and the PCS state [

56]. According to Dalton and Coverdell, it is the length of the G1 phase that regulates pluripotency. A prolonged G1 phase inhibits entry into the S phase, disrupts the pluripotent state, and induces differentiation [

64]. ESCs maintain their genome integrity, do not undergo loss of function, and do not transform into defective DSCD-like cell types.

Accumulation of HR factors

Several researchers believe that the constitutive expression and accumulation of HR factors during the extended-S phase is the quintessence of how DNA breaks are prevented and genome integrity is maintained [

56]. It is evidence that impaired HR repair could destabilize the pluripotent state, while the accumulation of HR factors leads to an effective DNA damage response (DDR) and error-free HR repair. In mESCs, the amount of accumulated HR factors is about 6-fold higher than in somatic cells and the number of mutations is much lower than in somatic cells, while genomic stability is higher. It can be said that the increased activity of HR proteins secures both pluripotency and genomic integrity with self-renewal and differentiation

[63,65].

In the absence of HR factors, increased DNA damage leads to loss of genomic integrity and apoptosis.[

66,

67,

68]. When HR factors such as RAD51are depleted, mESCs persist at the S/M checkpoint, and cell death is the dramatic consequence. Abundant HR factors facilitate DNA damage repair [

62]. HR factors decrease continuously during differentiation processes. When differentiation is initiated, mESC cells switch from the HR-mediated repair pathway to NHEJ [

69]. The switch to NHEJ and reduction in HR-related factors lead to inefficient DNA repair and mESCs are no longer able to protect replication forks. This leads to a high frequency of DNA breaks and cell death.

5.3. Less protected: the FA-DNA repair pathway and causes herreditary cancers

Fanconi anemia (FA) is a rare inherited disorder with gene defects in DNA repair linked to the predisposition to develop many different types of hematological cancers, sporadic cancers, and solid tumors [

70]. Gene mutations cause (i) the defective FA phenotype , (ii) genome instability and (iii) additional mutations in their somatic cells. Studies have demonstrated a link between FA and cancer due to gene defects that disrupt the FA DNA-repair pathway.

The low mutation frequency of the pluripotent stem cell state (PSCs) is - at least in part - due to error-free homologous recombination (HR) [

71]. The error-free HR repair pathway requires the so-called Fanconi-anemia DNA repair pathway (FA DANN repair pathway). DNA repair-effector complexes arising from endogenous DNA lesions under the influence of metabolic stressors cause loss-of-function mutations in FA genes, leading to heritable disorders that result in bone marrow failure and developmental defects and pose an increased risk of cancer [

72].

Human iPSCs also require the FA DNA repair pathway. Upon FA-pathway loss, induced iPSCs maintained pluripotency but underwent profound G2 cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. The FA-deficient ESC phenotype can be maintained, they have, however, limited self-renewal. The work of Chlon et al. [

71] indicates that the HR machinery was engaged at DSB in the FA-deficient G2 arrested cells suggesting that HR-mediated repair is stalled in these cells at a stage beyond RAD51 recruitment. iPSCs utilize FA and HR-mediated repair during the G2 phase of the cell cycle, and the inability of FA-deficient iPSCs to repair this damage likely causes G2 arrest [

71]. In FA-deficient iPSCs, unrepaired damage coincides with profound G2 arrest and apoptosis.

As described by researchers, there are 16 till 22 FA genes (FANC) that ensure the maintenance of genomic stability. Mutation in any of the 16 till 22 FA genes causes defects in the response to DNA damage repair (DDR) that result in FA disease [

73,

74]. The FA pathways are the key event in DNA repair and cancer suppression both in inherited and sporadic cancers.

Fanconi anemia patients have a much greater risk of developing acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cancers, in addition to bone marrow failure, including head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in body areas in which cells reproduce rapidly, such as the oral cavity, vulva, esophagus, gastrointestinal tract, and anus (

https://www.fanconi.org/explore/relationship-to-cancer). The incidence of these cancers is 500-700 times greater when compared to the general population

The FA- DNA repair pathway is not limited to PSCs or ESCs, and not induced through specific loss-of-function of embryonic PSCs. It exist in vertebrates, invertebrates, plants, and yeast– on the basis of shared biochemical and physiological functions such as activation of the downstream DNA repair pathway including nucleotide excision repair, translesion synthesis, and homologous recombination [

75].

6. Adult stem cells (ASCs) for DSCD conversion

In the last decade, it was still assumed that oncogenic transformation must result from a progressive accumulation of acquired mutations that age adult stem cells (ASC) or progenitor cells and alter their genomic stability, leading to epigenetic changes and cellular dysfunction [

76,

77,

78,

79,

80] resulting in permanent or transient cell cycle arrest (senescence ) and altruistic suicide. In recent years, however, much data have supported the idea that oncogenic transformation is a non-mutational genome-changing process with an unusual gene regulatory network that allows deregulated somatic mutations. [

1,

3,

4]. Mechanisms that maintain genetic integrity and the factors that alter the genome integrity of the ASC are discussed below.

6.1. Long-term quiescence favour DSCD conversion

Hypoxia prevailing in stem cell niches generally protects ASCs from stressors such as increased oxygen levels and oxidative stress. However, the

lifelong persistence of SCs in a state of quiescence, makes them vulnerable to DNA damage accumulation, cell cycle dysregulation, and loss of function [

81,

82,

83], all of which are characteristic of an incipient DSCD remodeling process. Long-term quiescence has negative consequences: cells miss DNA damage checkpoints and cell cycle repair pathways and have only modest DDR capabilities [

84]. When cells re-enter G1 phase, the long-term DNA damage is repaired only by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), which is less effective than the HR repair mechanisms of the S phase. In contrast, short-time quiescence avoids DNA damage.[

82]. There is a low metabolic activity that provides advantages against DNA damage acquisition

6.2. DSCDs hallmarks: transient senescence, aggressive growth and tumorigenic potential

As reported by Mas-Bargues et al. and other researchers, cellular senescence is a state of permanent or irreversible cell cycle arrest in response to negative stress stimuli such as hyperoxia. [

85]. Though senescent cells are still viable and metabolically active, they are considered unresponsive to mitogenic or oncogenic stimulations and lack the specific functions of adult SC lineages. [

87]. Human SCs cultured at atmospheric oxygen tension (21% O2) exhibit an increase in senescence markers compared to HSCs cultured at low physiological oxygen tension [

87,

88,

89]. Environmental oxygen tension influence the maintenance, survival, and proliferation of stem cells. Cultures with physiological oxygen levels (normoxia) delay senescence, inhibit the senescence-related genes p21 and p16 and prevent cell cycle arrest [

85].

G+

Milanovic et al. [

90] found that cells released from temporary senescence reenter the cell cycle “with strongly enhanced clonogenic growth potential“ compared to virtually identical populations that had been equally exposed to chemotherapy but had never been senescent. The researchers demonstrated that such previously senescent cells have a much higher tumour initiation potential. Cellular senescence, which is implemented in response to severe cellular insults, generate post-senescent cells with a high detrimental potential by driving a much more aggressive growth phenotype.

The author of the present article has not doubt that the post-senescent cells described by Mas-Bargues et al. and Milanovic et al. [

85,

90] are DSCD-like cells that exhibit all the essential features of DSCDs. Unfortunately, both articles do not provide information on how post-senescent cell stages transition to cancer's life cycle. The statements of Milanovic et al. [

90] that (i)

proliferating post-senescent cells are precursors of cancer cells and cancer stem cells (CSCs) and (ii)

senescence-associated stem cells ( SAS) are precursors of tumors are consistent with the main messages of the present work.

7. Germ stem cells (GSCs) for DSCD conversion

It would be expected that human and mammalian germline cells, which are largely related to the Urgermline and not as well protected against DNA damage as pluripotent PSCs and ESCs, could be also dysregulated into DSCDs, similar to stressed adult stem cells (ASCs), as described above.

7.1. Differentiation of primordial germ cells and germline stem cells

Primordial germ cells (PGCs) originate from the 6.5-7.0 day old post-implantation epiblast which is programmed for germ cells rather than somatic cells [

91]. The 6.5-7.0 day old epiblast carries the genetic/epigenetic information for germline specification. According to the researchers, PGC specification has three key events: (i) repression of somatic programming, (ii) regaining of pluripotency, and (iii) genome-wide epigenetic reprogramming

[92]. Primordial germ cells (PGCs) - the precursors of the various maturation stages of germ cell lineages - undergo a process of proliferation and migration from the yolk sac, via the hindgut, towards the genital ridge, where sex determination subsequently occurs [

93]. However, they can also migrate further along the midline of the body, which explains the emergence and topography of extragonadal germ cell tumors (GCTs).

Cheng et al. [

93] refer to germline stem cells (GSCs), as “ the unique cell type that produces more stem cells via self-renewal or different progenitor cells of germline development, and finally differentiate into specialized cells, spermatozoa and ova, for producing offspring“. In mammals, GSCs mainly include (1) primordial germ cells (PGCs) from embryos as embryonic pluripotent stem cells PSCs, (2) induced PGC-like cells (PGCLCs) from embryonic stem cells (ESCs) or induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) as well as (3) spermatogonial stem cells (SSCs), and (4) female germline stem cells (FGSCs).

PGCs are the founder cells of the gonadal germline and the source of totipotency and the formation of new organisms. PGC-like cells can be generated in vitro from embryonic stem cells ESCs or induced pluripotent stem cells iPSC. In vivo, the germline produces germ stem cells (GSC) via long-term mitotic self-renewal.

7.2. Gonadal and extra-gonadal germ cell tumors

Human germ cell tumors (GCTs) are a group of neoplasms of germ cell origin that contain immature and mature elements. They arise mostly in gonads, however, 1–5% of all germ cell tumors have an extragonadal location (E-GCTs) along the midline of the body, where migrating PGCs are located during embryogenesis. It is thought, that extragonal E-GCTs cancers arise from PGCs misplaced to aberrant ectopic sites [

94,

95]. Many of the GCTs are benign.

Several studies have demonstrated the presence of primordial germ cells (PGCs) outside of the gonads long after gonadal differentiation. Interestingly, these extragonadal PGCs do not lose function and can differentiate and mature into oocytes [

96,

97,

98]. They are not irreparable dysfunctional DSCD cells but rather intermediary stages shortly before transition. Other extragonadal germ cells show malignant potential, and the authors believe that "they might have undergone a malignant transformation during embryonic development [

97]. Some investigators believed that extragonadal germ cell tumors EGCTs originated from certain progenitor cells called “carcinoma in situ“ (CIS) or “germ cell neoplasia in situ“ (GCNIS), which represents transformed PGCs or gonocytes [

99].

The author of the present work thinks there is no contradiction in these different statements, because, on their way in oncogenic transformation, the extragonadal germ cells pass through a series of intermediate cell states, from an almost intact extra gonadal cell, which has not yet lost its function, to the dysregulated precursors such as CIS and GCNIS, which have irreversibly lost their cell fate and correspond to DSCD cells. It is evident, that EGCT tumors are not caused by gene mutations, but instead by reprogramming their cells-of-origin in the target niches. Dysregulation of human hPGCs regarding migration, colonization, and differentiation leads to major diseases such as germ cell tumors (GCTs) and ovarian cancer

[100].

As stated by Cheng et al. [

93] the relatively rare extragonadal GCTs “arise in various human organs and tissues for example, brain, head/neck, lung, thymus heart/mediastinum, sacrococcygeal region, abdomen, retroperitoneum, vagina, and placenta, which are also sites of germ cell tumors“. It is widely accepted that extragonadal GCTs cells originating from the

mismigration of hPGCs fail to undergo apoptosis.

7.3. Germ cell tumors (GCTs), dysregulated DSCD pathway and epigenetic controlled plasticity

According to Oosterhuis et al., GCTs are rarely caused by somatic driver mutations but rather by

exogenously induced developmental defects in their cells of origin [

95]. According to these researchers germ cell tumors (GCTs) result from

reprogramming of their cells of origin due to “failures in the cell-intrinsic mechanisms and niche environmental factors, which control cell latent cell developmental potency.“ The

cell of origin is sensitive to DNA damage, can override its control mechanisms, and thereby be reprogrammed into GCTs. This precisely represents the evolutionary pathway through which DSCDs evolve.

Lobo et al. also argue for non-mutagenic evolution, although they assume that "germ cell tumors are not triggered by somatic mutations but by a

defined epigenetic process specific and representative of their cell of origin." [

92] More than 95% of testicular neoplasms originate from germ cells arrested in their differentiation. The researchers believe that errors in the regulation of the developmental potential of ESCs and early PGCs can lead to extragonadal tumors early in life, while deregulation of the developmental potential of later germline cells leads to a variety of tumors preferentially localized in the gonads mainly after childhood.

De Felici et al. also believes that aberrant PGCs arise

without genetic manipulation [

94] and consider that GCT tumors arise (1) either from germ cells that remain incompletely determined in the germline and undergo a dysregulated cell cycle or (2) from germ cells on the way to a somatic differentiation, or (3) from PGCs that do not receive differentiation signals - such as extragonadal PGCs - but remain viable and are prone to oncogenic transformation. Such altered PGCs are largely eliminated from the niche due to the predominant expression of cell death factors, but some of them may also survive for extended periods without differentiation and increase cancer risk.

According to Müller et al., germ cell tumors develop early during specification, migration, or colonization of primordial germ cells (PGCs) in the genital ridge.

[101] It is generally believed that the precursor of GCTs arises during early germ cell development in the fetus until arrival of late PGCs in the gonads. Since driver mutations could not be identified, the authors proposed that the

epigenetic maschinery play also a crucial role. They suggest that SOX2 and SOX17 determine either an embryonic stem cell-like fate (embryonal carcinoma) or a PGC-like cell fate (seminoma) and that factors secreted by the

microenvironment (such as BMPs and BMP inhibiting molecules) dictate the fate decision of germ cell neoplasia in situ, indicating the important role of the microenvironment on GCT plasticity and the transformation of PGCs to GCNIS [

95,

96].

In contrast to the investigators above. the author of the present work work fundamentally differentiates between epigenetic-controlled cell plasticity that allows phenotype reversibility and the irreversibility of DNA damaging processes that lead to DSCD cells and pave the way into ontogenesis. The best example of reversible cell plasticity is the switch from the functional ACD phenotype into the the nomal somatic SCD phenotype. However, when severe stress conditions such as hyperoxia stress the ACD phenotype, a transition into a defective DSCD phenotype with abberrrant cell cycling and loss of stemness and differentiation occurs, and this process is irreversible.

CONCLUSIONS

The present review deepens our understanding of evolutionary cancer cell biology and demonstrates that much of the recent cellular and molecular data supports the evolutionary theory of oncogenesis and its claims. Similar to the discovery of DSCD cells in protists, human non-cancerous DSCD cells lose their ACD, stemness, and differentiation potential, requiring genomic repair. Unrepaired DSCD cells can persist for many years in specific DSCD niches, occasionally proliferating through slow cycling to avoid long-term quiescence, DNA damage, permanent senescence, and altruistic suicide.

In recent years, it has been hypothesized that there is a profound evolutionary relationship between the emergence of new cell types and the ancestral response to stress, and that

the role of stress in evolution can be traced to the emergence of basic cell types in multicellular organisms, namely somatic and germ cells [

102,

103]. According to Nedelcu, "stress induces differentiation of gametes

" in several more evolved unicellular species,

[103]. In contrast, in populations of protists and populations of Urgermline imprint, stress leads to loss of ACD ability with loss of differentiation and stemness potential and dysregulation of the ACD phenotype to DSCD cells [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

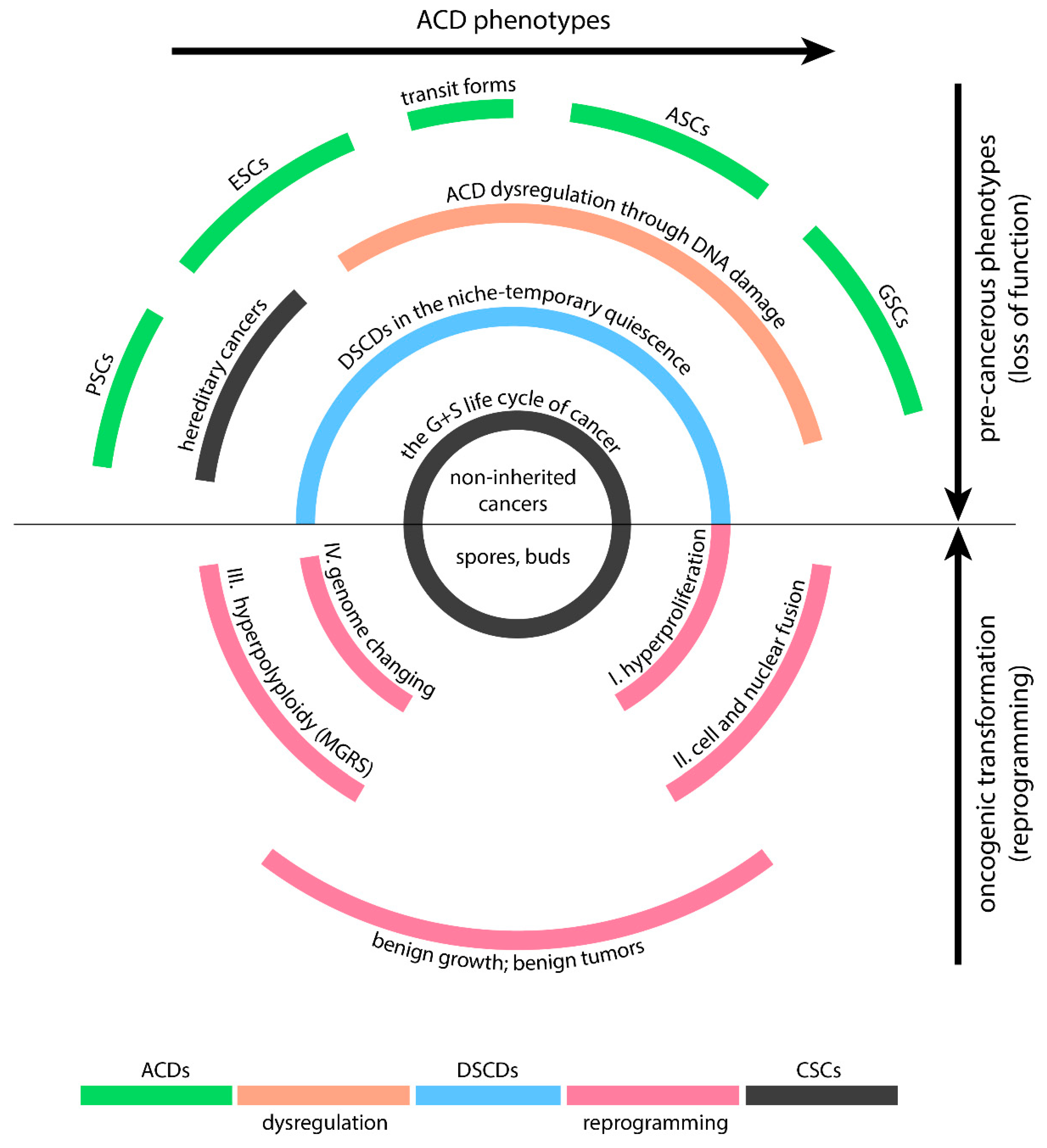

Human DSCDs are derived - at least in cultures - from all ACD cell types, which are capable of stemness and differentiation (

Figure 2). They are the cell-of-origin of cancer.

In vivo, PSCs and ESCs are particularly resistant to DNA damage thanks to better prevention and repair mechanisms and less exposure to stress conditions, such as germline hyperoxia (>6.0% O2). DSCD cells are closely related to the VSEL and EGC phenotypes. All of these phenotypes can be referred to as a family of disrupted ACD phenotypes (DSCD family), which lose genome integrity and cell-fate characteristics, e.g. stemness and differentiation potential, and require repair. Similarly, like their deep homologous DSCD relatives of protists and AMF ancestors, they are tissue-inhabiting relatives of human stem cells, respectively.

Under the control of the aGRN network, all DSCD cells undergo the same cell and nuclear fusion process to form multinucleated genome repair syncytia with hyperpolyploid giant nuclei, but with different outcomes. In protists, MGRS reconstructs the damaged DSCD genome and restores the genomic integrity of the previous ACD phenotype with stemness and differentiation capacity. In humans, MGRS reprograms the DSCD genome and introduce genes from the conserved AMF genome into the hybride genome of cancer. The multi-step DSCD repair process by MGRS drives oncogenesis and genome remodelling.

The hybrid genome of NG germline cells (including CSCs) is fully under the control of the ancestral aGRN regulatory network, but somatic cancer cell lines are not. Dysregulated somatic processes lead to numerous replicative DNA defects and mutations that clearly distinguish somatic cancer cells from normal somatic cells. In tumors and metastases, MGRS-like structures called PGCCs lead to similar repair processes and the formation of CSCs. PGCCs formed during metastasis and recurrence increase stemness and invasion potential.

Much data shows that cells of the deregulated DSCD family have lost their genomic integrity, and cell fate, resulting in defective cell types that require repair. This is the main risk for oncogenesis and cancer. Although in vitro all ACD phenotypes (PSCs, ESCs, ACDs, and GSCs) can generate DSCD cells through deregulation and loss of function, in vivo, ACDs and GSCs usually tend to form DSCDs. PSCs, ESCs, and all other cells of early embryonic life are far too well protected to degenerate into the DSCD state.

When ACD phenotypes are specially protected, as is the case with naïve and primed pluripotent PSCs, DSCD cells are not formed, although these cells also carry the general oxygen sensitivity of the Urgermline within them. Concludently, sporadic solid cancers derived from PSCs are scarcely known, while heritable cancers generated by FA disorders are more common. Defects in the FA DNA repair pathway lead to an FA-deficient ESC phenotype with deep G2 arrest (senescence), and apoptosis. Nevertheless, during pluripotency reduction to ASC and PGC, the genome integrity of the transit cell forms is no longer as well protected: stress and replication defects lead to loss of stemness and differentiation, giving rise to DSCD cells.

The dysfunctional DSCD in need of repair is the cell-of-origin of sporadic cancers, which are not genetic but rather non-mutational. Cancer is paradoxically caused by an inadequate repair program conserved in human and metazoan genomes. The MGRS repair program sometimes occurs many years later and affects niche DSCD cells. However, the MGRS mechanism is unable to restore the previous ACD genome, and the MGRS progeny gets a hybrid genome consisting of DSCD genes and genes of the conserved AMF ancestor, all controlled by the ancestral aGRN network. Spores and buds formed by the MGRS mechanism initiate the germ and soma (G+S) life cycle of cancer and generate naïve CSCs.

In summary, present data show that oncogenesis is a non-mutational reprogramming process of ancestral imprinting that forms an NG cancer germline and naïve CSCs homologous to the ancient uGSCs stem cells.

Acknowledgments

This work and all the previous works of the last 10 years would not have been possible without the permanent support and understanding of my family, who have freed me from the burdens of daily life and allowed me the peace for scientific work and reflection. Special thanks to my wife, the German microbiologist Dr. Eugenia R. Niculescu, who has always accompanied my scientific work and made professional suggestions. Special thanks go to Mr. Gregor Jaruga, who has designed the illustrations of my publications over many years with excellent graphic work.

Abbreviations

ACD, asymmetric cell division; AMF, amoebozoans, metazoans and fungi; ASC, adult stem cell; CSC, cancer stem cell; DDR, DNA damage response; DSB, double strand break; DSCD, damaged cell capable of symmetric cell division; ESC, embryonic stem cell; EGC, extragonadal germ cell; EGCT, extragonadal germ cell tumor; FA, Fanconi anaemia; aGRN, ancestral gene regulatory network; aGSC, ancestral germline stem cell; mGSC, mammalian germ stem cell; GST, germ stem tumor; HR, homologous recombination; HRD, HR deficiency; MGRS, multinucleated genome repair syncytia; NG, non-gametogenic; PGC, primordial germ cell; PGCC, polyploid giant cancer cell; PSC, pluripotent stem cell; RGN, regulatory gene network; SC, stem cell; SCD, symmetric cell division; SGT, soma-to-germ transition; VSEL, very small embryonic like cells.

References

- Niculescu, V.F. ; The evolutionary cancer genome theory and ist reasoning. Genet Med Open. 2023, 1, 100809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, V.F. ; Cancer genes and cancer stem cells in tumorigenesis: evolutionary deep homology and controversies. Genes Dis. 2022, 9, 1234e1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, V.F. ; Cancer exploits a late premetazoan gene module conserved in the human genome, Genes & Diseases, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, V.F. ; Attempts to restore loss of function in damaged ACD cells open the way to non-mutational oncogenesis. Genes Dis. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, V.F. ; The evolutionary cancer gene network theory versus embryogenichypotheses. Medical Oncology, 2023, 40, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niculescu, V.F. ; On the role of polyploid giant cells in oncogenesis and tumorigenesis. Medical Oncology, 2023, 40, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barati, M.; Akhondi, M.; Mousavi, N.S.; Haghparast, N.; Ghodsi, A.; et al. Pluripotent Stem Cells: Cancer Study, Therapy, and Vaccination. Stem Cell Rev Rep, 2021, 17, 1975–1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.M.; Liu, R.; Klich, I.; Wu, W.; Ratajczak, J.; et al. Molecular signature of adult bone marrow-purified very small embryonic-like stem cells supports their developmental epiblast/germ line origin. Leukemia 2010, 24, 1450–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, M. Z.; Ratajczak, J.; Kucia, M. Very Small Embryonic-Like Stem Cells (VSELs). Circulation Research. 2019, 124, 208–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuba-Surma EK, Wojakowski W, Ratajczak MZ, Dawn B. Very small embryonic-like stem cells: biology and therapeutic potential for heart repair. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 1821–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, M,Z. ; Bujko, K.; Mack, A.; Kucia, M.; Ratajczak, J.; Cancer from the perspective of stem cells and misappropriated tissue regeneration mechanisms. Leukemia. 2018, 32, 2519–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-López, S.; Lerner, R.G.; Petritsch, C. ; Asymmetric cell division of stem and progenitor cells during homeostasis and cancer. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2014, 71, 575–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrai,l D; Chun-Jen Lin, C.; Dai, H.; Mo,W.; Li,Y. Defective Replication Stress Response Is Inherently Linked to the Cancer Stem Cell Phenotype. Cell Reports 2018, 23(7), 2095–2106. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, C.T.; Guzman. M.L.; Noble, M. Cancer stem cells. N Engl J Med. 2006, 355, 1253–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peters, J. The role of genomic imprinting in biology and disease: An expanding view. Nature Reviews Genetics, 2014, 15, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, E.; Rajendra, J.; Jadhav, S.; Shridhar, E.; Goda, J.S.; et al. Radiation-induced homotypic cell fusions of innately resistant glioblastoma cells mediate their sustained survival and recurrence. Carcinogenesis. 2015, 36, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, S.; Mercado-Uribe, I.; Xing, Z.; Sun, B.; Kuang, J.; Liu, J. Generation of cancer stem-like cells through the formation of polyploid giant cancer cells. Oncogene. 2014, 33, 116–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barok, M.; Tanner, M.; Koninki, K.; Isola, J. Trastuzumab-DM1 causes ¨ tumour growth inhibition by mitotic catastrophe in trastuzumabresistant breast cancer cells in vivo. Breast Cancer Res 2011, 13, R46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malpica, A.; Deavers, M.T.; Lu, K.; Bodurka, D.C.; Atkinson, E.N.; et al. Grading ovarian serous carcinoma using a two-tier system. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004, 28, 496–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Ma, H.; Yang, X.; Fan, L.; Tian, S.; et al. Cell Fusion-Related Proteins and Signaling Pathways, and Their Roles in the Development and Progression of Cancer. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2022, 9, 809668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.F.; Xiang, W.; Xue, B.Z.; Wang, Y.H.; Yi, D.Y.; et al. F.; Xiang, W.; Xue, B.Z.; Wang, Y.H.; Yi, D.Y.; et al. Cell fusion in cancer hallmarks: Current research status and future indications. Oncol Lett. 2021, 22, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dittmar, T.; Nagler, C.; Schwitalla, S.; Reith, G.; Niggemann, B.; Zänker, K.S. Recurrence cancer stem cells-made by cell fusion? Med Hypotheses. 2009, 73, 542–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wie, H.J.; Nickoloff, J.A.; Chen, W.H.; Liu, H.Y.; Lo, W.C.; et al. FOXF1 mediates mesenchymal stem cell fusion-induced reprogramming of lung cancer cells. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 9514–9529. [Google Scholar]

- Dittmar, T.; Schwitalla, S.; Seidel, J.; Haverkampf, S.; Reith, G.; et al. Characterization of hybrid cells derived from spontaneous fusion events between breast epithelial cells exhibiting stem-like characteristics and breast cancer cells. Clin Exp Metastas. 2011, 28, 75–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wu, M.; Liu, J.; Wu, H.; et al. Hypoxia-induced polypoid giant cancer cells in glioma promote the transformation of tumor-associated macrophages to a tumor-supportive phenotype. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2022, 28, 1326–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, N.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, N.; Mercado-Uribe. I; Tao, F.; et al. Linking genomic reorganization to tumor initiation via the giant cell cycle. Oncogenesis. 2016, 5, e281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valet, M.; Narbonne, P. ; Formation of benign tumos by stem cell deregulation. PLoS Genet. 2022, 18, e1010434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphries, A.; Cereser, B.; Gay, L.J.; Miller, DS.; Das, B.; et al. Lineage tracing reveals multipotent stem cells maintain human adenomas and the pattern of clonal expansion in tumor evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013, 110, E2490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, S.; Chen, WD.; Parmigiani, G.; Diehl, F.; Beerenwinkel, N.; Antal, T.; et al. Comparative lesion sequencing provides insights into tumor evolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008, 105, 4283–4288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, H.; Bao, D.; Tong, X.; Hu, Q.; Sun, G.; Huang, X. ; The role of stem cells in benign tumors. Tumour Biol. 2016. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Tian, A.; Jiang, J. Intestinal stem cell response to injury: lessons from Drosophila. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016, 73, 3337–3349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, S.J.; Kimble, J. Asymmetric and symmetric stem-cell divisions in development and cancer. Nature. 2006, 441, 1068–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison, S.J.; Spradling, A.C. Stem cells and niches: mechanisms that promote stem cell maintenance throughout life. Cell. 2008, 132, 598–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narbonne, P.; Roy, R. Regulation of germline stem cell proliferation downstream of nutrient sensing. Cell Div. 2006, 1, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shim, J.; Gururaja-Rao, S.; Banerjee, U. Nutritional regulation of stem and progenitor cells in Drosophila. Development. 2013, 140, 4647–4656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Garcia, C.; Klein, A.M.; Simons, B.D.; Winton, D.J. Intestinal stem cell replacement follows a pattern of neutral drift. Science. 2010, 330, 822–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimble, J.E.; White, J.G. On the control of germ cell development in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1981, 81, 208–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J.; Kimble, J. glp-1 is required in the germ line for regulation of the decision between mitosis and meiosis in C. elegans. Cell. 1987, 51, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henderson, S.T.; Gao, D.; Lambie, E.J.; Kimble, J. lag-2 may encode a signaling ligand for the GLP-1 and LIN-12 receptors of C. elegans. Development. 1994, 120, 2913–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanahan, D. Hallmarks of Cancer: New Dimensions. Cancer Discov. 2022, 12, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, M.; Mitrou, P.S.; Hubner, K. Proliferative activity of undifferentiated cells (blast cells) in preleukaemia. Acta Haematol. 1976, 55, 148–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X. , Zhong, Y., Zhang, X., Sood, A.K.; Liu, J. Spatiotemporal view of malignant histogenesis and macroevolution via formation of polyploid giant cancer cells. Oncogene 2023, 42, 665–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heng, H.H. Genomic chaos: rethinking genetics, evolution, and molecular medicine. Academic Press, 2019.

- Heng, J. , Heng, H.H. Genome chaos: creating new genomic information essential for cancer macroevolution. Semin Cancer Biol. 2022, 81, 160–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J. The “life code”: a theory that unifies the human life cycle and the origin of human tumors, Seminars in Cancer Biology. 2019.

- Rocha, C.R.R. , Lerner, L.K., Okamoto, O.K.,Marchetto, M.C., Menck C.F.M. The role of DNA repair in the pluripotency and differentiation of human stem cells. Mutat Res. 2013, 752, 25–35. [Google Scholar]

- Frosina, G. The bright and the dark sides of DNA repair in stem cells. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2010, 845396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devika, A.S.; Montebaur, A.; Saravanan, S.; Bhushan, R.; Koch, F. et al. Human ES Cell Culture Conditions Fail to Preserve the Mouse Epiblast State. Stem Cell International, Hindawi. 2021, 8818356.

- Brons, L.E. , Smithers, M.W.B. Trotter et al. Derivation of pluripotent epiblast stem cells from mammalian embryos. Nature 2007, 448, 191–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesar, P. J.; Chenoweth, J. G.; Brook, F. A.; Davies, T.J.; Evans, E.P.; et al. , “New cell lines from mouse epiblast share defining features with human embryonic stem cells,” Nature. 2007, 448, 196–199. [Google Scholar]

- Ying, Q.L.; Wray, J.; Nichols, J.; Batlle-Morera, L.; Doble, B. et al., “The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal,” Nature. 2008, 453, 519–523. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, G.; Yang, J.; Nichols, J.; Hall, J.S.; Eyres, I. et al. Klf4 reverts developmentally programmed restriction of ground state pluripotency,” Development, 2009, 136, 1063–1069. 2009, 136, 1063–1069. [Google Scholar]

- Tosic, J.; Kim, G.J.; Pavlovic, M.; Schröder, C.M. Eomes and Brachyury control pluripotency exit and germ-layer segregation by changing the chromatin state. Nature Cell Biology 2019, 21, 1518–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y. ; Tanaka,T.S. Self-Renewal, Pluripotency and Tumorigenesis in Pluripotent Stem Cells Revisited. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reik, W.; Azim Surani, M. Germline and Pluripotent Stem Cells. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2015, 7, 019422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, E.H; Yoon, S. ; Koh,Y.E.; Seo, Y.J, Kim K.P. Maintenance of genome integrity and active homologous recombination in embryonic stem cells. Experimental & Molecular Medicine. 2020, 52, 1220–1229. [Google Scholar]

- Ahuja, A.K.; Jodkowska, K.; Teloni, F.; Bizard, A.H.; Zellweger, R.; et al. A short G1 phase imposes constitutive replication stress and fork remodelling in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nat. Commun. 2016, 15, 10660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauklin, S.; Madrigal, P. ; Bertero, A; Vallie, R.L. Initiation of stem cell differentiation involves cell cycle-dependent regulation of developmental genes by cyclin D. Genes Dev. 2016, 30, 421–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Michowski, W.; Inuzuka, H.; Shimizu, K.; Nihira, N.T.; et al. G1 cyclins link proliferation, pluripotency and differentiation of embryonic stem cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 2017, 19, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boward, B. , Wu, T; Dalton, S. Concise review: control of cell fate through cell cycle and pluripotency networks. Stem Cells. 2016, 34, 1427–1436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suvorova, ES.; Francia, M.; Striepen, B.; White, M.W. A novel bipartite centrosome coordinates the apicomplexan cell cycle. Plos Biol. 2015, 13, e1002093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.H.; Yoon, S.; Kim, K.P. Combined ectopic expression of homologous recombination factors promotes embryonic stem cell differentiation. Mol. Ther. 2018, 26, 1154–1165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, E.H.; Yoon, S.; Park, K.S.; Kim, K.P. The homologous recombination machinery orchestrates post-replication DNA repair during self-renewal of mouse embryonic stem cells. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 11610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalton, S.; Coverdell, P. Linking the cell cycle to cell fate decisions. Trends Cell Biol. 2015, 25, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tichy, E.D.; Stambrook, P.J. DNA repair in murine embryonic stem cells anddifferentiated cells. Exp. Cell Res. 2008, 314, 1929–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dannenmann, B. , Lehle, S., Hildebrand, D.G., Kubler, A., Grondona, P.; et al. High glutathione and glutathione peroxidase-2 levels mediate cell-type-specific DNA damage protection in human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2015, 4, 886–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Momcilovic, O. , Knobloch, L., Fornsaglio, J., Varum, S., Easley, C., Schatten, G. DNA damage responses in human induced pluripotent stem cells and embryonic stem cells. PLoS One 2010, 5, e13410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, L. , Liang, L., Chang, Y., Deng, L., Maulion, C. et al. (2011). Homologous recombination conserves DNA sequence integrity throughout the cell cycle in embryonicstem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2011, 20, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stambrook, P.J.; Tichy, E.D. Preservation of genomic integrity in mouse embryonic stem cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010, 695, 59–75. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Zhang, S.; Wu, Z. Fanconi anemia pathway defects in inherited and sporadic cancers. Translational Paediatrics. 2014, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Chlon, T.M.; Ruiz-Torres, S.; Maag, L.; Mayhew, C.N.; Wikenheiser-Brokamp, K.A.; et al. Overcoming Pluripotent Stem Cell Dependence on the Repair of Endogenous DNA Damage. Stem Cell Reports. 2016, 6, 44–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auerbach, A.D. Fanconi anemia and its diagnosis. Mutat. Res. 2009, 668, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akkari, Y.M.; Bateman, R.L.; Reifsteck, C.A.; Olson, S.B.; Grompe, M. DNA replication is required to elicit cellular responses to psoralen-induced DNA interstrand cross-links. Mol Cell Biol 2000, 20, 8283–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, C.; Pei, H.; Zhang, B.; Xuan Zheng, X.; Dongmei Ran, D.; et al. Fanconi anemia pathway and its relationship with cancer. Genome Instability & Disease. 2021, 2, 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H.; Nebert, D.W.; Bruford, E.A.; Thompson, D.C.; Joenje, H.; Vasiliou, V. Update of the human and mouse Fanconi anemia genes. Hum Genomics 2015, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez, L.M.; de Lucas, B.; Gálvez, B.G. Unhealthy Stem Cells: When Health Conditions Upset Stem Cell Properties. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018, 46, 1999–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burkhalter, M.D.; Rudolph, K.L.; Sperka, T. Genome instability of ageing stem cells–Induction and defence mechanisms. Ageing Res Rev 2015, 23, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krauss, S.R.; de Haan, G. Epigenetic perturbations in aging stem cells. Mamm Genome 2016, 27, 396–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlqvist, K.J.; Suomalainen, A.; Hamalainen, R.H. Stem cells, mitochondria and aging. Biochim Biophys Acta 2015, 1847, 1380–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, T.; Thuret, S. The systemic milieu as a mediator of dietary influence on stem cell function during ageing. Ageing Res Rev 2015, 19, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morikawa, T. ; Takubo, K: Hypoxia regulates the hematopoietic stem cell niche. Pflugers Arch. 2015, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, M.H. Changes in Regenerative Capacity through Lifespan. Int J Mol Sci 2015, 16, 25392–25432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, P.K.; Blanpain, C.; Rossi, D.J. DNA damage response in adult stemcells: pathways and consequences. Nature reviews, Molecular cell Biology. 2011, 201. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo, M.; Wagers, A.J.; Manz, M.G.; Prohaska, S.S.; Scherer, D.C.; et al. Biology of hematopoietic stem cells and progenitors: implications for clinical application. Annu Rev Immunol 2003, 21, 759–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mas-Bargues, C, Sanz-Ros, J, Román-Domínguez, A, Inglés M, Gimeno-Mallench, L.;et al. Relevance of Oxygen Concentration in Stem Cell Culture for Regenerative Medicine. Int J Mol Sci. 2019, 20, 1195. [CrossRef]

- Yeh, C.K. Cellular senescence and aging. Oral Dis. 2016, 22, 587–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.S.; Ko, Y.J.; Lee, M.W.; Park, H.J.; Park, Y.J.; et al. Effect of low oxygen tension on the biological characteristics of human bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Stress Chaperones 2016, 21, 1089–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsai, C.C.; Chen, Y.J.; Yew, T.L.; Chen, L.L.; Wang, J.Y.; et al. Hypoxia inhibits senescence and maintains mesenchymal stem cell properties through down-regulation of E2A-p21 by HIF-TWIST. Blood 2011, 117, 459–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vono, R.; Jover Garcia, E.; Spinetti, G.; Madeddu, P. Oxidative Stress in Mesenchymal Stem Cell Senescence: Regulation by Coding and Noncoding RNAs. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 29, 864–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milanovic, M, Fan, DNY, Belenki, D, Däbritz, JHM, Zhao, Z et al. Senescence-associated reprogramming promotes cancer stemness. Nature, 2017, 553, 96–100.

- Yao, C.; Yao, R.; Luo, H.; Shuai, L. Germline specification from pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Research & Therapy. 2022, 13, 72. [Google Scholar]

- Lobo, J.; Gillis, A.J.M.; Jerónimo, C.; Henrique, R.; Looijenga, L.H.J. Human Germ Cell Tumors are Developmental Cancers: Impact of Epigenetics on Pathobiology and Clinic. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.; Shang, D.; Zhou, R. Germline stem cells in humans. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2022, 7, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Felici, M.; Klinger, F.G.; Campolo, F.; Balistreri, C.R.; Barchi, M.; Dolci, S. To Be or Not to Be a Germ Cell: The Extragonadal Germ Cell Tumor Paradigm. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oosterhuis, J.W.; Looijenga, L.H.J. Human germ cell tumours from a developmental perspective. Nat Rev Cancer. 2019, 19, 522–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teilum, G. Classification of endodermal sinus tumour (mesoblatoma vitellinum) and so-called “embryonal carcinoma” of the ovary. Acta Pathol. Microbiol. Scand. 1965, 64, 407–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrobel, K.H.; Suss, F. Identification and temporospatial distribution of bovine primordial germ cells prior to gonadal sexual differentiation. Anat. Embryol. 1998, 197, 451–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, I.N. Primordial germ cells are capable of producing cells of the hematopoietic system in vitro. Blood 1995, 86, 463–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berney, D.M.; Looijenga, L.H.; Idrees, M.; Oosterhuis, J.W.; Rajpert-De Meyts, E.; et al. Germ cell neoplasia in situ (GCNIS): Evolution of the current nomenclature for testicular pre-invasive germ cell malignancy. Histopathology. 2016, 69, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, R. L.; Miller, K. D.; Fuchs, H. E.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA: A Cancer J. Clin. 2022, 72, 7–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, M. R.; Skowron, M. A.; Albers, P.; Nettersheim, D. Molecular and epigenetic pathogenesis of germ cell tumors. Asian Journal of Urology, 2021, 8, 144–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, G.P.; Erkenbrack, E.M.; Love, A.C. Stress-Induced EvolutionaryInnovation: A mechanism for the origin of cell types. Bioessays. 2019, 41, e1800188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedelcu, A.M.; Michod, R.E. Stress responses co-opted for specialized cell types during the early evolution of multicellularity. Bioassay 2020, 42, e2000029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).