Submitted:

22 August 2023

Posted:

24 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Site

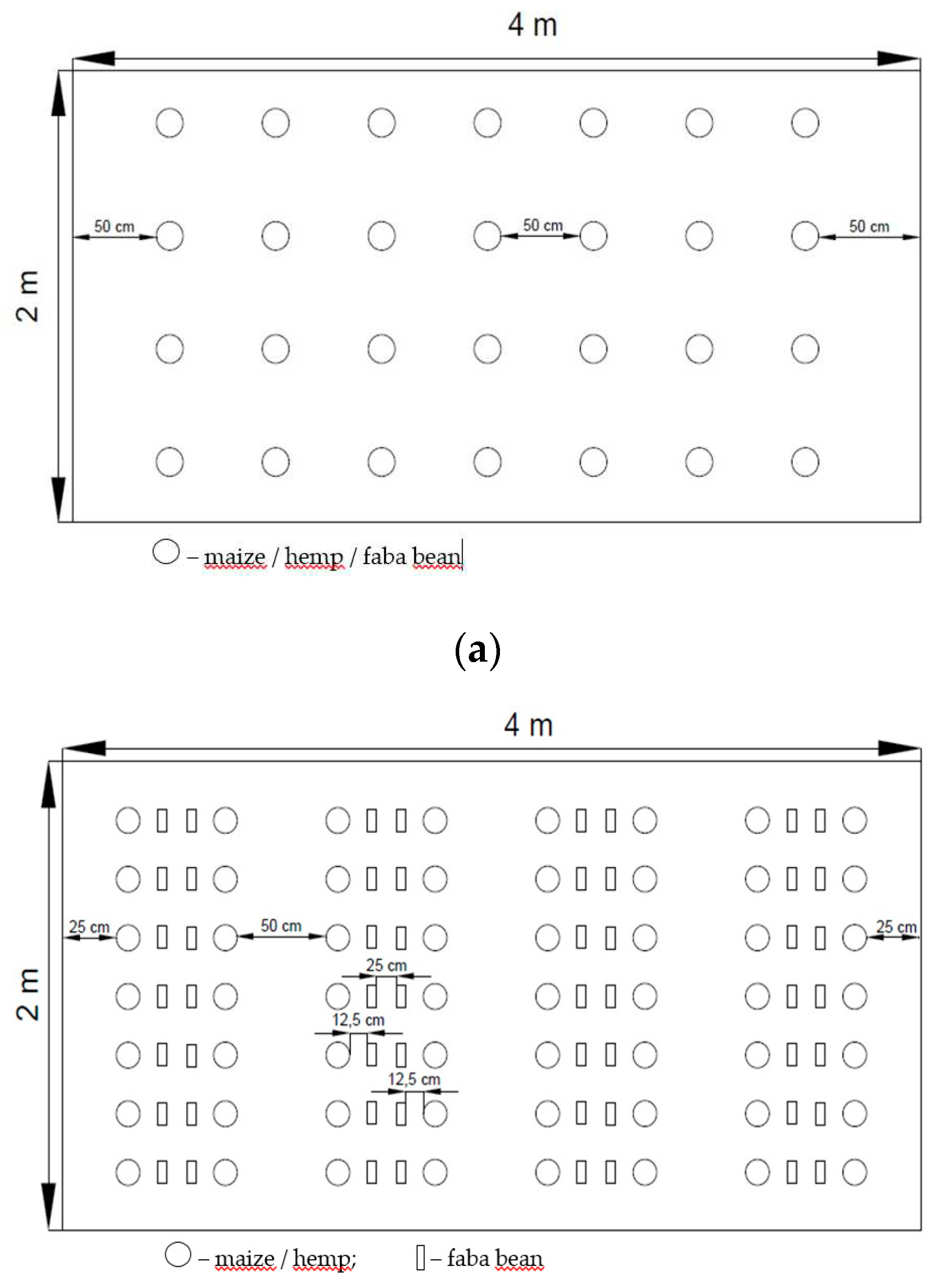

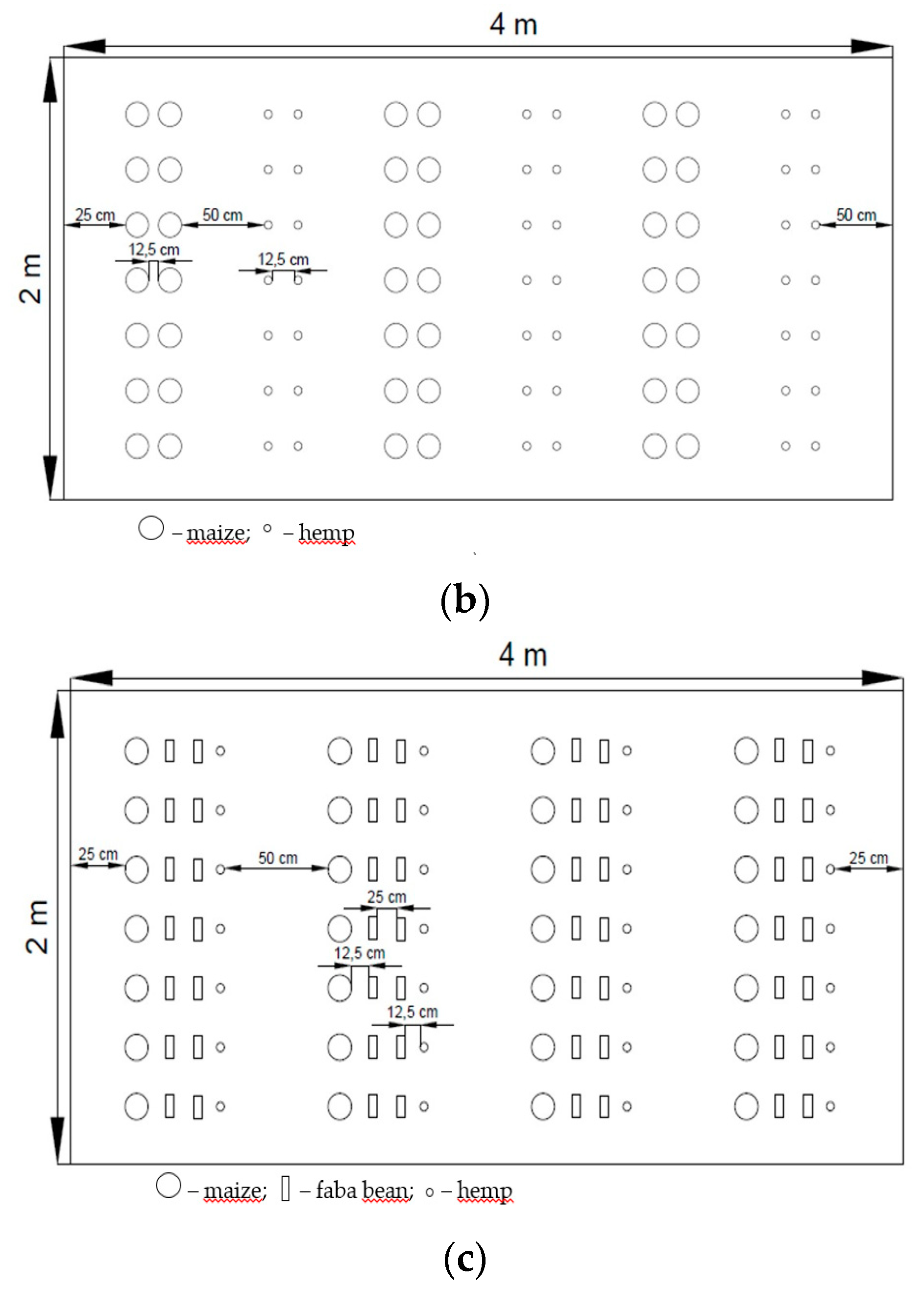

2.2. Treatments and Agronomic Practice

2.3. Methodology

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Energy Inputs

3.2. Biomass Yields

3.3. Fuel Consumption and Energy Indices

3.4. Environmental Impact

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ioelovich, M. Energetic Potential of Plant Biomass and Its Use. Int. J. Renew. Sustain. Energy 2013, 2, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Lara, S.; Serna-Saldivar, S.O. Chemistry and Technology. Corn. 2019, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Abukhadra, M.R.; Adlii, A.; Jumah, M.N.B.; Othman, S.; Alruhaimi, R.S.; Salama, Y.F.; Allam, A.A. Sustainable conversion of waste corn oil into biofuel over different forms of synthetic muscovite based K+/Na+ sodalite as basic catalysts; characterization and mechanism. Materials Research Express 2021, 6, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Ryu, Y.; Dechant, B.; Berry, J.A.; Hwang, Y.; Jiang, C.; Kang, M.; Kim, J.; Kimm, H.; Kornfeld, A.; et al. Sun-induced chlorophyll fluorescence is more strongly related to absorbed light than to photosynthesis at half-hourly resolution in a rice paddy. Remote. Sens. Environ. 2018, 216, 658–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saghaian, S.; Nemati, M.; Walters, C.; Chen, B. Asymmetric Price Volatility Transmission between U. S. Biofuel, Corn, and Oil Markets. Journal of Agricultural and Resource Economics 2018, 43, 46–60. [Google Scholar]

- Romaneckas, K.; Balandaitė, J.; Sinkevičienė, A.; Kimbirauskienė, R.; Jasinskas, A.; Ginelevičius, U.; Romaneckas, A.; Petlickaitė, R. Short-Term Impact of Multi-Cropping on Some Soil Physical Properties and Respiration. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frankowski, J.; Sieracka, D. Possibilities for Using Waste Hemp Straw for Solid Biofuel Production. EWaS5 2021, 9, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crini, G.; Lichtfouse, E.; Chanet, G.; Morin-Crini, N. Applications of hemp in textiles, paper industry, insulation and building materials, horticulture, animal nutrition, food and beverages, nutraceuticals, cosmetics and hygiene, medicine, agrochemistry, energy production and environment: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2020, 18, 1451–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberl, H.; Erb, K.-H.; Krausmann, F.; Bondeau, A.; Lauk, C.; Müller, C.; Plutzar, C.; Steinberger, J.K. Global bioenergy potentials from agricultural land in 2050: Sensitivity to climate change, diets and yields. Biomass- Bioenergy 2011, 35, 4753–4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Canqui, H.; Ruis, S.J. Cover crop impacts on soil physical properties: A review. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2020, 84, 1527–1576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, C.A.; Porter, P. Multicropping. Crop Systems 2016, 3, 29–33. [Google Scholar]

- Beaumelle, L.; Auriol, A.; Grasset, M.; Pavy, A.; Thiéry, D.; Rusch, A. Author response for "Benefits of increased cover crop diversity for predators and biological pest control depend on the landscape context". 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Failla, S.; Ingrao, C.; Arcidiacono, C. Energy consumption of rainfed durum wheat cultivation in a Mediterranean area using three different soil management systems. Energy 2020, 195, 116960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šarauskis, E.; Buragienė, S.; Masilionytė, L.; Romaneckas, K.; Avižienytė, D.; Sakalauskas, A. Energy balance, costs and CO2 analysis of tillage technologies in maize cultivation. Energy 2014, 69, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbarnia, A.; Farhani, F. Study of fuel consumption in three tillage methods. Res. Agric. Eng. 2014, 60, 142–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paris, B.; Vandorou, F.; Balafoutis, A.T.; Vaiopoulos, K.; Kyriakarakos, G.; Manolakos, D.; Papadakis, G. Energy use in open-field agriculture in the EU: A critical review recommending energy efficiency measures and renewable energy sources adoption. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 158, 112098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, N.; Audsley, E.; Brodt, S.; Garnett, T.; Henriksson, P.; Kendall, A.; Kramer, K.J.; Murphy, D.; Nemecek, T.; Troell, M. Energy Intensity of Agriculture and Food Systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2011, 36, 223–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazvineh, S.; Yousefi, M. Evaluation of consumed energy and greenhouse gas emission from agroecosystems in Kermanshah province. Technical Journal of Engineering and Applied Sciences 2013, 3, 349–354. [Google Scholar]

- Trimpler, K.; Stockfisch, N.; Märländer, B. The relevance of N fertilization for the amount of total greenhouse gas emissions in sugar beet cultivation. Eur. J. Agron. 2016, 81, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lal, R. Carbon emission from farm operations. Environ. Int. 2004, 30, 981–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangalassery, S.; Sjögersten, S.; Sparkes, D.L.; Mooney, S.J. Examining the potential for climate change mitigation from zero tillage. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 153, 1151–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adewale, C.; Reganold, J.P.; Higgins, S.; Evans, R.; Carpenter-Boggs, L. Improving carbon footprinting of agricultural systems: Boundaries, tiers, and organic farming. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2018, 71, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bručienė, I.; Aleliūnas, D.; Šarauskis, E.; Romaneckas, K. Influence of Mechanical and Intelligent Robotic Weed Control Methods on Energy Efficiency and Environment in Organic Sugar Beet Production. Agriculture 2021, 11, 449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. World Reference Base for Soil Resources 2014, International Soil Classification System for Naming Soils and Creating Legends for Soil Maps. 2015. Available online: http://www.fao.org/3/i3794en/I3794en.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2020).

- Pagrindinio žemės dirbimo darbai/Primary tillage works. Mechanizuotų žemės ūkio paslaugų įkainiai. Rates for mechanized agricultural services; Srebutėnienė, I., Ed.; Lietuvos agrarinės ekonomikos institutas: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2017; Available online: https://zum.lrv.lt/uploads/zum/documents/files/IKAINIAI_2017_I_dalis.pdf(in Lithuanian). (accessed on 2023 August 2023). (in Lithuanian)

- Pasėlių priežiūra ir šienapjūtės darbai/Crop care and mowing work. In Mechanizuotų žemės ūkio paslaugų įkainiai. Rates for mechanized agricultural, services; Srebutėnienė, I.; Stalgienė, A. (Eds.) Pasėlių priežiūra ir šienapjūtės darbai/Crop care and mowing work. In Mechanizuotų žemės ūkio paslaugų įkainiai. Rates for mechanized agricultural services; Srebutėnienė, I.; Stalgienė, A., Eds.; Lietuvos agrarinės ekonomikos institutas: Vilnius, Lithuania, 2017 (in Lithuanian).

- Patent LT6701B. Faba Bean Waste Biofuel Pellets And/Or Sorbent, Fertilizer. Available online: https://search.vpb.lt/pdb/patent/dossier/5140/text (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- Patent LT6998B. Corn, Hemp And Bean Multi-Crop Biomass Pellets And/Or Fertilizer. Available online: https://search.vpb.lt/pdb/patent/dossier/48325/text (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- Lal, B.; Gautam, P.; Nayak, A.; Panda, B.; Bihari, P.; Tripathi, R.; Shahid, M.; Guru, P.; Chatterjee, D.; Kumar, U.; et al. Energy and carbon budgeting of tillage for environmentally clean and resilient soil health of rice-maize cropping system. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šarauskis, E.; Romaneckas, K.; Jasinskas, A.; Kimbirauskienė, R.; Naujokienė, V. Improving energy efficiency and environmental mitigation through tillage management in faba bean production. Energy 2020, 209, 118453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todde, G.; Carboni, G.; Marras, S.; Caria, M.; Sirca, C. Industrial hemp (Cannabis sativa L.) for phytoremediation: Energy and environmental life cycle assessment of using contaminated biomass as an energy resource. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assessments 2022, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemi, H.; Shahbyki, M.; Baghbani, S. Energy analysis for faba bean production: A case study in Golestan province, Iran. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2015, 3, 15–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amir, S.; Hemp as a biomass crop. Technical Article, April 2023. Available online: https://www.biomassconnect.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/Hemp-as-Biomass-Crop.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- Kraszkiewicz, A.; Kachel, M.; Parafiniuk, S.; Zając, G.; Niedziółka, I.; Sprawka, M. Assessment of the Possibility of Using Hemp Biomass (Cannabis Sativa L.) for Energy Purposes: A Case Study. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasinskas, A.; Minajeva, A.; Šarauskis, E.; Romaneckas, K.; Kimbirauskienė, R.; Pedišius, N. Recycling and utilisation of faba bean harvesting and threshing waste for bioenergy. Renew. Energy 2020, 162, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabar, I. B; Keyhani, A; Rafiee, S. Energy balance in Iran’s agronomy (1990-2006). Renew. Sustain. Energy. Rev. 2010, 14, 849–55. [Google Scholar]

- Moghimi, M.R.; Pooya, M.; Mohammadi, A. Study on energy balance, energy forms and greenhouse gas emission for wheat production in Gorve city, Kordestan province of Iran Eur. J. Exp. Biol. 2014. 4, 234–239.

- Pishgar-Komleh, S.; Ghahderijani, M.; Sefeedpari, P. Energy consumption and CO2 emissions analysis of potato production based on different farm size levels in Iran. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 33, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Mittal, J.P.; Verma, S.R. Energy requirements for production of major crops in India. Agric. Mech. Asia Africa Latin. Am. 1997, 28, 13–17. [Google Scholar]

- Campiglia, E.; Gobbi, L.; Marucci, A.; Rapa, M.; Ruggieri, R.; Vinci, G. Hemp Seed Production: Environmental Impacts of Cannabis Sativa L. Agronomic Practices by Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Carbon Footprint Methodologies. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckmann, K.; Blank, R.; Traulsen, I.; Krieter, J. Comparative life cycle assessment (LCA) of pork using different protein sources in pig feed. Arch. Anim. Breed. 2016, 59, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Özçatalbaş, O.; Bashir, M.K. Estimation of energy efficiency and greenhouse gas emission of cotton crop in South Punjab, Pakistan. J. Saudi Soc. Agric. Sci. 2018, 19, 216–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomic, M.; Savin, L.; Micic, R.; Simikic, M.; Furman, T. Possibility of using biodiesel from sunflower oil as an additive for the improvement of lubrication properties of low-sulfur diesel fuel. Energy 2014, 65, 101–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labeckas, G.; Slavinskas, S. Comparative performance of direct injection diesel engine operating on ethanol, petrol and rapeseed oil blends. Energy Convers. Manag. 2009, 50, 792–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labeckas, G.; Slavinskas, S. Performance of direct-injection off-road diesel engine on rapeseed oil. Renew. Energy 2006, 31, 849–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bueno, A.V.; Velásquez, J.A.; Milanez, L.F. Heat release and engine performance effects of soybean oil ethyl ester blending into diesel fuel. Energy 2010, 36, 3907–3916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carraretto, C.; Macor, A.; Mirandola, A.; Stoppato, A.; Tonon, S. Biodiesel as alternative fuel: Experimental analysis and energetic evaluations. Energy 2004, 29, 2195–2211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silalertruksa, T.; Gheewala, S.H. Environmental sustainability assessment of palm biodiesel production in Thailand. Energy 2012, 43, 306–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.S.; Tedone, L.; Verdini, L.; Mastro, G. Implications of No-tillage system in faba bean production: energy analysis and potential agronomic benefits Open. Agric. Journal. 2018, 12, 270–285. [Google Scholar]

- Kazlauskas, M.; Bručienė, I.; Jasinskas, A.; Šarauskis, E. Comparative Analysis of Energy and GHG Emissions Using Fixed and Variable Fertilization Rates. Agronomy 2021, 11, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandal, K.; Saha, K.; Ghosh, P.; Hati, K.; Bandyopadhyay, K. Bioenergy and economic analysis of soybean-based crop production systems in central India. Biomass- Bioenergy 2002, 23, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torney, F.; Moeller, L.; Scarpa, A.; Wang, K. Genetic engineering approaches to improve bioethanol production from maize. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2007, 18, 193–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prade, T.; Svensson, S.-E.; Andersson, A.; Mattsson, J.E. Biomass and energy yield of industrial hemp grown for biogas and solid fuel. Biomass- Bioenergy 2011, 35, 3040–3049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prade, T.; Svensson, S.-E.; Mattsson, J.E. Energy balances for biogas and solid biofuel production from industrial hemp. Biomass- Bioenergy 2012, 40, 36–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinnifesi, F.K.; Makumba, W.; Kwesiga, F.R. Sustainable maize production using gliricidia/maize intercropping in Southern Malawi. Exp. Agric. 2006, 42, 441–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubo, M.; Walker, S.; Ogindo, H.O. A simulation model of cereal-legume intercropping system of semi-arid regions. Field Crops Res. 2005, 93, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ewansiha, S.U; Kamara, A.Y.; Chiezey, U.F.; Onyibe, J.E. Performance of cowpea grown as an intercrop with maize of different populations. Afr. Crop Sci. J. 2015, 23, 113–22. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change. Working Group III Contribution to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2014. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg3/ (accessed on 2 October 2020).

- Kizilaslan, H. Input–output energy analysis of cherries production in Tokat Province of Turkey. Appl. Energy 2009, 86, 1354–1358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiee, S.; Hashem, S.; Avval, M.; Mohammadi, A. Modeling and sensitivity analysis of energy inputs for apple production in Iran. Energy 2010, 35, 3301–3306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pishgar-Komleh, S.H.; Omid, M.; Heidari, M.D. On the study of energy use and GHG (greenhouse gas) emissions in greenhouse cucumber production in Yazd province. Energy 2013, 59, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glantz, M.H.; Gommes, R.; Ramasamy, S. Coping with a changing climate: considerations for adaptation and mitigation in agriculture. Environment and Natural Resources Management Series, Monitoring and Assessment-Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2009, 15, 33–57. [Google Scholar]

- arauskis, E.; Masilionytė, L.; Juknevičius, D.; Buragienė, S.; Kriaučiūnienė, Z. Energy use efficiency, GHG emissions, and cost-effectiveness of organic and sustainable fertilisation. Energy 2019, 172, 1151–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, E.; Cavigelli, M.A.; Camargo, G.; Ryan, M.; Ackroyd, V.J.; Richard, T.L.; Mirsky, S. Energy use and greenhouse gas emissions in organic and conventional grain crop production: Accounting for nutrient inflows. Agric. Syst. 2018, 162, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streimikiene, D.; Klevas, V.; Bubeliene, J. Use of EU structural funds for sustainable energy development in new EU member states. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2007, 11, 1167–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. Agriculture, Forestry and Other Land Use Emissions by Sources and Removals by Sinks. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/i3671e/i3671e.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2023).

- Lu, X.; Lu, X.; Cui, Y.; Liao, Y. Tillage and crop straw methods affect energy use efficiency, economics and greenhouse gas emissions in rainfed winter wheat field of Loess Plateau in China Acta Agric Scand Sect B Soil. Plant Sci. 2018, 68, 562–574. [Google Scholar]

- Alimagham, S.M.; Soltani, A.; Zeinali, E.; Kazemi, H. Energy flow analysis and estimation of greenhouse gases (GHG) emissions in different scenarios of soybean production (Case study: Gorgan region, Iran). J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 149, 621–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šarauskis, E.; Romaneckas, K.; Kumhála, F.; Kriaučiūnienė, Z. Energy use and carbon emission of conventional and organic sugar beet farming. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 201, 428–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diacono, M.; Rubino, P.; Montemurro, F. Precision nitrogen management of wheat. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 33, 219–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etemadi, F.; Hashemi, M.; Barker, A.V.; Zandvakili, O.R.; Liu, X. Agronomy, Nutritional Value, and Medicinal Application of Faba Bean (Vicia faba L.). Hortic. Plant J. 2019, 5, 170–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Months | Average Air Temperatures °C | Precipitation Rates mm | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Monthly | Long-Term | Monthly | Long-Term | |

| April | 6.9 | 6.9 | 4.0 | 41.3 |

| May | 10.5 | 13.2 | 94.4 | 61.7 |

| June | 19.0 | 16.1 | 99.3 | 76.9 |

| July | 17.4 | 18.7 | 60.4 | 96.6 |

| August | 18.7 | 17.3 | 92.8 | 88.9 |

| Treatments | Cultivation | Abbreviation |

|---|---|---|

| single crop | maize hemp faba bean |

MA HE FB |

| binary crop | maize + hemp maize + faba bean hemp + faba bean |

MA+HE MA+FB HE+FB |

| ternary crop | maize + hemp + faba bean | MA+HE+FB |

| Technological operation (machinery/depth/material rate)/Treatments | M | H | FB | M+H | M+FB | H+FB | M+H+FB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stubble cultivation (depth 12–15 cm) | o | o | o | o | o | o | o |

| Deep ploughing | o | o | o | o | o | o | o |

| Pre-seeding cultivation | o | o | o | o | o | o | o |

| Fertilization (N45 P45 K45 kg ha−1) | o | o | o | o | o | o | o |

| One-pass conventional seeding of single crops | o | o | o | - | - | - | - |

| One-pass double seeding for binary crops | - | - | - | o | o | o | - |

| Two-passes ternary seeding | - | - | - | - | - | - | o |

| Inter-row loosening (2–3 cm depth) | oo | oo | oo | oo | oo | oo | o |

| One-pass biomass harvesting (low harvester load) | o | - | o | - | o | - | - |

| One-pass biomass harvesting (high harvester load) | - | o | - | o | - | o | - |

| Two-passes biomass harvesting (high harvester load) | - | - | - | - | - | - | o |

| Crop/Treatments | M | H | FB | M+H | M+FB | H+FB | M+H+FB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maize yield | 63.5 | - | - | 68.8 | 90.7 | - | 36.2 |

| Hemp yield | - | 22.3 | - | 14.9 | - | 21.0 | 13.7 |

| Faba bean yield | - | - | 362.9 | - | 397.9 | 369.4 | 375.8 |

| Technological operation | Machinery power (kW) | Working width (m) | Field capacity (ha h−1) |

Working time (h ha−1) | Fuel consump-tion (L ha−1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stubble cultivation-discing | 102 | 4.00 | 2.21 | 0.45 | 8.2 |

| Deep ploughing | 102 | 1.75 | 0.80 | 1.25 | 24.1 |

| Pre-sowing cultivation | 102 | 7.00 | 4.56 | 0.22 | 6.4 |

| One-pass conventional seeding (single crop) | 45 | 3.00 | 1.41 | 0.71 | 4.0 |

| One-pass double seeding (binary crop) | 67 | 3.00 | 1.31 | 0.76 | 9.8 |

| Two-passes seeding (ternary crop) | 45 and 67 | 3.00 | 0.68 | 1.47 | 13.8 |

| Fertilization | 67 | 14.00 | 16.55 | 0.06 | 0.6 |

| Inter-row loosening | 54 | 3.00 | 1.56 | 0.64 | 4.10 |

| One-pass biomass harvesting (low harvester load) | 250 | 3.00 | 1.82 | 0.55 | 19.19 |

| One-pass biomass harvesting (high harvester load) | 250 | 3.00 | 1.37 | 0.73 | 27.55 |

| Two-passes biomass harvesting | 250 | 3.00 | 0.68 | 1.47 | 46.74 |

| Biomass chemical composition | M | H | FB | M+H | M+FB | H+FB | M+H+FB |

| pH | 6.51 | 7.07 | 6.63 | 6.66 | 6.43 | 7.09 | 6.87 |

| Total nitrogen % | 0.92 | 0.64 | 2.12 | 0.84 | 1.48 | 1.22 | 0.98 |

| Available phosphorus % | 0.20 | 0.16 | 0.38 | 0.20 | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.22 |

| Available potassium % | 1.20 | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.98 | 1.04 | 0.98 | 0.87 |

| Indices | Energy equivalent | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Inputs: | ||

| Human labour (MJ h−1) | 1.96 | [29] |

| Diesel fuel (MJ L−1) | 56.3 | [29] |

| Agricultural machinery (MJ h−1) | 357.2 | [30] |

| Seed of maize (MJ kg−1) | 16.6 | [29] |

| Seed of hemp (MJ kg−1) | 25.0 | Todde et al., 2022 [31] |

| Seed of faba bean (MJ kg−1) | 21.0 | Kazemi et al., 2015 [32] |

| N (MJ kg−1) | 60.6 | [29] |

| P2O5 (MJ kg−1) | 11.1 | [29] |

| K2O (MJ kg−1) | 6.7 | [29] |

| Outputs: | ||

| Maize biomass (MJ kg−1 dry matter) | 17.7 | [33] |

| Hemp biomass (MJ kg−1 dry matter) | 16.6 | [34] |

| Faba bean biomass (MJ kg−1 dry matter) | 17.0 | [35] |

| Inputs | CO2 equivalent | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Diesel fuel (kg CO2eq l−1) | 2.76 | [37] |

| Agricultural machinery (kg CO2eq MJ−1) | 0.071 | [38] |

| Seed of maize (kg CO2eq kg−1) | 15.3 | [39] |

| Seed of hemp (kg CO2eq kg−1) | 18.7 | [40] |

| Seed of faba bean (kg CO2eq kg−1) | 0.99 | [41] |

| N (kg CO2eq kg−1) | 1.30 | [20] |

| P2O5 (kg CO2eq kg−1) | 0.20 | [20] |

| K2O (kg CO2eq kg−1) | 0.15 | [20] |

| Inputs | M | H | FB | M+H | M+FB | H+FB | M+H+FB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human labour | 8.8 | 9.2 | 8.8 | 9.4 | 9.0 | 9.4 | 11.0 |

| Diesel fuel | 3980.4 | 4447.7 | 3980.4 | 4774.2 | 4307.0 | 4774.2 | 5815.8 |

| Agricultural machinery | 1607.4 | 1678.8 | 1607.4 | 1714.6 | 1643.1 | 1714.6 | 2000.3 |

| Seed of maize | 1054.1 | - | - | 1142.1 | 1505.6 | - | 600.9 |

| Seed of hemp | - | 512.9 | - | 342.7 | - | 483.0 | 315.1 |

| Seed of faba bean | - | - | 7620.9 | - | 8355.9 | 7757.4 | 7891.8 |

| N | 2727.0 | 2727.0 | 2727.0 | 2727.0 | 2727.0 | 2727.0 | 2727.0 |

| P2O5 | 499.5 | 499.5 | 499.5 | 499.5 | 499.5 | 499.5 | 499.5 |

| K2O | 301.5 | 301.5 | 301.5 | 301.5 | 301.5 | 301.5 | 301.5 |

| Total energy input | 10178.7 | 10176.6 | 16745.5 | 11511.0 | 19348.6 | 18266.6 | 20162.9 |

| Biomass yields and composition | M | H | FB | M+H | M+FB | H+FB | M+H+FB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total yield kg ha−1 | 4461c | 9038bc | 9811bc | 12197b | 7787bc | 10974b | 22928a |

| Proportion of biomass components | - | - | - | 1:4.1 | 1:1.2 | 1:0.2 | 1:5.3:10.6 |

| Yields of separate components kg ha−1: | |||||||

| Maize yield | - | - | - | 2373 | 3519 | - | 1358 |

| Hemp yield | - | - | - | 9824 | - | 8710 | 7239 |

| Faba bean yield | - | - | - | - | 4268 | 2264 | 14331 |

| Treatments | Diesel fuel consumption L ha−1 |

Energy input MJ ha−1 |

Energy output MJ ha−1 |

Energy efficiency ratio | Energy productivity MJ ha−1 | Net energy MJ ha−1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | 70.7 | 10178.7 | 78959.7 | 7.76 | 0.44 | 68781.0 |

| H | 79.0 | 10176.6 | 150030.8 | 14.74 | 0.89 | 139854.2 |

| FB | 70.7 | 16745.5 | 166787.0 | 9.96 | 0.59 | 150041.5 |

| M+H | 84.8 | 11511.0 | 205080.5 | 17.82 | 1.06 | 193569.5 |

| M+FB | 76.5 | 19348.6 | 134842.3 | 6.97 | 0.40 | 115493.7 |

| H+FB | 84.8 | 18266.6 | 183074.0 | 10.02 | 0.60 | 164807.4 |

| M+H+FB | 103.3 | 20162.9 | 387831.0 | 19.23 | 1.14 | 367668.1 |

| Indices/Treatments | M | H | FB | M+H | M+FB | H+FB | M+H+FB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diesel fuel (kg CO2eq ha−1) | 195.1 | 218.0 | 195.1 | 234.0 | 211.1 | 234.0 | 285.1 |

| Agricultural machinery (kg CO2eq ha−1) | 0.32 | 0.33 | 0.32 | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.34 | 0.40 |

| Seed of maize (kg CO2eq ha−1) | 971.6 | - | - | 1052.6 | 1387.7 | - | 553.9 |

| Seed of hemp (kg CO2eq ha−1) | - | 417.0 | - | 278.6 | - | 392.7 | 256.2 |

| Seed of faba bean (kg CO2eq ha−1) | - | - | 359.3 | - | 393.9 | 365.7 | 372.0 |

| N (kg CO2eq ha−1) | 58.5 | 58.5 | 58.5 | 58.5 | 58.5 | 58.5 | 58.5 |

| P2O5 (kg CO2eq ha−1) | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 9.0 |

| K2O (kg CO2eq ha−1) | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.8 | 6.8 |

| Total GHG emission (kg CO2eq ha−1) | 1241.32 | 709.63 | 629.02 | 1729.84 | 2067.33 | 1067.04 | 1541.90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).