Submitted:

22 August 2023

Posted:

22 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

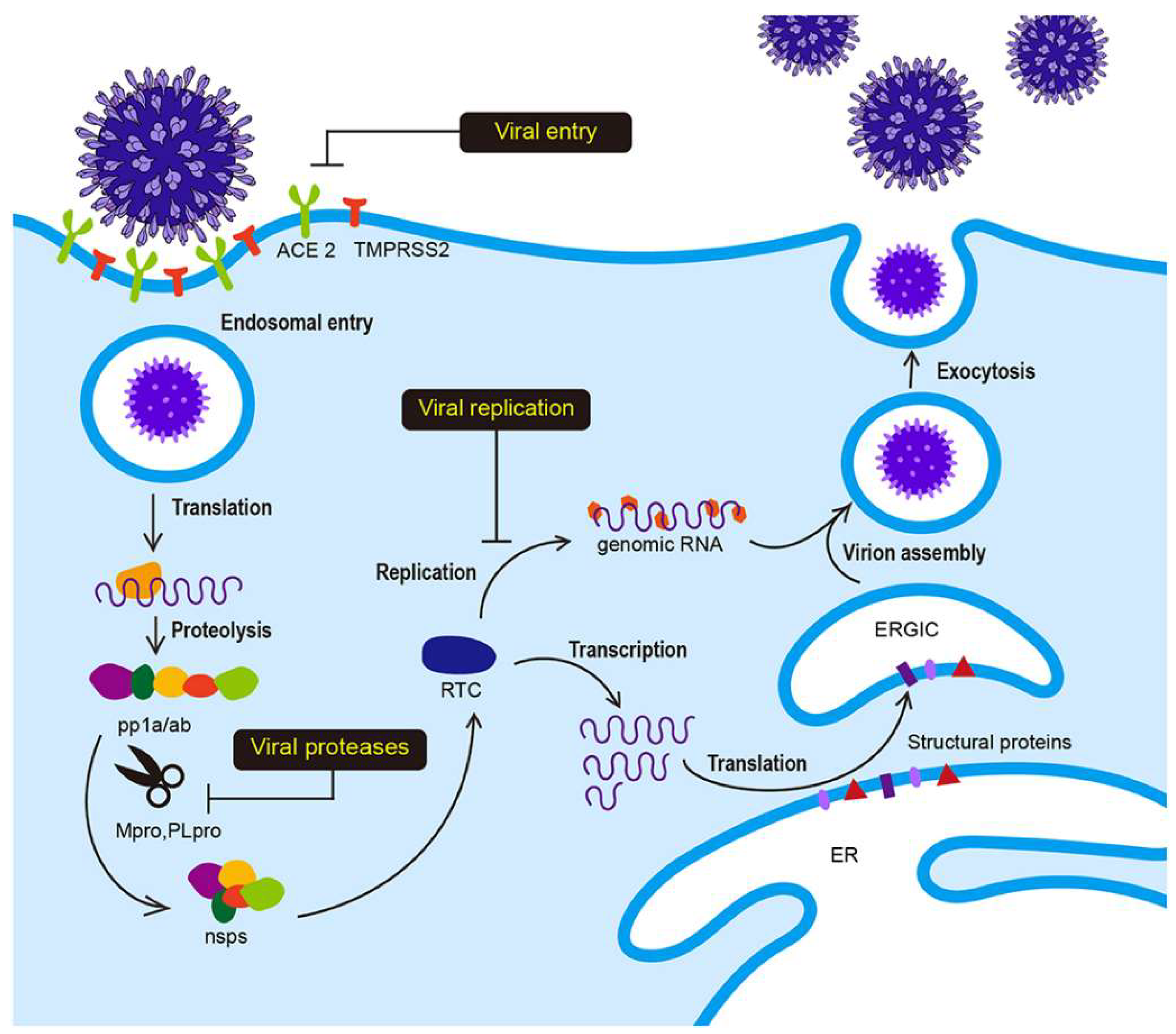

Introduction

- I.

- Clinical description of SARS-CoV-2

- II.

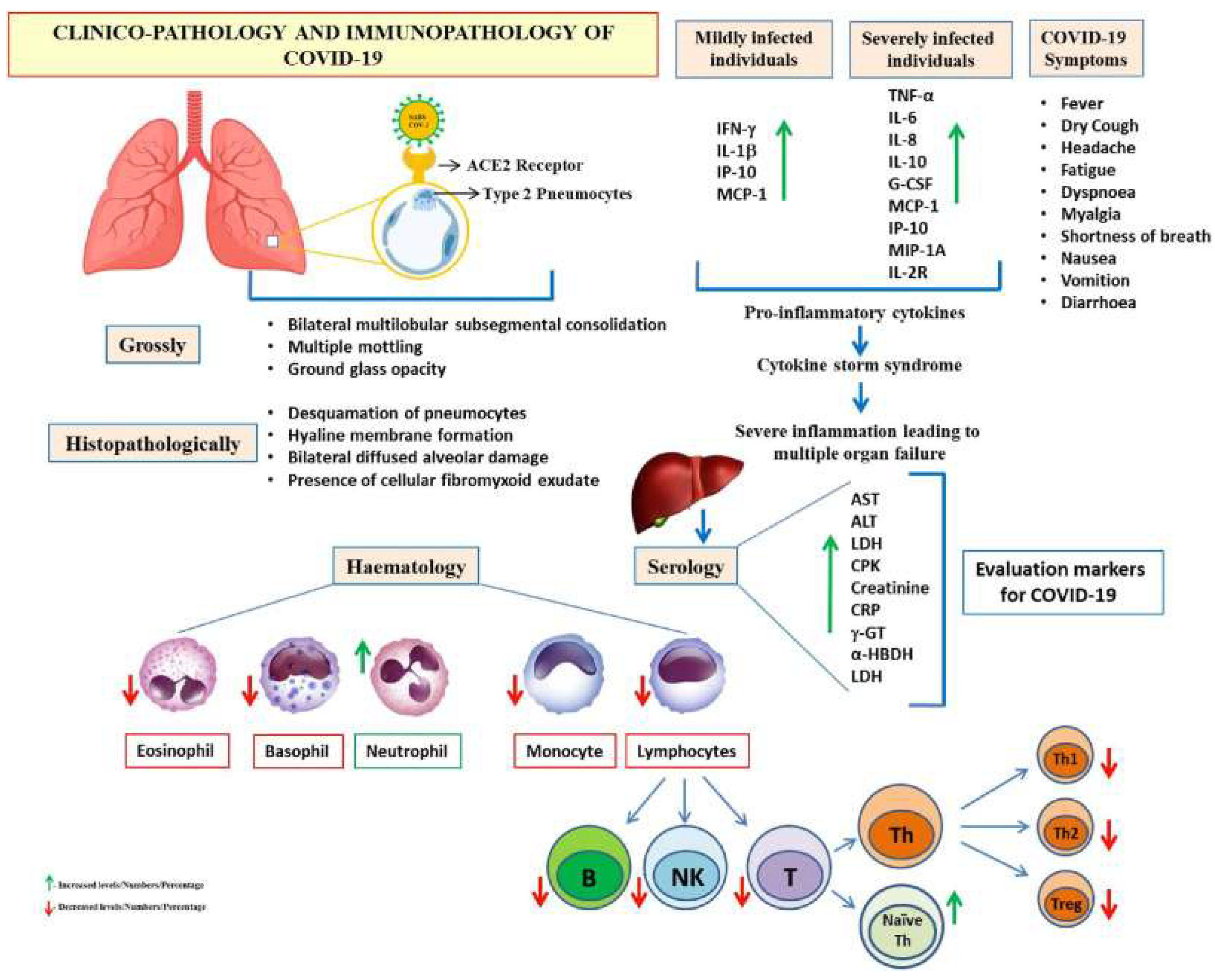

- SARS-CoV-2 prevalence and pathology

- II.1.

- SARS-CoV-2 transmission, clinical presentation, and risk factors for severe disease and fatality

- II.2.

- Profile Characteristics and Prognostic Markers in COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2

- III.

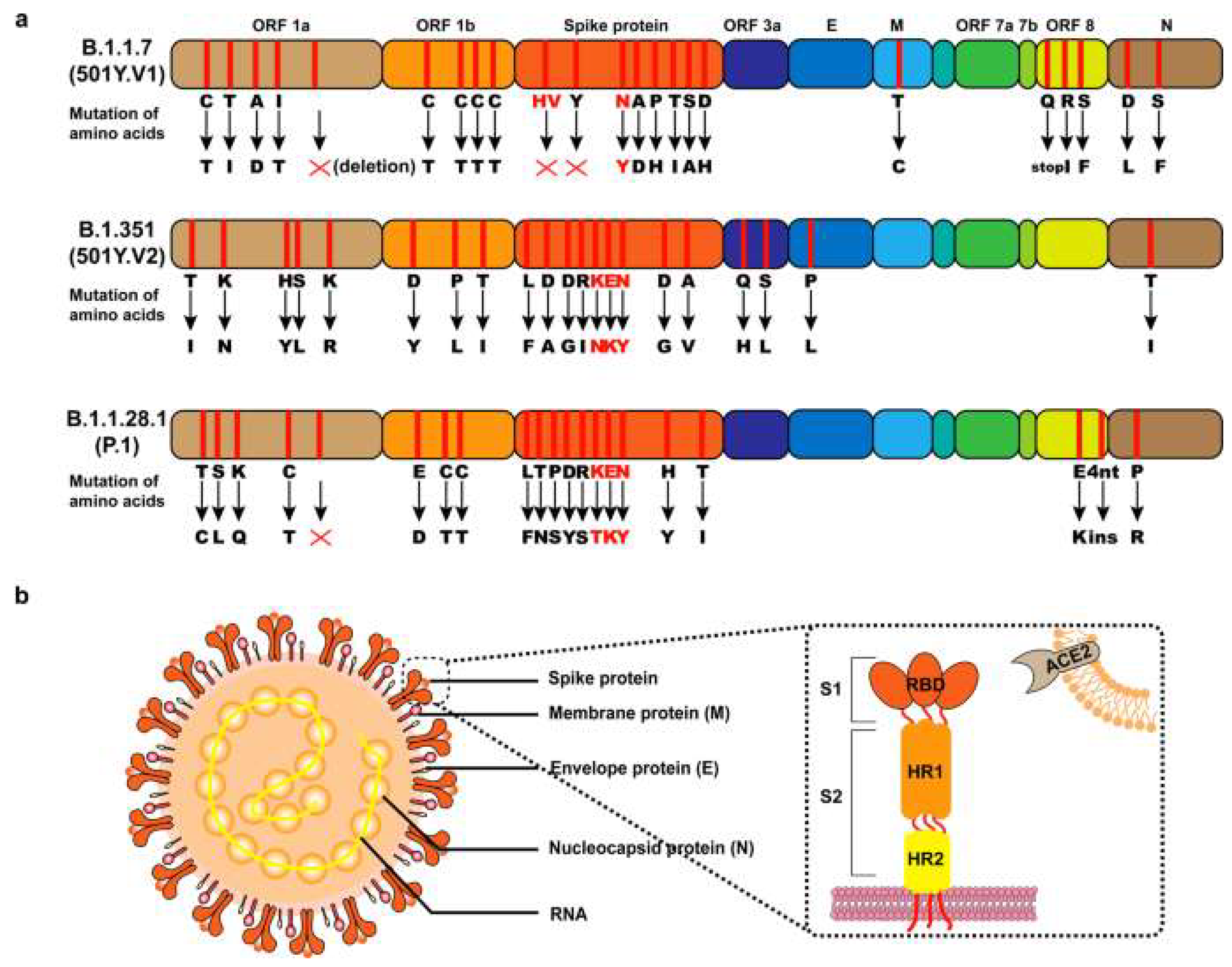

- Discussion on postulated hypothesis on Covid-19 mutations

- IV.

- Covid-19 therapies, vaccines, and other ongoing clinical trials therapies

| Approved SARS-CoV-2 Vaccines | |||||||

| Vaccine Name | Manufacturer | Type | Dosage | Efficacy | Target | Reference | |

| Pfizer-BioNTech | Pfizer, BioNTech | mRNA | 2 doses, 21 days apart | 95% | Spike protein | Haas, Eric J., Frederick J. Angulo, John M. McLaughlin, Emilia Anis, Shepherd R. Singer, Farid Khan, Nati Brooks et al., 2021 | |

| Moderna | Moderna | mRNA | 2 doses, 28 days apart | 94.1% | Spike protein | Baden, L.R., El Sahly, H.M., Essink, B., et al., 2021. | |

| Johnson & Johnson | Johnson & Johnson | Viral vector | 1 dose | 72% (in the U.S.) | Spike protein | Creech, C.B., Walker, S.C. and Samuels, R.J., 2021. | |

|

AstraZeneca |

AstraZeneca, University of Oxford | Viral vector | 2 doses, 4-12 weeks apart |

70.4% (average) |

Spike protein | Keeling, M.J., Moore, S., Penman, B.S. and Hill, E.M., 2023. | |

| SARS-CoV-2 therapeutics | |||||||

| Drug name | Manufacturer | Type | Target | Antiviral Agent | Status | References | |

| Remdesivir | Gilead Sciences | Antiviral | RNA polymerase | Nucleotide analogue | FDA-approved for emergency use in hospitalized patients | Pruijssers, A.J., George, A.S., Schäfer, A., et al., 2020. | |

| Baricitinib | Eli Lilly and Company | Anti-inflammatory | AP-1 | Janus kinase inhibitor | FDA-approved for emergency use in combination with remdesivir | Poduri, R., Joshi, G. and Jagadeesh, G., 2020. | |

| Tocilizumab | Roche | Anti-inflammatory | IL-6 | Monoclonal antibody | FDA-approved for emergency use in hospitalized patients | Fu, B., Xu, X. and Wei, H., 2020. | |

| Sotrovimab | GlaxoSmithKline, Vir Biotechnology | Monoclonal antibody | Spike protein | Monoclonal antibody | FDA-approved for emergency use in high-risk individuals | Gupta, A., Gonzalez-Rojas, Y., Juarez, E., et al., 2021. | |

| Molnupiravir | Merck & Co. | Antiviral | RNA polymerase | Nucleotide analogue | Currently under review for emergency use authorization | Ashour, N.A., Abo Elmaaty, A., Sarhan, A.A., et al. 2022. | |

| Ongoing clinical trials for SARS-CoV-2 | |||||||

| Study name | Sponsor | Type | Phase | Target | Antiviral Agent | Status | |

| ACTIV-6 | NIH | Therapeutic | 3 | Various | Various | Ongoing Naggie, S., Boulware, D.R., Lindsell, C.J., et al., 2023. |

|

| COMET-ICE | NIAID, Lilly | Therapeutic | 3 | Various | Various | Ongoing Gupta, A., Gonzalez-Rojas, Y., et al,2021. |

|

| REGN-COV2 | Regeneron | Therapeutic | 3 | Spike protein | Monoclonal antibody | Ongoing Baum, A., Ajithdoss, D., Copin, R., et al., 2020. |

|

| COV-BOOST | University of Oxford | Vaccine | 2/3 | Spike protein | N/A | Ongoing Chavda, V.P. and Apostolopoulos, V., 2022. |

|

| COV-FLU | Novavax | Vaccine | 2/3 | Influenza virus | N/A | Ongoing Cao, K., Wang, X., Peng, H., Ding, et al., 2022. |

|

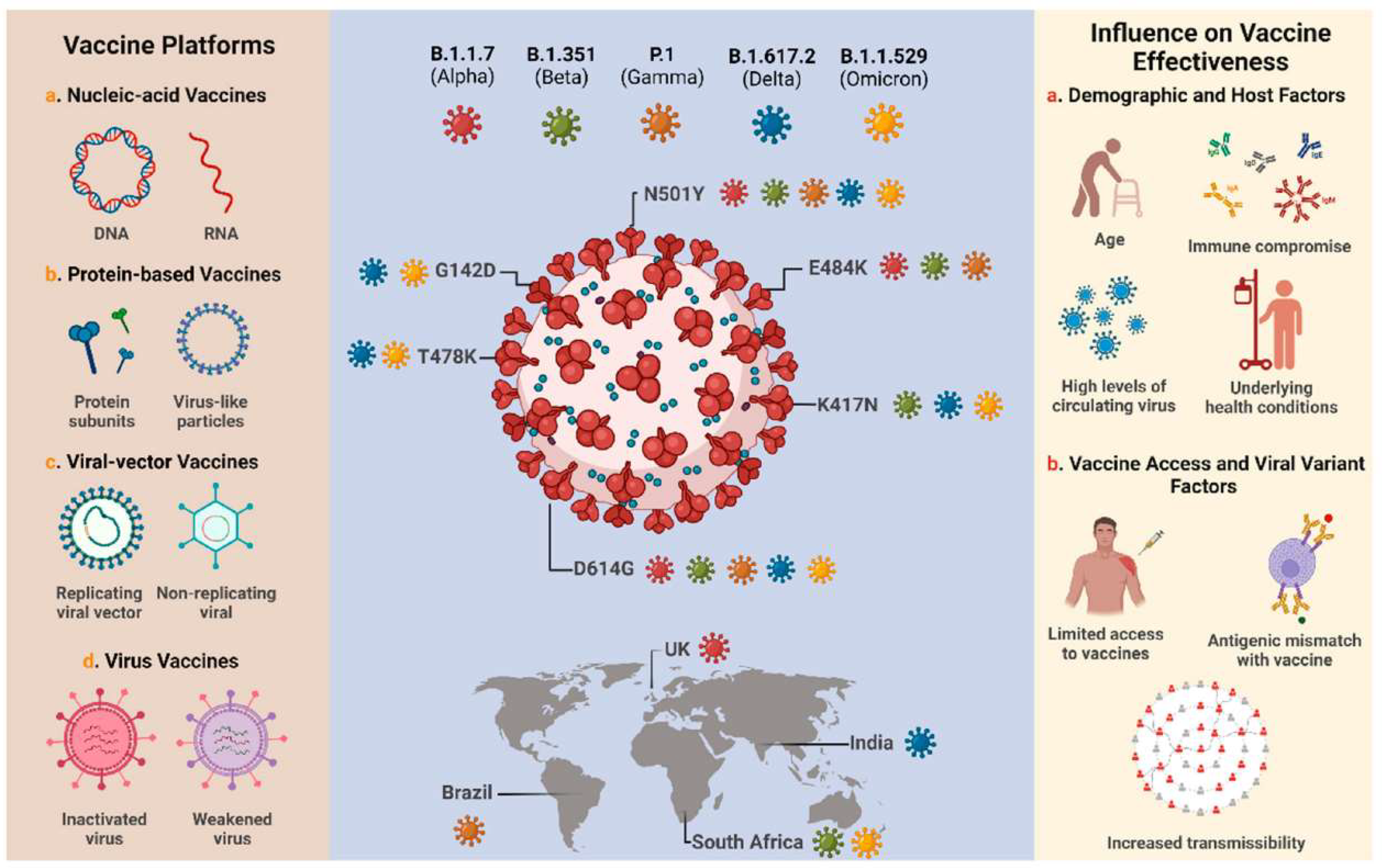

- V.

- Drug Repurposing for COVID-19

- V.1.

- Vaccine Development

- V.2.

- Experimental Therapeutic Interventions

- V.2.1.

- Convalescent Plasma (CP) Therapy

- V.2.2.

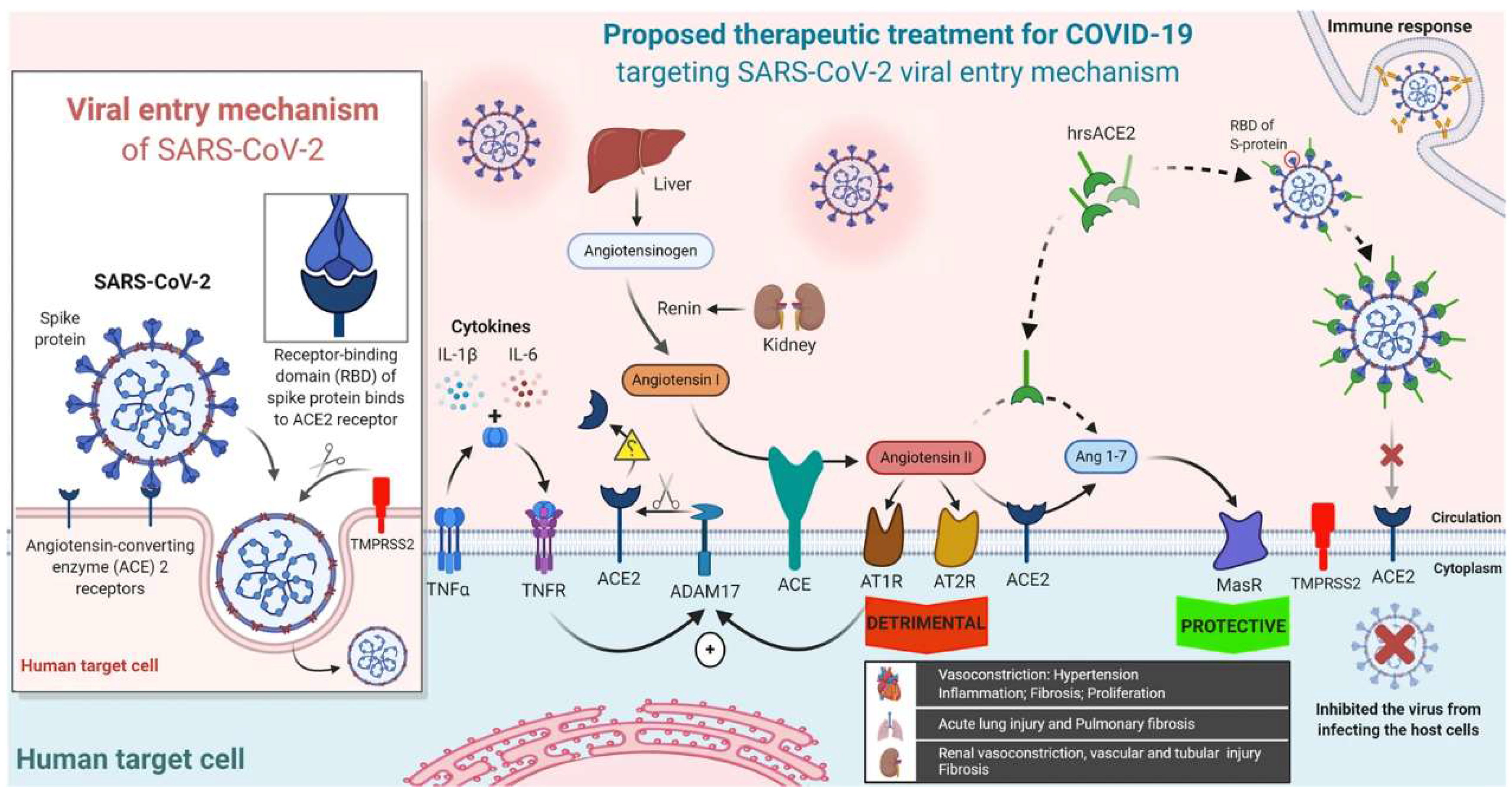

- Soluble Human Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2)

- VI.

- Non-Pharmacological Interventions

- VII.

- Future Directions for COVID-19 Research

References

- Acter, T.; Uddin, N.; Das, J.; Akhter, A.; Choudhury, T.R.; Kim, S. Evolution of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) as coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic: A global health emergency. Science of the Total Environment 2020, 730, 138996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamel Boulos, M.N.; Geraghty, E.M. Geographical tracking and mapping of coronavirus disease COVID-19/severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) epidemic and associated events around the world: How 21st century GIS technologies are supporting the global fight against outbreaks and epidemics. International journal of health geographics 2020, 19, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jacob Machado, D.; Scott, R.; Guirales, S.; Janies, D.A. Fundamental evolution of all Orthocoronavirinae including three deadly lineages descendent from Chiroptera-hosted coronaviruses: SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. Cladistics 2021, 37, 461–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhama, K.; Patel, S.K.; Pathak, M.; Yatoo, M.I.; Tiwari, R.; Malik, Y.S.; Singh, R.; Sah, R.; Rabaan, A.A.; Bonilla-Aldana, D.K.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J. An update on SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 with particular reference to its clinical pathology, pathogenesis, immunopathology and mitigation strategies. Travel medicine and infectious disease 2020, 37, 101755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seitz, B.M.; Aktipis, A.; Buss, D.M.; Alcock, J.; Bloom, P.; Gelfand, M.; Harris, S.; Lieberman, D.; Horowitz, B.N.; Pinker, S.; Wilson, D.S. The pandemic exposes human nature: 10 evolutionary insights. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2020, 117, 27767–27776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, A.; Brunialti, E.; Dellavedova, J.; Meda, C.; Rebecchi, M.; Conti, M.; Donnici, L.; De Francesco, R.; Reggiani, A.; Lionetti, V.; Ciana, P. DNA aptamers masking angiotensin converting enzyme 2 as an innovative way to treat SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Pharmacological research 2022, 175, 105982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, Q.; Guo, D. Emerging coronaviruses: Genome structure, replication, and pathogenesis. Journal of medical virology 2020, 92, 418–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awadasseid, A.; Wu, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Zhang, W. Effective drugs used to combat SARS-CoV-2 infection and the current status of vaccines. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2021, 137, 111330. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgson, S.H.; Mansatta, K.; Mallett, G.; Harris, V.; Emary, K.R.; Pollard, A.J. What defines an efficacious COVID-19 vaccine? A review of the challenges assessing the clinical efficacy of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2. The lancet infectious diseases 2021, 21, e26–e35. [Google Scholar]

- Sanyaolu, A.; Okorie, C.; Marinkovic, A.; Patidar, R.; Younis, K.; Desai, P.; Hosein, Z.; Padda, I.; Mangat, J.; Altaf, M. Comorbidity and its impact on patients with COVID-19. SN comprehensive clinical medicine 2020, 2, 1069–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singhal, T. A review of coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19). The indian journal of pediatrics 2020, 87, 281–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Haleeqa, M.; Alshamsi, I.; Al Habib, A.; Noshi, M.; Abdullah, S.; Kamour, A.; Ibrahim, H. Optimizing supportive care in COVID-19 patients: A multidisciplinary approach. Journal of multidisciplinary healthcare 2020, 877–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abu Haleeqa, M.; Alshamsi, I.; Al Habib, A.; Noshi, M.; Abdullah, S.; Kamour, A.; Ibrahim, H. ; 2020. Optimizing supportive care in COVID-19 patients: A multidisciplinary approach. Jo.

- Haldane, V.; De Foo, C.; Abdalla, S.M.; Jung, A.S.; Tan, M.; Wu, S.; Chua, A.; Verma, M.; Shrestha, P.; Singh, S.; Perez, T. Health systems resilience in managing the COVID-19 pandemic: Lessons from 28 countries. Nature Medicine 2021, 27, 964–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, N.N.; Tan, J.C.; Li, J.; Li, S.; Cai, Y.; Wang, H. COVID-19 pandemic: Experiences in China and implications for its prevention and treatment worldwide. Current cancer drug targets 2020, 20, 410–416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chauhan, S. Comprehensive review of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Biomedical journal 2020, 43, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascarella, G.; Strumia, A.; Piliego, C.; Bruno, F.; Del Buono, R.; Costa, F.; Scarlata, S.; Agrò, F.E. COVID-19 diagnosis and management: A comprehensive review. Journal of internal medicine 2020, 288, 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pal, M.; Berhanu, G.; Desalegn, C.; Kandi, V. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2): An update. Cureus 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loeffler-Wirth, H.; Schmidt, M.; Binder, H. Covid-19 transmission trajectories–monitoring the pandemic in the worldwide context. Viruses 2020, 12, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, M.; Zhang, Z.; Kuwahara, K. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on children and adolescents' lifestyle behavior larger than expected. Progress in cardiovascular diseases 2020, 63, 531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrosillo, N.; Viceconte, G.; Ergonul, O.; Ippolito, G.; Petersen, E. COVID-19, SARS and MERS: Are they closely related? . Clinical microbiology and infection 2020, 26, 729–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, M.; Berhanu, G.; Desalegn, C.; Kandi, V. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2): An update. Cureus 2020, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shang, Y.; Pan, C.; Yang, X.; Zhong, M.; Shang, X.; Wu, Z.; Yu, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhong, Q.; Zheng, X.; Sang, L. Management of critically ill patients with COVID-19 in ICU: Statement from front-line intensive care experts in Wuhan, China. Annals of intensive care 2020, 10, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh, S.; Bornman, C.; Zafer, M.M. Antimicrobial Resistance Threats in the emerging COVID-19 pandemic: Where do we stand? . Journal of infection and public health 2021, 14, 555–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rabi, F.A.; Al Zoubi, M.S.; Kasasbeh, G.A.; Salameh, D.M.; Al-Nasser, A.D. SARS-CoV-2 and coronavirus disease 2019: What we know so far. Pathogens 2020, 9, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meekins, D.A.; Gaudreault, N.N.; Richt, J.A. Natural and experimental SARS-CoV-2 infection in domestic and wild animals. Viruses 2021, 13, 1993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damialis, A.; Gilles, S.; Sofiev, M.; Sofieva, V.; Kolek, F.; Bayr, D.; Plaza, M.P.; Leier-Wirtz, V.; Kaschuba, S.; Ziska, L.H.; Bielory, L. Higher airborne pollen concentrations correlated with increased SARS-CoV-2 infection rates, as evidenced from 31 countries across the globe. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2021, 118, e2019034118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.; Mustafa, F.; Rizvi, T.A.; Loney, T.; Al Suwaidi, H.; Al-Marzouqi, A.H.H.; Kamal Eldin, A.; Alsabeeha, N.; Adrian, T.E.; Stefanini, C.; Nowotny, N. SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19: Viral genomics, epidemiology, vaccines, and therapeutic interventions. Viruses 2020, 12, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.; Mustafa, F.; Rizvi, T.A.; Loney, T.; Al Suwaidi, H.; Al-Marzouqi, A.H.H.; Kamal Eldin, A.; Alsabeeha, N.; Adrian, T.E.; Stefanini, C.; Nowotny, N. SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19: Viral genomics, epidemiology, vaccines, and therapeutic interventions. Viruses 2020, 12, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatraju, P.K.; Ghassemieh, B.J.; Nichols, M.; Kim, R.; Jerome, K.R.; Nalla, A.K.; Greninger, A.L.; Pipavath, S.; Wurfel, M.M.; Evans, L.; Kritek, P.A. Covid-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle region—Case series. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 382, 2012–2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callow, M.A.; Callow, D.D.; Smith, C. Older adults’ intention to socially isolate once COVID-19 stay-at-home orders are replaced with “safer-at-home” public health advisories: A survey of respondents in Maryland. Journal of Applied Gerontology 2020, 39, 1175–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azuma, K.; Yanagi, U.; Kagi, N.; Kim, H.; Ogata, M.; Hayashi, M. Environmental factors involved in SARS-CoV-2 transmission: Effect and role of indoor environmental quality in the strategy for COVID-19 infection control. Environmental health and preventive medicine 2020, 25, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liu, L.; Zhang, D.; Xu, J.; Dai, H.; Tang, N.; Su, X.; Cao, B. SARS-CoV-2 and viral sepsis: Observations and hypotheses. The Lancet 2020, 395, 1517–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Liu, L.; Zhang, D.; Xu, J.; Dai, H.; Tang, N.; Su, X.; Cao, B. SARS-CoV-2 and viral sepsis: Observations and hypotheses. The Lancet 2020, 395, 1517–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Killingley, B.; Mann, A.J.; Kalinova, M.; Boyers, A.; Goonawardane, N.; Zhou, J.; Lindsell, K.; Hare, S.S.; Brown, J.; Frise, R.; Smith, E. Safety, tolerability and viral kinetics during SARS-CoV-2 human challenge in young adults. Nature Medicine 2022, 28, 1031–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, K.A.; Spillane, S.; Comber, L.; Cardwell, K.; Harrington, P.; Connell, J.; Teljeur, C.; Broderick, N.; De Gascun, C.F.; Smith, S.M.; Ryan, M. The duration of infectiousness of individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2. Journal of Infection 2020, 81, 847–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Cao, Q.; Qin, L.E.; Wang, X.; Cheng, Z.; Pan, A.; Dai, J.; Sun, Q.; Zhao, F.; Qu, J.; Yan, F. Clinical characteristics and imaging manifestations of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19): A multi-center study in Wenzhou city, Zhejiang, China. Journal of Infection 2020, 80, 388–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, D. The impact of Covid-19 pandemic on elderly mental health. International journal of geriatric psychiatry 2020, 35, 1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baj, J.; Karakuła-Juchnowicz, H.; Teresiński, G.; Buszewicz, G.; Ciesielka, M.; Sitarz, R.; Forma, A.; Karakuła, K.; Flieger, W.; Portincasa, P.; Maciejewski, R. COVID-19: Specific and non-specific clinical manifestations and symptoms: The current state of knowledge. Journal of clinical medicine 2020, 9, 1753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuen, K.S.; Ye, Z.W.; Fung, S.Y.; Chan, C.P.; Jin, D.Y. SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: The most important research questions. Cell & bioscience 2020, 10, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, S.J. Long COVID or post-COVID-19 syndrome: Putative pathophysiology, risk factors, and treatments. Infectious diseases 2021, 53, 737–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Geng, X.; Tan, Y.; Li, Q.; Xu, C.; Xu, J.; Hao, L.; Zeng, Z.; Luo, X.; Liu, F.; Wang, H. New understanding of the damage of SARS-CoV-2 infection outside the respiratory system. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy 2020, 127, 110195. [Google Scholar]

- Dhama, K.; Patel, S.K.; Pathak, M.; Yatoo, M.I.; Tiwari, R.; Malik, Y.S.; Singh, R.; Sah, R.; Rabaan, A.A.; Bonilla-Aldana, D.K.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J. An update on SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 with particular reference to its clinical pathology, pathogenesis, immunopathology and mitigation strategies. Travel medicine and infectious disease 2020, 37, 101755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tjendra, Y.; Al Mana, A.F.; Espejo, A.P.; Akgun, Y.; Millan, N.C.; Gomez-Fernandez, C.; Cray, C. Predicting disease severity and outcome in COVID-19 patients: A review of multiple biomarkers. Archives of pathology & laboratory medicine 2020, 144, 1465–1474. [Google Scholar]

- Hachim, M.Y.; Hachim, I.Y.; Naeem, K.B.; Hannawi, H.; Salmi, I.A.; Hannawi, S. D-dimer, troponin, and urea level at presentation with COVID-19 can predict ICU admission: A single centered study. Frontiers in medicine 2020, 7, 585003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingo, E.; García-Crespo, C.; Lobo-Vega, R.; Perales, C. Mutation rates, mutation frequencies, and proofreading-repair activities in RNA virus genetics. Viruses 2021, 13, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhama, K.; Patel, S.K.; Pathak, M.; Yatoo, M.I.; Tiwari, R.; Malik, Y.S.; Singh, R.; Sah, R.; Rabaan, A.A.; Bonilla-Aldana, D.K.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J. An update on SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 with particular reference to its clinical pathology, pathogenesis, immunopathology and mitigation strategies. Travel medicine and infectious disease 2020, 37, 101755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassanpour, M.; Rezaie, J.; Nouri, M.; Panahi, Y. The role of extracellular vesicles in COVID-19 virus infection. Infection, Genetics and Evolution 2020, 85, 104422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamwal, S.; Gautam, A.; Elsworth, J.; Kumar, M.; Chawla, R.; Kumar, P. An updated insight into the molecular pathogenesis, secondary complications and potential therapeutics of COVID-19 pandemic. Life sciences 2020, 257, 118105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volz, E.; Hill, V.; McCrone, J.T.; Price, A.; Jorgensen, D.; O’Toole, Á.; Southgate, J.; Johnson, R.; Jackson, B.; Nascimento, F.F.; Rey, S.M. Evaluating the effects of SARS-CoV-2 spike mutation D614G on transmissibility and pathogenicity. Cell 2021, 184, 64–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korber, B.; Fischer, W.M.; Gnanakaran, S.; Yoon, H.; Theiler, J.; Abfalterer, W.; Foley, B.; Giorgi, E.E.; Bhattacharya, T.; Parker, M.D.; Partridge, D.G. Spike mutation pipeline reveals the emergence of a more transmissible form of SARS-CoV-2. BioRxiv. 2020.

- Mengist, H.M.; Kombe, A.J.K.; Mekonnen, D.; Abebaw, A.; Getachew, M.; Jin, T. Mutations of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: Implications on immune evasion and vaccine-induced immunity. In Seminars in immunology; Academic Press, 2021; Volume 55, p. 101533. [Google Scholar]

- De Maio, N.; Walker, C.R.; Turakhia, Y.; Lanfear, R.; Corbett-Detig, R.; Goldman, N. Mutation rates and selection on synonymous mutations in SARS-CoV-2. Genome Biology and Evolution 2021, 13, evab087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karakose, T.; Polat, H.; Papadakis, S. Examining teachers’ perspectives on school principals’ digital leadership roles and technology capabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.A. SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19): A short update on molecular biochemistry, pathology, diagnosis and therapeutic strategies. Annals of Clinical Biochemistry 2022, 59, 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jolliffe, D.A.; Camargo, C.A.; Sluyter, J.D.; Aglipay, M.; Aloia, J.F.; Ganmaa, D.; Bergman, P.; Bischoff-Ferrari, H.A.; Borzutzky, A.; Damsgaard, C.T.; Dubnov-Raz, G. Vitamin D supplementation to prevent acute respiratory infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis of aggregate data from randomised controlled trials. The lancet Diabetes & endocrinology 2021, 9, 276–292. [Google Scholar]

- Te Velthuis, A.J.; van den Worm, S.H.; Sims, A.C.; Baric, R.S.; Snijder, E.J.; van Hemert, M.J. Zn2+ inhibits coronavirus and arterivirus RNA polymerase activity in vitro and zinc ionophores block the replication of these viruses in cell culture. PLoS pathogens 2010, 6, e1001176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaque, M.S. COVID-19 pandemic: Can zinc supplementation provide an additional shield against the infection? . Computational and structural biotechnology journal 2021, 19, 1371–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.K.; Satapathy, A.; Naidu, M.M.; Mukhopadhyay, S.; Sharma, S.; Barton, L.M.; Stroberg, E.; Duval, E.J.; Pradhan, D.; Tzankov, A.; Parwani, A.V. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease 19 (COVID-19)–anatomic pathology perspective on current knowledge. Diagnostic pathology 2020, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berekaa, M.M. Insights into the COVID-19 pandemic: Origin, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapeutic interventions. Frontiers in Bioscience-Elite 2020, 13, 117–139. [Google Scholar]

- Shapovalova, V. An Innovative multidisciplinary study of the availability of coronavirus vaccines in the world. SSP Modern Pharmacy and Medicine 2022, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitulescu, G.M.; Paunescu, H.; Moschos, S.A.; Petrakis, D.; Nitulescu, G.; Ion, G.N.D.; Spandidos, D.A.; Nikolouzakis, T.K.; Drakoulis, N.; Tsatsakis, A. Comprehensive analysis of drugs to treat SARS CoV 2 infection: Mechanistic insights into current COVID 19 therapies. International journal of molecular medicine 2020, 46, 467–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.; Mustafa, F.; Rizvi, T.A.; Loney, T.; Al Suwaidi, H.; Al-Marzouqi, A.H.H.; Kamal Eldin, A.; Alsabeeha, N.; Adrian, T.E.; Stefanini, C.; Nowotny, N. SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19: Viral genomics, epidemiology, vaccines, and therapeutic interventions. Viruses 2020, 12, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinez, M.A. ; 2022. Efficacy of repurposed antiviral drugs: Lessons from COVID-19. Drug Discovery Today.

- WHO Solidarity Trial Consortium. Repurposed antiviral drugs for Covid-19—Interim WHO solidarity trial results. New England journal of medicine 2021, 384, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costanzo, M.; De Giglio, M.A.; Roviello, G.N. SARS-CoV-2: Recent reports on antiviral therapies based on lopinavir/ritonavir, darunavir/umifenovir, hydroxychloroquine, remdesivir, favipiravir and other drugs for the treatment of the new coronavirus. Current medicinal chemistry 2020, 27, 4536–4541. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zeldin, R.K.; Petruschke, R.A. Pharmacological and therapeutic properties of ritonavir-boosted protease inhibitor therapy in HIV-infected patients. Journal of antimicrobial chemotherapy 2004, 53, 4–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.T.; Idid, S.Z. Can Zn be a critical element in COVID-19 treatment? . Biological trace element research 2021, 199, 550–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, M.S.; Barhate, S.D. Favipiravir has been investigated for the treatment of life-threatening pathogens such as Ebola virus, Lassa virus, and now COVID-19: A review. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical Research 2021, 11, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Huang, S.; Yin, L. The cytokine storm and COVID-19. Journal of medical virology 2021, 93, 250–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiraki, K.; Daikoku, T. Favipiravir, an anti-influenza drug against life-threatening RNA virus infections. Pharmacology & therapeutics 2020, 209, 107512. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, A.K.; Singh, A.; Shaikh, A.; Singh, R.; Misra, A. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19 with or without diabetes: A systematic search and a narrative review with a special reference to India and other developing countries. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 2020, 14, 241–246. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Liu, Z.; Ge, J. Scientific research progress of COVID-19/SARS-CoV-2 in the first five months. Journal of cellular and molecular medicine 2020, 24, 6558–6570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastick, K.A.; Okafor, E.C.; Wang, F.; Lofgren, S.M.; Skipper, C.P.; Nicol, M.R.; Pullen, M.F.; Rajasingham, R.; McDonald, E.G.; Lee, T.C.; Schwartz, I.S. Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine for treatment of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19). In Open forum infectious diseases; Oxford University Press: USA, 2020; Volume 7, p. ofaa130. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, C.J.; Lee, H.W.; Tchesnokov, E.P.; Perry, J.K.; Feng, J.Y.; Bilello, J.P.; Porter, D.P.; Götte, M. Efficient incorporation and template-dependent polymerase inhibition are major determinants for the broad-spectrum antiviral activity of remdesivir. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2022, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, L.J.; Pruijssers, A.J.; Lee, H.W.; Gordon, C.J.; Tchesnokov, E.P.; Gribble, J.; George, A.S.; Hughes, T.M.; Lu, X.; Li, J.; Perry, J.K. Mutations in the SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase confer resistance to remdesivir by distinct mechanisms. Science translational medicine 2022, 14, eabo0718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weston, S.; Coleman, C.M.; Haupt, R.; Logue, J.; Matthews, K.; Li, Y.; Reyes, H.M.; Weiss, S.R.; Frieman, M.B. Broad anti-coronavirus activity of food and drug administration-approved drugs against SARS-CoV-2 in vitro and SARS-CoV in vivo. Journal of virology 2020, 94, e01218–e01220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grein, J.; Ohmagari, N.; Shin, D.; Diaz, G.; Asperges, E.; Castagna, A.; Feldt, T.; Green, G.; Green, M.L.; Lescure, F.X.; Nicastri, E. Compassionate use of remdesivir for patients with severe Covid-19. New England Journal of Medicine 2020, 382, 2327–2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mechineni, A.; Kassab, H.; Manickam, R. Remdesivir for the treatment of COVID 19: Review of the pharmacological properties, safety and clinical effectiveness. Expert Opinion on Drug Safety 2021, 20, 1299–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohag, A.A.M.; Hannan, M.A.; Rahman, S.; Hossain, M.; Hasan, M.; Khan, M.K.; Khatun, A.; Dash, R.; Uddin, M.J. Revisiting potential druggable targets against SARS-CoV-2 and repurposing therapeutics under preclinical study and clinical trials: A comprehensive review. Drug development research 2020, 81, 919–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velikova, T.; Georgiev, T. SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and autoimmune diseases amidst the COVID-19 crisis. Rheumatology international 2021, 41, 509–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydillo, T.; Rombauts, A.; Stadlbauer, D.; Aslam, S.; Abelenda-Alonso, G.; Escalera, A.; Amanat, F.; Jiang, K.; Krammer, F.; Carratala, J.; García-Sastre, A. Antibody immunological imprinting on COVID-19 patients. MedRxiv 2020, 2020-10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, J.A.; Mulla, A.H.; Farooqi, T.; Pottoo, F.H.; Anwar, S.; Rengasamy, K.R. Targets and strategies for vaccine development against SARS-CoV-2. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2021, 137, 111254. [Google Scholar]

- Piperno, A.; Sciortino, M.T.; Giusto, E.; Montesi, M.; Panseri, S.; Scala, A. Recent advances and challenges in gene delivery mediated by polyester-based nanoparticles. International Journal of Nanomedicine 2021, 16, 5981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, V.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, P.C. Recent advances in the vaccine development for the prophylaxis of SARS Covid-19. International Immunopharmacology 2022, 109175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshnood, S.; Arshadi, M.; Akrami, S.; Koupaei, M.; Ghahramanpour, H.; Shariati, A.; Sadeghifard, N.; Heidary, M. An overview on inactivated and live-attenuated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Journal of Clinical Laboratory Analysis 2022, 36, e24418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tebas, P.; Yang, S.; Boyer, J.D.; Reuschel, E.L.; Patel, A.; Christensen-Quick, A.; Andrade, V.M.; Morrow, M.P.; Kraynyak, K.; Agnes, J.; Purwar, M. Safety and immunogenicity of INO-4800 DNA vaccine against SARS-CoV-2: A preliminary report of an open-label, Phase 1 clinical trial. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 31, 100689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrotri, M.; Swinnen, T.; Kampmann, B.; Parker, E.P. An interactive website tracking COVID-19 vaccine development. The Lancet Global Health 2021, 9, e590–e592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Huo, P.; Dai, R.; Lv, X.; Yuan, S.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Li, R.; Yu, Q.; Zhu, K. Convalescent plasma may be a possible treatment for COVID-19: A systematic review. International immunopharmacology 2021, 91, 107262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldeón, M.E.; Maldonado, A.; Ochoa-Andrade, M.; Largo, C.; Pesantez, M.; Herdoiza, M.; Granja, G.; Bonifaz, M.; Espejo, H.; Mora, F.; Abril-López, P. Effect of convalescent plasma as complementary treatment in patients with moderate COVID-19 infection. Transfusion Medicine 2022, 32, 153–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochani, R.; Asad, A.; Yasmin, F.; Shaikh, S.; Khalid, H.; Batra, S.; Sohail, M.R.; Mahmood, S.F.; Ochani, R.; Arshad, M.H.; Kumar, A. COVID-19 pandemic: From origins to outcomes. A comprehensive review of viral pathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnostic evaluation, and management. Infez Med 2021, 29, 20–36. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, B.E.; Brown-Augsburger, P.L.; Corbett, K.S.; Westendorf, K.; Davies, J.; Cujec, T.P.; Wiethoff, C.M.; Blackbourne, J.L.; Heinz, B.A.; Foster, D.; Higgs, R.E. The neutralizing antibody, LY-CoV555, protects against SARS-CoV-2 infection in nonhuman primates. Science translational medicine 2021, 13, eabf1906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahoo, P.; Dey, J.; Mahapatra, S.R.; Ghosh, A.; Jaiswal, A.; Padhi, S.; Prabhuswamimath, S.C.; Misra, N.; Suar, M. Nanotechnology and COVID-19 Convergence: Toward New Planetary Health Interventions Against the Pandemic. OMICS: A Journal of Integrative Biology 2022, 26, 473–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Michler, T.; Merkel, O.M. siRNA Therapeutics against Respiratory Viral Infections—What Have We Learned for Potential COVID-19 Therapies? . Advanced healthcare materials 2021, 10, 2001650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M.; Mustafa, F.; Rizvi, T.A.; Loney, T.; Al Suwaidi, H.; Al-Marzouqi, A.H.H.; Kamal Eldin, A.; Alsabeeha, N.; Adrian, T.E.; Stefanini, C.; Nowotny, N. SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19: Viral genomics, epidemiology, vaccines, and therapeutic interventions. Viruses 2020, 12, 526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Peng, F.; Wang, R.; Guan, K.; Jiang, T.; Xu, G.; Sun, J.; Chang, C. The deadly coronaviruses: The 2003 SARS pandemic and the 2020 novel coronavirus epidemic in China. Journal of autoimmunity 2020, 109, 102434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Penninger, J.M.; Li, Y.; Zhong, N.; Slutsky, A.S. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as a SARS-CoV-2 receptor: Molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutic target. Intensive care medicine 2020, 46, 586–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourgonje, A.R.; Abdulle, A.E.; Timens, W.; Hillebrands, J.L.; Navis, G.J.; Gordijn, S.J.; Bolling, M.C.; Dijkstra, G.; Voors, A.A.; Osterhaus, A.D.; van Der Voort, P.H. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), SARS-CoV-2 and the pathophysiology of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). The Journal of pathology 2020, 251, 228–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedpour, S.; Khodaei, B.; Loghman, A.H.; Seyedpour, N.; Kisomi, M.F.; Balibegloo, M.; Nezamabadi, S.S.; Gholami, B.; Saghazadeh, A.; Rezaei, N. Targeted therapy strategies against SARS-CoV-2 cell entry mechanisms: A systematic review of in vitro and in vivo studies. Journal of cellular physiology 2021, 236, 2364–2392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ita, K. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Current status and prospects for drug and vaccine development. Archives of Medical Research 2021, 52, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miners, S.; Kehoe, P.G.; Love, S. Cognitive impact of COVID-19: Looking beyond the short term. Alzheimer's research & therapy 2020, 12, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Abd El-Aziz, T.M.; Al-Sabi, A.; Stockand, J.D. Human recombinant soluble ACE2 (hrsACE2) shows promise for treating severe COVID19. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy 2020, 5, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanganeh, S.; Goodarzi, N.; Doroudian, M.; Movahed, E. Potential COVID-19 therapeutic approaches targeting angiotensin-converting enzyme 2; an updated review. Reviews in Medical Virology 2022, 32, e2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, P.C.; Liew, D.F.; Tanner, H.L.; Grainger, J.R.; Dwek, R.A.; Reisler, R.B.; Steinman, L.; Feldmann, M.; Ho, L.P.; Hussell, T.; Moss, P. COVID-19 therapeutics: Challenges and directions for the future. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2022, 119, e2119893119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kustin, T.; Harel, N.; Finkel, U.; Perchik, S.; Harari, S.; Tahor, M.; Caspi, I.; Levy, R.; Leshchinsky, M.; Ken Dror, S.; Bergerzon, G. Evidence for increased breakthrough rates of SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in BNT162b2-mRNA-vaccinated individuals. Nature medicine 2021, 27, 1379–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, R.; Heng, K.; Shawon, M.S.R.; Goh, G.; Okonofua, D.; Ochoa-Rosales, C.; Gonzalez-Jaramillo, V.; Bhuiya, A.; Reidpath, D.; Prathapan, S.; Shahzad, S. Dynamic interventions to control COVID-19 pandemic: A multivariate prediction modelling study comparing 16 worldwide countries. European journal of epidemiology 2020, 35, 389–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, S.; Liu, R.; Krall, A.; Wang, Y.; Ventura, M.; Deflitch, C. Epidemic informatics and control: A holistic approach from system informatics to epidemic response and risk management in public health. In AI and Analytics for Public Health- Proceedings of the 2020 INFORMS International Conference on Service Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021; pp. 1–46. [Google Scholar]

- Di Domenico, L.; Pullano, G.; Sabbatini, C.E.; Boëlle, P.Y.; Colizza, V. Impact of lockdown on COVID-19 epidemic in Île-de-France and possible exit strategies. BMC medicine 2020, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinn, G.A.; Connolly, R.; ÓhAiseadha, C.; Hynds, P. ; 2021. A tale of two scientific paradigms: Conflicting scientific opinions on what “following the science” means for SARS-CoV-2 and the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Behera, R.K.; Bala, P.K.; Rana, N.P.; Kayal, G. Self-promotion and online shaming during COVID-19: A toxic combination. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights 2022, 2, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez-Brito, A.; El Bcheraoui, C.; Pozo-Martin, F. Systematic review of empirical studies comparing the effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical interventions against COVID-19. Journal of Infection 2021, 83, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanson, K.E.; Caliendo, A.M.; Arias, C.A.; Englund, J.A.; Lee, M.J.; Loeb, M.; Patel, R.; El Alayli, A.; Kalot, M.A.; Falck-Ytter, Y.; Lavergne, V. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines on the diagnosis of coronavirus disease 2019. Clinical infectious diseases. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Sala, G.; Chakraborti, R.; Ota, A.; Miyakawa, T. Association of BCG vaccination policy and tuberculosis burden with incidence and mortality of COVID-19. Medrxiv 2020, 2020-03. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, V.C.C.; Wong, S.C.; Chuang, V.W.M.; So, S.Y.C.; Chen, J.H.K.; Sridhar, S.; To, K.K.W.; Chan, J.F.W.; Hung, I.F.N.; Ho, P.L.; Yuen, K.Y. The role of community-wide wearing of face mask for control of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic due to SARS-CoV-2. Journal of Infection 2020, 81, 107–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- To, K.K.W.; Sridhar, S.; Chiu, K.H.Y.; Hung, D.L.L.; Li, X.; Hung, I.F.N.; Tam, A.R.; Chung, T.W.H.; Chan, J.F.W.; Zhang, A.J.X.; Cheng, V.C.C. Lessons learned 1 year after SARS-CoV-2 emergence leading to COVID-19 pandemic. Emerging microbes & infections 2021, 10, 507–535. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, 2021. Genomic sequencing of SARS-CoV-2: A guide to implementation for maximum impact on public health, 8 January.

- Dumache, R.; Enache, A.; Macasoi, I.; Dehelean, C.A.; Dumitrascu, V.; Mihailescu, A.; Popescu, R.; Vlad, D.; Vlad, C.S.; Muresan, C. Sars-Cov-2: An overview of the genetic profile and vaccine effectiveness of the five variants of concern. Pathogens 2022, 11, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salvatore, M.; Purkayastha, S.; Ganapathi, L.; Bhattacharyya, R.; Kundu, R.; Zimmermann, L.; Ray, D.; Hazra, A.; Kleinsasser, M.; Solomon, S.; Subbaraman, R. Lessons from SARS-CoV-2 in India: A data-driven framework for pandemic resilience. Science Advances 2022, 8, eabp8621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, J.A.; Ahmed, S.; Mir, A.; Shinde, M.; Bender, O.; Alshammari, F.; Ansari, M.; Anwar, S. The SARS-CoV-2 mutation versus vaccine effectiveness: New opportunities to new challenges. Journal of infection and public health 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gulseven, O.; Al Harmoodi, F.; Al Falasi, M.; ALshomali, I. How the COVID-19 pandemic will affect the UN sustainable development goals? Available at SSRN 359. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shohel, M.M.C.; Ashrafuzzaman, M.; Alam, A.S.; Mahmud, A.; Ahsan, M.S.; Islam, M.T. Preparedness of students for future teaching and learning in higher education: A Bangladeshi perspective. In New Student Literacies amid COVID-19: International Case Studies; Emerald Publishing Limited, 2021; Volume 41, pp. 29–56. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).