Submitted:

19 August 2023

Posted:

22 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2.0. Methods

2.1. Case of interest definition

2.2. Exposure definition

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3.0. Results

3.2. Disproportionality analysis

3.3. Characteristics of insomnia reports

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Morales P, Hurst DP, Reggio PH. Molecular Targets of the Phytocannabinoids: A Complex Picture. Prog Chem Org Nat Prod. 2017;103:103-131. [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg EC, Tsien RW, Whalley BJ, Devinsky O. Cannabinoids and Epilepsy. Neurotherapeutics. 2015;12(4):747-68. [CrossRef]

- Galaj E, Xi ZX. Possible Receptor Mechanisms Underlying Cannabidiol Effects on Addictive-like Behaviors in Experimental Animals. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;22(1):134. [CrossRef]

- de Almeida DL, Devi LA. Diversity of molecular targets and signaling pathways for CBD. Pharmacol Res Perspect. 2020;8(6):e00682. [CrossRef]

- Freeman TP, Craft S, Wilson J, Stylianou S, ElSohly M, Di Forti M, Lynskey MT. Changes in delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD) concentrations in cannabis over time: systematic review and meta-analysis. Addiction. 2021;116(5):1000-1010. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salehi A, Puchalski K, Shokoohinia Y, Zolfaghari B, Asgary S. Differentiating Cannabis Products: Drugs, Food, and Supplements. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:906038. [CrossRef]

- Costa, B. On the pharmacological properties of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC). Chem Biodivers. 2007;4(8):1664-77. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calapai F, Cardia L, Sorbara EE, Navarra M, Gangemi S, Calapai G, Mannucci C. Cannabinoids, Blood-Brain Barrier, and Brain Disposition. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(3):265. [CrossRef]

- Britch SC, Babalonis S, Walsh SL. Cannabidiol: pharmacology and therapeutic targets. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2021;238(1):9-28. [CrossRef]

- Mannucci C, Navarra M, Calapai F, Spagnolo EV, Busardò FP, Cas RD, Ippolito FM, Calapai G. Neurological Aspects of Medical Use of Cannabidiol. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2017;16(5):541-553. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calapai G, Mannucci C, Chinou I, Cardia L, Calapai F, Sorbara EE, Firenzuoli B, Ricca V, Gensini GF, Firenzuoli F. Preclinical and Clinical Evidence Supporting Use of Cannabidiol in Psychiatry. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019;2019:2509129. [CrossRef]

- Pertwee, RG. The diverse CB1 and CB2 receptor pharmacology of three plant cannabinoids: delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol, cannabidiol and delta9-tetrahydrocannabivarin. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;153(2):199-215. [CrossRef]

- Granja AG, Carrillo-Salinas F, Pagani A, Gómez-Cañas M, Negri R, Navarrete C, Mecha M, Mestre L, Fiebich BL, Cantarero I, Calzado MA, Bellido ML, Fernandez-Ruiz J, Appendino G, Guaza C, Muñoz E. A cannabigerol quinone alleviates neuroinflammation in a chronic model of multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2012;7(4):1002-16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ryberg E, Larsson N, Sjögren S, Hjorth S, Hermansson NO, Leonova J, Elebring T, Nilsson K, Drmota T, Greasley PJ. The orphan receptor GPR55 is a novel cannabinoid receptor. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152(7):1092-101. [CrossRef]

- De Petrocellis L, Ligresti A, Moriello AS, Allarà M, Bisogno T, Petrosino S, Stott CG, Di Marzo V. Effects of cannabinoids and cannabinoid-enriched Cannabis extracts on TRP channels and endocannabinoid metabolic enzymes. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163(7):1479-94. [CrossRef]

- De Petrocellis L, Schiano Moriello A, Imperatore R, Cristino L, Starowicz K, Di Marzo V. A re-evaluation of 9-HODE activity at TRPV1 channels in comparison with anandamide: enantioselectivity and effects at other TRP channels and in sensory neurons. Br J Pharmacol. 2012;167(8):1643-51. [CrossRef]

- Pandolfo P, Silveirinha V, dos Santos-Rodrigues A, Venance L, Ledent C, Takahashi RN, Cunha RA, Köfalvi A. Cannabinoids inhibit the synaptic uptake of adenosine and dopamine in the rat and mouse striatum. Eur J Pharmacol. 2011;655(1-3):38-45. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castillo A, Tolón MR, Fernández-Ruiz J, Romero J, Martinez-Orgado J. The neuroprotective effect of cannabidiol in an in vitro model of newborn hypoxic-ischemic brain damage in mice is mediated by CB(2) and adenosine receptors. Neurobiol Dis. 2010;37(2):434-40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kathmann M, Flau K, Redmer A, Tränkle C, Schlicker E. Cannabidiol is an allosteric modulator at mu- and delta-opioid receptors. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 2006;372(5):354-61. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu C, Zhang Y, Gozal D, Carney P. Channelopathy of Dravet Syndrome and Potential Neuroprotective Effects of Cannabidiol. J Cent Nerv Syst Dis. 2021;13:11795735211048045. [CrossRef]

- Russo EB, Burnett A, Hall B, Parker KK. Agonistic properties of cannabidiol at 5-HT1a receptors. Neurochem Res. 2005;30(8):1037-43. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harrison C, Traynor JR. The [35S]GTPgammaS binding assay: approaches and applications in pharmacology. Life Sci. 2003;74(4):489-508. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Russo, EB. Clinical endocannabinoid deficiency (CECD): can this concept explain therapeutic benefits of cannabis in migraine, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome and other treatment-resistant conditions? Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2008;29(2):192-200. [PubMed]

- Müller CP, Homberg JR. The role of serotonin in drug use and addiction. Behav Brain Res. 2015;277:146-92. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaseghi S, Arjmandi-Rad S, Nasehi M, Zarrindast MR. Cannabinoids and sleep-wake cycle: The potential role of serotonin. Behav Brain Res. 2021;412:113440. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Resstel LB, Tavares RF, Lisboa SF, Joca SR, Corrêa FM, Guimarães FS. 5-HT1A receptors are involved in the cannabidiol-induced attenuation of behavioural and cardiovascular responses to acute restraint stress in rats. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;156(1):181-8. [CrossRef]

- epidyolex-epar-risk-management-plan-summary_en.pdf. Accessed , 2023. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/rmp-summary/epidyolex-epar-risk-management-plan-summary_en. 15 July.

- Ammendolia I, Mannucci C, Cardia L, Calapai G, Gangemi S, Esposito E, Calapai F. Pharmacovigilance on cannabidiol as an antiepileptic agent. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1091978. [CrossRef]

- Lindquist, M. Use of triage strategies in the WHO signal-detection process. Drug Saf. 2007;30(7):635-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MedDRA Hierarchy | MedDRA. Accessed , 2023. https://www.meddra.org/how-to-use/basics/hierarchy. 15 July.

- Bate A, Evans SJ. Quantitative signal detection using spontaneous ADR reporting. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2009; 18(6):427-436.

- Faillie, JL. Case-non-case studies: Principle, methods, bias and interpretation. Therapie. 2019;74(2):225-232. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trillenberg P, Sprenger A, Machner B. Sensitivity and specificity in signal detection with the reporting odds ratio and the information component. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2023;32(8):910-917. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/epidyolex-epar-product-information_en.pdf; accessed on 4 august 2023.

- Hauben M, Zhou X. Quantitative methods in pharmacovigilance: focus on signal detection. Drug Saf. 2003;26(3):159-86. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palapra H, Viswam SK, Kalaiselvan V, Undela K. SGLT2 inhibitors associated pancreatitis: signal identification through disproportionality analysis of spontaneous reports and review of case reports. Int J Clin Pharm. 2022;44(6):1425-1433. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blake MJ, Trinder JA, Allen NB. Mechanisms underlying the association between insomnia, anxiety, and depression in adolescence: Implications for behavioral sleep interventions. Clin Psychol Rev. 2018;63:25-40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suraev AS, Marshall NS, Vandrey R, McCartney D, Benson MJ, McGregor IS, Grunstein RR, Hoyos CM. Cannabinoid therapies in the management of sleep disorders: A systematic review of preclinical and clinical studies. Sleep Med Rev. 2020;53:101339. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linares IMP, Guimaraes FS, Eckeli A, Crippa ACS, Zuardi AW, Souza JDS, Hallak JE, Crippa JAS. No Acute Effects of Cannabidiol on the Sleep-Wake Cycle of Healthy Subjects: A Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Crossover Study. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:315. [CrossRef]

- Geffrey AL, Pollack SF, Bruno PL, Thiele EA. Drug-drug interaction between clobazam and cannabidiol in children with refractory epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2015;56(8):1246-51. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Taylor L, Gidal B, Blakey G, Tayo B, Morrison G. A Phase I, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Single Ascending Dose, Multiple Dose, and Food Effect Trial of the Safety, Tolerability and Pharmacokinetics of Highly Purified Cannabidiol in Healthy Subjects. CNS Drugs. 2018;32(11):1053-1067. Erratum in: CNS Drugs. 2019;33(4):397. PMID: 30374683; PMCID: PMC6223703. [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Rodríguez, E. The role of the CB1 receptor in the regulation of sleep. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(6):1420-7. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jouvet, M. Sleep and serotonin: an unfinished story. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;21(2 Suppl):24S-27S. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blier P, Piñeyro G, el Mansari M, Bergeron R, de Montigny C. Role of somatodendritic 5-HT autoreceptors in modulating 5-HT neurotransmission. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;861:204-16. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raymond JR, Mukhin YV, Gettys TW, Garnovskaya MN. The recombinant 5-HT1A receptor: G protein coupling and signalling pathways. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127(8):1751-64. [CrossRef]

- Pompeiano M, Palacios JM, Mengod G. Distribution and cellular localization of mRNA coding for 5-HT1A receptor in the rat brain: correlation with receptor binding. J Neurosci. 1992;12(2):440-53. [CrossRef]

- Berumen LC, Rodríguez A, Miledi R, García-Alcocer G. Serotonin receptors in hippocampus. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:823493. [CrossRef]

- Brown JW, Sirlin EA, Benoit AM, Hoffman JM, Darnall RA. Activation of 5-HT1A receptors in medullary raphé disrupts sleep and decreases shivering during cooling in the conscious piglet. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294(3):R884-94. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toth, M. 5-HT1A receptor knockout mouse as a genetic model of anxiety. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;463(1-3):177-84. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Artigas, F. Developments in the field of antidepressants, where do we go now? Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;25(5):657-70. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneses A, Hong E. Mechanism of action of 8-OH-DPAT on learning and memory. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1994;49(4):1083-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjorvatn B, Fagerland S, Eid T, Ursin R. Sleep/waking effects of a selective 5-HT1A receptor agonist given systemically as well as perfused in the dorsal raphe nucleus in rats. Brain Res. 1997;770(1-2):81-8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiske E, Portas CM, Grønli J, Sørensen E, Bjorvatn B, Bjørkum AA, Ursin R. Increased extracellular 5-HT but no change in sleep after perfusion of a 5-HT1A antagonist into the dorsal raphe nucleus of rats. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2008;193(1):89-97. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Main characteristics | N° cases (820) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Patient age | ||

| 28 days-23 months | 1 | 0.1% |

| 2 - 11 years | 23 | 2.8% |

| 12 - 17 years | 23 | 2.8% |

| 18 - 44 years | 57 | 7.0% |

| 45 - 64 years | 18 | 2.2% |

| 65 - 74 years | 6 | 0.7% |

| ≥ 75 years | 6 | 0.7% |

| Unknown | 685 | 83.5% |

| 28 days-23 months | 1 | 0.1% |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 149 | 18.2% |

| Female | 147 | 17.9% |

| Unknown | 524 | 63.9% |

| Countries | ||

| Usa | 754 | 92.0% |

| UK | 18 | 2.2% |

| France | 12 | 1.5% |

| Germany | 8 | 1.0% |

| other countries | 28 | 3.4% |

| Reporter qualification | ||

| Physician | 154 | 18.8% |

| Pharmacist | 22 | 2.7% |

| Other Health Professional | 179 | 21.8% |

| Consumer/Non Health Professional | 463 | 56.5% |

| Unknown | 8 | 1.0% |

| Drug/Product | ||

| Epidiolex | 753 | 91.8% |

| Unknown (Cannabidiol) | 47 | 5.7% |

| CBD oil | 15 | 1.8% |

| Convupidiol (Argentina) | 3 | 0.4% |

| Xannadiol (Uruguay) | 2 | 0.2% |

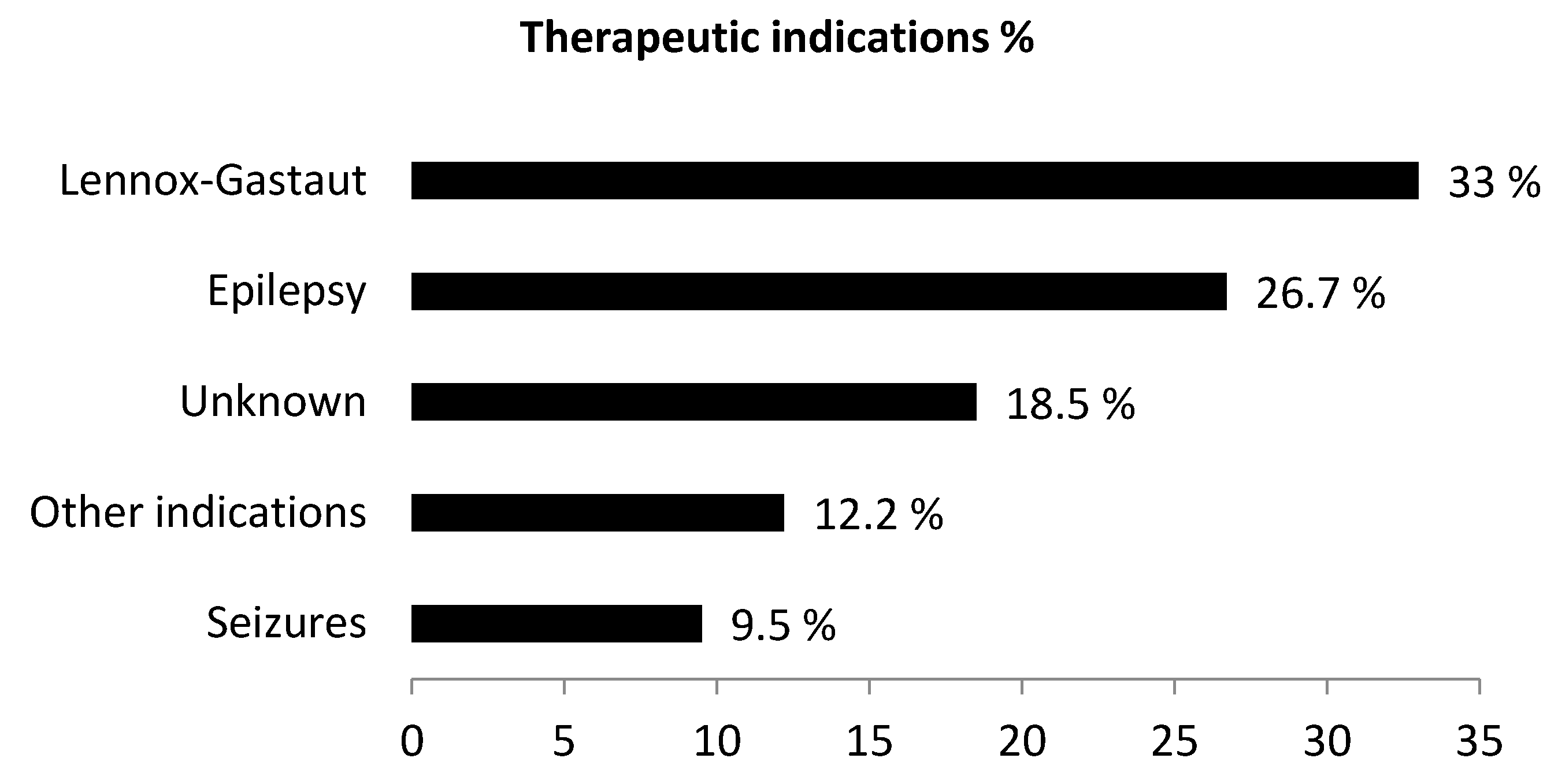

| Indication | ||

| Epilepsy NOS | 200 | 24.4% |

| Lennox Gastaut Syndrome | 315 | 38.4% |

| Seizures | 40 | 4.9% |

| Parzial seizure | 41 | 5% |

| Idiopatic epilepsy | 34 | 4.1% |

| Tuberous Sclerosis Complex | 11 | 1.3% |

| Product use for unknown indication | 79 | 9.6% |

| Other indications | 100 | 12.2% |

| Serious/non serious adverse reactions | ||

| Yes | 233 | 28.4% |

| No | 587 | 71.6% |

| Adverse reaction | N. of cases | ROR (95% CI) |

IC (IC025) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weight decreased | 456 | 5.19° (4.54 - 5.70) |

2.4* (2.2) |

| Hypophagia | 30 | 3.68° (3.22 - 5.27) |

1.8* (1.3) |

| Insomnia | 221 | 1.60° (1.40 - 1.83) |

0.7* (0.5) |

| Dizziness | 118 | 0.23 (0.20 - 0.27) |

- 2.1 (-2.4) |

| Palpitations | 16 | 0.12 (0.10 - 0.19) |

- 3.1 (-3.9) |

| Main characteristics | N° cases (221) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Patient age | ||

| 2 - 11 years | 8 | 3.6% |

| 12 - 17 years | 5 | 2.3% |

| 18 - 44 years | 4 | 1.8% |

| 45 - 64 years | 4 | 1.8% |

| 65 - 74 years | 2 | 0.9% |

| ≥ 75 years | 2 | 0.9% |

| Unknown | 196 | 88.7% |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 28 | 12.7% |

| Female | 25 | 11.3% |

| Unknown | 168 | 76.0% |

| Drug/Product | ||

| Epidiolex | 206 | 93.2% |

| Unknown Cannabidiol | 11 | 5.0% |

| CBD oil | 2 | 0.9% |

| Convupidiol (Argentina) | 2 | 0.9% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).