Submitted:

20 August 2023

Posted:

22 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

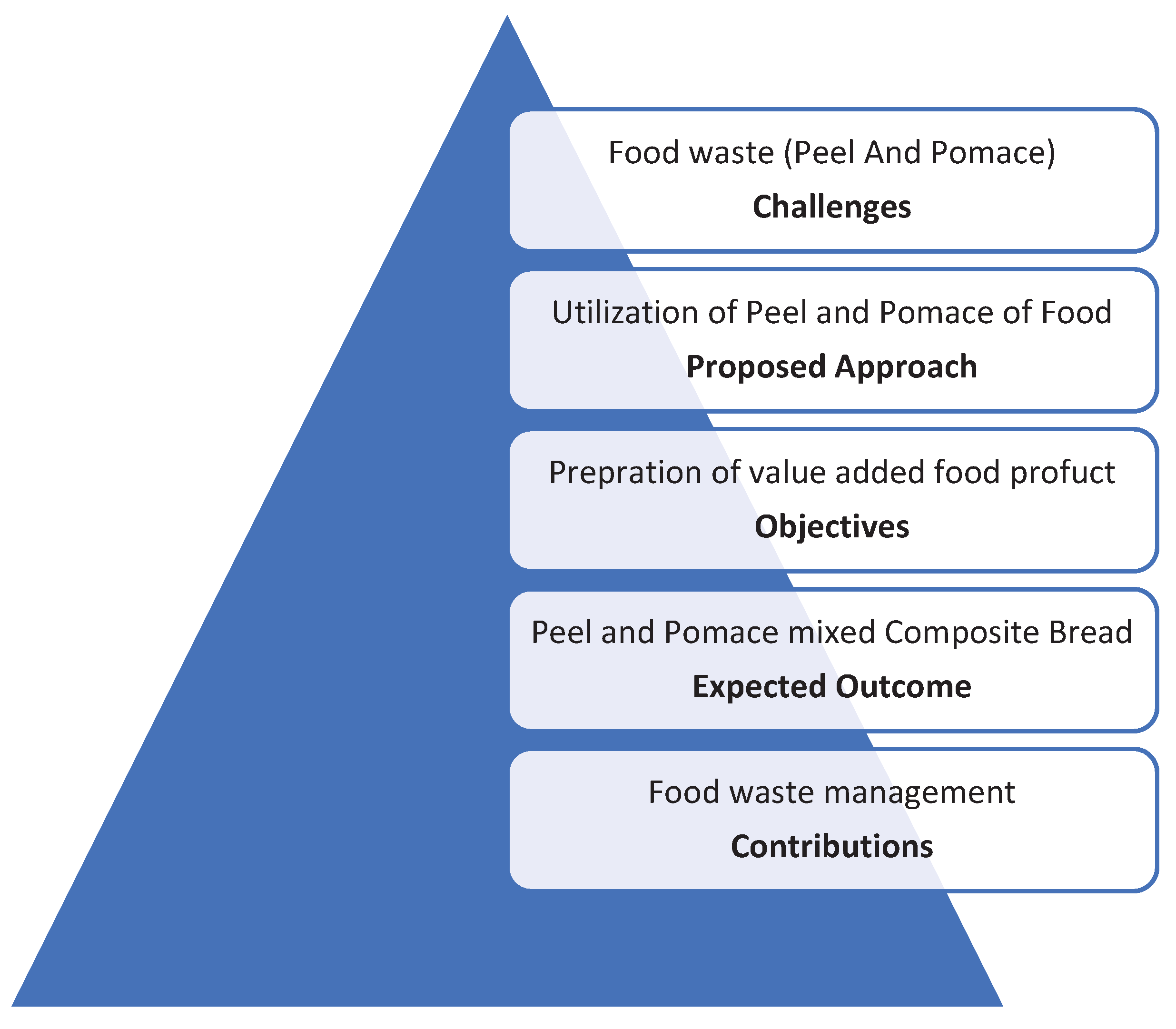

1. Introduction

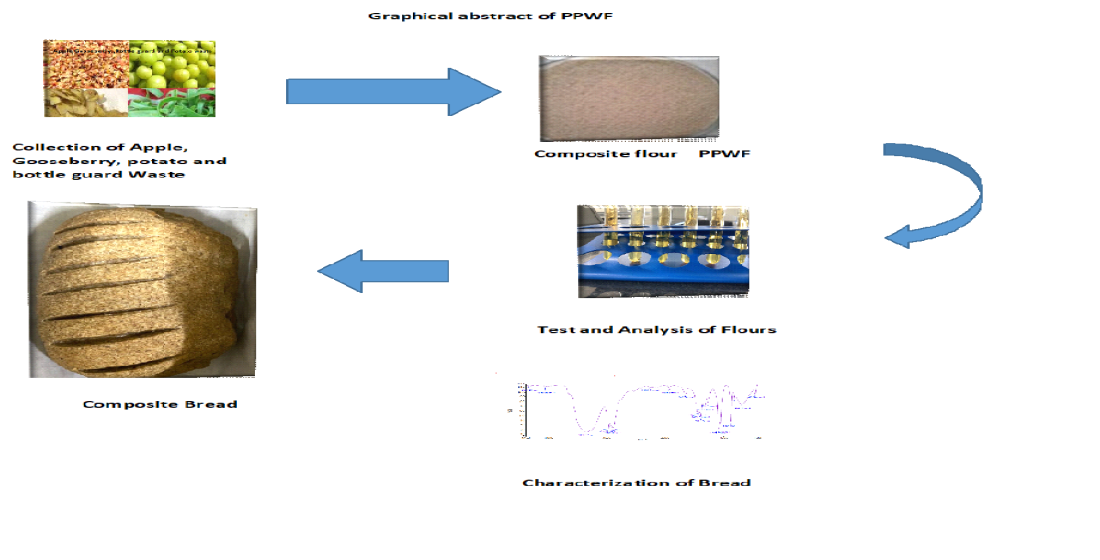

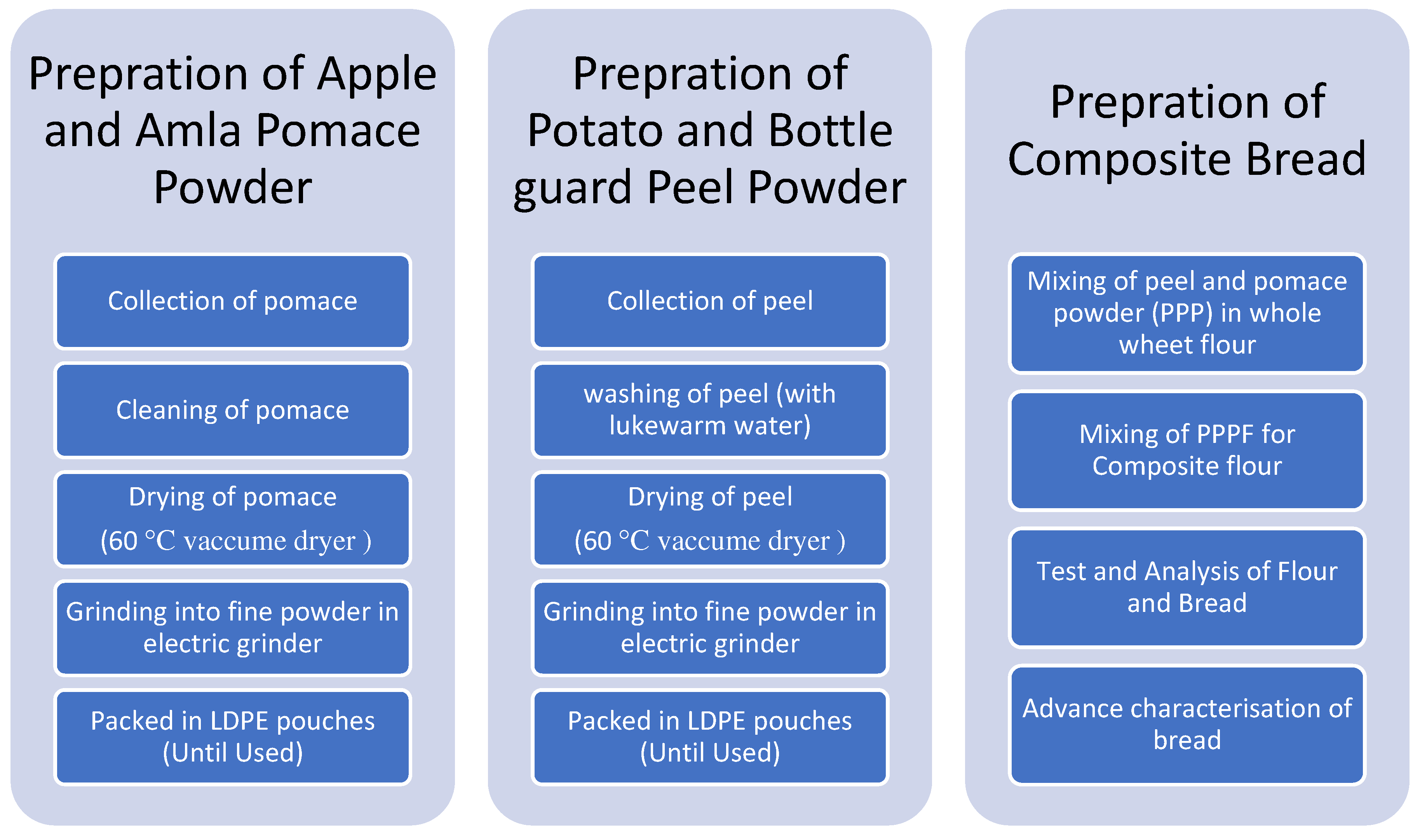

2. Material and method

2.1. Procurement of raw material

2.2. Preparation of peel and pomace powder (PPP):

2.3. Preparation of peel and pomace powder composite flour

2.4. Preparation of bread

2.5. Nutritional evaluations

2.5.1. Total Phenolic Content Analysis

2.5.2. Ascorbic Acid Analysis

2.5.3. Total sugar analysis:

2.6. Functional Analysis

2.6.1. Water Absorption Capacity

2.6.2. Oil Absorption Capacity

2.6.3. Swelling Capacity

2.6.4. Emulsion Capacity

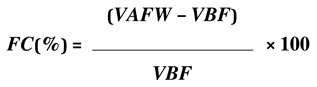

2.6.5. Foam Capacity:

2.7. Physical Analysis

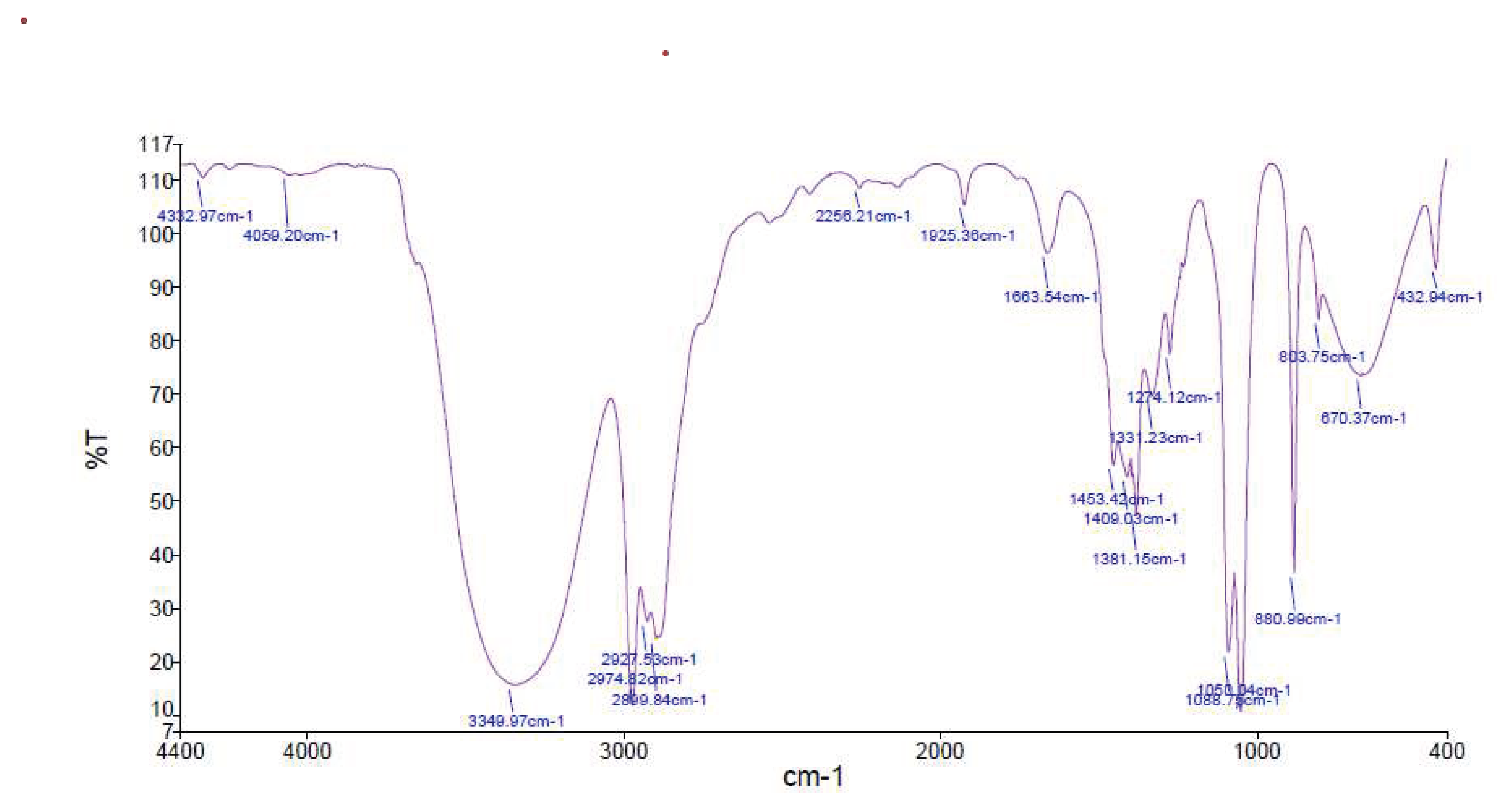

2.8. FTIR Analysis:

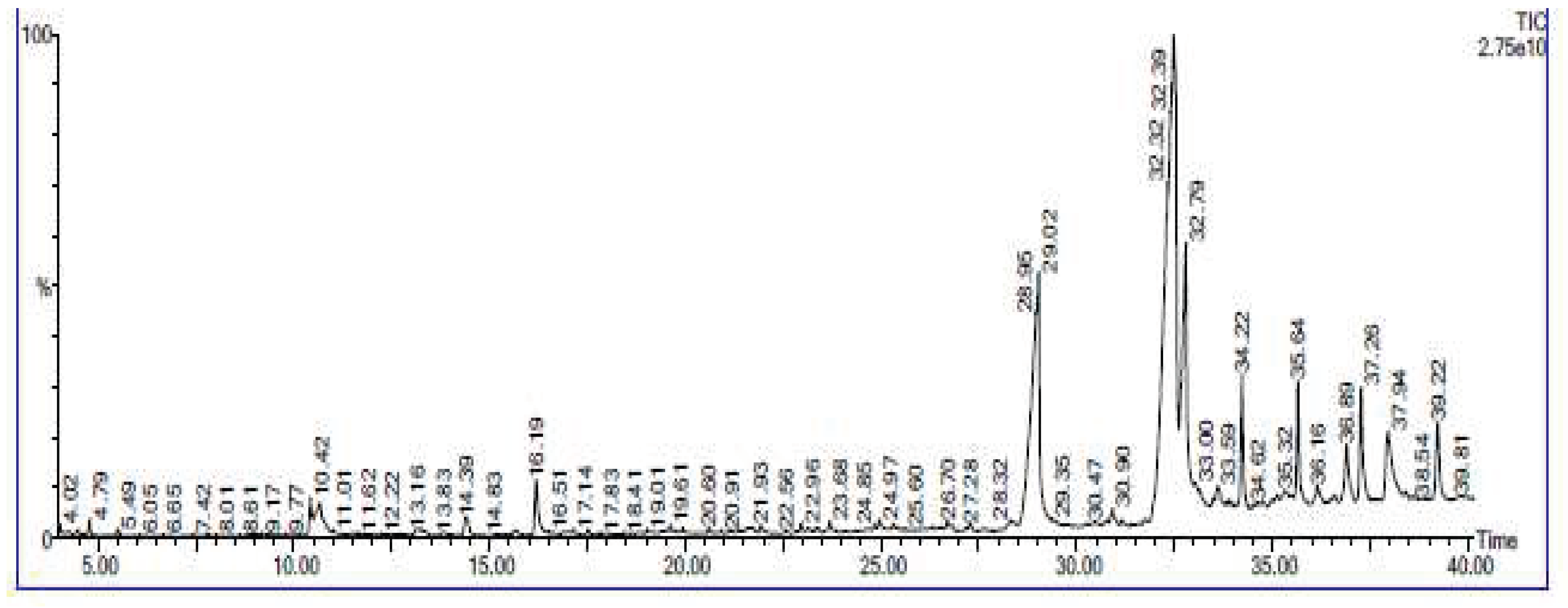

2.9. GC–MS Analysis:

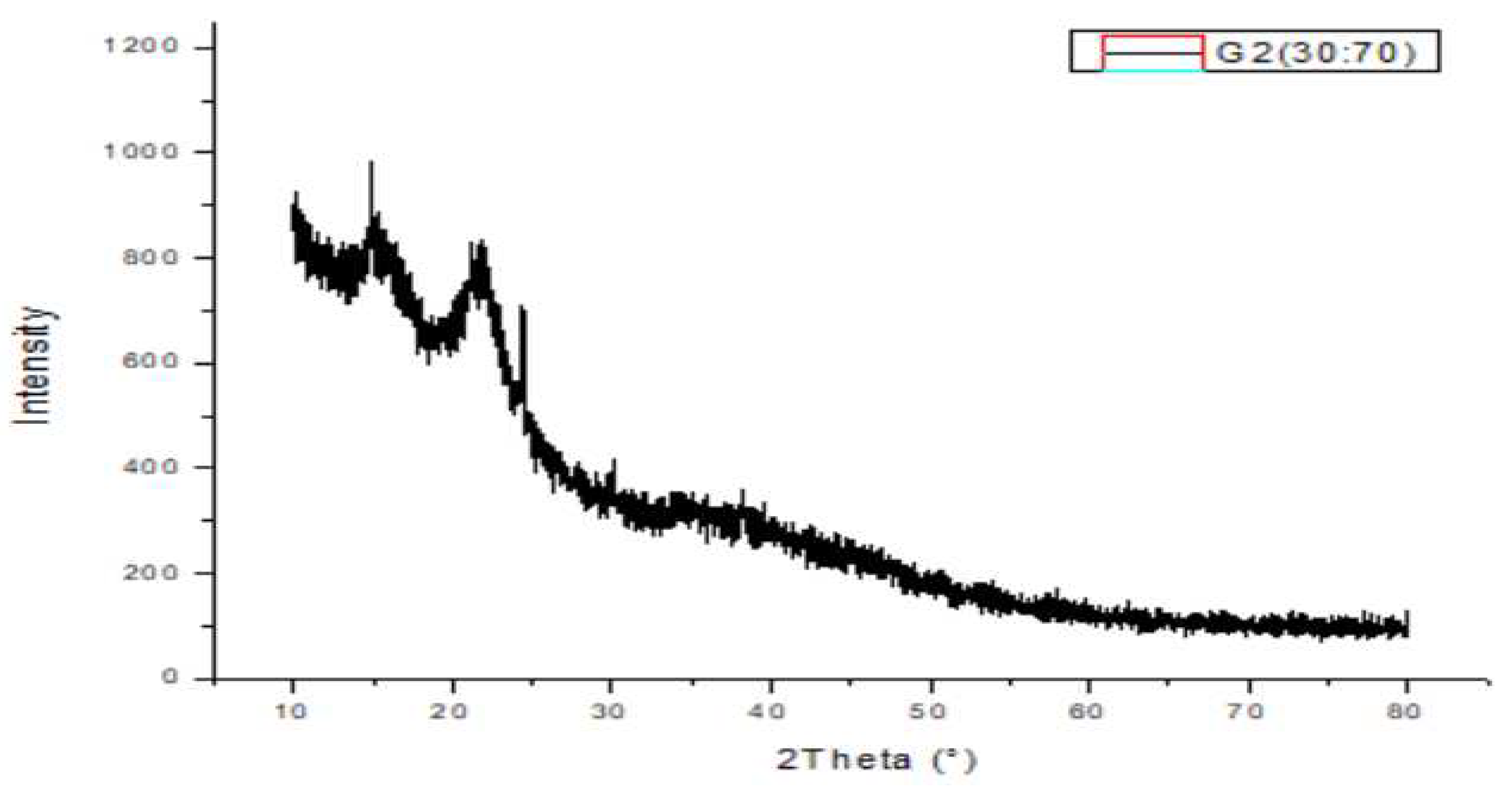

2.10. XRD Analysis:

2.11. Sensory Analysis:

2.12. Statistical Analysis

Hypothesis Conducted

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Nutritional analysis result

3.2. Functional Analysis

3.2.1. Water absorption capacity (WAC)

3.2.2. Oil Absorption Capacity (OAC):

3.2.3. Swelling capacity results

3.2.4. Emulsion capacity results

3.2.5. Foaming capacity results

| Parameters | PPWF1 | PPWF2 | PPWF3 | PPWF4 | Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swelling capacity(mL) | 17.30±1.85 | 18.20±0.81 | 20.18±0.71 | 19.45±0.56 | 11.77±0.51 |

| Emulsion capacity (%) | 47.88±5.12 | 48.88±4.12 | 41.88±3.52 | 33.88±5.12 | 23.88±4.12 |

| Foaming capacity (%) | 20.72±5.03 | 21.12±4.7 | 24.66±5.5 | 25.36±5.77 | 12.42±5.3 |

3.3. Physical analysis results

3.4. FTIR analysis results:

3.5. GC-MS analysis results:

3.6. XRD analysis result:

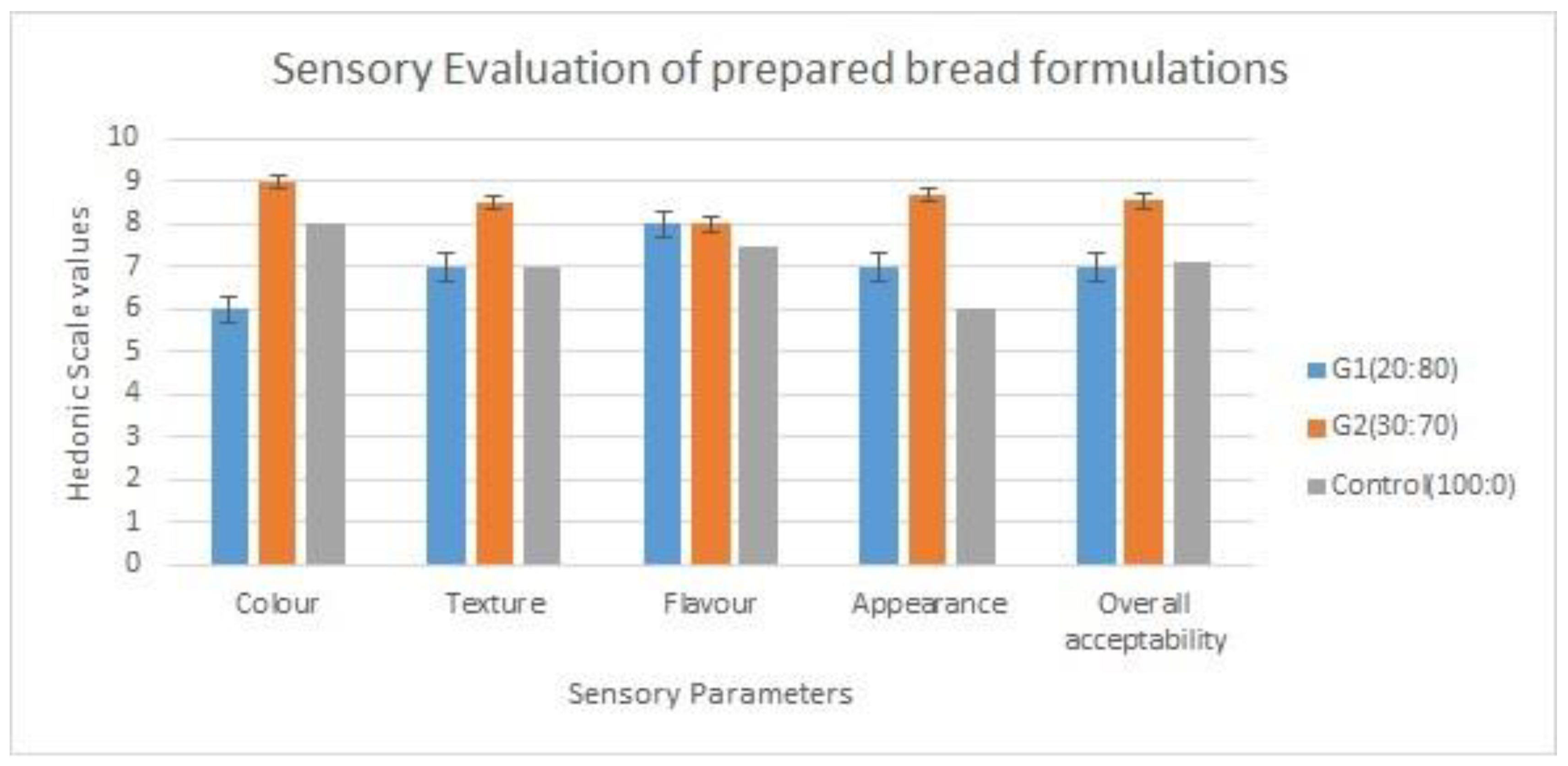

3.7. Sensory evaluation results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- P. Morone, A. Koutinas, N. Gathergood, M. Arshadi, and A. Matharu, “Food waste: Challenges and opportunities for enhancing the emerging bio-economy,” J. Clean. Prod., vol. 221, pp. 10–16, 2019. [CrossRef]

- H. Forbes, T. Quested, and C. O’Connor, “Food Waste Index Report 2021,” United Nations Environ. Program. Nairobi, Kenya, 2021.

- Y. M. Yun et al., “Biohydrogen production from food waste: Current status, limitations, and future perspectives,” Bioresour. Technol., vol. 248, pp. 79–87, 2018. [CrossRef]

- Rico, X., Gullón, B., Alonso, J.L. and Yáñez, R., 2020. Recovery of high value-added compounds from pineapple, melon, watermelon and pumpkin processing by-products: An overview. Food Research International, 132, p.109086, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Shahidi, F., Varatharajan, V., Peng, H. and Senadheera, R., Utilization of marine by-products for the recovery of value-added products. Journal of Food Bioactives, Vol 6, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. M. Mishra, S. Harnal, V. Gautam, R. Tiwari, and S. Upadhyay, “Weed density estimation in soya bean crop using deep convolutional neural networks in smart agriculture,” J. Plant Dis. Prot., vol. 129, no. 3, pp. 593–604, 2022. [CrossRef]

- N. Gaurav, “Current scenario and future perspectives of nanotechnology in sustainable agriculture and food production,” 2021.

- M. Nagaraju, P. Chawla, S. Upadhyay, and R. Tiwari, “Convolution network model based leaf disease detection using augmentation techniques,” Expert Syst., vol. 39, no. 4, p. e12885, 2022. [CrossRef]

- M. Shashikant et al., “In-vitro antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory activity of modified solvent evaporated ethanolic extract of Calocybe indica: GCMS and HPLC characterization,” Int. J. Food Microbiol., vol. 376, p. 109741, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. P. Cauvain, “Other cereals in breadmaking,” in Technology of Breadmaking, Springer, 2007, pp. 371–388.

- A. Walia et al., “Bioactive compounds in Ficus fruits, their bioactivities, and associated health benefits: a review,” J. Food Qual., vol. 2022, pp. 1–19, 2022. [CrossRef]

- A. Sridhar, A. Kapoor, P. Senthil, M. Ponnuchamy, S. Balasubramanian, and S. Prabhakar, “Conversion of food waste to energy : A focus on sustainability and life cycle assessment,” Fuel, no. March, p. 121069, 2021. [CrossRef]

- V. Kumar et al., “Production of high value-added biomolecules by microalgae cultivation in wastewater from anaerobic digestates of food waste: a review,” Biomass Convers. Biorefinery, pp. 1–18, 2021. [CrossRef]

- C. E. Lister, J. E. Lancaster, and J. R. L. Walker, “Phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL) activity and its relationship to anthocyanin and flavonoid levels in New Zealand-grown apple cultivars,” J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci., vol. 121, no. 2, pp. 281–285, 1996. [CrossRef]

- Tulasi, G., U. Deepika, P. Venkateshwarlu, V. Santhosh, and P. Srilatha. "Development of millet based instant soup mix and Pulav mix." IJCS vol 8, no. 5, pp. 832-835, 2020. [CrossRef]

- R. R. Gajera, D. C. Joshi, and A. Ravani, “Processing potential of bottle gourd (L. siceraria) Fruits: An overview,” Int J Herb Med, vol. 16, pp. 16–40, 2017.

- A. Javed, A. Ahmad, A. Tahir, U. Shabbir, M. Nouman, and A. Hameed, “Potato peel waste-its nutraceutical, industrial and biotechnological applacations,” AIMS Agric. Food, vol. 4, no. 3, pp. 807–823, 2019. [CrossRef]

- A. Torbica, K. M. Blažek, M. Belović, and E. J. Hajnal, “Quality prediction of bread made from composite flours using different parameters of empirical rheology,” J. Cereal Sci., vol. 89, p. 102812, 2019. [CrossRef]

- E. I. Ohimain, “The prospects and challenges of cassava inclusion in wheat bread policy in Nigeria,” Int. J. Sci. Technol. Soc., vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 6–17, 2014. [CrossRef]

- T. A. Shittu, A. O. Raji, and L. O. Sanni, “Bread from composite cassava-wheat flour: I. Effect of baking time and temperature on some physical properties of bread loaf,” Food Res. Int., vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 280–290, 2007. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Chowdhury et al., “A comparative study on the chemical composition of wild and cuntivated germaplasm of Phaseolus lunatus L.,” Waste Manag., vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 296–305, Feb. 2020. [CrossRef]

- V. Kumar, A. K. Sinha, H. P. S. Makkar, and K. Becker, “Dietary roles of phytate and phytase in human nutrition: A review,” Food Chem., vol. 120, no. 4, pp. 945–959, 2010. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Chowdhury, N. Hossain, M. A. Kashem, M. A. Shahid, and A. Alam, “Immune response in COVID-19: A review,” J. Infect. Public Health, 2020. [CrossRef]

- F. Aman and S. Masood, “How Nutrition can help to fight against COVID-19 Pandemic,” Pakistan J. Med. Sci., vol. 36, no. COVID19-S4, p. S121, 2020. [CrossRef]

- H.-W. Xiao et al., “Recent developments and trends in thermal blanching--A comprehensive review,” Inf. Process. Agric., vol. 4, no. 2, pp. 101–127, 2017. [CrossRef]

- ICMR-NiN, “Short Report of Nutritional requiremnets of Indians-RDA and Estimated Average Requirements-ICMR-NiN.” Feb. 2020.

- S. Chandra, S. Singh, and D. Kumari, “Evaluation of functional properties of composite flours and sensorial attributes of composite flour biscuits,” J. Food Sci. Technol., vol. 52, no. 6, pp. 3681–3688, 2015. [CrossRef]

- [28] Ghosh Paulami, and Shuchi Upadhyay. "Food Waste Management and Nutrient Recycling in a Sustainable Way—A Review." In International Conference on Advances and Innovations in Recycling Engineering, Springer Nature pp. 157-164,2021.

- Z. H. Al-Attabi, T. M. Merghani, A. Ali, and M. S. Rahman, “Effect of barley flour addition on the physico-chemical properties of dough and structure of bread,” J. Cereal Sci., vol. 75, pp. 61–68, 2017. [CrossRef]

- D. Živančev, A. Torbica, J. Tomić, and E. Janić-Hajnal, “Possibility of utilization alternative cereals (millet and barley) for improvement technological properties of bread gained from flour of poor technological quality,” J. Process. Energy Agric., vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 165–169, 2016.

- A. A. of Cereal Chemists. Approved Methods Committee, Approved methods of the American association of cereal chemists, vol. 1. Amer Assn of Cereal Chemists, 2000.

- A. Rekowski, G. Langenkämper, M. Dier, M. A. Wimmer, K. A. Scherf, and C. Zörb, “Determination of soluble wheat protein fractions using the Bradford assay,” Cereal Chem., 2021.

- M. L. Sudha, V. Baskaran, and K. Leelavathi, “Apple pomace as a source of dietary fiber and polyphenols and its effect on the rheological characteristics and cake making,” Food Chem., vol. 104, no. 2, pp. 686–692, 2007. [CrossRef]

- D. Kohli, A. Kumar, S. Kumar, and S. Upadhyay, “Waste Utilization of Amla Pomace and Germinated Finger Millets for Value Addition of Biscuits,” Curr. Res. Nutr. Food Sci. J., vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 272–279, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Mecozzi, “Estimation of total carbohydrate amount in environmental samples by the phenol--sulphuric acid method assisted by multivariate calibration,” Chemom. Intell. Lab. Syst., vol. 79, no. 1–2, pp. 84–90, 2005. [CrossRef]

- P. Chandra, I. S. Singh, and S. B. Singh, “Biochemical changes during flowering of sugarcane,” Sugar Tech, vol. 7, no. 4, pp. 160–162, 2005. [CrossRef]

- S. Y. Giami, “Comparison of bread making properties of composite flour from kernels of roasted and boiled African bread fruit (Treculia Africana decne) seeds,” J. Mat. Res., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 16–25, 2004.

- P. Y. Lim, Y. Y. Sim, and K. L. Nyam, “Influence of kenaf (Hibiscus cannabinus L.) leaves powder on the physico-chemical, antioxidant and sensorial properties of wheat bread,” J. Food Meas. Charact., vol. 14, pp. 2425–2432, 2020. [CrossRef]

- S. S. Arya and N. K. Shakya, “High fiber, low glycaemic index (GI) prebiotic multigrain functional beverage from barnyard, foxtail and kodo millet,” Lwt, vol. 135, no. August 2020, p. 109991, 2021. [CrossRef]

- R. S. 2000, Handbook of Analysis and Quality Control for Fruits and Vegetables Products. Tata Me Graw-Hill. 2000.

- M. Usman et al., “Effect of apple pomace on nutrition, rheology of dough and cookies quality,” J. Food Sci. Technol., pp. 1–8, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Nasir, M. S. Butt, F. M. Anjum, K. Sharif, and R. Minhas, “Effect of moisture on the shelf life of wheat flour,” Int. J. Agric. Biol, vol. 5, no. 4, pp. 458–459, 2003.

- C. R. Daubert and E. A. Foegeding, “Rheological principles for food analysis,” in Food analysis, Springer, 2010, pp. 541–554. [CrossRef]

- Z. Wang, Y. Li, and et al. Yang, “New insight into the function of wheat glutenin proteins as investigated with two series of genetic mutants,” Sci. Rep., vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 1–14, 2017. [CrossRef]

- S. C. Ubbor, E. N. T. Akobundu, and others, “Quality characteristics of cookies from composite flours of watermelon seed, cassava and wheat,” Pakistan J. Nutr., vol. 8, no. 7, pp. 1097–1102, 2009.

- P. Udomkun et al., “Promoting the use of locally produced crops in making cereal-legume-based composite flours: An assessment of nutrient, antinutrient, mineral molar ratios, and aflatoxin content,” Food Chem., vol. 286, pp. 651–658, 2019.. [CrossRef]

- G. O. Phillips and P. A. Williams, Handbook of hydrocolloids. Elsevier, 2009.

- M. Swieca, L. Skeczyk, U. Gawlik-Dziki, and D. Dziki, “Bread enriched with quinoa leaves-the influence of protein-phenolics interactions on the nutritional and antioxidant quality.,” Food Chem., vol. 162, pp. 54–62, 2014. [CrossRef]

- S. Kumar et al., “Numerical optimization of microwave treatment and impact of storage period on bioactive components of cumin, black pepper and mustard oil incorporated coriander leave paste,” J. Food Meas. Charact., vol. 16, no. 3, pp. 2071–2085, 2022. [CrossRef]

- S. Kumar et al., “Physicochemical properties, nutritional and sensory quality of low-fat Ashwagandha and Giloy-fortified sponge cakes during storage,” J. Food Process. Preserv., vol. 46, no. 2, pp. 1–14, 2022. [CrossRef]

| Flour Mix |

Apple pomace pow- der |

Indian gooseberry pomace powder | Potato peel powder | Bottle gourd peel powder | Whole wheat flour |

| PPWF1 | 10% | 5% | 5% | 4% | 76% |

| PPWF2 | 15% | 10% | 10% | 8% | 57% |

| PPWF3 | 20% | 15% | 15% | 12% | 38% |

| PPWF4 | 25% | 20% | 20% | 16% | 19% |

| Ingredients | G1 (20-80%) | G2 (30-70%) | Control 100% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Refined wheat flour | 80 g | 70 g | 100 g |

| PPWF3 | 20 g | 30 g | 0 g |

| Lukewarm Water (43°C) | 60 ml | 60 ml | 60 ml |

| Salt | 2 g | 2 g | 2 g |

| Baker’s yeast | 6 g | 6 g | 6 g |

| Sugar | 4 g | 4 g | 4 g |

| SoybeanCookingOil | 2 mL | 2 mL | 2 mL |

| Attributes | Apple Pomace Powder |

Indian gooseberry Pomace Powder | Potato Peels Powder |

Bottle Gourd Peels powders | Whole Wheat Flour |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture(%) | 5.5 ± 0.28 | 9.31 ± 0.16 | 11.44 ± 0.04 | 9.40 ± 0.04 | 12.3 ± 0.28 |

| Ash (%) | 1.89 ± 0.10 | 0.86 ± 0.09 | 2.92 ± 0.04 | 3.92 ± 0.01 | 1.5 ± 0.07 |

| Fat(%) | 4.15 ± 0.19 | 6.14 ± 0.20 | 2.42 ± 0.03 | 2.43 ± 0.12 | 1.7 ± 0.36 |

| Fiber (%) | 10.15 ± 1.19 | 13.15 ± 0.29 | 8.15 ± 0.22 | 7.24± 0.13 | 0.3 ± 0.11 |

| Pectin (%) | 10.2 ± 0.21 | 4.27 ± 0.28 | 0.64 ± 0.42 | 1.17 ± 0.21 | Non Detectable |

| Vitamin C (mg/g) |

10.54 ± 0.17 | 272.71 ± 0.06 | 2.14 ± 0.07 | 13.53 ± 0.05 | 1.48 ± 0.06 |

| Protein(%) | 1.53 ± 0.05 | 1.77 ± 0.11 | 2.17 ± 0.07 | 2.74 ± 0.07 | 11.79 ± 0.10 |

| WAC(%) a | 418.66 ± 3.53 | 831 ± 33.94 | 367.33 ± 8.48 | 316 ± 12.72 | 129 ± 16.26 |

| OAC(%) b | 132 ± 5.65 | 454 ± 5.65 | 168.66 ± 13.43 |

152 ± 10.60 | 169 ± 16.97 |

| TPC (mg/GAE/g)c |

10.447 ± 0.06 | 45.754 ± 0.08 | 2.144 ± 0.03 | 6.467 ± 0.03 | 2.23 ± 0.05 |

| TS(mg/g) d | 121.35 ± 0.12 | 72.54 ± 0.20 | 41.40 ± 0.24 | 95.33 ± 0.18 | 25.14 ± 0.10 |

| RS(mg/g) e | 16.19 ± 0.30 | 34.71 ± 0.32 | 23.69 ± 0.06 | 3.37 ± 0.12 | 11.41 ± 0.13 |

| NRS (mg/g) f | 99.79 ± 0.16 | 35.75 ± 0.05 | 17.08 ± 0.002 | 87.33 ± 0.08 | 13 ± 0.02 |

| Parameters | PPWF1 | PPWF2 | PPWF3 | PPWF4 | Control |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture (%) | 12.246 ± 0.30 | 9.5 ± 0.28 | 9.5 ± 0.07 a | 9.38 ± 0.37 | 12.2 ± 0.28 b |

| Ash (%) | 3.30 ± 0.23 | 3.5 ± 0.28 | 2.58 ± 0.23 a | 4.67 ± 0.14 | 0.50 ± 0.07 a |

| Fat (%) | 1.5 ± 0.28 | 5.17 ± 0.05 | 3.3 ± 0.28 a | 3.15 ± 0.03 | 1.74 ± 0.36 a |

| Fiber (%) | 6.26 ± 0.11 | 7.28 ± 0.01 | 8.16 ± 0.17 a | 8.28 ± 0.01 | 3.16 ± 0.11 b |

| Protein (%) | 2.57 ± 0.14 | 2.82 ± 0.04 | 3.18 ± 0.06a | 3.16 ± 0.09 | 10.79 ± 0.10b |

|

Vitamin C (mg/100g) |

7.16 ± 0.11 | 8.28 ± 0.01 | 13.64 ± 0.09 a | 4.4 ± 0.49 | 1.48 ± 0.06 b |

| WAC (%) | 424.66 ± 2.12 | 424.4 ± 13.43 | 431.4± 25.45a | 460.4 ± 8.48 | 129.4 ± 16.26a |

| OAC (%) | 255.66 ± 8.48 | 231.66 ± 24.78 |

253 ± 2.82 a | 235.66 ± 13.43 |

169 ± 16.97a |

|

TPC (mg/GAE/g) |

13.34 ± 0.06 | 11.89 ± 0.08 | 14.48 ± 0.11 a | 13.27 ± 0.09 | 2.23 ± 0.05 b |

| TS (mg/g) | 93.56 ± 0.31 | 105.67 ± 0.26 | 78.66 ± 0.29 a | 59.31 ± 0.12 | 25.14 ± 0.10 b |

| RS (mg/g) | 47.48 ± 0.03 | 66.54 ± 0.10 | 38.05 ± 3.26a | 41.55 ± 0.15 | 11.41 ± 0.13 b |

| NRS (mg/g) | 43.77 ± 0.33 | 37.17 ± 0.35 | 41.14 ± 0.55a | 16.87 ± 0.03 | 13 ± 0.02 b |

| Parameters | 100% | G1(20-80) % | G2(30-70) % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Moisture Content (%) | 20.31 ± 0.40 a | 30.5 ± 0.28b | 27.9 ± 0.09b |

| Ash Content (%) | 4.7 ± 0.25 a | 4.8 ± 0.11 a | 5.4 ± 0.01 b |

| Fat (%) | 3.44 ± 0.28a | 3.26 ± 0.14 a | 8.24 ± 0.35 b |

| Protein (%) | 2.3 ± 0.19 a | 2.42 ± 0.05 a | 2.44 ± 0.42a |

| Fibre (%) | 2.57 ± 0.06 a | 5.1 ± 0.35 b | 4.95 ± 0.14 b |

| Carbohydrates (%) | 65.41 ± 0.26 a | 54.32 ± 0.57b | 70.36 ± 0.15 ab |

| Energy (Kcal/100 gm) | 303.04 ± 0.04 a | 255.2 ± 0.21b | 365.46 ± 0.52 ab |

| Vitamin C (mg/100g) | 2.18 ± 0.07 a | 2.11 ± 0.01a | 2.75 ± 0.008 b |

| TPC (mg/GAE/g) | 7.46 ± 0.08 a | 9.58 ± 0.06 b | 9.26 ± 0.10 b |

| TS (mg/g) | 121 ± 0.14 a | 72 ± 60 b | 48.5 ± 0.05 ab |

| RS (mg/g) | 28.41 ± 0.15a | 22.35 ± 0.13 b | 34.6 ± 0.32 ab |

| NRS (mg/g) | 88.26 ± 0.28 a | 47.74 ± 0.01b | 13.20 ± 0.25 ab |

| Attributes | Apple Pomace Powder |

Amla Pomace Powder |

Potato Peels Powder | Bottle Gourd Peels |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Swelling capacity(mL) | 17.60±1.85 | 15.40±1.85 | 19.00±0.71 | 17.40±1.85 |

| Emulsion capacity (%) | 36.33±3.05 | 38.4±3.22 | 41.66±3.77 | 43.88±4.12 |

| Foaming capacity (%) | 16.9±4.00 | 17.2±5.3 | 15.22±4.04 | 17.33±3.23 |

| Parameters | 100% | G1(20-80)% | G2(30-70)% |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loaf weight (g) | 93.8 ± 1.68 a | 96.2 ± 3.7a | 96.17 ± 0.88 a |

| Loaf Volume (cm3) | 349 ± 2.6 a | 302 ± 24.1 a | 247 ± 12.4 b |

| Specific Volume (cm3/g) | 3.68 ± 0.07a | 3.60 ± 0.07 a | 3.96 ± 0.06 b |

|

Colour L* |

74.9 ± 0.08 a | 55.7 ± 1.6 b | 42.9 ± 1.25 c |

| a* | 1.59 ± 0.17 b | 2.39 ± 0.70b | 3.84 ± 0.46 a |

| b* | 21.6 ± 0.17 b | 36.0 ± 2.98a | 37.0 ± 1.97 a |

| Hardness | 317 ± 62.6 c | 421 ± 71.2a | 464 ± 76.4 b |

| Cohesiveness | 0.89 ± 0.04 a | 0.84 ± 0.02 a | 0.82 ± 0.01 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).