Submitted:

16 August 2023

Posted:

17 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Heat-escape Market Demand and Supply

2.1. Market demand characteristics

- 1)

- Tourism Willingness. Recently, there has been a surge in people’s willingness to travel, and summer tourism to escape the heat has become increasingly popular. A comparison of the 2023 China Summer Tourism Development Report and 2018 China Heat-Escape Tourism Big Data Report found that the overall willingness of residents to travel in the third quarter increased from 80% in 2018 to 94.6% in 2023, with a high willingness to travel and a further increase in demand in the heat-escape tourism market.Baidu index big data platform shows that the search popularity with summer tourism as the key word is rising this year.

- 2)

- Travel Groups. The three main market groups of heat-escape tourism (the elderly, students and teachers, and urban residents of high-temperature cities) represent about 300 million people with high potential effective demand for heat-escape tourism. Due to the institutional arrangement of winter and summer vacations and the natural, seasonal rhythms, students and teachers become the main force of heat-escape tourism. With the change in the concept of the elderly and the strong national social security system, the number of the elderly who have money and time and are willing to travel is increasing. What’s more, summer brings a high incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in the elderly, and heat-escape is especially important for them. Residents in traditional high-temperature areas also have a strong demand for heat escape, with a potential market size of more than 100 million people.

- 3)

- Short-range Orientation for Travel Groups. The cities most favored for heat-escape tourism tend to focus on first-tier cities and second-and third-tier high-temperature cities. However, in some cities, the main tourists come mainly from within and around the province, traveling short and medium distances. Provinces and cities with relatively developed economies and hot temperatures have relatively few local summer resources, and tourists prefer to go to cooler provinces, mainly long distances away, such as the Yangtze River Delta, the Beijing–Tianjin–Hebei region, the Pearl River Delta region, and the central and western “stove” cities. In addition, consumers in high-temperature cities create an obvious demand for heat-escape travel. Chongqing, Chengdu, and Hangzhou are the main sources of heat-escape tourists. However, some large provinces have rich heat-escape tourism resources, such as Heilongjiang, which is rich in forest, wetland, and lake resources. Yunnan, which has a spring-like temperature year-round, and Shandong, which has more developed coastal resources. Their main tourists are from within and around the province, mainly traveling short and medium distances, with a short-range orientation.

- 4)

- Resource Orientation for Travel Groups. The short-range orientation of travel groups refers to when tourists’ demand for heat-escape tourism is met by tourism products in nearby regions. Such resources supporting these tourism products are widely distributed and dispersed. Pleasant climate in China illustrates a geographical pattern, and most regions in Northwest and Northeast China, as well as North and Southwest China, have favorable heat-escape climate conditions. Tourists also tend to choose these regions as heat-escape destinations. Even in the traditional high-temperature areas, such as the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze River, there are abundant heat-escape climate resources, such as Lushan Mountain in Jiangxi, Mogan Mountain in Zhejiang, and Tiantangzhai in Anhui. The three core destination regions support the main market for heat-escape tourism in China: the wetland and forest resources in Northeast China, the coastal resources around the Bohai Sea, and the small town and lake resources in Yunnan.

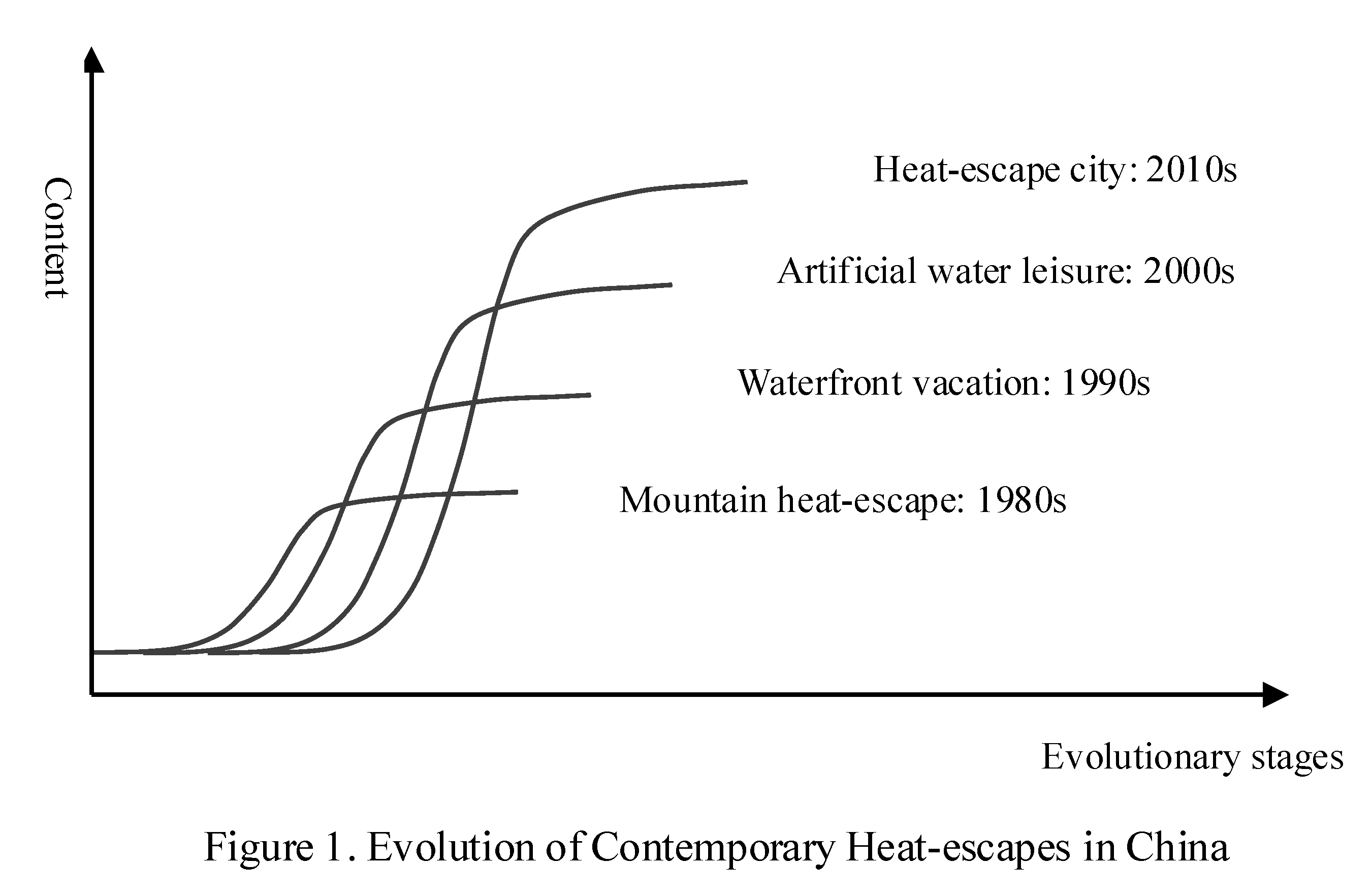

2.2. The Evolution of Heat-escape Tourism Supply

3. Mapping summer tourism climate resources in China

3.1. Data Sources and Methods

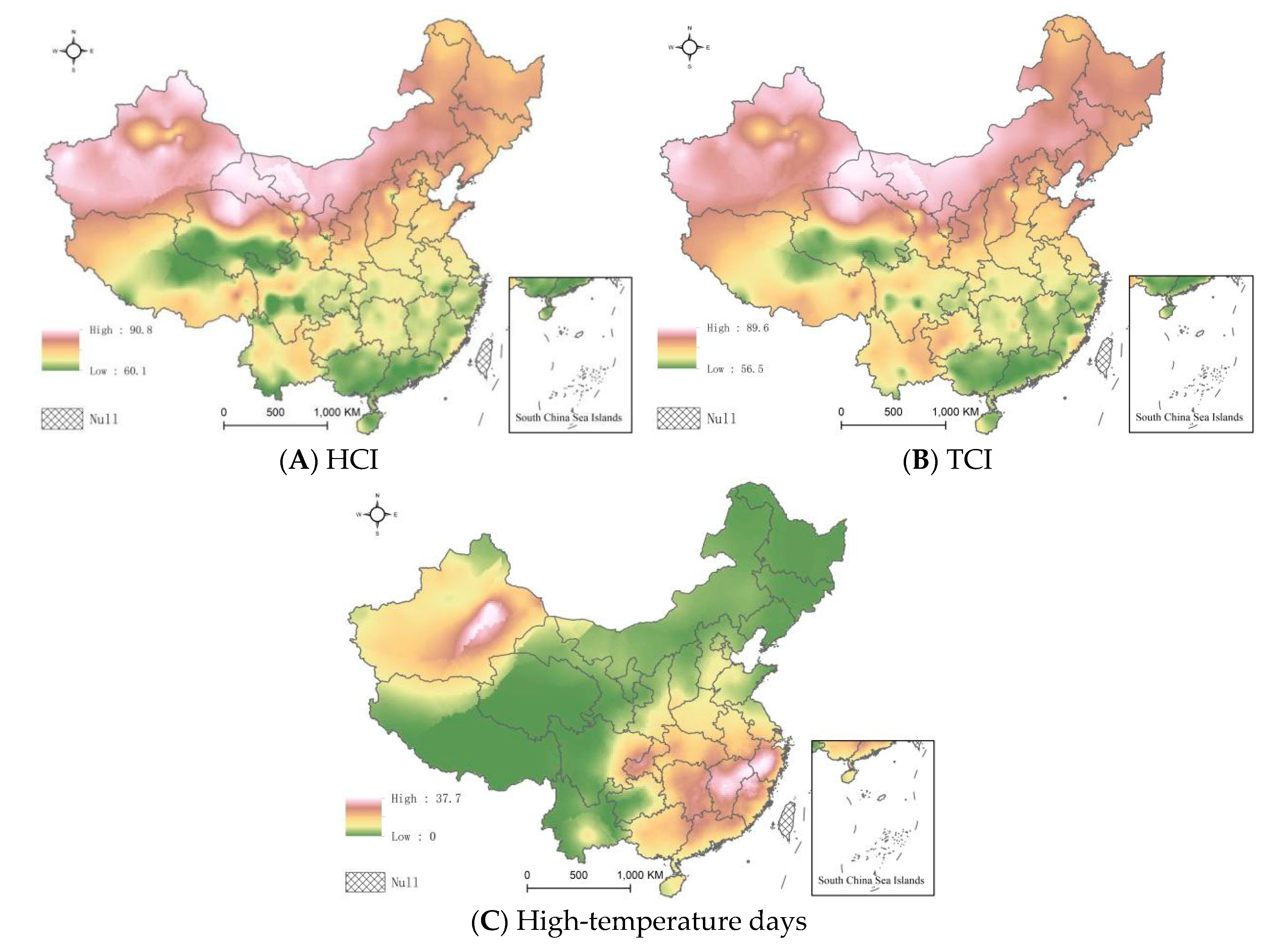

3.2. Spatial pattern

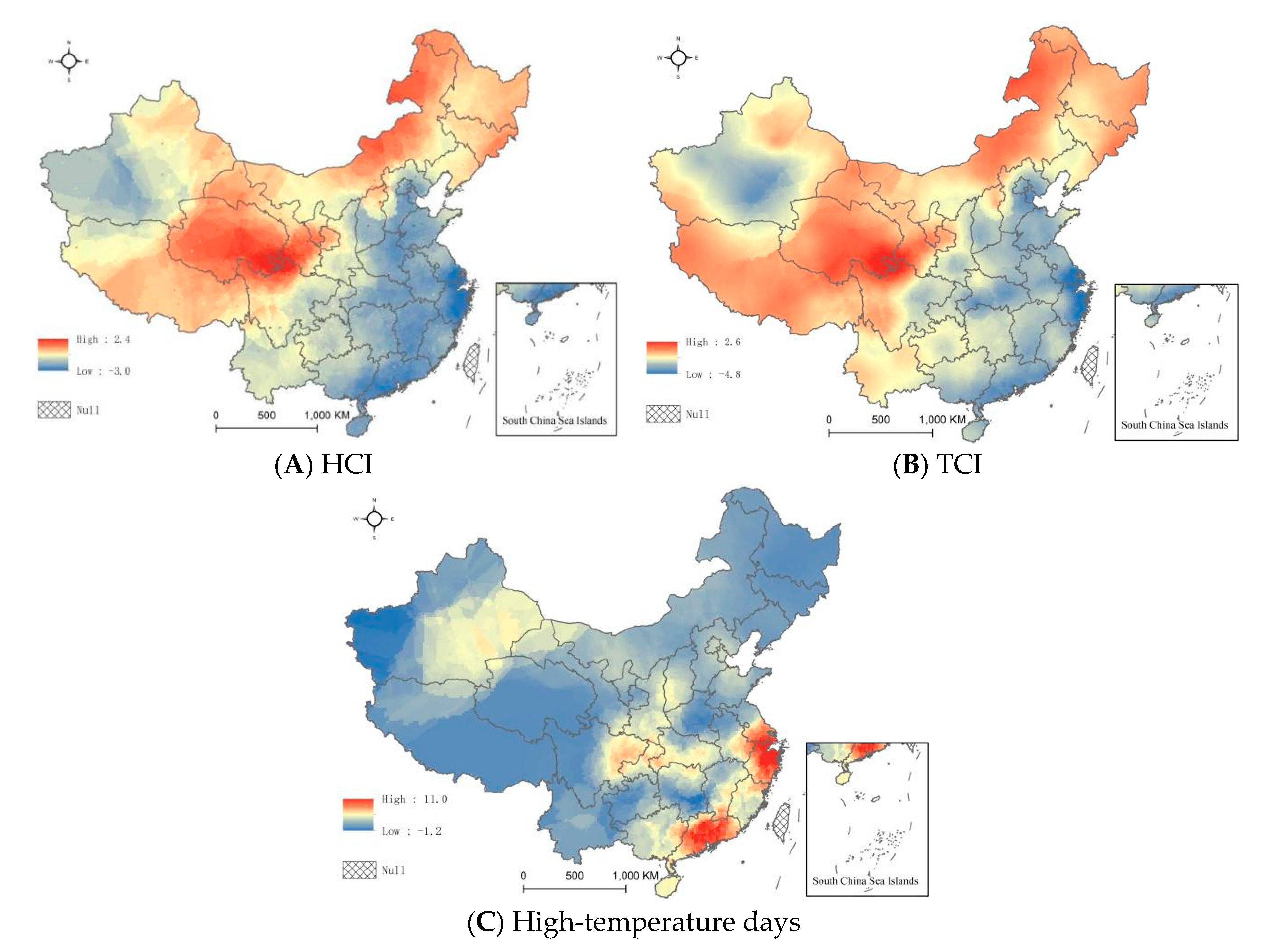

3.3. Evolution trend

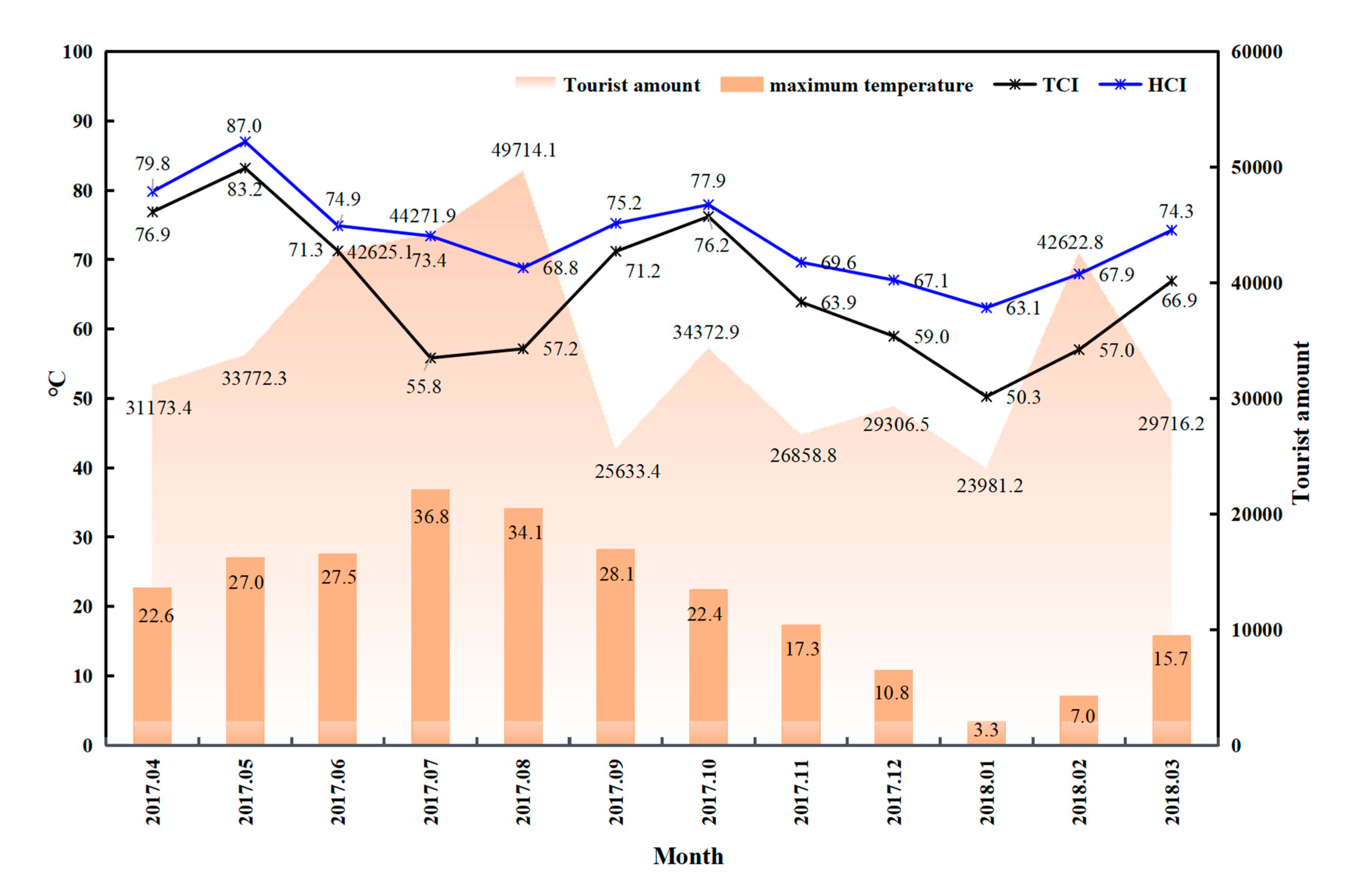

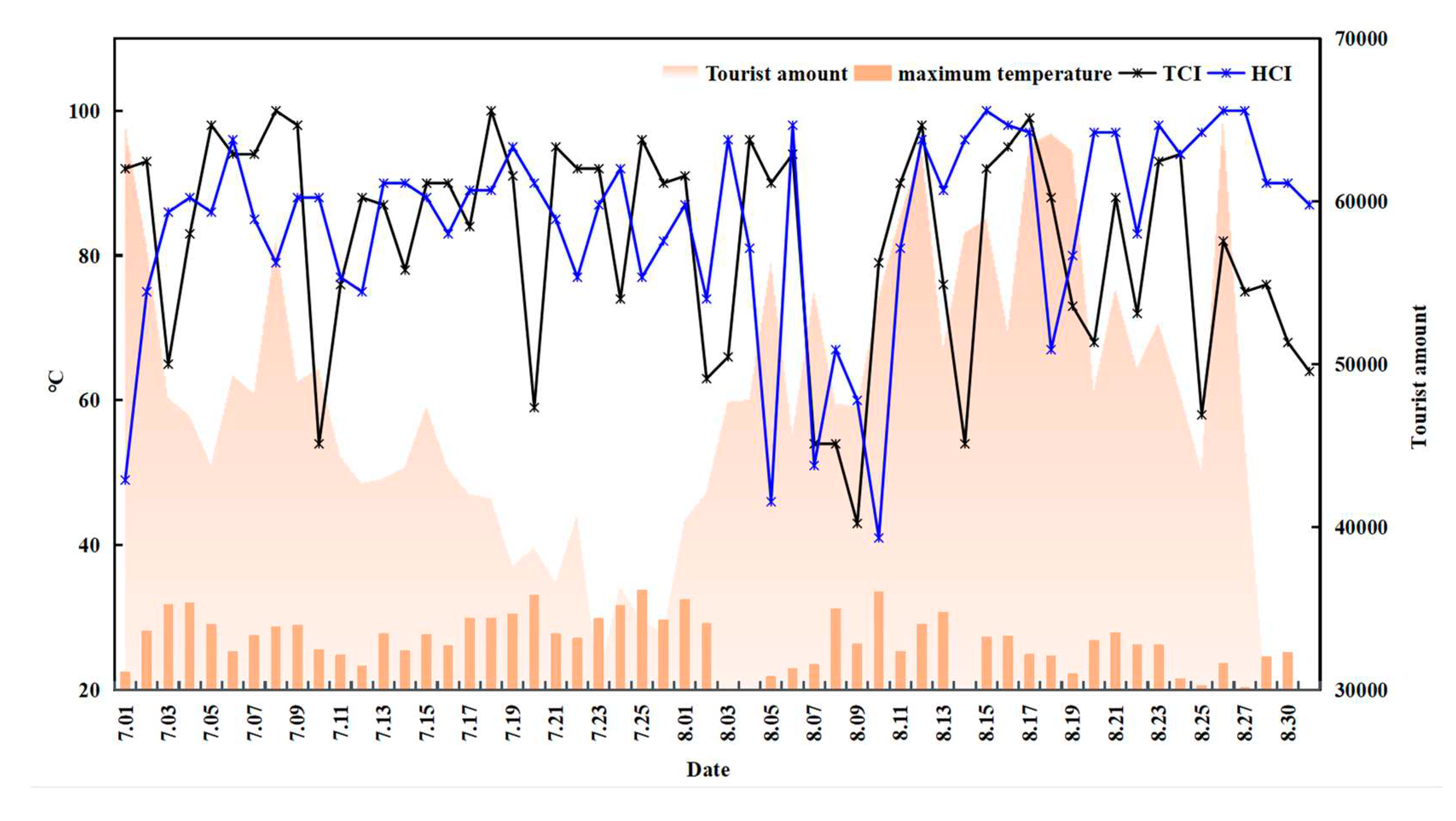

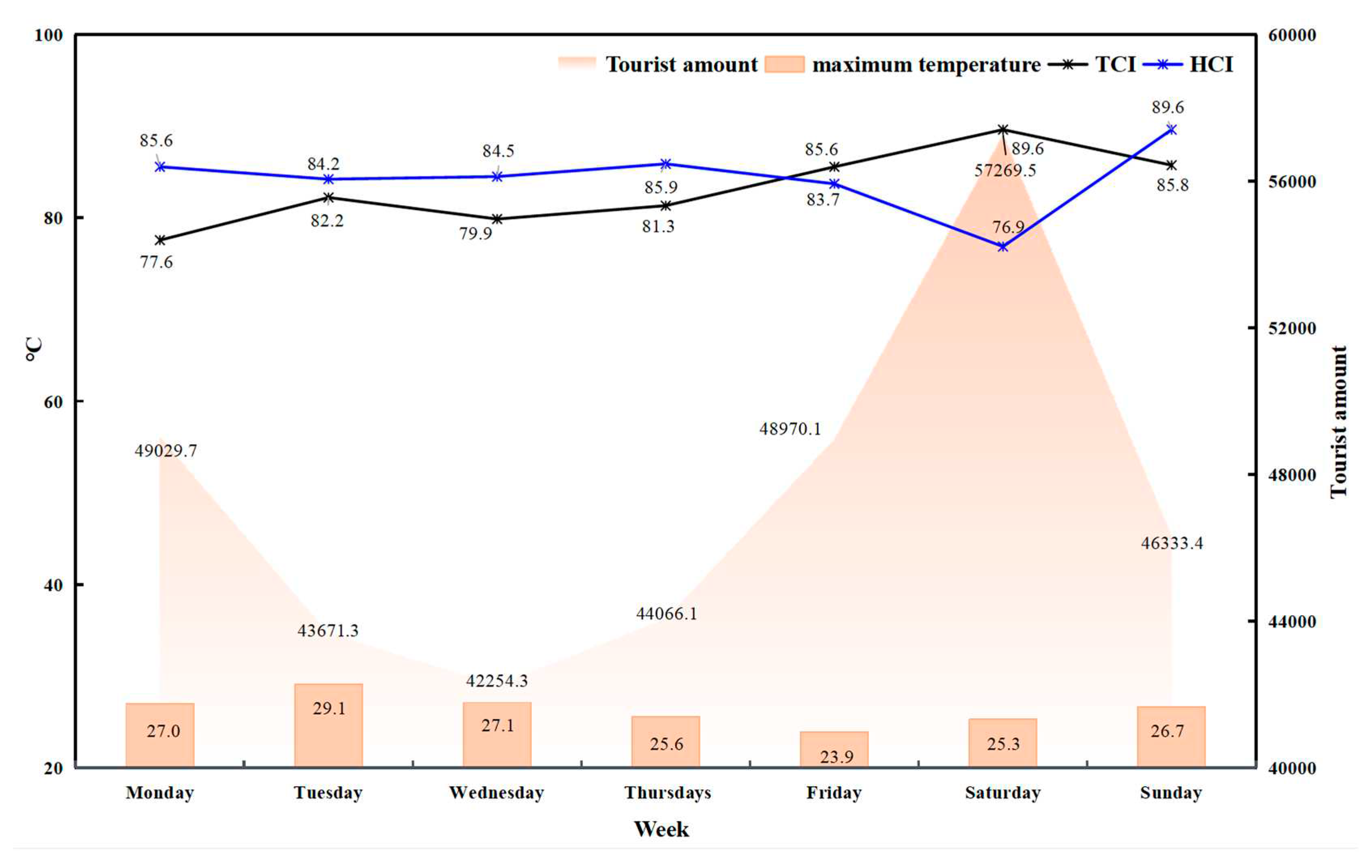

4. Case Study: High-temperature Response of Shanghai Disney Market

5. Discussion and Conclusion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cai, W.; Yang, K.; Wu, L.; etc. Opposite response of strong and moderate positive Indian Ocean Dipole to global warming. Nature Climate Change 2021, 11, 27–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trisos, C. H.; Merow, C.; Pigot, A. L. The projected timing of abrupt ecological disruption from climate change. Nature 2020, 580, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X.; Yuan, C.; Yang, M.; etc. Prediction of summer extreme hot days in China using the SINTEX-F2. International Journal of Climatology 2021, 41, 4966–4976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Cui, L.; Ma, Y.; etc. Trends in temperature extremes and their association with circulation patterns in China during 1961–2015. Atmospheric Research 2018, 212, 259–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becken, S.; Wilson, J. The impacts of weather on tourist travel. Tourism Geographies 2013, 15, 620–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D. J.; Lemieux, C. J.; Malone, L. Climate services to support sustainable tourism and adaptation to climate change. Climate Research 2011, 47, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutty, M.; Scott, D. Comparison of climate preferences for domestic and international beach holidays: A case study of Canadian travelers. Atmosphere 2016, 7, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiger, R.; Posch, E.; Tappeiner, G. ; etc. The impact of climate change on demand of ski tourism—a simulation study based on stated preferences. Ecological Economics. [CrossRef]

- Cocolas, N.; Walters, G.; Ruhanen, L. Behavioural adaptation to climate change among winter alpine tourists: an analysis of tourist motivations and leisure substitutability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2016, 24, 846–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gössling, S.; Scott, D.; Hall, C. M.; etc. Consumer behaviour and demand response of tourists to climate change. In Annals of Tourism Research 2012, 39, 36–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutty, M.; Scott, D.; Matthews, L.; etc. An Inter (HCI:Beach) and the tourism climate index (TCI) to explain Canadian tourism arrivals to the Caribbean. Atmosphere 2020, 11, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H. Q.; Kulendran, N. The Impact of Climate Variables on Seasonal Variation in Hong Kong Inbound Tourism Demand. Journal of Travel Research 2017, 56, 94–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Lau, N. C. Increasing Heat Stress in Urban Areas of Eastern China: Acceleration by Urbanization. Geophysical Research Letters 2018, 45, 13060–13069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abadie, L. M. Sea level damage risk with probabilistic weighting of IPCC scenarios: An application to major coastal cities. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018, 175, 582–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, D. R.; Debbage, K. G. Weather and tourism: Thermal comfort and zoological park visitor attendance. Atmosphere 2016, 7, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Scott, D.; Steiger, R. The impact of climate change on ski resorts in China. International Journal of Biometeorology 2021, 65, 677–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S. J.; Zhou, L. Y. Integrated impacts of climate change on glacier tourism. Advances in Climate Change Research 2019, 10, 71–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, B. Climate change and tourism—Are we forgetting lessons from the past? Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 2017, 32, 108–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, J.; Zhao, M.; Wu, P.; etc. A New Hot Topic for the Research of International Tourism Science: The Impact of Global Climate Change or Tourism Industry. Tourism Tribune 2010, 25, 86–92. [Google Scholar]

- Thurm, B.; Vielle, M.; Frank, V. Impacts of climate change for Swiss winter and summer tourism: a general equilibrium analysis. Proceedings of the EAERE 23rd Annual Conference 2017.

- Coombes, E. G.; Jones, A. P. Assessing the impact of climate change on visitor behaviour and habitat use at the coast: A UK case study. Global Environmental Change 2010, 20, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; McBoyle, G.; Minogue, A.; etc. Climate change and the sustainability of ski-based tourism in eastern North America: A reassessment. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2006, 14, 376–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, D.; Varnajot, A.; Dalen, K.; etc. Cruising the marginal ice zone: climate change and Arctic tourism. Polar Geography 2019, 42, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzinde, C. N.; Manuel-Navarrete, D.; Yoo, E. E. Tourists’ perceptions in a climate of change: Eroding Destinations. Annals of Tourism Research 2010, 37, 333–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enríquez, A. R.; Marcos, M.; Álvarez-Ellacuría, A.; etc. Changes in beach shoreline due to sea level rise and waves under climate change scenarios: Application to the Balearic Islands (western Mediterranean). Natural Hazards and Earth System Sciences 2017, 17, 1075–1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, D.; Scott, N.; Becken, S.; etc. Tourists’ aesthetic assessment of environmental changes, linking conservation planning to sustainable tourism development. Journal of Sustainable Tourism 2019, 27, 1477–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Zhou, Z.; Mu, J. A conceptual model of summer tourism index and construction of evaluation index system. Human Geography 2014, 29, 128–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J. A Research on Development Rules of Tourism Resort. Progress in Geography 2003, 22, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J. Li Jinzao: Speech at the 2018 National Tourism Work Conference (full text). 2018. https://www.sohu.com/a/218861828_825181.

- Mieczkowski, Z. The tourism climate index: a method for evaluating wold climate for tourism. Can. Geogr. 1985, 29, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, D.; Gamal, G.; Seoud, T. A. The potential impact of climate change on Hurghada city, Egypt, using Tourism Climate Index. GeoJournal of Tourism and Geosites 2019, 25, 496–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Yin, J. National assessment of climate resources for tourism seasonality in China using the tourism climate index. Atmosphere 2015, 6, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.; Rutty, M.; Amelung, B.; etc. An inter-comparison of the holiday climate index (HCI) and the tourism climate index (TCI) in Europe. Atmosphere 2016, 7, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).