1. Introduction

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is an autosomal recessive abnormality of the beta-globin chain of hemoglobin (Hgb), resulting in decreased deformability and increased adhesion of the sickle cells causing microvascular occlusion and hemolytic anemia (1). Patients with sickle cell disease are prone to progressive organ damage throughout the body. One of the vital organs that the sickling process can harm is the heart. Cardiovascular complications are becoming more common and are the most common cause of mortality in patients with SCD (2). Pulmonary hypertension left and right ventricular dysfunction, cardiac iron overload, dysrhythmia, myocardial ischemia, and sudden death are all consequences that can be induced by SCD (3).

The prevalence and significance of elevated cardiac markers still need to be well known. We attempted to answer this question by evaluating SCD patients admitted to King Abdulaziz University Hospital (KAUH) within the last five years.

2. Materials and Methods

A retrospective study was conducted in June 2022 to March 2023 at King Abdulaziz University Hospital (KAUH), a tertiary center in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. All patients with SCD patients who were 18 years and above and follow-up in the hematology department were screened. The data collection sheet was used to fill in the information obtained from medical records. It included demographic data, comorbid conditions, hospital admissions, ER visits, cardiac markers; troponin, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), creatine kinase (CK-MB), ECG changes, blood transfusion, and medication.

Microsoft Excel 2021 was used for data entry. All statistical analyses were performed by SPSS version-18.0 software. Frequencies and percentages were generated for nominal and ordinal variables. Spearman's rank correlation was used to detect the association between cardiac markers levels with each of the following (ER visits, age). Furthermore, the rank biserial correlation coefficient linked cardiac markers with ECG, anticoagulant & antiplatelet, hydroxyurea, patient state, and blood transfusion. Statistical significance was set at P values of <0.05 with a 95% confidence interval.

The research ethics committee of KAUH approved this study with reference number (IRB 360-22). The study adhered to appropriate ethics guidelines. Without revealing patient identities, all included patients' medical records were analyzed.

3. Results

A total of 537 patient records were reviewed during the study period, of which 270 patients met the inclusion criteria. Among these, 144 (53.3%) were female. 108 (40%) were aged 21 to 30, and 101 (37.4%) were aged 31 to 40. The most prevalent blood group type was O+ (accounting for 144, or 53.3%). Furthermore, Thalassemia, hypertension, and hepatitis C were the commonest comorbidities in our patients, represented by 78 (29%), 13 (4.8%), and 11 (4%), respectively (

Table 1).

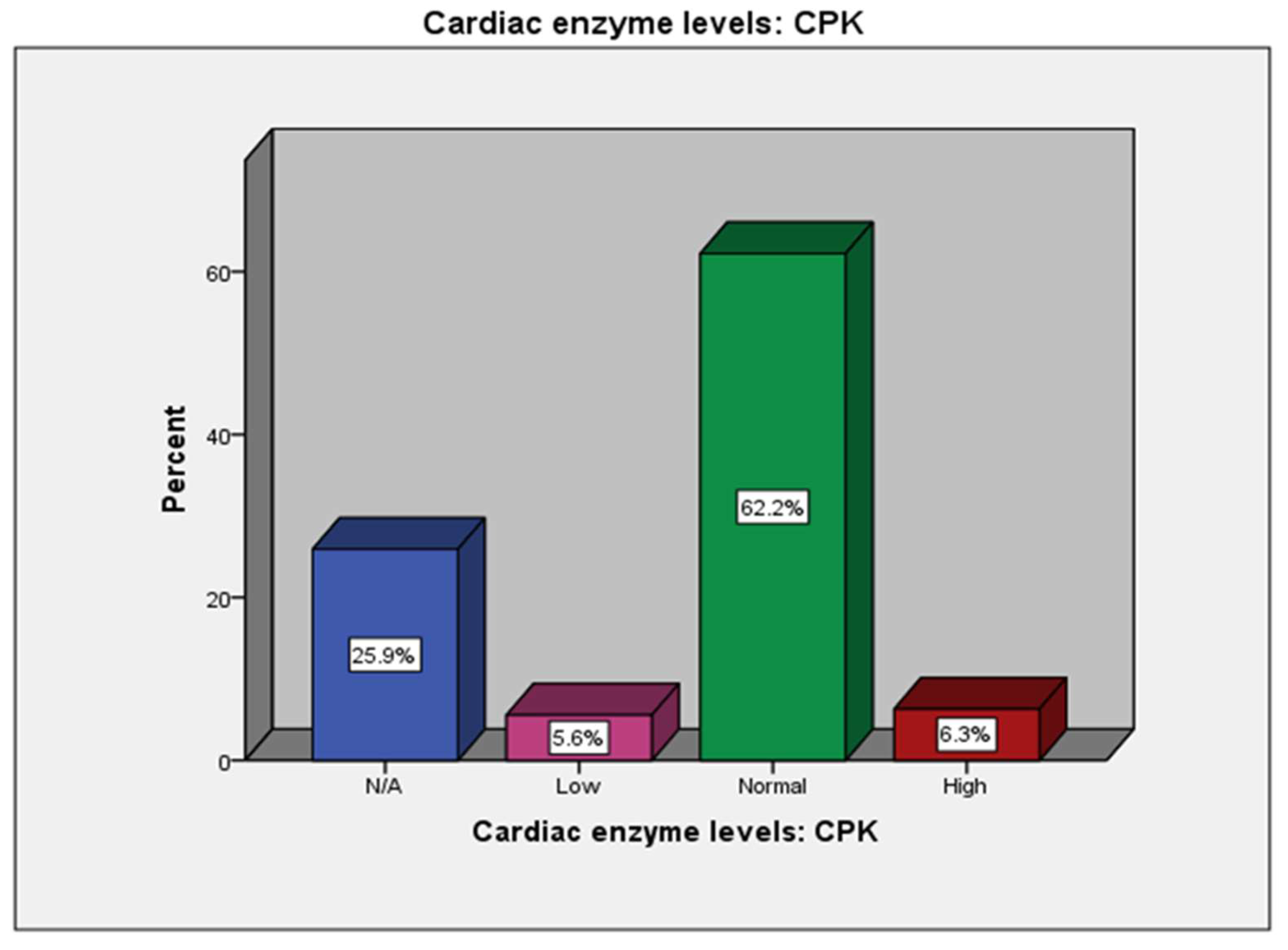

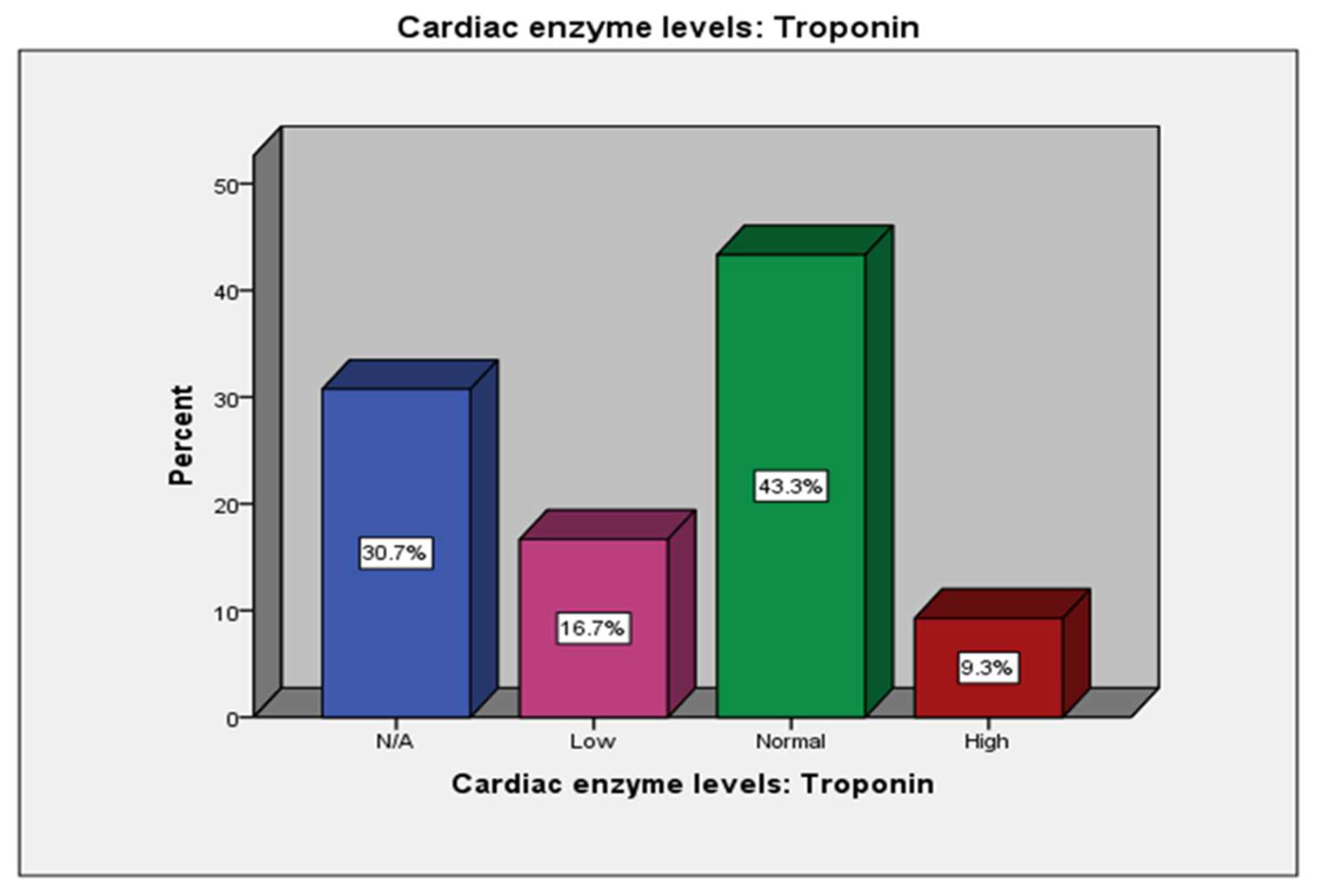

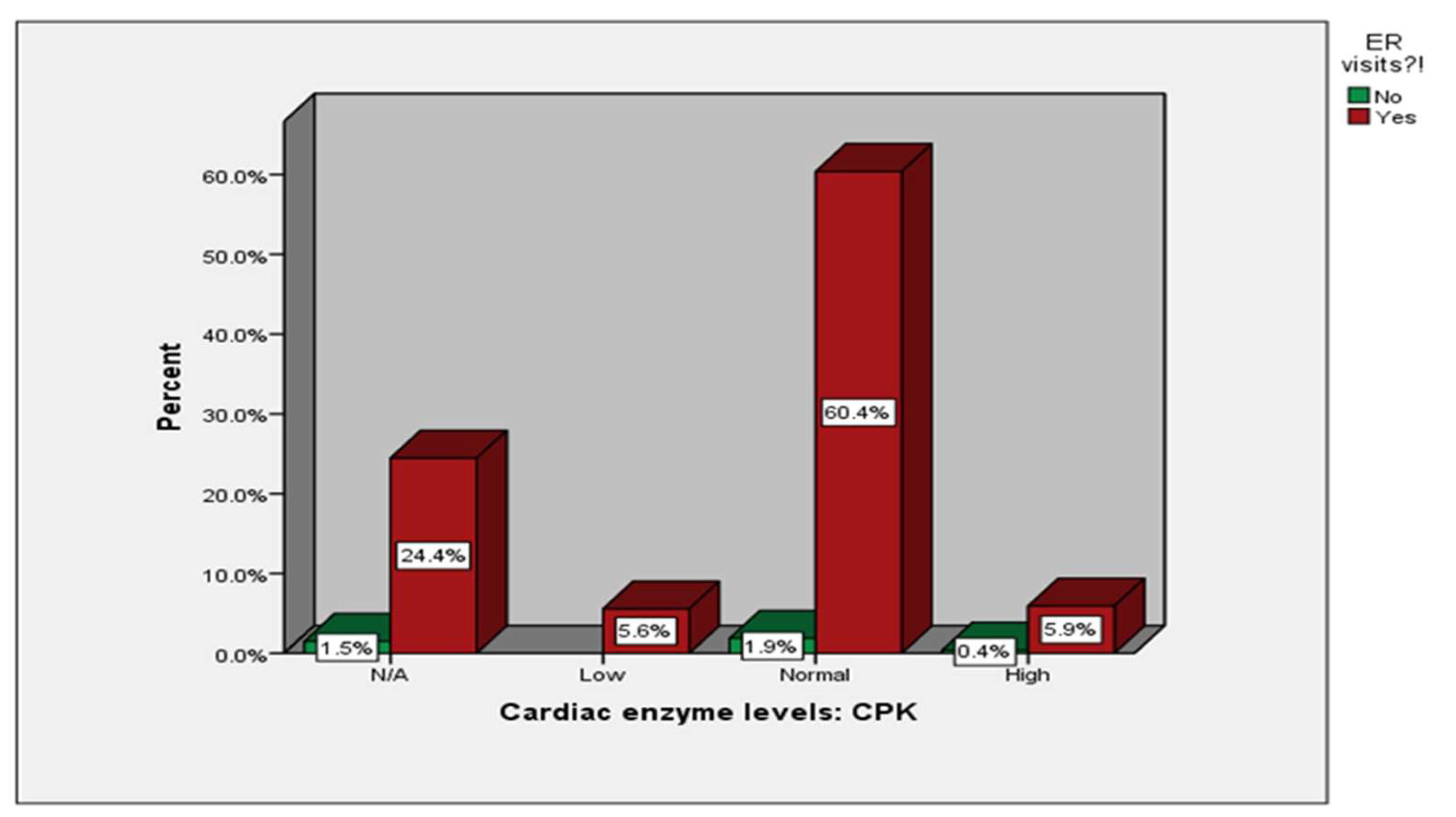

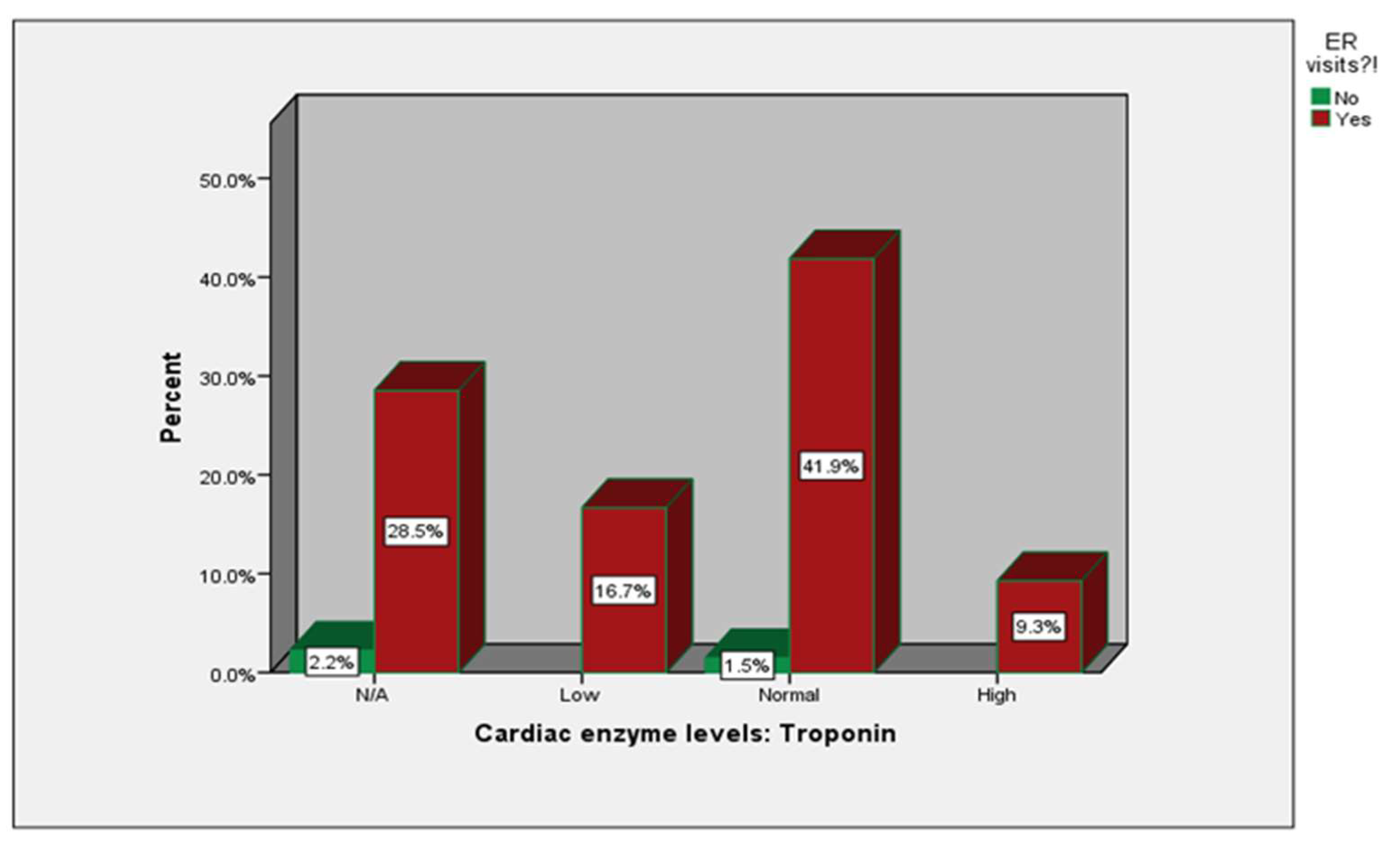

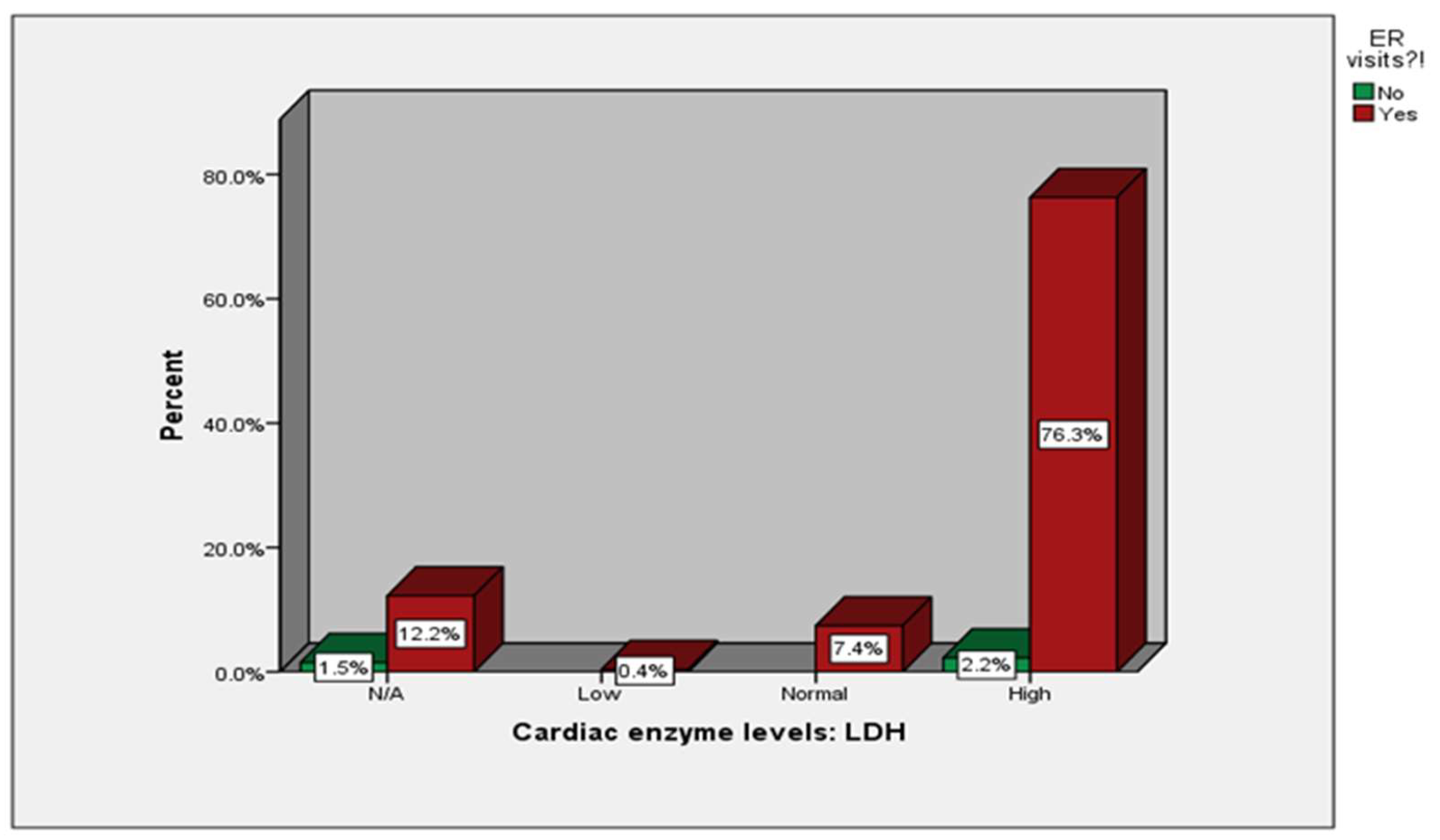

We have shown (

Figure A1) the percentages of patients according to the levels of different cardiac markers (N/A, low, normal, high) and their ER visits. The remaining patients had their tests done during their inpatient or routine outpatient visits.

The relationship between cardiac markers and ER visits was significant (p=0.01). However, the percentages mentioned only demonstrate the different rates of patients depending on their different enzyme levels and whether they visited the ER (

Table 2).

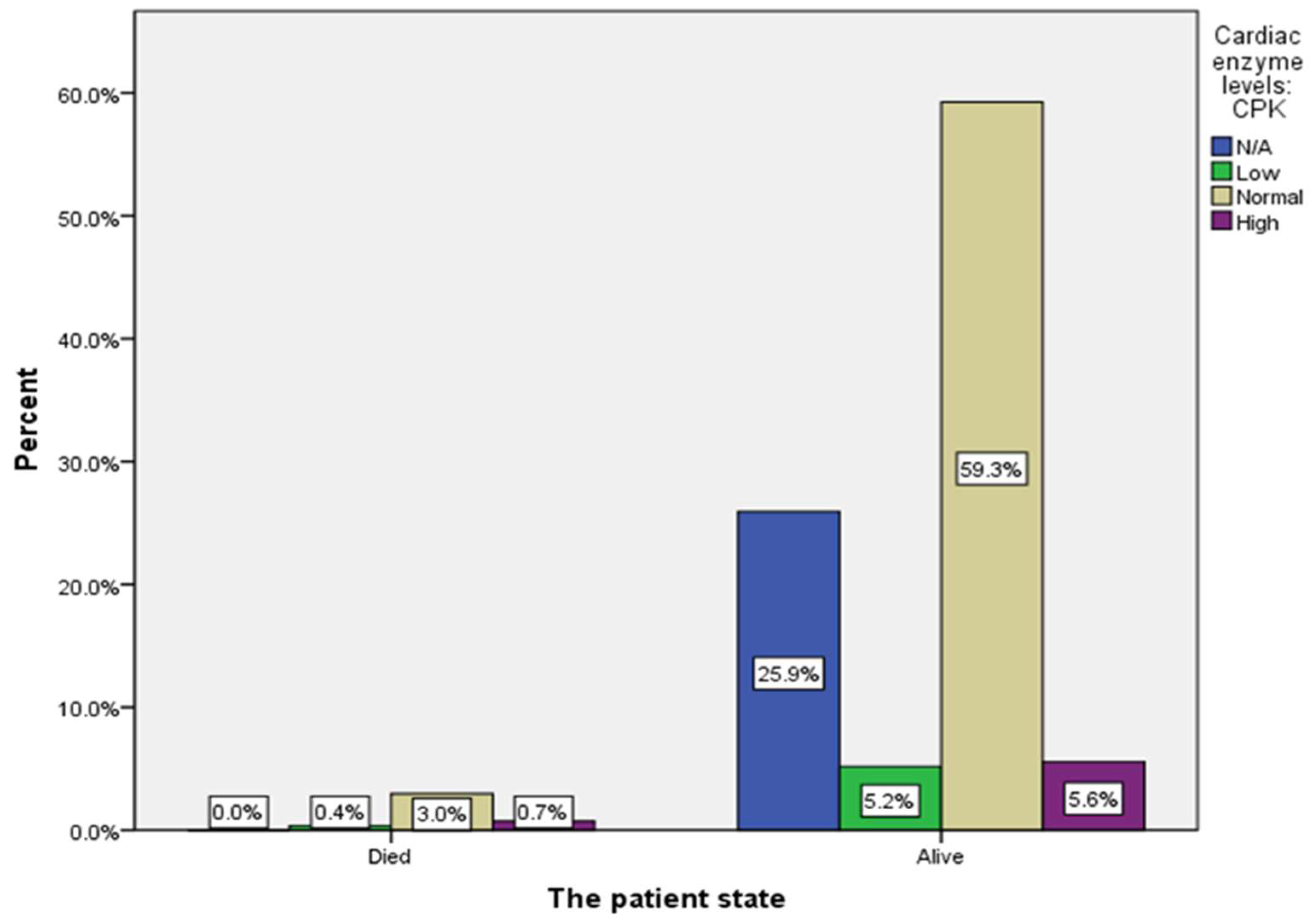

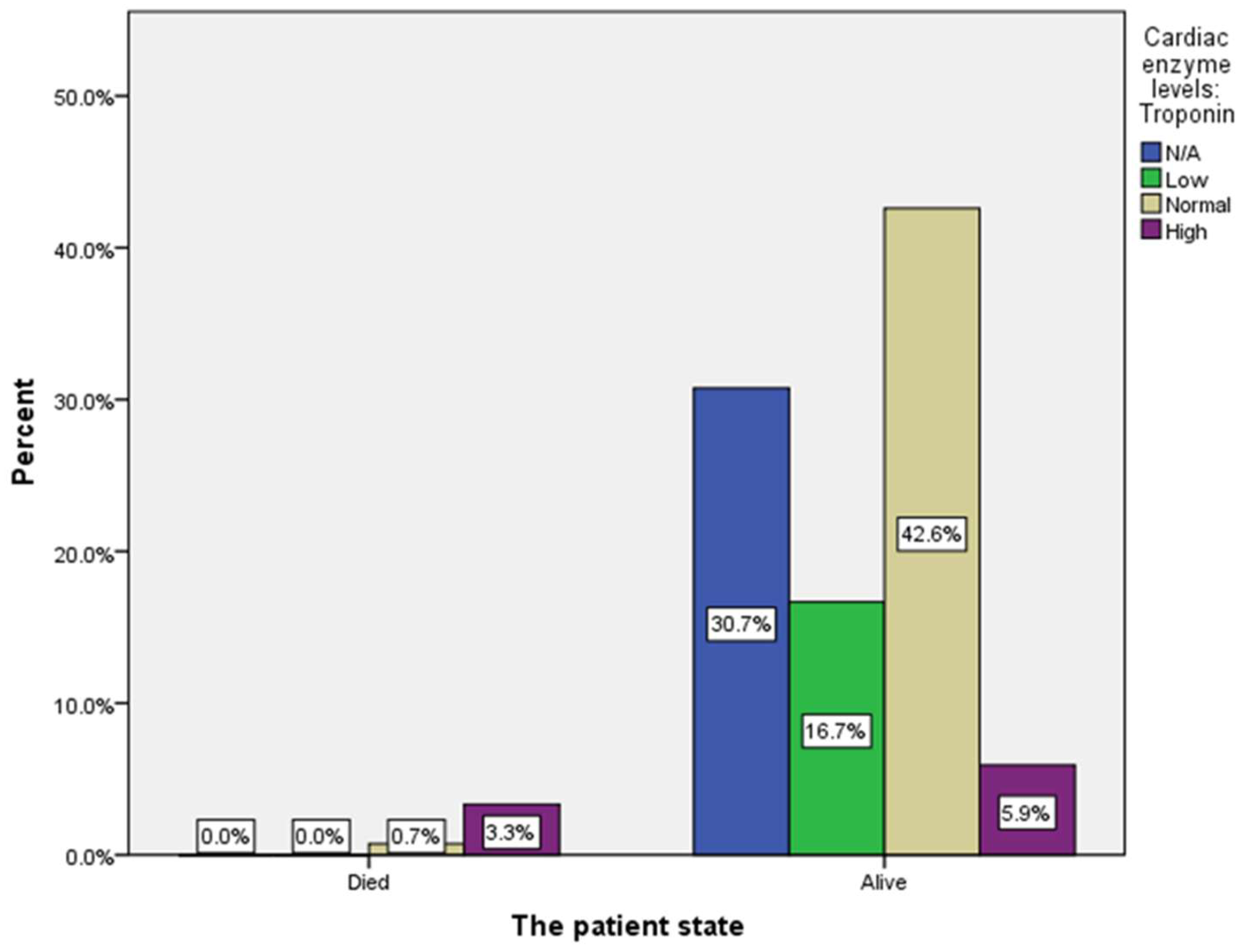

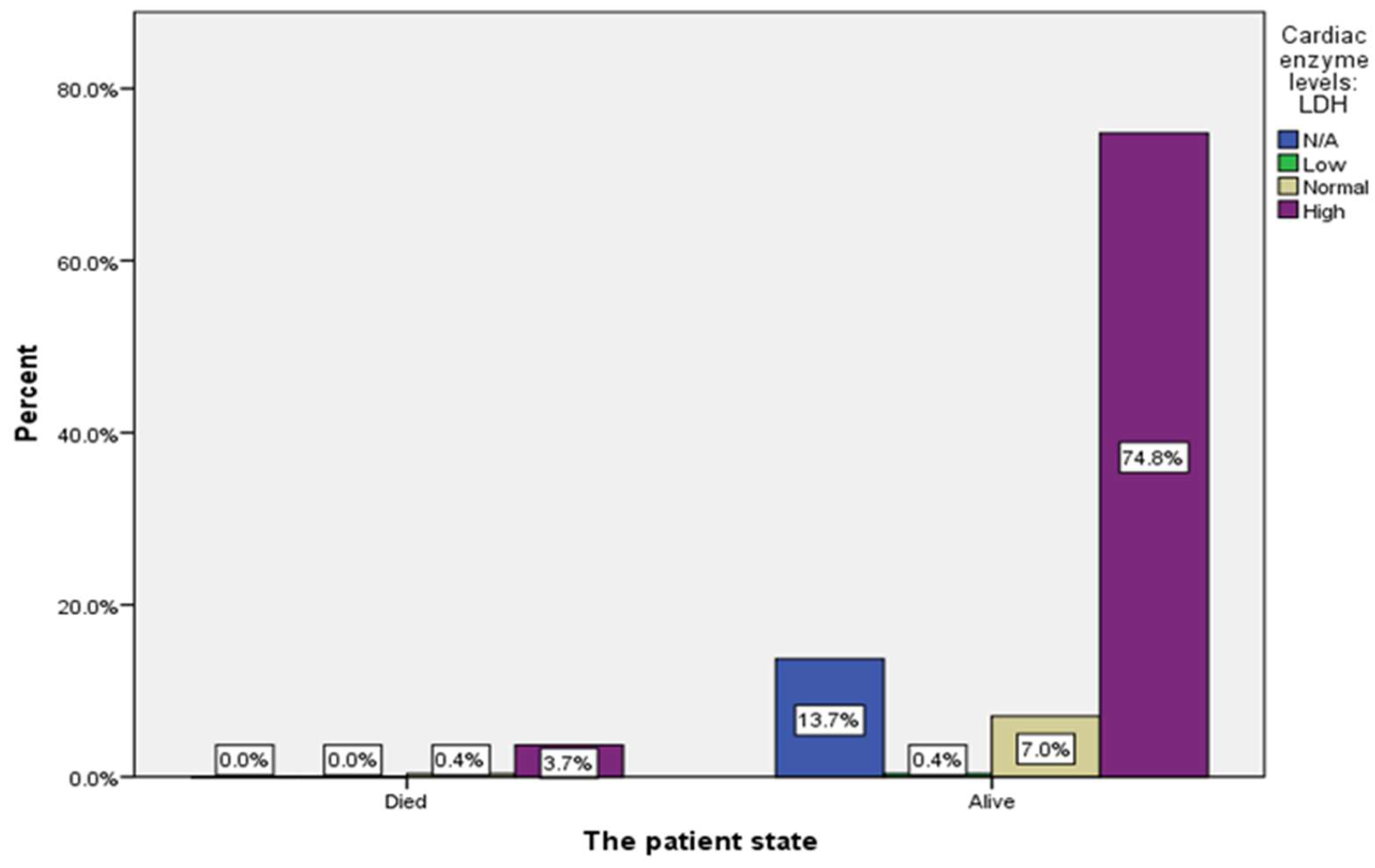

The relationship between CK-MB and LDH enzyme levels, and the patient state showed no significant relationship. However, a highly significant association was found between troponin and the patient state, suggesting that high troponin levels affect patient mortality (

Figure A2).

A descriptive analysis of patients’ findings including ER visits, patient status, the need for blood transfusion, the use of hydroxyurea, ECG findings, the use of anticoagulation, and age groups can be found in (Supplementary

Table 1). There was no significant association found between cardiac markers and the need for blood transfusion, the use of hydroxyurea, ECG findings and the use of anticoagulation (

Table 2).

The need for blood transfusion was either in the form of simple or exchange blood transfusion. In an attempt to analyze each variable on its own, the correlation continued to be insignificant (Supplementary

Table 2)

4. Discussion

Few published papers studied the relationship between elevated cardiac markers and myocardial infarction in patients with SCD in Saudi Arabia. Thus, this retrospective study examines the significance of cardiac markers levels in patients with SCD and their implications for patient outcomes between June 2022 to March 2023

In our study, female patients (53.3%) are slightly more than males (46.7%), similar to regional research in Saudi Arabia, which found that females represent 52.2% (4). Also, another study in New York found that females (54.3%) are more than half of the patients (5). Additionally, we found that 29% of the patients have co-existent Thalassemia disorder in contrast to another study which was only 5% (6) (

Table 1).

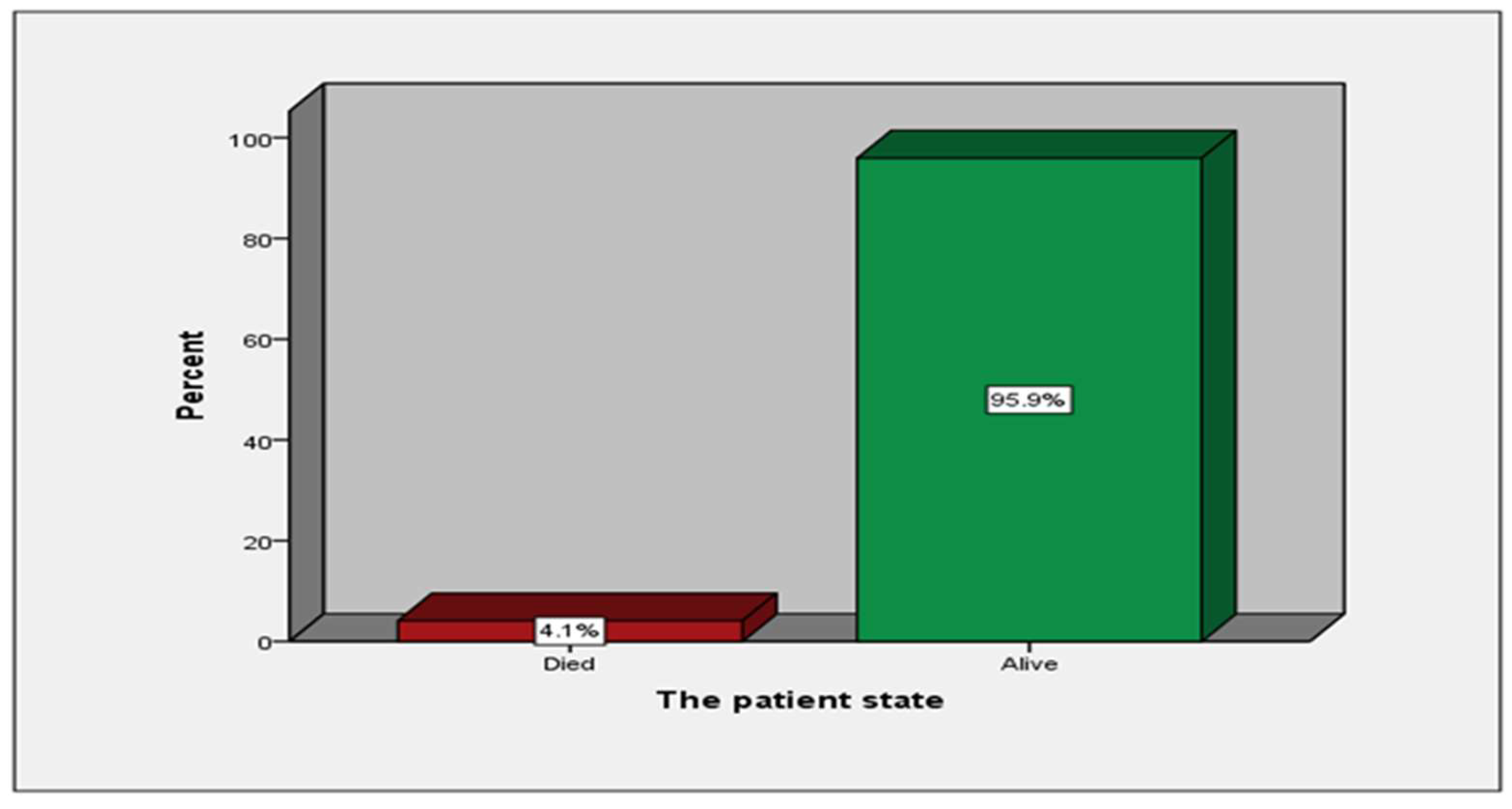

We’ve also found that out of the 270 patients, only 11 (4.1%) patients are deceased; this result is similar to a randomized clinical trial; they enrolled 274 patients, approximately equal to our sample size, out of those, only 6 (2%) patients had died all of which were judged as unrelated to treatment (7) (

Table 4,

Figure A6).

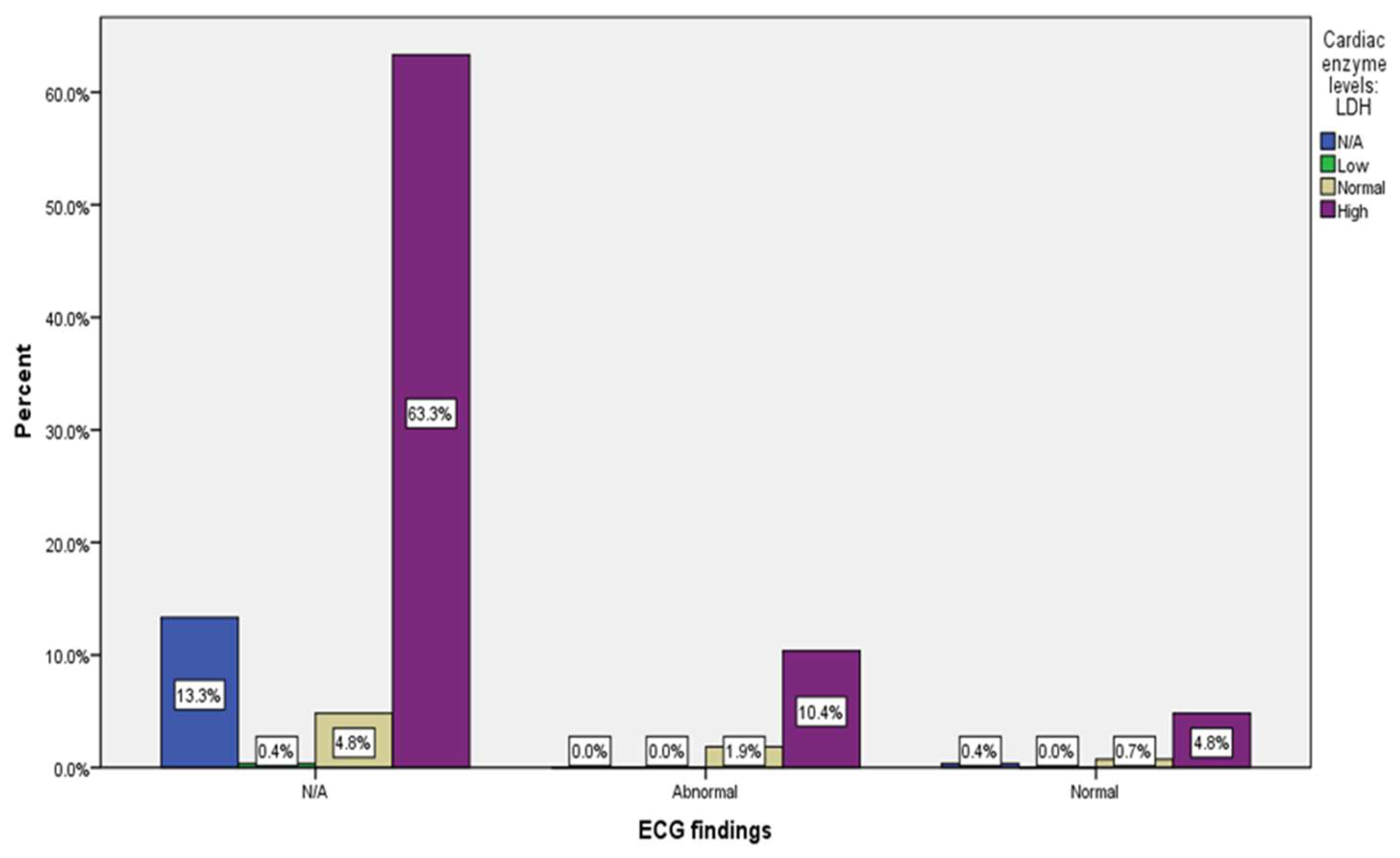

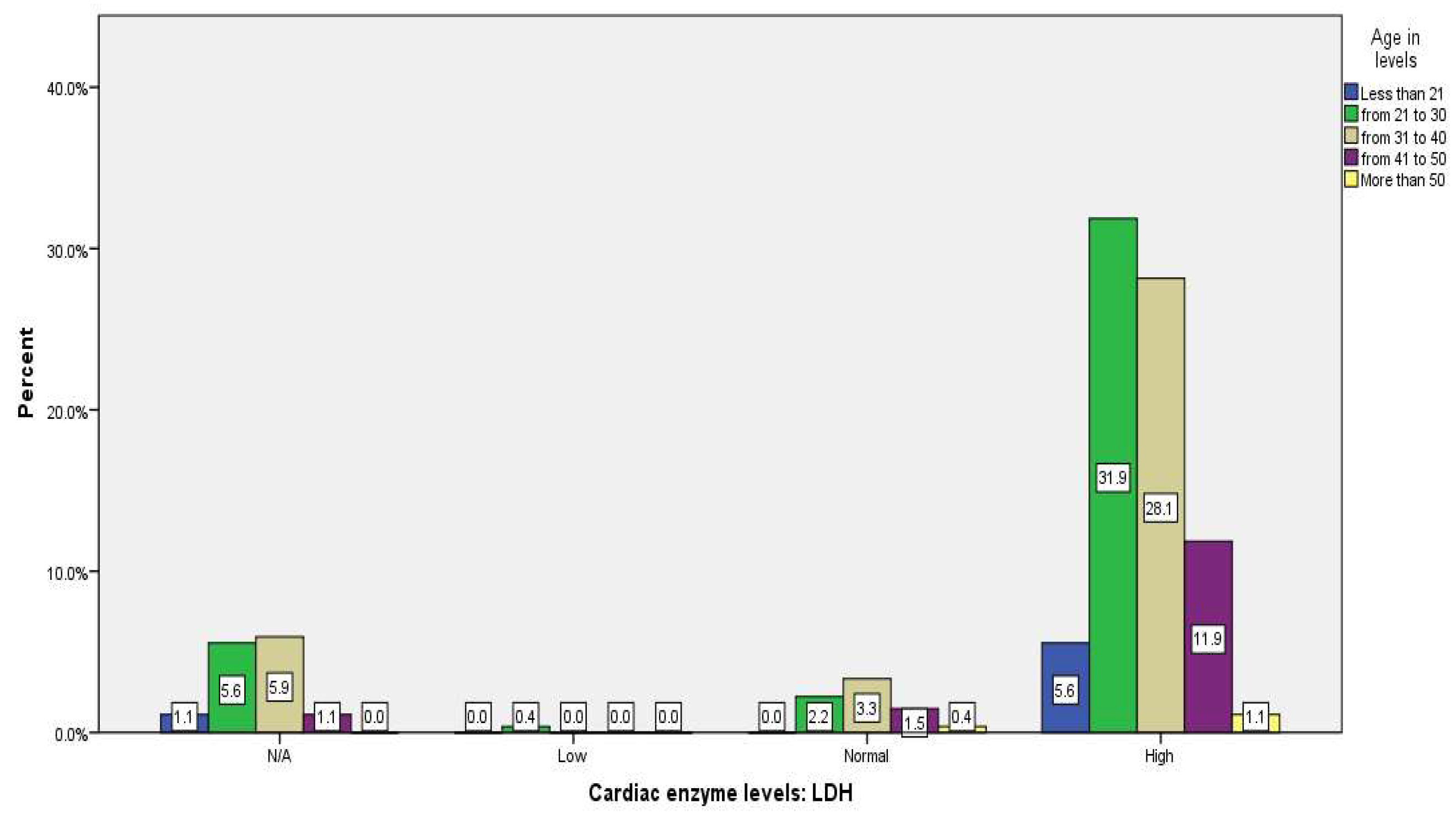

The results revealed that compared to other cardiac markers, patients with high LDH visited the ER most frequently (

Table 3,

Figure A3,A4,A5). Various mechanisms elevate LDH in SCD patients, including intravascular hemolysis, ischemia-reperfusion damage, and tissue necrosis (8). There are five isoenzymes for LDH: LDH-1 to LDH-5. LDH-1 specifically marks myocardial damage, and LDH-2 indicates more red blood cell breakdown but can still be elevated in myocardial damage (9). Testing for LDH at our institution does not discriminate between isoenzymes, and the elevated LDH doesn't necessarily imply myocardial infarction. Moreover, prior studies proved that LDH is strongly correlated with the markers of hemolysis (10, 11); this explains why most patients who visited the ER had high LDH in this study(

Table 3,

Figure A5).It also showed that 3.7% with elevated LDH have died; even though ten out of 11 cases with high LDH have passed away, there is an increased number of alive patients with high LDH (74.8%)(

Figure A5,A8).. Another study showed a clear trend toward an association between LDH and all-cause mortality. However, it did not reach statistical significance (12).

Our study showed elevated levels of troponin (9.3%) and a significant relationship between high troponin levels and mortality. We found that 5.9% of those with elevated troponin have died (

Table 3,

Figure A7,A8,A9). Also, another study found that troponin elevation significantly increases the likelihood of death with a hazard ratio of 2.6 (13). Another paper showed high troponin levels during the vaso-occlusive crisis but without the mortality association (14). Furthermore, a study showed a marked elevation of troponin in patients with SCD. Still, it was not related to the traditional cardiovascular risk factors but somewhat related to the hemolytic burden and pulmonary hypertension, which they thought was why SCD affects the heart and ultimately increases the mortality rate (15) .

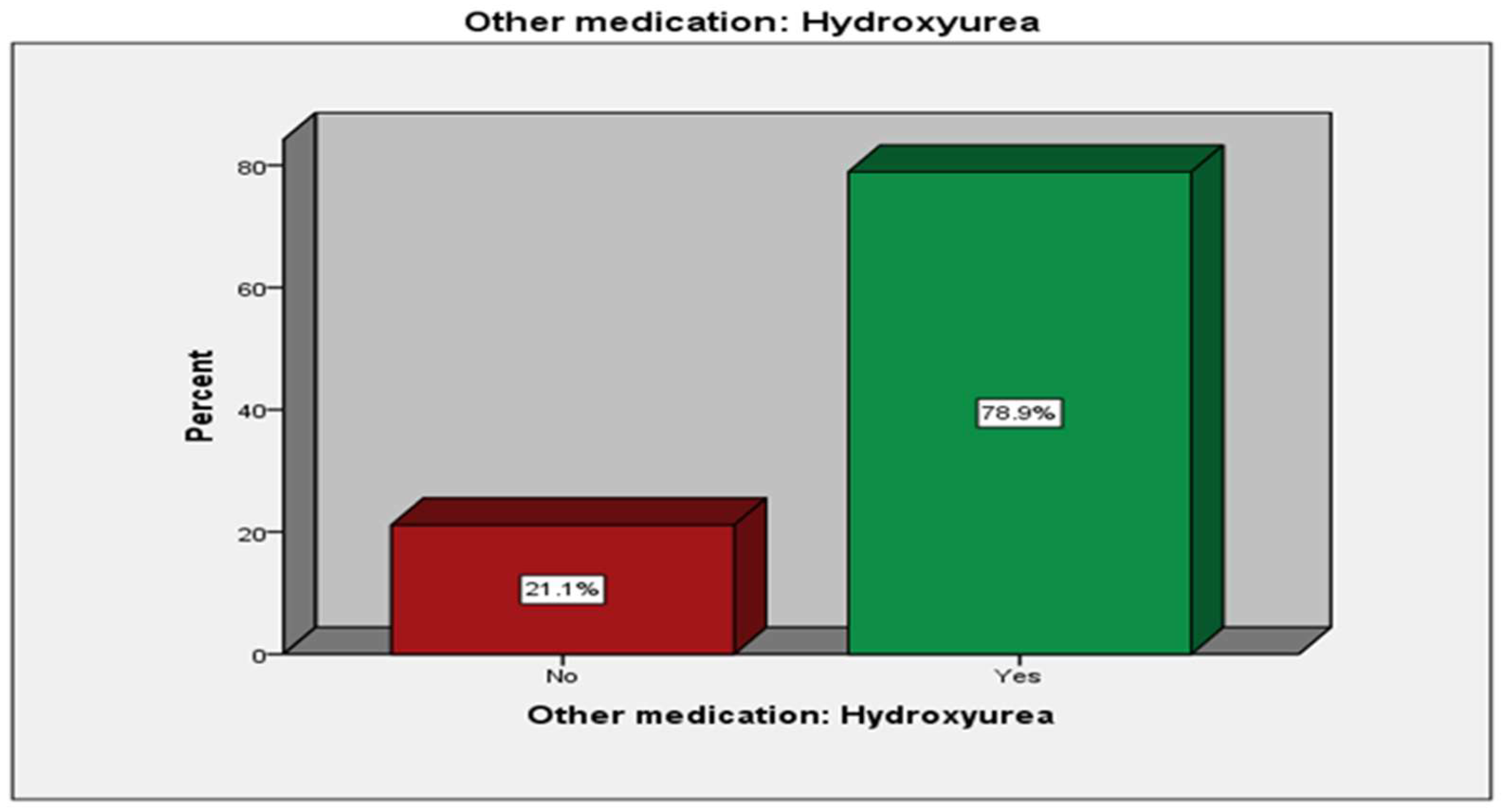

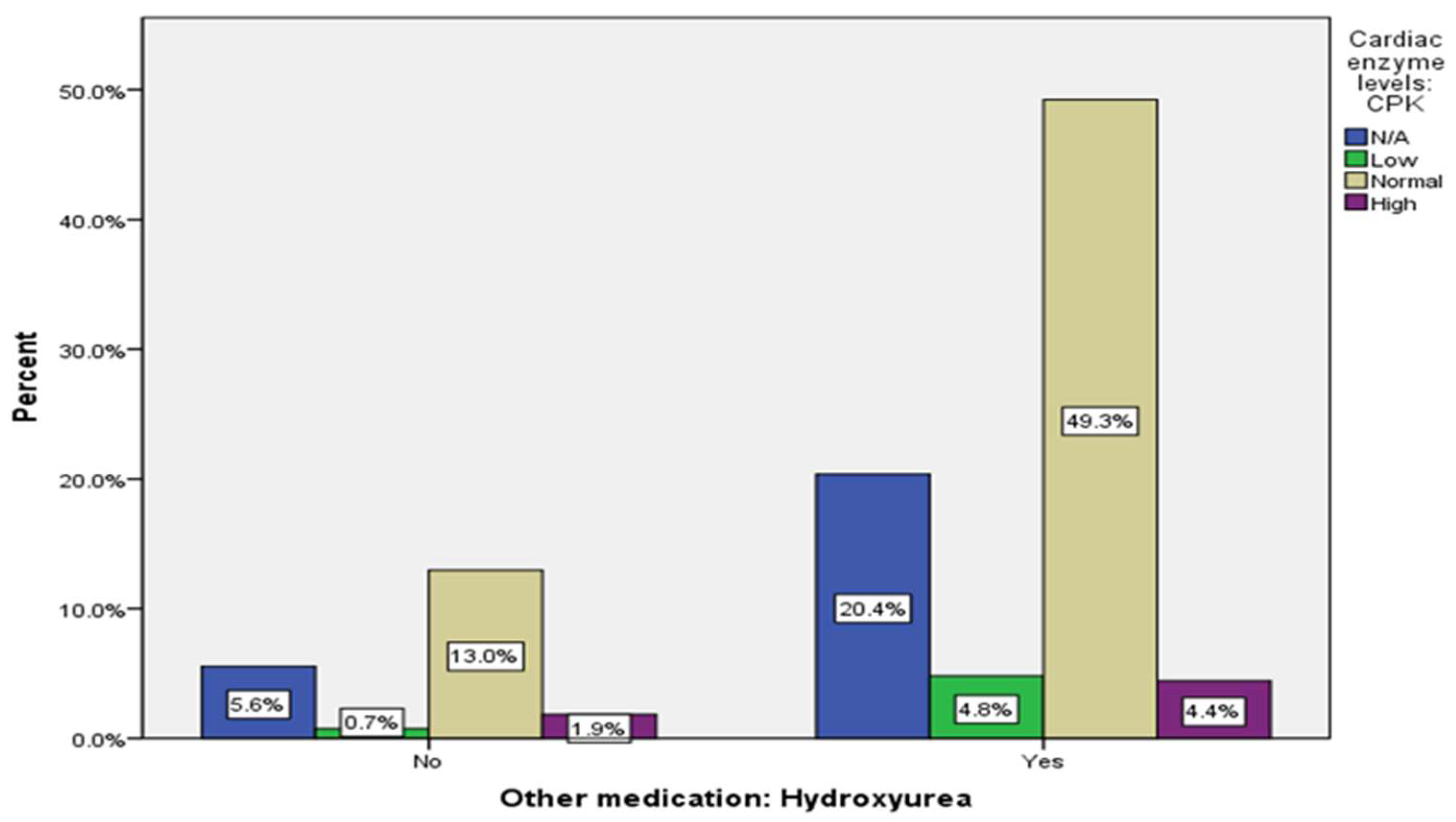

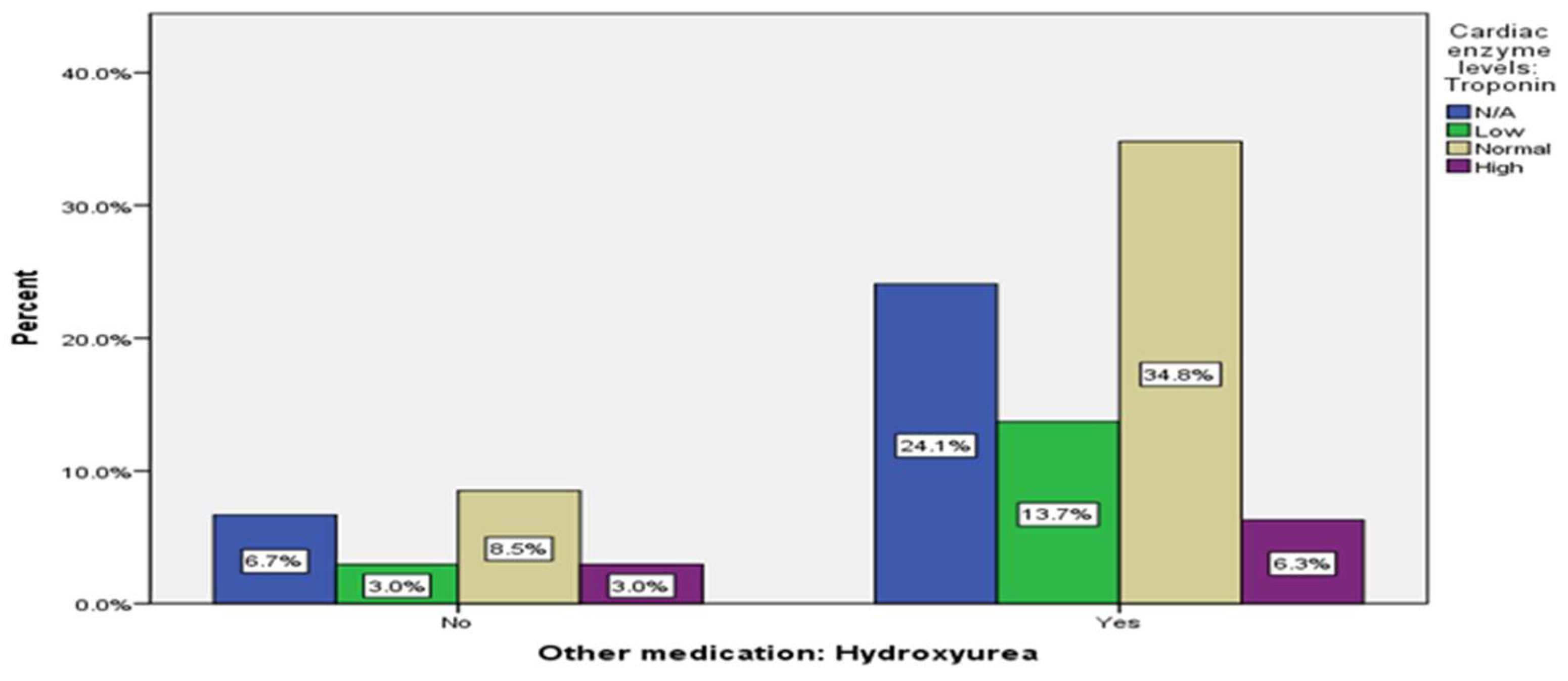

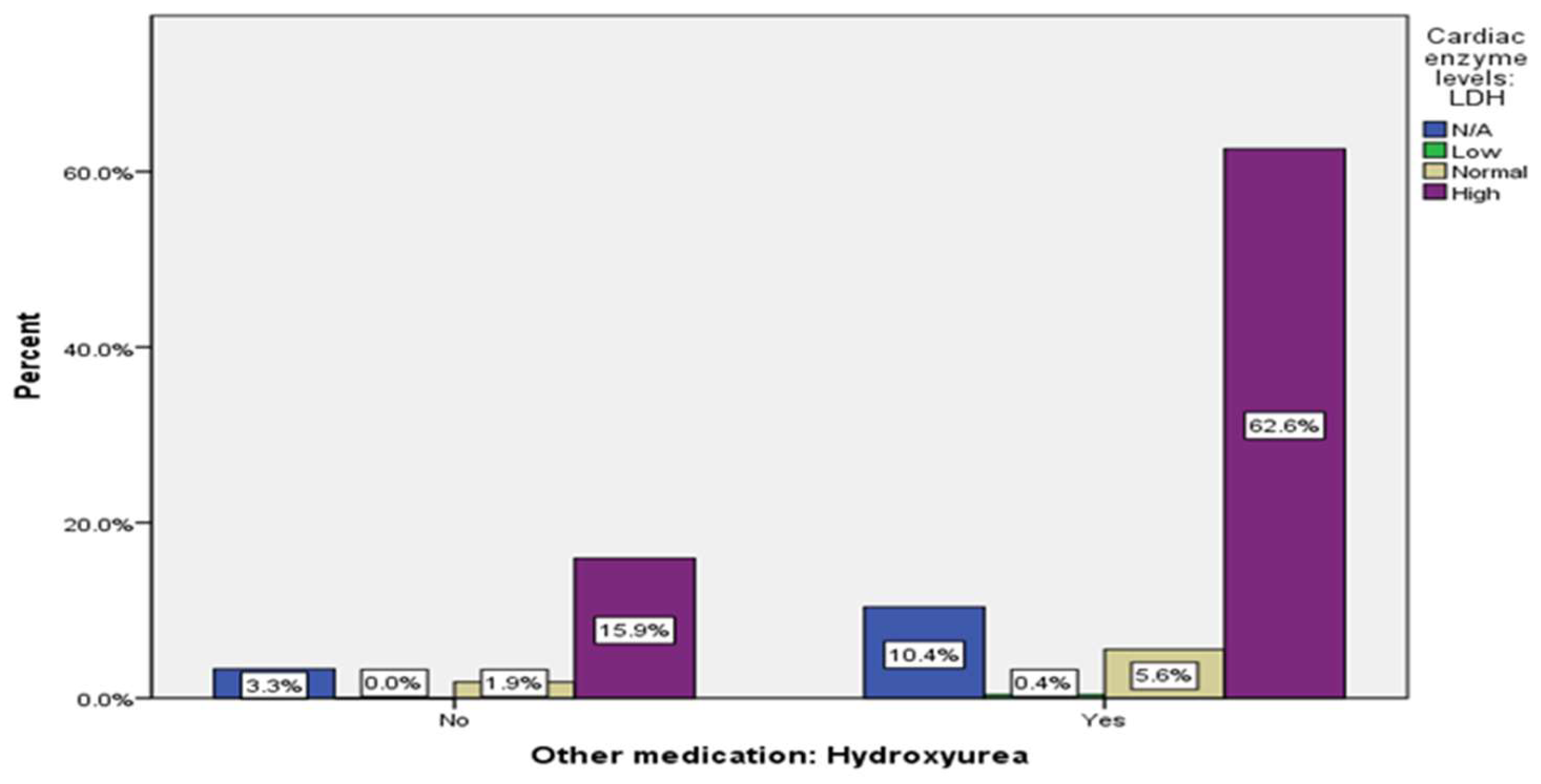

While multiple medication options are available for SCD, hydroxyurea is the most effective in reducing the frequency of painful crises, spleen dysfunction, pulmonary hypertension, and other complications (16). Studies have confirmed that hydroxyurea reduces the frequency and severity of painful crises, decreases the reliance on blood transfusions, and enhances overall survival rates in patients with SCD. Hydroxyurea is also relatively safe and well-tolerated, with minimal adverse effects reported by patients (16, 17). In our cohort, we found no relevant connection between the use of hydroxyurea and elevated cardiac markers (

Table 3,

Table 4 Figure A10,

Figure A11,

Figure A12,

Figure A13). During vaso-occlusive crisis (VOC) , elevated troponin and galectin protein levels were observed, indicating myocardial damage (18). However, multiple studies suggest that hydroxyurea may reduce VOC and help prevent the occurrence of acute coronary syndrome (19, 20). Based on the findings of those studies and previous research, hydroxyurea has become the standard of care for many SCD patients due to its success rate and safety profile.

Table 4.

Descriptive analysis.

Table 4.

Descriptive analysis.

| Variable |

Group |

N |

% |

| Patient state |

Died |

11 |

(4.1%) |

| Alive |

259 |

(95.9%) |

| Using Hydroxyurea |

No |

57 |

(21.1%) |

| Yes |

213 |

(78.9%) |

| Need for blood transfusion |

No |

46 |

(17%) |

| Yes |

224 |

(83%) |

| Age |

Minimum |

0 |

3.7% |

| Maximum |

2740 |

0.4% |

| Mean |

40 |

|

| Median |

7 |

|

| Standard deviation |

228 |

|

| Number of blood transfusion |

Simple transfusion |

Minimum |

0 |

|

| Maximum |

180 |

|

| Mean |

12 |

|

| Standard deviation |

22 |

|

| Exchange transfusion |

Minimum |

0 |

|

| Maximum |

94 |

|

| Mean |

7 |

|

| Standard deviation |

17 |

|

| Total transfusion |

Minimum |

0 |

|

| Maximum |

215 |

|

| Mean |

20 |

|

| Standard deviation |

36 |

|

| ECG |

N/A |

221 |

(81.9%) |

| Abnormal |

33 |

(12.2%) |

| Normal |

16 |

(5.9%) |

| Age |

Minimum |

19 |

|

| Maximum |

82 |

|

| Mean |

32.2 |

|

| Median |

32 |

|

| Standard deviation |

8.78 |

|

| Antiplatelets/ Anticoagulant medication |

No |

28 |

(10.4%) |

| Yes |

242 |

(89.6%) |

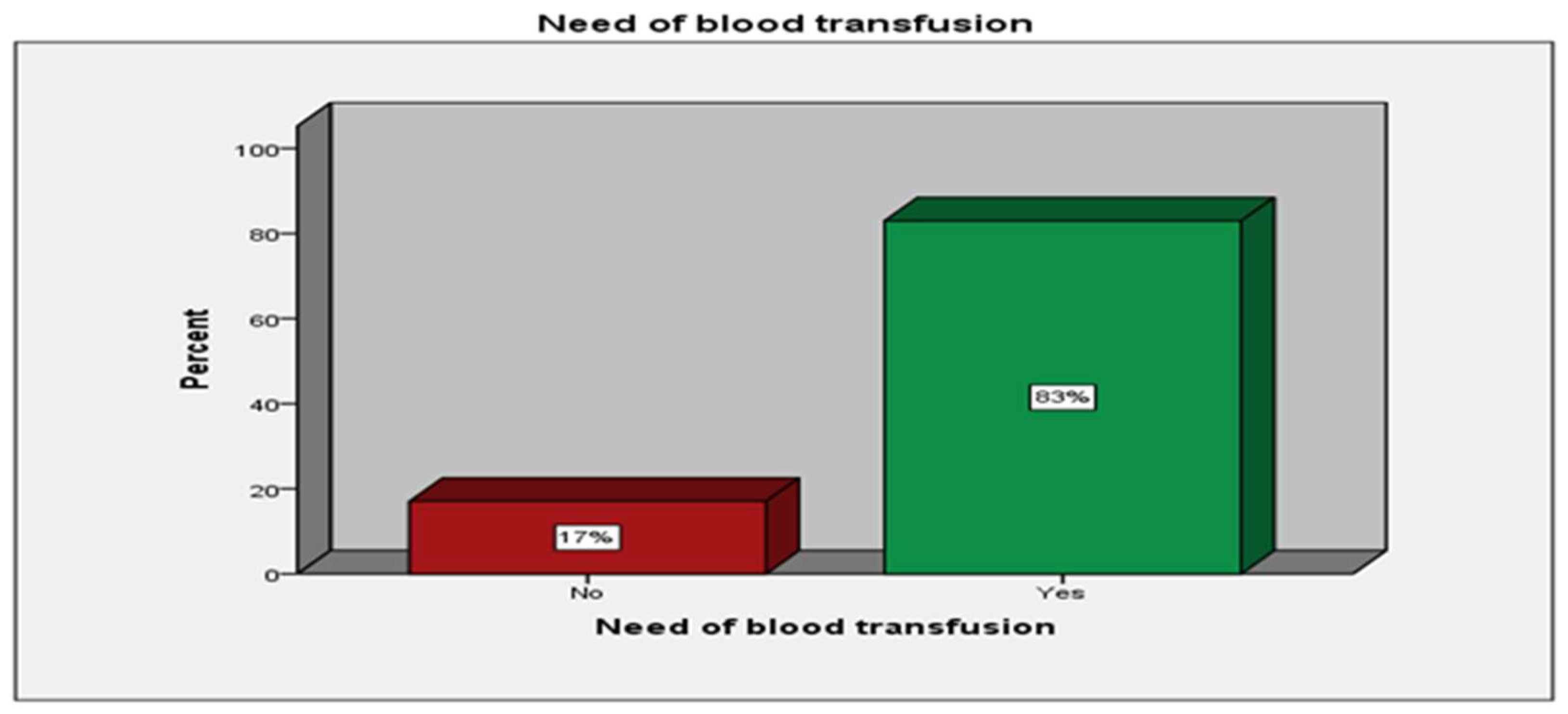

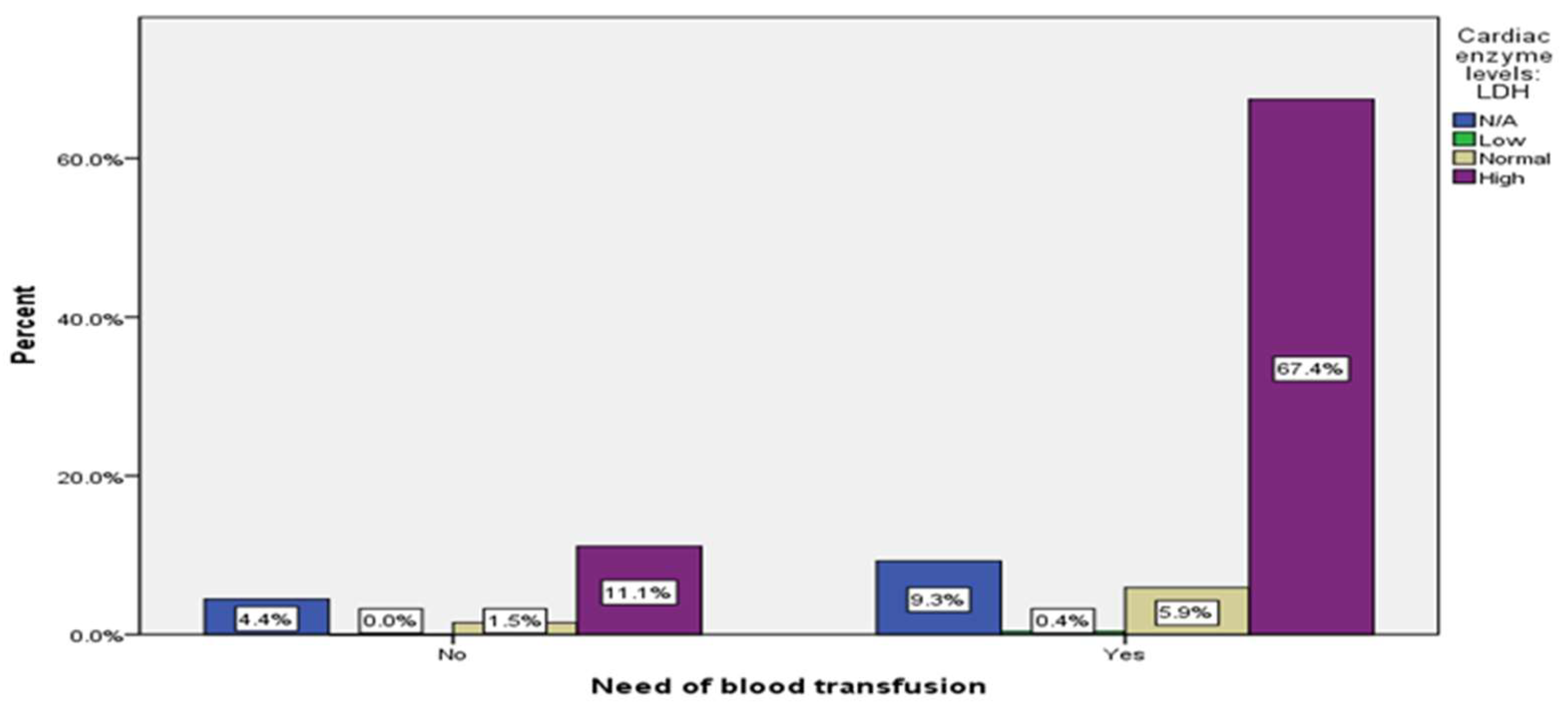

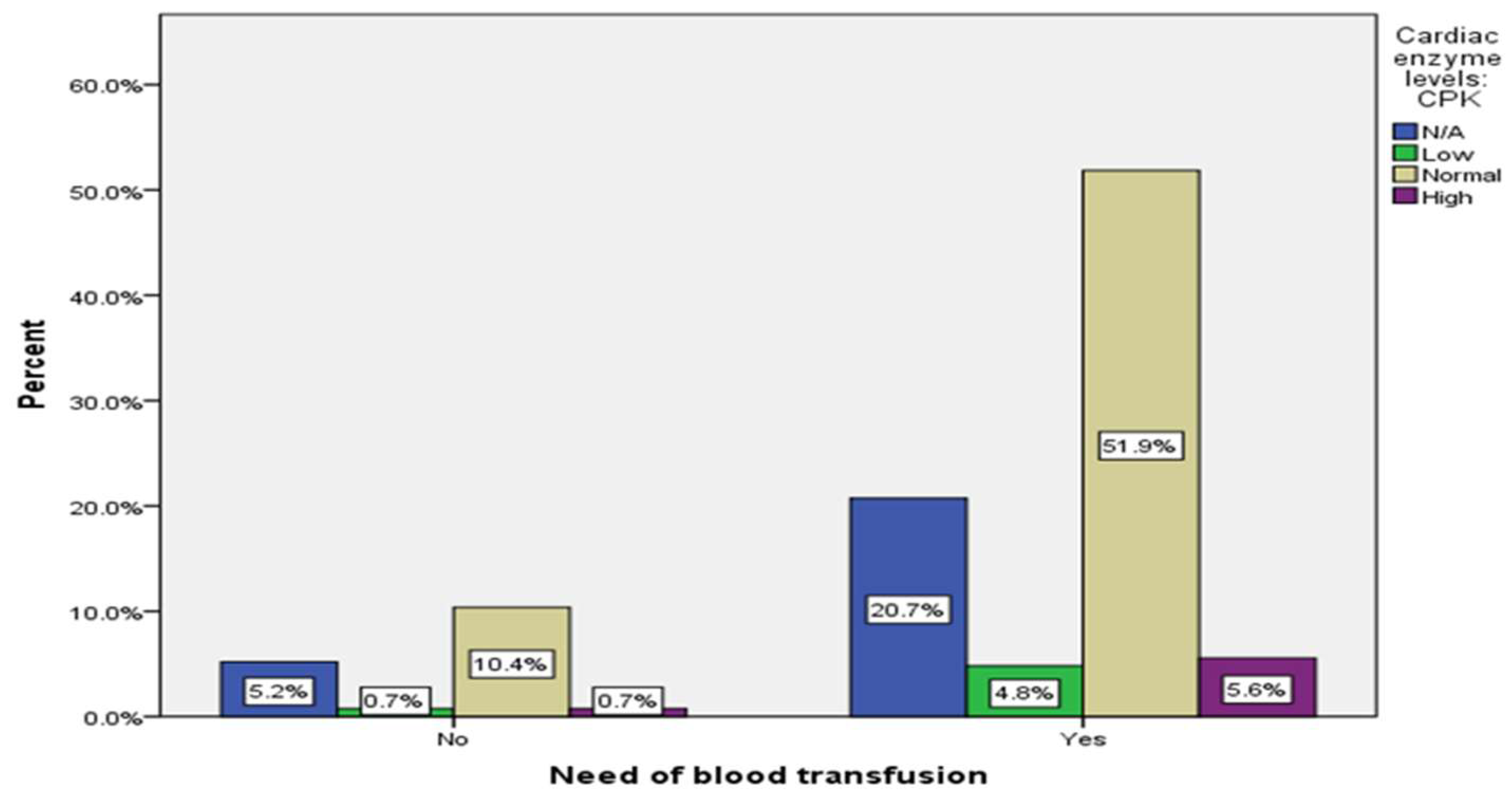

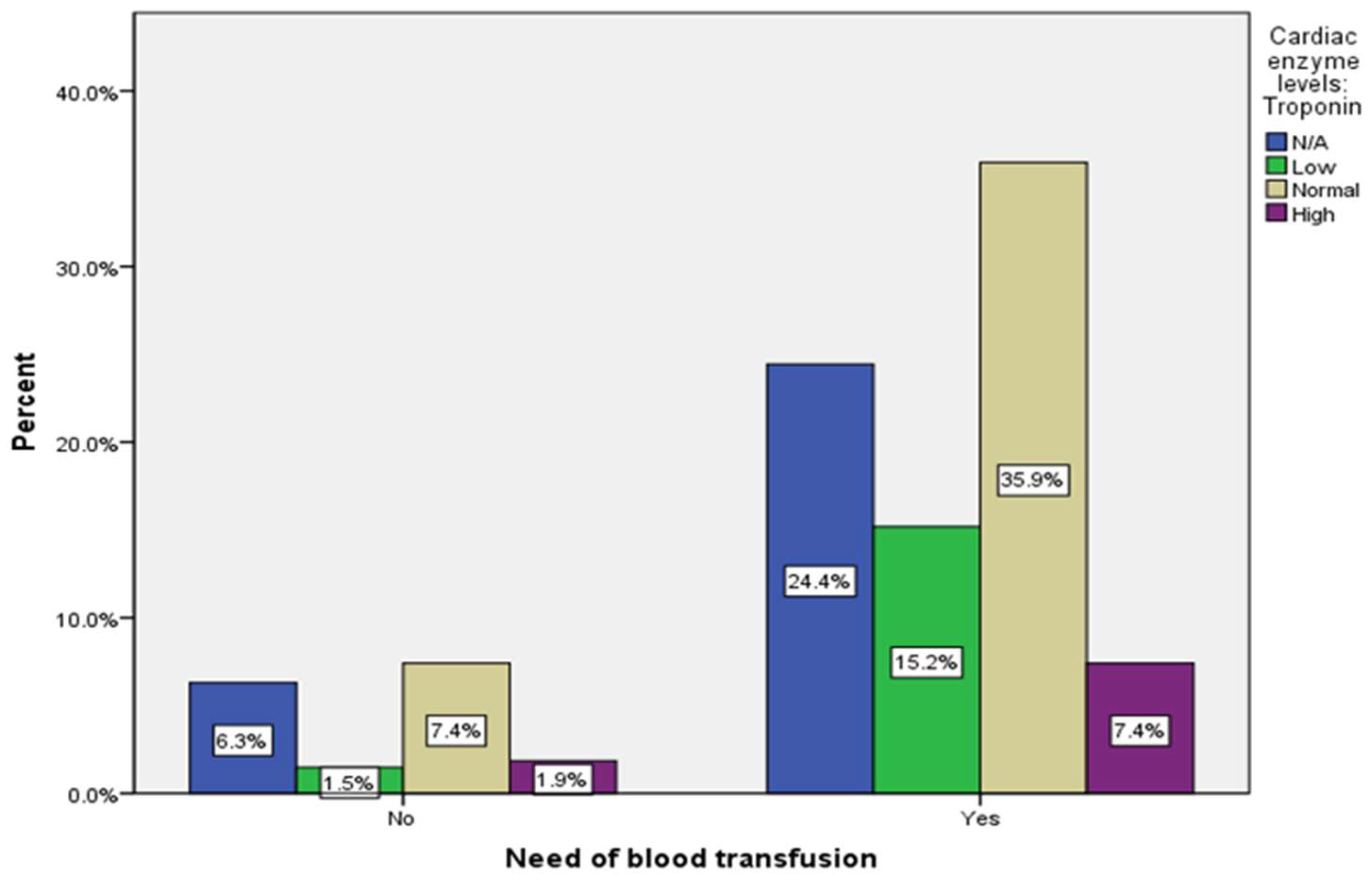

Patients with SCD often require blood transfusions to manage their symptoms, including replacing unhealthy sickled cells with healthy red blood cells. According to a systematic review by Akaba et al., transfusion therapy is crucial in managing SCD and reducing potential complications associated with the disease (21). In our study, 83% of participants required blood transfusions, while 17% did not (

Table 3,

Figure A14).. While blood transfusions are a widely used treatment option for SCD, there is no established connection between blood transfusion and cardiac markers levels. Previous studies have not tested the relationship between blood transfusion and cardiac enzyme levels. However, a 2008 study found that six patients with myocardial infarction (MI) survived after receiving a simple blood transfusion (22). This suggests that blood transfusions may reduce cardiovascular complications in patients with SCD. Although there was no significant association between blood transfusion and cardiac markers, individuals who required blood transfusions had normal troponin and CK levels (41.9%), (60.4%) respectively, while LDH levels were high (76.3%) (

Table 3,

Figure A15, A16, A17). LDH is known to be closely correlated with intravascular hemolysis, as mentioned above, which is a medical emergency and an indication for blood transfusion in patients with SCD (23). Further investigations are needed to fully define the relationship between blood transfusions and cardiac markers in individuals with SCD.

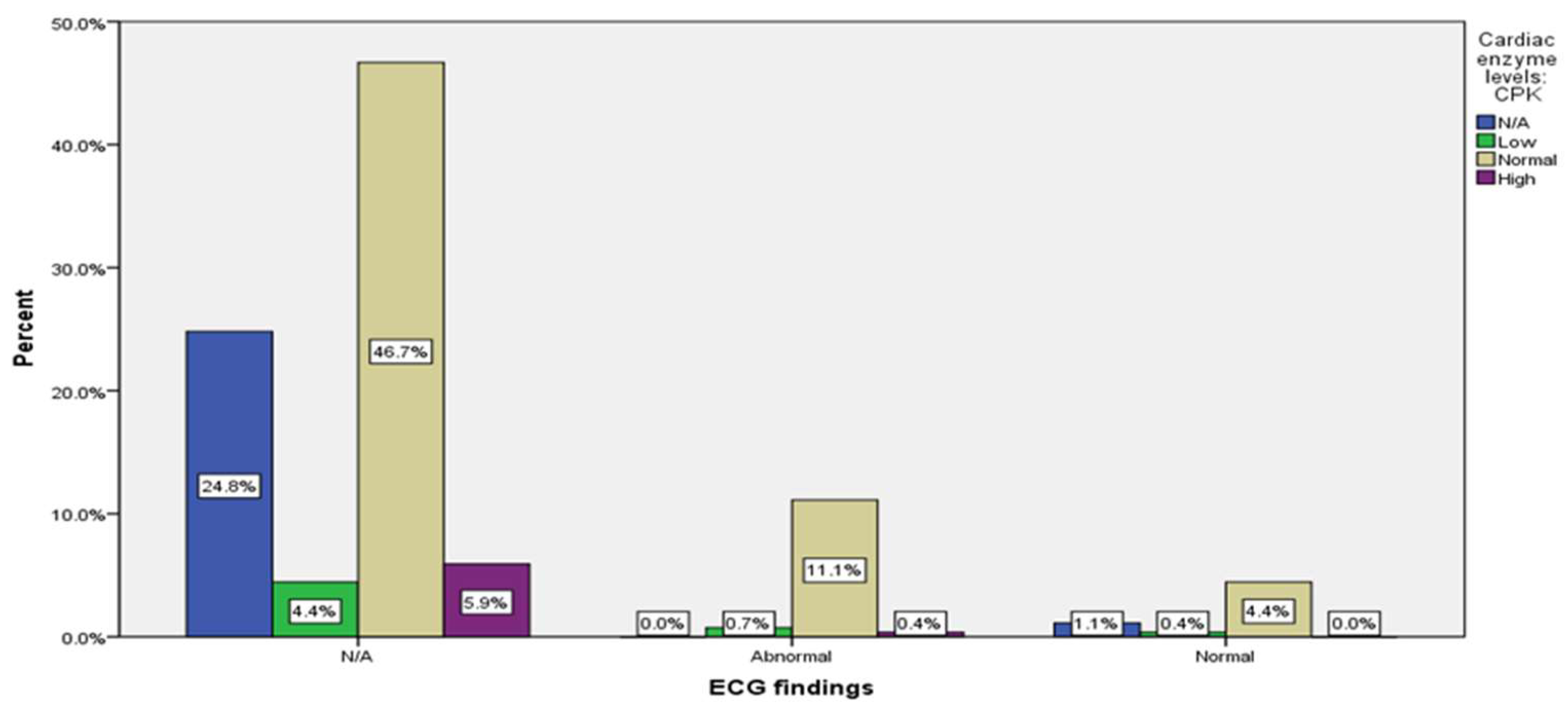

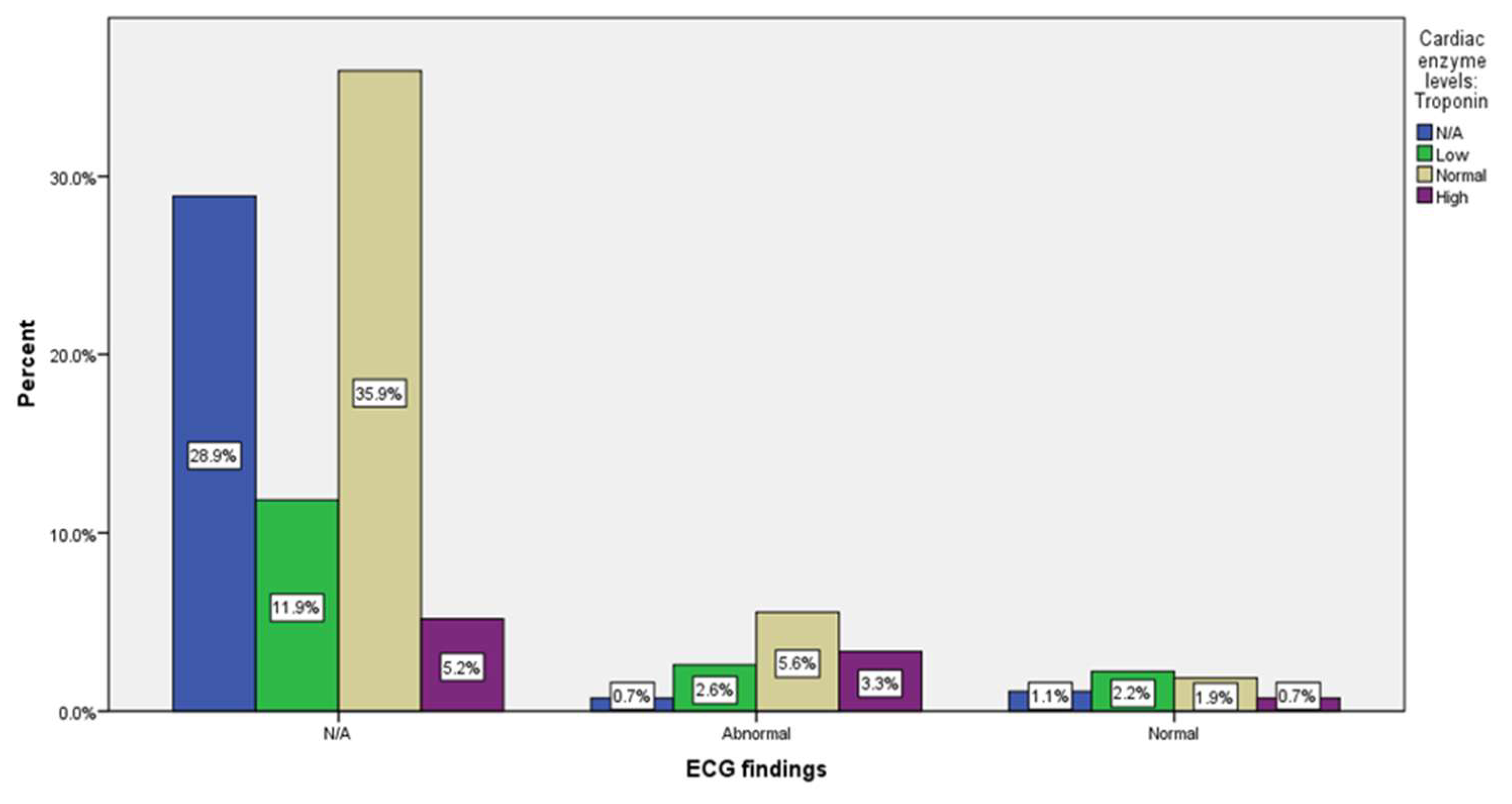

This study's finding suggests no evidence of a statistically significant correlation between electrocardiogram (ECG) changes and cardiac markers (

Table 3,

Figure A18,A19, A20). Furthermore, a review of 19 cases of documented MI in SCD by Ishak et al. demonstrates that ECG findings and cardiac markers are frequently unhelpful in diagnosing myocardial infarction in SCD patients (24). Also, a review by Voskaridou et al. reported that ECG is often unhelpful, as nonspecific ST-T wave changes commonly exist in SCD (25). Nonetheless, Dosunmo et al. stipulated that patient with SCD in a steady state tend to have ECG abnormalities before age 20 (26). However, the findings in this study could be inconclusive due to the nature of the data, as a large amount of data is unknown (82%).

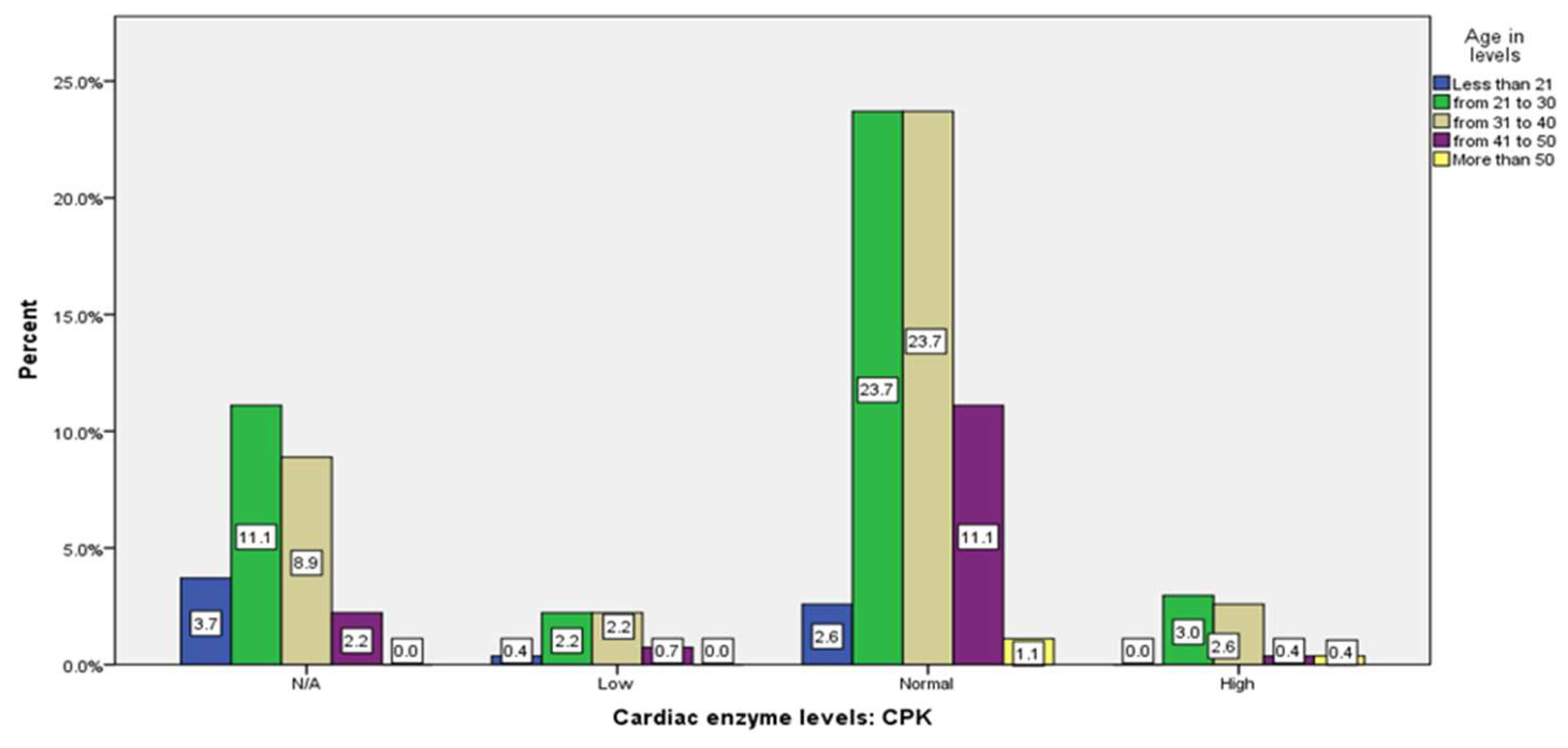

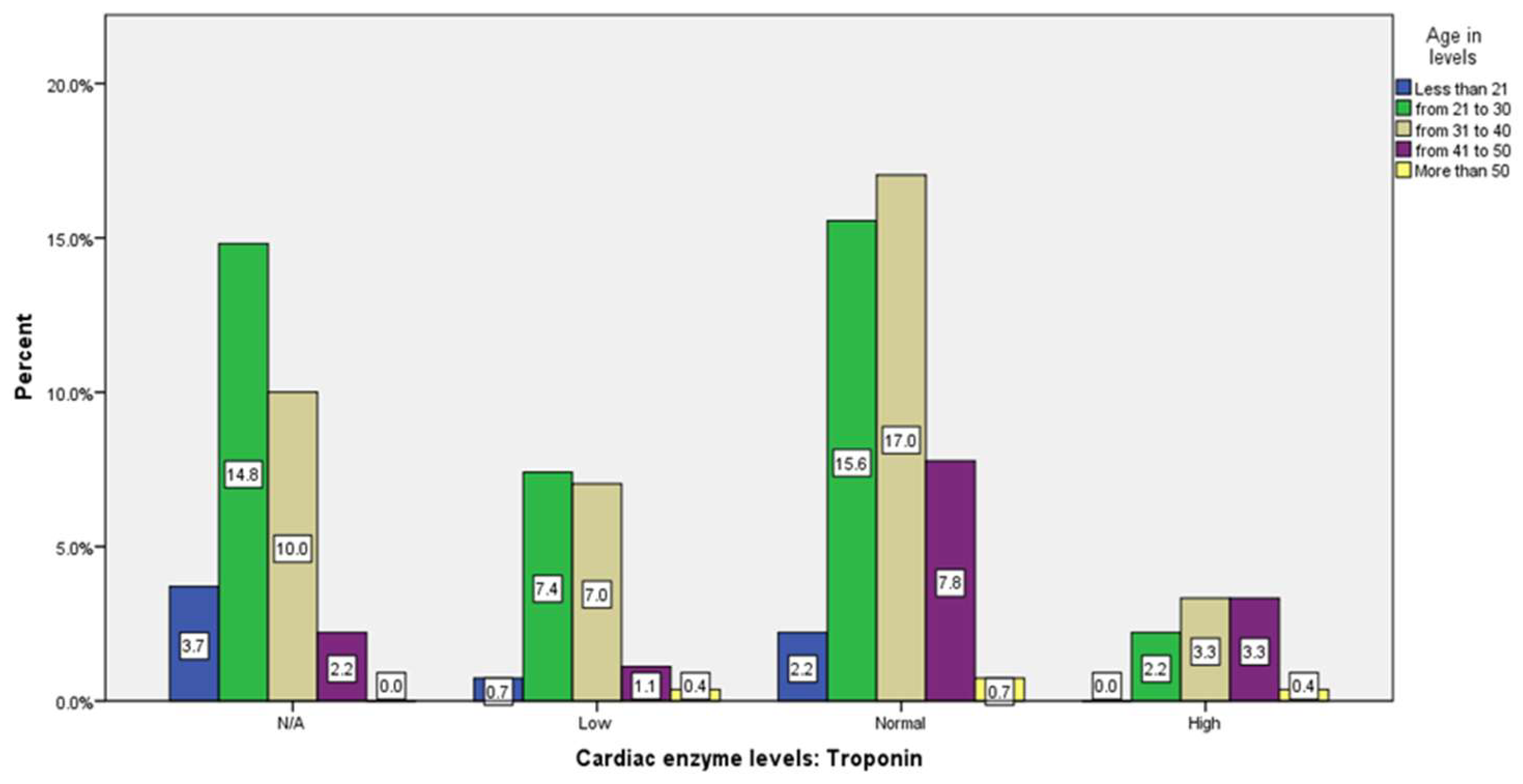

Our study showed a significant relationship between age and cardiac markers level CK-MB and Troponin (p=0.001) . The majority from age group ( 21 - 30), (31 to 40), and (more than 50 years old) have normal levels (23.7%, 23.7%, and 1.1% respectively), while less than 21 years old the CPK level most of them are N/A (3.7).Moreover , Age and cardiac enzyme (troponin) level demonstrated a moderate correlation. The majority of the age groups (21-30),(31-40), and (41-50), had a normal troponin level (15.6%, 17% and 7.8% respectively) and mainly high in the (31-40) and (41-50) groups (3.3%, 3.3%.) while being low in (21-30) and (31-40) age groups (7.4% ,7%). (

Table 3,

Figure A21, A22, A23). Although No previous studies have assessed the relationship between age and cardiac markers levels in adult patients with SCD specifically . A study by Ali et al. consisting of 289 patients with SCD, with an age range from 6 months to 18 years, showed that cardiac abnormalities in patients with SCD correlate with the age of the patients and the severity of the disease (27).

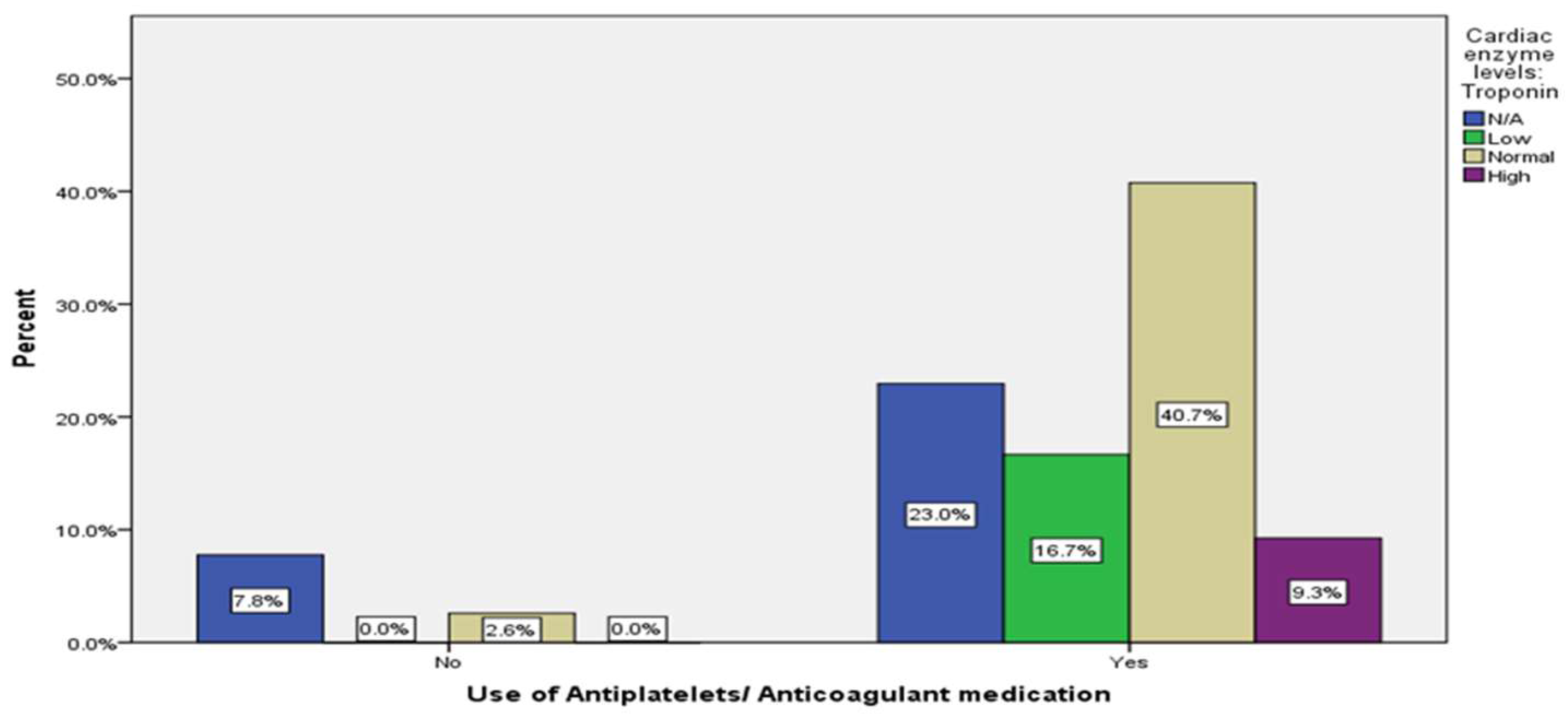

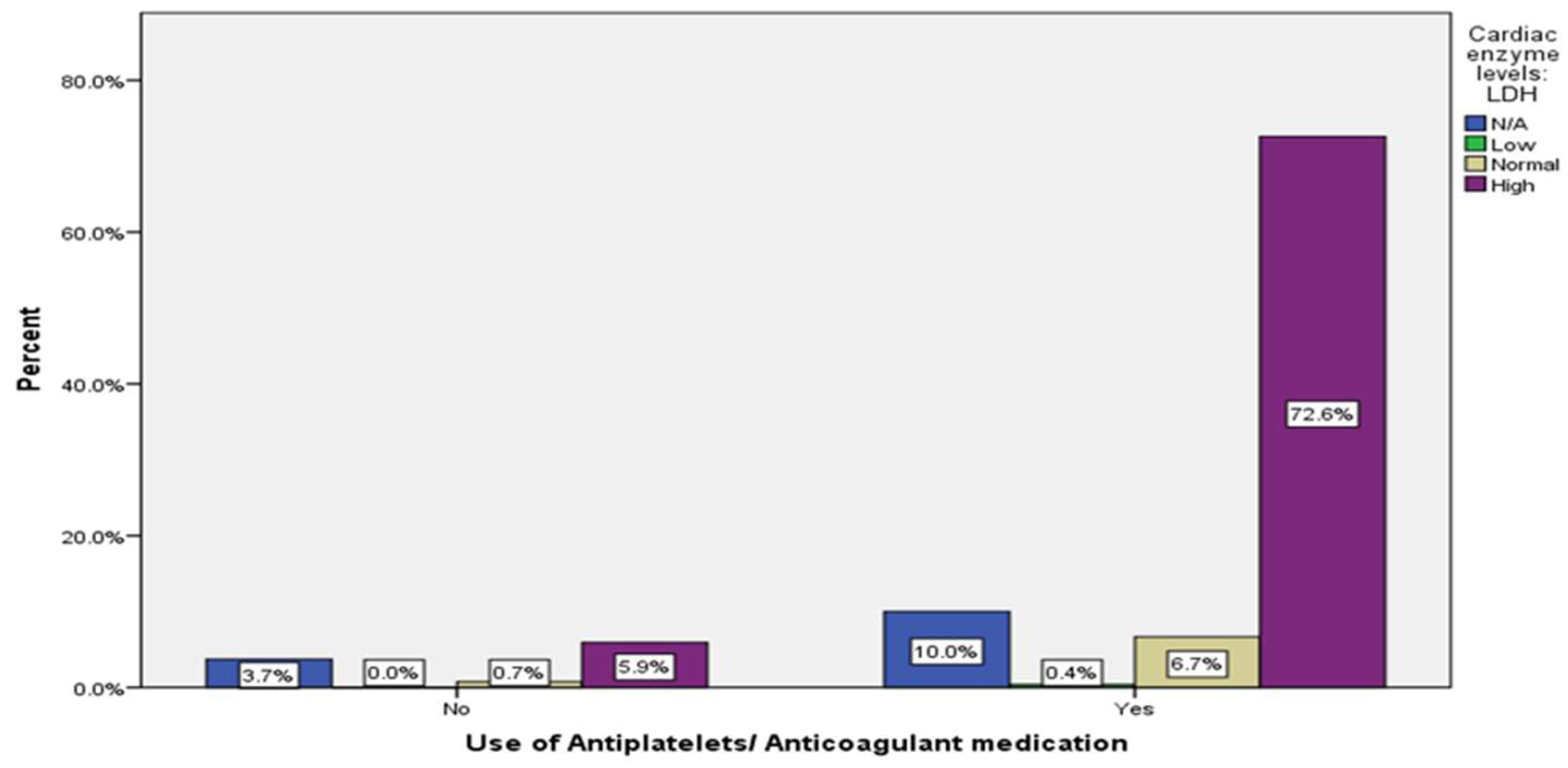

Patients with SCD commonly exhibit altered platelet function, activation, inflammation, and endothelial dysfunction. Hence, it places them in a high-risk category for thrombotic complications (28). Although some studies have attempted to establish a connection between the use of antiplatelet medications and a decrease in VOC, there is no conclusive evidence regarding using antiplatelet agents to prevent VOCs in SCD patients (29). The studies investigating the association between anticoagulants and cardiac markers have been limited in number. Furthermore, while this research demonstrated no relationship between antiplatelet use and variations in cardiac markers (

Table 3,4

Figure A24, A25) , additional research is required to monitor the extended use of antiplatelet agents and assess their impact on cardiac markers levels.

Notably, limitations of this study include the possibility of inaccuracies in the documentation of patients' data given the retrospective nature of the study. Additionally, since the study was conducted in a specific region in Saudi Arabia, its findings may not accurately reflect other areas. Thus, further research is necessary to confirm the significance of cardiac markers in SCD, particularly in other regions.

5. Conclusions

The study identifies a significant correlation between elevated cardiac markers levels and patient age, frequency of ER visits, and mortality rates. Specifically, most patients visiting the ER had high LDH levels, while elevated troponin levels were associated with increased mortality rates, potentially indicating damage to cardiomyocytes. We also found that many factors can affect the sensitivity of cardiac markers in patients with SCD in diagnosing MI, thus rendering the diagnosis of MI in SCD imprecise.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Adel Almarzouki and Osman Radhwi ;Methadology: Nadin Alharbi, Sondos jar and Weam Bajunaid and Abdulaziz Alzahrani and Majed Alhuzali;Software: Adel Almarzouki and Osman Radhwi ;Validation: Adel Almarzouki and Osman Radhwi ;Formal analysis :Adel Almarzouki and Osman Radhwi, Nadin Alharbi, Sondos jar and Weam Bajunaid and Abdulaziz Alzahrani and Majed Alhuzali;Investigation:Adel Almarzouki and Osman Radhwi, Nadin Alharbi, Sondos jar and Weam Bajunaid and Abdulaziz Alzahrani and Majed Alhuzali;Data curation: Nadin Alharbi, Sondos jar and Weam Bajunaid and Abdulaziz Alzahrani and Majed Alhuzali;Writing original draft preparation: Nadin Alhar Sondos jar and Weam Bajunaid and Abdulaziz Alzahrani and Majed Alhuzali; Writing, reviewing and editing: Adel Almarzouki and Osman Radhwi, Nadin Alharbi, Sondos jar and Weam Bajunaid and Abdulaziz Alzahrani and Majed Alhuzali; Visualization:Adel Almarzouki and Osman Radhwi ;Supervision: Adel Almarzouki and Osman Radhwi; Project administration: Adel Almarzouki and Osman Radhwi . All authors have read and agreed to the published version

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee (Reference No 360-22) at King Abdulaziz University hospital, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the Study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in a deidentified format via a secure data repository on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Sample Availability

Samples of the compounds are not available.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SCD |

Sickle cell disease |

| VOC |

Vaso-occlusive crisis |

| Hgb |

Beta-globin chain of hemoglobin |

| LDH |

Lactate dehydrogenase |

| CK-MB |

Creatine Kinase |

References

- Bunn, H.F. Pathogenesis and Treatment of Sickle Cell Disease. New England Journal of Medicine 1997, 337, 762–769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fitzhugh, C.; Lauder, N.; Jonassaint, J.; Telen, M.; Zhao, X.; Wright, E.; Gilliam, F.; De Castro, L. Cardiopulmonary Complications Leading to Premature Deaths in Adult Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. American journal of hematology 2010, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voskaridou, E.; Christoulas, D.; Terpos, E. Sickle-Cell Disease and the Heart: Review of the Current Literature. British Journal of Haematology 2012, 157, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gladwin, M.T.; Sachdev, V. Cardiovascular Abnormalities in Sickle Cell Disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2012, 59, 1123–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balbaid, E.A.; Murad, M. abdulaziz; Abousada, H.J.; Banjar, A.Y.; Taj, M.A.; Bamohsen, N.K.; Alghubishi, S.A.; Alrsheedi, A.J.M.; Alshanbari, N.F.; Alsahaqi, R.S.N.; et al. Prevalence of Pulmonary Hypertension in Sickle Cell Anemiai Patient in KSA. Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International 2021, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, M.; Shah, M.; Patel, B.; Nolan, V.G.; Reed, G.L.; Oudiz, R.J.; Choudhary, G.; Maron, B.A. Association between Pulmonary Hypertension and Clinical Outcomes in Hospitalized Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. 2018, 198, 534–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savale, L.; Habibi, A.; Lionnet, F.; Maitre, B.; Cottin, V.; Jais, X.; Chaouat, A.; Artaud-Macari, E.; Canuet, M.; Prevot, G.; et al. Clinical Phenotypes and Outcomes of Precapillary Pulmonary Hypertension of Sickle Cell Disease. European Respiratory Journal 2019, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J.; Ataga, K.I.; Brown, R.C.; Achebe, M.; Nduba, V.; El-Beshlawy, A.; Hassab, H.; Agodoa, I.; Tonda, M.; Gray, S.; et al. Voxelotor in Adolescents and Adults with Sickle Cell Disease (HOPE): Long-Term Follow-up Results of an International, Randomised, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled, Phase 3 Trial. The Lancet Haematology 2021, 8, e323–e333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stankovic Stojanovic, K.; Lionnet, F. Lactate Dehydrogenase in Sickle Cell Disease. Clinica Chimica Acta 2016, 458, 99–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, G.J.; McGowan, V.; Machado, R.F.; Little, J.A.; Taylor, J.; Morris, C.R.; Nichols, J.S.; Wang, X.; Poljakovic, M.; Morris, S.M.; et al. Lactate Dehydrogenase as a Biomarker of Hemolysis-Associated Nitric Oxide Resistance, Priapism, Leg Ulceration, Pulmonary Hypertension, and Death in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. Blood 2006, 107, 2279–2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kato, G.J.; Nouraie, S.M.; Gladwin, M.T. Lactate Dehydrogenase and Hemolysis in Sickle Cell Disease. Blood 2013, 122, 1091–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Vuren, A.J.; Minniti, C.P.; Mendelsohn, L.; Baird, J.H.; Kato, G.J.; van Beers, E.J. Lactate Dehydrogenase to Carboxyhemoglobin Ratio as a Biomarker of Heme Release to Heme Processing Is Associated with Higher Tricuspid Regurgitant Jet Velocity and Early Death in Sickle Cell Disease. American journal of hematology 2021, 96, E315–E318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaur, K.; Huang, Y.; Raman, S.V.; Kraut, E.; Desai, P. Myocardial Injury and Coronary Microvascular Disease in Sickle Cell Disease. Haematologica 2021, 106, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdev, V.; Rosing, D.R.; Thein, S.L. Cardiovascular Complications of Sickle Cell Disease. Trends in Cardiovascular Medicine 2020, 31, 187–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akkus, N.I.; Rajpal, S.; Hilbun, J.; Dwary, A.; Smith, T.R.; Mina, G.; Reddy, P.C. Troponin Elevation in Sickle Cell Disease. Medical Principles and Practice 2021, 30, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agrawal, R.K.; Patel, R.K.; shah, V.; Nainiwal, L.; Trivedi, B. Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Disease: Drug Review. Indian Journal of Hematology and Blood Transfusion 2013, 30, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yawn, B.P.; Buchanan, G.R.; Afenyi-Annan, A.N.; Ballas, S.K.; Hassell, K.L.; James, A.H.; Jordan, L.; Lanzkron, S.M.; Lottenberg, R.; Savage, W.J.; et al. Management of Sickle Cell Disease: Summary of the 2014 Evidence-Based Report by Expert Panel Members. JAMA 2014, 312, 1033–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reham Wagdy; Suliman, H.; Bashayer Bamashmose; Abrar Aidaroos; Haneef, Z.; Arunima Samonti; Awn, F. Subclinical Myocardial Injury during Vaso-Occlusive Crisis in Pediatric Sickle Cell Disease. European Journal of Pediatrics 2018, 177, 1745–1752. [CrossRef]

- Azmet, F.R.; Al-Kasim, F.; Alashram, W.M.; Siddique, K. The Role of Hydroxyurea in Decreasing the Occurrence of Vasso-Occulusive Crisis in Pediatric Patients with Sickle Cell Disease at King Saud Medical City in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal 2020, 41, 46–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkhalifah, S.A.; Alanazi, M.; Almasaoud, M.A.; Al-Malki, H.S.; Al-Murdhi, F.M.; Al-hazzaa, M.S.; Al-Mufarrij, S.M.; Albabtain, M.A.; Alshiakh, A.A.; AlRuthia, Y. The Impact of Hydroxyurea on the Rates of Vaso–Occlusive Crises in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease in Saudi Arabia: A Single–Center Study. BMC Emergency Medicine 2022, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaba, Kingsley, et al. “Transfusion Therapy in Sickle Cell Disease.” Journal of Blood & Lymph, 2019. Available online: www.hilarispublisher.com/open-access/transfusion-therapy-in-sickle-cell-disease.pdf.

- Pannu, R.; Zhang, J.; Andraws, R.; Armani, A.; Patel, P.; Mancusi-Ungaro, P. Acute Myocardial Infarction in Sickle Cell Disease: A Systematic Review. Critical Pathways in Cardiology 2008, 7, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marouf, R. Blood Transfusion in Sickle Cell Disease. Hemoglobin 2011, 35, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansi, I.A.; Rosner, F. Myocardial Infarction in Sickle Cell Disease. Journal of the National Medical Association 2002, 94, 448–452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Voskaridou, E.; Christoulas, D.; Terpos, E. Sickle-Cell Disease and the Heart: Review of the Current Literature. British Journal of Haematology 2012, 157, 664–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosunmu, A.; Akinbami, A.; Uche, E.; Adediran, A.; John-Olabode, S. Electrocardiographic Study in Adult Homozygous Sickle Cell Disease Patients in Lagos, Nigeria. Journal of Tropical Medicine 2016, 2016, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, G.O.M.; Abdal Gader, Y.S.; Abuzedi, E.S.; Attalla, B.A.I. Cardiac Manifestations of Sickle Cell Anaemia in Sudanese Children. Sudanese Journal of Paediatrics 2012, 12, 70–78. [Google Scholar]

- Srisuwananukorn, A.; Raslan, R.; Zhang, X.; Shah, B.N.; Han, J.; Gowhari, M.; Molokie, R.E.; Gordeuk, V.R.; Saraf, S.L. Clinical, Laboratory, and Genetic Risk Factors for Thrombosis in Sickle Cell Disease. Blood Advances 2020, 4, 1978–1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charneski, L.; Congdon, H.B. Effects of Antiplatelet and Anticoagulant Medications on the Vasoocclusive and Thrombotic Complications of Sickle Cell Disease: A Review of the Literature. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy 2010, 67, 895–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of study participants.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of study participants.

| Variable |

Groups |

n (%) |

| Gender |

Male |

126 (46.7) |

| Female |

144 (53.3) |

| Age group |

Less than 21 |

18 (6.7) |

| From 21 to 30 |

108 (40) |

| From 31 to 40 |

101 (37.4) |

| From 41 to 50 |

39 (14.4) |

| More than 50 |

4 (1.5) |

| Blood Group |

A- |

4 (1.5) |

| A+ |

68 (25.2) |

| AB+ |

11 (4.1) |

| B- |

2 (0.7) |

| B+ |

33 (12.2) |

| O- |

8 (3.0) |

| O+ |

144 (53.3) |

| Nationality |

Chadian |

21 (7.7) |

| Nigerian |

2 (0.7) |

| Pakistani |

4 (1.5) |

| Saudi |

163 (60.4) |

| Sudanese |

11 (4.1) |

| Syrian |

1 (0.4) |

| Yemeni |

68 (25.2) |

| Complication Related to the sickle cell disease |

No |

181 (67) |

| Yes |

89 (33) |

| Known chronic illness |

Thalassemia |

78 (29) |

| Hypertension |

13 (4.8) |

| Hepatitis C |

11 (4) |

| Kidney disease |

10 (3.7) |

| Epilepsy |

8 (3) |

| Hypothyroidism |

7 (2.6) |

| Asthma |

7 (2.6) |

| Diabetes |

6 (2.2) |

| Liver cirrhosis |

3 (1.1) |

| Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency |

3 (1.1) |

| Heart Failure |

3 (1.1) |

| Burkitt lymphoma |

2 (0.8) |

| Ischemic heart disease |

1 (0.4) |

| Crohn’s disease |

1 (0.4) |

| Pulmonary hypertension |

1 (0.4) |

| Lung fibrosis |

1 (0.4) |

| Hereditary spherocytosis |

1 (0.4) |

| Calculus of kidney |

1 (0.4) |

| Dyslipidemia |

1 (0.4) |

| Seckel syndrome |

1 (0.4) |

| Lupus nephritis |

1 (0.4) |

| Phenylketonuria |

1 (0.4) |

| Calculus of gallbladder |

1 (0.4) |

| Number of emergency room visits per year |

0 |

|

| 1-3 |

|

| 4-12 |

|

| >12 |

|

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis of cardiac enzyme level.

Table 2.

Descriptive analysis of cardiac enzyme level.

| Variable |

Group |

| N/A |

Low |

Normal |

High |

| Cardiac enzyme levels: CPK |

70

(25.9%) |

15

(5.6%) |

168

(62.2%) |

17

(6.3%) |

| Cardiac enzyme levels: Troponin |

83

(30.7%) |

45

(16.7%) |

117

(43.3%) |

25

(9.3%) |

| Cardiac enzyme levels: LDH |

37

(13.7%) |

1

(0.4%) |

20

(7.4%) |

212

(78.5%) |

Table 3.

association of cardiac enzyme with ER visit, patient state, using hydroxyurea, needing blood transfusion , ECG finding, age level, and antiplatelet/anticoagulant medication.

Table 3.

association of cardiac enzyme with ER visit, patient state, using hydroxyurea, needing blood transfusion , ECG finding, age level, and antiplatelet/anticoagulant medication.

| Variable |

Group |

ER visits |

Spearman’s Correlation |

The patient's state |

Rank biserial |

Using Hydroxyurea |

Rank biserial |

Needing blood transfusion |

Rank biserial |

ECG findings |

Rank biserial |

Age Levels |

Spearman’s |

P-value |

Antiplatelets/ Anticoagulant medication |

Rank biserial |

| No |

Yes |

Died |

Alive |

Correlation |

Significant |

No |

Yes |

Correlation |

Significant |

No |

Yes |

Correlation |

Significant |

N/A |

Abnormal |

Normal |

Correlation |

Significant |

Less than 21 |

21-30 |

31-40 |

41-50 |

More than 50 |

Correlation coefficient |

P-value |

No |

Yes |

Correlation |

Significant |

| Cardiac enzyme levels: CPK |

N/A |

4

(1.5%) |

66

(24.4%) |

0.0001 |

0

(0%) |

70

(25.9%) |

0.049 |

0.489 |

15

(5.6%) |

55

(20.4%) |

0.079 |

0.265 |

14

(5.2%) |

56

(20.7%) |

0.011 |

0.876 |

67

(24.8%) |

0

(0%) |

3

(1.1%) |

0.071 |

0.640 |

10

(3.7%) |

30

(11.1%) |

24

(8.9%) |

6

(2.2%) |

0

(0%) |

0.18 |

0.003** |

20

(7.4%) |

50

(18.5%) |

0.059 |

0.410 |

| Low |

0

(0%) |

15

(5.6%) |

1

(0.4%) |

14

(5.2%) |

2

(0.7%) |

13

(4.8%) |

2

(0.7%) |

13

(4.8%) |

12

(4.4%) |

2

(0.7%) |

1

(0.4%) |

1

(0.4%) |

6

(2.2%) |

6

(2.2%) |

2

(0.7%) |

0

(0%) |

0

(0%) |

15

(5.6%) |

| Normal |

5

(1.9%) |

163

(60.4%) |

8

(3%) |

160

(59.3%) |

35

(13%) |

133

(49.3%) |

28

(10.4%) |

140

(51.9%) |

126

(46.7%) |

30

(11.1%) |

12

(4.4%) |

7

(2.6%) |

64

(23.7%) |

64

(23.7%) |

30

(11.1%) |

3

(1.1%) |

7

(2.6%) |

161

(59.6%) |

| High |

1

(0.4%) |

16

(5.9%) |

2

(0.7%) |

15

(5.6%) |

5

(1.9%) |

12

(4.4%) |

2

(0.7%) |

15

(5.6%) |

16

(5.9%) |

1

(0.4%) |

0

(0%) |

0

(0%) |

8

(3%) |

7

(2.6%) |

1

(0.4%) |

1

(0.4%) |

1

(0.4%) |

16

(5.9%) |

| Cardiac enzyme levels: Troponin |

N/A |

6

(2.2%) |

77

(28.5%) |

0.0001 |

0

(0%) |

83

(30.7%) |

0.384 |

0.0001** |

18

(6.7%) |

65

(24.1%) |

0.088 |

0.231 |

17

(6.3%) |

66

(24.4%) |

0.102 |

0.164 |

78

(28.9%) |

2

(0.7%) |

3

(4.4%) |

0.232 |

0.130 |

10

(3.7%) |

40

(14.8%) |

27

(10%) |

6

(2.2%) |

0

(0%) |

0.29 |

0.0001 |

21

(7.8%) |

62

(23%) |

0.043 |

0.564 |

| Low |

0

(0%) |

45

(16.7%) |

0

(0%) |

45

(16.7%) |

8

(3%) |

37

(13.7%) |

4

(1.5%) |

41

(15.2%) |

32

(11.9%) |

7

(2.6%) |

6

(2.2%) |

2

(0.7%) |

20

(7.4%) |

19

(7%) |

3

(1.1%) |

1

(0.4%) |

0

(0%) |

45

(16>7%) |

| Normal |

4

(1.5%) |

113

(41.9%) |

2

(0.7%) |

115

(42.6%) |

23

(8.5%) |

94

(34.8%) |

20

(7.4%) |

97

(35.9%) |

97

(35.9%) |

15

(5.6%) |

5

(1.9%) |

6

(2.2%) |

42

(15.6%) |

46

(17%) |

21

(7.8%) |

2

(0.7%) |

7

(2.6%) |

110

(40>7%) |

| High |

0

(0%) |

25

(9.3%) |

9

(3.3%) |

16

(5.9%) |

8

(3%) |

17

(6.3%) |

5

(1.9%) |

20

(7.4%) |

14

(5.2%) |

9

(3.3%) |

2

(0.7%) |

0

(0%) |

6

(2.2%) |

9

(3.3%) |

9

(3.3%) |

1

(0.4%) |

0

(0%) |

25

(9.3%) |

| Cardiac enzyme levels: LDH |

N/A |

4

(1.5%) |

33

(12.2%) |

0.0001 |

0

(0%) |

37

(13.7%) |

0.0001 |

0.996 |

9

(3.3%) |

28

(10.4%) |

0.024 |

0.714 |

12

(4.4%) |

25

(9.3%) |

0.039 |

0.554 |

36

(13.3%) |

0

(0%) |

1

(0.4%) |

0.024 |

0.872 |

3

(1.1%) |

15

(5.6%) |

16

(5.9%) |

3

(1.1%) |

0

(0%) |

0.005 |

0.936 |

10

(3.7%) |

27

(10%) |

0.021 |

0.753 |

| Low |

0

(0%) |

1

(0.4%) |

0

(0%) |

1

(0.4%) |

0

(0%) |

1

(0.4%) |

0

(0%) |

1

(0.4%) |

1

(0.4%) |

0

(0%) |

0

(0%) |

0

(0%) |

1

(0.4%) |

0

(0%) |

0

(0%) |

0

(0%) |

0

(0%) |

1

(0.4%) |

| Normal |

0

(0%) |

20

(7.4%) |

1

(0.4%) |

19

(7%) |

5

(1.9%) |

15

(5.6%) |

4

(1.5%) |

16

(5.9%) |

13

(4.8%) |

5

(1.9%) |

2

(0.7%) |

0

(0%) |

6

(2.2%) |

9

(3.3%) |

4

(1.5%) |

1

(0.4%) |

2

(0.&%) |

18

(6.7%) |

| High |

10

(2.2%) |

206

(76.3%) |

10

(3.7%) |

202

(74.8%) |

43

(15.9%) |

169

(62.6%) |

30

(11.1%) |

182

(67.4%) |

171

(63.3%) |

28

(10.4%) |

13

(4.8%) |

15

(5.6%) |

86

(31.9%) |

76

(28.1%) |

32

(11.9%) |

3

(1.1%) |

16

(5.9%) |

196

(72.6%) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).