1. Introduction

1.1. Background of Study

In rural areas, those who can produce often have difficulties providing themselves with the necessary resources to increase their productive activity, especially with regard to accessing the banking financial market, which poses a challenge to reducing poverty and promoting economic development in these regions. The instruments and products of the banking financial sector are seen as a catalyst for increasing production and productivity in the productive sector and in particular the agricultural sector.

There are some risk factors inherent to rural activity, such as the climate, diseases and pests and price fluctuations in the consumer market. To protect themselves from these dangers, financial agents use some security measures when providing credit for agricultural activity. In particular, they adopt certain credit access requirements, especially when providing credit to smallholder farmers, such as real guarantees (real estate and purchasing agreements) and the establishment of high interest rates, in addition to onerous payment conditions.

Banks, the main credit granting institutions, play an important role in this production cycle because they provide financial capital (King and Levine 1993). With financial resources, rural producers can acquire inputs for their economic activities, generating wealth and helping to reduce rural poverty and exodus rates.

According to Schumpeter (2021, p. 108), the practical importance of credit, in addition to enabling development, is that it carries with it “the possibility of employing sums of money that are temporarily idle”. Credit is necessary to stimulate economic activity and, consequently, to generate profit. Borges and Parré (2022, p. 1) emphasize the importance of studying the impact of rural credit on many variables, such as production value, agricultural products, agribusiness products and total factor productivity.

1.2. Background of the Angolan Economy

Angola, located in southern Africa, is a least developed country with a gross domestic product (GDP) of approximately USD 120 billion, a population of 33 million and a per capita income estimate of USD 3600 (2022). It has the third largest economy in Sub-Saharan Africa, behind Nigeria and South Africa. The Angolan economy was built in colonial times to be an intensive exporting economy of agricultural products. Angola attained, as Wheeler and Pélissier (2009) mention, its “economic and financial autonomy” after the end of the Second World War, becoming an authentic “economy of coffee”.

Later, after Angola gained its independence, the country’s economy was heavily impacted by the Angolan Civil War, which began in 1975 and ended in 2002, and suffered from the so-called Dutch disease, using its oil sector as its main supplier of hard currency to import more than 90% of its consumed goods and services. Angola’s economy is still overwhelmingly driven by its oil sector, being the first oil producer in Sub-Saharan Africa to produce 1,12 million barrels per day (bpd). The country’s oil sector accounts for approximately 28% of its GDP, 85% of its overall exports, and 65% of its overall tax revenue. Since 2018, Angola has been changing this paradigm, focusing on its comparative advantages, and especially on re-launching its agribusiness sector.

1.3. Research Aim

This study identifies the impact of agricultural credit on agricultural growth in Angola in the period between 2003 and 2022. In particular, the study aims:

- (i)

To assess the factor of credit in the agricultural sector.

- (ii)

To critically evaluate the impact of credit on the growth of the agricultural sector.

- (iii)

To provide quantitative results regarding the impact of agri-credit on the growth of the agricultural sector.

- (iv)

To provide recommendations on the importance of credit for the growth of the agricultural sector.

Moreover, the study addresses the following research questions:

- (i)

Is credit provided to the agricultural sector a determinant of growth for the sector?

- (ii)

What is the impact of providing credit to the agricultural sector?

- (iii)

Should the amount of credit provided to the agricultural sector be increased?

1.6. Significance of Study

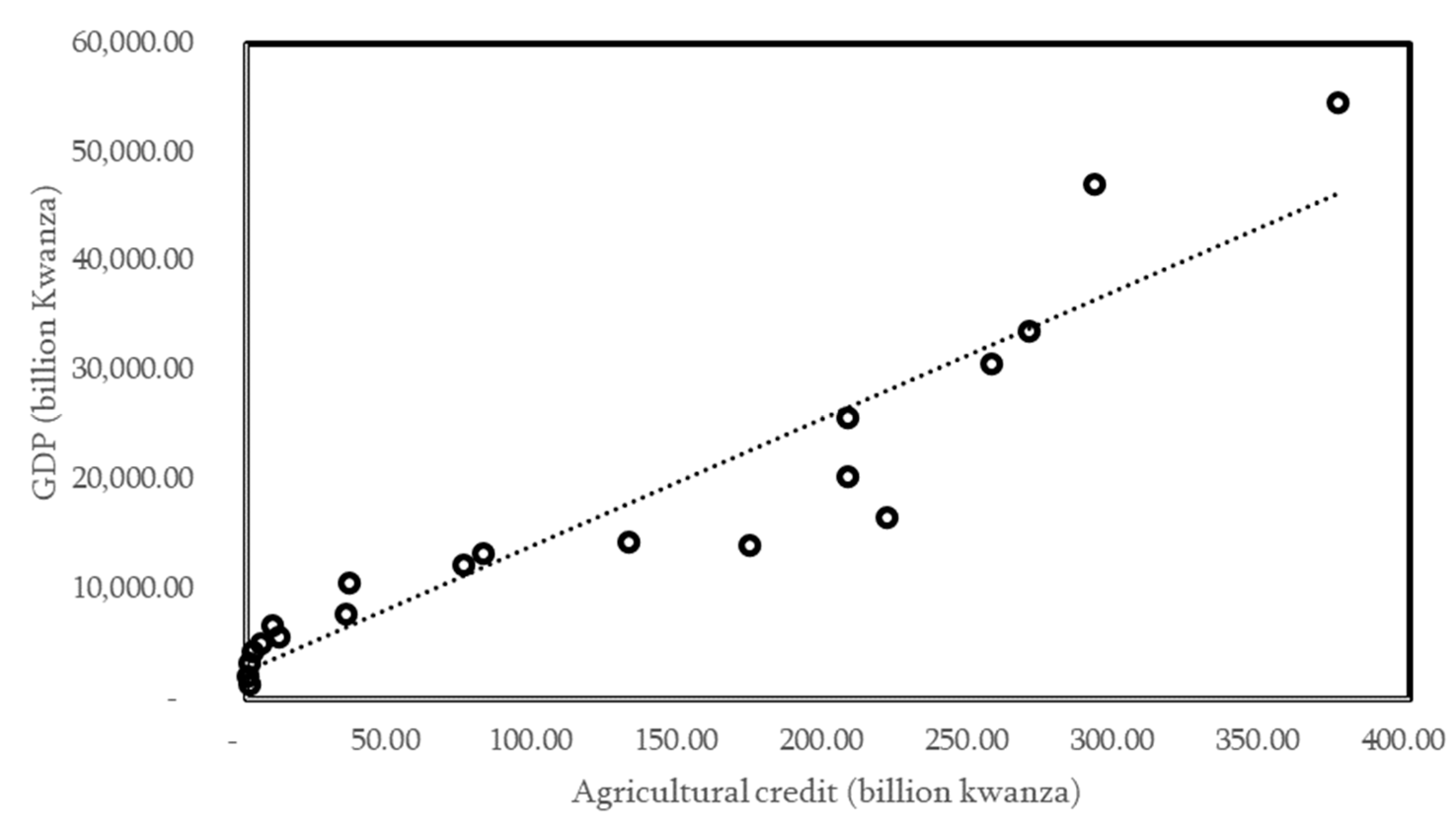

The study is significant as it attempted to identify the impact of credit products provided to Angola’s agricultural sector on the growth of the sector from 2003 to 2022. In the research, preliminary analysis showed that there was a direct relationship between GDP and credit. Therefore, this relationship was examined to obtain quantitative results regarding the importance of agricultural credit to the growth of the agricultural sector in Angola and to provide policy recommendations.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. The second section describes the information on the significance of agricultural sector in Angola‘s economy. The third section provides a review of the important literature and the fourth section the methodology used. The fifth section is reserved for the results and the sixth for the conclusions.

2. Contribution and potential of Agriculture to Angola’s GDP

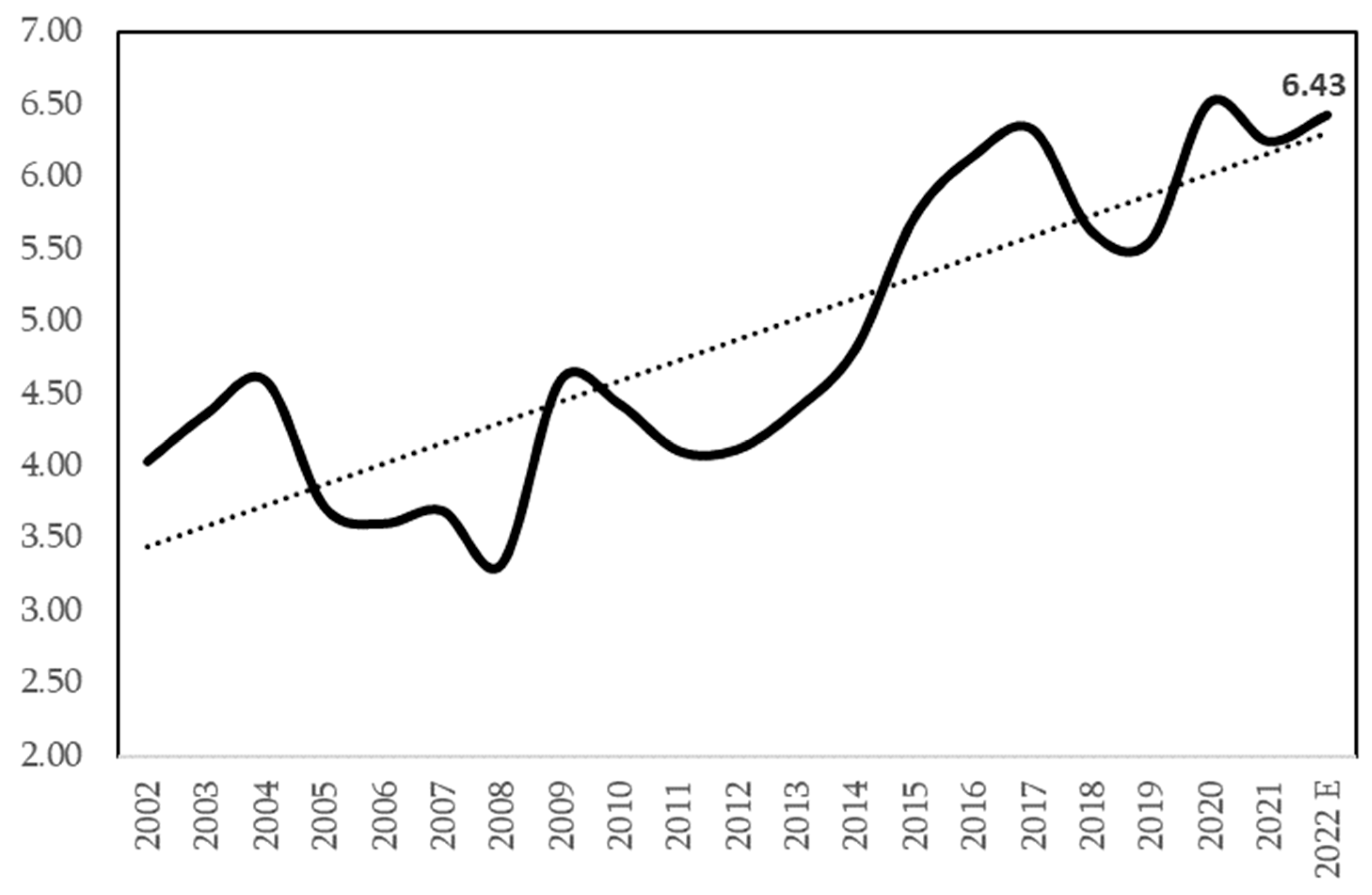

In Angola, the agricultural sector constitutes a limited proportion of the country’s GDP. Nonetheless, agriculture is one of the biggest and fastest growing non-oil sectors of Angola’s economy. Agriculture accounted for 6.5 per cent of Angola’s nominal GDP in 2020 and 6.25 per cent in 2021, and it was estimated to reach 6.43 per cent in 2022.

Agricultural production is currently mostly carried out by smallholder farms, in which approximately three million households (approximately twelve million people, or approximately 30 per cent of Angola’s population) are involved. The Government of Angola has adopted a national program for the development of the agricultural sector in its National Development Plan 2018–2022, which has two principal objectives: (i) the modernization of smallholdings in order for them to become more market-orientated businesses and (ii) the establishment of large and modern industrial farming businesses. Smallholder farms, on which Angola’s agricultural sector is currently based, have much lower production efficiency levels than those in more developed countries.

The credit system in Angola, despite all efforts, remains selective, servicing an exclusive population made up of influential landowners. Further, the system is characterized by high interest rates that involve high-value loans subject to onerous requirements and guarantees, in addition to careful analysis at the time of a loan’s concession.

To strengthen the nation’s value chain, the Government adopted in 2018 the Program to Support Production, Export Diversification and Import Substitution (PRODESI), which contains five key initiatives to enhance the diversification of the Angolan economy, with the aim of significantly decreasing its historical over-reliance on oil export revenue and the import of basic food products.

Having been during its colonial era one of the world’s largest exporters of coffee and other agricultural commodities such as cotton, sisal, maize, cassava and bananas, Angola has today crop and animal production levels far below their potential levels, forcing the country to spend large financial resources on food imports.

The Government has identified several key productive areas that can promote investment and foster public–private partnerships, and it set out further initiatives to boost domestic agricultural production to mitigate the country’s current expenditure on the import of basic food products.

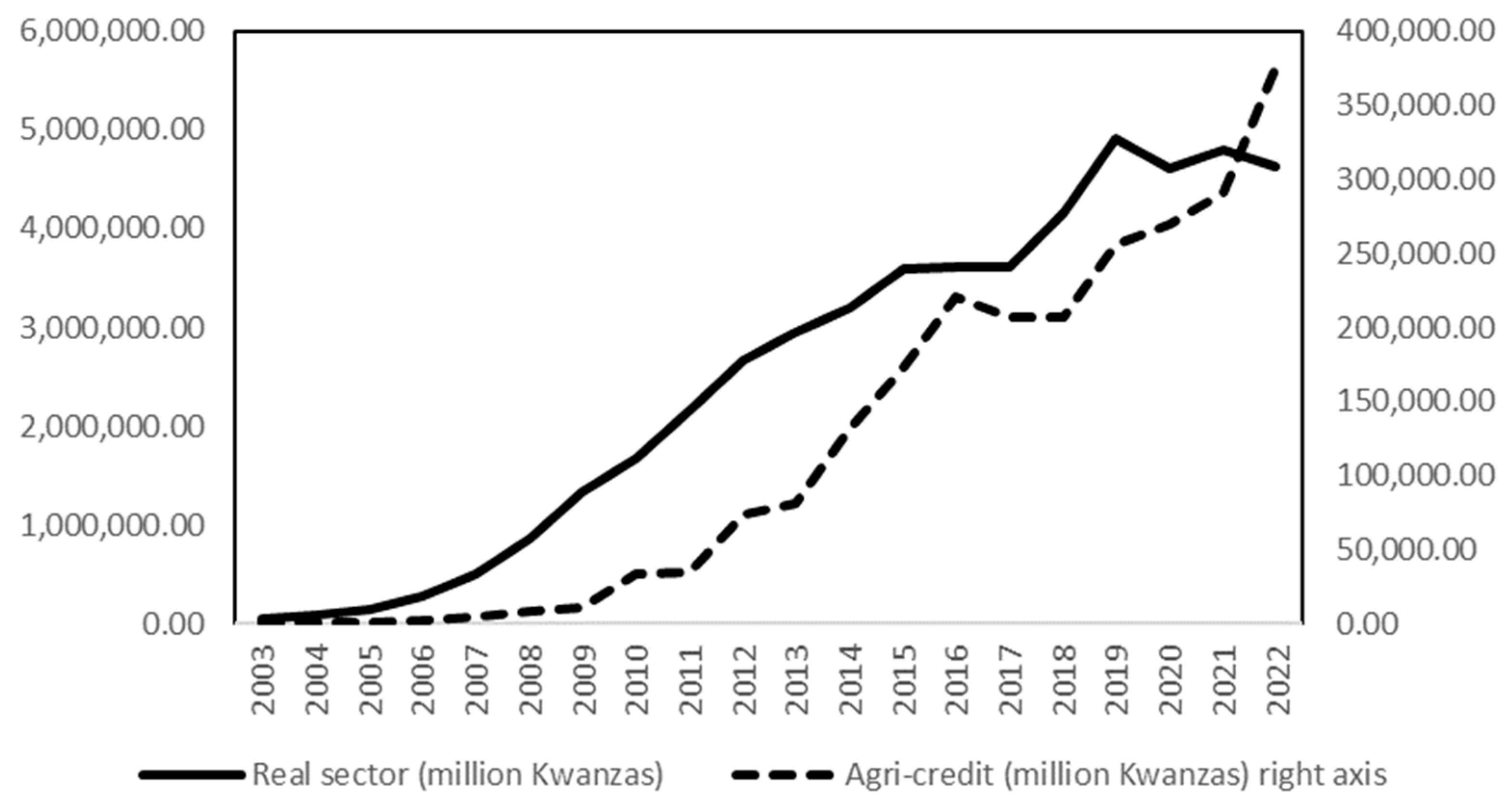

Figure 1 graphs the credit provided to the real economy and the agricultural sector from 2003 and 2022. From 2003 to 2005, there was a linear relation between both economic variables. From 2006 to 2013, less financing flowed to the agricultural sector. From 2014, in large part due to public policies, especially the

Angola Investe Programme, which aimed to re-launch the nation’s agricultural sector, this trend was reversed. This trend was later accelerated by the Government’s clear efforts towards diversifying the country’s economy, with the implementation of the PRODESI in 2018 gathering a strong reaction from the banking and private sectors in 2022.

The agricultural sector is characterized by the randomness of the profitability of its activities and an imbalance in the cash flow of producers, due to the sector’s dependence on the climate, sanitary conditions, the seasonality of crops and the cycle of input and market access conditions. Some of this randomness is measurable risk and could be mitigated via information sharing and insurance policies, but a considerable part of it is uncertainty. There are also uncertainties associated with institutional changes in agricultural policies in competing countries and the high volatility of commodity prices. These problems increase transaction costs.

Nevertheless,

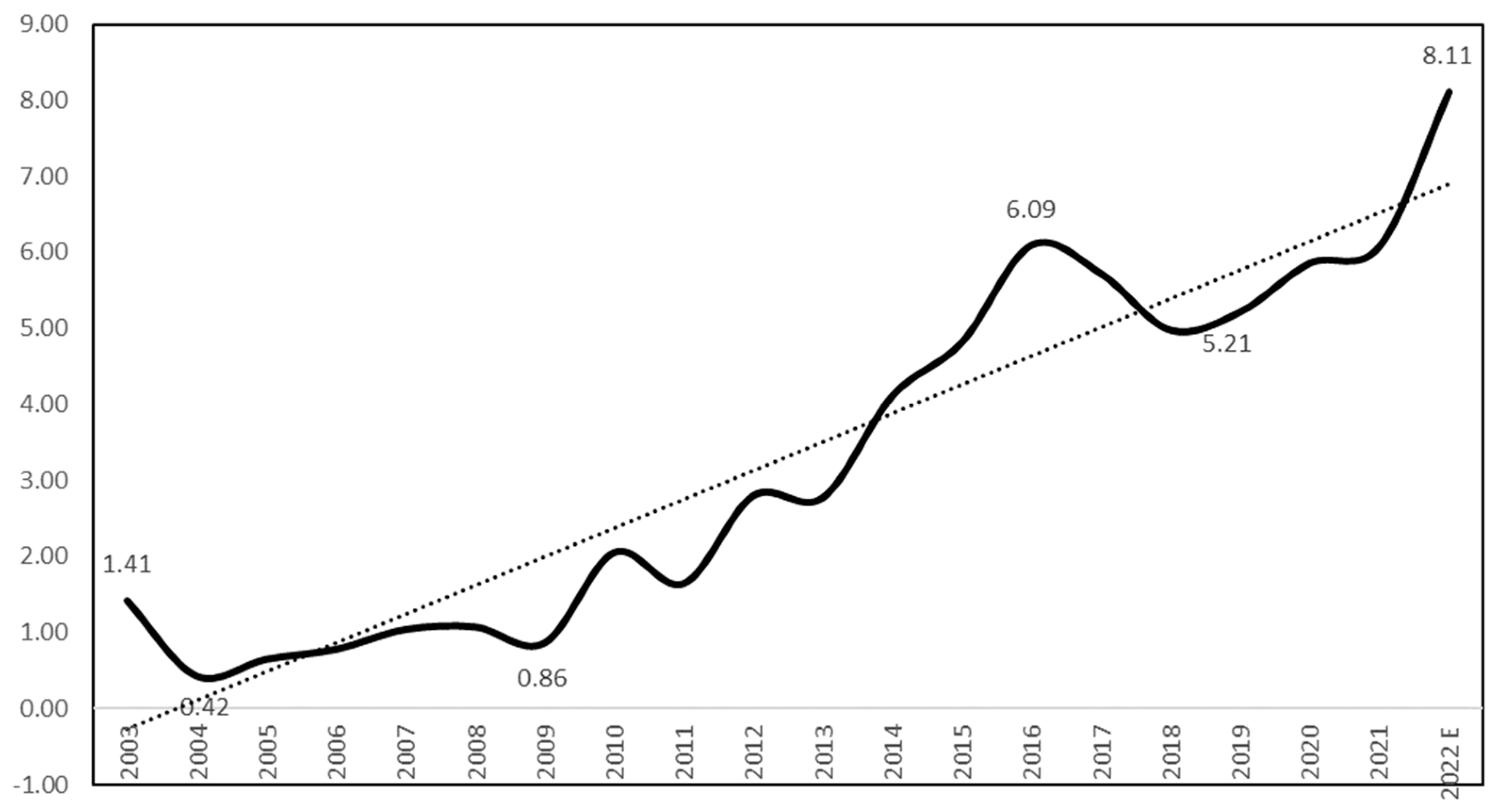

Figure 2 shows that in Angola, during the period from 2010 to 2022, there was a steady increasing trend of credit finance provided to the agricultural sector, representing in 2022 a share of 8.11% of total credit provided to the real sector.

Over the last 20 years, several policies have been implemented by the Government to mitigate risk, ranging from the creation and operationalization of several financial instruments and products at the Angola Development Bank (BDA in Portuguese) since 2006 to the availability of various non-banking financial engineering products, such as venture capital via the Angolan Venture Capital Active Fund (FACRA in Portuguese), and credit guarantees via the Credit Guarantee Fund (FGC in Portuguese). However, the first concrete steps towards commercial banking resources being broadly available to finance the agricultural sector were made possible with the publication of Notices 4 and 7/19, 10/20 and 10/22 of the National Bank of Angola (BNA), which allow the nation’s commercial banks (25 in total) to use the mandatory reserves set by the central bank to grant agri-credit amounting to a minimum of 2.5% of the total value of a lender’s net assets.

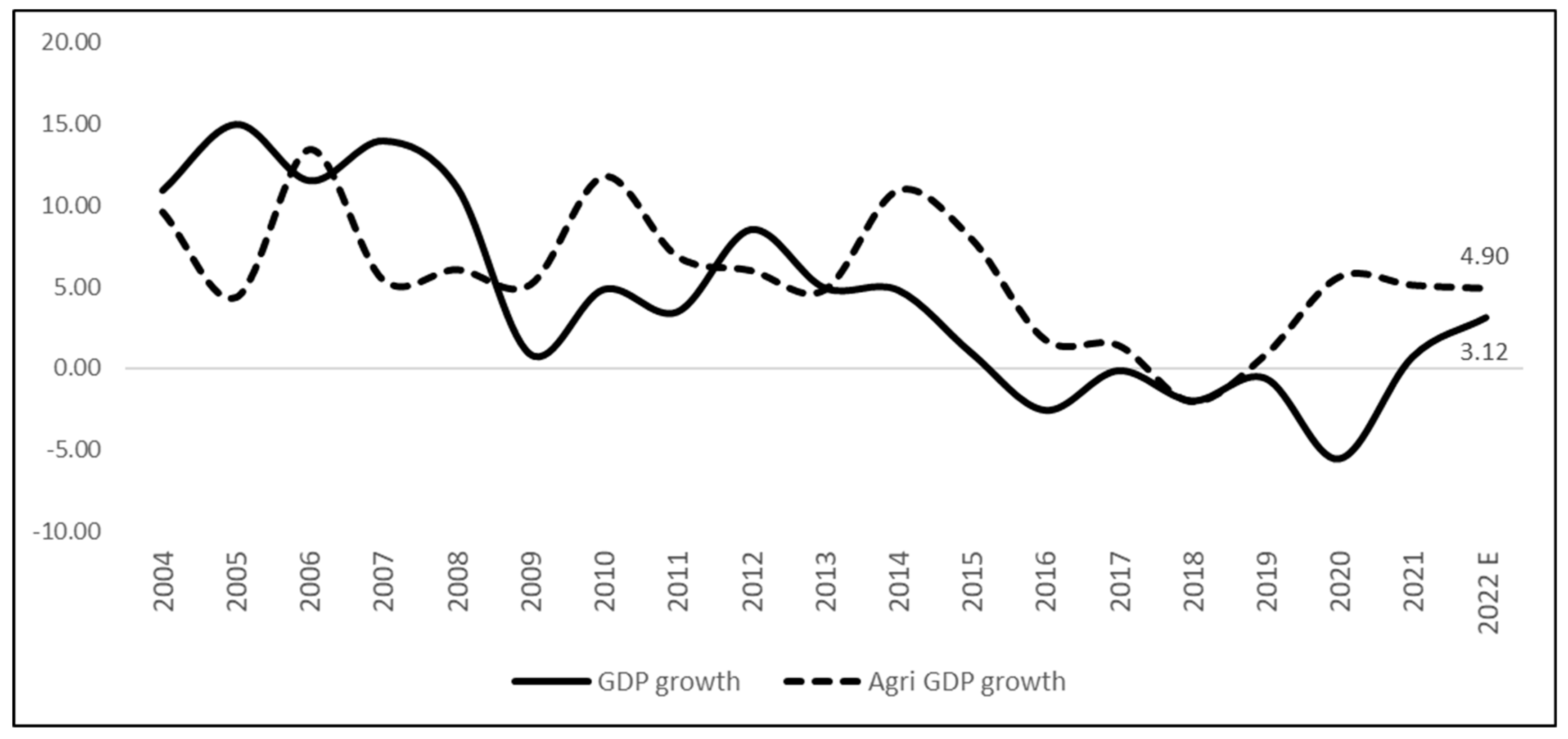

Figure 3 shows that despite some peaks, there was a certain correlation between GDP growth and agricultural GDP growth in the study period, with the agricultural sector being resilient throughout the period and registering stable growth of 5% on average from 2020 to 2022.

Figure 4 shows that, in 2022, the agricultural sector accounted for 6.43% of the total gross domestic product (GDP) of Angola; however, its exports were still very timid, representing less than 1% of the country’s overall food produced.

By 2022, Angola’s commercial banks and the BDA had provided AOA 375.28 billion in credit to the country’s agricultural sector, equivalent to approximately USD 750 million, representing an 82% increase in nominal terms compared to 2018, when the PRODESI was implemented.

3. Literature Review

Many theoretical and empirical studies have analyzed the correlation between financial credit and economic growth. Some have found positive and others have found negative impacts of financial credit on economic growth, but the literature’s general conclusion is that strong financial systems increase credit activity and, subsequently, lead to economic growth.

Empirical studies such as Pistoresi and Venturelli’s (2012) show that countries with strong financial systems could benefit from sustainable economic growth. The authors developed a dynamic panel using a generalized method of moments to examine how venture capital and direct investment impact economic growth.

King and Levine (1993) proposed a model that examines how financial systems can impact economic growth, leading to improved productivity in four ways, namely, (i) refined selection of the best bankable projects; (ii) rationalization of the financial resources used to finance projects; (iii) enabling investors to diversify the risks associated with innovative activities; and (iv) potential compensation provided by financial systems for innovation.

Leitão (2012) proposed an endogenous model that analyzes the correlation between financial credit and economic growth by introducing variables such as domestic credit, savings, bilateral trade and inflation. The findings showed that savings encourage growth, while inflation is negatively correlated with economic growth.

Financing is used in the agricultural sector to support the supply of agricultural inputs and to support the production process, distribution, and marketing of agricultural products. The demand for agricultural finance is very high. Most smallholders and agricultural SMEs find it difficult to access finance and thus engage in agricultural practices that result in dismal agricultural yields (Carroll et al. 2012).

Castro and Teixeira (2004) analyzed the positive impact of interest rate equalization (ETJ) for smallholders and commercial agriculture on GDP growth through increases in the collection of taxes, comparing it with the amount spent on ETJ. Additionally, Castro and Teixeira (2010) measured the elasticity of demand for inputs in relation to rural credit in Brazil and found a very strong elasticity of 0.95 for fertilizers.

The results of Moura’s (2016) study showed that there was a positive effect of agricultural credit on economic growth. Further, Akram et al. (2008) concluded not only that was there a positive effect of agricultural credit on agricultural GDP in Pakistan, but also that there was an elasticity of agricultural credit in relation to poverty of −0.35% and -0.27% in the short term and long term, respectively.

Another important study that employed the VAR methodology was Melo et al.’s (2013), which concluded that an 1.9% increase in credit provided to agriculture generated an impact of 0.79% on agricultural GDP. Likewise, Gasques et al. (2017) found positive impacts of agricultural credit on agricultural GDP, reporting that a positive variation of 1% in agricultural credit generated a positive variation of 0.18% in agricultural GDP.

On the other hand, some authors, such as Robert Lucas (1988) and Nicholas Stern (1989), argue that the financial system–economic growth relationship is not significant. Koivu (2002) analyzed the correlation between economic growth and credit performance in the private sectors of 25 countries in transition from 1993 to 2000 and found that decreases in GDP caused by large amounts of credit were mostly related to counterproductive investments.

FitzGerald (2006) studied institutional structures as important catalyzers of the financial sector’s impacting economic growth, especially via fiscal and monetary policy measures that should provide low and stable real interest rates and competitive exchange rates, as well as appropriate tax incentives.

Notably, all the above authors agreed on the positive impact of agri-credit on the formation of agricultural GDP. With regards to the development of the present study, the work of Borges and Parré (2022) served as a particularly important reference.

4. Methodology

This paper examined the relationship between agricultural credit and agricultural GDP in Angola from 2003 to 2022.

In order to address the research aims or questions, respectively, we use the reduced form of the transmission mechanism of monetary policy in a credit channel with focus on agricultural sector. Moreover, we use the Keynesian assumption about the exogeneity of transmission mechanism. That is, the economic model represents a functional relationship between Angola‘s GDP as dependent variable and agricultural credit as independent variable.

To examine the association between the two variables (agricultural credit and agricultural GDP), the following hypothesis was put forward:

H0 :

agricultural credits have no significant impact on the agricultural GDP in Angola1;

H1 : agricultural credits have a significant impact on the growth of the agricultural GDP in Angola.

For the purpose of this analysis, we used a series of macroeconomic data on GDP from Angola National Statistical Office (INE), and used financial sector data on agricultural credit from Angola National Bank (BNA). The data cover the period 2003 – 2020.

4.1. Econometric Model

The dynamics of the relationship between GDP and agricultural credit is analysed using Autoregressive distributed lag (ADL) model given the agricultural credit exogeneity assumption. That is, the ADL(p,p) can be written as:

where,

is the endogenous variable (GDP);

represents the lagged values of the endogenous variable;

is the exogenous variable included in the model (agricultural credit)

represents the lagged values of the exogenous variable;

α and β are the parameters;

are the error terms of the model.

According to Borges and Parré (2022), it is necessary to verify the degree of stationarity of the series used in the ADL model. The Dickey and Fuller (1981) test is used to determine the level of integration of the series and to consider the possible differences that make the series stationary. …Introduce ADF test here….

Accoriding to Borges and Parré, if the series are stationary with respect to 0 (zero), they will be conducted to the point where they are estimated in equation (1). If the series are integrated into equation (1), the equation uses the variables according to the first difference.

Moreover, we use Granger test to investigate the causality between GDP and agricultural credit. Enders (2015) argues that the Granger test proposes testable definitions between the causality of two time series, based on the assumption that the cause precedes the effect. In this case, the test’s objectivity is restricted in the sense of observing how much of the variable Y is explained by the values of the variable X, that is, determining if the variable X can explain the observed value of Y, meaning that it determines whether the values of X are statistically significant.

To assess the stationarity of the time series in the present study, the augmented ADF test was used; whose purpose is to guide the level of integration between series by measuring the number of differences required for a series to be stationary.

4.1.1. Dickey-Fuller (ADF) Test

For the analysis of the stationarity accuracy of the estimation model, it is common to use the augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test, since it is a single root test that allows identifying econometrically in time series the significant existence of variables with a behavior of stochastic trend through a hypothesis test; having with equation: .

The augmented Dickey-Fuller test suggest three different forms, under three different null hypothesis. For each case, the null hypothesis is , the series have a unit root and nonstationary (Forhad, Rahman, 2021):

- 1)

Yt is Random Walk: ∆Yt = δYt−1 + εt

- 2)

Yt is Random Walk with drift: ∆Yt = β1 + δYt−1 + εt

- 3)

Yt is Random Walk with drift and trend: ∆Yt = β1 + β2t + δYt−1 + εt

4.1.1.1. Dickey-Fuller Test for Unit Root Test

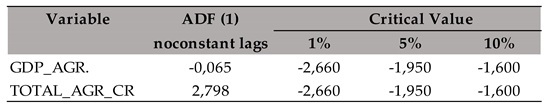

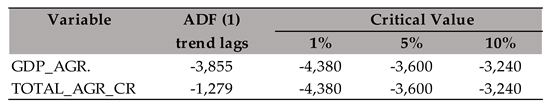

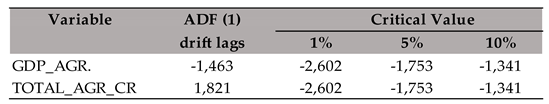

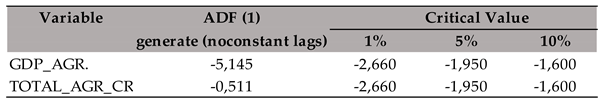

The tables below present the augmented ADF test of the time series. The results of augmented ADF test in first difference show that the TOTAL_AGR_CR series is I(0) stationary at the 5% level of significance. While, GDP_AGR was nonstationary at the same significance level. However, it was possible to make the GDP_AGR series stationary in first difference. Generating the first difference variable and running the unit root test one more tome.

Table 1.

– nonconstant lags (1).

Table 1.

– nonconstant lags (1).

Table 2.

– trend lags (1).

Table 2.

– trend lags (1).

Table 3.

– drift lags (1).

Table 3.

– drift lags (1).

Table 4.

– generate (noconstant lags (1)).

Table 4.

– generate (noconstant lags (1)).

It is common to represent the null hypothesis for Augmented ADF test analysis as follows

2:

H0: Stochastic trends in time series.

H1: Absence of stochastic trends in time series.

According to Noami, (2023), in the Augmented ADF test, the null hypothesis reflects the possibility of nonstationary data, which implies the presence of a unit root in the variables of the estimated model, and alternative hypothesis, the data are stationary. However, the following rule exists: if the t-statistic is greater than critical 5% value, the null hypothesis is rejected. Therefore, the data is stationary. But, if the t-statistic is less than the critical value of 5%, the null hypothesis is accepted. Therefore, the data is nonstationary. In order to correcte the variables (of the model), generate the first difference variables and run the unit root test once more.

4.1.2. Autoregressive Distributed Lag (ADL) Model Estimation

Pereira, Gonçalves (2019), points out that, considering a linear model for time series:

where,

, with L representing the lag operator, that is,

,

, represents the set of explanatory variables of the model,

, is the error term. This the most explicit version of an ADL model, for which the stability condition is assumed to be satisfied, |

| < 1, so there are unit root problems, although they are not very predictable in practice.

The same author says that among the strong points of this model is its generality, that is, because it has a more conservative perspective, in fact the articular cases that come from this model are very extensive, ranging from the static regressions themselves, without dynamics (, until we reach the Error Correction Models (MCE, acronym in Portuguese).

In the view of, Aparício, Azevedo (2018), “the Error Correction Model contains a variety of applicability in economic series given its components that make it a flexible model.” Much on account of being a model capable of incorporating both short-term and long-term mechanisms, as well as the speed of adjustment with which balance is reestablished. In general, the ECM is a particular case of the ADL model, in order to be more concise, an ADL (1,1) model with only a single explanatory variable is expressed, as is the case of present study.

Looking at the previous equation, Aparício describes four characteristics of the ECM:

- a)

It is a short-term dynamic model, since if there are no imbalances, , driven only by ;

- b)

The existing cointegration is incorporated in the model (), and these quantities are specified in the model;

- c)

Therefore, one can estimate the speed with which equilibrium is reestablished through ();

- d)

Finally, the long-term multiplier is expressed by , and, on the other hand, the short-term multiplier is given by , due to the fact that, quantities are specified in the model.

The issue of specification in the ECM model when estimating the regression parameters, that is, the coefficients of the explanatory variables is seen as a problem in the model, knowing that the OLS estimator is BLUE (Best Unbiased Linear Estimator), (Pereira 2019). On the other hand, to guarantee the satisfaction of this and other hypotheses necessary to validate the statistical inference and validity of the final chosen model, several tests are performed, such as

BREUSCH-GODFREY and

DURBIN-WATSON, etc. Therefore, for the present study, we chose to perform the DURBIN-WATSON test

3.

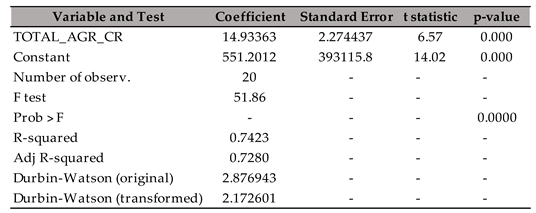

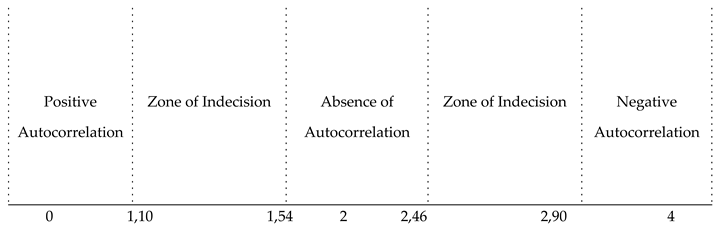

There is an autocorrelation problem in the estimated model, when the errors or residuals of the times series are correlated. Therefore, in order to diagnose autocorrelation problems in the time series studied, the Durbin-Watson (DW) t statistic was used, then analyzing the rule or decision diagram. In order to solve possible problems of autocorrelation in the model series, the PRAIS ESTIMATION was used, and with this, the consistency of the predictability of the estimated econometric model was maintained.

5. Results

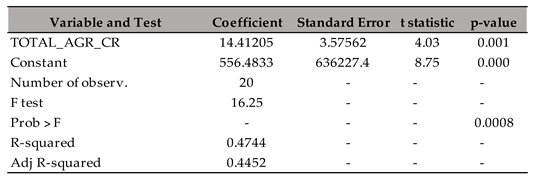

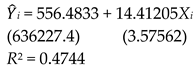

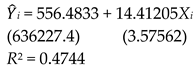

Preliminary analysis using the simple regression model, as shown in

Figure 5, found that there was a direct relationship between GDP and credit provided to agriculture, that is, every monetary unit resulted in an increase in product units.

In terms of presentation,

Figure 5 demonstrates that the simple linear regression econometric model which has the following form:

where the values in parentheses represent the standard deviations of the estimated econometric model parameters.

As shown by the results, a very positive impact of total agricultural credit on the formation of agricultural GDP was found. Further, it was found that 1 monetary unit of kwanza increase in total agricultural credit, ceteris paribus (keeping everything else constant), would result in 14.41205 unites increase in agricultural GDP. However, this approach omits the dynamic relationship between the agricultural GDP and agricultural credit that can be expected highly relevant. That is why we use dynamic model specification in the form of ADL model.

Table 6.

– Estimated Model.

Table 6.

– Estimated Model.

Table 7.

– Prais Estimation (Error Correction of Model).

Table 7.

– Prais Estimation (Error Correction of Model).

Table 8.

– Decision diagram for autocorrelation.

Table 8.

– Decision diagram for autocorrelation.

As can be seen in the result of the DW test and in the decision diagram; the estimator of the time series estimated in the present study presents a test DW = 2.876943, with k = 2 and n = 20, where k, represents the parameters and, n represents the number of observations used in the model. In these case, it is noted that the test DW value is in the indecision zone of the diagram, which does not allow us to make any analysis regarding the existence of autocorrelation between the variables of the estimated model.

Analyzing the values after Prais Estimation. Finally, we can verify that we have the new value for the Durbin-Watson (DW) test = 2.172601, which is now in the zone of absence of autocorrelation between the model variables.

The acceptance or rejection of the null hypothesis of a model largely depends on the choice of the level of significance, that is, on the value of α. Generally, the value of α is set to be 1%, 5% or 10%. For the model estimated in the present study, the level of significance (α) is equal to 5%.

Thus, analysing the values extracted from the results of the estimated econometric model, the null hypothesis was found to be rejected, because the ρ value (P>|t|) of the model parameters was lower than the significance level, which implies that the parameters of the present estimated model were statistically significant.

Further, it was observed that the ρ value (Prob > F) of the F statistic was lower than the significance level, implying that the econometric model estimated in the present study was globally significant.

6. Conclusions

This study attempted to determine the importance of agricultural credit to the overall performance of agricultural production in Angola.

According to the values of the estimated econometric model, a positive relationship was found between agricultural credit and agricultural GDP. In other words, agricultural credit has played a major role in the formation of agricultural GDP in Angola, and above all, in its progressive growth.

Clearly, the government’s current attempts to induce the banking sector to provide more credit to the agricultural sector need to continue and potentially even accelerate, which could be achieved through its making more financial resources available. The government’s implementation of different initiatives that provide negative real interest rates (subsidized interest rates) through banking financial instruments and products via the Angola Development Bank (BDA), or programs with local commercial banks, such as the Angola Investe program (Investing in Angola), BNA Notice 10/2022 and most recently the PAC (Credit Support Project), along with the technical assistance provided by the PRODESI, has brought a significant shift in the country’s agricultural sector’s performance.

Finally, in July 2022, the Government of Angola approved an ambitious and massive grain production plan called PLANAGRÃO (in Portuguese, Plano Nacional de Fomento para a Produção de Grãos). The government will secure an approximately USD 4 billion financial package via the Angola Development Bank aimed at inducing the private sector to produce four priority grains in the time period from 2023 to 2027, namely maize, rice, wheat and soya, with a view to reducing the country’s dependence on food imports and ensuring its self-sufficiency and food security. The agricultural credit used to implement PLANAGRÃO might have a significant impact on the agricultural GDP of the period.

However, ensuring such initiatives are sustainable for their main objective (users) involves a much broader approach and does not end only with their implementation. Continuous monitoring is of the utmost importance to assess if the financial credit granted is really applied to the development of agricultural activities and no other use. Most agricultural agents have expressed enormous concerns about the transparent accessing of credit, as a large number farmers who truly produce and who need it the most to improve their productivity have often been excluded from this process.

In this study, a literature review found that all studies assessed reported a positive impact of agricultural credit on the formation of agricultural GDP. Further, the study found that a variation of about 1% in agricultural credit would result in a positive variation of agricultural GDP of around 14.41%. Therefore, agricultural credit will, in principle, serve to expand the demand for agricultural goods, although this does depend on the expression of agricultural credit in the formation of agricultural GDP.

Finally, the present work provides support for the development of further studies in this area, which should aim to expand on the time series used in this study, as well as examine additional explanatory variables.

7. Limitations

One of the major limitations of this work was that as data for a longer series were not used, there may have been unexplained variability within the data sample; that is, the statistical noise might not have been minimized as much as it could have been. Further, it is worth noting that agricultural products also depend on variables other than agricultural credit, such as infrastructure (especially roads destined for agricultural exploration areas and connecting these with shopping centers), utilities, technical assistance, scientific studies, etc.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: 1; methodology: 2; software 2; validation: 1 and 2; formal analysis: 1; investigation: 1 and 2; resources: 1; data curation: 2; writing—original draft preparation: 1; writing—review and editing: 1 and 2; visualization: 1; supervision: 1; project administration: 1. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

primary data used in this research could be found in the Angola National Accounts published by Angola Statistical Office (

www.ine.gov.ao) and credit data published by Angola National Bank (

www.bna.ao).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 |

The decision to accept or reject H0 largely depends on the significance level (α) or confidence level (1 − α). H0 is accepted when the values of the statistics associated with the parameters demonstrate non-significant differences between what was observed in the sample and the expected results of the model estimation. On the contrary, H0 is rejected when the values of the statistics associated with the parameters demonstrate significant differences between what was observed in the sample and the expected results of the model estimation. |

| 2 |

|

| 3 |

Durbin-Watson’s test (DW, 1950), focuses on the null hypothesis of autocorrelation of the residuals: H0: β0 = 0; H1: β0 ≠ 0 |

References

- (Akram et al. 2008) Akram, Waqar, Zakir Hussain, Hazoor Sabir, and Ijaz Hussain. 2008. Impact of agriculture credit on growth and poverty in Pakistan. European Journal of Scientific Research 23: 243–51.

- (Borges and Parré 2022) Borges, Murilo José, and José Luiz Parré. 2022. O impacto do crédito rural no produto agropecuário brasileiro. Revista de Economia e Sociologia Rural 60: e230521. https://doi.org/10.1590/1806-9479.2021.230521.

- (Carroll et al. 2012) Carroll, Tom, Andrew Stern, Dan Zook, Rocio Funes, Angela Rastegar, and Yuting Lien. 2012. Catalyzing Smallholder Agricultural Finance. New York: Dalberg Global Development Advisors.

- (Castro and Teixeira 2004) Castro, Eduardo Rodrigues, and Erly Cardoso Teixeira. 2004. Retorno dos gastos com a equalização das taxas de juros do crédito rural na economia brasileira. Revista de Política Agrícola 3: 52–57.

- (Castro and Teixeira 2010) Castro, Eduardo Rodrigues, and Erly Cardoso Teixeira. 2010. Crédito rural e oferta agrícola no Brasil. Revista de Política Agrícola XIX: 9–16.

- (Dickey and Fuller 1981) Dickey, David A., and Wayne A. Fuller. 1981. The Likelihood Ratio Statistics for Autoregressive Time Series with a Unit Root. Econometrica 49: 1057–72.

- (Enders 2015) Enders, Walter. 2015. Applied Econometric Time Series, 4th ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- (FitzGerald 2006) FitzGerald, Valpy. 2006. Financial Development and Economic Growth: A Critical View, Background Paper for World Economic and Social Survey. Oxford University. Available online: http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/policy/wess/wess_bg_papers/bp_wess2006_fitzgerald.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2022).

- (Gasques et al. 2017) Gasques, José Garcia, Mirian Rumenos P. Bacchi, and Eliana Teles Bastos. 2017. Impactos do crédito rural sobre as variáveis do agronegócio. Revista de Política Agrícola 26: 132–40.

- (King and Levine 1993) King, Robert G., and Ross Levine. 1993. Finance, entrepreneurship, and growth. Theory and evidence. Journal of Monetary Economics 32: 513–42.

- (Koivu 2002) Koivu, Tuuli. 2002. Do Efficient Banking Sectors Accelerate Economic Growth in Transition Countries? BOFIT Discussion Papers, No. 14/2002. Helsinki: Bank of Finland, Institute for Economies in Transition (BOFIT), pp. 1–29, ISBN 951-686-842-8. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.de/urn:NBN:fi:bof-201408071978 (accessed on 04 April 2022).

- (Leitão 2012) Leitão, Nuno Carlos. 2012. Bank, credit, and economic growth. A dynamic panel analysis. The Economic Research Guardian 2: 256–67. Available online: https://repositorio.ipsantarem.pt/bitstream/10400.15/761/1/NunoLeitao_ERG_2012.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- (Lucas 1988) Lucas, Robert E., Jr. 1988. On the mechanics of economic development. Journal of Monetary Economics 22: 3–42.

- (Melo et al. 2013) Melo, Marcelo Miranda, Émerson Lemos Marinho, and Almir Bittencourt Silva. 2013. O impulso do crédito rural no produto do seto primário brasileiro. Nexos Econômicos 7: 9–35.

- (Moura 2016) Moura, Fábio Rodrigues. 2016. O nexo causal entre crédito rural e crescimento do produto agro-pecuário na economia brasileira. PhD thesis, Escola Superior de Agricultura Luiz Queiroz, Piracicaba, Brazil. Available online: http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/11/11132/tde22062016-163722/en.php (accessed on 03 October 2022).

- (Pistoresi and Venturelli 2012) Pistoresi, Barbara, and Valeria Venturelli. 2012. Credit, Venture Capital and Regional Economic Growth. Journal of Economics and Finance 39: 742–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12197-013-9277-8.

- (Stern 1989) Stern, Nicholas. 1989. The Economics of Development: A Survey. The Economic Journal 99: 597–685.

- (Schumpeter 2021) Schumpeter, Joseph A. 2021, The Theory of Economic Development. London: Routledge.

- (Wheeler and Pélissier 2009) Wheeler, Douglas L., and René Pélissier. 2009. História de Angola. Lisboa: Tinta da China.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

where the values in parentheses represent the standard deviations of the estimated econometric model parameters.

where the values in parentheses represent the standard deviations of the estimated econometric model parameters.