Submitted:

15 August 2023

Posted:

15 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

I- Introduction

The Genus Henipavirus

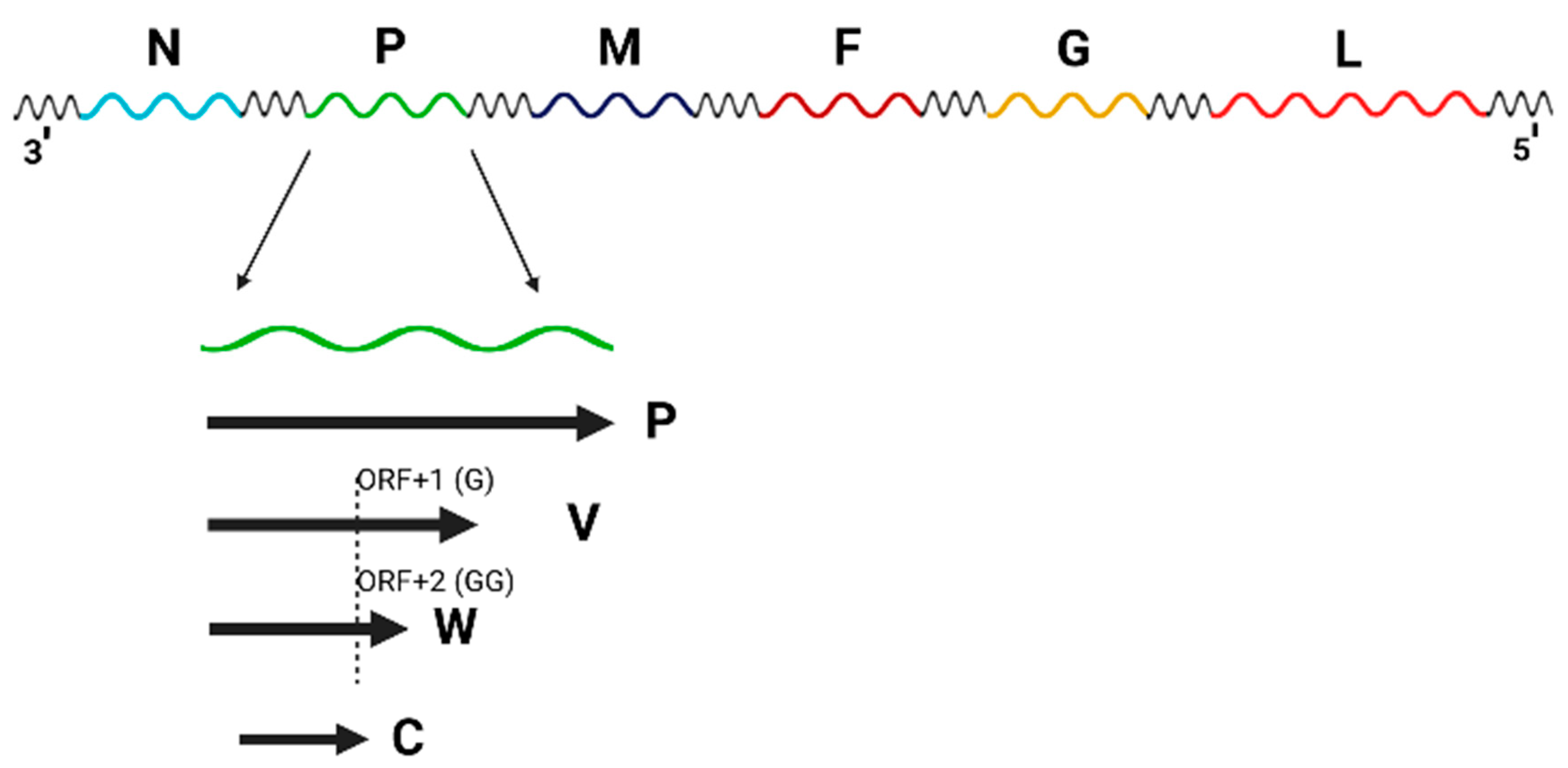

Genomic Structure

Viral Tropism

Currently Well-Characterized Henipaviruses

Other viruses not currently characterized by ICTV as of this submission

II- Experimental Host Tropism

- Hamsters- While humans and horses continue to be the main host targets for HeV, experimental infections have demonstrated that hamsters could also develop respiratory and neurological diseases [24]. Studies by Rockx et al found that a high-dose intranasal infection (i.e. 105 TCID50) could induce infection, with HeV infection being initiated primarily in the interstitium of the lungs. The respiratory epithelium was found to be an early target of infection, while endothelial cells were found to be infected in the later stages of the disease. Interestingly, this same study found that when a lower dose (i.e. 102 TCID50) of HeV was administered intranasally, a slower, more systematic spread of the virus was observed, leading to the development of both respiratory and neurological disease. Furthermore, the presence of virus in both the blood and the central nervous system (CNS) suggested that this mode of infection induces disruption of the blood-brain barrier (BBB). Therefore, these results demonstrated that the clinical outcome of HeV infection in hamsters was dependent on the amount of virus used in the initial challenge dose.

- Non-human primates (NHPs)- The importance of demonstrating the pathogenicity of HeV in NHPs was described by Rockx et al [25] as a model to measure the efficacy of antiviral treatments designed for humans. To this end, Rockx et al infected African green monkeys (AGMs) intratracheally with 4 x 105 TCID50 of HeV, then monitored for clinical signs over a course of 12 days. Of the 12 AGMs tested, 9 were treated with ribavirin either 24 hours prior to challenge, 12 hours post-challenge, or 48 hours post-challenge. While the untreated AGMs required euthanasia between 7.5 and 9.5 dpi, AGMs treated with ribavirin either 24 hours prior or 12 hours post-infection required euthanasia within 10 and 10.5 dpi, a statistically significant delay of the onset of disease. Clinical signs included nasal discharge, labored breathing, and seizures. Pathology was also observed in the lungs, with pulmonary consolidation being seen in infected animals via radiology. Histological analysis also showed HeV tropism in the lung and brain; and viral replication was detected in the lungs, brain, liver, spleen, kidney, pancreas, lymph nodes, tonsils, and gastrointestinal organs [25]. A subsequent study by Bossart et al using this same AGM model also found that a monoclonal antibody (m102.4), when administered within 72 hours of HeV infection, could protect the animals from death [26].

- Guinea pigs- The susceptibility of guinea pigs to HeV was demonstrated by Hooper et al, when HeV (then referred to as Equine Morbillivirus or EV) was inoculated subcutaneously using 5 x 103 TCID50 [27]. Four out of the 5 animals inoculated either died or became severely ill. Subsequent histological analysis demonstrated the virus in the lungs, heart, kidneys, liver, brain, and GI tract [27]. Further studies using guinea pigs were described by Williamson et al [28] where pregnant guinea pigs (at 31-41 days gestation) were inoculated subcutaneously with HeV. Of the 18 animals inoculated, 7 animals died within 7 days of inoculation, with 8 more animals having to be euthanized before 15 dpi. Histological analysis determined that the virus was present in the lungs, kidney, brain, spleen, blood, placenta/uterus, and fetal tissue [29].

- Pigs- Although NiV has been extensively associated with pigs, little work has been performed to determine whether swine are also susceptible to the closely related HeV. Experimental infections in both 5-week-old Landrace pigs and 5-month-old Gottingen minipigs found that, after oronasal inoculation, both types of pigs developed respiratory signs at 5 dpi, with the minipigs developing neurological signs at 7 dpi [30]. Histological studies of the infected pigs confirmed the presence of the virus in the lymph nodes, tonsils, lung, and nasal turbinates. Furthermore, as HeV could also be detected in the olfactory bulbs, this finding suggested that HeV could invade the central nervous system via the olfactory nerves.

- Fruit bats- While the initial outbreak of HeV was identified in humans and horses, serological studies in the areas surrounding the original outbreak in Queensland showed that fruit bats had antibodies that recognized the virus [31]. As other serological studies in the Queensland area found that fruit bats had antibodies against HeV, it was hypothesized that these animals could serve as a reservoir species. Therefore, studies were then conducted to determine if experimental subcutaneous or oronasal inoculation of fruit bats could induce clinical disease [32]. Of the eight bats inoculated, six seroconverted, although none developed significant clinical signs (with only two bats showing vascular lesions), suggesting that bats are resistant to HeV-induced disease. Another subsequent study by Williamson et al also confirmed that no overt clinical disease could be observed in HeV inoculated fruit bats [29,33].

- Cats- Shortly after the initial characterization of HeV in humans and horses, the susceptibility of cats to HeV was studied by Westbury et al [34]. It was found that all cats inoculated either intranasally, subcutaneously, or orally developed HeV disease within 4-8 days, with death (or euthanasia being required) within 6-9 days. HeV was isolated from a variety of organs, including lung, trachea, brain, spleen, kidney, and lymph node [34]. This same study also demonstrated that infected cats could transmit the virus through contact to uninfected cats.

- Ferrets- As ferrets were previously found to be susceptible to NiV infection, HeV was also assayed in ferrets in a study by Pallister et al, where a recombinantly expressed HeV glycoprotein was assayed for its ability to confer protection [35]. In that study, ferrets were inoculated oronasally with different doses of HeV. In all animals, clinical signs were observed starting at 6 dpi, with all animals being euthanized by 9 dpi. Clinical signs included fever, depression, lack of grooming, and tremors. Histological analysis found the presence of HeV antigen in meningeal endothelial cells, bronchoalveolar endothelial cells, as well as cardiac, renal, splenic, pancreatic, and intestinal cells [35].

- Hamsters- As hamsters were already found to be susceptible to HeV infection, their susceptibility to infection by the related NiV was assessed by Wong et al [36]. In this study, Syrian golden hamsters were initially evaluated for the ability to develop disease following either intranasal or intraperitoneal inoculation with 107 infectious viral particles. All hamsters died within 5-8 dpi [36]. In the next study, hamsters were inoculated with a lower dose (i.e. 104 pfu) intranasally, and most animals succumbed to disease at 9-15 dpi, with clinical signs including imbalance, limb paralysis, limb twitching, and breathing difficulties. Reverse-transcription PCR (RT-PCR) performed following autopsy showed the presence of NiV in the brain, spinal cord, lung, kidney, spleen liver, and heart. Vascular pathology was also observed in these organs, with histological samples of the affected organs showing necrosis, inflammation, and multinucleation/syncytium formation. As these results are consistent with the pathology observed following human infection, it was proposed that hamsters were a suitable model for the study of NiV pathology.

- Non-human primates (NHPs)- As in the case of HeV, the development of a non-human primate model for NiV was important, as NiV has been shown to be fatal in humans; and any validation of a vaccine or antiviral treatment against NiV in humans would ultimately have to be validated in NHPs. Such a model was described by Marianneau et al [37] when squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus) were inoculated either intravenously or intranasally with either 103 or 107 pfu. Clinical signs were observed between 7 and 19 dpi, which included: anorexia, weight loss, hyperthermia, acute respiratory syndrome, and uncoordinated motor movements, with some animals experiencing a loss of consciousness and coma [37]. Monkeys inoculated intravenously had more severe clinical signs, and required euthanasia earlier than those inoculated intranasally. While most intravenously inoculated monkeys displayed IgM- and IgG specific titers against NiV, most animals (of any experimental group) did not develop neutralizing antibody titers. Viral RNA was detectable in the liver, brain, kidney, lung, and lymph nodes. Histological examination also found the presence of virus in the lungs (alveolar walls), kidneys and brain. Another NHP model was described by Geisbert et al [38], where AGMs were inoculated either intratracheally or intratracheally/orally, with NiV ranging from 2.5 x 103 to 1.3 x 106 pfu. All the AGMs tested displayed clinical signs, including depression, lethargy, open-mouthed breathing, loss of appetite, and loss of balance. All but one animal died (or required euthanization) by day 12 post-infection. Pathology associated with infection included: thrombocytopenia, severely inflated lungs, hemorrhages on the mucosal surface of the bladder, and excess blood-tinged pleural fluid. Presence of the virus was found in the spleen, lungs, and bladder [38]. Other studies using AGMs found that when the virus was administered intranasally using a laryngeal mask airway (LMA) mucosal atomization device (MAD), 2 x 103 or 2x 104 pfu of NiV was sufficient to induce severe disease. All 4 monkeys tested required euthanasia by day 10 post-infection [39]. Finally, an interspecies comparison between AGMs and macaque monkeys found that macaques were more likely to survive NiV infection than AGMs [40]. All macaques that were inoculated both intratracheally and intranasally with 5 x 105 pfu of NiV survived infection until the end of the study (which contrasted with AGMs, which usually succumb to infection within 5-7 dpi). Furthermore, all macaques seroconverted and generated neutralizing antibody titers comparable to AGMs. This same study also found a correlation between surviving animals and T-helper cell profiles that skewed towards the Th1 subtype [40]. Other non-human primates, such as marmosets, were also found to be susceptible to NiV infection. Studies by Stevens et al [41] demonstrated that these animals can also serve as an animal model for viral studies. When 6.3 x 104 pfu of NiV was administered intratracheally and intranasally, all 4 inoculated marmosets developed clinical signs, and required euthanasia between 8 and 11 dpi [41]. Pulmonary edema and viral hepatitis were observed post-mortem, with syncytial formation being observed in the pulmonary tissue. Histopathological analysis also found the presence of viral antigen in pulmonary and cardiac tissue [41].

- Guinea pigs- Although Wong et al did not observe NiV pathology in guinea pigs [36], other studies did observe some clinical signs following infection. Middleton et al inoculated 8 guinea pigs with 5 x 104 TCID50 intraperitoneally, with 3 out of 8 animals displaying abnormal behavior and ataxia between 7 and 8 dpi [42]. Following euthanasia, NiV was isolated from the heart, lung, uterus, spleen and blood of the infected animals. Another study by Torres-Velez et al found an even greater incidence of NiV pathology in guinea pigs, with nearly all animals succumbing to infection between 4 and 8 dpi after intraperitoneal inoculation with 6 x 104 pfu of virus [43]. Viral antigen was detected over a wide variety of tissues and cell types, with syncytial formation also being observed.

- Pigs- As the original outbreak of NiV was linked to pig farms and pig trade, a more extensive study of the pathology and transmission of the virus to pigs was required. Experimental infection of NiV in 6-week-old piglets was performed by Middleton et al [44], where 3 pigs were inoculated orally, while another 3 were inoculated subcutaneously with 5 x 104 TCID50 of NiV (virus that had not been passaged in cell culture). The remaining 2 piglets were not inoculated with the virus, but remained in direct contact with the other pigs. Over the course of 21 days, all animals were analyzed for pathology, clinical signs, as well as the presence of virus in different samples taken. Of the 4 pigs inoculated subcutaneously, 2 required euthanasia between 7 and 8 dpi, due to severe clinical disease with ataxia, semi-consciousness and lack of coordinated movements. However, while another pig also showed some clinical signs, it was able to recover. Interestingly, all of the orally infected pigs showed little to no clinical signs and survived the entire 21-day study [44]. Organs recovered from the animals showed that NiV could be recovered from tonsil, nose, blood, lung and spleen. Pathological analysis showed vasculitis and degeneration of pulmonary blood vessels, with syncytial cell formation observed within lymphoendothelial cells. Although the contact animals did not show significant clinical signs, the virus was recovered from their tonsil and nose. Seroconversion was observed in both groups, with neutralizing antibodies detected between 14 and 21 dpi. Another study by Weingartl et al [45] using 5-week-old piglets found similar results when using the oronasal inoculation route, as most pigs were clinically healthy throughout the study, with only 2 (out of 11 pigs) requiring euthanasia due to severe clinical signs. As in the previous study, the presence of the virus was detected in both healthy and diseased pigs; however, their findings also demonstrated that NiV replication occurred in the CNS prior to infection of the endothelial cells of the blood/lymphatic system. Their results represented the first demonstration that NiV could cross the BBB of pigs. The conditions used in this experimental setup were then used for subsequent studies of possible immunosuppression of the infected pigs leading to spread of bacteria [46], as well as the evaluation of multiple vaccine candidates [47,48].

- Cats- Following the initial outbreak of NiV in Malaysia in the late 1990s, it was suspected that the virus could infect companion animals such as dogs and cats [46]. The experimental infection of cats was demonstrated by Middleton et al [44], where 2 cats were inoculated oronasally with 5 x 104 TCID50 of virus. Clinical signs and rectal temperatures were assessed daily for 21 days. While both cats appeared normal for the first 4 days, both cats developed fever by day 6, with the animals showing signs of depression and increased respiratory rates [44]. Febrile illness, depression and breathing difficulties continued until one of the two cats required euthanasia at 9 dpi, while the other cat recovered. Virus was isolated from the blood, tonsil and urine. Another study performed by Mungall et al [49] showed that clinical signs could be observed when NiV was administered subcutaneously at either dose of 5x102 or 5x103 TCID50. Both experimental groups demonstrated febrile illness until being euthanized at 9 dpi. Upon necroscopy, the cats were found to have hemorrhagic nodular lesions on the visceral pleura. Histological analysis found NiV-positive hemorrhagic and necrotic lesions of pulmonary tissue, including syncytial formation [47]. These experimental conditions served as the basis for the validation of a NiV subunit vaccine, encoding for the soluble G protein of HeV [49,50]. In one study, following subcutaneous administration of 5x102 TCID50 of virus, a cat was found to be pregnant during necropsy [51]. Postmortem samples of placenta and fetal tissues tested positive for the virus, and virus could be re-isolated from the placenta [51], thereby demonstrating the ability of NiV to be vertically transmitted.

- Bats- As bats were suspected of acting as a reservoir species from the earliest outbreak for NiV [52], the susceptibility of native Australian flying foxes (Pteropus poliocephalus) was evaluated by Middleton et al [42], where 17 grey-headed flying foxes were inoculated subcutaneously with 5 x 104 TCID50 of NiV and monitored for 21 days, with body temperature and bodyweight being measured daily. Serum samples were also collected at various time points. The infected bats presented subclinical infection characteristics, as evidenced by the presence of viral antigen in selected viscera and seroconversion. Although the virus was not recovered from the wide variety of organs seen in other animal models, NiV was recovered from the kidney of one male bat, as well as the uterus of one female bat [42]. Furthermore, NiV was isolated from the urine of one animal. Pathology studies did not display any gross abnormalities. All tissue samples tested negative for NiV through immunohistochemical labelling.

- Ferrets- As in the case of HeV, ferrets were also found to be susceptible to NiV. A ferret animal model for NiV infection was described by Bossart et al [26], where a human monoclonal antibody m102.4 was assessed for its ability to protect against lethal disease caused by NiV. In this model, ferrets were inoculated oronasally with titers varying from 5 x 101 TCID50 to 5 x 104 TCID50. While clinical signs were observed in at least one animal inoculated with 5 x 102 TCID50, viral shedding and disease were consistently observed at 5 x 103 and 5 x 104 TCID50. Clinical signs were found to be consistent to those found in humans, including loss of appetite, depression, dyspnea and neurological disease and generalized vasculitis (including syncytia formation of the epithelium) [26]. The presence of NiV antigen was detected in a variety of organs, including the pharynx, blood, kidney, liver, rectum, spleen and brain. The ferret model was used to validate vaccine candidates such as recombinant HeV G [53], as well as recombinant vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) expressing either the F- or G-proteins of NiV [54].

- Guinea pigs- Using CedV that was originally isolated from the urine of flying foxes, followed by two serial passages in bat PaKi cells, 2 x 106 TCID50 of CedV was inoculated intraperitoneally in guinea pigs [15]. Although no clinical signs were observed over 21 days, virus-specific antibodies were generated, as neutralizing antibodies were detected in 2 out of the 4 guinea pigs tested.

- Hamsters- CedV was also found to experimentally infect hamsters. Schountz et al [55] demonstrated that virus replication could be observed following intranasal inoculation of the virus (105 TCID50), with replication occurring in the lungs and spleen of the animal.

- Mice- In the same study by Marsh et al [15], BALB/c mice were also inoculated oronasally with 1 x 105 TCID50 of CedV and monitored for 21 days. None of the mice displayed any clinical signs, nor were any neutralizing antibodies detected.

- Ferrets- In the study previously discussed [15], ferrets were also inoculated oronasally with 2 x 106 TCID50 of CedV and monitored for 21 days. Although no clinical signs were observed, neutralizing antibodies were detected by 10 dpi. However, hyperplasia of tonsillar and bronchial lymphoid tissues was observed, with virus being detected in the bronchial lymph nodes [15].

III- Tissue/Organ Tropism

IV- Cellular Tropism

EphrinB2 and –B3 Are Host Receptors for NiV and HeV

V-Conclusion

| Virus | Organisms | Organ/Tissues | Cells |

| Hendra (HeV) | -Natural hosts: horses, humans, bats -Experimental: hamsters, guinea pigs, cats, ferrets, pigs, non-human primates |

-lung, kidney, liver, placenta, lymph nodes, vascular endothelium | -primary epithelial cells -cell lines : HeLa, 293T, 3T3, BSC-1, HuTK-143B, Vero |

| Nipah (NiV) | -Natural hosts: pigs, humans, bats -Experimental: hamsters, guinea pigs, cats, pigs, non-human primates, ferrets |

-lung, brain, liver, arteries, bronchiolar respiratory epithelium, nasal turbinates, kidneys | -primary: epithelial cells (artery), macrophages, endothelial cells, neurons -cell lines: HeLa, 293T, CHO, U87, U373, PCI-13, Vero |

| Cedar (CedV) | -Natural hosts: bats -Experimental: guinea pig, mice, ferrets, hamster |

-lungs, spleen, also isolated from urine | -cell lines: PaKi, A549, HEK293T, Vero, BHK21, L2, C6, Rat2 cells |

| Ghana (Kumasi/M74 virus) | -Natural hosts: bats | NA | -cell lines: HypNi/1.1, EidNi |

| Mojiang (MojV) | -Natural hosts: humans, rats | NA | -cell lines: A549, U87, BHK21, HEK293T, Vero, Hep2 |

| Langya (LayV) | -Natural hosts: humans, shrews, voles | -NA | -cell lines: Vero |

| Angavokely (AngV) | -Natural hosts: bats | -unclear (isolated from urine) | NA |

| Gamak (GAKV) | -Natural hosts: shrews | -kidney | -cell line: Vero E6 |

| Daeryong (DARV) | -Natural hosts: shrews | -kidney | NA |

| Denwin (DewV) | -Natural hosts: shrews | -kidney | NA |

| Melian (MeliV_ | -Natural hosts: shrews | -kidney | NA |

References

- Murray, K.; Rogers, R.; Selvey, L.; Selleck, P.; Hyatt, A.; Gould, A.; Gleeson, L.; Hooper, P.; Westbury, H. A Novel Morbillivirus Pneumonia of Horses and Its Transmission to Humans. Emerg Infect Dis 1995, 1, 31–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvey, L.A.; Wells, R.M.; McCormack, J.G.; Ansford, A.J.; Murray, K.; Rogers, R.J.; Lavercombe, P.S.; Selleck, P.; Sheridan, J.W. Infection of Humans and Horses by a Newly Described Morbillivirus. Med J Aust 1995, 162, 642–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvey, L.; Sheridan, J. Outbreak of Severe Respiratory Disease in Humans and Horses Due to a Previously Unrecognized Paramyxovirus. J Travel Med 1995, 2, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harcourt, B.H.; Tamin, A.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Rollin, P.E.; Anderson, L.J.; Bellini, W.J.; Rota, P.A. Molecular Characterization of Nipah Virus, a Newly Emergent Paramyxovirus. Virology 2000, 271, 334–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, A.; Yun, T.; Vigant, F.; Pernet, O.; Won, S.T.; Dawes, B.E.; Bartkowski, W.; Freiberg, A.N.; Lee, B. Nipah Virus C Protein Recruits Tsg101 to Promote the Efficient Release of Virus in an ESCRT-Dependent Pathway. PLoS Pathog 2016, 12, e1005659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horie, R.; Yoneda, M.; Uchida, S.; Sato, H.; Kai, C. Region of Nipah Virus C Protein Responsible for Shuttling between the Cytoplasm and Nucleus. Virology 2016, 497, 294–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.-S.; Shaw, M.L.; Muñoz-Jordan, J.; Cros, J.F.; Nakaya, T.; Bouvier, N.; Palese, P.; García-Sastre, A.; Basler, C.F. Newcastle Disease Virus (NDV)-Based Assay Demonstrates Interferon-Antagonist Activity for the NDV V Protein and the Nipah Virus V, W, and C Proteins. J Virol 2003, 77, 1501–1511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, M.L.; García-Sastre, A.; Palese, P.; Basler, C.F. Nipah Virus V and W Proteins Have a Common STAT1-Binding Domain yet Inhibit STAT1 Activation from the Cytoplasmic and Nuclear Compartments, Respectively. J Virol 2004, 78, 5633–5641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rota, P.A.; Lo, M.K. Molecular Virology of the Henipaviruses. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2012, 359, 41–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, G.D.; Lee, B. Paramyxoviruses from Bats: Changes in Receptor Specificity and Their Role in Host Adaptation. Curr Opin Virol 2023, 58, 101292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar, H.C.; Iorio, R.M. Henipavirus Membrane Fusion and Viral Entry. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2012, 359, 79–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pernet, O.; Wang, Y.E.; Lee, B. Henipavirus Receptor Usage and Tropism. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2012, 359, 59–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, K.B.; Goh, K.J.; Wong, K.T.; Kamarulzaman, A.; Tan, P.S.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Zaki, S.R.; Paul, G.; Lam, S.K.; Tan, C.T. Fatal Encephalitis Due to Nipah Virus among Pig-Farmers in Malaysia. Lancet 1999, 354, 1257–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update: Outbreak of Nipah Virus--Malaysia and Singapore. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 1999, 48.

- Marsh, G.A.; de Jong, C.; Barr, J.A.; Tachedjian, M.; Smith, C.; Middleton, D.; Yu, M.; Todd, S.; Foord, A.J.; Haring, V.; et al. Cedar Virus: A Novel Henipavirus Isolated from Australian Bats. PLoS Pathog 2012, 8, e1002836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Yang, L.; Yang, F.; Ren, X.; Jiang, J.; Dong, J.; Sun, L.; Zhu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Jin, Q. Novel Henipa-like Virus, Mojiang Paramyxovirus, in Rats, China, 2012. Emerg Infect Dis 2014, 20, 1064–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drexler, J.F.; Corman, V.M.; Gloza-Rausch, F.; Seebens, A.; Annan, A.; Ipsen, A.; Kruppa, T.; Müller, M.A.; Kalko, E.K. V; Adu-Sarkodie, Y.; et al. Henipavirus RNA in African Bats. PLoS One 2009, 4, e6367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.-A.; Li, H.; Jiang, F.-C.; Zhu, F.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Chen, J.-J.; Tan, C.-W.; Anderson, D.E.; Fan, H.; Dong, L.-Y.; et al. A Zoonotic Henipavirus in Febrile Patients in China. N Engl J Med 2022, 387, 470–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madera, S.; Kistler, A.; Ranaivoson, H.C.; Ahyong, V.; Andrianiaina, A.; Andry, S.; Raharinosy, V.; Randriambolamanantsoa, T.H.; Ravelomanantsoa, N.A.F.; Tato, C.M.; et al. Discovery and Genomic Characterization of a Novel Henipavirus, Angavokely Virus, from Fruit Bats in Madagascar. J Virol 2022, 96, e0092122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Kim, K.; Kim, J.; No, J.S.; Park, K.; Budhathoki, S.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, J.; Cho, S.H.; Cho, S.; et al. Discovery and Genetic Characterization of Novel Paramyxoviruses Related to the Genus Henipavirus in Crocidura Species in the Republic of Korea. Viruses 2021, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanmechelen, B.; Meurs, S.; Horemans, M.; Loosen, A.; Joly Maes, T.; Laenen, L.; Vergote, V.; Koundouno, F.R.; Magassouba, N.; Konde, M.K.; et al. The Characterization of Multiple Novel Paramyxoviruses Highlights the Diverse Nature of the Subfamily Orthoparamyxovirinae. Virus Evol 2022, 8, veac061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westbury, H.A. Hendra Virus Disease in Horses. Rev Sci Tech 2000, 19, 151–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Westbury, H. Hendra Virus: A Highly Lethal Zoonotic Agent. Vet J 2000, 160, 165–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rockx, B.; Brining, D.; Kramer, J.; Callison, J.; Ebihara, H.; Mansfield, K.; Feldmann, H. Clinical Outcome of Henipavirus Infection in Hamsters Is Determined by the Route and Dose of Infection. J Virol 2011, 85, 7658–7671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockx, B.; Bossart, K.N.; Feldmann, F.; Geisbert, J.B.; Hickey, A.C.; Brining, D.; Callison, J.; Safronetz, D.; Marzi, A.; Kercher, L.; et al. A Novel Model of Lethal Hendra Virus Infection in African Green Monkeys and the Effectiveness of Ribavirin Treatment. J Virol 2010, 84, 9831–9839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossart, K.N.; Geisbert, T.W.; Feldmann, H.; Zhu, Z.; Feldmann, F.; Geisbert, J.B.; Yan, L.; Feng, Y.-R.; Brining, D.; Scott, D.; et al. A Neutralizing Human Monoclonal Antibody Protects African Green Monkeys from Hendra Virus Challenge. Sci Transl Med 2011, 3, 105ra103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, P.T.; Westbury, H.A.; Russell, G.M. The Lesions of Experimental Equine Morbillivirus Disease in Cats and Guinea Pigs. Vet Pathol 1997, 34, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, M.M.; Hooper, P.T.; Selleck, P.W.; Westbury, H.A.; Slocombe, R.F. A Guinea-Pig Model of Hendra Virus Encephalitis. J Comp Pathol 2001, 124, 273–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, M.M.; Hooper, P.T.; Selleck, P.W.; Westbury, H.A.; Slocombe, R.F. Experimental Hendra Virus Infectionin Pregnant Guinea-Pigs and Fruit Bats (Pteropus Poliocephalus). J Comp Pathol 2000, 122, 201–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Embury-Hyatt, C.; Weingartl, H.M. Experimental Inoculation Study Indicates Swine as a Potential Host for Hendra Virus. Vet Res 2010, 41, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, P.L.; Halpin, K.; Selleck, P.W.; Field, H.; Gravel, J.L.; Kelly, M.A.; Mackenzie, J.S. Serologic Evidence for the Presence in Pteropus Bats of a Paramyxovirus Related to Equine Morbillivirus. Emerg Infect Dis 1996, 2, 239–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williamson, M.M.; Hooper, P.T.; Selleck, P.W.; Gleeson, L.J.; Daniels, P.W.; Westbury, H.A.; Murray, P.K. Transmission Studies of Hendra Virus (Equine Morbillivirus) in Fruit Bats, Horses and Cats. Aust Vet J 1998, 76, 813–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, P.T.; Williamson, M.M. Hendra and Nipah Virus Infections. Vet Clin North Am Equine Pract 2000, 16, 597–603, xi. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westbury, H.A.; Hooper, P.T.; Brouwer, S.L.; Selleck, P.W. Susceptibility of Cats to Equine Morbillivirus. Aust Vet J 1996, 74, 132–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallister, J.; Middleton, D.; Wang, L.-F.; Klein, R.; Haining, J.; Robinson, R.; Yamada, M.; White, J.; Payne, J.; Feng, Y.-R.; et al. A Recombinant Hendra Virus G Glycoprotein-Based Subunit Vaccine Protects Ferrets from Lethal Hendra Virus Challenge. Vaccine 2011, 29, 5623–5630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, K.T.; Grosjean, I.; Brisson, C.; Blanquier, B.; Fevre-Montange, M.; Bernard, A.; Loth, P.; Georges-Courbot, M.-C.; Chevallier, M.; Akaoka, H.; et al. A Golden Hamster Model for Human Acute Nipah Virus Infection. Am J Pathol 2003, 163, 2127–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marianneau, P.; Guillaume, V.; Wong, T.; Badmanathan, M.; Looi, R.Y.; Murri, S.; Loth, P.; Tordo, N.; Wild, F.; Horvat, B.; et al. Experimental Infection of Squirrel Monkeys with Nipah Virus. Emerg Infect Dis 2010, 16, 507–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisbert, T.W.; Daddario-DiCaprio, K.M.; Hickey, A.C.; Smith, M.A.; Chan, Y.-P.; Wang, L.-F.; Mattapallil, J.J.; Geisbert, J.B.; Bossart, K.N.; Broder, C.C. Development of an Acute and Highly Pathogenic Nonhuman Primate Model of Nipah Virus Infection. PLoS One 2010, 5, e10690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geisbert, J.B.; Borisevich, V.; Prasad, A.N.; Agans, K.N.; Foster, S.L.; Deer, D.J.; Cross, R.W.; Mire, C.E.; Geisbert, T.W.; Fenton, K.A. An Intranasal Exposure Model of Lethal Nipah Virus Infection in African Green Monkeys. J Infect Dis 2020, 221, S414–S418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prasad, A.N.; Woolsey, C.; Geisbert, J.B.; Agans, K.N.; Borisevich, V.; Deer, D.J.; Mire, C.E.; Cross, R.W.; Fenton, K.A.; Broder, C.C.; et al. Resistance of Cynomolgus Monkeys to Nipah and Hendra Virus Disease Is Associated With Cell-Mediated and Humoral Immunity. J Infect Dis 2020, 221, S436–S447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, C.S.; Lowry, J.; Juelich, T.; Atkins, C.; Johnson, K.; Smith, J.K.; Panis, M.; Ikegami, T.; tenOever, B.; Freiberg, A.N.; et al. Nipah Virus Bangladesh Infection Elicits Organ-Specific Innate and Inflammatory Responses in the Marmoset Model. J Infect Dis 2023. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton, D.J.; Morrissy, C.J.; van der Heide, B.M.; Russell, G.M.; Braun, M.A.; Westbury, H.A.; Halpin, K.; Daniels, P.W. Experimental Nipah Virus Infection in Pteropid Bats (Pteropus Poliocephalus). J Comp Pathol 2007, 136, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torres-Velez, F.J.; Shieh, W.-J.; Rollin, P.E.; Morken, T.; Brown, C.; Ksiazek, T.G.; Zaki, S.R. Histopathologic and Immunohistochemical Characterization of Nipah Virus Infection in the Guinea Pig. Vet Pathol 2008, 45, 576–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton, D.J.; Westbury, H.A.; Morrissy, C.J.; van der Heide, B.M.; Russell, G.M.; Braun, M.A.; Hyatt, A.D. Experimental Nipah Virus Infection in Pigs and Cats. J Comp Pathol 2002, 126, 124–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weingartl, H.; Czub, S.; Copps, J.; Berhane, Y.; Middleton, D.; Marszal, P.; Gren, J.; Smith, G.; Ganske, S.; Manning, L.; et al. Invasion of the Central Nervous System in a Porcine Host by Nipah Virus. J Virol 2005, 79, 7528–7534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berhane, Y.; Weingartl, H.M.; Lopez, J.; Neufeld, J.; Czub, S.; Embury-Hyatt, C.; Goolia, M.; Copps, J.; Czub, M. Bacterial Infections in Pigs Experimentally Infected with Nipah Virus. Transbound Emerg Dis 2008, 55, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berhane, Y.; Berry, J.D.; Ranadheera, C.; Marszal, P.; Nicolas, B.; Yuan, X.; Czub, M.; Weingartl, H. Production and Characterization of Monoclonal Antibodies against Binary Ethylenimine Inactivated Nipah Virus. J Virol Methods 2006, 132, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weingartl, H.M.; Berhane, Y.; Caswell, J.L.; Loosmore, S.; Audonnet, J.-C.; Roth, J.A.; Czub, M. Recombinant Nipah Virus Vaccines Protect Pigs against Challenge. J Virol 2006, 80, 7929–7938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungall, B.A.; Middleton, D.; Crameri, G.; Bingham, J.; Halpin, K.; Russell, G.; Green, D.; McEachern, J.; Pritchard, L.I.; Eaton, B.T.; et al. Feline Model of Acute Nipah Virus Infection and Protection with a Soluble Glycoprotein-Based Subunit Vaccine. J Virol 2006, 80, 12293–12302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McEachern, J.A.; Bingham, J.; Crameri, G.; Green, D.J.; Hancock, T.J.; Middleton, D.; Feng, Y.-R.; Broder, C.C.; Wang, L.-F.; Bossart, K.N. A Recombinant Subunit Vaccine Formulation Protects against Lethal Nipah Virus Challenge in Cats. Vaccine 2008, 26, 3842–3852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mungall, B.A.; Middleton, D.; Crameri, G.; Halpin, K.; Bingham, J.; Eaton, B.T.; Broder, C.C. Vertical Transmission and Fetal Replication of Nipah Virus in an Experimentally Infected Cat. J Infect Dis 2007, 196, 812–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enserink, M. Emerging Diseases. Malaysian Researchers Trace Nipah Virus Outbreak to Bats. Science 2000, 289, 518–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pallister, J.A.; Klein, R.; Arkinstall, R.; Haining, J.; Long, F.; White, J.R.; Payne, J.; Feng, Y.-R.; Wang, L.-F.; Broder, C.C.; et al. Vaccination of Ferrets with a Recombinant G Glycoprotein Subunit Vaccine Provides Protection against Nipah Virus Disease for over 12 Months. Virol J 2013, 10, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mire, C.E.; Versteeg, K.M.; Cross, R.W.; Agans, K.N.; Fenton, K.A.; Whitt, M.A.; Geisbert, T.W. Single Injection Recombinant Vesicular Stomatitis Virus Vaccines Protect Ferrets against Lethal Nipah Virus Disease. Virol J 2013, 10, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schountz, T.; Campbell, C.; Wagner, K.; Rovnak, J.; Martellaro, C.; DeBuysscher, B.L.; Feldmann, H.; Prescott, J. Differential Innate Immune Responses Elicited by Nipah Virus and Cedar Virus Correlate with Disparate In Vivo Pathogenesis in Hamsters. Viruses 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, G.A.; Haining, J.; Hancock, T.J.; Robinson, R.; Foord, A.J.; Barr, J.A.; Riddell, S.; Heine, H.G.; White, J.R.; Crameri, G.; et al. Experimental Infection of Horses with Hendra Virus/Australia/Horse/2008/Redlands. Emerg Infect Dis 2011, 17, 2232–2238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldspink, L.K.; Edson, D.W.; Vidgen, M.E.; Bingham, J.; Field, H.E.; Smith, C.S. Natural Hendra Virus Infection in Flying-Foxes - Tissue Tropism and Risk Factors. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0128835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edson, D.; Field, H.; McMichael, L.; Vidgen, M.; Goldspink, L.; Broos, A.; Melville, D.; Kristoffersen, J.; de Jong, C.; McLaughlin, A.; et al. Routes of Hendra Virus Excretion in Naturally-Infected Flying-Foxes: Implications for Viral Transmission and Spillover Risk. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0140670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.E.; Umapathi, T.; Tan, C.B.; Tjia, H.T.; Chua, T.S.; Oh, H.M.; Fock, K.M.; Kurup, A.; Das, A.; Tan, A.K.; et al. The Neurological Manifestations of Nipah Virus Encephalitis, a Novel Paramyxovirus. Ann Neurol 1999, 46, 428–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maisner, A.; Neufeld, J.; Weingartl, H. Organ- and Endotheliotropism of Nipah Virus Infections in Vivo and in Vitro. Thromb Haemost 2009, 102, 1014–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baseler, L.; de Wit, E.; Scott, D.P.; Munster, V.J.; Feldmann, H. Syrian Hamsters (Mesocricetus Auratus) Oronasally Inoculated with a Nipah Virus Isolate from Bangladesh or Malaysia Develop Similar Respiratory Tract Lesions. Vet Pathol 2015, 52, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baseler, L.; Scott, D.P.; Saturday, G.; Horne, E.; Rosenke, R.; Thomas, T.; Meade-White, K.; Haddock, E.; Feldmann, H.; de Wit, E. Identifying Early Target Cells of Nipah Virus Infection in Syrian Hamsters. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2016, 10, e0005120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeBuysscher, B.L.; Scott, D.P.; Rosenke, R.; Wahl, V.; Feldmann, H.; Prescott, J. Nipah Virus Efficiently Replicates in Human Smooth Muscle Cells without Cytopathic Effect. Cells 2021, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, S.R.; Scholte, F.E.M.; Harmon, J.R.; Coleman-McCray, J.D.; Lo, M.K.; Montgomery, J.M.; Nichol, S.T.; Spiropoulou, C.F.; Spengler, J.R. In Situ Imaging of Fluorescent Nipah Virus Respiratory and Neurological Tissue Tropism in the Syrian Hamster Model. J Infect Dis 2020, 221, S448–S453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ang, L.T.; Nguyen, A.T.; Liu, K.J.; Chen, A.; Xiong, X.; Curtis, M.; Martin, R.M.; Raftry, B.C.; Ng, C.Y.; Vogel, U.; et al. Generating Human Artery and Vein Cells from Pluripotent Stem Cells Highlights the Arterial Tropism of Nipah and Hendra Viruses. Cell 2022, 185, 2523–2541e30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stachowiak, B.; Weingartl, H.M. Nipah Virus Infects Specific Subsets of Porcine Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells. PLoS One 2012, 7, e30855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamb, R.A.; Joshi, S.B.; Dutch, R.E. The Paramyxovirus Fusion Protein Forms an Extremely Stable Core Trimer: Structural Parallels to Influenza Virus Haemagglutinin and HIV-1 Gp41. Mol Membr Biol 1999, 16, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, R.A. Paramyxovirus Fusion: A Hypothesis for Changes. Virology 1993, 197, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossart, K.N.; Wang, L.F.; Eaton, B.T.; Broder, C.C. Functional Expression and Membrane Fusion Tropism of the Envelope Glycoproteins of Hendra Virus. Virology 2001, 290, 121–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossart, K.N.; Wang, L.-F.; Flora, M.N.; Chua, K.B.; Lam, S.K.; Eaton, B.T.; Broder, C.C. Membrane Fusion Tropism and Heterotypic Functional Activities of the Nipah Virus and Hendra Virus Envelope Glycoproteins. J Virol 2002, 76, 11186–11198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonaparte, M.I.; Dimitrov, A.S.; Bossart, K.N.; Crameri, G.; Mungall, B.A.; Bishop, K.A.; Choudhry, V.; Dimitrov, D.S.; Wang, L.-F.; Eaton, B.T.; et al. Ephrin-B2 Ligand Is a Functional Receptor for Hendra Virus and Nipah Virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102, 10652–10657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negrete, O.A.; Levroney, E.L.; Aguilar, H.C.; Bertolotti-Ciarlet, A.; Nazarian, R.; Tajyar, S.; Lee, B. EphrinB2 Is the Entry Receptor for Nipah Virus, an Emergent Deadly Paramyxovirus. Nature 2005, 436, 401–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrete, O.A.; Wolf, M.C.; Aguilar, H.C.; Enterlein, S.; Wang, W.; Mühlberger, E.; Su, S. V; Bertolotti-Ciarlet, A.; Flick, R.; Lee, B. Two Key Residues in EphrinB3 Are Critical for Its Use as an Alternative Receptor for Nipah Virus. PLoS Pathog 2006, 2, e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillaume, V.; Aslan, H.; Ainouze, M.; Guerbois, M.; Wild, T.F.; Buckland, R.; Langedijk, J.P.M. Evidence of a Potential Receptor-Binding Site on the Nipah Virus G Protein (NiV-G): Identification of Globular Head Residues with a Role in Fusion Promotion and Their Localization on an NiV-G Structural Model. J Virol 2006, 80, 7546–7554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negrete, O.A.; Chu, D.; Aguilar, H.C.; Lee, B. Single Amino Acid Changes in the Nipah and Hendra Virus Attachment Glycoproteins Distinguish EphrinB2 from EphrinB3 Usage. J Virol 2007, 81, 10804–10814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, A.; Klein, R. Multiple Roles of Ephrins in Morphogenesis, Neuronal Networking, and Brain Function. Genes Dev 2003, 17, 1429–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poliakov, A.; Cotrina, M.; Wilkinson, D.G. Diverse Roles of Eph Receptors and Ephrins in the Regulation of Cell Migration and Tissue Assembly. Dev Cell 2004, 7, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, M.D.; Romero, M.I.; Lush, M.E.; Lu, Q.R.; Henkemeyer, M.; Parada, L.F. Ephrin-B3 Is a Myelin-Based Inhibitor of Neurite Outgrowth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2005, 102, 10694–10699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, N.; Hoffmann, M.; Weis, M.; Drexler, J.F.; Müller, M.A.; Winter, C.; Corman, V.M.; Gützkow, T.; Drosten, C.; Maisner, A.; et al. Surface Glycoproteins of an African Henipavirus Induce Syncytium Formation in a Cell Line Derived from an African Fruit Bat, Hypsignathus Monstrosus. J Virol 2013, 87, 13889–13891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diederich, S.; Moll, M.; Klenk, H.-D.; Maisner, A. The Nipah Virus Fusion Protein Is Cleaved within the Endosomal Compartment. Journal of Biological Chemistry 2005, 280, 29899–29903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pager, C.T.; Craft, W.W.; Patch, J.; Dutch, R.E. A Mature and Fusogenic Form of the Nipah Virus Fusion Protein Requires Proteolytic Processing by Cathepsin L. Virology 2006, 346, 251–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pager, C.T.; Dutch, R.E. Cathepsin L Is Involved in Proteolytic Processing of the Hendra Virus Fusion Protein. J Virol 2005, 79, 12714–12720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krüger, N.; Hoffmann, M.; Drexler, J.F.; Müller, M.A.; Corman, V.M.; Drosten, C.; Herrler, G. Attachment Protein G of an African Bat Henipavirus Is Differentially Restricted in Chiropteran and Nonchiropteran Cells. J Virol 2014, 88, 11973–11980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weis, M.; Behner, L.; Hoffmann, M.; Krüger, N.; Herrler, G.; Drosten, C.; Drexler, J.F.; Dietzel, E.; Maisner, A. Characterization of African Bat Henipavirus GH-M74a Glycoproteins. J Gen Virol 2014, 95, 539–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, P.; Escudero Pérez, B.; Drexler, J.F.; Corman, V.M.; Müller, M.A.; Drosten, C.; Volchkov, V. Surface Glycoproteins of the Recently Identified African Henipavirus Promote Viral Entry and Cell Fusion in a Range of Human, Simian and Bat Cell Lines. Virus Res 2014, 181, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rissanen, I.; Ahmed, A.A.; Azarm, K.; Beaty, S.; Hong, P.; Nambulli, S.; Duprex, W.P.; Lee, B.; Bowden, T.A. Idiosyncratic Mòjiāng Virus Attachment Glycoprotein Directs a Host-Cell Entry Pathway Distinct from Genetically Related Henipaviruses. Nat Commun 2017, 8, 16060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pryce, R.; Azarm, K.; Rissanen, I.; Harlos, K.; Bowden, T.A.; Lee, B. A Key Region of Molecular Specificity Orchestrates Unique Ephrin-B1 Utilization by Cedar Virus. Life Sci Alliance 2020, 3, e201900578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laing, E.D.; Navaratnarajah, C.K.; Cheliout Da Silva, S.; Petzing, S.R.; Xu, Y.; Sterling, S.L.; Marsh, G.A.; Wang, L.-F.; Amaya, M.; Nikolov, D.B.; et al. Structural and Functional Analyses Reveal Promiscuous and Species Specific Use of Ephrin Receptors by Cedar Virus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2019, 116, 20707–20715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).