Submitted:

14 August 2023

Posted:

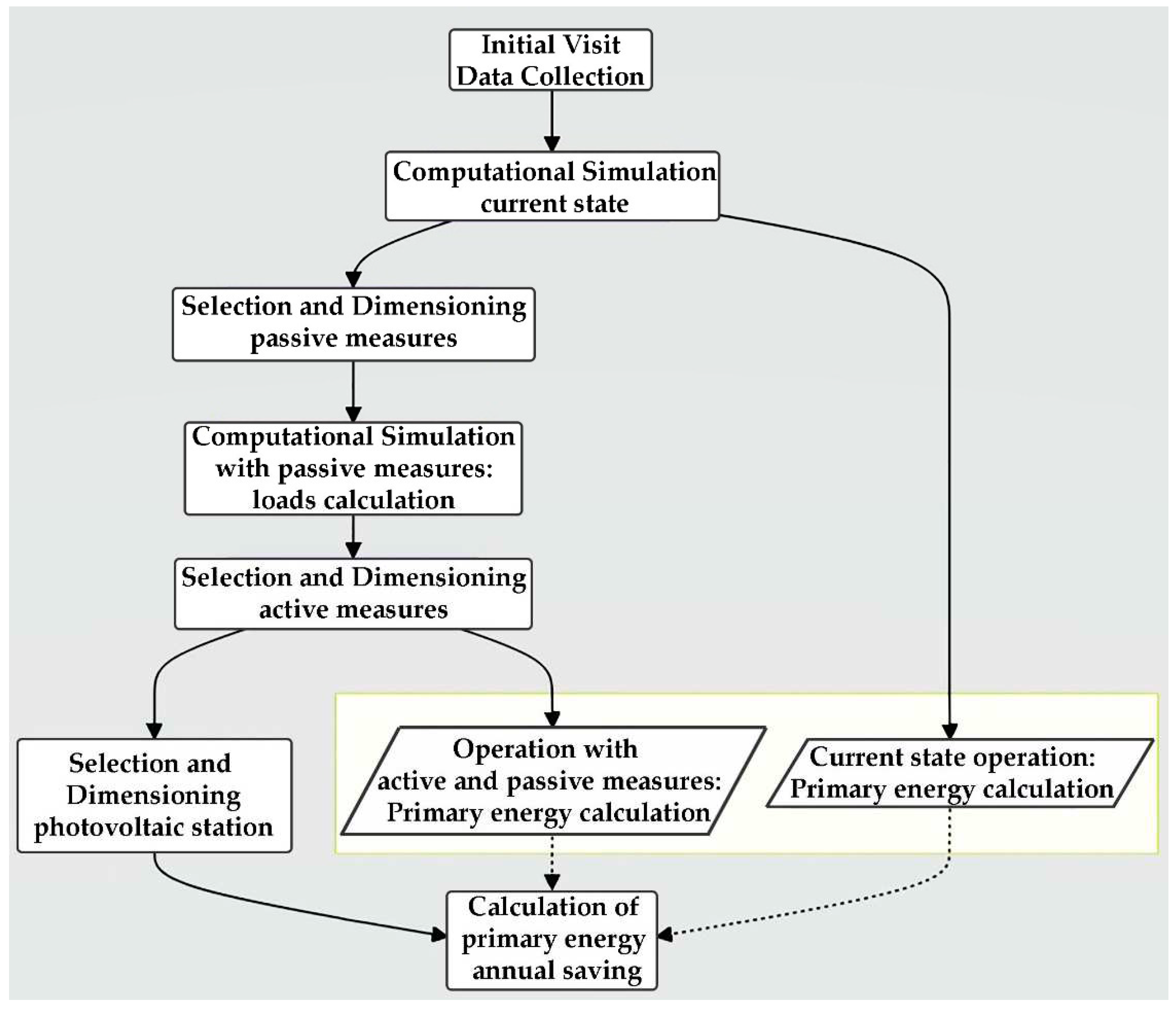

16 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.2. Literature review

1.3. Research aim

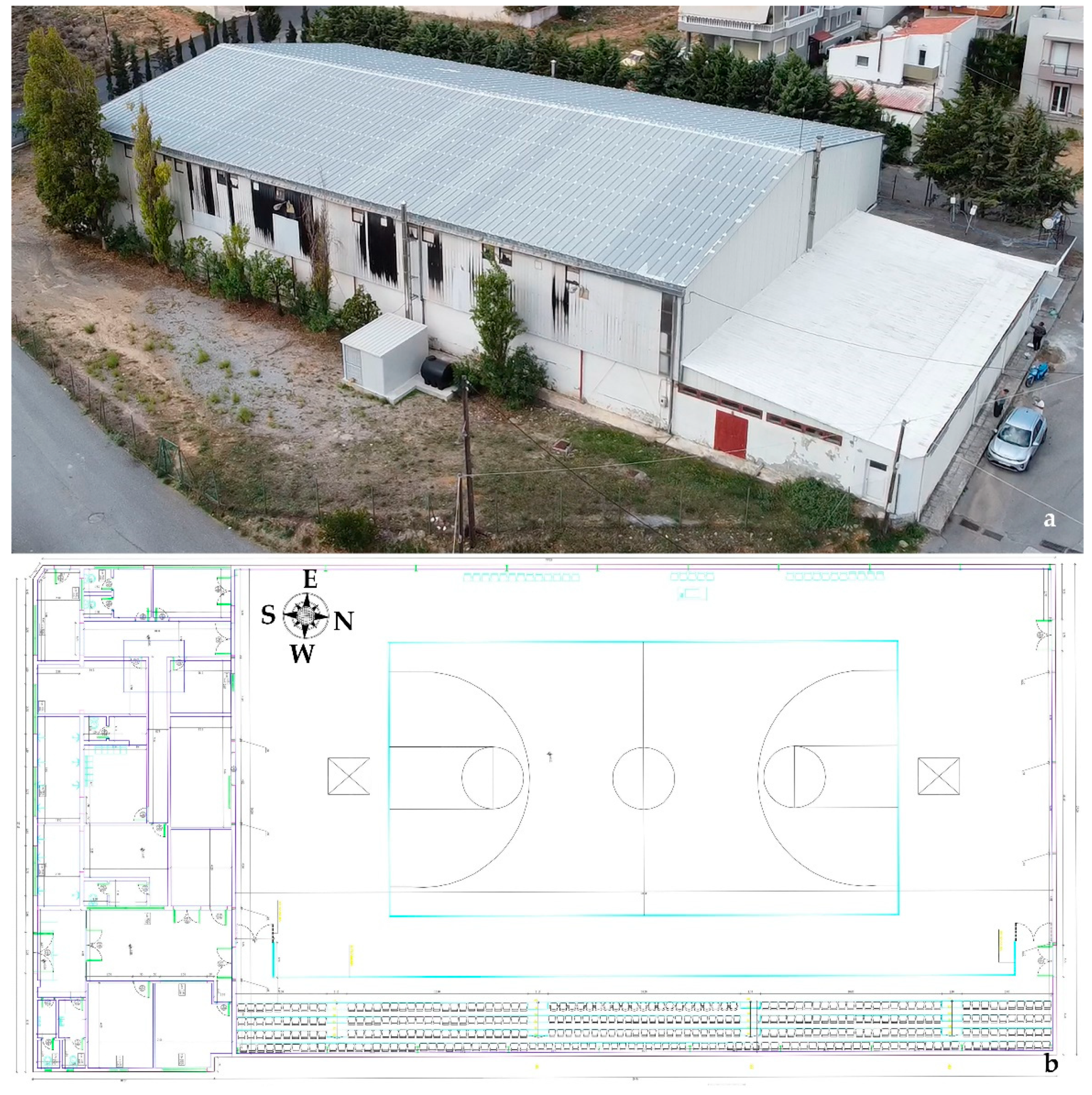

2. The sport facility

3. Methodology

- invitation for collaboration with the Municipality and establishment of an open communication line with the staff in charge for the operation and the maintenance of the facility;

- an initial visit in the sport facility and on-site investigation and collection of all required data regarding the existing architectural elements, the operation schedule and the energy demand;

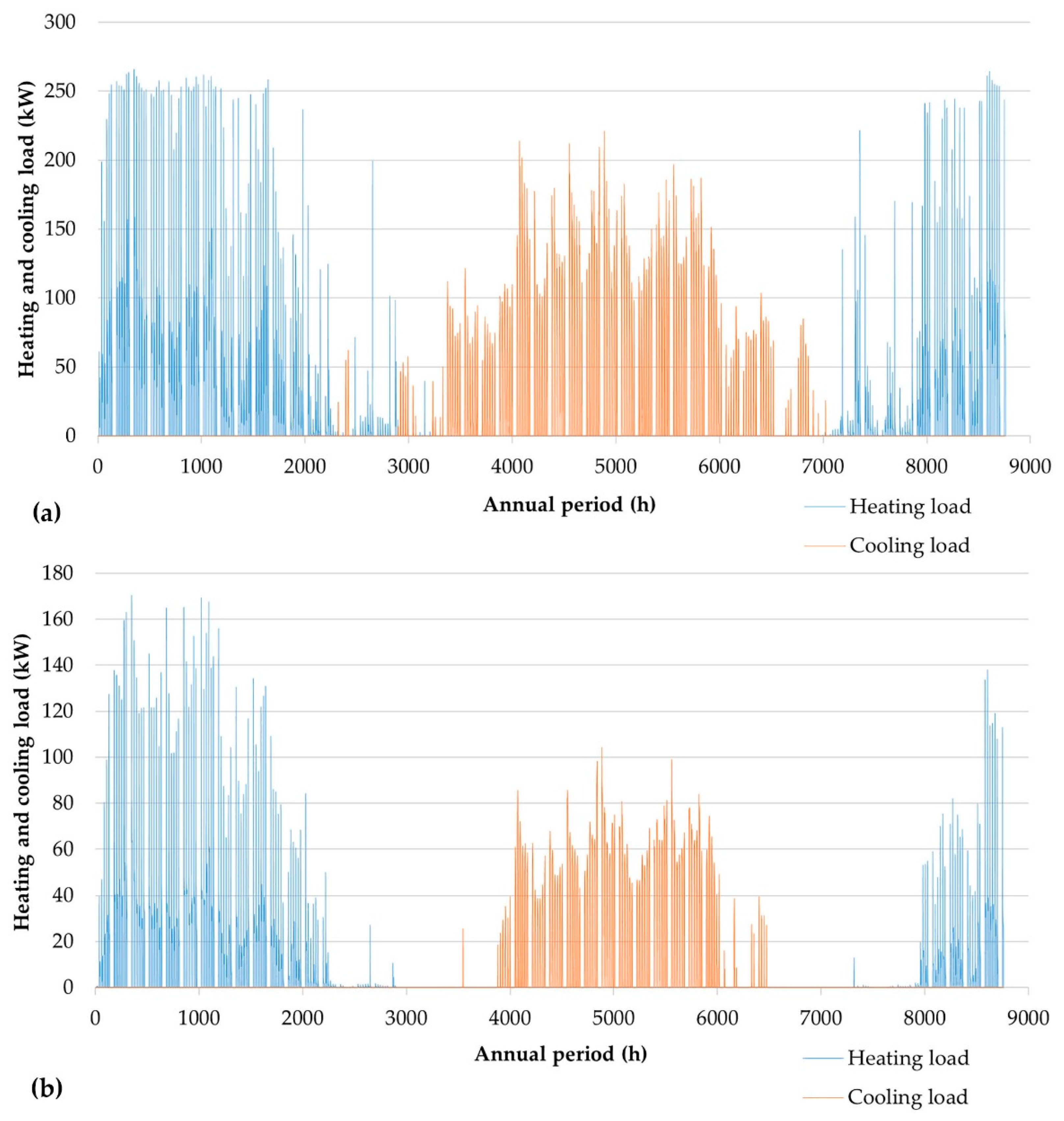

- first computational simulation of the sport facility’s operation in the existing condition and calculation of the indoor space heating and cooling load for full annual operation;

- calculation of the current primary energy consumption for full coverage of all final energy needs, with the existing active systems for indoor space conditioning, domestic hot water production and lighting;

- selection, siting and sizing of the most technically feasible and cost-effective passive measures, aiming at the minimisation of the indoor space heating and cooling load;

- second computational simulation of the sport facility’s operation with the introduction of the proposed passive measures and calculation of the indoor space heating and cooling load for full annual operation;

- selection and sizing of the most technically feasible and cost-effective active measures for indoor space conditioning, domestic hot water production and lighting;

- calculation of the primary energy consumption for full coverage of all final energy needs with the proposed active systems;

- sizing and siting of a photovoltaic park, for the annual compensation of the remaining electricity consumption;

- calculation of the achieved annual energy saving, the project’s total budget and other typical Key Performance Indicators (KPIs).

- the meteorological data were retrieved from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (see Section 4)

- the data regarding the new proposed equipment and the materials were retrieved from the manufacturers’ datasheets

- the data regarding the existing constructive elements in the facility were calculated or taken from the literature.

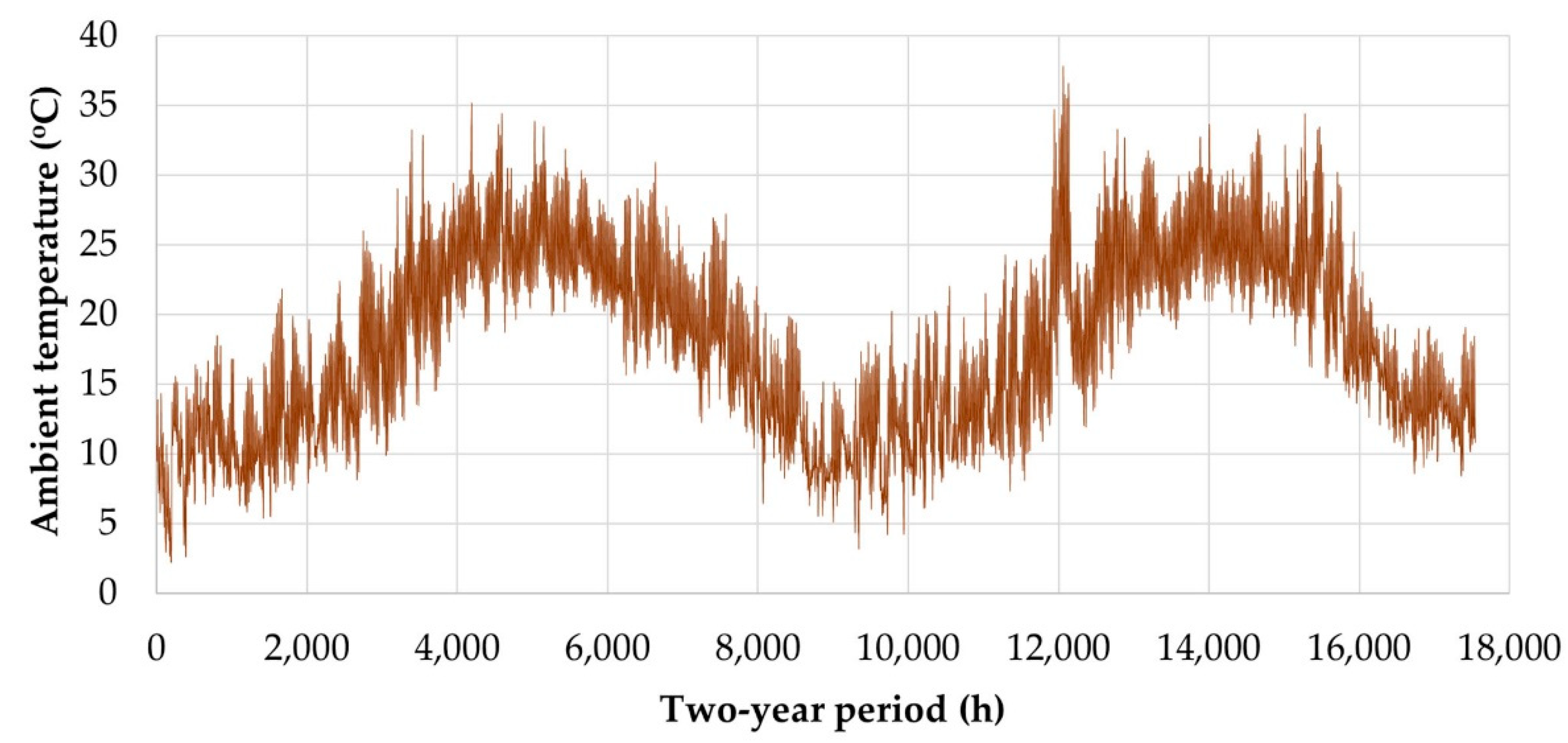

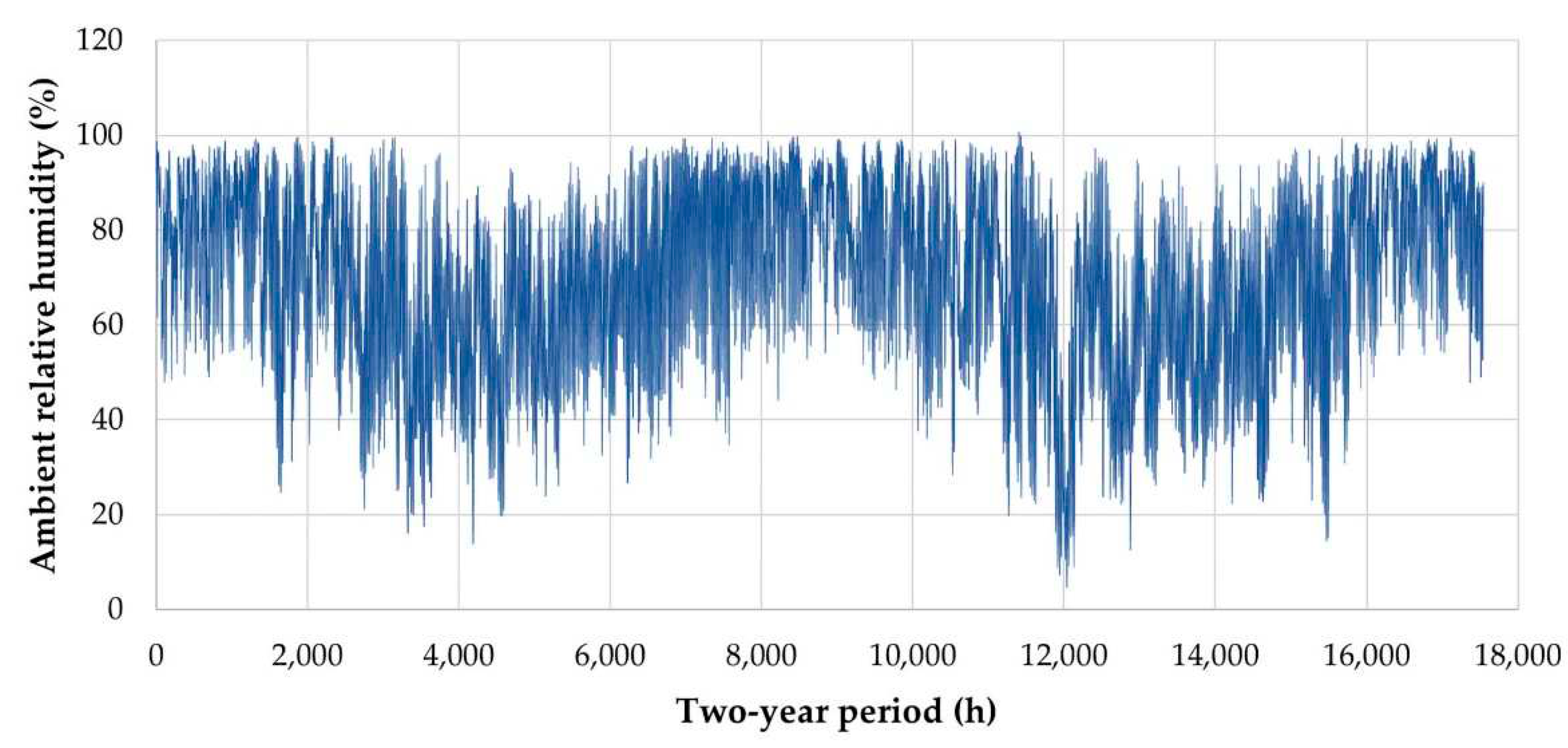

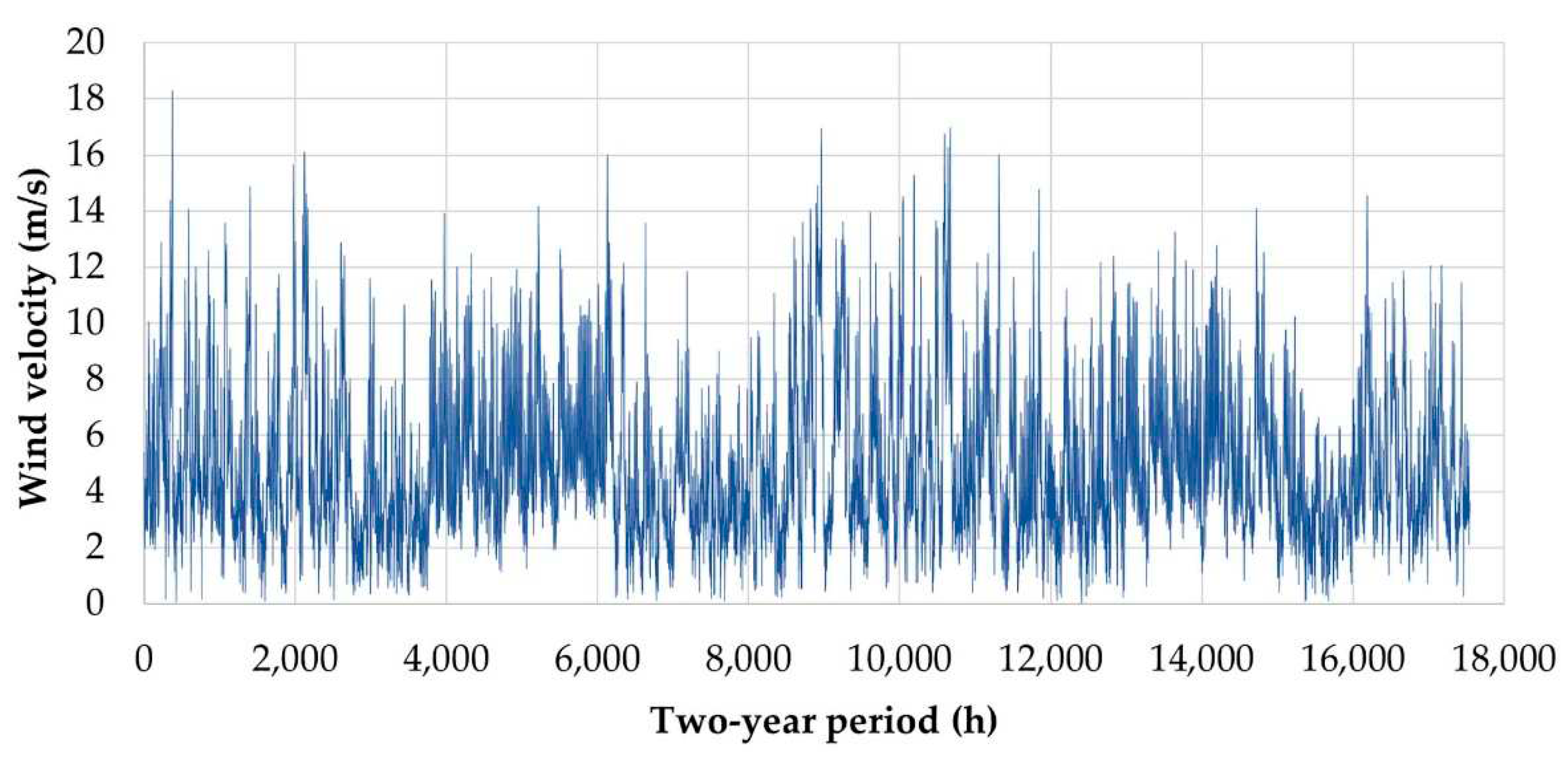

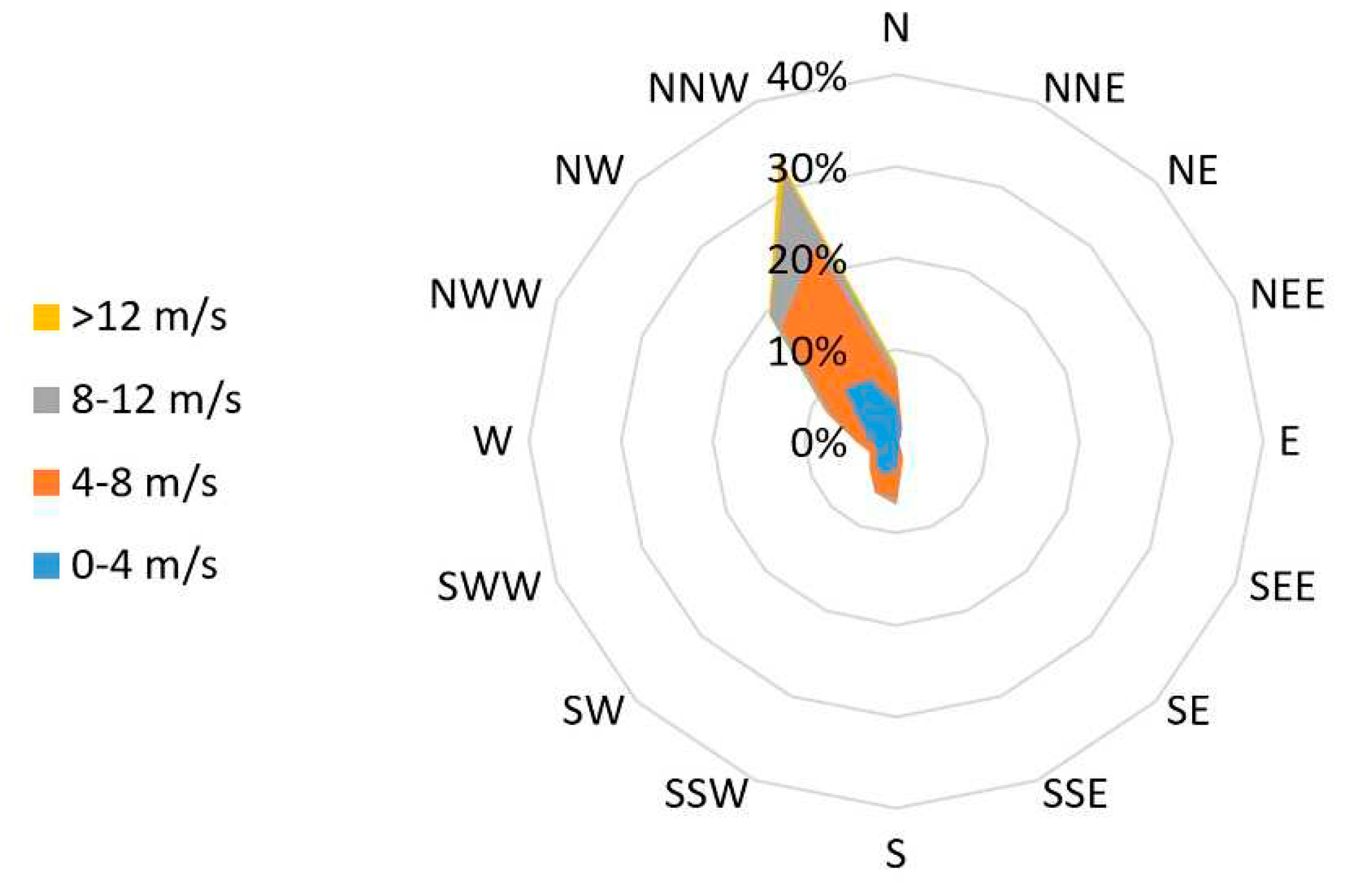

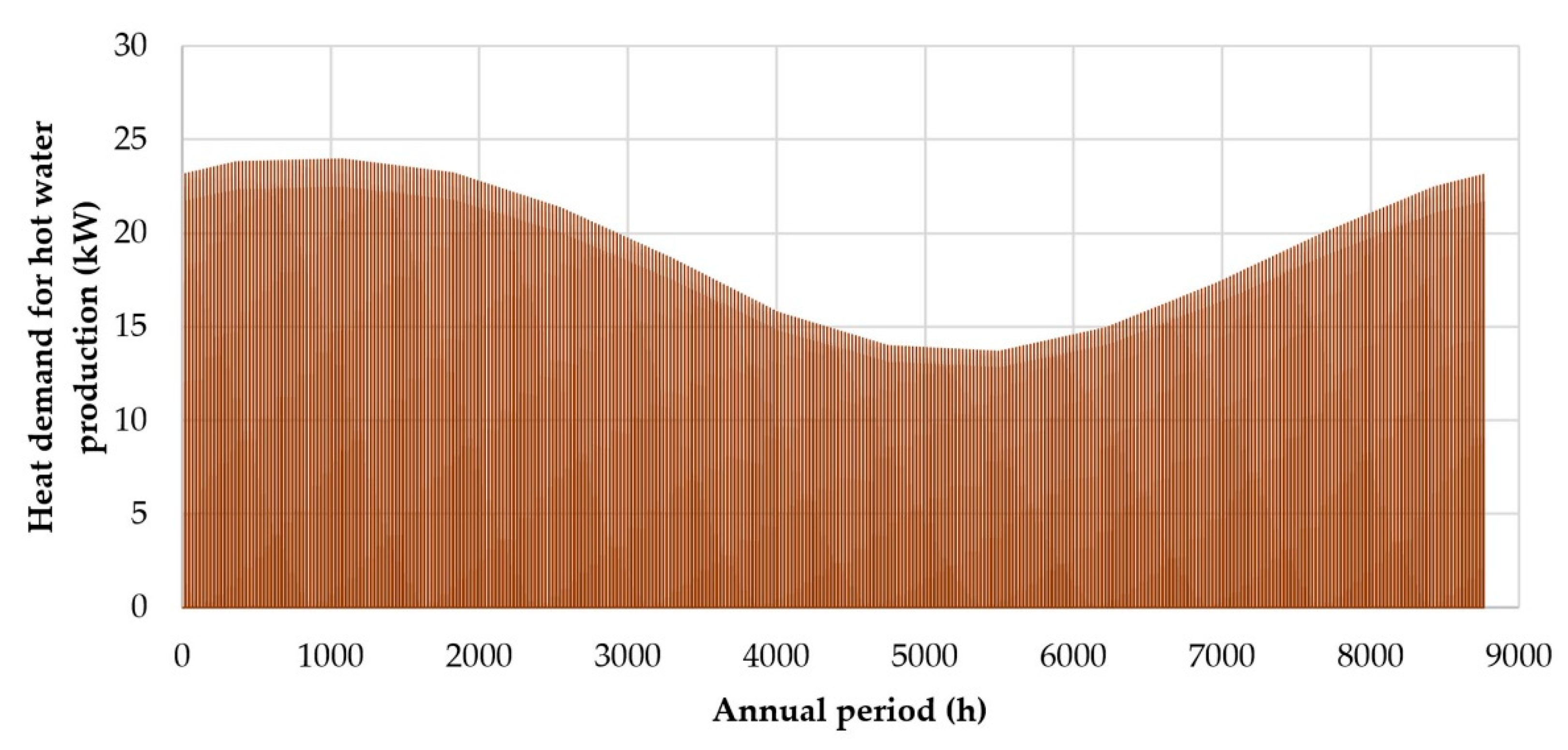

4. Climate conditions – meteorological data

5. The energy performance upgrade of the indoor sport hall

5.1. Current state

5.2. Energy consumption in the current state

- indoor space conditioning;

- domestic hot water production;

- indoor and outdoor space lighting.

5.2.1. Indoor space conditioning

- hi = 10 W/m2∙K and ho = 25 W/m2∙K for air flow over horizontal surfaces and for average wind speed of 5 m/s;

- hi = 7.7 W/m2∙K and ho = 25 W/m2∙K for air flow next to vertical surfaces and for average wind speed of 5 m/s.

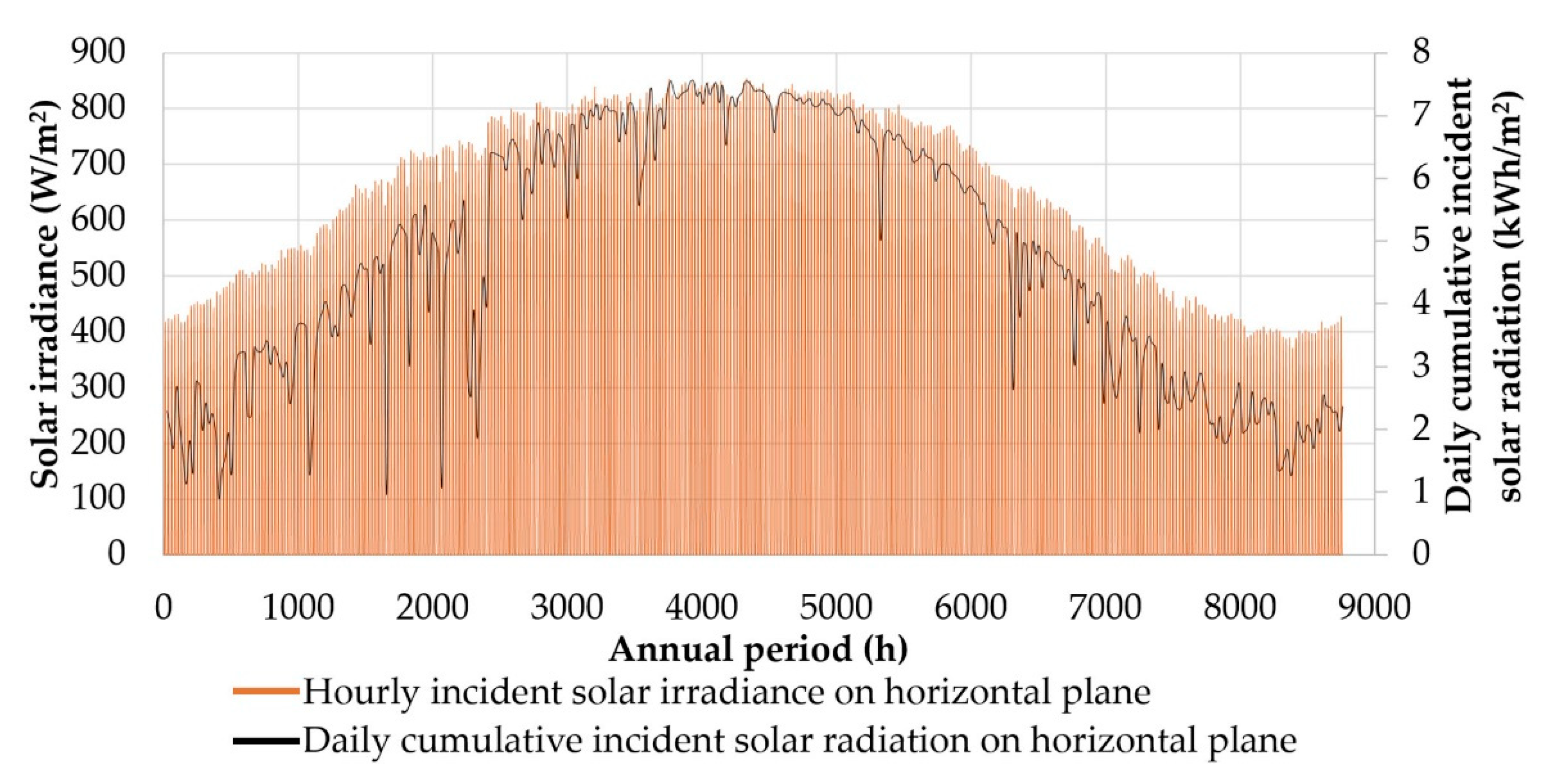

5.2.2. Domestic hot water production

- is the mass flow rate of the consumed hot water

- cp = 4.187 kJ/kg∙K the water specific heat capacity

- Thw = 45ο C the hot water required temperature

- Tsw the water temperature from the municipal water supply network. given by the Technical Directive 20701-1/2017 [67] (from 12.8 οC in February to 26.6 οC in August).

- during the winter period, namely from 16/10 to 14/4, the existing oil burner for the indoor space heating of the auxiliary building will be used, practically concurrently with the indoor space heating, also for the production of domestic hot water

- during the summer period, namely from 15/4 to 15/10, the existing electrical boilers will be used.

5.2.3. Lighting

- indoor space lighting of the main sport hall, covered by 32 mercury and 4 halogen floodlights, with nominal electrical power 250 W and 400 W for each one of them respectively;

- indoor space lighting of the auxiliary building, covered by fluorescent lamps installed in 28 old plastic luminaires without reflective surfaces;

- outdoor perimeter lighting of the overall building facility, covered by 4 mercury floodlights with nominal electrical power 250 W each.

5.2.4. Other electricity consumptions

- the three in total circulators of the heating hydraulic network, two for the main sport hall with 150 W nominal electrical input power each and one for the auxiliary building with 100 W nominal electrical input power;

- the 22 fans of the hydronic terminal units of the main sport hall with 183 W nominal electrical input power for each one.

- 808.8 kWh for the circulators of the main sport hall heating network

- 145.6 kWh for the circulators of the auxiliary building heating network

- 10.854,1 kWh for the hydronic unit fans.

5.2.5. Energy consumption synopsis in existing conditions

5.3. Proposed energy saving measures

- Replacement of all existing semi-transparent polycarbonate panels from the vertical walls of the main sport hall with stone wool panels of 8 cm thickness, with total net surface of 579.4 m2 and U-factor of 0.38 W/m2∙K.

- Installation of outer insulation in all vertical opaque surfaces constructed with reinforced concrete or bricks, with 7 cm thickness stone wool sheets. The new U-factors are calculated equal to 0.40 W/m2∙K for the bearing structure parts of the opaque surfaces and 0.34 W/m2∙K for the brick walls. The total opaque net area under insulation is equal to 471.7 m2.

- Replacement of all existing polyurethane panels on the main sport hall’s roof, of 1230 m2, with stone wool panels of 8 cm thickness. The new U-factor is calculated equal to 0.39 W/m2∙K.

- Installation of outer insulation on the auxiliary building’s roof of 304 m2 total area, with 7 cm thickness stone wool sheets. The new U-factor is calculated equal to 0.40 W/m2∙K.

- Replacement of all existing openings in the facility, with new, of low-e technology, with synthetic frame and double glazing. The new U-factors will be equal to 0.95 W/m2∙K for the windows and 1.2 W/m2∙K for the doors. In total 46 windows and 5 doors will be installed, with total areas equal to 44.6 m2 and 16.6 m2 respectively.

- Installation of 54 solar tubes on the main sport hall’s roof, in a 6 × 9 layout, for the maximisation of the natural lighting during the daytime.

- Additionally, the following active systems are proposed:

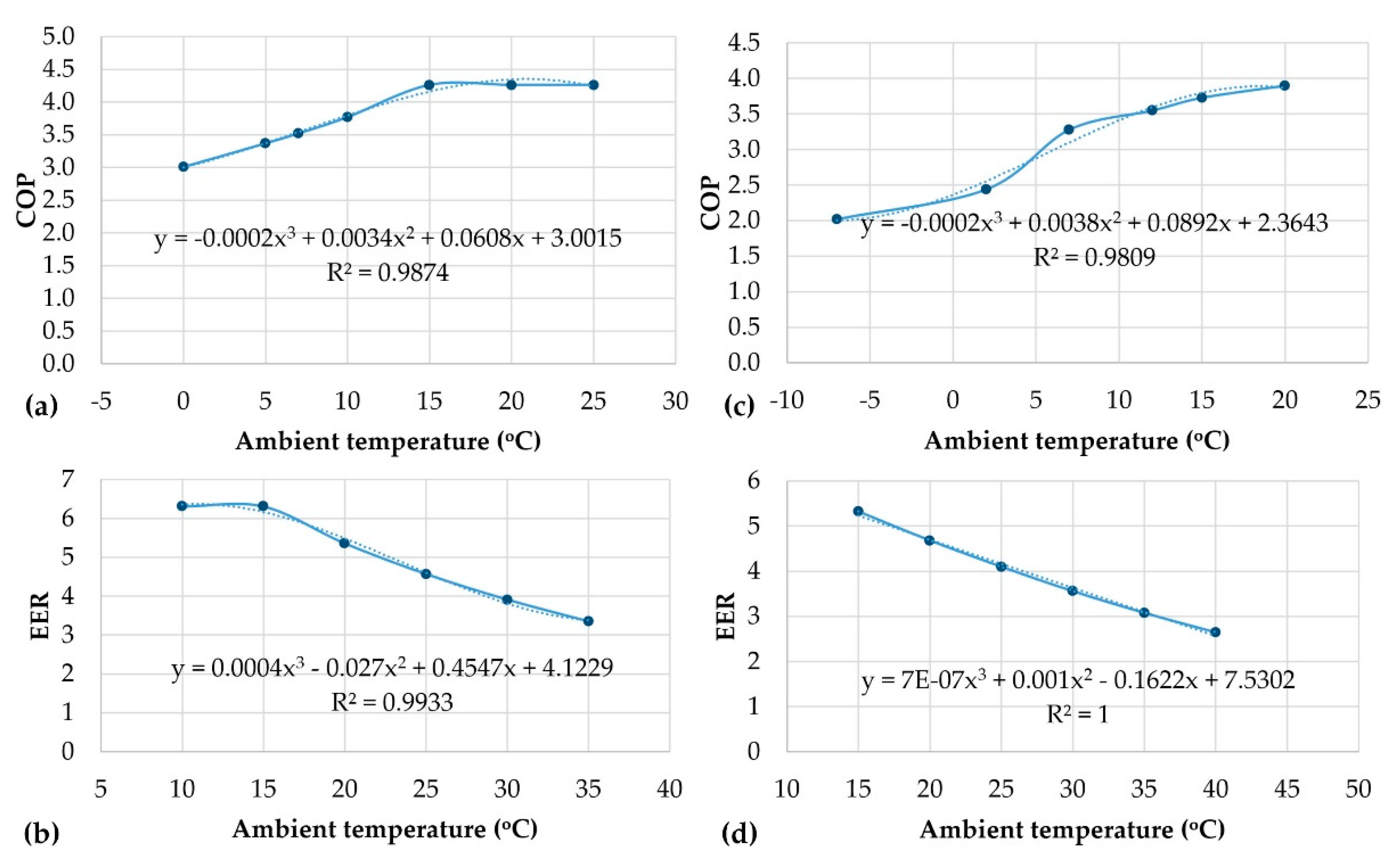

- Installation of an air-to-water heat pump with nominal capacity of 150 kWth and 149 kWth for heating and cooling respectively, for the indoor space conditioning of the main sport hall. The heat pump will exploit the existing hydraulic network and the 22 hydronic terminal units of 6.5 kWth nominal capacity both for heating and cooling, already installed for this specific space. The oil burners will be removed.

- Installation of a second air-to-water heat pump with nominal capacity 11.2 kWth and 10.0 kWth for heating and cooling respectively, for the indoor space conditioning of the auxiliary building, together with a new hydraulic network and new hydronic, terminal units. In total 12 new hydronic units will be installed, with nominal capacities from 1.6 kWth to 2.7 kWth both for heating and cooling.

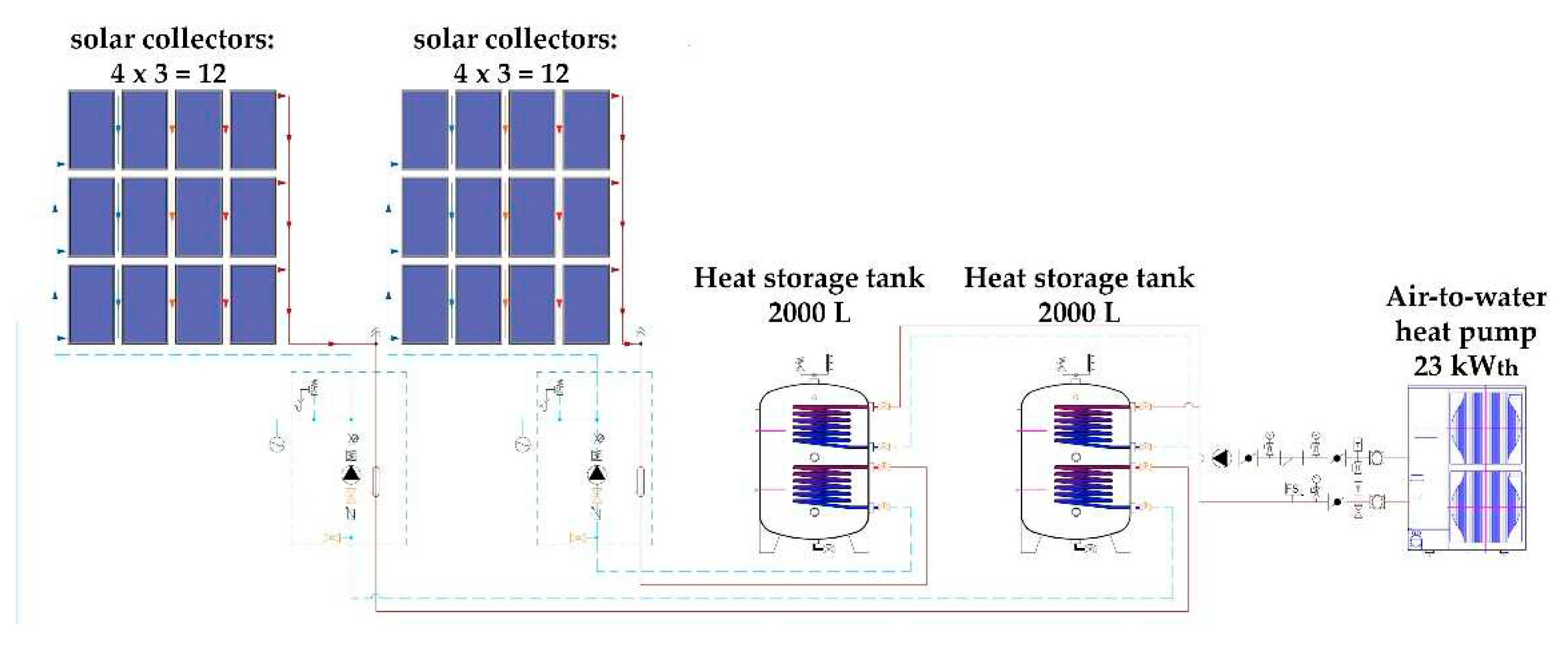

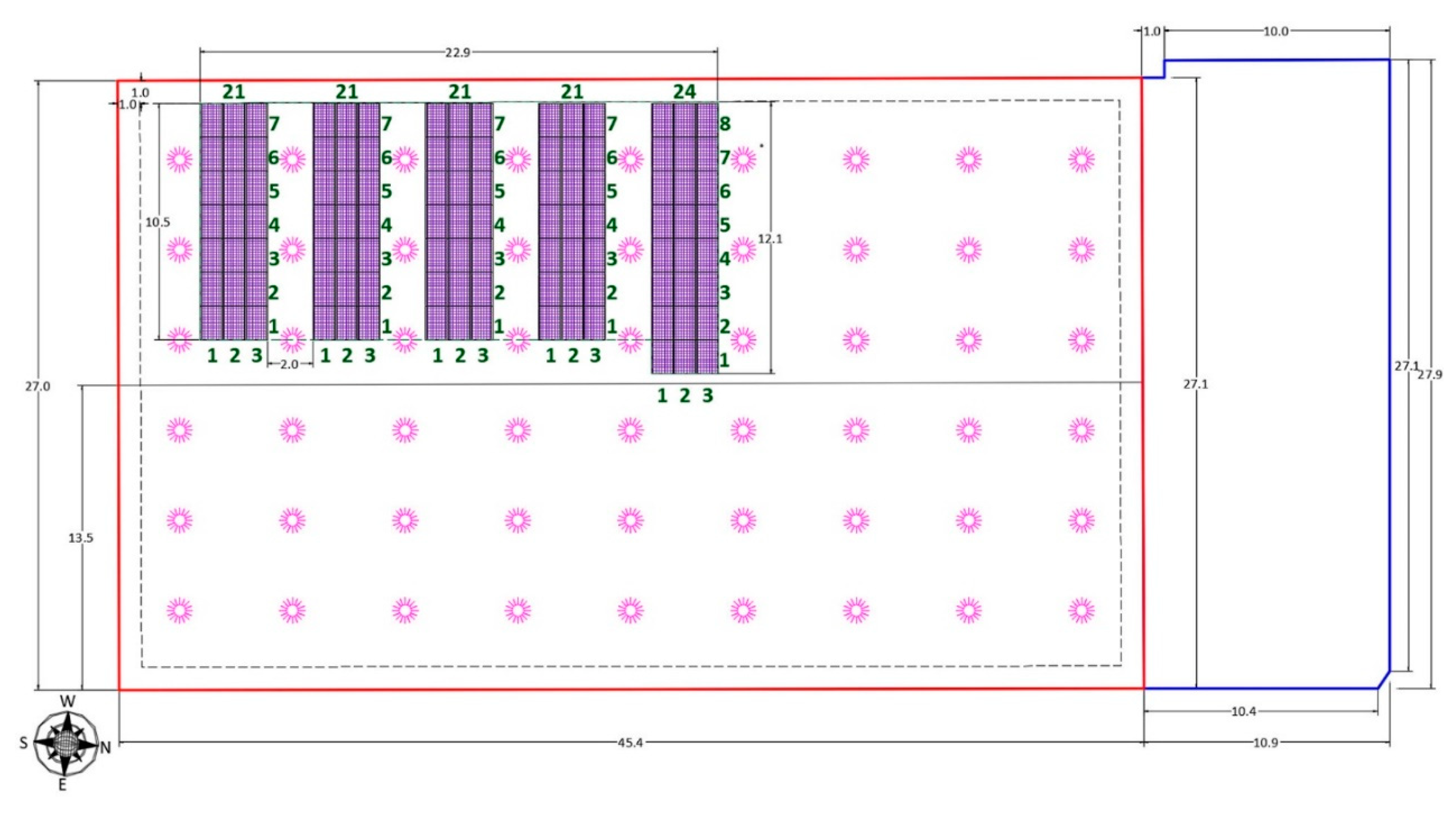

- Installation of a solar-combi system, with 24 solar collectors of 2.4 m2 absorber surface each and two heat storage tanks of 2000 L each, divided in two discrete groups, supported by a third air-to-water heat pump, with nominal heating capacity 23 kWth. The layout of this system is depicted in Figure 9. The solar collectors will be installed on the ground, at the south part of the outdoor available land in the facility, with an inclination of 30o with regard to the horizontal plane and southern orientation, so as to maximize the annual captured solar radiation.

- Replacement of all existing lamps and luminaires for indoor and outdoor lighting, with new with reflective surfaces and LED technology. In total 4 outdoor luminaires and 47 luminaires will be replaced in the auxiliary building, while 40 new LED floodlights will be installed in the main sports hall. The total installed lighting power will be reduced from 18.4 kW to 8.4 kW (54.4%).

- Finally, a photovoltaic plant will be installed on the main sports hall’s roof for the compensation of the remaining electricity consumption. The use of diesel oil will be totally eliminated with the removal of the diesel oil burners.

5.4. Energy consumption with the proposed upgrade measures

5.4.1. Indoor space conditioning

5.4.2. Domestic hot water production

- if Tsol > Tst, the circulator of the solar collectors’ primary closed loop turns on and heat is transferred from the solar collectors to the heat storage tanks;

- if Tsol ≤ Tst, then the heat produced by the solar collectors cannot be transferred to the heat storage tanks and the circulator of the solar collectors’ primary closed loop remains off;

- if Tst < Thw, then the back-up unit (the heat pump) is turned on,

| Tsol : | the supplied water temperature from the solar collectors; |

| Tst : | the stored water temperature in the heat storage tanks; |

| Thw : | the required hot water temperature. |

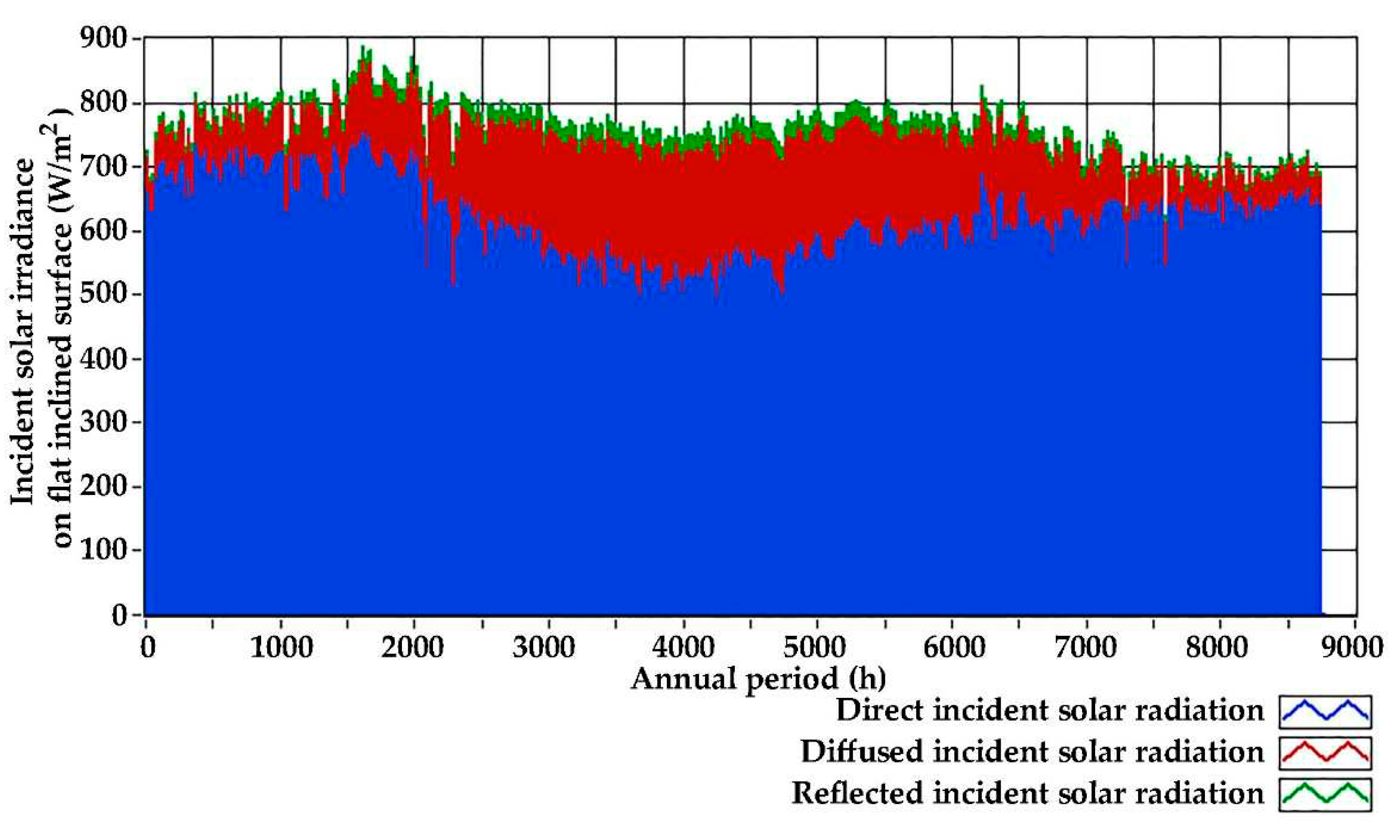

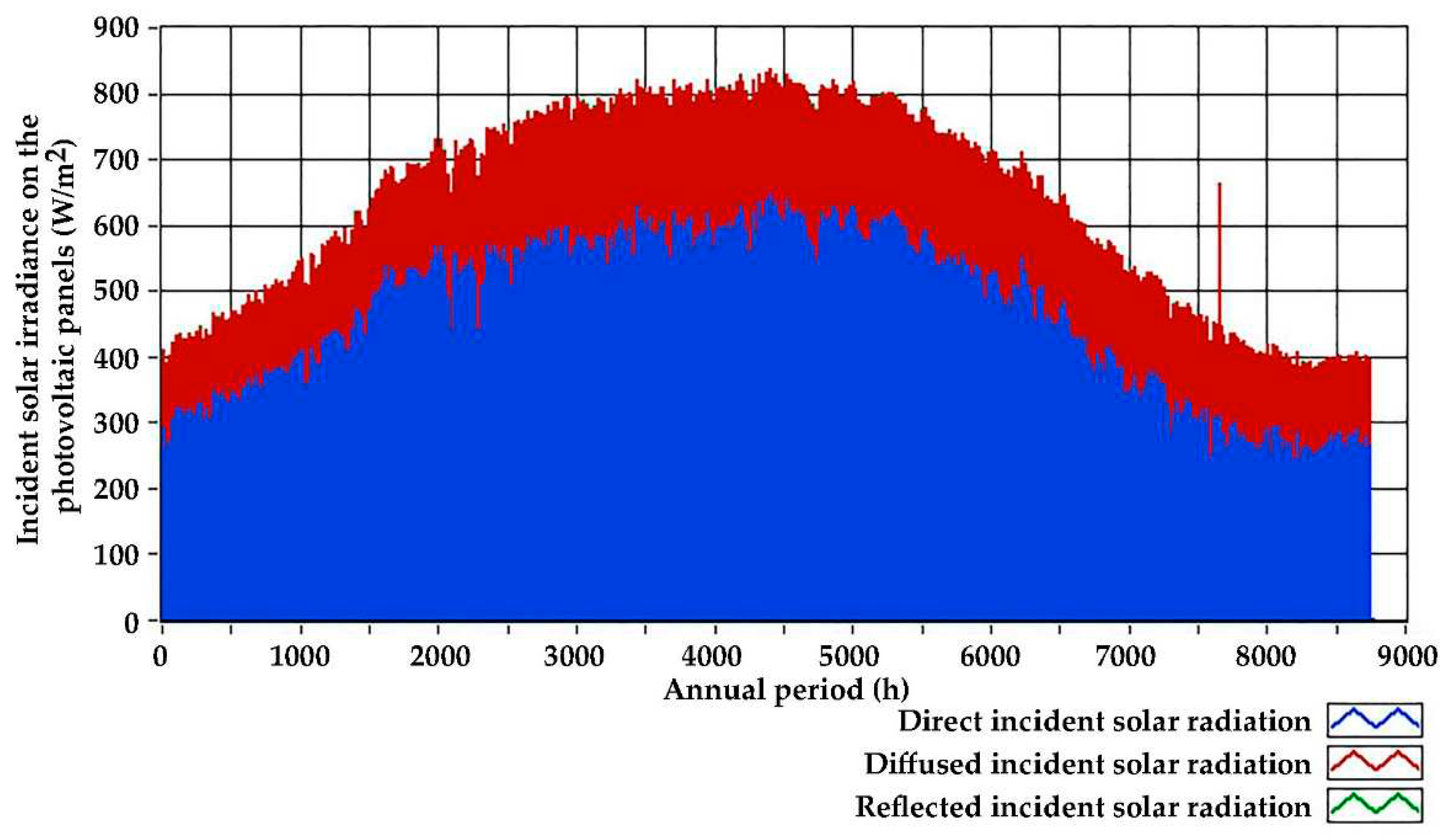

- the annual times series of the total incident solar irradiance on the 40ο inclined surface (Figure 12);

- the annual time series of the heat demand for domestic hot water production (Figure 8, Section 5.2.2);

- the water specific heat capacity (4.187 kJ/kg∙K);

-

the domestic hot water minimum required temperature Thw, set equal to:

- -

- from the 1st of January to the 30th of April: 40 οC

- -

- from the 1st of May to the 30th of June: 35 οC

- -

- from the 1st of July to the 15th of September: 30 οC

- -

- from the 16th of September to the 15th of November: 35 οC

- -

- from the 16th of November to the 31st of December: 40 οC;

- typical geometrical and thermo-physical features of a collective plate, flat solar collector’s model [42];

- typical geometrical and thermo-physical features of a heat storage tank with 2000 L storage capacity (2.4 m height, 1.3 m diameter, 10 mm insulation thickness and total U-factor 0.22 W/m2∙K).

| ΝSC: | the solar collectors’ total number in the system; |

| CSC: | the procurement price of one solar collector, adopted equal to 450 €; |

| ΝSΤ : | the heat storage tanks’ number in the system, with storage capacity of 2000 L; |

| CSΤ: | the procurement price of one 2000 L heat storage tank, adopted equal to 6000 €; |

| ESC: | the annual heat demand coverage for domestic hot water production from the solar-combi system; |

| ΤLP: | the solar-combi system’s life period, adopted equal to 15 years. |

- the 47.6% contribution of the solar collectors to the annual heat demand coverage;

- the consumption of electricity instead of diesel oil, which is totally eliminated for the specific use.

5.4.3. Lighting

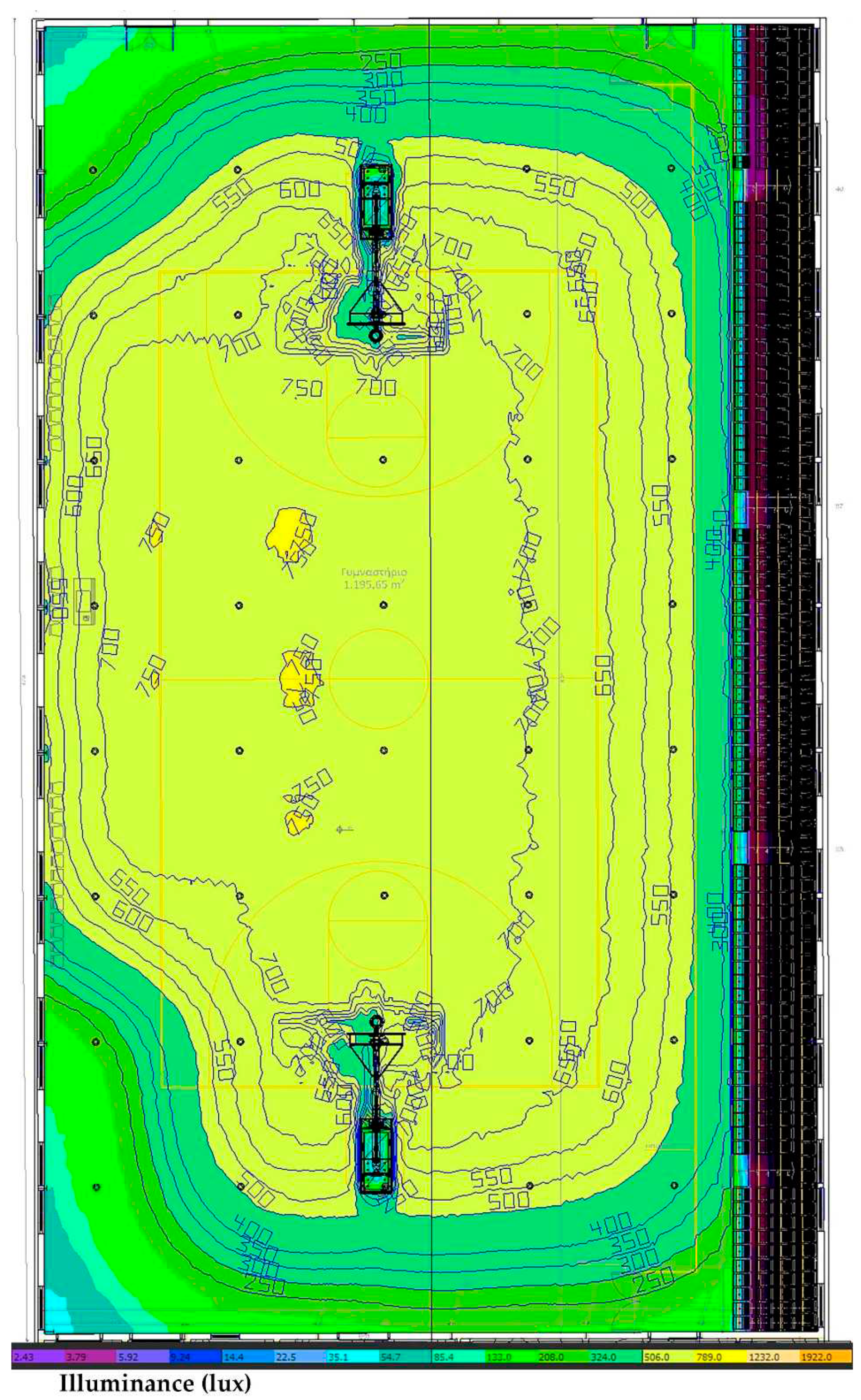

- The passive measures include the installation of 54 solar tubes on the main sport hall’s roof, arranged in nine parallel rows along the long side of the hall, with six tubes in each one of them, as shown in Figure 15. In the same figure the photometric results in the main sport hall at 1 m height above ground, obtained only from natural lighting penetration through the proposed solar tubes, are also presented for a typical summer day at 12:00 a.m. The same results are given in Figure 16, this time for a typical sunny day in winter, again at 12:00 a.m. The minimum required illuminance at 1 m height above height for an indoor sport hall according to the Greek Directive on Building’s Energy Performance is set at 300 lux, so, as seen in Figure 15 and Figure 16, with the proposed solar tubes number and layout, the required lighting conditions are achieved for both winter and summer and for sunny days.

- With these solar tubes it is anticipated that natural lighting will fully cover the lighting needs of the main sport hall during daytime for most days during the year. With this measure, the natural lighting loss due to the replacement of the existing semi-transparent and energy ineffective polycarbonate panels with the opaque stone wool panels will be also fully compensated.

- With regard to the active measures, practically all existing mercury and halogen floodlights for the main sport hall and the outdoor space lighting, as well as all the fluorescent lamps with the old and ineffective luminaires will be fully replaced, with LED floodlights and lamps and with luminaires with reflective surfaces. Specifically, the existing 32 mercury and 4 halogen floodlights in the main sport hall will be replaced with 40 LED floodlights, arranged in 8 rows with 5 units each, with nominal electrical power input of 147 W and nominal luminous flux of 22,000 lumens. The photometric results in the main sport hall with this proposed artificial lighting equipment is given in Figure 17. As seen in this figure, the illuminance requirements are also fully satisfied with this proposed floodlights arrangement. All photometric calculations presented in this section were executed with the DIALux evo 11 [69].

5.4.4. Remaining electricity consumption – summary of new consumptions

5.4.5. Photovoltaic station

5.5. Summary of energy saving results and key performance indicators

- Payback period:

- Annual primary energy saving:

-

Annual Renewable Energy Sources (RES) penetration:The total contribution of the involved RES technologies to the annual energy demand coverage comes from:

- -

- the production of 40,195 kWh of electricity from the photovoltaic plant, which corresponds to 116,565.5 kWh of primary energy

- -

- the production of 19.692,7 kWh of heat from the solar collectors, which corresponds to 35.804,9 kWh of primary solar radiation, by assuming a typical average efficiency of 55% for the solar collectors.

-

CO2 emissions saving:The annual CO2 emissions saving is due to the elimination of the diesel oil consumption and the electricity saving and demand compensation with the photovoltaic plant. According to the Greek Directive on the Buildings’ Energy Performance [66], the following factors are introduced as the specific CO2 emissions:

- -

- 0.989 kg CO2/kWh of electricity

- -

- 0.264 kg CO2/kWh of primary energy corresponding to diesel oil consumption.

Given the aforementioned factors, the CO2 emissions annual saving are calculated as shown in Table 20.

6. Discussion

- the use of diesel oil boilers for the heating of the main sport hall and the auxiliary building;

- the lack of any kind of active system for the indoor space cooling of the main sport hall;

- the availability of only one air-to-air heat pump for the cooling of only one specific room (the administrative office) in the auxiliary building;

- the considerably high U-factor values of all constructive elements, which, resulting, particularly for the main sport hall, to the configuration of a very cold indoor environment in winter;

- the high solar gain factor of the semi-transparent polycarbonate panels in the main sport hall, which, in combination with their large surfaces, contribute to the considerable increase of the indoor space temperature in summer;

- the absence of the kind of active system for the production or electricity or heat from renewables;

- the use electrical resistances and diesel oil for domestic hot water production;

- the use of ineffective lighting equipment.

7. Conclusions

Abbreviations (alphabetically)

| ANN : | Artificial Neural Network |

| ASHRAE : | American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers |

| BEMS : | Building Energy Management System |

| COP : | Coefficient Of Performance |

| DSM : | Demand Side Management |

| EER : | Energy Efficiency Ratio |

| EU : | European Union |

| GHE : | Geothermal Heat Exchangers |

| GHP : | Geothermal Heat Pumps |

| HVAC : | Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning |

| KPIs : | Key Performance Indicators |

| NESOI | New Energy Solutions Optimized for Islands |

| PPR : | polypropylene |

| RES : | Renewable Energy Sources |

| RHC : | Radiant Heating and Cooling |

| RUE : | Rational Use of Energy |

| SAVE : | Sustainable Actions for Viable Energy |

| TFM : | Transfer Function Method |

| VRV : | Variable Refrigerant Volume |

| W-SAHP : | Water Solar assisted Heat Pump |

| ZEB : | Zero Emission Building |

Nomenclature (in order of appearance)

| Tamb : | the ambient temperature |

| U: | the thermal heat transfer factor (the so-called U-factor) (in W/m2∙K) |

| hc : | the heat convection factor for ambient air horizontal flow with average velocity of 5 m/s (10 W/m2∙Κ) |

| hrw : | the heat radiation factor |

| cp : | the water specific heat capacity (4.187 kJ/kg∙K) |

| Tsw : | the water temperature in the water supply network |

| hfg : | the specific latent heat of water (2,441.7 kJ/kg at 25 οC) |

| dj : | the thickness of the structural material j of the opaque constructive element |

| kj : | the thermal conductivity factor of the structural material j of the opaque constructive element |

| hi : | the heat transfer factor from the inner space and towards the outer space ho (or conversely in summer) |

| ho : | the heat transfer factor towards the outer space (or conversely in summer) |

| ACH : | air changes per hour |

| Tin : | the indoor space temperature |

| : | the domestic hot water consumed mass flow rate |

| Thw : | the hot water required temperature |

| Pel : | the electrical power consumption in the heat pump |

| Qh : | the indoor space heating load |

| hw : | the thermal convection factor of still water, equal to 50 W/(m2∙K) |

| Qc : | the indoor space cooling load |

| Tsol : | the supplied water temperature from the solar collectors |

| Tst : | the stored water temperature in the heat storage tanks |

| Thw : | the required hot water temperature |

| ΝSC : | the solar collectors’ total number in the system |

| CSC : | the procurement price of one solar collector, adopted equal to 450 € |

| ΝSΤ : | the heat storage tanks’ number in the system, with storage capacity of 2000 L |

| CSΤ : | the procurement price of one 2000 L heat storage tank, adopted equal to 6000 € |

| ESC : | the annual heat demand coverage for domestic hot water production from the solar-combi system |

| ΤLP : | the solar-combi system’s life period, adopted equal to 15 years |

| cth : | the heat production specific cost from the solar-combi system |

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Katsaprakakis, D.A.; Papadakis, N.; Giannopoulou, E.; Yiannakoudakis, Y.; Zidianakis, G.; Kalogerakis, M.; Katzagiannakis, G.; Dakanali, E.; Stavrakakis, G.M.; Kartalidis, A. Rational Use of Energy in Sports Centres to Achieve Net Zero: The SAVE Project (Part A). Energies 2023, 16, 4040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive (EU) 2018/844 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 Amending Directive 2010/31/EU on the Energy Performance of Buildings and Directive 2012/27/EU on Energy Efficiency. 2018, 156. Available online: Https://Eur-Lex.Europa.Eu/Legal-Content/EN/TXT/?Uri=uriserv%3AOJ.L_.2018.156.01.0075.01.ENG (accessed on 14 February 2023).

- Consolidated Text: Directive 2012/27/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2012 on Energy Efficiency, Amending Directives 2009/125/EC and 2010/30/EU and Repealing Directives 2004/8/EC and 2006/32/EC (Text with EEA Relevance)Text with EEA Relevance; 2012; Vol. EUR-Lex-02012L0027-20230504-EN, 25 October.

- Law 4122/2013. Official Governmental Gazette 42A΄ / 19-2-2013. Energy Performance of Buildings – Harmonization with the Directive 2010/31/EU of the European Parliament and the Council and other clauses Available online:. Available online: https://www.kodiko.gr/nomothesia/document/70937/nomos-4122-2013 (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- International Energy Agency (IEA), Buildings – Analysis Available online:. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/buildings (accessed on 18 February 2023).

- Vakiloroaya, V.; Samali, B.; Fakhar, A.; Pishghadam, K. A Review of Different Strategies for HVAC Energy Saving. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 77, 738–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weerasinghe, A.S.; Ramachandra, T. Economic Sustainability of Green Buildings: A Comparative Analysis of Green vs Non-Green. Built Environ. Proj. Asset Manag. 2018, 8, 528–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baek, S.G. Plan for the Sustainability of Public Buildings through the Energy Efficiency Certification System: Case Study of Public Sports Facilities, Korea. Buildings 2021, 11, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Shen, C.; Yu, C.W.F. Building Energy Efficiency: Passive Technology or Active Technology? Indoor Built Environ. 2017, 26, 729–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaras, C.A.; Grossman, G.; Henning, H.-M.; Infante Ferreira, C.A.; Podesser, E.; Wang, L.; Wiemken, E. Solar Air Conditioning in Europe—an Overview. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2007, 11, 299–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Lombard, L.; Ortiz, J.; Pout, C. A Review on Buildings Energy Consumption Information. Energy Build. 2008, 40, 394–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostino, D.; Cuniberti, B.; Bertoldi, P. Energy Consumption and Efficiency Technology Measures in European Non-Residential Buildings. Energy Build. 2017, 153, 72–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, D. What Colour Is Your Building?: Measuring and Reducing the Energy and Carbon Footprint of Buildings; RIBA Publishing: London, 2019; ISBN 978-0-429-34773-3. [Google Scholar]

- Yezioro, A.; Capeluto, I.G. Energy Rating of Buildings to Promote Energy-Conscious Design in Israel. Buildings 2021, 11, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Wang, C.C.; Lee, C.L. A Framework for Developing Green Building Rating Tools Based on Pakistan’s Local Context. Buildings 2021, 11, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zero Energy Building Certification System Available online:. Available online: https://zeb.energy.or.kr/BC/BC00/BC00_01_001.do (accessed on 21 February 2023).

- Teni, M.; Čulo, K.; Krstić, H. Renovation of Public Buildings towards NZEB: A Case Study of a Nursing Home. Buildings 2019, 9, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, J.F.; Kranzl, L. Ambition Levels of Nearly Zero Energy Buildings (NZEB) Definitions: An Approach for Cross-Country Comparison. Buildings 2018, 8, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topriska, E.; Kolokotroni, M.; Melandri, D.; McGuiness, S.; Ceclan, A.; Christoforidis, G.C.; Fazio, V.; Hadjipanayi, M.; Hendrick, P.; Kacarska, M.; et al. The Social, Educational, and Market Scenario for NZEB in Europe. Buildings 2018, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azaza, M.; Eskilsson, A.; Wallin, F. Energy Flow Mapping and Key Performance Indicators for Energy Efficiency Support: A Case Study a Sports Facility. Energy Procedia 2019, 158, 4350–4356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayernik, J. Buildings Energy Data Book; US Department of Energy: United States, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- EU Building Stock Observatory - Data Europa EU Available online:. Available online: https://data.europa.eu/data/datasets/building-stock-observatory?locale=en (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- TM46: Energy Benchmarks | CIBSE Available online:. Available online: https://www.cibse.org/knowledge-research/knowledge-portal/tm46-energy-benchmarks (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- ECG 78 Energy Use in Sports and Recreation Buildings, Building Research Energy Conservation Support Unit - Publication Index | NBS Available online:. Available online: https://www.thenbs.com/PublicationIndex/documents/details?Pub=BRECSU&DocID=285163 (accessed on 19 February 2023).

- Trianti-Stourna, E.; Spyropoulou, K.; Theofylaktos, C.; Droutsa, K.; Balaras, C.A.; Santamouris, M.; Asimakopoulos, D.N.; Lazaropoulou, G.; Papanikolaou, N. Energy Conservation Strategies for Sports Centers: Part A. Sports Halls. Energy Build. 1998, 27, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hjortling, C.; Björk, F.; Berg, M.; Klintberg, T. af Energy Mapping of Existing Building Stock in Sweden – Analysis of Data from Energy Performance Certificates. Energy Build. 2017, 153, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energimyndighet, S. Energistatistik För Flerbostadshus 2008. Energy Statistics for Multi-Dwelling Buildings in 2008. 2009.

- Griffiths, A.J.; Bowen, P.J.; Brinkworth, B.J.; Morgan, I.R.; Howarth, A. Energy Consumption in Leisure Centres – a Comparative Study. Energy Environ. 1997, 8, 207–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaprakakis, D.A.; Dakanali, I.; Zidianakis, G.; Yiannakoudakis, Y.; Psarras, N.; Kanouras, S. Potential on Energy Performance Upgrade of National Stadiums: A Case Study for the Pancretan Stadium, Crete, Greece. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 1544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadineni, S.B.; Madala, S.; Boehm, R.F. Passive Building Energy Savings: A Review of Building Envelope Components. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2011, 15, 3617–3631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaprakakis, D.A.; Zidianakis, G.; Yiannakoudakis, Y.; Manioudakis, E.; Dakanali, I.; Kanouras, S. Working on Buildings’ Energy Performance Upgrade in Mediterranean Climate. Energies 2020, 13, 2159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudzińska, A. Efficiency of Solar Shading Devices to Improve Thermal Comfort in a Sports Hall. Energies 2021, 14, 3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrakakis, G.M.; Katsaprakakis, D.A.; Damasiotis, M. Basic Principles, Most Common Computational Tools, and Capabilities for Building Energy and Urban Microclimate Simulations. Energies 2021, 14, 6707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhee, K.-N.; Kim, K.W. A 50 Year Review of Basic and Applied Research in Radiant Heating and Cooling Systems for the Built Environment. Build. Environ. 2015, 91, 166–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, K.J.; Chou, S.K.; Yang, W.M. Advances in Heat Pump Systems: A Review. Appl. Energy 2010, 87, 3611–3624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tagliafico, L.A.; Scarpa, F.; Tagliafico, G.; Valsuani, F. An Approach to Energy Saving Assessment of Solar Assisted Heat Pumps for Swimming Pool Water Heating. Energy Build. 2012, 55, 833–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, T.T.; Bai, Y.; Fong, K.F.; Lin, Z. Analysis of a Solar Assisted Heat Pump System for Indoor Swimming Pool Water and Space Heating. Appl. Energy 2012, 100, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadzlin, W.A.; Hasanuzzaman, M.; Rahim, N.A.; Amin, N.; Said, Z. Global Challenges of Current Building-Integrated Solar Water Heating Technologies and Its Prospects: A Comprehensive Review. Energies 2022, 15, 5125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, W.; Spörk-Dür, M. Global Market Development and Trends in 2019 Detailed Market Data 2018. IEA 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Calise, F.; Figaj, R.D.; Vanoli, L. Energy and Economic Analysis of Energy Savings Measures in a Swimming Pool Centre by Means of Dynamic Simulations. Energies 2018, 11, 2182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaprakakis, D.Al. Comparison of Swimming Pools Alternative Passive and Active Heating Systems Based on Renewable Energy Sources in Southern Europe. Energy 2015, 81, 738–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsaprakakis, D.A. Computational Simulation and Dimensioning of Solar-Combi Systems for Large-Size Sports Facilities: A Case Study for the Pancretan Stadium, Crete, Greece. Energies 2020, 13, 2285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orejón-Sánchez, R.D.; Hermoso-Orzáez, M.J.; Gago-Calderón, A. LED Lighting Installations in Professional Stadiums: Energy Efficiency, Visual Comfort, and Requirements of 4K TV Broadcast. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantozzi, F.; Leccese, F.; Salvadori, G.; Rocca, M.; Garofalo, M. LED Lighting for Indoor Sports Facilities: Can Its Use Be Considered as Sustainable Solution from a Techno-Economic Standpoint? Sustainability 2016, 8, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, J.; Su, Z.; Yao, Y.; Fei, C.; Shamel, A. Investigation and 3E (Economic, Environmental and Energy) Analysis of a Combined Heat and Power System Based on Renewable Energies for Supply Energy of Sport Facilities. IET Renew. Power Gener. n/a. [CrossRef]

- Artuso, P.; Santiangeli, A. Energy Solutions for Sports Facilities. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2008, 33, 3182–3187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balaras, C.A.; Gaglia, A.G.; Georgopoulou, E.; Mirasgedis, S.; Sarafidis, Y.; Lalas, D.P. European Residential Buildings and Empirical Assessment of the Hellenic Building Stock, Energy Consumption, Emissions and Potential Energy Savings. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 1298–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Cooper, P.; Daly, D.; Ledo, L. Existing Building Retrofits: Methodology and State-of-the-Art. Energy Build. 2012, 55, 889–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luddeni, G.; Krarti, M.; Pernigotto, G.; Gasparella, A. An Analysis Methodology for Large-Scale Deep Energy Retrofits of Existing Building Stocks: Case Study of the Italian Office Building. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2018, 41, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ascione, F.; Bianco, N.; Stasio, C.D.; Mauro, G.M.; Vanoli, G.P. Addressing Large-Scale Energy Retrofit of a Building Stock via Representative Building Samples: Public and Private Perspectives. Sustainability 2017, 9, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, L.; Ruggeri, A.G. Optimal Design in Energy Retrofit Interventions on Building Stocks: A Decision Support System. In Appraisal and Valuation: Contemporary Issues and New Frontiers; Morano, P., Oppio, A., Rosato, P., Sdino, L., Tajani, F., Eds.; Green Energy and Technology; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; ISBN 978-3-030-49579-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tuominen, P.; Forsström, J.; Honkatukia, J. Economic Effects of Energy Efficiency Improvements in the Finnish Building Stock. Energy Policy 2013, 52, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielli, L.; Ruggeri, A.G.; Scarpa, M. Automatic Energy Demand Assessment in Low-Carbon Investments: A Neural Network Approach for Building Portfolios. J. Eur. Real Estate Res. 2020, 13, 357–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swan, L.G.; Ugursal, V.I. Modeling of End-Use Energy Consumption in the Residential Sector: A Review of Modeling Techniques. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 1819–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittarello, M.; Scarpa, M.; Ruggeri, A.G.; Gabrielli, L.; Schibuola, L. Artificial Neural Networks to Optimize Zero Energy Building (ZEB) Projects from the Early Design Stages. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- New Energy Solutions Optimized for Islands (NESOI) The “Sustainable Actions for Viable Energy” (SAVE) Project. Available online: https://www.nesoi.eu/content/save-greece.

- Minoan Energy Community The SAVE Project of NESOI. Available online: https://minoanenergy.com/en/%cf%84%ce%bf-%ce%ad%cf%81%ce%b3%ce%bf-save-%cf%84%ce%bf%cf%85-nesoi/.

- European Commission Clean Energy for EU Islands. Island Gamechanger Award. Available online: https://clean-energy-islands.ec.europa.eu/assistance/island-gamechanger-award.

- European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) ERA5 from the Copernicus Climate Change Service (C3S) Climate Date Store. ERA5 Hourly Data on Single Levels from 1959 to Present. https://cds.climate.copernicus.eu/#!/search?text=ERA5&type=dataset.

- Kreider, J. ; R., A.; . Curtiss, P. Heating and Cooling of Buildings, 3, Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Spitler, J.D. Load Calculation Applications Method, 2nd, *!!! REPLACE !!!*, Ed.; ASHRAE Editions: Atlanta, USA, 2014.

- Kteniadakis, M. Heat Transfer Applications, 2nd, ed.; Ziti Editions: Athens, Greece,, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 2009 ASHRAE Handbook—Fundamentals (SI Edition); American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers, Inc.: Atlanta, GA, USA, 2009.

- Stavrakakis, G.M.; T. , N.M.;. Markatos, N.C. Modified “closure” Constants of the Standard k-ε Turbulence Model for the Prediction of Wind-Induced Natural Ventilation. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2012, 33, 241–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stavrakakis, G.M.; Stamou, A.I.; Markatos, N.C. Evaluation of Thermal Comfort in Indoor Environments Using Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD). Das, B., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers Inc,, 2009; pp. 97–166. [Google Scholar]

- Official Hellenic Governmental Gazette Directive on Buildings’ Energy Performance - (Greek) 2367Β’/12-7-2017; 2017.

- Technical Chamber of Greece Technical Directive 20701-1/2017: Analytical national specifications for the buildings’ energy performance evaluation and the issuance of the energy performance certificate; Technical Chamber of Greece: Athens, Greece, 2017.

- Katsaprakakis, D.A.; Zidianakis, G. Optimized Dimensioning and Operation Automation for a Solar-Combi System for Indoor Space Heating. A Case Study for a School Building in Crete. Energies 2019, 12, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DIALux Evo - Online Photometric Tool. Available online: https://www.dialux.com/en-GB/.

- Fragkiadakis, I. Photovoltaic Systems, 4th, ed.; Ziti Editions: Athens, Greece, 2019. [Google Scholar]

| Energy Need | Requirement | Share | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|

| Space heating | High | 40-60% | due to large spaces, in cold climate |

| Space cooling | Medium. | 10-25% | due to large spaces, in hot climate |

| Lighting | Medium | 10-20% | evening activities & large indoor courts |

| Water heating | Medium | 10-20% | showers, pools, and saunas |

| Ventilation & air handling | Low | 1-5% | Requirement for fresh air in workout areas. |

| Refrigeration | Low | 0-5% | For cafeterias or snack areas. |

| Equipment | Low | 1-5% | gym equipment, scoreboards, sound systems. |

| Elevators & escalators | Low | 0-5% | If multi-storied. |

| Computing & office needs | Very Low | 0-1% | for administrative areas. |

| Source | CIBSE Energy Benchmark (TM46: 2008) [23] | ECON 78 (2001) [24] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Description | Sports Center | Local dry sports Center | |

| Electricity (kWh/m2) | Good | 64 | |

| Typical | 95 | 105 | |

| Gas (kWh/m2) | Good | 158 | |

| Typical | 330 | 343 | |

| Energy | Diesel oil | Electricity |

|---|---|---|

| Final heat demand (kWh) | 79,144.6 | 101,981.9 |

| Annual consumption (L / kWh) | 11,845.5 | 28,993.8 |

| Primary energy consumption (kWh) | 121,416.8 | 28,993.8 |

| Total primary energy consumption (kWh) | 217,640.5 | |

| Energy | Diesel oil | Electricity |

|---|---|---|

| Final heat demand (kWh) | 23,829.6 | 17,497.7 |

| Annual consumption (L / kWh) | 3,262.9 | 19,388.1 |

| Primary energy consumption (kWh) | 36,789.5 | 56,225.4 |

| Total primary energy consumption (kWh) | 93,014.9 | |

| Lighting use / power / consumption | Installed electrical power (kW) | Electricity consumption (kWh) |

|---|---|---|

| Outdoor perimeter floodlights | 1.25 | 4,627.6 |

| Main indoor sport hall | 12.86 | 11,313.9 |

| Auxiliary building | 3.91 | 1,467.7 |

| Total installed power | 18.02 | |

| Total electricity consumption | 17,409.2 | |

| Total primary energy consumption | 50,486.7 |

| Final energy use | Diesel oil (L) | Electricity (kWh) | Primary energy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (kWh) | (%) | |||

| Indoor space heating | 11,845.5 | 0.0 | 133,558.0 | 33.8 |

| Indoor space cooling | 0.0 | 28,993.8 | 84,082.0 | 21.3 |

| Hot water production | 3,262.9 | 19,388.1 | 93,014.7 | 23.5 |

| Lighting | 0.0 | 17,409.2 | 50,486.7 | 12.8 |

| Circulators and fans | 0.0 | 11,808.5 | 34,244.7 | 8.7 |

| Total | 15,108.4 | 77,599.6 | 395,386.1 | 100.0 |

| Structural element | U-factor (W/m2∙K) | Structural element | U-factor (W/m2∙K) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Main sport hall vertical surface: stone wool 8 cm panels | 0.38 | Auxiliary building vertical surface: brick walls with 7 cm stone wool insulation sheet |

0.34 |

| Main sport hall vertical surface: reinforced concrete with 7 cm stone wool insulation sheet |

0.40 | Auxiliary building vertical surface:reinforced concrete with 7 cm stone wool insulation sheet | 0.0 |

| Main sport hall roof:stone wool 8 cm panels | 0.39 | Auxiliary building roof:reinforced concrete with 7 cm stone wool insulation sheet | 0.40 |

| Windows | 0.95 | Doors | 1.2 |

| Indoor space conditioning mode |

Annual load | Annual load reduction | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existing operation | Proposed Operation | (kWh) | (%) | |

| Heating | 79,145 | 32,154 | 46,991 | 59.4 |

| Cooling | 101,982 | 39,181 | 62,801 | 61.6 |

| Total | 181,127 | 71,335 | 109,792 | 60.6 |

| Energy | Load – consumption | Saving | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existing operation | Proposed Operation | (kWh) | (%) | |

| Main sport hall (thermal zone 1) | ||||

| Heating & cooling load (kWh) | 143,484.6 | 56,515.2 | 86,969.4 | 60.6 |

| Diesel oil (L) | 7,928.8 | 0.0 | 7,928.8 | 100.0 |

| Electricity (kWh) | 25,273.8 | 13,122.1 | 12,151.7 | 48.1 |

| Primary energy (kWh) | 162,691.2 | 38,054.1 | 124,637.1 | 76.6 |

| Auxiliary building (thermal zone 2) | ||||

| Heating & cooling load (kWh) | 37,641.9 | 14,819.7 | 22,822.2 | 60.6 |

| Diesel oil (L) | 3,916.7 | 0.0 | 3,916.7 | 100.0 |

| Electricity (kWh) | 3,720.0 | 3,871.3 | -151.3 | -4.1 |

| Primary energy (kWh) | 54,949.4 | 11,226.9 | 43,722.4 | 79.6 |

| All indoor space | ||||

| Heating & cooling load (kWh) | 181,126.5 | 71,334.8 | 109,791.7 | 60.6 |

| Diesel oil (L) | 11,845.5 | 0.0 | 11,845.5 | 100.0 |

| Electricity (kWh) | 28,993.8 | 16,993.4 | 12,000.4 | 41.4 |

| Primary energy (kWh) | 217,640.5 | 49,281.0 | 168,359.5 | 77.4 |

| Solar radiation | Surface inclination with regard to the horizontal plane | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20ο | 25ο | 30ο | 35ο | 40ο | 45ο | 50ο | 55ο | 60ο | |

| Annually cumulative incident solar radiation (kWh/m2) | |||||||||

| Direct | 1060 | 1078 | 1088 | 1089 | 1083 | 1068 | 1045 | 1014 | 975 |

| Diffused | 696 | 684 | 670 | 653 | 634 | 613 | 590 | 566 | 539 |

| Reflected | 13 | 20 | 29 | 39 | 51 | 64 | 78 | 93 | 109 |

| Total | 1769 | 1783 | 1787 | 1782 | 1768 | 1744 | 1712 | 1672 | 1623 |

| Cumulative incident solar radiation from 15/10 to 15/3 (kWh/m2) | |||||||||

| Direct | 320 | 340 | 357 | 371 | 382 | 390 | 396 | 398 | 397 |

| Diffused | 203 | 200 | 196 | 191 | 185 | 179 | 172 | 165 | 157 |

| Reflected | 4 | 6 | 8 | 11 | 14 | 17 | 21 | 25 | 29 |

| Total | 527 | 545 | 560 | 572 | 581 | 586 | 589 | 588 | 584 |

| Collectors’ number | Tanks’ number | Initial heat production from solar collectors (kWh) |

Heat storage (kWh) |

Rejected heat percentage (%) |

Heat coverage from collectors (kWh) |

Heat demand coverage percentage from collectors (%) |

Collectors-tanks cost (€) | Heat production specific cost (€/kWh) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12 | 1 | 31.399,4 | 13.247,6 | 57,8 | 9.658,6 | 23,4 | 11.400 | 0,0787 |

| 16 | 1 | 39.826,9 | 15.161,7 | 61,9 | 11.100,7 | 26,9 | 13.200 | 0,0793 |

| 16 | 2 | 39.826,9 | 23.533,6 | 40,9 | 16.230,2 | 39,3 | 19.200 | 0,0789 |

| 20 | 2 | 47.899,2 | 26.699,0 | 44,3 | 18.506,2 | 44,8 | 21.000 | 0,0757 |

| 24 | 2 | 55.796,6 | 28.368,0 | 49,2 | 19.692,7 | 47,6 | 22.800 | 0,0772 |

| 24 | 3 | 55.796,6 | 34.285,2 | 38,6 | 21.846,9 | 52,9 | 28.800 | 0,0879 |

| 28 | 2 | 63.572,3 | 29.844,8 | 53,1 | 20.764,6 | 50,2 | 24.600 | 0,0790 |

| 28 | 3 | 63.572,3 | 36.496,9 | 42,6 | 23.354,8 | 56,5 | 30.600 | 0,0873 |

| 32 | 3 | 71.276,3 | 38.098,0 | 46,5 | 24.418,2 | 59,1 | 32.400 | 0,0885 |

| 36 | 3 | 78.941,3 | 39.571,9 | 49,9 | 25.449,0 | 61,6 | 34.200 | 0,0896 |

| 40 | 3 | 86.579,5 | 40.661,9 | 53,0 | 26.166,5 | 63,3 | 36.000 | 0,0917 |

| 40 | 4 | 86.579,5 | 46.808,9 | 45,9 | 27.129,1 | 65,6 | 42.000 | 0,1032 |

| Energy | Load – consumption | Saving | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existing operation | Proposed Operation | (kWh) | (%) | |

| Heat demand for hot water production (kWh) | 41.327,3 | 41.327,3 | 0,0 | 0,0 |

| Diesel oil (L) | 3.262,9 | 0,0 | 3.262,9 | 100,0 |

| Electricity (kWh) | 19.388,1 | 7.323,4 | 12.064,7 | 62,2 |

| Primary energy (kWh) | 93.014,9 | 21.237,8 | 71.777,1 | 77,2 |

| Existing operation | Proposed operation | Power drop | Electricity saving | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Power (W) | Electricity (kWh) | Power (W) | Electricity (kWh) | (W) | (%) | (kWh) | (%) | |

| Outdoor perimeter lighting | 1,648 | 4,627.6 | 500 | 1,334.9 | 1,148 | 69.7 | 3,292.7 | 71.2 |

| Main sport hall lighting | 12,864 | 11,313.9 | 5,880 | 5,171.5 | 6,984 | 54.3 | 6,142.4 | 54.3 |

| Auxiliary building indoor lighting | 3,914 | 1,467.7 | 2,028 | 760.5 | 1,886 | 48.2 | 707.2 | 48.2 |

| Total | 18,426 | 17,409.2 | 8,408 | 7,266.9 | 10,018 | 54.4 | 10,142.3 | 58.3 |

| Circulators of the indoor space conditioning hydraulic network | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main sport hall | Auxiliary building | Total | |

| Nominal electrical power input (W) | 81.7 | 143.0 | |

| Annual operating time (h) | 1738 | 1317 | |

| Annual electriciy consumption (kWh) | 142.0 | 188.3 | 330.3 |

| Hydronic units fans | |||

| Main sport hall | Auxiliary building | Total | |

| Nominal electrical power input (W) | 4026 | 306 | |

| Annual operating time (h) | 1738 | 1317 | |

| Annual electriciy consumption (kWh) | 6997.2 | 403.0 | 7400.2 |

| Circulators of the domestic hot water distribution hydraulic network | |||

| Solar collectors | Heat pump | Total | |

| Nominal electrical power input (W) | 49 | 81.7 | |

| Annual operating time (h) | 1289 | 731 | |

| Annual electriciy consumption (kWh) | 63.2 | 59.7 | 122.9 |

| Energy use | Electricity consumption (kWh) |

|---|---|

| Indoor space conditioning | 16,994 |

| Hot water production | 7,323 |

| Lighting | 7,267 |

| Circulators of the conditioning system | 330 |

| Hydronic units’ fans | 7,400 |

| Circulators of the hot water production system | 123 |

| Total | 39,437 |

| Load / energy use | Load / Primary energy consumption (kWh) | Saving | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existing operation | Proposed operation | (kWh) | (%) | |

| Indoor space conditioning load | 181,127 | 71,335 | 109,792 | 60.6 |

| Primary energy for indoor space conditioning | 217,640.5 | 49,281.0 | 168,359.5 | 77.4 |

| Primary energy for domestic hot water production | 93,014.9 | 21,237.8 | 71.777,1 | 77,2 |

| Primary energy for lighting | 50,486.7 | 21,074.0 | 29,412.7 | 58.3 |

| Primary energy in circulators and fans | 34,244.7 | 22,774.9 | 11,469.8 | 33.5 |

| Photovoltaic plant primary energy production | 0 | -116,565.5 | 116,565.5 | - |

| Total annual primary energy consumption | 395,387 | -2,198 | 397,585 | 100.6 |

| Energy sources | Consumption (L or kWh) | Annual saving | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Existing operation | Proposed operation | (L or kWh) | (%) | |

| Diesel oil | 15,108 | 0 | 15,108 | 100.0 |

| Electricity | 77,600 | 39,437 | 38,163 | 49.2 |

| Budget component | Cost (€) |

|---|---|

| Insulation and stone wool panels | 299,495 |

| Installation of new openings | 35,697 |

| Indoor space active conditioning systems | 226,654 |

| Solar-combi system | 101,970 |

| Natural and artificial lighting interventions | 123,195 |

| Building Energy Management System (BEMS) | 33,656 |

| Reactive power compensation panel | 4,487 |

| Photovoltaic plant | 127,846 |

| Total | 953,000 |

| Energy source | Procurement price (€/kWh - €/L) |

Existing theoretical operation | New expecting operation | Economic saving | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual consumption (kWh - L) |

Annual procurement cost (€) |

Annual consumption (kWh - L) |

Annual procurement cost (€) |

(€) | (%) | ||

| Electricity | 0.25 | 77,600 | 19,400 | 39,437 | 1,479 | 17,921 | 92.4 |

| Diesel oil | 1.2 | 15,108 | 18,130 | 0 | 0 | 18,130 | 100.0 |

| Total | 37.530,0 | 1.478,9 | 36.051 | 96.1 | |||

| Energy source | CO2 specific emissions (kg/kWh) | Existing operation | Proposed operation | Electricity & primary energy annual saving (kWh) | CO2 emissions drop | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Annual consumption (kWh – L) |

Primary energy (kWh) | Annual consumption (kWh – L) |

Primary energy (kWh) | (kg) | (%) | |||

| Electricity | 0.989 | 77,600 | 225,038.8 | -758 | -2,197.3 | 227,236.2 | 77,495.4 | 101.0 |

| Diesel oil | 0.264 | 15,108 | 170,347.2 | 0 | 0,0 | 170,347.2 | 44,971.7 | 100.0 |

| Total | 395,386.1 | -2,197.3 | 397,583.4 | 122,467.0 | 100.6 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).