1. Introduction

Falls are the critical issue among vulnerable populations including older adults, stroke survivors, Parkinson’s patients and individuals with other neurological disorders [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. For example, up to one in three older adults fall at least once a year while this figure is 40-58% for post-stroke individuals (within 1 year of their stroke) and 45-68% for people with Parkinsonism [

8,

9,

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Due to slower reaction speeds and lower bone mineral density [

15], these frail populations are prone to severe injuries that can lead to death or constant nursing care with large costs that can impact both individuals and national social security systems [

15,

16,

17]. Falls prevention should be thus prioritised especially for vulnerable populations. Among various causes, tripping has been identified as the leading cause accounting for up to 53% of the entire falls incidences [

18,

19].

Tripping can be defined as the unintentional swing foot’s contact with the walking surface or an object on it with sufficient momentum that destabilises the walker [

20]. During the swing phase of the gait cycle, the critical event in relation to tripping risk is minimum foot clearance (MFC), determined as the local minimum swing toe vertical displacement during the mid-swing phase [

21,

22]. Tripping at MFC has the high risk of forward balance loss and an associated fall because (i) low vertical clearance increases the likelihood of swing foot contact, (ii) swing foot travels at near-maximum speed generating the large impact in case of tripping at MFC and (iii) both feet stance does not provide the ideal supporting base against balance loss [

22,

23,

24,

25].

Essentially, tripping prevention can be achieved if sufficient vertical displacement is provided at MFC [

26]. There are various intervention techniques aiming to increase MFC height such as use of the special shoe-insole, biofeedback training and exercise intervention. The focus of our current research is to predict MFC heights in advance so that this can be incorporated into assistive devices (e.g. active exoskeletons) for actuation assistance when necessary [

27,

28,

29,

30]. For development of such technology, MFC height estimation should be based on wearable sensors such as inertial measurement units (IMUs) [

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37] and undertaken well in advance for the mechanical device to take action. Our previous work showed that MFC timing can be predicted from toe-off characteristics with a mean absolute error of 0.07 seconds [

38].

In our current study, we have applied IMUs to record toe-off characteristics described by 3-axial accelerations and angular velocities. The objective is to find out whether kinematics data following toe-off could be utilised for the classification of MFC heights into categories (e.g., high, medium, low). Using the MFC characteristics in [

21], the current study attempted to classify MFC into the following three sub-categories: (i) lower than normal (MFC < 1.5cm), (ii) safe range (1.5cm < MFC < 2cm), and (iii) well-above the safety requirement (MFC > 2cm)

2. Machine Learning Overview

Machine learning algorithms can extract and recognise features using mathematical relationships between different variables in the sample space [

38]. Collection of mathematically related feature variables in a sample space forms the sample data for development of training and testing algorithms. Machine learning applications in gait and neurological studies, have created intrinsic understanding in previously under discovered areas, giving rise to wider applications involving neurological processes relating human gait from recognition of intention to physical locomotion [

39,

40,

41]. In the current study, a supervised machine learning algorithm was used to make predictions on new unlabelled data points. K-Nearest Neighbour (KNN) uses distance measures to find K closest neighbours to a test dataset. Low MFC is associated with tripping falls [

21]; therefore, our goal was to use machine learning algorithm to classify MFC heights into lower than normal, safe range and above safe range categories.

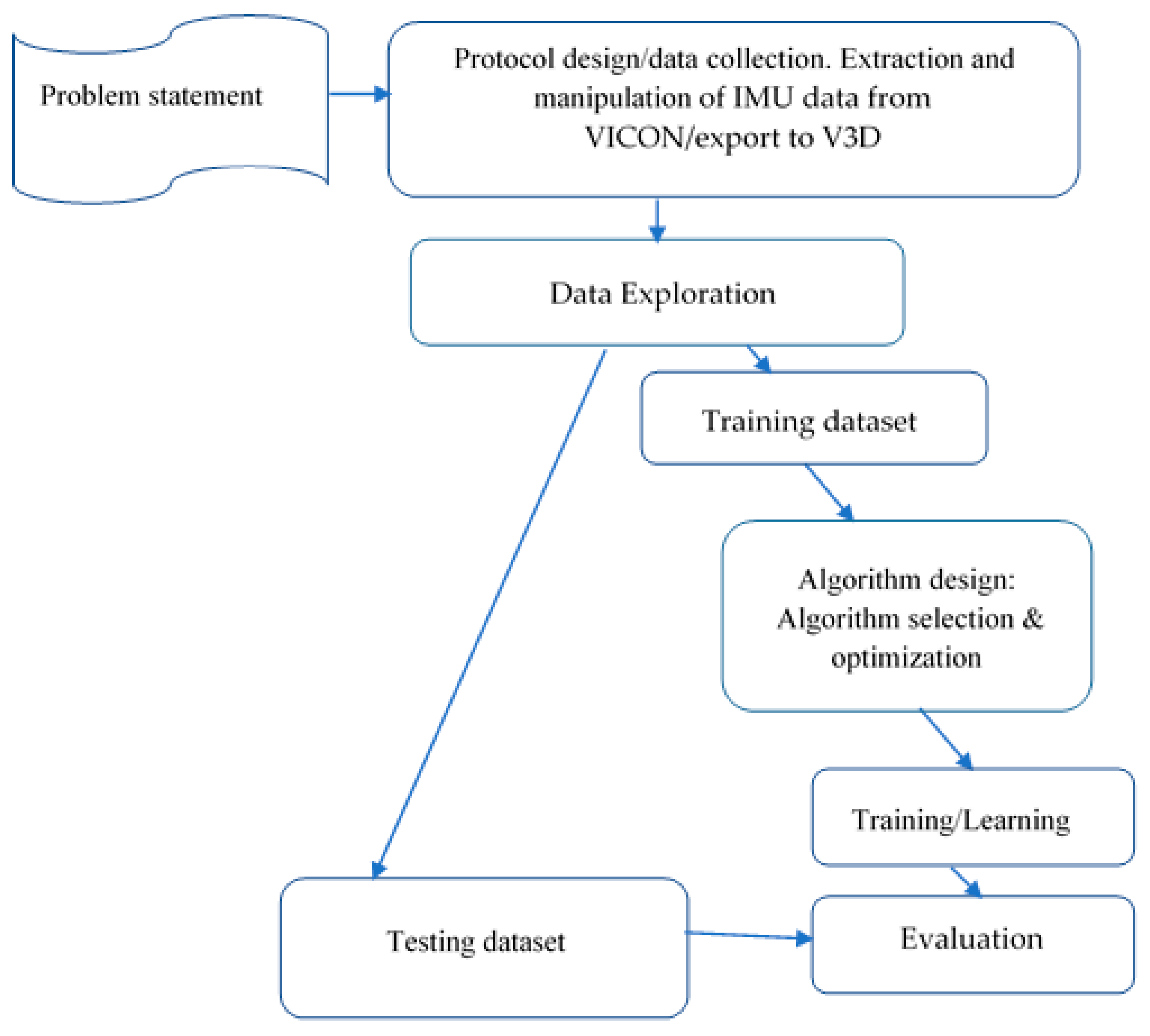

Figure 2.

Process diagram for the implementation of our ML algorithm, problem statement, algorithm development, training and performance evaluation.

Figure 2.

Process diagram for the implementation of our ML algorithm, problem statement, algorithm development, training and performance evaluation.

3. Data Collection

3.1. Participants and Protocols

Six healthy young adults were recruited for the current research from the university volunteers. To be included in the study, participants were required to be healthy, capable of walking on the treadmill for 30 minutes without a break, free from injuries that affect their walking patterns and no previous history of injurious falls for at least for the past two years. The entire experimental protocol was explained by the researchers and informed consent form approved and mandated by Victoria University Research Ethics Committee was voluntarily signed by the participants prior to participation

Gait testing was conducted on the treadmill (AMTI) for 5 minutes at 4km/h, which was considered to be the reasonable preferred pace for healthy young individuals [

41]. Vicon Bonita system (Nexus 2.12.1) with 10 cameras were utilised to track reflective markers at 200Hz, attached to the heel (the proximal end of the shoe) and the toe (the most anterior superior surface of the shoe). Low-pass Butterworth filter (6Hz) was applied to the obtained position data prior to analysis. Based on the kinematic conventions [

42], toe-off and heel contact were first computed to define the swing phase. MFC was identified as the local minimum vertical displacement of the toe during the mid-swing phase from toe-off but when the clear local minimum was absent the alternative definition was applied utilising maximum horizontal velocity of swing toe [

43].

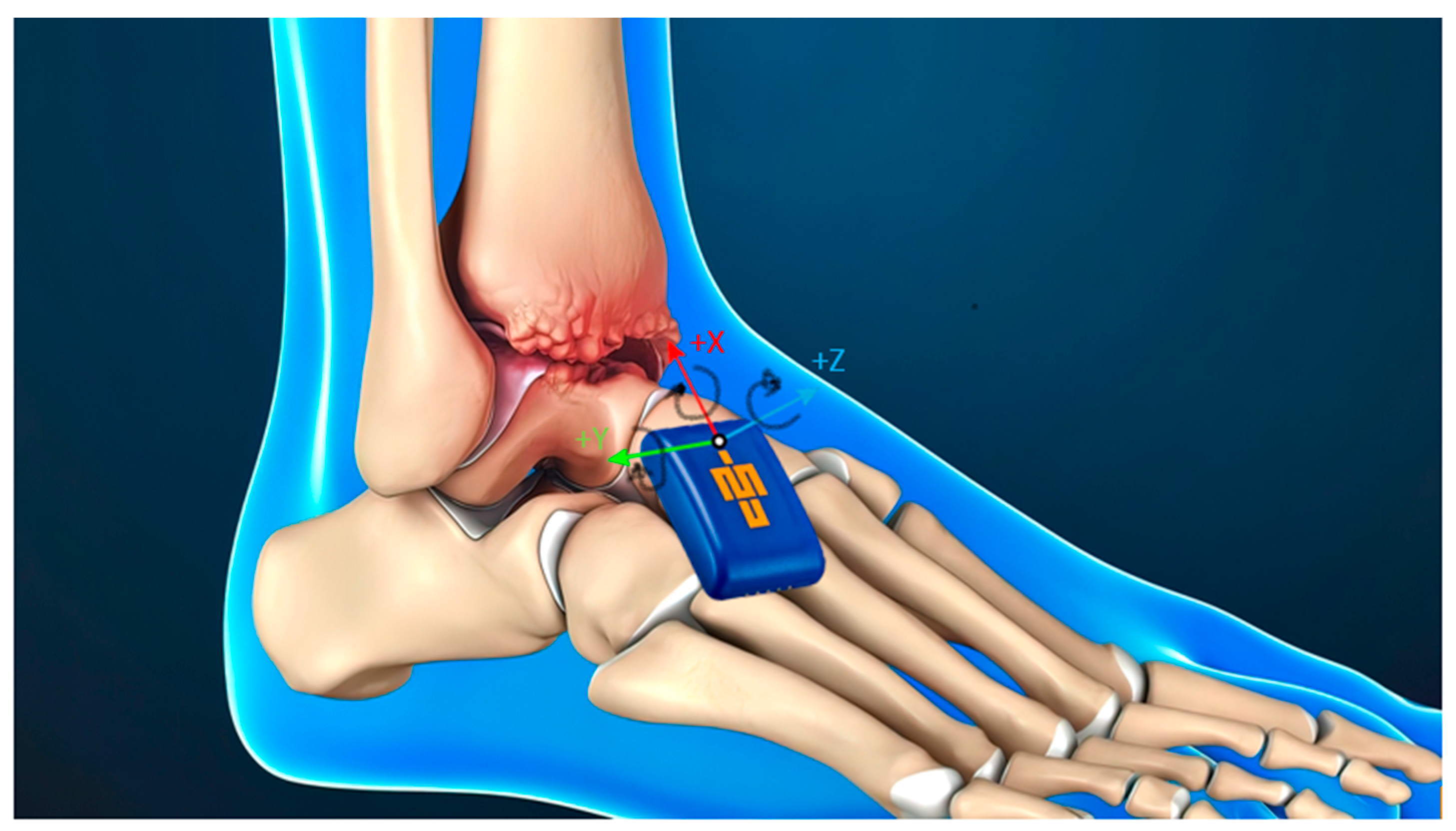

Figure 3.

IMU (Nexus, Trident) attached to the midfoot, tri-axial linear accelerations and angular velocities indicated by arrows. X is anterior-posterior axis, Y is Medio-lateral and Z is the vertical.

Figure 3.

IMU (Nexus, Trident) attached to the midfoot, tri-axial linear accelerations and angular velocities indicated by arrows. X is anterior-posterior axis, Y is Medio-lateral and Z is the vertical.

As illustrated in Figure 3, IMU (Nexus, Trident) was attached to the mid-foot section to record various foot-segment based kinematic data (200Hz) but for the current study, tri-axial linear accelerations (AccX, AccY,AccZ) and angular velocities (GyroX, GyroY, GyroZ) were obtained for machine learning application. The overall goal of the study was to predict in which category (

Table 1) upcoming MFC would be classified based on the 5 consecutive frames from toe-off comprising 0.025s kinematic information from toe-off. MFC categories employed in the current study are described in

Table 1, determined by the previous studies indicating the average MFC for young adults to be about 1.5cm (R1), slightly above the average up to 2cm, (R2) and minimum risk of tripping (R3) as above 2cm [

20,

21,

22,

45].

3.2. Data Exploration

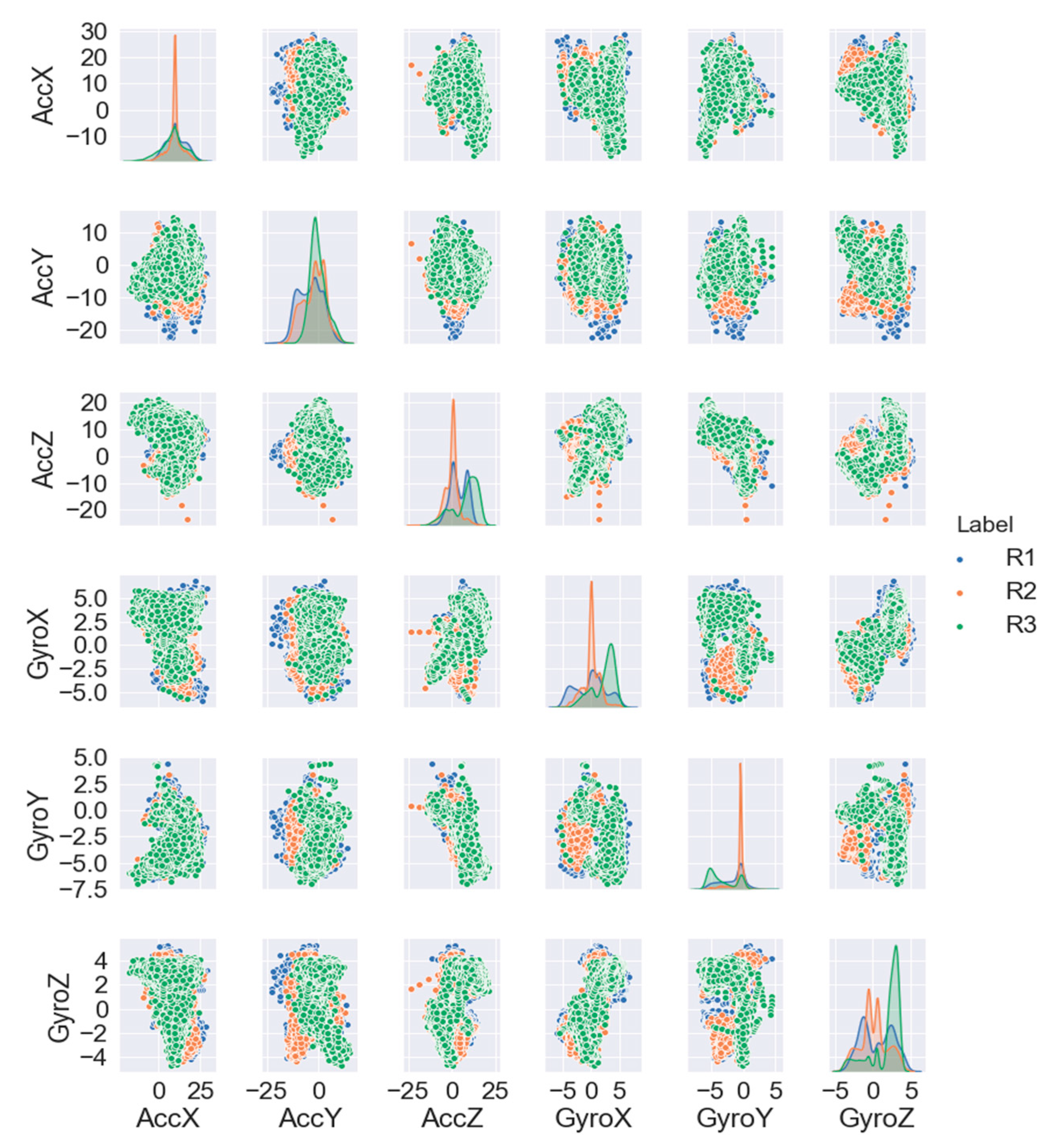

The selected features (i.e. tri-axial linear accelerations, angular velocities) were plotted with Seaborne pair plot [

46] and showed non-linearly separable classes. The average values are indicated in

Table 2

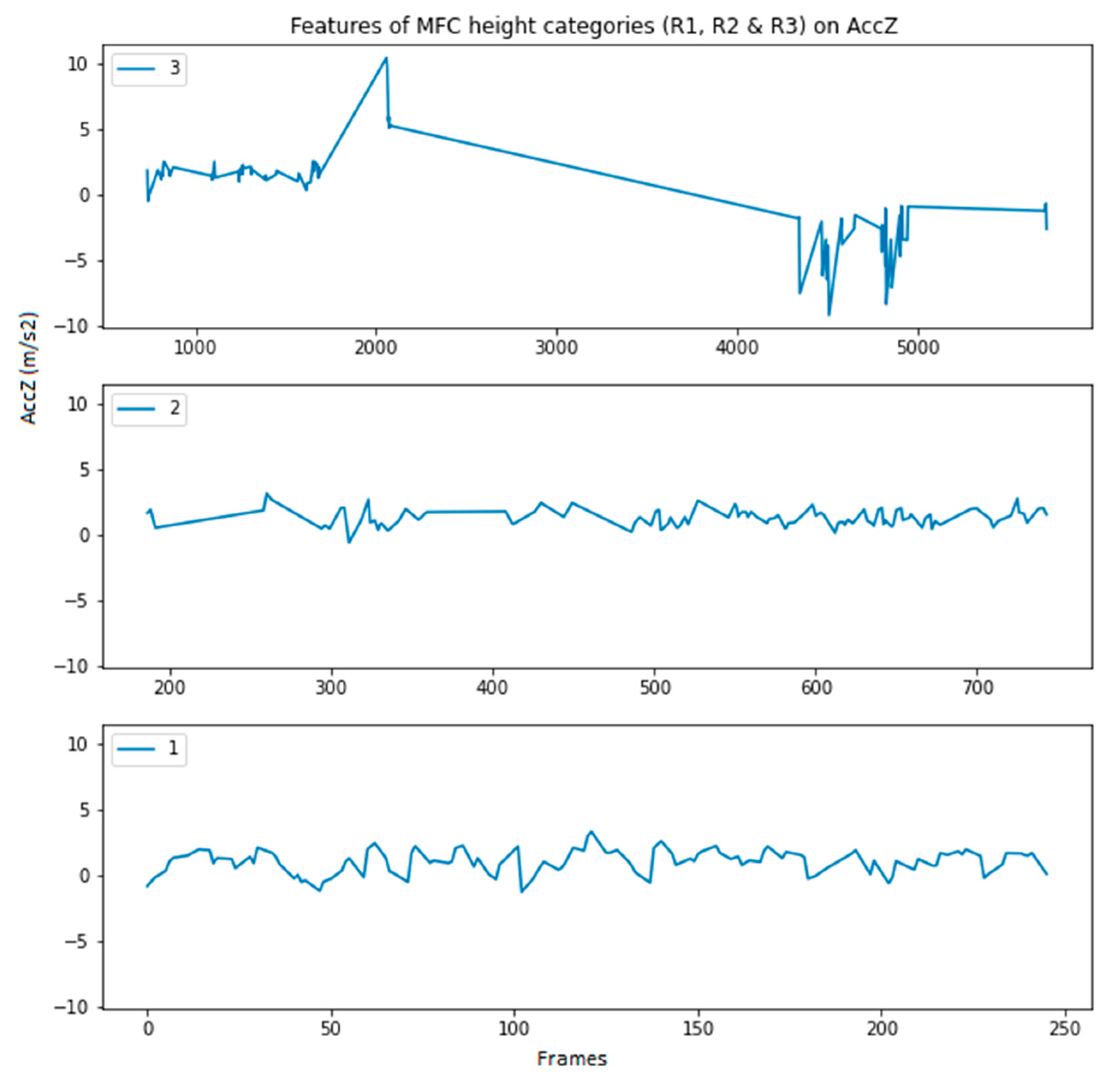

Zoomed Z-axis component of the acceleration and angular velocity on the three categories of the MFC heights, distinctive patterns illustrated in Figure 2a,b argues to the range of our classification

Figure 2.

a: Zoomed Z-axis of linear acceleration on R1, R2 and R3 graphically compared.

Figure 2.

a: Zoomed Z-axis of linear acceleration on R1, R2 and R3 graphically compared.

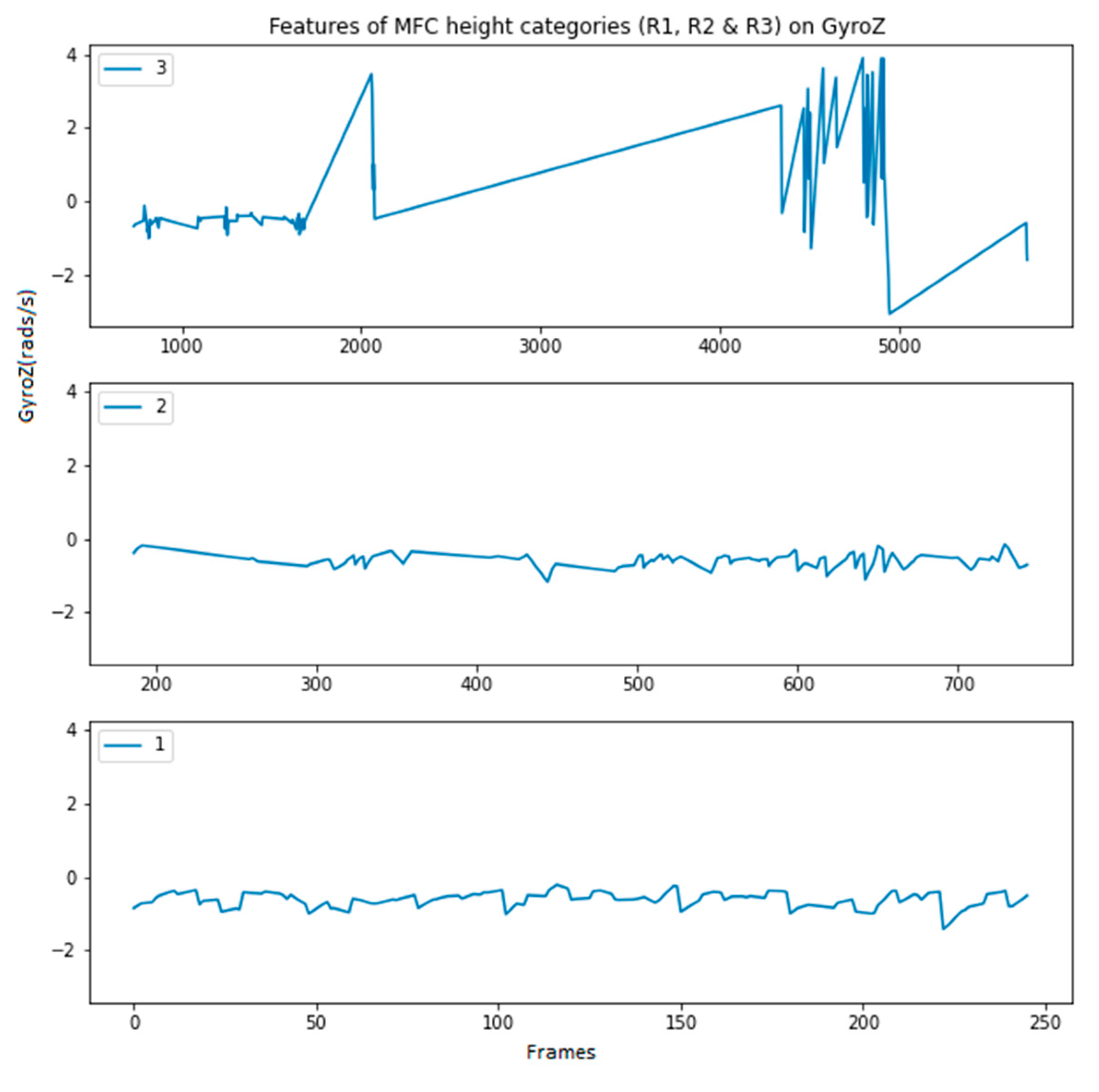

Figure 2.

b: Zoomed Z-axis of angular velocity on R1, R2 and R3 graphically compared.

Figure 2.

b: Zoomed Z-axis of angular velocity on R1, R2 and R3 graphically compared.

3.3. Model Selection and Algorithm Design

K-Nearest Neighbour (KNN) and Random-Forest were selected because our dataset variables are non-linearly separable as can be seen in Figure 3. Additionally, the characteristic attributes of each data point in Figure 3 formed a category that is assigned a class and the data points of any particular class are neighbors of each other.

Figure 3.

Pair plot correlation of the feature variables (linear acceleration and angular velocity) on R1 (blue), R2 (orange) and R3 (green).

Figure 3.

Pair plot correlation of the feature variables (linear acceleration and angular velocity) on R1 (blue), R2 (orange) and R3 (green).

In KNN, each instance is categorised as a vector of numbers in an n-dimensional Euclidean space. To find the class to which an unknown data point is a neighbor the Euclidean distance is measured as the true straight-line between two points. All instances, therefore, correspond to points in an n-dimensional Euclidian space and the distance between instances

is

Given k nearest neighbours, the optimum value is picked for best prediction of either R1, R2 or R3 MFC height category. In Random-Forest, an ensemble of many decision trees is designed to overcome overfitting problems associated with decision trees by bootstrap aggregation or bagging. Given a random-forest tree Tb (for b = 1 to B) to the bootstrap sample Z* of size N from training data,

To make a prediction at a new point:

Regression:

Classification:

majority vote

where is the class of prediction of the bth random-forest tree.

These methods have proven success in several use cases in gait classification and identification [

47,

48,

49]. Both KNN and Random-Forest were, therefore, selected for our study and as both were useable for regression or classification problems and belonged to supervised machine learning algorithms

3.3.1. Hyper Parameter Tuning and Optimization

Each variable data (

Table 2) was reshaped for scaling, using RobustScaler. GridSearch cross validation was used to determine the optimal list of parameters for our machine learning problem. Fitting 5 folds and iterating for 28 candidates, totalling 140 fits, the best parameters for KNN was tested with 7 neighbours 2 distances, 2 weights and 5 cross validations, and the best parameters proposed were ({'n_neighbors': 13, 'p': 2, 'weights': 'distance'}). Similarly, Random-Forest best parameters suggestion with GridSearach was ({'criterion': 'gini', 'max_depth': 8, 'max_features': 'sqrt', 'n_estimators': 400, 'random_state': 42}).

The feature variables (accelerometer and angular velocity) were separately investigated to determine individual contribution to the prediction of the MFC heights. The results are shown in table 4a and 4b.

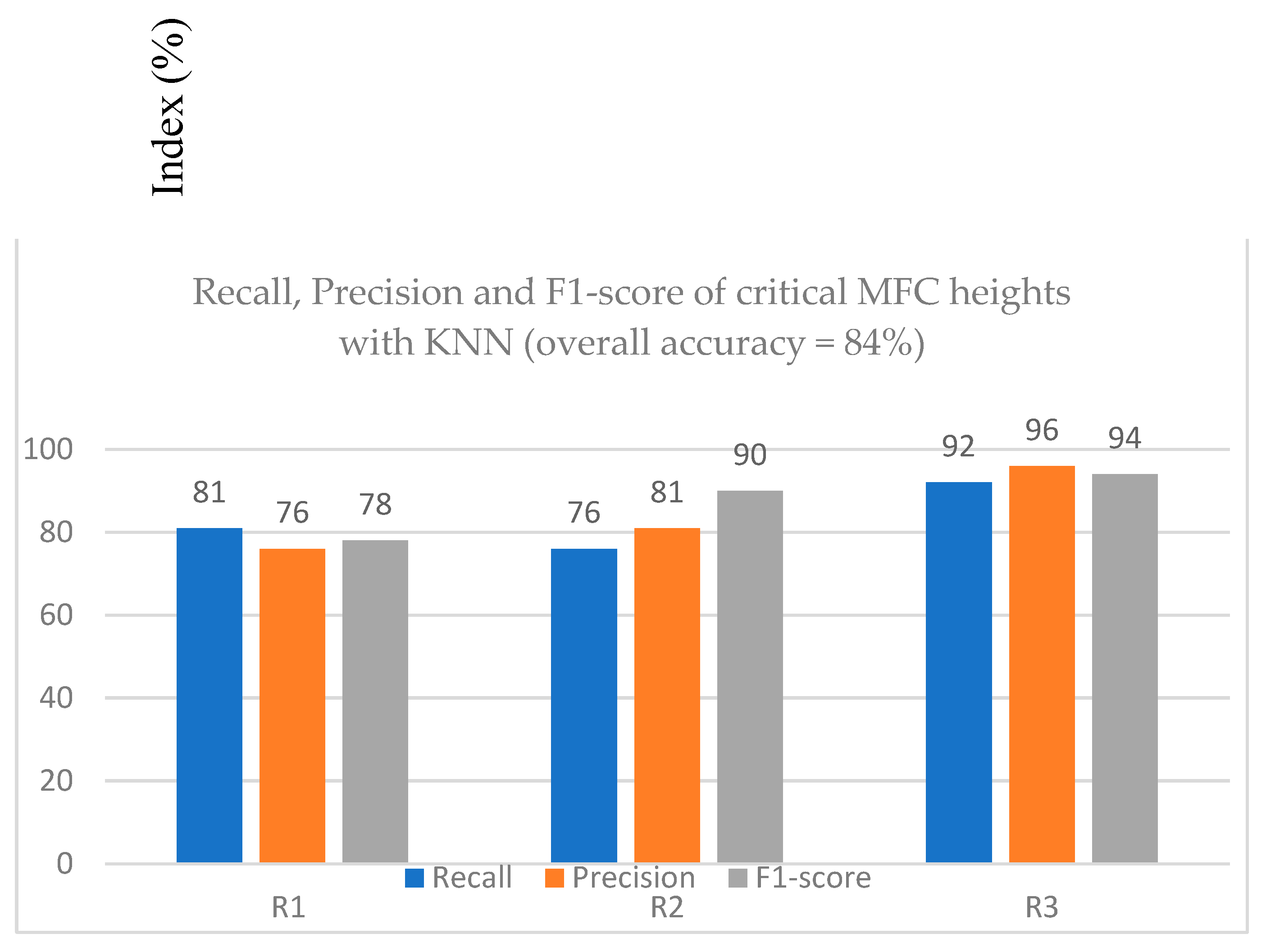

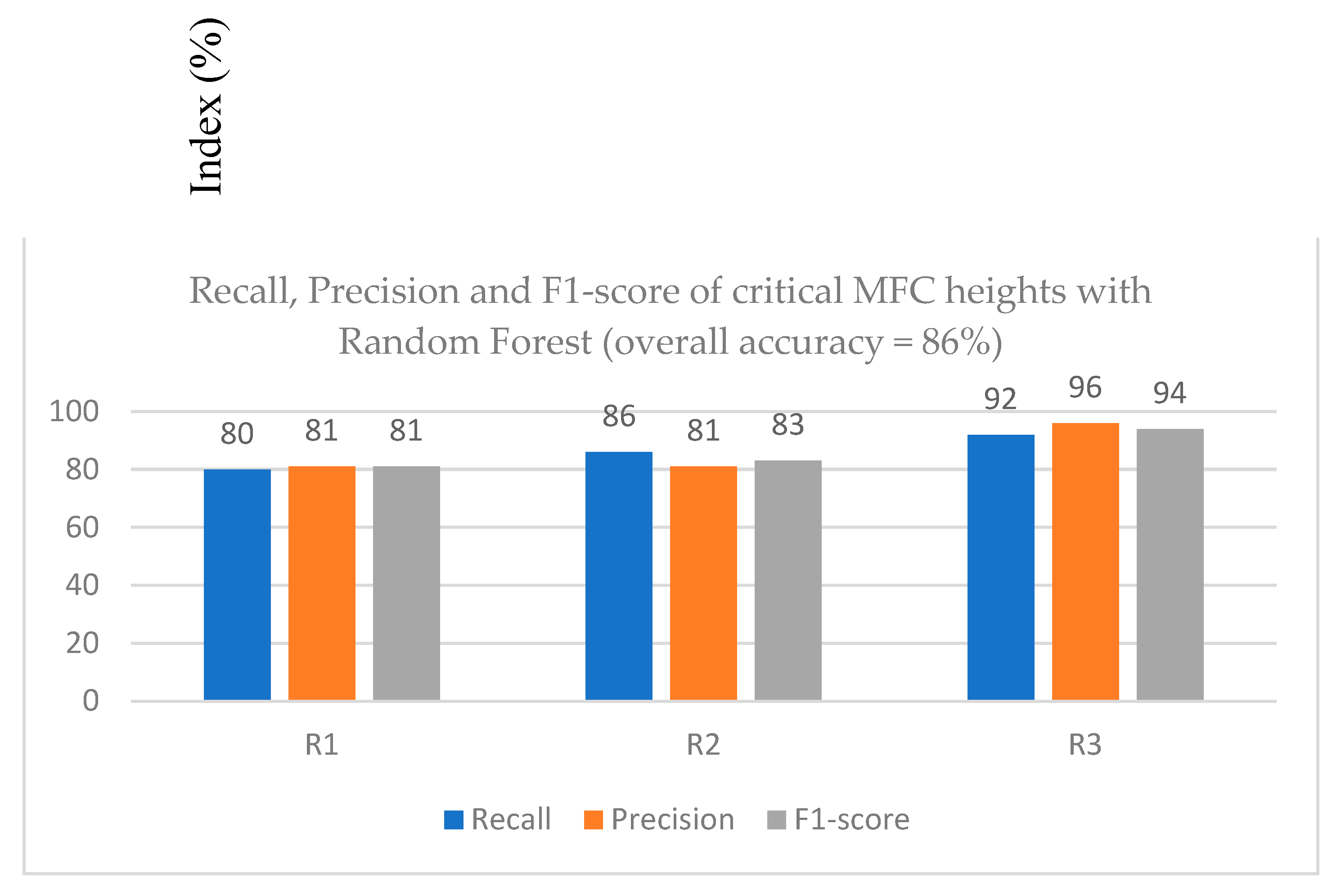

4. Results

Figure 2 depicted the Z-axis variables of the critical MFC heights. MFC height in the range of the critical threshold based on the young population’s lower end of the normal range (i.e. mean – SD) indicated the Z-axis component of the kinematic variable is highly unstable with increased tripping risk at MFC. Figure 3 is the correlation plot that helped us visualise the relationship between the variables. Figure 4a and 4b are adapted from the confusion matrix for KNN and Random-Forest with close matched accuracies. Higher accuracies are prioritised in ML modelling, while precision and recall rate are more valuable for better data classification. For example, high recall signifies good coverage, i.e. the percentage of tags the classifier predicted for a given label out of the total number of tags it should have predicted for that given label [

50]. Both precision and recall are at acceptable levels supported by the F1 Score.

Figure 4.

a. Performance evaluation of KNN algorithm showing average accuracy of 84 percent with high recall and F1-scores.

Figure 4.

a. Performance evaluation of KNN algorithm showing average accuracy of 84 percent with high recall and F1-scores.

A particular MFC height is predictable with 84 percent accuracy, suitability for business case related by high recall rate of 92 percent on R3 which has the highest risk of fall.

Figure 4.

b. Performance evaluation of Random-Forest with average accuracy of 86 percent with high recall and F1-scores.

Figure 4.

b. Performance evaluation of Random-Forest with average accuracy of 86 percent with high recall and F1-scores.

Performance result with Random-Forest is similar to the KNN algorithm with slight improvement in overall accuracy and recall. Random-Forest randomly selects a subset of features that are used as candidates at each split. This protocol automatically prevents the multitude of decision trees from relying on the same set of features, solving problems of overestimated correlations by avoiding a correlation of the individual trees. Each tree then draws a random sample of data from the training dataset when generating its splits, which further introduces an element of randomness and prevents the individual trees from overfitting the data. The uniformly generated weighted average on R1, R2 and R3 with both algorithms showed that each class was equally considered in its calculation of the metrics and had equal impact on the average score for each of those metrics (

Table 3)

Table 3.

Performance Summary of KNN and Random-Forest.

Table 3.

Performance Summary of KNN and Random-Forest.

| Algorithm |

Accuracy score (%) |

Weighted average (%) |

Run time |

| KNN |

84 |

83 |

0.39 seconds, at K =12 |

| Random Forest |

86 |

86 |

13.98 seconds, with 800 estimators and max depth of 8 |

Table 4.

a. Comparison of prediction accuracies using linear acceleration and angular velocity as separate features on Random Forest and KNN.

Table 4.

a. Comparison of prediction accuracies using linear acceleration and angular velocity as separate features on Random Forest and KNN.

| Feature Variables |

Random Forest (% accuracy) |

KNN (% accuracy) |

| Acceleration (X,Y,Z) |

67 |

65 |

| Gyro meter(X,Y,Z) |

75 |

74 |

| Combined Acceleration and Gyro meter (X,Y,Z) |

86 |

84 |

Table 4.

b. Comparison of individual axial features (acceleration and angular velocity) on prediction with Random Forest and KNN.

Table 4.

b. Comparison of individual axial features (acceleration and angular velocity) on prediction with Random Forest and KNN.

| ML Algorithm |

Percentage accuracies of individual features to predict MFC height |

| |

AccX |

AccY |

AccZ |

GyroX |

GyroY |

GyroZ |

| Random Forest |

40 |

43 |

51 |

51 |

46 |

48 |

| KNN |

41 |

45 |

55 |

56 |

51 |

55 |

Table 4a showed the angular velocity had more positive effect on the predicted MFC heights than the linear acceleration and MFC height are best predicted with multiple features. Table 4b indicated that the vertical acceleration and the x and z axis of the angular velocities are more significantly related to the MFC height than the other kinematic variables.

4. Discussion

Minimisation of tripping risks has been one of the central issues for falls prevention and providing sufficient swing foot-ground clearance at MFC has been a key consideration while applying an intervention. For the real-time technology as part of the intelligent system, one effective approach is to use feed-forward prediction of upcoming MFC as early as the initiation of swing phase at toe-off. For healthy young adults, MFC usually takes place approximately around 50% of the swing phase, 0.2s-0.3s after toe-off [

51]. It can be interpreted that ‘prediction and actuation’ should, in this example, occur within that time limit. In the current study, KNN successfully classified MFC into the three categories at 84% accuracy within 0.025s, suggesting the sufficient reliability and feasibility of our machine learning outputs to be incorporated into intelligent assistive device. Previous methods for MFC height estimation based on double-integration of vertical acceleration [

24] is useful for measurement outside the laboratory environments, but our machine learning based prediction is the first attempt to devise intelligent active exoskeletons to increase MFC height. We have previously demonstrated toe-off kinematics can be used to predict MFC timing [

38] – in this research we have applied toe-off kinematics for the real-time feedforward prediction of MFC heights.

Machine learning approaches are the emerging technique to classification and evaluation of gait patterns based on large data volumes, considered to be the mainstream analytical method in future and replacing conventional complex manual customised mathematical programming. The prediction of a future gait event can be incorporated into assistive device to become intelligent real-time systems to augment human ambulation. In machine learning use cases, we have employed KNN and Random Forest for gait classification. Both of our models successfully classified MFC height into the three subcategories from toe-off information at high accuracies. Nevertheless, a caution is required for machine learning algorithms to provide feedforward control for a powered assistive device in a timely manner. While Random-Forest showed better performance in accuracy, KNN may be the preferred option considering the time taken for prediction to activate assistive device at MFC based on a preceding toe-off event. High recall and high precision cannot be compromised to ensure correct classification of MFC heights for the populations at critically high and moderate tripping risks, respectively [

50]. Further collection of the data is essential in feeding the developed algorithms to improve performance before equipping it into assistive device for people.

In addition to the essential data feeding, there are some other fundamental concerns to overcome for practical application into assistive device as intelligent system. In the current proof-of-concept research, data of healthy young participants were selected to build the algorithms but, prediction of the tripping risk is more useful for vulnerable populations such as older adults, stroke survivors, people with Parkinson’s disease and other pathological conditions. Gait patterns of the high tripping risk are often clearly different from the healthy young, implying that the currently developed algorithms need fine-tuning accounting for each gait pathology. MFC classification requires reconsideration in that further sub-divisions of the lower end (e.g. less than 0.5cm, 1cm etc) should be tested to examine the hazardous risk rather than MFC below 1.5cm categorisation.

After data feeding from various populations to achieve certain reliability in recognising hazardous MFC heights, the developed intelligent systems can be incorporated into ankle active exoskeleton devices to directly control ankle motion to increase MFC and prevent the risk of tripping falls. Kubota et al. [

52] introduced the active ankle exoskeleton based on hybrid assistive limb (HAL) technology, which operates ankle dorsiflexion-plantarflexion motion based on efferent neural signals. In another word, HAL technology utilises intention to make movements to precisely control exoskeletons and reproduce intended movements, known to enhance motor control functions and improve neurological disorders [

53,

54]. Ankle-HAL technology was developed for rehabilitation to focus on joint motion training by users’ own neuro-signals, therefore not designed to directly assist active walking [

55,

56]. Using our attempts to incorporate ML algorithm, however, feedforward actuation to reduce the tripping risk could be possible by operating exoskeletons by kinematic inputs. If ankle control is not based on neuro-signals, rehabilitation effects on motor control may be lower but in return, wearers can be expected to learn the optimum ankle motion during the swing phase and acquire less trip-prone walking patterns. Such application is one of the fruitful directions of the current research outcomes for practical rehabilitation settings, while continuous research efforts are essentially required.

5. Conclusions

Tri-axial linear accelerations and angular velocities data obtained from a single IMU sensor attached to the mid-foot successfully classified MFC into the three sub-categories including (i) less than 1.5cm, (ii) 1.5-2.0cm and (iii) higher than 2.0cm. As the data were collected only from the six healthy young adults, the next phase of development requires larger data volume from different population groups including individuals with higher risk of tripping-related falls such as older adults, stroke survivors and people with pathological conditions (e.g. Parkinson’s disease, dementia). In conclusion, the current study has provided important implications about predicting MFC heights and KNN has provided high accuracy (i.e. 84%) and quick computation time. While MFC prediction performance needs to be tested using other machine learning algorithms and populations, the results of this research provide support for application into control of movement assistive devices. Secondly, that vertical acceleration and the ‘x’ and ‘z’ components of the angular velocities are mostly related to the minimum foot clearance height.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.N., and R.B.; methodology, H.N., C.O.A. and R.B.; software, C.O.A.; validation, C.O.A.; formal analysis, C.O.A.; investigation, H.N., C.O.A. and E.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.N.; E.S. and C O.A.; writing—review and editing, DL.; R.B.; supervision, Y.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by veski – Study Melbourne Research Partnerships (SMRP) program, grant number veski-SMRP #2003.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics Committee of Victoria University

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable requests.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Srivastava, S.; Muhammad, T. Prevalence and risk factors of fall-related injury among older adults in India: evidence from a cross-sectional observational study. BMC Public Heal. 2022, 22, 550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prudham, D.; Evans, J.G. Factors Associated with Falls in the Elderly: A Community Study. Age Ageing 1981, 10, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinetti, M.E.; Speechley, M.; Ginter, S.F. Risk Factors for Falls among Elderly Persons Living in the Community. New Engl. J. Med. 1988, 319, 1701–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, W.E.; De Silva, D.A.; Chang, H.M.; Yao, J.; Matchar, D.B.; Young, S.H.Y.; See, S.J.; Lim, G.H.; Wong, T.H.; Venketasubramanian, N. Post-stroke patients with moderate function have the greatest risk of falls: a National Cohort Study. BMC Geriatr. 2019, 19, 373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fasano, A.; Canning, C.G.; Hausdorff, J.M.; Lord, S.; Rochester, L. Falls in Parkinson's disease: A complex and evolving picture. Mov. Disord. 2017, 32, 1524–1536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pressley, J.; Louis, E.; Tang, M.-X.; Cote, L.; Cohen, P.; Glied, S.; Mayeux, R. The impact of comorbid disease and injuries on resource use and expenditures in parkinsonism. Neurology 2003, 60, 87–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cattaneo, D.; Gervasoni, E.; Pupillo, E.; Bianchi, E.; Aprile, I.; Imbimbo, I.; Russo, R.; Cruciani, A.; Turolla, A.; Jonsdottir, J.; et al. Educational and Exercise Intervention to Prevent Falls and Improve Participation in Subjects With Neurological Conditions: The NEUROFALL Randomized Controlled Trial. Front. Neurol. 2019, 10, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hornbrook, M.C.; Stevens, V.J.; Wingfield, D.J.; Hollis, J.F.; Greenlick, M.R.; Ory, M.G. Preventing Falls Among Community-Dwelling Older Persons: Results From a Randomized Trial. Gerontol. 1994, 34, 16–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hausdorff, J.M.; Rios, D.A.; Edelberg, H.K. Gait variability and fall risk in community-living older adults: A 1-year prospective study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 2001, 82, 1050–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alemdaroğlu, E.; Uçan, H.; Topçuoğlu, A.M.; Sivas, F. In-Hospital Predictors of Falls in Community-Dwelling Individuals After Stroke in the First 6 Months After a Baseline Evaluation: A Prospective Cohort Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 2012, 93, 2244–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackintosh, S.F.; Hill, K.D.; Dodd, K.J.; Goldie, P.A.; Culham, E.G. Balance Score and a History of Falls in Hospital Predict Recurrent Falls in the 6 Months Following Stroke Rehabilitation. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 2006, 87, 1583–1589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forster, A.; Young, J. Incidence and consequences offalls due to stroke: a systematic inquiry. BMJ 1995, 311, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bloem, B.R.; Grimbergen, Y.A.M.; Cramer, M.; Willemsen, M.; Zwinderman, A.H. Prospective assessment of falls in Parkinson's disease. J. Neurol. 2001, 248, 950–958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.S.; Sherrington, C.; Canning, C.G.; Fung, V.S.C.; Close, J.C.T.; Lord, S.R. The Relative Contribution of Physical and Cognitive Fall Risk Factors in People With Parkinson’s Disease: a large prospective cohort study. Neurorehabilit. Neural Repair 2014, 28, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubenstein, L.Z. Falls in older people: epidemiology, risk factors and strategies for prevention. Age Ageing 2006, 35 (Suppl. 2), ii37–ii41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hendrie, D.; E Hall, S.; Arena, G.; Legge, M. Health system costs of falls of older adults in Western Australia. Aust. Heal. Rev. 2004, 28, 363–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stolze, H.; Klebe, S.; Zechlin, C.; Baecker, C.; Friege, L.; Deuschl, G. Falls in frequent neurological diseases--prevalence, risk factors and aetiology. J. Neurol. 2004, 251, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, W.P.; Alessio, H.M.; Mills, E.M.; Tong, C. Circumstances and consequences of falls in independent community-dwelling older adults. Age Ageing 1997, 26, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, A.J.; Morgan, K.; Bendall, M.J.; Dallosso, H.; Ebrahim, S.B.J.; Arie, T.H.D.; Fentem, P.H.; Bassey, E.J. Falls by elderly people at home: prevalence and associated factors. Age Ageing 1988, 17, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, H.; Begg, R.K.; Sparrow, W.A.; Taylor, S. Ageing and limb dominance effects on foot-ground clearance during treadmill and overground walking. Clin. Biomech. 2011, 26, 962–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begg, R.; Best, R.; Dell’oro, L.; Taylor, S. Minimum foot clearance during walking: Strategies for the minimisation of trip-related falls. Gait Posture 2007, 25, 191–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delfi, G.; Al Bochi, A.; Dutta, T. A Scoping Review on Minimum Foot Clearance Measurement: Sensing Modalities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 10848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, B.W.; Lloyd, J.D.; Lee, W.E. The effects of everyday concurrent tasks on overground minimum toe clearance and gait parameters. Gait Posture 2010, 32, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winter, D.A. Foot Trajectory in Human Gait: A Precise and Multifactorial Motor Control Task. Phys. Ther. 1992, 72, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smeesters, C.; Hayes, W.C.; McMahon, T.A. Disturbance type and gait speed affect fall direction and impact location. J. Biomech. 2001, 34, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moosabhoy, M.A.; Gard, S.A. Methodology for determining the sensitivity of swing leg toe clearance and leg length to swing leg joint angles during gait. Gait Posture 2006, 24, 493–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, H.; Begg, R. A shoe-insole to improve ankle joint mechanics for injury prevention among older adults. Ergonomics 2021, 64, 1271–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begg, R.K.; Tirosh, O.; Said, C.M.; Sparrow, W.A.; Steinberg, N.; Levinger, P.; Galea, M.P. Gait training with real-time augmented toe-ground clearance information decreases tripping risk in older adults and a person with chronic stroke. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, H.; Begg, R.K. Shoe-Insole Technology for Injury Prevention in Walking. Sensors 2018, 18, 1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarashina, E.; Mizukami, K.; Yoshizawa, Y.; Sakurai, J.; Tsuji, A.; Begg, R. Feasibility of Pilates for Late-Stage Frail Older Adults to Minimize Falls and Enhance Cognitive Functions. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arami, A.; Raymond, N.S.; Aminian, K. An Accurate Wearable Foot Clearance Estimation System: Toward a Real-Time Measurement System. IEEE Sensors J. 2017, 17, 2542–2549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santhiranayagam, B.K.; Lai, D.T.H.; Begg, R.K.; Palaniswami, M. Estimation of end point foot clearance points from inertial sensor data. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2011, 2011, 6503–6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariani, B.; Hoskovec, C.; Rochat, S.; Büla, C.; Penders, J.; Aminian, K. 3D gait assessment in young and elderly subjects using foot-worn inertial sensors. J. Biomech. 2010, 43, 2999–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mariani, B.; Rochat, S.; Büla, C.J.; Aminian, K. Heel and Toe Clearance Estimation for Gait Analysis Using Wireless Inertial Sensors. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Eng. 2012, 59, 3162–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitagawa, N.; Ogihara, N. Estimation of foot trajectory during human walking by a wearable inertial measurement unit mounted to the foot. Gait Posture 2016, 45, 110–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoussaad, M.; Sijobert, B.; Mombaur, K.; Coste, C.A. Robust Foot Clearance Estimation Based on the Integration of Foot-Mounted IMU Acceleration Data. Sensors 2016, 16, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, D.T.; Charry, E.; Begg, R.; Palaniswami, M. A prototype wireless inertial-sensing device for measuring toe clearance. Annu. Int. Conf. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 2008, 2008, 4899–4902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asogwa, C.O.; Nagano, H.; Wang, K.; Begg, R. Using Deep Learning to Predict Minimum Foot–Ground Clearance Event from Toe-Off Kinematics. Sensors 2022, 22, 6960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashal, I.; Alsaryrah, O.; Chung, T.-Y. Testing and evaluating recommendation algorithms in internet of things. J. Ambient. Intell. Humaniz. Comput. 2016, 7, 889–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.M.S.; Siddiquee, M.R.; Atri, R.; Ramon, R.; Marquez, J.S.; Bai, O. Prediction of gait intention from pre-movement EEG signals: a feasibility study. J. Neuroeng. Rehabilitation 2020, 17, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukahara, A.; Hasegawa, Y.; Eguchi, K.; Sankai, Y. Restoration of Gait for Spinal Cord Injury Patients Using HAL With Intention Estimator for Preferable Swing Speed. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabilitation Eng. 2014, 23, 308–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Novak, D.; Reberšek, P.; De Rossi, S.M.M.; Donati, M.; Podobnik, J.; Beravs, T.; Lenzi, T.; Vitiello, N.; Carrozza, M.C.; Munih, M. Automated detection of gait initiation and termination using wearable sensors. Med Eng. Phys. 2013, 35, 1713–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohannon, R.W.; Wang, Y.-C. Four-Meter Gait Speed: Normative Values and Reliability Determined for Adults Participating in the NIH Toolbox Study. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabilitation 2019, 100, 509–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, H. Gait Biomechanics for Fall Prevention among Older Adults. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 6660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, H.; Said, C.M.; James, L.; Sparrow, W.A.; Begg, R. Biomechanical Correlates of Falls Risk in Gait Impaired Stroke Survivors. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 833417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Bochi, A.; Delfi, G.; Dutta, T. A Scoping Review on Minimum Foot Clearance: An Exploration of Level-Ground Clearance in Individuals with Abnormal Gait. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Heal. 2021, 18, 10289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seaborn. Available online: https://seaborn.pydata.org (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Derlatka, M. Modified kNN algorithm for improved recognition accuracy of biometrics system based on gait. In IFIP International Conference on Computer Information Systems and Industrial Management (pp. 59-66). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Gupta, A., Jadhav, A., Jadhav, S. and Thengade, A., 2020. Human gait analysis based on decision tree, random forest and KNN algorithms. In Applied Computer Vision and Image Processing (pp. 283-289). Springer, Singapore.

- Saito, T.; Rehmsmeier, M. The Precision-Recall Plot Is More Informative than the ROC Plot When Evaluating Binary Classifiers on Imbalanced Datasets. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0118432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mills, P.M.; Barrett, R.S. Swing phase mechanics of healthy young and elderly men. Hum. Mov. Sci. 2001, 20, 427–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubota, S.; Kadone, H.; Shimizu, Y.; Koda, M.; Noguchi, H.; Takahashi, H.; Watanabe, H.; Hada, Y.; Sankai, Y.; Yamazaki, M. Development of a New Ankle Joint Hybrid Assistive Limb. Medicina 2022, 58, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankai, Y. HAL: Hybrid Assistive Limb Based on Cybernics. In: Kaneko, M., Nakamura, Y. (eds) Robotics Research. Springer Tracts in Advanced Robotics. 2010;66. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Soma, Y.; Kubota, S.; Kadone, H.; Shimizu, Y.; Takahashi, H.; Hada, Y.; Koda, M.; Sankai, Y.; Yamazaki, M. Hybrid Assistive Limb Functional Treatment for a Patient with Chronic Incomplete Cervical Spinal Cord Injury. Int. Med Case Rep. J. 2021, ume 14, 413–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagano, H.; Said, C.M.; James, L.; Sparrow, W.A.; Begg, R. Biomechanical Correlates of Falls Risk in Gait Impaired Stroke Survivors. Front. Physiol. 2022, 13, 833417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mataki, Y.; Kamada, H.; Mutsuzaki, H.; Shimizu, Y.; Takeuchi, R.; Mizukami, M.; Yoshikawa, K.; Takahashi, K.; Matsuda, M.; Iwasaki, N.; et al. Use of Hybrid Assistive Limb (HAL®) for a postoperative patient with cerebral palsy: a case report. BMC Res. Notes 2018, 11, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).