Submitted:

14 August 2023

Posted:

15 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

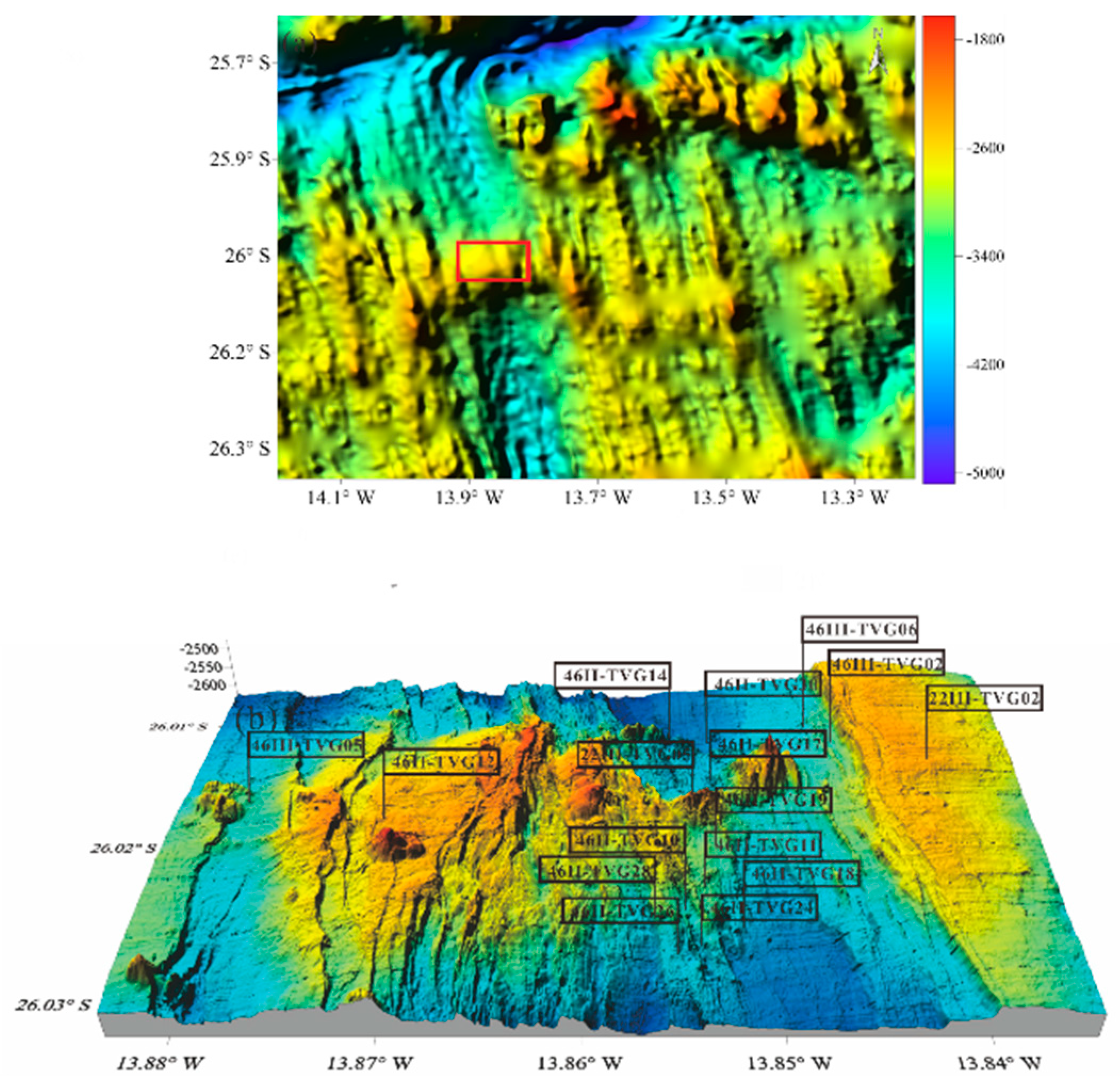

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

| Elements | Xunmei (n = 16) |

BGS (n = 10) |

Basalts (n = 16) |

Serpentinite (n = 16) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Min | Max | Average | Median | SD | Average | Average | Average | |

| Al (wt.%) | 0.09 | 6.20 | 2.44 | 1.97 | 2.2 | 2.56 | 7.91 | 0.60 |

| Si (wt.%) | 2.78 | 19.54 | 11.32 | 11.64 | 5.38 | 6.31 | 23.75 | 18.40 |

| Ca (wt.%) | 0.23 | 26.55 | 7.37 | 3.30 | 8.74 | 28.84 | 8.58 | 0.37 |

| Fe (wt.%) | 4.58 | 38.78 | 21.25 | 20.49 | 12.36 | 2.24 | 6.84 | 6.05 |

| K (wt.%) | 0.10 | 0.75 | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.19 | 0.28 | 0.09 | - |

| Mg (wt.%) | 0.16 | 4.04 | 1.82 | 1.58 | 1.24 | 1.58 | 4.84 | 22.42 |

| Mn (wt.%) | 0.04 | 24.29 | 2.91 | 0.34 | 7.03 | 0.12 | 0.13 | 0.09 |

| Na (wt.%) | 0.46 | 2.45 | 1.41 | 1.41 | 0.47 | 1.31 | 1.88 | 0.08 |

| P (wt.%) | 0.09 | 0.66 | 0.29 | 0.31 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.04 | --- |

| Ti (wt.%) | 0.00 | 0.66 | 0.22 | 0.18 | 0.22 | 0.17 | 0.77 | 0.02 |

| Ba (ppm) | 31.04 | 1828 | 296.9 | 110.3 | 530.7 | 225.4 | 2.75 | - |

| Sr (ppm) | 11.30 | 1268 | 403.6 | 215.8 | 405.8 | 1251 | 112.6 | |

| V (ppm) | 73.94 | 806.1 | 330.7 | 317.3 | 190 | 63.45 | 266 | 38.91 |

| Zn (ppm) | 184 | 57,936 | 6922 | 3350 | 14263 | 40.87 | 71.59 | 36.28 |

| Zr (ppm) | 2.50 | 57.10 | 24.60 | 25.11 | 19.73 | 27.81 | 81.56 | |

| Co (ppm) | 16.63 | 304.6 | 114.9 | 91.65 | 72.82 | 23.00 | 40.93 | 89.65 |

| Cu (ppm) | 805.9 | 58286 | 16431 | 11514 | 16817 | 56.01 | 71.55 | 12.18 |

| Ni (ppm) | 2.87 | 335.4 | 51.85 | 35.81 | 78.55 | 53.12 | 71.46 | 1947 |

| Cr (ppm) | 16.37 | 232.5 | 101 | 88.01 | 68.42 | 65.18 | 324 | 1238 |

| Sc (ppm) | 0.54 | 33.84 | 11.91 | 11.00 | 11.18 | 8.58 | 40.43 | |

| U (ppm) | 0.33 | 11.48 | 4.15 | 3.66 | 3.36 | 0.42 | 0.05 | |

| Y (ppm) | 0.86 | 28.55 | 13.77 | 14.52 | 9.13 | 14.60 | 26.58 | |

| Mo (ppm) | 3.01 | 394.5 | 121.7 | 86.43 | 127.5 | 1.09 | 0.47 | |

| Zr (ppm) | 2.50 | 61.57 | 24.60 | 25.11 | 19.73 | 30.65 | 81.56 | |

| MSI | 0.32 | 42.08 | 14.26 | 10.30 | 14.33 | 44.09 | ||

| ∑REE | 1.64 | 51.66 | 28.30 | 32.61 | 17.29 | 50.24 | ||

| LREE | 1.04 | 38.28 | 20.29 | 22.96 | 12.56 | 42.13 | ||

| HREE | 0.60 | 15.36 | 8.01 | 9.24 | 5.23 | 8.1 | ||

| L/H | 1.52 | 4.30 | 2.76 | 2.53 | 0.89 | 5.16 | ||

| δEu | 0.88 | 4.53 | 1.58 | 1.04 | 1.11 | 0.84 | ||

| δCe | 0.34 | 0.84 | 0.61 | 0.58 | 0.16 | 0.72 |

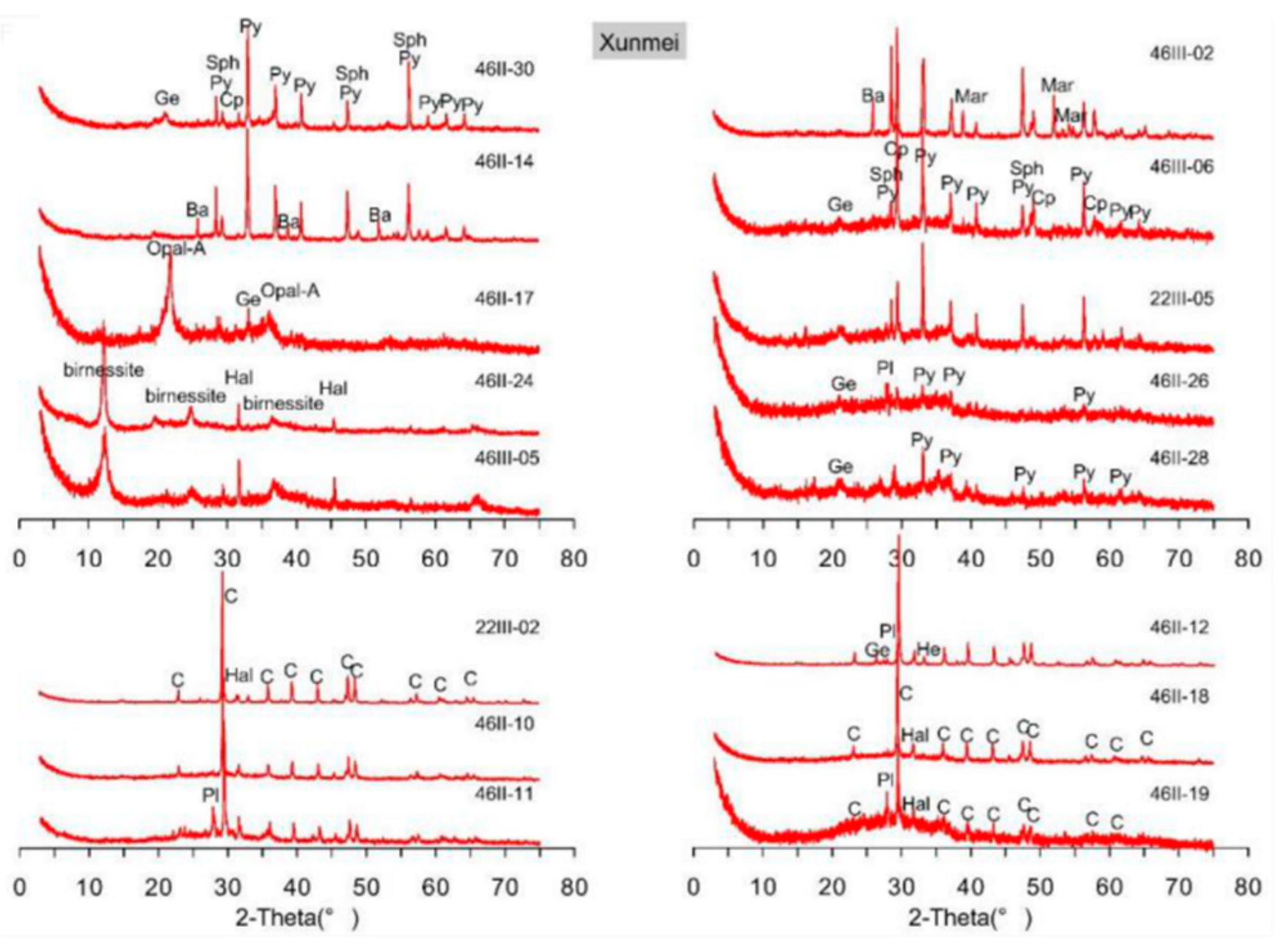

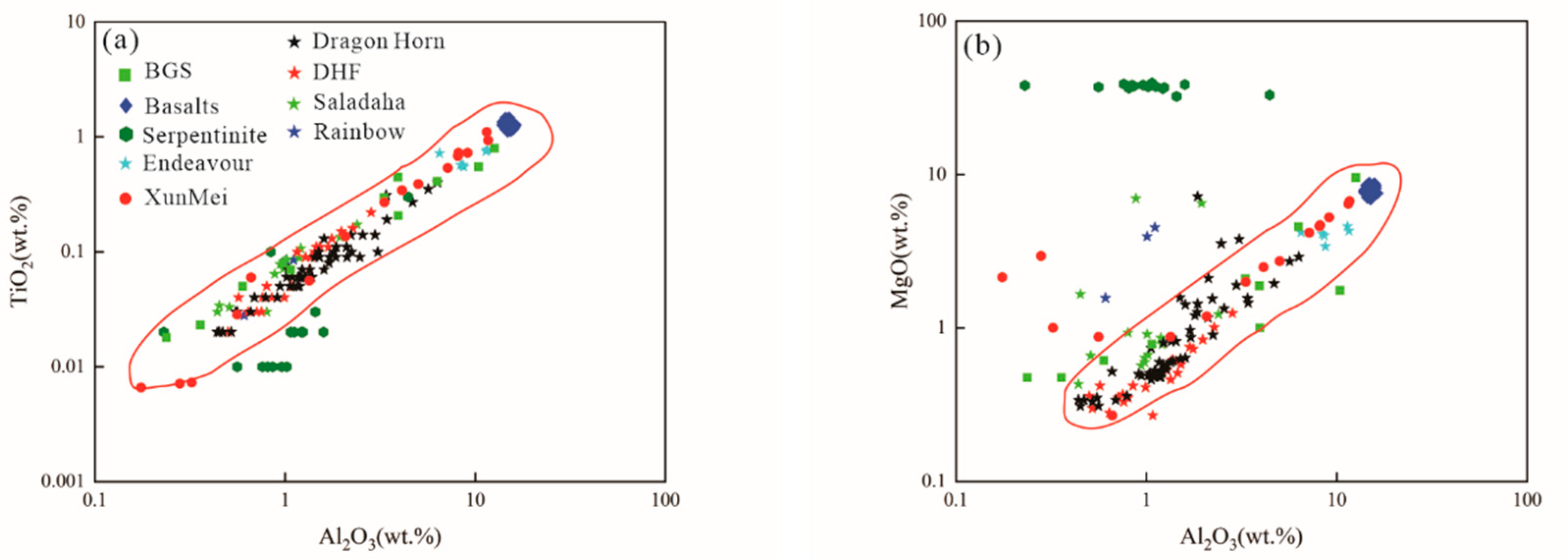

3.1. Major elements

3.2. Trace elements

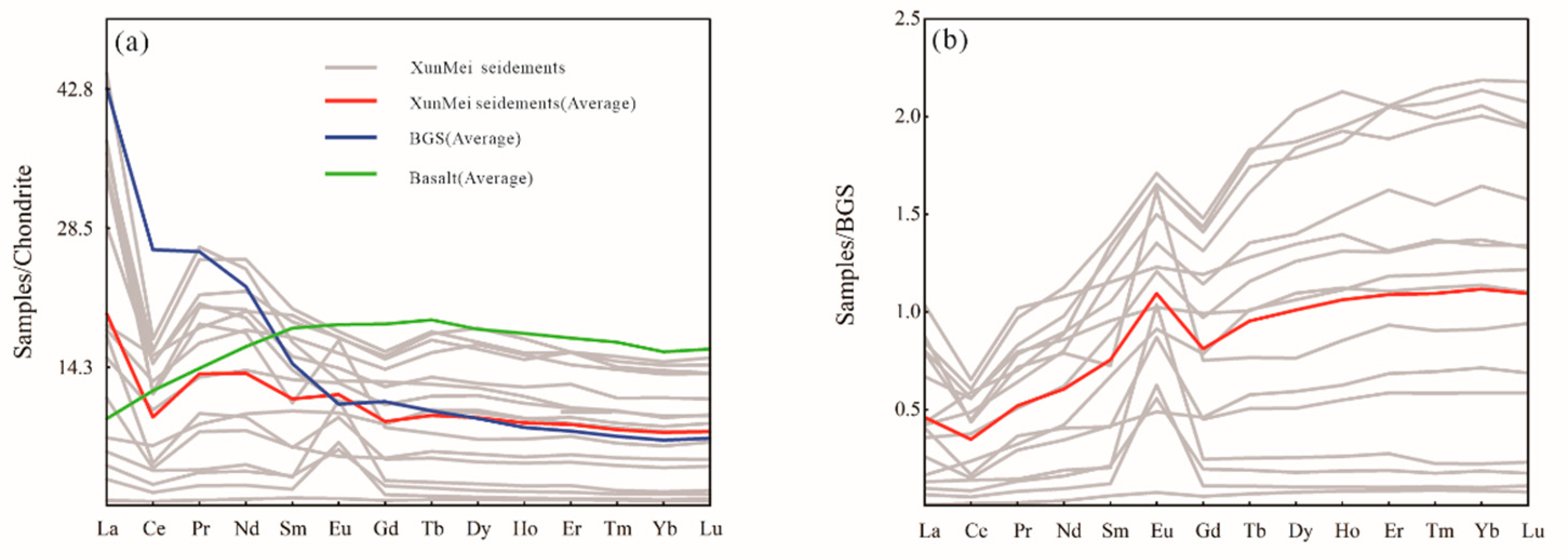

3.3. Rare earth elements

4. Discussion

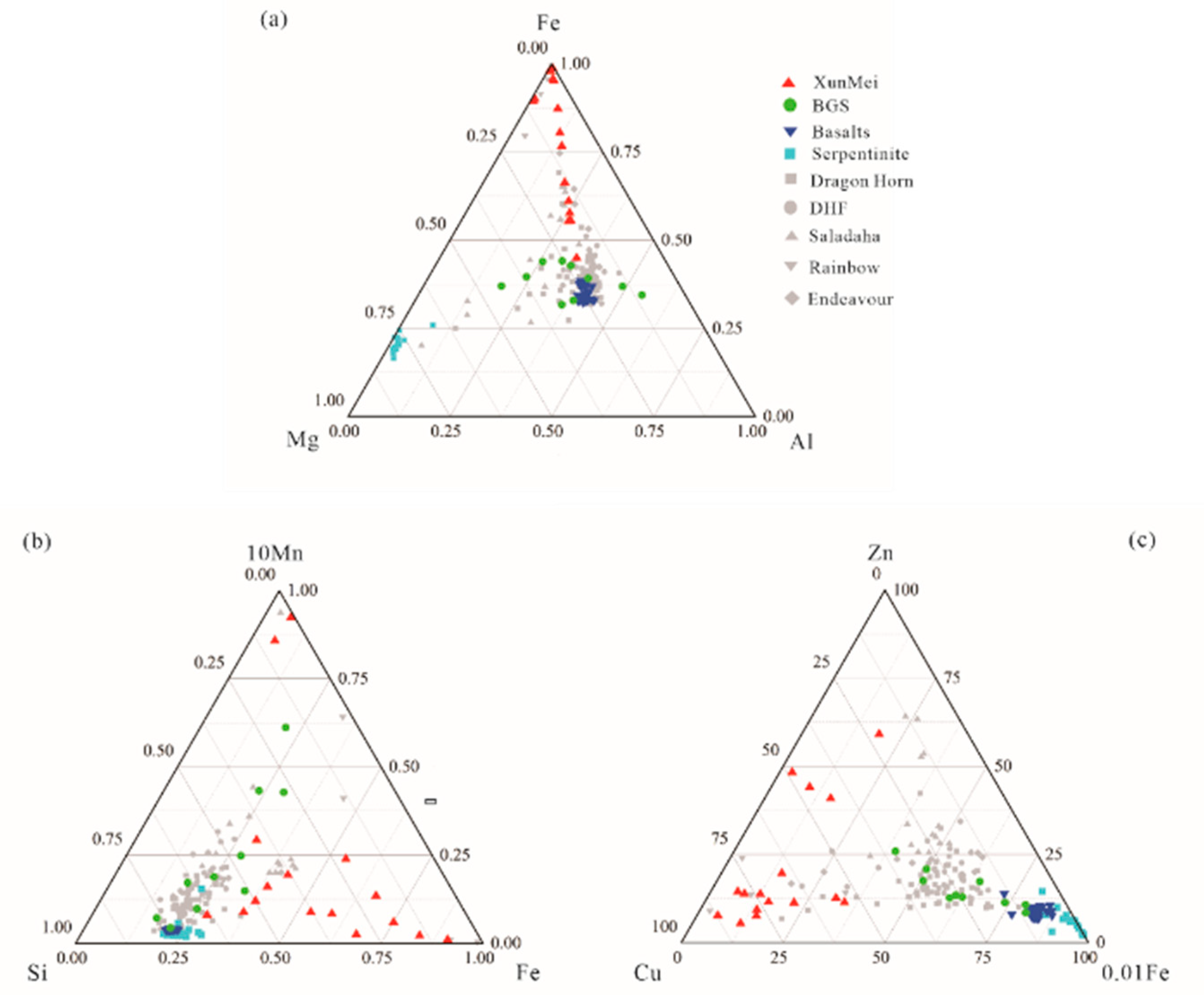

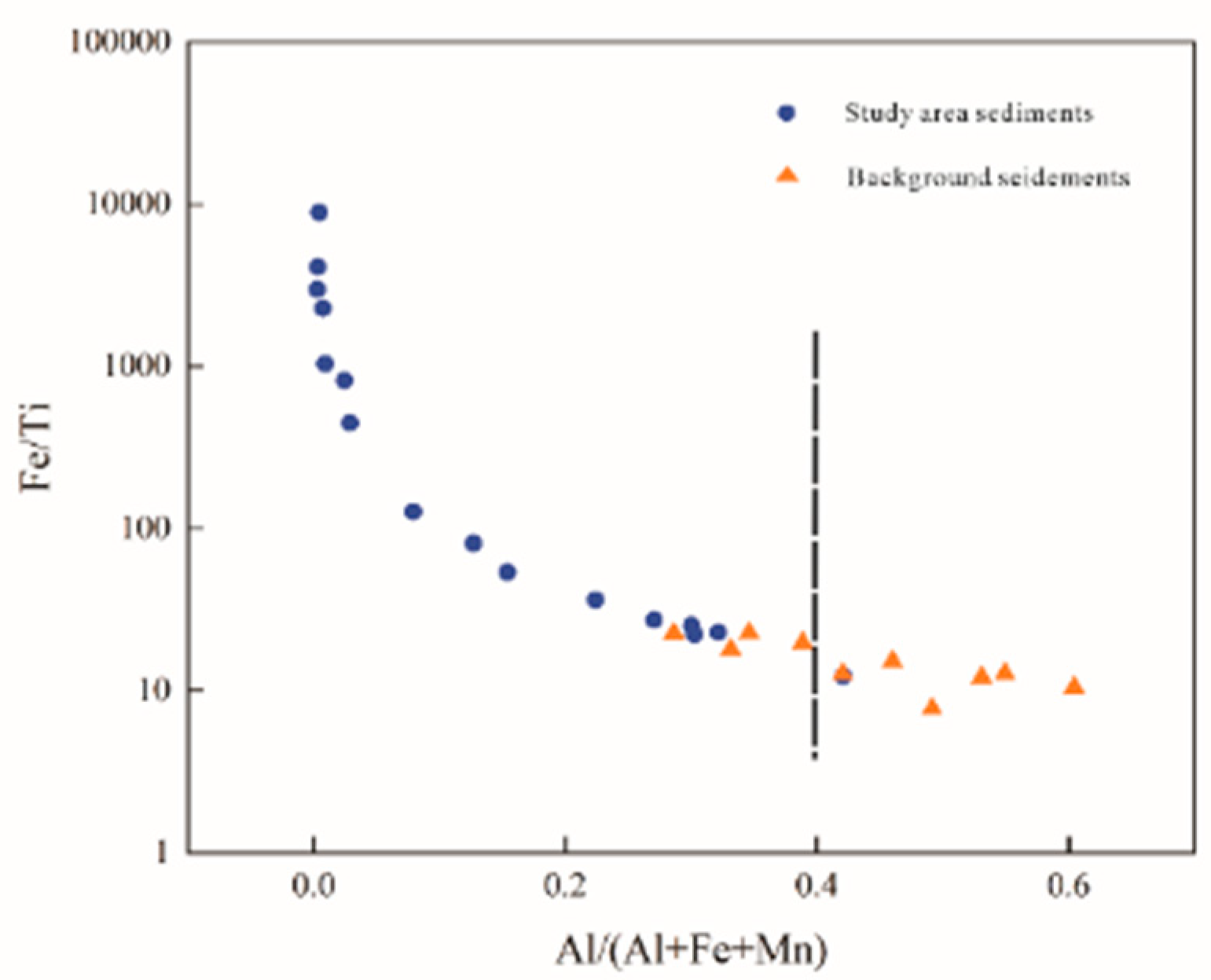

4.1. Sediment compositions

4.2. Distribution characteristics of hydrothermal-derived elements in sediments

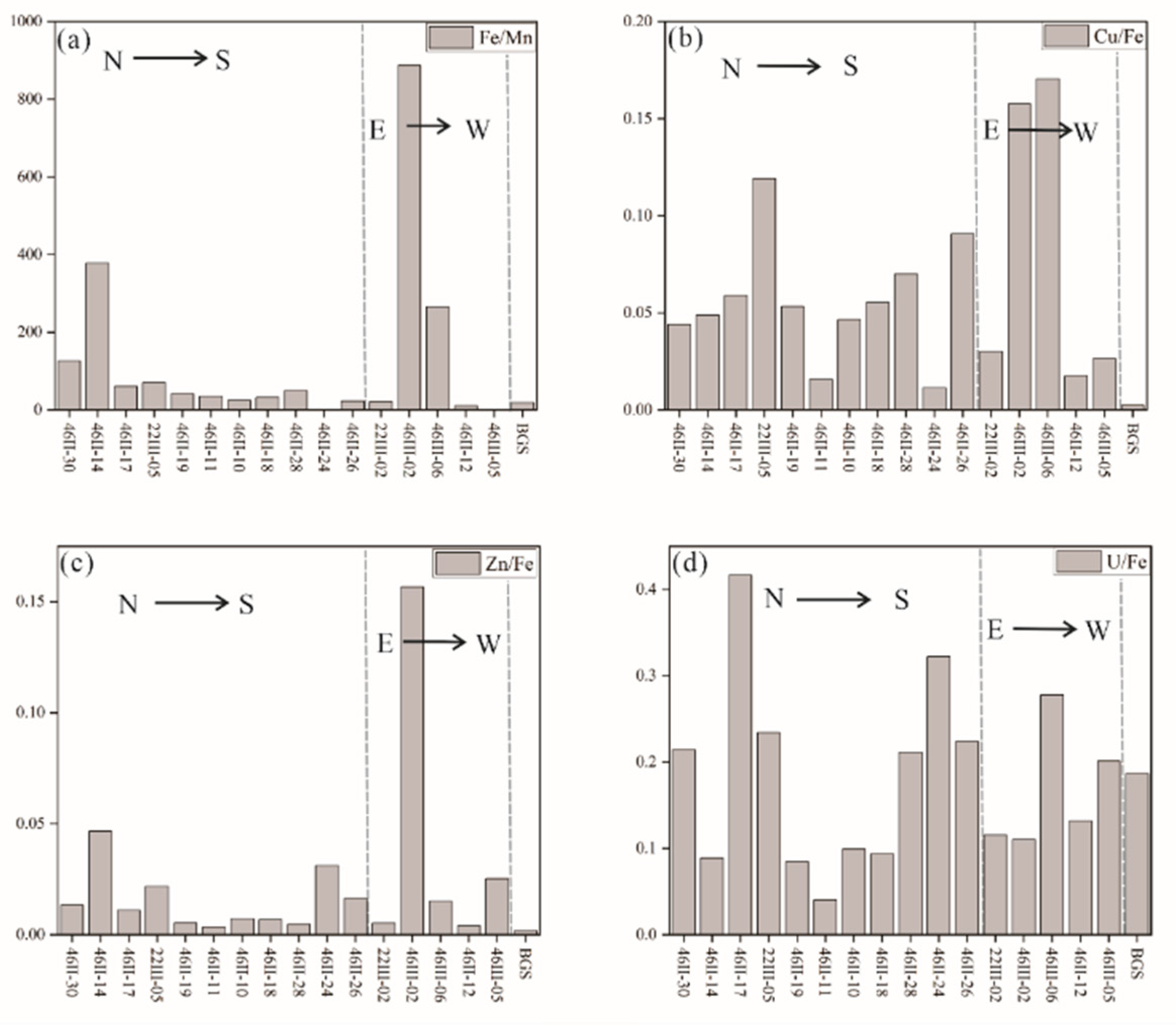

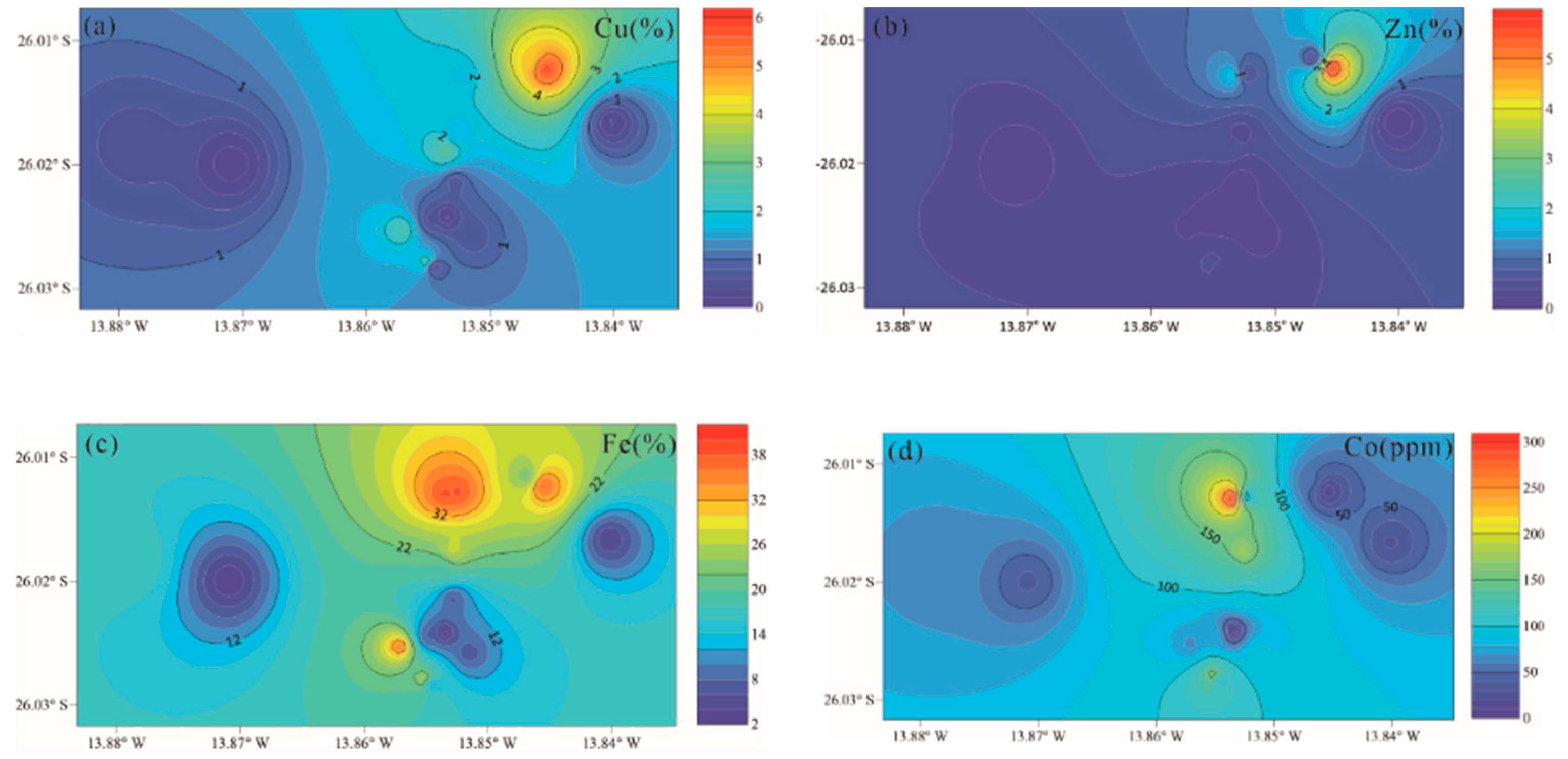

4.2.1. Cu, Zn, Fe, Co

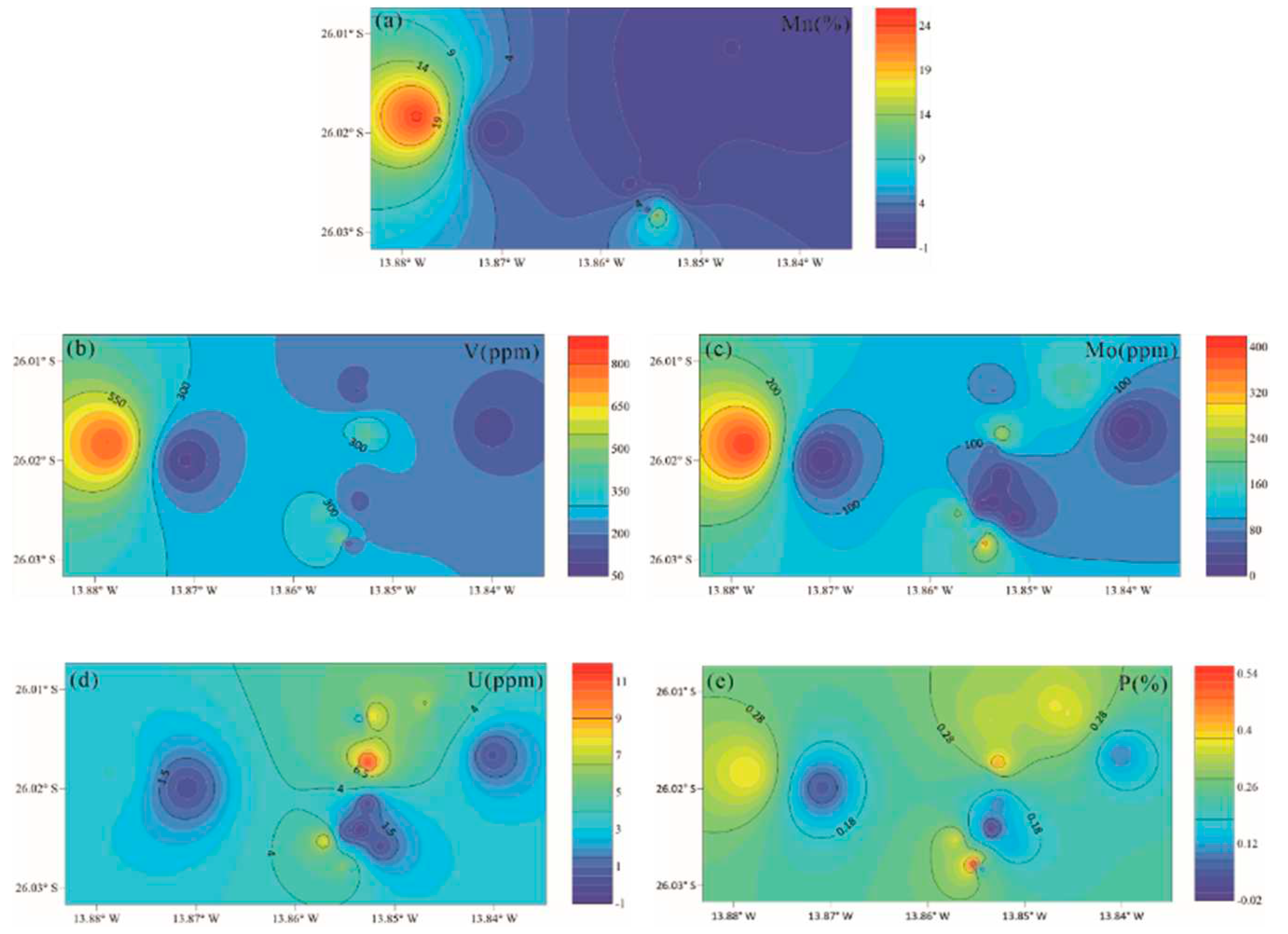

4.2.2. Mn, V, Mo, U, P

4.3. Geochemical characteristics of different regional hydrothermal activities

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hannington, M.; Jamieson, J.; Monecke, T.; Petersen, S.; Beaulieu, S. The abundance of seafloor massive sulfide deposits. Geology 2011, 39, 1155–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Yang, Y.; Wang, G.; Fan, L.; Wang, C.; Li, B. The Mineralogical Characteristics of Pyrite at 26°S Hydrothermal Field, South Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Acta Geologica Sinica - English Edition 2014, 88, 179–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.; Zhou, H. Research status and prospects of metalliferous sediments in hydrothermal vents. Marine Science 2021, 45, 69–80. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H.; Han, X.; Wang, Y.; Wu, X.; Cai, Y.; Yang, M. Exploring the Mechanism and Resource Prospects of Strategic Metal Enrichment in Global Modern Seafloor Massive Sulfides. Earth Science-Journal of China University of Geosciences 2021, 46. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, C.; Li, H.; Yang, Y.; Ni, J.; Cui, R.; Chen, Y.; Li, J.; He, Y.; Huang, W.; Lei, J.; Wang, Y. Two hydrothermal fields found on the Southern Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Science China Earth Sciences 2011, 54, 1302–1303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, C.; Li, H.; Jin, X.; Zhou, J.; Wu, T.; He, Y.; Deng, X.; Gu, C.; Zhang, G.; Liu, W. Seafloor hydrothermal activity and polymetallic sulfide exploration on the southwest Indian ridge. Chinese Science Bulletin 2014, 59, 2266–2276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Tao, C.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, G.; Qin, H.; Wang, Y.; Chen, D. Distribution characteristics of hydrothermal plumes on the mid-ocean ridge and their indicative role in polymetallic sulfide exploration. Acta Oceanologica Sinica 2019, 41, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Tao, C.; Li, H.; Zhang, G.; Liang, J.; Yang, W.; Wang, Y. Surface sediment geochemistry and hydrothermal activity indicators in the Dragon Horn area on the Southwest Indian Ridge. Marine Geology 2018, 398, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dymond, J.; Corliss, J.B.; Heath, G.R.; Field, C.W.; Dasch, E.J.; Veeh, H.H. Origin of Metalliferous Sediments from the Pacific Ocean. Geological Society of America Bulletin 1973, 84, 3355–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, R.; Elderfield, H.; Thomson, J. A dual origin for the hydrothermal component in a metalliferous sediment core from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Journal of Geophysical Research 1993, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurvich, Metalliferous sediments of the world ocean: Fundamental theory of deep sea hydrothermal sedimentation. 2006.

- Hrischeva, E.; Scott, S.D. Geochemistry and morphology of metalliferous sediments and oxyhydroxides from the Endeavour segment, Juan de Fuca Ridge. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2007, 71, 3476–3497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodeï, S.; Buatier, M.; Steinmann, M.; Adatte, T.; Wheat, C.G. Characterization of metalliferous sediment from a low-temperature hydrothermal environment on the Eastern Flank of the East Pacific Rise. Marine Geology 2008, 250, 128–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekov, V.M.; Cuadros, J.; Kamenov, G.D.; Weiss, D.; Arnold, T.; Basak, C.; Rochette, P. Metalliferous sediments from the H.M.S. Challenger voyage (1872–1876). Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2010, 74, 5019–5038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feely, R.A.; Lewison, M.; Massoth, G.J.; Robert-Baldo, G.; Lavelle, J.W.; Byrne, R.H.; Von Damm, K.L.; Curl, H.C. Composition and dissolution of black smoker particulates from active vents on the Juan de Fuca Ridge. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 1987, 92, 11347–11363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanc, G.; Anschutz, P.; Pierret, M.-C. Metalliferous sedimentation in the Atlantis II Deep: A geochemical insight. In Sedimentation and Tectonics in Rift Basins Red Sea:- Gulf of Aden; Purser, B.H., Bosence, D.W.J., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 1998; pp. 505–520. [Google Scholar]

- Feely, R.A.; Massoth, G.J.; Baker, E.T.; Lebon, G.T.; Geiselman, T.L. Tracking the dispersal of hydrothermal plumes from the Juan de Fuca Ridge using suspended matter compositions. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 1992, 97, 3457–3468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, K.; Kraemer, T.; Gartner, S. Provenance and accumulation rates of opaline silica, Al, Ti, Fe, Mn, Cu, Ni and Co in Pacific pelagic sediments. Chemical Geology 1973, 11, 123–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boström, K.; Peterson, M.N.A.; Joensuu, O.; Fisher, D.E. Aluminum-poor ferromanganoan sediments on active oceanic ridges. Journal of Geophysical Research 1969, 74, 3261–3270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, T.J.; Jarvis, I.; Hannington, M.D.; Thirlwall, M.F. Chemical characteristics of modern deep-sea metalliferous sediments in closed versus open basins, with emphasis on rare-earth elements and Nd isotopes. Earth-Science Reviews 2021, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, C.R. Hydrothermal activity on the eastern SWIR (50°-70°E): Evidence from core-top geochemistry, 1887 and 1998. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems 2003, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Li, H.; Li, M.; Zhai, S. Hydrothermal signature in the axial-sediments from the Carlsberg Ridge in the northwest Indian Ocean. Journal of Marine Systems 2018, 180, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Liu, J.; Shi, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, X.; Wu, Y.; Fang, X. Mineralogy and sulfur isotope characteristics of metalliferous sediments from the Tangyin hydrothermal field in the southern Okinawa Trough. Ore Geology Reviews 2020, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Wu, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Cui, J.; Yu, M.; Dang, Y.; Shi, X.; Liu, J. Mineralogical and geochemical characteristics and ore-forming mechanism of hydrothermal sediments in the middle and southern Okinawa Trough. Marine Geology 2021, 437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuhn, T.; Burger, H.; Castradori, D.; Halbach, P. Volcanic and hydrothermal history of ridge segments near the Rodrigues Triple Junction (Central Indian Ocean) deduced from sediment geochemistry. Marine Geology 2000, 169, 391–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cave, R.R.; German, C.R.; Thomson, J.; Nesbitt, R.W. Fluxes to sediments underlying the Rainbow hydrothermal plume at 36°14′N on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2002, 66, 1905–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Z.; Han, X.; Li, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Fan, W.; Zhou, Y.; Cui, R.; Wang, L. The temporal variability of hydrothermal activity of Wocan hydrothermal field, Carlsberg Ridge, northwest Indian Ocean. Ore Geology Reviews 2021, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearme, S.; Cronan, D.S.; Rona, P.A. Geochemistry of sediments from the TAG Hydrothermal Field, M.A.R. at latitude 26° N. Marine Geology 1983, 51, 269–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, S.; Tao, C.; Dias, Á.A.; Su, X.; Yang, Z.; Ni, J.; Liang, J.; Yang, W.; Liu, J.; Li, W.; Dong, C. Surface sediment composition and distribution of hydrothermal derived elements at the Duanqiao-1 hydrothermal field, Southwest Indian Ridge. Marine Geology 2019, 416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Wang, G.; Holzheid, A.; Zoheir, B.; Shi, X. Isocubanite-chalcopyrite intergrowths in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge 26°S hydrothermal vent sulfides. Geochemistry 2021, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Wang, G.; Holzheid, A.; Zoheir, B.; Shi, X. Sulfur and copper isotopic composition of seafloor massive sulfides and fluid evolution in the 26°S hydrothermal field, Southern Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Marine Geology 2021, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Wang, G.; Holzheid, A.; Zoheir, B.; Shi, X.; Lei, Q. Systematic variations in trace element composition of pyrites from the 26°S hydrothermal field, Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Ore Geology Reviews 2022, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Li, C.; Li, B.; Dang, Y.; Ye, J.; Zhu, Z.; Zhang, L.; Shi, X. Constraints on fluid evolution and growth processes of black smoker chimneys by pyrite geochemistry: A case study of the Tongguan hydrothermal field, South Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Ore Geology Reviews 2022, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Sun, W.; Huang, J.; Zhai, S.; Li, H. Coupled Fe-S isotope composition of sulfide chimneys dominated by temperature heterogeneity in seafloor hydrothermal systems. Sci Bull (Beijing) 2020, 65, 1767–1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, C.; Chen, S.; Baker, E.T.; Li, H.; Liang, J.; Liao, S.; Chen, Y.J.; Deng, X.; Zhang, G.; Gu, C.; Wu, J. Hydrothermal plume mapping as a prospecting tool for seafloor sulfide deposits: A case study at the Zouyu-1 and Zouyu-2 hydrothermal fields in the southern Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Marine Geophysical Research 2017, 38, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Liu, J.; Li, C.; Zhu, A.; Wang, H.; Cui, J.; Zhang, H.; Hu, Q.; Shi, X. Mineralogical and geochemical characteristics of near-vent metalliferous sediments: Implications for hydrothermal processes along the southern Mid-Atlantic ridge (12°S–28°S). Ore Geology Reviews 2022, 148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbotte, S.; Welch, S.M.; MacDonald, K.C. Spreading rates, rift propagation, and fracture zone offset histories during the past 5 my on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge; 25°–27°30′ S and 31°–34°30′ S. Marine Geophysical Researches 1991, 13, 51–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, R.H.; Elderfield, H. Chemistry of ore-forming fluids and mineral formation rates in an active hydrothermal sulfide deposit on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Geology 1996, 24, 1147–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, Y.; Batiza, R. Magmatic processes at a slow spreading ridge segment: 26°S Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 1994, 99, 19719–19740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regelous, M.; Niu, Y.; Abouchami, W.; Castillo, P.R. Shallow origin for South Atlantic Dupal Anomaly from lower continental crust: Geochemical evidence from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge at 26°S. Lithos 2009, 112, 57–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Wang, G.; Shi, X.; Yang, Y.; Astrid, H.; A, Z.B. Geochemical characteristics and mantle source properties of basalt from the hydrothermal field along the Mid-Atlantic Ridge at 26°S. Minerology and Petrology 2020, 40, 9–20. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, M.; Yang, Y.; Su, X.; Ye, J.; Shi, X. Mineralogical Study of Chimneys in the Southern Mid-Atlantic Ridge at 26°S. China mining magazine 2014, 23, 77–81. [Google Scholar]

- Dias, Á.S.; Barriga, F.J.A.S. Mineralogy and geochemistry of hydrothermal sediments from the serpentinite-hosted Saldanha hydrothermal field (36°34′N; 33°26′W) at MAR. Marine Geology 2006, 225, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.-s.; McDonough, W.F. Chemical and isotopic systematics of oceanic basalts: Implications for mantle composition and processes. Geological Society, London, Special Publications 1989, 42, 313–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemsma, M.R.; Zabel, M.; Stuut, J.B.W.; Tjallingii, R.; Collins, J.A.; Weltje, G.J. Modelling the joint variability of grain size and chemical composition in sediments. Sedimentary Geology 2012, 280, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hannington, M.D.; De Ronde, C.E.J.; Petersen, S.; Hedenquist, J.W.; Thompson, J.F.H.; Goldfarb, R.J.; Richards, J.P. Sea-Floor Tectonics and Submarine Hydrothermal Systems. In One Hundredth Anniversary Volume; Society of Economic Geologists, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Whattam, S.A.; Früh-Green, G.L.; Cannat, M.; De Hoog, J.C.M.; Schwarzenbach, E.M.; Escartin, J.; John, B.E.; Leybourne, M.I.; Williams, M.J.; Rouméjon, S.; Akizawa, N.; Boschi, C.; Harris, M.; Wenzel, K.; McCaig, A.; Weis, D.; Bilenker, L. Geochemistry of serpentinized and multiphase altered Atlantis Massif peridotites (IODP Expedition 357): Petrogenesis and discrimination of melt-rock vs. fluid-rock processes. Chemical Geology 2022, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, R.A.; Elderfield, H. Hydrothermal Activity and the Geochemistry of Metalliferous Sediment. Geophysical Monograph Series 1995, 91, 392–407. [Google Scholar]

- Feely, R.A.; Trefry, J.H.; Lebon, G.T.; German, C.R. The relationship between P/Fe and V/Fe ratios in hydrothermal precipitates and dissolved phosphate in seawater. Geophysical Research Letters 1998, 25, 2253–2256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, C.R.; Campbell, A.C.; Edmond, J.M. Hydrothermal scavenging at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge: Modification of trace element dissolved fluxes. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 1991, 107, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edmonds, H.N.; German, C.R. Particle geochemistry in the Rainbow hydrothermal plume, Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 2004, 68, 759–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mottl, M.J.; McConachy, T.F. Chemical processes in buoyant hydrothermal plumes on the East Pacific Rise near 21°N. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1990, 54, 1911–1927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, C.R.; Hergt, J.; Palmer, M.R.; Edmond, J.M. Geochemistry of a hydrothermal sediment core from the OBS vent-field, 21°N East Pacific Rise. Chemical Geology 1999, 155, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metz, S.; Trefry, J.H. Field and laboratory studies of metal uptake and release by hydrothermal precipitates. Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth 1993, 98, 9661–9666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, R.A.; Elderfield, H. Rare earth element geochemistry of hydrothermal deposits from the active TAG Mound, 26°N Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta 1995, 59, 3511–3524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, S.R.; Huested, S.S. Ocean anoxia and the concentrations of molybdenum and vanadium in seawater. Marine Chemistry 1991, 34, 177–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, R.A.; Thomson, J.; Elderfield, H.; Hinton, R.W.; Hyslop, E. Uranium enrichment in metalliferous sediments from the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 1994, 124, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayupova, N.R.; Melekestseva, I.Y.; Maslennikov, V.V.; Tseluyko, A.S.; Blinov, I.A.; Beltenev, V.E. Uranium accumulation in modern and ancient Fe-oxide sediments: Examples from the Ashadze-2 hydrothermal sulfide field (Mid-Atlantic Ridge) and Yubileynoe massive sulfide deposit (South Urals, Russia). Sedimentary Geology 2018, 367, 164–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hein, J.R.; Clague, D.A.; Koski, R.A.; Embley, R.W.; Dunham, R.E. Metalliferous Sediment and a Silica-Hematite Deposit within the Blanco Fracture Zone, Northeast Pacific. Marine Georesources & Geotechnology 2008, 26, 317–339. [Google Scholar]

- Trefry, J.H.; Trocine, R.P.; Klinkhammer, G.P.; Rona, P.A. Iron and copper enrichment of suspended particles in dispersed hydrothermal plumes along the mid-Atlantic Ridge. Geophysical Research Letters 1985, 12, 506–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rona, P.A.; Klinkhammer, G.; Nelsen, T.A.; Trefry, J.H.; Elderfield, H. Black smokers, massive sulphides and vent biota at the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Nature 1986, 321, 33–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusakov, V.Y.; Shilov, V.V.; Ryzhenko, B.N.; Gablina, I.F.; Roshchina, I.A.; Kuz’mina, T.G.; Kononkova, N.N.; Dobretsova, I.G. Mineralogical and geochemical zoning of sediments at the Semenov cluster of hydrothermal fields, 13°31′-13°30′ N, Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Geochemistry International 2013, 51, 646–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowen, J.P.; Massoth, G.J.; Feely, R.A. Scavenging rates of dissolved manganese in a hydrothermal vent plume. Deep Sea Research Part A. Oceanographic Research Papers 1990, 37, 1619–1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, C.R.; Higgs, N.C.; Thomson, J.; Mills, R.; Elderfield, H.; Blusztajn, J.; Fleer, A.P.; Bacon, M.P. A geochemical study of metalliferous sediment from the TAG Hydrothermal Mound, 26°08′N, Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Journal of Geophysical Research 1993, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, Á.S.; Mills, R.A.; Taylor, R.N.; Ferreira, P.; Barriga, F.J.A.S. Geochemistry of a sediment push-core from the Lucky Strike hydrothermal field, Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Chemical Geology 2008, 247, 339–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popoola, S.O.; Han, X.; Wang, Y.; Qiu, Z.; Ye, Y.; Cai, Y. Mineralogical and Geochemical Signatures of Metalliferous Sediments in Wocan-1 and Wocan-2 Hydrothermal Sites on the Carlsberg Ridge, Indian Ocean. Minerals 2019, 9, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eigenvalue | 7.306 | 3.615 | 1.427 | 1.008 |

| Cumulative% | 52.183 | 78.003 | 88.196 | 95.397 |

| Al | 0.925 | −0.320 | −0.160 | −0.113 |

| Fe | −0.427 | −0.182 | 0.757 | 0.354 |

| Mn | −0.110 | 0.977 | −0.062 | −0.055 |

| Zn | −0.301 | −0.067 | 0.064 | 0.935 |

| Cu | −0.119 | −0.262 | 0.566 | 0.698 |

| Mo | −0.356 | 0.794 | 0.420 | 0.088 |

| U | −0.375 | −0.047 | 0.884 | −0.129 |

| Ti | 0.925 | −0.303 | −0.194 | −0.091 |

| Mg | 0.958 | 0.002 | −0.203 | −0.162 |

| K | −0.249 | 0.926 | 0.084 | −0.148 |

| Sc | 0.919 | −0.284 | −0.236 | −0.116 |

| Y | 0.794 | −0.216 | −0.397 | −0.309 |

| Ba | −0.176 | 0.943 | −0.146 | −0.082 |

| Ca | 0.144 | −0.331 | −0.841 | −0.301 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).