Submitted:

12 August 2023

Posted:

14 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Structural details of crayfish axons

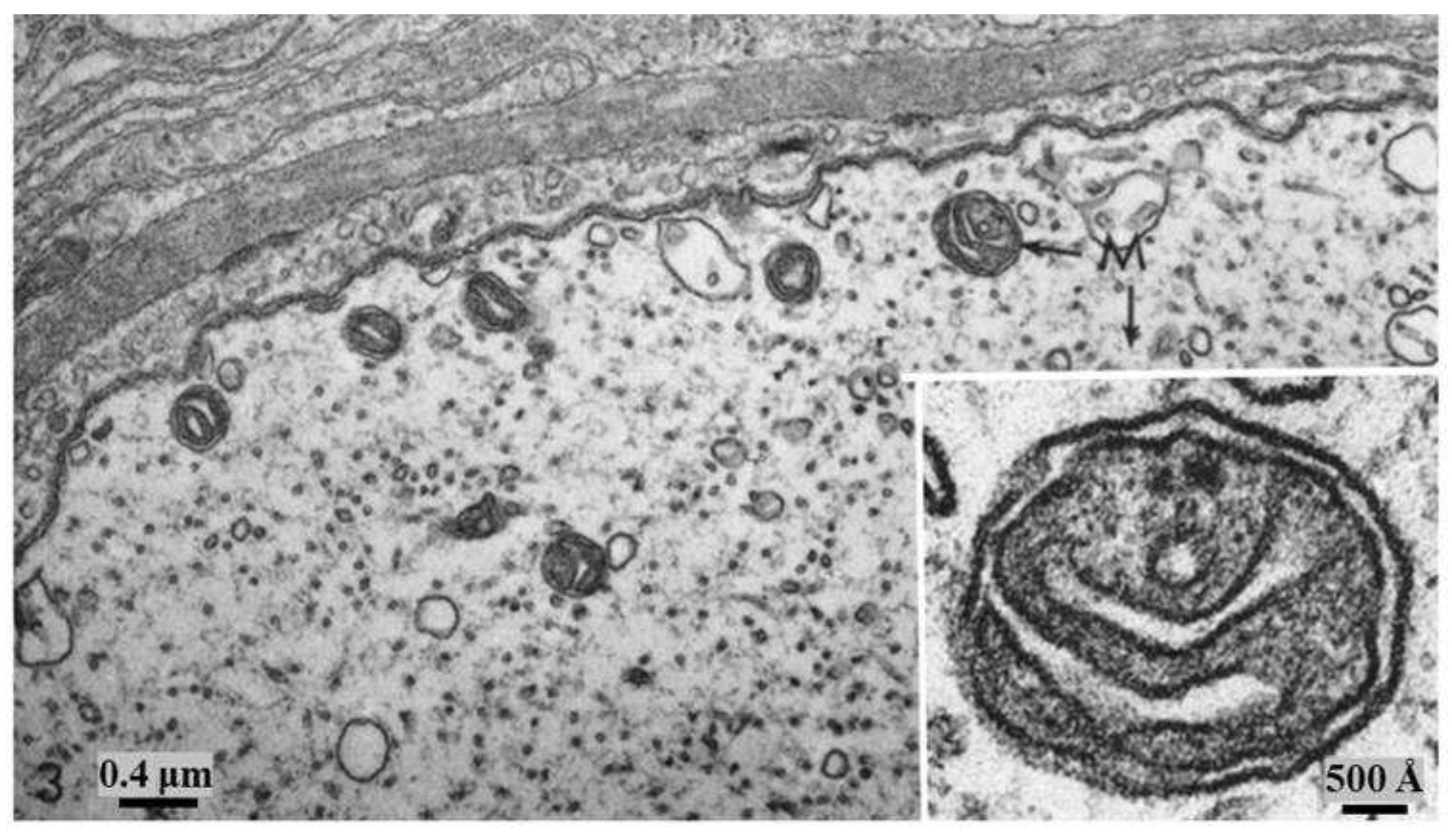

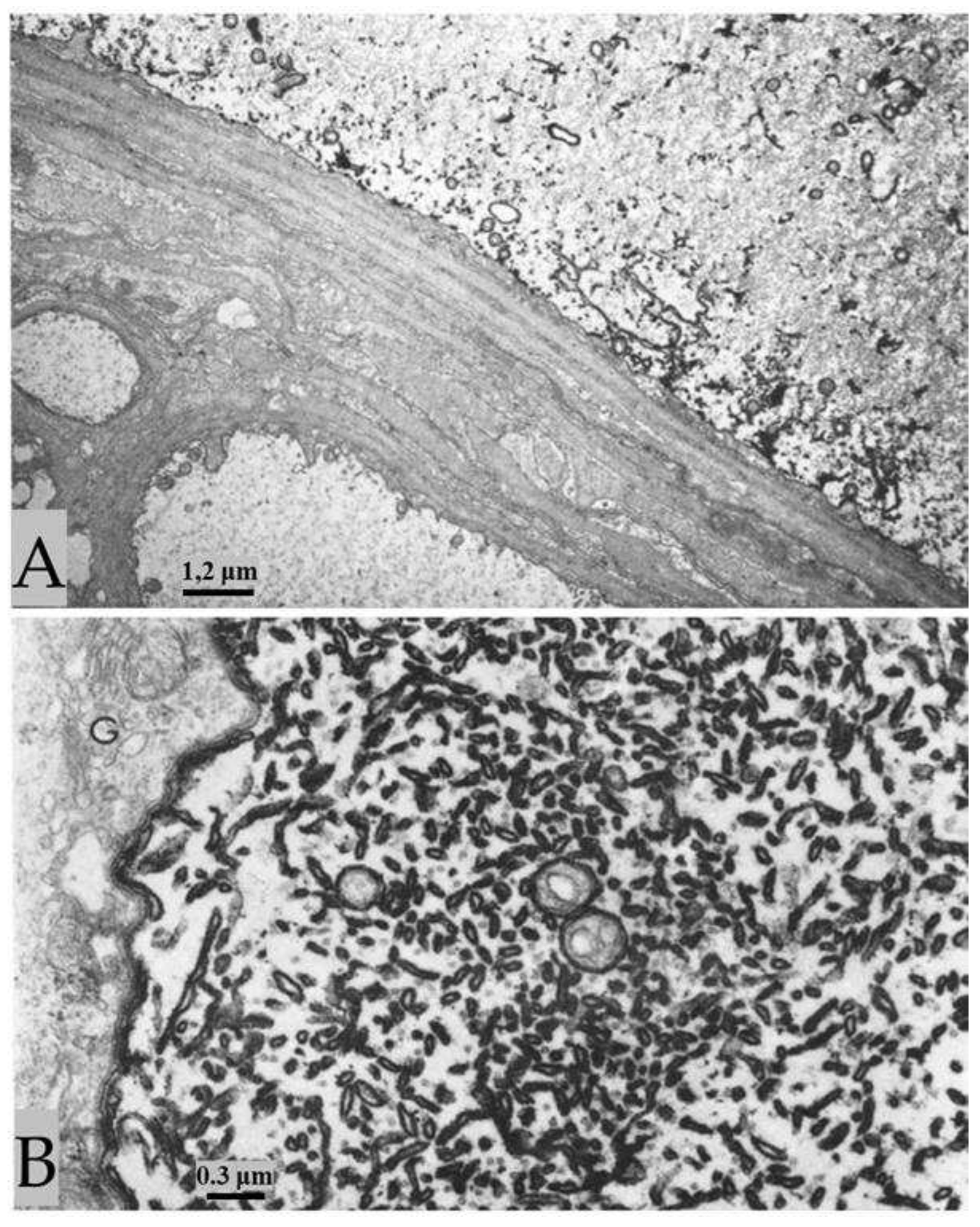

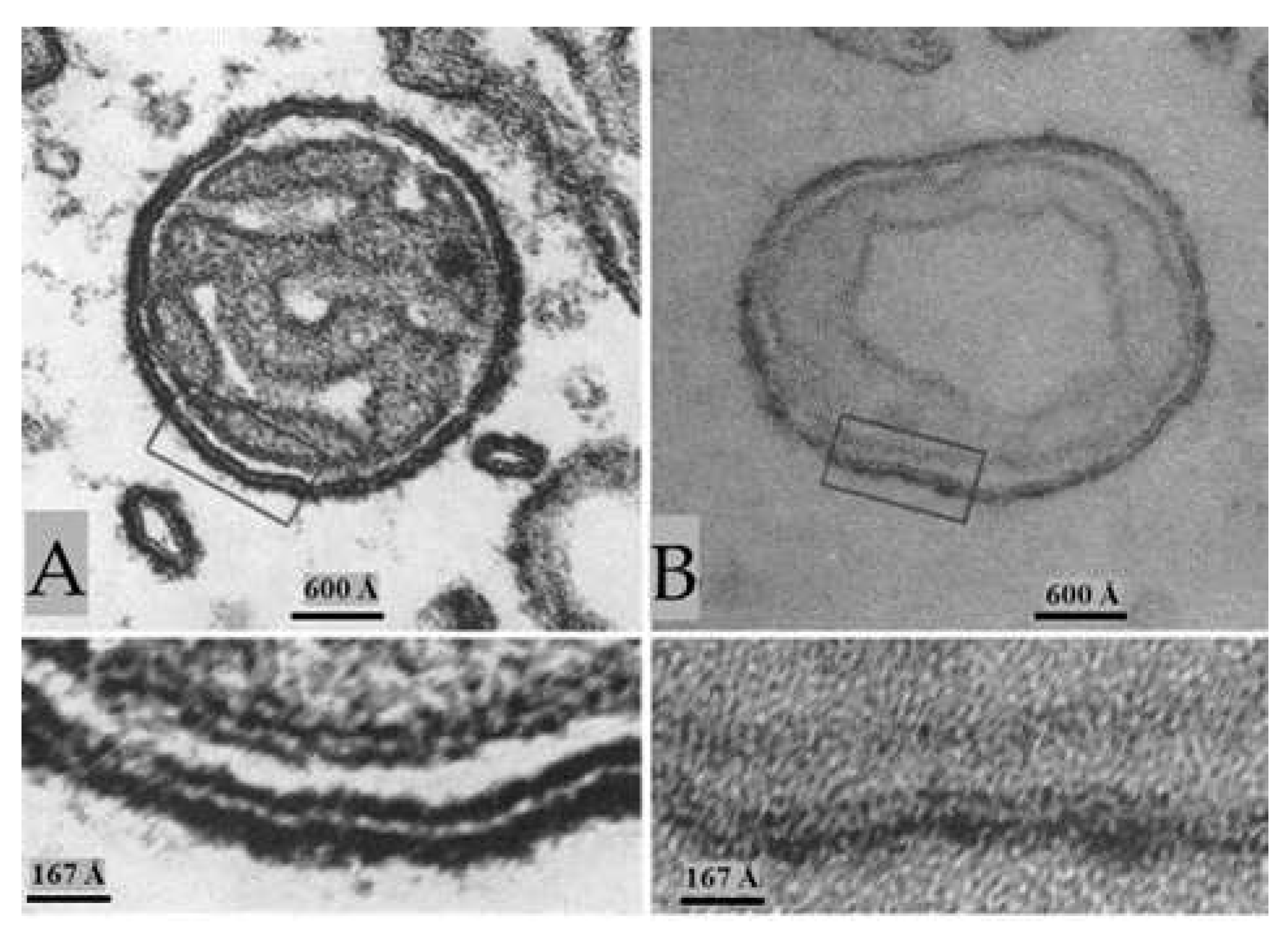

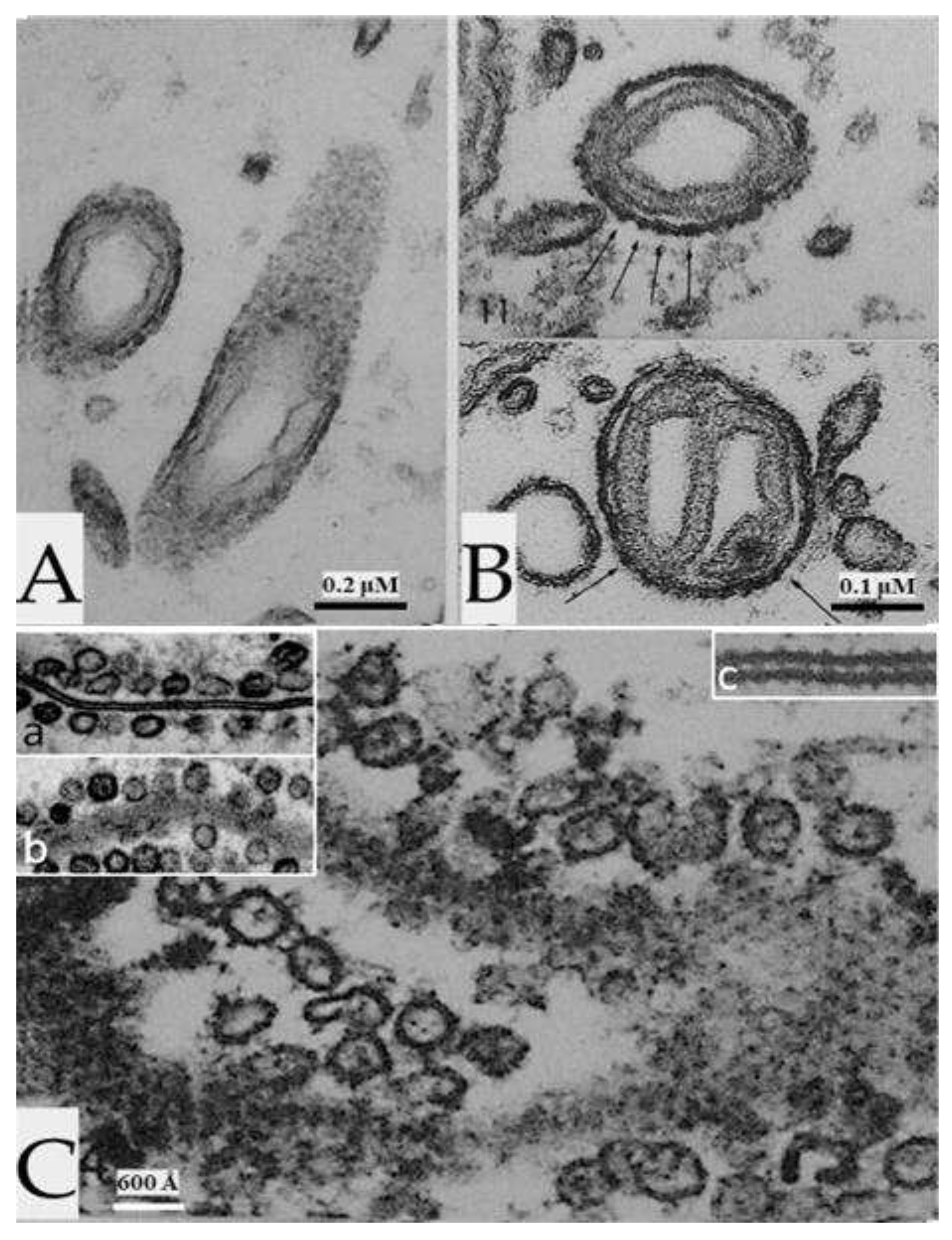

2.1. Fenestrated septa

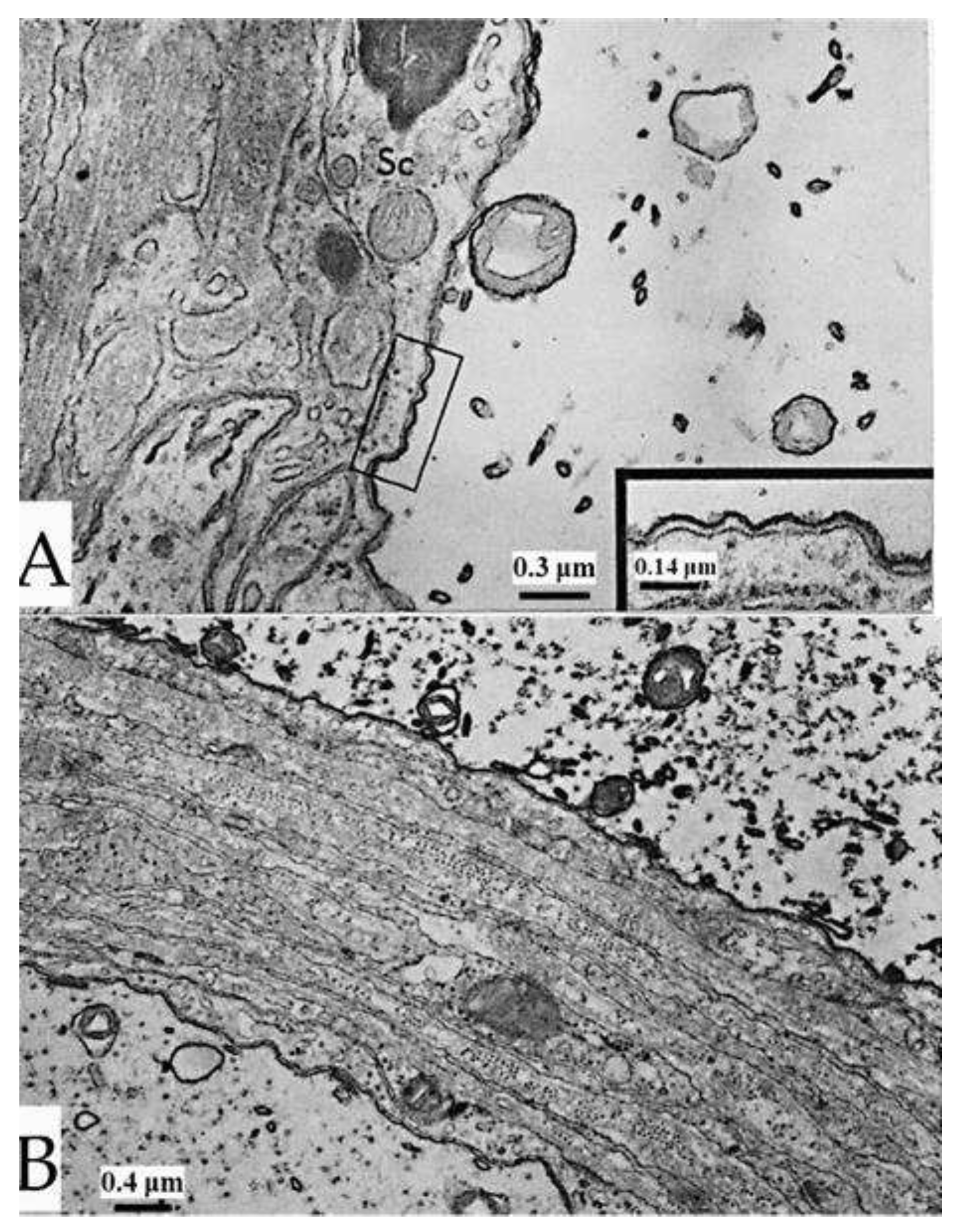

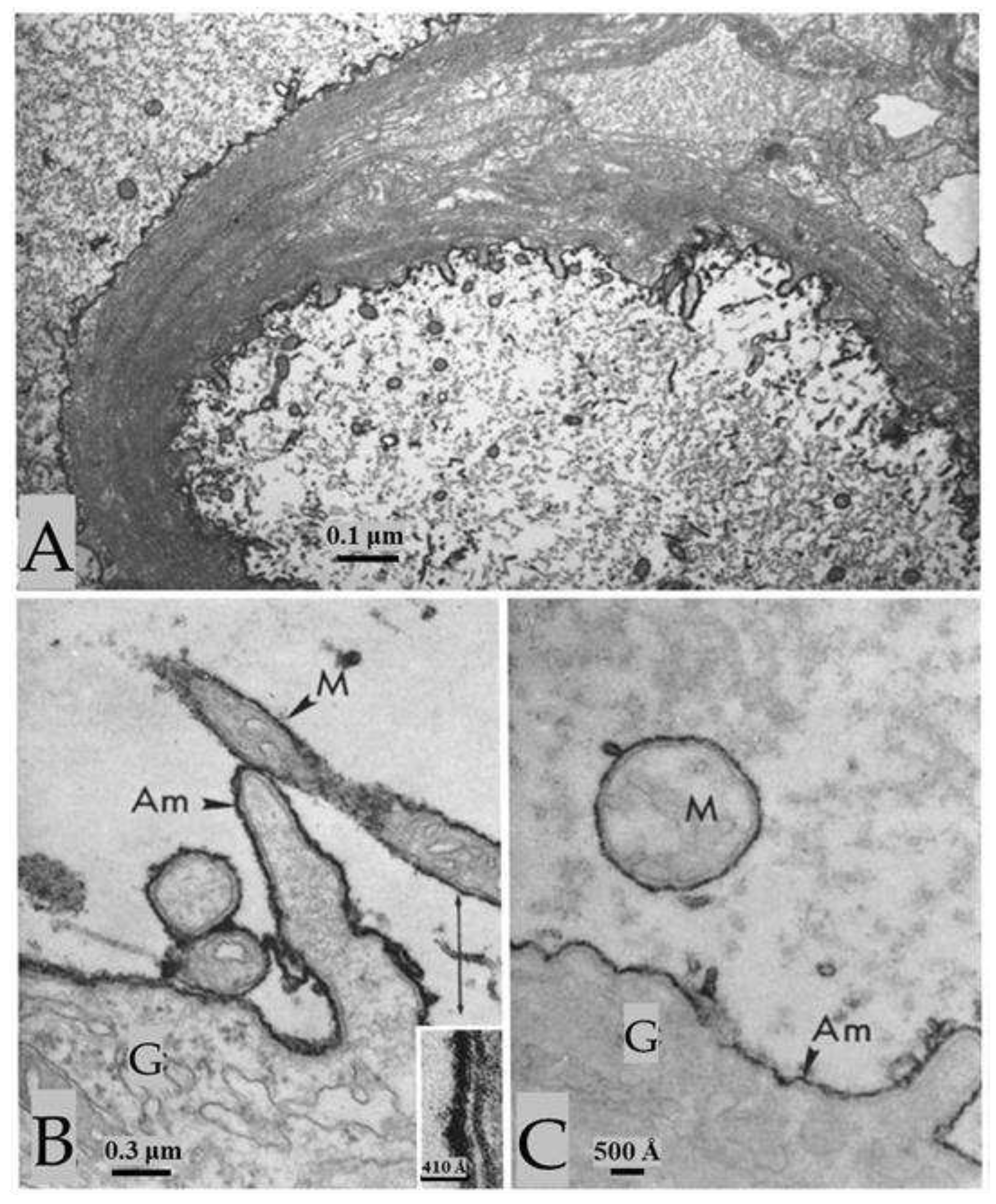

2.2. Structural interaction between axons and sheath-glial cells

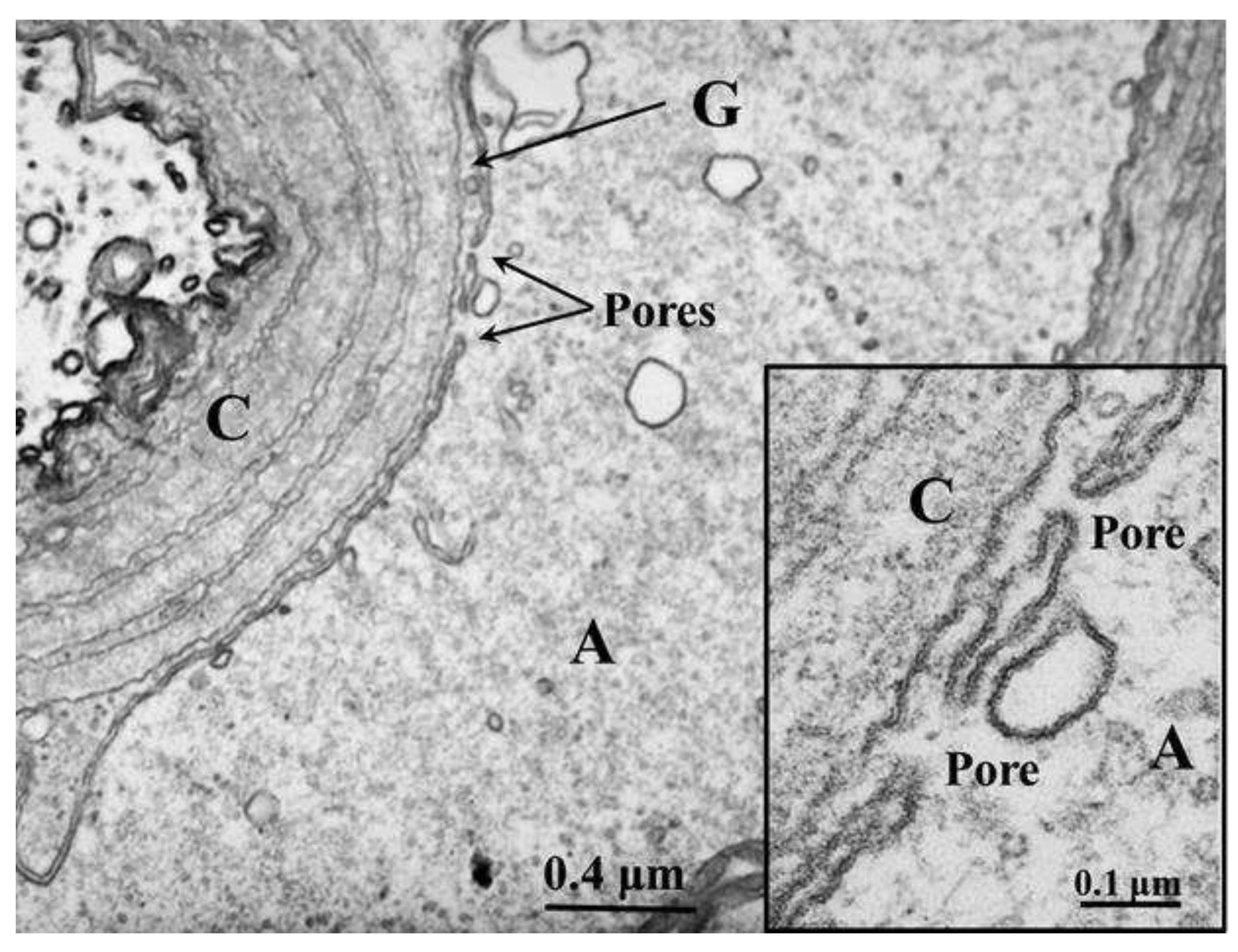

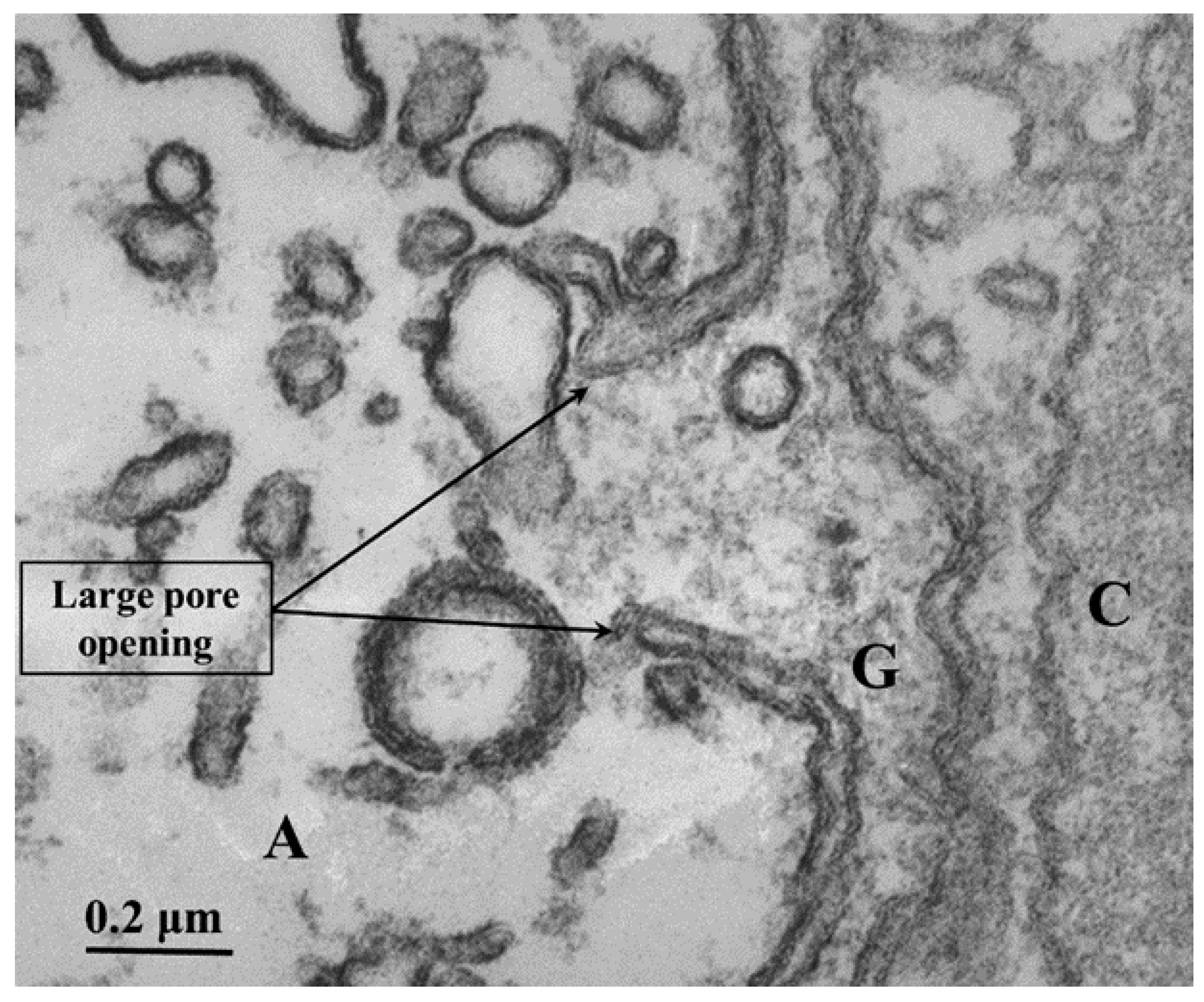

2.3. Membranous pores joining axons to sheath-glial cells

3. Structural changes in electrically stimulated axons

3.1. Historical Background

3.2. Increased electron density (osmiophilia) in membranes of electrically stimulated axons

3.3. Increased electron density (osmiophilia) in membranes of asphyxiated axons

3.4. Increased electron opacity (osmiophilia) in membranes of axons treated with sulfhydryl (-SH) reagents

4. Why does membrane’s osmiophilia increase in electrically stimulated axons?

5. Conclusion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Peracchia:, C. , A system of parallel septa in crayfish nerve fibers. J. Cell Biol 1970, 44 (1), 125–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peracchia, C.; Robertson, J. D. , Increase in osmiophilia of axonal membranes of crayfish as a result of electrical stimulation, asphyxia, or treatment with reducing agents. J. Cell Biol 1971, 51(1), 223–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peracchia, C. , Excitable membrane ultrastructure. I. Freeze fracture of crayfish axons. J. Cell Biol 1974, 61(1), 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peracchia, C. , Direct communication between axons and sheath glial cells in crayfish. Nature 1981, 290(5807), 597–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peracchia, C., Potential Role of Fenestrated Septa in Axonal Transport of Golgi Cisternae and Gap Junction Formation/Function. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24, (6).

- Okada, Y.; Sato-Yoshitake, R.; Hirokawa, N. , The activation of protein kinase A pathway selectively inhibits anterograde axonal transport of vesicles but not mitochondria transport or retrograde transport in vivo. J Neurosci 1995, 15(4), 3053–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eugenin, E.; Camporesi, E.; Peracchia, C., Direct Cell-Cell Communication via Membrane Pores, Gap Junction Channels, and Tunneling Nanotubes: Medical Relevance of Mitochondrial Exchange. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23, (11).

- Lasek, R. J.; Gainer, H.; Barker, J. L., Cell-to-cell transfer of glial proteins to the squid giant axon. The glia-neuron protein trnasfer hypothesis. J Cell Biol 1977, 74, (2), 501-23.

- Lasek, R. J.; Gainer, H.; Przybylski, R. J. , Transfer of newly synthesized proteins from Schwann cells to the squid giant axon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1974, 71(4), 1188–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, M.; Green, M. R. , Autoradiographic studies of uridine incorporation in peripheral nerve of the newt, Triturus. J Morphol 1968, 124(3), 321–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singer, M.; Salpeter, M. M. , The transport of 3H-l-histidine through the Schwann and myelin sheath into the axon, including a reevaluation of myelin function. J Morphol 1966, 120(3), 281–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viancour, T. A.; Bittner, G. D.; Ballinger, M. L. , Selective transfer of Lucifer yellow CH from axoplasm to adaxonal glia. Nature 1981, 293(5827), 65–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodgkin, A. L.; Huxley, A. F. , Propagation of electrical signals along giant nerve fibers. Proc. R. Soc. Lond B Biol. Sci 1952, 140(899), 177–183. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin, A. L.; Huxley, A. F. , Currents carried by sodium and potassium ions through the membrane of the giant axon of Loligo. J. Physiol 1952, 116(4), 449–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgkin, A. L.; Huxley, A. F.; Katz, B. , Measurement of current-voltage relations in the membrane of the giant axon of Loligo. J. Physiol 1952, 116(4), 424–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hodgkin, A. L.; Huxley, A. F.; Katz, B. , Ionic currents underlying activity in the giant axon of the squid. Arch. Sci. Physiol 1949, 3, 129–150. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin, A. L.; Katz, B. , The effect of sodium ions on the electrical activity of giant axon of the squid. J. Physiol 1949, 108(1), 37–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, J. Z. , The functioning of the giant nerve fibres of the squid. J. Exp. Biol 1938, 15, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, K. S. , Dynamic electrical characteristics of the squid axon membrane. Arch. Sci. Physiol 1949, 3, 253–258. [Google Scholar]

- Hille, B. , Ion channels of excitable membranes., 2nd ed.; Sinauer Associates, Inc.: Sunderland, Mass. USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Bethe, A. J. T. , Allgemeine Anatomie und Physiologie des Nervensystems. V. G. Thieme: Leipzig, Germany, 1903.

- Klinke, j., Über die Bedingungen für das Auftreten eines färberischen Polarisationsbildes am Nerven. Pflügers Arch. 1931, 227, 715-726.

- Hill, D. K.; Keynes, R. D. , Opacity changes in stimulated nerve. J Physiol 1949, 108(3), 278–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D. K., The volume change resulting from stimulation of a giant nerve fibre. J Physiol 1950, 111, (3-4), 304-27.

- Hill, D. K., The effect of stimulation on the opacity of a crustacean nerve trunk and its relation to fibre diameter. J Physiol 1950, 111, (3-4), 283-303.

- Tobias, J. M. , Qualitative observations on visible changes in single frog, squid and other axones subjected to electrical polarization; implications for excitation and conduction. J Cell Comp Physiol 1951, 37(1), 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solomon, S., J. M. Tobias, J.M., Thixotropy of axoplasm and effect of activity on light emerging from an internally lighted giant axon J. Cell. Comp. Physiol. 1960, 55, 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, L. B.; Keynes, R. D.; Hille, B. , Light scattering and birefringence changes during nerve activity. Nature 1968, 218(5140), 438–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, L. B.; Keynes, R. D. , Evidence for structural changes during the action potential in nerves from the walking legs of Maia squinado. J Physiol 1968, 194(2), 85–6P. [Google Scholar]

- Tasaki, I.; Watanabe, A.; Sandlin, R.; Carnay, L. , Changes in fluorescence, turbidity, and birefringence associated with nerve excitation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1968, 61(3), 883–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, G.; Laurence, D. J. , Fluorescent indicators of adsorption in aqueous solution and on the solid phase. Biochem J 1954, 56(325th Meeting), xxxi. [Google Scholar]

- Duke, J. A.; McKay, R.; Botts, J. , Conformational change accompanying modification of myosin ATPase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1966, 126(3), 600–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasaki, II; Carnay, L.; Watanabe, A., Transient changes in extrinsic fluorescence of nerve produced by electric stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1969, 64, (4), 1362-8.

- Howarth, J. V.; Keynes, R. D.; Ritchie, J. M. , The origin of the initial heat associated with a single impulse in mammalian non-myelinated nerve fibres. J Physiol 1968, 194(3), 745–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iwasa, K.; Tasaki, I. , Mechanical changes in squid giant axons associated with production of action potentials. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1980, 95(3), 1328–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasa, K.; Tasaki, I.; Gibbons, R. C. , Swelling of nerve fibers associated with action potentials. Science 1980, 210(4467), 338–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasaki, I.; Iwasa, K.; Gibbons, R. C. , Mechanical changes in crab nerve fibers during action potentials. Jpn J Physiol 1980, 30(6), 897–905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasaki, I.; Iwasa, K. , Rapid pressure changes and surface displacements in the squid giant axon associated with production of action potentials. Jpn J Physiol 1982, 32(1), 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasaki, I.; Iwasa, K. , Further studies of rapid mechanical changes in squid giant axon associated with action potential production. Jpn J Physiol 1982, 32(4), 505–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasaki, I.; Byrne, P. M. , Heat production associated with a propagated impulse in bullfrog myelinated nerve fibers. Jpn J Physiol 1992, 42(5), 805–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasaki, I.; Kusano, K.; Byrne, P. M. , Rapid mechanical and thermal changes in the garfish olfactory nerve associated with a propagated impulse. Biophys J 1989, 55(6), 1033–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasaki, I.; Byrne, P. M. , Volume expansion of nonmyelinated nerve fibers during impulse conduction. Biophys J 1990, 57(3), 633–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasaki, I.; Byrne, P. M. , Rapid structural changes in nerve fibers evoked by electric current pulses. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1992, 188(2), 559–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peracchia, C. , Low resistance junctions in crayfish. I. Two arrays of globules in junctional membranes. J. Cell Biol 1973, 57(1), 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peracchia, C.; Mittler, B. S. , Fixation by means of glutaraldehyde-hydrogen peroxide reaction products. J. Cell Biol 1972, 53(1), 234–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riemersma, J. C. , Osmium tetroxide fixation of lipids for electron microscopy. A possible reaction mechanism. Biochim Biophys Acta 1968, 152(4), 718–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahr, G. F. , Osmium tetroxide and ruthenium tetroxide and their reactions with biologically important substances. Electron stains. III. Exp Cell Res 1954, 7(2), 457–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanker, J. S.; Seaman, A. R.; Weiss, L. P.; Ueno, H.; Bergman, R. A.; Seligman, A. M. , Osmiophilic Reagents: New Cytochemical Principle for Light and Electron Microscopy. Science 1964, 146(3647), 1039–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanker, J. S.; Kasler, F.; Bloom, M. G.; Copeland, J. S.; Seligman, A. M. , Coordination polymers of osmium: the nature of osmium black. Science 1967, 156(3783), 1737–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiamvimonvat, N.; O'Rourke, B.; Kamp, T. J.; Kallen, R. G.; Hofmann, F.; Flockerzi, V.; Marban, E. , Functional consequences of sulfhydryl modification in the pore-forming subunits of cardiovascular Ca2+ and Na+ channels. Circ Res 1995, 76(3), 325–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Welzel, G.; Schuster, S. , Long-term potentiation in an innexin-based electrical synapse. Sci Rep 2018, 8(1), 12579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marquis, J. K.; Mautner, H. G. , The effect of electrical stimulation on the action of sulfhydryl reagents in the giant axon of squid: suggested mechanisms for the role of thiol and disulfide groups in electrically-induced conformational changes. J Membr Biol 1974, 15(3), 249–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, H. M. , Effects of sulfhydryl blockade on axonal function. J Cell Comp Physiol 1958, 51(2), 161–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huneeus-Cox, F.; Fernandez, H. L.; Smith, B. H. , Effects of redox and sulfhydryl reagents on the bioelectric properties of the giant axon of the squid. Biophys J 1966, 6(5), 675–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J. J.; Salama, G. , Critical sulfhydryls regulate calcium release from sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Bioenerg Biomembr 1989, 21(2), 283–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oba, T.; Hotta, K. , Silver ion-induced tension development and membrane depolarization in frog skeletal muscle fibres. Pflugers Arch 1985, 405(4), 354–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palade, P., Drug-induced Ca2+ release from isolated sarcoplasmic reticulum. III. Block of Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release by organic polyamines. J Biol Chem 1987, 262, (13), 6149-54.

- Brunder, D. G.; Dettbarn, C.; Palade, P. , Heavy metal-induced Ca2+ release from sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem 1988, 263(35), 18785–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuazaga, C.; del Castillo, J. , Generation of calcium action potentials in crustacean muscle fibers following exposure to sulfhydryl reagents. Comp Biochem Physiol C Comp Pharmacol Toxicol 1985, 82(2), 409–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuazaga, C. , Steinacker, A., del Castillo, J., The role of sulfhydryl and disulfide groups of membrane proteins in electrical conduction. Puerto Rico Health Sciences Journal 1984, 3(3), 125–139. [Google Scholar]

- Kirsten, E. B.; Kuperman, A. S. , Effects of sulphydryl inhibitors on frog sartorius muscle: N-ethylmaleimide. Br J Pharmacol 1970, 40(4), 827–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasselbach, W.; Elfvin, L. G. , Structural and chemical asymmetry of the calcium-transporting membranes of the sarcotubular system as revealed by electron microscopy. J Ultrastruct Res 1967, 17(5), 598–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perkins, M. S.; Wright, E. B., The crustacean axon. I. Metabolic properties: ATPase activity, calcium binding, and bioelectric correlations. J Neurophysiol 1969, 32, (6), 930-47.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).