1. Introduction

Stroke is among the most prevalent diseases worldwide, however, despite continuous efforts, many agents that have been tested effective in preclinical models failed in clinical trials due to translation of efficacy and safety issues (1). To date, recanalization interventions to remove the clot with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) or mechanical endovascular thrombectomy (EVT) are the only treatments available for ischemic stroke patients. Restoring blood flow after prolonged ischemia causes reperfusion injury, which generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) to damage the brain cells (2) and exert deleterious effects with hemorrhagic transformation (3). Therefore, the current guidelines for recanalization interventions are recommended within 4.5-6 h of stroke onset (4), although recently the window of EVT has been elongated to 6-24 h from the onset of ischemic stroke for patients with a mismatch between clinical deficit and infarct (5). The short therapeutic window severely limits the stroke patients to receive effective treatments, where only 11.8% received tPA and 5.7% received EVT (6). Thus, there is an unmet need to develop more effective stroke therapies.

Inflammatory responses play a significant role in brain injury and post-injury recovery following various pathological conditions (7-9) including ischemic stroke (10, 11). Currently, no therapy is available for reducing inflammation after stroke (12). Upon ischemic stroke, microglial cells mediate the main innate immune responses, with morphological changes (such as process retraction, etc.) in the ischemic penumbra from as early as 30 min to 1 h (10), and with increased cell counts peaking at 3-7 d post-stroke (13), which remained elevated at 2-3 weeks post-stroke (14). During microglial activation, they can release inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, IFN-γ, iNOS, etc.) (15-17), or simultaneously, can dynamically regulate their adaptive function by releasing restorative cytokines/growth factors (TGF-beta, IL-10, BDNF, GDNF), clearing ischemic tissue debris through phagocytosis, and promoting tissue repair (17-19). The dynamic change of microglial functions is crucial for post-stroke brain repair and functional outcome improvement (13, 20, 21). Thus, targeting inflammation including modulating microglial functions presents as a promising treatment for stroke with a wider therapeutic window (2).

Na+/H+ exchanger isoform-1 (NHE1) mediates electroneutral transport of H+ efflux in exchange of Na+ influx and thus regulates the intracellular pH (pHi), which is essential in the sustained activation of NADPH oxidase (NOX) for ROS productions in post-ischemic neurons and astrocytes (22, 23). We recently reported that NHE1 protein is also required for microglial activation during the respiratory burst (24, 25). Selective deletion of microglial Nhe1 in the Cx3cr1-CreER+/-;Nhe1flox/flox mice reduced microglial pro-inflammatory responses, elevated their phagocytic activity, enhanced synaptic pruning, and improved white matter myelination, altogether contributing to significant neurological function recovery after ischemic stroke (13, 26). In the current study, we investigated the therapeutic efficacy of post-stroke administration of two potent NHE1 protein inhibitors Cariporide (HOE642) and Rimeporide, with a delayed administration regimen at 24 h post-stroke. Rimeporide emerges as a first-in-class NHE-1 inhibitor currently undergoing phase I clinical trial for Duchene Muscular Dystrophy (27). We found that post-stroke administration of HOE642 or Rimeporide in the adult C57BL/6J mice did not reduce the ischemic infarct volume, but reduced microglial inflammation, improved oligodendrogenesis and white matter myelination, and accelerated sensorimotor and cognitive recovery after ischemic stroke. Our study identifies targeting NHE1 protein as a novel strategy to reduce neuroinflammation and white matter damage and improve post-stroke recovery.

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Animals

All animal experiments and procedures were approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, and reported in accordance with the Animal Research: Reporting In Vivo Experiments (ARRIVE) guidelines (28). Animals were provided with food and water ad libitum and maintained in a temperature-controlled environment in a 12/12 h light-dark cycle. All efforts were made to minimize animal suffering and the number of animals used.

2.2. Drug administration

C57/BL6J mice (male and female) at 2–3 months old (Jackson Laboratory, Strain# 000664) were used in the study. HOE642 (Cariporide, Sigma-Aldrich, USA) or Rimeporide (EMD-87580, MedChemExpress, USA) was dissolved at 1 mg/ml in DMSO as stock solution and diluted to 0.025 mg/ml in PBS immediately before injection. 2.5% DMSO in PBS was used as vehicle control (Veh). Veh, HOE642, or Rimeporide was administered at 0.3 mg/kg body weight/day by intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections, with an initial dose at 24 h post-stroke, followed by twice per day (b.i.d.) injections (at least 8 h apart) for consecutive 7 d. To test a continued administration regimen after stroke, osmotic mini-pumps (Alzet, model# 2001, Durect corporation, USA) were used to deliver Rimeporide, which was dissolved at 5 mg/ml in DMSO as stock solution and diluted to 0.25 mg/ml in PBS immediately before loading. The osmotic pumps were then implanted subcutaneously to achieve a constant deliver at 0.3 mg/kg/day (at a rate of 1.0 µl/hr) from 24 h to 7 d post-stroke. 5% DMSO in PBS was used as Veh control in the osmotic pump study.

2.3. Transient focal ischemia model

Transient focal cerebral ischemia was induced by 60 min transient occlusion of the left middle cerebral artery (tMCAO) as described before (13, 26). Please see Supplemental Materials for detailed surgical procedures.

2.4. 2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) staining

Mice were euthanized with overdose of CO2 at 3 d post-stroke, and the mouse brains were dissected and cut into 4 coronal slices of 2 mm thickness before staining with 2% 2,3,5-triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC, Sigma, USA) at 37 °C for 15 min, as described previously (13). Measurement for infarct volume and brain swelling was performed as described before (13). Please see Supplemental Materials for detailed methods.

2.5. Neurological function tests

Neurological functional deficits in mice were screened in a blinded manner with neurological scoring. Sensorimotor functions were measured with rotarod accelerating test, foot-fault test, adhesive contact test and adhesive removal test, and cognitive functions were determined with open field test, y-maze spontaneous alternation test and y-maze novel spatial recognition test, all considered reliable for identifying and quantifying neurological functional deficits in rodent models (13, 26, 29). Please see Supplemental Materials for detailed methods.

2.6. Flow cytometry

Flow cytometry was conducted to investigate microglial inflammatory profiles at 3 d post-stroke. Briefly, single cell suspensions were obtained from contralateral (CL) and ipsilateral (IL) brain tissues using an enzymatic tissue dissociation kit (Miltenyi Biotech Inc., Germany) before centrifuging through a 30/70 Percoll (GE Healthcare, USA) gradient solution to remove myelin, as described before (13, 26). Cell were subsequently stained with BUV395-conjugated CD11b (1:400, BD Biosciences), PerCP-Cy5.5-conjugated CD45 (1:400, BioLegend), eFluor450-conjugated CD16/32 (1:400, Affymetrix eBioscience), FITC-conjugated CD206 (1:400, BioLegend), Alexa 700-conjugated CD86 (1:400, BD Biosciences), PE-conjugated Ym1 (1:400, Abcam), and BV605-conjugated CD68 (1:400, BioLegend) antibodies for 20 min at 4oC in the dark. At least 10,000 events were recorded from each hemispheric sample using an LSR Fortessa flow cytometer and analyzed with FlowJo software. Please see Supplemental Materials for detailed methods.

2.7. Immunofluorescent staining

Mouse brains were fixed and collected after transcardial perfusions with ice-cold PBS and 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), as described previously (13, 26). The brains were post-fixed overnight in 4% PFA and cryoprotected in 30% sucrose before sectioned at 25 μm thickness using a Leica SM2010R microtome (Leica, Germany) for immunofluorescent staining. Fluorescent images were captured under 40x objective lens using a Nikon A1R confocal microscope (Nikon, Japan). Identical digital imaging acquisition parameters were used and images were obtained and analyzed in a blinded manner throughout the study. Please see Supplemental Materials for detailed methods.

2.8. Data analysis

Unbiased study design and analyses were used in all the experiments. Blinding of investigators to experimental groups were maintained until data were fully analyzed whenever possible. Data were expressed as mean ± SD or SEM and all data were tested for normal distribution. Not normally distributed data were analyzed by Mann-Whitney U test or other appropriate alternative tests according to the data (GraphPad Prism, USA). Two-tailed Student’s t-test with 95% confidence was used when comparing two conditions. For more than two conditions, one-way or two-way ANOVA analysis was used, depending on the data. A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were included unless appropriate outlier analysis suggested otherwise.

3. Results

3.1. Administration of NHE1 inhibitor HOE642 at 24 h post-stroke improved motor-sensory and cognitive functions in C57/BL6J mice

We first assessed the therapeutic efficacy of post-stroke administration of the potent NHE1 inhibitor HOE642 on motor-sensory and cognitive function recovery in C57/BL6 mice. We tested a regiment of administration of Vehicle (Veh, 2.5% DMSO) or HOE642 (0.3 mg/kg/day at 0.025 mg/ml, i.p., b.i.d.) starting at 24 h post-tMCAO (

Figure 1A) with an initial dose at 24 h post-stroke, followed by b.i.d. treatment for consecutive 7 days. The HOE642-treated mice showed a slightly improved survival rate than the Veh-treated mice (74% vs. 62%, p > 0.05), with similar body weight changes (

Figure S1A). In the initial 4 days after ischemic stroke, both Veh- and HOE642-treated mice exhibited similarly poor neurological scoring (p > 0.05). However, the HOE642-treated mice started to recover significantly faster from day 5 post-stroke (p < 0.05,

Figure 1B). These HOE642-treated mice also exhibited significant improvements in motor-sensory functions in the rotarod accelerating test as early as 3 d post-stroke (p < 0.05), foot-fault test at 2 d post-stroke (p < 0.05), and adhesive contact/removal tests at 1 d post-stroke (p < 0.01) (

Figure 1C). Moreover, at 28 d post-stroke, the HOE-treated mice displayed significantly improved short-term spatial working memory in the y-maze spontaneous alternation test (p < 0.01,

Figure 1D), and improved long-term recognition memory in the novel object recognition test (p < 0.05,

Figure 1E), without affecting locomotor activities or anxiety (

Figure S1B). These findings suggest that blockade of NHE1 protein activity by HOE642 starting at 24 h post-stroke significantly improved both motor-sensory and cognitive function recovery after ischemic stroke.

3.2. Post-stroke administration of HOE642 did not reduce ischemic infarct or neuronal death but enhanced white matter myelination

Given NHE1 protein is ubiquitously expressed in all brain cell types, including neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and OLs (30), we first assessed if the Veh- or HOE642-treated mice displayed differential acute neuronal damage at 3 d post-stroke. TTC staining in

Figure 2A,B showed that the Veh- and HOE642-treated mice exhibited comparable ischemic infarct size and hemispheric swelling (p > 0.05). Since neurogenesis in peri-infarct tissues can contribute to better neurological function in stroke mice (13), we further examined neuronal counts in the ischemic core, peri-infarct area in the ipsilateral (IL) hemisphere, and the contralateral (CL) hemisphere with immunostaining analysis of dendritic marker MAP2 and neuronal marker NeuN expression. Interestingly, compared to the CL hemispheres, both peri-lesion cortex and ischemic core of the Veh- or HOE642-treated mice showed similar loss in MAP2 intensity or NeuN

+ neuron counts (p < 0.05, CL vs. Perilesion or Core; p > 0.05, Veh vs. HOE) (

Figure 2C,D). These findings suggest that post-stroke administration of HOE642 did not reduce neuron degeneration nor acute infarct formation in the ischemic brains. As no significant difference was detected in gray matter damage, we further investigated whether an improved white matter repair could account for the accelerated neurological function recovery in the HOE642-treated stroke mice.

Figure 3A showed that at 3 d post-stroke, the HOE642-treated mice exhibited a 39.3% increase in the corpus callosum (CC) thickness (p < 0.01,

Figure 3A), with higher MBP protein expressions (p < 0.01) and APC

+ mature OL counts (p < 0.01) in both CL and IL hemispheres of CC, compared to the Veh-treated stroke mice (

Figure 3B). In addition, the HOE642-treated mice also showed increased OL genesis with higher NG2

+Olig2

+ OPC counts (p < 0.0001), elevated Ki67

+Olig2

+ OL proliferation (p < 0.0001), and reduced Caspase3

+Olig2

+ OL apoptosis (p < 0.0001) in both hemispheres of CC at 3 d post-stroke, which persisted to 7 d post-stroke (

Figure 3C). These data indicate that a delayed regimen of pharmacological inhibition of NHE1 protein activity with HOE642 from 24 h post-stroke attenuated OL apoptosis and stimulated OL genesis, leading to the improved white matter myelination in post-stroke brains.

3.3. Efficacy of a novel NHE1 inhibitor Rimeporide in improving neurological functions in C57/BL6 mice after ischemic stroke

Next we also explored the efficacy of a novel NHE1 inhibitor Rimeporide (RIM) for ischemic stroke treatment in mice. Due to its short half-life averaging about 3-4 h (27), we utilized a continuous delivery approach of osmotic mini-pump to maintain stable plasma levels above pharmacological levels. Osmotic mini-pumps with Veh (5% DMSO in PBS) or 2.1 mg/kg of RIM were implanted subcutaneously in mice at 1-7 d after stroke (

Figure 4A). Survival rate and body weight changes were similar between the Veh- and RIM-treated mice (

Figure S2A). Ischemic infarct assessment at 3 d post-stroke showed that RIM treatments did not reduce infarct volume but decreased edema formation (p = 0.10), compared to the Veh treatment (

Figure 4B,C). In addition, the RIM-treated mice exhibited faster motor function improvements in neurological scoring and rotarod accelerating test from 2-14 d post-stroke (

Figure 5D,E), and improved memory in the y-maze spontaneous alternation test and the novel spatial recognition test at 30 d post-stroke, compared to the Veh-treated mice (p < 0.05,

Figure 4H,I). These data suggest that delayed administration of RIM at 24 h post-stroke is equally effective in improving neurological functions after stroke.

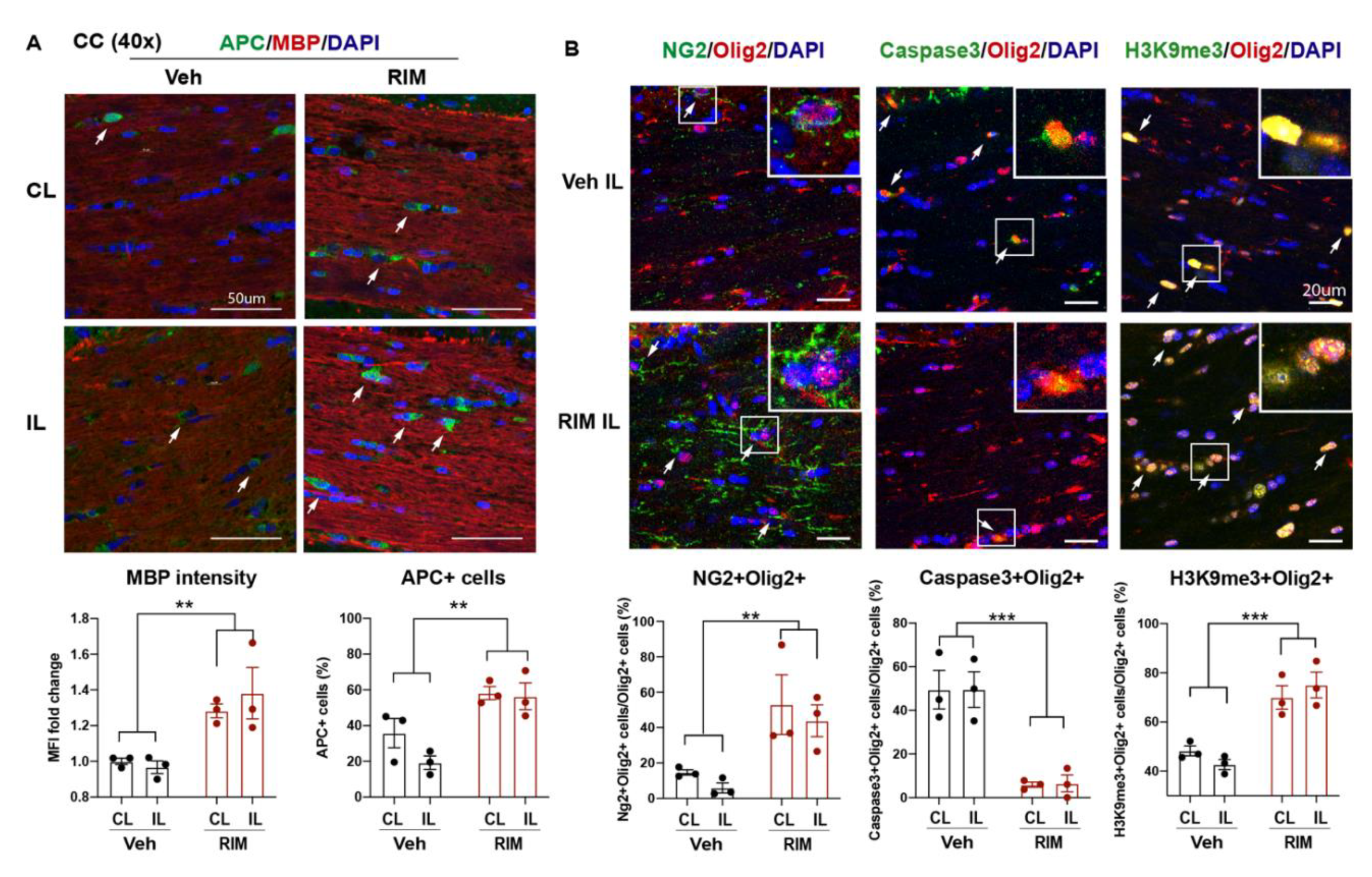

To determine whether the RIM-treated mice exhibited similar effects as the HOE-treated mice, we also assessed white matter changes in the RIM-treated mice at 3 d post-stroke.

Figure 5A showed that the RIM-treated mice showed 1.4-fold increase in the MBP protein expression (p < 0.01) and 2.9-fold increase in the APC

+ mature OL counts (p < 0.01) in both hemispheres of CC, compared to the Veh-treated mice (

Figure 5A). Concurrently, the RIM-treated mice also exhibited increased OL genesis with higher NG2

+Olig2

+ OPC counts (p < 0.01), reduced Caspase3

+Olig2

+ OL apoptosis (p < 0.0001), and enhanced H3K9me3

+Olig2

+ OL differentiation (p < 0.001) in both hemispheres of CC at 3 d post-stroke (

Figure 5B). Taken together, these data clearly demonstrate that delayed administration of Rimeporide to block NHE1 protein activity from 24 h post-stroke stimulated OL genesis and differentiation, while reducing OL apoptosis, leading to improved white matter myelination in post-stroke brains, similar to the HOE-mediated effects.

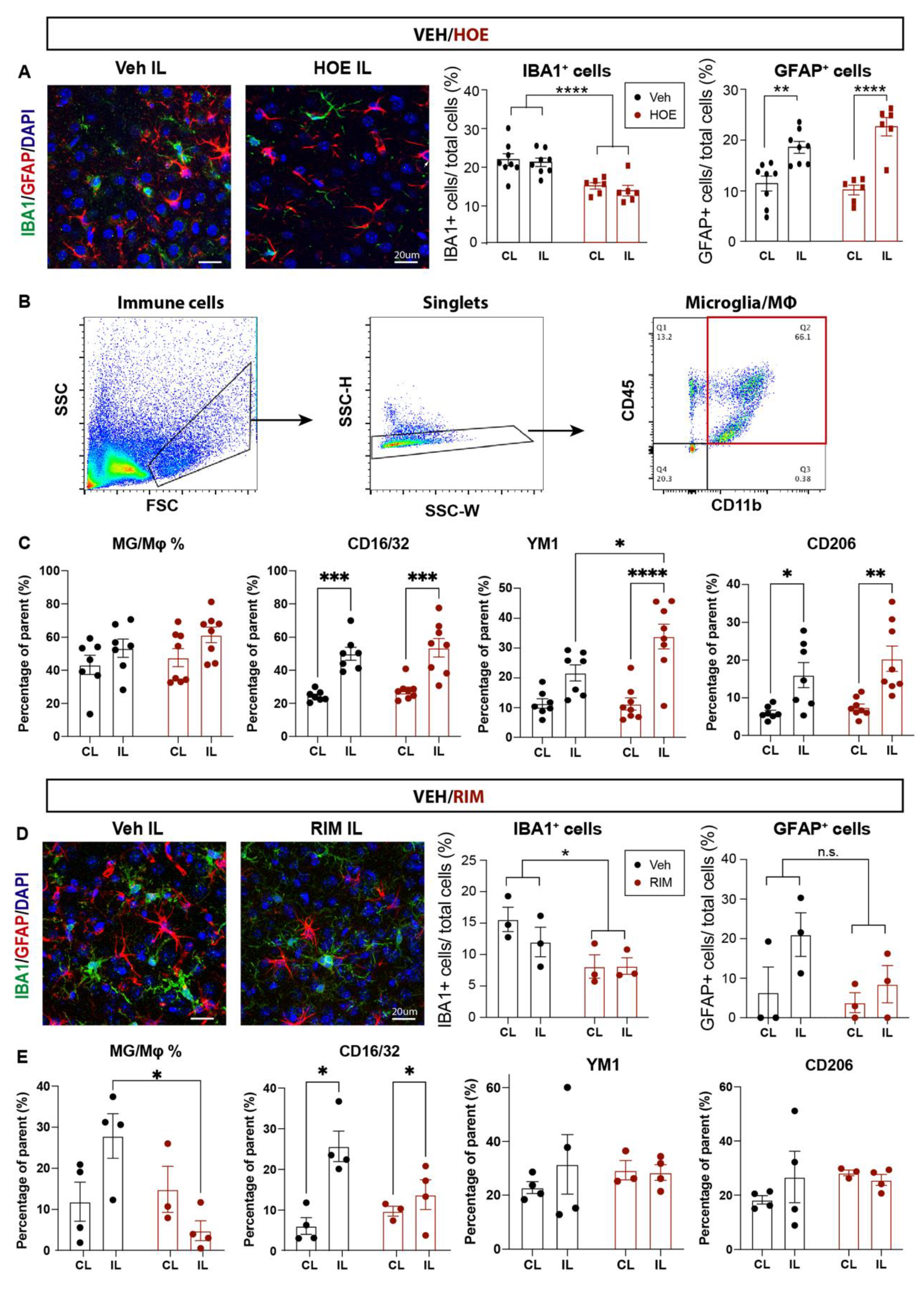

3.4. Reduced microglia-mediated inflammation in stroke brains treated with HOE642 or Rimeporide

We further evaluated neuroinflammation profiles by investigating changes of IBA1

+ microglia and GFAP

+ reactive astrocytes in the Veh-, HOE642- or RIM-treated brains at 3 d post-stroke. As shown in

Figure 6A, the Veh-treated brains displayed abundant IBA1

+ microglia and GFAP

+ reactive astrocytes in the perilesion cortex. In contrast, the HOE642-treated brains exhibited significantly less accumulation of IBA1

+ microglia (p < 0.01), which showed a quiescent ramified morphology, compared to the amoeboid morphology with retracted processes which represents an activated phagocytic phenotype (31) in the Veh-treated brains. In comparison, the cell counts of GFAP

+ reactive astrocytes in the perilesion cortex were comparable between the Veh- and HOE642-treated brains (p > 0.05), though those from the HOE-treated brains displayed thinner processes indicating less astrogliosis reactivity (32) (

Figure 6A). We further analyzed the inflammatory profiles of CD11b

+CD45

+ microglia/macrophages via flow cytometry. Both Veh- and HOE-treated brains showed similar counts of CD11b

+CD45

+ microglia/macrophages, however those in the ischemic hemisphere of HOE-treated brains displayed significantly increased anti-inflammatory marker Ym1, compared to those from the Veh-treated brains (p < 0.05,

Figure 6B,C). Taken together, these data demonstrate that post-stroke administration of HOE642 selectively increased microglial/macrophage anti-inflammatory activation, but did not significantly affect astrogliosis in the ischemic brains.

As for the RIM-treated brains, we detected similarly mitigated inflammation with less IBA1

+ microglial cells in the perilesion cortex, compared to the Veh-treated brains at 3 d post-stroke (

Figure 6D). GFAP

+ reactive astrocyte counts remain similar between the Veh- and RIM-treated brains (p > 0.05). Flow cytometry analysis revealed that stroke induced an elevation in CD11b

+CD45

+ microglia/macrophage counts in the Veh-treated brains. However, the RIM-treated brains exhibited a significantly reduced CD11b

+CD45

+ microglia/macrophage counts, without apparent change in the inflammatory marker profiling (

Figure 6E). These data suggest that post-stroke administration of Rimeporide also altered inflammation in stroke brains.

4. Discussion

4.1. Expanded time window and therapeutic efficacy of pharmacological inhibition of NHE1 protein after ischemic stroke

The recent DAWN (DWI or CTP Assessment with Clinical Mismatch in the Triage of Wake-Up and Late Presenting Strokes Undergoing Neurointervention with Trevo) trial has expanded the time window for endovascular thrombectomy treatment to 6-24 h post-ischemic stroke (5). However, the latest guideline for the recommended time window of thrombolysis using tPA is still within 4.5 h of ischemic stroke onset (33). In this study, we tested efficacy of pharmacological inhibition of NHE1 protein with a wider therapeutic window at 24 h post-stroke in adult C57BL/6J mice. Compared to the Veh-control stroke mice, the HOE642-treated mice (with a low dose at 0.15 mg/kg, i.p., b.i.d. for 1-7 post-stroke) showed significantly improved motor-sensory and cognitive functional recovery through 1-28 d post-stroke, with no adverse effects. HOE642 has been tested in the GUARDIAN (Guard During Ischemia Against Necrosis) phase II/III clinical trial for myocardial infarction, showing a 25% reduction of risk in the high-risk patients and reported no serious adverse events in the cariporide-treated group (with a dose of 120 mg, intravenous t.i.d. for 2-7 days) over placebo (34). However, despite of reduced myocardial infarction, it failed in the EXPEDITION (Sodium-Proton Exchange Inhibition to Prevent Coronary Events in Acute Cardiac Conditions) phase III clinical trial due to increased embolic stroke incidents (35), which is likely due to the excessive high dose (180 mg loading dose, then 40 mg/h in 24 h, and 20 mg/h in 48 h, intravenous) and its paradoxical effects on platelet activation (35, 36). Our study with a low dose of HOE642 administrated at 24 h post-stroke indicated the therapeutic potential of pharmacological blockade of NHE1 protein with minimized potential adverse effects.

In terms of Rimeporide (EMD-87580), it has a similar half-life of 3-4 h as HOE642, and has recently been tested as the first-in-class NHE1 inhibitor in a phase Ib clinical trial for Duchene Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) (27). Compared to HOE642, it was considered safe and well-tolerated at a highest dose of 300 mg, t.i.d. (oral administration) with promising outcomes (27). We chose a low dose regimen of 0.3 mg/kg/day after a pilot experiments with 0.3, 0.5 and 1 mg/kg/day (data not shown). To maintain stable plasma levels above pharmacological concentrations, we utilized a continuous delivery approach with osmotic mini-pumps. Interestingly, the RIM-treated mice also exhibited a faster motor-sensory function recovery in the acute to subacute phase after stroke, and better cognitive function in the chronic phase post-stroke, but without improvement in the overall survival or infarct volume, similar to many other studies (37-39). These novel findings are encouraging and present therapeutic potential of Rimeporide in promoting tissue repair and functional recovery after cerebral ischemic stroke.

4.2. NHE1 blockers attenuate neuroinflammation in ischemic stroke

NHE1 protein is a house-keeping pH regulatory protein, mediating electroneutral transport of H+ efflux in exchange of Na+ influx (22). We recently discovered differential roles of NHE1 protein in neurons, microglia, or astrocytes in brain damages after ischemic stroke (13, 23). Selective deletion of neuronal Nhe1 (in CamKIIa-Cre+/-;Nhe1flox/flox mice) or astrocytic Nhe1 (in Gfap-CreER+/-;Nhe1flox/flox mice) both showed significantly reduced ischemic infarct and accelerated neurological functional improvements in a mouse tMCAO model (13, 23), while targeted deletion of microglial Nhe1 in the Cx3cr1-CreER+/-;Nhe1flox/flox mice did not reduce infarct but improved motor-sensory and cognitive behaviors with mitigated acute inflammation and enhanced long-term myelination up to 1 month after ischemic stroke (13, 26). In either HOE642- or RIM-treated stroke mice, no reduction of infarct volume nor neuroprotective effects were observed. As neuronal NHE1 activation occurs early after ischemic injury (within 24 h) (40), we concluded that the delayed administration of either HOE642 or Rimeporide at 24 h post-stroke exerted no neuroprotective effects. We believe that the improved neurological behavior with post-stroke administration of the inhibitors was via alleviating microglial inflammatory responses and protecting white matter tissues. Mismatches between the infarct volume and the severity of clinical deficits are often related to prolonged inflammatory responses and compromised white matter integrity in ischemic stroke patients (5, 41, 42). The peak of microglial responses occurs at 3-7 days post-stroke (13) and remains elevated until 2-3 weeks post-stroke (14). Particularly, NHE1 protein expression in microglial cells remains upregulated to at least 7 days post-stroke (25), allowing for an extended treatment window. Our delayed paradigm of low dose HOE642 at 24 h reduced microglial inflammatory profiles, while delayed administration of Rimeporide reduced microglia/macrophage cell counts without significant alteration in their profiles. These early microglia-mediated inflammation changes were accompanied by increased resistance of white matter tissues to ischemic demyelination injury, with better preserved mature OLs and myelination, along with early elevation of OL proliferation and differentiation, as well as significantly reduced OL apoptosis. These findings clearly show that targeting NHE1 protein by post-stroke HOE642 or Rimeporide administration provides a novel strategy to modulate microglial function for stimulating white matter repair and post-stroke functional recovery.

Regarding cellular mechanisms underlying Rimeporide’s protective effects, in myocardial infarction models, Rimeporide demonstrated positive results in reducing local inflammation (37) and oxidative stress with attenuated reactive oxygen species production via NADPH oxidase and ERK1/2/Akt/GSK-3β/eNOS pathways (44, 45), with no effects observed in reducing the infarct size in hearts (37-39). In addition, Rimeporide has been shown to increase mitochondria respiratory functions with reduced mitochondrial permeability transition (46) and increased biogenesis (47) in myocardial infarction models, which were associated with decreased mitochondrial vulnerability to exogenous Ca2+ mediated by the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) activity coupled with NHE1 stimulation (46, 48). This is in line with our recent report that genetic deletion of Nhe1 boosted mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation capacities in microglia after cerebral stroke (26). Similar protective effects were also observed in models of cardiomyocyte hypertrophy/hereditary cardiomyopathy, where Rimeporide preserved the left ventricle heart functions and prevented early death (49, 50). These studies provide further evidence for the protective effects of Rimeporide after stroke. However, its specific suppression effects on CD11b+/CD45+ microglia/macrophage in stroke brains require further investigation.

The weakness of this study lies in the systemic approach of HOE642 or Rimeporide administration, which could also directly affect OPCs/OLs and exert impact on remyelination. OPCs/OLs have comparably high levels of expressions of Nhe1 gene (51), which is a dominant regulator for their intracellular pH (pHi) (52, 53). The specific roles of NHE1 protein in OPCs/OLs remain unknown, however, the apparent improvements in white matter repair with increased CC thickness, MBP protein expression and mature OL preservation, along with functional recovery after NHE1 inhibitors administration are significant and warrant further study on the roles of NHE1 protein in OPCs/OLs and its relation to regulating OL genesis in stroke brains.

5. Conclusion

Recanalization interventions with short therapeutic windows are the only treatments available for ischemic stroke patients. Targeting inflammation presents as a promising treatment for stroke patients with a wider therapeutic window, however no therapy is currently available for reducing neuroinflammation after stroke. In the current study, blockade of NHE1 protein activity with HOE642 (Cariporide) or Rimeporide at 24 h post-stroke displayed no acute neuroprotection but reduced inflammatory responses, enhanced white matter repair, and improved motor and cognitive function recovery up to 1 month after stroke. Our study identifies targeting NHE1 protein as a novel strategy to reduce neuroinflammation and white matter damage to improve post-stroke recovery.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Health R01NS 48216 (D.S.), VA Research Career Scientist award BX005647 (D.S.), and American Heart Association Career Development Award 933134 (S.S.).

Competing interests

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- Dhir, N.; Medhi, B.; Prakash, A.; Goyal, M.K.; Modi, M.; Mohindra, S. Pre-clinical to Clinical Translational Failures and Current Status of Clinical Trials in Stroke Therapy: A Brief Review. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2020, 18, 596–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandalaneni K, Rayi A, Jillella DV. Stroke Reperfusion Injury. StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) 2023.

- Peña, I.D.; Borlongan, C.; Shen, G.; Davis, W. Strategies to Extend Thrombolytic Time Window for Ischemic Stroke Treatment: An Unmet Clinical Need. J. Stroke 2017, 19, 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powers, W.J.; Derdeyn, C.P.; Biller, J.; Coffey, C.S.; Hoh, B.L.; Jauch, E.C.; Johnston, K.C.; Johnston, S.C.; Khalessi, A.A.; Kidwell, C.S.; et al. American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Focused Update of the 2013 Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke Regarding Endovascular Treatment A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2015, 46, 3020–3035. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Nogueira, R.G.; Jadhav, A.P.; Haussen, D.C.; Bonafe, A.; Budzik, R.F.; Bhuva, P.; Yavagal, D.R.; Ribo, M.; Cognard, C.; Hanel, R.A.; et al. Thrombectomy 6 to 24 Hours after Stroke with a Mismatch between Deficit and Infarct. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 378, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anand, S.K.; Benjamin, W.J.; Adapa, A.R.; Park, J.V.; Wilkinson, D.A.; Daou, B.J.; Burke, J.F.; Pandey, A.S. Trends in acute ischemic stroke treatments and mortality in the United States from 2012 to 2018. Neurosurg. Focus 2021, 51, E2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Vliet, E.A.; Ndode-Ekane, X.E.; Lehto, L.J.; Gorter, J.A.; Andrade, P.; Aronica, E.; Gröhn, O.; Pitkänen, A. Long-lasting blood-brain barrier dysfunction and neuroinflammation after traumatic brain injury. Neurobiol. Dis. 2020, 145, 105080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murúa, S.R.; Farez, M.F.; Quintana, F.J. The Immune Response in Multiple Sclerosis. Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 2022, 17, 121–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneka, M.T.; Carson, M.J.; El Khoury, J.; Landreth, G.E.; Brosseron, F.; Feinstein, D.L.; et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2015, 14, 388–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambertsen, K.L.; Finsen, B.; Clausen, B.H. Post-stroke inflammation-target or tool for therapy? Acta Neuropathol. 2019, 137, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, M.; Zhong, L.; Jin, X.; Cui, R.; Yang, W.; Gao, S.; Lv, J.; Li, B.; Liu, T. Effect of Inflammation on the Process of Stroke Rehabilitation and Poststroke Depression. Front. Psychiatry 2019, 10, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rha, J.H.; Saver, J.L. The impact of recanalization on ischemic stroke outcome: a meta-analysis. Stroke 2007, 38, 967–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Wang, S.; Pigott, V.M.; Jiang, T.; Foley, L.M.; Mishra, A.; et al. Selective role of Na(+) /H(+) exchanger in Cx3cr1(+) microglial activation, white matter demyelination, and post-stroke function recovery. Glia Glia, 66, 2279–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breckwoldt, M.O.; Chen, J.W.; Stangenberg, L.; Aikawa, E.; Rodriguez, E.; Qiu, S.; Moskowitz, M.A.; Weissleder, R. Tracking the inflammatory response in stroke in vivo by sensing the enzyme myeloperoxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2008, 105, 18584–18589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Fan, W.-H.; Liu, Q.; Shang, K.; Murugan, M.; Wu, L.-J.; Wang, W.; Tian, D.-S. Fingolimod Protects Against Ischemic White Matter Damage by Modulating Microglia Toward M2 Polarization via STAT3 Pathway. Stroke 2017, 48, 3336–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-J.J.; Friedman, B.A.; Ha, C.; Durinck, S.; Liu, J.; Rubenstein, J.L.; Seshagiri, S.; Modrusan, Z. Single-cell RNA sequencing identifies distinct mouse medial ganglionic eminence cell types. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, srep45656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lampron, A.; Larochelle, A.; Laflamme, N.; Préfontaine, P.; Plante, M.-M.; Sánchez, M.G.; Yong, V.W.; Stys, P.K.; Tremblay, M.; Rivest, S. Inefficient clearance of myelin debris by microglia impairs remyelinating processes. J. Exp. Med. 2015, 212, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miron, V.E.; Boyd, A.; Zhao, J.-W.; Yuen, T.J.; Ruckh, J.M.; Shadrach, J.L.; van Wijngaarden, P.; Wagers, A.J.; Williams, A.; Franklin, R.J.M.; et al. M2 microglia and macrophages drive oligodendrocyte differentiation during CNS remyelination. Nat. Neurosci. 2013, 16, 1211–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruckh, J.M.; Zhao, J.-W.; Shadrach, J.L.; van Wijngaarden, P.; Rao, T.N.; Wagers, A.J.; Franklin, R.J. Rejuvenation of Regeneration in the Aging Central Nervous System. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 10, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Nicola, D.; Perry, V.H. Microglial dynamics and role in the healthy and diseased brain: a paradigm of functional plasticity. Neuroscientist 2015, 21, 169–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Pu, H.; Ye, Q.; Jiang, M.; Chen, J.; Zhao, J.; Li, S.; Liu, Y.; Hu, X.; Rocha, M.; et al. Transforming Growth Factor Beta-Activated Kinase 1–Dependent Microglial and Macrophage Responses Aggravate Long-Term Outcomes After Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 2020, 51, 975–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lam, T.I.; Brennan-Minnella, A.M.; Won, S.J.; Shen, Y.; Hefner, C.; Shi, Y.; Sun, D.; Swanson, R.A. Intracellular pH reduction prevents excitotoxic and ischemic neuronal death by inhibiting NADPH oxidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2013, 110, E4362–E4368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begum, G; Song, S; Wang, S; Zhao, H; MIH, B.; Li, E; et al. Selective knockout of astrocytic Na(+) /H(+) exchanger isoform 1 reduces astrogliosis, BBB damage, infarction, and improves neurological function after ischemic stroke. Glia 2018, 66, 66–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Kintner, D.B.; Chanana, V.; Algharabli, J.; Chen, X.; Gao, Y.; et al. Activation of microglia depends on Na+/H+ exchange-mediated H+ homeostasis. J Neurosci. 2010, 30, 15210–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Chanana, V.; Watters, J.J.; Ferrazzano, P.; Sun, D. Role of sodium/hydrogen exchanger isoform 1 in microglial activation and proinflammatory responses in ischemic brains. J. Neurochem. 2011, 119, 124–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, S.; Yu, L.; Hasan, N.; Paruchuri, S.S.; Mullett, S.J.; Sullivan, M.L.G.; Fiesler, V.M.; Young, C.B.; Stolz, D.B.; Wendell, S.G.; et al. Elevated microglial oxidative phosphorylation and phagocytosis stimulate post-stroke brain remodeling and cognitive function recovery in mice. Commun. Biol. 2022, 5, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Previtali, S.C.; Gidaro, T.; Diaz-Manera, J.; Zambon, A.; Carnesecchi, S.; Roux-Lombard, P.; et al. Rimeporide as a fi rst- in-class NHE-1 inhibitor: Results of a phase Ib trial in young patients with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Pharmacol Res. 2020, 159, 104999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraeuter, A.-K.; Guest, P.C.; Sarnyai, Z. The Y-Maze for Assessment of Spatial Working and Reference Memory in Mice. Methods Mol Biol. 2019, 1916, 105–11. [Google Scholar]

- Leng, T.; Shi, Y.; Xiong, Z.G.; Sun, D. Proton-sensitive cation channels and ion exchangers in ischemic brain injury: new therapeutic targets for stroke? Prog Neurobiol. 2014, 115, 189–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Shen, Q.; Xu, P.; Luo, J.J.; Tang, Y. Phagocytosis of Microglia in the Central Nervous System Diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 2014, 49, 1422–1434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Zuo, Y.-X.; Jiang, R.-T. Astrocyte morphology: Diversity, plasticity, and role in neurological diseases. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2019, 25, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powers, W.J.; Rabinstein, A.A.; Ackerson, T.; Adeoye, O.M.; Bambakidis, N.C.; Becker, K.; Biller, J.; Brown, M.; Demaerschalk, B.M.; Hoh, B.; et al. Guidelines for the Early Management of Patients With Acute Ischemic Stroke: 2019 Update to the 2018 Guidelines for the Early Management of Acute Ischemic Stroke: A Guideline for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 2019, 50, e344–e418, Correction in Stroke 2019, 50, e440-e441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Théroux, P.; Chaitman, B.; Danchin, N.; Erhardt, L.; Meinertz, T.; Schroeder, J.; Tognoni, G.; White, H.; Willerson, J.; Jessel, A. Inhibition of the Sodium-Hydrogen Exchanger With Cariporide to Prevent Myocardial Infarction in High-Risk Ischemic Situations. Main results of the GUARDIAN trial. Guard during ischemia against necrosis (GUARDIAN) Investigators. Circulation 2000, 102, 3032–3038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mentzer, R.M., Jr.; Bartels, C.; Bolli, R.; Boyce, S.; Buckberg, G.D.; Chaitman, B.; Haverich, A.; Knight, J.; Menasché, P.; Myers, M.L.; et al. Sodium-Hydrogen Exchange Inhibition by Cariporide to Reduce the Risk of Ischemic Cardiac Events in Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting: Results of the EXPEDITION Study. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 2008, 85, 1261–1270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, H.B.; Gao, X.; Nepomuceno, R.; Hu, S.; Sun, D. Na(+)/H(+) exchanger in the regulation of platelet activation and paradoxical effects of cariporide. Exp Neurol. 2015, 272, 11–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Corvera, J.S.; Zhao, Z.Q.; Schmarkey, L.S.; Katzmark, S.L.; Budde, J.M.; Morris, C.D.; et al. Optimal dose and mode of delivery of Na+/H+ exchange-1 inhibitor are critical for reducing postsurgical ischemia-reperfusion injury. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003, 76, 1614–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, C.X.; Gan, X.T.; Beier, N.; Scholz, W.; Karmazyn, M. Inhibition and reversal of myocardial infarction-induced hypertrophy and heart failure by NHE-1 inhibition. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2004, 286, H381–H387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingma, J.G. Inhibition of Na(+)/H(+) Exchanger With EMD 87580 does not Confer Greater Cardioprotection Beyond Preconditioning on Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Normal Dogs. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2018, 23, 254–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Luo, J.; Chen, H.; Kintner, D.B.; Shull, G.E.; Sun, D. Decreased neuronal death in Na+/H+ exchanger isoform 1-null mice after in vitro and in vivo ischemia. J Neurosci. 2005, 25, 11256–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadareishvili, Z.; Kelley, D.; Luby, M.; Simpkins, A.N.; Leigh, R.; Lynch, J.K.; Hsia, A.W.; Benson, R.T.; Johnson, K.R.; Hallenbeck, J.M.; et al. Molecular signature of penumbra in acute ischemic stroke: a pilot transcriptomics study. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2019, 6, 817–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Etherton, M.R.; Wu, O.; Giese, A.-K.; Lauer, A.; Boulouis, G.; Mills, B.; Cloonan, L.; Donahue, K.L.; Copen, W.; Schaefer, P.; et al. White Matter Integrity and Early Outcomes After Acute Ischemic Stroke. Transl. Stroke Res. 2019, 10, 630–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, R.J.; Ritzel, R.M.; Barrett, J.P.; Doran, S.J.; Jiao, Y.; Leach, J.B.; Szeto, G.L.; Wu, J.; Stoica, B.A.; Faden, A.I.; et al. Microglial Depletion with CSF1R Inhibitor During Chronic Phase of Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury Reduces Neurodegeneration and Neurological Deficits. J. Neurosci. 2020, 40, 2960–2974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantinelli, J.; Arbeláez, L.F.G.; Mosca, S.M. Cardioprotective efficacy against reperfusion injury of EMD-87580: Comparison to ischemic postconditioning. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 737, 125–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garciarena, C.D.; Caldiz, C.I.; Correa, M.V.; Schinella, G.R.; Mosca, S.M.; Chiappe de Cingolani, G.E.; et al. Na+/H+ exchanger-1 inhibitors decrease myocardial superoxide production via direct mitochondrial action. J Appl Physiol 2008, 105, 1706–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javadov, S.; Huang, C.; Kirshenbaum, L.; Karmazyn, M. NHE-1 inhibition improves impaired mitochondrial permeability transition and respiratory function during postinfarction remodelling in the rat. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2005, 38, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Javadov, S.; Purdham, D.M.; Zeidan, A.; Karmazyn, M. NHE-1 inhibition improves cardiac mitochondrial function through regulation of mitochondrial biogenesis during postinfarction remodeling. Am. J. Physiol. Circ. Physiol. 2006, 291, H1722–H1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Y.; Kim, D.; Caldwell, M.; Sun, D. The role of Na(+)/h (+) exchanger isoform 1 in inflammatory responses: maintaining H(+) homeostasis of immune cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2013, 961, 411–18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ghaleh, B.; Barthélemy, I.; Wojcik, J.; Sambin, L.; Bizé, A.; Hittinger, L.; Tran, T.D.; Thomé, F.P.; Blot, S.; Su, J.B. Protective effects of rimeporide on left ventricular function in golden retriever muscular dystrophy dogs. Int. J. Cardiol. 2020, 312, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bkaily, G.; Chahine, M.; Al-Khoury., J.; Avedanian, L.; Beier, N.; Scholz, W.; et al. Na(+)-H(+) exchanger inhibitor prevents early death in hereditary cardiomyopathy. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2015, 93, 923–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, K.; Sloan, S.A.; Bennett, M.L.; Scholze, A.R.; O’Keeffe, S.; et al. An RNA-sequencing transcriptome and splicing database of glia, neurons, and vascular cells of the cerebral cortex. J Neurosci. 2014, 34, 11929–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boussouf, A.; Gaillard, S. Intracellular pH changes during oligodendrocyte differentiation in primary culture. J Neurosci Res. 2000, 59, 731–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ro, H.-A.; Carson, J.H. pH Microdomains in Oligodendrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 37115–37123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swanson, R.A.; Morton, M.T.; Tsao-Wu, G.; Savalos, R.A.; Davidson, C.; Sharp, F.R. A Semiautomated Method for Measuring Brain Infarct Volume. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1990, 10, 290–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.; Bhuiyan, M.I.H.; Jiang, T.; Song, S.; Shankar, S.; Taheri, T.; et al. A Novel Na(+)-K(+)-Cl(-) Cotransporter 1 Inhibitor STS66* Reduces Brain Damage in Mice After Ischemic Stroke. Stroke 2019, 50, 1021–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Administration of NHE1 inhibitor HOE642 at 24 h post-stroke improved motor-sensory and cognitive functions in C57/BL6J mice.A. Experimental protocol. B. Neurological scores of mice at 1-7 d post-stroke. C. Rotarod accelerating test, foot-fault test, adhesive contact test and adhesive removal test of the same cohort of mice in B. D-E. Y-maze spontaneous alternation test and novel object recognition test at 28-30 d post-stroke in the same cohort of mice in B. N = 7-8. Data are mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Figure 1.

Administration of NHE1 inhibitor HOE642 at 24 h post-stroke improved motor-sensory and cognitive functions in C57/BL6J mice.A. Experimental protocol. B. Neurological scores of mice at 1-7 d post-stroke. C. Rotarod accelerating test, foot-fault test, adhesive contact test and adhesive removal test of the same cohort of mice in B. D-E. Y-maze spontaneous alternation test and novel object recognition test at 28-30 d post-stroke in the same cohort of mice in B. N = 7-8. Data are mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Figure 2.

No changes in ischemic infarct or neuronal death in C57/BL6J mice treated with HOE642 A. Representative images of TTC stained brain sections of the Veh- and HOE-treated mice at 3 d post-stroke. Arrows: infarcted tissues. B. Infarct volume and brain swelling analysis of the TTC stained brain sections. N = 3-4. Data are mean ± SD. C. Representative images of MAP2 and NeuN immunostaining in the contralateral (CL), ipsilateral (IL) perilesion area, and ischemic core of the Veh- and HOE-treated mice at 3 d post-stroke. Arrowheads: preserved NeuN+ neurons. D. Quantitative analysis of MAP2 intensity or NeuN+ cell counts in the Veh- and HOE-treated mice at 3 d post-stroke. N= 6-7. Data are mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

Figure 2.

No changes in ischemic infarct or neuronal death in C57/BL6J mice treated with HOE642 A. Representative images of TTC stained brain sections of the Veh- and HOE-treated mice at 3 d post-stroke. Arrows: infarcted tissues. B. Infarct volume and brain swelling analysis of the TTC stained brain sections. N = 3-4. Data are mean ± SD. C. Representative images of MAP2 and NeuN immunostaining in the contralateral (CL), ipsilateral (IL) perilesion area, and ischemic core of the Veh- and HOE-treated mice at 3 d post-stroke. Arrowheads: preserved NeuN+ neurons. D. Quantitative analysis of MAP2 intensity or NeuN+ cell counts in the Veh- and HOE-treated mice at 3 d post-stroke. N= 6-7. Data are mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

Figure 3.

Post-stroke administration of HOE642 enhanced white matter myelination and oligodendrogenesis. A. Representative corpus collosum (CC) images stained with MBP (4x) and quantitative analysis of CC thickness in the Veh- or HOE-treated brains at 3 d post-stroke. B. Representative confocal CC images (40x) and quantitative analysis of MBP intensity and APC+ counts in the Veh- and HOE-treated brains at 3 d post-stroke. Arrowheads: APC+ cells. N = 5-6. C. Representative images and quantitative analysis of NG2+Olig2+, Ki67+Olig2+, and Caspase3+Olig2+ cells in the CL and IL hemispheres of CC at 3 d post-stroke. Arrows: double positive cells. N = 6-7. Data are mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

Figure 3.

Post-stroke administration of HOE642 enhanced white matter myelination and oligodendrogenesis. A. Representative corpus collosum (CC) images stained with MBP (4x) and quantitative analysis of CC thickness in the Veh- or HOE-treated brains at 3 d post-stroke. B. Representative confocal CC images (40x) and quantitative analysis of MBP intensity and APC+ counts in the Veh- and HOE-treated brains at 3 d post-stroke. Arrowheads: APC+ cells. N = 5-6. C. Representative images and quantitative analysis of NG2+Olig2+, Ki67+Olig2+, and Caspase3+Olig2+ cells in the CL and IL hemispheres of CC at 3 d post-stroke. Arrows: double positive cells. N = 6-7. Data are mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

Figure 4.

Efficacy of post-stroke delivery of a novel NHE1 inhibitor Rimeporide A. Experimental protocol. B-C. TTC staining and infarct volume and brain swelling analysis of the Veh- and RIM-treated mice at 3 d post-stroke. N = 3. D-E. Neurological scoring and rotarod accelerating test for motor-sensory functions in Veh or RIM-treated mice from 1-14 d post-stroke. N = 9 for Veh, N = 10 for RIM. F-H. Open field test, Y-maze spontaneous alternation test and novel spatial recognition test in the same cohort of mice in D-E, at 30-40 d post-stroke. Data are mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Figure 4.

Efficacy of post-stroke delivery of a novel NHE1 inhibitor Rimeporide A. Experimental protocol. B-C. TTC staining and infarct volume and brain swelling analysis of the Veh- and RIM-treated mice at 3 d post-stroke. N = 3. D-E. Neurological scoring and rotarod accelerating test for motor-sensory functions in Veh or RIM-treated mice from 1-14 d post-stroke. N = 9 for Veh, N = 10 for RIM. F-H. Open field test, Y-maze spontaneous alternation test and novel spatial recognition test in the same cohort of mice in D-E, at 30-40 d post-stroke. Data are mean ± SEM. * p < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Figure 5.

Post-stroke delivery of Rimeporide improved white matter myelination after stroke. A. Representative images and quantitative analysis of MBP intensity and APC+ counts in the Veh- and RIM-treated brains at 3 d post-stroke. Arrows: APC+ cells. N = 3. B. Representative images and quantitative analysis of NG2+Olig2+, Caspase3+Olig2+, and H3K9me3+Olig2+ cells in the CL and IL hemispheres of CC at 3 d post-stroke. Arrows: double positive cells. N = 3. Data are mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.3.4. Post-stroke administration of Rimeporide enhances white matter myelination with increased oligodendrogenesis and reduced apoptosis.

Figure 5.

Post-stroke delivery of Rimeporide improved white matter myelination after stroke. A. Representative images and quantitative analysis of MBP intensity and APC+ counts in the Veh- and RIM-treated brains at 3 d post-stroke. Arrows: APC+ cells. N = 3. B. Representative images and quantitative analysis of NG2+Olig2+, Caspase3+Olig2+, and H3K9me3+Olig2+ cells in the CL and IL hemispheres of CC at 3 d post-stroke. Arrows: double positive cells. N = 3. Data are mean ± SEM. ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.3.4. Post-stroke administration of Rimeporide enhances white matter myelination with increased oligodendrogenesis and reduced apoptosis.

Figure 6.

Post-stroke administration of HOE642 or Rimeporide reduced microglial inflammation without affecting astrogliosis A. Representative images and quantitative analysis of GFAP+ and IBA1+ cells in the CL and IL cortex of Veh- and HOE-treated mice at 3 d post-stroke. B. Representative gating strategy for CD11b+CD45+ microglia/macrophages. C. Quantitative analysis of inflammatory profiling markers within the parent CD11b+CD45+ microglia/macrophages in the Veh- and HOE-treated mice at 3 d post-stroke. D. Representative images and quantitative analysis of GFAP+ and IBA1+ cells in the CL and IL cortex of the Veh- and RIM-treated mice at 3 d post-stroke. E. Quantitative analysis of inflammatory profiling markers within the parent CD11b+CD45+ microglia/macrophages of the Veh- and RIM-treated mice at 3 d post-stroke. * p < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

Figure 6.

Post-stroke administration of HOE642 or Rimeporide reduced microglial inflammation without affecting astrogliosis A. Representative images and quantitative analysis of GFAP+ and IBA1+ cells in the CL and IL cortex of Veh- and HOE-treated mice at 3 d post-stroke. B. Representative gating strategy for CD11b+CD45+ microglia/macrophages. C. Quantitative analysis of inflammatory profiling markers within the parent CD11b+CD45+ microglia/macrophages in the Veh- and HOE-treated mice at 3 d post-stroke. D. Representative images and quantitative analysis of GFAP+ and IBA1+ cells in the CL and IL cortex of the Veh- and RIM-treated mice at 3 d post-stroke. E. Quantitative analysis of inflammatory profiling markers within the parent CD11b+CD45+ microglia/macrophages of the Veh- and RIM-treated mice at 3 d post-stroke. * p < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** p < 0.001, **** p < 0.0001.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).