1. Introduction

There is an increasingly important role by social entrepreneurs to achieve and balance both social and economic outcomes for environmental and business sustainability in a circular economy. The 21st century brought forward advances and developments in virtually every field, but it also highlighted socio-environmental and economic issues that affect the future. In response to such issues, governmental, non-governmental organizations, businesses, universities and individuals have adopted new measures and initiatives. However, it is no longer enough to rely solely on the government and corporations to respond to all the needs of the people and the planet, so there has been an increase in the number of social startups and enterprises, supported by various stakeholders, being established with the mission to bring solutions for socio-environmental issues (McMullen & Bergman, 2017; Santos, 2012). With innovative Business Model (BM), democratization of technologies and information, there has been a fast growth of this phenomenon which led to further traction from both academics and practitioners alike, growing the number of literature and case studies around the world (Zahra et al., 2009). Given the vast variety of BMs and social missions incorporated in Social Entrepreneurship (SE), various definitions exist for the concept of SE, further divided into different focus areas and levels, ranging from micro (individuals), to meso (organizations and processes), and macro (socio-economic and political contexts), impacted by the trends and times at which they appear (Canestrino et al., 2020), and with a variety of stakeholders playing different roles. Adding onto this vagueness is how BMs impact the flow of SE when it transitions from its founding to growing and scaling (of the organization and of the social impact).

Social entrepreneurs, with their missions grounded with a social purpose, aim to create social value (Lepoutre, 2011) by delivering Social Impact (SI), which is defined as significant or positive changes that solve or address social issues (Zahra et al., 2009). They do so with BMs that diverge from traditional ones as it is driven by mission. And in aiming to deliver the highest social impact possible, social entrepreneurs face numerous challenges: lack of funding, support and skills, balancing business sustainability and mission, and ultimately, the ability to scale social impact. To this extent, the literature shows that it is more pertinent to scale social impact in an exponential manner without focusing on scaling the organization by relying on the ecosystem and systemic actors (Han and Shah, 2020). In parallel, a growing body of literature on BM is also concerned with the systemic perspective, bringing consensus to the importance of incorporating other actors’ roles.

Scaling Social Impact (SSI), without scaling the organization, would require different approaches to the BM in order to maximize the efficiency, but there is a lack of understanding how these two strands of work might be synthesized to offer insights into how BM’s role in SSI. Hence, this paper aims to advance efforts by drawing on the literature of SE, BM, and SSI, to examine the cause-effect relationships of BMs and SSI, to examine how BMs and its transitions are used to scale social impact in the context of SE.

This paper will have a unique position to build both theoretical and practical contributions, for academics and social entrepreneurs alike, and leverage the case study research method to investigate the SE phenomenon within its real-world context. A single case study, “mymizu”, a Japanese social startup that combats the issue of plastic waste, will be applied to analyze these interrelations in the context of the circular economy in Japan, a highly significant area given current environmental circumstances and socio-economic revitalization. Thus, this study will also open up new venues to be considered in innovating BMs for SSI by social entrepreneurs. For this purpose, we will establish the following as the research question: what is the role of the BM in SSI and how does it result in an exponential scaling?

In order to answer this, this paper will be structured as follows: section 2 will provide a literature review of SE, BM, and SSI, with a particular emphasis on a systemic perspective to introduce the activity system approach for BMs (Zott and Amit, 2010) and the ecosystem of SSI (Han and Shah, 2020). These two papers are considered to be pioneering with their introduction and highlighting of system elements to research strands where much of the efforts had been into organizational factors and growth.

Section 3 will detail the research methodology and introduce the singular case study of “mymizu”, the Japanese social startup which has been internally acclaimed for its social mission.

Section 4 will present the results from the qualitative analysis through the case study and we will discuss their implications and contributions in section 5, updating the current model of the ecosystem of SSI with a new factor. The conclusion will then provide remarks on the limitations of this paper and pave way for further research to be conducted.

2. Literature Review

In this section, we will review the literature on core aspects of this paper: social entrepreneurship, business model and scaling social impact, highlighting important insights relevant to this study. In particular, we will explore the more recent studies that have introduced systemic perspectives to call attention to the importance of collaboration and partnerships across various sectors and entities (Zott and Amit, 2010; Kovanen, 2021; Han and Shah, 2020; Ciulli et al., 2022).

2.1. Social Entrepreneurship

Social entrepreneurship has become an increasingly important phenomenon in the 21st century, gaining traction amongst both researchers and practitioners, for its contribution to environmental and socio-economic justice, development and prosperity, with social entrepreneurs filling in the void unfilled by other entities, viewing social issues as an entrepreneurial opportunity (Beckmann, 2011). Nevertheless, given the vast contexts of “social” (which encompasses a much larger area) issues, numerous and ambiguous definitions exist (Dacin, Dacin, & Matear, 2010). Amongst existing definitions, a popular one is by Zahra et al. (2009), who defines SE as “The activities and processes undertaken to discover, define, and exploit opportunities in order to enhance social wealth by creating new ventures or managing existing organizations in an innovative manner.” Amongst recurring themes of SE in the literature, we find “social wealth/value” as the outcome of their mission (Dees et al., 2001) and “innovation” to define the approach to activities and processes. Indeed, CASE (2006) and Dees et al. (2004) have mentioned that the goal of social enterprises is mostly to maximize their social impact, through an approach that includes the scaling of their BMs, with innovation being a key influence (Dees, 1998) for delivering this social impact. With such an important mission in their field of operation, social entrepreneurs are considered as change agents (Dees et al. 2001). The European Commission’s definition also emphasizes the concept of social impact, by defining a social enterprise as “an operator in the social economy whose main objective is to have a social impact rather than make a profit for their owners or shareholders”. Hence, in the context of this paper, we will define SE with a focus on the innovative activities and processes undertaken to deliver social impact.

More research has emerged recently in this field to look into the benefits of social entrepreneurs working closely with other actors for their mission, in parallel to how social entrepreneurs are perceived to be driven by self-oriented motives rather than other-oriented motives (Ruskin et al. 2016). Kovanen (2021) highlights that community collaboration can enable social entrepreneurs to better balance their institutional and resource relations and to reach societal change, a major social impact sought after by entrepreneurs. However, the term community is loosely used, and the scope remains to be defined more precisely as collaboration can vary greatly depending on the size of the community. A collaborative SE is perceived to be successful when the process is carried out in a participatory manner. Social startups, with the importance of their social missions, are also capable of attracting volunteers through a sense of purpose, enabling them to be part of social change (Zeyen et al., 2014). This then raises the question as to how the community can be involved.

To this extent, it has been shown that collective action frameworks can serve as strategies to drive systems-change through innovative ways and motivating supporters to action (Teasdale et al., 2022). These developments, when seen through the stakeholder theory’s lens, allow us to confirm the relevance of society (encompassing communities and individuals) as a key stakeholder in SE that enhances the delivery of social impact. But the main question remains as to how such stakeholders fit into the BMs of SE. With social entrepreneurs making use of the entire spectrum of legal forms, a vast variety of BMs are deployed to their social mission (Dees & Anderson, 2006), thus necessitating a deeper understanding of BMs as used by social entrepreneurs. Furthermore, various scholars have demonstrated that managers (social entrepreneurs are also managers within their ventures) interested in social and environmental value creation are using the BM concept more than ever (Massa et al. 2017).

2.2. Business Model

Although we have a growing body of literature on BMs with its rising popularity, its definitions remain various (partly impacted by the organizational goals, such as social impact, profitability, growth, etc.) with both researchers and practitioners developing their studies according to their purpose and phenomena of interest (such as SE and sustainability, which are popular in recent research developments), thus being unable to use a single language to compare its frameworks (Zott et al., 2011; Massa et al., 2017). Furthermore, research on BMs has typically focused on the organization itself and its internal systems, and how it creates, captures and delivers value to its customers (Attanasio et al., 2021). However this last decade has seen a growing consensus on how BMs represent “a system of interdependent activities that transcends the focal firm and spans its boundaries’’ (Zott and Amit, 2010). This has brought forward new research strands into holistic and systemic perspectives of the BM concept, going beyond the organization’s internal view and boundaries to outline how it interacts with its surrounding external environment (Berglund and Sandstrom, 2013), which becomes the ecosystem (Demil et al., 2018) and represents a fundamental characteristic of BMs for sustainability (Attanasio et al., 2021). This direction is crucial in this literature as social entrepreneurs leverage collaboration, thus requiring a better understanding of what it means to BM’s design and structure.

In Zott and Amit (2010)’s definition of BM through an activity system perspective, the set of interdependent activities, while conducted by the organization itself or its partners, can go beyond its boundaries but will remain focused on the organization to enable it to create and retain a share of that value. As the activities may be also performed by its partners, this enables the organization to tap onto external resources and capabilities, evoking the idea of operating through an “open BM”. Building on this concept through the lens of open systems theory, Berglund and Sandstrom (2013) have established that organizations are influenced by their environment, depending on external actors for critical resources despite their unreliability due to being outside the organization’s control, which calls for better relationships between the organization and external actors through feedback loops for hedging the uncertainty. Bolton and Hannon (2016) have also taken on the same principle, demonstrating that the more successful BM entrepreneurs will don the role of system builders through partnerships in order to draw on resources. Such arguments are echoed by Kovanen (2021)’s findings on resource relations being important for social entrepreneurs, with collaboration being a key factor to balance them.

Indeed, resulting from the interdependent activities that transcend the organization’s boundaries, value creation is carried out through these exchange relationships among multiple players, showcasing that BM as a concept, focuses on cooperation, partnerships, collaboration and joint value creation (Zott et al. 2011). Moreover, for entrepreneurs thinking (or rethinking) of their BM design, Zott and Amit (2010) argue that a focus on activities is an important perspective and that the activity system perspective encourages them towards systemic and holistic thinking instead of narrow and isolated choices, which is beneficial in leveraging resources as previously mentioned.

While BM’s notion of value is often economic, in the context of sustainability, it takes a broader definition to encompass social and environmental aspects. Thus, the triple bottom line approach becomes a major concept for the BM, highlighting the need to consider stakeholder interests, such as the society and environment (Bocken et al., 2014) by communicating how it will create and deliver the value (Ludeke-Freund et al., 2016). Evans et al. (2017) have gone beyond to say that a sustainable value flow is necessary among multiple stakeholders, including the environment and society as primary stakeholders. Such sustainable value flow can be generated through either cooperation or collaboration between the different, business and non-business such as the government or society, actors, possibly paving way to scaling the (sustainable) BM itself (Ciulli et al., 2022; Boons and Lüdeke-Freund, 2013). This direction of these researches on BM in the context of sustainability also highlight the systemic perspective that was established by Zott and Amit (2010), and it builds further by going into the concepts of stakeholders, partnerships and collaborations, which are recurring themes in this paper’s case study.

However, scaling the BM (through collaboration as stated by Ciulli et al., (2022)) is equivalent to scaling the organization, and while that is one way of SSI, this paper focuses more on understanding how to scale social impact in an exponential manner without focusing on scaling the organization by relying on the ecosystem and systemic actors (Han and Shah, 2020). Indeed, from the literature review thus far, we see a gap in the understanding of BMs and their roles in SSI (without the BM itself having to be scaled). There is also a lack of case studies to showcase how organizations can innovate and design their BMs in various ways in order to work towards sustainability and deliver the highest social impact possible (Evans et al., 2017). Demil et al. (2018) also argues that both BMs and ecosystems are not static but rather co-evolve, which will lead us to ask how their transitions will influence the outcome: SSI in the context of SE.

2.3. Scaling Social Impact

As shown in the literature review of SE, social impact is regarded as the raison d’être of social enterprises and social entrepreneurs thrive to create social value for their mission, thus, SSI becomes a critical phenomenon for social enterprises (Alvord et al., 2004; Dees et al., 2004; Uvin, 1995), to the extent of being considered as “the single most important criterion to judge the performance of social enterprises’’ (Ebrahim and Rangan, 2014; Molecke and Pinkse, 2017). This has brought much interest, from both researchers and practitioners, into understanding the factors that enable or limit the potential of SSI (Bloom and Smith, 2010; Jenkins and Ishikawa, 2010; Sherman, 2006), and research shows that SSI is indeed one of the most challenging issues in social enterprises (Cannatelli 2017; Bradach 2003; Scheuerle and Schmitz 2016). Furthermore, with few social ventures experiencing scaling, it becomes one of the most important and least understood topics in SE research (Smith et al., 2016).

Current literature defines SSI as an “ongoing process of increasing the magnitude of both quantitative and qualitative positive changes in society by addressing pressing social problems at individual and/or systemic levels through one or more scaling paths” (Islam, 2020), which builds on the definition of social impact given by Zahra et al. (2009), with the term “scaling paths” highlighting that there are various approaches to SSI.

The widely common approach existing in the literature is grounded on scaling the BM, as part of scaling the organization itself (CASE, 2006b; Dees et al., 2004), with the growth of the sustainable BM also being conceptualized as scaling (Ciulli et al., 2022). Drawing from the literature of entrepreneurship, the term scaling is used for organizations that go through a “persistently rapid growth” (Reuber et al., 2021), with “scalability” as a related concept that refers to the capacity within BMs to increase sales towards a growing customer base (Täuscher and Abdelkafi, 2018), based on replicability, adaptability, and transferability of the operational model as key factors for scalability (Bradach, 2003; Winter & Szulanski, 2001). Dees (2008) define scalability as “increasing the impact a social-purpose organization produces to better match the magnitude of the social need or problem it seeks to address”. Therefore, this approach perceives SSI as organizational growth, with a focus on the organizational factors (internal capacities and capabilities) to make this a reality.

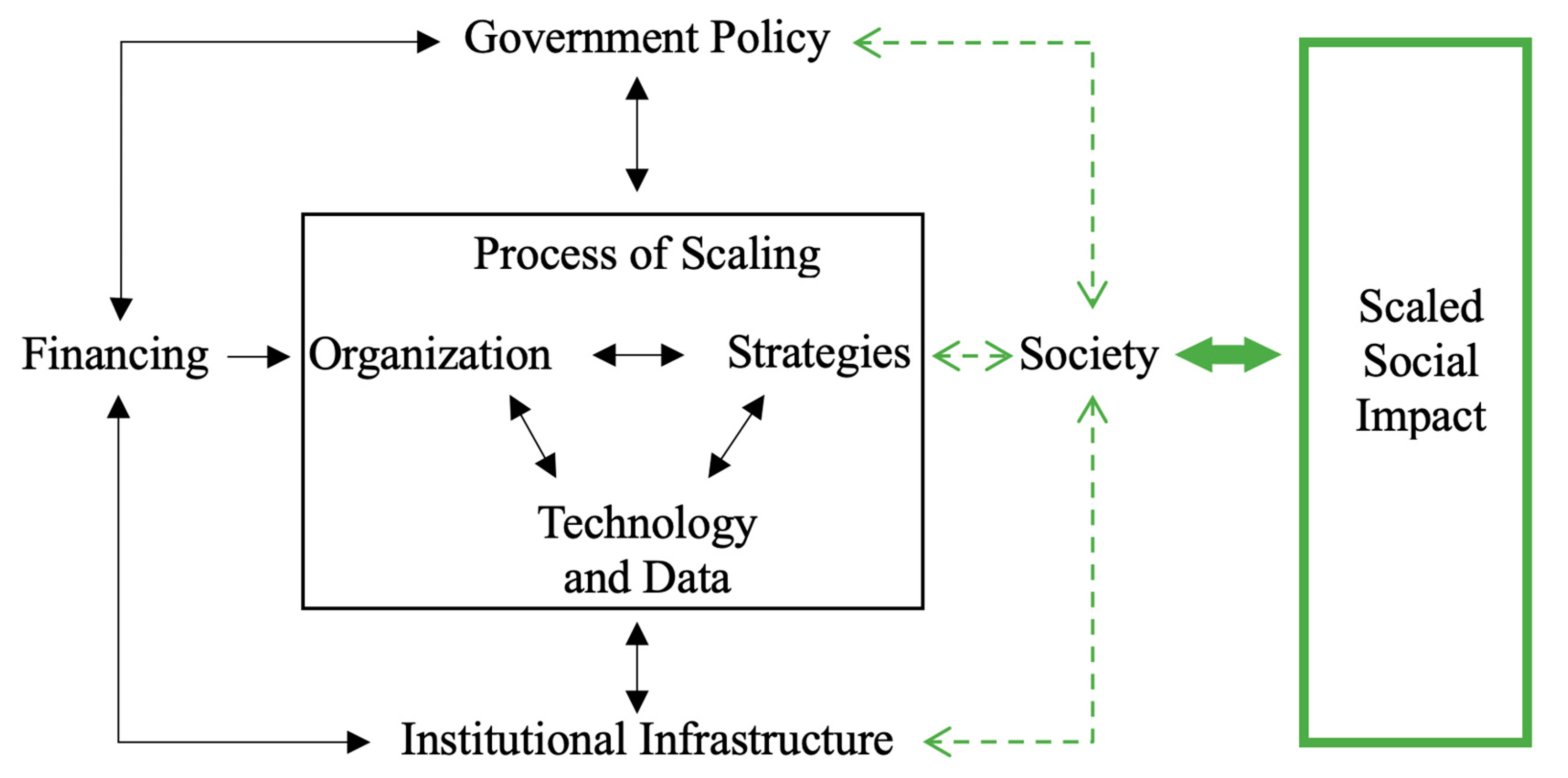

However, it is known that social entrepreneurs face numerous constraints in regards to their resources and capacities, which is why innovation is leveraged as a key factor for their mission to deliver social impact (Zahra et al. 2009). Given this reality, scaling the organization (BM) is a major challenge for social entrepreneurs. Hence, SSI is more about the effectiveness of addressing the social issue, transforming perspectives on issues and changing the status quo, rather than just increasing the impact through “persistently rapid growth” (Han and Shah 2020). To this extent, it is shown that systemic level factors are currently understudied in the current literature of SSI, with Han and Shah (2020) suggesting an ecosystem framework that discusses the roles of different stakeholders for business creation and operation that results in SSI. The holistic approach provides clarity to the different stakeholders’ roles and draws a parallel to the BM to be driven by multiple stakeholders, in contrast to the internal perspective shown by the previous approach. In their research, the authors show how the current literature does not distinguish SSI and scaling organization, and that it is of more interest and importance to figure how to scale social impact without maximizing organizational growth, highlighting Bradach (2010)’s words of “how to get 100X the results with 2X the organizations”, which supports the argument of constraints faced by social entrepreneurs and the need for effectiveness in addressing social issues. In their framework entitled “ecosystem of SSI” (see Figure), they incorporate interconnected key elements such as financing, government policy, institutional infrastructure, and process of scaling as a central element, with the latter embodying the organizations that use different strategies to scale social impact through technology and data. All of these 4 elements lead to social impact as the outcome of their interrelated activities, which makes up the whole ecosytem’s efforts towards social impact. The process of scaling itself can be considered to encompass the BM, with other elements representing part of Demil (2018)’s view of the ecosystem and Amit & Zott (2010)’s view of the BM as an activity system.

The literature review of this paper went through existing research on the concepts of SE, BM and SSI, and in all 3 areas, a recurring theme has become part of recent research strands: exploring a holistic and systemic perspective in order to include external stakeholders. This goes beyond a more traditional internal and organizational perspective as both researchers and practitioners are more commonly interested in how such an approach is more beneficial, highlighting its importance. As such, we now need more empirical evidence, so this paper will build further on this scholarship through the analysis of a singular case study, for which we will employ Han and Shah (2020)’s framework.

3. Research Methodology

This paper follows a qualitative research design due to its explanatory nature, in order to gain insights into the phenomenon of BM and SSI, to understand the underlying reasons of their interactions, and to develop on existing social theory. For the study, we employed a single holistic case approach based on a Japanese social entrepreneur with successful SSI track records in the context of a circular economy, collected primary and secondary data through direct interview with key personnel, fieldwork observation, document study, and social media, and applied content analysis method to formulate the findings and the resulting discussion points.

3.1. Case Study Method

We applied an in-depth single case study with longitudinal observation and research from the year 2019 till 2023. This methodology focuses on the process and scaling outcomes of the social impact of a Japanese social startup, mymizu, given its position in a niche environment. A case study approach investigates a contemporary phenomenon (the ‘case’) in depth and within its real-world context to understand what the case, how and why it works (Yin 2009). Mymizu is highly relevant as the single case study for the context of this paper because it is a unique and exemplary social startup, which leverages creativity, innovation, digital, and social factors for its social movement. As it operates within and in conjunction with an ecosystem in an established system, it echoes aspects found throughout the literature review in regards to being a social startup, its BM and its SSI.

Amongst papers reviewed in this study’s literature review, a qualitative research design was the most commonly employed approach through case studies (often multiple rather than single) for empirical evidence, along with scoping literature reviews. This can be explained by the fact that much of the literature was focused on providing definitions and building frameworks for SE, BM, and SSI, with less focus on interrelationships between these concepts, hence there was a broader application of this methodology. On the other hand, this current study is more in-depth in a niche topic as it focuses on the interactions between BM and SSI within the context of SE, hence the dive into a single case study enables us to explore with a deeper understanding.

3.2. Case Study of mymizu

This award-winning social startup was established in 2019 as a brand under the umbrella of Social Innovation Japan (SIJ), born from a crowdfunding campaign. It is the first water refill application platform in Japan that strives to drive social good through its social missions divided into 2 aspects: reduce the usage of PET bottles through water refill of reusable bottles and drive behavioral change in the society through a social movement for responsible consumption. The mymizu smartphone app is an open-source map with public water refill spots and mymizu refill spots (businesses, such as shops, cafes, restaurants, etc.) that allow people to refill their water bottle for free instead of purchasing PET bottled drinks for single use and throw. This is extremely pertinent to a society that is becoming increasingly aware of environmental issues but still currently lacking in engagement (Japan is the 2nd largest generator of plastic packaging waste per capita, with 30 billion plastic bags used every year and 25 billion PET bottles bought every year, as of 2022). Hence, its social mission to drive towards a circular economy is crucial as the environmental reality is that recycling is not the solution to such issues, making a holistic approach necessary for the elimination of waste and pollution, circulation of materials and products, and the regeneration of nature, in order to decouple the consumption of limited resources from economic activity. From late 2022, mymizu has also launched an open-source web platform (currently in beta version), created by the community for the community.

From the viewpoint of BM, mymizu is built around its social mission as its value proposition, which also defines its social impact: to raise awareness about environmental issues with PET bottles as a reference, and drive social change through behavior for responsible consumption.

Mymizu has 2 sets of “customers” (app users and organizations) and various revenue streams, users generating revenue only by purchasing mymizu branded items or taking part in the monthly supporter campaign. Refill partners do not generate revenues either as they represent more of a win-win situation by raising awareness of each other and driving foot traffic. The organizations (companies, universities, city governments, etc.) make up much of the current revenue model through partnerships and various streams: workshops, seminars, educational activities, talks, consulting for joint product development or communications, brand collaborations, and “mymizu challenges’’, which is a paid service consisting of a friendly internal competition, interactive workshops and lectures, with the aim to raise awareness and result in behavioral change towards responsible consumption amongst organizational members. As a social startup striving to be financially sustainable while pushing for its social mission, it also relies on NGO-like revenue streams: awards from social business competitions and programs, and grants and donations from individuals and organizations (corporates, governmental, etc.).

The marketing is built on creativity, innovation, digital technologies, and society in order to enable a movement with strong storytelling instead of a product or service. The network of refill partners (shops, cafes, restaurants, etc.) are major ambassadors of the mymizu brand as they raise awareness of mymizu through visuals and conversations. Mymizu’s partnerships and collaboration with renowned companies and cities such as Audi, Mitsubishi Chemical Cleansui Corporation, Meisui, LIXIL, Johnson & Johnson, Kobe City, etc., boost the growth of their brand image through awareness of mymizu and its social movement. Furthermore, mymizu also works closely with “mymizu ambassadors’’: athletes with strong connections to their communities, inspiring people and changes through their stories and actions.

3.3. Data Collection

For this case study, both primary and secondary data are collected from 4 sources, ranging from 2019 to 2023: direct interview with key personnel of mymizu, fieldwork observation, online publication, and social media. This variety enables triangulation of results from multiple approaches, with the comparison and combination of information providing a complete picture with more reliable and valid conclusions for this case study (Rogelberg 2004). The collected data is mostly qualitative in nature for understanding the social phenomena through in-depth exploration and analysis of people’s perspectives and narratives, but quantitative data from online publications will be also used to analyze the social startup’s performance and social impact.

The semi-structured interview conducted in 2022 with Mr. Robin Lewis, co-founder of mymizu, is to help define the areas to be explored in relation to the BM and SSI through a deeper understanding of mymizu, its social mission and its operations (Dearnley 2005). Given his leadership role in the organization, it will be used to explore his own perspectives for detailed insights into SE, mymizu’s current BM and forthcoming transitions. The fieldwork observations were carried out at online events held by mymizu at various points of time, from talks at universities to social entrepreneurship pitching & mentoring events, to observe Mr. Robin Lewis along with the key personnel of mymizu. These fieldwork observations were useful to gather descriptive analysis data throughout this 4-year period and gain new insights from the mymizu team in regards to its development, while also serving for triangulation purposes (Rogelberg 2004). Document studies were used extensively as a reliable source for secondary data, with both qualitative and quantitative data being collected from online publications from mymizu and newspapers, and social media, throughout the data collection period, with contents varying from press releases, reports, advertisements, event programs, and company websites. The qualitative data provide a means to track change and development throughout the 4 years, while the quantitative data from the document studies will be used to assess mymizu’s social impact, and components of its BM. Document studies are a highly applicable method for case studies as they serve as sources of empirical data, providing rich descriptions of a unique phenomenon, the organization, or an event, all within the context of study, as well as being a popular means of triangulation (Bowen 2009).

3.4. Data Analysis

To analyze the collected data, this paper employs the content analysis methodology. For this study, it is an appropriate approach and useful tool to discover and describe the organizational and social focus, to identify common themes, and to make inferences that can be corroborated with other data and the literature review (Stemler 2001). In particular, we will use the latent projective content analysis method to dive into the implied meanings, developing a deeper understanding of a particular phenomenon through a systemic process of interpretation, all in consideration of the context of the study and existing theory (Kleinheksel et al. 2020).

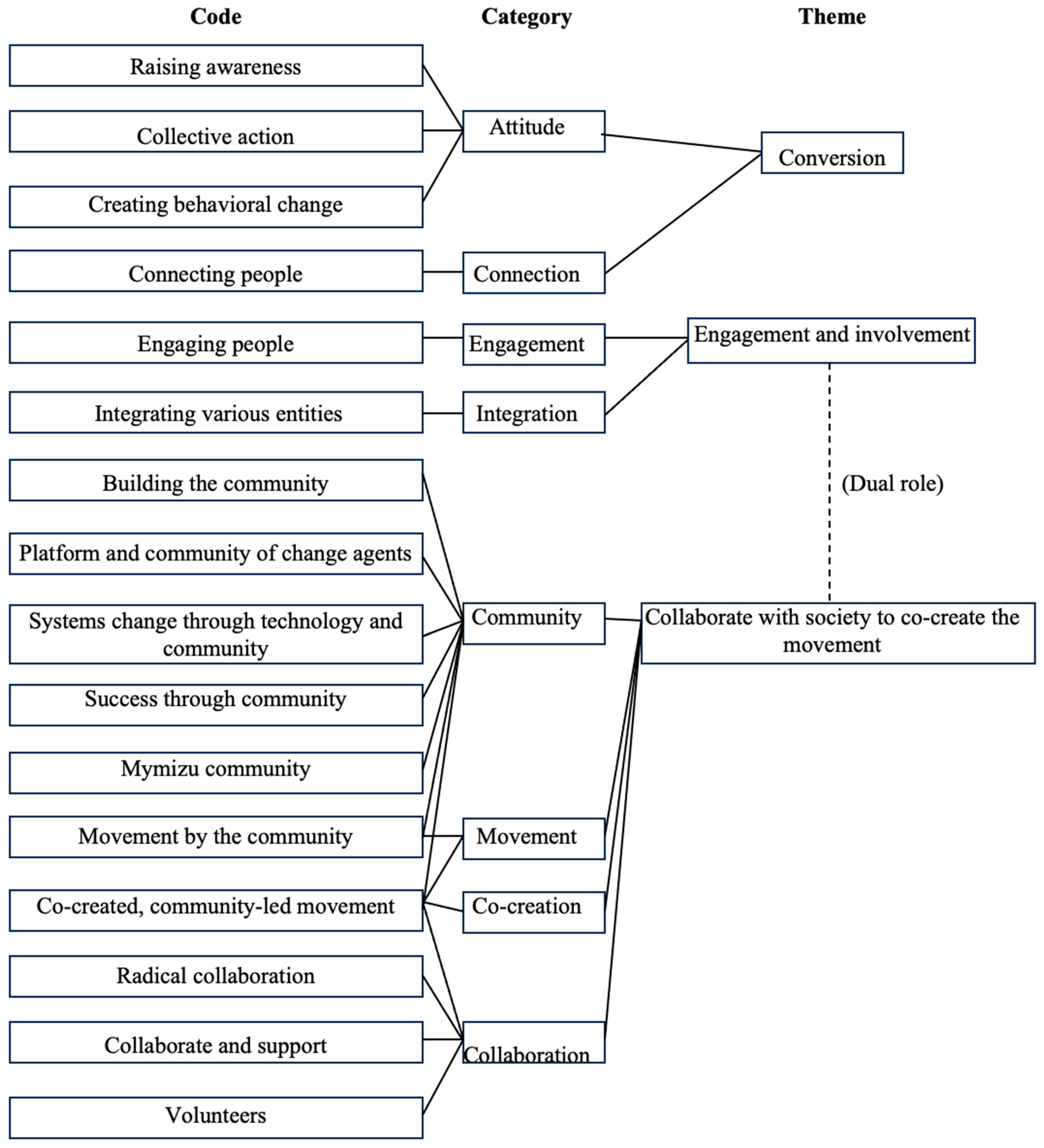

Figure 1 summarizes the latent projective content analysis conducted on qualitative data collected from the interview, fieldwork observations, online publications and social media. This table brings out the key themes repeating throughout this paper, which also provides the underlying reasons behind the numbers seen on

Figure 2.

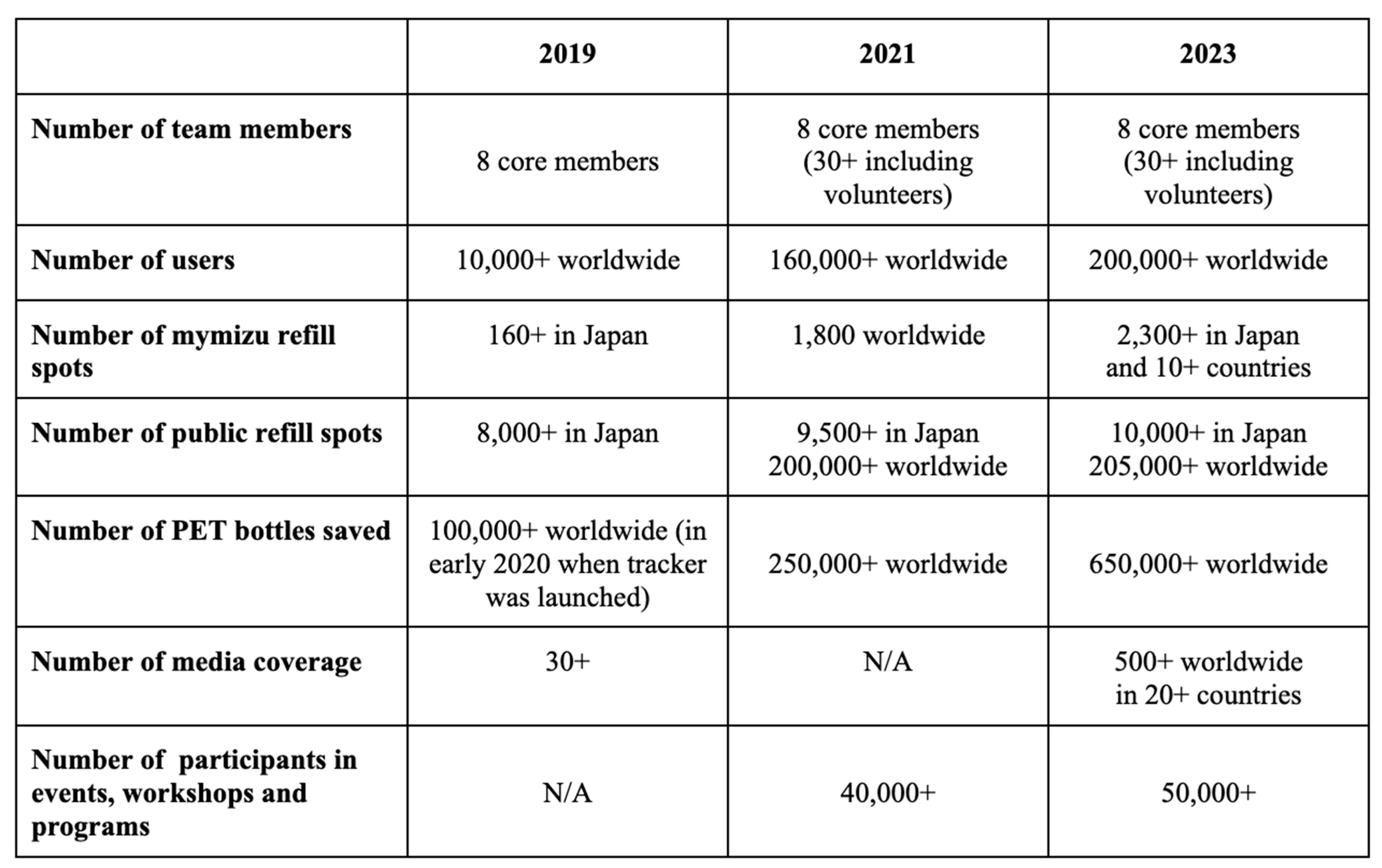

The figure below (

Figure 2) shows the outcomes of mymizu through quantitative data collected since its establishment in 2019, measured at 3 different points of time (2019–2021–2023), and in between each period, which highlights how mymizu’s social impact has been scaled through time.

4. Results

Based on the data collected and the analysis, the results show impact on the acquisition and conversion of new users through collaboration amongst different stakeholders on the initial phase of the BM, as well as the exponential scaling effect of the social impact due to the new dual role taken on by the society.

4.1. Converting awareness into users with behavioral change

The first finding is that mymizu has heavily collaborated with various stakeholders, creating a network of partners and collaborators that spreads the mymizu brand across sectors and demographics, going beyond the network of mymizu refill partners which are considered as their brand ambassadors. In turn, this results in raising the awareness of environmental issues and the circular economy, particularly in relation to PET bottles, and inculcating a behavioral change towards the practice and lifestyle of reduce, reuse, and recycle of plastic bottles, to design out this waste. Through this journey, they become able to take action as mymizu users with responsible consumption. As such, it can be inferred that mymizu’s goal of driving behavioral change at scale can be achieved by acquiring new users through collaborations at scale.

Since mymizu’s launch with its marketing built on creativity, innovation, digital technologies, and society, it has established partnerships and collaborations with numerous entities on various scopes: Audi, Cleansui, Meisei High School, IKEA, Kameoka City, Kobe City, LUSH, PADI, etc. This served to spread awareness internally amongst individuals within their organizations, work together on joint product development, communications and brand collaborations, and mymizu could also leverage these organizations’ brands and communications and spread awareness through them, in addition to the awareness generated through the mymizu refill partners. These partnerships and collaborations also extended to the individual level by working with mymizu ambassadors, athletes and actors, whose networks further spread the awareness.

This impact can be seen through the increase in the number of users between 2019 and 2023, scaling from more than 10,000 worldwide to more than 200,000 around the world, while the number of mymizu refill partners went from more than 160 in Japan to more than 2,300 in Japan (in all 47 prefectures whereas it began in Tokyo) and worldwide. These numbers show that awareness has led to behavioral change and collective action, as well as a further increase in the actions taken in order to spread awareness by being part of the movement. Users have an unanimous viewpoint: “I have been able to reduce so much plastic bottles [...] It is a really great app that is helping our planet” (mymizu 2021).

The number of PET bottles “saved” indicates the amount that has gone unused thanks to the equivalent amount of water being used to refill from public or refill spots. Between 2020 (when the tracker function was enabled) and 2023, we see an increase from more than 100,000 to more than 650,000 worldwide. This highlights the change in behavior, specifically by reducing the consumption of bottled water and by reusing reusable water bottles: “This is so useful because I don’t have to buy bottled water anymore! I used to buy from the vending machine even if I had a reusable water bottle with me because I would eventually run out of water. I didn’t know where to refill my bottle but this app solves that issue”(mymizu 2019).

4.2. Dual role for individuals: user and collaborator

The second finding is that said users can go beyond their roles and also become individual collaborators themselves, being driven by a social purpose, by engaging and getting involved to mymizu’s social mission. In fact, this began at the very early stages of mymizu through crowdfunding that enabled the establishment of mymizu, and throughout its existence, mymizu has worked in close collaboration with many of its users through 3 collaborative roles: (i) management volunteers, ii) monthly financial supporters and (iii) tech collaborators. Such a phenomenon ties back to mymizu’s mission and philosophy: “co-create an unstoppable movement for sustainability, one bottle at a time” (mymizu n.d.) and “The future is co-created. If we can connect millions of mission-driven people, we can kick start a movement and build a world where sustainable living is the norm. That’s why we’re building a platform and community of change agents.” (mymizu n.d.). As such, it results with collaborators participating in mymizu’s mission.

(i) Management volunteers

Management volunteers (on a pro bono basis) are essentially part of the mymizu team itself, involved in the human resources of the social startup, holding roles that encompasses marketing, communication, UX design, mymizu refill spots and partners network, product manager, etc. Working alongside mymizu’s core team, they supplement much of the needed human resources for mymizu’s scaling and SSI. As mentioned on the mymizu website, “due to high demand” to become a volunteer (mymizu n.d.), we can see how society’s members are ready to become part of the collaborating workforce.

ii) Monthly financial supporters

Monthly financial supporters are new roles that became possible through the Monthly Supporter Campaign launched in late 2022. This comes in addition to regular donations, with this monetary support being on a monthly basis to “contribute to covering towards essential costs” (mymizu n.d.) in order to continue their commitment of “keeping mymizu free-of-charge (for both users and refill partners)” (mymizu n.d.). As a monthly basis, this can create a stable source of revenue generation.

(iii) Tech collaborators

While mymizu had management volunteers in specific tech roles as well, the tech collaborators became part of a tech community when mymizu went open source for its new mymizu Web App (currently in open source beta). With “Technology + Community = Systems Change” as one of its core beliefs, mymizu launched this project through a hackathon in collaboration with Code Chrysalis (Japan’s only Silicon Valley-born coding bootcamp), bringing in the tech community from Tokyo and beyond, which enabled “radical collaboration through technology” in order to “change attitude towards sustainability at scale” (mymizu n.d.).

5. Discussion

In fact, both findings can be interpreted as a single outcome in a loop: partnerships and collaborations with organizations create more awareness, bring new users and create behavioral change, with users getting engaged and involved as individual collaborators. This creates a virtuous cycle, highlighting the importance of the system through partners and collaborators (both organizations and individuals). Based on these findings, we derive a major discussion point that contributes to the existing literature of BM, SSI and SE, building on an existing theoretical framework.

Han and Shah (2020) showed that the organization (the social startup in the context of this study) should rely on and leverage both organizational level and systemic level factors, and their interrelationships, to SSI instead of focusing on organizational growth as a means to SSI. These factors include the process of scaling (the organization, strategies, technology and data), financing, government policy and institutional infrastructure. While SSI’s definition includes society as the place where changes are to take place (Islam 2020), the current literature does not explore society (encompassing communities and individuals) as a potential partner and collaborator in the ecosystem. However, the mymizu case study showcases that society is integrative, and through involvement and engagement, it can be a collaborator under various forms, effectively becoming a “participatory stakeholder” (PS). This led us to propose a revised version of the ecosystem of SSI framework created by Han and Shah (2020) in

Figure 3, adding society as one of the factors that interacts with the other factors within this ecosystem, particularly with the organization through society’s roles in the BM, thus positively influencing the SSI.

However, in order to make society a PS, it needs to be involved and engaged within the organization’s BM and there is also a lack of understanding of this process. The mymizu case study has shown that society can be made a PS by engaging and involving key members of the society in specific roles inside the BM that positively impacts the organization while giving a purpose to these individuals: management volunteers, financial supporters and tech collaborators.

The understanding of PS can be supported by both the stakeholder and boundary spanner theories. The stakeholder theory explains that stakeholders have a great likelihood to provide important resources that can enable greater efficiency and innovation (Harrison et al. 2010), and that a firm’s network of stakeholders can be a source of sustainable competitive advantage (Bosse et al. 2009). The boundary spanner theory explains that personnel, who are boundary spanning, are “key representatives who engage in various activities on the boundary of an organization”, by facilitating both the exchange of information and organizational responses with the external environment. This leads to effective cooperation and problem solving, benefiting the organization and building favorable relationships (Huang and Luo 2016).

Thus, in mymizu’s case study, these individuals integrate the revenue streams (without being a customer) and the human resources of the organization’s BM, effectively transforming external factors into internal resources without being part of the organization. This process can be then defined as a regenerative model based on this feedback loop that influences the SSI, created between the BM and the society, drawing parallel to Demil et al. (2019)’s idea of business models and business ecosystem co-evolving through their interactions.

The idea of this being a regenerative model leads to the concept of regenerative business model (RBM), an increasingly popular research strand, which can be understood as having a net positive impact by making the organization’s handprint (positive impact created by its product or service) larger than its footprint (Norris, 2015; Norris et al., 2021). This ties back to “how to get 100X the results with 2X the organizations” (Bradach 2010), which is shown by mymizu’s results. Finally, with this social startup’s impact of reducing the consumption of plastic bottles and changing behavior at large, there is “planetary health and societal wellbeing to nature and society at large”, which becomes its value proposition (Dias, 2019; Gerhards and Greenwood, 2021; Hutchins and Storm, 2017; Slawinski et al., 2021; Wahl, 2016). Thus, mymizu can be inferred to have a RBM, or at least partly, pending further study.

6. Conclusion

The purpose of this explanatory study was to answer the following research question: what is the role of the BM in SSI and how does it result in an exponential scaling? The literature review along with the present case study showed that it was important to adopt a holistic approach and take into account systemic factors, with stakeholders representing an important role and opportunity in the development of SE, BM, and SSI. Thus, we conclude that the BM’s role in SSI is to strengthen the ecosystem by engaging and involving the society for exponential scaling outcomes, in the context of this paper. To further generalize, the organization should aim to engage the factor that defines its social impact in order to make it scalable (in mymizu’s case study, behavioral change of the society was the biggest purpose, making society the factor that defined its social impact).

However, this paper has some limitations and further research will be necessary to draw further generalization. First, the ecosystem explored in this study works because there is already a thoroughly established and robust ecosystem. Japan is a highly developed economy with strong institutional infrastructure, government policies, and financing, while mymizu is a social startup that truly incorporates creativity, innovation, digital, and social factors at its core. Second, this study is built on the assumption that the society is aware of environmental issues but is currently lacking in engagement to tackle such challenges, which is the context of Japan that is currently lagging behind other similarly developed countries in terms of environmental actions. In fact, these were the reasons why mymizu was chosen as a single case study for this research as it provides an ideal context to explore the interactions between BM and SSI through social entrepreneurship. Hence, in order to generalize this updated framework, further research should be conducted for empirical evidence of this phenomenon of society as a PS in the BM that leads to scaling social impact. Finally, given the importance of the RBM, further research is necessary to tie in SSI to RBM, and find further interrelationships that can enable a stronger SSI.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.K.F. and H.C.G.; methodology, K.K.F.; validation, H.C.G.; formal analysis K.K.F. and H.C.G.; investigation, K.K.F. ; resources, K.K.F. and H.C.G. ; data curation, K.K.F.; writing—original, K.K.F.; draft preparation, K.K.F. and H.C.G.; writing—review and editing, K.K.F. and H.C.G.; project administration, K.K.F. and H.C.G.. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received partial funding for journal processing charges from NUCB Business School.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Special acknowledgement to Mr. Robin Lewis (co-founder of mymizu) and mymizu (Social Innovation Japan, General Incorporated Association) and NUCB Business School for the cooperation throughout the research implementation and data collection phase, and NUCB Business School and Nagoya University of Commerce and Business for administrative and technical support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Alvord, Sarah H., L. David Brown, and Christine W. Letts.. Social entrepreneurship and societal transformation: An exploratory study. The journal of applied behavioral science. 2004, 40.3: 260-282.

- Attanasio, G., Preghenella, N., De Toni, A. F., & Battistella, C. Stakeholder engagement in business models for sustainability: The stakeholder value flow model for sustainable development. Business Strategy and the Environment, 2022, 31( 3), 860– 874. [CrossRef]

- Berglund, Henrik & Sandström, Christian. Business model innovation from an open systems perspective: Structural challenges and managerial solutions. Int. J. of Product Development. 2013, 18. 274–285. [CrossRef]

- Bloom, Paul N., and Brett R. Smith. Identifying the drivers of social entrepreneurial impact: Theoretical development and an exploratory empirical test of SCALERS. Journal of social entrepreneurship. 2010, 1.1: 126-145.

- Bocken, N. M. P., Short, S., Rana, P., & Evans, S. A literature and practice review to develop sustainable 98 Academy of Management Annals January business model archetypes. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2014, 65: 42–56.

- Boons, F. A. A., & Ludeke-Freund, F. Business models for sustainable innovation: State-of-the-art and steps towards a research agenda. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2013, 45: 9–19.

- Bosse, D.A., Phillips, R.A. and Harrison, J.S. Stakeholders, reciprocity and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, Summer, forthcoming. 2009.

- Bowen, Glenn. Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qualitative Research Journal. 2009, 9. 27-40. [CrossRef]

- Bradach, Jeffrey L. Going to scale: The challenge of replicating social programs. Stanford Social Innovation Review. 2003, 19-25.

- Busetto, L., Wick, W. & Gumbinger, C. How to use and assess qualitative research methods. Neurol. Res. Pract. 2020, 2, 14. [CrossRef]

- Cannatelli, Benedetto.. Exploring the contingencies of scaling social impact: A replication and extension of the SCALERS model.VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. 2017, 28: 2707-2733.

- Canestrino et al. Understanding social entrepreneurship: A cultural perspective in business research. Journal of Business Research. 2020, 110, 132–143.

- CASE (Center for the Advancement of Social Entrepreneurship). The CASE 2005 Scaling Social Impact Survey: A Summary of the Findings. CASE. 2006.

- Christoph Zott, Raphael Amit. Business Model Design: An Activity System Perspective, Long Range Planning. 2010, 43, 2–3, Pages 216-226. [CrossRef]

- Dacin, P. A., Dacin, M. T., & Matear, M. Social entrepreneurship: Why we don’t need a new theory and how we move forward from here. Academy of Management Perspectives, 2010, 24(3), 37–57. [CrossRef]

- Dearnley, Christine. A reflection on the use of semi-structured interviews. Nurse researcher. 2005, 13.1.

- Dees, J.G. & Anderson, B.B. & Wei-Skillern, Jane. Scaling social impact. Stanford Social Innovation Review. 2004, 1. 24-32.

- Dees, J. G., & Anderson, B. B.. Framing a theory of social entrepreneurship: Building on two schools of practice and thought. D. Williamson (Ed.), Research on social entrepreneurship: Understanding and contributing to an emerging field (pp. 39–66). Indianapolis, IN: ARNOVA. 2006.

- Dees, J.G. Enterprising nonprofits: What do you do when traditional sources of funding fall short? Harvard Business Review. 1998, 76: 55–67.

- Dees, J. G., Emerson, J., & Economy, P. Enterprising nonprofits: A toolkit for social entrepreneurs. New York: John Wiley & Sons. 2001.

- Dees, J. Gregory. The meaning of social entrepreneurship. Kauffman Center for Entrepreneurial Leadership Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation. 1998.

- Dias, B.D., 2019. Regenerative development–building evolutive capacity for healthy living systems. Retrieved from. In: Management and Applications of Complex Systems, 147.

- Demil, B., Lecocq, X. & Warnier, V. Business model thinking, business ecosystems and platforms: The new perspective on the environment of the organization. Management. 2018, 21, 1213–1228. [CrossRef]

- Demystifying Content Analysis A. J. Kleinheksel, Nicole Rockich-Winston, Huda Tawfik, Tasha R. Wyatt American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education. 2020, 84 (1) 7113. [CrossRef]

- Ebrahim, Alnoor, and V. Kasturi Rangan. What impact? A framework for measuring the scale and scope of social performance. California management review. 2014, 56.3: 118-141.

- Evans, S., Vladimirova, D., Holgado, M., Van Fossen, K., Yang, M., Silva, E. A., and Barlow, C. Y.. Business Model Innovation for Sustainability: Towards a Unified Perspective for Creation of Sustainable Business Models. Bus. Strat. Env. 2017, 26: 597– 608. [CrossRef]

- Francesca Ciulli, Ans Kolk, Christina M. Bidmon, Niels Sprong, Marko P. Hekkert. Sustainable business model innovation and scaling through collaboration. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions. 2022, 45, 289–301. [CrossRef]

- Gerhards, J., Greenwood, D.. One planet living and the legitimacy of sustainability governance: from standardised information to regenerative systems. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2021, 313, 127895.

- Han, Jun & Shah, Sonal. The Ecosystem of Scaling Social Impact: A New Theoretical Framework and Two Case Studies. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Harrison, J.S., Bosse, D.A. & Phillips, R.A. Managing for stakeholders, stakeholder utility functions and competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 2010, 58-74.

- Huang, Ying & Luo, Yadong & Liu, Yi & Yang, Qian. An Investigation of Interpersonal Ties in Interorganizational Exchanges in Emerging Markets: A Boundary-Spanning Perspective. Journal of Management. 2016, 42. 1557-1587. [CrossRef]

- Hutchins, G., Storm, L.. Regenerative leadership the DNA of life-affirming 21st century organizations. Wordzworth Publishing. 2017.

- Islam, Syrus M. Towards an integrative definition of scaling social impact in social enterprises. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 2020, 13: e00164.

- Jenkins, B., & Ishikawa, E. Scaling up inclusive business: Advancing the knowledge and action agenda. International Finance Corporation and Harvard John F. Kennedy School of Government: Washington DC and Cambridge. 2010.

- Kovanen, S.. Social entrepreneurship as a collaborative practice: Literature review and research agenda. Journal of Entrepreneurship, Management and Innovation. 2021, 17(1), 97-128. [CrossRef]

- Lepoutre, J.. Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Exploring Individual and Organizational Characteristics. EIM Research Report. 2011.

- Lorenzo Massa, Christopher L. Tucci, and Allan Afuah. A Critical Assessment of Business Model Research. ANNALS. 2017, 11, 73–104. [CrossRef]

- Ludeke-Freund, F., Massa, L., Bocken, N., Brent, A., & Musango, J.. Business Models for Shared Value: Main Report. Cape Town: Network for Business Sustainability South-Africa. 2016.

- Mair, J., Robinson, J., Hockerts, K. Entrepreneurial Opportunity in Social Purpose Business Ventures. In: (eds) Social Entrepreneurship. Palgrave Macmillan, London. 2006. [CrossRef]

- McMullen, J.S. and Bergman, B.J., Jr.. Social Entrepreneurship and the Development Paradox of Prosocial Motivation: A Cautionary Tale. Strat. Entrepreneurship Journal. 2017, 11: 243-270. [CrossRef]

- Molecke, Greg, and Jonatan Pinkse. Accountability for social impact: A bricolage perspective on impact measurement in social enterprises. Journal of Business Venturing. 2017, 32.5 :550-568.

- mymizu n.d., About Us, mymizu, accessed 10 July 2023, https://www.mymizu.co/about.

- mymizu n.d., Become a mymizu Monthly Supporter, mymizu, accessed 10 July 2023, https://www.mymizu.co/en/monthly-supporter.

- mymizu n.d., mymizu’s Second Open Source Hackathon!, mymizu, accessed 10 July 2023, https://www.mymizu.co/blog-en/mymizu-hackathon-2023.

- mymizu n.d., The story of mymizu web—how a community can create waves, mymizu, accessed 10 July 2023, https://www.mymizu.co/blog-en/mymizu-web-hackathon.

- mymizu n.d., Volunteer Registration, mymizu, accessed 10 July 2023, https://www.mymizu.co/volunteer.

- mymizu, mymizu by Social Innovation Japan [mobile app]. App Store. 2019. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/mymizu/id1480535233.

- mymizu, mymizu by Social Innovation Japan [mobile app]. App Store. 2021. https://apps.apple.com/us/app/mymizu/id1480535233.

- Nicholls, A. SE: New models of sustainable social change (1st ed.). New York: Oxford University Press. 2006.

- Norris, G. Handprint-based netpositive assessment. Sustainability and health initiative for NetPositive Enterprise (SHINE), Center for Health and the global environment. Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. 2015.

- Norris, G.A., Burek, J., Moore, E.A., Kirchain, R.E., Gregory, J.. Sustainability health initiative for NetPositive Enterprise handprint methodological framework. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2021, 26 (3), 528–542.

- Reuber, A. Rebecca, Esther Tippmann, and Sinéad Monaghan. Global scaling as a logic of multinationalization. Journal of International Business Studies. 2021, 52: 1031-1046.

- Ronan Bolton, Matthew Hannon. Governing sustainability transitions through business model innovation: Towards a systems understanding. Research Policy. 2016, 45,9, 1731-1742. [CrossRef]

- Ruskin, J., Seymour, R.G. and Webster, C.M. Why Create Value for Others? An Exploration of Social Entrepreneurial Motives. Journal of Small Business Management. 2016, 54: 1015-1037. [CrossRef]

- Santos, F.M. A Positive Theory of Social Entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Ethics. 2012, 111, 335–351. [CrossRef]

- Scheuerle, Thomas, and Bjoern Schmitz. Inhibiting factors of scaling up the impact of social entrepreneurial organizations–a comprehensive framework and empirical results for Germany. Journal of Social Entrepreneurship. 2016, 7.2: 127-161.

- Sherman, David A. Social entrepreneurship: pattern-changing entrepreneurs and the scaling of social impact. Working paper. Case Western Reserve University. 2006.

- Slawinski, N., Winsor, B., Mazutis, D., Schouten, J.W., Smith, W.K.. Managing the paradoxes of place to foster regeneration. Organ. Environ. 2021, 34 (4), 595–618.

- Smith, Brett R., Geoffrey M. Kistruck, and Benedetto Cannatelli. The impact of moral intensity and desire for control on scaling decisions in social entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Ethics. 2016, 133: 677-689.

- Stemler, Steve. An overview of content analysis. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. 2001, 7, 17. [CrossRef]

- Steven G. Rogelberg. Handbook of Research Methods in Industrial and Organizational Psychology. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. 2004, chapter 8.

- Täuscher, Karl, and Nizar Abdelkafi. Scalability and robustness of business models for sustainability: A simulation experiment. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2018, 170: 654-664.

- Teasdale, S., Roy, M. J., Nicholls, A., & Hervieux, C. Turning rebellion into money? Social entrepreneurship as the strategic performance of systems change. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal. 2023, 17(1), 19– 39. [CrossRef]

- Uvin, Peter. Fighting hunger at the grassroots: Paths to scaling up. World Development. 1995, 23.6: 927-939.

- Wahl, D. Designing Regenerative Cultures. Triarchy Press. 2016.

- Winter, Sidney G., and Gabriel Szulanski. Replication as strategy. Organization science. 2001, 12.6: 730-743.

- Yin, Robert K.. Case study research: Design and methods. SAGE Publishing. 2009, 5.

- Zahra, S. A., E. Gedajlovic, D. O. Neubaum, and J. M. Shulman. A Typology of Social Entrepreneurs: Motives, Search Processes and Ethical Challenges, Journal of Business Venturing. 2009, 24(5), 519–532.

- Zeyen, A., Beckmann, M., & Akhavan, R.. Social Entrepreneurship Business Models: Managing Innovation for Social and Economic Value Creation. In C-P. Zimth, & C. G. von Mueller (Eds.), Management Perspektiven für die Zivilgesellschaft des 21. Jahrhunderts: Management als Liberal Art. 2014, 107-132. Wiesbaden: Springer-Verlag. [CrossRef]

- Zott, C., Amit, R. H., & Massa, L.. The Business Model: Recent Developments and Future Research. Journal of Management. 2011. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).