Submitted:

11 August 2023

Posted:

13 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

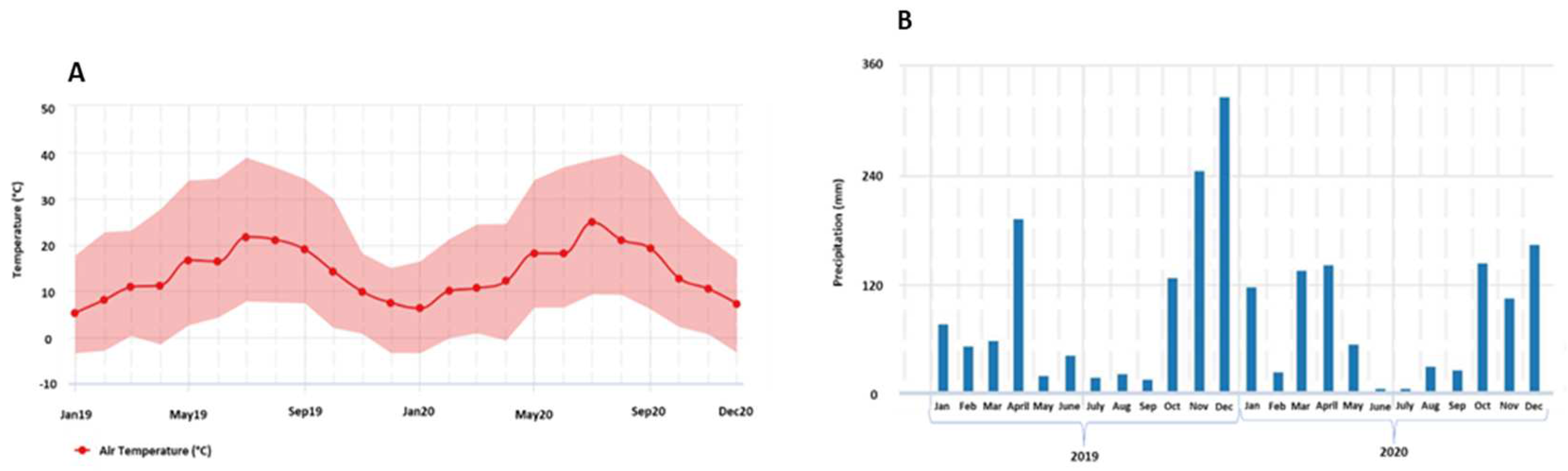

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant material and sampling

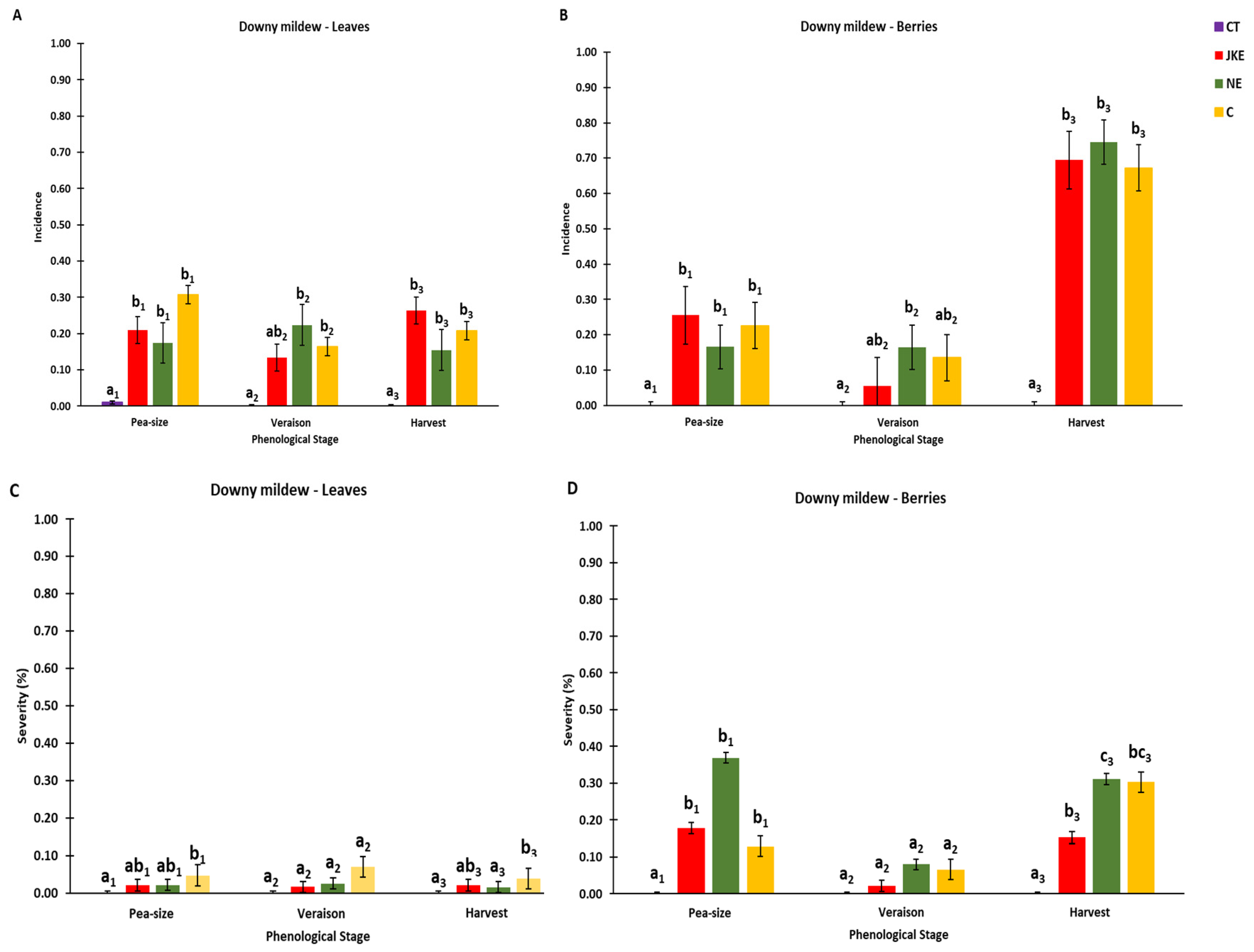

2.2. Downy mildew incidence

2.3. Determination of bioactive compounds

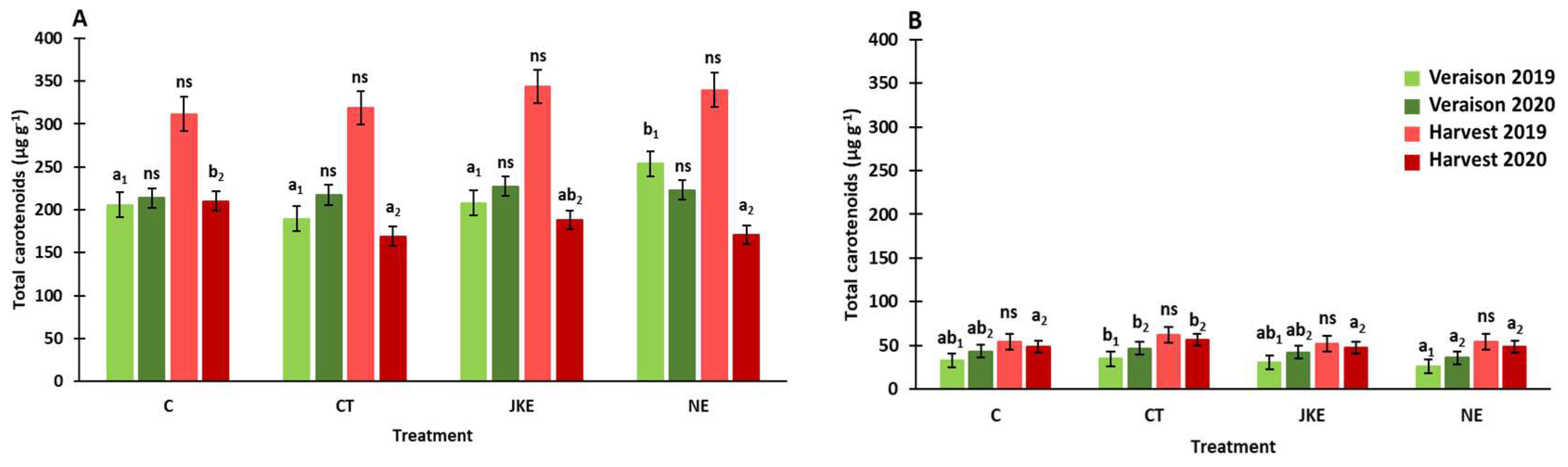

2.3.1. Total carotenoids

2.3.2. Total phenolics

2.3.3. Flavonoids

2.3.4. Total anthocyanins

2.4. Antioxidant activity assays

2.4.1. ABTS•+ radical-scavenging activity

2.4.2. DPPH radical-scavenging activity

2.4.3. FRAP assay

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results

3.1. Downy mildew incidence

3.2. Effect on leaf and berry bioactive compounds

3.3. Effect on leaf and berry antioxidant activity

4. Discussion

4.1. Downy mildew incidence

4.2. Leaf and berry bioactive compounds

4.3. Leaf and berry antioxidant activity

5. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gutiérrez-Gamboa G, Zheng W, Martínez de Toda F. Current viticultural techniques to mitigate the effects of global warming on grape and wine quality: A comprehensive review. Food Res Int 2021, 139. [CrossRef]

- Jones, G. Uma Avaliação do Clima para a Região Demarcada do Douro : Uma análise das condições climáticas do passado, presente e futuro para a produção de vinho. AVID: Portugal, 2013; pp. 5–80. [Google Scholar]

- Fraga H, De Cortázar Atauri IG, Malheiro AC, Moutinho-Pereira J, Santos JA. Viticulture in Portugal: A review of recent trends and climate change projections. OENOOne 2017, 51, 61–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong FP, Wilcox WF. Distribution of baseline sensitivities to azoxystrobin among isolates of Plasmopara viticola. Plant Dis 2000, 84, 275–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz A, Poinssot B, Daire X, Adrian M, Bézier A, Lambert B, et al. Laminarin elicits defense responses in grapevine and induces protection against Botrytis cinerea and Plasmopara viticola. Mol Plant-Microbe Interact 2003, 16, 1118–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhadj A, Saigne C, Telef N, Cluzet S, Bouscaut J, Corio-Costet MF, et al. Methyl jasmonate induces defense responses in grapevine and triggers protection against Erysiphe necator. J Agric Food Chem 2006, 54, 9119–25. [CrossRef]

- Petit A, Wojnarowiez G, Panon M, Baillieul F, Clément C, Fontaine F, et al. Botryticides affect grapevine leaf photosynthesis without inducing defense mechanisms. Planta 2009, 229, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jermini M, Blaise P, Gessler C. Quantification of the influence of the downy mildew (Plasmopara viticola) epidemics on the compensatory capacities of Vitis vinifera “Merlot” to limit the qualitative yield damage. Vitis - J Grapevine Res 2010, 49, 153–60. [Google Scholar]

- Delaunois B, Farace G, Jeandet P, Clément C, Baillieul F, Dorey S, et al. Elicitors as alternative strategy to pesticides in grapevine? Current knowledge on their mode of action from controlled conditions to vineyard. Environ Sci Pollut Res 2014, 21, 4837–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garde-Cerdán T, Mancini V, Carrasco-Quiroz M, Servili A, Gutiérrez-Gamboa G, Foglia R, et al. Chitosan and Laminarin as alternatives to copper for Plasmopara viticola control: Effect on grape amino acid. J Agric Food Chem 2017, 65, 7379–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro E, Gonçalves B, Cortez I, Castro I. The role of biostimulants as alleviators of biotic and abiotic stresses in grapevine: A review. Plants 2022, 11, 396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghazal HN, Al-Shahwany AW, Al-Dulaimy FT. Control of gray mold on tomato plants by spraying Piper nigrum and Urtica dioica extracts under greenhouse condition. Iraqi J Sci 2019, 60, 961–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodino S, Butu M, Butu A. Alternative antimicrobial formula for plant protection. Bull USAMV Ser Agric 2018, 75, 32–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njogu M, Nyankanga R, Muthomi J, Muindi E. Studies on the effects of stinging nettle extract, phosphoric acid and conventional fungicide combinations on the management of potato late blight and tuber yield in the highlands of Kenya. J Agric Food Sci 2014, 2, 119–27. [Google Scholar]

- Godlewska K, Pacyga P, Michalak I, Biesiada A, Szumny A, Pachura N, et al. Field-scale evaluation of botanical extracts effect on the yield, chemical composition and antioxidant activity of celeriac (Apium graveolens L. var. rapaceum). Molecules 2020, 25, 4212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godlewska K, Pacyga P, Michalak I, Biesiada A, Szumny A, Pachura N, et al. Effect of botanical extracts on the growth and nutritional quality of field-grown white head cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata). Molecules 2021, 26, 1992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maričić B, Radman S, Romić M, Perković J, Major N, Urlić B, et al. Stinging nettle (Urtica dioica L.) as an aqueous plant-based extract fertilizer in green bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) sustainable agriculture. Sustain 2021, 13. [CrossRef]

- Đurić M, Mladenović J, Bošković-Rakočević L, Šekularac G, Brković D, Pavlović N. Use of different types of extracts as biostimulators in organic agriculture. Acta Agric Serbica 2019, 24, 27–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godard S, Slacanin I, Viret O, Gindro K. Induction of defence mechanisms in grapevine leaves by emodin- and anthraquinone-rich plant extracts and their conferred resistance to downy mildew. Plant Physiol Biochem 2009, 47, 827–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrandt U, Marsell A, Riederer M. Direct effects of physcion, chrysophanol, emodin, and pachybasin on germination and appressorium formation of the barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) powdery mildew fungus Blumeria graminis f. sp. hordei (DC.) Speer. J Agric Food Chem 2018, 66, 3393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki El-Readi M, Yehia Eid S, Al-Amodi HS, Wink M. Fallopia japonica: Bioactive secondary metabolites and molecular mode of anticancer. J Tradit Med Clin Naturop 2016, 05. [CrossRef]

- Oleszek M, Kowalska I, Oleszek W. Phytochemicals in bioenergy crops. Phytochem Rev 2019, 18, 893–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borovaya S, Lukyanchuk L, Manyakhin A, Zorikova O. Effect of Reynoutria japonica extract upon germination and upon resistance of its seeds against phytopathogenic fungi Triticum aestivum L., Hordeum vulgare L., and Glycine max (L.) Merr. Org Agric 2020, 10, 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenz DH, Eichhorn KW, Bleiholder H, Klose R, Meier U, Weber E. Growth stages of the grapevine: phenological growth stages of the grapevine (Vitis vinifera L. ssp. vinifera)—Codes and descriptions according to the extended BBCH scale. Aust J Grape Wine Res 1995, 1, 100–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPPO. Plasmopara viticola. EPPO Bull 2001, 31, 313–7. [CrossRef]

- Lichtenthaler, HK. Chlorophylls and carotenoids: Pigments of photosynthetic biomembranes. Methods Enzym 1987, 350–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton V, Rossi J. Colorometry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. Am J Enol Vitic 1965, 144–58.

- Dewanto V, Wu X, Adom KK, Liu RH. Thermal processing enhances the nutritional value of tomatoes by increasing total antioxidant activity. J Agric Food Chem 2002, 3010–4.

- Lee J, Durst RW, Wrolstad RE, Eisele T, Giusti MM, Haché J, et al. Determination of total monomeric anthocyanin pigment content of fruit juices, beverages, natural colorants, and wines by the ph differential method: Collaborative study. J AOAC Int 2005, 88, 1269–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng J-F, Fang Y-L, Qin M-Y, Zhuang X-F, Zhang Z-W. Varietal differences among the phenolic profiles and antioxidant properties of four cultivars of spine grape (Vitis davidii Foex) in Chongyi County (China). Food Chem 2012, 134, 2049–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali Shehat W, Sohail Akh M, Alam T. Extraction and estimation of anthocyanin content and antioxidant activity of some common fruits. Trends Appl Sci Res 2020, 15, 179–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Re R, Pellegrini N, Proteggente A, Pannala A, Yang M, Rice-Evans C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic Biol Med 1999, 26, 1231–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stratil P, Klejdus B, Kubáň V. Determination of total content of phenolic compounds and their antioxidant activity in vegetablesevaluation of spectrophotometric methods. J Agric Food Chem 2006, 54, 607–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brand-Williams W, Cuvelier ME, Berset C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. Lebnsm Wiss Technol 1995, 25–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Moreno C, Larrauri JA, Saura-Calixto F. A procedure to measure the antiradical efficiency of polyphenols. J Sci Food Agric 1998, 76, 270–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddhraju P, Becker K. Antioxidant properties of various solvents extracts of total phenolic constituents from three different agroclimatic origins of drumstick tree (Moringa oleifera Lam) leaves. J Agric Food Chem 2003, 2144–55.

- Benzie IFF, Strain JJ. The Ferric Reducing Ability of Plasma (FRAP) as a Measure of “Antioxidant Power”: The FRAP Assay. Anal Biochem 1996, 239, 70–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ADVID. Boletim ano vitícola 2019; ADVID. Vila Real, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- ADVID. Boletim Ano Vitícola 2020; ADVID. Vila Real, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Patočka J, Navrátilová Z, Ovando M. Biologically active compounds of Knotweed (Reynoutria spp.). Mil Med Sci Lett 2017, 86, 17–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suteu D, Rusu L, Zaharia C, Badeanu M, Daraban G. Challenge of utilization vegetal extracts as natural plant protection products. Appl Sci 2020, 10, 8913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cucu A-A, Baci G-M, Dezsi Ş, Nap M-E, Beteg FI, Bonta V, et al. New approaches on Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica) bioactive compounds and their potential of pharmacological and beekeeping activities: challenges and future Directions. Plants 2021, 10, 2621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota HP, Paudel KR, Khanal S, Baral A, Panth N, Adhikari-Devkota A, et al. Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica L.): nutritional composition, bioactive compounds, and food functional properties. Molecules 2022, 27, 5219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young AJ, Britton G. Carotenoids and oxidative stress; Curr. Res. Photosynth., Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, 1990; pp. 3381–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang H, Ullah F, Zhou D-X, Yi M, Zhao Y. Mechanisms of ROS regulation of plant development and stress responses. Front Plant Sci 2019, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mona, MA. The potential of Moringa oleifera extract as a biostimulant in enhancing the growth, biochemical and hormonal contents in rocket (Eruca vesicaria subsp. sativa) plants. Int J Plant Physiol Biochem 2013, 5, 42–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman M, Mukta JA, Sabir AA, Gupta DR, Mohi-Ud-Din M, Hasanuzzaman M, et al. Chitosan biopolymer promotes yield and stimulates accumulation of antioxidants in strawberry fruit. PLoS One 2018, 13, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flamini R, Mattivi F, De Rosso M, Arapitsas P, Bavaresco L. Advanced knowledge of three important classes of grape phenolics: Anthocyanins, stilbenes and flavonols. Int J Mol Sci 2013, 14, 19651–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh RK, Soares B, Goufo P, Castro I, Cosme F. , Pinto-Sintra AL, et al. Chitosan upregulates the genes of the ROS pathway and enhances the antioxidant potential of grape (Vitis vinifera L. ‘Touriga Franca’ and ’Tinto Cão’) tissues. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irani H, ValizadehKaji B, Naeini MR. Biostimulant-induced drought tolerance in grapevine is associated with physiological and biochemical changes. Chem Biol Technol Agric 2021, 8, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrandino A, Lovisolo C. Abiotic stress effects on grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.): Focus on abscisic acid-mediated consequences on secondary metabolism and berry quality. Environ Exp Bot 2014, 103, 138–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, D. Grape growth, anthocyanin and phenolic compounds content of early ripening cv. Cardinal table grape (V. vinifera L.) as affected by various doses of foliar biostimulant applications with gibberellic acid. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2018, 60, 253–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soppelsa S, Kelderer M, Casera C, Bassi M, Robatscher P, Matteazzi A, et al. Foliar applications of biostimulants promote growth, yield and fruit quality of strawberry plants grown under nutrient limitation. Agronomy 2019, 9, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macheix JJ, Fleuriet A, Billot J. Fruit phenolic; CRC: Press, Boca Raton. USA., 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan D, Antolovich M, Prenzler P, Robards K, Lavee S. Biotransformations of phenolic compounds in Olea europaea L. Sci Hortic (Amsterdam) 2002, 92, 147–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frioni T, Tombesi S, Quaglia M, Calderini O, Moretti C, Poni S, et al. Metabolic and transcriptional changes associated with the use of Ascophyllum nodosum extracts as tools to improve the quality of wine grapes (Vitis vinifera cv. Sangiovese) and their tolerance to biotic stress. J Sci Food Agric 2019, 99, 6350–63. [CrossRef]

- Braidot E, Zancani M, Petrussa E, Peresson C, Bertolini A, Patui S, et al. Transport and accumulation of flavonoids in grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.). Plant Signal Behav 2008, 3, 626–32. [CrossRef]

- Fraga H, Malheiro AC, Moutinho-Pereira J, Santos JA. An overview of climate change impacts on European viticulture. Food Energy Secur 2012, 1, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Ward D, Ribeiro A, Barreales D, Castro J, Verdial J, Feliciano M, et al. Climate change potential effects on grapevine bioclimatic indices: A case study for the Portuguese demarcated Douro Region (Portugal). BIO Web Conf 41st World Congr Vine Wine 2019, 12, 01013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drobek M, Frąc M, Cybulska J. Plant biostimulants: Importance of the quality and yield of horticultural crops and the improvement of plant tolerance to abiotic stress - A review. Agronomy 2019, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parađiković N, Teklić T, Zeljković S, Lisjak M, Špoljarević M. Biostimulants research in some horticultural plant species—A review. Food Energy Secur 2018, 8, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu DP, Li Y, Meng X, Zhou T, Zhou Y, Zheng J, et al. Natural antioxidants in foods and medicinal plants: Extraction, assessment and resources. Int J Mol Sci 2017, 18, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rockenbach II, Rodrigues E, Gonzaga LV, Caliari V, Genovese MI, Gonalves AEDSS, et al. Phenolic compounds content and antioxidant activity in pomace from selected red grapes (Vitis vinifera L. and Vitis labrusca L.) widely produced in Brazil. Food Chem 2011, 127, 174–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kupe M, Karatas N, Unal MS, Ercisli S, Baron M, Sochor J. Phenolic composition and antioxidant activity of peel, pulp and seed extracts of different clones of the Turkish grape cultivar ‘Karaerik.’. Plants 2021, 10, 2154. [CrossRef]

- Speranza S, Knechtl R, Witlaczil R, Schönlechner R. Reversed-phase HPLC characterization and quantification and antioxidant capacity of the phenolic acids and flavonoids extracted from eight varieties of sorghum grown in Austria. Front Plant Sci 2021, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Bioactive Compound | Plant organ | Growth stage | C | CT | JKE | NE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Total Phenolics (mg.g-1) |

Leaf | Veraison 2019 | 13.33 ± 1.35 | 13.51 ± 1.32 | 11.25 ± 1.01 | 11.02 ± 1.06 |

| Veraison 2020 | 22.19 ± 1.69a2 | 27.72 ± 0.94b2 | 28.09 ± 2.14b2 | 27.33 ± 1.64b2 | ||

| Harvest 2019 | 11.36 ± 0.57 | 14.86 ± 1.31 | 12.90 ± 1.30 | 12.97 ± 1.20 | ||

| Harvest 2020 | 23.70 ± 0.85 | 26.67 ± 1.28 | 26.91 ± 1.02 | 24.14 ± 1.29 | ||

| Berry | Veraison 2019 | 18.34 ± 3.16ab1 | 14.14 ± 2.15a1 | 17.86 ± 1.73ab1 | 26.31 ± 4.41b1 | |

| Veraison 2020 | 50.38 ± 1.32 | 50.60 ± 4.82 | 63.58 ± 5.35 | 59.33 ± 4.81 | ||

| Harvest 2019 | 16.99 ± 1.52 | 16.87 ± 2.11 | 13.61 ± 1.20 | 17.58 ± 1.94 | ||

| Harvest 2020 | 31.74 ± 4.15 | 32.54 ± 2.82 | 32.88 ± 3.55 | 28.30 ± 1.81 | ||

| Total Anthocyanins (mg.g-1) | Berry | Veraison 2019 | 1.87 ± 0.58 | 6.39 ± 0.33 | 3.01 ± 2.42 | 2.86 ± 1.12 |

| Veraison 2020 | 3.26 ± 0.50 | 4.00 ± 1.57 | 1.27 ± 0.28 | 3.34 ± 0.70 | ||

| Harvest 2019 | 2.20 ± 0.33a1 | 6.97 ± 1.30b1 | 2.46 ± 0.85a1 | 3.05 ± 1.88ab1 | ||

| Harvest 2020 | 6.94 ± 0.94 | 9.95 ± 2.33 | 7.05 ± 1.48 | 6.39 ± 0.47 | ||

|

Flavonoids (mg.g-1) |

Leaf | Veraison 2019 | 2.54 ± 0.21a1 | 3.63 ± 0.25b1 | 2.54 ± 0.19a1 | 2.70 ± 0.17a1 |

| Veraison 2020 | 3.59 ± 0.50a2 | 5.54 ± 0.70b2 | 4.27 ± 0.57ab2 | 4.05 ± 0.42ab2 | ||

| Harvest 2019 | 2.85 ± 0.37a1 | 4.11 ± 0.35b1 | 3.22 ± 0.32ab1 | 3.51 ± 0.54ab1 | ||

| Harvest 2020 | 4.19 ± 0.22a2 | 5.35 ± 0.19b2 | 5.54 ± 0.34b2 | 4.30 ± 0.32a2 | ||

| Berry | Veraison 2019 | 4.60 ± 0.62a1 | 4.33 ± 0.80a1 | 7.19 ± 0.44b1 | 5.67± 0.86ab1 | |

| Veraison 2020 | 18.32 ± 2.31 | 14.27 ± 1.38 | 18.90 ± 2.57 | 15.72 ± 1.64 | ||

| Harvest 2019 | 6.59 ± 1.86 | 4.03 ± 0.85 | 6.17 ± 3.73 | 5.43 ± 0.85 | ||

| Harvest 2020 | 8.51 ± 0.99 | 9.33 ± 1.45 | 9.61 ± 0.99 | 9.03 ± 1.97 |

| Antioxidant activity assay | Plant organ | Growth stage | C | CT | JKE | NE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

ABTS•+ (µmol Trolox µg-1) |

Leaf | Veraison 2019 | 0.46 ± 0.03b1 | 0.31 ± 0.02a1 | 0.41 ± 0.03b1 | 0.45 ± 0.04b1 |

| Veraison 2020 | 0.31 ± 0.02b2 | 0.13 ± 0.02a2 | 0.19 ± 0.04a2 | 0.21 ± 0.03a2 | ||

| Harvest 2019 | 0.47 ± 0.04b1 | 0.27 ± 0.04a1 | 0.40 ± 0.04b1 | 0.41 ± 0.03b1 | ||

| Harvest 2020 | 0.17 ± 0.02b2 | 0.12 ± 0.03ab2 | 0.08 ± 0.02a2 | 0.15 ± 0.03ab2 | ||

| Berry | Veraison 2019 | 65.19 ± 9.71ab1 | 84.40 ± 4.60b1 | 77.18 ± 8.39ab1 | 56.32 ± 8.76a1 | |

| Veraison 2020 | 59.36 ± 6.79b2 | 56.48 ± 11.51b2 | 38.29 ± 9.73ab2 | 27.89 ± 7.03a2 | ||

| Harvest 2019 | 79.01 ± 7.16 | 78.62 ± 5.49 | 73.49 ± 7.49 | 80.59 ± 6.51 | ||

| Harvest 2020 | 63.08 ± 4.72 | 75.81 ± 9.30 | 59.71 ± 7.78 | 54.82 ± 9.96 | ||

|

DPPH (µmol Trolox µg-1) |

Leaf | Veraison 2019 | 0.79 ± 0.05 | 0.73 ± 0.03 | 0.79 ± 0.05 | 0.80 ± 0.04 |

| Veraison 2020 | 1.09 ± 0.04 | 1.03 ± 0.04 | 1.08 ± 0.07 | 1.02 ± 0.05 | ||

| Harvest 2019 | 0.74 ± 0.04b1 | 0.62 ± 0.03a1 | 0.70 ± 0.03ab1 | 0.69 ± 0.03ab1 | ||

| Harvest 2020 | 1.24 ± 0.05 | 1.28 ± 0.03 | 1.22 ± 0.03 | 1.24 ± 0.04 | ||

| Berry | Veraison 2019 | 59.74 ± 2.52ab1 | 69.53 ± 2.44b1 | 66.07 ± 4.52b1 | 54.61 ± 3.12a1 | |

| Veraison 2020 | 49.16 ± 2.14 | 49.42 ± 2.13 | 45.14 ± 2.40 | 47.02 ± 2.87 | ||

| Harvest 2019 | 65.48 ± 1.89 | 66.34 ± 3.58 | 68.23 ± 2.54 | 70.52 ± 1.73 | ||

| Harvest 2020 | 57.57± 1.49 | 58.99 ± 3.98 | 53.04 ± 2.94 | 61.74 ± 5.64 | ||

|

FRAP (µmol Trolox µg-1) |

Leaf | Veraison 2019 | 0.70 ± 0.07a1 | 0.92 ± 0.05b1 | 0.74 ± 0.06a1 | 0.70 ± 0.06a1 |

| Veraison 2020 | 0.38 ± 0.03 | 0.53 ± 0.05 | 0.54 ± 0.07 | 0.48 ± 0.06 | ||

| Harvest 2019 | 0.58 ± 0.03a1 | 0.97 ± 0.11b1 | 0.66 ± 0.06a1 | 0.62 ± 0.05a1 | ||

| Harvest 2020 | 0.48 ± 0.04 | 0.56 ± 0.05 | 0.58 ± 0.04 | 0.50 ± 0.04 | ||

| Berry | Veraison 2019 | 33.82 ± 4.80b1 | 19.22 ± 1.05a1 | 24.87 ± 2.75ab1 | 34.58 ± 4.15b1 | |

| Veraison 2020 | 55.40 ± 3.30a2 | 64.68 ± 4.25ab2 | 66.21 ± 1.66b2 | 69.77 ± 3.99b2 | ||

| Harvest 2019 | 23.70 ± 1.18ab1 | 20.17 ± 1.97a1 | 19.29 ± 2.50a1 | 25.86 ± 1.27b1 | ||

| Harvest 2020 | 43.10 ± 2.19ab2 | 43.82 ± 2.80b2 | 42.55 ± 3.31ab2 | 35.32 ± 1.31a2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).