Submitted:

11 August 2023

Posted:

11 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methodology

2.1. Bitumen

2.2. Waste Engine Oil

2.3. Filter paper

2.4. Crumb Rubber

2.5. Polyphosphoric Acid

2.6. Preparation of Modified-Bitumen

3. Experimental Program

3.1. Physical tests

3.2. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy

3.3. Rheological Testing of Asphalt binder

3.4. Bitumen Bond Strength Test

4. Results & Discussion

4.1. Physical Testing Results

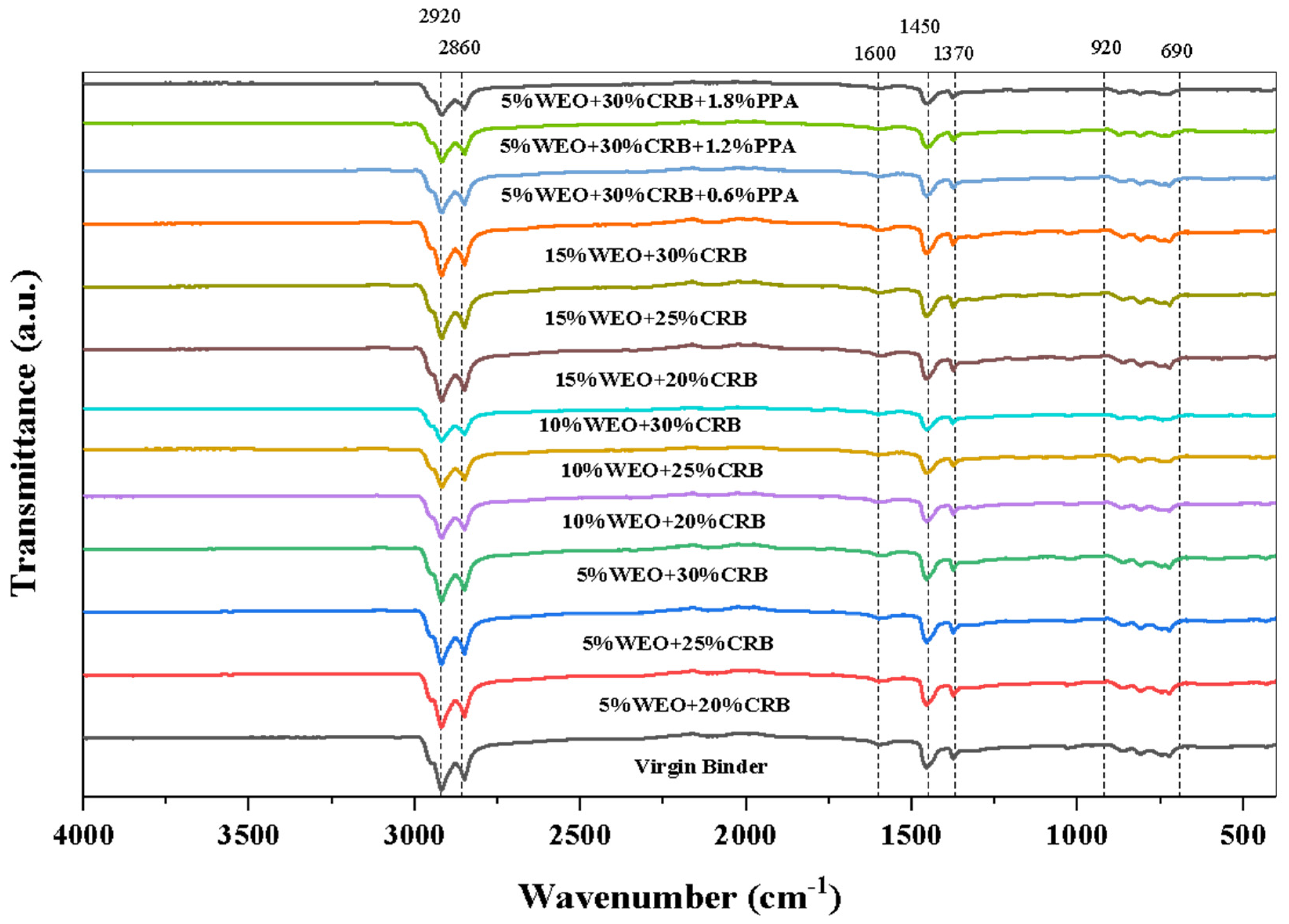

4.2. FTIR Analysis

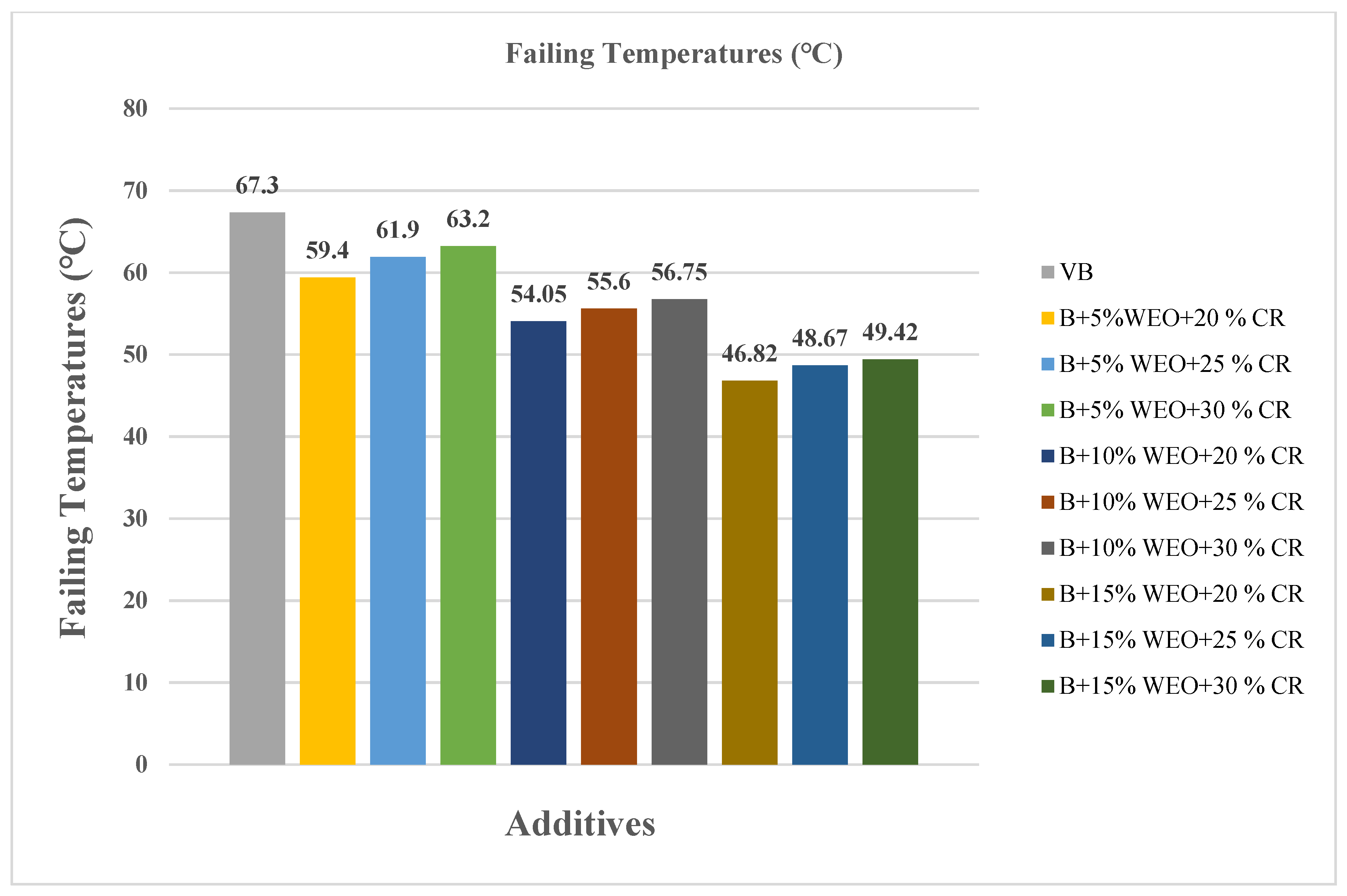

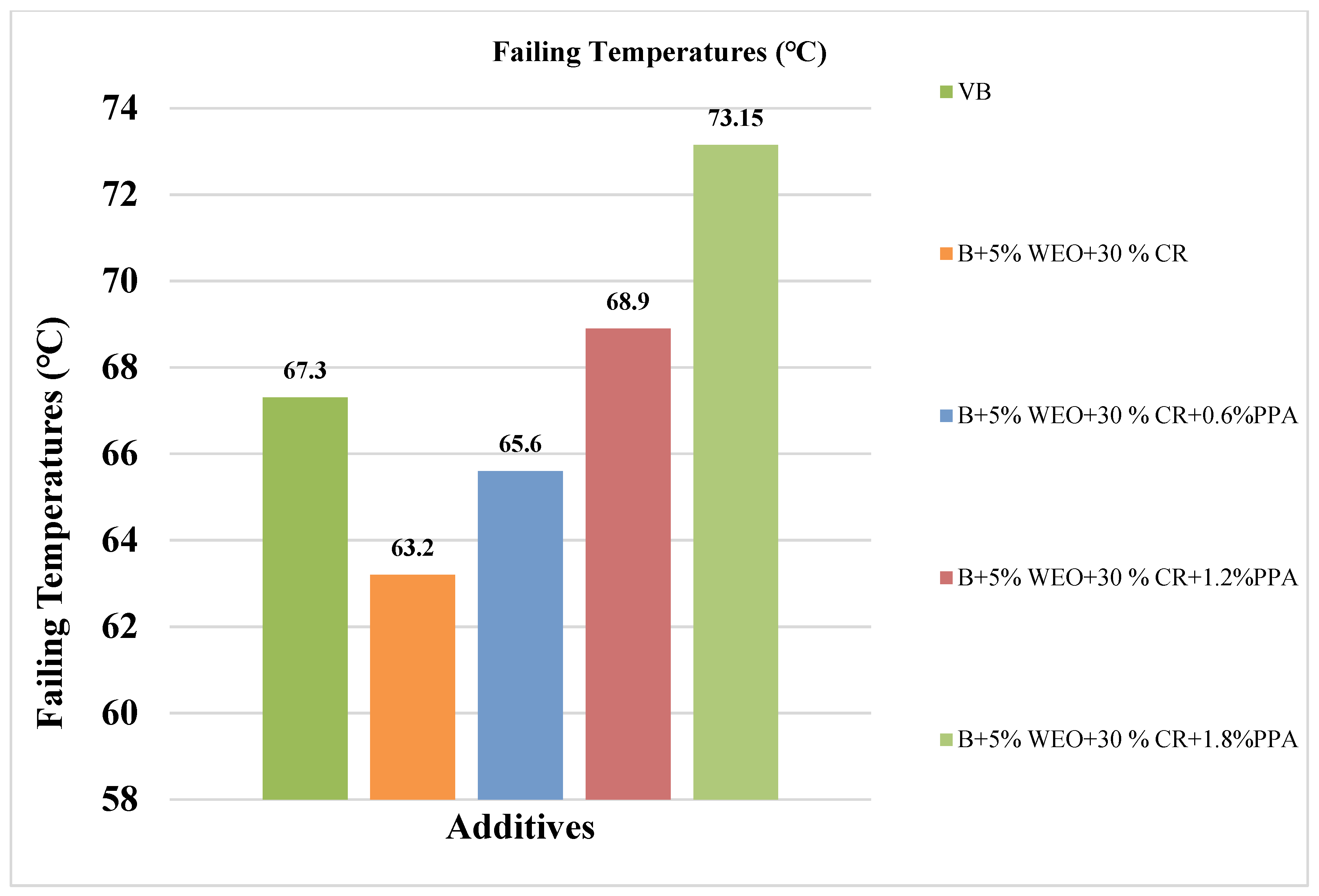

4.3. Performance Grading Test Results

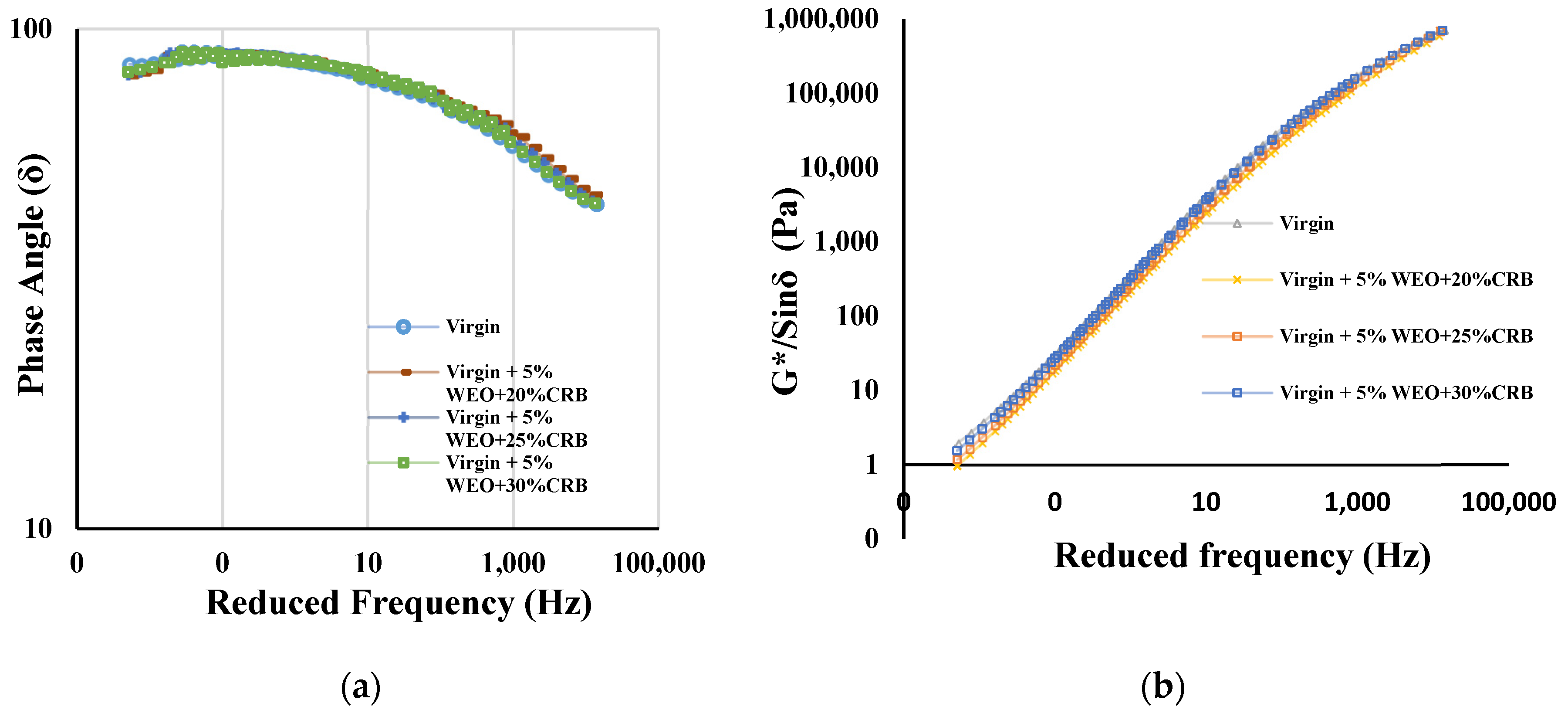

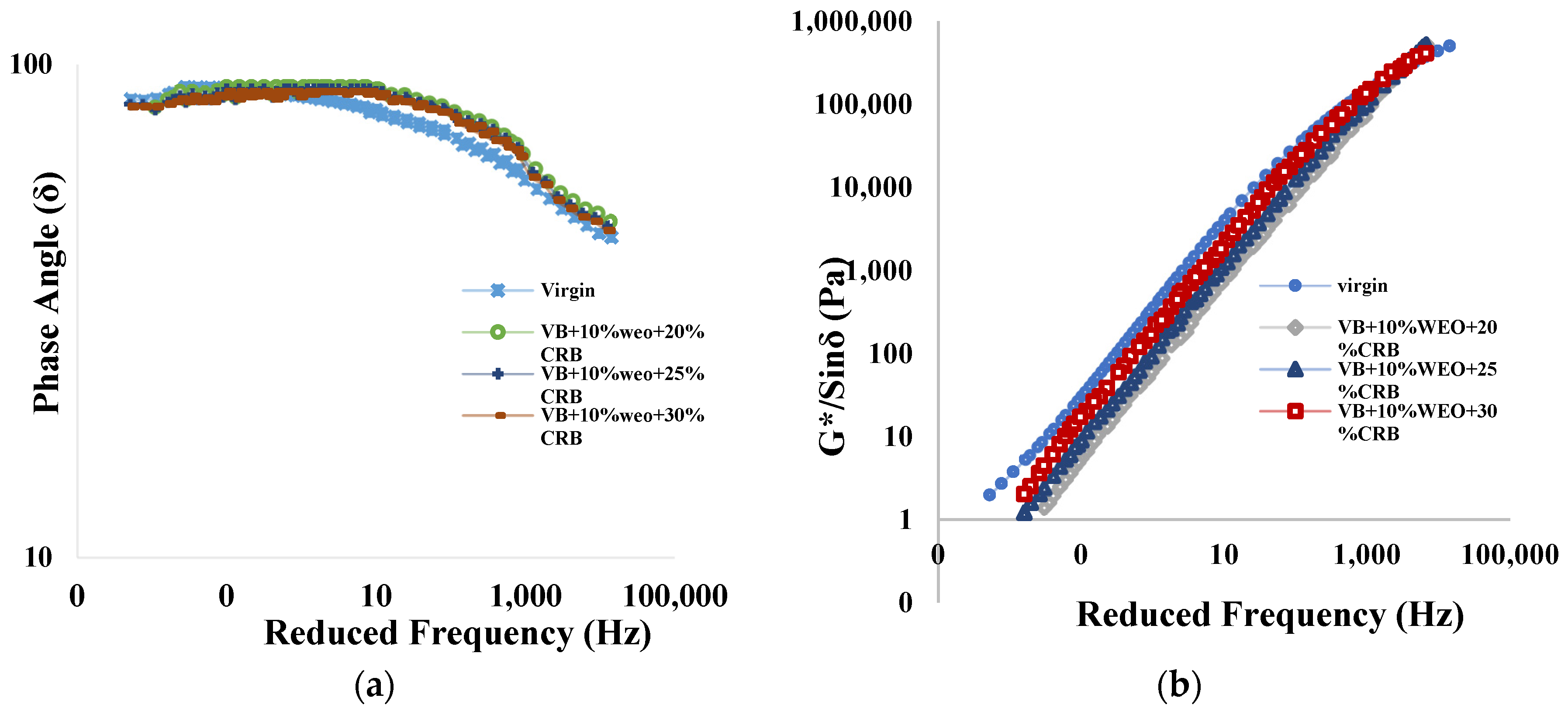

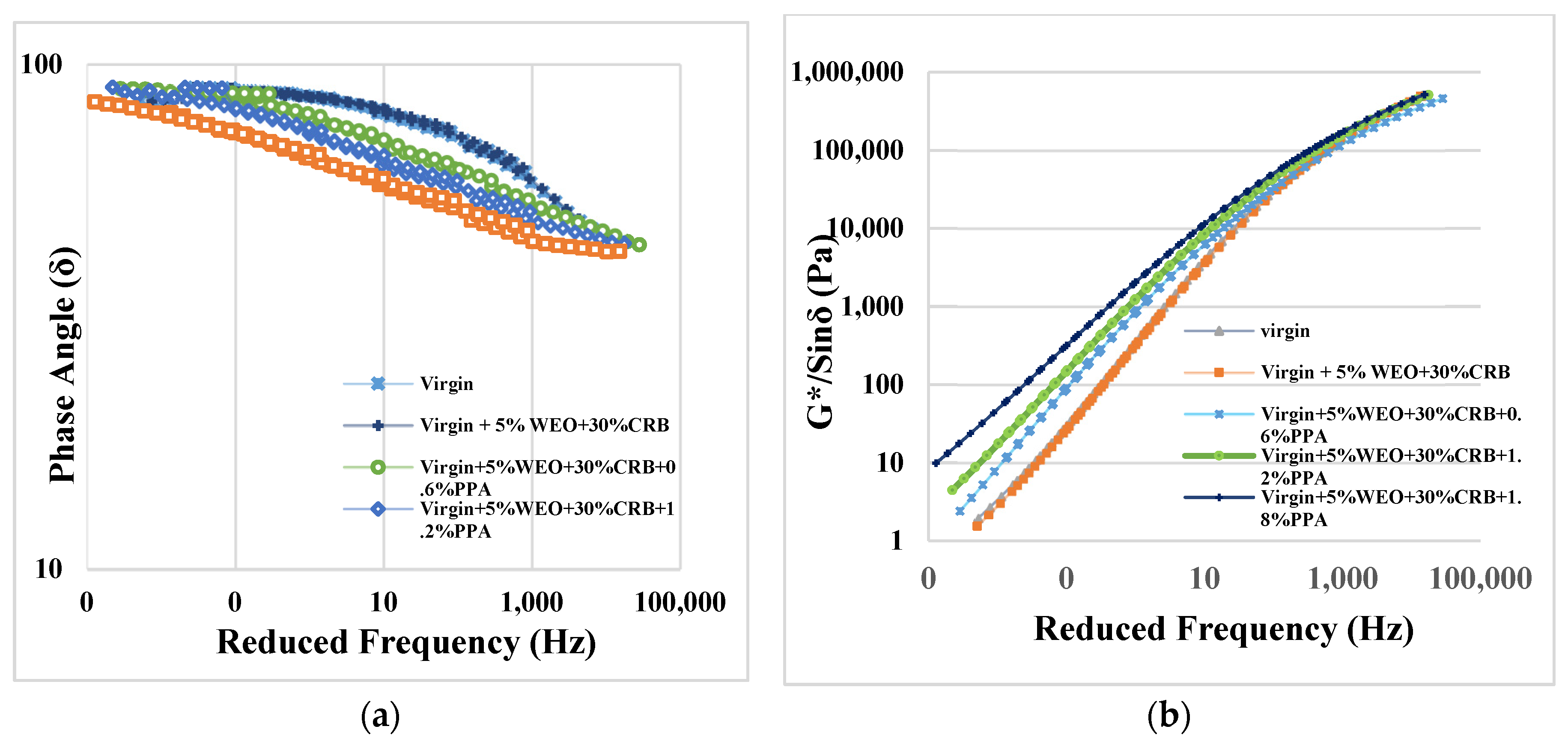

4.4. Frequency Sweep Test Results

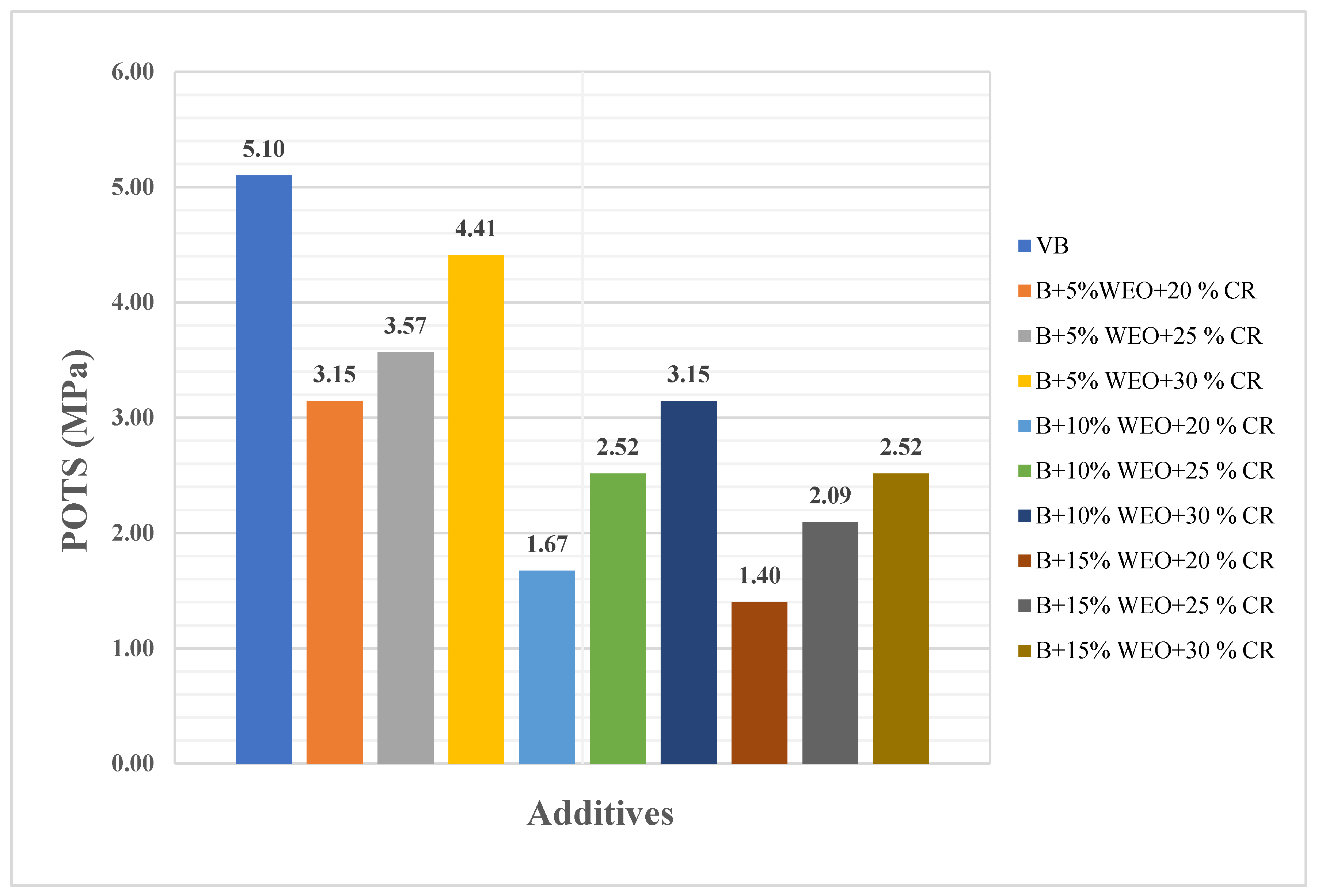

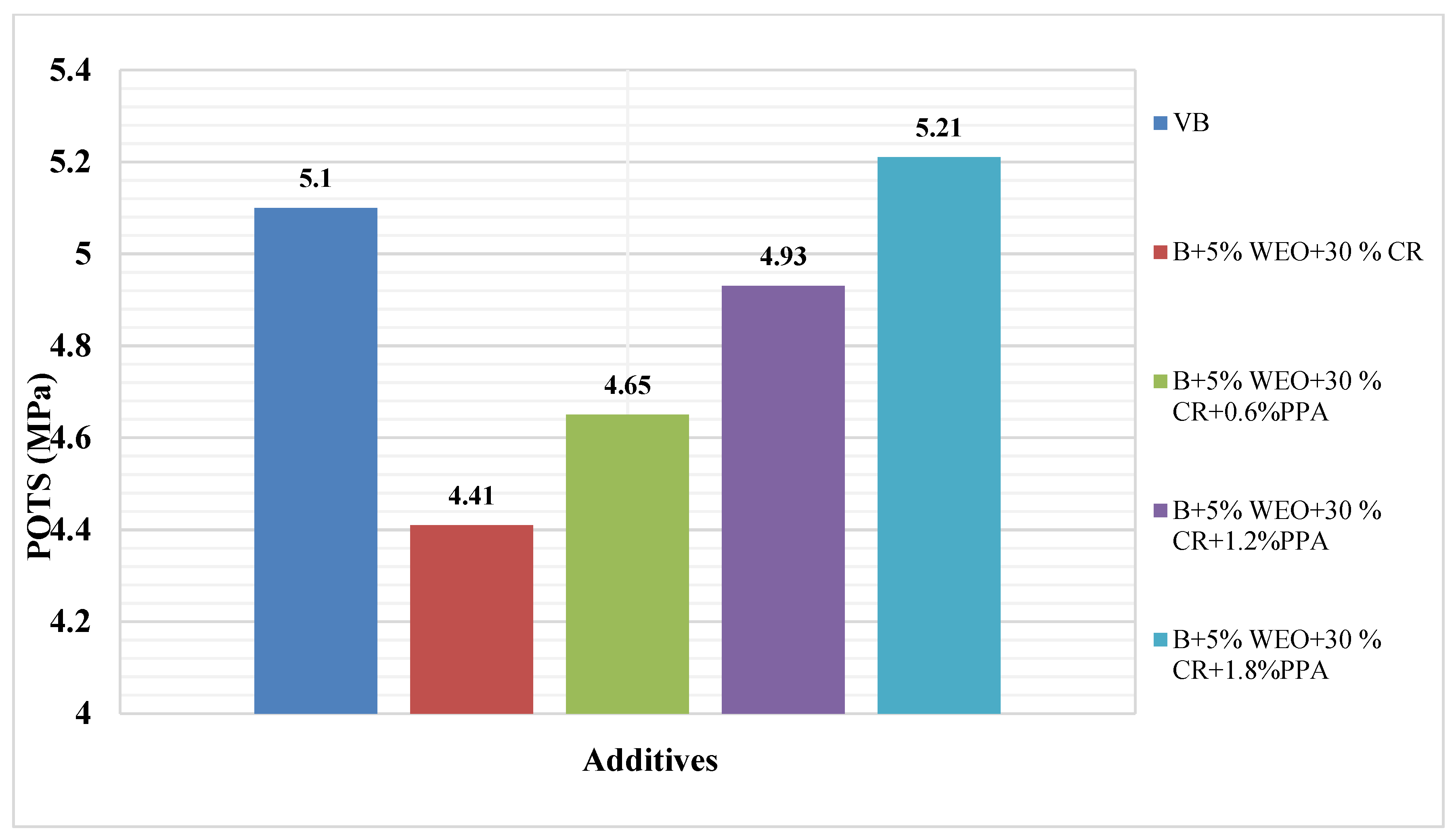

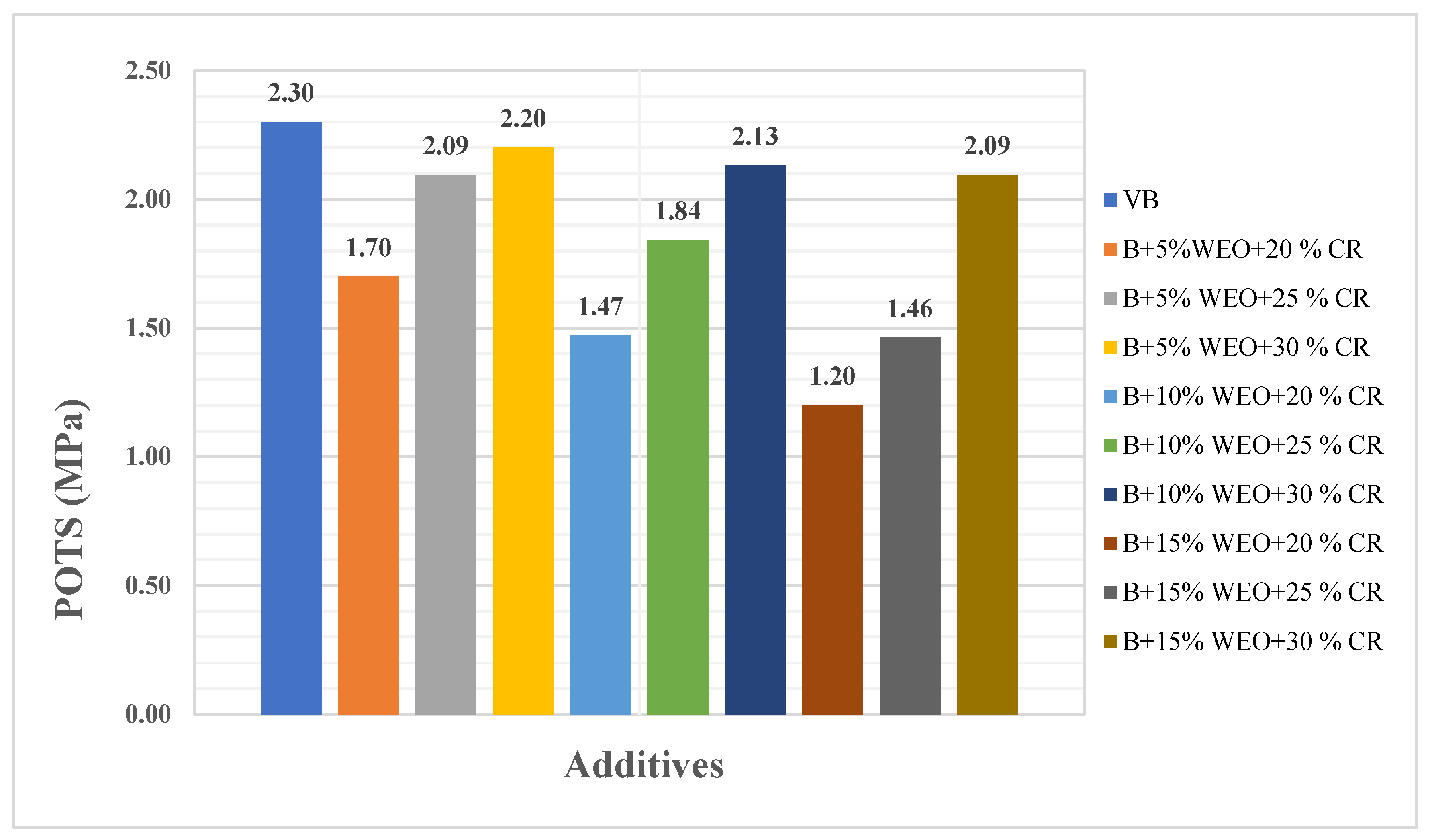

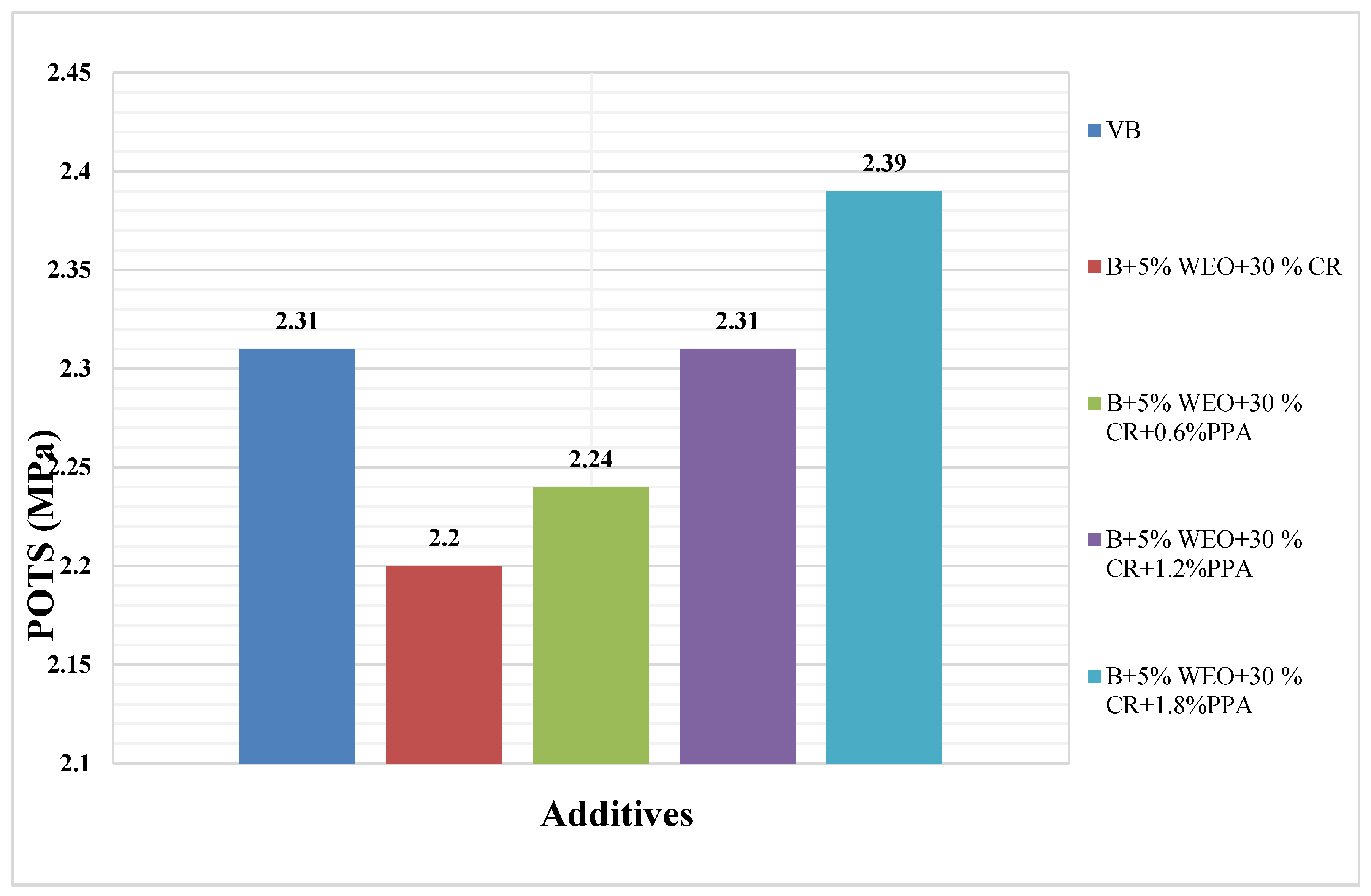

4.5. Bitumen Bond Strength Test Results

5. Statistical Analysis

5.1. Viscosity Tests

5.2. Complex Modulus

5.3. Moisture Susceptibility Tests

6. Conclusions and Recommendations

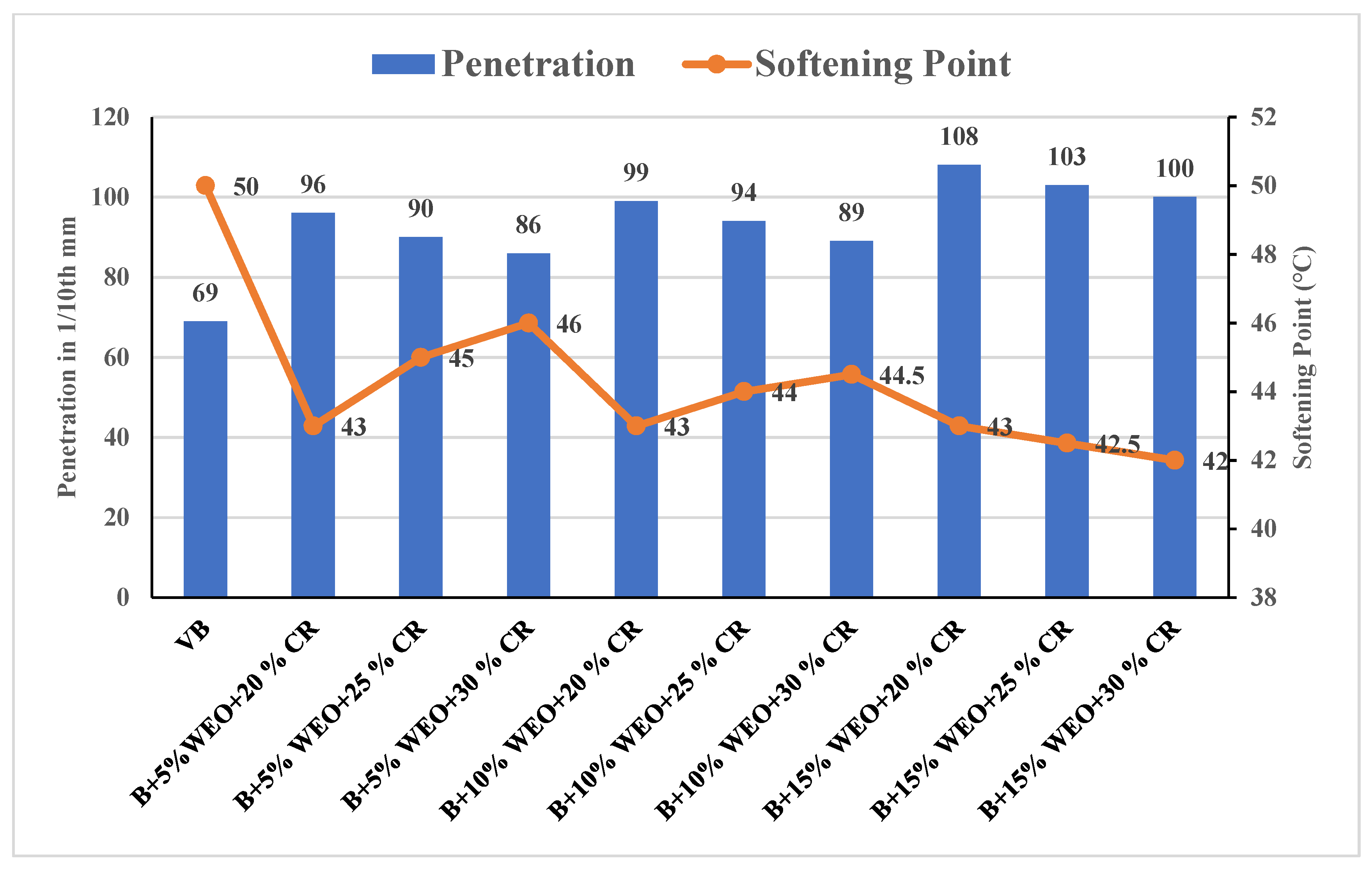

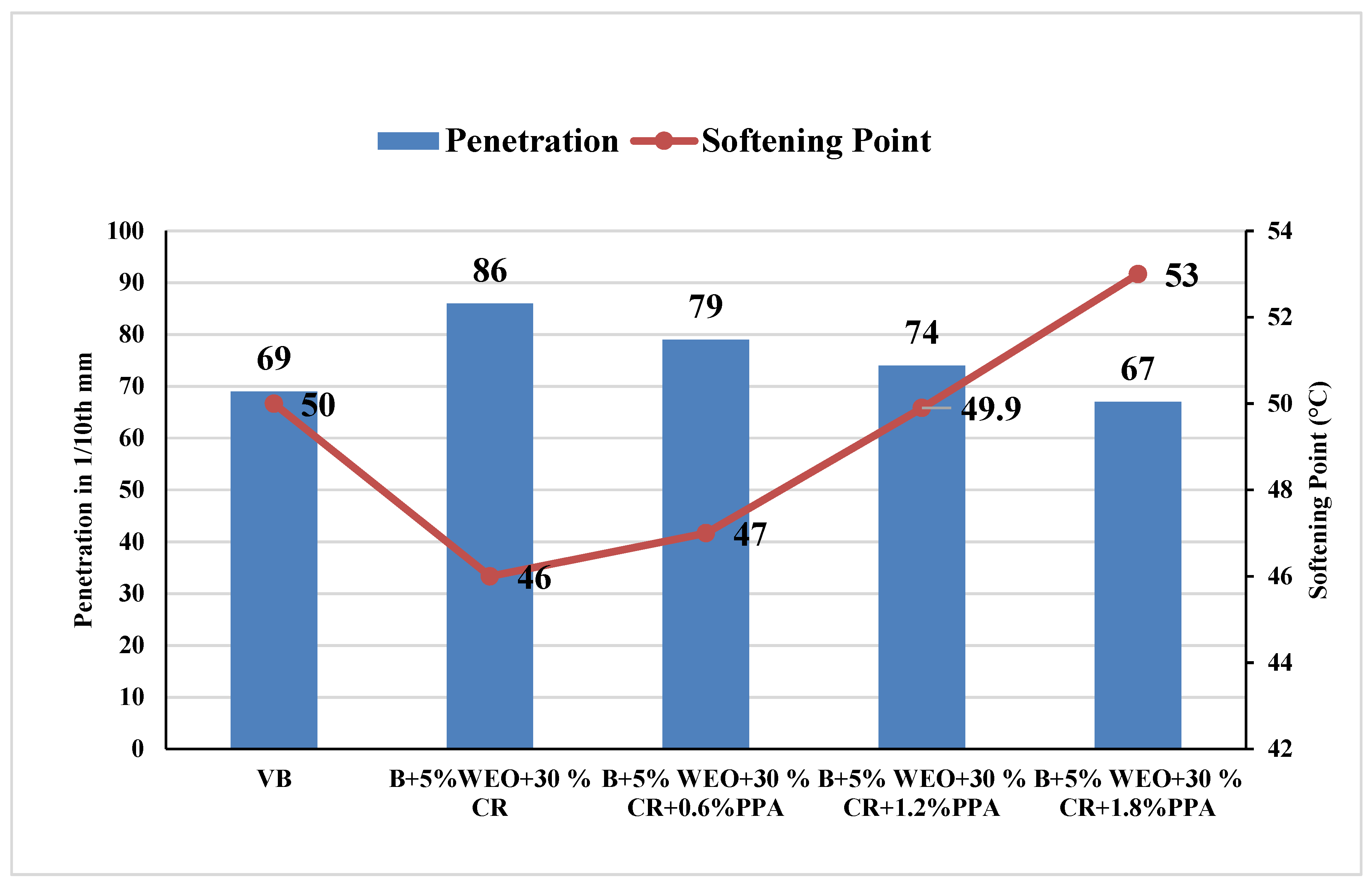

- The conventional bitumen test results confirmed that WEO with crumb rubber in the binder increased the penetration and reduced the softening point and consistency because waste engine oil softened the bitumen. The best combination of 5% WEO and 30% CR seems closest to virgin binder in terms of its properties where an increase of 20% was observed in the penetration value, while an 8% decrease as found the softening point compared to a virgin binder. To improve it further, this combination has been further modified by adding 0.6%, 1.2%, and 1.8% PPA. Best results were observed at 1.8% PPA which improved the consistency of partially synthetic bitumen by decreasing its penetration up to 3% and increasing its softening point to 2%.

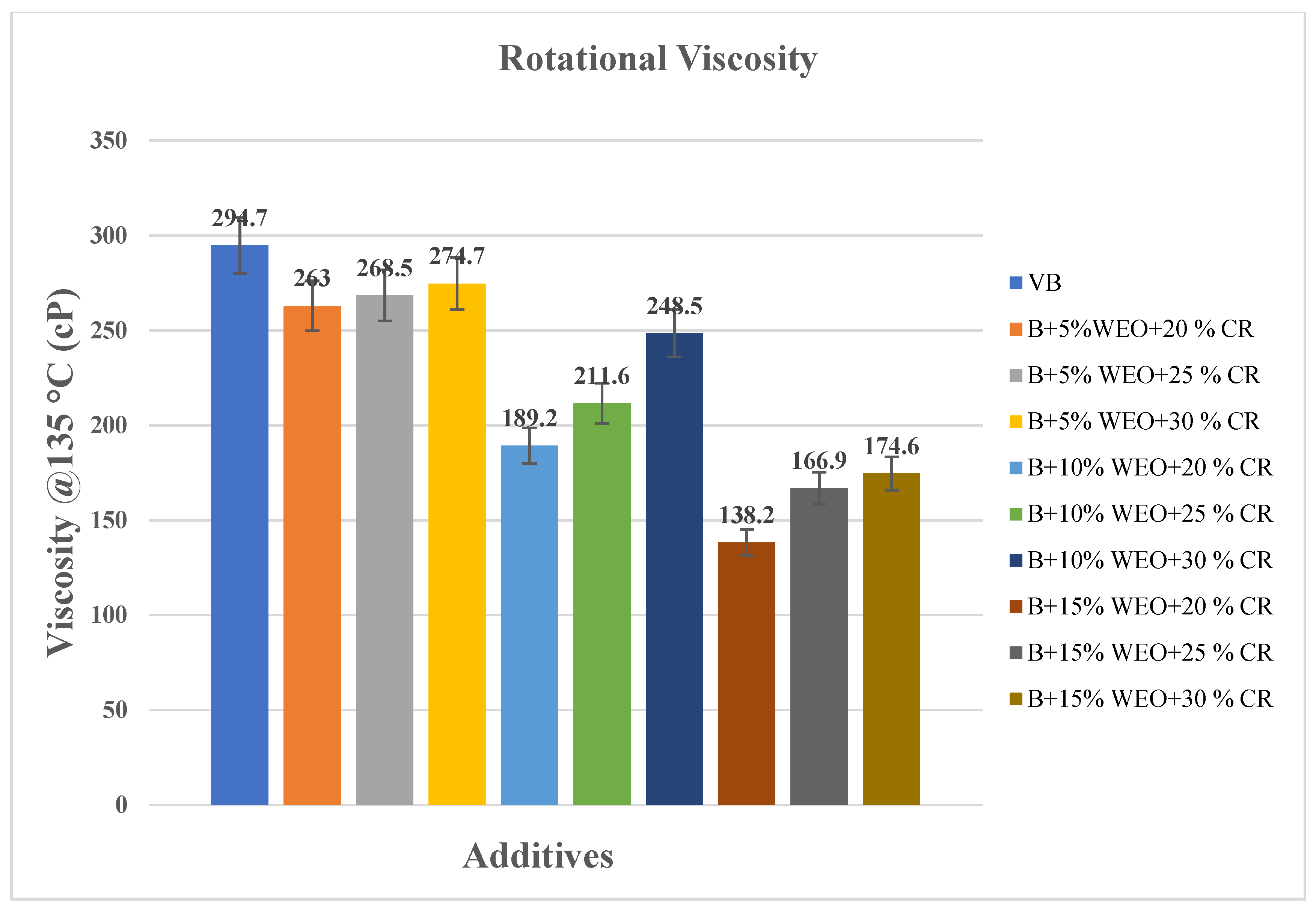

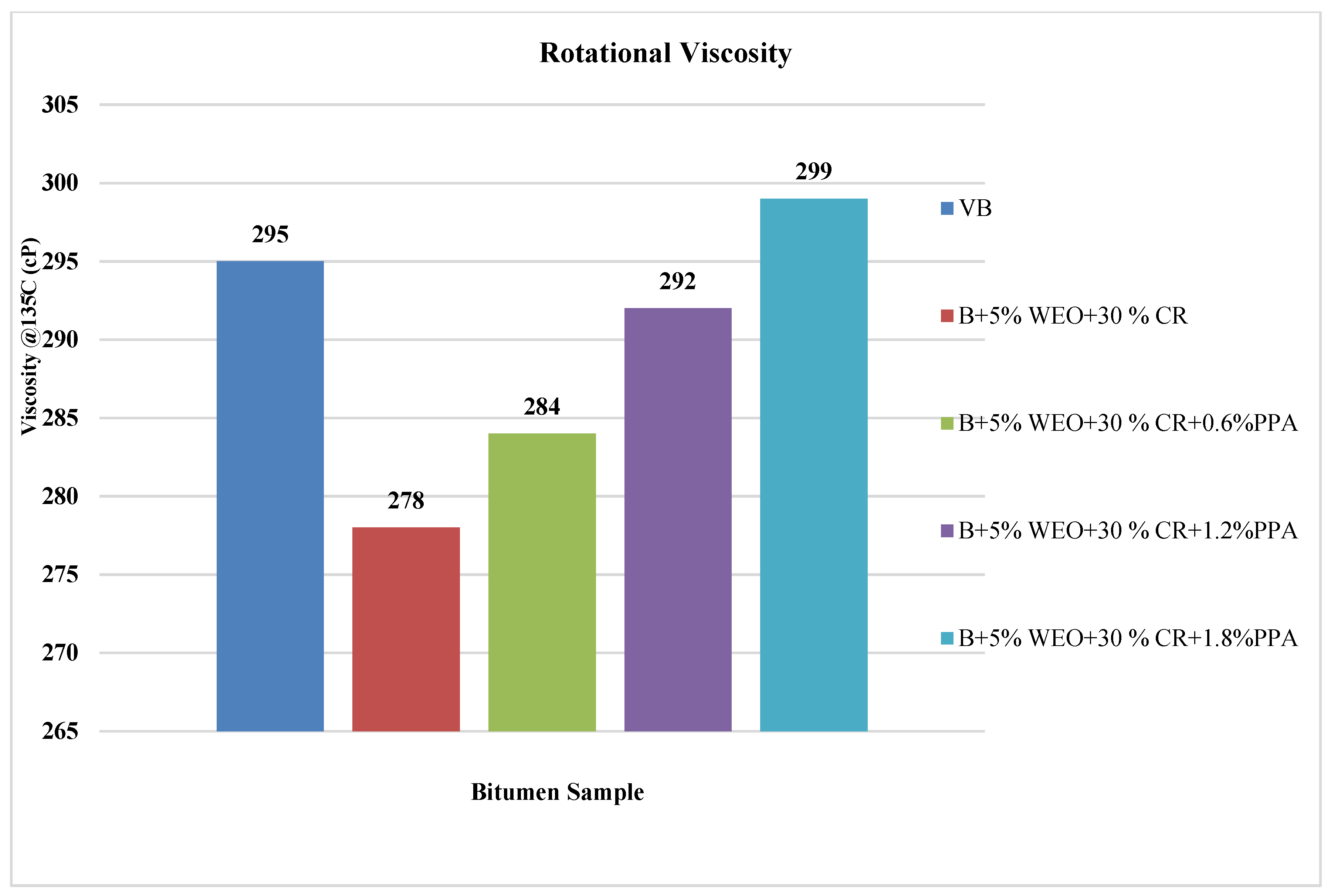

- The RV results revealed that incorporating CR and WEO into bitumen reduced viscosity. It was due to the dissolving of the asphaltene content of the binder, which is mainly responsible for its viscosity. Adding 5% WEO and 30% CR by total binder content reduced viscosity by 2 % The best combination of 5% WEO and 30% CR seems closest to virgin binder in terms of its viscosity. Further, the addition of 1.8% PPA increased the viscosity of the virgin binder by 2%.

- The frequency sweep test results concluded that combining WEO and CRB in the asphalt binder imparts high-temperature performance by decreasing the complex modulus. With the addition of 5% WEO and 30% CR by total binder content, the Complex modulus decreased by 21%, and the phase angle increased by 4%. The rut resistance and complex modulus improved by adding 1.8% PPA into the asphalt binder. Complex modulus increased by 20%, and the phase angle improved by 1%. Its mean PPA increased the complex modulus values by stiffening the binder.

- With the addition of 5% WEO and 30% CR by total binder content, after 24 hours of dry and wet conditioning, POTS values decrease by 13% and 9%. It is because the WEO softens the bitumen, which makes it more susceptible to moisture damage. But the higher dosage of WEO, more than 5% WEO, proved harmful against moisture resistivity. However, adding crumb rubber can improve the resistance against moisture for better adhesion but does not fulfill the binder requirement. PPA improved the bonding strength of asphalt binder with the addition of 1.8% PPA, and POTS values increased by 5% and 4% after 24 hours of dry and wet conditioning.

- Statistical analysis results are compatible with the present results and previous literature. In comparison, PPA improved high-temperature performance remarkably well. The statistical study determined that PPA analyzed its susceptibility to moisture remarkably well.

7. Recommendations

Acknowledgment

References

- Abbas, S., Zaidi, S.B.A., and Ahmed, I., 2022. Performance evaluation of asphalt binders modified with waste engine oil and various additives. International Journal of Pavement Engineering 1–13. [CrossRef]

- Abdalfattah, I.M.A., El-Badawy, S., Ibrahim, M., Amin, I., El-Badawy, S.M., Breakah, T., and Ibrahim, M.H.Z., 2016. Effect of Functionalization and Mixing Process on the Rheological Properties of Asphalt Modified with Carbon Nanotubes. American Journal of Civil Engineering and Architecture 4(3), 90–97.

- Abdul Hassan, N., Ruzi, N.A., Mohd Shukry, N.A., Putra Jaya, R., Hainin, M.R., Mohd Kamaruddin, N.H., and Abdullah, M.E., 2019. Physical properties of bitumen containing diatomite and waste engine oil. Malaysian Journal of Fundamental and Applied Sciences 15(4), 528–531. [CrossRef]

- Abukhettala, M., 2016. Use of recycled materials in road construction. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Civil, Structural and Transportation Engineering (ICCSTE’16); pp. 1–8.

- Ahmad, M.F., Ahmed Zaidi, S.B., Fareed, A., Ahmad, N., and Hafeez, I., 2022. Assessment of sugar cane bagasse bio-oil as an environmental friendly alternative for pavement engineering applications. International Journal of Pavement Engineering 23(8), 2761–2772. [CrossRef]

- Aodah, H.H., Kareem, Y.N.A., and Chandra, S., 2012. Performance of bituminous mixes with different aggregate gradations and binders. International Journal of Engineering and Technology 2(11), 2049–3444.

- Arabani, M. and Tahami, S.A., 2017. Assessment of mechanical properties of rice husk ash modified asphalt mixture. Construction and Building Materials 149, 350–358. [CrossRef]

- ASTM D 5, 1997. Standard Test Method for Penetration of Bituminous Materials. Annual Book of ASTM Standards. 04.03, 1–3.

- ASTM D36/ D36M-14e1, 2014. Standard Test Method for Softening Point of Bitumen (Ring-and-Ball Apparatus). ASTM International 1(D), 1–5.

- Attia, M. and Abdelrahman, M., 2009. Enhancing the performance of crumb rubber-modified binders through varying the interaction conditions. International Journal of Pavement Engineering 10(6), 423–434. [CrossRef]

- Baldino, N., Gabriele, D., Lupi, F.R., Oliviero Rossi, C., Caputo, P., and Falvo, T., 2013. Rheological effects on bitumen of polyphosphoric acid (PPA) addition. Construction and Building Materials 40, 397–404. [CrossRef]

- Brasileiro, L., Moreno-Navarro, F., Tauste-Martínez, R., Matos, J., and Rubio-Gámez, M. del C., 2019. Reclaimed polymers as asphalt binder modifiers for more sustainable roads: A review. Sustainability (Switzerland) 11(3), 1–20. [CrossRef]

- Cetin, A., 2013. Effects of Crumb Rubber Size and Concentration on Performance of Porous Asphalt Mixtures. International Journal of Polymer Science 2013, 1–10. [CrossRef]

- Counts, T.W., 2023. Tons of solid waste generated [online]. Available from: https://www.theworldcounts.com/challenges/planet-earth/state-of-the-planet/solid-waste.

- DeDene, C.D., 2011. Investigation of using waste engine oil blended with reclaimed asphalt materials to improve pavement recyclability. Michigan Technological University, Houghton, Michigan. [CrossRef]

- Domingos, M.D.I. and Faxina, A.L., 2015. Rheological analysis of asphalt binders modified with Elvaloy® terpolymer and polyphosphoric acid on the multiple stress creep and recovery test. Materials and Structures 48(5), 1405–1416. [CrossRef]

- El-Shorbagy, A.M., El-Badawy, S.M., and Gabr, A.R., 2019. Investigation of waste oils as rejuvenators of aged bitumen for sustainable pavement. Construction and Building Materials 220, 228–237. [CrossRef]

- ELTWATİ, A., ENIEB, M., AHMEED, S., AL-SAFFAR, Z., and MOHAMED, A., 2022. Effects of waste engine oil and crumb rubber rejuvenator on the performance of 100% RAP binder. Journal of Innovative Transportation 3(1), 8–15. [CrossRef]

- Fang, C., Yu, R., Liu, S., and Li, Y., 2013. Nanomaterials applied in asphalt modification: A review. Journal of Materials Science and Technology 29(7), 589–594. [CrossRef]

- Fareed, A., Zaidi, S.B.A., Ahmad, N., Hafeez, I., Ali, A., and Ahmad, M.F., 2020. Use of agricultural waste ashes in asphalt binder and mixture: A sustainable solution to waste management. Construction and Building Materials 259, 120575. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Z., Zhao, P., Yao, D., and Li, X., 2020. Performance Evaluation of Waste Engine Oil Regenerated SBS Modified Bitumen. In CICTP 2020; American Society of Civil Engineers: Reston, VA; pp. 1150–1162. [CrossRef]

- Fini, E.H., Hajikarimi, P., Mohammad, R., and Nejad, F.M., 2015. Physiochemical,Rheological, and Oxidative Aging Characteristics of Asphalt Binder in the Presence of Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 28, 04015133. [CrossRef]

- Formela, K., 2021. Sustainable development of waste tires recycling technologies – recent advances, challenges and future trends. Advanced Industrial and Engineering Polymer Research 4(3), 209–222. [CrossRef]

- Gohar, M., Ahmad, N., and Haroon, W., 2022. Effect of Addition of Crumb Rubber on Bitumen Performance Grade ( PG ) and Effect of Addition of Crumb Rubber on Bitumen Performance Grade ( PG ) and Rutting Resistance. In 1st International Conference on Advances in Civil & Environmental Engineering; University of Engineering & Technology Taxila: Pakistan; pp. 1–6.

- Guo, S., Dai, Q., Si, R., Sun, X., and Lu, C., 2017. Evaluation of properties and performance of rubber-modified concrete for recycling of waste scrap tire. Journal of Cleaner Production 148, 681–689. [CrossRef]

- Hainin, M.R., A. Aziz, M.M., Adnan, A.M., Abdul Hassan, N., Putra Jaya, R., and Y Liu, H., 2015. Performance of Modified Asphalt Binder with Tire Rubber Powder. Jurnal Teknologi 73(4), 55–60.

- Hao, P., Zhai, R., Zhang, Z., and Cao, X., 2019. Investigation on performance of polyphosphoric acid (PPA)/SBR compound-modified asphalt mixture at high and low temperatures. Road Materials and Pavement Design 20(6), 1376–1390.

- Haroon, W., Ahmad, N., and Mashaan, N., 2022. Effect of Quartz Nano-Particles on the Performance Characteristics of Asphalt Mixture. Infrastructures 7(5), 60. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., 2008. Rubber concentrations on rheology of aged asphalt binders. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 20(3), 221–229. [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.R., Katman, H.Y., Karim, M.R., Koting, S., and Mashaan, N.S., 2013. A review on the effect of crumb rubber addition to the rheology of crumb rubber modified bitumen. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering 2013. [CrossRef]

- Int, I., Res, J.P., Dedene, C.D., and You, Z., 2014. The Performance of Aged Asphalt Materials Rejuvenated with Waste Engine Oil. International journal of pavement research and technology 7(2), 145–152.

- Jamal, Hafeez, I., Yaseen, G., and Aziz, A., 2020. Influence of Cereclor on the performance of aged asphalt binder. International Journal of Pavement Engineering 21(11), 1309–1320. [CrossRef]

- Jamal, M. and Giustozzi, F., 2020. Low-content crumb rubber modified bitumen for improving Australian local roads condition. Journal of Cleaner Production 271, 122484. [CrossRef]

- Jia, X., Huang, B., Bowers, B.F., and Zhao, S., 2014. Infrared spectra and rheological properties of asphalt cement containing waste engine oil residues. Construction and Building Materials 50, 683–691. [CrossRef]

- Kamal, M., Khan, K., Hafeez, I., and Kumar, K., 2009. Comparison of CRMB Test Sections with Conventional Pavement Section Under the Same Trafficking and Environmental Conditions. Arabian Journal for Science and.

- Khan, K.M. and Kamal, M.A., 2008. Impact of superpave mix design method on rutting behavior of flexible pavements in Pakistan. University of Engineering and Technology Taxila.

- Kim, H. and Lee, S.-J., 2013. Laboratory Investigation of Different Standards of Phase Separation in Crumb Rubber Modified Asphalt Binders. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 25(12), 1975–1978. [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.H. and Lee, S.J., 2015. Effect of crumb rubber on viscosity of rubberized asphalt binders containing wax additives. Construction and Building Materials 95, 65–73. [CrossRef]

- Kök, B.V., Yilmaz, M., and Geçkil, A., 2013. Evaluation of Low-Temperature and Elastic Properties of Crumb Rubber– and SBS-Modified Bitumen and Mixtures. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 25(2), 257–265. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., Luo, G., Wang, X., and Jiao, Y., 2015. Effects of preparation process on performance of rubber modified asphalt. IOP Conference Series: Materials.

- Liu, S., Meng, H., Xu, Y., and Zhou, S., 2018. Evaluation of rheological characteristics of asphalt modified with waste engine oil (WEO). Petroleum Science and Technology 36(6), 475–480. [CrossRef]

- Liu, S., Peng, A., Zhou, S., Wu, J., Xuan, W., and Liu, W., 2019. Evaluation of the ageing behaviour of waste engine oil-modified asphalt binders. Construction and Building Materials 223, 394–408. [CrossRef]

- Mashaan, N.S. and Karim, M.R., 2014. Waste tyre rubber in asphalt pavement modification. Materials Research Innovations 18, S6-6–S6-9. [CrossRef]

- Masson, J.F., 2008. Brief review of the chemistry of polyphosphoric acid (PPA) and bitumen. Energy and Fuels 22(4), 2637–2640. [CrossRef]

- Mirza, M.W., Abbas, Z., and Rizvi, M.A., 2011. Temperature Zoning of Pakistan for Asphalt Mix Design. Pakistan Journal of Engineering & Applied Science 8, 49–60.

- Mohanty, M., 2013. A Study on Use of Waste Polyethylene in Bituminous Paving Mixes. National Institute of Technology.

- Moraes, R., Velasquez, R., and Bahia, H.U., 2011. Measuring the Effect of Moisture on Asphalt–Aggregate Bond with the Bitumen Bond Strength Test. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2209(1), 70–81. [CrossRef]

- Moreno, F., Sol, M., Martín, J., Pérez, M., and Rubio, M.C., 2013. The effect of crumb rubber modifier on the resistance of asphalt mixes to plastic deformation. Materials and Design 47, 274–280. [CrossRef]

- Navarro, F.J., Partal, P., Martı́nez-Boza, F., and Gallegos, C., 2004. Thermo-rheological behaviour and storage stability of ground tire rubber-modified bitumens. Fuel 83(14–15), 2041–2049.

- Polacco, G., Berlincioni, S., Biondi, D., Stastna, J., and Zanzotto, L., 2005. Asphalt modification with different polyethylene-based polymers. European Polymer Journal 41(12), 2831–2844. [CrossRef]

- Lo Presti, D., 2013. Recycled Tyre Rubber Modified Bitumens for road asphalt mixtures: A literature review. Construction and Building Materials 49, 863–881. [CrossRef]

- Qian, C., Fan, W., Ren, F., Lv, X., and Xing, B., 2019. Influence of polyphosphoric acid (PPA) on properties of crumb rubber (CR) modified asphalt. Construction and Building Materials 227, 117094. [CrossRef]

- Rosado, E.D. and Pichtel, J., 2003. Chemical characterization of fresh, used and weathered motor oil via GC/MS, NMR and FTIR techniques. Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science.

- Rumyantseva, A., Rumyantseva, E., Berezyuk, M., and Plastinina, J., 2020. Waste recycling as an aspect of the transition to a circular economy. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science 534(1), 012002. [CrossRef]

- S.Mashaan, N., Hassan Ali, A., Rehan Karim, M., and Abdelaziz, M., 2011. Effect of blending time and crumb rubber content on properties of crumb rubber modified asphalt binder. International Journal of the Physical Sciences 6((9) (May)), 2189–2193.

- Sandeep, R.G., Ramesh, A., Vijayapuri, V.R., and Ramu, P., 2021. Laboratory evaluation of hard grade bitumen produced with PPA addition. International Journal of Pavement Research and Technology 14(4), 505–512. [CrossRef]

- Shafabakhsh, G.H.G., Sadeghnejad, M., and Sajed, Y., 2014. Case study of rutting performance of HMA modified with waste rubber powder. Case Studies in Construction Materials 1, 69–76. [CrossRef]

- Shoukat, T. and Yoo, P.J., 2018. Rheology of Asphalt Binder Modified with 5W30 Viscosity Grade Waste Engine Oil. Applied Sciences 8(7), 1194. [CrossRef]

- Sienkiewicz, M., Janik, H., Borzędowska-Labuda, K., and Kucińska-Lipka, J., 2017. Environmentally friendly polymer-rubber composites obtained from waste tyres: A review. Journal of Cleaner Production 147, 560–571. [CrossRef]

- Varanda, C., Portugal, I., Ribeiro, J., Silva, A.M.S., and Silva, C.M., 2016. Influence of Polyphosphoric Acid on the Consistency and Composition of Formulated Bitumen: Standard Characterization and NMR Insights. Journal of Analytical Methods in Chemistry 2016. [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, A., Ho, S., and Zanzotto, L., 2008. Asphalt modification with used lubricating oil. Canadian Journal of Civil Engineering 35(2), 148–157. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Dang, Z., You, Z., and Cao, D., 2012. High-Temperature Viscosity Performance of Crumb-Rubber-Modified Binder With Warm Mix Asphalt Additives. Journal of Testing and Evaluation 40(5), 20120064. [CrossRef]

- Wang, H., Liu, X., Apostolidis, P., Erkens, S., and Skarpas, A., 2020. Experimental Investigation of Rubber Swelling in Bitumen. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board 2674(2), 203–212.

- Wang, H., Liu, X., Zhang, H., Apostolidis, P., Scarpas, T., and Erkens, S., 2020. Asphalt-rubber interaction and performance evaluation of rubberised asphalt binders containing non-foaming warm-mix additives. Road Materials and Pavement Design 21(6), 1612–1633. [CrossRef]

- Wang, W., Jia, M., Jiang, W., Lou, B., Jiao, W., Yuan, D., Li, X., and Liu, Z., 2020. High temperature property and modification mechanism of asphalt containing waste engine oil bottom. Construction and Building Materials 261, 119977. [CrossRef]

- Xiao, F., Wenbin Zhao, P.E., and Amirkhanian, S.N., 2009. Fatigue behavior of rubberized asphalt concrete mixtures containing warm asphalt additives. Construction and Building Materials 23(10), 3144–3151. [CrossRef]

- Yadollahi, G. and Sabbagh Mollahosseini, H., 2011. Improving the performance of Crumb Rubber bitumen by means of Poly Phosphoric Acid (PPA) and Vestenamer additives. Construction and Building Materials 25(7), 3108–3116. [CrossRef]

- Yao, H., You, Z., Li, L., Lee, C.H., Wingard, D., Yap, Y.K., Shi, X., and Goh, S.W., 2013. Rheological Properties and Chemical Bonding of Asphalt Modified with Nanosilica. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 25(11), 1619–1630. [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, Y., 2007. Polymer modified asphalt binders. Construction and Building Materials 21(1), 66–72.

- Yu, H., Leng, Z., Zhou, Z., Shih, K., Xiao, F., and Gao, Z., 2017. Optimization of preparation procedure of liquid warm mix additive modified asphalt rubber. Journal of Cleaner Production 141, 336–345. [CrossRef]

- Yu, X., Leng, Z., Wang, Y., and Lin, S., 2014. Characterization of the effect of foaming water content on the performance of foamed crumb rubber modified asphalt. Construction and Building Materials 67(PART B), 279–284. [CrossRef]

- Zając, G., Szyszlak-Bargłowicz, J., Słowik, T., Kuranc, A., and Kamińska, A., 2015. Designation of Chosen Heavy Metals in Used Engine Oils Using the XRF Method. Polish Journal of Environmental Studies 24(5), 2277–2283. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F. and Hu, C., 2013. The research for SBS and SBR compound modified asphalts with polyphosphoric acid and sulfur. Construction and Building Materials 43, 461–468. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J., Birgisson, B., and Kringos, N., 2014. Polymer modification of bitumen: Advances and challenges. European Polymer Journal 54(1), 18–38. [CrossRef]

| Sr. No | Dosage |

| 1 | Control blend (B) |

| 2 | B+5% WEO+20% CB |

| 3 | B+5% WEO+25% CB |

| 4 | B+5% WEO+30% CB |

| 5 | B+10% WEO+20% CB |

| 6 | B+10% WEO+25% CB |

| 7 | B+10% WEO+30% CB |

| 8 | B+15% WEO+20% CB |

| 9 | B+15% WEO+25% CB |

| 10 | B+15% WEO+30% CB |

| 11 | B+5% WEO+30% CB+0.6%PPA |

| 12 | B+5% WEO+30% CB+1.2%PPA |

| 13 | B+5% WEO+30% CB+1.8%PPA |

| Statistical Analysis of Viscosity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additives | N | Subset at 95% confidence interval | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| B+15%WEO+20%CR | 3 | 138.2 | |||||

| B+15%WEO+25%CR | 3 | 166.9 | |||||

| B+15%WEO+30%CR | 3 | 174.6 | |||||

| B+10%WEO+20%CR | 3 | 189.2 | |||||

| B+10%WEO+25%CR | 3 | 211.6 | |||||

| B+10%WEO+30%CR | 3 | 248.5 | |||||

| Sig. | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| Additives | N | Subset at 95% confidence interval | |||||

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | ||

| B+5%WEO+20%CR | 3 | 263 | |||||

| B+5%WEO+25%CR | 3 | 268.5 | |||||

| B+5%WEO+30%CR | 3 | 274.7 | |||||

| B+5% WEO+30 % CR+0.6%PPA | 3 | 284 | |||||

| B+5% WEO+30 % CR+1.2%PPA | 3 | 292 | |||||

| Virgin Binder | 3 | 294.7 | |||||

| B+5% WEO+30 % CR+1.8%PPA | 3 | 299 | |||||

| Sig. | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| Statistical Analysis of Complex Modulus | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additives | N | Subset at 95% confidence interval | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| B+15%WEO+20%CR | 3 | 147.65 | |||||

| B+15%WEO+25%CR | 3 | 167.34 | |||||

| B+10%WEO+20%CR | 3 | 189.47 | |||||

| B+15%WEO+30%CR | 3 | 191.95 | |||||

| B+5%WEO+20%CR | 3 | 207.96 | |||||

| B+10%WEO+25%CR | 3 | 218.87 | |||||

| B+5%WEO+25%CR | 3 | 246.41 | |||||

| Sig. | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Additives | N | Subset at 95% confidence interval | |||||

| 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | ||

| B+10%WEO+30%CR | 3 | 283.65 | |||||

| B+5%WEO+30%CR | 3 | 317.76 | |||||

| Virgin Binder | 3 | 353.72 | |||||

| B+5% WEO+30 % CR+0.6%PPA | 3 | 787.36 | |||||

| B+5% WEO+30 % CR+1.2%PPA | 3 | 1130.91 | |||||

| B+5% WEO+30 % CR+1.8%PPA | 3 | 2170.85 | |||||

| Sig. | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |

| Statistical Analysis of Moisture Susceptibility | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Additives | N | Subset at 95% confidence interval | ||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | ||

| B+15%WEO+20%CR | 3 | 1.3 | ||||

| B+10%WEO+20%CR | 3 | 1.57 | ||||

| B+15%WEO+25%CR | 3 | 1.775 | ||||

| B+10%WEO+25%CR | 3 | 2.180 | ||||

| B+15%WEO+30%CR | 3 | 2.305 | 2.305 | |||

| B+5%WEO+20%CR | 3 | 2.423 | ||||

| Sig. | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |

| Additives | N | Subset at 95% confidence interval | ||||

| 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |||

| B+10%WEO+30%CR | 3 | 2.64 | ||||

| B+5%WEO+25%CR | 3 | 2.83 | ||||

| B+5%WEO+30%CR | 3 | 3.305 | ||||

| B+5% WEO+30 % CR+0.6%PPA | 3 | 3.445 | 3.445 | |||

| B+5% WEO+30 % CR+1.2%PPA | 3 | 3.622 | 3.620 | |||

| Virgin Binder | 3 | 3.70 | ||||

| B+5% WEO+30 % CR+1.8%PPA | 3 | 3.80 | ||||

| Sig. | 0.079 | 0.444 | 0.144 | 0.119 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).