1. Introduction

As previously reported, mutations of TBCK could abolish the normal function of TBCK via generating truncated TBCK protein and further developing neurogenetic disorders [

1]. Among which, a famous “Boricua mutation” p.R126X is associated with a more severe version of the disorder called TBCK-related encephalopathy [

2,

3,

4,

5]. TBCK-related encephalopathy is a rare autosomal recessive neurogenetic disorder (around 35 reported cases worldwide) with major clinical symptoms of hypotonia (low muscle tone), epilepsy, and intellectual disability [

6].

Besides, TBCK was also proved to be associated with cancer progression. The earliest report in 2010 suggested that MGC16169 (TBCK) selectively supports coupling of active EGFR to ERK1/2 regulation in A431 cells. In addition, elevated pStat3 were also observed in A431 cells while MGC16169 (TBCK) was knocked down, suggesting the involvement of MGC16169 (TBCK) in STAT3 signaling pathway [

7]. In 2013, TBCK was reported to be involved in the regulation of cell proliferation, cell growth and actin organization probably via modulating mTOR pathway in HEK293 cells [

8]. Our group also demonstrated that two types of alternatively spliced TBCK were detected in multiple cell lines, including HEK293 and A431, long type of TBCK might perform tumor growth suppressing function [

9]. In 2016, Ioannis Panagopoulos et al. presented a case with fusion transcripts (in-frame TBCK-P4HA2 and out-of-frame P4HA2-TBCK) in a soft tissue angiofibroma [

10]. Eun-Ae Kim et al. in 2019 reported that the miR-1208 could target 3’UTR of TBCK and decrease TBCK’s expression, which would enhance the sensitivity to the treatment of cisplatin or TRAIL in renal cancer cells [

11]. In a recent paper published in 2021, frameshift insertion mutation of TBCK was found in 95% of plasma Samples from Hepatocellular Carcinoma patients, suggesting the suppression function of TBCK in HCC [

12].

Based on above description, TBCK indeed participated in multiple activities. However, the detail mechanisms regarding TBCK’s functions are still underexplored. Even though the first functional study related to TBCK utilized RNAi technique to knockdown TBCK [

7], it lacked protein evidence. Besides, RNA interference strategy has some limitations. To overcome these shortcomings and further explore TBCK’s functions, we introduced a CRISPR-mediated Knockout system to deplete TBCK in multiple human cell models. Moreover, hallmark pathway and gene ontology analysis for RNA-seq data against TBCK knockout uncovered positive roles of TBCK in multiple cancer-related pathways, such as TNF-α signaling, Apoptosis, Hypoxia, P53, and Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition. Last but not the least, we provide a detailed and straightforward protocol for mediating TBCK depletion, which can be easily applied for any other genes, especially for the beginners who started to touch gene knockout field.

3. Results

3.1. Design of sgRNAs Targeted to the TBCK Gene

A well-designed single-guide RNA (sgRNA) determines the overall performance of CRISPR/Cas system. Around 20 bioinformatic tools have been created for designing efficient and specific sgRNA for candidate genes [

25], such as CRISPR.mit [

26] and sgRNA designer [

27,

28]. Due to the design specifications, parameters and other aspects, the on-target efficiency and off-target effects for each tool were different [

27]. To induce efficient knockout of the human TBCK gene, different TBCK-targeting sgRNAs were designed. The TBCK gene consists of 26 exons alternatively spliced to produce 9 TBCK isoforms [

1,

9], which might perform distinctive roles. Four sgRNA oligos against TBCK with an acceptable On-Target Efficacy Score were selected using online sgRNA designer tool (now called CRISPick,

Table 1) together with Human CRISPR Knockout Pooled Library [

29] to determine two sets of sgRNA (

Table 2). Besides, A non-targeting control sgRNA (two oligos) was setup as previously reported (

Table 1) [

30]. All six oligos were sent out for synthesis for the following vector construction and applications (

Figure 1).

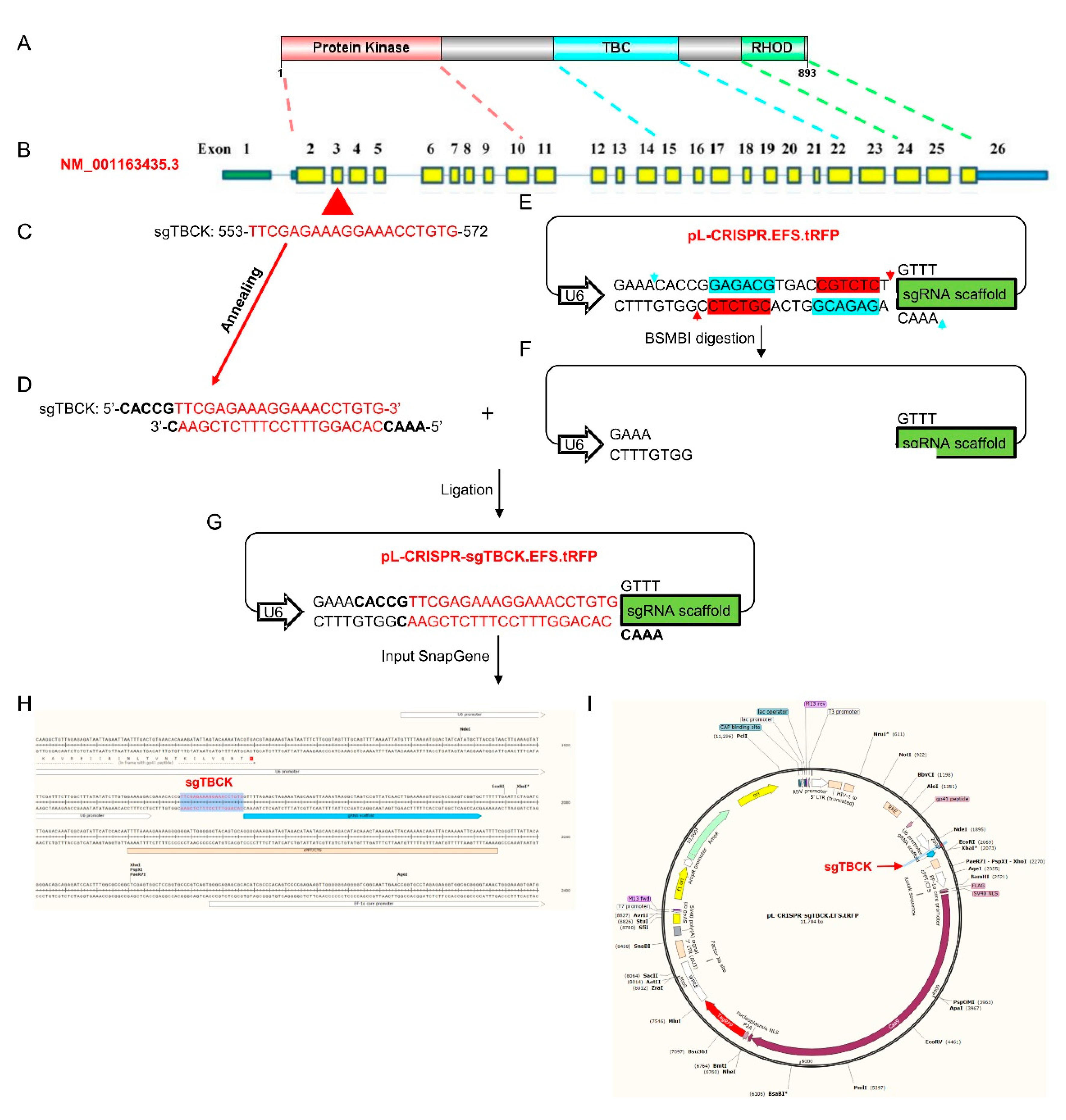

3.2. TBCK Knockout Vector Construction

The major steps for lentivector construction include Lentiviral vector digestion, oligo annealing, ligation, transformation, single positive clone screening by PCR and validation by Sanger sequencing (

Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram for knocking out human

TBCK via a CRISPR-Cas9 system. A. A diagram of TBCK including known domains. B.

Schematic representation of full-length TBCK (NM_001163435.3); the 5’ UTR and

3’ UTR are shown as green and blue bars respectively. Separated by introns

shown by blue lines, exons are indicated by solid rectangles with yellow. C.

sgTBCK sequence (553-572) mapping to exon 3. D. The ↓↓ annealing output for oligo 3 and 4 (sgT3). E.

pL-CRISPR.EFS.tRFP vector including BSMBI recognition sequences (5’-CGCCTCN1

-3’ and 3’-GCAGAGN5 -5’). Blue and red arrows represent the cutting sites. F. BSMBI digested product. G. Ligating sgTBCK into pL-CRISPR.EFS.tRFP vector. H-I. Reconstruction the vector map for pL-CRISPR.sgTBCK.tRFP.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram for knocking out human

TBCK via a CRISPR-Cas9 system. A. A diagram of TBCK including known domains. B.

Schematic representation of full-length TBCK (NM_001163435.3); the 5’ UTR and

3’ UTR are shown as green and blue bars respectively. Separated by introns

shown by blue lines, exons are indicated by solid rectangles with yellow. C.

sgTBCK sequence (553-572) mapping to exon 3. D. The ↓↓ annealing output for oligo 3 and 4 (sgT3). E.

pL-CRISPR.EFS.tRFP vector including BSMBI recognition sequences (5’-CGCCTCN1

-3’ and 3’-GCAGAGN5 -5’). Blue and red arrows represent the cutting sites. F. BSMBI digested product. G. Ligating sgTBCK into pL-CRISPR.EFS.tRFP vector. H-I. Reconstruction the vector map for pL-CRISPR.sgTBCK.tRFP.

Detailed information can be found below:

1. Digest and dephosphorylate 5ug of the lentiviral plasmid pL-CRISPR.EFS.tRFP with BsmBI enzyme for 30 min at 37C:

5 ug pL-CRISPR.EFS.tRFP (Addgene)

3 ul FastDigest BsmBI (Fermentas)

3 ul FastAP (Fermentas)

6 ul 10X FastDigest Buffer

0.6 ul 100 mM DTT (freshly prepared)

X ul ddH2O

60 ul total

2. Gel purify digested plasmid using QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit and elute in EB. If BsmBI digested, a ~2kb filler piece should be present on the gel. Only gel purify the larger band. Leave the 2kb band.

3. Phosphorylate and anneal each pair of oligos:

1 ul Oligo 1 (100 μM)

1 ul Oligo 2 (100 μM)

2 ul 5X T4 Ligation Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific)

5.5 ul ddH2O

0.5 ul T4 PNK (NEB)

10 ul total

Put the phosphorylation/annealing reaction in a thermocycler using the following parameters:

37C 30 min

95C 5 min and then ramp down to 25C at 5C/min

4. Dilute annealed oligos from Step 3 at a 1:200 dilution into sterile water or EB.

5. Set up ligation reaction and incubate at room temperature for 10 min:

1 ul BsmBI digested pL-CRISPR.EFS.tRFP from Step 2 (50ng)

1 ul diluted oligo duplex from Step 4

2 ul 5XT4 DNA Ligase Buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific)

5 ul ddH2O

1 ul T4 DNA Ligase (Thermo Fisher Scientific)

10 ul total

Also perform a negative control ligation (vector-only with water in place of oligos) and transformation.

6. Transformation into Stbl3 bacteria cells.

Lentiviral transfer plasmids contain Long-Terminal Repeats (LTRs) and must be transformed into recombination-deficient bacteria cells (Such as Stbl3).

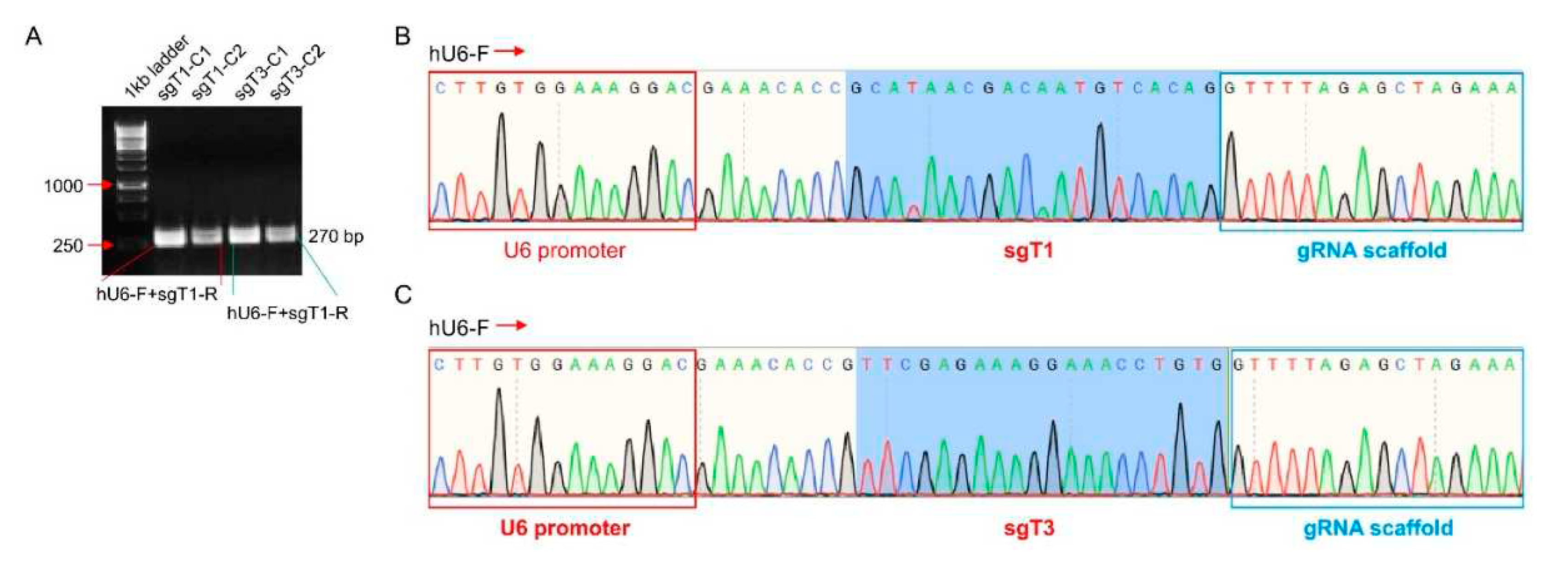

7. Screening positive bacterial clones for pL-CRISPR.EFS.tRFP with double-stranded oligo inserts:

Run a bacteria liquid PCR for 2-4 colonies per transformed vector (2 colonies should always be enough as this procedure should have 90-100% efficiency). For current study, 2 clones were used as templates to perform Bacteria PCR using hU6-F (5'-GAGGGCCTATTTCCCATGATT-3') and reverse Primers (10 uM of oligo 2 (sgTBCK-1) and oligo 4 (sgTBCK-3) and positive clones should generate a band with predicted size of 270bp. Indeed, all four clones against sgTBCK-1 or sgTBCK-3 generated the expected PCR products (

Figure 3A). Further sanger sequencing using hU6-F primer proved that all four clones included intact sgRNA, partial upstream U6 and downstream gRNA scaffold sequences, indicating 100% of transformation rate for the vector construction (

Figure 3B). pL-CRISPR.EFS.tRFP-sgTBCK-1-C1 (sgT1) and pL-CRISPR.EFS.tRFP-sgTBCK-3-C1 (sgT3) were selected for the following Midipreps and other applications.

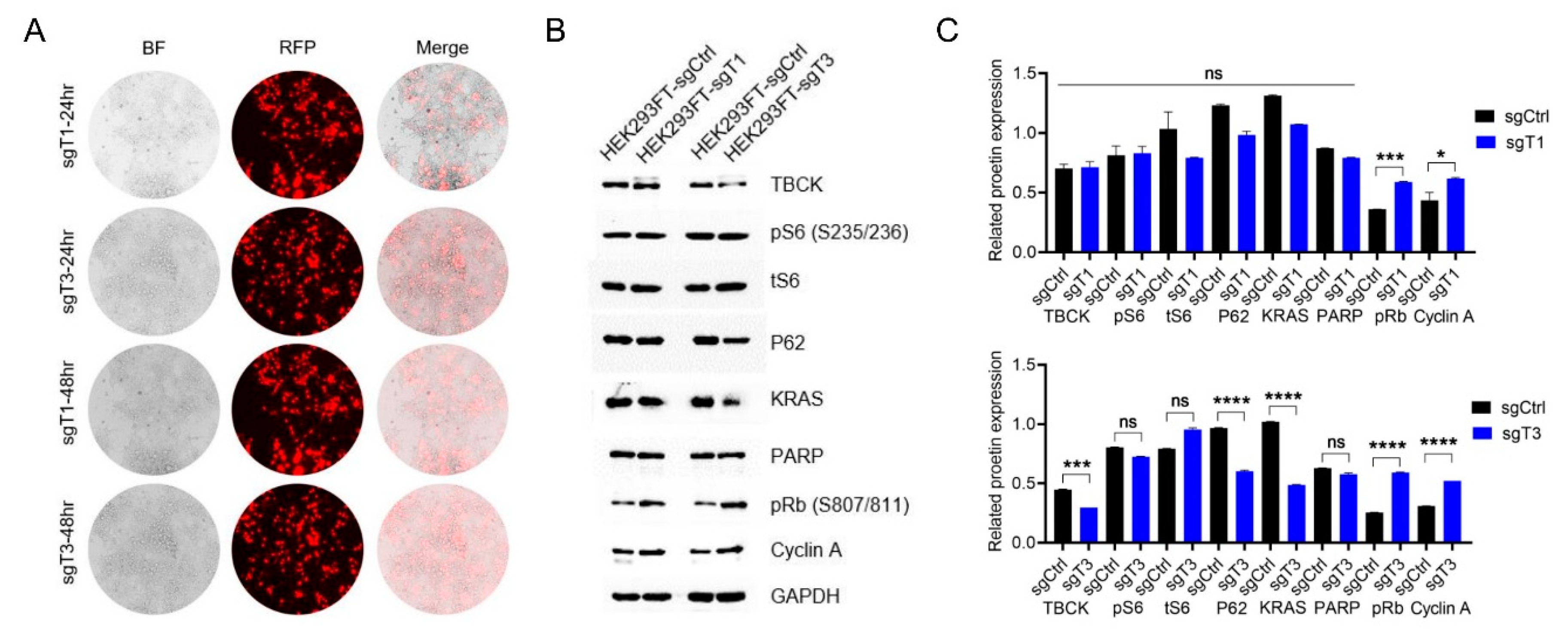

3.3. Knockout Efficiency of TBCK in HEK293FT Cells

Above results showed that we were able to successfully obtain positive TBCK-Knockout vectors, however, we still did not know whether the sgRNAs could edit TBCK gDNA or not. Next, we did a transient transfection for either sgCtrl or sgTBCKs (sgT1-C1 and sgT3-C1) plasmids into HEK293FT cells. As shown in

Figure 4A, the indicator RFP represents the overall transfection efficiency. Even though sgT1 group has compatible transfection efficiency as sgT3, it has little effects on expression of target TBCK and downstream effectors (

Figure 4B,C). While sgT3 can deplete around 50% of TBCK, P62 and Kras and promote around 200% expression of pRB and cyclin A. Hence, sgT3 was selected for the following applications.

3.4. Lentivirus Preparation and Target Cell Infection

Next, we prepared packaging vector psPAX2, envelop vector PMD2.G and transfer vector pL-CRISPR. sgT3.tRFP vector to make Lentivirus (

Figure 5A). Briefly, on day 1, split HEK293FT cells into 1*10cm plate (either for sgT3 or sgCtrl) to make sure the confluency can reach up to 80% before transfection (around 24hr). On day 2, change with 5ml fresh DMEM medium, then, making 0.5ml transfection reaction mixture (including packaging vector, transfer vector and Envelop vector) and transfected the packaging cells HEK293FT. On day 3, change with 10ml fresh DMEM medium and allow mature lentivirus generation for extra 24hr. On day 4, collect the mature lentiviral vector supernatants post-transfection for 48hr. On this step, we can aliquot total of 10ml lentiviral vector supernatants into 10 cryogenic vials (1ml/vial) for direct infection (

Figure 5B). Or we can use PEG-it Virus Precipitation Solution to concentrate lentivirus particles. Finally, the collected lentivirus can be applied for target cell infection. Herein, we utilized sgT3 lentivirus to infect multiple human and mouse cell models (

Table 3).

Figure 5.

Lentivirus preparation. A. Detailed protocol to make lentivirus for sgCtrl and sgT3. B. Schematic for lentivector packaging and transduction. The process of producing infectious transgenic lentivirus included co-transfection of 3 plasmids (packaging plasmid psPAX2 + envelope plasmid PMD2.G + transfer plasmid pL-CRISPR.sgCtrl.tRFP or pL-CRISPR.sgT3.tRFP) are transfected into HEK293FT cells. After media change and a brief incubation period, supernatant containing the virus is removed and stored or centrifuged to concentrate virus. Crude or concentrated virus can then be used to transduce the cells of interest. .

Figure 5.

Lentivirus preparation. A. Detailed protocol to make lentivirus for sgCtrl and sgT3. B. Schematic for lentivector packaging and transduction. The process of producing infectious transgenic lentivirus included co-transfection of 3 plasmids (packaging plasmid psPAX2 + envelope plasmid PMD2.G + transfer plasmid pL-CRISPR.sgCtrl.tRFP or pL-CRISPR.sgT3.tRFP) are transfected into HEK293FT cells. After media change and a brief incubation period, supernatant containing the virus is removed and stored or centrifuged to concentrate virus. Crude or concentrated virus can then be used to transduce the cells of interest. .

3.5. Single Cell Clone Selection and Validation in MIA PaCa-2 Cell Model

We first utilized sgCtrl and sgT3 lentivirus to infect PDAC MIA PaCa-2 (marked with H2B-GFP) cells. To obtain better infection efficiency, we infected target cells twice. Then, we digested and split 100 cells into 1*96-well plate for single clone selection. Two weeks later, we transferred 12 single clones from 96-well plate to 24 well plate. WB analysis further confirmed that sgT3 showed around 58.3% knock-out efficiency (7/12) in MIA PaCa-2 cell model (

Figure 6A). Besides, observation from fluorescent microscope indicated that selected clones in both sgCtrl and sgT3 (sgT3-C2/C6/C11) groups had plenty of lentivirus particles because RFP signals can be captured in almost each cell (

Figure 6B). To further uncover the variation patterns caused by CRISPR-mediated gene editing, we designed a primer set located intron 2 and intron 3 to cover sgT3 in exon 3. PCR results showed that sgCtrl cells only generated one single band (461bp), while sgT3 cells either generated on single band (C2) or two bands (C6/C11) (

Figure 6C). Further sanger sequencing analysis demonstrated that no mutations were found in sgCtrl cells, while T insertion was verified in all 3 clones of sgT3 cells (

Figure 6D and Figure S1A), as well as the whole exon 3 and portion of intron 2 were missing (

Figure 6E and Figure S2A). Sequence alignment based on DNA variations mediated by sgT3 showed that T insertion potentially changed the open reading frame (ORF) of TBCK and generated truncated TBCK products: Truncated TBCK-A (98aa) and Truncated TBCK-B (787aa) (

Figure 6F and Figure S1B), while exon 3 skipping would not alter the ORF but generate a shorter TBCK product: Truncated TBCK-C (869aa) (

Figure 6F and Figure S2B,C>). Considering the immunogen sequence for TBCK antibody (HPA039951) located at C terminal of TBCK, truncated TBCK-A couldn’t be recognized, while truncated TBCK-B and Truncated TBCK-C could possibly be detected. However, we could only detect one clear single band for full-length TBCK in sgCtrl cells, but not truncated products (

Figure 6G), which needs further investigation. One possible reason is that these abnormal products are not stable and might be degraded quickly. Taken together, sgT3 can efficiently edit TBCK gDNA and introduce a T insertion or Exon 3 skipping to block normal Full-length TBCK expression.

3.6. The Knockout Vector Can Be Applied in Fibrosarcoma HT1080 Cell Model

To further confirm the efficacy of sgT3 for TBCK Knockout in other human cell models, we also used the virus to infect Fibrosarcoma HT1080 cell model. As depicted in MIA PaCa-2 cell model, the same strategy was performed and finally 4 single cell clones were picked up for immunoblot analysis (

Figure 7A). The knockout efficiency was not that great as MIA PaCa-2 model, only 25% for HT1080 cells. Nevertheless, PCR amplification generate a single clear PCR product for either sgCtrl or sgT3 group, which is similar as sgT3-C2 in MIA PaCa-2 cell (

Figure 7B). Sanger sequencing further confirmed that CRISPR-mediated gene editing in HT1080 cell model also introduced a T insertion in the same site as MIA PaCa-2 (

Figure 7C), which suggest a similar mechanism for deleting TBCK expression. More clones needed to be selected for confirming the preference sequence for editing.

3.7. The Human Specific sgRNA against TBCK Showed Little Effects on Mouse Cells

After confirming the great effects of sgT3 on human cell models, we are eager to know whether the sgT3 can also be applied on mouse cells. Firstly, we check the sequence similarity between human and mouse TBCKs and found a two-base mismatch in sgRNA region (

Figure 8A). Initially, we assumed that two-base mismatch would have no or little effects on editing efficiency. We infected KPC3 mouse cells with sgCtrl or sgT3 lentivirus and screened single cell clones as human cell models. Finally, we selected four clones with high RFP signals (

Figure 8B), representing plenty of lentivirus particles in cells. However, little effects on TBCK expression were observed by immunoblot analysis (

Figure 8C). Consistent with this, PCR using a primer set located intron 2 and intron 3 of mouse Tbck generated a clear single band for 5 clones infected with either sgCtrl or sgT3 lentivirus (

Figure 8D). Further sanger sequencing analysis supported that no mutations were found in sgRNA region for all five clones (

Figure 8E and Figure S3). Although double peaks occurred downstream sgRNA region for clones 3/6/9 (

Figure 8E), even one base mutation (G to A) for clones 3/9, the variations in intron 3 had no effects on protein expression (Figure S3). Taking together, we believed that sgT3 can efficiently infected mouse cells, but had little effects on TBCK expression mainly due to 2-base mismatch.

3.8. RNA-seq Application for TBCK Knockout Single Clone in PDAC Model

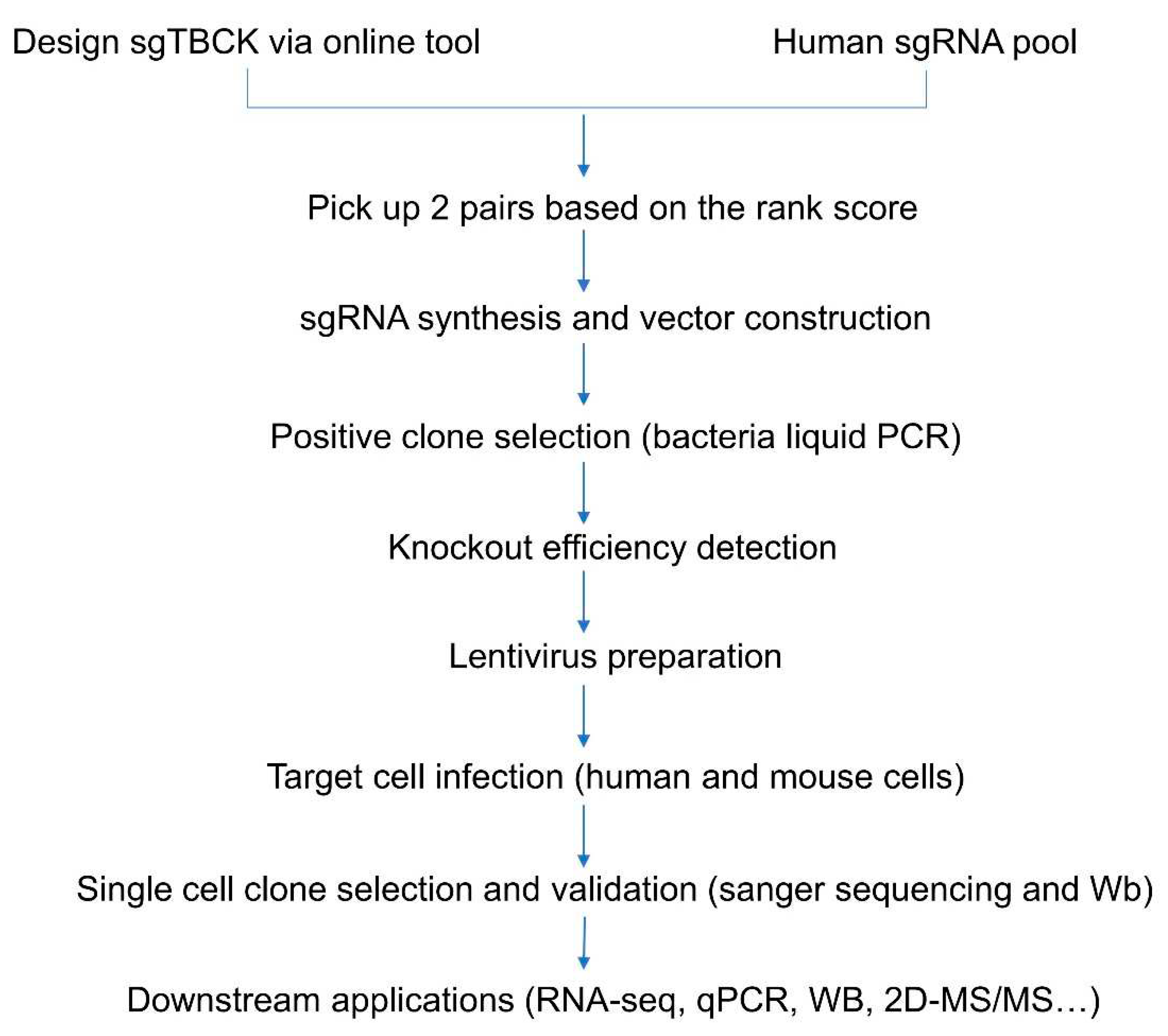

Based on the overall workflow for TBCK knockout system shown in

Figure 1, we performed transcriptome analysis for MIA PaCa-2 cells infected with sgCtrl or sgT3 lentivirus. As shown in

Figure 9A, triplicated samples for transcriptome analysis in either sgCtrl or sgT3 group looked great, because TBCK protein level was completely depleted after stable infection of sgT3-C6 lentivirus. Bioinformatic analysis revealed that TBCK knockout elicited both 314 significantly downregulated genes (Table S1) and induced 184 significantly downregulated genes (

Figure 9B, Table S2). Pathway analysis using hallmark genesets in the Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) for downregulated DEGs revealed a significant enrichment on pathways including TNF-α signaling, Apoptosis, Hypoxia, P53, and Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition (

Figure 9C), confirming essential roles of TBCK in cancer progression. Similar analysis for the upregulated DEGs uncovers a high enrichment on interferon gamma response and immune related pathways (

Figure 9D). This signature of immune response is consistent with previously report in A431 model that siRNA mediated TBCK knockdown activated STAT3 pathway [

7], as well as our previous data regarding RNAi-mediated TBCK knockdown in HeLa cell model (Figure S4). Five selected genes for each enriched pathway were illustrated by the heatmap shown in

Figure 9E. Remarkably, GSEA analysis also uncovered the similar enriched pathways for both downregulated and upregulated DEGs (Figure S5A,B), even though the enrichment p valve for upregulated DEGs was not that great. For more details, we extracted 3 enriched plots for either downregulate or upregulated DEGs (

Figure 9F). The triplicated expressions of selected DEGs, such as IL18, CCND2, HLA-DOA1 and PDK1, were significantly downregulated or upregulated MIA PaCa-2-sgTBCK cells (

Figure 9G).

Except for hallmark pathway analysis, we also performed Gene Ontology analysis regarding the downregulated or upregulated DEGs. The downregulated DEGs were mainly enriched in Negative regulation of phosphorylation (GO: 0042326), Negative regulation of cell growth (GO: 0030308), and Collagen-containing extracellular matrix (GO: 0062023) (

Figure 10A,B). The upregulated DEGs were largely enriched in Antigen processing and presentation (GO: 0002495) and Golgi apparatus subcompartment (GO: 0098791) (

Figure 10C,D). Even though our previous research mentioned that TBCK protein included STYKc kinase domain, TBC domain and RHOD domain [

1,

9], other reports suggested TBCK as a pseudokinase because of lacking conserved motif for kinase activity [

8,

31,

32]. Our transcriptome analysis indicated a positive role of TBCK in regulation protein phosphorylation, which encouraging us to perform further investigation regarding kinase function of TBCK. Other interesting parts also included the roles of TBCK in antigen processing and presentation, tumor microenvironment and Golgi apparatus assemble. Confirming the real functions of TBCK in these activities will largely fill in the implementation gaps for the underexplored TBCK protein.

Finally, to further analyze the potential relationship between TBCK and the DEGs, we initially input TBCK and all DEGs into online STRING database. Unexpectedly, only one connection was found. Then we reloaded TBCK and upregulated or downregulated DEGs separately and found that no connections were observed between TBCK and upregulated DEGs (

Figure 10E), while the connection between TBCK and PLXNB2 in downregulated DEG list was clearly shown (

Figure 10F–H). PLXNB2 was reported to bind Class IV Semaphorins involving in brain development, actin cytoskeleton organization and cell migration [

33,

34]. Indeed, several Semaphorin members, such as SEMA3C/3F/4B/4D/6B, were also found in downregulated gene list (

Figure 10F–H). The relationship between TBCK and PLXNB2 might pave a way for dissecting a novel mechanistic role of TBCK in neurodevelopment diseases beyond affecting mTOR signaling pathway [

2,

3,

4]. Interestingly, consistent with Gene Ontology analysis, even though no connections were observed in upregulated DEG list, the upregulated immune molecular prefer to be enriched in MHCII (

Figure 10E), indicating the inhibition roles of TBCK in MHCII related pathways.

4. Discussion

It has been 13 years since the first functional study associated with TBCK was reported in 2010. TBCK might play important roles in neurodevelopment and cancer progression. Encouraging progress has been achieved regarding the close relationship between TBCK mutation and neurodevelopment disease during the past 5 years. Homozygous or compound heterozygous variants in TBCK lead to an intellectual impairment phenotype with hypotonia and characteristic facies type 3 (IHPRF3; OMIM: 616900) [

2,

3,

35]. Downstream TBCK mediated inhibition of mTOR can alter autophagy of oligosaccharides, demonstrated by significantly reduced lysosomal proteolytic function in TBCK-deficient fibroblasts. Except for the important contribution of TBCK to the development of epidermoid carcinoma [

7] and cervical carcinoma [

9], the cancer related studies of TBCK had spread soft tissue angiofibroma [

10], Clear cell Carcinoma [

11] and Hepatocellular Carcinoma [

12]. However, the detailed mechanism for TBCK’s roles in neurodevelopment and cancer research is yet to be elucidated. In current study, we combined CRISPR-mediated knockout system and transcriptome analysis to dissect the direct roles of TBCK in Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma.

CRISPR-Cas9–based genetic screens are a powerful tool for manipulating the genome [

36,

37,

38,

39]. The following studies revealed that sgRNA sequence and experimental conditions determined Cas9 off-target activity [

40,

41,

42,

43,

44]. Around 20 bioinformatic tools have been created for designing efficient and specific sgRNA for candidate [

25]. Due to the design specifications, parameters and other aspects, the on-target efficiency and off-target effects for each tool were different. To increase the rigor and efficiency of our knockout system, we utilized both sgRNA designer to design designed 100 sgRNAs and the Human CRISPR Knockout Library to screen the best two sgRNAs based on On-Target Efficacy Score (

Table 1). One of the main goals for our group was to create a clear and straightforward workflow (

Figure 1) with a detailed schematic diagram (

Figure 2), that makes this knockout system easy to follow. This strategy is not limited to TBCK and can be used on any gene of interest. After confirming the correct sequence for both TBCK knockout vectors (

Figure 3), we performed transient transfection and immunoblot to confirm that sgT3 showed acceptable knockout efficiency, while sgT1 had no effects on TBCK depletion (

Figure 4). Interestingly, TBCK depletion decreased the expression of P62 and Kras, indicating the positive roles of TBCK in mTOR and Kras signaling pathways. sgT3 was selected for further lentivirus preparation and target cell infection (

Figure 5). We first validated the knockout efficiency of TBCK in PDAC MIA PaCa-2 model. Sanger sequencing for selected single clones proved that sgT3 can efficiently edit TBCK gDNA and introduce a T insertion to generate a truncated product and further blocking normal Full-length TBCK expression (

Figure 6). Besides, T insertion or exon 3 skipping might generate shorter protein products, but we could not detect them possibly due to weak stability of these products. Interestingly, CRISPR-mediated gene editing in HT1080 models also introduced T insertion in the same site as MIA PaCa-2 (

Figure 7), which would show the similar mechanism for deleting TBCK expression. Considering the sequence similarity between human and mouse mRNA, we assumed the human sgTBCK could also be applied for mouse cells, however, even though plenty of RFP signals were observed for selected single cell clones, little or no effects on reducing TBCK protein level were supported by immunoblotting and sanger sequencing assays (

Figure 8), which indicated 2bp mismatch largely blocked the cut efficiency of CRISPR-CAS9 system and mouse specific sgRNAs needed to be designed for depleting mouse TBCK protein.

Finally, we performed RNA-seq using MIA PaCa-2 cells stably infected sgCtrl or sgTBCK lentivirus as a downstream application. Unexpectedly, Hallmark pathway analysis uncovers amazing enrichment on several important cancer related pathways, such as TNF-alpha, Apoptosis, Hypoxia, P53, EMT, interferon gamma, metabolism and MTORC1 (

Figure 9). Previous research has highlighted the important roles of mTOR pathway in neurodevelopment diseases and cancer progression. Our new discoveries will provide more choices, especially for cancer related studies. Besides, GO analysis suggests the involvement of TBCK in regulation of protein phosphorylation, cell growth and extracellular matrix. All these parts also looked great. Based on bioinformatic analysis, TBCK is considered a pseudokinase as its kinase domain lacks several important motifs that regulate kinase activity. For instance, the GXGXXG and VAIK motifs for ATP binding, and the HRD motif for catalytic activity, are absent in TBCK [

8]. Although bioinformatic assays have shown this to be true, there have been no functional assays to confirm this and TBCK may still possess some weak kinase activity. Similarly, depletion of TBCK may affect other protein kinases suggesting a possible regulatory role for this pseudokinase. The enrichment of cell growth for downregulated DEGs suggested the positive roles in cell growth in MIA PaCa-2 cells, which is consistent with previous reports in other models [

8,

11]. Extracellular matrix pathways were significantly downregulated suggesting that depletion of TBCK may affect the tumor microenvironment. Upregulation of cell antigen processing and presentation in the Golgi apparatus sub-compartment that accompanies TBCK depletion may be a novel mechanism for PDAC progression. Besides, we found only one connection between TBCK and PLXNB2 in downregulated DEGs list, as well as multiple PLXNB2 associated proteins, such as Semaphorin family members (SEMA3C, SEMA3F, SEMA4B, SEMA4D, SEMA6B), RET and NRP1 (

Figure 10F–H). Semaphorins are a large family of transmembrane (including GPI-anchored) or secreted proteins that were originally identified as indispensable regulators of neuron-axonal guidance [

45], which suggest an important contribution of TBCK to Brain development. Beyond the guidance, Semaphorins also function in a broad spectrum of pathophysiological conditions, including atherosclerosis, a vascular inflammatory disease [

46]. The essential Receptor tyrosine-protein kinase RET was found to be closely related to PLXNB2 [

47,

48] and downregulated in TBCK knockout cells (

Figure 10F–H). The cell-surface receptor NRP1 is involved in the development of the cardiovascular system, angiogenesis, formation of certain neuronal circuits, and in organogenesis outside the nervous system [

49,

50,

51]. TBCK’s important role in developmental pathways, as well as in cancer-related pathways, emphasizes the importance of performing further functional assays to better elucidate its role in disease pathogenesis. While our results are a novel discovery for TBCK's involvement in multiple cancer-related pathways, further work needs to be done to better understand the functional role that TBCK plays within these pathways.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we drafted a clear and straightforward workflow, detailed protocol, and schematic diagram for knocking out human TBCK via a CRISPR-Cas9 system. We also provided evidence showing the effectiveness of sgTBCK in multiple human cancer models. The application of our CRISPR knockout system for transcriptome analysis is the first high throughput screen that looked at TBCK's role in cancer development. Specifically, our results show TBCK's involvement in multiple cancer-related pathways, such as, TNF-α signaling, Apoptosis, Hypoxia, P53, and Epithelial Mesenchymal Transition.

Supplemental Information: Supplemental data include 5 figures and two tables.

Authors Contributions: J.W and G.L conceived the project, wrote, and revised the manuscript. J.Z, J.C and X.Z did bioinformatic analysis and revised the manuscript. J.W performed the functional experiments. A.D and J.J participated in discussion and manuscript revisions. J.W and G.L were corresponding authors. All authors critically revised the article for important intellectual content.

Consent for Publication: All authors have contributed signifcantly, and all authors agree with the manuscript’s content.

Funding: This work was supported by Key Research and Development Project of Deyang City’s Science and Technology Bureau (2021SZ003), Special Fund for Incubation Projects of Deyang People's Hospital (FHG202004), Natural Science Foundation of Sichuan Province (2022NSFSC0714, 2023NSFSC0601) and Xinglin Scholar Project of Chendu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (YYZX2022058).

Declarations Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate: Not applicable.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments: The author thanks all members of the laboratory group and colleagues in the discussion and preparation of the manuscript. Especially for Tonny Wu’s assistance in drawing the pictures for lentivirus preparation in

Figure 5B.

Competing Interests: There were no competing interests among the authors and fundings.

Figure 1.

Workflow for constructing TBCK knockout system.

Figure 1.

Workflow for constructing TBCK knockout system.

Figure 3.

Validation of sgTBCK lentivirus vectors by Bacteria PCR and sanger sequencing. A. Bacteria liquid PCR using hU6 forward primer and sgT1 or sgT3 reverse primer to screen positive clones for pL-CRISPR.sgT1.tRFP or pL-CRISPR.sgT3.tRFP vector. All four clones generated expected PCR products of 270bp. Sanger sequencing using hU6 forward primer for pL-CRISPR.sgT1-C1.tRFP (B) or pL-CRISPR.sgT3-C1.tRFP (C) confirmed partial U6 promoter sequences (red rectangle), gRNA scaffold sequences (blue rectangle) and sgT1 or sgT3 sequences.

Figure 3.

Validation of sgTBCK lentivirus vectors by Bacteria PCR and sanger sequencing. A. Bacteria liquid PCR using hU6 forward primer and sgT1 or sgT3 reverse primer to screen positive clones for pL-CRISPR.sgT1.tRFP or pL-CRISPR.sgT3.tRFP vector. All four clones generated expected PCR products of 270bp. Sanger sequencing using hU6 forward primer for pL-CRISPR.sgT1-C1.tRFP (B) or pL-CRISPR.sgT3-C1.tRFP (C) confirmed partial U6 promoter sequences (red rectangle), gRNA scaffold sequences (blue rectangle) and sgT1 or sgT3 sequences.

Figure 4.

Knockout efficiency detection in HEK293FT cells. A. pL-CRISPR.sgT1-C1.tRFP or pL-CRISPR.sgT3-C1.tRFP plasmid was transiently transfected into HEK293FT cells to check the knockout efficiency for either sgT1 or sgT3. RFP signals indicated the transfection efficiency. B. WB analysis for TBCK and TBCK related proteins. C. Normalized protein levels of TBCK and related proteins based on the gray value (calculated by Image J) for each target.

Figure 4.

Knockout efficiency detection in HEK293FT cells. A. pL-CRISPR.sgT1-C1.tRFP or pL-CRISPR.sgT3-C1.tRFP plasmid was transiently transfected into HEK293FT cells to check the knockout efficiency for either sgT1 or sgT3. RFP signals indicated the transfection efficiency. B. WB analysis for TBCK and TBCK related proteins. C. Normalized protein levels of TBCK and related proteins based on the gray value (calculated by Image J) for each target.

Figure 6.

Single cell clone selection and validation in MIA PaCa-2 cell model. A. Immunoblot analysis to screen positive knockout clones. 3 clones (C2/C6/C11 marked with red arrow) were selected for fluorescence checking (B). C. PCR results showed that sgCtrl cells only generated one single band (461bp), while sgT3 cells either generated on single band (C2) or two bands (C6/C11). D. Sanger sequencing analysis demonstrated that no mutations were found in sgCtrl cells, while T insertion was verified in all 3 clones of sgT3 cells. E. Sanger sequencing analysis demonstrated that the whole exon 3 and portion of intron 2 were missing in clone 6 and clone 11. F. Schematic for potential outcomes due to T insertion or exon3 skipping mediated by CRISPR. G. Immunoblot analysis for TBCK in whole membrane with MIA PaCa-2 protein (sgCtrl and 3 sgT3 clones (C2/C6/C11)) to check whether novel protein products would be generated or not regarding TBCK depletion mediated by CRISPR-Cas9.

Figure 6.

Single cell clone selection and validation in MIA PaCa-2 cell model. A. Immunoblot analysis to screen positive knockout clones. 3 clones (C2/C6/C11 marked with red arrow) were selected for fluorescence checking (B). C. PCR results showed that sgCtrl cells only generated one single band (461bp), while sgT3 cells either generated on single band (C2) or two bands (C6/C11). D. Sanger sequencing analysis demonstrated that no mutations were found in sgCtrl cells, while T insertion was verified in all 3 clones of sgT3 cells. E. Sanger sequencing analysis demonstrated that the whole exon 3 and portion of intron 2 were missing in clone 6 and clone 11. F. Schematic for potential outcomes due to T insertion or exon3 skipping mediated by CRISPR. G. Immunoblot analysis for TBCK in whole membrane with MIA PaCa-2 protein (sgCtrl and 3 sgT3 clones (C2/C6/C11)) to check whether novel protein products would be generated or not regarding TBCK depletion mediated by CRISPR-Cas9.

Figure 7.

Single cell clone selection and validation in Fibrosarcoma HT1080 cell model. A. Immunoblot analysis to screen positive knockout clones. B. PCR results showed that Both sgCtrl and sgT3-C1 cells generated one single band (461bp). C. Sanger sequencing analysis demonstrated that no mutations were found in sgCtrl cells, while T insertion was verified in sgT3-C1 cells.

Figure 7.

Single cell clone selection and validation in Fibrosarcoma HT1080 cell model. A. Immunoblot analysis to screen positive knockout clones. B. PCR results showed that Both sgCtrl and sgT3-C1 cells generated one single band (461bp). C. Sanger sequencing analysis demonstrated that no mutations were found in sgCtrl cells, while T insertion was verified in sgT3-C1 cells.

Figure 8.

The human specific sgTBCK has little effects on mouse cells. A. Sequence alignment between human and mouse TBCK mRNA uncovered a two-base mismatch in sgRNA region. B. sgCtrl and 3 sgT3 clones were chosen because of high RFP signals, representing plenty of lentivirus particles in cells. C. Immunoblot analysis to screen positive knockout clones. D. PCR results showed that both sgCtrl and 4 sgT3 clones generated one single band (532bp). E. Sanger sequencing analysis supported that no mutations were found in sgRNA region for all sgCtrl and sgT3 clones. Blue background represents sgRNA region.

Figure 8.

The human specific sgTBCK has little effects on mouse cells. A. Sequence alignment between human and mouse TBCK mRNA uncovered a two-base mismatch in sgRNA region. B. sgCtrl and 3 sgT3 clones were chosen because of high RFP signals, representing plenty of lentivirus particles in cells. C. Immunoblot analysis to screen positive knockout clones. D. PCR results showed that both sgCtrl and 4 sgT3 clones generated one single band (532bp). E. Sanger sequencing analysis supported that no mutations were found in sgRNA region for all sgCtrl and sgT3 clones. Blue background represents sgRNA region.

Figure 9.

RNA-seq application for TBCK KO single clone in PDAC model. A. Immunoblot analysis for RNA-seq samples to confirm the depletion of TBCK. B. Genes significantly induced or repressed in MIA PaCa-2-sgT3 cells were determined using an average log 2-fold-change greater than 1 and a false-discovery rate less than 5% were differentially expressed. The blue symbols denote repressed genes, and the red symbols denote induced genes. C. ENRICHR analysis to determine the pathways that are associated with the negatively selected genes from MIA PaCa-2-sgT3 cells. D. ENRICHR analysis to determine the pathways that are associated with the positively selected genes from MIA PaCa-2-sgT3 cells. E. Heatmap depicting the differential expression of selected genes in enriched pathways. F. GSEA analysis identified the downregulated genes in MIA PaCa-2-sgT3 cells were significantly enriched for ER response, p53 and EMT pathways, as well as upregulated genes were significantly enriched for interferon gamma, metabolism and E2F pathways. G. Column graph indicates the relative expression of selected downregulated and upregulated genes based on transcriptome analysis. Error bar represents mean and SD. (**p<0.001 as determine student t-test).

Figure 9.

RNA-seq application for TBCK KO single clone in PDAC model. A. Immunoblot analysis for RNA-seq samples to confirm the depletion of TBCK. B. Genes significantly induced or repressed in MIA PaCa-2-sgT3 cells were determined using an average log 2-fold-change greater than 1 and a false-discovery rate less than 5% were differentially expressed. The blue symbols denote repressed genes, and the red symbols denote induced genes. C. ENRICHR analysis to determine the pathways that are associated with the negatively selected genes from MIA PaCa-2-sgT3 cells. D. ENRICHR analysis to determine the pathways that are associated with the positively selected genes from MIA PaCa-2-sgT3 cells. E. Heatmap depicting the differential expression of selected genes in enriched pathways. F. GSEA analysis identified the downregulated genes in MIA PaCa-2-sgT3 cells were significantly enriched for ER response, p53 and EMT pathways, as well as upregulated genes were significantly enriched for interferon gamma, metabolism and E2F pathways. G. Column graph indicates the relative expression of selected downregulated and upregulated genes based on transcriptome analysis. Error bar represents mean and SD. (**p<0.001 as determine student t-test).

Figure 10.

GO-term enrichment and STRING analysis for TBCK KO single clone in PDAC model. A. The GO analysis of 314 significantly downregulated genes, including biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF). B. Heatmap depicting the differential expression of selected genes in three enriched processes (GO: 0042326; GO: 0030308; and GO: 0062023). C. The GO analysis of 184 significantly upregulated genes, including biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF). D. Heatmap depicting the differential expression of selected genes in three enriched processes (GO: 0002495 and GO: 0098791). E. STRING analysis for TBCK and upregulated DEGs. Arrow shows isolated TBCK. F. STRING analysis for TBCK and downregulated DEGs and discovered a connect between TBCK and PLXNB2. G. 9 candidate proteins were reanalyzed by string webserver. H. Heatmap depicting the differential expression of 8 selected genes in downregulated DEGs.

Figure 10.

GO-term enrichment and STRING analysis for TBCK KO single clone in PDAC model. A. The GO analysis of 314 significantly downregulated genes, including biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF). B. Heatmap depicting the differential expression of selected genes in three enriched processes (GO: 0042326; GO: 0030308; and GO: 0062023). C. The GO analysis of 184 significantly upregulated genes, including biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF). D. Heatmap depicting the differential expression of selected genes in three enriched processes (GO: 0002495 and GO: 0098791). E. STRING analysis for TBCK and upregulated DEGs. Arrow shows isolated TBCK. F. STRING analysis for TBCK and downregulated DEGs and discovered a connect between TBCK and PLXNB2. G. 9 candidate proteins were reanalyzed by string webserver. H. Heatmap depicting the differential expression of 8 selected genes in downregulated DEGs.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used for sgRNA cloning, RT-PCR and sequencing analysis.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used for sgRNA cloning, RT-PCR and sequencing analysis.

| Experiment |

Gene |

Forward Primer, 5' → 3′ |

Reverse Primer, 5' → 3′ |

Accession Number |

| sgCtrl |

Control |

CACCGACGGAGGCTAAGCGTCGCAA |

AAACTTGCGACGCTTAGCCTCCGTC |

NA |

| sgT1 |

hTBCK |

CACCGCATAACGACAATGTCACAG |

AAACCTGTGACATTGTCGTTATGC |

NM_001163435.3 |

| sgT3 |

hTBCK |

CACCGTTCGAGAAAGGAAACCTGTG |

AAACCACAGGTTTCCTTTCTCGAAC |

NM_001163435.3 |

| RT-PCR |

U6 |

GAGGGCCTATTTCCCATGATT |

|

NA |

| |

hTBCK |

GTGTGTCAGAAGAAGGGTGAGT |

AAACCAAACCCCTGCAGTTTA |

NG_034057.3 |

| |

mTBCK |

GGTGGATGGGGTGCTTACAT |

CTCCGGGCTAGGGGAATAAG |

NC_000069.7 |

Table 2.

Design of TBCK sgRNAs using online sgRNA designer tool together with Human CRISPR Knockout Pooled Library.

Table 2.

Design of TBCK sgRNAs using online sgRNA designer tool together with Human CRISPR Knockout Pooled Library.

| Source |

Gene_id |

UID |

seq |

PAM |

Exon Number |

On-Target Efficacy Score |

Rank for sgTBCK via Online Tool |

| human_geckov2_library_a |

TBCK |

HGLibA_48598 |

TGAACATTGTGAACGTAGTC |

TGG |

3 |

0.4328 |

182 |

| |

TBCK |

HGLibA_48599 |

CTCCCATTTCAGCGTCCTTC |

GGG |

2 |

0.2272 |

258 |

| |

TBCK |

HGLibA_48600 |

AGCCGAGGCAAAGAAGGTAA |

AGG |

2 |

0.5571 |

86 |

| human_geckov2_library_b |

TBCK |

HGLibB_48539 |

TTCGAGAAAGGAAACCTGTG |

AGG |

3 |

0.7099 |

8 |

| |

TBCK |

HGLibB_48540 |

AAGAAAATTATTTCAGAGCT |

TGG |

7 |

0.3958 |

201 |

| |

TBCK |

HGLibB_48541 |

TTGCTTCCACAAACATCATG |

TGG |

2 |

0.6266 |

36 |

| Online tool sgRNA designer |

TBCK |

NA |

GCATAACGACAATGTCACAG |

TGG |

12 |

0.7724 |

3 |

Table 3.

Target cell infection (human and mouse cells).

Table 3.

Target cell infection (human and mouse cells).

| Cell Line Name |

Species |

Tumor Type |

Genetic Information |

TBCK Expression |

| MiaPaca-2 |

Homo Sapiens |

PDAC |

Kras (G12C); c-Myc (WT); TP53(R248W); RB1(WT) |

High |

| HT1080 |

Homo Sapiens |

Fibrosarcoma |

Kras (WT); c-Myc (WT); TP53(WT); RB1(WT) |

High |

| KPC3 mouse cell line |

Mus musculus |

Mouse pancreatic neoplasm |

Kras (G12D); c-Myc (WT); TP53(R270H); RB1(WT) |

High |