1. Introduction

A lot of neurodegenerative diseases (NDDs) are known in human. Pathological and clinical characteristics of NDDs are different but partially similar among some NDDs. Alzheimer’s disease (AD), Parkinson diseases (PD), frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD), nine polyglutamine (polyQ) diseases including Huntington’s disease (HD) and other many diseases are included in NDDs. To date, scientists have succeeded only to develop the medicine to delay the progression by a short period but cannot obtain the remedies for complete cure [

1,

2]. A lot of pharmaceutical companies, laboratories, and universities all over the world have been trying to develop drugs that completely or effectively cure NDDs for a long time, but unexpectedly, no research groups and no scientists have not acquired any epoch-making success [

3,

4,

5].

As a common phenomenon, aggregates (inclusion bodies) containing the specific protein for each NDD and other protein are formed inside neuronal cells. Our group uses the

in vitro and

in vivo polyQ disease model, and have been trying to discover the novel molecular mechanisms causing NDDs and the effective chemical compounds and/or peptides leading to the development of novel drugs capable of their complete cure. Recently, we discovered a novel mechanism that Nuclear Factor of Activated T-cell cytoplasmic 2 (NFATc2) has an unexpected ability to effectively degrade the polyQ aggregates through ubiquitin-proteasome system [

6,

7]. NFATc2 is a critical transcription factor in immune system [

8,

9,

10]; therefore, it is surprising that NFATc2 has a strong ability to suppress and reduce the protein aggregation. In this novel mechanism, NFATc2 activates the transcription of two key genes, PDZ domain containing 3 (PDZK3) and small chaperone alphaB-crystallin (CRYAB). PDZK3 is a large protein as 250kDa and scaffold protein [

11,

12] and CRYAB is reported as a component of SCF-type ubiquitin-ligase complex [

13,

14]; thus, we proposed that PDZK3 and CRYAB proteins form a SCF-type E3 ligase complex with other proteins [

6].

PDZK3 and CRYAB were more efficiently induced by the combination of NFATc2 and Heat Shock transcription Factor 1 (HSF1) [

6]. HSF1 is known as a transcription factor to maintain proteostasis by preserving the precise folding of proteins through induction of most Heat Shock Proteins (HSPs). Therefore, our finding that HSF1 is involved in protein degradation exhibited the new aspect of intracellular proteostasis mechanism.

While we proceed the experiments described above, we found about 30 interesting chemicals and peptides which can be the candidates for seed compounds for anti-NDDs drugs. We tested their capability to suppress the aggregation caused by R406W mutant tau protein found in FTLD patients or polyQ protein. After several experiments, we discovered that phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) significantly not only inhibits aggregate formation but also promotes neurite outgrowth of human neuronal cells. In this paper, we show the novel PMA effects on human neuronal cell and discuss the possibility as a seed compound to develop effective anti-NDDs drugs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

SH-SY5Y (human neuroblastoma cells), Neuro-2a (mouse neuroblastoma cells), and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were maintained at 37oC in 5% CO2 in in DMEM (GIBCO) containing 10% FBS supplemented with penicillin and streptomycin.

2.2. Reagents

Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA, Nacalai Tesque) was resolved in DMSO. β-amyloid (1-42) (Anaspec) was resolved in ammonium chloride (NH4Cl) and diluted with 3x volume of PBS according to the manufacturer's protocol. All reagents were stored at -20oC until use. PMA was completely resolved in 1mL culture medium, and then, added to cell culturing medium (9 mL) in 10 cm dishes.

2.3. Antibodies

Anti-HSF1 (mHSF1j) and anti-HSF2 (mHSF2-4) rabbit antiserum was raised by N.H. Anti-β-actin antibody was purchased from Sigma. Anti-Hsp70 (W27) antibody was purchased from GENETEX. Anti-alphaB Crystallin antibody was purchased from Abcam. Anti-GFP (GF200) monoclonal antibody was purchased from Nacalai Tesque [

6].

2.4. Construction of Tau-GFP and R406W Mutant Tau (mTau)-GFP Expression Vectors

Human tau cDNA was cloned from HeLa cells (primers’ sequences are listed in Table 1). We already established the polyQ81 (containing continuous 81 glutamine amino acids) -enhanced GFP (EGFP)-expressing pShuttle-CMV vector (polyQ81-GFP) [

6], thus we replaced the polyQ81 sequence with Tau cDNA in KpnI/BamHI sites and constructed Tau-GFP vector. Insertion of R406W mutation into Tau-GFP sequence was performed by two-step PCR (the primers are listed in Table 1). Full length tau and R406W tau cDNAs were sequenced and insertion of mutation was confirmed. Tau-GFP and R406W mutant Tau-GFP (mTau-GFP) vectors were transfected by Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) into SH-SY5Y and Neuro-2a cells cultured in poly-D-lysine coated 10mm diameter dishes (Corning) in 80-90% confluent condition. Construction of polyQ81-GFP pShuttle-CMV vector and preparation of caHSF1-expressing adenovirus was already described [

6].

2.5. Generation of Aggregates and Count of Aggregates-Positive Cells

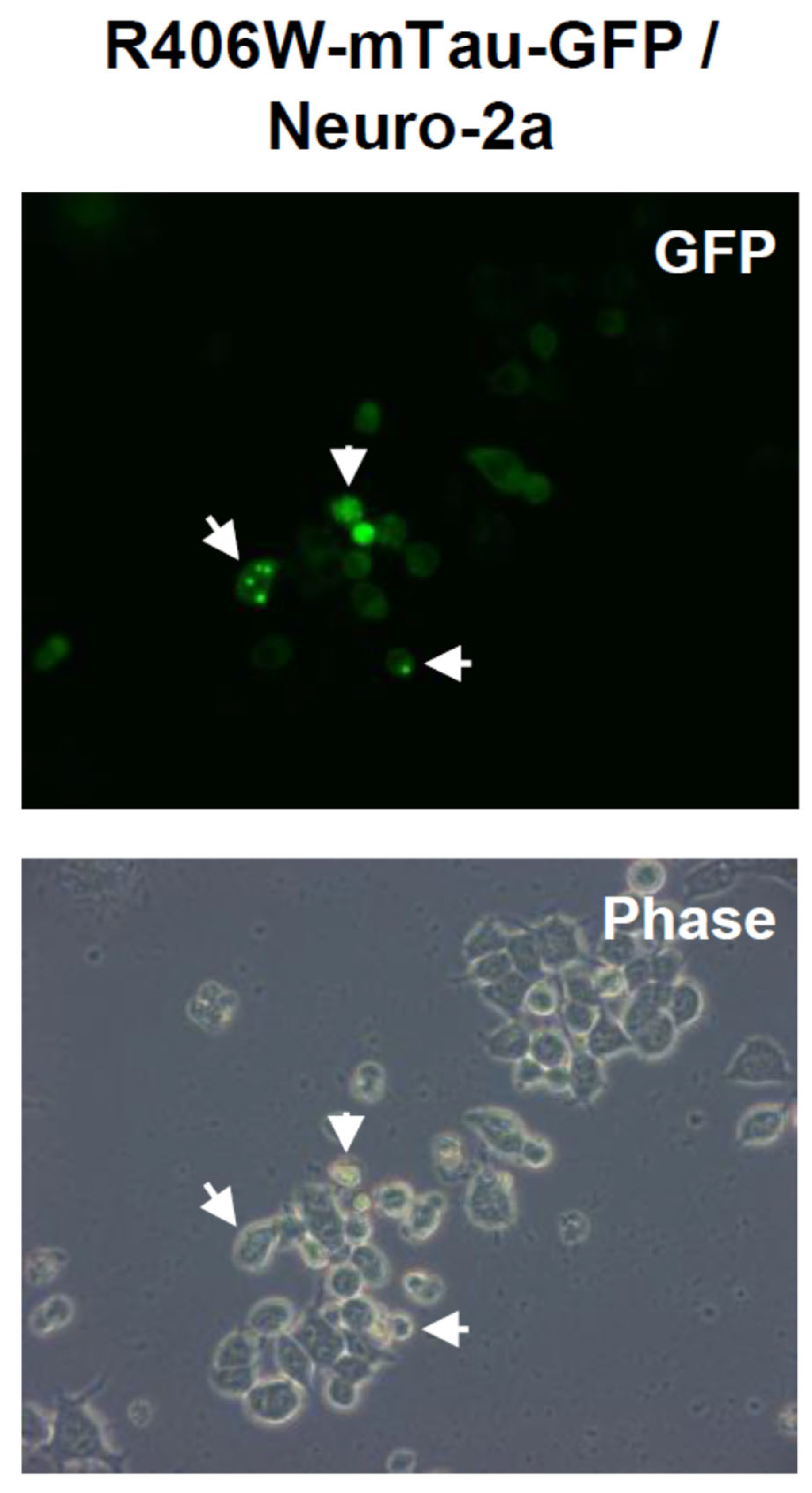

Tau-GFP, mTau-GFP, and polyQ81-GFP proteins were expressed by transfection of their vectors. mTau-GFP protein successfully formed clear aggregates in many SH-SY5Y and Neuro-2a cells (Figures 1A and S1A). PolyQ81-GFP protein also formed clear aggregates in mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (

Figure 4) [

6]. We counted the number of GFP-fluorescent cells and subsequently counted the cells containing fluorescent aggregates in dark room. We counted the cell number at least three different areas per one dish and calculated the percentages of the cells with aggregates in the dish.

Figure 1.

Aggregate formation of R406W mutant tau protein in mouse neuroblastoma Neuro-2a. Aggregates (inclusion bodies, indicated by arrows) formed by R406W mutant tau protein conjugated with GFP (mTau-GFP) in Neuro-2a cells. mTau-GFP protein was expressed by transfection. These photos were taken at 5days after transfection.

Figure 1.

Aggregate formation of R406W mutant tau protein in mouse neuroblastoma Neuro-2a. Aggregates (inclusion bodies, indicated by arrows) formed by R406W mutant tau protein conjugated with GFP (mTau-GFP) in Neuro-2a cells. mTau-GFP protein was expressed by transfection. These photos were taken at 5days after transfection.

2.6. Western Blot Analysis and Quantification of Soluble/Insoluble mTau-GFP Protein, HSP70, CRYAB, HSF1 and HSF2

The cell extracts are resolved in NP40 buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1.0% Nonidet P-40). 1x Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Promega) and 100mM Dithiothreitol (DTT, Nacalai Tesque) was added to cell extract suspension. Suspension (protein solution) tubes were kept on ice at least for 15 min. Subsequently, protein solution tubes were centrifugated at 15,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was used for Western blot (Figures S1C and S2B). For insoluble protein preparation (Figure S1C), the resultant pellet was washed 5 times (sonicated and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm) with NP40 buffer. To the final resultant pellet, the equivalent volume of RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl pH8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1.0% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, 1 mM β-mercaptoetanol) was added with 1x Protease Inhibitor Cocktail and 100mM DTT. This was used as insoluble protein solution. The same volume of soluble and insoluble protein solution was subjected to SDS-PAGE.

For SDS-PAGE, CriterionTM TGXTM Gel (10%) (Bio-Rad) and Tris/glycine/SDS buffer (25mM Tris, 192mM glycine, 0.1% SDS, pH8.3) was used. To each lane, 15-30 μg of soluble protein was applied, and SDS-PAGE was performed using CriterionTM Cell (Bio-Rad) for 1 hr. For protein transfer, nitrocellulose membrane Mini-PROTEANR (Bio-Rad) was used. Transfer was performed in CriterionTM Transblot Cell for 2hr at room temperature. The transferred membrane was applied to blocking in the PBS solution containing 5% skim milk powder (Wako) for 1 hr. The membrane was reacted with each primary antibody in the PBS solution containing 2% skim milk powder for O/N at 4oC. Subsequently, the membrane was reacted with secondary antibody conjugated with HRP (SouthernBiotech) in the same solution for 1hr at room temperature. The resulting membrane was applied to ImmunoStarR Zeta (Wako) and photographed using an Amersham Imager (GE Healthcare).

To measure and compare the amount of protein, the bands of Western blot were scanned and quantified by NIH Image-J (free software,

https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). To prepare the graphs showing relative amount of each protein (

Figure 3B and S1D), the values of all bands were divided by control band. These values are shown in both soluble (

Figure 3B and S1D, left) and insoluble (Figure S1D, right) graphs. The relative value of control band is described as 1.00.

2.7. Semi-Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from the cell pellet using TRIzol (Invitrogen). cDNA was synthesized using Prime Script 1

st strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara). PCR was performed using the same condition for all samples. PCR cycle was [94

oC (denature, 1 min) - 65

oC (annealing, 1 min) - 72

oC (extension, 1 min)] and repeated 35 times. Ex-Taq (Takara) was used for PCR. Amplified DNA samples (10 μL) were mixed with 2 μL of Blue Juice Gel Loading Buffer (10X) (ThermoScientific), and applied to agar gel electrophoresis for 15 min. The gel contained ethidium bromide and 2% agar. The resultant gel was photographed on the transilluminator using Printgraph S (ATTO). The photos of DNA bands were scanned and quantified by NIH Image-J as well as Western blot analysis. As internal control, 18S ribosomal RNA (18S) was used. We examined the gene expression by measuring strength of all bands using Image-J and these values were compensated by 18S bands [

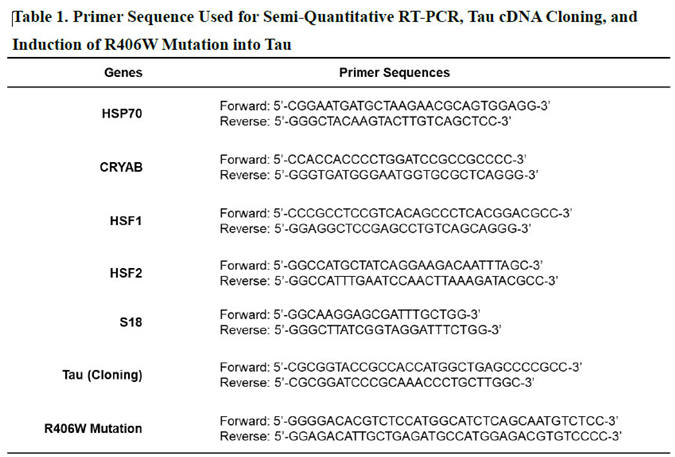

7]. All primers sequences used for RT-PCR are shown in Table 1.

2.8. Measurement of Neurite Length

We measured soma (cell body) size in more than one hundred of SH-SY5Y cells and calculated the averaged diameter using Image-J and determined it as 5.0 μm in this study. We chose 100-150 neurites per one dish and examined whether the length of these neurites is longer than 5 or 10 times of soma diameter or not.

2.9. Statistical Analysis

Data are shown with standard deviation. The significance was analyzed using student t test. The p-values are shown in graphs and considered as significant when they are <0.05. The p-value is described as ‘N.S.’ when it was not significant.

3. Results

3.1. R406W Mutant Tau Protein Conjugated with GFP Forms Aggregates/Inclusion in Neuronal Cells

In order to find the candidate chemicals/peptides (proteins) for the seeds of therapeutic drugs, we looked into our previous discovery that Nuclear factor of activated T-cell cytoplasmic 2 (NFATc2) and Heat shock transcription factor 1 (HSF1) significantly suppress aggregation of the proteins containing 81 polyglutamine (polyQ81) tract [

6]. By this investigation, we thought that it is necessary to establish a new culture protein-aggregation system in addition to polyQ81 system.

Tau protein belongs to the family of microtubule-associated proteins and mainly expresses in neurons, and has important roles in the assembly of tubulin monomers into microtubules in order to constitute the neuronal microtubules network [

15]. However, abnormal tau protein causes various NDDs called tauopathy including Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). All over the world, patients of tauopathy are increasing year by year. In both AD and FTLD, aggregates formed by misfolded tau protein are generated. In AD, hyperphosphorylated tau protein is accumulated, also in FTLD, mutated and hyperphosphorylated tau protein aggregates. We examined whether R406W mutant tau protein causing FTLD conjugated with GFP (mTau-GFP) forms aggregates. As described in Materials and Methods, R406W is frequently found mutation in FTLD patients [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. We transfected mTau-GFP expression vector into Neuro-2a and succeeded the expression of mTau-GFP in 60-70% cells (

Figure 1). In addition, we observed that mTau-GFP also formed aggregates in 20% of Neuro-2a cells (

Figure 1). We did not find the aggregates in normal Tau-GFP-expressing cells.

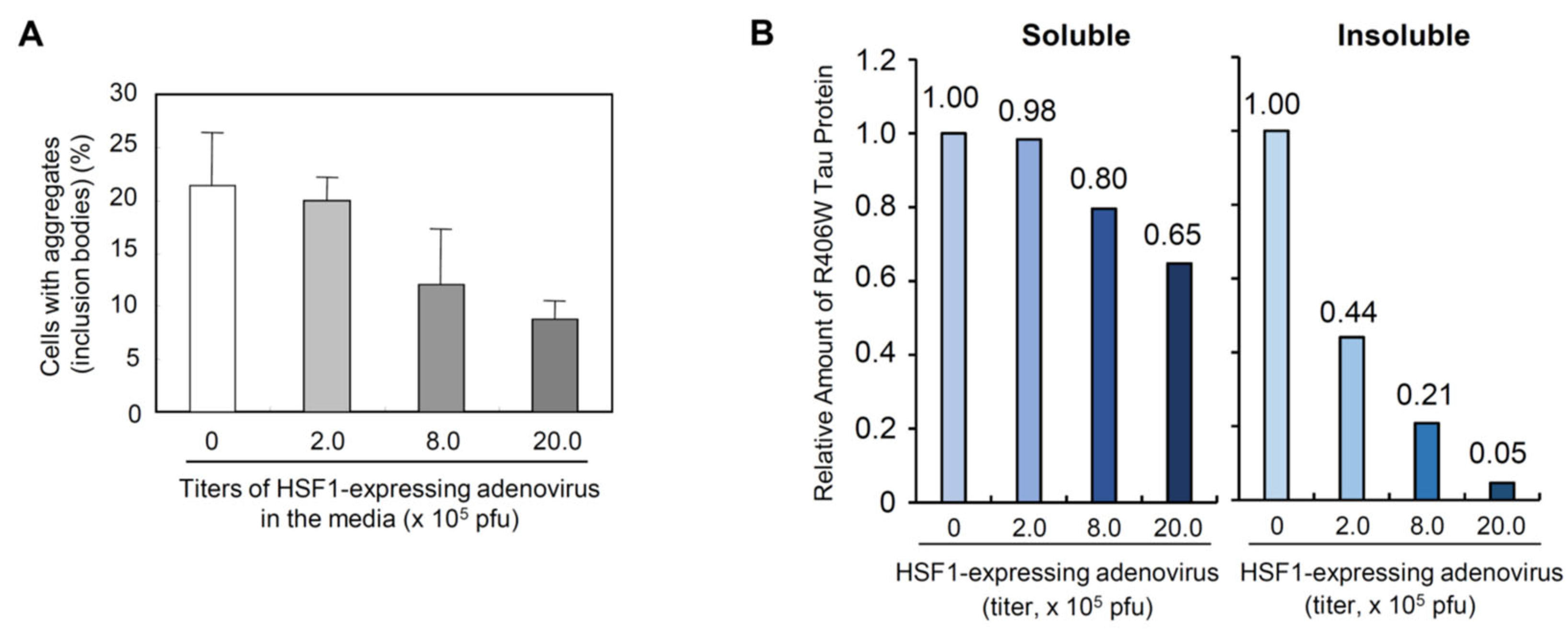

3.2. High Titer of caHSF1-Expressing Adenovirus Reduced Decreased Aggregates-Positive Cell Number and Dramatically Reduced the Amount of Accumulated Insoluble R406W Mutant Tau Protein

As far as we know, toxic aggregates and/or oligomers formed by misfolded proteins are generated inside neurons in all NDDs; thus, we thought that elimination of aggregates inside neurons lead to cure of NDDs. To reveal whether HSF1 suppresses mutant tau aggregation as well as polyglutamine (polyQ) protein, we expressed constitutive active HSF1 (caHSF1) using adenovirus system [

6,

21]. In this system, higher titer virus induced much amount of caHSF1 protein expression and more efficiently decreased mTau-GFP aggregate-positive cells (

Figure 2A). At the highest titer (20 x 10

5 pfu), the number of cells with aggregates were prominently reduced to 33% of control and less than 10% of total GFP positive cells (

Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

Effect of higher titer of caHSF1-expressing adenovirus on the mTau-GFP aggregates (inclusion bodies) in Neuro-2a. Aggregates-positive cells were counted at 5days after transfection. A: Effect of higher titer of caHSF1-expressing adenovirus on the amount of soluble R406W tau (soluble mTau-GFP) and accumulation of insoluble R406W tau (insoluble mTau-GFP) proteins shown by Western blot. B: Graphs showing relative amount of soluble and insoluble R406W tau protein. These values were calculated from the bands of the blots shown in Figure S1. In both graphs, the value of the control band indicated as 1.00.

Figure 2.

Effect of higher titer of caHSF1-expressing adenovirus on the mTau-GFP aggregates (inclusion bodies) in Neuro-2a. Aggregates-positive cells were counted at 5days after transfection. A: Effect of higher titer of caHSF1-expressing adenovirus on the amount of soluble R406W tau (soluble mTau-GFP) and accumulation of insoluble R406W tau (insoluble mTau-GFP) proteins shown by Western blot. B: Graphs showing relative amount of soluble and insoluble R406W tau protein. These values were calculated from the bands of the blots shown in Figure S1. In both graphs, the value of the control band indicated as 1.00.

In addition to the decrease of the cells with aggregates, the amount of mTau-GFP was reduced (Figure S1, top and second gel). Soluble mTau-GFP (described as Soluble R406W Tau) was slightly reduced by caHSF1. Surprisingly, insoluble mTau-GFP (Insoluble R406W Tau) was dramatically reduced (Figure S1, second gel from the top). caHSF1 induces many kinds of chaperone proteins and NFATc2, and caHSF1 and NFATc2 can degrade proteins probably through the construction of SCF-like E3 ligase complex [

6]. The decrease of soluble mTau-GFP can be due to the degradation by caHSF1, NFATc2 induced by caHSF1, and other proteostasis-related proteins.

It is noteworthy that the degradation efficiency of insoluble mTau-GFP is much higher than that of soluble mTau-GFP (Figure S1) although unknown degradation systems must be involved in the insoluble mTau-GFP degradation. When mutant tau or other toxic proteins causing NDDs are synthesized inside neuronal cells, if they are soluble, most of them can be easily eliminated by degradation systems of the cell and/or refolded to precise structure by chaperone system. However, insoluble misfolded proteins causing NDDs cannot be resolved easily and subsequently accumulate inside cells. They accumulate in nuclei, mitochondria, and other intracellular small components. We think that the drugs to cure NDDs need to have abilities to resolve and/or remove these accumulated insoluble proteins.

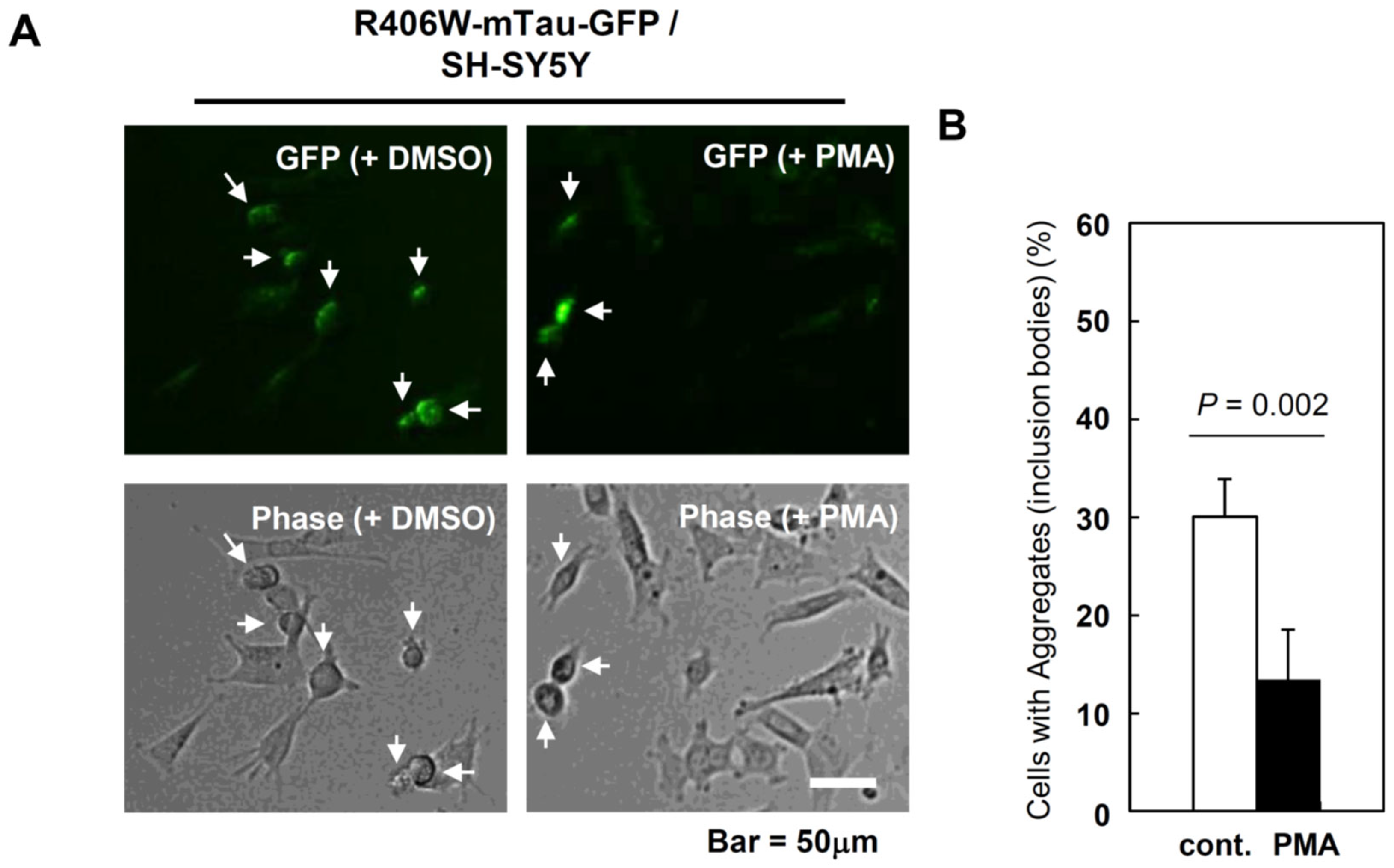

3.3. PMA Suppressed the Aggregates/Inclusion Formation by R406W Mutant Tau Protein in Human Neuronal Cells

We successfully established a new culture system to examine the mutant tau protein aggregation using Neuro-2a. Neuro-2a is a widely used cell line, but this is murine, not human cell. For the purpose to discover the seed drugs for NDDs, we thought that human cells are better than murine cells for all in vitro experiments. When we analyzed the degradation mechanism in previous experiments, we experienced that the acquired results of murine and human cells were prominently different. Therefore, we tested human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells in subsequent experiments.

We transfected Tau-GFP or mTau-GFP vectors into SH-SY5Y human neuronal (neuroblastoma) cells. We used the same transfection method as Neuro-2a, but we could successfully observe the expression of both proteins (

Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Aggregation of R406W mutant tau protein in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y and effect of PMA treatment. A: R406W mutant tau protein conjugated with GFP (mTau-GFP) forms aggregates (inclusion bodies, indicated by arrows) in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. mTau-GFP was expressed by transfection. PMA was dissolved in DMSO and added to culture medium at 6hr after transfection. DMSO was also added to control dish. PMA concentration is 1.0 nM. These photos were taken at 5days after transfection. B: Decrease of aggregates-positive cells by PMA treatment.

Figure 3.

Aggregation of R406W mutant tau protein in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y and effect of PMA treatment. A: R406W mutant tau protein conjugated with GFP (mTau-GFP) forms aggregates (inclusion bodies, indicated by arrows) in human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. mTau-GFP was expressed by transfection. PMA was dissolved in DMSO and added to culture medium at 6hr after transfection. DMSO was also added to control dish. PMA concentration is 1.0 nM. These photos were taken at 5days after transfection. B: Decrease of aggregates-positive cells by PMA treatment.

Expression of Tau-GFP and mTau-GFP in SH-SY5Y was a little more difficult than in Neuro-2a (please compare

Figure 1 and

Figure 3A). No cells transfected with Tau-GFP formed aggregates, and the fluorescence level was very low. In the case of the cells transfected with mTau-GFP, fluorescence of aggregates was very clear and the difference between the cells with aggregates and the cells without aggregates was very clear (

Figure 3A). Therefore, to calculate the percentage of aggregates-forming cells in total cells including non-fluorescent cells was very easy in this system.

While we tried to establish the system that Tau-GFP and mTau-GFP protein is expressed in SH-SY5Y cells, we selected about 30 chemicals and peptides (proteins) as candidates for seeds of therapeutic drugs. The purpose was to discover molecules which can decrease the percentage of aggregates-positive cells. ‘If we succeed to discover such molecules, it must be the good candidates for the NDDs therapeutics’ we thought. As a method to find such molecules, we examined chemicals related to NFATc2 and HSF1 at first. The reason is that these transcription factors have ability to suppress misfolded protein aggregation [

6].

We repeatedly tested their suppression ability of aggregation using polyQ81-GFP and mTau-GFP systems, and finally determined the PKC signaling pathway-activating compound phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) as a first candidate [

22,

23]. PMA is known to full-activate NFATc2 by combination with calcium ionophore ionomycin, thus we thought this character of PMA related to NFATc2 activation contributes to aggregation suppression. PKC signaling pathway is related to HSF1 activaton [

1]. According to ionomycin, neuronal cells are vulnerable to increase of calcium concentration and result in cell death including apoptosis [

24,

25]. Thus, we excluded it from the candidates.

We transfected mTau-GFP expression vector into SH-SY5Y and PMA was added to culture medium at 6 hr after transfection (final concentration was 1.0 nM). The same volume of DMSO was also added to control. We counted aggregates-positive cells at 5 days after transfection. In control cells, aggregates were formed in 30% of total cells (

Figure 3A, left). Compared to control, aggregate formation was efficiently suppressed and only 12.5% of total cells were aggregates-positive in PMA-treated cells (

Figure 3A, right and

Figure 3B). The suppression rate was approximately 60%.

Figure 3 indicates PMA has an ability to suppress/reduce the aggregate formation by misfolded proteins, especially mutant tau protein.

3.4. PMA Promotes Neurite Growth in Human NDDs Cell Culture Models

In NDDs, specific brain regions are damaged, axonal degeneration and cell death of neurons occurred in these regions. These dangers cause dementia, defects of some brain functions, and sometimes results in the death of individuals [

26,

27]. Also, maintenance of axons and their growth are indispensable for normal brain functions [

28,

29]. Thus, the axonal damage can be the cause of NDDs. Although the suppression of aggregates formation is indispensable for the cure of NDDs, promotion of axonal regeneration is also required [

30,

31]. To investigate the extent to which axonal regeneration is promoted by PMA, we used FTLD and AD cell culture models.

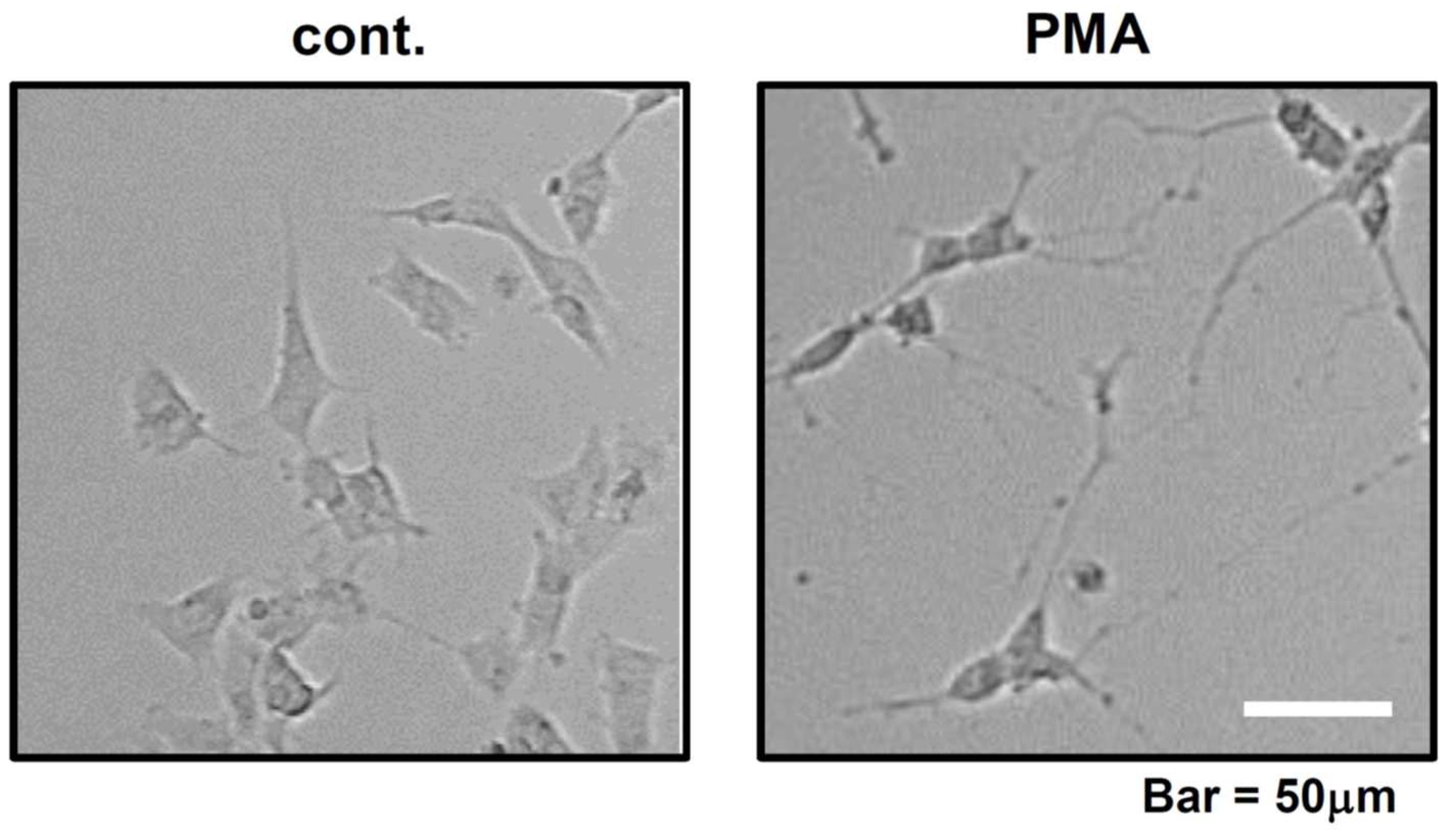

Before investigating the effect of PMA in FTLD and AD culture models, we examined the extent to which axonal generation is promoted by PMA in normal culture. We added DMSO (cont.) and PMA (1.0 nM) to the SH-SY5Y culture medium and observed the cells at 7 days after treatment. Compared to control, PMA significantly promoted neurite extension (

Figure 4, right). DMSO has a weak ability to promote differentiation, thus only short neurite extension was observed in control DMSO culture (

Figure 4, left). Expectedly, we could demonstrate that PMA has an ability to promote neurite generation and/or extension.

Figure 4.

Neurite growth of SH-SY5Y cells in control and PMA-added dishes. PMA concentration is 1.0 nM. Control dish was treated with DMSO. Both photos were taken at 7 days after DMSO and PMA treatment.

Figure 4.

Neurite growth of SH-SY5Y cells in control and PMA-added dishes. PMA concentration is 1.0 nM. Control dish was treated with DMSO. Both photos were taken at 7 days after DMSO and PMA treatment.

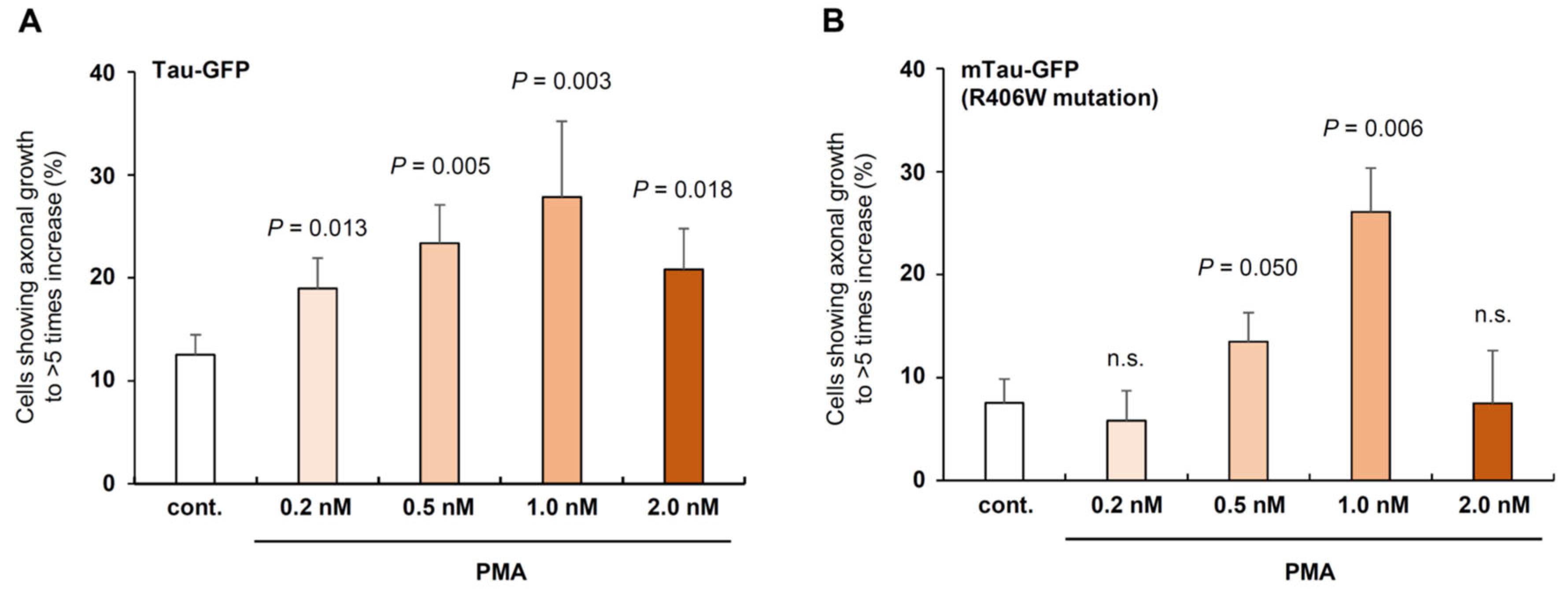

Next, we examined the extent to which PMA promotes neurite regeneration in FTLD culture model. FTLD culture model was established by mTau-GFP expression and generation of aggregates in SH-SY5Y cells (

Figure 5). In this experiment, Tau-GFP was also expressed as control cell culture.

At 7 days after transfection, Tau-GFP and mTau-GFP expression was clearly observed and aggregates were generated in only mTau-GFP cells. We added PMA at various concentration and DMSO was added to control dishes (

Figure 5A and 5B). In Tau-GFP expressing cells, the percentage of the cells with the axonal length of >5 of soma diameter was higher than control in all PMA concentrations (

Figure 5A). The percentage of the cells was highest at 1.0 nM and it was approximately 30%, this value is 2.5 times as high as control (

Figure 5A).

In mTau-GFP expressing cells, PMA effect was not significantly different from the control at 0.2 nM and 2.0 nM, but significant at 0.5 nM and 1.0 nM (

Figure 5B). Although the percentages at 0.5 nM PMA was 1/2 of Tau-GFP, PMA at 1.0 nM significantly increased the percentage of mTau-GFP cells with >5-fold neurite length of soma diameter to 25% (

Figure 5B). In NDDs, axonal degeneration causes dementia as well as neuronal death [

26,

27]. It is noteworthy that this percentage was almost the same to Tau-GFP expressed cells and that this result indicates that PMA may be able to retrieve the normal condition of neurites and axons even when aggregates are formed inside neuronal cells (

Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Effect of PMA in Tau-GFP or mTau-GFP expressing SH-SY5Y cells. A: PMA in 0.2-2.0 nM concentration on neurite growth in normal Tau-GFP protein overexpressing cells compared to control (DMSO is added to the media). Neurite growth was examined at the 7days after DMSO and PMA treatment. B: PMA on the neurite growth of mTau-GFP overexpressing cells. Neurite growth of Tau-GFP cells and mTau-GFP cells was examined at the same day (7 days after DMSO and PMA treatment). PMA concentration was shown in the graph.

Figure 5.

Effect of PMA in Tau-GFP or mTau-GFP expressing SH-SY5Y cells. A: PMA in 0.2-2.0 nM concentration on neurite growth in normal Tau-GFP protein overexpressing cells compared to control (DMSO is added to the media). Neurite growth was examined at the 7days after DMSO and PMA treatment. B: PMA on the neurite growth of mTau-GFP overexpressing cells. Neurite growth of Tau-GFP cells and mTau-GFP cells was examined at the same day (7 days after DMSO and PMA treatment). PMA concentration was shown in the graph.

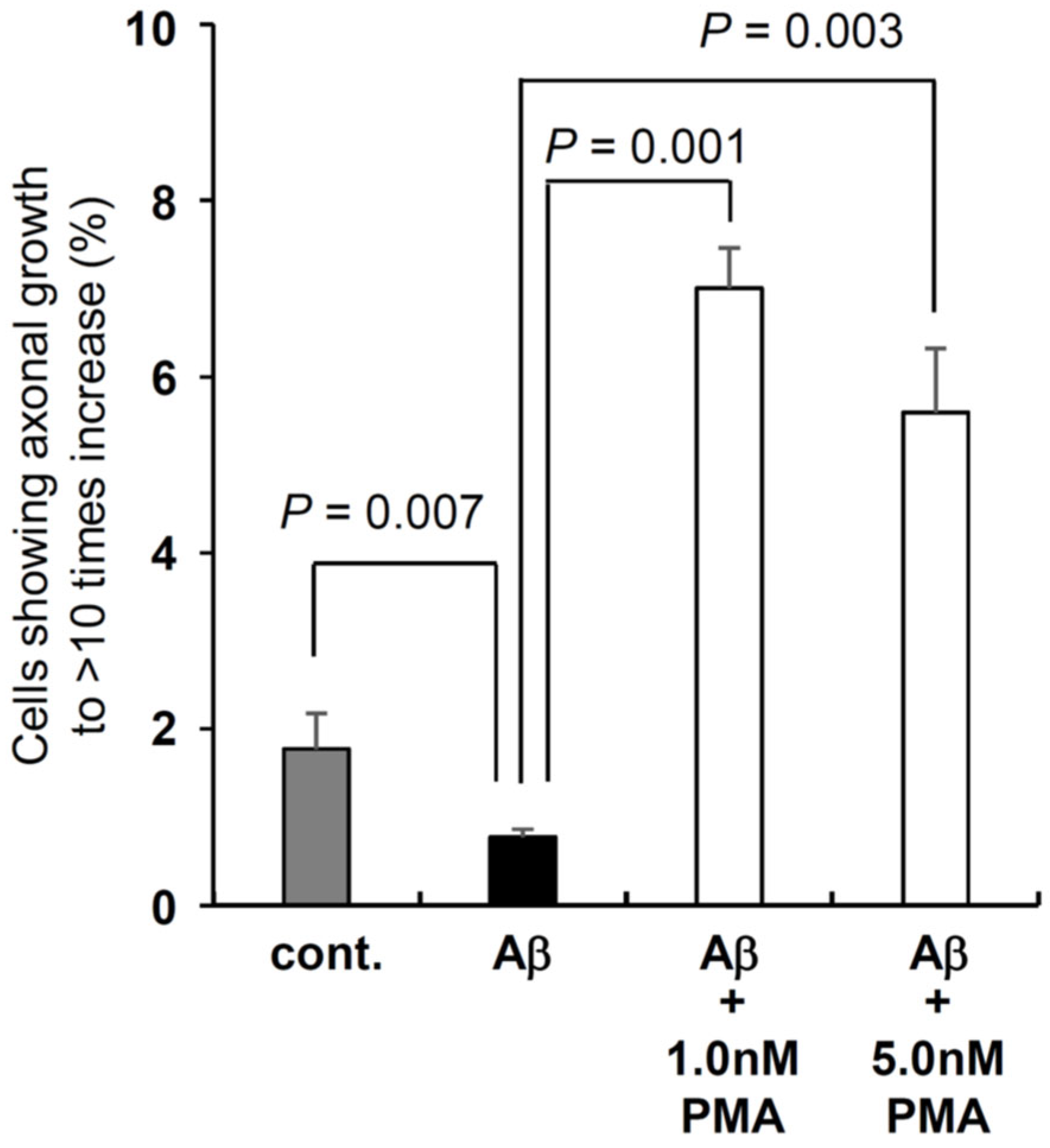

Next, we examined whether PMA shows the same ability in AD culture model. In AD research, various culture model of AD was already established [

32,

33]. In AD, β-amyloid (Aβ (1-42)) has been thought to be a main cause and the importance of Aβ (1-42) toxicity is widely recognized among AD researchers in the world [

34,

35,

36]; thus, we established the system using toxic Aβ (1-42) peptide-containing culture medium.

At 7 days after we started to culture SH-SY5Y cells, we added Aβ (1-42) at the concentration described in

Figure 6 and next day DMSO (control) and PMA was added. After 7 days, we counted the cells showing their neurite length was larger than >10-fold of cell body (soma) size. Compared to control, Aβ (1-42) suppressed the neurite growth and the percentage of the cells with the same neurite length as control was less than 50% (

Figure 6). PMA at 1.0 nM significantly increased the neurite length to approximately 4 times of control and 8 times of Aβ (1-42) treated cells. PMA at 5.0 nM also significantly increased the neurite length to 3 times of control and 6 times of Aβ (1-42) cells (

Figure 6). We tested other concentrations 0.2 nM, 0.5 nM, and 10.0 nM in the preliminary experiments, but these concentrations did not show significant difference from control even without Aβ (1-42). Thus, we show the result of only 1.0 nM and 5.0 nM in this experiment.

Figure 6.

PMA recovers neurite growth against the toxicity of β-amyloid (1-42) treatment. PMA concentration was adjusted to 1.0 nM and 5.0 nM. DMSO or PMA was added to culture medium on the next day of β-amyloid (1-42) treatment. β-amyloid (1-42) concentration was adjusted to 3.0 nM. Cell count was performed at 7 days after PMA treatment.

Figure 6.

PMA recovers neurite growth against the toxicity of β-amyloid (1-42) treatment. PMA concentration was adjusted to 1.0 nM and 5.0 nM. DMSO or PMA was added to culture medium on the next day of β-amyloid (1-42) treatment. β-amyloid (1-42) concentration was adjusted to 3.0 nM. Cell count was performed at 7 days after PMA treatment.

Totally,

Figure 4,

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 indicate that PMA can promote the prominent neurite growth in human neuronal cells even under the stressed and/or toxic condition with mTau-GFP protein aggregation inside cells (FTLD culture model) or existence of Aβ (1-42) outside of the cells (AD culture model).

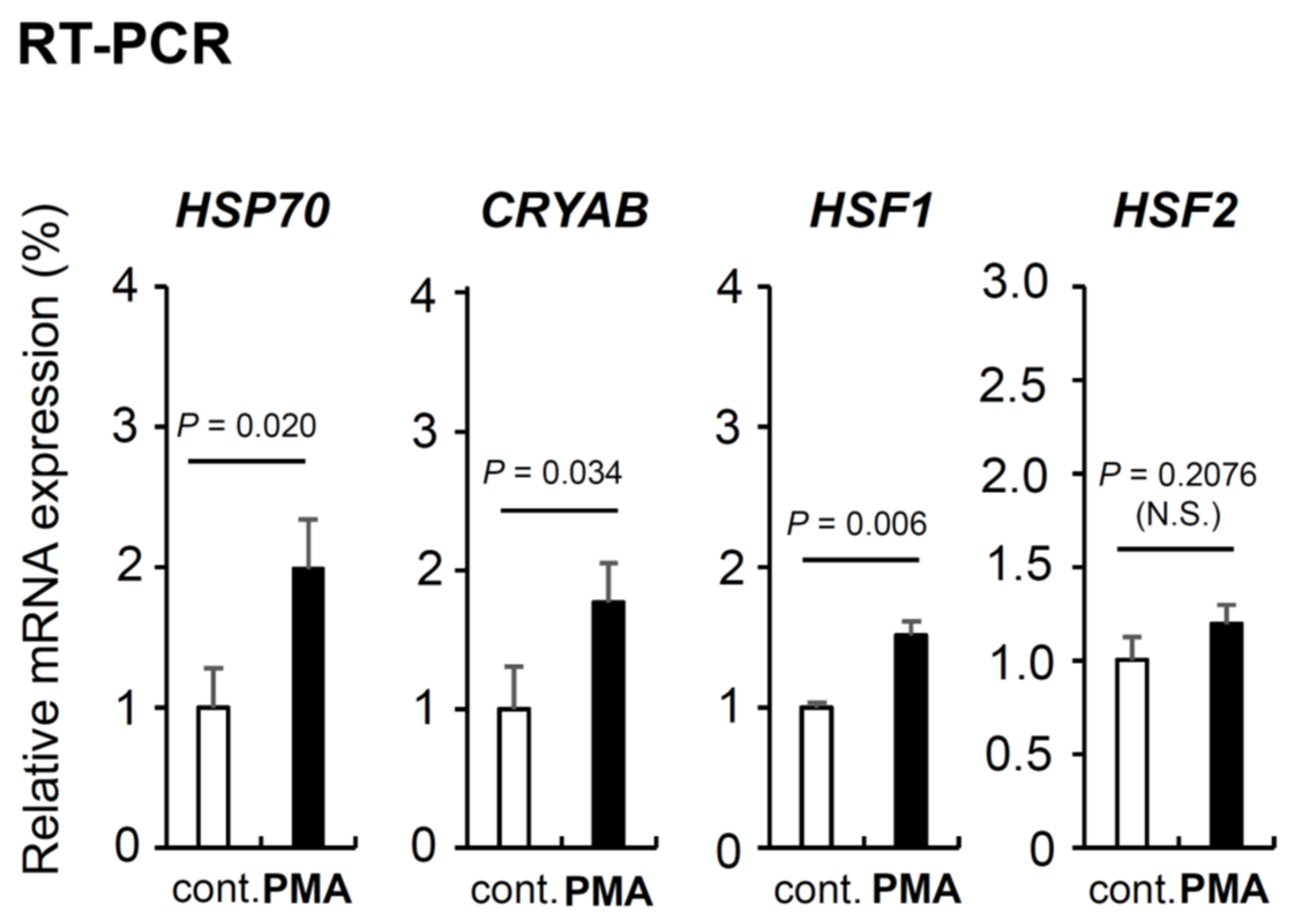

3.3. PMA Contributes to the Intracellular Proteostasis Maintenance by Increasing Genes and Proteins Expression

We showed that PMA suppresses aggregate formation of mTau-GFP in FTLD culture model and promotes neurite growth in FTLD and AD culture models in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6. Next, we examined the molecular mechanism of these PMA effects. Because PMA suppresses aggregate formation, we thought PMA induces the gene expression indispensable and/or important for intracellular protein homeostasis (proteostasis) [

1]. In previous studies, we discovered small HSP alphaB-crystallin (CRYAB), HSF1 and HSF2 are important for intracellular homeostasis maintenance [

6,

37]; thus, we examined the mRNA induction of

CRYAB,

HSF1,

HSF2, and well-known chaperone

HSP70 by semi-quantitative RT-PCR (

Figure 7). We prepared three independent cell dishes for control (DMSO-treated) and PMA-treated, respectively. PMA significantly upregulated the expression of three genes except

HSF2 we examined. Two HSPs,

HSP70 and

CRYAB, were prominently increased in PMA-treated SH-SY5Y neuronal cells.

HSF1 was also increased but

HSF2 was not significantly increased (

Figure 7)

Figure 7.

PMA effect on the expression of genes essential for the intracellular protective mechanisms. PMA effect on mRNA expression of four intracellular homeostasis maintaining genes (HSP70, CRYAB, HSF1, and HSF2) identified by Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis. S18 expression was examined as the internal control gene. Raw blot picture is shown in Figure S2.

Figure 7.

PMA effect on the expression of genes essential for the intracellular protective mechanisms. PMA effect on mRNA expression of four intracellular homeostasis maintaining genes (HSP70, CRYAB, HSF1, and HSF2) identified by Semi-quantitative RT-PCR analysis. S18 expression was examined as the internal control gene. Raw blot picture is shown in Figure S2.

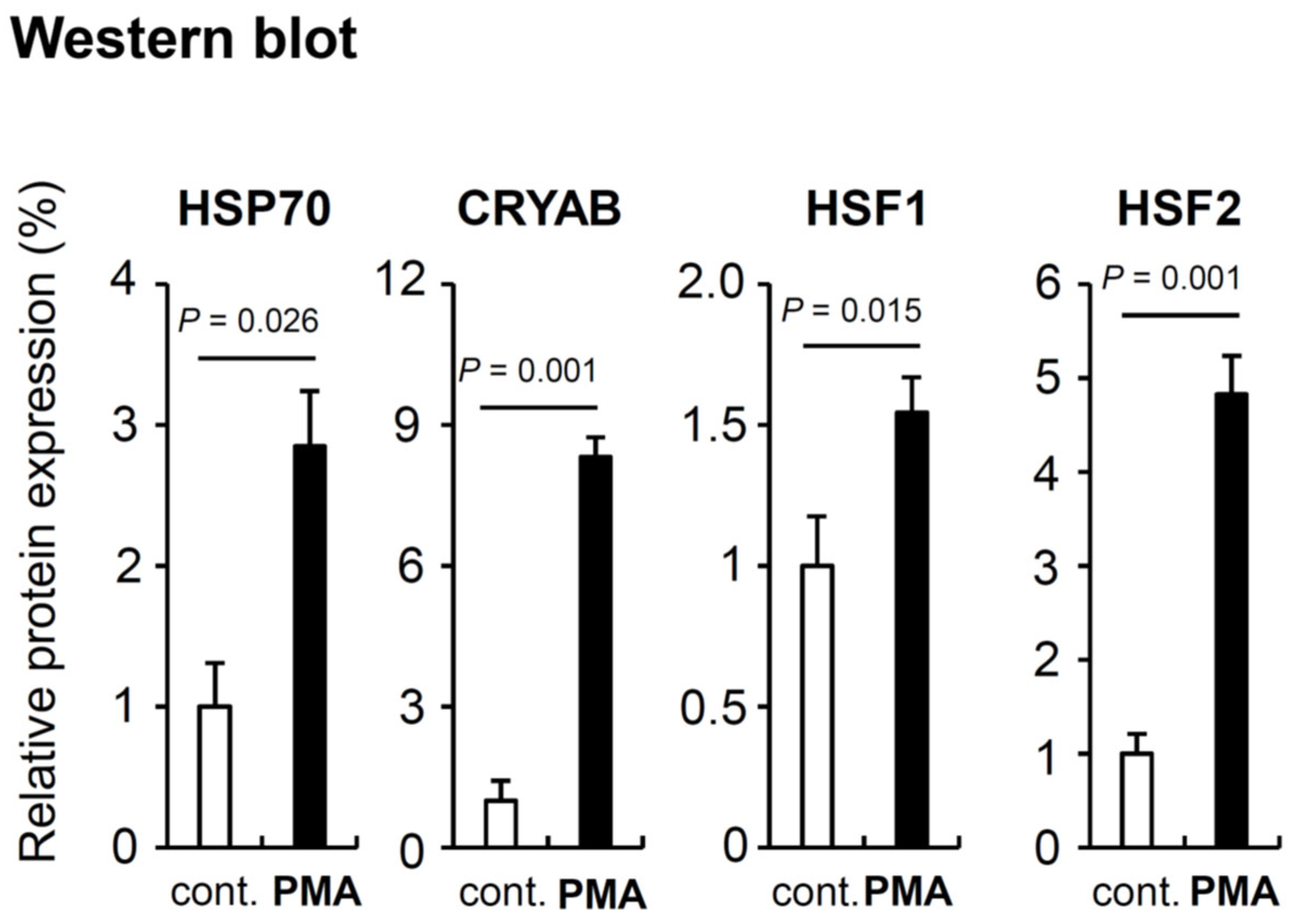

We also performed Western blot analysis using the proteins from the same cells (

Figure 8). Surprisingly, the results were partially but importantly different from RT-PCR. All four gene products were increased by PMA addition. HSP70, CRYAB, and HSF2 showed prominent increase. HSP70 was increased to 3 times, CRYAB was to 8 times, and HSF2 was to 5 times. HSF1 showed only to 1.5 times increase but this was also significant. All four genes and their products have roles in protecting cells and maintenance of cell survival against some stresses and dangers.

HSP70 and

CRYAB are target genes of HSF1, thus the induction of these two genes by HSF1 is probably involved in PMA effects [

1].

HSF2 genes was not significantly activated but in contrast its protein product was prominently increased. Compared with HSF1, the characters of HSF2 including activation mechanism, target genes, and functions are not revealed in detail [

38]. HSF2 probably contributes to PMA effects though the different mechanism from HSF1.

Figure 8.

PMA effect on the four intracellular defensive protein (HSP70, CRYAB, HSF1, and HSF2) expression shown by Western blot. β-actin was examined as the internal control protein. Cells were harvested at 7 days after DMSO (cont.) and PMA treatment. PMA concentration was 1.0 nM. Cells from one dish were divided to two tubes and one tube was used for RT-PCR and the other was used for Western blot. The graph was calculated from the original blots shown in Suppl.

Figure 2. The averaged values calculated from three control bands (No. 1-3) are indicated as 1.0.

P-values were calculated by student

t test. Raw blot picture is shown in

Figure S2.

Figure 8.

PMA effect on the four intracellular defensive protein (HSP70, CRYAB, HSF1, and HSF2) expression shown by Western blot. β-actin was examined as the internal control protein. Cells were harvested at 7 days after DMSO (cont.) and PMA treatment. PMA concentration was 1.0 nM. Cells from one dish were divided to two tubes and one tube was used for RT-PCR and the other was used for Western blot. The graph was calculated from the original blots shown in Suppl.

Figure 2. The averaged values calculated from three control bands (No. 1-3) are indicated as 1.0.

P-values were calculated by student

t test. Raw blot picture is shown in

Figure S2.

4. Discussion

In this paper, we showed that PMA has a possibility to be a strong candidate for the therapeutic drugs for NDDs.

PMA is well known old chemical compound independently discovered by two researchers in the years of 1967 and 1969 [

22,

23]; thus many papers referred to PMA were published in the past [

48,

49,

50] and in various fields and categories including chemistry, physics, biology, and medical science [

51,

52,

53].

We selected PMA through a lot of our experimental data and research of previous published papers, and launched this study. We already knew that PMA activates both NFATc2 and HSF1 through the PKC activation pathway [

54,

55], in addition, we discovered that NFATc2 and HSF1 have abilities to decrease the aggregate formation through the development of novel E3 ubiquitin ligase complex in the previous experiments [

6]. These experiences also made us select PMA. The other, PMA has been also used as a drug and applied to neuronal research for a long-time [

49,

56,

57], this fact also made us pay attention to this small chemical compound.

A biopharmaceutical company Rich Pharmaceuticals, Inc. named PMA as RP-323 and may proceed research whether PMA can be a therapeutic drug or not. Actually, this company obtained FDA approval to begin Phase 1/2 study in acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) patients in 2015 and subsequently announced the potential for using its drug RP-323 in the treatment of Hodgkin's lymphoma on the website in 2018 [

58,

59]. In the past, this company said to think that PMA may have an ability to cure NDDs on the old website. Except for us, there might be several researchers or research groups paying attention to PMA as a seed compound for NDDs therapeutic drug.

PMA has been used for neuronal research for a long-time, we must pay attention to these similar old studies indicating different conclusions from ours. For example, Liu and Chen reported that PMA inhibited axonal growth in N-18 mouse neuroblastoma cells, and Mattson also reported that PMA causes PKC overactivation and neurodegeneration in cultured human cortical neuron [

49,

57]. However, the concentration of PMA used in these studies is micromolar level, and this is 10 - 1000 times higher than that used in our experiments carried out at nanomolar concentration. Most of ours were performed at 1.0 nM, in addition, we found that PMA at the higher concentration than 5.0 nM exhibits increased toxicity for SH-SY5Y cells. Probably, this difference in PMA concentration used in each study caused the contrasted results. In addition, what cells were used, and whether the cells were mouse or human was also critically important. Several papers did not use neuronal cells despite neuronal research [

6]. For the novel drug development studies, we emphasize the usage of human neuronal cells is critically important.

Lastly, we want to talk about whether PMA is really tumor promoter or not. In old papers published before 1980’s, for example, most papers described as ‘Mouse skin tumor-promoting agent PMA’ ‘The phorbol esters and related diterpenes comprise the most potent class of tumor promoter. Of this class, PMA is the most active’ [

60,

61]. However, Van Duuren and his co-authors also said in the same paper ‘While tumor promotion is accompanied by epidermal hyperplasia and inflammation, these manifestations are in all likelihood not related to the mode of action of PMA [

60]. Dunphy and his co-authors also described ‘Tumor promoters are compounds which, although in themselves neither carcinogenic nor mutagenic, greatly accelerate tumor outgrowth in animals previously treated with a subthreshold dose of a carcinogen’ [

61]. Both groups referred to the possibility that PMA itself may not be tumor initiator and that PMA just plays a functional role.

Actually, in the present studies of skin tumor and skin carcinogenesis, a method ‘7,12-dimethylbenzanthracene (DMBA) / PMA two-stage chemical carcinogenesis protocol’ or UV irradiation is used [

62,

63,

64]. In detail, Fischer and her colleagues used 6- to 8-week-old mice and topically applied 100 μg of DMBA in 200 μL of acetone 2 days after shaving to the dorsal skin. This is the initiation step. Two weeks after initiation step, the mice were topically treated with 2.5 μg PMA in 200 μL acetone twice a week for a period of 30 weeks [

64]. In this protocol, mutagen inducing carcinogenesis is DMBA, not PMA [

65]. PMA is pleiotropic chemical but shows pro-inflammatory effects crucial for tumor promotion [

65].

It is required to confirm whether PMA has an ability to induce carcinogenesis by itself using animals. Through the animal experiments, we must show to what extent PMA is safe. When we improve the safety of PMA, we can proceed to the next step.

Author Contributions

N.H. designed the experiments, directed research, and wrote the paper. Y.T., A.O., K-I.O., and T.H. performed the experiments. In detail, Y.T. performed preliminary and most experiments including cell culture maintenance, mRNA and protein expression analysis. A.O., and K-I.O. performed mRNA and protein experiments and analysis. T.H. performed cell culture condition tests and establishment of neuronal cell differentiation system. T.H. summarized drug information and performed drug concentration determining tests and culture experiments using drugs. K-I., and N.H. wrote additional manuscript. All authors read and discussed the manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by Okayama University Translational Research Network Program (A33 N.H.) funded by the Japan Agency of Medical Research (AMED), Nipponham Foundation for the Future of Food (2016-B-3 N.H.), Takeda Science Foundation (23009 N.H.), and JSPS KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientist (B) (23700512 N.H.), Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) (25430090N.H., 17K07136N.H., and 22K06044N.H. and Shigeru Kakuta)

Acknowledgments

N.H. thanks Tomohiro Miyasaka for critical reading of the draft of manuscript and important advice. N.H., Y.T. and A.O. thank Yoichi Mizukami and Center Staffs of Yamaguchi University Center for Gene Research for the support of our research. N.H. also thanks Shigeru Kakuta, Michiko Mukai, Takao Kitagawa, Shuji Noguchi, and Yasuhiro Kuramitsu for encouragement and comments. N.H. also thanks the students of Yamaguchi Kojo School of Nursing, Ube School of Nursing, and Yamaguchi University School of Medicine. N.H. dedicates this paper to Norio Hayashida (1932-2018), Masaharu Hayashida (1945-2020), and his dear father Daisaku Hayashida (1942-2022).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare we have no conflict of interest.

References

- Balch, W.E.; Morimoto, R.I.; Dillin, A.; Kelly, J.W. Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science 2008, 319, 916–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klaips, C.L.; Jayaraj, G.G.; Hartl, F.U. Pathways of cellular proteostasis in aging and disease. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, C.A.; Akimov, S.S. Human-induced pluripotent stem cells: potential for neurodegenerative diseases. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, R17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brehme, M.; Voisine, C.; Rolland, T.; Wachi, S.; Soper, J.H.; Zhu, Y.; Orton, K.; Villella, A.; Garza, D.; Vidal, M.; Ge, H.; Morimoto, R.I. A chaperome subnetwork safeguards proteostasis in aging and neurodegenerative disease. Cell Rep. 2014, 9, 1135–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampinga, H.H.; Bergink, S. Heat shock proteins as potential targets for protective strategies in neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2016, 15, 748–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashida, N.; Fujimoto, M.; Tan, K.; Prakasam, R.; Shinkawa, T.; Li, L.; Ichikawa, H.; Takii, R.; Nakai, A. Heat shock factor 1 ameliorates proteotoxicity in cooperation with the transcription factor NFAT. EMBO J. 2010, 20, 3459–3469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayashida, N. Non-Hsp genes are essential for HSF1-mediated maintenance of whole body homeostasis. Exp. Anim. 2015, 64, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, J.; McCaffrey, P.G.; Miner, Z.; Kerppola, T.K.; Lambert, J.N.; Verdine, G.L.; Curran, T.; Rao, A. The T-cell transcription factor NFATp is a substrate for calcineurin and interacts with Fos and Jun. Nature 1993, 365, 352–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, A.; Luo, C.; Hogan, P.G. Transcription factors of the NFAT family: regulation and function. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1997, 15, 707–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyakh, L.; Ghosh, P.; Rice, N.R. Expression of NFAT-family proteins in normal human T cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1997, 17, 2475–2484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deguchi, M.; Iizuka, T.; Hata, Y.; Nishimura, W.; Hirao, K.; Yao, I.; Kawabe, H.; Takai, Y. PAPIN. A novel multiple PSD-95/Dlg-A/ZO-1 protein interacting with neural plakophilin-related armadillo repeat protein/delta-catenin and p0071. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275, 29875–29880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeung, M.L.; Tam, T.S.; Tsang, A.C.; Yao, K.M. Proteolytic cleavage of PDZD2 generates a secreted peptide containing two PDZ domains. EMBO Rep. 2003, 4, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- den Engelsman, J.; Keijsers, V.; de Jong, W.W.; Boelens, W.C. The small heat-shock protein alpha B-crystallin promotes FBX4-dependent ubiquitination. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 4699–4704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, D.I.; Barbash, O.; Kumar, K.G.; Weber, J.D.; Harper, J.W.; Klein-Szanto, A.J.; Rustgi, A.; Fuchs, S.Y.; Diehl, J.A. Phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitination of cyclin D1 by the SCF(FBX4- alphaB crystallin) complex. Mol. Cell 2006, 24, 355–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buée, L.; Bussière, T.; Buée-Scherrer, V.; Delacourte, A.; Hof, P.R. Tau protein isoforms, phosphorylation and role in neurodegenerative disorders. Brain Res. Brain Res. Rev. 2000, 33, 95–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyasaka, T.; Morishima-Kawashima, M.; Ravid, R.; Heutink, P.; van Swieten, J.C.; Nagashima, K.; Ihara, Y. Molecular analysis of mutant and wild-type tau deposited in the brain affected by the FTDP-17 R406W mutation. Am. J. Pathol. 2001, 158, 373–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Souza, I.; Schellenberg, G.D. Regulation of tau isoform expression and dementia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1739, 104–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyman, B.T.; Augustinack, J.C.; Ingelsson, M. Transcriptional and conformational changes of the tau molecule in Alzheimer's disease. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2005, 1739, 150–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kar, A.; Kuo, D.; He, R.; Zhou, J.; Wu, J.Y. Tau alternative splicing and frontotemporal dementia. Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 2005, Suppl 1, S29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Swieten, J.; Spillantini, M.G. 2007. Hereditary frontotemporal dementia caused by Tau gene mutations. Brain Pathol. 2007, 17, 63–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, Y.; Otsuyama, K.I.; Hayashida, N. Cell Cycle Regulation by Heat Shock Transcription Factors. Cells 2022, 11, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hecker, E. Phorbol esters from croton oil. Chemical nature and biological activities. Naturwissenschaften 1967, 54, 282–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Duuren, B.L. Tumor-promoting agents in two-stage carcinogenesis. Prog. Exp. Tumor Res. 1969, 11, 31–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Takei, N.; Endo, Y. Ca2+ ionophore-induced apoptosis on cultured embryonic rat cortical neurons. Brain Res. 1994, 652, 65–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwag, B.J.; Canzoniero, L.M.; Sensi, S.L.; Demaro, J.A.; Koh, J.Y.; Goldberg, M.P.; Jacquin, M.; Choi, D.W. Calcium ionophores can induce either apoptosis or necrosis in cultured cortical neurons. Neuroscience 1999, 90, 1339–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrigan, P.J.; Sonawane, B.; Butler, R.N.; Trasande, L.; Callan, R.; Droller, D. Early Environmental Origins of Neurodegenerative Disease in Later Life. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 1230–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberson, E.D.; Hesse, J.H.; Rose, K.D.; Slama, H.; Johnson, J.K.; Yaffe, K.; Forman, M.S.; Miller, C.A.; Trojanowski, J.Q.; Kramer, J.H.; Miller, B.L. Frontotemporal dementia progresses to death faster than Alzheimer disease. Neurology 2005, 65, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fournier, A.E.; Strittmatter, S.M. Repulsive factors and axon regeneration in the CNS. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2001, 11, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamazaki, Y.; Hozumi, Y.; Kaneko, K.; Fujii, S.; Goto, K.; Kato, H. Oligodendrocytes: facilitating axonal conduction by more than myelination. Neuroscientist 2010, 16, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Smith, D.L.; Meriin, A.B.; Engemann, S.; Russel, D.E.; Roark, M.; Washington, S.L.; Maxwell, M.M.; Marsh, L.J.; Thompson, L.M.; Wanker, E.E.; Young, A.B.; Housman, D.E.; Bates, G.P.; Michael, Y.; Sherman, M.Y.; Kazantsev, A.G. A potent small molecule inhibits polyglutamine aggregation in Huntington's disease neurons and suppresses neurodegeneration in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005, 102, 892–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, H.; Rubinsztein, D.C. Control of autophagy as a therapy for neurodegenerative disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2012, 8, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klein, W.L.W.B.; Stine Jr., W. B.; Teplowc, D.B. 2004. Small assemblies of unmodified amyloid -protein are the proximate neurotoxin in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2004, 25, 569–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldstein, L.S.B.; Reyna, S.; Woodruff, G. 2015. Probing the secrets of Alzheimer’s disease using human-induced pluripotent stem cell technology. Neurotherapeutics 2015, 12, 121–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, M.E.; Ahuja, V.; Binder, L.I.; Kuret, J. Ligand-Dependent Tau Filament Formation: Implications for Alzheimer's Disease Progression. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 14851–14859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunderland, T.; Linker, G.; Mirza, N.; Putnam, K.T.; Friedman, D.L.; Kimmel, L.H.; Bergeson, J.; Manetti, G.J.; Zimmermann, M.; Tang, B.; Bartko, J.J.; Cohen, R.M. Decreased β-amyloid1-42 and increased tau levels in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with Alzheimer disease. JAMA 2003, 289, 2094–2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballatore, C.; Lee, V.M.Y.; Trojanowski, J.Q. Tau-mediated neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007, 8, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinkawa, T.; Tan, K.; Fujimoto, M.; Hayashida, N.; Yamamoto, K.; Takaki, E.; Takii, R.; Prakasam, R.; Inouye, S.; Mezger, V.; Nakai, A. Heat shock factor 2 is required for maintaining proteostasis against febrile range thermal stress and polyglutamine aggregation. Mol. Biol. Cell 2011, 22, 3571–3583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokunaga, Y.; Otsuyama, K.I.; Kakuta, S.; Hayashida, N. Heat Shock Transcription Factor 2 Is Significantly Involved in Neurodegenerative Diseases, Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Cancer, Male Infertility, and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder: The Novel Mechanisms of Several Severe Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Rodríguez, C.; Rao, A. Requirement for integration of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate and calcium pathways is preserved in the transactivation domain of NFAT1. Eur. J. Immunol. 2000, 30, 2432–2436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homma, S.; Jin, X.; Wang, G.; Tu, N.; Min, J.; Yanasak, N.; Mivechi, N.F. Demyelination, astrogliosis, and accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins, hallmarks of CNS disease in hsf1-deficient mice. J. Neurosci. 2007, 27, 7974–7986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.Z.; Tsokos, G.C.; Kiang, J.G. Overexpression of HSP-70 inhibits the phosphorylation of HSF1 by activating protein phosphatase and inhibiting protein kinase C activity. FASEB J. 1998, 12, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaldjian, E.; McCarthy, S.A.; Sharrow, S.O.; Littman, D.R.; Klausner, R.D.; Singer, A. Nonequivalent effects of PKC activation by PMA on murine CD4 and CD8 cell-surface expression. FASEB J. 1988, 2, 2801–2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, B.; Zhong, R.; Soncin, F.; Stevenson, M.A.; Calderwood, S.K. Transcriptional activity of heat shock factor 1 at 37 degrees C is repressed through phosphorylation on two distinct serine residues by glycogen synthase kinase 3 and protein kinases Calpha and Czeta. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 18640–18646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loh, C.; Shaw, K.T.; Carew, J.; Viola, J.P.; Luo, C.; Perrino, B.A.; Rao, A. Calcineurin binds the transcription factor NFAT1 and reversibly regulates its activity. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 10884–10891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Cozar, F.J.; Okamura, H.; Aramburu, J.F.; Shaw, K.T.; Pelletier, L.; Showalter, R.; Villafranca, E.; Rao, A. Two-site interaction of nuclear factor of activated T cells with activated calcineurin. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 23877–23883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Yaseen, N.R.; Hogan, P.G.; Rao, A.; Sharma, S. Phosphorylation of the transcription factor NFATp inhibits its DNA binding activity in cyclosporin A-treated human B and T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 20653–20659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmel, E.A.; Verweij, C.L.; Durand, D.B.; Higgins, K.M.; Lacy, E.; Crabtree, G.R. Cyclosporin A specifically inhibits function of nuclear proteins involved in T cell activation. Science 1989, 246, 1617–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dlugosz, A.A.; Tapscott, S.J.; Holtzer, H. Effects of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate on the differentiation program of embryonic chick skeletal myoblasts. Cancer Res. 1983, 43, 2780–2789. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, A.Y.; Chen, K.Y. Differential effects of the tumor promoter phorbol-12- myristate-13-acetate on the morphological and biochemical differentiation of N-18 mouse neuroblastoma cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 1985, 125, 387–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basta, S.; Knoetig, S.; Summerfield, A.; McCullough, K.C. Lipopolysaccharide and phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate both impair monocyte differentiation, relating cellular function to virus susceptibility. Immunology 2001, 103, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhuri, S.; Raha, S. Inhibition and stimulation of growth of Entamoeba histolytica in culture: association with PKC activity and protein phosphorylation. Exp. Parasitol. 2000, 95, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basok, S.S.; Schepetkin, I.A.; Khlebnikov, A.I.; Lutsyuk, A.F.; Kirichenko, T.I.; Kirpotina, L.N.; Pavlovsky, V.I.; Leonov, K.A.; Vishenkova, D.A.; Quinn, M.T. Synthesis, Biological Evaluation, and Molecular Modeling of Aza-Crown Ethers. Molecules 2021, 26, 2225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lactoferrin modified by hypohalous acids: Partial loss in activation of human neutrophils.

- Grigorieva, D.V.; Gorudko, I.V.; Grudinina, N.A.; Panasenko, O.M.; Semak, I.V.; Sokolov, A.V.; Timoshenko, A.V. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 195, 30–40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burry, R.W. PKC activators (phorbol ester or bryostatin) stimulate outgrowth of NGF-dependent neurites in a subline of PC12 cells. J. Neurosci. Res. 1998, 53, 214–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damascena, H.L.; Silveira, W.A.A.; Castro, M.S.; Fontes, W. Neutrophil Activated by the Famous and Potent PMA (Phorbol Myristate Acetate). Cells 2022, 11, 2889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gonzales, R.A.; Greger, P.H. Jr; Baker, S.P.; Ganz, N.I.; Bolden, C.; Raizada, M.K.; Crews, F.T. Phorbol esters inhibit agonist-stimulated phosphoinositide hydrolysis in neuronal primary cultures. Brain Res. 1987, 465, 59–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattson, M.P. Evidence for the involvement of protein kinase C in neurodegenerative changes in cultured human cortical neurons. Exp. Neurol. 1991, 112, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Rich Pharmaceuticals obtains FDA approval to begin Phase 1/2 study in AML

and MDS patients. News-Medical.net. 2015, Dec 28. (https://www.news-medical.net/news/20151228/Rich-

Pharmaceuticals-obtains-FDA-approval-to-begin-Phase-12-study-in-AML-and-MDS-patients.aspx#).

- Rich Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Rich Pharmaceuticals' Study Drug RP-323 (TPA) is a Potential Therapeutic Agent for the Treatment of Hodgkin's Lymphoma. 2018, Mar 14. (https://www.globenewswire.com/en/news-release/2018/03/14/1422455/0/en/Rich-Pharmaceuticals-Study-Drug-RP-323-TPA-is-a-Potential-Therapeutic-Agent-for-the-Treatment-of-Hodgkin-s-Lymphoma.html).

- Van Duuren, B.L.; Sivak, A.; Segal, A.; Seidman, I.; Katz, C. Dose-response studies with a pure tumor-promoting agent, phorbol myristate acetate. Cancer Res. 1973, 33, 2166–2172. [Google Scholar]

- Dunphy, W.G.; Delclos, K.B.; Blumberg, P.M. Characterization of specific binding of [3H]phorbol 12,13-dibutyrate and [3H]phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate to mouse brain. Cancer Res. 1980, 40, 3635–3641. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Prescott, S.M. Many actions of cyclooxygenase-2 in cellular dynamics and in cancer. J. Cell Physiol. 2002, 190, 279–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, S.M.; Lo, H.H.; Gordon, G.B.; Seibert, K.; Kelloff, G.; Lubet, R.A.; Conti, C.J. Chemopreventive activity of celecoxib, a specific cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor, and indomethacin against ultraviolet light-induced skin carcinogenesis. Mol. Carcinog. 1999, 25, 231–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.M.; He, G.; Fischer, S.M. Lack of expression of the EP2 but not EP3 receptor for prostaglandin E2 results in suppression of skin tumor development. Cancer Res. 2005, 65, 9304–9311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, S.J.; Ng, B.Y.; Filler, R.B.; Lewis, J.; Glusac, E.J.; Hayday, A.C.; Tigelaar, R.E.; Girardi, M. Characterizing tumor-promoting T cells in chemically induced cutaneous carcinogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 6770–6775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).