1. Introduction

Blood type is a well-studied and well-established risk factor of a wide variety of conditions and may be considered when conducting research on different disease processes. Known effects of blood type in a disease process include thromboembolism, gastric ulcers, and malignancy, among others [

1,

2,

3]. In the domain of infectious disease, blood type is a well-known risk factor [

4] that correlates to clinical outcomes in parasitic, bacterial, and viral infections [

5,

6,

7,

8]. It has been postulated that human blood type may play a role in altering a patient’s susceptibility to COVID-19 infection.

The role of blood type is multifaceted in the overall process of infection [

4]. For viral infections in particular, glycoproteins found on the surface of red blood cells serve as receptors for exogenous ligands that allow viral entry into the host cell [

9]. In respect to SARS-CoV-2, the biochemical mechanism of entry is facilitated by viral S-protein binding to the metallocarboxyl peptidase angiotensin receptor (ACE-2) [

10]. It is theorized that this viral entry is influenced by monoclonal or natural human anti-A antibodies specifically inhibiting the ACE-2 dependent binding of the viral S protein. This process is believed to lead individuals with non-A blood types (type O and B), which produce anti-A antibodies, to exhibit less susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection due to the inhibitory effect of anti-A antibodies [

11].

Furthermore, a meta-analysis done by Wang et al. [

12] describing the clinical correlation between blood type and COVID-19 infection, found that type A and AB are more susceptible to infection, while type O is less susceptible. It has also been demonstrated that rhesus (Rh) blood group status might play a protective role in COVID-19 infection, specifically in that Rh negative blood groups may be associated with a lower risk of COVID-19 infection and severity [

13]. Additional studies have found that Rh positivity may predispose an individual to a heightened risk [

14]. As the pattern of blood type is geographically heterogenic, blood type is believed to play a role in epidemiological distribution of the pandemic [

15]. These observed geographical trends in COVID-19 infection in association with blood type have been well documented [

16]. Contrarily, other studies have found no significant association between blood group and COVID-19 associated infection, severity, mortality, nor hematological or radiological abnormalities [

17,

18]. To our knowledge, there has not yet been an analysis of the association between blood type and COVID-19 in a South Florida population.

ABO blood type may have an effect on the expression of biomarkers which indicate COVID-19 infection severity. There is significant evidence highlighting the role of inflammatory response to COVID-19 infection as a driving factor in disease outcome [

19]. Rapid viral replication of SARS-CoV-2 results in cellular destruction causing subsequent recruitment of macrophages and monocytes inducing the release of both cytokines and chemokines [

20]. The release of cytokines and chemokines which activate immune responses by signaling various immune cells potentially leads to cytokine storm [

21]. Evidence suggests that elevations in inflammatory markers such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), serum ferritin, procalcitonin (PCT), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP) are significantly associated with severity of COVID-19 infection [

22,

23,

24].

The objectives of this study were to (1) investigate the association between human blood type and COVID-19 infection in both inpatient and longitudinal populations and (2) identify the association between blood type and severity of COVID-19 infection via levels of cellular biomarkers of severe infection in hospitalized individuals at our institution in South Florida.

2. Methods

2.1. Retrospective Study Design and Participants

We conducted an IRB-approved (ID# 20210025) single-center retrospective analysis of admitted patients seen from January 1, 2020, to March 31, 2021 at the University of Miami Hospital Emergency Department (ED) who tested positive for COVID-19 infection regardless of reason for admission and had a documented ABO blood type. Overall, 2,741 COVID-19 positive patient charts were screened; 2,072 individuals were excluded due to lack of blood type data on file, yielding a total of 669 patients included in our statistical analyses. The following were also acquired from electronic medical records: demographics (sex, age), respiratory status (baseline, minimum and maximum SpO2; ventilator use; diagnosis of pneumonia), and clinical biomarker test results (presence of abnormal monocytes, lymphocytes, megakaryocytes, and neutrophils on blood smear, percent and absolute neutrophils, monocytes, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and basophils, D-dimer, troponin, CRP, ferritin, LDH, hemoglobin, hematocrit, MCV, MCH, MCHC, RDW, platelets, AST, ALT, ALP, creatinine, IL-6, IL-6>35 pg/mL, creatinine kinase, PCT, PCT of 0.5-2.0 ng/mL, PCT>2.0 ng/mL, hemoglobinuria, hematuria, and age of time of death as appropriate). If multiple values (i.e., from complete blood count) were inputted in a patient’s chart during their hospital visit, the most abnormal (most maximal or minimal) value was recorded for our study. Outcomes were measured as follows: development of COVID-19 pneumonia, ventilator use, diagnosis of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), and associated mortality.

2.2. Inpatient Cohort Statistical Analysis

For each blood type, the COVID-19 outcome rates and 95% confidence intervals were calculated to make comparisons between blood types with each of the clinical outcomes of interest. Comparisons were made using Chi-squared tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous values (a = 0.05 significance level). All analyses were performed in R version 4.1.1.

2.3. Longitudinal Cohort Study Design and Participants

We included 185 participants enrolled in our IRB-approved (#20201026), longitudinal SARS-CoV-2 immunity study (“CITY”) at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine. This longitudinal cohort (Table 3) consists of unique COVID positive and negative individuals that were not part of the 2,741 originally screen patients. Following written informed consent, participants answered a demographic and health history questionnaire, which included disclosure of previous SARS-CoV-2 infection and blood type. All participants agreed to sample banking and consented to use in future research. For those with an unknown blood type at entry, typing was performed according to manufacturer instructions (Eldon Biologicals A/S) upon sample availability.

2.4. Longitudinal Cohort Statistical Analysis

Chi-squared tests were used to examine associations between COVID status and ABO or Rh blood grouping. All prospective analyses and figures were generated in R Studio.

3. Results

3.1. Inpatient Cohort Results

Our inpatient cohort had a mean age of 53.6 (± 17.9) years with 48% males (n=321) and 52% females (n=348). The most common blood type was O (52.6%, n=352), followed by A (35.3%, n=236), B (10.8%, n=72), and AB (1.3%, n=9), which varies from the normal general U.S. population distribution (

Table 1) [

25]. 52.6% (Confidence interval (CI): 47.2-57.9%) of patients with blood type O were female and 47.4% (CI: 42.1-52.8%) were male. 50.8% (CI: 44.3-57.4%) of patients with blood type A were female and 49.2% (CI: 42.6-55.7%) were male (

Table 1). 66.7% (CI: 29.9-92.5%) of blood type AB patients were female and 33.3% (CI: 7.49-70.1%) were male; 51.4% (CI: 39.3-63.3%) of blood type B individuals were female and 48.6% (CI: 36.7-60.7%) were male (

Table 1). 86.6% of patients with blood type O were Rh positive (n=305); 13.4% (n=47) were Rh negative. 88.6% of patients (n=209) with blood type A were Rh positive; 11.4% were Rh negative (n=27). 100% of patients with blood type AB (n=9) as well as blood type B (n=72) were Rh positive. All patients in this study presented to the ED with similar SpO

2, with a mean SpO

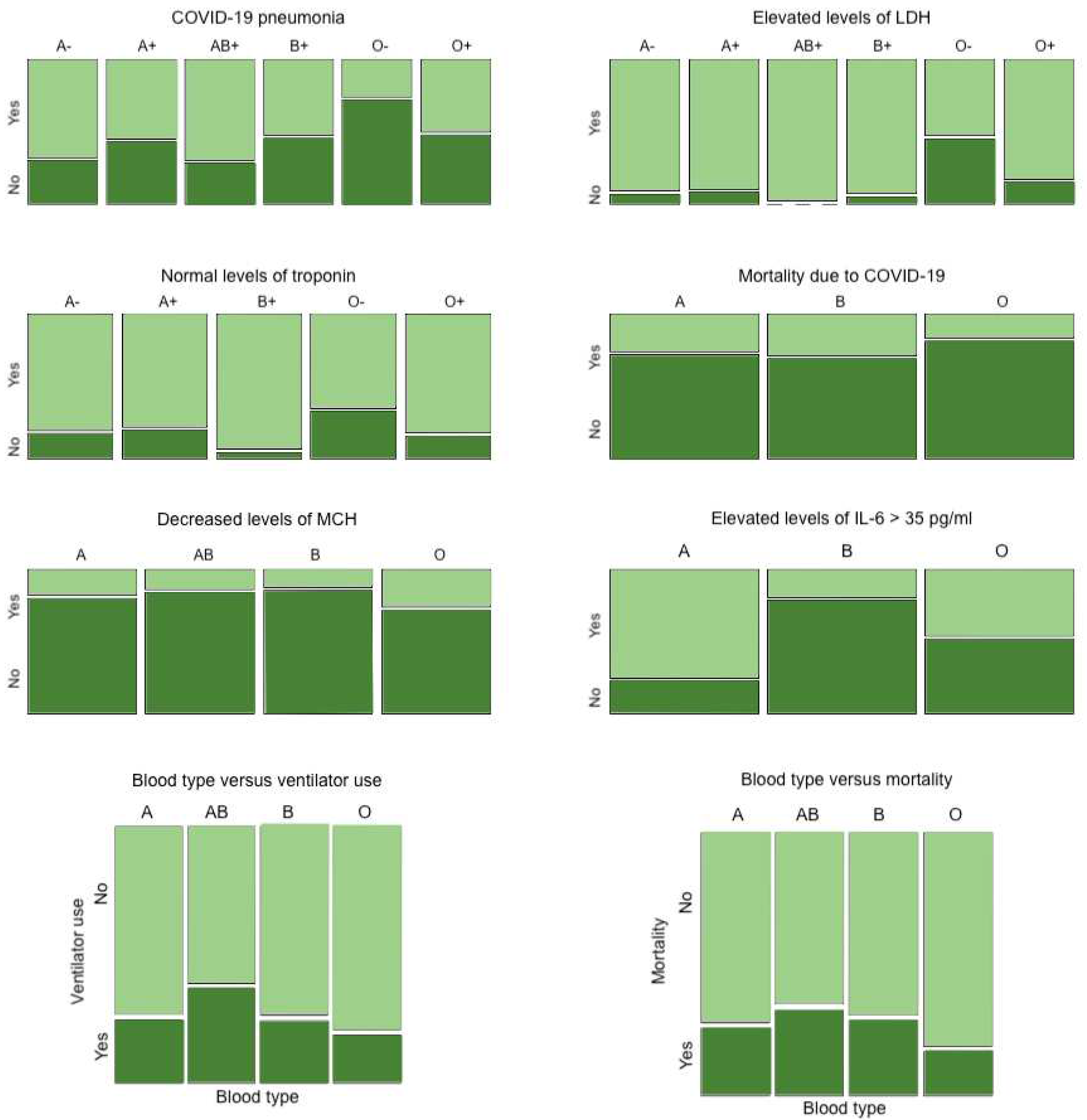

2 of 95.79% (SD, 0.47). Of the investigated outcomes, blood type O- patients demonstrated less risk of developing COVID-19 pneumonia (26.7% for O- vs. 69.2% for type A-, 56.5% for A+, 71.4% for AB+, 53.7% for B+, 51.5% for O+, p-value = 0.003 via Chi-squared test) (

Table 2). Blood type O, Rh negative or positive, exhibited decreased mortality due to COVID-19 infection when compared to other types (17.0% mortality for O vs. 26.3% for A, 29.2% for B, p-value = 0.012 via Chi-squared test) (

Figure 1). Association of blood type with biomarkers of severe COVID-19 infection were also assessed for significant difference among blood groups including Rh factor. O- demonstrated less elevated levels of LDH than did other blood types (p-value = 0.001, ANOVA) (

Figure 1). O- demonstrated a higher frequency of clinically accepted baseline levels of troponin (<0.04 ng/mL) (p-value = 0.026, ANOVA) (

Figure 1). Therefore, O- had less biomarkers indicative of a severe COVID-19 infection, which may coincide with the lower mortality rate of blood type O-.

Additional findings regarding general non-Rh-factor blood type are as follows: blood type O (Rh negative or positive) exhibited decreased levels of MCH (p-value = 0.006 via Chi-squared test) (

Figure 1), and blood type A exhibited elevated levels of IL-6 (> 35 pg/ml) in comparison to type B or O (p-value <0.001 via Chi-squared test) (

Figure 1).

Figure 1 depicts the reduced usage of ventilators and lower mortality rates in patients with blood type O in comparison to those with other blood types.

There were no statistically significant differences between different ABO blood groups nor Rh factor in levels of other biomarkers of COVID-19 infection severity analyzed, which included the presence of abnormal monocytes, lymphocytes, megakaryocytes, and neutrophils on blood smear, percent and absolute neutrophil, monocyte, lymphocytes, eosinophils, and basophils, D-dimer, CRP, hemoglobin, hematocrit, MCV, MCHC, RDW, platelets, AST, ALT, ALP, creatinine, creatinine kinase, PCT, PCT of 0.5-2.0 ng/mL, PCT >2.0 ng/mL, hemoglobinuria, and hematuria (data not depicted in figures/tables).

3.2. Longitudinal Cohort Results: Cohort Characteristics

Among the participants included in this analysis (n = 185), 53% were healthcare workers and 47% were at-risk community controls (

Table 3) [

26]. The median age was 51 ± 16.54 with 56.2% (104/185) female and 43.8% (81/185) male participants. 85.9% (157/185) of participants identified as white and 63.2% (117/185) as non-Hispanic. 54% were COVID-19 negative at baseline, while approximately 46% entered with a prior history of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Including breakthrough or re-infection cases (95/185 (51.4%)), 76.2% (141/185) participants included in this analysis had experienced a positive COVID-19 test during their time on-study. Nearly all had been vaccinated (95.1% [176/185]), with most reporting primary vaccination with Pfizer (57.8% (107/185)), followed by Moderna (33% [61/185]), and Johnson & Johnson (4.3% [8/185]). 8 participants (4.3%) were unvaccinated.

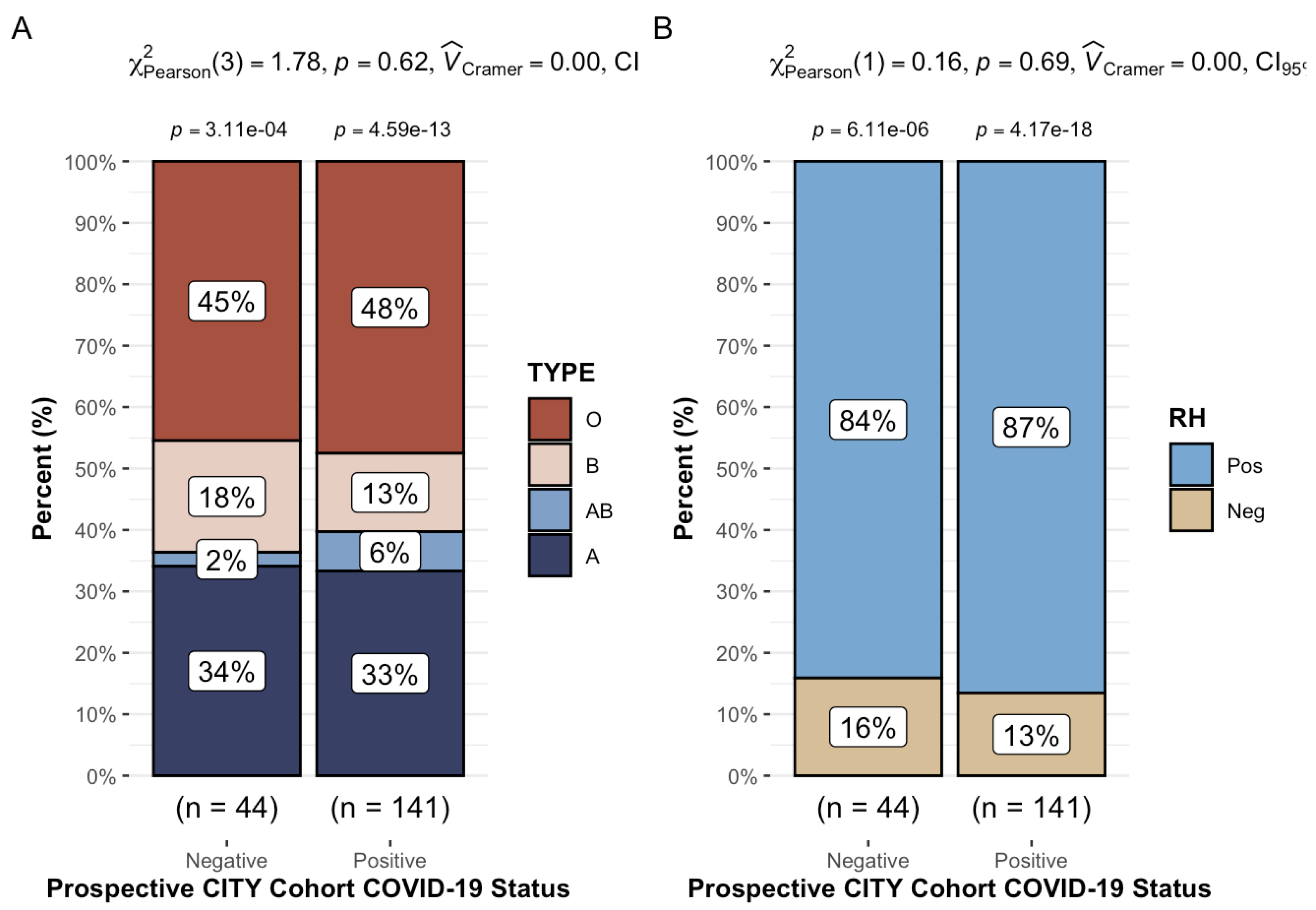

3.3. Longitudinal Cohort Results: ABO/Rh blood typing and COVID-19 infection

47% (87/185) of our longitudinal cohort was ABO blood grouping type O, with 33.5% type A, and 14.1% and 5.4% B and AB, respectively. Additionally, 85.9% were Rh+. These observations were consistent across both sub-groups analyzed [HCW vs. CTL] (

Table 4). As seen in

Figure 2, we found no significant association between COVID status (infection vs. non-infection) and ABO (Chi-squared test [3,

N = 185] = 1.8,

p = 0.6) or Rh (Chi-squared test [1,

N = 185] = 0.16,

p = 0.7) blood typing.

4. Discussion

The goals of this study were to (1) investigate the association between blood type and COVID-19 infection in both inpatient and longitudinal populations and (2) identify the association between blood type and severity of COVID-19 infection via levels of cellular biomarkers of severe infection in an inpatient setting at our institution in South Florida. We found that blood type O- was associated with decreased risk of both developing COVID-19 pneumonia and COVID-19 related mortality. Our data also illustrated that blood type O (Rh negative or positive) is associated with decreased elevations in troponin and LDH compared to accepted clinical baseline values. This finding may imply that patients with blood type O exhibit levels of biomarkers that indicate a diminished COVID-19 infection severity.

Prior immunological and microbiological research has found an association between blood type ABO and infection severity for SARS-CoV-1,

P. falciparum,

H. pylori, Norwalk virus, Hep B virus, and

N. gonorrhoeae [

27]. Our finding that blood type O- demonstrated a decreased risk of developing COVID-19 infection and an associated decreased mortality has been corroborated by other studies [

13,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. The negative Rh factor of blood type O- may be a protective factor against severe COVID-19 illness [

13,

27], potentially making O- the most optimal blood type regarding protection against COVID-19 infection and severity in the scope of this study.

Statistically significant differences were found in biomarkers of infection severity among blood types, which demonstrated that blood type O- had less elevated or more normal levels, such as those of LDH and troponin, which coincides with less severe infection. Elevated LDH and troponin levels have been correlated with severe COVID-19 infection [

36], as is the case with such levels in the setting of infection from other pathogens. Interestingly, we also found that blood type O exhibited decreased levels of MCH which may ultimately be due to decreased iron. A study by Hoque et al. comparing blood groups and serum iron levels noted that those with type O blood had the lowest hemoglobin and serum iron out of all the blood types while type A donors had the highest mean TIBC levels [

37]. RNA viruses require iron to replicate, thus, a depletion of iron may provide some viral mitigation [

38]. Blood type A exhibited elevated levels of IL-6 (> 35 pg/ml) in comparison to type B or O (p-value <0.001 via Chi-squared test). Other studies have also shown variations in acute phase reactants (IL-6, CRP, Procalcitonin, D-dimers) between the ABO blood types [

17].

Some studies found that blood type A had a higher risk of infection and mortality than type O. They attributed the seemingly protective nature of blood type O against COVID-19 to anti-A antibodies’ antagonization of SARS-CoV-2 and ACE-2 receptor binding [

39]. We question solely attributing this protective quality to one underlying mechanism, as our results demonstrated that specifically blood type O, but not B, is protective against COVID-19. Both blood type O and B have anti-A antibodies. Additionally, this hypothesis only accounts for S1B, not S1A, of the dual subunits of the COVID-19 monomer.

We posit an alternative theory that aligns with our study results and encompasses both potential binding sites of the virus. A higher amount of COVID-19 viral entry has been shown to coincide with a higher COVID-19 viral load with prolonged and more systemically dispersed viral shedding, which corresponds to greater COVID-19 infection severity [

40,

41]. Patients with mild cases of COVID-19 have demonstrated lower viral loads with a shorter duration of shedding that was more localized to their respiratory tract as compared to patients with severe cases [

40]. Therefore, more viral entry may be associated with more severe COVID-19 infection. Given this observed trend, the protective nature of blood type O against COVID-19 severity may be attributed to the diminished (5-N-acetyl-9-O-acetyl-) sialoside cluster formation through cis carbohydrate-carbohydrate stimulation, which may minimize the interaction of host cells with SARS-CoV-2 [

42]. This mechanism can decrease the potential likelihood of binding of the N-terminal region of the polypeptide chain and receptor binding domains of the COVID-19 virus to CD147 and ACE2 receptors [

42]. In short, blood type O may be protective against severe COVID-19 infection due to decreased sialoside expression, minimizing binding of COVID-19 virus to entry points on human cells. Further investigation into the underlying mechanism of the protective nature of blood type O against severe COVID-19 infection is warranted.

The lack of association between blood type and COVID-19 infection in our longitudinal cohort may be accounted for by mild cases that did not necessitate inpatient care. The discrepancy between statistically significant differences in findings in the inpatient, but not in the longitudinal, setting speaks to blood type ABO playing more of a role in overall severity of infection rather than in infectivity itself. We encourage further research into generalizable, global associations between blood type ABO and COVID-19 infection and severity.

Lastly, it is important to note that during the majority of the inpatient retrospective chart review investigation, COVID-19 vaccines were not yet developed. Our chart review spanned from January 1, 2020, to March 31, 2021. On December 11, 2020, the United States Food and Drug Administration issued the first emergency use authorization for the use of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine in persons aged 16 years and older [

43]. Regarding our longitudinal cohort, most patients received the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine (57.8%), then Modern (33%), and lastly, Johnson & Johnson (4.3%). Vaccines by Pfizer and Moderna have been touted to be the most effective in preventing severe infection via formation of antibodies and immunity [

44]. Both vaccines can cause adverse effects, but these reactions are reported to be less frequent in patients administered Pfizer than Moderna [

44]. However, a cited benefit of the Moderna vaccine is that it can be easily transported and stored because it is less temperature sensitive than the Pfizer vaccine [

44]. Several cases of thromboses and Guillain-Barré syndrome due to the Johnson & Johnson were announced over the course of public administration, which spread hesitancy and reluctance in getting this manufacturer’s vaccine [

45]. These trends were reflected by the vaccination status and distribution of our longitudinal cohort. Regardless of vaccination status, association of ABO blood type and COVID-19 infection was not statistically significant in this analyzed population.

4.1. Limitations

Our study is limited in external validity and therefore lacks generalizability to a larger population. This lack of generalizability is due to selection bias inherent within our inclusion criteria. Our inpatient cohort only includes patients that presented to the emergency department, while the longitudinal cohort consisted solely of those presenting to the clinic that were willing to participate in a survey. Additionally, the selection process excluded the many COVID-19 positive patients that were asymptomatic nor those that did not seek any professional medical care. There are many infected with COVID-19 who were asymptomatic or had mild illnesses that, if included in this study, might alter the results of the statistical analyses. Thus, our results must be properly applied to the inpatient and outpatient setting only. The power of our study is limited due to our small sample sizes of 669 inpatient and 185 longitudinal participants.

5. Conclusion

Blood type appears to be associated with COVID-19 infection severity and mortality in inpatient populations. In an inpatient setting, blood type O sustained less risk of COVID-19 mortality and blood type O- demonstrated less risk of developing COVID-19 pneumonia. In a longitudinal setting, there was no association found between blood type and COVID-19 severity. As the novelty of COVID-19 infection declines with time, further studies on risk-stratification by blood type are encouraged.

Author Contributions

All authors meet the four criteria for ICMJE authorship, which include (1) substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work, or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data for the work, (2) drafting the work or revising it critically for important intellectual content, (3) final approval of the version to be published, and (4) agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. Conceptualization, Tiffany Eatz; Data curation, Tiffany Eatz, Charles Cash, Nathalie Perez, Zachary Cromar, Adiel Hernandez, Matthew Cordova, Neha Godbole, Le Anh, Rachel Lin, Sherry Luo, Anmol Patel, Yaa Abu and Savita Pahwa; Formal analysis, Tiffany Eatz, Alejandro Mantero and Erin Williams; Funding acquisition, Suresh Pallikkuth and Savita Pahwa; Investigation, Tiffany Eatz, Erin Williams, Charles Cash, Nathalie Perez, Zachary Cromar, Adiel Hernandez, Matthew Cordova, Neha Godbole, Le Anh, Rachel Lin, Anmol Patel, Yaa Abu, Suresh Pallikkuth and Savita Pahwa; Methodology, Tiffany Eatz, Alejandro Mantero, Erin Williams, Suresh Pallikkuth and Savita Pahwa; Project administration, Tiffany Eatz and Savita Pahwa; Resources, Tiffany Eatz, Sherry Luo, Suresh Pallikkuth and Savita Pahwa; Software, Alejandro Mantero and Erin Williams; Supervision, Tiffany Eatz and Savita Pahwa; Validation, Alejandro Mantero, Erin Williams and Savita Pahwa; Visualization, Tiffany Eatz; Writing – original draft, Tiffany Eatz; Writing – review & editing, Tiffany Eatz, Alejandro Mantero, Erin Williams, Charles Cash, Nathalie Perez, Zachary Cromar, Adiel Hernandez, Matthew Cordova, Neha Godbole, Le Anh, Rachel Lin, Sherry Luo, Anmol Patel, Yaa Abu, Suresh Pallikkuth and Savita Pahwa.

Funding

The retrospective chart review received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The longitudinal prospective portion of this study is part of the PARIS /SPARTA studies funded by the NIAID Collaborative Influenza Vaccine Innovation Centers (CIVIC) contract 75N93019C00051 (PI F Krammer) with SGP as PI of the University of Miami site. Also supported by Miami Center for AIDS Research (CFAR) laboratory sciences core at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine funded by a grant (P30AI073961) to SP from the NIH, which is supported by the following NIH Co-Funding and Participating Institutes and Centers: NIAID, NCI, NICHD, NHLBI, NIDA, NIMH, NIA, NIDDK, NIGMS, FIC, and OAR.

Institutional Review Board Statement

IRB approved (IRB: #20210025 and 20201026).

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent obtained for the CITY longitudinal cohort study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The following authors have no financial disclosures or personal conflicts of interest: TAE, AMMM, ECW, CJC, NP, ZC, AH, MC, NG, AL, RL, SL, AP, AY, SP, SP.

Abbreviations

SARS-CoV-2—severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2; ED—emergency department; ARDS—diagnosis of acute respiratory distress syndrome; Rh—rhesus.

References

- Huang, J.Y.; Wang, R.; Gao, Y.T.; Yuan, J.M. ABO blood type and the risk of cancer—Findings from the Shanghai Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0184295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dentali, F.; Sironi, A.P.; Ageno, W.; Turato, S.; Bonfanti, C.; Frattini, F.; Crestani, S.; Franchini, M. Non-O blood type is the commonest genetic risk factor for VTE: Results from a meta-analysis of the literature. Semin Thromb Hemost 2012, 38, 535–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkebsi, L.; Ideno, Y.; Lee, J.S.; Suzuki, S.; Nakajima-Shimada, J.; Ohnishi, H.; Sato, Y.; Hayashi, K. Gastroduodenal Ulcers and ABO Blood Group: The Japan Nurses’ Health Study (JNHS). J Epidemiol 2018, 28, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooling, L. Blood Groups in Infection and Host Susceptibility. Clin Microbiol Rev 2015, 28, 801–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, D.S.; Chen, D.L.; Ren, C.; Wang, Z.Q.; Qiu, M.Z.; Luo, H.Y.; Zhang, D.S.; Wang, F.H.; Li, Y.H.; Xu, R.H. ABO blood group, hepatitis B viral infection and risk of pancreatic cancer. Int J Cancer 2012, 131, 461–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garratty, G. Blood groups and disease: A historical perspective. Transfus Med Rev 2000, 14, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindesmith, L.; Moe, C.; Marionneau, S.; Ruvoen, N.; Jiang, X.; Lindblad, L.; Stewart, P.; LePendu, J.; Baric, R. Human susceptibility and resistance to Norwalk virus infection. Nat Med 2003, 9, 548–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, J.A.; Handel, I.G.; Thera, M.A.; Deans, A.M.; Lyke, K.E.; Koné, A.; Diallo, D.A.; Raza, A.; Kai, O.; Marsh, K.; et al. Blood group O protects against severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria through the mechanism of reduced rosetting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2007, 104, 17471–17476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abegaz, S.B. Human ABO Blood Groups and Their Associations with Different Diseases. Biomed Res Int 2021, 2021, 6629060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scialo, F.; Daniele, A.; Amato, F.; Pastore, L.; Matera, M.G.; Cazzola, M.; Castaldo, G.; Bianco, A. ACE2: The Major Cell Entry Receptor for SARS-CoV-2. Lung 2020, 198, 867–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Garner, R.; Salehi, S.; La Rocca, M.; Duncan, D. Association between ABO blood types and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), genetic associations, and underlying molecular mechanisms: A literature review of 23 studies. Ann Hematol 2021, 100, 1123–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zhang, J.; Jia, L.; Ai, J.; Yu, Y.; Wang, M.; Li, P. ABO blood group influence COVID-19 infection: A meta-analysis. J Infect Dev Ctries 2021, 15, 1801–1807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ray, J.G.; Schull, M.J.; Vermeulen, M.J.; Park, A.L. Association Between ABO and Rh Blood Groups and SARS-CoV-2 Infection or Severe COVID-19 Illness: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Ann Intern Med 2021, 174, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anderson, J.L.; May, H.T.; Knight, S.; Bair, T.L.; Horne, B.D.; Knowlton, K.U. Association of Rhesus factor blood type with risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 severity. Br J Haematol 2022, 197, 573–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miotto, M.; Di Rienzo, L.; Gosti, G.; Milanetti, E.; Ruocco, G. Does blood type affect the COVID-19 infection pattern? PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0251535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.; Latz, C.A.; DeCarlo, C.S.; Lee, S.; Png, C.Y.M.; Kibrik, P.; Sung, E.; Alabi, O.; Dua, A. Relationship between blood type and outcomes following COVID-19 infection. Semin Vasc Surg 2021, 34, 125–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, U.; Malik, A.; Malik, J.; Mehmood, A.; Qureshi, A.; Laique, T.; Zaidi, S.M.J.; Javaid, M.; Rana, A.S. Association of ABO blood group with COVID-19 severity, acute phase reactants and mortality. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0261432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabrah, S.M.; Abuzerr, S.S.; Baghdadi, M.A.; Kabrah, A.M.; Flemban, A.F.; Bahwerth, F.S.; Assaggaf, H.M.; Alanazi, E.A.; Alhifany, A.A.; Al-Shareef, S.A.; et al. Susceptibility of ABO blood group to COVID-19 infections: Clinico-hematological, radiological, and complications analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021, 100, e28334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, P.; McAuley, D.F.; Brown, M.; Sanchez, E.; Tattersall, R.S.; Manson, J.J.; on behalf of theHLH Across Speciality Collaboration, UK. COVID-19: Consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet 2020, 395, 1033–1034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tay, M.Z.; Poh, C.M.; Rénia, L.; MacAry, P.A.; Ng, L.F.P. The trinity of COVID-19: Immunity, inflammation and intervention. Nat Rev Immunol 2020, 20, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Shi, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, J.; Huang, L.; Zhang, C.; Liu, S.; Zhao, P.; Liu, H.; Zhu, L.; et al. Pathological findings of COVID-19 associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet Respir Med 2020, 8, 420–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Li, T.; Han, M.; Li, X.; Wu, D.; Xu, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Wang, L. Diagnostic utility of clinical laboratory data determinations for patients with the severe COVID-19. J Med Virol 2020, 92, 791–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, C.; Zhou, L.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.; Tao, Y.; Xie, C.; Ma, K.; Shang, K.; Wang, W.; Tian, D.S. Dysregulation of Immune Response in Patients With Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China. Clin Infect Dis 2020, 71, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, F.; Huang, Y.; Guo, Y.; Yin, M.; Chen, X.; Xiao, L.; Deng, G. Association of inflammatory markers with the severity of COVID-19: A meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis 2020, 96, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clinic, C. Blood Types 2023.

- Simon, V.; Kota, V.; Bloomquist, R.F.; Hanley, H.B.; Forgacs, D.; Pahwa, S.; Pallikkuth, S.; Miller, L.G.; Schaenman, J.; Yeaman, M.R.; et al. PARIS and SPARTA: Finding the Achilles’ Heel of SARS-CoV-2. mSphere 2022, 7, e0017922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zietz, M.; Zucker, J.; Tatonetti, N.P. Associations between blood type and COVID-19 infection, intubation, and death. Nat Commun 2020, 11, 5761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göker, H.; Aladağ Karakulak, E.; Demiroğlu, H.; Ayaz Ceylan, Ç.M.; Büyükaşik, Y.; Inkaya, A.Ç.; Aksu, S.; Sayinalp, N.; Haznedaroğlu, I.C.; Uzun, Ö.; et al. The effects of blood group types on the risk of COVID-19 infection and its clinical outcome. Turk J Med Sci 2020, 50, 679–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Cheng, G.; Chui, C.H.; Lau, F.Y.; Chan, P.K.; Ng, M.H.; Sung, J.J.; Wong, R.S. ABO blood group and susceptibility to severe acute respiratory syndrome. Jama 2005, 293, 1450–1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Feng, Z.; Li, P.; Yu, Q. Relationship between ABO blood group distribution and clinical characteristics in patients with COVID-19. Clin Chim Acta 2020, 509, 220–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Yang, Y.; Huang, H.; Li, D.; Gu, D.; Lu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, L.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; et al. Relationship Between the ABO Blood Group and the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Susceptibility. Clin Infect Dis 2021, 73, 328–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Cai, Y.; Deng, A.; Yang, M. Association between ABO blood groups and risk of SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. Br J Haematol 2020, 190, 24–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solmaz, İ.; Araç, S. ABO blood groups in COVID-19 patients; Cross-sectional study. Int J Clin Pract 2021, 75, e13927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muñiz-Diaz, E.; et al. Relationship between the ABO blood group and COVID-19 susceptibility, severity and mortality in two cohorts of patients. Blood Transfus 2021, 19, 54–63. [Google Scholar]

- Ellinghaus, D.; Llopis, J.; Parra, R.; Roig, I.; Ferrer, G.; Grifols, J.; Millán, A.; Ene, G.; Ramiro, L.; Maglio, L.; et al. Genomewide Association Study of Severe Covid-19 with Respiratory Failure. N Engl J Med 2020, 383, 1522–1534. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, F.; Yu, T.; Du, R.; Fan, G.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Z.; Xiang, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, B.; Gu, X.; et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: A retrospective cohort study. Lancet 2020, 395, 1054–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, M.M.; Adnan, S.D.; Karim, S.; Al-Mamun, M.A.; Faruki, M.A.; Islam, K.; Nandy, S. Relationship between Serum Iron Profile and Blood Groups among the Voluntary Blood Donors of Bangladesh. Mymensingh Med J 2016, 25, 340–348. [Google Scholar]

- Menshawey, R.; Menshawey, E.; Alserr, A.H.K.; Abdelmassih, A.F. Low iron mitigates viral survival: Insights from evolution, genetics, and pandemics—A review of current hypothesis. 2020, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillon, P.; Clément, M.; Sébille, V.; Rivain, J.G.; Chou, C.F.; Ruvoën-Clouet, N.; Le Pendu, J. Inhibition of the interaction between the SARS-CoV spike protein and its cellular receptor by anti-histo-blood group antibodies. Glycobiology 2008, 18, 1085–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Sang, L.; Ye, F.; Ruan, S.; Zhong, B.; Song, T.; Alshukairi, A.N.; Chen, R.; Zhang, Z.; et al. Kinetics of viral load and antibody response in relation to COVID-19 severity. J Clin Invest 2020, 130, 5235–5244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Lan, Y.; Yuan, X.; Deng, X.; Li, Y.; Cai, X.; Li, L.; He, R.; Tan, Y.; Deng, X.; et al. Detectable 2019-nCoV viral RNA in blood is a strong indicator for the further clinical severity. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020, 9, 469–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva-Filho, J.C.; Melo, C.G.F.; Oliveira, J.L. The influence of ABO blood groups on COVID-19 susceptibility and severity: A molecular hypothesis based on carbohydrate-carbohydrate interactions. Med Hypotheses 2020, 144, 110155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parums, D.V. Editorial: First Full Regulatory Approval of a COVID-19 Vaccine, the BNT162b2 Pfizer-BioNTech Vaccine, and the Real-World Implications for Public Health Policy. Med Sci Monit 2021, 27, e934625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meo, S.A.; Bukhari, I.A.; Akram, J.; Meo, A.S.; Klonoff, D.C. COVID-19 vaccines: Comparison of biological, pharmacological characteristics and adverse effects of Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna Vaccines. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2021, 25, 1663–1669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenblum, H.G.; Hadler, S.C.; Moulia, D.; Shimabukuro, T.T.; Su, J.R.; Tepper, N.K.; Ess, K.C.; Woo, E.J.; Mba-Jonas, A.; Alimchandani, M.; Nair, N. Use of COVID-19 Vaccines After Reports of Adverse Events Among Adult Recipients of Janssen (Johnson & Johnson) and mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines (Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna): Update from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices—United States, July 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2021, 70, 1094–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).