1. Introduction

There is a body of evidence suggesting intersection of viruses and autoimmunity. Several previous works postulated a high potential of viruses such as cytomegalovirus virus, Epstein-Barr virus, hepatitis B and C or SARS-CoV-2 to trigger autoimmune processes in genetically predisposed subjects [

1,

2,

3]. An inappropriate immune response is the cardinal feature of COVID-19 infection leading to severe course of the virus infection and on the other hand promoting development of a number of autoimmune diseases [

3]. In a subset of COVID-19 patients suffering from severe COVID-19 pneumonia a robust production of type I interferon tracked organ damages [

3]. The appearance of functional autoantibodies following COVID-19 infection was discussed to contribute to the virus-mediated autoimmunity [

3]. Chronic hepatitis C progresses to in liver cirrhosis, end-stage liver failure or hepatocellular carcinoma via persisting activity of cytotoxic CD8

+ T cells which initiate chronic inflammatory processes in the liver and are also capable to induce autoimmune phenomena. However the mechanism how viral infection can tip the host immune response towards the loss of tolerance are not fully understood and require further clarification.

Type I interferon response displays an essential role in antiviral defense restricting replication of the virus in the infected cells [

4]. Conversely, sustained type I interferon release switches on anti-inflammatory pathways, including the production of interleukin-10 (IL-10) and the expression of programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) [

5]. Thus, IL-10 and PD-L1 exert inhibitory functions on virus-specific CD8

+ T cells accounting for subsequent exhaustion of CD8

+ T cells [

5]. Vice versa, during viral infection PD-L1 expression arises in infected cells enabling the virus to avoid the deterioration through cytotoxic T lymphocytes [

6]. Consequently, upregulation of PD-L1 on target cells with concomitant exhaustion of CD8

+ T cells might to be supposed to preserve such patients from serious virus-triggered immunopathology who are at risk.

Ubiquitination is an important mechanism of posttranslational modification of proteins playing an essential role in regulation of protein activity and cell homeostasis [

7]. Deubiquitinases as cysteine proteases remove ubiquitin chains from several substrates leading to protein activation, inactivation, DNA repair, gene regulation, signal transduction and degradation of proteins [

7,

8,

9]. In the last decade, more than 100 deubiquitinase enzymes were identified in humans. They were divided in six different families, while the ubiquitin-specific-peptidases (USPs) represent the largest subfamily accounting for more than 50% of all deubiquitinases [

9,

10]. Members of the USP group are highly conserved and are composed of three subdomains resembling the right finger, thumb and palm [

9,

11].

Ubiquitin-Specific-peptidase 22 (Usp22) belongs to the USP family and builds up as a key component the Spt-Ada-Gen5 Acetyl transferase complex (SAGA) [

6,

7,

8]. The SAGA complex removes ubiquitin from the target transcription factors allowing transcription of downstream genes [

12]. Usp22 is able to deubiquitinate histones as well as non-histone substrates [

7,

9]. Thus, Usp22 is involved in controlling a variety of cellular functions. The enzymatically active Usp22 catalyzes the deubiquitination of the histones H2A and H2B resulting in changes in gene promotor regions and initiating transcription of diverse genes [

12,

13,

14,

15]. Besides histones, Usp22 interacts with a number of non-histone substrates like for example TRF1, SIRT1, NFAT or Cyclin B1 facilitating protein stabilization and suppressing protein degradation through proteasomes [

7,

9]. With regard to the ubiquitous expression of Usp22, its functions include regulation of cell cycle, metabolism, cell development and apoptosis processes [

7,

16,

17,

18,

19]. In general, activation of Usp22 tends to promote cell survival pathways and to inhibit apoptosis [

7]. Due to these pro-mitotic characteristics which are directed to cell survival and cell cycle progression, Usp22 is considered as a potential oncogene [

20]. Consequently recent studies reported the overexpression of Usp22 relying on poor survival, occurrence of metastasis and recurrence of multiple cancer entities [

7,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24].

In the past years, the evidence on regulatory functions of Usp22 in innate immune system responses was growing [

25,

26,

27,

28]. Usp22 was linked to regulation of interferon response via deubiquitination of histone H2B which serves for activation of interferon signaling pathways [

25]. Therefore, the loss of Usp22 in hematopoietic system generated increased levels of locus-specific H2Bub1 followed by up-regulation of many interferon stimulated genes in hematopoietic cells. Interferon signaling and downstream pathways induced by interferon-stimulated genes are critically required for antiviral immunity. While Usp22 is able to affect the expression of a large set of interferon-stimulated genes, it might be concerned as a potential key player in antiviral defense [

26]. Previous

in vitro works support this presumption demonstrating negative regulator functions of Usp22 in type I and III interferon mediated pathways upon viral infection [

26,

27,

28]. In contrast, the deficiency of Usp22 caused augmented activation of pathways involved in type I and III interferon signaling [

25,

26].

Hence, our study was aimed to analyze the effects of conditional knockout of Usp22 restricted to the hematopoietic system on the course of lymphocytic choriomeningitis (LCMV) virus infection as a common model for acute viral murine infection. Thereby, control of LCMV infection is known to be strongly dependent on interferon response.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Mice

The Usp22 KO (Usp22

fl/fl Vav1-Cre mice) were generated by Dietlein et al. as previously described and had a pan-hematopoietic deletion of the Usp22 protein [

25]. The Usp22 were provided by Nikolaus Dietlein from the Division of Cellular Immunology, German Cancer Research Center, Heidelberg, Germany. The mice housed in individual ventilated cages under specific pathogen-free conditions. During survival experiments, the health status of the mice was checked twice daily. All animal experiments were authorized by the Landesamt für Natur, Umwelt und Verbraucherschutz (81-02.04.2019.A143 LANUV, Recklinghausen, Germany) Nordrhein-Westfalen and were performed in compliance with the German law for animal protection (TierSchG). Animals exhibiting severe symptoms of sickness or showing a substantial weight loss during infection were put to death and considered dead for statistical analysis.

The mice with lack of Cre recombinase or only one floxed site displayed wild type phenotype and were considered as control animals.

2.2. Virus and plaque assay

LCMV strain WE was originally obtained from F. Lehmann-Grube (Heinrich Pette Institute, Hamburg, Germany) and propagated in L929 cells as previously described [

29]. In all experiments the LCMV WE was injected intravenously at the dosage of 2x10E

5 PFU per mouse. Viral titers were quantified in a plaque-forming assay on MC57 fibroblasts as previously described [

30]. In brief, organs were harvested into DMEM medium containing 2% FCS and homogenized using a tissuelyzer (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Diluted virus sampled were added to the L929 cell culture on the 24-well plate. After 3 hours, the plate was covered with methylcellulose 1% medium. After 2 days incubation, viruses were stained against LCMV nucleoprotein via an anti-LCMV-NP antibody (clone VL-4, Bio X Cell, Lebanon, USA).

2.3. Cell depletion

Depletion of CD8+ T cells was performed with anti-CD8 antibody (anti-mouse CD8a antibody, clone YTS 169.4, Bio X Cell, Lebanon, USA). The anti-CD8-antibody was applied intraperitoneally at the dosage of 100 ug per mouse at day -1 before LCMV infection, at the day of infection and then every second day. Monocytes and neutrophil granulocytes were depleted using the anti-Gr-1 antibody (anti-mouse Ly6G/Ly6C antibody, clone RB6-8C5, Bio X Cell, Lebanon, USA) which was injected intraperitoneally at dosage of 500 ug per mouse at day -1 before LCMV infection, at the day of infection and then every second day.

2.4. ALAT, ASAT and LDH measurement

The activity of liver enzymes, ALAT, ASAT and LDH was measured in in the German Laboratory of the University Hospital Essen.

2.5. Histology

For immunofluorescence assay, snap-frozen tissue section were stained with mouse monoclonal antibodies to CD11b (clone M1/70), CD11c (clone N418), Ly6C (clone HK1.4), Ly6G (clone 1A8-Ly6G), CD8 (clone 53-6.7), F4/80 (clone BM8), IgM (clone 11/41), PD-L1 (clone MIH5) (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, USA) and CD169 (clone MCA884F, Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, USA). Histological analysis of snap-frozen liver sections for detection of LCMV particles was performed with mouse monoclonal antibody to LCMV nucleoprotein (NP, made in house). Images were acquired with the ZEISS Axio Observer Z1 (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany).

2.6. Flow cytometry

Experiments were performed using a FACS Fortessa (BD, Franklin Lakes, USA) and analyzed via FlowJo software (Ashland, USA). For surface molecule staining, single suspended cells were incubated with antibodies for 20 minutes at 4°C.

For the tetramer staining, 20 µl blood were incubated with allophycocyanin (APC)-labeled gp33 MHC class I tetramers (gp33/H-2Dd) for 15 minutes at 37°C (31). This LCMV-gp33 tetramer was provided by the Tetramer Facility of National Institute of Health (NIH). After incubation, the samples were stained with the anti-CD8 antibody (PECy7-conjugated, clone 53-67, Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA) for 30 minutes at 4°C. Erythrocytes were than lysed using 1 ml BD lysing solution (BD Biosciences), washed 1x and analyzed with flow cytometer. Absolut numbers of gp33-specific CD8+ T cells/ul blood were calculated from FACS analysis using fluorescing beads (BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, USA).

For measurement of intracellular interferon-γ production, single suspendered cells were stimulated with LCMV-specific peptides gp33 for 1 hour (31). Brefeldin A (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, USA) was added for another 16-hour incubation at 37°C followed by staining with anti-CD8 (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, USA). After surface staining, cells were fixed with 2% formaldehyde in PBS for 20 minutes, followed by permeabilization with 1% saponin in FACS buffer at room temperature and stained with anti-interferon-γ antibody for 30 minutes at room temperature (clone XMG1.2; eBioscences, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, USA).

2.7. Multiplex assay

Serum cytokines were analyzed with LEGENDplex™ (BioLegend, San Diego, USA) according to the instructions and recommendation of the manufacturer.

2.8. Statistical analysis

To detect statistically significant differences between two groups the Student´s t-test was used. For analysis of differences in survival rates the Log-rank test was carried out. All mentioned experiments were done at least twice with similar results. Date are expressed as mean ± S.E.M. The level of statistical significance was set at P<0.05. All data analyses were calculated with GraphPad Prism version 6 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA, USA).

4. Discussion

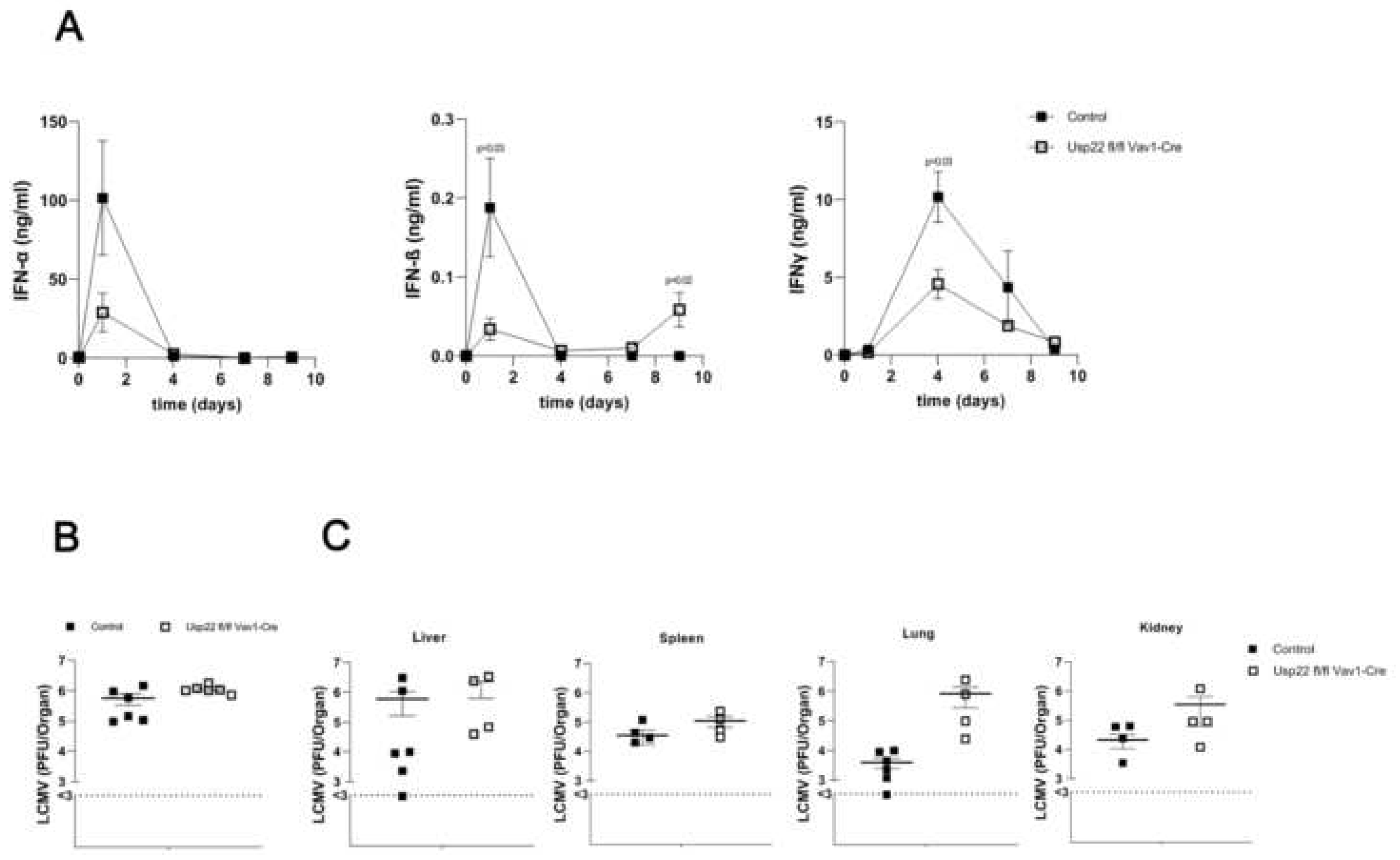

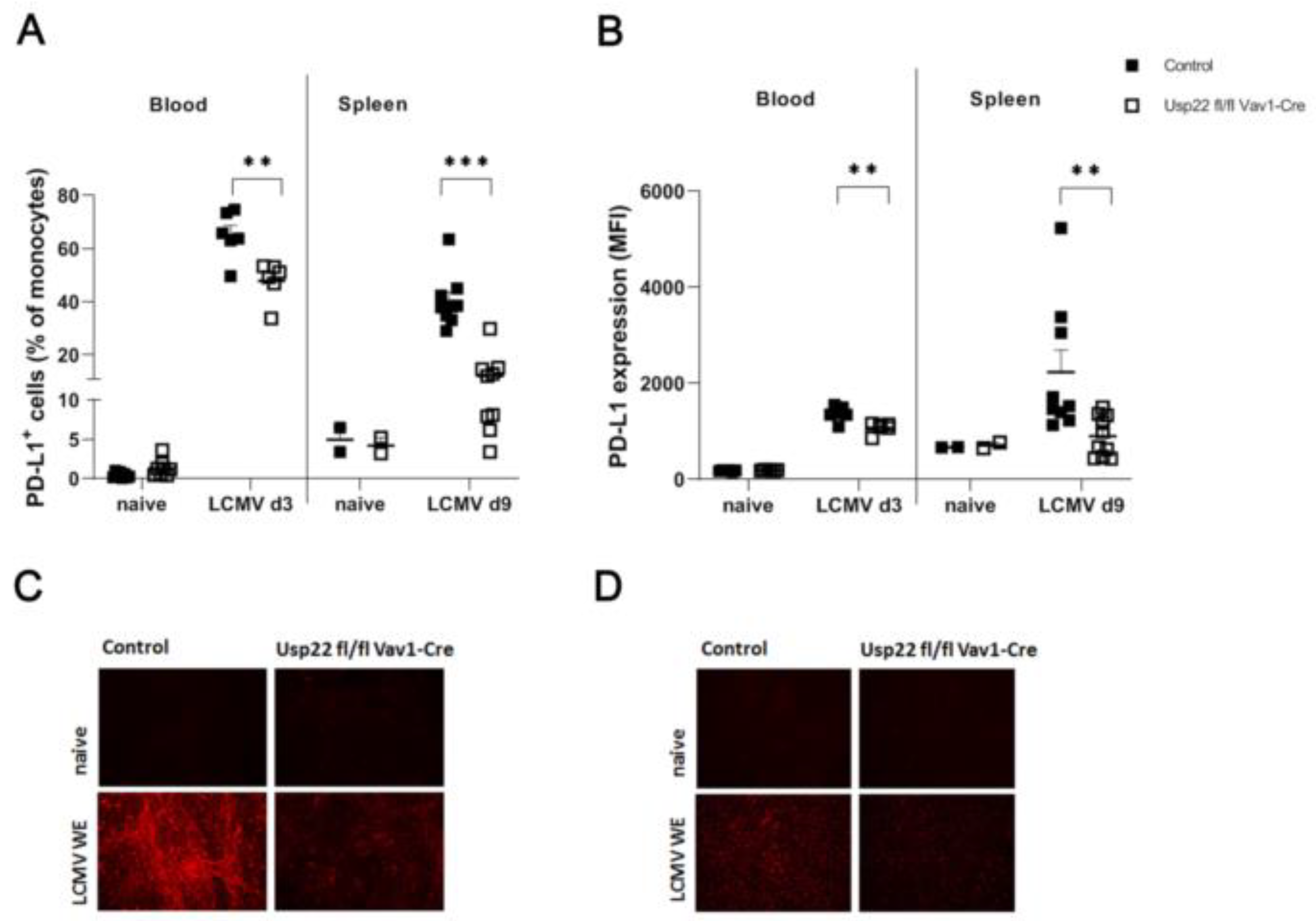

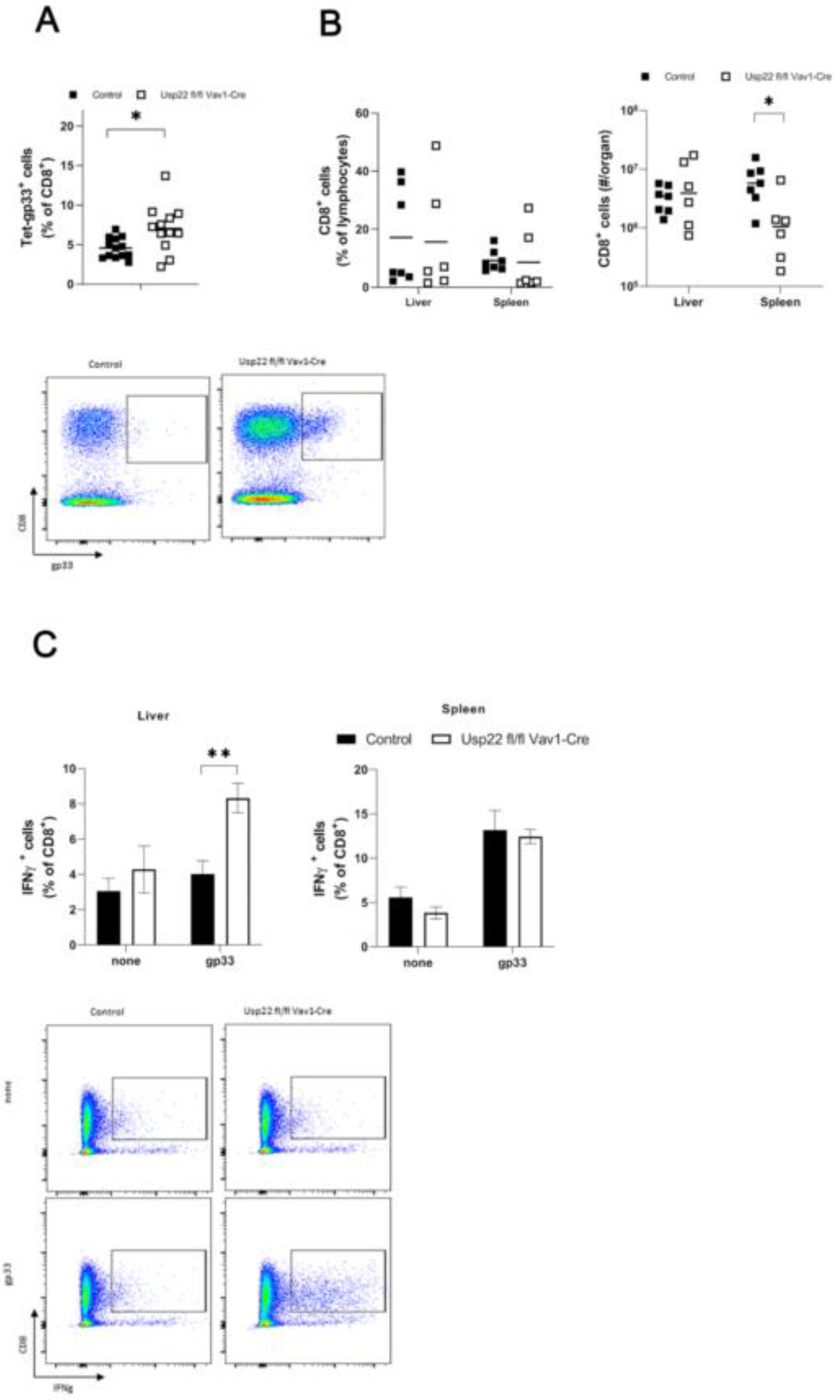

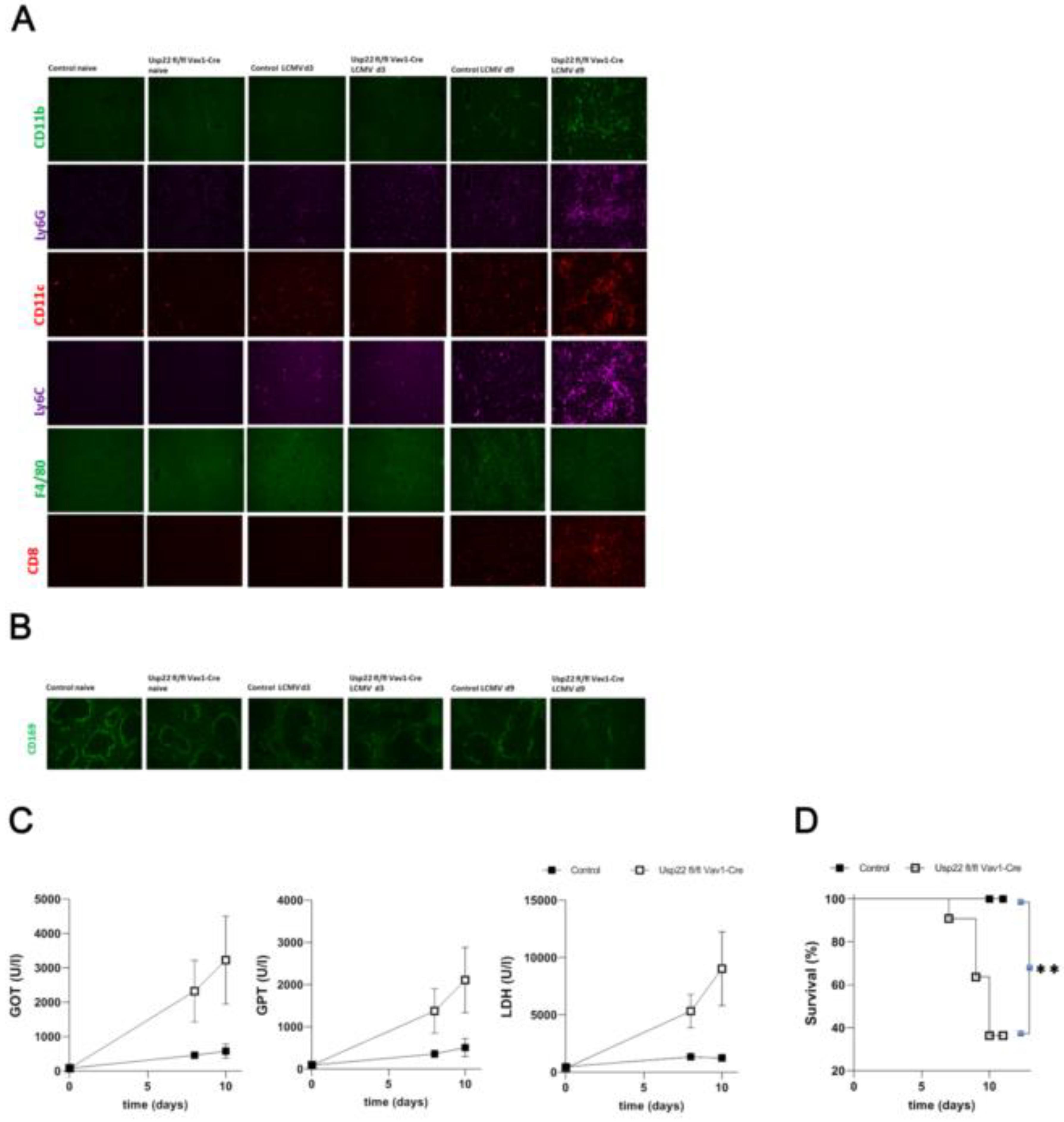

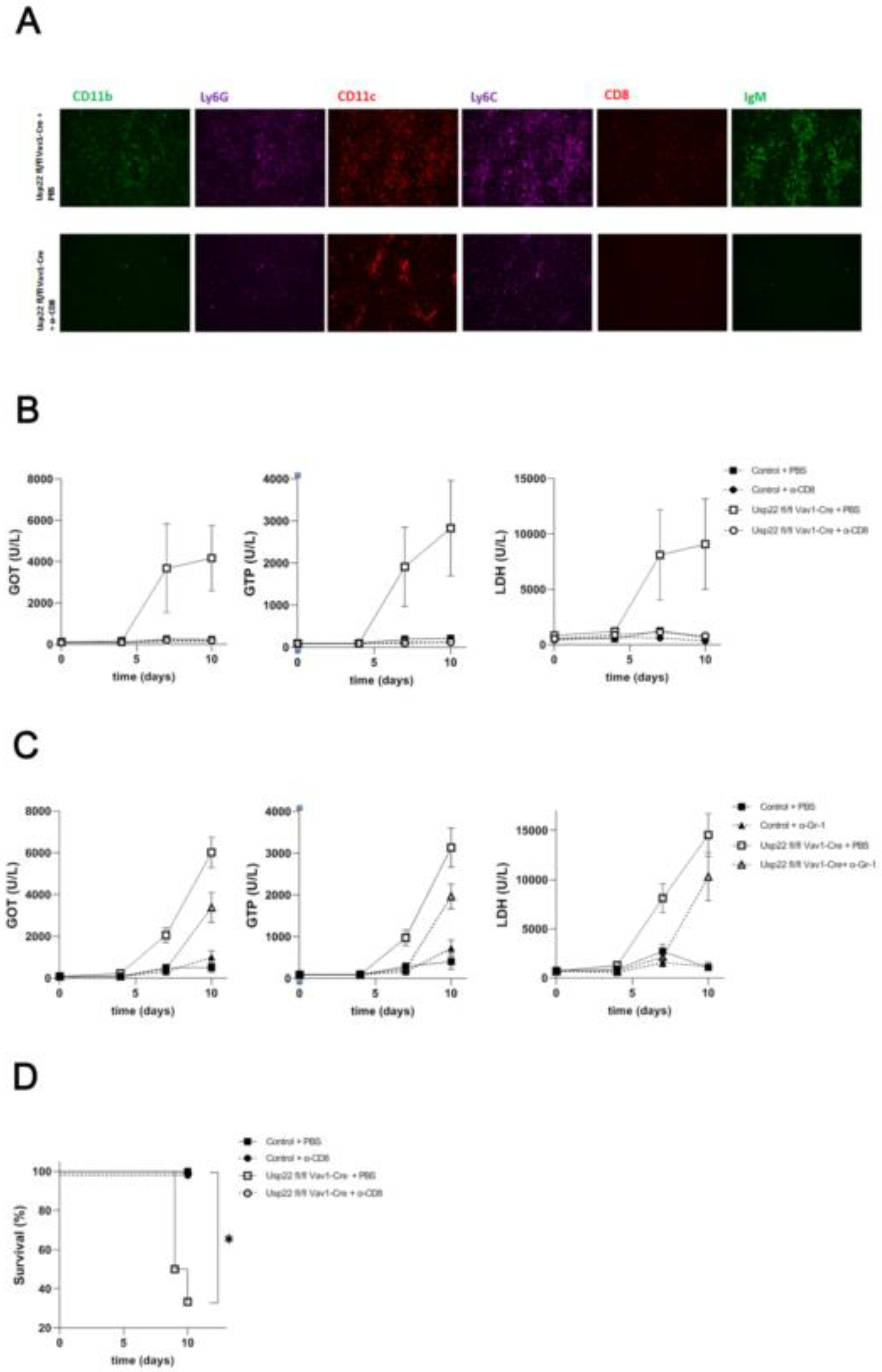

In the study reported here, we found that the absence of Usp22 in the hematopoietic system led to severe immunopathology in the liver following intravenous infection with LCMV. Usp22 deficient mice exhibited decreased levels of type I interferon at the first day after LCMV infection that did not relevantly limit virus clearance. The liver pathology was associated with liver failure occurring 7 days post-infection and was mediated by disturbed CD8+ T cell response leading to invasion of the liver by granulocytes and monocytes. The lack of Usp22 was associated with strong activation of LCMV-specific CD8+ T cells accompanied by augmented interferon gamma production. Additionally, PD-L1 expression on monocytes was reduced in Usp22 deficient mice which underwent LCMV infection. Ablation of CD8+ T cells restricted immunopathology in the liver due to LCMV-infection in Usp22 KO mice, whereas depletion of granulocytes and monocytes only prolonged the time until the appearance of acute liver failure. Collectively, these findings suggest that enhanced immunity of virus-specific CD8+ T cells accompanied by reduction of PD-L1 expression on antigen presenting cells might have promoted the liver immunopathology after acute viral infection with LCMV in Usp22 deficient animals.

Intriguingly, the research group of Dietlein et al. identified that the deficiency of Usp22 was related to appearance of emergency hematopoiesis. Despite of absence of infection or inflammatory signals, mice lacking Usp22 in their hematopoietic system displayed overproduction of myeloid cells, in particular granulocytes, alteration in development of B-cells and enhancement in expression of proinflammatory genes [

25]. Loss of Usp22 exerted a protective effect in case of in vivo infection with Listeria monocytogenes [

25]. Elevated proliferation of progenitors of myeloid cells accompanied by heightened phagocytosis capacity of neutrophil granulocytes was observed in infected mice having deficiency of Usp22 [

25].

First, we hypothesized that alterations in interferon release related to the absence of Usp22 might be critical for virus control and elimination. Lui et al. demonstrated modulating function of Usp22 on type I interferon production and interferon mediated pathways [

26]. Increased Usp22 expression

in vitro after corresponding transfection of 293T cells resulted in inhibited type I interferon formation upon infection with murine Sendai virus [

26]. The infection of Vero cells overexpressing Usp22 with vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) also led to reduced production of proinflammatory cytokines inclusive interferons making the Vero cells more susceptible to VSV [

26]. On the other hand, the replication of VSV, Sendai virus and herpes simplex virus (HSV) was restrained after knock down of Usp22 in A549 cells [

26]. Mechanistically, viral infection strengthens cooperation of Usp22 with another deubiquitinase Usp13 that promotes cleavage of the stimulator of interferon genes protein (STRING) [

26]. Moreover, Usp22 influences negatively secretion of interferon gamma [

27]. On contrary, the loss of Usp22 in human intestinal epithelial cells induced upregulation of diverse interferon-stimulated genes and interferon gamma production in a STRING signaling dependent manner and provided resistance against SARS-CoV-2 infection [

27]. Therefore, we awaited that Usp22 deficiency in our mouse model of acute viral infection might improve the viral clearance in relation to the enforced interferon production. However, we did not observe any relevant difference in virus control comparing Usp22 KO animals with controls. Our

in vivo experiment data showed effects which were opposite to the

in vitro data reported by Liu et al. [

26]. We detected diminishment of type I interferon levels at the first day after LCMV infection and LCMV virus titers in the spleen were slightly elevated in Usp22 deficient mice that is probably partly attributed to the decreased interferon production. In contrast to the previously reported

in vitro data on enhancement of interferon gamma secretion due to the absence of Usp22 upon SARS-CoV-2-infection, we detected a decrease of interferon gamma in Usp22 KO mice at day 4 after LCMV injection. Notably, data supporting the suppressive function of Usp22 on type I and II interferon production derived only from

in vitro experiments with infected murine or human cell lines. It is conceivable, that

in vivo numerous interactions of immune cells and cytokines might have provoked decrease of interferon concentrations after LCMV infection under the conditions of Usp22 loss that could explain the differences in comparison to the previously published

in vitro data. Dietlein et al. conducted experiments with mice having conditional knock out of Usp22 in hematopoietic system that were also used in our work [

25]. Despite infection- or inflammation-free conditions Usp22 KO mice displayed increased expression of inflammation genes, in particular interferon-stimulated genes, while systemic levels of interferon alpha and gamma remained similar between Usp22 KO mice and wild types. However, our data on interferon are more in agreement with observations of Cai et al. [

28]. Besides of nuclear expression of Usp22, the colleagues identified a cytoplasmic synthesis of this molecule. Animals with knockout or knockdown of Usp22 experienced a lethal course of infection with VSV or HSV-1 compared with respective controls [

28]. Serum concentrations of interferon beta were significantly decreased in Usp22 deficient mice at 12 to 24 hours post VSV or HSV-1 infection [

28]. Thus, significantly increased virus titers of VSV and HSV-1 were detected at day 4 after infection [

28]. To recover the corresponding pathomechanism for these findings, the authors proposed that cytoplasmic Usp22 removes ubiquitin conjugates from KPNA2 that serves for stabilization of KPNA2 which facilitates virus-triggered transmission of IRF3 into the nucleus and initiation of transcription of IRF3- dependent genes with antiviral properties [

28]. Loss of cytoplasmic Usp22 and consequently reduced induction of IRF3 regulated downstream pathways upon LCMV infection might provide a possible explanation for the low interferon production found in Usp22 deficient mice in our study.

Nevertheless, in our study no relevant changes in virus titers were detected at the late stage of infection when differentiating between KO and wild type animals. Hence, we questioned whether the liver failure after acute LCMV infection with subsequent lethal outcome in mice lacking Usp22 might be caused by overwhelming immune response towards LCMV as pathogen. In line with this hypothesis, we found strong infiltration of the liver tissue of infected Usp22 deficient mice by neutrophil granulocytes and monocytes. Dietlein et al. already described that the loss of Usp22 was associated with great potential towards immune enchantment [

25]. The phenotype of the mice with hematopoietic Usp22 knockout which also were used in the present study, was coined by emergency hematopoiesis with such hallmarks as raise of myelopoesis in bone marrow and enhanced phagocytosis specific for only neutrophil granulocytes [

25]. Increased phagocytosis capacity of neutrophil granulocytes was in particular apparent after bacterial infection of Usp22 deficient mice with Listeria monocytogenes which might be considered as an essential trigger [

25]. Consistent with the data published by Dietlein et al., infiltrates of neutrophil granulocytes identified in the liver of LCMV infected Usp22 KO animals might be a result of elevated myelopoesis. In addition, based on the above mentioned findings of Dietlein et al., severe deterioration in the liver upon LCMV infection might be explained by overactivated phagocytosis of neutrophil granulocytes inside the infiltrates. In light of our results, we also suggest that a viral infection with LCMV seems to be another potential trigger of granulocyte activation in absence of Usp22.

Indeed, depletion of granulocytes and monocytes was not efficient to restore the proceeding liver damage after LCMV infection in Usp22 KO mice. Thus, we took in account other possible aspects which might led to immunopathology. In fact, we saw an activation of virus-specific CD8

+ T cells in Usp22 deficient mice after administration of LCMV which probably was promoted by downregulation of PD-L1 expression on antigen presenting cells. Recently, a large number of reports suggested Usp22 as a regulator of PD-L1 expression [

20,

32]. Usp22 stabilizes PD-L1 protein protecting it against proteasome-mediated degradation in two ways, first via direct deubiquitination and secondly through interaction with the CSN5-PD-L1 axis modulating the CSN5 [

20]. As a consequence, ablation of the Usp22 was shown to inhibit the PD-L1 release giving raise to the T-cell regulated cell killing [

20,

32]. In particular, in samples derived from solid cancers aberrant expression of Usp22 was documented providing T cell exhaustion and allowing the evasion from immune system leading to cancer progression [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Further studies regarded Usp22 as positive regulator of the transcription factor forkhead box protein 3 (FOXP3) of the regulatory CD4+ T-cells [

20,

33,

34]. Deletion of the Usp22 in regulatory T cells reduced their suppressive effects on cytotoxic CD8

+ T cells [

34]. That means, that the lack of Usp22 might be responsible for disturbed function regulatory T cells supporting the trends towards autoimmunity in Usp22 deficient mice. In this way it is plausible, that immunopathology in the liver of LCMV infected Usp22 deficient mice might correspond to the upregulation of CD8

+ T cell mediated immunity due to the loss of suppressive signaling directed by PD-L1. In the current study, the essential role of virus specific CD8

+ T cell activation in the development of liver failure emphasizes the results from the CD8

+ T cell depletion experiments. There, the occurrence of liver failure after LCMV infection in Usp22 KO mice was successfully prevented by the treatment with a monoclonal anti-CD8

+ T cell antibody. In light of our data, the appearance of infiltrates predominantly consisting of neutrophil granulocytes and monocytes is most likely a secondary phenomenon following enhanced CD8

+ T cell response against LCMV. We also suppose the pronounced deposition of IgM colocalized with infiltrates of granulocytes and monocytes as a consequence of activation of granulocytes and monocytes involving stimulation of complement cascades.

In general, we reason, that the pathomechanism lying beyond the immunopathology detected upon LCMV infection of Usp22 deficient mice is multifactorial. Overall, our data support the conclusion that the downregulation of PD-L1 and enhanced functional CD8

+ T cell response to LCMV might be one of the critical events for the development of liver damage after LCMV infection in absence of Usp22. Further studies are required to fully address this point. In particular,

in vivo experiments under conditions of specific Usp22 knock out in T cells might be helpful to better clarify the role of CD8

+ T cell immunity in the context of LCMV infection. It is debatable, whether the slight but significantly decrease of interferon production at the early stage of acute LCMV infection leading to increased virus replication in the spleen might have contributed to the overactivated state of innate immune system, especially of CD8

+ T cells. The so far known, broadly preactivated interferon response by lack of Usp22 already in absence of infection underlines the importance of Usp22 deficiency in activation of innate immune system [

25]. The observations from our

in vivo experiments in Usp22 KO mouse model upon LCMV infection support the idea of the Usp22 absence as a stimulator of proinflammatory signaling and innate immune response, probably serving as a trigger of autoimmunity. Then, Usp22 seems to have negative regulatory effects in immunological processes which might be beneficial for coordination of overwhelming inflammation upon infections and controlling of autoimmune processes. Artificial induction of Usp22 or restoration of the deficient Usp22 production probably as a result of genetic variations such as single-nucleotide polymorphism might defend patients having for example COVID-19 or hepatitis C infection from unfavorable course of infection marked by severe immunopathology and prevent occurrence of autoimmune diseases.

Taken together, we showed occurrence of severe liver immunopathology upon LCMV infection in mice lacking Usp22 in their hematopoietic system which was mostly related to reduced expression of PD-L1 on antigen presenting cells and overactivation of virus specific CD8+ T cells resulting in recruitment of neutrophil granulocytes and monocytes infiltrating the liver and inducing acute liver failure.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, JFK, HRR, KSL; Methodology JFK, TCC, ND, EA, HA, LH, ZH; Formal Analysis, JFK, TCC, EA, HA.; Investigation, JFK, TCC, ND, EA, HA, LH, ZH; Writing – Original Draft Preparation, JFK, KSL; Writing – Review & Editing, JFK, TCC, ND, HRR, KSL; Visualization, JFK, TCC, EA, HA; Supervision, JFK, HRR, KSL; Project Administration, JFK, ND, KSL; Funding Acquisition, JFK, ND, HRR, KSL