Submitted:

10 August 2023

Posted:

11 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

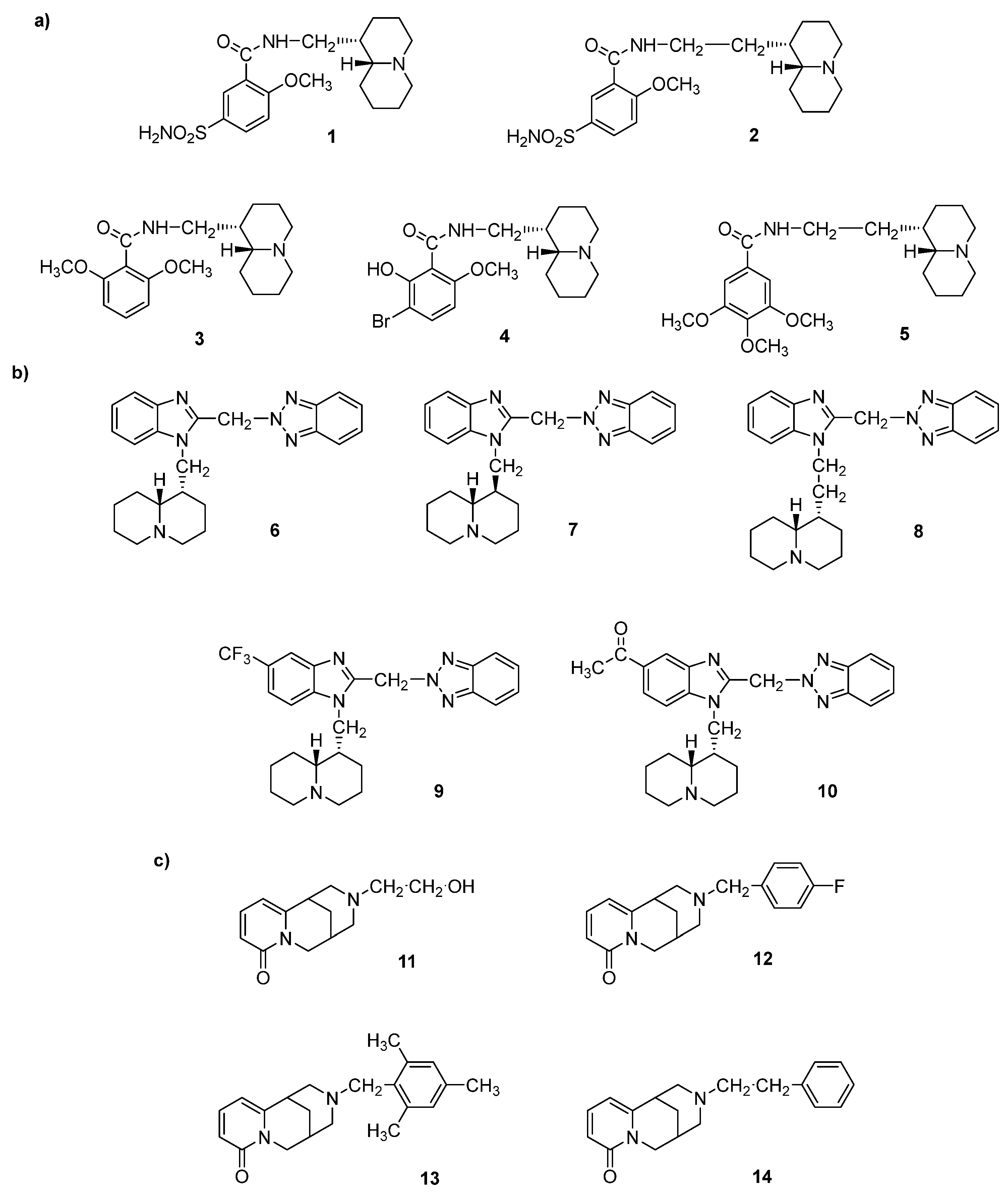

- (a)

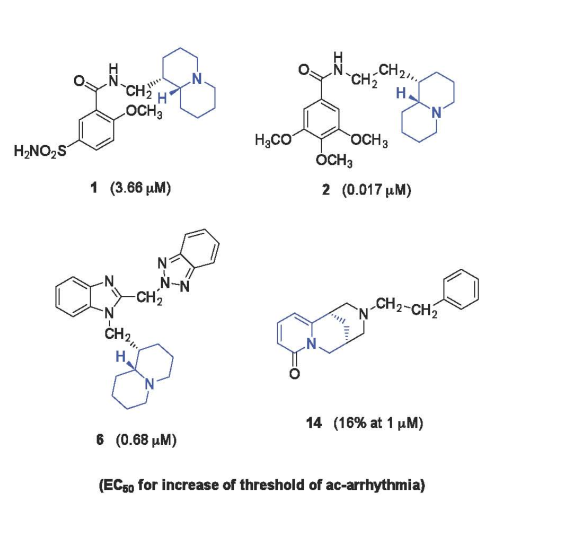

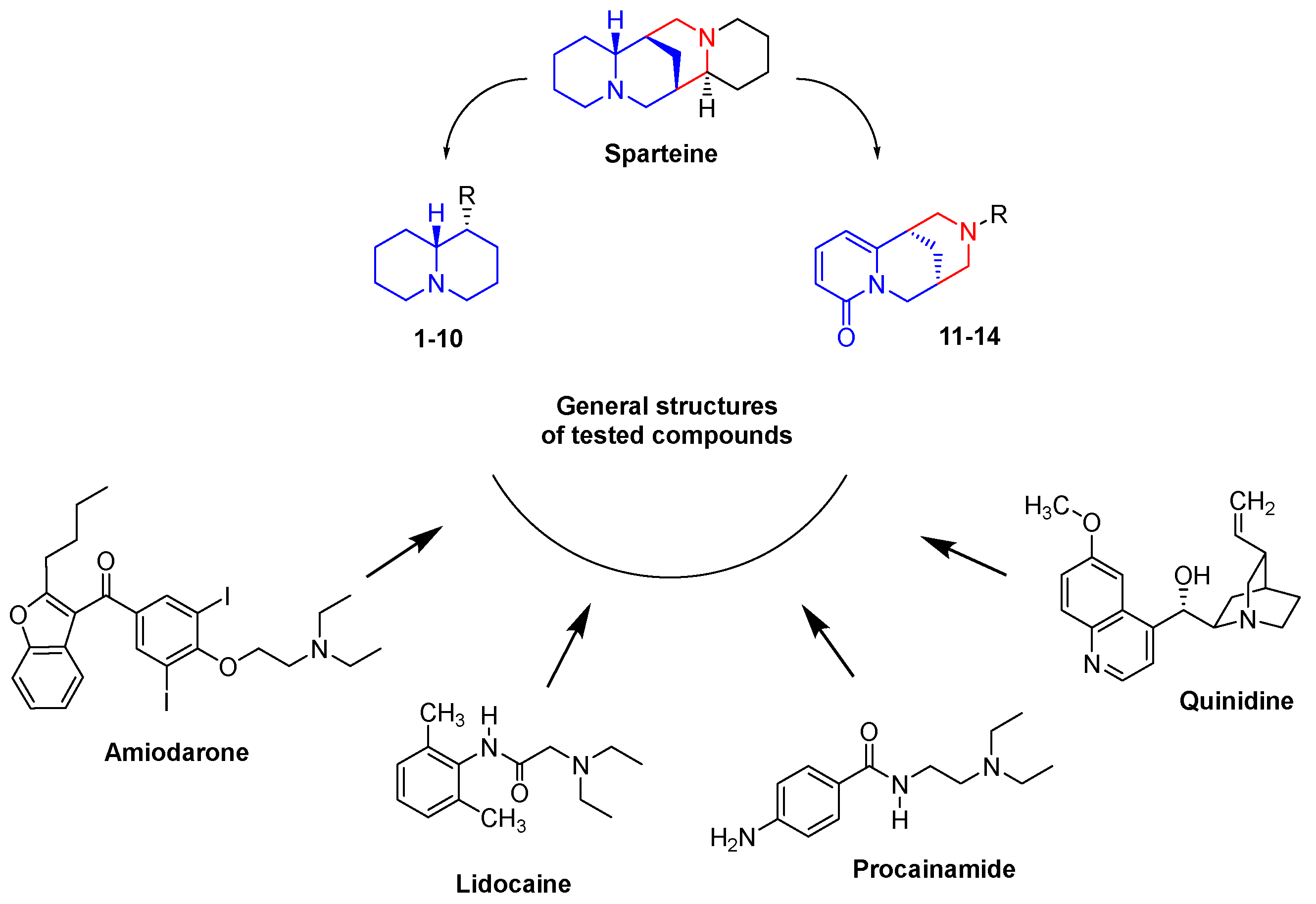

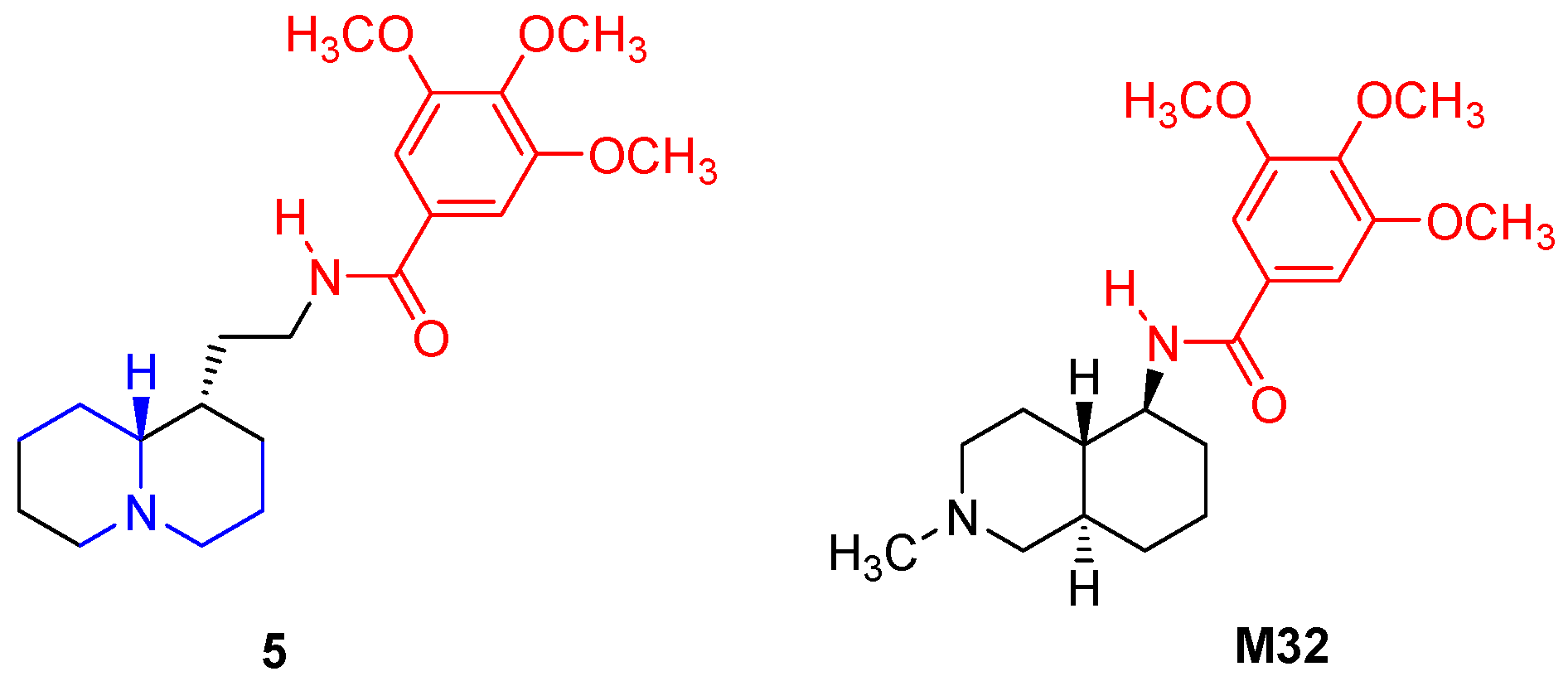

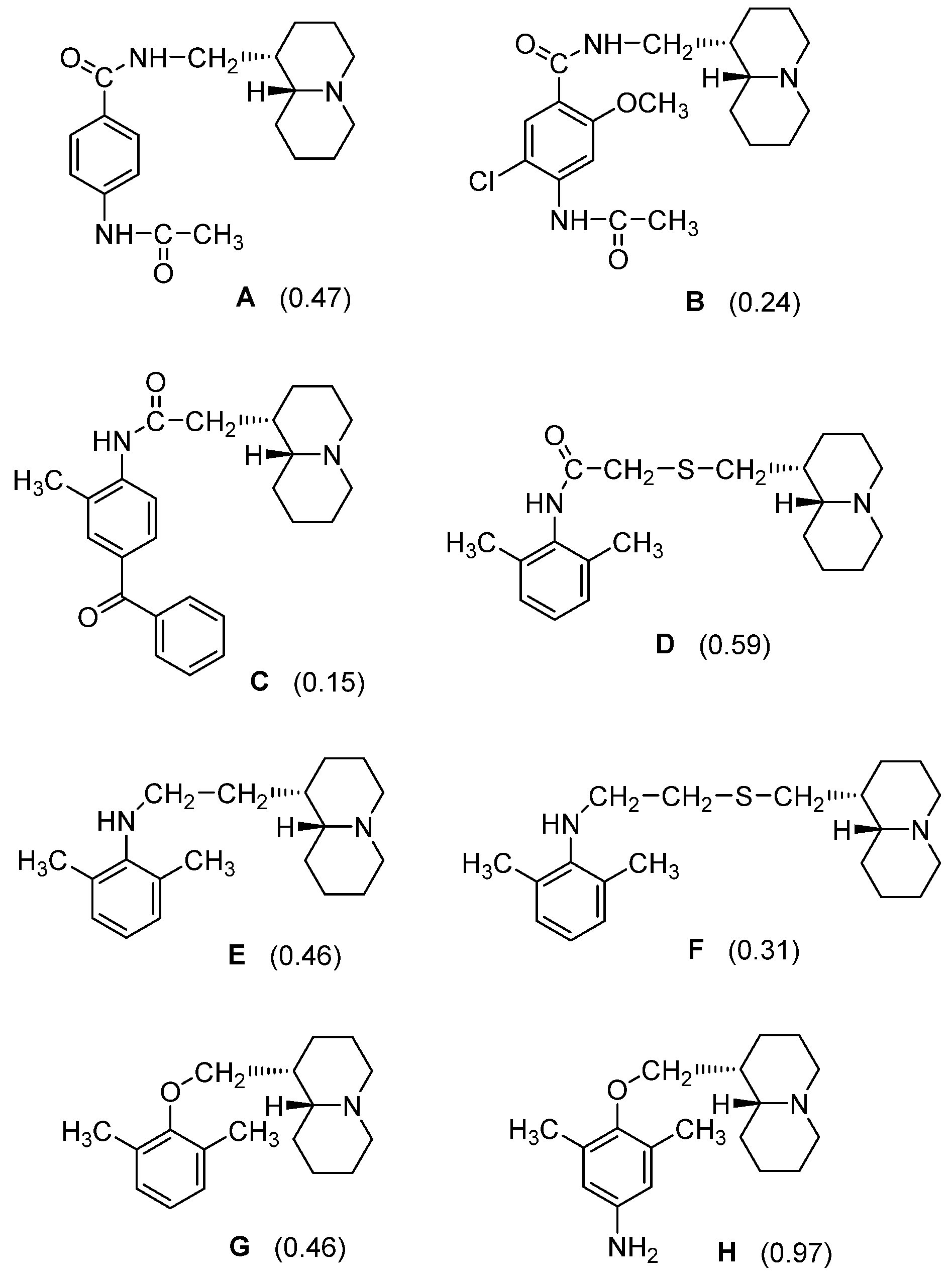

- N-(Quinolizidinyl-alkyl)-benzamides (1-5), related to the previously studied compounds A and B

- (b)

- (c)

- N-Substituted cytisines (11-14), characterized by the presence of three of the four rings of sparteine’s molecular scaffold. The investigated compounds were selected from a large number of cytisine derivatives previously studied by us as ligands for neuronal nicotine receptor and for various pharmacological activities (as anti-hypertensive and tobacco smoking cessation) [27,28,29,30].

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemistry

2.2.“. In Vitro” Activities

2.2.1. Heart Preparation

2.2.2. Aorta Preparation

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and discussion

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Vaughan Williams, E.M. Classification of antidysrhythmic drugs. Pharmacol Ther. B 1975, 1, 115–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughan Williams, E.M. Classifying antiarrhythmic actions: by facts or speculation. J. Clin. Pharmacol., 1992, 32, 964–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Wu, L.; Terrar, D.A.; Huang, C.L.-H. Modernized classification of cardiac antiarrhythmic drugs. Circulation, 2018, 138, 1879–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- a) Matyus, P.; Varro, A.; Papp, J.G.; Wamhoff, H.; Vargas, I.; Virag, L. Antiarrhythmic agents: current status and perspectives. Med Res. Rev., 1997, 17, 427-451. b) Geng, M.; Lin, A.; Nguyen, T.P. Revisiting antiarrhythmic drug therapy for atrial fibrillation: reviewing lessons learned and redefining therapeutic paradigms. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 581837.

- Sparatore, A.; Sparatore, F. Preparation and pharmacological activities of 10-homolupinanoyl-2-R-phenothiazines. Farmaco, 1994, 49, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Sparatore, A.; Sparatore, F. Preparation and pharmacological activities of homolupinanoyl anilides. Farmaco, 1995, 50, 153–166. [Google Scholar]

- Iusco, G.; Boido, V.; Sparatore, F. Synthesis and preliminary pharmacological investigation of N-lupinyl-2-methoxybenzamides. Farmaco, 1996, 51, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vazzana, I.; Budriesi, R.; Terranova, E.; Joan, P.; Ugenti, M.P.; Tasso, B.; Chiarini, A.; Sparatore, F. Novel quinolizidinyl derivatives as antiarrhythmic agents, J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 334–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasso, B.; Budriesi, R.; Vazzana, I.; Joan, P.; Micucci, M.; Novelli, F.; Tonelli, M.; Sparatore, A.; Chiarini, A.; Sparatore, F. Novel quinolizidinyl derivatives as antiarrhythmic agents. 2. Further investigation. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 4668–4677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E.L. McCawley, Cardioactive alkaloids. In: R.H.F. Manske Ed. “The alkaloids. Chemistry and Physiology. Vol. 5. Academic Press, New York, 1955, 93-97.

- Philipsborn, G.V.; Wilhelm, E.; Homburger, H. Untersuchungen zur Wirkung von Spartein am isolierten Vorhofmyokard von Maerschweinchen. Naunyn-Scmiedeberg’ Arch. Pharmacol. 1973, 277, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raschaek, M. Wirking von Spartein und Spartein derivate auf Herz und Kreislauf. Azneim. Forsch. 1974, 24, 753–759. [Google Scholar]

- Engelmann, K.; Radke, W.; Petter, A. Die Bedentung hydrophober Gruppen fur die antiarrhythmische eigenschaft alkylierte Sparteine. Arzneim. Forsch. 1974, 24, 759–764. [Google Scholar]

- Zetler, G.; Strubelt, O. Antifibrillatory, cardiovascular and toxic effects of sparteine, butylsparteine and pentylsparteine. Arznreim. Forsch. 1980, 30, 1497–1502. [Google Scholar]

- Gawall, V.S.; Simeonov, S.; Drescher, M.; Knott, T.; Scheel, O.; Kudolo, J.; Kahlig, H.; Hochenegg, U.; Roller, A.; Todt, H.; Maulide, N. C2-Modified sparteine derivatives are a new class of potentially long-acting sodium channel blockers. ChemMedChem Comm. 2017, 12, 1819–1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruenitz, P.C.; Mokler, C.M. Analogs of sparteine. 5. Antiarrhythmic activity of selected N,N’-disubstituted bispidines. J. Med. Chem. 1977, 20, 1668–1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruenitz, P.C.; Mokler, C.M. Anthiarrhythmic activity of some N-alkylbispidinebenzamides. J. Med. Chem. 1979, 22, 1142–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiraoka, M.; Sunami, A.; Tajima, K. Bisaramil, a new class I antiarrhythmic agent. Cardiovasc. Drug Rev. 1993, 11, 516–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoen, U.; Antel, J.; Bruckner, R.; Messinger, J.; Franke, R.; Gruska, A. Synthesis, pharmacological characterization, and quantitative structure-activity relationship analyses of 3,7,9,9-tetraalkylbispidines: Derivatives with specific bradycardic activity. J. Med. Chem. 1998, 41, 318–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takanaka, C.; Sarma, J.S.; Singh, B.N. Electrophysiological effects of ambasilide (LU 47110), a novel class II antiarrhythmic agent, on the properties of isolated rabbit and canine cardiac muscle. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1992, 19, 290–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pugsley, M.; Walker, M.J.A.; Garrison, G.B.; Howard, P.G.; Lazzara, R.; Patterson, E.; Penz, W.P.; Scherlag, B.J.; Berlin, K.D. The cardiovascular and antiarrhythmic properties of a series of novel sparteine analogs. Proc. West. Pharmacol. Soc. 1992, 35, 87–91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pugsley, M.K.; Saint, D.A.; Hayes, E.; Berlin, K.D.; Walker, M.J. The cardiac electrophysiological effects of sparteine and its analog BRD-1-28 in the rat. Eur. Pharmacol. 1995, 294, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomassoli, J.; Gundish, D. Bispidine as a priviliged scaffold. Curr. Topics in Med. Chem. 2016, 16, 1314–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagani, F.; Sparatore, F. Benzotriazolylalkyl-benzimidazoles and their dialkylaminoalkyl derivatives. Boll. Chim. Far. 1965, 104, 427–431. [Google Scholar]

- Paglietti, G.; Boido, V.; Sparatore, F. Dialkylaminoalkylbenzimidazoles of pharmacological interest. Farmaco, Ed.Sci. 1975, 30, 505–511. [Google Scholar]

- Tonelli, M.; Paglietti, G.; Boido, V.; Sparatore, F.; Marongiu, F.; Marongiu, E.; La Colla, P.; Loddo, R. Antiviral activity of benzimidazole derivatives. I. Antiviral activity of 1-substituted-2-[(benzotriazol-1/2-yl)methyl]benzimidazoles. Chem. Biodiversity 2008, 5, 2386–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Canu Boido, C.; Sparatore, F. Synthesis and preliminary pharmacological evaluation of some cytisine derivative. Farmaco 1999, 54, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canu Boido, C.; Tasso, B.; Boido, V.; Sparatore, F. Cytisine derivatives as ligands for neuronal nicotinic receptors and with various pharmacological activities. Farmaco 2003, 58, 265–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasso, B.; Canu Boido, C.; Terranova, E.; Gotti, C.; Riganti, L.; Clementi, F.; Artali, R.; Bombieri, G.; Meneghetti, F.; Sparatore, F. Synthesis, binding and modeling studies of new cytisine derivatives, as ligand for neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes. J. Med. Chem. 2009, 52, 4345–4357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, M.; Braida, D.; Pucci, L.; Manfredi, I.; Marks, M.J.; Wageman, C.R.; Grady, S.R.; Loi, B.; Fucile, S.; Fasoli, F.; Zoli, M.; Tasso, B.; Sparatore, F.; Clementi, F.; Gotti, C. CC4, a dimer of cytisine, is a selecctive partial agonist at alpha4beta2/alpha6beta2 nAChR with improved selectivity for tobacco smoking cessation. Brit. J. Pharmacol. 2013, 168, 835–849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iusco, G.; Boido, V.; Sparatore, F.; Colombo, G.; Saba, P.L.; Rossetti, Z.; Vaccari, A. New benzamide-derived 5-HT3 receptor antagonists which prevent the effects of ethanol on extracellular dopamine and fail to reduce voluntary alcohol intake in rats. Farmaco 1997, 52, 141–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boido, V.; Boido, A.; Boido Canu, C.; Sparatore, F. Quinolizidinylalkylamines with antihypertensive activity. Farmaco Ed.Sci. 1979, 34, 2–16. [Google Scholar]

- Borchard, U.; Bosken, R.; Greeff, K. Characterization of antiarrhythmic drugs by alternating current induced arrhythmias in isolated heart tissue. Arch. Int. Pharmacodyn. 1982, 256, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Bhatt, L.K.; Naudakumar, K.; Bodhankar, L.S. Experimental animal models to induce cardiac arrhythmia. Indian J. Pharmacol. 2005, 37, 348–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roselli, M.; Carrocci, A.; Budriesi, R.; Micucci, M.; Toma, M.; Di Cesare Mannelli, L.; Lovece, A.; Catalano, A.; Cavalluzzi, M.M.; Bruno, C.; De Palma, A.; Contino, M.; Perrone, M.G.; Colabufo, N.A.; Chiarini, A.; Franchini, C.; Ghelardini, C.; Habtemarian, S.; Lwentini, G. Synthesis, antiarrhythmic activity, and toxicological evaluation of mexiletine analogues. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 121, 300–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeka, K.; Marrazzo, P.; Micucci, M.; Ruparelia, K.C.; Arroo, R.R.J.; Macchiarelli, G.; Nottola, S.A.; Continenza, M.A.; Chiarini, A.; Angeloni, C.; Hrelia, S.; Budriesi, R. Activity af antioxidants from Crocus sativus L. petals. Preventive effects towards cardiovascular system. Antioxidants (Basel) 2020, 9(11), 1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R.J. Tallarida, R.B. Murray, Manual of pharmacologic calculations with computer programs, 2nd Ed. Springer Verlag: New York 1987.

- GraphPad Prism 4.03; Gaphpad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, http://www.graphpad.com.

- GraphPad Prism 3.02; Gaphpad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, http://www.graphpad.com.

- Ciofalo, E.; Levitt, B.; Roberts, J. Some aspects of the antiarrhythmic activity of reserpine. Brit J. Pharmacol. Chemother. 1966, 28, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, J.W. Antiarrhythmic activity of some isoquinoline derivatives determined by a rapid screening procedure in the mouse. J. Pharmacol. Expl. Therap. 1968, 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Mathison, J.W.; Gueldner, R.C.; Lawson, J.W.; Fawler, S.J.; Peters, E.R. The stereochemistry of 5-substituted decahydroisoquinolines and their antiarrhythmic activity. J. Med. Chem. 1968, 11, 997–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathison, S.W.; Pennington, R.J. Synthesis and antiarrhythmic properties of some 5-benzamido-2-methyl-trans-decahydroisoquinolines. J. Med. Chem. 1980, 23, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- a) Garzia, A. Pharmaceutical omega-(trimethoxybenzamido)fatty acids. DE 2034192 (1971), Chem. Abstr. 1971,75, 55230c. b) Istituto Chemioterapico Italiano, L’infarto del miocardio: terapia e profilassi delle complicanze con C-TRE (3,4,5-trimethoxybenzoyl-epsilon-aminocaproic acid). Lediberg s.n.c- Bergamo, 1971.

- Boido, V.; Sparatore, F. Derivatives of natural aminoalcohols and diamines of pharmacological interest. 5. Novel derivatives of lupinine and aminolupinane. Preliminary observations on their pharmacological activity. Ann. Chim. (Rome), 1969, 59, 526–538. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor, S.E.; Brown, R.A. The pharmacology of sulpiride – a dopamine receptor antagonist, Gen. Pharmacol. 1982, 13, 185–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvestre, J.S.; Prous, J. Comparative evaluation of hERG potassium channel blockade by antipsychotics. Methods Find Exp. Clin. Pharmacol. 2007, 29, 457–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Paulis, T.; Kumar, Y.; Johansson, L.; Raemsby, S.; Florvell, L.; Hall, H.; Aengeby-Muller, K.; Ogren, S.O. Potential neuroleptic agents. 3. Chemistry and antidopaminergic properties of 6-methoxysalicylamides. J. Med. Chem. 1985, 28, 1263–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paulis, T.; Kumar, Y.; Johansson, L.; Raemsby, S.; Hall, H.; Saellemark, M.; Aengeby-Muller, K.; Ogren, S.O. Potential neuroleptic agents. 4. Chemistry, behavioral pharmacology and inhibition of [3H]spiperone binding of 3,5-disubstituted N-[(1-ethyl-2-pyrrolidinyl)methyl]-6-methoxysalicylamides. J. Med. Chem. 1986, 29, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khisamatdinova, R.Y.; Yarmukhamedov, N.N.; Gabdrakhmanova, S.F.; Karachurina, L.T.; Sapozhnikova, T.A.; Baibulatova, N.Z.; Baschenko, N.Z.; Zarudi, F.S. Synthesis and antiarrhythmic activity of N-(2-hydroxyethyl)cytisine hydrochloride and 3-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1,5-dinitro-3-azabicyclo-[3.3.1]non-3-ene hydrochloride. Pharmaceutical Chem. J. 2004, 38, 311–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishkin, D.V.; Shaimuratova, A.R.; Lobov, A.N.; Baibulatova, N.Z.; Spirikhin, L.; Yunusov, M.S.; Makara, N.S.; Baschenko, N.Z.; Dokichev, V.A. Synthesis and biological activity of N-(2-hydroxyethyl)cytisine derivatives. Chem. Nat. Comp. 2007, 43, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsipisheva, J.P.; Kovolskaya, A.V.; Khalilova, I.U.; Bakhtina, Y.Y.; Khisamutdinova, R.; Gabdrakhmanova, S.F.; Lobov, A.N.; Zarudi, F.S.; Yunusov, S.Y. New 12-N-β-Hydroxyethylcytisine derivatives with potential antiarrhythmic activity. Chem Nat. Comp. 2014, 56, 333–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Bhandohal J.S.; Visco, F.; Pekler, G.; Mushiyev, S. Gastrocardiac syndrome A forgotten entity. Am. J. Emergency Med. 2018, 1525e5-1525e7.Author 1, A.; Author 2, B. Title of the chapter. In Book Title, 2nd ed.; Editor 1, A., Editor 2, B., Eds.; Publisher: Publisher Location, Country, 2007; Volume 3, pp. 154–196. [CrossRef]

|

Compd |

Max% increase of threshold of ac-arrhythmia after pretreatment with compounda (M ± SEM) |

EC50b (μM) |

95% conf lim (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amiodarone | 10 ± 0.5c | ||

| Lidocaine | 34 ± 2.6 | ||

| Procainamide | 11 ± 0.4 | ||

| Quinidine | 69 ± 0.4 | 10.26 | 8.44 – 12.46 |

| N-(Quinolizidinyl-alkyl)-benzamides related compds | |||

| 1 | 59 ± 1.7 | 3.66 | 2.10 – 6.38 |

| 2 | 9 ± 0.6d | ||

| 3 | 17 ± 0.4e | ||

| 4 | 92 ± 1.3 | 10.67 | 7.56 – 14.91 |

| 5 | 104 ± 3.4 | 0.017 | 0.0068 – 0.046 |

| 1-(Quinolizidinyl)alkyl-2-(benzotriazol-2-yl)methyl benzimidazoles related compds | |||

| 6 | 75 ± 1.8d | 0.68 | 0.47 – 0.98 |

| 7 | 37 ± 3.4f | ||

| 8 | 39 ± 1.7d | ||

| 9 | 16 ± 0.9 | ||

| 10 | 20 ± 0.4 | ||

| N-Substituted cytisines related compds | |||

| 11 | 26 ± 0.3c | ||

| 12 | 4 ± 0.2 | ||

| 13 | 27 ± 1.3c | ||

| 14 | 16 ± 0.7g | ||

| Heart | Aorta | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left atria | Right atria | ||||||

| Negative inotropy | Negative chronotropy | Vasorelaxant | |||||

| Compd | IAa (M ± SEM) |

EC50b (μM) |

95% conf lim (μM) |

IAc (M ± SEM) |

EC50b (μM) |

95% conf lim (μM) |

IAd (M ± SEM) |

| Amiodarone | 30 ± 2.6e | 72 ± 4.5e | 14.95 | 11.07 – 20.16 | 3 ± 0.1g | ||

| Lidocaine | 88 ± 3.0 | 0.017 | 0.012 – 0.024 | 29 ± 0.9#,j | 14 ± 0.9 | ||

| Procainamide | 92 ± 1.4f | 0.014 | 0.011 – 0.017 | 9 ± 0.6#,e | 3 ± 0.2 | ||

| Quinidine | 71 ± 3.6g | 3.38 | 2.69 – 4.25 | 86 ± 0.5 | 25.31 | 14.45 – 44.32 | 30 ± 1.6g |

| N-(Quinolizidinyl-alkyl)-benzamides related compds | |||||||

| 1 | 92 ± 1.4h | 0.037 | 0.027 – 0.051 | 24 ± 1.3k | 5 ± 0.2 | ||

| 2 | 93 ± 1.4i | 0.0091 | 0.002 – 0.021 | 2 ± 0.1h | 3 ± 0.2 | ||

| 3 | 75 ± 2.3i | 0.011 | 0.0079 – 0.014 | 25 ± 1.6# | 2 ± 0.1 | ||

| 4 | 98 ± 1.3 | 0.021 | 0.016 – 0.027 | 46 ± 2.2 | 36 ± 1.3 | ||

| 5 | 85 ± 2.2 | 0.050 | 0.035 – 0.071 | 25 ± 0.9h | 22 ± 1.6 | ||

| 1-(Quinolizidinyl)alkyl-2-(benzotriazol-2-yl)methyl benzimidazoles related compds | |||||||

| 6 | 91 ± 2.4h | 0.046 | 0.035 – 0.061 | 67 ± 0.7 | 11.15 | 9.05 – 13.74 | 25 ± 1.7g |

| 7 | 93 ± 2.7j | 0.083 | 0.064 – 0.11 | 69 ± 1.3h | 0.49 | 0.43 – 0.65 | 16 ± 1.1 |

| 8 | 92 ± 1.3 | 0.022 | 0.015 – 0.031 | 83 ± 2.4 | 0.019 | 0.014 – 0.026 | 19 ± 1.2 |

| 9 | 87 ± 1.1j | 0.056 | 0.042 – 0.076 | 44 ± 1.5h | 24 ± 1.6 | ||

| 10 | 94 ± 3.4 | 0.021 | 0.014 – 0.032 | 22 ± 1.2e | 11 ± 1.0 | ||

| N-Substituted cytisines related compds | |||||||

| 11 | 86 ± 2.2h | 0.14 | 0.095 – 0.20 | 35 ± 1.4k | 0.3 ± 00.1 | ||

| 12 | 92 ± 1.8h | 0.018 | 0.013 – 0.026 | 26 ± 1.9 | 25 ± 1.4 | ||

| 13 | 87 ± 1.4h | 0.044 | 0.028 – 0.068 | 20 ± 0.3h | 32 ± 2.2 | ||

| 14 | 71 ± 0.7i | 0.016 | 0.0081 – 0.023 | 47 ± 1.1e | 20 ± 1.6 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).