1. Introduction

Alopecia, also known as hair loss, refers to the gradual thinning or complete loss of hair[

1]. Hair loss can occur for a variety of reasons, including genetic factors, hormonal changes, nutritional deficiencies, stress, irregular lifestyle habits, and medication side effects [

2,

3,

4]. The most common form of hair loss is androgenic alopecia (AGA), which occurs in over 50% of men but can also occur in women [

5,

6]. AGA causes hair to become thinner and shorter, and can affect all hair on the body, not just the scalp [

7,

8,

9]. AGA is caused by the role of androgen hormones. AGA starts with the hair gradually thinning and shortening, ultimately leading to complete hair loss, and typically begins around the temples and progresses to the top of the scalp [

10,

11,

12]. While the exact cause of AGA is not fully understood, it is believed that inhibition of hair growth through the androgen receptor (AR) signaling system is the main cause [

12,

13,

14].

Androgens are hormones that regulate reproductive development and function in both males and females, and in men they are primarily produced in the testes [

15,

16]. Androgens are composed of several chemical substances, including testosterone, androstenedione, dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA), and dihydrotestosterone (DHT). DHT is the active metabolite of testosterone [

15,

17]. Testosterone is one of the major hormones that influences sex differentiation and maintenance, reproductive function, and muscle development [

18]. DHT is produced when testosterone is converted by an enzyme called 5α-reductase [

19]. This enzyme is expressed mainly in the scalp and prostate, and in some other tissues that promote DHT synthesis [

20,

21]. Therefore, DHT is mainly produced in the scalp and prostate, and plays an important role in male development and maintenance. DHT stimulates prostate growth and development, and inhibits the action of the female hormone estrogen, thereby affecting male reproductive function and development [

22]. In addition, DHT is one of the causes of hair loss. Male pattern baldness is thought to occur due to genetic factors and excessive DHT production in the scalp [

23]. If a specific genetic mutation causes excessive production of DHT in the scalp, the DHT can act on the hair follicles, causing the diameter of the hair to become smaller and thinner, ultimately leading to hair loss [

11,

24,

25]. Androgens also have an impact on hair growth, as the cells in the hair follicle in the scalp have ARs. When androgens bind to these receptors, they trigger signals that inhibit hair growth, leading to gradual thinning and shortening of androgen-sensitive hair until they no longer grow [

25]. This is the main mechanism behind AGA, and changes in the AR signaling system are one of the contributing factors.

AGA is hair loss caused by the influence of androgen hormones on genetically healthy hair. The most commonly used treatments for AGA are flutamide and finasteride, which inhibit ARs to prevent hair loss [

26]. Flutamide is an AR antagonist that promotes hair growth by acting on ARs [

27,

28]. This drug can be applied topically to the scalp or administered by injection. Finasteride inhibits 5α-reductase and prevents the conversion of testosterone to DHT, which helps to suppress AGA, particularly in the treatment of male pattern baldness [

26,

29]. However, both finasteride and flutamide can have potential side effects. Finasteride can cause sexual dysfunction, breast enlargement, and other side effects, while flutamide may have an impact on the fetus of pregnant women when taken orally, making it restricted for use by pregnant women [

30,

31,

32]. Hair follicles are complex structures that undergo continuous cycles of growth and shedding, which are regulated by a collection of genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors. These cycles are divided into four phases: anagen, catagen, telogen, and exogen [

33]. During the anagen phase, the hair follicle actively grows, with new hair cells being produced at the base of the follicle that push older cells up and out of the skin surface. This phase can last anywhere from a few months to several years, depending on the location of the hair on the body. The catagen phase is a short transitional phase that marks the end of the anagen phase. During this phase, the hair follicle stops growing and begins to shrink, as the hair matrix, human dermal papilla (HDP) cells, inner root sheath keratinocyte, and outer root sheath keratinocytes undergo programmed cell death (apoptosis) [

34,

35]. The telogen phase is a resting phase that follows the catagen phase. During this phase, the hair follicle is dormant and the hair shaft is fully formed, but not actively growing. This phase typically lasts for several months. Finally, during the exogen phase, the old hair shaft is shed from the skin surface, allowing a new hair cycle to begin. This phase is also known as the shedding phase, and it can last several weeks [

36].

This study investigated the significant changes that occur during the telogen phase of the hair growth cycle. Telogen is regulated by a variety of genetic, hormonal, and environmental factors, and compared to the anagen phase, it shows a dramatic decrease in the Bcl2/Bax ratio, leading to cell apoptosis. As a result, old hair falls out, and through the resting and growth phases, new hair is generated.

2. Results

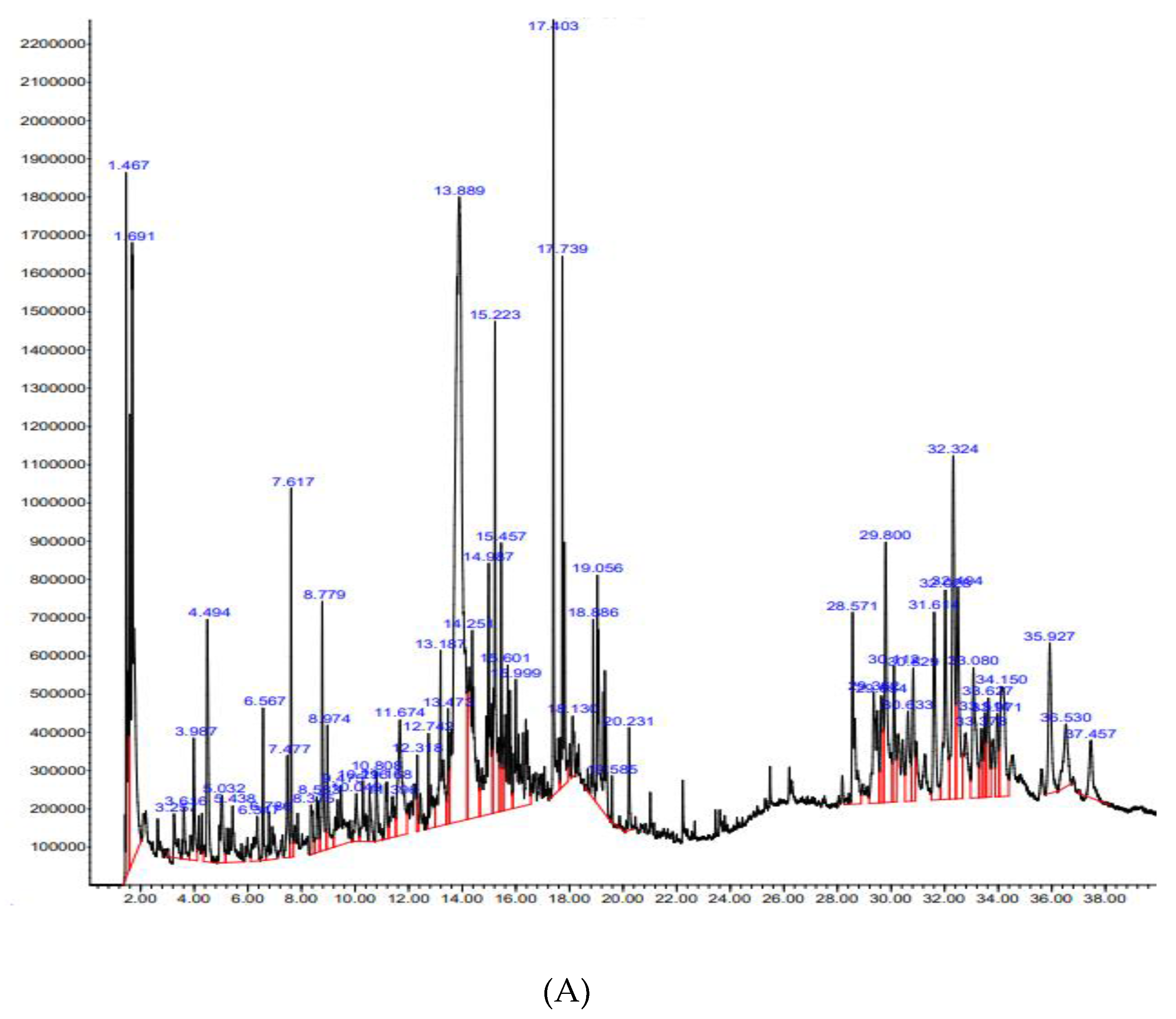

2.1. Analysis of Components Using Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GC-MS)

GC-MS analysis of Nk-EE revealed that the most abundant compound was silver butanoate, followed by tricarbonyl(trimethylphosphine)nickel, 4-o-(β-d-glucopyranosyl)-d-glucopyranose, and others. All compounds have been listed in

Table 1.

Figure 1.

Phytochemical analysis of Nk-EE using GC-MS.

Figure 1.

Phytochemical analysis of Nk-EE using GC-MS.

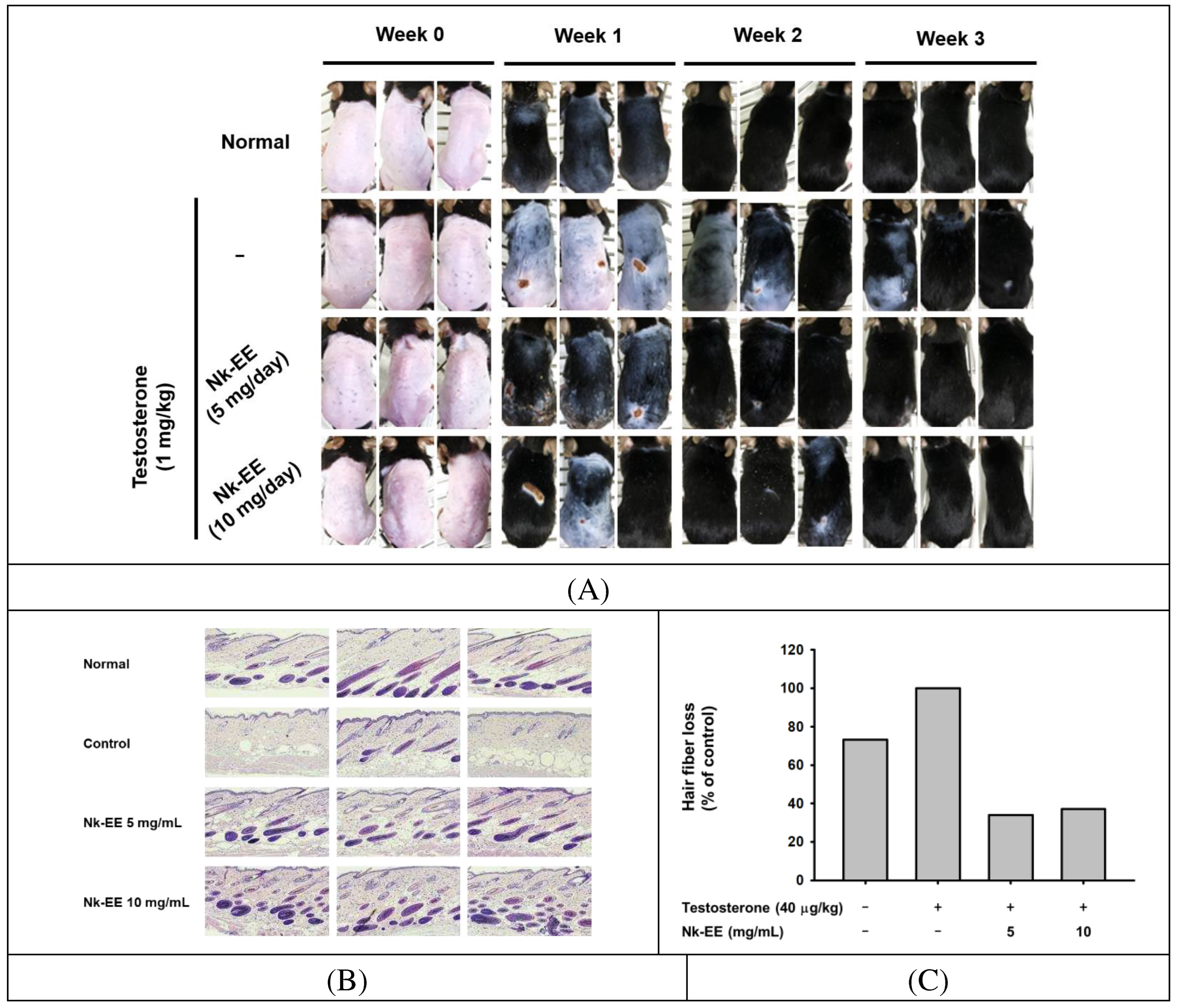

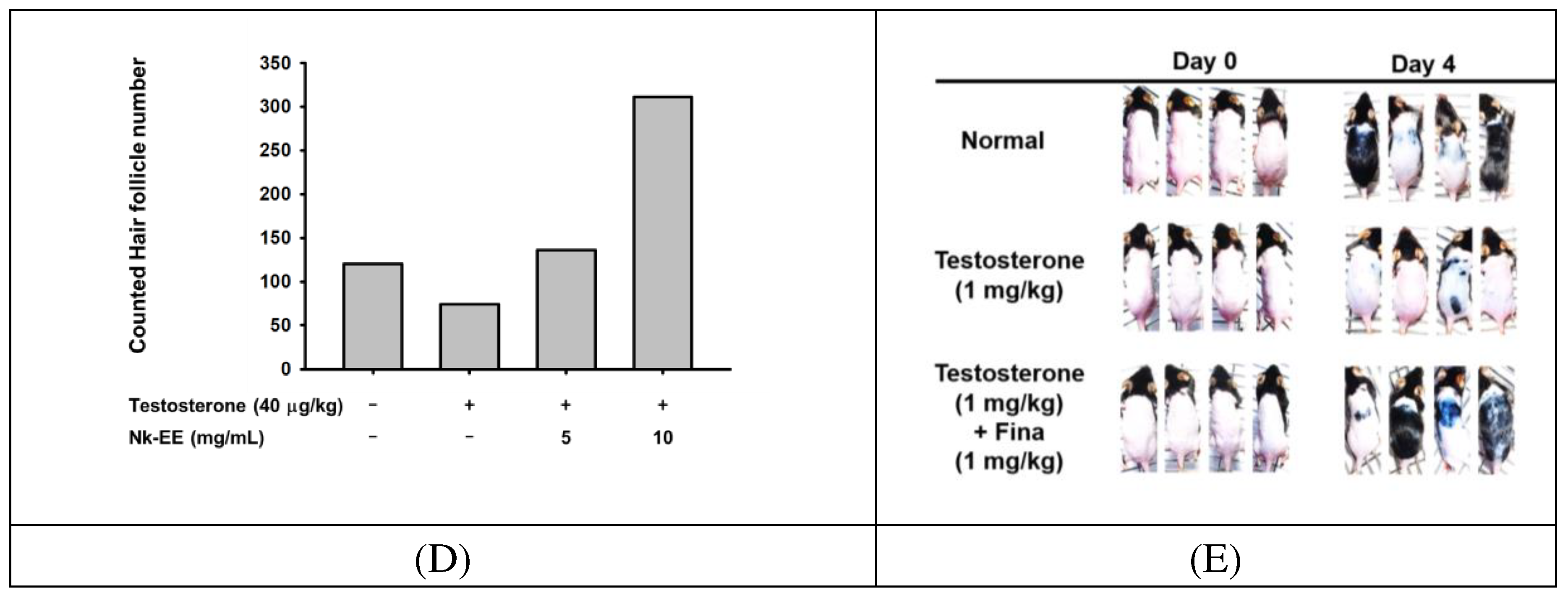

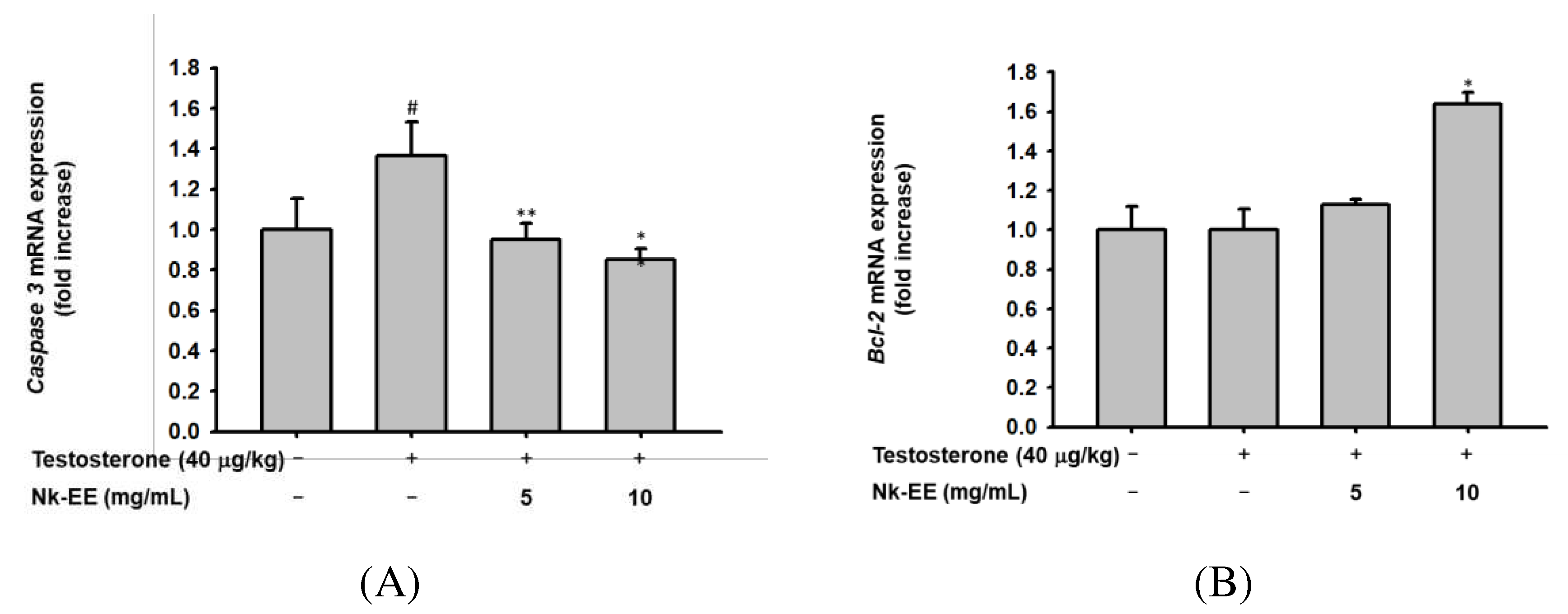

2.3. Prevention or Inhibition of Hair Loss by Nk-EE in an AGA Mouse Model

To further analyze the preventive and inhibitory effects of alopecia, we analyzed an AGA mouse model. We injected testosterone once each week and applied Nk-EE to the skin at a dosage of 5 or 10 mg daily. We then took pictures each week to analyze the amount and growth of hair. Our analysis revealed that Nk-EE increased hair growth, which was evident during the first, second, and third weeks (

Figure 3A). Next, we sacrificed the mice at week 3, extracted their skin, and performed histological analysis by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. The results showed a significant decrease in the number of hair follicles, including those containing hair, in the group treated with testosterone, while Nk-EE treatment increased the number of hair follicles (

Figure 3B and C). For a more detailed analysis, we counted the number of hair follicles with or without hair in all photographs and presented them graphically. As expected, Nk-EE remarkably enhanced hair follicle numbers (

Figure 3D). Meanwhile, finasteride also showed remarkable induction of hair growth at day 4, while testosterone-treated control group did not show clear hair growth (

Figure 3E).

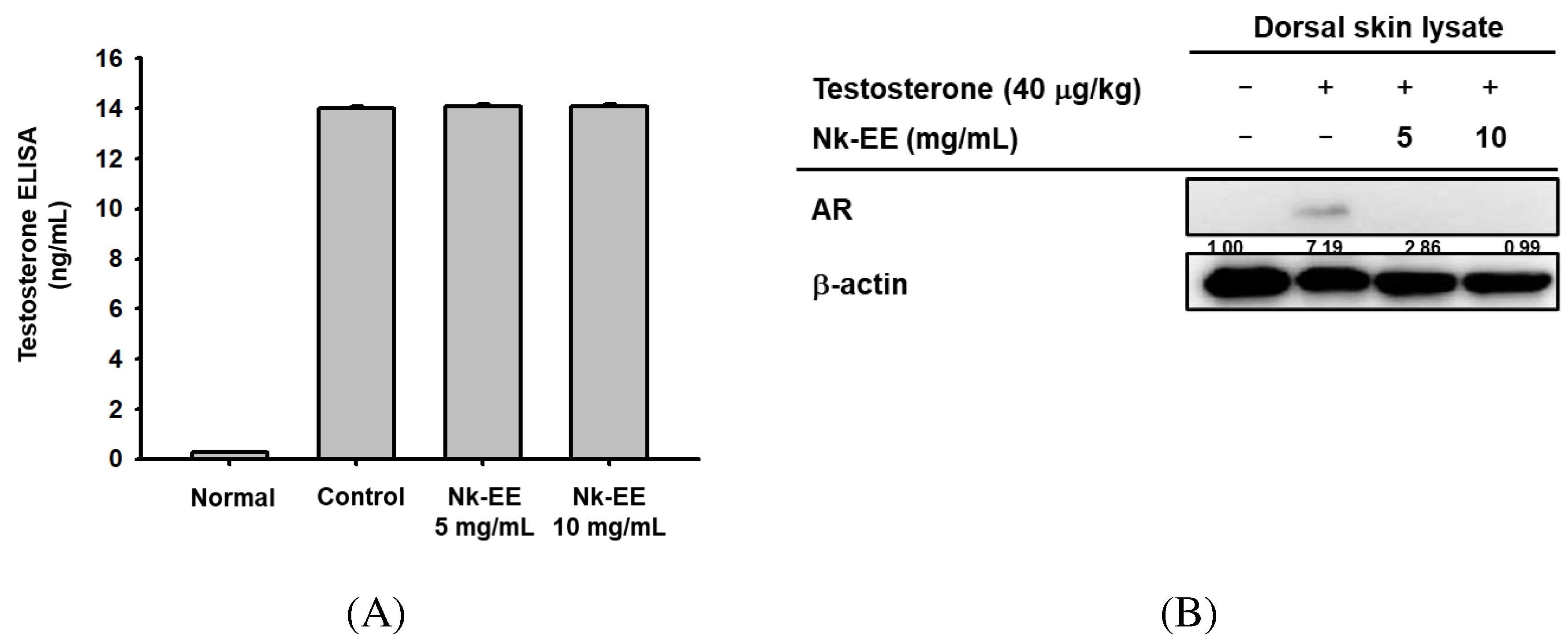

2.4. Inhibition of AR Activity by Nk-EE and its Mechanism

To analyze the levels of testosterone, we collected blood from the AGA mouse models and extracted serum for testosterone ELISA analysis. The analysis showed high concentrations of testosterone in all groups except for the control group (

Figure 4A). Additionally, to indirectly analyze the activity of testosterone, we performed western blotting analysis using mouse skin tissue to analyze the activity of AR. The results showed that the activity of AR decreased with Nk-EE treatment (

Figure 4B). Furthermore, we analyzed the gene expression of TGF-1B and DKK-1 in the AR signaling pathway of skin tissue using real-time PCR analysis. The results showed that Nk-EE treatment suppressed the expression of the TGF-1B and DKK-1 genes (

Figure 4C, D).

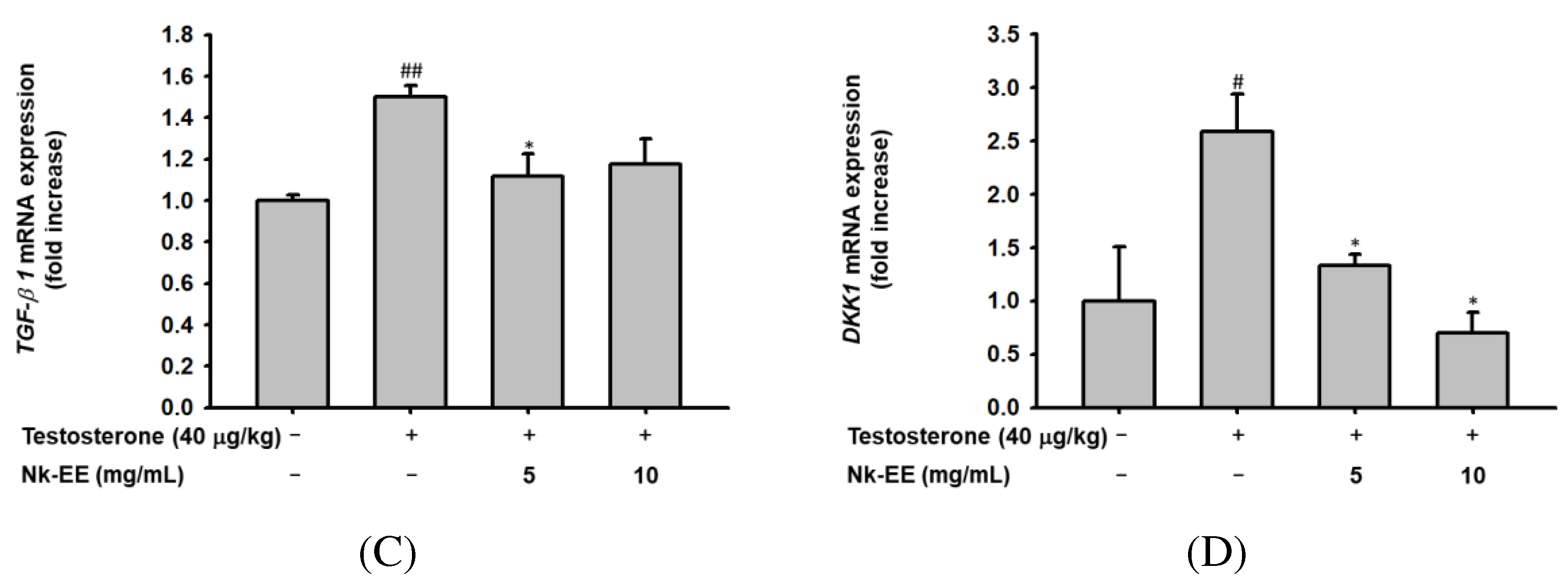

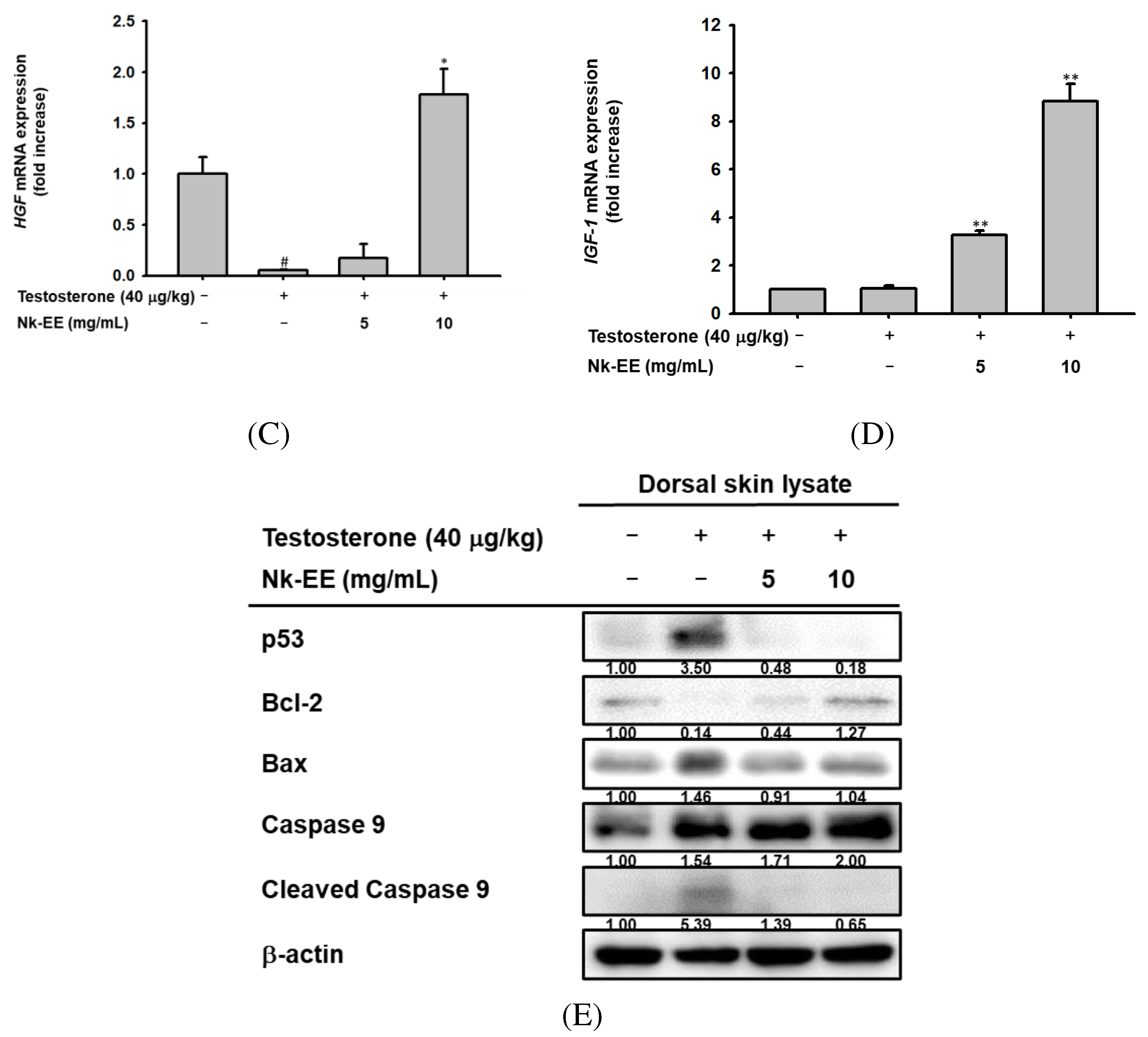

2.5. Inhibition of Cell Apoptosis by Nk-EE and the Underlying Mechanism

We analyzed the effects of Nk-EE on inhibiting cell death and promoting the growth of hair follicle cells. Using skin tissue from the AGA mouse model, we used real-time PCR analysis to confirm the expression of genes related to cell death, including Bcl2 and Caspase-3, as well as growth-regulating genes HGF and IGF-1. The results indicated that Nk-EE treatment decreased the expression of the Caspase-3 gene related to cell death (

Figure 5A). Furthermore, it was confirmed that the expression of the Bcl2 gene, which inhibits cell death, was increased by Nk-EE treatment (

Figure 5B). The expression of HGF and IGF-1 genes related to hair follicle cell growth [

37,

38,

39] was upregulated by Nk-EE treatment. In addition, proteins involved in cell death were analyzed with western blotting analysis. Nk-EE treatment decreased the expression of proteins such as p53, BAX, and caspase-9, which are involved in cell death [

37,

40], while increasing the expression of the Bcl-2 protein (

Figure 5E).

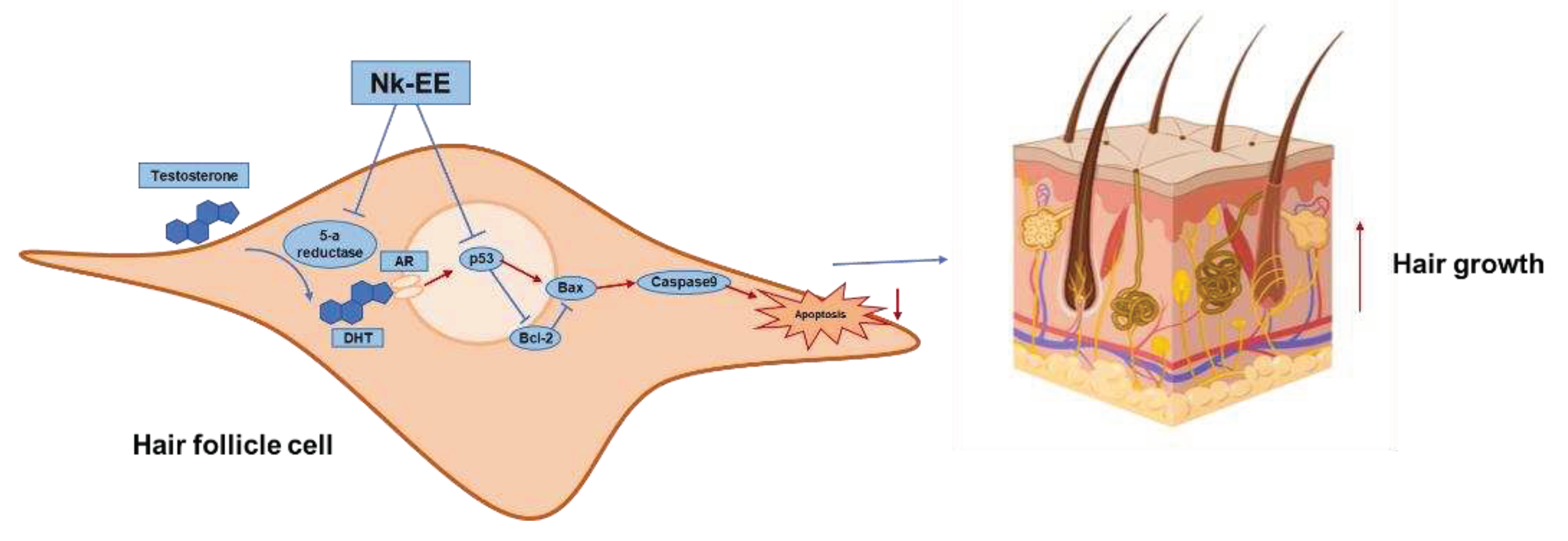

3. Discussion

The purpose of our study was to investigate the potential benefits of Nk-EE in preventing and inhibiting hair loss in an AGA mouse model. AGA is a common type of hair loss that affects both men and women, and is caused by the hormone DHT, which is derived from testosterone. To test the effects of Nk-EE in alopecia, we conducted in vitro and in vivo experiments. In our in vitro experiments, we used cultured HDP cells. In our in vivo experiments, we used a mouse model of AGA.

Testosterone can prevent the normalization of the Bcl2/Bax ratio or lengthen the telogen phase through dysregulation, which disrupts the balance of hair growth stages and induces alopecia [

41]. To prevent or inhibit such alopecia, we analyzed several biomarkers and confirmed that Nk-EE is effective in suppressing hair loss or promoting hair growth. We confirmed that Nk-EE stimulates growth by significantly increasing the expression of the growth factor HGF and IGF genes in HDP cells and by promoting cell growth through the downregulation of Caspase-9 protein expression induced by BAX protein while inhibiting cell death. In contrast, we found that Nk-EE decreases the survival of prostate cancer cells that use the hormone testosterone as a growth factor. Furthermore, the results showed that by inhibiting the activation of the AR signaling pathway induced by testosterone, Nk-EE can not only promote cell growth and inhibit cell death in hair follicle cells but also inhibit the effects induced by testosterone. These effects suggested that Nk-EE has potential value as a material for treating or preventing alopecia.

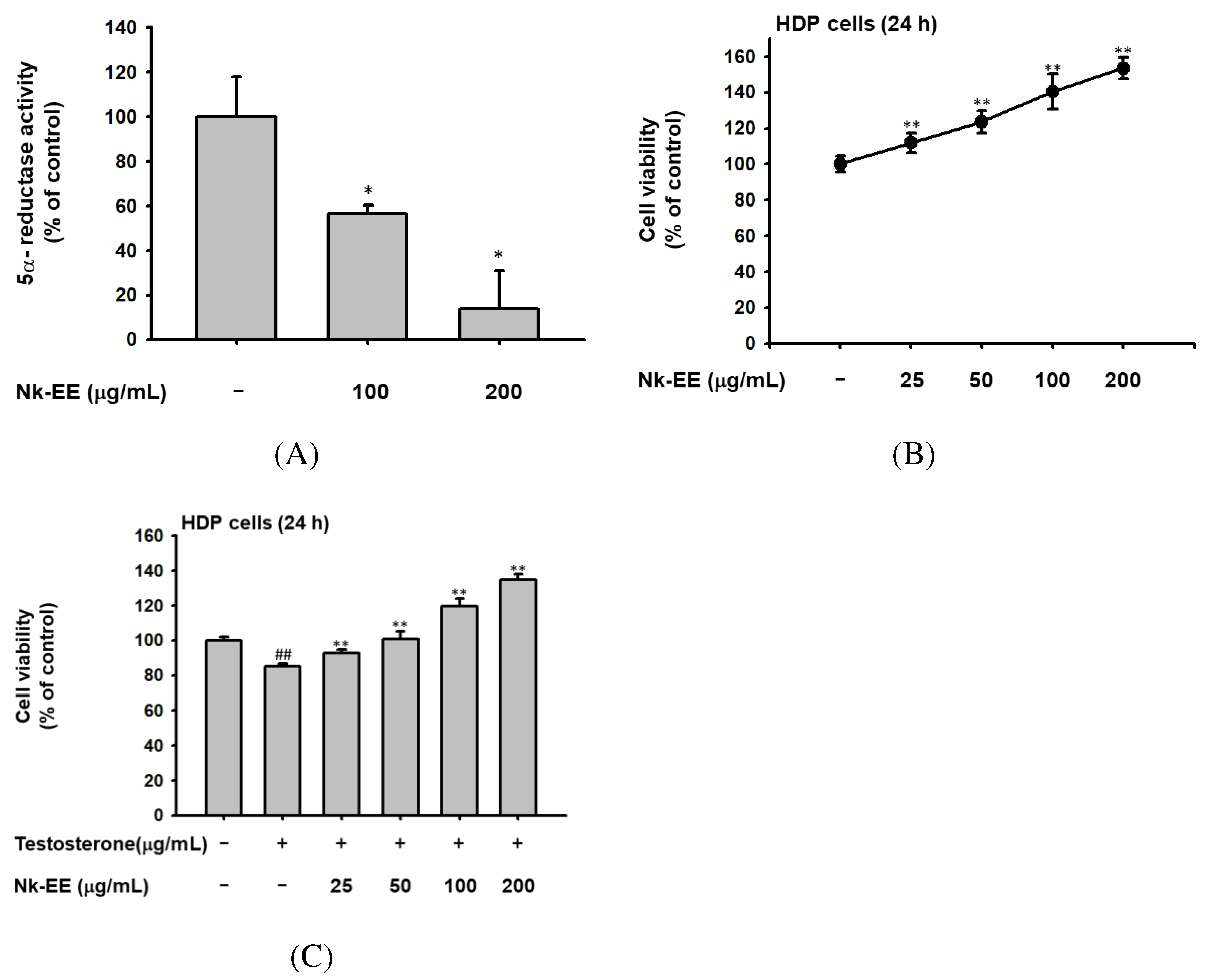

Based on our study, we have found that Nk-EE has the potential to offer several benefits in terms of preventing hair loss and promoting hair growth. Our results suggest that Nk-EE can inhibit the activity of 5α-reductase, an enzyme responsible for converting testosterone to DHT. Moreover, we have observed that Nk-EE can stimulate the growth of HDP cells. These findings indicate that Nk-EE has the potential to promote the overall health and growth of hair follicles, thereby positively impacting hair growth and preventing alopecia. Furthermore, our experiments demonstrated that Nk-EE may increase hair growth and the number of hair follicles, while also decreasing the expression of genes related to cell death and increasing the expression of genes related to hair follicle cell growth. These findings suggest that Nk-EE may have a positive effect on the regulation of hair follicle growth and may help to prevent alopecia.

Our research suggests that Nk-EE's mechanism of action involves inhibiting and regulating a variety of genes and proteins involved in the AR signaling pathway as well as cell death and growth. We observed that Nk-EE inhibited AR activity by decreasing the expression of two key genes involved in the AR signaling pathway, TGF-1B and DKK-1 [

42]. By reducing the expression of these genes, Nk-EE may reduce the activation of the AR signaling pathway, ultimately leading to decreased cell proliferation and growth. In addition, our findings suggest that Nk-EE may also inhibit cell apoptosis (cell death) by modulating the expression of certain genes. Specifically, Nk-EE decreased the expression of the Caspase-3 gene, which is involved in promoting cell apoptosis, while increasing the expression of the Bcl2 gene, which is involved in inhibiting cell apoptosis [

43]. This dual effect may lead to an overall reduction in cell death.

Moreover, Nk-EE regulated the expression of other proteins involved in cell death and growth. For example, Nk-EE increased the expression of the HGF and IGF-1 genes, which are involved in promoting cell growth and survival, while decreasing the expression of the p53 and BAX genes, which are involved in promoting cell death [

44]. Additionally, Nk-EE regulated the expression of the caspase-9 gene, which is involved in promoting apoptosis. Overall, these changes in protein expression contribute to Nk-EE's effects on cell growth and death.

Our study provides compelling evidence that Nk-EE may hold significant promise as a potential treatment for hair loss. The mechanisms of action identified in our research suggest that Nk-EE could be effective in inhibiting the AR signaling pathway and promoting hair growth by regulating cell death and growth pathways [

45]. However, further studies are necessary to confirm the safety and efficacy of Nk-EE in human clinical trials. In particular, the optimal dosage and duration of treatment need to be investigated to ensure that the benefits of the treatment outweigh any potential risks or side effects. In addition to efficacy and safety considerations, future research should also aim to gain a deeper understanding of the underlying mechanisms of Nk-EE in the context of hair growth. This could involve further investigation into the specific genes and proteins that are targeted by Nk-EE as well as the interactions between these molecular pathways. Overall, while our study provides promising initial evidence of the potential of Nk-EE as a hair loss treatment, further research is needed to fully realize its therapeutic potential and to advance our understanding of the underlying mechanisms of hair growth and loss.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials and Reagents

The following reagents were purchased from the mentioned suppliers: testosterone, ethanol, of 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT), finasteride, and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) from Sigma-Aldrich in St. St. Louis, MO, USA; trypsin (0.25%) from HyClone Laboratories in Logan, UT, USA; HDP cells, which are a human hair follicle dermal papilla cell line, and CEFOgro™ HDP Growth Medium were obtained from CEFO Co. in Seoul, Korea; and phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) from Samchun Pure Chemical Co. in Gyeonggi-do, Korea. The antibodies for Bcl-2, Bax, caspase 3, and cleaved caspase 3 were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology in Beverly, MA, USA, and the antibodies for b-actin and AR were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. in Dallas, TX, USA. TRIzol reagent was bought from Molecular Research Center, Inc. in Cincinnati, OH, USA.

4.2. Preparation of Nepenthes Kampotiana Lecomte Ethanol Extract (Nk-EE) and GC-MS

We obtained Nk-EE from the National Institute for Biological Resources in Incheon, Korea. To prepare the sample, the whole plant was pulverized and granulated for 24 h at 20–22 °C using 70% ethanol. The ethanol was completely removed using a rotary flash evaporator (Büchi Labortechnik AG, Flawil, Switzerland) for filtering and concentrating under a vacuum of 10 hPa at 40 °C. The resulting aqueous solution was further evaporated at 5 mTorr and -85 °C, and the extract was subsequently lyophilized. We conducted GC-MS analysis at the Cooperative Center for Research Facilities of SKKU located in Gyeoggido, Korea.

4.3. Cell Culture and Cell Viability Assay

The HDP cells used in this study were cultured in HDP growth medium at 37 °C. They were incubated with 5% CO2. HDP cells were seeded in 96-well plates at a density of 1 × 104 cells/mL. Then, Nk-EE (0–200 μg/mL) was added to each well. After incubation for 24 h, 10 μL of MTT solution was added to the cells, which were then further cultured for 3 h. Next, 100 μL of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) in 0.01 M HCl was added to each well, and the cells were incubated for 24 h to stop the reaction and dissolve the formazan. Finally, the absorbance of the MTT formazan was measured at 540 nm.

4.4. Binding affinity calculations with Autodock Vina

3D structure of 5α-reductase 2 was obtained from PDB database, and 2D structure of each compound identified in Nk-EE was acquired from PubChem. 2D structure of each compound was modified with PyMOL. The binding affinity was calculated by Autodock Vina.

4.5. Animals and Testosterone-Induced Mouse Models (AGA Mouse Models)

We obtained 5-week-old male C57BL/6 mice and 10-week-old male Sprague Dawley rats from Orient Bio (Iksan, Korea). They were housed in plastic cages with plenty of water and food. Our study followed the guidelines set forth by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Sungkyunkwan University (SKKUIACUC-2021-07-18-1). We divided the male C57BL/6 mice (n = 6) into four groups: the Normal group, the Vehicle (PBS: DMSO = 1:1) control group, the 1 mg/kg/week testosterone + Nk-EE 5 mg/day group, and the 1 mg/kg/week testosterone + Nk-EE 10 mg/day group. To confirm the hair-growth-promoting effect of Nk-EE, we applied hair removal cream and shaved the dorsal part of each mouse seven and three days before the first testosterone treatment. We subcutaneously injected 1 mg/kg of testosterone dissolved in sesame oil once per week for 3 weeks. During the three weeks of testosterone injection, we applied Nk-EE (5 and 10 mg/kg) diluted with PBS and DMSO (ratio of 1:1) to the skin on the back of each mouse every day. One day after the last testosterone injection, we euthanized all groups of C57BL/6 mice and isolated the dorsal skin for further analysis.

4.6. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining

The mouse skin tissue was fixed in 3.7 % formaldehyde solution at 4 °C for 3 days, and then cut and embedded in 4-μm-thick paraffin. The cut samples were deparaffinized with xylene and rehydrated with ethanol at different concentrations. Subsequently, they were stained with H&E solution. The stained tissue sections were mounted on clean slides and examined under a microscope to observe the result.

4.7. Quantitative Real-Time PCR

TRIzol reagent was used to extract RNA from mouse skin tissue in the alopecia model. To synthesize cDNA from total RNA, a cDNA synthesis kit from Thermo Fisher Scientific was utilized, following established protocols. Real-time PCR with SYBR premix Ex Taq was performed to measure the mRNA levels of Bcl-2, Bax, caspase 3, TGF-B1, DKK-1, HGF, and IGF-1. The expression levels were determined relative to GAPDH. The primer sequences are listed in Table 3.

4.8. Western Blotting

C57BL/6 mouse skin tissues were pulverized in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70 °C. To prepare for western blotting analysis, the tissues were lysed using the previously described lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 120 mM NaCl; 25 mM β-glycerol phosphate, pH 7.5; 20 mM NaF; 2% Nonidet P-40; and protease inhibitors). Following sonication, the lysates were pelleted by centrifugation at 12,000g for 3 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatants were used for western blotting analysis. Protein samples were subjected to 10–15% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, and the levels of AR, Bcl-2, caspase 9, cleaved caspase 9, and β-actin were measured using the corresponding antibodies.

4.9. 5α-Reductase Activity Assay

The entire liver of a 10-week-old male Sprague Dawley was extracted and lysed with lysis buffer containing protease inhibitors and additional components (7.5 mM K2HPO4, 3.25 mM KH2PO4, 1 mM DTT, 32 mM sucrose, and 0.2 mM PMSF) to obtain 5α-reductase. To initiate the reaction, reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH, 34 mM), testosterone (0.4 mM), and McIlvaine buffer (pH 5.0) were added to 4 μL of the enzyme extract that had been treated with different concentrations of Nk-EE. After incubation, the reaction was terminated by heating for 40 min at 37 °C. The oxidation of NADPH was detected by measuring the absorbance at 340 nm.

4.10. Statistical Analysis

The data presented in this paper represent the means ± standard errors of at least two independent experiments. Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests were performed to analyze the data. Statistical significance was defined as p-values < 0.05. SigmaPlot version 14.0 (Systat Software Inc., San Jose, CA, USA), and SPSS version 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) were used for data analysis.

5. Conclusions

AGA is a disease that causes hair loss, and its major cause is excessive response to androgenic hormones. Here, we conducted a 5α-reductase assay with Nk-EE. 5α-Reductase converted testosterone to its active form, DHT, and Nk-EE successfully downregulated enzymatic activity. The results showed that Nk-EE promoted hair growth in an AGA mouse model, and upregulated the proliferation of HFDPC cells. These effects were exerted through the anti-apoptotic effect of Nk-EE.

Our result suggests the possibility of a new alopecia drug using Nk-EE. Also, recently there have been a few papers reporting on plant extracts that use mass spectrometry data to show a protective effect against hair loss. In combination with these previous reports, we can make new research finding a common chemical which might be a main factor eliciting an anti-alopecia effect.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation showing the anti-androgenic and anti-apoptotic effects of Nk-EE.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation showing the anti-androgenic and anti-apoptotic effects of Nk-EE.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Dong Seon Kim, Won Young Jang, Jong-Hoon Kim, Jongsung Lee, and Jae Youl Cho; Data curation, Jong-Hoon Kim, Jongsung Lee, and Jae Youl Cho, Jongsung Lee and Jae Youl Cho; Formal analysis, Dong Seon Kim and Jae Youl Cho; Funding acquisition, Jae Youl Cho; Investigation, Dong Seon Kim, Won Young Jang, Sang Hee Park, Ji Hye Yoon, Chae Yun Shin, Lei Huang, Kry Masphal, Chhang Phourin, Hye-Woo Byun, Jino Son, Ga Ryun Kim; Project administration, Jae Youl Cho; Writing – original draft, Dong Seon Kim, Won Young Jang; Writing – review & editing, Jong-Hoon Kim, Jongsung Lee, and Jae Youl Cho.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Biological Resources (NIBR), funded by the Ministry of Environment (MOE) of the Republic of Korea (NIBR202207203).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Asfour, L.; Cranwell, W.; Sinclair, R. Male androgenetic alopecia. Endotext [Internet] 2023.

- Phillips, T.G.; Slomiany, W.P.; Robert Allison, I. Hair loss: common causes and treatment. American family physician 2017, 96, 371-378.

- Sadick, N.; Arruda, S. Understanding causes of hair loss in women. Dermatologic Clinics 2021, 39, 371-374. [CrossRef]

- Finner, A.M. Nutrition and hair: deficiencies and supplements. Dermatologic clinics 2013, 31, 167-172. [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.W.; Juhasz, M.; Mobasher, P.; Ekelem, C.; Mesinkovska, N.A. A Systematic Review of Topical Finasteride in the Treatment of Androgenetic Alopecia in Men and Women. J Drugs Dermatol 2018, 17, 457-463.

- Kanti, V.; Messenger, A.; Dobos, G.; Reygagne, P.; Finner, A.; Blumeyer, A.; Trakatelli, M.; Tosti, A.; del Marmol, V.; Piraccini, B.M. Evidence-based (S3) guideline for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in women and in men–short version. Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology 2018, 32, 11-22. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Jiang, T.-X.; Hughes, M.W.; Wu, P.; Widelitz, R.B.; Fan, G.; Chuong, C.-M. Progressive alopecia reveals decreasing stem cell activation probability during aging of mice with epidermal deletion of DNA methyltransferase 1. Journal of Investigative Dermatology 2012, 132, 2681-2690. [CrossRef]

- Mostaghimi, A.; Gao, W.; Ray, M.; Bartolome, L.; Wang, T.; Carley, C.; Done, N.; Swallow, E. Trends in Prevalence and Incidence of Alopecia Areata, Alopecia Totalis, and Alopecia Universalis Among Adults and Children in a US Employer-Sponsored Insured Population. JAMA Dermatol 2023, 159, 411-418. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.0002. [CrossRef]

- King, B.; Zhang, X.; Harcha, W.G.; Szepietowski, J.C.; Shapiro, J.; Lynde, C.; Mesinkovska, N.A.; Zwillich, S.H.; Napatalung, L.; Wajsbrot, D.; Fayyad, R.; Freyman, A.; Mitra, D.; Purohit, V.; Sinclair, R.; Wolk, R. Efficacy and safety of ritlecitinib in adults and adolescents with alopecia areata: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 2b-3 trial. Lancet 2023, 401, 1518-1529. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00222-2. [CrossRef]

- Wolff, H.; Fischer, T.W.; Blume-Peytavi, U. The Diagnosis and Treatment of Hair and Scalp Diseases. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2016, 113, 377-386. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2016.0377. [CrossRef]

- Nestor, M.S.; Ablon, G.; Gade, A.; Han, H.; Fischer, D.L. Treatment options for androgenetic alopecia: Efficacy, side effects, compliance, financial considerations, and ethics. J Cosmet Dermatol 2021, 20, 3759-3781. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocd.14537. [CrossRef]

- Jang, W.Y.; Kim, D.S.; Park, S.H.; Yoon, J.H.; Shin, C.Y.; Huang, L.; Nang, K.; Kry, M.; Byun, H.W.; Lee, B.H.; Lee, S.; Lee, J.; Cho, J.Y. Connarus semidecandrus Jack Exerts Anti-Alopecia Effects by Targeting 5alpha-Reductase Activity and an Intrinsic Apoptotic Pathway. Molecules 2022, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27134086. [CrossRef]

- Dell'Acqua, G.; Richards, A.; Thornton, M.J. The Potential Role of Nutraceuticals as an Adjuvant in Breast Cancer Patients to Prevent Hair Loss Induced by Endocrine Therapy. Nutrients 2020, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12113537. [CrossRef]

- Susanti, L.; Mustarichie, R.; Halimah, E.; Kurnia, D.; Setiawan, A.; Maladan, Y. Anti-Alopecia Activity of Alkaloids Group from Noni Fruit against Dihydrotestosterone-Induced Male Rabbits and Its Molecular Mechanism: In Vivo and In Silico Studies. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2022, 15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph15121557. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, B.M.; O'Donnell, L.; Smith, L.B.; Rebourcet, D. New Insights into Testosterone Biosynthesis: Novel Observations from HSD17B3 Deficient Mice. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms232415555. [CrossRef]

- Walker, W.H.; Cooke, P.S. Functions of Steroid Hormones in the Male Reproductive Tract as Revealed by Mouse Models. Int J Mol Sci 2023, 24. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms24032748. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.M.; Kannan, K. Determination of 19 Steroid Hormones in Human Serum and Urine Using Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Toxics 2022, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/toxics10110687. [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Khanal, S.; Bhavnani, N.; Mathias, A.; Lallo, J.; Kiriakou, A.; Ferrell, J.; Raman, P. Sex-specific differences in atherosclerosis, thrombospondin-1, and smooth muscle cell differentiation in metabolic syndrome versus non-metabolic syndrome mice. Front Cardiovasc Med 2022, 9, 1020006. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.1020006. [CrossRef]

- Joseph, M.A.; Jayaseelan, E.; Ganapathi, B.; Stephen, J. Hidradenitis suppurativa treated with finasteride. J Dermatolog Treat 2005, 16, 75-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546630510031403. [CrossRef]

- Andersson, S. Steroidogenic enzymes in skin. Eur J Dermatol 2001, 11, 293-295.

- Steele, V.E.; Arnold, J.T.; Lei, H.; Izmirlian, G.; Blackman, M.R. Comparative effects of DHEA and DHT on gene expression in human LNCaP prostate cancer cells. Anticancer Res 2006, 26, 3205-3215.

- Joshua Cohen, D.; ElBaradie, K.; Boyan, B.D.; Schwartz, Z. Sex-specific effects of 17beta-estradiol and dihydrotestosterone (DHT) on growth plate chondrocytes are dependent on both ERalpha and ERbeta and require palmitoylation to translocate the receptors to the plasma membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 2021, 1866, 159028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbalip.2021.159028. [CrossRef]

- Asfour, L.; Cranwell, W.; Sinclair, R.: Male Androgenetic Alopecia. In: Endotext. edn. Edited by Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Blackman MR, Boyce A, Chrousos G, Corpas E, de Herder WW, Dhatariya K, Dungan K, Hofland J et al. South Dartmouth (MA); 2000.

- Trueb, R.M. Molecular mechanisms of androgenetic alopecia. Exp Gerontol 2002, 37, 981-990. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0531-5565(02)00093-1. [CrossRef]

- Naito, A.; Sato, T.; Matsumoto, T.; Takeyama, K.; Yoshino, T.; Kato, S.; Ohdera, M. Dihydrotestosterone inhibits murine hair growth via the androgen receptor. Br J Dermatol 2008, 159, 300-305. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.08671.x. [CrossRef]

- Bachelot, A.; Chabbert-Buffet, N.; Salenave, S.; Kerlan, V.; Galand-Portier, M.B. Anti-androgen treatments. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2010, 71, 19-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ando.2009.12.001. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Harada, N.; Okajima, K. Dihydrotestosterone inhibits hair growth in mice by inhibiting insulin-like growth factor-I production in dermal papillae. Growth Horm IGF Res 2011, 21, 260-267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ghir.2011.07.003. [CrossRef]

- Yazdabadi, A.; Sinclair, R. Treatment of female pattern hair loss with the androgen receptor antagonist flutamide. Australas J Dermatol 2011, 52, 132-134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-0960.2010.00735.x. [CrossRef]

- York, K.; Meah, N.; Bhoyrul, B.; Sinclair, R. A review of the treatment of male pattern hair loss. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2020, 21, 603-612. https://doi.org/10.1080/14656566.2020.1721463. [CrossRef]

- Brufsky, A.; Fontaine-Rothe, P.; Berlane, K.; Rieker, P.; Jiroutek, M.; Kaplan, I.; Kaufman, D.; Kantoff, P. Finasteride and flutamide as potency-sparing androgen-ablative therapy for advanced adenocarcinoma of the prostate. Urology 1997, 49, 913-920. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00091-5. [CrossRef]

- Diviccaro, S.; Melcangi, R.C.; Giatti, S. Post-finasteride syndrome: An emerging clinical problem. Neurobiol Stress 2020, 12, 100209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2019.100209. [CrossRef]

- Brokken, L.J.; Adamsson, A.; Paranko, J.; Toppari, J. Antiandrogen exposure in utero disrupts expression of desert hedgehog and insulin-like factor 3 in the developing fetal rat testis. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 445-451. https://doi.org/10.1210/en.2008-0230. [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Zhu, L.; He, J. Morphogenesis, Growth Cycle and Molecular Regulation of Hair Follicles. Front Cell Dev Biol 2022, 10, 899095. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.899095. [CrossRef]

- Oh, J.W.; Kloepper, J.; Langan, E.A.; Kim, Y.; Yeo, J.; Kim, M.J.; Hsi, T.C.; Rose, C.; Yoon, G.S.; Lee, S.J.; Seykora, J.; Kim, J.C.; Sung, Y.K.; Kim, M.; Paus, R.; Plikus, M.V. A Guide to Studying Human Hair Follicle Cycling In Vivo. J Invest Dermatol 2016, 136, 34-44. https://doi.org/10.1038/JID.2015.354. [CrossRef]

- Al-Nuaimi, Y.; Goodfellow, M.; Paus, R.; Baier, G. A prototypic mathematical model of the human hair cycle. J Theor Biol 2012, 310, 143-159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtbi.2012.05.027. [CrossRef]

- Van Neste, D.; Leroy, T.; Conil, S. Exogen hair characterization in human scalp. Skin Res Technol 2007, 13, 436-443. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0846.2007.00248.x. [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.H.; Kim, K.; Lee, H.; Yang, W.M. Human placenta induces hair regrowth in chemotherapy-induced alopecia via inhibition of apoptotic factors and proliferation of hair follicles. BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies 2020, 20, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Peus, D.; Pittelkow, M.R. Growth factors in hair organ development and the hair growth cycle. Dermatologic clinics 1996, 14, 559-572. [CrossRef]

- Chu, S.-Y.; Chou, C.-H.; Huang, H.-D.; Yen, M.-H.; Hong, H.-C.; Chao, P.-H.; Wang, Y.-H.; Chen, P.-Y.; Nian, S.-X.; Chen, Y.-R. Mechanical stretch induces hair regeneration through the alternative activation of macrophages. Nature communications 2019, 10, 1524. [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; White, E. p53-dependent apoptosis pathways. 2001.

- Truong, V.L.; Bak, M.J.; Lee, C.; Jun, M.; Jeong, W.S. Hair Regenerative Mechanisms of Red Ginseng Oil and Its Major Components in the Testosterone-Induced Delay of Anagen Entry in C57BL/6 Mice. Molecules 2017, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules22091505. [CrossRef]

- Ceruti, J.M.; Leiros, G.J.; Balana, M.E. Androgens and androgen receptor action in skin and hair follicles. Mol Cell Endocrinol 2018, 465, 122-133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2017.09.009. [CrossRef]

- Noh, D.; Choi, J.G.; Huh, E.; Oh, M.S. Tectorigenin, a Flavonoid-Based Compound of Leopard Lily Rhizome, Attenuates UV-B-Induced Apoptosis and Collagen Degradation by Inhibiting Oxidative Stress in Human Keratinocytes. Nutrients 2018, 10. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10121998. [CrossRef]

- Ling, L.; Feng, X.; Wei, T.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Tang, D.; Luo, Y.; Xiong, Z. Human amnion-derived mesenchymal stem cell (hAD-MSC) transplantation improves ovarian function in rats with premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) at least partly through a paracrine mechanism. Stem Cell Res Ther 2019, 10, 46. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13287-019-1136-x. [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z.; Sezin, T.; Chang, Y.; Lee, E.Y.; Wang, E.H.C.; Christiano, A.M. Induction of T cell exhaustion by JAK1/3 inhibition in the treatment of alopecia areata. Front Immunol 2022, 13, 955038. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.955038. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).