Submitted:

09 August 2023

Posted:

10 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ink Preparation and 3D Printing

2.2. Sintering and Sulfur Diffusion Postprocessing

2.3. Characterization of Crystal Structure and Sulfur Content

2.4. Thermoelectric Characterization

3. Results and Discussion

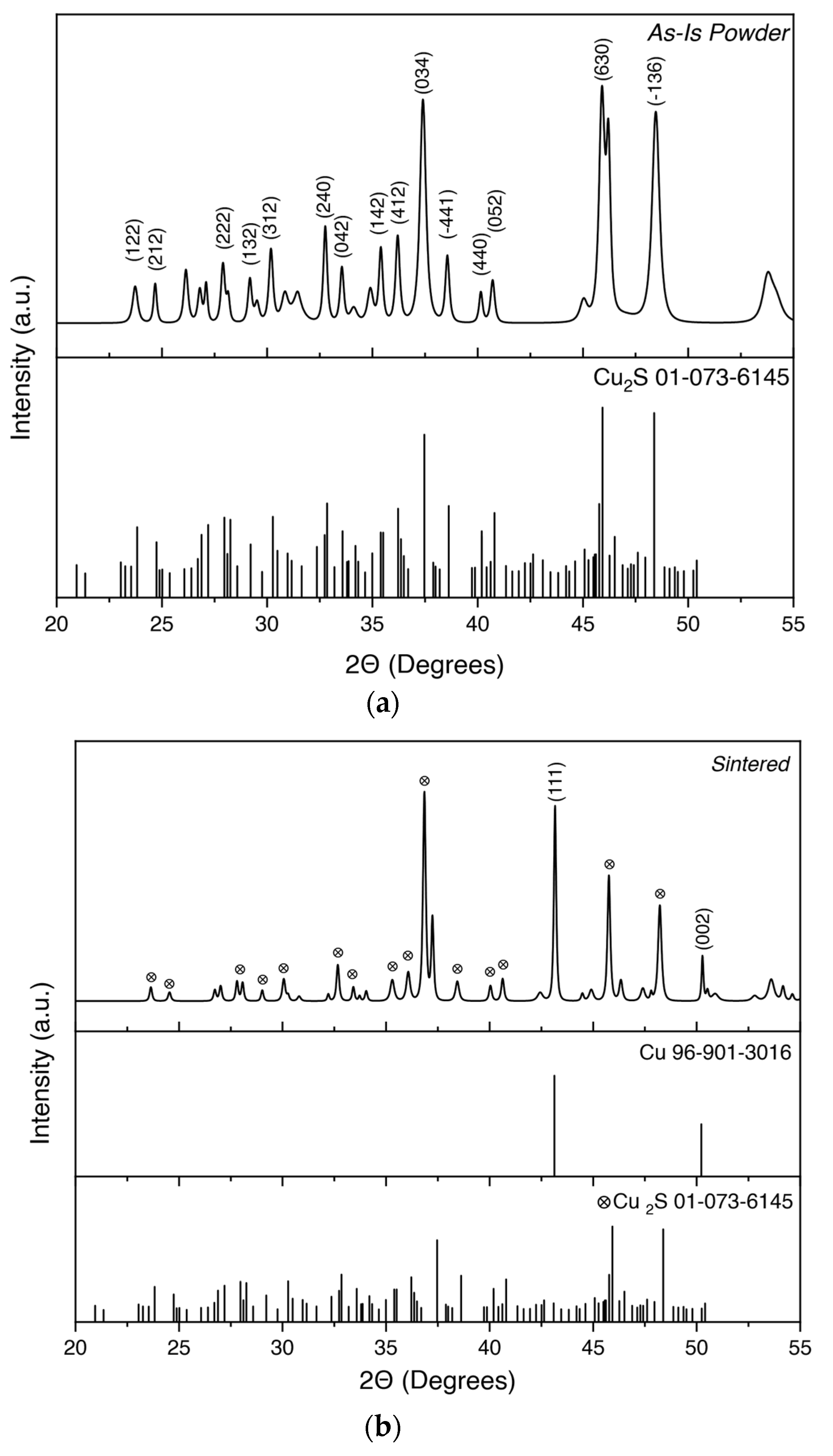

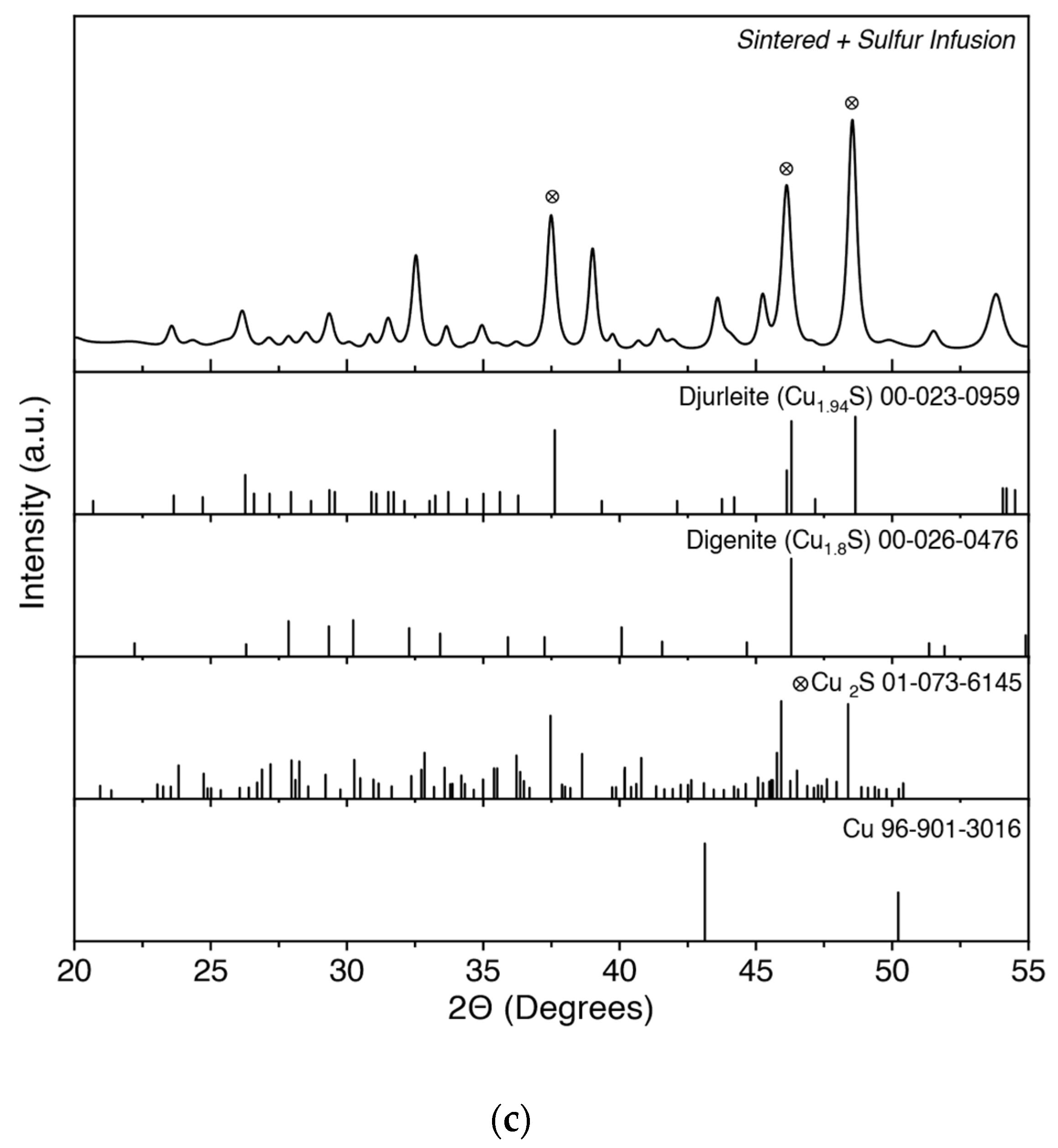

3.1. Structural and Morphological Analysis

3.2. Compositional Analysis

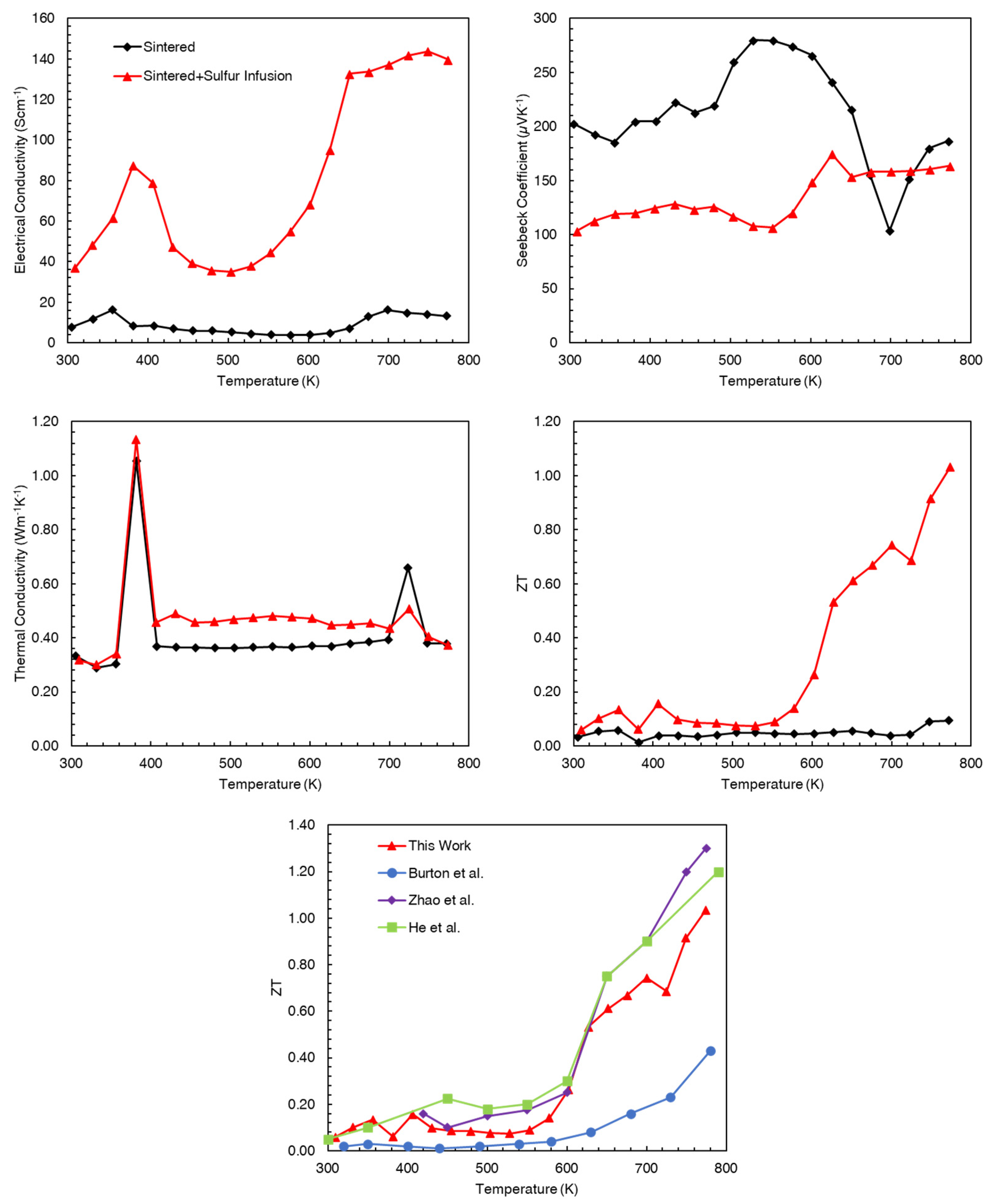

3.3. Thermoelectric Characterization

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Twaha, S., et al., A comprehensive review of thermoelectric technology: Materials, applications, modelling and performance improvement. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 2016. 65: p. 698-726. [CrossRef]

- Pourkiaei, S.M., et al., Thermoelectric cooler and thermoelectric generator devices: A review of present and potential applications, modeling and materials. Energy, 2019. 186. [CrossRef]

- Goldsmid, H.J., Bismuth Telluride and Its Alloys as Materials for Thermoelectric Generation. Materials, 2014. 7(4): p. 2577-2592. [CrossRef]

- Poudel, B., et al., High-thermoelectric performance of nanostructured bismuth antimony telluride bulk alloys. Science, 2008. 320(5876): p. 634-638. [CrossRef]

- Witting, I.T., et al., The Thermoelectric Properties of Bismuth Telluride. Advanced Electronic Materials, 2019. 5(6). [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, O., S. Tomiyoshi, and K. Makita, Bismuth telluride compounds with high thermoelectric figures of merit. Journal of Applied Physics, 2003. 93(1): p. 368-374. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H., et al., Laser additive manufacturing of powdered bismuth telluride. Journal of Materials Research, 2018. 33(23): p. 4031-4039. [CrossRef]

- Dughaish, Z.H., Lead telluride as a thermoelectric material for thermoelectric power generation. Physica B-Condensed Matter, 2002. 322(1-2): p. 205-223. [CrossRef]

- LaLonde, A.D., et al., Lead telluride alloy thermoelectrics. Materials Today, 2011. 14(11): p. 526-532. [CrossRef]

- Pei, Y.Z., et al., Combination of large nanostructures and complex band structure for high performance thermoelectric lead telluride. Energy & Environmental Science, 2011. 4(9): p. 3640-3645. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H., et al., Copper ion liquid-like thermoelectrics. Nat Mater, 2012. 11(5): p. 422-5. [CrossRef]

- Mulla, R. and M.H.K. Rabinal, Copper Sulfides: Earth-Abundant and Low-Cost Thermoelectric Materials. Energy Technology, 2019. 7(7). [CrossRef]

- Oztan, C.Y., et al., Thermoelectric performance of Cu2Se doped with rapidly synthesized gel-like carbon dots. Journal of Alloys and Compounds, 2021. 864. [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.D., et al., Enhanced stability and thermoelectric figure-of-merit in copper selenide by lithium doping. Materials Today Physics, 2017. 1: p. 7-13. [CrossRef]

- Shi, D.-l., et al., Thermal stability study of Cu1.97Se superionic thermoelectric materials. Journal of Materials Chemistry C, 2020. 8(30): p. 10221-10228. [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.D., et al., Promising and Eco-Friendly Cu2 X-Based Thermoelectric Materials: Progress and Applications. Adv Mater, 2020. 32(8): p. e1905703. [CrossRef]

- Okamoto, K. and S. Kawai, Electrical Conduction and Phase Transition of Copper Sulfides. Japanese Journal of Applied Physics, 1973. 12. [CrossRef]

- Nieroda, P., et al., Thermoelectric properties of Cu2S obtained by high temperature synthesis and sintered by IHP method. Ceramics International, 2020. 46(16): p. 25460-25466. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L., et al., High thermoelectric and mechanical performance in highly dense Cu2−xS bulks prepared by a melt-solidification technique. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 2015. 3(18): p. 9432-9437. [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, D.J. and D.E. Laughlin, The Cu-S (Copper-Sulfur) system. Bulletin of Alloy Phase Diagrams, 1983. 4(3): p. 254-271. [CrossRef]

- He, Y., et al., High thermoelectric performance in non-toxic earth-abundant copper sulfide. Adv Mater, 2014. 26(23): p. 3974-8. [CrossRef]

- Dennler, G., et al., Are Binary Copper Sulfides/Selenides Really New and Promising Thermoelectric Materials? Advanced Energy Materials, 2014. 4(9). [CrossRef]

- Wei, T.-R., et al., Copper chalcogenide thermoelectric materials. Science China Materials, 2018. 62(1): p. 8-24. [CrossRef]

- Li, M., et al., Effect of the Annealing Atmosphere on Crystal Phase and Thermoelectric Properties of Copper Sulfide. ACS Nano, 2021. 15(3): p. 4967-4978. [CrossRef]

- Qiu, P., et al., Suppression of atom motion and metal deposition in mixed ionic electronic conductors. Nat Commun, 2018. 9(1): p. 2910. [CrossRef]

- Oztan, C., et al., Additive manufacturing of thermoelectric materials via fused filament fabrication. Applied Materials Today, 2019. 15: p. 77-82. [CrossRef]

- Burton, M., et al., Printed Thermoelectrics. Adv Mater, 2022. 34(18): p. e2108183. [CrossRef]

- Kim, F., et al., Direct ink writing of three-dimensional thermoelectric microarchitectures. Nature Electronics, 2021. 4(8): p. 579-587. [CrossRef]

- Jo, S., et al., Ink Processing for Thermoelectric Materials and Power-Generating Devices. Advanced Materials, 2019. 31(20). [CrossRef]

- Kato, K., H. Hagino, and K. Miyazaki, Fabrication of Bismuth Telluride Thermoelectric Films Containing Conductive Polymers Using a Printing Method. Journal of Electronic Materials, 2013. 42(7): p. 1313-1318. [CrossRef]

- Amin, A., et al., Screen-printed bismuth telluride nanostructured composites for flexible thermoelectric applications. Journal of Physics-Energy, 2022. 4(2). [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.L., et al., Flexible thermoelectric generators with inkjet-printed bismuth telluride nanowires and liquid metal contacts. Nanoscale, 2019. 11(12): p. 5222-5230. [CrossRef]

- Kim, F., et al., 3D printing of shape-conformable thermoelectric materials using all-inorganic Bi2Te3-based inks. Nature Energy, 2018. 3(4): p. 301-309. [CrossRef]

- Burton, M.R., et al., Earth abundant, non-toxic, 3D printed Cu2−xS with high thermoelectric figure of merit. Journal of Materials Chemistry A, 2019. 7(44): p. 25586-25592. [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y., et al., High-Temperature Mechanical and Thermoelectric Properties of p-Type Bi0.5Sb1.5Te3 Commercial Zone Melting Ingots. Journal of Electronic Materials, 2013. 43(6): p. 2017-2022. [CrossRef]

- Ramdohr, P., The Ore Minerals and Their Intergrowths. 2013: Elsevier Science. [CrossRef]

- Cook, W.R., Phase changes in Cu2S as a function of temperature. 1972: National Bureau of Standards.

- Sorokin, G.P. and A.P. Paradenko, Electrical Properties of Cu2S. Soviet Physics Journal, 1966. [CrossRef]

- Snyder, G.J. and E.S. Toberer, Complex thermoelectric materials. Nat Mater, 2008. 7(2): p. 105-14. [CrossRef]

- Nieroda, P., et al., Extremely Fast and Cheap Densification of Cu2S by Induction Melting Method. Materials, 2021. 14(23). [CrossRef]

- Roseboom, E.H. and JR., An investigation of the system Cu-S and some natural copper sulfides between 25 and 700 C. Economic Geology, 1966. 61.

- Posfai, M. and P.R. Buseck, Djurleite, digenite, and chalcocite: Intergrowths and transformations. American Mineralogist, 1994. 79(3-4): p. 308-315.

| Sample ID | Density (g/cm3) | STD | Relative Density |

|---|---|---|---|

| Printed Part | 2.79 | 0.07 | 49.9 |

| Sintered | 2.84 | 0.05 | 50.8 |

| Post-Processed | 2.68 | 0.13 | 47.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).