Submitted:

08 August 2023

Posted:

10 August 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study design and sample

2.2. Sample size and randomization

2.3. Surgical and prosthetic treatment

2.4. Patients analysis

- -

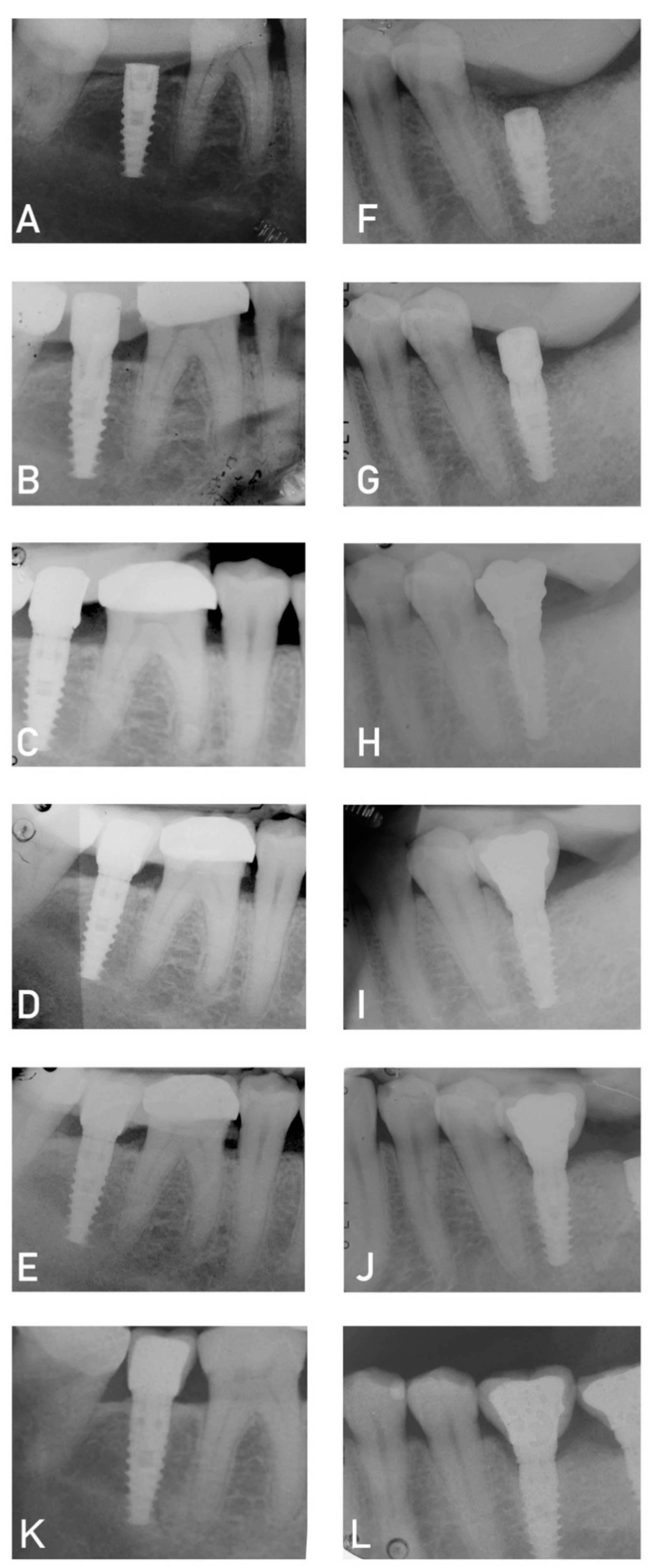

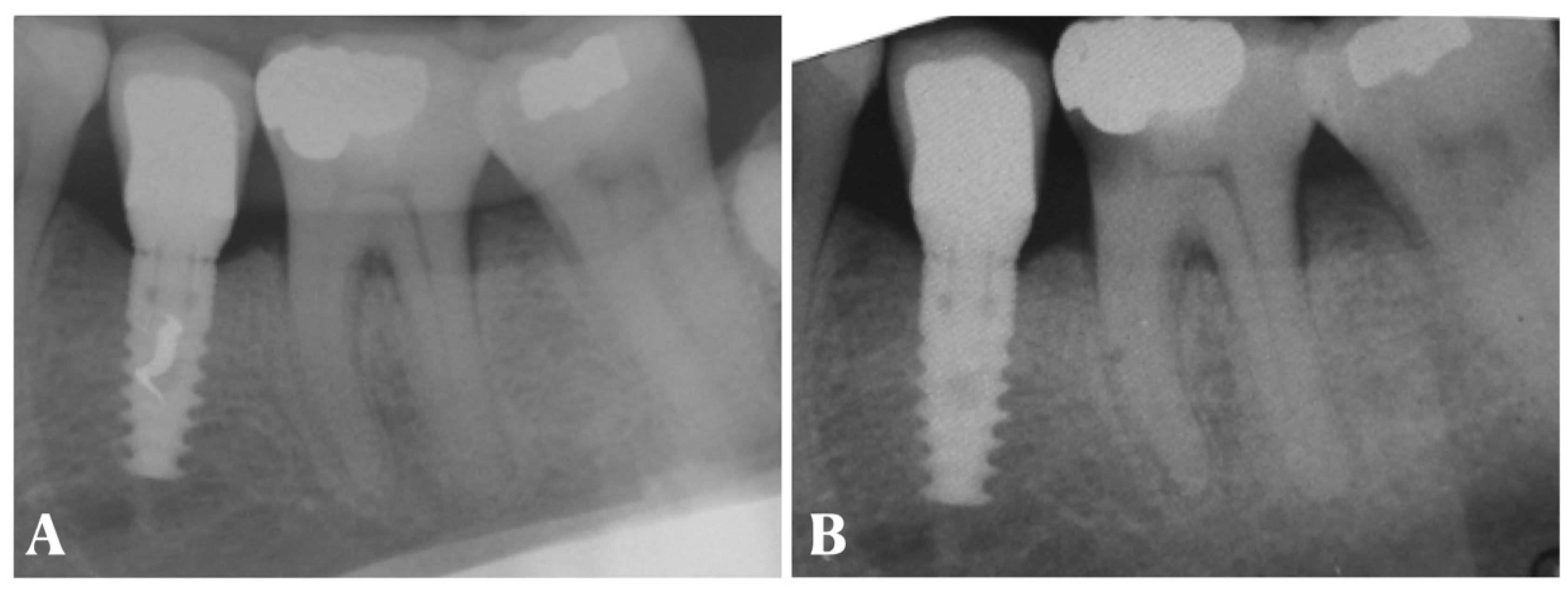

- Periapical X-ray

- -

- FMPS and FMBS

- -

- Frequency of annual follow-up visit

2.5. Statistical analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Simonis, P.; Dufour, T.; Tenenbaum, H. Long-term implant survival and success: a 10-16-year follow-up of non-submerged dental implants. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2010, 21, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Filius, M.A.P.; Vissink, A.; Cune, M.S.; Raghoebar, G.M.; Visser, A. Long-term implant performance and patients' satisfaction in oligodontia. J. Dent. 2018, 71, 18–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumer, A.; Toekan, S.; Saure, D.; Korner, G. Survival and success of implants in a private periodontal practice: a 10-year retrospective study. BMC Oral Health 2020, 20, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chrcanovic, B.R.; Martins, M.D.; Wennerberg, A. Immediate placement of implants into infected sites: a systematic review. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2015, 17 (Suppl 1), e1–e16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lang, N.P.; Berglundh, T.; Working Group 4 of Seventh European Workshop on Periodontology. Periimplant diseases: where are we now? Consensus of the Seventh European Workshop on Periodontology. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2011, 38, 178–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berardini, M.; Trisi, P.; Sinjari, B.; Rutjes, A.W.; Caputi, S. The Effects of High Insertion Torque Versus Low Insertion Torque on Marginal Bone Resorption and Implant Failure Rates: A Systematic Review With Meta-Analyses. Implant Dent. 2016, 25, 532–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, R.E.; Zembic, A.; Pjetursson, B.E.; Zwahlen, M.; Thoma, D.S. Systematic review of the survival rate and the incidence of biological, technical, and esthetic complications of single crowns on implants reported in longitudinal studies with a mean follow-up of 5 years. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2012, 23 (Suppl 6), 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caricasulo, R.; Malchiodi, L.; Ghensi, P.; Fantozzi, G.; Cucchi, A. The influence of implant-abutment connection to peri-implant bone loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2018, 20, 653–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krisam, J.; Ott, L.; Schmitz, S.; et al. Factors affecting the early failure of implants placed in a dental practice with a specialization in implantology - a retrospective study. BMC Oral Health 2019, 19, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coli, P.; Christiaens, V.; Sennerby, L.; Bruyn, H. Reliability of periodontal diagnostic tools for monitoring peri-implant health and disease. Periodontol. 2000 2017, 73, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrektsson, T.; Zarb, G.A.; Worthington, P.; Eriksson, A.R. The long-term efficacy of currently used dental implants: a review and proposed criteria of success. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 1986, 1, 11–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lombardi, T.; Berton, F.; Salgarello, S.; Barbalonga, E.; Rapani, A.; Piovesana, F.; Gregorio, C.; Barbati, G.; Di Lenarda, R.; Stacchi, C. Factors Influencing Early Marginal Bone Loss around Dental Implants Positioned Subcrestally: A Multicenter Prospective Clinical Study. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Castro, D.S.; Araujo, M.A.; Benfatti, C.A.; Araujo, C.R.; Piattelli, A.; Perrotti, V.; Iezzi, G. Comparative histological and histomorphometrical evaluation of marginal bone resorption around external hexagon and Morse cone implants: an experimental study in dogs. Implant Dent. 2014, 23, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivara, F.; Macaluso, G.M.; Toffoli, A.; Calciolari, E.; Goldoni, M.; Lumetti, S. The effect of a 2-mm inter-implant distance on esthetic outcomes in immediately non-occlusally loaded platform shifted implants in healed ridges: 12-month results of a randomized clinical trial. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2020, 22, 486–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dellow, A.G.; Driessen, C.H.; Nel, H.J. Scanning electron microscopy evaluation of the interfacial fit of interchanged components of four dental implant systems. Int. J. Prosthodont. 1997, 10, 216–221. [Google Scholar]

- D'Ercole, S.; Tripodi, D.; Ravera, L.; Perrotti, V.; Piattelli, A.; Iezzi, G. Bacterial leakage in Morse Cone internal connection implants using different torque values: an in vitro study. Implant Dent. 2014, 23, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarano, A.; Perrotti, V.; Piattelli, A.; Iaculli, F.; Iezzi, G. Sealing capability of implant-abutment junction under cyclic loading: a toluidine blue in vitro study. J. Appl. Biomater. Funct. Mater. 2015, 13, e293–e295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ericsson, I.; Persson, L.G.; Berglundh, T.; Marinello, C.P.; Lindhe, J.; Klinge, B. Different types of inflammatory reactions in peri-implant soft tissues. J. Clin. Periodontol. 1995, 22, 255–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faveri, M.; Gursky, L.C.; Feres, M.; Shibli, J.A.; Salvador, S.L.; de Figueiredo, L.C. Scaling and root planing and chlorhexidine mouthrinses in the treatment of chronic periodontitis: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2006, 33, 819–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carcuac, O.; Abrahamsson, I.; Charalampakis, G.; Berglundh, T. The effect of the local use of chlorhexidine in surgical treatment of experimental peri-implantitis in dogs. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2015, 42, 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Waal, Y.C.M.; Raghoebar, G.M.; Meijer, H.J.A.; Winkel, E.G.; van Winkelhoff, A.J. Implant decontamination with 2% chlorhexidine during surgical peri-implantitis treatment: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2015, 26, 1015–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carcuac, O.; Derks, J.; Charalampakis, G.; Abrahamsson, I.; Wennstr√∂m, J.; Berglundh, T. Adjunctive Systemic and Local Antimicrobial Therapy in the Surgical Treatment of Peri-implantitis: A Randomized Controlled Clinical Trial. J. Dent. Res. 2016, 95, 50–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinjari, B.; D'Addazio, G.; De Tullio, I.; Traini, T.; Caputi, S. Peri-Implant Bone Resorption during Healing Abutment Placement: The Effect of a 0.20% Chlorhexidine Gel vs. Placebo-A Randomized Double Blind Controlled Human Study. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 5326340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- D'Ercole, S.; D'Addazio, G.; Di Lodovico, S.; Traini, T.; Di Giulio, M.; Sinjari, B. Porphyromonas Gingivalis Load is Balanced by 0.20% Chlorhexidine Gel. A Randomized, Double-Blind, Controlled, Microbiological and Immunohistochemical Human Study. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Annibali, S.; Bignozzi, I.; Cristalli, M.P.; Graziani, F.; La Monaca, G.; Polimeni, A. Peri-implant marginal bone level: a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing platform switching versus conventionally restored implants. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2012, 39, 1097–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papaspyridakos, P.; Chen, C.J.; Singh, M.; Weber, H.P.; Gallucci, G.O. Success criteria in implant dentistry: a systematic review. J. Dent. Res. 2012, 91, 242–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laurell, L.; Lundgren, D. Marginal bone level changes at dental implants after 5 years in function: a meta-analysis. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2011, 13, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derks, J.; HaÃäkansson, J.; WennstroÃàm, J.L.; Tomasi, C.; Larsson, M.; Berglundh, T. Effectiveness of implant therapy analyzed in a Swedish population: early and late implant loss. J. Dent. Res. 2015, 94, 44S–51S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doornewaard, R.; Christiaens, V.; De Bruyn, H.; et al. Long-term effect of surface roughness and patients' factors on crestal bone loss at dental implants. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2017, 19, 372–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zumstein, T.; SchuÃàtz, S.; Sahlin, H.; Sennerby, L. Factors influencing marginal bone loss at a hydrophilic implant design placed with or without GBR procedures: A 5-year retrospective study. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2019, 21, 817–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Lin, Z.; Song, Z.; Shu, R.; Xie, Y. Survival rate and potential risk indicators of implant loss in non-smokers and systemically healthy periodontitis patients: An up to 9-year retrospective study. J. Periodont Res. 2021, 56, 547–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, W.M.; Geng, W.; Luo, C.C. Prosthetic complications of fixed dental prostheses supported by locking-taper implants: a retrospective study with a mean follow-up of 5 years. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gosau, D.M.; Hahnel, S.; Schwarz, F.; Gerlach, T.; Reichert, T.E.; BuÃàrgers, R. Effect of six different peri-implantitis disinfection methods on in vivo human oral biofilm. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2010, 21, 866–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chin, M.Y.; Sandham, A.; de Vries, J.; van der Mei, H.C.; Busscher, H.J. Biofilm formation on surface characterized micro-implants for skeletal anchorage in orthodontics. Biomaterials 2007, 28, 2032–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ntrouka, V.I.; Slot, D.E.; Louropoulou, A.; Van der Weijden, F. The effect of chemotherapeutic agents on contaminated titanium surfaces: a systematic review. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2011, 22, 681–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinjari, B.; D'Addazio, G.; Bozzi, M.; Celletti, R.; Traini, T.; Mavriqi, L.; Caputi, S. Comparison of a Novel Ultrasonic Scaler Tip vs. Conventional Design on a Titanium Surface. Materials 2018, 11, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anitua, E.; Orive, G.; Aguirre, J.J.; Ardanza, B.; Andia, I. 5-year clinical experience with BTI dental implants: risk factors for implant failure. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2008, 35, 724–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitz-Mayfield, L.J.; Huynh-Ba, G. History of treated periodontitis and smoking as risks for implant therapy. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2009, 24 (Suppl), 39–68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mayta-Tovalino, F.; Mendoza-Martiarena, Y.; Romero-Tapia, P.; et al. An 11-Year Retrospective Research Study of the Predictive Factors of Peri-Implantitis and Implant Failure: Analytic-Multicentric Study of 1279 Implants in Peru. Int. J. Dent. 2019, 2019, 3527872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renvert, S.; Quirynen, M. Risk indicators for peri-implantitis. A narrative review. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2015, 26, 15–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Addazio, G.; Santilli, M.; Sinjari, B.; Xhajanka, E.; Rexhepi, I.; Mangifesta, R.; Caputi, S. Access to Dental Care-A Survey from Dentists, People with Disabilities and Caregivers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguirre-Zorzano, L.A.; Estefania-Fresco, R.; Telletxea, O.; Bravo, M. Prevalence of peri-implant inflammatory disease in patients with a history of periodontal disease who receive supportive periodontal therapy. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2015, 26, 1338–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garcia-Bellosta, S.; Bravo, M.; Subira, C.; Echeverria, J.J. Retrospective study of the long-term survival of 980 implants placed in a periodontal practice. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 2010, 25, 613–619. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goh, M.S.; Hong, E.J.; Chang, M. Prevalence and risk indicators of peri-implantitis in Korean patients with a history of periodontal disease: a cross-sectional study. J. Periodontal Implant Sci. 2017, 47, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seki, K.; HaÃäkansson, J. Implant Treatment with 12-Year Follow-Up in a Patient with Severe Chronic Periodontitis: A Case Report and Literature Review. Case Rep. Dent. 2019, 2019, 3715159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.Y.; Shin, K.S.; Jung, J.H.; Cho, H.W.; Kwon, K.H.; Kim, Y.L. Clinical study on screw loosening in dental implant prostheses: a 6-year retrospective study. J. Korean Assoc. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 46, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jemt, T.; Laney, W.R.; Harris, D.; Henry, P.J.; Krogh, P.H., Jr.; Polizzi, G.; Zarb, G.A.; Herrmann, I. Osseointegrated implants for single tooth replacement: a 1-year report from a multicenter prospective study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implants 1991, 6, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kreissl, M.E.; Gerds, T.; Muche, R.; Heydecke, G.; Strub, J.R. Technical complications of implant-supported fixed partial dentures in partially edentulous cases after an average observation period of 5 years. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2007, 18, 720–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cho, S.C.; Small, P.N.; Elian, N.; Tarnow, D. Screw loosening for standard and wide diameter implants in partially edentulous cases: 3- to 7-year longitudinal data. Implant Dent. 2004, 13, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Crescenzo, A.; Bardini, L.; Sinjari, B.; Traini, T.; Marinelli, L.; Carraro, M.; Germani, R.; Di Profio, P.; Caputi, S.; Di Stefano, A.; Bonchio, M.; Paolucci, F.; Fontana, A. Surfactant hydrogels for the dispersion of carbon-nanotube-based catalysts. Chemistry 2013, 19, 16415–16423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Cremer, K.; Braem, A.; Gerits, E.; De Brucker, K.; Vandamme, K.; Martens, J.A.; Michiels, J.; Vleugels, J.; Cammue, B.P.; Thevissen, K. Controlled Release of Chlorhexidine from a Mesoporous Silica-Containing Macroporous Titanium Dental Implant Prevents Microbial Biofilm Formation. Eur. Cells Mater. 2017, 33, 13–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

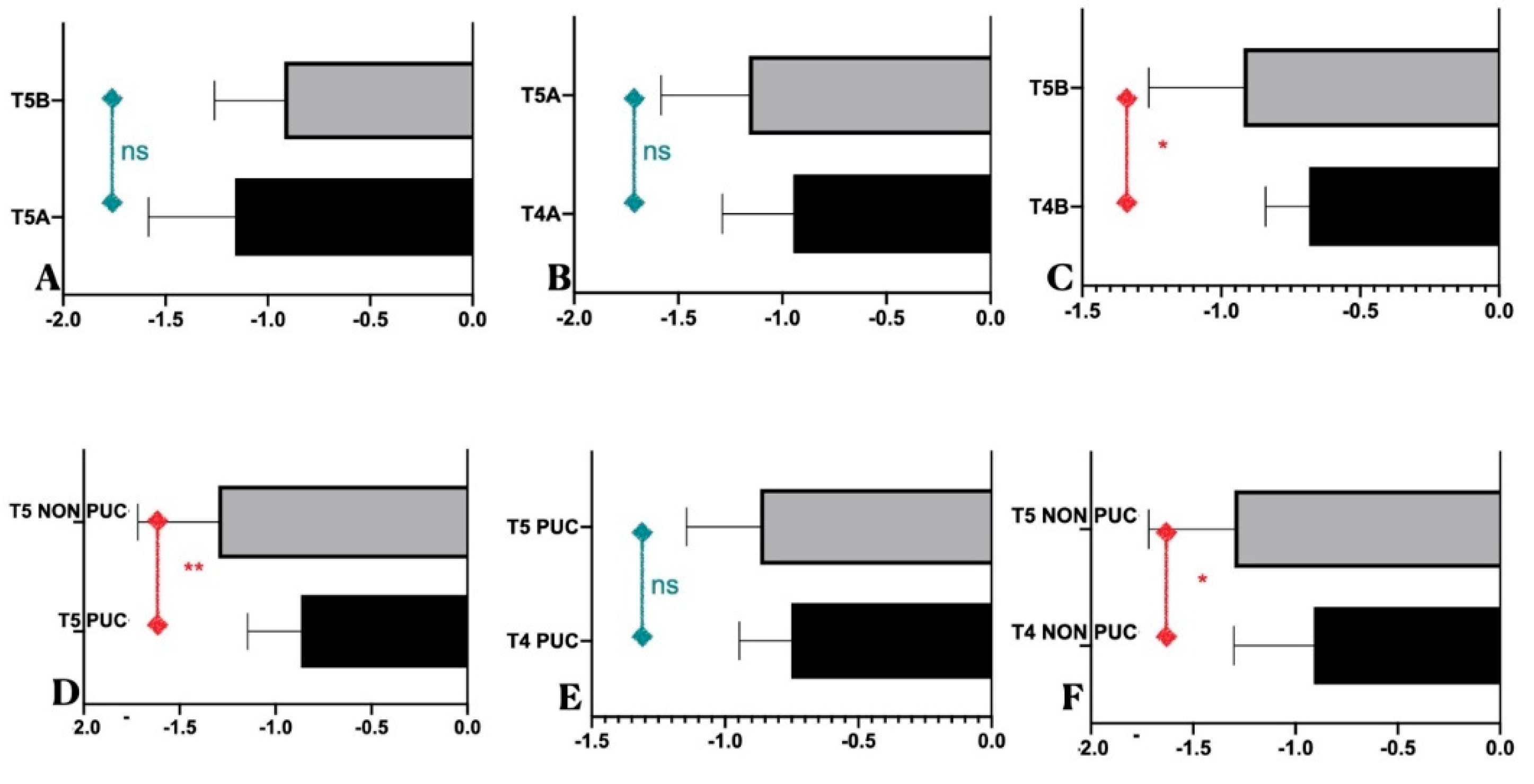

| Total patients numbers | 32 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients evaluated at 5-year follow-up | 31 | |||

| Patients Group A | 16 | |||

| Patients Group B | 15 | |||

| Implant failed | 1 (Group A). implant removed | |||

| Survival rate | 96.7% | |||

| Patients under strict hygienic control (PUC) | 58.1% | |||

| Global Full mouth Plaque Score (FMPS) | 21,38% ± 5,65 | |||

| Global Full mouth Bleeding Score (FMBS) | 20,96% ± 4,76 | |||

| Group A | Group B | Sig. | ||

| FMPS (Group A- Group B) | 22,59% ± 5,93 | 19,83% ± 5,22 | P=0,18 ns | |

| FMBS (Group A- Group B) | 21,37% ± 5,46 | 20,39% ± 4,23 | P=0,59 ns | |

| FMPS (PUC / NO-PUC) | 17,81% ± 3,37 | 26,32% ± 4,42 | **** | |

| FMBS (PUC / NO-PUC) | 18,17% ± 2,88 | 24,95% ± 4,3 | *** | |

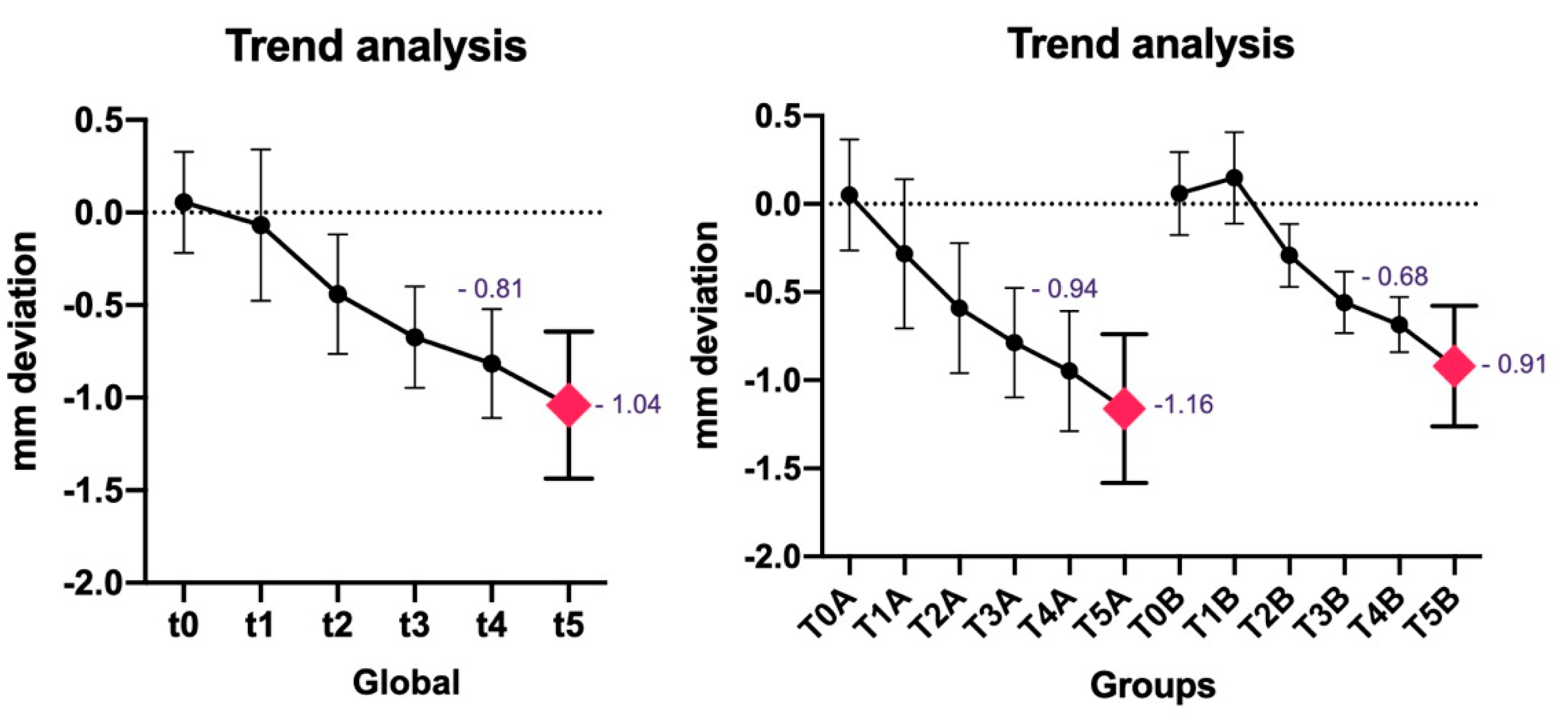

| ID PAT | SITE | GROUP | PUC/ NO-PUC | T0 | T1 | T2 | T3 | T4 | T5 | FMPS | FMBS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 1.6 | A | NO-PUC | 0,22 | -0,06 | -0,49 | -0,73 | -1,51 | -1,6 | 22,4 | 24,5 | |

| 5 | 1.4 | A | PUC | 0 | -0,38 | -0,55 | -0,82 | -1,07 | -1,1 | 21,3 | 19,45 | |

| 7 | 4.6 | A | PUC | 0,49 | 0,12 | -0,2 | -0,84 | -0,95 | -1,2 | 24,5 | 17,54 | |

| 11 | 1.6 | A | NO-PUC | -0,62 | -1,53 | -1,75 | -1,76 | -1,84 | -2,2 | 25,6 | 18,34 | |

| 14 | 4.7 | A | PUC | -0,39 | -0,92 | -0,89 | -0,65 | -0,8 | -0,87 | 19,3 | 18,5 | |

| 17 | 3.6 | A | NO-PUC | -0,06 | -0,38 | -0,43 | -0,68 | -0,73 | -0,88 | 29,4 | 28,76 | |

| 20 | 3.6 | A | PUC | 0,06 | 0 | -0,44 | -0,6 | -0,63 | -0,7 | 16,6 | 19,5 | |

| 21 | 4.6 | A | PUC | 0,16 | -0,29 | -0,53 | -0,73 | -0,94 | -0,9 | 14,3 | 14,5 | |

| 23 | 4.6 | A | NO-PUC | -0,13 | -0,2 | -0,74 | -1,01 | -1,05 | -1,68 | 31,4 | 29,04 | |

| 24 | 3.5 | A | NO-PUC | -0,06 | -0,2 | -0,44 | -0,59 | -0,64 | -1,5 | 30,7 | 31,84 | |

| 25 | 2.2 | A | PUC | 0,6 | -0,06 | -0,46 | -0,71 | -0,77 | -0,82 | 24,3 | 19,12 | |

| 29 | 3.6 | A | PUC | -0,11 | -0,15 | -0,78 | -0,94 | -1,06 | -1,25 | 17,5 | 18,76 | |

| 30 | 3.7 | A | PUC | 0,05 | -0,09 | -0,25 | -0,38 | -0,58 | -0,87 | 15,4 | 14,45 | |

| 32 | 2.4 | A | NO-PUC | 0,35 | -0,05 | -0,52 | -0,79 | -0,9 | -1,1 | 29,87 | 27,12 | |

| 33 | 3.6 | A | PUC | 0,21 | -0,05 | -0,4 | -0,58 | -0,74 | -0,74 | 16,3 | 19,09 | |

| 34 | 4.6 | A | NO-PUC | -0,08 | -0,21 | -0,58 | -0,61 | -0,8 | REMOVED | 26,5 | 23,45 | |

| 1 | 3.6 | B | NO-PUC | 0,57 | 0,62 | 0 | -0,47 | -0,55 | -1 | 25,8 | 26,09 | |

| 4 | 3.6 | B | PUC | -0,17 | 0,03 | -0,5 | -0,71 | -0,81 | -1,32 | 14,6 | 21,45 | |

| 8 | 4.6 | B | NO-PUC | 0,2 | 0,21 | -0,48 | -0,74 | -0,79 | -1,2 | 29,45 | 24,59 | |

| 10 | 3.6 | B | PUC | -0,04 | 0 | -0,38 | -0,53 | -0,61 | -0,6 | 20,5 | 19,4 | |

| 12 | 2.4 | B | PUC | 0 | 0,1 | -0,35 | -0,55 | -0,71 | -1,1 | 20,4 | 22,22 | |

| 13 | 3.6 | B | NO-PUC | -0,02 | 0,15 | -0,37 | -0,67 | -0,89 | -1,25 | 19,3 | 18,41 | |

| 15 | 3.6 | B | NO-PUC | 0,16 | 0,39 | -0,08 | -0,61 | -0,74 | -1,45 | 17,9 | 19,45 | |

| 16 | 4.6 | B | PUC | 0,12 | 0,59 | -0,23 | -0,49 | -0,61 | -0,72 | 15,9 | 18,54 | |

| 18 | 1.5 | B | PUC | 0 | -0,36 | -0,57 | -0,69 | -0,77 | -0,8 | 14,1 | 13,4 | |

| 19 | 4.6 | B | PUC | 0,34 | 0,24 | 0 | -0,16 | -0,31 | -0,56 | 14,5 | 12,23 | |

| 22 | 2.4 | B | PUC | 0,29 | 0,28 | -0,29 | -0,88 | -0,95 | -0,23 | 14,5 | 16,98 | |

| 26 | 4.5 | B | PUC | -0,35 | -0,08 | -0,15 | -0,41 | -0,66 | -1,12 | 16,4 | 19,5 | |

| 27 | 3.7 | B | NO-PUC | 0 | -0,05 | -0,21 | -0,54 | -0,59 | -0,62 | 27,8 | 24,98 | |

| 28 | 2.5 | B | PUC | 0,06 | 0,18 | -0,3 | -0,37 | -0,57 | -0,72 | 20,12 | 22,45 | |

| 31 | 2.6 | B | NO-PUC | -0,26 | -0,08 | -0,46 | -0,56 | -0,7 | -1,1 | 26,23 | 26,23 | |

| MEAN | -0,8151613 mm | -1,04 mm | 21,38 % | 20,96 & | ||||||||

| ST. Dev | 0,28814199 | 0,39673669 | 5,65255588 | 4,76767566 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).